User login

Are Text Pages an Effective Nudge to Increase Attendance at Internal Medicine Morning Report Conferences? A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial

Regularly scheduled educational conferences, such as case-based morning reports, have been a standard part of internal medicine residencies for decades.1-4 In addition to better patient care from the knowledge gained at educational conferences, attendance by interns and residents (collectively called house staff) may be associated with higher in-service examination scores.5 Unfortunately, competing priorities, including patient care and trainee supervision, may contribute to an action-intention gap among house staff that reduces attendance.6-8 Low attendance at morning reports represents wasted effort and lost educational opportunities; therefore, strategies to increase attendance are needed. Of several methods studied, more resource-intensive interventions (eg, providing food) were the most successful.6,9-12

Using the behavioral economics framework of nudge strategies, we hypothesized that a less intensive intervention of a daily reminder text page would encourage medical students, interns, and residents (collectively called learners) to attend the morning report conference.8,13 However, given the high cognitive load created by frequent task switching, a reminder text page could disrupt workflow and patient care without promoting the intended behavior change.14-17 Because of this uncertainty, our objective was to determine whether a preconference text page increased learner attendance at morning report conferences.

Methods

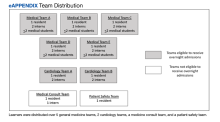

This study was a single-center, multiple-crossover cluster randomized controlled trial conducted at the Veteran Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) in Massachusetts. Study participants included house staff rotating on daytime inpatient rotations from 4 residency programs and students from 2 medical schools. The setting was the morning report, an in-person, interactive, case-based conference held Monday through Thursday, from 8:00

Learners assigned to rotate on the inpatient medicine, cardiology, medicine consultation, and patient safety rotations were eligible to attend these conferences and for inclusion in the study. Learners rotating in the medical intensive care unit, on night float, or on day float (an admitting shift for which residents are not on-site until late afternoon) were excluded. Additional details of the study population are available in the supplement (eAppendix). The study period was originally planned for September 30, 2019, to March 31, 2020, but data collection was stopped on March 12, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and suspension of in-person conferences. We chose the study period, which determined our sample size, to exclude the first 3 months of the academic year (July-September) because during that time learners acclimate to the inpatient workflow. We also chose not to include the last 3 months of the academic year to provide time for data analysis and preparation of the manuscript within the academic year.

Intervention and Outcome Assessment

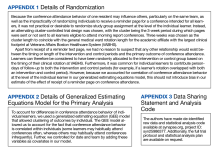

Each intervention and control period was 3 weeks long; the first period was randomly determined by coin flip and alternated thereafter. Additional details of randomization are available in the supplement (Appendix 1). During intervention periods, all house staff received a page at 7:55

A daily facesheet (a roster of house staff names and photos) was used to identify learners for conference attendance. This facesheet was already used for other purposes at VABHS. At 8:00

During control periods, no text page reminder of upcoming conferences was sent, but the attendance of total learners at 8:00

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was the proportion of eligible learners present at 8:10

To estimate the primary outcome, we modeled the risk difference adjusted for covariates using a generalized estimating equation accounting for the clustering of attendance behavior within individuals and controlling for date and team. Secondary outcomes were estimated similarly. To evaluate the robustness of the primary outcome, we performed a sensitivity analysis using a multilevel generalized linear model with clustering by individual learner and team. Additional details on our statistical analysis plan, including accessing our raw data and analysis code, are available in Appendices 2 and 3. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were compared using the t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. All P values were 2-sided, and a significance level of ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed in Stata v16.1. Our study was deemed exempt by the VABHS Institutional Review Board, and this article was prepared following the CONSORT reporting guidelines. The trial protocol has been registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number registry

Results

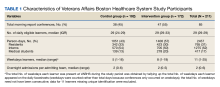

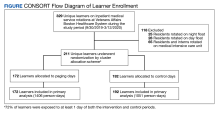

Over the study period, 329 unique learners rotated on inpatient medical services at the VABHS and 211 were eligible to attend 85 morning report conferences and 22 Jeopardy conferences (Figure). Outcomes data were available for 100% of eligible participants. Forty-seven (55%) of the morning report conferences occurred during the intervention period (Table 1).

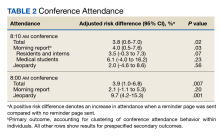

Morning report attendance observed at 8:10

On-time attendance was lower than at 8:10

To estimate the impact of rotating on teams with lighter clinical workloads on the association between receipt of a reminder page and conference attendance, we repeated our primary analysis with a test of interaction between team assignment and the intervention, which was not significant (P = .90). To estimate the impact of morning workload on the association between receipt of a reminder page and conference attendance, we performed a subgroup analysis limited to learners rotating on teams eligible to receive overnight admissions and included the number of overnight admissions as a covariate in our regression model. A test of interaction between the intervention and the number of overnight admissions on conference attendance was not significant (P = .73).

In a subgroup analysis limited to learners on teams eligible to receive overnight admissions and controlling for the number of overnight admissions (a proxy for morning workload), no significant interaction between the intervention and admissions was observed. We also assessed for interaction between learner type and receipt of a reminder page on conference attendance and found no evidence of such an effect.

Discussion

Among a diverse population of learners from multiple academic institutions rotating at a single, large, urban VA medical center, a nudge strategy of sending a reminder text page before morning report conferences was associated with a 4.0% absolute increase in attendance measured 10 minutes after the conference started compared with not sending a reminder page. Overall, only one-quarter of learners attended the morning report at the start at 8:00

We designed our analysis to overcome several limitations of prior studies on the effect of reminder text pages on conference attendance. First, to account for differences in conference attendance behavior of individual learners, we used a generalized estimating equation model that allowed clustering of outcomes by individual. Second, we controlled for the date to account for secular trends in conference attendance over the academic year. Finally, we controlled for the team to account for the possibility that the conference attendance behavior of one learner on a team influences the behavior of other learners on the same team.

We also evaluated the effect of a reminder page on attendance at a weekly Jeopardy conference. Interestingly, reminder pages seemed to increase on-time Jeopardy attendance, although this effect was no longer statistically significant at 8:10

We also assessed the interaction between sending a reminder page and learner type and its effect on conference attendance and found no evidence to support such an effect. Because medical students do not receive reminder pages, their conference attendance behavior can be thought of as indicative of clustering within teams. Though there was no evidence of a significant interaction, given the small number of students, our study may be underpowered to find a benefit for this group.

The results of this study differ from Smith and colleagues, who found that reminder pages had no overall effect on conference attendance for fellows; however, no sample size justification was provided in that study, making it difficult to evaluate the likelihood of a false-negative finding.7 Our study differs in several ways: the timing of the reminder page (5 minutes vs 30 minutes prior to the conference), the method by which attendance was recorded (by an independent observer vs learner sign-in), and the time that attendance was recorded (2 prespecified times vs continuously). As far as we know, our study is the first to evaluate the nudge effect of reminder text pages on internal medicine resident attendance at conferences, with attendance taken by an observer.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, it was conducted at a single VA medical center. An additional limitation was our decision to classify learners who arrived after 8:10

Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the suspension of in-person conferences, our study ended earlier than anticipated. This resulted in an imbalance of morning report conferences that occurred during each period: 55% during the intervention period, and 45% during the control period. However, because we accounted for the clustering of conference attendance behavior within individuals in our model, this imbalance is unlikely to introduce bias in our estimation of the effect of the intervention.

Another limitation relates to the evolving landscape of educational conferences in the postpandemic era.18 Whether our results can be generalized to increase virtual conference attendance is unknown. Finally, it is not clear whether a 4% absolute increase in conference attendance is educationally meaningful or justifies the effort of sending a reminder page.

Conclusions

In this cluster randomized controlled trial conducted at a single VA medical center, reminder pages sent 5 minutes before the start of morning report conferences resulted in a 4% increase in conference attendance. Our results suggest that reminder pages are one strategy that may result in a small increase in conference attendance, but whether this small increase is educationally significant will vary across training programs applying this strategy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Kenneth J. Mukamal and Katharine A. Robb, who provided invaluable guidance in data analysis. Todd Reese assisted in data organization and presentation of data, and Mark Tuttle designed the facesheet. None of these individuals received compensation for their assistance.

1. Daniels VJ, Goldstein CE. Changing morning report: an educational intervention to address curricular needs. J Biomed Educ. 2014;2014:1-5. doi:10.1155/2014/830701

2. Parrino TA, Villanueva AG. The principles and practice of morning report. JAMA. 1986;256(6):730-733. doi:10.1001/jama.1986.03380060056025

3. Wenger NS, Shpiner RB. An analysis of morning report: implications for internal medicine education. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(5):395-399. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-119-5-199309010-00008

4. Ways M, Kroenke K, Umali J, Buchwald D. Morning report. A survey of resident attitudes. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(13):1433-1437. doi:10.1001/archinte.155.13.1433

5. McDonald FS, Zeger SL, Kolars JC. Associations of conference attendance with internal medicine in-training examination scores. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(4):449-453. doi:10.4065/83.4.449

6. FitzGerald JD, Wenger NS. Didactic teaching conferences for IM residents: who attends, and is attendance related to medical certifying examination scores? Acad Med. 2003;78(1):84-89. doi:10.1097/00001888-200301000-00015

7. Smith J, Zaffiri L, Clary J, Davis T, Bosslet GT. The effect of paging reminders on fellowship conference attendance: a multi-program randomized crossover study. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):372-377. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-15-00487.1

8. Sheeran P, Webb TL. The intention-behavior gap. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2016;10(9):503-518. doi:10.1111/spc3.12265

9. McDonald RJ, Luetmer PH, Kallmes DF. If you starve them, will they still come? Do complementary food provisions affect faculty meeting attendance in academic radiology? J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8(11):809-810. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2011.06.003

10. Segovis CM, Mueller PS, Rethlefsen ML, et al. If you feed them, they will come: a prospective study of the effects of complimentary food on attendance and physician attitudes at medical grand rounds at an academic medical center. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:22. Published 2007 Jul 12. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-7-22

11. Mueller PS, Litin SC, Sowden ML, Habermann TM, LaRusso NF. Strategies for improving attendance at medical grand rounds at an academic medical center. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(5):549-553. doi:10.4065/78.5.549

12. Tarabichi S, DeLeon M, Krumrei N, Hanna J, Maloney Patel N. Competition as a means for improving academic scores and attendance at education conference. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(6):1437-1440. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.04.020

13. Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Rev. and Expanded Ed. Penguin Books; 2009.

14. Weijers RJ, de Koning BB, Paas F. Nudging in education: from theory towards guidelines for successful implementation. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2021;36:883-902. Published 2020 Aug 24. doi:10.1007/s10212-020-00495-0

15. Wieland ML, Loertscher LL, Nelson DR, Szostek JH, Ficalora RD. A strategy to reduce interruptions at hospital morning report. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(1):83-84. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-09-00084.1

16. Witherspoon L, Nham E, Abdi H, et al. Is it time to rethink how we page physicians? Understanding paging patterns in a tertiary care hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):992. Published 2019 Dec 23. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4844-0

17. Fargen KM, O’Connor T, Raymond S, Sporrer JM, Friedman WA. An observational study of hospital paging practices and workflow interruption among on-call junior neurological surgery residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):467-471. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-00306.1

18. Chick RC, Clifton GT, Peace KM, et al. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):729-732. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018

Regularly scheduled educational conferences, such as case-based morning reports, have been a standard part of internal medicine residencies for decades.1-4 In addition to better patient care from the knowledge gained at educational conferences, attendance by interns and residents (collectively called house staff) may be associated with higher in-service examination scores.5 Unfortunately, competing priorities, including patient care and trainee supervision, may contribute to an action-intention gap among house staff that reduces attendance.6-8 Low attendance at morning reports represents wasted effort and lost educational opportunities; therefore, strategies to increase attendance are needed. Of several methods studied, more resource-intensive interventions (eg, providing food) were the most successful.6,9-12

Using the behavioral economics framework of nudge strategies, we hypothesized that a less intensive intervention of a daily reminder text page would encourage medical students, interns, and residents (collectively called learners) to attend the morning report conference.8,13 However, given the high cognitive load created by frequent task switching, a reminder text page could disrupt workflow and patient care without promoting the intended behavior change.14-17 Because of this uncertainty, our objective was to determine whether a preconference text page increased learner attendance at morning report conferences.

Methods

This study was a single-center, multiple-crossover cluster randomized controlled trial conducted at the Veteran Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) in Massachusetts. Study participants included house staff rotating on daytime inpatient rotations from 4 residency programs and students from 2 medical schools. The setting was the morning report, an in-person, interactive, case-based conference held Monday through Thursday, from 8:00

Learners assigned to rotate on the inpatient medicine, cardiology, medicine consultation, and patient safety rotations were eligible to attend these conferences and for inclusion in the study. Learners rotating in the medical intensive care unit, on night float, or on day float (an admitting shift for which residents are not on-site until late afternoon) were excluded. Additional details of the study population are available in the supplement (eAppendix). The study period was originally planned for September 30, 2019, to March 31, 2020, but data collection was stopped on March 12, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and suspension of in-person conferences. We chose the study period, which determined our sample size, to exclude the first 3 months of the academic year (July-September) because during that time learners acclimate to the inpatient workflow. We also chose not to include the last 3 months of the academic year to provide time for data analysis and preparation of the manuscript within the academic year.

Intervention and Outcome Assessment

Each intervention and control period was 3 weeks long; the first period was randomly determined by coin flip and alternated thereafter. Additional details of randomization are available in the supplement (Appendix 1). During intervention periods, all house staff received a page at 7:55

A daily facesheet (a roster of house staff names and photos) was used to identify learners for conference attendance. This facesheet was already used for other purposes at VABHS. At 8:00

During control periods, no text page reminder of upcoming conferences was sent, but the attendance of total learners at 8:00

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was the proportion of eligible learners present at 8:10

To estimate the primary outcome, we modeled the risk difference adjusted for covariates using a generalized estimating equation accounting for the clustering of attendance behavior within individuals and controlling for date and team. Secondary outcomes were estimated similarly. To evaluate the robustness of the primary outcome, we performed a sensitivity analysis using a multilevel generalized linear model with clustering by individual learner and team. Additional details on our statistical analysis plan, including accessing our raw data and analysis code, are available in Appendices 2 and 3. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were compared using the t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. All P values were 2-sided, and a significance level of ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed in Stata v16.1. Our study was deemed exempt by the VABHS Institutional Review Board, and this article was prepared following the CONSORT reporting guidelines. The trial protocol has been registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number registry

Results

Over the study period, 329 unique learners rotated on inpatient medical services at the VABHS and 211 were eligible to attend 85 morning report conferences and 22 Jeopardy conferences (Figure). Outcomes data were available for 100% of eligible participants. Forty-seven (55%) of the morning report conferences occurred during the intervention period (Table 1).

Morning report attendance observed at 8:10

On-time attendance was lower than at 8:10

To estimate the impact of rotating on teams with lighter clinical workloads on the association between receipt of a reminder page and conference attendance, we repeated our primary analysis with a test of interaction between team assignment and the intervention, which was not significant (P = .90). To estimate the impact of morning workload on the association between receipt of a reminder page and conference attendance, we performed a subgroup analysis limited to learners rotating on teams eligible to receive overnight admissions and included the number of overnight admissions as a covariate in our regression model. A test of interaction between the intervention and the number of overnight admissions on conference attendance was not significant (P = .73).

In a subgroup analysis limited to learners on teams eligible to receive overnight admissions and controlling for the number of overnight admissions (a proxy for morning workload), no significant interaction between the intervention and admissions was observed. We also assessed for interaction between learner type and receipt of a reminder page on conference attendance and found no evidence of such an effect.

Discussion

Among a diverse population of learners from multiple academic institutions rotating at a single, large, urban VA medical center, a nudge strategy of sending a reminder text page before morning report conferences was associated with a 4.0% absolute increase in attendance measured 10 minutes after the conference started compared with not sending a reminder page. Overall, only one-quarter of learners attended the morning report at the start at 8:00

We designed our analysis to overcome several limitations of prior studies on the effect of reminder text pages on conference attendance. First, to account for differences in conference attendance behavior of individual learners, we used a generalized estimating equation model that allowed clustering of outcomes by individual. Second, we controlled for the date to account for secular trends in conference attendance over the academic year. Finally, we controlled for the team to account for the possibility that the conference attendance behavior of one learner on a team influences the behavior of other learners on the same team.

We also evaluated the effect of a reminder page on attendance at a weekly Jeopardy conference. Interestingly, reminder pages seemed to increase on-time Jeopardy attendance, although this effect was no longer statistically significant at 8:10

We also assessed the interaction between sending a reminder page and learner type and its effect on conference attendance and found no evidence to support such an effect. Because medical students do not receive reminder pages, their conference attendance behavior can be thought of as indicative of clustering within teams. Though there was no evidence of a significant interaction, given the small number of students, our study may be underpowered to find a benefit for this group.

The results of this study differ from Smith and colleagues, who found that reminder pages had no overall effect on conference attendance for fellows; however, no sample size justification was provided in that study, making it difficult to evaluate the likelihood of a false-negative finding.7 Our study differs in several ways: the timing of the reminder page (5 minutes vs 30 minutes prior to the conference), the method by which attendance was recorded (by an independent observer vs learner sign-in), and the time that attendance was recorded (2 prespecified times vs continuously). As far as we know, our study is the first to evaluate the nudge effect of reminder text pages on internal medicine resident attendance at conferences, with attendance taken by an observer.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, it was conducted at a single VA medical center. An additional limitation was our decision to classify learners who arrived after 8:10

Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the suspension of in-person conferences, our study ended earlier than anticipated. This resulted in an imbalance of morning report conferences that occurred during each period: 55% during the intervention period, and 45% during the control period. However, because we accounted for the clustering of conference attendance behavior within individuals in our model, this imbalance is unlikely to introduce bias in our estimation of the effect of the intervention.

Another limitation relates to the evolving landscape of educational conferences in the postpandemic era.18 Whether our results can be generalized to increase virtual conference attendance is unknown. Finally, it is not clear whether a 4% absolute increase in conference attendance is educationally meaningful or justifies the effort of sending a reminder page.

Conclusions

In this cluster randomized controlled trial conducted at a single VA medical center, reminder pages sent 5 minutes before the start of morning report conferences resulted in a 4% increase in conference attendance. Our results suggest that reminder pages are one strategy that may result in a small increase in conference attendance, but whether this small increase is educationally significant will vary across training programs applying this strategy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Kenneth J. Mukamal and Katharine A. Robb, who provided invaluable guidance in data analysis. Todd Reese assisted in data organization and presentation of data, and Mark Tuttle designed the facesheet. None of these individuals received compensation for their assistance.

Regularly scheduled educational conferences, such as case-based morning reports, have been a standard part of internal medicine residencies for decades.1-4 In addition to better patient care from the knowledge gained at educational conferences, attendance by interns and residents (collectively called house staff) may be associated with higher in-service examination scores.5 Unfortunately, competing priorities, including patient care and trainee supervision, may contribute to an action-intention gap among house staff that reduces attendance.6-8 Low attendance at morning reports represents wasted effort and lost educational opportunities; therefore, strategies to increase attendance are needed. Of several methods studied, more resource-intensive interventions (eg, providing food) were the most successful.6,9-12

Using the behavioral economics framework of nudge strategies, we hypothesized that a less intensive intervention of a daily reminder text page would encourage medical students, interns, and residents (collectively called learners) to attend the morning report conference.8,13 However, given the high cognitive load created by frequent task switching, a reminder text page could disrupt workflow and patient care without promoting the intended behavior change.14-17 Because of this uncertainty, our objective was to determine whether a preconference text page increased learner attendance at morning report conferences.

Methods

This study was a single-center, multiple-crossover cluster randomized controlled trial conducted at the Veteran Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) in Massachusetts. Study participants included house staff rotating on daytime inpatient rotations from 4 residency programs and students from 2 medical schools. The setting was the morning report, an in-person, interactive, case-based conference held Monday through Thursday, from 8:00

Learners assigned to rotate on the inpatient medicine, cardiology, medicine consultation, and patient safety rotations were eligible to attend these conferences and for inclusion in the study. Learners rotating in the medical intensive care unit, on night float, or on day float (an admitting shift for which residents are not on-site until late afternoon) were excluded. Additional details of the study population are available in the supplement (eAppendix). The study period was originally planned for September 30, 2019, to March 31, 2020, but data collection was stopped on March 12, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and suspension of in-person conferences. We chose the study period, which determined our sample size, to exclude the first 3 months of the academic year (July-September) because during that time learners acclimate to the inpatient workflow. We also chose not to include the last 3 months of the academic year to provide time for data analysis and preparation of the manuscript within the academic year.

Intervention and Outcome Assessment

Each intervention and control period was 3 weeks long; the first period was randomly determined by coin flip and alternated thereafter. Additional details of randomization are available in the supplement (Appendix 1). During intervention periods, all house staff received a page at 7:55

A daily facesheet (a roster of house staff names and photos) was used to identify learners for conference attendance. This facesheet was already used for other purposes at VABHS. At 8:00

During control periods, no text page reminder of upcoming conferences was sent, but the attendance of total learners at 8:00

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was the proportion of eligible learners present at 8:10

To estimate the primary outcome, we modeled the risk difference adjusted for covariates using a generalized estimating equation accounting for the clustering of attendance behavior within individuals and controlling for date and team. Secondary outcomes were estimated similarly. To evaluate the robustness of the primary outcome, we performed a sensitivity analysis using a multilevel generalized linear model with clustering by individual learner and team. Additional details on our statistical analysis plan, including accessing our raw data and analysis code, are available in Appendices 2 and 3. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were compared using the t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. All P values were 2-sided, and a significance level of ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed in Stata v16.1. Our study was deemed exempt by the VABHS Institutional Review Board, and this article was prepared following the CONSORT reporting guidelines. The trial protocol has been registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number registry

Results

Over the study period, 329 unique learners rotated on inpatient medical services at the VABHS and 211 were eligible to attend 85 morning report conferences and 22 Jeopardy conferences (Figure). Outcomes data were available for 100% of eligible participants. Forty-seven (55%) of the morning report conferences occurred during the intervention period (Table 1).

Morning report attendance observed at 8:10

On-time attendance was lower than at 8:10

To estimate the impact of rotating on teams with lighter clinical workloads on the association between receipt of a reminder page and conference attendance, we repeated our primary analysis with a test of interaction between team assignment and the intervention, which was not significant (P = .90). To estimate the impact of morning workload on the association between receipt of a reminder page and conference attendance, we performed a subgroup analysis limited to learners rotating on teams eligible to receive overnight admissions and included the number of overnight admissions as a covariate in our regression model. A test of interaction between the intervention and the number of overnight admissions on conference attendance was not significant (P = .73).

In a subgroup analysis limited to learners on teams eligible to receive overnight admissions and controlling for the number of overnight admissions (a proxy for morning workload), no significant interaction between the intervention and admissions was observed. We also assessed for interaction between learner type and receipt of a reminder page on conference attendance and found no evidence of such an effect.

Discussion

Among a diverse population of learners from multiple academic institutions rotating at a single, large, urban VA medical center, a nudge strategy of sending a reminder text page before morning report conferences was associated with a 4.0% absolute increase in attendance measured 10 minutes after the conference started compared with not sending a reminder page. Overall, only one-quarter of learners attended the morning report at the start at 8:00

We designed our analysis to overcome several limitations of prior studies on the effect of reminder text pages on conference attendance. First, to account for differences in conference attendance behavior of individual learners, we used a generalized estimating equation model that allowed clustering of outcomes by individual. Second, we controlled for the date to account for secular trends in conference attendance over the academic year. Finally, we controlled for the team to account for the possibility that the conference attendance behavior of one learner on a team influences the behavior of other learners on the same team.

We also evaluated the effect of a reminder page on attendance at a weekly Jeopardy conference. Interestingly, reminder pages seemed to increase on-time Jeopardy attendance, although this effect was no longer statistically significant at 8:10

We also assessed the interaction between sending a reminder page and learner type and its effect on conference attendance and found no evidence to support such an effect. Because medical students do not receive reminder pages, their conference attendance behavior can be thought of as indicative of clustering within teams. Though there was no evidence of a significant interaction, given the small number of students, our study may be underpowered to find a benefit for this group.

The results of this study differ from Smith and colleagues, who found that reminder pages had no overall effect on conference attendance for fellows; however, no sample size justification was provided in that study, making it difficult to evaluate the likelihood of a false-negative finding.7 Our study differs in several ways: the timing of the reminder page (5 minutes vs 30 minutes prior to the conference), the method by which attendance was recorded (by an independent observer vs learner sign-in), and the time that attendance was recorded (2 prespecified times vs continuously). As far as we know, our study is the first to evaluate the nudge effect of reminder text pages on internal medicine resident attendance at conferences, with attendance taken by an observer.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, it was conducted at a single VA medical center. An additional limitation was our decision to classify learners who arrived after 8:10

Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the suspension of in-person conferences, our study ended earlier than anticipated. This resulted in an imbalance of morning report conferences that occurred during each period: 55% during the intervention period, and 45% during the control period. However, because we accounted for the clustering of conference attendance behavior within individuals in our model, this imbalance is unlikely to introduce bias in our estimation of the effect of the intervention.

Another limitation relates to the evolving landscape of educational conferences in the postpandemic era.18 Whether our results can be generalized to increase virtual conference attendance is unknown. Finally, it is not clear whether a 4% absolute increase in conference attendance is educationally meaningful or justifies the effort of sending a reminder page.

Conclusions

In this cluster randomized controlled trial conducted at a single VA medical center, reminder pages sent 5 minutes before the start of morning report conferences resulted in a 4% increase in conference attendance. Our results suggest that reminder pages are one strategy that may result in a small increase in conference attendance, but whether this small increase is educationally significant will vary across training programs applying this strategy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Kenneth J. Mukamal and Katharine A. Robb, who provided invaluable guidance in data analysis. Todd Reese assisted in data organization and presentation of data, and Mark Tuttle designed the facesheet. None of these individuals received compensation for their assistance.

1. Daniels VJ, Goldstein CE. Changing morning report: an educational intervention to address curricular needs. J Biomed Educ. 2014;2014:1-5. doi:10.1155/2014/830701

2. Parrino TA, Villanueva AG. The principles and practice of morning report. JAMA. 1986;256(6):730-733. doi:10.1001/jama.1986.03380060056025

3. Wenger NS, Shpiner RB. An analysis of morning report: implications for internal medicine education. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(5):395-399. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-119-5-199309010-00008

4. Ways M, Kroenke K, Umali J, Buchwald D. Morning report. A survey of resident attitudes. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(13):1433-1437. doi:10.1001/archinte.155.13.1433

5. McDonald FS, Zeger SL, Kolars JC. Associations of conference attendance with internal medicine in-training examination scores. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(4):449-453. doi:10.4065/83.4.449

6. FitzGerald JD, Wenger NS. Didactic teaching conferences for IM residents: who attends, and is attendance related to medical certifying examination scores? Acad Med. 2003;78(1):84-89. doi:10.1097/00001888-200301000-00015

7. Smith J, Zaffiri L, Clary J, Davis T, Bosslet GT. The effect of paging reminders on fellowship conference attendance: a multi-program randomized crossover study. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):372-377. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-15-00487.1

8. Sheeran P, Webb TL. The intention-behavior gap. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2016;10(9):503-518. doi:10.1111/spc3.12265

9. McDonald RJ, Luetmer PH, Kallmes DF. If you starve them, will they still come? Do complementary food provisions affect faculty meeting attendance in academic radiology? J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8(11):809-810. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2011.06.003

10. Segovis CM, Mueller PS, Rethlefsen ML, et al. If you feed them, they will come: a prospective study of the effects of complimentary food on attendance and physician attitudes at medical grand rounds at an academic medical center. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:22. Published 2007 Jul 12. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-7-22

11. Mueller PS, Litin SC, Sowden ML, Habermann TM, LaRusso NF. Strategies for improving attendance at medical grand rounds at an academic medical center. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(5):549-553. doi:10.4065/78.5.549

12. Tarabichi S, DeLeon M, Krumrei N, Hanna J, Maloney Patel N. Competition as a means for improving academic scores and attendance at education conference. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(6):1437-1440. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.04.020

13. Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Rev. and Expanded Ed. Penguin Books; 2009.

14. Weijers RJ, de Koning BB, Paas F. Nudging in education: from theory towards guidelines for successful implementation. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2021;36:883-902. Published 2020 Aug 24. doi:10.1007/s10212-020-00495-0

15. Wieland ML, Loertscher LL, Nelson DR, Szostek JH, Ficalora RD. A strategy to reduce interruptions at hospital morning report. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(1):83-84. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-09-00084.1

16. Witherspoon L, Nham E, Abdi H, et al. Is it time to rethink how we page physicians? Understanding paging patterns in a tertiary care hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):992. Published 2019 Dec 23. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4844-0

17. Fargen KM, O’Connor T, Raymond S, Sporrer JM, Friedman WA. An observational study of hospital paging practices and workflow interruption among on-call junior neurological surgery residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):467-471. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-00306.1

18. Chick RC, Clifton GT, Peace KM, et al. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):729-732. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018

1. Daniels VJ, Goldstein CE. Changing morning report: an educational intervention to address curricular needs. J Biomed Educ. 2014;2014:1-5. doi:10.1155/2014/830701

2. Parrino TA, Villanueva AG. The principles and practice of morning report. JAMA. 1986;256(6):730-733. doi:10.1001/jama.1986.03380060056025

3. Wenger NS, Shpiner RB. An analysis of morning report: implications for internal medicine education. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(5):395-399. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-119-5-199309010-00008

4. Ways M, Kroenke K, Umali J, Buchwald D. Morning report. A survey of resident attitudes. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(13):1433-1437. doi:10.1001/archinte.155.13.1433

5. McDonald FS, Zeger SL, Kolars JC. Associations of conference attendance with internal medicine in-training examination scores. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(4):449-453. doi:10.4065/83.4.449

6. FitzGerald JD, Wenger NS. Didactic teaching conferences for IM residents: who attends, and is attendance related to medical certifying examination scores? Acad Med. 2003;78(1):84-89. doi:10.1097/00001888-200301000-00015

7. Smith J, Zaffiri L, Clary J, Davis T, Bosslet GT. The effect of paging reminders on fellowship conference attendance: a multi-program randomized crossover study. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):372-377. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-15-00487.1

8. Sheeran P, Webb TL. The intention-behavior gap. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2016;10(9):503-518. doi:10.1111/spc3.12265

9. McDonald RJ, Luetmer PH, Kallmes DF. If you starve them, will they still come? Do complementary food provisions affect faculty meeting attendance in academic radiology? J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8(11):809-810. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2011.06.003

10. Segovis CM, Mueller PS, Rethlefsen ML, et al. If you feed them, they will come: a prospective study of the effects of complimentary food on attendance and physician attitudes at medical grand rounds at an academic medical center. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:22. Published 2007 Jul 12. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-7-22

11. Mueller PS, Litin SC, Sowden ML, Habermann TM, LaRusso NF. Strategies for improving attendance at medical grand rounds at an academic medical center. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(5):549-553. doi:10.4065/78.5.549

12. Tarabichi S, DeLeon M, Krumrei N, Hanna J, Maloney Patel N. Competition as a means for improving academic scores and attendance at education conference. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(6):1437-1440. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.04.020

13. Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Rev. and Expanded Ed. Penguin Books; 2009.

14. Weijers RJ, de Koning BB, Paas F. Nudging in education: from theory towards guidelines for successful implementation. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2021;36:883-902. Published 2020 Aug 24. doi:10.1007/s10212-020-00495-0

15. Wieland ML, Loertscher LL, Nelson DR, Szostek JH, Ficalora RD. A strategy to reduce interruptions at hospital morning report. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(1):83-84. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-09-00084.1

16. Witherspoon L, Nham E, Abdi H, et al. Is it time to rethink how we page physicians? Understanding paging patterns in a tertiary care hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):992. Published 2019 Dec 23. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4844-0

17. Fargen KM, O’Connor T, Raymond S, Sporrer JM, Friedman WA. An observational study of hospital paging practices and workflow interruption among on-call junior neurological surgery residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):467-471. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-00306.1

18. Chick RC, Clifton GT, Peace KM, et al. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):729-732. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018

A Veteran Presenting for Low Testosterone and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

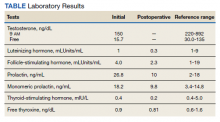

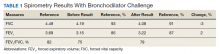

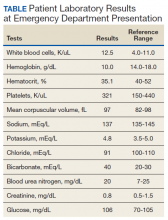

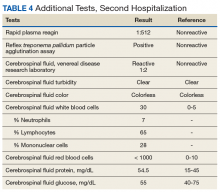

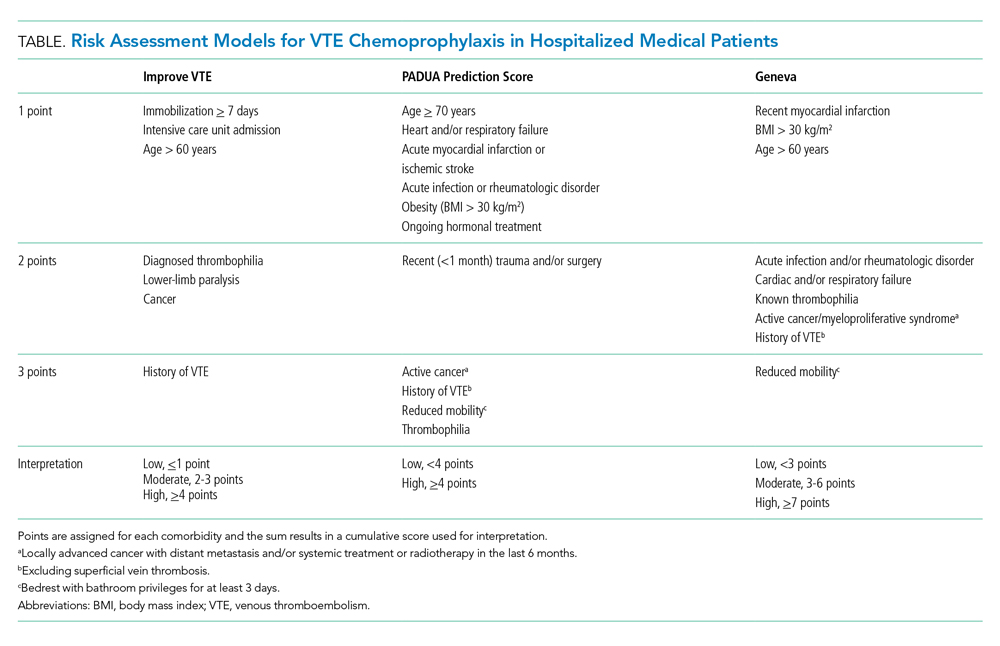

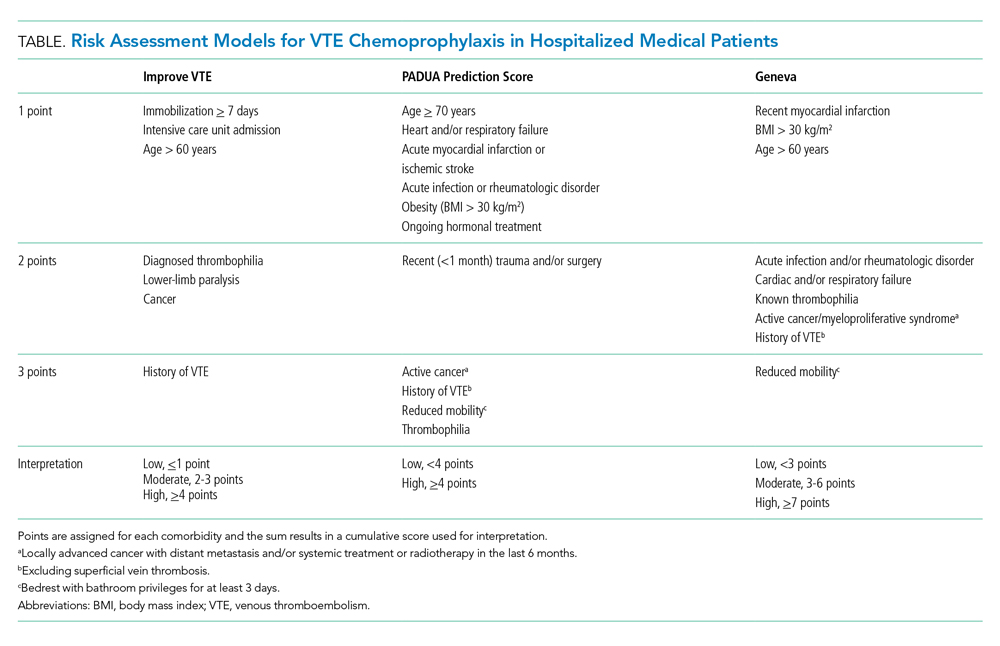

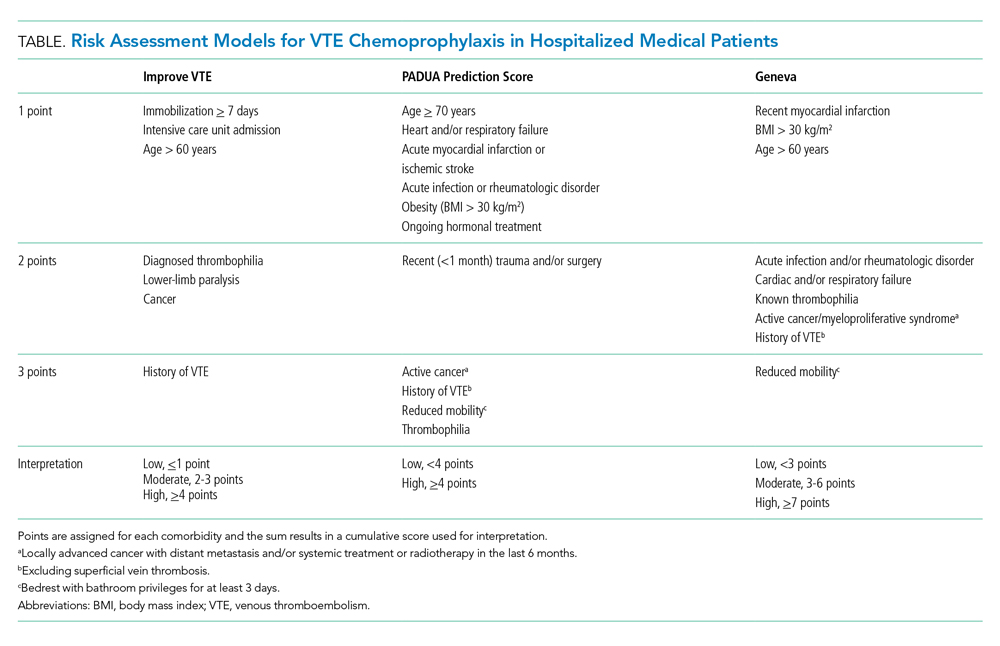

►Anish Bhatnagar, MD, Chief Medical Resident, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC): The patient noted erectile dysfunction starting 4 years ago, with accompanied decreased libido. However, until recently, he was able to achieve acceptable erectile capacity with medications. As part of his previous evaluations for erectile dysfunction, the patient had 2 total testosterone levels checked 6 months apart, both low at 150 ng/dL and 38.3 ng/dL (reference range, 220-892). The results of additional hormone studies are shown in the Table. Dr. Ananthakrishnan, can you help us interpret these laboratory results and tell us what tests you might order next?

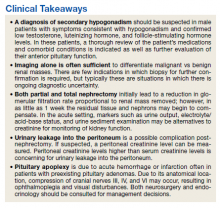

►Sonia Ananthakrishnan, MD, Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Nutrition, Boston Medical Center (BMC) and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM): When patients present with signs of hypogonadism and an initial low morning testosterone levels, the next test should be a confirmatory repeat morning testosterone level as was done in this case. If this level is also low (for most assays < 300 ng/dL), further evaluation for primary vs secondary hypogonadism should be pursued with measurement of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone levels. Secondary hypogonadism should be suspected when these levels are low or inappropriately normal in the setting of a low testosterone level as in this patient. This patient does not appear to be on any medication or have reversible illnesses that we traditionally think of as possibly causing these hormone irregularities. Key examples include medications such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs, glucocorticoids, and opioids, as well as conditions such as hyperprolactinemia, sleep apnea, diabetes mellitus, anorexia nervosa, or other chronic systemic illnesses, including cirrhosis or lung disease. In this setting, further evaluation of the patient’s anterior pituitary function should be undertaken. Initial screening tests showed mildly elevated prolactin and low normal thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, with a relatively normal free thyroxine. Given these abnormalities in the context of the patient’s total testosterone level < 150 ng/dL, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the anterior pituitary is indicated, and what I would recommend next for evaluation of pituitary and/or hypothalamic tumor or infiltrative disease.1

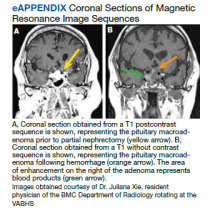

►Dr. Bhatnagar: An MRI of the brain showed a large 2.7-cm sellar mass, with suprasellar extension and mass effect on the optic chiasm and pituitary infundibulum, partial extension into the right sphenoid sinus, and invasion into the right cavernous sinus. These findings were consistent with a pituitary macroadenoma. The patient was subsequently evaluated by a neurosurgeon who felt that because of the extension and compression of the mass, the patient would benefit from surgical resection.

Given his lower urinary tract symptoms, a prostate-specific antigen level was checked and returned elevated at 11.5 ng/mL. In the setting of these abnormalities, the patient underwent MRI of the abdomen, which noted a new 5.6-cm enhancing mass in the upper pole of his solitary right kidney, highly concerning for new RCC. After a multidisciplinary discussion, urology scheduled the patient for partial right nephrectomy first, with plans for pituitary resection only if the patient had adequate recovery following the urologic procedure.

Dr. Rifkin, this patient went straight from imaging to presumed diagnosis to planned surgical intervention without a confirmatory biopsy. In a patient who already has chronic kidney disease stage 4, why would we not want to pursue biopsy prior to this invasive procedure on his solitary kidney? In addition, given his baseline advanced renal disease, why pursue partial nephrectomy to delay initiation of hemodialysis instead of total nephrectomy and beginning hemodialysis?

►Ian Rifkin, MBBCh, PhD, MSc, Chief, Renal Section, VABHS, Section of Nephrology, BMC, and Associate Professor of Medicine, BUSM: In most cases, imaging alone is used to make a presumptive diagnosis of benign vs malignant renal masses. In one study, RCC was identified by MRI with 85% sensitivity and 76% specificity.2 However, as imaging and biopsy techniques have advanced, there are progressing discussions regarding the utility of biopsy. That being said, there are a number of situations in which patients currently undergo biopsy, particularly when there is diagnostic uncertainty.3 In this patient, with a history of RCC and imaging findings concerning for RCC, biopsy is unnecessary given the high clinical suspicion.

Regarding the choice of partial vs total nephrectomy, there are 2 important distinctions to be made. The first is that though it was previously felt that early initiation of dialysis improves survival, newer studies suggest that early initiation based off of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) offers no survival benefits compared to delayed initiation.4 Second, though there is less clinical data to support this, there is a signal toward the use of partial nephrectomy decreasing mortality compared to radical nephrectomy in management of RCC.5 In this patient, partial nephrectomy may not only increase rates of survival, but also delay initiation of dialysis.

►Dr. Bhatnagar: Prior to undergoing partial right nephrectomy, a morning cortisol level was found to be 5.8 μg/dL with an associated corticotropin (ACTH) level of 26 pg/mL. Dr. Ananthakrishnan, how would you interpret these laboratory results and what might you recommend prior to surgery?

►Dr. Ananthakrishnan: In a healthy patient, surgery often results in a several-fold increase in the secretion of cortisol to balance the unique stressors surgery places on the body.6 This patient is at increased risk for complete or partial adrenal insufficiency in the setting of both his pituitary macroadenoma as well as his previous left nephrectomy, which could have affected his left adrenal gland as well. Thus, this patient may not be able to mount the appropriate cortisol response needed to counter the stresses of surgery. His cortisol level is abnormally low for a morning value, with a relatively normal ACTH reference range of 6 to 50 pg/mL. He may have some degree of adrenal insufficiency, and thus will benefit from perioperative steroids.

►Dr. Bhatnagar: The patient was started on hydrocortisone and underwent a successful laparoscopic partial right nephrectomy. During the procedure, an estimated 2.5 L of blood was lost, with transfusion of 3 units of packed red blood cells. A surgical drain was left in the peritoneum. Postoperatively, he developed hypotension, requiring vasopressors and prolonged continuation of stress dosing of hydrocortisone. Over the next 4 days, the patient was weaned off vasopressors, and his creatinine level was noted to increase from a baseline of 1.8 mg/dL to 4.4 mg/dL.

Dr. Rifkin, how do you think about renal recovery in the patient postnephrectomy, and should we be concerned with the dramatic rise in his creatinine level?

►Dr. Rifkin: Removal of renal mass will result in an initial reduction of GFR proportional to the amount of functional renal tissue removed. However, in as early as 1 week, the residual nephrons begin to compensate through various mechanisms, such as modulation of efferent and afferent arterioles and renal tissue growth by hypertrophy and hyperplasia.7 In the acute setting, it may be difficult to distinguish an acute renal injury vs physiological GFR reduction postnephron loss, but often the initially elevated creatinine level may normalize/stabilize over time. Other markers of kidney function should concomitantly be monitored, including urine output, electrolyte/acid-base status, and urine sediment examination. In this patient, although his creatinine level may be elevated over the first few days, if his urine output remains robust and the urine sediment examination is normal, my concern for permanent kidney injury would be lessened.

►Dr. Bhatnagar: During the first 4 postoperative days the patient produced approximately 1 L of urine per day with a stable creatinine level. It is over this same time that the hydrocortisone was discontinued given improving hemodynamics. However, throughout postoperative day 5, the patient’s creatinine level acutely rose to a peak of 5.8 mg/dL. In addition, his urine output dramatically dropped to < 5 mL per hour, with blood clots noted in his Foley catheter. Dr. Rifkin, what is your differential for causing this acute change in both his creatinine level and urine output this far out from his procedure, and what might you do to help further evaluate?

►Dr. Rifkin: The most common cause of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients is acute tubular necrosis (ATN).8 However, in this patient, who was recovering well postoperatively, was hemodynamically stable with a robust urine output, and in whom no apparent cause for ATN could be identified, other diagnoses were more likely. Considering the abrupt onset of oligo-anuria, the most likely diagnosis was urinary tract obstruction, particularly given the frank blood and blood clots that were present in the urine. Additional possibilities might be a late surgical complication or infection. Surgical complications could range from direct damage to the renal parenchyma to urinary leakage into the peritoneum from the site of anastomosis or tissue injury. Infections introduced either intraoperatively or developed postoperatively could also cause this sudden drop in urine output, though one would expect more systemic symptoms with this. Given that this patient has a surgical drain in place in the peritoneum, I would recommend testing the creatinine level in the peritoneal fluid drainage. If it is comparable to serum levels, this would argue against a urine leak, as we would expect the level to be significantly elevated in a leak. In addition, he should have imaging of the urinary tract followed by procedures to decompress the presumed obstructed urinary tract. These procedures might include either cystoscopy with ureteral stent placement or percutaneous nephrostomy, depending on the result of the imaging.

►Dr. Bhatnagar: The creatinine level obtained from the surgical drain was roughly equivalent to the serum creatinine, decreasing suspicion for a urine leak as the cause of his findings. Cystoscopy with ureteral stent placement was performed with subsequent increase in both urine output and concomitant decrease in serum creatinine.

Around this time, the patient also began to note blurry vision. Evaluation revealed difficulty with visual field confrontation in the right lower quadrant, right eye ptosis, right eye impaired adduction, absent abduction and impaired upgaze, but intact downgaze. Diplopia was present with gaze in all directions. His constellation of physical examination findings were concerning for a pathologic lesion partially involving cranial nerves II and III, with definitive involvement of cranial nerve VI, but sparing of cranial nerve IV. Repeat MRI of the brain showed hemorrhage into the sellar mass, with ongoing mass effect on the optic chiasm and extension into the sinuses (eAppendix). These findings were consistent with pituitary apoplexy. Dr. Ananthakrishnan, can you tell us more about pituitary apoplexy?

►Dr. Ananthakrishnan: Pituitary apoplexy is a clinical syndrome resulting from acute hemorrhage or infarction of the pituitary gland. It typically occurs in patients with preexisting pituitary adenomas and is characterized by the onset of headache, fever, vomiting, meningismus, decreased consciousness, and sometimes death. In addition, given the location of the pituitary gland within the sella, rapid changes in size can result in compression of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI, as well as the optic chiasm, resulting in ophthalmoplegia and visual disturbances as seen in this patient.9

There are a multitude of causes of pituitary apoplexy, including alterations in coagulopathy, pituitary stimulation (eg, dynamic pituitary hormone testing), and both acute increases and decreases in blood flow.10 This patient likely had an ischemic event due to changes in vascular perfusion, spurred by both his blood loss intraoperatively and ongoing hematuria. Management of pituitary apoplexy is dependent on the patient’s hemodynamics, mass effect symptoms, electrolyte balances, and hormone dysfunction. The decision for conservative management vs surgical intervention should be made in consultation with both neurosurgery and endocrinology. Once the patient is hemodynamically stable, the next step in evaluating this patient should be repeating his hormone studies.

►Dr. Bhatnagar: An assessment of pituitary function was consistent with values obtained preoperatively. After multidisciplinary discussions, surgery was deferred, and hydrocortisone was reinitiated to reduce inflammation caused by bleeding into the mass. As the ophthalmoplegia improved, this was transitioned to dexamethasone.

Twelve days after admission, he was discharged to a subacute rehabilitation center, with improvement in his ophthalmoplegia and stabilization of his creatinine level and urine output.

1. Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(6):2536-2559. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2354

2. Kay FU, Canvasser NE, Xi Y, et al. Diagnostic performance and interreader agreement of a standardized MR imaging approach in the prediction of small renal mass histology. Radiology. 2018;287(2):543-553. doi:10.1148/radiol.2018171557

3. Sahni VA, Silverman SG. Biopsy of renal masses: when and why. Cancer Imaging. 2009;9(1):44-55. doi:10.1102/1470-7330.2009.0005

4. Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(7):609-619. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1000552

5. Kunath F, Schmidt S, Krabbe L-M, et al. Partial nephrectomy versus radical nephrectomy for clinical localised renal masses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5(5):CD012045. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012045.pub2

6. Kehlet H, Binder C. Adrenocortical function and clinical course during and after surgery in unsupplemented glucocorticoid-treated patients. Br J Anaesth. 1973;45(10):1043-1048. doi:10.1093/bja/45.10.1043

7. Chapman D, Moore R, Klarenbach S, Braam B. Residual renal function after partial or radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4(5):337-343. doi:10.5489/cuaj.909

8. Rahman M, Shad F, Smith MC. Acute kidney injury: a guide to diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(7):631-639.

9. Ranabir S, Baruah MP. Pituitary apoplexy. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15(suppl 3):S188-S196. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.84862

10. Glezer A, Bronstein MD. Pituitary apoplexy: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2015;59(3):259-264. doi:10.1590/2359-3997000000047

►Anish Bhatnagar, MD, Chief Medical Resident, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC): The patient noted erectile dysfunction starting 4 years ago, with accompanied decreased libido. However, until recently, he was able to achieve acceptable erectile capacity with medications. As part of his previous evaluations for erectile dysfunction, the patient had 2 total testosterone levels checked 6 months apart, both low at 150 ng/dL and 38.3 ng/dL (reference range, 220-892). The results of additional hormone studies are shown in the Table. Dr. Ananthakrishnan, can you help us interpret these laboratory results and tell us what tests you might order next?

►Sonia Ananthakrishnan, MD, Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Nutrition, Boston Medical Center (BMC) and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM): When patients present with signs of hypogonadism and an initial low morning testosterone levels, the next test should be a confirmatory repeat morning testosterone level as was done in this case. If this level is also low (for most assays < 300 ng/dL), further evaluation for primary vs secondary hypogonadism should be pursued with measurement of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone levels. Secondary hypogonadism should be suspected when these levels are low or inappropriately normal in the setting of a low testosterone level as in this patient. This patient does not appear to be on any medication or have reversible illnesses that we traditionally think of as possibly causing these hormone irregularities. Key examples include medications such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs, glucocorticoids, and opioids, as well as conditions such as hyperprolactinemia, sleep apnea, diabetes mellitus, anorexia nervosa, or other chronic systemic illnesses, including cirrhosis or lung disease. In this setting, further evaluation of the patient’s anterior pituitary function should be undertaken. Initial screening tests showed mildly elevated prolactin and low normal thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, with a relatively normal free thyroxine. Given these abnormalities in the context of the patient’s total testosterone level < 150 ng/dL, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the anterior pituitary is indicated, and what I would recommend next for evaluation of pituitary and/or hypothalamic tumor or infiltrative disease.1

►Dr. Bhatnagar: An MRI of the brain showed a large 2.7-cm sellar mass, with suprasellar extension and mass effect on the optic chiasm and pituitary infundibulum, partial extension into the right sphenoid sinus, and invasion into the right cavernous sinus. These findings were consistent with a pituitary macroadenoma. The patient was subsequently evaluated by a neurosurgeon who felt that because of the extension and compression of the mass, the patient would benefit from surgical resection.

Given his lower urinary tract symptoms, a prostate-specific antigen level was checked and returned elevated at 11.5 ng/mL. In the setting of these abnormalities, the patient underwent MRI of the abdomen, which noted a new 5.6-cm enhancing mass in the upper pole of his solitary right kidney, highly concerning for new RCC. After a multidisciplinary discussion, urology scheduled the patient for partial right nephrectomy first, with plans for pituitary resection only if the patient had adequate recovery following the urologic procedure.

Dr. Rifkin, this patient went straight from imaging to presumed diagnosis to planned surgical intervention without a confirmatory biopsy. In a patient who already has chronic kidney disease stage 4, why would we not want to pursue biopsy prior to this invasive procedure on his solitary kidney? In addition, given his baseline advanced renal disease, why pursue partial nephrectomy to delay initiation of hemodialysis instead of total nephrectomy and beginning hemodialysis?

►Ian Rifkin, MBBCh, PhD, MSc, Chief, Renal Section, VABHS, Section of Nephrology, BMC, and Associate Professor of Medicine, BUSM: In most cases, imaging alone is used to make a presumptive diagnosis of benign vs malignant renal masses. In one study, RCC was identified by MRI with 85% sensitivity and 76% specificity.2 However, as imaging and biopsy techniques have advanced, there are progressing discussions regarding the utility of biopsy. That being said, there are a number of situations in which patients currently undergo biopsy, particularly when there is diagnostic uncertainty.3 In this patient, with a history of RCC and imaging findings concerning for RCC, biopsy is unnecessary given the high clinical suspicion.

Regarding the choice of partial vs total nephrectomy, there are 2 important distinctions to be made. The first is that though it was previously felt that early initiation of dialysis improves survival, newer studies suggest that early initiation based off of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) offers no survival benefits compared to delayed initiation.4 Second, though there is less clinical data to support this, there is a signal toward the use of partial nephrectomy decreasing mortality compared to radical nephrectomy in management of RCC.5 In this patient, partial nephrectomy may not only increase rates of survival, but also delay initiation of dialysis.

►Dr. Bhatnagar: Prior to undergoing partial right nephrectomy, a morning cortisol level was found to be 5.8 μg/dL with an associated corticotropin (ACTH) level of 26 pg/mL. Dr. Ananthakrishnan, how would you interpret these laboratory results and what might you recommend prior to surgery?

►Dr. Ananthakrishnan: In a healthy patient, surgery often results in a several-fold increase in the secretion of cortisol to balance the unique stressors surgery places on the body.6 This patient is at increased risk for complete or partial adrenal insufficiency in the setting of both his pituitary macroadenoma as well as his previous left nephrectomy, which could have affected his left adrenal gland as well. Thus, this patient may not be able to mount the appropriate cortisol response needed to counter the stresses of surgery. His cortisol level is abnormally low for a morning value, with a relatively normal ACTH reference range of 6 to 50 pg/mL. He may have some degree of adrenal insufficiency, and thus will benefit from perioperative steroids.

►Dr. Bhatnagar: The patient was started on hydrocortisone and underwent a successful laparoscopic partial right nephrectomy. During the procedure, an estimated 2.5 L of blood was lost, with transfusion of 3 units of packed red blood cells. A surgical drain was left in the peritoneum. Postoperatively, he developed hypotension, requiring vasopressors and prolonged continuation of stress dosing of hydrocortisone. Over the next 4 days, the patient was weaned off vasopressors, and his creatinine level was noted to increase from a baseline of 1.8 mg/dL to 4.4 mg/dL.

Dr. Rifkin, how do you think about renal recovery in the patient postnephrectomy, and should we be concerned with the dramatic rise in his creatinine level?

►Dr. Rifkin: Removal of renal mass will result in an initial reduction of GFR proportional to the amount of functional renal tissue removed. However, in as early as 1 week, the residual nephrons begin to compensate through various mechanisms, such as modulation of efferent and afferent arterioles and renal tissue growth by hypertrophy and hyperplasia.7 In the acute setting, it may be difficult to distinguish an acute renal injury vs physiological GFR reduction postnephron loss, but often the initially elevated creatinine level may normalize/stabilize over time. Other markers of kidney function should concomitantly be monitored, including urine output, electrolyte/acid-base status, and urine sediment examination. In this patient, although his creatinine level may be elevated over the first few days, if his urine output remains robust and the urine sediment examination is normal, my concern for permanent kidney injury would be lessened.

►Dr. Bhatnagar: During the first 4 postoperative days the patient produced approximately 1 L of urine per day with a stable creatinine level. It is over this same time that the hydrocortisone was discontinued given improving hemodynamics. However, throughout postoperative day 5, the patient’s creatinine level acutely rose to a peak of 5.8 mg/dL. In addition, his urine output dramatically dropped to < 5 mL per hour, with blood clots noted in his Foley catheter. Dr. Rifkin, what is your differential for causing this acute change in both his creatinine level and urine output this far out from his procedure, and what might you do to help further evaluate?

►Dr. Rifkin: The most common cause of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients is acute tubular necrosis (ATN).8 However, in this patient, who was recovering well postoperatively, was hemodynamically stable with a robust urine output, and in whom no apparent cause for ATN could be identified, other diagnoses were more likely. Considering the abrupt onset of oligo-anuria, the most likely diagnosis was urinary tract obstruction, particularly given the frank blood and blood clots that were present in the urine. Additional possibilities might be a late surgical complication or infection. Surgical complications could range from direct damage to the renal parenchyma to urinary leakage into the peritoneum from the site of anastomosis or tissue injury. Infections introduced either intraoperatively or developed postoperatively could also cause this sudden drop in urine output, though one would expect more systemic symptoms with this. Given that this patient has a surgical drain in place in the peritoneum, I would recommend testing the creatinine level in the peritoneal fluid drainage. If it is comparable to serum levels, this would argue against a urine leak, as we would expect the level to be significantly elevated in a leak. In addition, he should have imaging of the urinary tract followed by procedures to decompress the presumed obstructed urinary tract. These procedures might include either cystoscopy with ureteral stent placement or percutaneous nephrostomy, depending on the result of the imaging.

►Dr. Bhatnagar: The creatinine level obtained from the surgical drain was roughly equivalent to the serum creatinine, decreasing suspicion for a urine leak as the cause of his findings. Cystoscopy with ureteral stent placement was performed with subsequent increase in both urine output and concomitant decrease in serum creatinine.

Around this time, the patient also began to note blurry vision. Evaluation revealed difficulty with visual field confrontation in the right lower quadrant, right eye ptosis, right eye impaired adduction, absent abduction and impaired upgaze, but intact downgaze. Diplopia was present with gaze in all directions. His constellation of physical examination findings were concerning for a pathologic lesion partially involving cranial nerves II and III, with definitive involvement of cranial nerve VI, but sparing of cranial nerve IV. Repeat MRI of the brain showed hemorrhage into the sellar mass, with ongoing mass effect on the optic chiasm and extension into the sinuses (eAppendix). These findings were consistent with pituitary apoplexy. Dr. Ananthakrishnan, can you tell us more about pituitary apoplexy?

►Dr. Ananthakrishnan: Pituitary apoplexy is a clinical syndrome resulting from acute hemorrhage or infarction of the pituitary gland. It typically occurs in patients with preexisting pituitary adenomas and is characterized by the onset of headache, fever, vomiting, meningismus, decreased consciousness, and sometimes death. In addition, given the location of the pituitary gland within the sella, rapid changes in size can result in compression of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI, as well as the optic chiasm, resulting in ophthalmoplegia and visual disturbances as seen in this patient.9

There are a multitude of causes of pituitary apoplexy, including alterations in coagulopathy, pituitary stimulation (eg, dynamic pituitary hormone testing), and both acute increases and decreases in blood flow.10 This patient likely had an ischemic event due to changes in vascular perfusion, spurred by both his blood loss intraoperatively and ongoing hematuria. Management of pituitary apoplexy is dependent on the patient’s hemodynamics, mass effect symptoms, electrolyte balances, and hormone dysfunction. The decision for conservative management vs surgical intervention should be made in consultation with both neurosurgery and endocrinology. Once the patient is hemodynamically stable, the next step in evaluating this patient should be repeating his hormone studies.

►Dr. Bhatnagar: An assessment of pituitary function was consistent with values obtained preoperatively. After multidisciplinary discussions, surgery was deferred, and hydrocortisone was reinitiated to reduce inflammation caused by bleeding into the mass. As the ophthalmoplegia improved, this was transitioned to dexamethasone.

Twelve days after admission, he was discharged to a subacute rehabilitation center, with improvement in his ophthalmoplegia and stabilization of his creatinine level and urine output.

►Anish Bhatnagar, MD, Chief Medical Resident, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC): The patient noted erectile dysfunction starting 4 years ago, with accompanied decreased libido. However, until recently, he was able to achieve acceptable erectile capacity with medications. As part of his previous evaluations for erectile dysfunction, the patient had 2 total testosterone levels checked 6 months apart, both low at 150 ng/dL and 38.3 ng/dL (reference range, 220-892). The results of additional hormone studies are shown in the Table. Dr. Ananthakrishnan, can you help us interpret these laboratory results and tell us what tests you might order next?

►Sonia Ananthakrishnan, MD, Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Nutrition, Boston Medical Center (BMC) and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM): When patients present with signs of hypogonadism and an initial low morning testosterone levels, the next test should be a confirmatory repeat morning testosterone level as was done in this case. If this level is also low (for most assays < 300 ng/dL), further evaluation for primary vs secondary hypogonadism should be pursued with measurement of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone levels. Secondary hypogonadism should be suspected when these levels are low or inappropriately normal in the setting of a low testosterone level as in this patient. This patient does not appear to be on any medication or have reversible illnesses that we traditionally think of as possibly causing these hormone irregularities. Key examples include medications such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs, glucocorticoids, and opioids, as well as conditions such as hyperprolactinemia, sleep apnea, diabetes mellitus, anorexia nervosa, or other chronic systemic illnesses, including cirrhosis or lung disease. In this setting, further evaluation of the patient’s anterior pituitary function should be undertaken. Initial screening tests showed mildly elevated prolactin and low normal thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, with a relatively normal free thyroxine. Given these abnormalities in the context of the patient’s total testosterone level < 150 ng/dL, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the anterior pituitary is indicated, and what I would recommend next for evaluation of pituitary and/or hypothalamic tumor or infiltrative disease.1

►Dr. Bhatnagar: An MRI of the brain showed a large 2.7-cm sellar mass, with suprasellar extension and mass effect on the optic chiasm and pituitary infundibulum, partial extension into the right sphenoid sinus, and invasion into the right cavernous sinus. These findings were consistent with a pituitary macroadenoma. The patient was subsequently evaluated by a neurosurgeon who felt that because of the extension and compression of the mass, the patient would benefit from surgical resection.

Given his lower urinary tract symptoms, a prostate-specific antigen level was checked and returned elevated at 11.5 ng/mL. In the setting of these abnormalities, the patient underwent MRI of the abdomen, which noted a new 5.6-cm enhancing mass in the upper pole of his solitary right kidney, highly concerning for new RCC. After a multidisciplinary discussion, urology scheduled the patient for partial right nephrectomy first, with plans for pituitary resection only if the patient had adequate recovery following the urologic procedure.

Dr. Rifkin, this patient went straight from imaging to presumed diagnosis to planned surgical intervention without a confirmatory biopsy. In a patient who already has chronic kidney disease stage 4, why would we not want to pursue biopsy prior to this invasive procedure on his solitary kidney? In addition, given his baseline advanced renal disease, why pursue partial nephrectomy to delay initiation of hemodialysis instead of total nephrectomy and beginning hemodialysis?

►Ian Rifkin, MBBCh, PhD, MSc, Chief, Renal Section, VABHS, Section of Nephrology, BMC, and Associate Professor of Medicine, BUSM: In most cases, imaging alone is used to make a presumptive diagnosis of benign vs malignant renal masses. In one study, RCC was identified by MRI with 85% sensitivity and 76% specificity.2 However, as imaging and biopsy techniques have advanced, there are progressing discussions regarding the utility of biopsy. That being said, there are a number of situations in which patients currently undergo biopsy, particularly when there is diagnostic uncertainty.3 In this patient, with a history of RCC and imaging findings concerning for RCC, biopsy is unnecessary given the high clinical suspicion.

Regarding the choice of partial vs total nephrectomy, there are 2 important distinctions to be made. The first is that though it was previously felt that early initiation of dialysis improves survival, newer studies suggest that early initiation based off of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) offers no survival benefits compared to delayed initiation.4 Second, though there is less clinical data to support this, there is a signal toward the use of partial nephrectomy decreasing mortality compared to radical nephrectomy in management of RCC.5 In this patient, partial nephrectomy may not only increase rates of survival, but also delay initiation of dialysis.

►Dr. Bhatnagar: Prior to undergoing partial right nephrectomy, a morning cortisol level was found to be 5.8 μg/dL with an associated corticotropin (ACTH) level of 26 pg/mL. Dr. Ananthakrishnan, how would you interpret these laboratory results and what might you recommend prior to surgery?

►Dr. Ananthakrishnan: In a healthy patient, surgery often results in a several-fold increase in the secretion of cortisol to balance the unique stressors surgery places on the body.6 This patient is at increased risk for complete or partial adrenal insufficiency in the setting of both his pituitary macroadenoma as well as his previous left nephrectomy, which could have affected his left adrenal gland as well. Thus, this patient may not be able to mount the appropriate cortisol response needed to counter the stresses of surgery. His cortisol level is abnormally low for a morning value, with a relatively normal ACTH reference range of 6 to 50 pg/mL. He may have some degree of adrenal insufficiency, and thus will benefit from perioperative steroids.