User login

NEED HAIR: Pinpointing the cause of a patient’s hair loss

Telogen effluvium (TE)—temporary hair loss due to the shedding of telogen (resting phase of hair cycle) hair after exposure to some form of stress—is one of the most common causes of diffuse non-scarring hair loss from the scalp.1 TE is more common than anagen (growing phase of hair cycle) hair loss.2 Hair loss can be triggered by numerous factors, including certain psychotropic medications.3,4 Mood stabilizers, such as valproic acid and lithium, are most commonly implicated. Hair loss also has been associated with the use of the first-generation antipsychotics haloperidol and chlorpromazine and the second-generation antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone.5-7 We recently cared for a woman with bipolar I disorder and generalized anxiety disorder who was prescribed lurasidone and later developed TE. Her hair loss completely resolved 4 months after lurasidone was discontinued.

TE can be triggered by events that interrupt the normal hair growth cycle. Typically, it is observed approximately 3 months after a triggering event and is usually self-limiting, lasting approximately 6 months.7 Diagnostic features include a strongly positive hair-pull test, a trichogram showing >25% telogen hair, and a biopsy showing an increase in telogen follicles.8,9 To conduct the hair-pull test, grasp approximately 40 to 60 hairs between the thumb and forefinger while slightly stretching the scalp to allow your fingers to slide along the length of the hair. Usually only 2 to 3 hairs in the telogen phase can be plucked via this method; if >10% of the hairs grasped can be plucked, this indicates a pathologic process.10

Significant hair loss, particularly among women, is a distressing adverse effect that can be an important moderator of compliance, treatment adherence, and relapse. To help clinicians narrow down the wide range of potential causes of a patient’s hair loss, we created the mnemonic NEED HAIR.

Nutritional: Iron deficiency anemia, a “crash” diet, zinc deficiency, vitamin B6 or B12 deficiency, chronic starvation, diarrhea, hypoproteinemia (metabolic or dietary origin), malabsorption, or heavy metal ingestion.1

Endocrine: Thyroid disorders and the early stage of androgenic alopecia.8,11

Environmental: Stress from a severe febrile illness, emotional stress, serious injuries, major surgery, large hemorrhage, and difficult labor.12

Drugs: Oral contraceptives, antithyroid drugs, retinoids (etretinate and acitretin), anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antipsychotics, hypolipidemic drugs, anticoagulants, antihypertensives (beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors), and cytotoxic drugs.1,4-7

Continue to: Hormonal fluctuations

Hormonal fluctuations: Polycystic ovarian syndrome and postpartum hormonal changes.11

Autoimmune: Lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, scleroderma, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Sjögren’s syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, and autoimmune atrophic gastritis.12,13

Infections and chronic illnesses: Fungal infections (eg, tinea capitis), human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, typhoid, malaria, tuberculosis, malignancy, renal failure, hepatic failure, and other chronic illnesses.1,9

Radiation: Radiation treatment and excessive UV exposure.12,14,15

Treatment for hair loss depends on the specific caus

1. Grover C, Khurana A. Telogen effluvium. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79(5):591-603.

2. Harrison S, Bergfeld W. Diffuse hair loss: its triggers and management. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(6):361-367.

3. Gautam M. Alopecia due to psychotropic medications. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33(5):631-637.

4. Mercke Y, Sheng H, Khan T, et al. Hair loss in psychopharmacology. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2000;12(1):35-42.

5. Kubota T, Ishikura T, Jibiki I. Alopecia areata associated with haloperidol. Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1994;48(3):579-581.

6. McLean RM, Harrison-Woolrych M. Alopecia associated with quetiapine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2007;22(2):117-9.

7. Kulolu M, Korkmaz S, Kilic N, et al. Olanzapine induced hair loss: a case report. Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2012;22(4):362-365.

8. Malkud S. Telogen effluvium: a review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(9):WE01-WE03.

9. Shrivastava SB. Diffuse hair loss in an adult female: approach to diagnosis and management. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2009;75(1):20-28; quiz 27-28.

10. Piérard GE, Piérard-Franchimont C, Marks R, et al; EEMCO group (European Expert Group on Efficacy Measurement of Cosmetics and Other Topical Products). EEMCO guidance for the assessment of hair shedding and alopecia. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;17(2):98-110.

11. Mirallas O, Grimalt R. The postpartum telogen effluvium fallacy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;1(4):198-201.

12. Rebora A. Proposing a simpler classification of telogen effluvium. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;2(1-2):35-38.

13. Cassano N, Amerio P, D’Ovidio R, et al. Hair disorders associated with autoimmune connective tissue diseases. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014;149(5):555-565.

14. Trüeb RM. Telogen effluvium: is there a need for a new classification? Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;2(1-2):39-44.

15. Ali SY, Singh G. Radiation-induced alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2010;2(2):118-119.

Telogen effluvium (TE)—temporary hair loss due to the shedding of telogen (resting phase of hair cycle) hair after exposure to some form of stress—is one of the most common causes of diffuse non-scarring hair loss from the scalp.1 TE is more common than anagen (growing phase of hair cycle) hair loss.2 Hair loss can be triggered by numerous factors, including certain psychotropic medications.3,4 Mood stabilizers, such as valproic acid and lithium, are most commonly implicated. Hair loss also has been associated with the use of the first-generation antipsychotics haloperidol and chlorpromazine and the second-generation antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone.5-7 We recently cared for a woman with bipolar I disorder and generalized anxiety disorder who was prescribed lurasidone and later developed TE. Her hair loss completely resolved 4 months after lurasidone was discontinued.

TE can be triggered by events that interrupt the normal hair growth cycle. Typically, it is observed approximately 3 months after a triggering event and is usually self-limiting, lasting approximately 6 months.7 Diagnostic features include a strongly positive hair-pull test, a trichogram showing >25% telogen hair, and a biopsy showing an increase in telogen follicles.8,9 To conduct the hair-pull test, grasp approximately 40 to 60 hairs between the thumb and forefinger while slightly stretching the scalp to allow your fingers to slide along the length of the hair. Usually only 2 to 3 hairs in the telogen phase can be plucked via this method; if >10% of the hairs grasped can be plucked, this indicates a pathologic process.10

Significant hair loss, particularly among women, is a distressing adverse effect that can be an important moderator of compliance, treatment adherence, and relapse. To help clinicians narrow down the wide range of potential causes of a patient’s hair loss, we created the mnemonic NEED HAIR.

Nutritional: Iron deficiency anemia, a “crash” diet, zinc deficiency, vitamin B6 or B12 deficiency, chronic starvation, diarrhea, hypoproteinemia (metabolic or dietary origin), malabsorption, or heavy metal ingestion.1

Endocrine: Thyroid disorders and the early stage of androgenic alopecia.8,11

Environmental: Stress from a severe febrile illness, emotional stress, serious injuries, major surgery, large hemorrhage, and difficult labor.12

Drugs: Oral contraceptives, antithyroid drugs, retinoids (etretinate and acitretin), anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antipsychotics, hypolipidemic drugs, anticoagulants, antihypertensives (beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors), and cytotoxic drugs.1,4-7

Continue to: Hormonal fluctuations

Hormonal fluctuations: Polycystic ovarian syndrome and postpartum hormonal changes.11

Autoimmune: Lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, scleroderma, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Sjögren’s syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, and autoimmune atrophic gastritis.12,13

Infections and chronic illnesses: Fungal infections (eg, tinea capitis), human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, typhoid, malaria, tuberculosis, malignancy, renal failure, hepatic failure, and other chronic illnesses.1,9

Radiation: Radiation treatment and excessive UV exposure.12,14,15

Treatment for hair loss depends on the specific caus

Telogen effluvium (TE)—temporary hair loss due to the shedding of telogen (resting phase of hair cycle) hair after exposure to some form of stress—is one of the most common causes of diffuse non-scarring hair loss from the scalp.1 TE is more common than anagen (growing phase of hair cycle) hair loss.2 Hair loss can be triggered by numerous factors, including certain psychotropic medications.3,4 Mood stabilizers, such as valproic acid and lithium, are most commonly implicated. Hair loss also has been associated with the use of the first-generation antipsychotics haloperidol and chlorpromazine and the second-generation antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone.5-7 We recently cared for a woman with bipolar I disorder and generalized anxiety disorder who was prescribed lurasidone and later developed TE. Her hair loss completely resolved 4 months after lurasidone was discontinued.

TE can be triggered by events that interrupt the normal hair growth cycle. Typically, it is observed approximately 3 months after a triggering event and is usually self-limiting, lasting approximately 6 months.7 Diagnostic features include a strongly positive hair-pull test, a trichogram showing >25% telogen hair, and a biopsy showing an increase in telogen follicles.8,9 To conduct the hair-pull test, grasp approximately 40 to 60 hairs between the thumb and forefinger while slightly stretching the scalp to allow your fingers to slide along the length of the hair. Usually only 2 to 3 hairs in the telogen phase can be plucked via this method; if >10% of the hairs grasped can be plucked, this indicates a pathologic process.10

Significant hair loss, particularly among women, is a distressing adverse effect that can be an important moderator of compliance, treatment adherence, and relapse. To help clinicians narrow down the wide range of potential causes of a patient’s hair loss, we created the mnemonic NEED HAIR.

Nutritional: Iron deficiency anemia, a “crash” diet, zinc deficiency, vitamin B6 or B12 deficiency, chronic starvation, diarrhea, hypoproteinemia (metabolic or dietary origin), malabsorption, or heavy metal ingestion.1

Endocrine: Thyroid disorders and the early stage of androgenic alopecia.8,11

Environmental: Stress from a severe febrile illness, emotional stress, serious injuries, major surgery, large hemorrhage, and difficult labor.12

Drugs: Oral contraceptives, antithyroid drugs, retinoids (etretinate and acitretin), anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antipsychotics, hypolipidemic drugs, anticoagulants, antihypertensives (beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors), and cytotoxic drugs.1,4-7

Continue to: Hormonal fluctuations

Hormonal fluctuations: Polycystic ovarian syndrome and postpartum hormonal changes.11

Autoimmune: Lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, scleroderma, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Sjögren’s syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, and autoimmune atrophic gastritis.12,13

Infections and chronic illnesses: Fungal infections (eg, tinea capitis), human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, typhoid, malaria, tuberculosis, malignancy, renal failure, hepatic failure, and other chronic illnesses.1,9

Radiation: Radiation treatment and excessive UV exposure.12,14,15

Treatment for hair loss depends on the specific caus

1. Grover C, Khurana A. Telogen effluvium. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79(5):591-603.

2. Harrison S, Bergfeld W. Diffuse hair loss: its triggers and management. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(6):361-367.

3. Gautam M. Alopecia due to psychotropic medications. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33(5):631-637.

4. Mercke Y, Sheng H, Khan T, et al. Hair loss in psychopharmacology. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2000;12(1):35-42.

5. Kubota T, Ishikura T, Jibiki I. Alopecia areata associated with haloperidol. Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1994;48(3):579-581.

6. McLean RM, Harrison-Woolrych M. Alopecia associated with quetiapine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2007;22(2):117-9.

7. Kulolu M, Korkmaz S, Kilic N, et al. Olanzapine induced hair loss: a case report. Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2012;22(4):362-365.

8. Malkud S. Telogen effluvium: a review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(9):WE01-WE03.

9. Shrivastava SB. Diffuse hair loss in an adult female: approach to diagnosis and management. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2009;75(1):20-28; quiz 27-28.

10. Piérard GE, Piérard-Franchimont C, Marks R, et al; EEMCO group (European Expert Group on Efficacy Measurement of Cosmetics and Other Topical Products). EEMCO guidance for the assessment of hair shedding and alopecia. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;17(2):98-110.

11. Mirallas O, Grimalt R. The postpartum telogen effluvium fallacy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;1(4):198-201.

12. Rebora A. Proposing a simpler classification of telogen effluvium. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;2(1-2):35-38.

13. Cassano N, Amerio P, D’Ovidio R, et al. Hair disorders associated with autoimmune connective tissue diseases. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014;149(5):555-565.

14. Trüeb RM. Telogen effluvium: is there a need for a new classification? Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;2(1-2):39-44.

15. Ali SY, Singh G. Radiation-induced alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2010;2(2):118-119.

1. Grover C, Khurana A. Telogen effluvium. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79(5):591-603.

2. Harrison S, Bergfeld W. Diffuse hair loss: its triggers and management. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(6):361-367.

3. Gautam M. Alopecia due to psychotropic medications. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33(5):631-637.

4. Mercke Y, Sheng H, Khan T, et al. Hair loss in psychopharmacology. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2000;12(1):35-42.

5. Kubota T, Ishikura T, Jibiki I. Alopecia areata associated with haloperidol. Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1994;48(3):579-581.

6. McLean RM, Harrison-Woolrych M. Alopecia associated with quetiapine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2007;22(2):117-9.

7. Kulolu M, Korkmaz S, Kilic N, et al. Olanzapine induced hair loss: a case report. Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2012;22(4):362-365.

8. Malkud S. Telogen effluvium: a review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(9):WE01-WE03.

9. Shrivastava SB. Diffuse hair loss in an adult female: approach to diagnosis and management. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2009;75(1):20-28; quiz 27-28.

10. Piérard GE, Piérard-Franchimont C, Marks R, et al; EEMCO group (European Expert Group on Efficacy Measurement of Cosmetics and Other Topical Products). EEMCO guidance for the assessment of hair shedding and alopecia. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;17(2):98-110.

11. Mirallas O, Grimalt R. The postpartum telogen effluvium fallacy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;1(4):198-201.

12. Rebora A. Proposing a simpler classification of telogen effluvium. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;2(1-2):35-38.

13. Cassano N, Amerio P, D’Ovidio R, et al. Hair disorders associated with autoimmune connective tissue diseases. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014;149(5):555-565.

14. Trüeb RM. Telogen effluvium: is there a need for a new classification? Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;2(1-2):39-44.

15. Ali SY, Singh G. Radiation-induced alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2010;2(2):118-119.

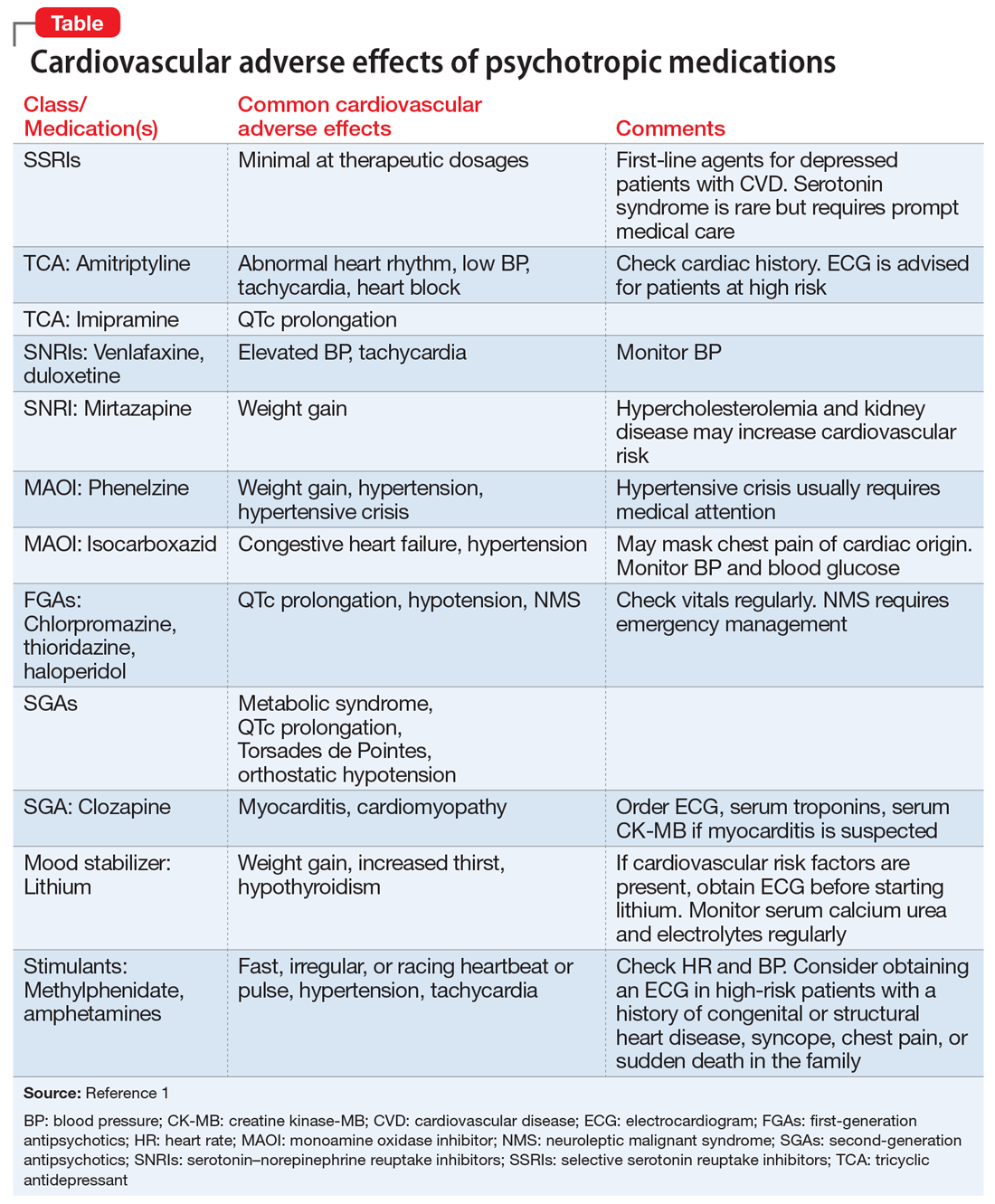

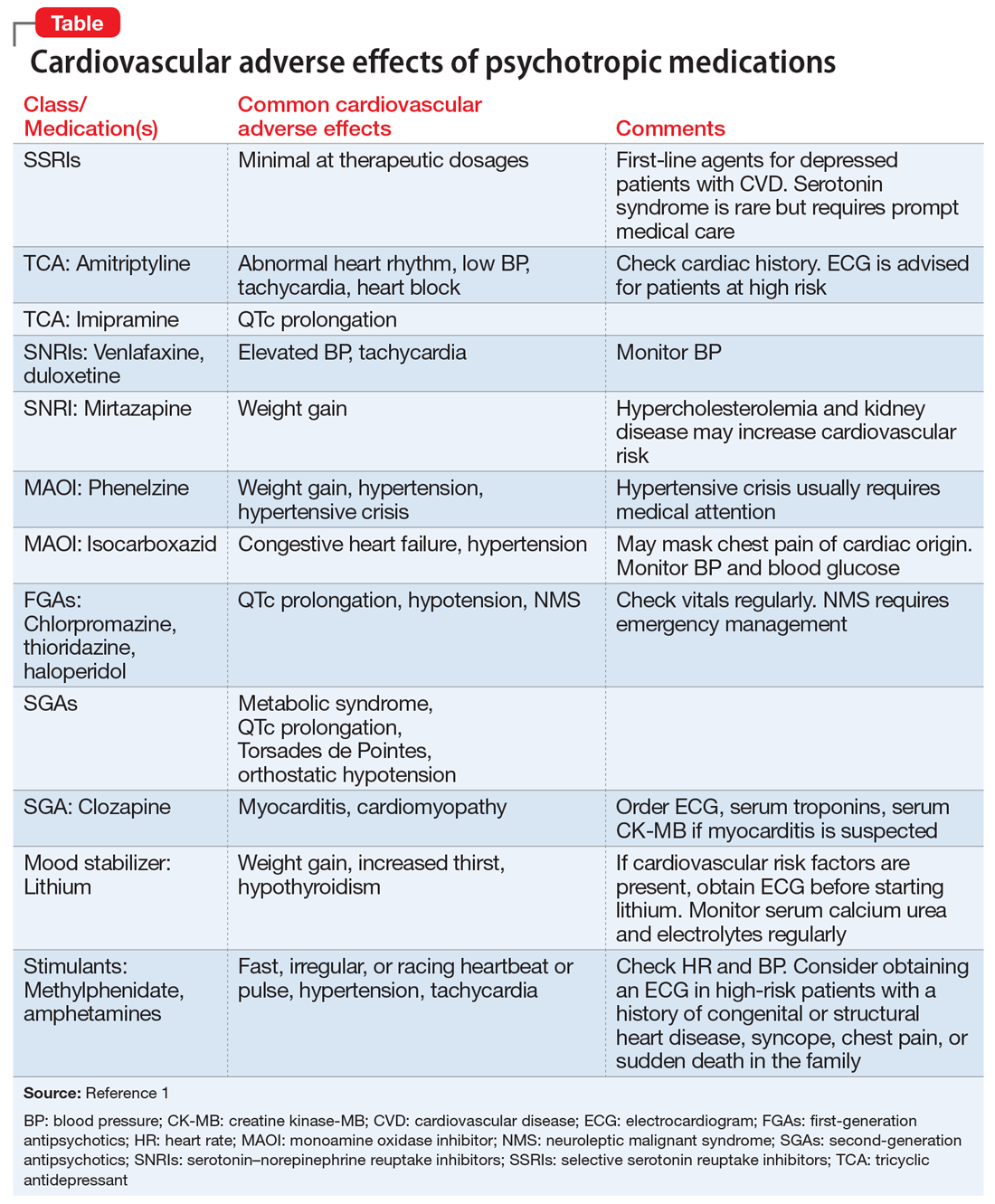

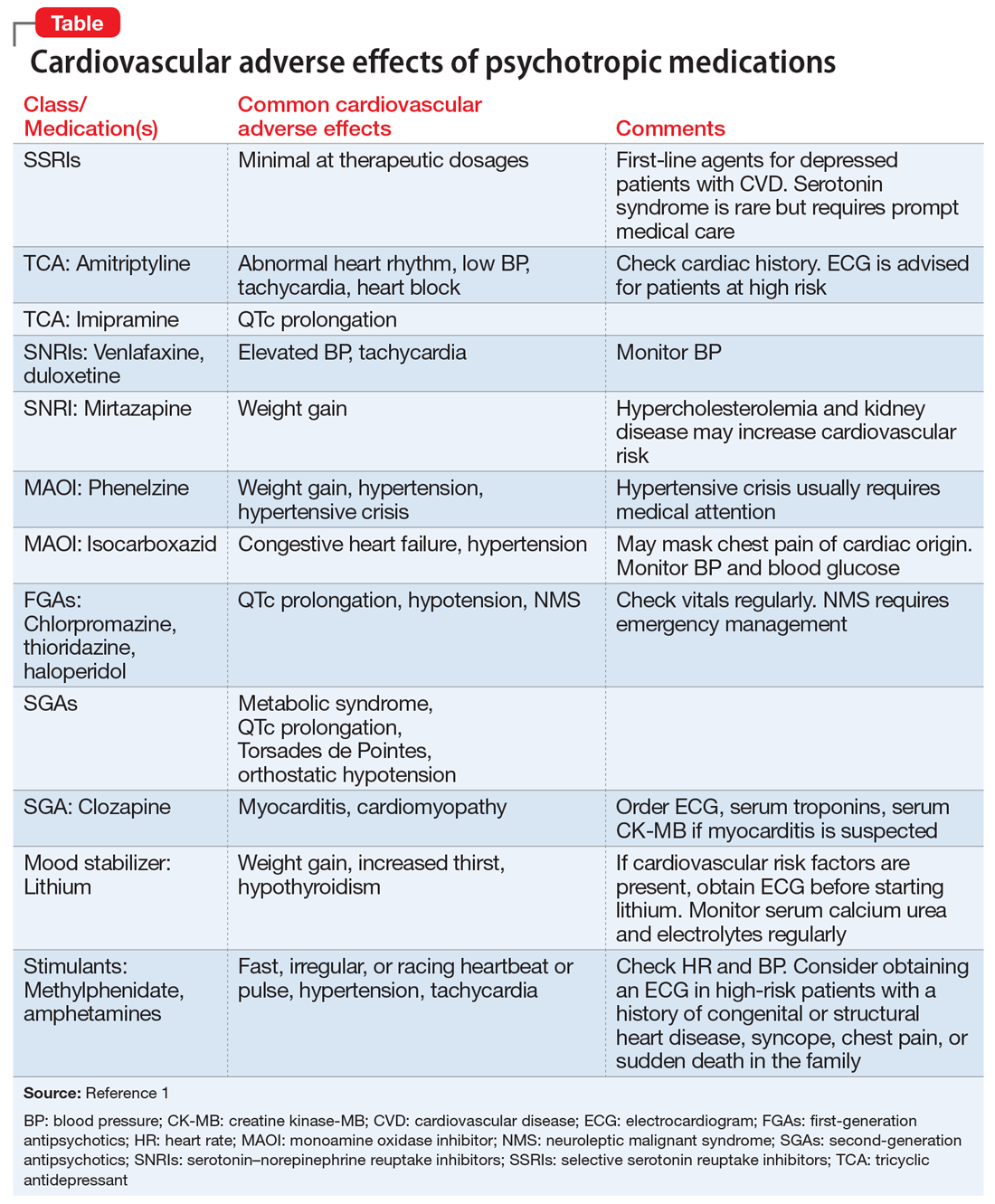

Cardiovascular adverse effects of psychotropics: What to look for

Most patients who take psychotropic medications are at low risk for cardiovascular adverse effects from these medications, and require only routine monitoring. However, patients with severe mental illness, those with a personal or family history of cardiovascular disease, or those receiving high doses or multiple medications are considered at high risk for morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular adverse effects. Such patients may need more careful cardiovascular monitoring.

To help identify important cardiovascular-related adverse effects of various psychotropics, we summarize these risks, and offer guidance about what you can do when your patient experiences them (Table).1

Antipsychotics and metabolic syndrome

Patients who take antipsychotics should be monitored for metabolic syndrome. The presence of 3 of the following 5 parameters is considered positive for metabolic syndrome2:

- fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c ≥5.6%

- blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg

- triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL

- high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- waist circumference ≥102 cm in men or ≥88 cm in women.

Stimulants and sudden cardiac death

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) in children and adolescents who take stimulants to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is rare. For these patients, the risk of SCD is no higher than that of the general population.3 For patients who do not have any known cardiac risk factors, the American Academy of Pediatrics does not recommend performing any cardiac tests before starting stimulants.3

1. Mackin P. Cardiac side effects of psychiatric drugs. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(suppl 1):S3-S14.

2. Grundy SM, Brewer HB Jr, Cleeman JI, et al; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(2):e13-e18.

3. American Academy of Pediatrics Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. Classifying recommendations for clinical practice guidelines. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):874-877.

Most patients who take psychotropic medications are at low risk for cardiovascular adverse effects from these medications, and require only routine monitoring. However, patients with severe mental illness, those with a personal or family history of cardiovascular disease, or those receiving high doses or multiple medications are considered at high risk for morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular adverse effects. Such patients may need more careful cardiovascular monitoring.

To help identify important cardiovascular-related adverse effects of various psychotropics, we summarize these risks, and offer guidance about what you can do when your patient experiences them (Table).1

Antipsychotics and metabolic syndrome

Patients who take antipsychotics should be monitored for metabolic syndrome. The presence of 3 of the following 5 parameters is considered positive for metabolic syndrome2:

- fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c ≥5.6%

- blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg

- triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL

- high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- waist circumference ≥102 cm in men or ≥88 cm in women.

Stimulants and sudden cardiac death

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) in children and adolescents who take stimulants to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is rare. For these patients, the risk of SCD is no higher than that of the general population.3 For patients who do not have any known cardiac risk factors, the American Academy of Pediatrics does not recommend performing any cardiac tests before starting stimulants.3

Most patients who take psychotropic medications are at low risk for cardiovascular adverse effects from these medications, and require only routine monitoring. However, patients with severe mental illness, those with a personal or family history of cardiovascular disease, or those receiving high doses or multiple medications are considered at high risk for morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular adverse effects. Such patients may need more careful cardiovascular monitoring.

To help identify important cardiovascular-related adverse effects of various psychotropics, we summarize these risks, and offer guidance about what you can do when your patient experiences them (Table).1

Antipsychotics and metabolic syndrome

Patients who take antipsychotics should be monitored for metabolic syndrome. The presence of 3 of the following 5 parameters is considered positive for metabolic syndrome2:

- fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c ≥5.6%

- blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg

- triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL

- high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- waist circumference ≥102 cm in men or ≥88 cm in women.

Stimulants and sudden cardiac death

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) in children and adolescents who take stimulants to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is rare. For these patients, the risk of SCD is no higher than that of the general population.3 For patients who do not have any known cardiac risk factors, the American Academy of Pediatrics does not recommend performing any cardiac tests before starting stimulants.3

1. Mackin P. Cardiac side effects of psychiatric drugs. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(suppl 1):S3-S14.

2. Grundy SM, Brewer HB Jr, Cleeman JI, et al; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(2):e13-e18.

3. American Academy of Pediatrics Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. Classifying recommendations for clinical practice guidelines. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):874-877.

1. Mackin P. Cardiac side effects of psychiatric drugs. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(suppl 1):S3-S14.

2. Grundy SM, Brewer HB Jr, Cleeman JI, et al; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(2):e13-e18.

3. American Academy of Pediatrics Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. Classifying recommendations for clinical practice guidelines. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):874-877.

Working at a long-term psychiatric hospital? Consider your patient’s point of view

Working at a long-term psychiatric hospital can present challenges similar to those found in other institutions, such as correctional facilities1; however, in this setting, additional obstacles that could affect treatment may not readily come to mind. Following the 2 simple approaches described here can help you to understand your patient’s point of view and improve the treatment relationship.

Allow patients some control. Many patients in long-term psychiatric hospitals are prescribed medications that can result in metabolic complications such as weight gain or hyperlipidemia. To avoid these complications, we may need to institute dietary restrictions. Despite our explanations of why these restrictions are necessary, some patients may continue to insist on eating food that we believe will worsen their physical health; they may feel that they have little control in their lives and have nothing to look forward to except for what they can eat.2

For patients in long-term psychiatric hospitals, everyday life usually is structured from morning to evening. This includes when meals and snacks are served, as well as what they are allowed to eat. Food is a basic human necessity, and we often forget its psychological significance. Because most patients can control what they put in their mouths, food allows them to exert control in an environment where they may believe they have no influence. This may explain why patients insist on certain meals, purchase unhealthy food, or engage in a surreptitious snack distribution system with other patients. We usually can decide what and when we eat, but many of our hospitalized patients do not have that opportunity. Within reason, negotiating meals and snacks could provide patients with a sense of control, and might increase treatment compliance.2

Mind what you say. At the hospital, patients are acutely aware that we are there for a short period each day. For these patients, the hospital serves as their home. Many will live there for months to years; some will spend the remainder of their lives there. The way these patients view us can become adversely affected when they see that we occasionally bring a negative attitude toward having to spend the day in their living space, telling them how to behave and what to do. This daily temporary relationship between hospital staff and patients can greatly affect treatment.

Although the hospital can serve as a home, patients do not have input into how we should behave in their home. Be mindful of your actions and the comments you make while in the hospital. We would not appreciate someone making a negative comment about our homes, so it is likely that our patients do not want to hear us complain about the hospital. Furthermore, they likely do not enjoy hearing hospital staff discussing plans they have made in their personal lives. Many patients do not enjoy being in the hospital, and they could view such expressions as “rubbing it in,” which could adversely affect treatment.

1. Khajuria K. CORRECT: insights into working at correctional facilities. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):54-55.

2. Joshi KG. Can I have cheese on my ham sandwich? BMJ. 2016;355:i6024. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6024.

Working at a long-term psychiatric hospital can present challenges similar to those found in other institutions, such as correctional facilities1; however, in this setting, additional obstacles that could affect treatment may not readily come to mind. Following the 2 simple approaches described here can help you to understand your patient’s point of view and improve the treatment relationship.

Allow patients some control. Many patients in long-term psychiatric hospitals are prescribed medications that can result in metabolic complications such as weight gain or hyperlipidemia. To avoid these complications, we may need to institute dietary restrictions. Despite our explanations of why these restrictions are necessary, some patients may continue to insist on eating food that we believe will worsen their physical health; they may feel that they have little control in their lives and have nothing to look forward to except for what they can eat.2

For patients in long-term psychiatric hospitals, everyday life usually is structured from morning to evening. This includes when meals and snacks are served, as well as what they are allowed to eat. Food is a basic human necessity, and we often forget its psychological significance. Because most patients can control what they put in their mouths, food allows them to exert control in an environment where they may believe they have no influence. This may explain why patients insist on certain meals, purchase unhealthy food, or engage in a surreptitious snack distribution system with other patients. We usually can decide what and when we eat, but many of our hospitalized patients do not have that opportunity. Within reason, negotiating meals and snacks could provide patients with a sense of control, and might increase treatment compliance.2

Mind what you say. At the hospital, patients are acutely aware that we are there for a short period each day. For these patients, the hospital serves as their home. Many will live there for months to years; some will spend the remainder of their lives there. The way these patients view us can become adversely affected when they see that we occasionally bring a negative attitude toward having to spend the day in their living space, telling them how to behave and what to do. This daily temporary relationship between hospital staff and patients can greatly affect treatment.

Although the hospital can serve as a home, patients do not have input into how we should behave in their home. Be mindful of your actions and the comments you make while in the hospital. We would not appreciate someone making a negative comment about our homes, so it is likely that our patients do not want to hear us complain about the hospital. Furthermore, they likely do not enjoy hearing hospital staff discussing plans they have made in their personal lives. Many patients do not enjoy being in the hospital, and they could view such expressions as “rubbing it in,” which could adversely affect treatment.

Working at a long-term psychiatric hospital can present challenges similar to those found in other institutions, such as correctional facilities1; however, in this setting, additional obstacles that could affect treatment may not readily come to mind. Following the 2 simple approaches described here can help you to understand your patient’s point of view and improve the treatment relationship.

Allow patients some control. Many patients in long-term psychiatric hospitals are prescribed medications that can result in metabolic complications such as weight gain or hyperlipidemia. To avoid these complications, we may need to institute dietary restrictions. Despite our explanations of why these restrictions are necessary, some patients may continue to insist on eating food that we believe will worsen their physical health; they may feel that they have little control in their lives and have nothing to look forward to except for what they can eat.2

For patients in long-term psychiatric hospitals, everyday life usually is structured from morning to evening. This includes when meals and snacks are served, as well as what they are allowed to eat. Food is a basic human necessity, and we often forget its psychological significance. Because most patients can control what they put in their mouths, food allows them to exert control in an environment where they may believe they have no influence. This may explain why patients insist on certain meals, purchase unhealthy food, or engage in a surreptitious snack distribution system with other patients. We usually can decide what and when we eat, but many of our hospitalized patients do not have that opportunity. Within reason, negotiating meals and snacks could provide patients with a sense of control, and might increase treatment compliance.2

Mind what you say. At the hospital, patients are acutely aware that we are there for a short period each day. For these patients, the hospital serves as their home. Many will live there for months to years; some will spend the remainder of their lives there. The way these patients view us can become adversely affected when they see that we occasionally bring a negative attitude toward having to spend the day in their living space, telling them how to behave and what to do. This daily temporary relationship between hospital staff and patients can greatly affect treatment.

Although the hospital can serve as a home, patients do not have input into how we should behave in their home. Be mindful of your actions and the comments you make while in the hospital. We would not appreciate someone making a negative comment about our homes, so it is likely that our patients do not want to hear us complain about the hospital. Furthermore, they likely do not enjoy hearing hospital staff discussing plans they have made in their personal lives. Many patients do not enjoy being in the hospital, and they could view such expressions as “rubbing it in,” which could adversely affect treatment.

1. Khajuria K. CORRECT: insights into working at correctional facilities. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):54-55.

2. Joshi KG. Can I have cheese on my ham sandwich? BMJ. 2016;355:i6024. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6024.

1. Khajuria K. CORRECT: insights into working at correctional facilities. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):54-55.

2. Joshi KG. Can I have cheese on my ham sandwich? BMJ. 2016;355:i6024. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6024.

Helping patients quit smoking: Lessons from the EAGLES trial

Psychiatrists often fail to adequately address their patients’ smoking, and often underestimate the impact of ongoing tobacco use. Evidence suggests that heavy smoking is a risk factor for major depressive disorder; it also is associated with increased suicidal ideations and attempts.1,2 Tobacco use also has a mood-altering impact that can change the trajectory of mental illness, and alters the metabolism of most psychotropics.

Previously, psychiatrists may have been reluctant to prescribe the most effective interventions for smoking cessation—varenicline and bupropion—because these medications carried an FDA “black-box” warning of neuropsychiatric adverse effects, including increased aggression and suicidality. However,

The EAGLES trial was a large, multi-site global trial that included patients with and without mental illness. Its primary objective was to assess the risk of “clinically significant” adverse effects for individuals receiving varenicline, bupropion, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), or placebo, and whether having a history of psychiatric conditions increased the risk of developing adverse effects when taking these therapies. Overall, 2% of smokers without mental illness experienced adverse effects, compared with 5% to 7% in the psychiatric cohort, regardless of treatment arm. The rate of neuropsychiatric events and scores on suicide severity scales were similar across treatment arms in both cohorts.3

We should take lessons from the EAGLES trial. We propose that clinicians ask themselves the following 6 questions when forming a treatment plan to address their patients’ tobacco use:

1. Does the patient meet DSM-5 criteria for nicotine use disorder and, if yes, what is the severity of his or her nicotine dependence? The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)5 is a 6-question instrument for evaluating the quantity of cigarette consumption, compulsion to use, and dependence. It provides clinicians with guidelines on preventing withdrawal by implementing NRTs, such as lozenges, an inhaler, patches, and/or gum. A score of 1 to 2 (low dependence) indicates that no NRT is needed; a score of 3 to 4 (low to moderate dependence) requires 1 NRT; and scores of 5 to 7 (moderate dependence) and ≥8 (high dependence) require a combination of NRTs.

In the EAGLES trial, all participants smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day, and had moderate dependence, with an average FTND score of 5 to 6.

2. What stage of change is the patient in, and how many times has he or she attempted to quit? Based on the answers, motivational interviewing may be appropriate.

Continue to: In the EAGLES trial...

In the EAGLES trial, the participants were motivated individuals who had on average 3 past quit attempts. Research suggests that even patients who have a serious mental illness can be motivated to quit (Box).6-9

Box

Mental illness and motivation to quit smoking

In the past, clinicians may have believed that many individuals with mental illness typically weren’t motivated to quit smoking. We now know this is not the case and that such patients’ motivation is similar to that of the general population, and the reasons driving their desire are the same—health concerns and social influences.6 Even individuals with serious mental illness such as schizophrenia who have a long history of tobacco use are highly motivated and persistent in their attempts to quit.7,8 The prevalence of future “readiness to quit” among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and depression ranges from 21% to 49%, which is similar to that among the general population (26% to 41%). Evidence also suggests that motivation translates into successful quitting, with quit rates of up to 22% for people with mental illness who use a combination of psychosocial and pharmacological interventions.9

3. What is the patient’s mental health status? What is the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis and how clinically stable is he or she? What is his or her suicide risk? Consider using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).10

In the EAGLES trial, the psychiatric cohort included only patients who had been clinically stable for the past 6 months and had received the same medication regimen for at least the past 3 months, with no expected changes for 12 weeks. Patients with certain diagnoses were excluded (eg, delusional disorder, schizophreniform disorder, impulse control disorders), and only 1% had a personality disorder, which increases mood lability and likelihood of suicidality behavior.

Continue to: Does the patient have another comorbid substance use disorder?

4. Does the patient have another comorbid substance use disorder? In the EAGLES trial, those who had active substance use in the past year or were receiving methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone were excluded.

5. Does the patient have any medical conditions? Does he or she have a history of seizures or eating disorders? It is important to determine if a patient has a seizure disorder or another medical condition that is a contraindication for using varenicline or bupropion.

I

6. Have you discussed smoking cessation and a treatment plan with the patient at every visit? In the EAGLES trial, participants received 10-minute cessation counseling at every outpatient visit.

Continue to: When it comes time to select a medication regimen...

When it comes time to select a medication regimen, for bupropion, consider starting the patient with 150 mg/d, and increasing the dose to 150 mg twice a day 4 days later. The target quit date should be 7 days after starting the medication. Monitor the patient for symptoms of anxiety and insomnia.

For varenicline, start the patient at 0.5 mg/d, and increase the dose to 0.5 mg twice a day 4 days later. After another 4 days, increase the dose to 1 mg twice a day. Set a target quit date for 7 days after starting medication. Monitor the patient for nausea, insomnia, and abnormal dreams.

1. Khaled SM, Bulloch AG, Williams JV, et al. Persistent heavy smoking as risk factor for major depression (MD) incidence--evidence from a longitudinal Canadian cohort of the National Population Health Survey. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(4):436-443.

2. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C. Tobacco use and 12-month suicidality among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(1):39-48.

3. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520.

4. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises description of mental health side effects of the stop-smoking medicines Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion) to reflect clinical trial findings. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm532221.htm. Accessed April 16, 2018.

5. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The Fagerström Test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119-1127.

6. Moeller‐Saxone K. Cigarette smoking and interest in quitting among consumers at a psychiatric disability rehabilitation and support service in Victoria. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32(5):479-481.

7. Evins AE, Cather C, Rigotti NA, et al. Two-year follow-up of a smoking cessation trial in patients with schizophrenia: increased rates of smoking cessation and reduction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):307-311; quiz 452-453.

8. Weiner E, Ahmed S. Smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Cur Psychiatry Rev. 2013;9(2):164-172.

9. Banham L, Gilbody S. Smoking cessation in severe mental illness: what works? Addiction. 2010;105(7):1176-1189.

10. Posner K, Brent D, Lucas C, et al. Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). The Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, Inc. http://cssrs.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/C-SSRS_Pediatric-SLC_11.14.16.pdf. Updated June 23, 2010. Accessed April 26, 2018.

Psychiatrists often fail to adequately address their patients’ smoking, and often underestimate the impact of ongoing tobacco use. Evidence suggests that heavy smoking is a risk factor for major depressive disorder; it also is associated with increased suicidal ideations and attempts.1,2 Tobacco use also has a mood-altering impact that can change the trajectory of mental illness, and alters the metabolism of most psychotropics.

Previously, psychiatrists may have been reluctant to prescribe the most effective interventions for smoking cessation—varenicline and bupropion—because these medications carried an FDA “black-box” warning of neuropsychiatric adverse effects, including increased aggression and suicidality. However,

The EAGLES trial was a large, multi-site global trial that included patients with and without mental illness. Its primary objective was to assess the risk of “clinically significant” adverse effects for individuals receiving varenicline, bupropion, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), or placebo, and whether having a history of psychiatric conditions increased the risk of developing adverse effects when taking these therapies. Overall, 2% of smokers without mental illness experienced adverse effects, compared with 5% to 7% in the psychiatric cohort, regardless of treatment arm. The rate of neuropsychiatric events and scores on suicide severity scales were similar across treatment arms in both cohorts.3

We should take lessons from the EAGLES trial. We propose that clinicians ask themselves the following 6 questions when forming a treatment plan to address their patients’ tobacco use:

1. Does the patient meet DSM-5 criteria for nicotine use disorder and, if yes, what is the severity of his or her nicotine dependence? The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)5 is a 6-question instrument for evaluating the quantity of cigarette consumption, compulsion to use, and dependence. It provides clinicians with guidelines on preventing withdrawal by implementing NRTs, such as lozenges, an inhaler, patches, and/or gum. A score of 1 to 2 (low dependence) indicates that no NRT is needed; a score of 3 to 4 (low to moderate dependence) requires 1 NRT; and scores of 5 to 7 (moderate dependence) and ≥8 (high dependence) require a combination of NRTs.

In the EAGLES trial, all participants smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day, and had moderate dependence, with an average FTND score of 5 to 6.

2. What stage of change is the patient in, and how many times has he or she attempted to quit? Based on the answers, motivational interviewing may be appropriate.

Continue to: In the EAGLES trial...

In the EAGLES trial, the participants were motivated individuals who had on average 3 past quit attempts. Research suggests that even patients who have a serious mental illness can be motivated to quit (Box).6-9

Box

Mental illness and motivation to quit smoking

In the past, clinicians may have believed that many individuals with mental illness typically weren’t motivated to quit smoking. We now know this is not the case and that such patients’ motivation is similar to that of the general population, and the reasons driving their desire are the same—health concerns and social influences.6 Even individuals with serious mental illness such as schizophrenia who have a long history of tobacco use are highly motivated and persistent in their attempts to quit.7,8 The prevalence of future “readiness to quit” among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and depression ranges from 21% to 49%, which is similar to that among the general population (26% to 41%). Evidence also suggests that motivation translates into successful quitting, with quit rates of up to 22% for people with mental illness who use a combination of psychosocial and pharmacological interventions.9

3. What is the patient’s mental health status? What is the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis and how clinically stable is he or she? What is his or her suicide risk? Consider using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).10

In the EAGLES trial, the psychiatric cohort included only patients who had been clinically stable for the past 6 months and had received the same medication regimen for at least the past 3 months, with no expected changes for 12 weeks. Patients with certain diagnoses were excluded (eg, delusional disorder, schizophreniform disorder, impulse control disorders), and only 1% had a personality disorder, which increases mood lability and likelihood of suicidality behavior.

Continue to: Does the patient have another comorbid substance use disorder?

4. Does the patient have another comorbid substance use disorder? In the EAGLES trial, those who had active substance use in the past year or were receiving methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone were excluded.

5. Does the patient have any medical conditions? Does he or she have a history of seizures or eating disorders? It is important to determine if a patient has a seizure disorder or another medical condition that is a contraindication for using varenicline or bupropion.

I

6. Have you discussed smoking cessation and a treatment plan with the patient at every visit? In the EAGLES trial, participants received 10-minute cessation counseling at every outpatient visit.

Continue to: When it comes time to select a medication regimen...

When it comes time to select a medication regimen, for bupropion, consider starting the patient with 150 mg/d, and increasing the dose to 150 mg twice a day 4 days later. The target quit date should be 7 days after starting the medication. Monitor the patient for symptoms of anxiety and insomnia.

For varenicline, start the patient at 0.5 mg/d, and increase the dose to 0.5 mg twice a day 4 days later. After another 4 days, increase the dose to 1 mg twice a day. Set a target quit date for 7 days after starting medication. Monitor the patient for nausea, insomnia, and abnormal dreams.

Psychiatrists often fail to adequately address their patients’ smoking, and often underestimate the impact of ongoing tobacco use. Evidence suggests that heavy smoking is a risk factor for major depressive disorder; it also is associated with increased suicidal ideations and attempts.1,2 Tobacco use also has a mood-altering impact that can change the trajectory of mental illness, and alters the metabolism of most psychotropics.

Previously, psychiatrists may have been reluctant to prescribe the most effective interventions for smoking cessation—varenicline and bupropion—because these medications carried an FDA “black-box” warning of neuropsychiatric adverse effects, including increased aggression and suicidality. However,

The EAGLES trial was a large, multi-site global trial that included patients with and without mental illness. Its primary objective was to assess the risk of “clinically significant” adverse effects for individuals receiving varenicline, bupropion, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), or placebo, and whether having a history of psychiatric conditions increased the risk of developing adverse effects when taking these therapies. Overall, 2% of smokers without mental illness experienced adverse effects, compared with 5% to 7% in the psychiatric cohort, regardless of treatment arm. The rate of neuropsychiatric events and scores on suicide severity scales were similar across treatment arms in both cohorts.3

We should take lessons from the EAGLES trial. We propose that clinicians ask themselves the following 6 questions when forming a treatment plan to address their patients’ tobacco use:

1. Does the patient meet DSM-5 criteria for nicotine use disorder and, if yes, what is the severity of his or her nicotine dependence? The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)5 is a 6-question instrument for evaluating the quantity of cigarette consumption, compulsion to use, and dependence. It provides clinicians with guidelines on preventing withdrawal by implementing NRTs, such as lozenges, an inhaler, patches, and/or gum. A score of 1 to 2 (low dependence) indicates that no NRT is needed; a score of 3 to 4 (low to moderate dependence) requires 1 NRT; and scores of 5 to 7 (moderate dependence) and ≥8 (high dependence) require a combination of NRTs.

In the EAGLES trial, all participants smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day, and had moderate dependence, with an average FTND score of 5 to 6.

2. What stage of change is the patient in, and how many times has he or she attempted to quit? Based on the answers, motivational interviewing may be appropriate.

Continue to: In the EAGLES trial...

In the EAGLES trial, the participants were motivated individuals who had on average 3 past quit attempts. Research suggests that even patients who have a serious mental illness can be motivated to quit (Box).6-9

Box

Mental illness and motivation to quit smoking

In the past, clinicians may have believed that many individuals with mental illness typically weren’t motivated to quit smoking. We now know this is not the case and that such patients’ motivation is similar to that of the general population, and the reasons driving their desire are the same—health concerns and social influences.6 Even individuals with serious mental illness such as schizophrenia who have a long history of tobacco use are highly motivated and persistent in their attempts to quit.7,8 The prevalence of future “readiness to quit” among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and depression ranges from 21% to 49%, which is similar to that among the general population (26% to 41%). Evidence also suggests that motivation translates into successful quitting, with quit rates of up to 22% for people with mental illness who use a combination of psychosocial and pharmacological interventions.9

3. What is the patient’s mental health status? What is the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis and how clinically stable is he or she? What is his or her suicide risk? Consider using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).10

In the EAGLES trial, the psychiatric cohort included only patients who had been clinically stable for the past 6 months and had received the same medication regimen for at least the past 3 months, with no expected changes for 12 weeks. Patients with certain diagnoses were excluded (eg, delusional disorder, schizophreniform disorder, impulse control disorders), and only 1% had a personality disorder, which increases mood lability and likelihood of suicidality behavior.

Continue to: Does the patient have another comorbid substance use disorder?

4. Does the patient have another comorbid substance use disorder? In the EAGLES trial, those who had active substance use in the past year or were receiving methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone were excluded.

5. Does the patient have any medical conditions? Does he or she have a history of seizures or eating disorders? It is important to determine if a patient has a seizure disorder or another medical condition that is a contraindication for using varenicline or bupropion.

I

6. Have you discussed smoking cessation and a treatment plan with the patient at every visit? In the EAGLES trial, participants received 10-minute cessation counseling at every outpatient visit.

Continue to: When it comes time to select a medication regimen...

When it comes time to select a medication regimen, for bupropion, consider starting the patient with 150 mg/d, and increasing the dose to 150 mg twice a day 4 days later. The target quit date should be 7 days after starting the medication. Monitor the patient for symptoms of anxiety and insomnia.

For varenicline, start the patient at 0.5 mg/d, and increase the dose to 0.5 mg twice a day 4 days later. After another 4 days, increase the dose to 1 mg twice a day. Set a target quit date for 7 days after starting medication. Monitor the patient for nausea, insomnia, and abnormal dreams.

1. Khaled SM, Bulloch AG, Williams JV, et al. Persistent heavy smoking as risk factor for major depression (MD) incidence--evidence from a longitudinal Canadian cohort of the National Population Health Survey. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(4):436-443.

2. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C. Tobacco use and 12-month suicidality among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(1):39-48.

3. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520.

4. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises description of mental health side effects of the stop-smoking medicines Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion) to reflect clinical trial findings. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm532221.htm. Accessed April 16, 2018.

5. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The Fagerström Test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119-1127.

6. Moeller‐Saxone K. Cigarette smoking and interest in quitting among consumers at a psychiatric disability rehabilitation and support service in Victoria. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32(5):479-481.

7. Evins AE, Cather C, Rigotti NA, et al. Two-year follow-up of a smoking cessation trial in patients with schizophrenia: increased rates of smoking cessation and reduction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):307-311; quiz 452-453.

8. Weiner E, Ahmed S. Smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Cur Psychiatry Rev. 2013;9(2):164-172.

9. Banham L, Gilbody S. Smoking cessation in severe mental illness: what works? Addiction. 2010;105(7):1176-1189.

10. Posner K, Brent D, Lucas C, et al. Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). The Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, Inc. http://cssrs.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/C-SSRS_Pediatric-SLC_11.14.16.pdf. Updated June 23, 2010. Accessed April 26, 2018.

1. Khaled SM, Bulloch AG, Williams JV, et al. Persistent heavy smoking as risk factor for major depression (MD) incidence--evidence from a longitudinal Canadian cohort of the National Population Health Survey. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(4):436-443.

2. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C. Tobacco use and 12-month suicidality among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(1):39-48.

3. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520.

4. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises description of mental health side effects of the stop-smoking medicines Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion) to reflect clinical trial findings. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm532221.htm. Accessed April 16, 2018.

5. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The Fagerström Test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119-1127.

6. Moeller‐Saxone K. Cigarette smoking and interest in quitting among consumers at a psychiatric disability rehabilitation and support service in Victoria. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32(5):479-481.

7. Evins AE, Cather C, Rigotti NA, et al. Two-year follow-up of a smoking cessation trial in patients with schizophrenia: increased rates of smoking cessation and reduction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):307-311; quiz 452-453.

8. Weiner E, Ahmed S. Smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Cur Psychiatry Rev. 2013;9(2):164-172.

9. Banham L, Gilbody S. Smoking cessation in severe mental illness: what works? Addiction. 2010;105(7):1176-1189.

10. Posner K, Brent D, Lucas C, et al. Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). The Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, Inc. http://cssrs.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/C-SSRS_Pediatric-SLC_11.14.16.pdf. Updated June 23, 2010. Accessed April 26, 2018.

Bipolar disorder: How to avoid overdiagnosis

Over the past decade, bipolar disorder (BD) has gained widespread recognition in mainstream culture and in the media,1 and awareness of this condition has increased substantially. As a result, patients commonly present with preconceived ideas about bipolarity that may or may not actually correspond with this diagnosis. In anticipation of seeing such patients, I offer 4 recommendations to help clinicians more accurately diagnose BD.

1. Screen for periods of manic or hypomanic mood. Effective screening questions include:

- “Have you ever had periods when you felt too happy, too angry, or on top of the world for several days in a row?”

- “Have you had periods when you would go several days without much sleep and still feel fine during the day?”

If the patient reports irritability rather than euphoria, try to better understand the phenomenology of his or her irritable mood. Among patients who experience mania, irritability often results from impatience, which in turn seems to be secondary to grandiosity, increased energy, and accelerated thought processes.2

2. Avoid using terms with low specificity, such as “mood swings” and “racing thoughts,” when you screen for manic symptoms. If the patient mentions these phrases, do not take them at face value; ask him or her to characterize them in detail. Differentiate chronic, quick fluctuations in affect—which are usually triggered by environmental factors and typically are reported by patients with personality disorders—from more persistent periods of mood polarization. Similarly, anxious patients commonly report having “racing thoughts.”

3. Distinguish patients who have a chronic, ongoing preoccupation with shopping from those who exhibit intermittent periods of excessive shopping and prodigality, which usually are associated with other manic symptoms.3 Spending money in excess is often cited as a classic symptom of mania or hypomania, but it may be an indicator of other conditions, such as compulsive buying.

4. Ask about any increases in goal-directed activity. This is a good way to identify true manic or hypomanic periods. Patients with anxiety or agitated depression may report an increase in psychomotor activity, but this is usually characterized more by restlessness and wandering, and not by a true increase in activity.

Consider a temporary diagnosis

When in doubt, it may be advisable to establish a temporary diagnosis of unspecified mood disorder, until you can learn more about the patient, obtain collateral information from family or friends, and request past medical records.

1. Ghouse AA, Sanches M, Zunta-Soares G, et al. Overdiagnosis of bipolar disorder: a critical analysis of the literature. Scientific World Journal. 2013;2013:297087. doi: 10.1155/2013/297087.

2. Carlat DJ. My favorite tips for sorting out diagnostic quandaries with bipolar disorder and adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(2):233-238.

3. Black DW. A review of compulsive buying disorder. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(1):14-18.

Over the past decade, bipolar disorder (BD) has gained widespread recognition in mainstream culture and in the media,1 and awareness of this condition has increased substantially. As a result, patients commonly present with preconceived ideas about bipolarity that may or may not actually correspond with this diagnosis. In anticipation of seeing such patients, I offer 4 recommendations to help clinicians more accurately diagnose BD.

1. Screen for periods of manic or hypomanic mood. Effective screening questions include:

- “Have you ever had periods when you felt too happy, too angry, or on top of the world for several days in a row?”

- “Have you had periods when you would go several days without much sleep and still feel fine during the day?”

If the patient reports irritability rather than euphoria, try to better understand the phenomenology of his or her irritable mood. Among patients who experience mania, irritability often results from impatience, which in turn seems to be secondary to grandiosity, increased energy, and accelerated thought processes.2

2. Avoid using terms with low specificity, such as “mood swings” and “racing thoughts,” when you screen for manic symptoms. If the patient mentions these phrases, do not take them at face value; ask him or her to characterize them in detail. Differentiate chronic, quick fluctuations in affect—which are usually triggered by environmental factors and typically are reported by patients with personality disorders—from more persistent periods of mood polarization. Similarly, anxious patients commonly report having “racing thoughts.”

3. Distinguish patients who have a chronic, ongoing preoccupation with shopping from those who exhibit intermittent periods of excessive shopping and prodigality, which usually are associated with other manic symptoms.3 Spending money in excess is often cited as a classic symptom of mania or hypomania, but it may be an indicator of other conditions, such as compulsive buying.

4. Ask about any increases in goal-directed activity. This is a good way to identify true manic or hypomanic periods. Patients with anxiety or agitated depression may report an increase in psychomotor activity, but this is usually characterized more by restlessness and wandering, and not by a true increase in activity.

Consider a temporary diagnosis

When in doubt, it may be advisable to establish a temporary diagnosis of unspecified mood disorder, until you can learn more about the patient, obtain collateral information from family or friends, and request past medical records.

Over the past decade, bipolar disorder (BD) has gained widespread recognition in mainstream culture and in the media,1 and awareness of this condition has increased substantially. As a result, patients commonly present with preconceived ideas about bipolarity that may or may not actually correspond with this diagnosis. In anticipation of seeing such patients, I offer 4 recommendations to help clinicians more accurately diagnose BD.

1. Screen for periods of manic or hypomanic mood. Effective screening questions include:

- “Have you ever had periods when you felt too happy, too angry, or on top of the world for several days in a row?”

- “Have you had periods when you would go several days without much sleep and still feel fine during the day?”

If the patient reports irritability rather than euphoria, try to better understand the phenomenology of his or her irritable mood. Among patients who experience mania, irritability often results from impatience, which in turn seems to be secondary to grandiosity, increased energy, and accelerated thought processes.2

2. Avoid using terms with low specificity, such as “mood swings” and “racing thoughts,” when you screen for manic symptoms. If the patient mentions these phrases, do not take them at face value; ask him or her to characterize them in detail. Differentiate chronic, quick fluctuations in affect—which are usually triggered by environmental factors and typically are reported by patients with personality disorders—from more persistent periods of mood polarization. Similarly, anxious patients commonly report having “racing thoughts.”

3. Distinguish patients who have a chronic, ongoing preoccupation with shopping from those who exhibit intermittent periods of excessive shopping and prodigality, which usually are associated with other manic symptoms.3 Spending money in excess is often cited as a classic symptom of mania or hypomania, but it may be an indicator of other conditions, such as compulsive buying.

4. Ask about any increases in goal-directed activity. This is a good way to identify true manic or hypomanic periods. Patients with anxiety or agitated depression may report an increase in psychomotor activity, but this is usually characterized more by restlessness and wandering, and not by a true increase in activity.

Consider a temporary diagnosis

When in doubt, it may be advisable to establish a temporary diagnosis of unspecified mood disorder, until you can learn more about the patient, obtain collateral information from family or friends, and request past medical records.

1. Ghouse AA, Sanches M, Zunta-Soares G, et al. Overdiagnosis of bipolar disorder: a critical analysis of the literature. Scientific World Journal. 2013;2013:297087. doi: 10.1155/2013/297087.

2. Carlat DJ. My favorite tips for sorting out diagnostic quandaries with bipolar disorder and adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(2):233-238.

3. Black DW. A review of compulsive buying disorder. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(1):14-18.

1. Ghouse AA, Sanches M, Zunta-Soares G, et al. Overdiagnosis of bipolar disorder: a critical analysis of the literature. Scientific World Journal. 2013;2013:297087. doi: 10.1155/2013/297087.

2. Carlat DJ. My favorite tips for sorting out diagnostic quandaries with bipolar disorder and adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(2):233-238.

3. Black DW. A review of compulsive buying disorder. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(1):14-18.

Strategies for working with patients with personality disorders

Patients with personality disorders can disrupt the treatment relationship, and may leave us feeling angry, ineffective, inadequate, and defeated. Although their behaviors may appear volitional and purposeful, they often are the result of a dysfunctional personality structure.1 These patients’ unbending patterns of viewing themselves, interacting with others, and navigating the world can be problematic in an inpatient or outpatient setting, causing distress for both the staff and patient. Because no 2 personalities are identical, there is no algorithm for managing patients with personality disorders. However, there are strategies that we can apply to provide effective clinical care.1,2

Discuss the responses the patient evokes. Patients with personality disorders can elicit strong responses from the treatment team. Each clinician can have a different response to the same patient, ranging from feeling the need to protect the patient to strongly disliking him or her. Because cohesion among staff is essential for effective patient care, we need to discuss these responses in an open forum with our team members so we can effectively manage our responses and provide the patient with consistent interactions. Limiting the delivery of inconsistent or conflicting messages will decrease staff splitting and increase team unity.

Reinforce appropriate behaviors. Patients with personality disorders usually have negative interpersonal interactions, such as acting out, misinterpreting neutral social cues, and seeking constant attention. However, when they are not engaging in detrimental behaviors, we should provide positive reinforcement for appropriate behaviors, such as remaining composed, that help maintain the treatment relationship. When a patient displays disruptive behaviors, take a neutral approach by stating, “You appear upset. I will come back later when you are feeling better.”1

Set limits. These patients are likely to have difficulty conforming to appropriate social boundaries. Our reflex reaction may be to set concrete rules that fit our preferences. This could lead to a power struggle between us and our patients, which is not helpful. Rather than a “one-size-fits-all” approach to rules, it may be prudent to tailor boundaries according to each patient’s unique personality. Also, allowing the patient to help set these limits could increase the chances that he or she will follow your treatment plan and reinforce the more positive aspects of his or her personality structure.

Offer empathy. Empathy can be conceptualized as a step further than sympathy; in addition to expressing concern and compassion, empathy involves recognizing and sharing the patient’s emotions. Seek to comprehend the reasons behind a patient’s negative reactions by

1. Riddle M, Meeks T, Alvarez C, et al. When personality is the problem: managing patients with difficult personalitie s on the acute care unit. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):873-878.

2. Strous RD, Ulman AM, Kotler M. The hateful patient revisited: relevance for 21st century medicine. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17(6):387-393.

Patients with personality disorders can disrupt the treatment relationship, and may leave us feeling angry, ineffective, inadequate, and defeated. Although their behaviors may appear volitional and purposeful, they often are the result of a dysfunctional personality structure.1 These patients’ unbending patterns of viewing themselves, interacting with others, and navigating the world can be problematic in an inpatient or outpatient setting, causing distress for both the staff and patient. Because no 2 personalities are identical, there is no algorithm for managing patients with personality disorders. However, there are strategies that we can apply to provide effective clinical care.1,2

Discuss the responses the patient evokes. Patients with personality disorders can elicit strong responses from the treatment team. Each clinician can have a different response to the same patient, ranging from feeling the need to protect the patient to strongly disliking him or her. Because cohesion among staff is essential for effective patient care, we need to discuss these responses in an open forum with our team members so we can effectively manage our responses and provide the patient with consistent interactions. Limiting the delivery of inconsistent or conflicting messages will decrease staff splitting and increase team unity.

Reinforce appropriate behaviors. Patients with personality disorders usually have negative interpersonal interactions, such as acting out, misinterpreting neutral social cues, and seeking constant attention. However, when they are not engaging in detrimental behaviors, we should provide positive reinforcement for appropriate behaviors, such as remaining composed, that help maintain the treatment relationship. When a patient displays disruptive behaviors, take a neutral approach by stating, “You appear upset. I will come back later when you are feeling better.”1

Set limits. These patients are likely to have difficulty conforming to appropriate social boundaries. Our reflex reaction may be to set concrete rules that fit our preferences. This could lead to a power struggle between us and our patients, which is not helpful. Rather than a “one-size-fits-all” approach to rules, it may be prudent to tailor boundaries according to each patient’s unique personality. Also, allowing the patient to help set these limits could increase the chances that he or she will follow your treatment plan and reinforce the more positive aspects of his or her personality structure.

Offer empathy. Empathy can be conceptualized as a step further than sympathy; in addition to expressing concern and compassion, empathy involves recognizing and sharing the patient’s emotions. Seek to comprehend the reasons behind a patient’s negative reactions by

Patients with personality disorders can disrupt the treatment relationship, and may leave us feeling angry, ineffective, inadequate, and defeated. Although their behaviors may appear volitional and purposeful, they often are the result of a dysfunctional personality structure.1 These patients’ unbending patterns of viewing themselves, interacting with others, and navigating the world can be problematic in an inpatient or outpatient setting, causing distress for both the staff and patient. Because no 2 personalities are identical, there is no algorithm for managing patients with personality disorders. However, there are strategies that we can apply to provide effective clinical care.1,2

Discuss the responses the patient evokes. Patients with personality disorders can elicit strong responses from the treatment team. Each clinician can have a different response to the same patient, ranging from feeling the need to protect the patient to strongly disliking him or her. Because cohesion among staff is essential for effective patient care, we need to discuss these responses in an open forum with our team members so we can effectively manage our responses and provide the patient with consistent interactions. Limiting the delivery of inconsistent or conflicting messages will decrease staff splitting and increase team unity.

Reinforce appropriate behaviors. Patients with personality disorders usually have negative interpersonal interactions, such as acting out, misinterpreting neutral social cues, and seeking constant attention. However, when they are not engaging in detrimental behaviors, we should provide positive reinforcement for appropriate behaviors, such as remaining composed, that help maintain the treatment relationship. When a patient displays disruptive behaviors, take a neutral approach by stating, “You appear upset. I will come back later when you are feeling better.”1

Set limits. These patients are likely to have difficulty conforming to appropriate social boundaries. Our reflex reaction may be to set concrete rules that fit our preferences. This could lead to a power struggle between us and our patients, which is not helpful. Rather than a “one-size-fits-all” approach to rules, it may be prudent to tailor boundaries according to each patient’s unique personality. Also, allowing the patient to help set these limits could increase the chances that he or she will follow your treatment plan and reinforce the more positive aspects of his or her personality structure.

Offer empathy. Empathy can be conceptualized as a step further than sympathy; in addition to expressing concern and compassion, empathy involves recognizing and sharing the patient’s emotions. Seek to comprehend the reasons behind a patient’s negative reactions by

1. Riddle M, Meeks T, Alvarez C, et al. When personality is the problem: managing patients with difficult personalitie s on the acute care unit. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):873-878.

2. Strous RD, Ulman AM, Kotler M. The hateful patient revisited: relevance for 21st century medicine. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17(6):387-393.

1. Riddle M, Meeks T, Alvarez C, et al. When personality is the problem: managing patients with difficult personalitie s on the acute care unit. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):873-878.

2. Strous RD, Ulman AM, Kotler M. The hateful patient revisited: relevance for 21st century medicine. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17(6):387-393.

‘Nocebo’ effects: Address these 4 psychosocial factors

Sorting out the causes of unexplained adverse effects from psychotropic medications can be challenging. Treatment may be further complicated by ‘nocebo’ effects, which are adverse effects based on the patient’s conscious and unconscious expectations of harm. Having strategies for managing nocebo effects can help clinicians better understand and treat patients who have complex medication complaints. When your patient experiences nocebo effects, consider the following 4 psychosocial factors.1

Pills. The impact of a medication is not solely based on its chemical makeup. For example, the appearance of a medication can affect treatment outcomes. Substituting generic medications for branded ones has been shown to negatively impact patient adherence and increase reports of adverse effects that have no physiologic cause.2 Educating patients about medication manufacturing and distribution practices may decrease such consequences.

Patient. A sense of powerlessness is fertile ground for nocebo effects. Patients with an external locus of control may unconsciously employ nocebo effects to express themselves when other outlets are limited. Having a psychosocial formulation of your patient can help you anticipate pitfalls, offer pertinent insights, and mobilize the patient’s adaptive coping mechanisms. Also, clinicians can bolster their patients’ self-agency by encouraging them to participate in healthy activities.

Provider. Irrational factors in the clinician, such as countertransference, may also affect medication outcomes. Unprocessed countertransference can contribute to clinician burnout and impact the therapeutic relationship negatively. Nocebo effects may indicate that the clinician is not “tuned in” to the patient or is acting out harmful unconscious thoughts. Additionally, countertransference can lead to unnecessary prescribing and polypharmacy that confounds nocebo effects. Therefore self-care, consultation, and supervision may be vital in promoting therapeutic outcomes.

Partnership. The doctor–patient relationship can contribute to nocebo effects. A 2016 Gallup Poll found that Americans had low confidence in the honesty and ethics of psychiatrists compared with other healthcare professionals.3 It is important to have conversations with your patients about their reservations and perceived stigma of mental health. Such conversations can bring a patient’s ambivalence into treatment so that it can be further explored and addressed. Psychoeducation about treatment limitations, motivational interviewing techniques, and involving patients in decision-making can be useful tools for fostering a therapeutic alliance and positive outcomes.

Take an active approach

Evidence demonstrates that psychosocial factors significantly impact treatment outcomes.1 Incorporating this evidence into practice and attending to the 4 factors discussed here can enhance a clinician’s ability to flexibly respond to their patients’ complaints, especially in relation to nocebo effects.

1. Mallo CJ, Mintz DL. Teaching all the evidence bases: reintegrating psychodynamic aspects of prescribing into psychopharmacology training. Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2013;41(1):13-37.

2. Weissenfeld J, Stock S, Lüngen M, et al. The nocebo effect: a reason for patients’ non-adherence to generic substitution? Pharmazie. 2010;65(7):451-456.

3. Norman J. Americans rate healthcare providers high on honesty, ethics. Gallup. http://news.gallup.com/poll/200057/americans-rate-healthcare-providers-high-honesty-ethics.aspx. Published December 19, 2016. Accessed October 22, 2017.