User login

Employment contracts: What to check before you sign

Most psychiatrists are required to sign an employment contract before taking a job, but few of us have received any training on reviewing such contracts. We often rely on coworkers and attorneys to navigate this process for us. However, the contract is crucial, because it outlines your employer’s clinical and administrative expectations for the position, and it gives you the opportunity to lay out what you want.1 Because an employment contract is legally binding, you should thoroughly read it and look for clauses that may not work in your best interest. Although not a complete list, the following items should be reviewed before signing a contract.1,2

Benefits. Make sure you are offered a reasonable salary, but balance the dollar amount with benefits such as:

- continuing medical education allowances

- educational loan forgiveness

- health/malpractice/disability insurance

- retirement benefits

- compensation for call schedule.

In some cases, there may be a delay before you are eligible to obtain certain benefits.

Work expectations. Many contracts state that the position is “full-time” or have other nonspecific parameters for work expectations. You should inquire about objective work parameters, such as duty hours, the average frequency of the current call schedule, timeframe for completing medical documentation, and penalties for not meeting clinical or administrative requirements, so you are not surprised by:

- working longer-than-planned shifts

- performing on-call duties

- working on days that you were not expecting

- having your credentialing status placed in jeopardy.

Some group practices allow for a half-day of no scheduled appointments with patients, so you can complete paperwork and return phone calls.

Noncompete clause. This restricts you from working within a certain geographic area or for a competing employer for a finite time period after the contract terminates or expires. A noncompete clause could restrict you from practicing within a large geographical area, especially if the job is located in a densely populated area. Some noncompete clauses do not include a temporal or geographic restriction, but can limit your ability to bring patients with you to a new practice or facility when the contract expires.

Malpractice insurance. Two types of malpractice insurance are occurrence and claims-made:

- Occurrence insurance protects you whenever an action is brought against you, even if the action is brought after the contract terminates or expires.

- Claims-made insurance provides coverage if the policy with the same insurer was in effect when the malpractice was committed and when the actual action was commenced.

Although claims-made insurance is less expensive, it can leave you without coverage should you leave your employer and no longer maintain the same insurance policy. Claims-made can be converted into occurrence through the purchase of a tail endorsement. If the employer does not offer you tail coverage, then it is your responsibility to pay for this insurance, which can be expensive.

Termination language. Every contract features a termination section that lists potential causes for terminating your employment. This list is usually not exhaustive, but it sets the framework for a realistic view of reasonable causes. Contracts also commonly contain provisions that permit termination “without cause” after notice of termination is provided. Although you could negotiate for more notice time, “without cause” clauses are unlikely to be removed from the contract.

1. Claussen K. Eight physician employment contract items you need to know about. The Doctor Weighs In. https://thedoctorweighsin.com/8-physician-employment-contract-items-you-need-to-know-about. Published March 8, 2017. Accessed October 11, 2017.

2. Blustein AE, Keller LB. Physician employment contracts: what you need to know before you sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. https://www.aad.org/members/publications/directions-in-residency/archiveyment-contracts-what-you-need-to-know-before-you-sign. Accessed October 11, 2017.

Most psychiatrists are required to sign an employment contract before taking a job, but few of us have received any training on reviewing such contracts. We often rely on coworkers and attorneys to navigate this process for us. However, the contract is crucial, because it outlines your employer’s clinical and administrative expectations for the position, and it gives you the opportunity to lay out what you want.1 Because an employment contract is legally binding, you should thoroughly read it and look for clauses that may not work in your best interest. Although not a complete list, the following items should be reviewed before signing a contract.1,2

Benefits. Make sure you are offered a reasonable salary, but balance the dollar amount with benefits such as:

- continuing medical education allowances

- educational loan forgiveness

- health/malpractice/disability insurance

- retirement benefits

- compensation for call schedule.

In some cases, there may be a delay before you are eligible to obtain certain benefits.

Work expectations. Many contracts state that the position is “full-time” or have other nonspecific parameters for work expectations. You should inquire about objective work parameters, such as duty hours, the average frequency of the current call schedule, timeframe for completing medical documentation, and penalties for not meeting clinical or administrative requirements, so you are not surprised by:

- working longer-than-planned shifts

- performing on-call duties

- working on days that you were not expecting

- having your credentialing status placed in jeopardy.

Some group practices allow for a half-day of no scheduled appointments with patients, so you can complete paperwork and return phone calls.

Noncompete clause. This restricts you from working within a certain geographic area or for a competing employer for a finite time period after the contract terminates or expires. A noncompete clause could restrict you from practicing within a large geographical area, especially if the job is located in a densely populated area. Some noncompete clauses do not include a temporal or geographic restriction, but can limit your ability to bring patients with you to a new practice or facility when the contract expires.

Malpractice insurance. Two types of malpractice insurance are occurrence and claims-made:

- Occurrence insurance protects you whenever an action is brought against you, even if the action is brought after the contract terminates or expires.

- Claims-made insurance provides coverage if the policy with the same insurer was in effect when the malpractice was committed and when the actual action was commenced.

Although claims-made insurance is less expensive, it can leave you without coverage should you leave your employer and no longer maintain the same insurance policy. Claims-made can be converted into occurrence through the purchase of a tail endorsement. If the employer does not offer you tail coverage, then it is your responsibility to pay for this insurance, which can be expensive.

Termination language. Every contract features a termination section that lists potential causes for terminating your employment. This list is usually not exhaustive, but it sets the framework for a realistic view of reasonable causes. Contracts also commonly contain provisions that permit termination “without cause” after notice of termination is provided. Although you could negotiate for more notice time, “without cause” clauses are unlikely to be removed from the contract.

Most psychiatrists are required to sign an employment contract before taking a job, but few of us have received any training on reviewing such contracts. We often rely on coworkers and attorneys to navigate this process for us. However, the contract is crucial, because it outlines your employer’s clinical and administrative expectations for the position, and it gives you the opportunity to lay out what you want.1 Because an employment contract is legally binding, you should thoroughly read it and look for clauses that may not work in your best interest. Although not a complete list, the following items should be reviewed before signing a contract.1,2

Benefits. Make sure you are offered a reasonable salary, but balance the dollar amount with benefits such as:

- continuing medical education allowances

- educational loan forgiveness

- health/malpractice/disability insurance

- retirement benefits

- compensation for call schedule.

In some cases, there may be a delay before you are eligible to obtain certain benefits.

Work expectations. Many contracts state that the position is “full-time” or have other nonspecific parameters for work expectations. You should inquire about objective work parameters, such as duty hours, the average frequency of the current call schedule, timeframe for completing medical documentation, and penalties for not meeting clinical or administrative requirements, so you are not surprised by:

- working longer-than-planned shifts

- performing on-call duties

- working on days that you were not expecting

- having your credentialing status placed in jeopardy.

Some group practices allow for a half-day of no scheduled appointments with patients, so you can complete paperwork and return phone calls.

Noncompete clause. This restricts you from working within a certain geographic area or for a competing employer for a finite time period after the contract terminates or expires. A noncompete clause could restrict you from practicing within a large geographical area, especially if the job is located in a densely populated area. Some noncompete clauses do not include a temporal or geographic restriction, but can limit your ability to bring patients with you to a new practice or facility when the contract expires.

Malpractice insurance. Two types of malpractice insurance are occurrence and claims-made:

- Occurrence insurance protects you whenever an action is brought against you, even if the action is brought after the contract terminates or expires.

- Claims-made insurance provides coverage if the policy with the same insurer was in effect when the malpractice was committed and when the actual action was commenced.

Although claims-made insurance is less expensive, it can leave you without coverage should you leave your employer and no longer maintain the same insurance policy. Claims-made can be converted into occurrence through the purchase of a tail endorsement. If the employer does not offer you tail coverage, then it is your responsibility to pay for this insurance, which can be expensive.

Termination language. Every contract features a termination section that lists potential causes for terminating your employment. This list is usually not exhaustive, but it sets the framework for a realistic view of reasonable causes. Contracts also commonly contain provisions that permit termination “without cause” after notice of termination is provided. Although you could negotiate for more notice time, “without cause” clauses are unlikely to be removed from the contract.

1. Claussen K. Eight physician employment contract items you need to know about. The Doctor Weighs In. https://thedoctorweighsin.com/8-physician-employment-contract-items-you-need-to-know-about. Published March 8, 2017. Accessed October 11, 2017.

2. Blustein AE, Keller LB. Physician employment contracts: what you need to know before you sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. https://www.aad.org/members/publications/directions-in-residency/archiveyment-contracts-what-you-need-to-know-before-you-sign. Accessed October 11, 2017.

1. Claussen K. Eight physician employment contract items you need to know about. The Doctor Weighs In. https://thedoctorweighsin.com/8-physician-employment-contract-items-you-need-to-know-about. Published March 8, 2017. Accessed October 11, 2017.

2. Blustein AE, Keller LB. Physician employment contracts: what you need to know before you sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. https://www.aad.org/members/publications/directions-in-residency/archiveyment-contracts-what-you-need-to-know-before-you-sign. Accessed October 11, 2017.

Self-disclosure as therapy: The benefits of expressive writing

As psychiatrists, we often provide our patients with a prescription in the hope that the medication will alleviate their symptoms. Perhaps we engage our patients in psychotherapy, encouraging them to reflect on their thoughts, behaviors, and emotions to alter their cognitions. We may remark that our goal is for the patient to “become their own therapist.” What if we encouraged our patients to express themselves in a less structured manner and become their own therapists through writing?

Benefits of expressive writing

Writing about an experienced traumatic event—specifically, to express emotions related to the event—has been associated with improved health outcomes.1,2 Many of these improvements are related to somatic health and basic function, including decreased use of health services, improved immune functioning, and a boost in grades or occupational performance.1 Patients who participate in expressive writing also have demonstrated improvements in distress, negative affect, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.1,2 Although improvement in PTSD symptoms with expressive writing has varied across studies, it appears that patients with PTSD who score high in trait negative emotion may receive the most benefit from the practice.3

Why does it work?

There are several theories regarding why expressive writing is an effective therapy. Originally, it was believed that the active inhibition of not talking about traumatic events was a form of physiological work and a long-term, low-lying stressor, and that writing about such events could reduce this stress. However, newer studies offer various explanations for its efficacy, including:

- repeat exposure to stressful or traumatic memories and consequent self-distancing

- creation of a narrative around the stressful event

- labeling of emotions

- self-affirmation and meaning-making related to the negative event.4

Rx writing

Encouraging your patients to use expressive writing is simple. You might ask a patient struggling with distress and negative affect following a traumatic experience to write about his (her) thoughts and feelings regarding the incident. For example:

Spend about 15 minutes writing your deepest thoughts and feelings about going through this traumatic experience. Discuss the ways it affected different areas of your life, including relationships with family and friends, school or work, or self-confidence and self-esteem. Don’t worry about spelling, grammar, or sentence structure.

Assure patients that you do not need to review their writing, but would like to hear about their experience writing. Many studies on expressive writing instructed participants to write for 3 to 5 consecutive days, 15 to 30 minutes each day.1,2 Patients may disclose a dramatic spectrum and intensity of experience and often are willing to do so.

Expressive writing is a simple, low-risk exercise that benefits many people. Perhaps by prescribing a course of writing, you will find your patients can benefit as well.

1. Baikie KA, Geerligs L, Wilhelm K. Expressive writing and positive writing for participants with mood disorders: an online randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):310-319.

2. Krpan KM, Kross E, Berman MG, et al. An everyday activity as a treatment for depression: the benefits of expressive writing for people diagnosed with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):1148-1151.

3. Hoyt T, Yeater EA. The effects of negative emotion and expressive writing on posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2011;30:549-569.

4. Niles AN, Byrne Haltom KE, Lieberman MD, et al. Writing content predicts benefit from written expressive disclosure: evidence for repeated exposure and self-affirmation. Cogn Emot. 2016;30(2):258-274.

As psychiatrists, we often provide our patients with a prescription in the hope that the medication will alleviate their symptoms. Perhaps we engage our patients in psychotherapy, encouraging them to reflect on their thoughts, behaviors, and emotions to alter their cognitions. We may remark that our goal is for the patient to “become their own therapist.” What if we encouraged our patients to express themselves in a less structured manner and become their own therapists through writing?

Benefits of expressive writing

Writing about an experienced traumatic event—specifically, to express emotions related to the event—has been associated with improved health outcomes.1,2 Many of these improvements are related to somatic health and basic function, including decreased use of health services, improved immune functioning, and a boost in grades or occupational performance.1 Patients who participate in expressive writing also have demonstrated improvements in distress, negative affect, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.1,2 Although improvement in PTSD symptoms with expressive writing has varied across studies, it appears that patients with PTSD who score high in trait negative emotion may receive the most benefit from the practice.3

Why does it work?

There are several theories regarding why expressive writing is an effective therapy. Originally, it was believed that the active inhibition of not talking about traumatic events was a form of physiological work and a long-term, low-lying stressor, and that writing about such events could reduce this stress. However, newer studies offer various explanations for its efficacy, including:

- repeat exposure to stressful or traumatic memories and consequent self-distancing

- creation of a narrative around the stressful event

- labeling of emotions

- self-affirmation and meaning-making related to the negative event.4

Rx writing

Encouraging your patients to use expressive writing is simple. You might ask a patient struggling with distress and negative affect following a traumatic experience to write about his (her) thoughts and feelings regarding the incident. For example:

Spend about 15 minutes writing your deepest thoughts and feelings about going through this traumatic experience. Discuss the ways it affected different areas of your life, including relationships with family and friends, school or work, or self-confidence and self-esteem. Don’t worry about spelling, grammar, or sentence structure.

Assure patients that you do not need to review their writing, but would like to hear about their experience writing. Many studies on expressive writing instructed participants to write for 3 to 5 consecutive days, 15 to 30 minutes each day.1,2 Patients may disclose a dramatic spectrum and intensity of experience and often are willing to do so.

Expressive writing is a simple, low-risk exercise that benefits many people. Perhaps by prescribing a course of writing, you will find your patients can benefit as well.

As psychiatrists, we often provide our patients with a prescription in the hope that the medication will alleviate their symptoms. Perhaps we engage our patients in psychotherapy, encouraging them to reflect on their thoughts, behaviors, and emotions to alter their cognitions. We may remark that our goal is for the patient to “become their own therapist.” What if we encouraged our patients to express themselves in a less structured manner and become their own therapists through writing?

Benefits of expressive writing

Writing about an experienced traumatic event—specifically, to express emotions related to the event—has been associated with improved health outcomes.1,2 Many of these improvements are related to somatic health and basic function, including decreased use of health services, improved immune functioning, and a boost in grades or occupational performance.1 Patients who participate in expressive writing also have demonstrated improvements in distress, negative affect, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.1,2 Although improvement in PTSD symptoms with expressive writing has varied across studies, it appears that patients with PTSD who score high in trait negative emotion may receive the most benefit from the practice.3

Why does it work?

There are several theories regarding why expressive writing is an effective therapy. Originally, it was believed that the active inhibition of not talking about traumatic events was a form of physiological work and a long-term, low-lying stressor, and that writing about such events could reduce this stress. However, newer studies offer various explanations for its efficacy, including:

- repeat exposure to stressful or traumatic memories and consequent self-distancing

- creation of a narrative around the stressful event

- labeling of emotions

- self-affirmation and meaning-making related to the negative event.4

Rx writing

Encouraging your patients to use expressive writing is simple. You might ask a patient struggling with distress and negative affect following a traumatic experience to write about his (her) thoughts and feelings regarding the incident. For example:

Spend about 15 minutes writing your deepest thoughts and feelings about going through this traumatic experience. Discuss the ways it affected different areas of your life, including relationships with family and friends, school or work, or self-confidence and self-esteem. Don’t worry about spelling, grammar, or sentence structure.

Assure patients that you do not need to review their writing, but would like to hear about their experience writing. Many studies on expressive writing instructed participants to write for 3 to 5 consecutive days, 15 to 30 minutes each day.1,2 Patients may disclose a dramatic spectrum and intensity of experience and often are willing to do so.

Expressive writing is a simple, low-risk exercise that benefits many people. Perhaps by prescribing a course of writing, you will find your patients can benefit as well.

1. Baikie KA, Geerligs L, Wilhelm K. Expressive writing and positive writing for participants with mood disorders: an online randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):310-319.

2. Krpan KM, Kross E, Berman MG, et al. An everyday activity as a treatment for depression: the benefits of expressive writing for people diagnosed with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):1148-1151.

3. Hoyt T, Yeater EA. The effects of negative emotion and expressive writing on posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2011;30:549-569.

4. Niles AN, Byrne Haltom KE, Lieberman MD, et al. Writing content predicts benefit from written expressive disclosure: evidence for repeated exposure and self-affirmation. Cogn Emot. 2016;30(2):258-274.

1. Baikie KA, Geerligs L, Wilhelm K. Expressive writing and positive writing for participants with mood disorders: an online randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):310-319.

2. Krpan KM, Kross E, Berman MG, et al. An everyday activity as a treatment for depression: the benefits of expressive writing for people diagnosed with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):1148-1151.

3. Hoyt T, Yeater EA. The effects of negative emotion and expressive writing on posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2011;30:549-569.

4. Niles AN, Byrne Haltom KE, Lieberman MD, et al. Writing content predicts benefit from written expressive disclosure: evidence for repeated exposure and self-affirmation. Cogn Emot. 2016;30(2):258-274.

Managing requests for gluten-, lactose-, and animal-free medications

Patients may ask their psychiatrist to prescribe gluten-, lactose-, or animal-free medications because of concerns about allergies, disease states, religious beliefs, or dietary preferences. Determining the source of non-active medication ingredients can be challenging and time-consuming, because ingredients vary across dosages and formulations of the same medication. We review how to address requests for gluten-, lactose-, and animal-free medications.

Gluten-free

Although the risk of a medication containing gluten is low,1 patients with Celiac disease must avoid gluten to prevent disease exacerbation. Therefore, physicians should thoroughly evaluate medication ingredients to prevent inadvertent gluten consumption.

Medication excipients that may contain gluten include:

- starch

- pregelatinized starch

- sodium starch glycolate.1

These starches can come from various sources, including corn, wheat, potato, and tapioca. Wheat-derived starch contains gluten and should be avoided by patients with Celiac disease. Advise patients to avoid any starch if its source cannot be determined.

Some sources may list sugar alcohols, such as mannitol and xylitol, as gluten–containing excipients because they may be extracted from starch sources, such as wheat; however, all gluten is removed during refinement and these products are safe.2

Lactose-free

How to respond to a patient’s request for lactose-free medication depends on whether the patient is lactose intolerant or has a milk allergy. The amount of lactose that patients with lactase deficiency can tolerate varies.3 Most medications are thought to contain minimal amounts of lactose. Case reports have described patients experiencing lactose intolerance symptoms after taking 1 or 2 medications, but this is rare.3 Therefore, it is reasonable to use lactose–containing products in patients with lactose intolerance. If such a patient develops symptoms after taking a medication that contains lactose, suggest that he (she):

- take the medication with food, if appropriate, to slow absorption and reduce symptoms

- take it with a lactase enzyme product

- substitute it with a medication that does not contain lactose (switch to a different product or formulation, as appropriate).

Compared with patients who are lactose intolerant, those with a milk allergy experience an immunoglobulin E–mediated reaction when they consume milk protein. Milk proteins typically are filtered out during manufacturing, but a small amount can remain. Although it has not been determined if oral medications containing milk protein can cause an allergic reaction, some researchers have hypothesized that these medications may be tolerated because acid and digestive enzymes break down the milk protein. However, because the respiratory tract lacks this protection, inhaled products that contain lactose may be more likely to cause an allergic reaction and should be avoided if possible. Because oral medications do not usually contain milk proteins, it may be reasonable to prescribe lactose–containing oral products to a patient with a milk allergy. If the patient experiences a reaction or wishes to avoid lactose, an alternative non-lactose–containing product or formulation may be prescribed.

Animal-free

Individuals who are members of certain religions, including Judaism, Islam, Orthodox Christianity, and the Seventh Day Adventist Church, typically avoid pork, and those who are Hindu or Buddhist may avoid beef products.4 Gelatin and stearic acid, which can be found in the gelatin shell of capsules and within extended-release (ER) tablets, frequently are derived from porcine or bovine sources. The source of gelatin and stearic acid may change from lot to lot, and manufacturers should be contacted to assist with identifying the source for a specific medication. Consider these options to reduce a patient’s exposure to animal-containing products:

- change from an ER to an immediate-release (IR) product (confirm that IR is gelatin- and stearic acid–free)

- use a non-capsule formulation

- remove the content of a capsule before ingestion, if appropriate

- try an alternative route of administration, such as transdermal.

How to best help patients

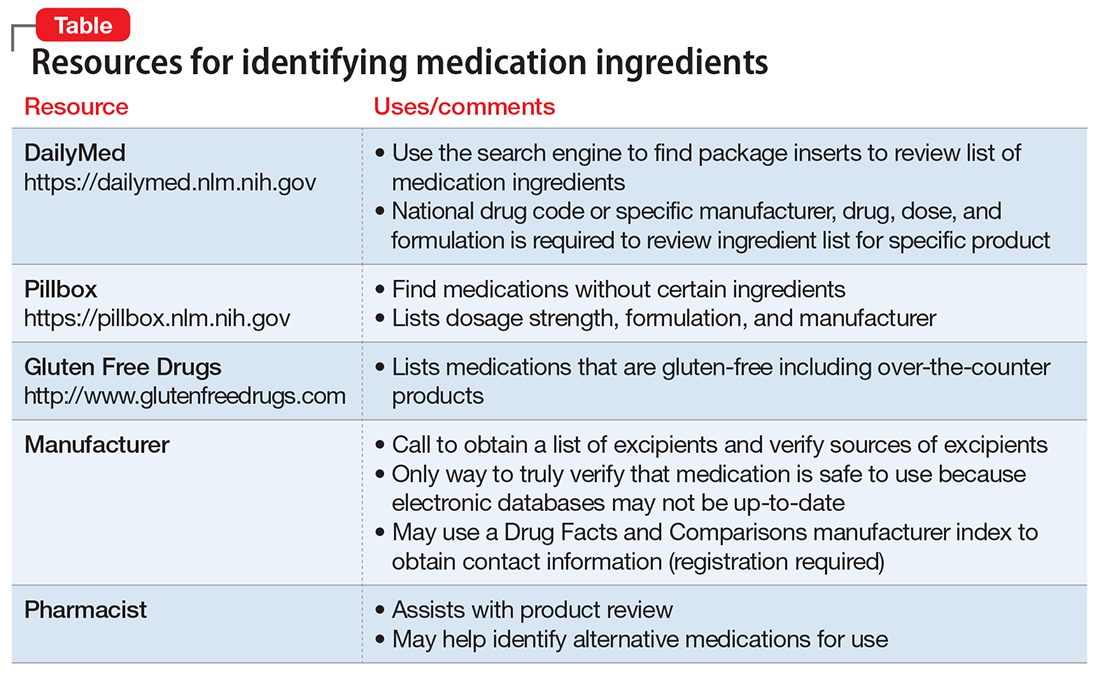

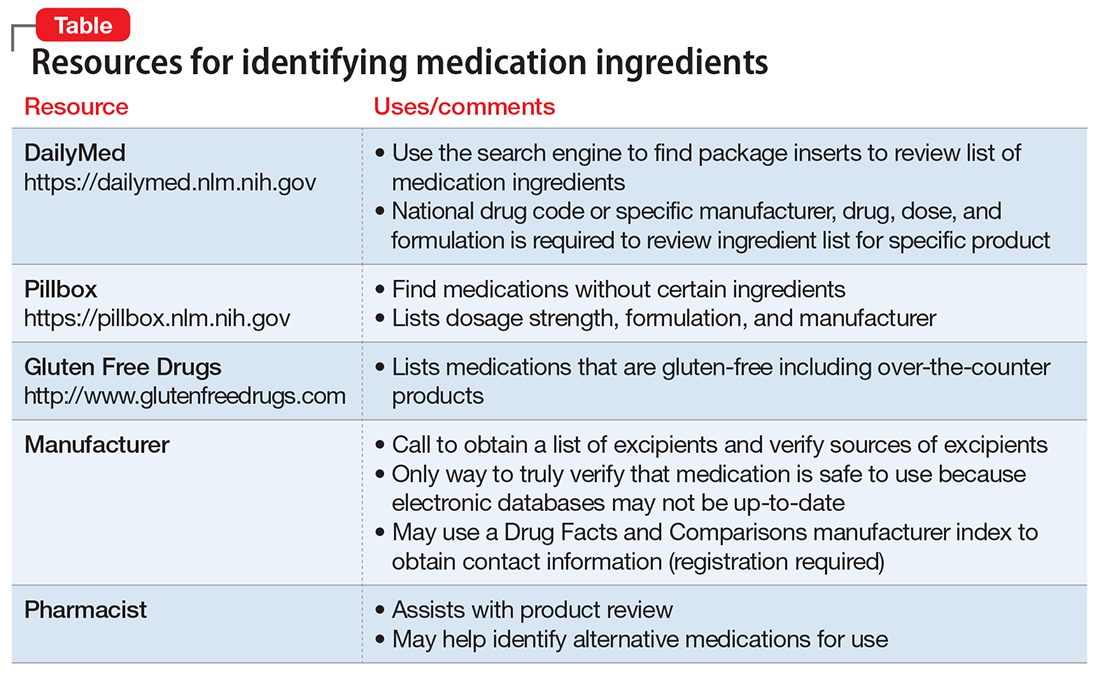

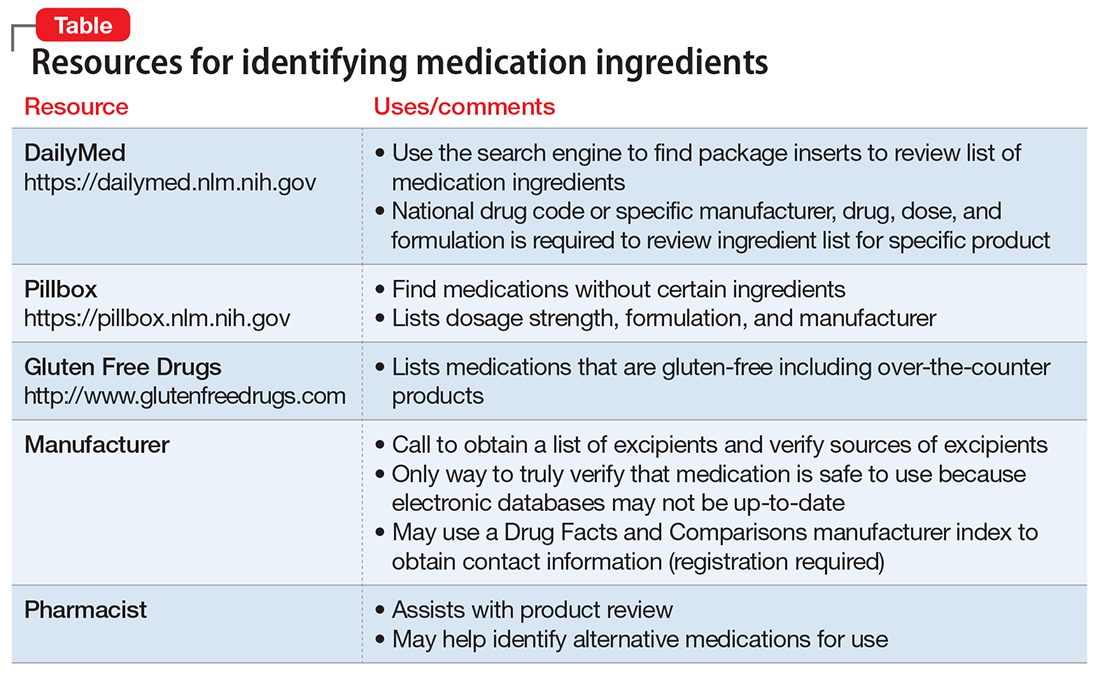

Before taking steps to accommodate a request for a gluten-, lactose-, or animal-free medication, which can be time-consuming, verify the reason for your patient’s request. It may be sufficient to explain to your patient that typically exposure to excipients within oral medications is small and does not cause problems for a patient with lactose intolerance or a milk allergy. The resources listed in the Table can help provide further education on these concerns; however, due to potential delays in updating a Web site, it may be necessary to contact the medication manufacturer directly to verify ingredients.

If your patient still has concerns about ingredients, consider the following steps:

- Use the National Library of Medicine’s Pillbox Web site (https://pillbox.nlm.nih.gov) to search for a medication, dose, or formulation that does not contain the concerning ingredients

- If the concerning ingredient is not listed, either prescribe the medication or contact the manufacturer for further information, depending on the patient’s reason for the request

- If the concerning ingredient is listed, work with the pharmacist to contact the manufacturer.

There are 2 additional points to consider regarding medication excipients. Be aware that generic medications are produced by multiple manufacturers, and each may use different excipients. Also, a manufacturer may not guarantee that a medication is gluten-free because of the potential for cross-contamination during manufacturing, although the risk is extremely low.

1. Plogsted S. Gluten in medication. Celiac Disease Foundation. https://celiac.org/live-gluten-free/glutenfreediet/gluten-medication. Accessed January 13, 2017.

2. Plogsted S. Gluten free drugs. http://www.glutenfreedrugs.com. Updated April 28, 2017. Accessed September 2, 2017.

3. Lactose in medications. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter. 2007;230779.

4. Sattar SP, Shakeel Ahmed M, Majeed F, et al. Inert medication ingredients causing nonadherence due to religious beliefs. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(4):621-624.

Patients may ask their psychiatrist to prescribe gluten-, lactose-, or animal-free medications because of concerns about allergies, disease states, religious beliefs, or dietary preferences. Determining the source of non-active medication ingredients can be challenging and time-consuming, because ingredients vary across dosages and formulations of the same medication. We review how to address requests for gluten-, lactose-, and animal-free medications.

Gluten-free

Although the risk of a medication containing gluten is low,1 patients with Celiac disease must avoid gluten to prevent disease exacerbation. Therefore, physicians should thoroughly evaluate medication ingredients to prevent inadvertent gluten consumption.

Medication excipients that may contain gluten include:

- starch

- pregelatinized starch

- sodium starch glycolate.1

These starches can come from various sources, including corn, wheat, potato, and tapioca. Wheat-derived starch contains gluten and should be avoided by patients with Celiac disease. Advise patients to avoid any starch if its source cannot be determined.

Some sources may list sugar alcohols, such as mannitol and xylitol, as gluten–containing excipients because they may be extracted from starch sources, such as wheat; however, all gluten is removed during refinement and these products are safe.2

Lactose-free

How to respond to a patient’s request for lactose-free medication depends on whether the patient is lactose intolerant or has a milk allergy. The amount of lactose that patients with lactase deficiency can tolerate varies.3 Most medications are thought to contain minimal amounts of lactose. Case reports have described patients experiencing lactose intolerance symptoms after taking 1 or 2 medications, but this is rare.3 Therefore, it is reasonable to use lactose–containing products in patients with lactose intolerance. If such a patient develops symptoms after taking a medication that contains lactose, suggest that he (she):

- take the medication with food, if appropriate, to slow absorption and reduce symptoms

- take it with a lactase enzyme product

- substitute it with a medication that does not contain lactose (switch to a different product or formulation, as appropriate).

Compared with patients who are lactose intolerant, those with a milk allergy experience an immunoglobulin E–mediated reaction when they consume milk protein. Milk proteins typically are filtered out during manufacturing, but a small amount can remain. Although it has not been determined if oral medications containing milk protein can cause an allergic reaction, some researchers have hypothesized that these medications may be tolerated because acid and digestive enzymes break down the milk protein. However, because the respiratory tract lacks this protection, inhaled products that contain lactose may be more likely to cause an allergic reaction and should be avoided if possible. Because oral medications do not usually contain milk proteins, it may be reasonable to prescribe lactose–containing oral products to a patient with a milk allergy. If the patient experiences a reaction or wishes to avoid lactose, an alternative non-lactose–containing product or formulation may be prescribed.

Animal-free

Individuals who are members of certain religions, including Judaism, Islam, Orthodox Christianity, and the Seventh Day Adventist Church, typically avoid pork, and those who are Hindu or Buddhist may avoid beef products.4 Gelatin and stearic acid, which can be found in the gelatin shell of capsules and within extended-release (ER) tablets, frequently are derived from porcine or bovine sources. The source of gelatin and stearic acid may change from lot to lot, and manufacturers should be contacted to assist with identifying the source for a specific medication. Consider these options to reduce a patient’s exposure to animal-containing products:

- change from an ER to an immediate-release (IR) product (confirm that IR is gelatin- and stearic acid–free)

- use a non-capsule formulation

- remove the content of a capsule before ingestion, if appropriate

- try an alternative route of administration, such as transdermal.

How to best help patients

Before taking steps to accommodate a request for a gluten-, lactose-, or animal-free medication, which can be time-consuming, verify the reason for your patient’s request. It may be sufficient to explain to your patient that typically exposure to excipients within oral medications is small and does not cause problems for a patient with lactose intolerance or a milk allergy. The resources listed in the Table can help provide further education on these concerns; however, due to potential delays in updating a Web site, it may be necessary to contact the medication manufacturer directly to verify ingredients.

If your patient still has concerns about ingredients, consider the following steps:

- Use the National Library of Medicine’s Pillbox Web site (https://pillbox.nlm.nih.gov) to search for a medication, dose, or formulation that does not contain the concerning ingredients

- If the concerning ingredient is not listed, either prescribe the medication or contact the manufacturer for further information, depending on the patient’s reason for the request

- If the concerning ingredient is listed, work with the pharmacist to contact the manufacturer.

There are 2 additional points to consider regarding medication excipients. Be aware that generic medications are produced by multiple manufacturers, and each may use different excipients. Also, a manufacturer may not guarantee that a medication is gluten-free because of the potential for cross-contamination during manufacturing, although the risk is extremely low.

Patients may ask their psychiatrist to prescribe gluten-, lactose-, or animal-free medications because of concerns about allergies, disease states, religious beliefs, or dietary preferences. Determining the source of non-active medication ingredients can be challenging and time-consuming, because ingredients vary across dosages and formulations of the same medication. We review how to address requests for gluten-, lactose-, and animal-free medications.

Gluten-free

Although the risk of a medication containing gluten is low,1 patients with Celiac disease must avoid gluten to prevent disease exacerbation. Therefore, physicians should thoroughly evaluate medication ingredients to prevent inadvertent gluten consumption.

Medication excipients that may contain gluten include:

- starch

- pregelatinized starch

- sodium starch glycolate.1

These starches can come from various sources, including corn, wheat, potato, and tapioca. Wheat-derived starch contains gluten and should be avoided by patients with Celiac disease. Advise patients to avoid any starch if its source cannot be determined.

Some sources may list sugar alcohols, such as mannitol and xylitol, as gluten–containing excipients because they may be extracted from starch sources, such as wheat; however, all gluten is removed during refinement and these products are safe.2

Lactose-free

How to respond to a patient’s request for lactose-free medication depends on whether the patient is lactose intolerant or has a milk allergy. The amount of lactose that patients with lactase deficiency can tolerate varies.3 Most medications are thought to contain minimal amounts of lactose. Case reports have described patients experiencing lactose intolerance symptoms after taking 1 or 2 medications, but this is rare.3 Therefore, it is reasonable to use lactose–containing products in patients with lactose intolerance. If such a patient develops symptoms after taking a medication that contains lactose, suggest that he (she):

- take the medication with food, if appropriate, to slow absorption and reduce symptoms

- take it with a lactase enzyme product

- substitute it with a medication that does not contain lactose (switch to a different product or formulation, as appropriate).

Compared with patients who are lactose intolerant, those with a milk allergy experience an immunoglobulin E–mediated reaction when they consume milk protein. Milk proteins typically are filtered out during manufacturing, but a small amount can remain. Although it has not been determined if oral medications containing milk protein can cause an allergic reaction, some researchers have hypothesized that these medications may be tolerated because acid and digestive enzymes break down the milk protein. However, because the respiratory tract lacks this protection, inhaled products that contain lactose may be more likely to cause an allergic reaction and should be avoided if possible. Because oral medications do not usually contain milk proteins, it may be reasonable to prescribe lactose–containing oral products to a patient with a milk allergy. If the patient experiences a reaction or wishes to avoid lactose, an alternative non-lactose–containing product or formulation may be prescribed.

Animal-free

Individuals who are members of certain religions, including Judaism, Islam, Orthodox Christianity, and the Seventh Day Adventist Church, typically avoid pork, and those who are Hindu or Buddhist may avoid beef products.4 Gelatin and stearic acid, which can be found in the gelatin shell of capsules and within extended-release (ER) tablets, frequently are derived from porcine or bovine sources. The source of gelatin and stearic acid may change from lot to lot, and manufacturers should be contacted to assist with identifying the source for a specific medication. Consider these options to reduce a patient’s exposure to animal-containing products:

- change from an ER to an immediate-release (IR) product (confirm that IR is gelatin- and stearic acid–free)

- use a non-capsule formulation

- remove the content of a capsule before ingestion, if appropriate

- try an alternative route of administration, such as transdermal.

How to best help patients

Before taking steps to accommodate a request for a gluten-, lactose-, or animal-free medication, which can be time-consuming, verify the reason for your patient’s request. It may be sufficient to explain to your patient that typically exposure to excipients within oral medications is small and does not cause problems for a patient with lactose intolerance or a milk allergy. The resources listed in the Table can help provide further education on these concerns; however, due to potential delays in updating a Web site, it may be necessary to contact the medication manufacturer directly to verify ingredients.

If your patient still has concerns about ingredients, consider the following steps:

- Use the National Library of Medicine’s Pillbox Web site (https://pillbox.nlm.nih.gov) to search for a medication, dose, or formulation that does not contain the concerning ingredients

- If the concerning ingredient is not listed, either prescribe the medication or contact the manufacturer for further information, depending on the patient’s reason for the request

- If the concerning ingredient is listed, work with the pharmacist to contact the manufacturer.

There are 2 additional points to consider regarding medication excipients. Be aware that generic medications are produced by multiple manufacturers, and each may use different excipients. Also, a manufacturer may not guarantee that a medication is gluten-free because of the potential for cross-contamination during manufacturing, although the risk is extremely low.

1. Plogsted S. Gluten in medication. Celiac Disease Foundation. https://celiac.org/live-gluten-free/glutenfreediet/gluten-medication. Accessed January 13, 2017.

2. Plogsted S. Gluten free drugs. http://www.glutenfreedrugs.com. Updated April 28, 2017. Accessed September 2, 2017.

3. Lactose in medications. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter. 2007;230779.

4. Sattar SP, Shakeel Ahmed M, Majeed F, et al. Inert medication ingredients causing nonadherence due to religious beliefs. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(4):621-624.

1. Plogsted S. Gluten in medication. Celiac Disease Foundation. https://celiac.org/live-gluten-free/glutenfreediet/gluten-medication. Accessed January 13, 2017.

2. Plogsted S. Gluten free drugs. http://www.glutenfreedrugs.com. Updated April 28, 2017. Accessed September 2, 2017.

3. Lactose in medications. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter. 2007;230779.

4. Sattar SP, Shakeel Ahmed M, Majeed F, et al. Inert medication ingredients causing nonadherence due to religious beliefs. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(4):621-624.

What to do after a patient assaults you

Physical assaults by patients are an occupational hazard of practicing medicine. Assaults can happen in any clinical setting, occur unexpectedly, and have a lasting impact on all involved. In an anonymous survey of 11,000 hospital workers, 18.8% reported being physically assaulted.1 Psychiatric clinicia

Remain calm. Although it may be difficult to do so immediately after being assaulted, remaining calm is essential. You may experience a myriad of emotions, such as anger, fear, vulnerability, shock, or guilt. Although these responses are normal, they can hinder your ability to accomplish subsequent tasks.

Recall the assault. Despite the unpleasantness of replaying the incident, recall as many details as you can and immediately write them down. Because of the copious amount of paperwork you may be required to file (eg, incident reports, employee health forms) and statements that you will likely repeat, having an accurate version of what happened is paramount to determining a course of action. You also may be required to give a statement to law enforcement officials.

Report the assault to your supervisor(s). Informing supervisors and colleagues of what happened could begin the implementation of corrective measures to decrease the risk of future assaults.

Talk about the incident with coworkers, supervisors, and friends to help process what happened, normalize what you are experiencing, and allow others to learn from you. Being assaulted can be traumatic and can result in experiencing post-assault symptoms, such as disruptions in sleep patterns, changes in appetite, and nightmares of the incident. These can be normal reactions to what is an abnormal situation. If necessary, seek medical assistance.

Evaluate the circumstances. Although you may not be at fault, consider if there may have been contributing factors:

- Were there signs of escalating aggressiveness in the patient’s behavior that you may have missed?

- Would the presence of a chaperone during interactions with the patient have reduced the risk of an assault?

- Did you maintain a safe distance from the patient?

- Were existing safety policies followed?

Examine your surroundings. Could the surroundings where the assault occurred have hindered your ability to escape? If so, can they be altered to increase your chance of escaping? Are there items that could be used as potential weapons and should be removed?Expect changes to processes and procedures as part of the reverberations after an assault. Your firsthand account of the assault can limit staff overreactions by analyzing whether existing policies were appropriately implemented, before deeming them ineffective and enacting new policies.

1. Pompeii LA, Schoenfisch AL, Lipscomb HJ, et al. Physical assault, physical threat, and verbal abuse perpetrated against hospital workers by patients or visitors in six U.S. hospitals. Am J Ind Med. 2015;58(11):1194-1204.

2. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(17):1661-1669.

3. Privitera M, Weisman R, Cerulli C, et al. Violence toward mental health staff and safety in the work environment. Occup Med (Lond). 2005;55(6):480-486.

Physical assaults by patients are an occupational hazard of practicing medicine. Assaults can happen in any clinical setting, occur unexpectedly, and have a lasting impact on all involved. In an anonymous survey of 11,000 hospital workers, 18.8% reported being physically assaulted.1 Psychiatric clinicia

Remain calm. Although it may be difficult to do so immediately after being assaulted, remaining calm is essential. You may experience a myriad of emotions, such as anger, fear, vulnerability, shock, or guilt. Although these responses are normal, they can hinder your ability to accomplish subsequent tasks.

Recall the assault. Despite the unpleasantness of replaying the incident, recall as many details as you can and immediately write them down. Because of the copious amount of paperwork you may be required to file (eg, incident reports, employee health forms) and statements that you will likely repeat, having an accurate version of what happened is paramount to determining a course of action. You also may be required to give a statement to law enforcement officials.

Report the assault to your supervisor(s). Informing supervisors and colleagues of what happened could begin the implementation of corrective measures to decrease the risk of future assaults.

Talk about the incident with coworkers, supervisors, and friends to help process what happened, normalize what you are experiencing, and allow others to learn from you. Being assaulted can be traumatic and can result in experiencing post-assault symptoms, such as disruptions in sleep patterns, changes in appetite, and nightmares of the incident. These can be normal reactions to what is an abnormal situation. If necessary, seek medical assistance.

Evaluate the circumstances. Although you may not be at fault, consider if there may have been contributing factors:

- Were there signs of escalating aggressiveness in the patient’s behavior that you may have missed?

- Would the presence of a chaperone during interactions with the patient have reduced the risk of an assault?

- Did you maintain a safe distance from the patient?

- Were existing safety policies followed?

Examine your surroundings. Could the surroundings where the assault occurred have hindered your ability to escape? If so, can they be altered to increase your chance of escaping? Are there items that could be used as potential weapons and should be removed?Expect changes to processes and procedures as part of the reverberations after an assault. Your firsthand account of the assault can limit staff overreactions by analyzing whether existing policies were appropriately implemented, before deeming them ineffective and enacting new policies.

Physical assaults by patients are an occupational hazard of practicing medicine. Assaults can happen in any clinical setting, occur unexpectedly, and have a lasting impact on all involved. In an anonymous survey of 11,000 hospital workers, 18.8% reported being physically assaulted.1 Psychiatric clinicia

Remain calm. Although it may be difficult to do so immediately after being assaulted, remaining calm is essential. You may experience a myriad of emotions, such as anger, fear, vulnerability, shock, or guilt. Although these responses are normal, they can hinder your ability to accomplish subsequent tasks.

Recall the assault. Despite the unpleasantness of replaying the incident, recall as many details as you can and immediately write them down. Because of the copious amount of paperwork you may be required to file (eg, incident reports, employee health forms) and statements that you will likely repeat, having an accurate version of what happened is paramount to determining a course of action. You also may be required to give a statement to law enforcement officials.

Report the assault to your supervisor(s). Informing supervisors and colleagues of what happened could begin the implementation of corrective measures to decrease the risk of future assaults.

Talk about the incident with coworkers, supervisors, and friends to help process what happened, normalize what you are experiencing, and allow others to learn from you. Being assaulted can be traumatic and can result in experiencing post-assault symptoms, such as disruptions in sleep patterns, changes in appetite, and nightmares of the incident. These can be normal reactions to what is an abnormal situation. If necessary, seek medical assistance.

Evaluate the circumstances. Although you may not be at fault, consider if there may have been contributing factors:

- Were there signs of escalating aggressiveness in the patient’s behavior that you may have missed?

- Would the presence of a chaperone during interactions with the patient have reduced the risk of an assault?

- Did you maintain a safe distance from the patient?

- Were existing safety policies followed?

Examine your surroundings. Could the surroundings where the assault occurred have hindered your ability to escape? If so, can they be altered to increase your chance of escaping? Are there items that could be used as potential weapons and should be removed?Expect changes to processes and procedures as part of the reverberations after an assault. Your firsthand account of the assault can limit staff overreactions by analyzing whether existing policies were appropriately implemented, before deeming them ineffective and enacting new policies.

1. Pompeii LA, Schoenfisch AL, Lipscomb HJ, et al. Physical assault, physical threat, and verbal abuse perpetrated against hospital workers by patients or visitors in six U.S. hospitals. Am J Ind Med. 2015;58(11):1194-1204.

2. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(17):1661-1669.

3. Privitera M, Weisman R, Cerulli C, et al. Violence toward mental health staff and safety in the work environment. Occup Med (Lond). 2005;55(6):480-486.

1. Pompeii LA, Schoenfisch AL, Lipscomb HJ, et al. Physical assault, physical threat, and verbal abuse perpetrated against hospital workers by patients or visitors in six U.S. hospitals. Am J Ind Med. 2015;58(11):1194-1204.

2. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(17):1661-1669.

3. Privitera M, Weisman R, Cerulli C, et al. Violence toward mental health staff and safety in the work environment. Occup Med (Lond). 2005;55(6):480-486.

Can melatonin alleviate antipsychotic-induced weight gain?

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) have been a remarkably effective innovation in psychotropic therapy. Unfortunately, the metabolic effects of these medications

Modabbernia et al1 demonstrated positive results from melatonin augmentation in an 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 48 patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Compared with patients who received olanzapine and placebo, those taking olanzapine and melatonin, 3 mg/d, had significantly less weight gain, smaller increases in abdominal obesity, and lower triglycerides. Patients who were given melatonin also had a significantly greater reduction on the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale score.1

Romo-Nava et al2 had similar findings in an 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Forty-four patients (24 with schizophrenia, 20 with bipolar disorder) who were taking clozapine, quetiapine, risperidone, or olanzapine received adjunctive melatonin, 5 mg/d, or placebo. Patients receiving melatonin had significantly less weight gain (P = .04) and significantly reduced diastolic blood pressure (5.1 vs 1.1 mm Hg; P = .03).

In both studies, researchers hypothesized that melatonin exerted its effect through the suprachiasmatic nucleus—the part of the hypothalamus that regulates body weight, energy balance, and metabolism. Exogenous melatonin suppresses intra-abdominal fat and restores serum leptin and insulin levels in middle-aged rats, partly due to correcting the age-related decline in melatonin production.3

Wang et al4 conducted a systematic review of using melatonin in patients taking SGAs. In addition to preventing metabolic adverse effects of antipsychotics, melatonin also reduced weight gain from lithium.

Early evidence suggests that this inexpensive and relatively safe augmenting agent can minimize metabolic effects of SGAs. It is surprising that scheduled melatonin has eluded popular use in psychiatry.

1. Modabbernia A, Heidari P, Soleimani R, et al. Melatonin for prevention of metabolic side-effects of olanzapine in patients with first-episode schizophrenia: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;53:133-140.

2. Romo-Nava F, Alvarez-Icaza González D, Fresán-Orellana A, et al. Melatonin attenuates antipsychotic metabolic effects: an eight-week randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(4):410-421.

3. Rasmussen DD, Marck BT, Boldt BM, et al. Suppression of hypothalamic pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) gene expression by daily melatonin supplementation in aging rats. J Pineal Res. 2003;34(2):127-133.

4. Wang HR, Woo YS, Bahk WM. The role of melatonin and melatonin agonists in counteracting antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects: a systematic review. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;31(6):301-306.

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) have been a remarkably effective innovation in psychotropic therapy. Unfortunately, the metabolic effects of these medications

Modabbernia et al1 demonstrated positive results from melatonin augmentation in an 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 48 patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Compared with patients who received olanzapine and placebo, those taking olanzapine and melatonin, 3 mg/d, had significantly less weight gain, smaller increases in abdominal obesity, and lower triglycerides. Patients who were given melatonin also had a significantly greater reduction on the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale score.1

Romo-Nava et al2 had similar findings in an 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Forty-four patients (24 with schizophrenia, 20 with bipolar disorder) who were taking clozapine, quetiapine, risperidone, or olanzapine received adjunctive melatonin, 5 mg/d, or placebo. Patients receiving melatonin had significantly less weight gain (P = .04) and significantly reduced diastolic blood pressure (5.1 vs 1.1 mm Hg; P = .03).

In both studies, researchers hypothesized that melatonin exerted its effect through the suprachiasmatic nucleus—the part of the hypothalamus that regulates body weight, energy balance, and metabolism. Exogenous melatonin suppresses intra-abdominal fat and restores serum leptin and insulin levels in middle-aged rats, partly due to correcting the age-related decline in melatonin production.3

Wang et al4 conducted a systematic review of using melatonin in patients taking SGAs. In addition to preventing metabolic adverse effects of antipsychotics, melatonin also reduced weight gain from lithium.

Early evidence suggests that this inexpensive and relatively safe augmenting agent can minimize metabolic effects of SGAs. It is surprising that scheduled melatonin has eluded popular use in psychiatry.

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) have been a remarkably effective innovation in psychotropic therapy. Unfortunately, the metabolic effects of these medications

Modabbernia et al1 demonstrated positive results from melatonin augmentation in an 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 48 patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Compared with patients who received olanzapine and placebo, those taking olanzapine and melatonin, 3 mg/d, had significantly less weight gain, smaller increases in abdominal obesity, and lower triglycerides. Patients who were given melatonin also had a significantly greater reduction on the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale score.1

Romo-Nava et al2 had similar findings in an 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Forty-four patients (24 with schizophrenia, 20 with bipolar disorder) who were taking clozapine, quetiapine, risperidone, or olanzapine received adjunctive melatonin, 5 mg/d, or placebo. Patients receiving melatonin had significantly less weight gain (P = .04) and significantly reduced diastolic blood pressure (5.1 vs 1.1 mm Hg; P = .03).

In both studies, researchers hypothesized that melatonin exerted its effect through the suprachiasmatic nucleus—the part of the hypothalamus that regulates body weight, energy balance, and metabolism. Exogenous melatonin suppresses intra-abdominal fat and restores serum leptin and insulin levels in middle-aged rats, partly due to correcting the age-related decline in melatonin production.3

Wang et al4 conducted a systematic review of using melatonin in patients taking SGAs. In addition to preventing metabolic adverse effects of antipsychotics, melatonin also reduced weight gain from lithium.

Early evidence suggests that this inexpensive and relatively safe augmenting agent can minimize metabolic effects of SGAs. It is surprising that scheduled melatonin has eluded popular use in psychiatry.

1. Modabbernia A, Heidari P, Soleimani R, et al. Melatonin for prevention of metabolic side-effects of olanzapine in patients with first-episode schizophrenia: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;53:133-140.

2. Romo-Nava F, Alvarez-Icaza González D, Fresán-Orellana A, et al. Melatonin attenuates antipsychotic metabolic effects: an eight-week randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(4):410-421.

3. Rasmussen DD, Marck BT, Boldt BM, et al. Suppression of hypothalamic pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) gene expression by daily melatonin supplementation in aging rats. J Pineal Res. 2003;34(2):127-133.

4. Wang HR, Woo YS, Bahk WM. The role of melatonin and melatonin agonists in counteracting antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects: a systematic review. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;31(6):301-306.

1. Modabbernia A, Heidari P, Soleimani R, et al. Melatonin for prevention of metabolic side-effects of olanzapine in patients with first-episode schizophrenia: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;53:133-140.

2. Romo-Nava F, Alvarez-Icaza González D, Fresán-Orellana A, et al. Melatonin attenuates antipsychotic metabolic effects: an eight-week randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(4):410-421.

3. Rasmussen DD, Marck BT, Boldt BM, et al. Suppression of hypothalamic pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) gene expression by daily melatonin supplementation in aging rats. J Pineal Res. 2003;34(2):127-133.

4. Wang HR, Woo YS, Bahk WM. The role of melatonin and melatonin agonists in counteracting antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects: a systematic review. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;31(6):301-306.

‘Flakka’: A low-cost, dangerous high

Use of α-pyrrolidinovalerophenone (α-PVP), a psychostimulant related to cathinone derivatives (“bath salts”), has been reported in the United States, especially in Florida.1 Known by the street names “flakka” or “gravel,” α-PVP is inexpensive, with a single dose (typically 100 mg) costing as little as $5.2 Alpha-PVP can be consumed via ingestion, injection, insufflation, or inhalation in vaporized forms, such as E-cigarettes, which deliver the drug quickly into the bloodstream and can make it easy to overdose.1 The low cost of this drug makes it likely to be abused. Here we review the mechanism of action and effects of α-PVP and summarize treatment options.

Mechanism of action

Alpha-PVP is a structural parent of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV)—the first widely abused synthetic cathinone.3 Much like cocaine, α-PVP stimulates the CNS by acting as a potent dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. However, unlike cocaine, it lacks any action on serotonin transporters. The pyrrolidine ring in MDPV and α-PVP is responsible for the highly potent dopamine reuptake inhibitor action of these agents.3

A wide range of adverse effects

Use of α-PVP results in a state of “excited delirium,” with symptoms such as hyperthermia, hallucinations, paranoia, violent aggression, and self-harm.1 Alpha-PVP is known to cause rhabdomyolysis.4 Some studies have reported cardiovascular effects, such as arterial hypertension, palpitations, dyspnea, vasoconstriction, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction (MI), and myocarditis.5 Alpha-PVP also may result in neurologic symptoms, including headache, mydriasis, lightheadedness, paresthesia, seizures, dystonic movements, tremor, amnesia, dysgeusia, cerebral edema, motor automatisms, muscle spasm, nystagmus, parkinsonism, and stroke.5 Death may occur by cardiac arrest, renal damage, or suicide.

Case reports. The effects of α-PVP have been documented in the literature:

- A 17-year-old girl was brought to an emergency department in Florida with acute onset of bizarre behavior, agitation, and altered mental status. It took 6 days and repeated administrations of olanzapine and lorazepam for the patient to become calm, alert, and oriented.2

- ST-elevated MI with several intracardiac thrombi was reported in a 41-year-old woman who used α-PVP.4

- In 2015, 18 deaths related to α-PVP use were reported in South Florida.5

- Deaths related to α-PVP use also have been reported in Japan and Australia.5

Treatment options

There are no treatment guidelines for α-PVP-related psychiatric symptoms. Case reports describe remission of symptoms following aggressive treatment with antipsychotics and benzodiazepines.2 Guidelines for treatment of stimulant-induced behavioral and psychotic symptoms6 may be considered for patients who have used α-PVP.

Reassurance and supportive care are the basic principles of such interventions. A quiet environment and benzodiazepines may provide relief of agitation. Antipsychotics may be helpful if a patient exhibits psychotic symptoms.

Similar drugs may emerge

In 2014, the DEA classified α-PVP as a Schedule I substance. Laws against the import of such substances via the Internet or other means also may help control the spread of this drug. However, chemically similar drugs that may elude drug screens are continually emerging. The lack of evidence-based guidelines on recognizing and managing intoxication, withdrawal, and long-term effects of α-PVP and other “designer drugs” calls for greater research in this emerging area of substance use disorders.

1. National Institute on Drug Abuse. “Flakka” (alpha-PVP). https://www.drugabuse.gov/emerging-trends/flakka-alpha-pvp. Accessed July 26, 2017.

2. Crespi C. Flakka-induced prolonged psychosis. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2016;2016:3460849. doi: 10.1155/2016/3460849.

3. Glennon RA, Young R. Neurobiology of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and α-pyrrolidinovalerophenone (α-PVP). Brain Res Bull. 2016;126(pt 1):111-126.

4. Cherry SV, Rodriguez YF. Synthetic stimulant reaching epidemic proportions: flakka-induced ST-elevation myocardial infarction with intracardiac thrombi. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017;31(1):e13-e14.

5. Katselou M, Papoutsis I, Nikolaou P, et al. α-PVP (“flakka”): a new synthetic cathinone invades the drug arena. Forensic Toxicol. 2016;34(1):41-50.

6. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Hallucinogen-related disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:648-655.

Use of α-pyrrolidinovalerophenone (α-PVP), a psychostimulant related to cathinone derivatives (“bath salts”), has been reported in the United States, especially in Florida.1 Known by the street names “flakka” or “gravel,” α-PVP is inexpensive, with a single dose (typically 100 mg) costing as little as $5.2 Alpha-PVP can be consumed via ingestion, injection, insufflation, or inhalation in vaporized forms, such as E-cigarettes, which deliver the drug quickly into the bloodstream and can make it easy to overdose.1 The low cost of this drug makes it likely to be abused. Here we review the mechanism of action and effects of α-PVP and summarize treatment options.

Mechanism of action

Alpha-PVP is a structural parent of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV)—the first widely abused synthetic cathinone.3 Much like cocaine, α-PVP stimulates the CNS by acting as a potent dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. However, unlike cocaine, it lacks any action on serotonin transporters. The pyrrolidine ring in MDPV and α-PVP is responsible for the highly potent dopamine reuptake inhibitor action of these agents.3

A wide range of adverse effects

Use of α-PVP results in a state of “excited delirium,” with symptoms such as hyperthermia, hallucinations, paranoia, violent aggression, and self-harm.1 Alpha-PVP is known to cause rhabdomyolysis.4 Some studies have reported cardiovascular effects, such as arterial hypertension, palpitations, dyspnea, vasoconstriction, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction (MI), and myocarditis.5 Alpha-PVP also may result in neurologic symptoms, including headache, mydriasis, lightheadedness, paresthesia, seizures, dystonic movements, tremor, amnesia, dysgeusia, cerebral edema, motor automatisms, muscle spasm, nystagmus, parkinsonism, and stroke.5 Death may occur by cardiac arrest, renal damage, or suicide.

Case reports. The effects of α-PVP have been documented in the literature:

- A 17-year-old girl was brought to an emergency department in Florida with acute onset of bizarre behavior, agitation, and altered mental status. It took 6 days and repeated administrations of olanzapine and lorazepam for the patient to become calm, alert, and oriented.2

- ST-elevated MI with several intracardiac thrombi was reported in a 41-year-old woman who used α-PVP.4

- In 2015, 18 deaths related to α-PVP use were reported in South Florida.5

- Deaths related to α-PVP use also have been reported in Japan and Australia.5

Treatment options

There are no treatment guidelines for α-PVP-related psychiatric symptoms. Case reports describe remission of symptoms following aggressive treatment with antipsychotics and benzodiazepines.2 Guidelines for treatment of stimulant-induced behavioral and psychotic symptoms6 may be considered for patients who have used α-PVP.

Reassurance and supportive care are the basic principles of such interventions. A quiet environment and benzodiazepines may provide relief of agitation. Antipsychotics may be helpful if a patient exhibits psychotic symptoms.

Similar drugs may emerge

In 2014, the DEA classified α-PVP as a Schedule I substance. Laws against the import of such substances via the Internet or other means also may help control the spread of this drug. However, chemically similar drugs that may elude drug screens are continually emerging. The lack of evidence-based guidelines on recognizing and managing intoxication, withdrawal, and long-term effects of α-PVP and other “designer drugs” calls for greater research in this emerging area of substance use disorders.

Use of α-pyrrolidinovalerophenone (α-PVP), a psychostimulant related to cathinone derivatives (“bath salts”), has been reported in the United States, especially in Florida.1 Known by the street names “flakka” or “gravel,” α-PVP is inexpensive, with a single dose (typically 100 mg) costing as little as $5.2 Alpha-PVP can be consumed via ingestion, injection, insufflation, or inhalation in vaporized forms, such as E-cigarettes, which deliver the drug quickly into the bloodstream and can make it easy to overdose.1 The low cost of this drug makes it likely to be abused. Here we review the mechanism of action and effects of α-PVP and summarize treatment options.

Mechanism of action

Alpha-PVP is a structural parent of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV)—the first widely abused synthetic cathinone.3 Much like cocaine, α-PVP stimulates the CNS by acting as a potent dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. However, unlike cocaine, it lacks any action on serotonin transporters. The pyrrolidine ring in MDPV and α-PVP is responsible for the highly potent dopamine reuptake inhibitor action of these agents.3

A wide range of adverse effects

Use of α-PVP results in a state of “excited delirium,” with symptoms such as hyperthermia, hallucinations, paranoia, violent aggression, and self-harm.1 Alpha-PVP is known to cause rhabdomyolysis.4 Some studies have reported cardiovascular effects, such as arterial hypertension, palpitations, dyspnea, vasoconstriction, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction (MI), and myocarditis.5 Alpha-PVP also may result in neurologic symptoms, including headache, mydriasis, lightheadedness, paresthesia, seizures, dystonic movements, tremor, amnesia, dysgeusia, cerebral edema, motor automatisms, muscle spasm, nystagmus, parkinsonism, and stroke.5 Death may occur by cardiac arrest, renal damage, or suicide.

Case reports. The effects of α-PVP have been documented in the literature:

- A 17-year-old girl was brought to an emergency department in Florida with acute onset of bizarre behavior, agitation, and altered mental status. It took 6 days and repeated administrations of olanzapine and lorazepam for the patient to become calm, alert, and oriented.2

- ST-elevated MI with several intracardiac thrombi was reported in a 41-year-old woman who used α-PVP.4

- In 2015, 18 deaths related to α-PVP use were reported in South Florida.5

- Deaths related to α-PVP use also have been reported in Japan and Australia.5

Treatment options

There are no treatment guidelines for α-PVP-related psychiatric symptoms. Case reports describe remission of symptoms following aggressive treatment with antipsychotics and benzodiazepines.2 Guidelines for treatment of stimulant-induced behavioral and psychotic symptoms6 may be considered for patients who have used α-PVP.

Reassurance and supportive care are the basic principles of such interventions. A quiet environment and benzodiazepines may provide relief of agitation. Antipsychotics may be helpful if a patient exhibits psychotic symptoms.

Similar drugs may emerge

In 2014, the DEA classified α-PVP as a Schedule I substance. Laws against the import of such substances via the Internet or other means also may help control the spread of this drug. However, chemically similar drugs that may elude drug screens are continually emerging. The lack of evidence-based guidelines on recognizing and managing intoxication, withdrawal, and long-term effects of α-PVP and other “designer drugs” calls for greater research in this emerging area of substance use disorders.

1. National Institute on Drug Abuse. “Flakka” (alpha-PVP). https://www.drugabuse.gov/emerging-trends/flakka-alpha-pvp. Accessed July 26, 2017.

2. Crespi C. Flakka-induced prolonged psychosis. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2016;2016:3460849. doi: 10.1155/2016/3460849.

3. Glennon RA, Young R. Neurobiology of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and α-pyrrolidinovalerophenone (α-PVP). Brain Res Bull. 2016;126(pt 1):111-126.

4. Cherry SV, Rodriguez YF. Synthetic stimulant reaching epidemic proportions: flakka-induced ST-elevation myocardial infarction with intracardiac thrombi. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017;31(1):e13-e14.

5. Katselou M, Papoutsis I, Nikolaou P, et al. α-PVP (“flakka”): a new synthetic cathinone invades the drug arena. Forensic Toxicol. 2016;34(1):41-50.

6. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Hallucinogen-related disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:648-655.

1. National Institute on Drug Abuse. “Flakka” (alpha-PVP). https://www.drugabuse.gov/emerging-trends/flakka-alpha-pvp. Accessed July 26, 2017.

2. Crespi C. Flakka-induced prolonged psychosis. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2016;2016:3460849. doi: 10.1155/2016/3460849.

3. Glennon RA, Young R. Neurobiology of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and α-pyrrolidinovalerophenone (α-PVP). Brain Res Bull. 2016;126(pt 1):111-126.

4. Cherry SV, Rodriguez YF. Synthetic stimulant reaching epidemic proportions: flakka-induced ST-elevation myocardial infarction with intracardiac thrombi. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017;31(1):e13-e14.

5. Katselou M, Papoutsis I, Nikolaou P, et al. α-PVP (“flakka”): a new synthetic cathinone invades the drug arena. Forensic Toxicol. 2016;34(1):41-50.

6. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Hallucinogen-related disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:648-655.

Caring for medical marijuana patients who request controlled prescriptions

Twenty-eight states and Washington, DC, have legalized marijuana for treating certain medical conditions, but the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) still classifies marijuana as a Schedule I drug “with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.”1 In certain states, clinicians can recommend, but not prescribe, medical marijuana. There is limited guidance in caring for patients who use medical marijuana and request or use DEA-controlled prescription medications, such as benzodiazepines, stimulants, and/or opiates. Physicians can take the following steps to ensure safe care for patients who use medical marijuana and request or take a DEA-controlled prescription medication:

1. Understand your patients’ point of view. Talk with patients who use medical marijuana about the history, frequency, and method of use, and reasons for using medical marijuana. Assess for psychiatric illnesses and any past or active treatment with DEA-controlled prescription medications.

2. Perform screens. Screen for risk factors, past psychiatric history, and prior or current substance use disorders. Treat any existing substance use disorders as appropriate.

3. Provide education. Discuss the risks of marijuana use and its potential adverse effects on the patient’s illness. Explain that marijuana is not currently an FDA-approved treatment and that there often are safer, efficacious alternatives.

4. Set clear boundaries. Be upfront about what is safe clinical practice or the usual standard of medical care and practice within the scope of state and federal laws. Document treatment agreements, utilize prescription drug monitoring programs, and use blood and/or urine toxicology screens as needed. Be aware that a routine drug screen can detect marijuana exposure but may vary in detecting the quantity or length of marijuana use.2

5. Try harm reduction. Any marijuana use, including use that falls short of a Cannabis use disorder, may adversely impact cognition, mood, and/or anxiety.3 Reducing use or abstaining from marijuana use for at least 4 weeks4,5 or reducing or discontinuing the DEA-controlled medication if a patient continues marijuana use are reasonable interventions to see if psychiatric symptoms improve or remit. Polypharmacy with marijuana may place a patient at risk for substance use disorders or additive adverse effects or can hinder the recovery process.

6. Consider alternatives. If a patient feels strongly about continuing medical marijuana use, and you feel that their marijuana use is not clinically harmful and that psychiatric symptoms require treatment, consider medications without a known potential for abuse (eg, antidepressants, buspirone, or hydroxyzine for anxiety; alpha-agonists or atomoxetine for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, etc.). Start such medications at low dosages, titrate slowly, and monitor for benefits and adverse effects.

7. Continue the conversation. Maintain an open and nonjudgmental stance when discussing medical marijuana. Roll with resistance, and frame discussions toward a shared goal of improving the patient’s mental health as safely as possible while using the best medical evidence available.

8. Offer additional support. Refer patients any additional services as appropriate, which may include psychotherapy, a pain specialist, or a substance abuse specialist.