User login

Key takeaways from ACP’s new Tx guidelines for adults with major depressive disorder

In January 2023, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published updated recommendations on the treatment of adults with major depressive disorder (MDD).1 The ACP guidelines address initial treatment of patients in the acute phase of mild and moderate-to-severe MDD. Here’s what the ACP recommends, as well as 6 important takeaways.

Recommendations for initial treatment of those with mild or moderate-to-severe MDD center around cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and second-generation antidepressants (SGA). For patients in the acute phase of mild MDD, the recommendation is for monotherapy with CBT. However, if CBT is not an option due to cost and/or availability of services, the use of an SGA is acceptable.

For patients in the acute phase of moderate-to-severe MDD, either CBT, an SGA, or a combination of both is recommended.

If initial treatment does not work … Up to 70% of patients with moderate-to-severe MDD will not respond to the initial therapy chosen. If a patient does not respond to initial treatment with an SGA, consider 1 of the following:

- Switching to CBT

- Adding on CBT while continuing the SGA

- Changing to a different SGA

- Adding a second pharmacologic agent.

6 key takeaways. The full guideline should be read for a more complete discussion of the many clinical considerations of these treatment options. However, the most important points include:

• Employ shared clinical decision-making and consider the individual characteristics of each patient when making treatment decisions.

• Consider generic options when using an SGA; generic options appear to be as effective as more expensive brand-name products.

• Start with a low-dose SGA and increase gradually to an approved maximum dose before determining there has been no response.

• Monitor frequently for medication adverse effects.

• Monitor the patient for thoughts about self-harm for the first 2 months.

• Continue treatment for 4 to 9 months once remission is achieved.

A word about strength of evidence. While these recommendations are based on an extensive review of the best available evidence, most are based on low-certainty evidence—illustrating the amount of clinical research still needed on this topic. The exceptions are monotherapy with either CBT or SGA for initial treatment of moderate-to-severe MDD, both of which are based on moderate-strength evidence and received a strong recommendation. The panel felt there was insufficient evidence to assess complementary and alternative interventions including exercise and omega-3 fatty acids.

1. Qaseem A, Owens D, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, et al; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments of adults in the acute phase of major depressive disorder: a living clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. Published online January 24, 2023. doi: 10.7326/M22-2056

In January 2023, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published updated recommendations on the treatment of adults with major depressive disorder (MDD).1 The ACP guidelines address initial treatment of patients in the acute phase of mild and moderate-to-severe MDD. Here’s what the ACP recommends, as well as 6 important takeaways.

Recommendations for initial treatment of those with mild or moderate-to-severe MDD center around cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and second-generation antidepressants (SGA). For patients in the acute phase of mild MDD, the recommendation is for monotherapy with CBT. However, if CBT is not an option due to cost and/or availability of services, the use of an SGA is acceptable.

For patients in the acute phase of moderate-to-severe MDD, either CBT, an SGA, or a combination of both is recommended.

If initial treatment does not work … Up to 70% of patients with moderate-to-severe MDD will not respond to the initial therapy chosen. If a patient does not respond to initial treatment with an SGA, consider 1 of the following:

- Switching to CBT

- Adding on CBT while continuing the SGA

- Changing to a different SGA

- Adding a second pharmacologic agent.

6 key takeaways. The full guideline should be read for a more complete discussion of the many clinical considerations of these treatment options. However, the most important points include:

• Employ shared clinical decision-making and consider the individual characteristics of each patient when making treatment decisions.

• Consider generic options when using an SGA; generic options appear to be as effective as more expensive brand-name products.

• Start with a low-dose SGA and increase gradually to an approved maximum dose before determining there has been no response.

• Monitor frequently for medication adverse effects.

• Monitor the patient for thoughts about self-harm for the first 2 months.

• Continue treatment for 4 to 9 months once remission is achieved.

A word about strength of evidence. While these recommendations are based on an extensive review of the best available evidence, most are based on low-certainty evidence—illustrating the amount of clinical research still needed on this topic. The exceptions are monotherapy with either CBT or SGA for initial treatment of moderate-to-severe MDD, both of which are based on moderate-strength evidence and received a strong recommendation. The panel felt there was insufficient evidence to assess complementary and alternative interventions including exercise and omega-3 fatty acids.

In January 2023, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published updated recommendations on the treatment of adults with major depressive disorder (MDD).1 The ACP guidelines address initial treatment of patients in the acute phase of mild and moderate-to-severe MDD. Here’s what the ACP recommends, as well as 6 important takeaways.

Recommendations for initial treatment of those with mild or moderate-to-severe MDD center around cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and second-generation antidepressants (SGA). For patients in the acute phase of mild MDD, the recommendation is for monotherapy with CBT. However, if CBT is not an option due to cost and/or availability of services, the use of an SGA is acceptable.

For patients in the acute phase of moderate-to-severe MDD, either CBT, an SGA, or a combination of both is recommended.

If initial treatment does not work … Up to 70% of patients with moderate-to-severe MDD will not respond to the initial therapy chosen. If a patient does not respond to initial treatment with an SGA, consider 1 of the following:

- Switching to CBT

- Adding on CBT while continuing the SGA

- Changing to a different SGA

- Adding a second pharmacologic agent.

6 key takeaways. The full guideline should be read for a more complete discussion of the many clinical considerations of these treatment options. However, the most important points include:

• Employ shared clinical decision-making and consider the individual characteristics of each patient when making treatment decisions.

• Consider generic options when using an SGA; generic options appear to be as effective as more expensive brand-name products.

• Start with a low-dose SGA and increase gradually to an approved maximum dose before determining there has been no response.

• Monitor frequently for medication adverse effects.

• Monitor the patient for thoughts about self-harm for the first 2 months.

• Continue treatment for 4 to 9 months once remission is achieved.

A word about strength of evidence. While these recommendations are based on an extensive review of the best available evidence, most are based on low-certainty evidence—illustrating the amount of clinical research still needed on this topic. The exceptions are monotherapy with either CBT or SGA for initial treatment of moderate-to-severe MDD, both of which are based on moderate-strength evidence and received a strong recommendation. The panel felt there was insufficient evidence to assess complementary and alternative interventions including exercise and omega-3 fatty acids.

1. Qaseem A, Owens D, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, et al; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments of adults in the acute phase of major depressive disorder: a living clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. Published online January 24, 2023. doi: 10.7326/M22-2056

1. Qaseem A, Owens D, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, et al; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments of adults in the acute phase of major depressive disorder: a living clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. Published online January 24, 2023. doi: 10.7326/M22-2056

CDC updates guidance on opioid prescribing in adults

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently published updated guidelines on prescribing opioids for pain that stress the need for a flexible and individual approach to pain management.1 New recommendations emphasize the use of nonopioid therapies whenever appropriate, support consideration of opioid therapy for patients with acute pain when the benefits are expected to outweigh the risks, and urge clinicians to work with patients receiving opioid therapy to determine whether it should be continued or tapered.

This revision to the agency’s 2016 guidelines is aimed at primary care clinicians who prescribe opioids to adult outpatients for treatment of pain. The recommendations are not meant for patients with sickle-cell disease or cancer-related pain, or those receiving palliative and end-of-life care.

Why an update was needed. In 2021, more than 107,000 Americans died of a drug overdose.2 Although prescription opioids caused only about 16% of these deaths, they account for a population death rate of 4:100,000—which, despite national efforts, has not changed much since 2013.3,4

Following publication of the CDC’s 2016 guidelines on prescribing opioids for chronic pain,5 there was a decline in opioid prescribing but not in related deaths. Furthermore, there appeared to have been some negative effects of reduced prescribing, including untreated and undertreated pain, and rapid tapering or sudden discontinuation of opioids in chronic users, causing withdrawal symptoms and psychological distress in these patients. To address these issues, the CDC published the new guideline in 2022.1

Categories of pain. The guideline panel classified pain into 3 categories: acute pain (duration of < 1 month), subacute pain (duration of 1-3 months), and chronic pain (duration of > 3 months).

When to prescribe opioids. The guidelines recommend a new approach to deciding whether to prescribe opioid therapy. In most cases, nonopioid options—such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and exercise—should be tried first, since they are as effective as opioids for many types of acute, subacute, and chronic pain. Opioids should be considered if these options fail and the potential benefits outweigh the risks. In moderate-to-severe acute pain, opioids are an option if NSAIDs are unlikely to be effective or are contraindicated.1

How to prescribe opioids. Before prescribing opioids, clinicians should discuss with the patient the known risks and benefits and offer an accompanying prescription for naloxone. Opioids should be prescribed at the lowest effective dose and for a time period limited to the expected duration of the pain. When starting opioids, immediate-release opioids should be prescribed instead of extended-release or long-acting opioids.1

Precautionary measures. Clinicians should review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions via their state’s prescription drug monitoring program and consider the use of toxicology testing to determine whether the patient is receiving high-risk opioid dosages or combinations. Clinicians should be especially cautious about prescribing opioids and benzodiazepines concurrently.1

Continue or stop opioid treatment? A new recommendation advises clinicians to individually assess the benefits and risks of continuing therapy for patients who have been receiving opioids chronically. Whenever the decision is made to stop or reduce treatment, remember that opioid therapy should not be stopped abruptly or reduced quickly. The guideline panel suggests tapering by 10% per month.1

Finally, patients with opioid use disorder should be offered or referred for treatment with medications. Detoxification alone, without medication, is not recommended.1

1. Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, et al. CDC clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain—United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71:1-95. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1

2. CDC. US overdose deaths in 2021 increased half as much as in 2020—but are still up 15%. Published May 11, 2022. Accessed January 25, 2023. www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2022/202205.htm

3. CDC. SUDORS Dashboard: fatal overdose data. Updated December 8, 2022. Accessed January 25, 2023. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/fatal/dashboard/index.html

4. Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, et al. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202-207. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4

5. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1:26987082

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently published updated guidelines on prescribing opioids for pain that stress the need for a flexible and individual approach to pain management.1 New recommendations emphasize the use of nonopioid therapies whenever appropriate, support consideration of opioid therapy for patients with acute pain when the benefits are expected to outweigh the risks, and urge clinicians to work with patients receiving opioid therapy to determine whether it should be continued or tapered.

This revision to the agency’s 2016 guidelines is aimed at primary care clinicians who prescribe opioids to adult outpatients for treatment of pain. The recommendations are not meant for patients with sickle-cell disease or cancer-related pain, or those receiving palliative and end-of-life care.

Why an update was needed. In 2021, more than 107,000 Americans died of a drug overdose.2 Although prescription opioids caused only about 16% of these deaths, they account for a population death rate of 4:100,000—which, despite national efforts, has not changed much since 2013.3,4

Following publication of the CDC’s 2016 guidelines on prescribing opioids for chronic pain,5 there was a decline in opioid prescribing but not in related deaths. Furthermore, there appeared to have been some negative effects of reduced prescribing, including untreated and undertreated pain, and rapid tapering or sudden discontinuation of opioids in chronic users, causing withdrawal symptoms and psychological distress in these patients. To address these issues, the CDC published the new guideline in 2022.1

Categories of pain. The guideline panel classified pain into 3 categories: acute pain (duration of < 1 month), subacute pain (duration of 1-3 months), and chronic pain (duration of > 3 months).

When to prescribe opioids. The guidelines recommend a new approach to deciding whether to prescribe opioid therapy. In most cases, nonopioid options—such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and exercise—should be tried first, since they are as effective as opioids for many types of acute, subacute, and chronic pain. Opioids should be considered if these options fail and the potential benefits outweigh the risks. In moderate-to-severe acute pain, opioids are an option if NSAIDs are unlikely to be effective or are contraindicated.1

How to prescribe opioids. Before prescribing opioids, clinicians should discuss with the patient the known risks and benefits and offer an accompanying prescription for naloxone. Opioids should be prescribed at the lowest effective dose and for a time period limited to the expected duration of the pain. When starting opioids, immediate-release opioids should be prescribed instead of extended-release or long-acting opioids.1

Precautionary measures. Clinicians should review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions via their state’s prescription drug monitoring program and consider the use of toxicology testing to determine whether the patient is receiving high-risk opioid dosages or combinations. Clinicians should be especially cautious about prescribing opioids and benzodiazepines concurrently.1

Continue or stop opioid treatment? A new recommendation advises clinicians to individually assess the benefits and risks of continuing therapy for patients who have been receiving opioids chronically. Whenever the decision is made to stop or reduce treatment, remember that opioid therapy should not be stopped abruptly or reduced quickly. The guideline panel suggests tapering by 10% per month.1

Finally, patients with opioid use disorder should be offered or referred for treatment with medications. Detoxification alone, without medication, is not recommended.1

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently published updated guidelines on prescribing opioids for pain that stress the need for a flexible and individual approach to pain management.1 New recommendations emphasize the use of nonopioid therapies whenever appropriate, support consideration of opioid therapy for patients with acute pain when the benefits are expected to outweigh the risks, and urge clinicians to work with patients receiving opioid therapy to determine whether it should be continued or tapered.

This revision to the agency’s 2016 guidelines is aimed at primary care clinicians who prescribe opioids to adult outpatients for treatment of pain. The recommendations are not meant for patients with sickle-cell disease or cancer-related pain, or those receiving palliative and end-of-life care.

Why an update was needed. In 2021, more than 107,000 Americans died of a drug overdose.2 Although prescription opioids caused only about 16% of these deaths, they account for a population death rate of 4:100,000—which, despite national efforts, has not changed much since 2013.3,4

Following publication of the CDC’s 2016 guidelines on prescribing opioids for chronic pain,5 there was a decline in opioid prescribing but not in related deaths. Furthermore, there appeared to have been some negative effects of reduced prescribing, including untreated and undertreated pain, and rapid tapering or sudden discontinuation of opioids in chronic users, causing withdrawal symptoms and psychological distress in these patients. To address these issues, the CDC published the new guideline in 2022.1

Categories of pain. The guideline panel classified pain into 3 categories: acute pain (duration of < 1 month), subacute pain (duration of 1-3 months), and chronic pain (duration of > 3 months).

When to prescribe opioids. The guidelines recommend a new approach to deciding whether to prescribe opioid therapy. In most cases, nonopioid options—such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and exercise—should be tried first, since they are as effective as opioids for many types of acute, subacute, and chronic pain. Opioids should be considered if these options fail and the potential benefits outweigh the risks. In moderate-to-severe acute pain, opioids are an option if NSAIDs are unlikely to be effective or are contraindicated.1

How to prescribe opioids. Before prescribing opioids, clinicians should discuss with the patient the known risks and benefits and offer an accompanying prescription for naloxone. Opioids should be prescribed at the lowest effective dose and for a time period limited to the expected duration of the pain. When starting opioids, immediate-release opioids should be prescribed instead of extended-release or long-acting opioids.1

Precautionary measures. Clinicians should review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions via their state’s prescription drug monitoring program and consider the use of toxicology testing to determine whether the patient is receiving high-risk opioid dosages or combinations. Clinicians should be especially cautious about prescribing opioids and benzodiazepines concurrently.1

Continue or stop opioid treatment? A new recommendation advises clinicians to individually assess the benefits and risks of continuing therapy for patients who have been receiving opioids chronically. Whenever the decision is made to stop or reduce treatment, remember that opioid therapy should not be stopped abruptly or reduced quickly. The guideline panel suggests tapering by 10% per month.1

Finally, patients with opioid use disorder should be offered or referred for treatment with medications. Detoxification alone, without medication, is not recommended.1

1. Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, et al. CDC clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain—United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71:1-95. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1

2. CDC. US overdose deaths in 2021 increased half as much as in 2020—but are still up 15%. Published May 11, 2022. Accessed January 25, 2023. www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2022/202205.htm

3. CDC. SUDORS Dashboard: fatal overdose data. Updated December 8, 2022. Accessed January 25, 2023. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/fatal/dashboard/index.html

4. Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, et al. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202-207. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4

5. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1:26987082

1. Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, et al. CDC clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain—United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71:1-95. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1

2. CDC. US overdose deaths in 2021 increased half as much as in 2020—but are still up 15%. Published May 11, 2022. Accessed January 25, 2023. www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2022/202205.htm

3. CDC. SUDORS Dashboard: fatal overdose data. Updated December 8, 2022. Accessed January 25, 2023. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/fatal/dashboard/index.html

4. Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, et al. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202-207. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4

5. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1:26987082

Latent TB: The case for vigilance

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released draft recommendations on screening for tuberculosis (TB).1 The USPSTF continues to recommend screening for latent TB infection (LTBI) in those at high risk.

Why is this important? Up to one-quarter of the world’s population has been infected with TB, according to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates. In 2021, active TB was diagnosed in 10.6 million people, and it caused 1.6 million deaths.2 Worldwide, TB is still a major cause of mortality: It is the 13th leading cause of death and is the leading cause of infectious disease mortality in non-COVID years.

Although the rate of active TB in the United States has been declining for decades (from 30.7/100,000 in 1960 to 2.4/100,000 in 2021), 7882 cases were reported in 2021, and an estimated 13 million people in the United States have LTBI.3 If not treated, 5% to 10% of LTBI cases will progress to active TB. This risk is higher in those with certain medical conditions.3 People born outside the United States currently account for 71.4% of reported TB cases in the United States.3

To reduce the morbidity and mortality of TB, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), WHO, and USPSTF all recommend screening for and treating LTBI. An effective approach to TB control also includes early detection and completion of treatment for active TB, as well as testing contacts of active TB cases.

Who should be screened? Those at high risk for LTBI include those who were born in, or who have resided in, countries with high rates of TB (eg, Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, and Russia); those who have lived in a correctional facility or homeless shelter; household and other close contacts of active TB cases; and health care workers who provide care to patients with TB.

Some chronic medical conditions can increase risk for progression to active TB in those with LTBI. Patients who should be tested for LTBI as part of their routine care include those who are HIV positive; are receiving immunosuppressive therapy (chemotherapy, biological immune suppressants); have received an organ transplant; have silicosis; use illicit injected drugs; and/or have had a gastrectomy or jejunoileal bypass.

In addition, local communities may have populations or geographic regions in which TB rates are high. Family physicians can obtain this information from their state or local health departments.

There are 2 screening tests for LTBI: TB blood tests (interferon-gamma release assays [IGRAs]) and the Mantoux tuberculin skin test (TST). Two TB blood tests are available in the United States: QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus (QFT-Plus) and T-SPOT.TB test (T-Spot).

There are advantages and disadvantages to both types of tests. A TST requires accurate administration and interpretation and 2 clinic visits, 48 to 72 hours apart. The cutoff on a positive test (5, 10, or 15 mm) depends on the patient’s age and risk.4 An IGRA should be processed within 8 to 32 hours and is more expensive. However, a major advantage is that it is more specific, because it is unaffected by previous vaccination with bacille Calmette-Guérin or by most nontuberculous mycobacteria infections.

To rule out active TB ... If a TB screening test is positive, the recommended work-up is to ask about TB symptoms and perform a chest x-ray to rule out active pulmonary TB. Sputum collection for acid-fast smear and culture should be ordered for anyone with a suspicious chest x-ray, respiratory symptoms consistent with TB, or HIV infection.

Treatment for LTBI markedly reduces the risk for active TB. There are 4 options:

- Isoniazid (INH) plus rifapentine (RPT) once per week for 3 months.

- Rifampin (RIF) daily for 4 months.

- INH plus RIF daily for 3 months.

- INH daily for 6 or 9 months.

Details about the variables to consider in choosing a regimen are described on the CDC website.4,5

Know your resources. Local and state public health departments should have TB control programs and are sources of information on TB diagnosis and treatment; they also can assist with follow-up of TB contacts.6 Although LTBI is a reportable condition only in young children, any suspicion of community spread of active TB should be reported to the public health department.

1. USPSTF. Latent tuberculosis infection in adults: screening. Draft recommendation statement. Published November 22, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/latent-tuberculosis-infection-adults

2. WHO. Tuberculosis: key facts. Updated October 27, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

3. CDC. Tuberculosis: data and statistics. Updated November 29, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/default.htm

4. CDC. Latent TB infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Updated February 3, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/pdf/LTBIbooklet508.pdf

5. CDC. Treatment regimens for latent TB infection. Updated February 13, 2020. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm

6. CDC. TB control offices. Updated March 28, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/links/tboffices.htm

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released draft recommendations on screening for tuberculosis (TB).1 The USPSTF continues to recommend screening for latent TB infection (LTBI) in those at high risk.

Why is this important? Up to one-quarter of the world’s population has been infected with TB, according to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates. In 2021, active TB was diagnosed in 10.6 million people, and it caused 1.6 million deaths.2 Worldwide, TB is still a major cause of mortality: It is the 13th leading cause of death and is the leading cause of infectious disease mortality in non-COVID years.

Although the rate of active TB in the United States has been declining for decades (from 30.7/100,000 in 1960 to 2.4/100,000 in 2021), 7882 cases were reported in 2021, and an estimated 13 million people in the United States have LTBI.3 If not treated, 5% to 10% of LTBI cases will progress to active TB. This risk is higher in those with certain medical conditions.3 People born outside the United States currently account for 71.4% of reported TB cases in the United States.3

To reduce the morbidity and mortality of TB, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), WHO, and USPSTF all recommend screening for and treating LTBI. An effective approach to TB control also includes early detection and completion of treatment for active TB, as well as testing contacts of active TB cases.

Who should be screened? Those at high risk for LTBI include those who were born in, or who have resided in, countries with high rates of TB (eg, Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, and Russia); those who have lived in a correctional facility or homeless shelter; household and other close contacts of active TB cases; and health care workers who provide care to patients with TB.

Some chronic medical conditions can increase risk for progression to active TB in those with LTBI. Patients who should be tested for LTBI as part of their routine care include those who are HIV positive; are receiving immunosuppressive therapy (chemotherapy, biological immune suppressants); have received an organ transplant; have silicosis; use illicit injected drugs; and/or have had a gastrectomy or jejunoileal bypass.

In addition, local communities may have populations or geographic regions in which TB rates are high. Family physicians can obtain this information from their state or local health departments.

There are 2 screening tests for LTBI: TB blood tests (interferon-gamma release assays [IGRAs]) and the Mantoux tuberculin skin test (TST). Two TB blood tests are available in the United States: QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus (QFT-Plus) and T-SPOT.TB test (T-Spot).

There are advantages and disadvantages to both types of tests. A TST requires accurate administration and interpretation and 2 clinic visits, 48 to 72 hours apart. The cutoff on a positive test (5, 10, or 15 mm) depends on the patient’s age and risk.4 An IGRA should be processed within 8 to 32 hours and is more expensive. However, a major advantage is that it is more specific, because it is unaffected by previous vaccination with bacille Calmette-Guérin or by most nontuberculous mycobacteria infections.

To rule out active TB ... If a TB screening test is positive, the recommended work-up is to ask about TB symptoms and perform a chest x-ray to rule out active pulmonary TB. Sputum collection for acid-fast smear and culture should be ordered for anyone with a suspicious chest x-ray, respiratory symptoms consistent with TB, or HIV infection.

Treatment for LTBI markedly reduces the risk for active TB. There are 4 options:

- Isoniazid (INH) plus rifapentine (RPT) once per week for 3 months.

- Rifampin (RIF) daily for 4 months.

- INH plus RIF daily for 3 months.

- INH daily for 6 or 9 months.

Details about the variables to consider in choosing a regimen are described on the CDC website.4,5

Know your resources. Local and state public health departments should have TB control programs and are sources of information on TB diagnosis and treatment; they also can assist with follow-up of TB contacts.6 Although LTBI is a reportable condition only in young children, any suspicion of community spread of active TB should be reported to the public health department.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released draft recommendations on screening for tuberculosis (TB).1 The USPSTF continues to recommend screening for latent TB infection (LTBI) in those at high risk.

Why is this important? Up to one-quarter of the world’s population has been infected with TB, according to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates. In 2021, active TB was diagnosed in 10.6 million people, and it caused 1.6 million deaths.2 Worldwide, TB is still a major cause of mortality: It is the 13th leading cause of death and is the leading cause of infectious disease mortality in non-COVID years.

Although the rate of active TB in the United States has been declining for decades (from 30.7/100,000 in 1960 to 2.4/100,000 in 2021), 7882 cases were reported in 2021, and an estimated 13 million people in the United States have LTBI.3 If not treated, 5% to 10% of LTBI cases will progress to active TB. This risk is higher in those with certain medical conditions.3 People born outside the United States currently account for 71.4% of reported TB cases in the United States.3

To reduce the morbidity and mortality of TB, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), WHO, and USPSTF all recommend screening for and treating LTBI. An effective approach to TB control also includes early detection and completion of treatment for active TB, as well as testing contacts of active TB cases.

Who should be screened? Those at high risk for LTBI include those who were born in, or who have resided in, countries with high rates of TB (eg, Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, and Russia); those who have lived in a correctional facility or homeless shelter; household and other close contacts of active TB cases; and health care workers who provide care to patients with TB.

Some chronic medical conditions can increase risk for progression to active TB in those with LTBI. Patients who should be tested for LTBI as part of their routine care include those who are HIV positive; are receiving immunosuppressive therapy (chemotherapy, biological immune suppressants); have received an organ transplant; have silicosis; use illicit injected drugs; and/or have had a gastrectomy or jejunoileal bypass.

In addition, local communities may have populations or geographic regions in which TB rates are high. Family physicians can obtain this information from their state or local health departments.

There are 2 screening tests for LTBI: TB blood tests (interferon-gamma release assays [IGRAs]) and the Mantoux tuberculin skin test (TST). Two TB blood tests are available in the United States: QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus (QFT-Plus) and T-SPOT.TB test (T-Spot).

There are advantages and disadvantages to both types of tests. A TST requires accurate administration and interpretation and 2 clinic visits, 48 to 72 hours apart. The cutoff on a positive test (5, 10, or 15 mm) depends on the patient’s age and risk.4 An IGRA should be processed within 8 to 32 hours and is more expensive. However, a major advantage is that it is more specific, because it is unaffected by previous vaccination with bacille Calmette-Guérin or by most nontuberculous mycobacteria infections.

To rule out active TB ... If a TB screening test is positive, the recommended work-up is to ask about TB symptoms and perform a chest x-ray to rule out active pulmonary TB. Sputum collection for acid-fast smear and culture should be ordered for anyone with a suspicious chest x-ray, respiratory symptoms consistent with TB, or HIV infection.

Treatment for LTBI markedly reduces the risk for active TB. There are 4 options:

- Isoniazid (INH) plus rifapentine (RPT) once per week for 3 months.

- Rifampin (RIF) daily for 4 months.

- INH plus RIF daily for 3 months.

- INH daily for 6 or 9 months.

Details about the variables to consider in choosing a regimen are described on the CDC website.4,5

Know your resources. Local and state public health departments should have TB control programs and are sources of information on TB diagnosis and treatment; they also can assist with follow-up of TB contacts.6 Although LTBI is a reportable condition only in young children, any suspicion of community spread of active TB should be reported to the public health department.

1. USPSTF. Latent tuberculosis infection in adults: screening. Draft recommendation statement. Published November 22, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/latent-tuberculosis-infection-adults

2. WHO. Tuberculosis: key facts. Updated October 27, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

3. CDC. Tuberculosis: data and statistics. Updated November 29, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/default.htm

4. CDC. Latent TB infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Updated February 3, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/pdf/LTBIbooklet508.pdf

5. CDC. Treatment regimens for latent TB infection. Updated February 13, 2020. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm

6. CDC. TB control offices. Updated March 28, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/links/tboffices.htm

1. USPSTF. Latent tuberculosis infection in adults: screening. Draft recommendation statement. Published November 22, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/latent-tuberculosis-infection-adults

2. WHO. Tuberculosis: key facts. Updated October 27, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

3. CDC. Tuberculosis: data and statistics. Updated November 29, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/default.htm

4. CDC. Latent TB infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Updated February 3, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/pdf/LTBIbooklet508.pdf

5. CDC. Treatment regimens for latent TB infection. Updated February 13, 2020. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm

6. CDC. TB control offices. Updated March 28, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/links/tboffices.htm

Whom to screen for anxiety and depression: Updated USPSTF recommendations

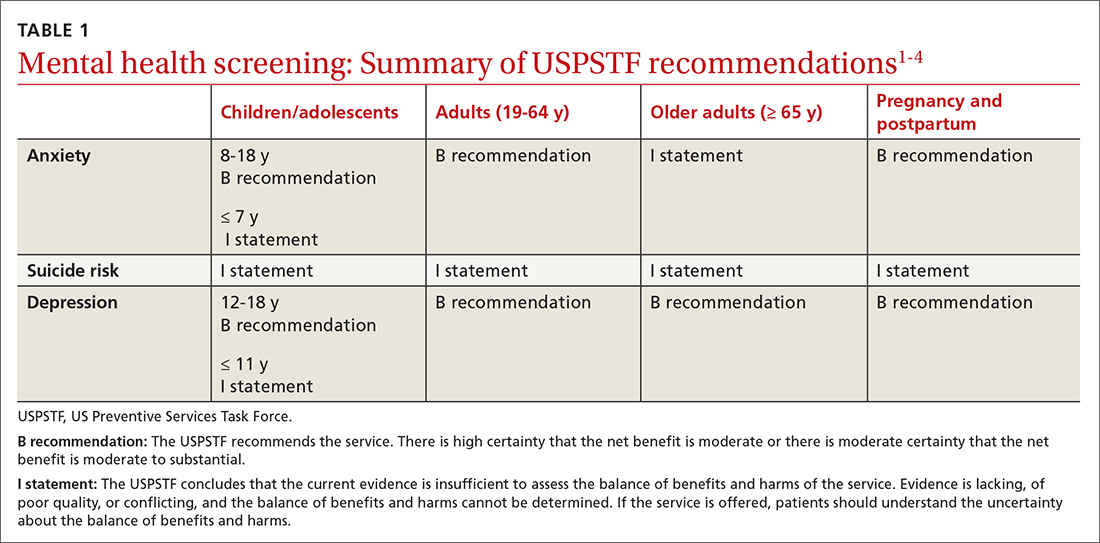

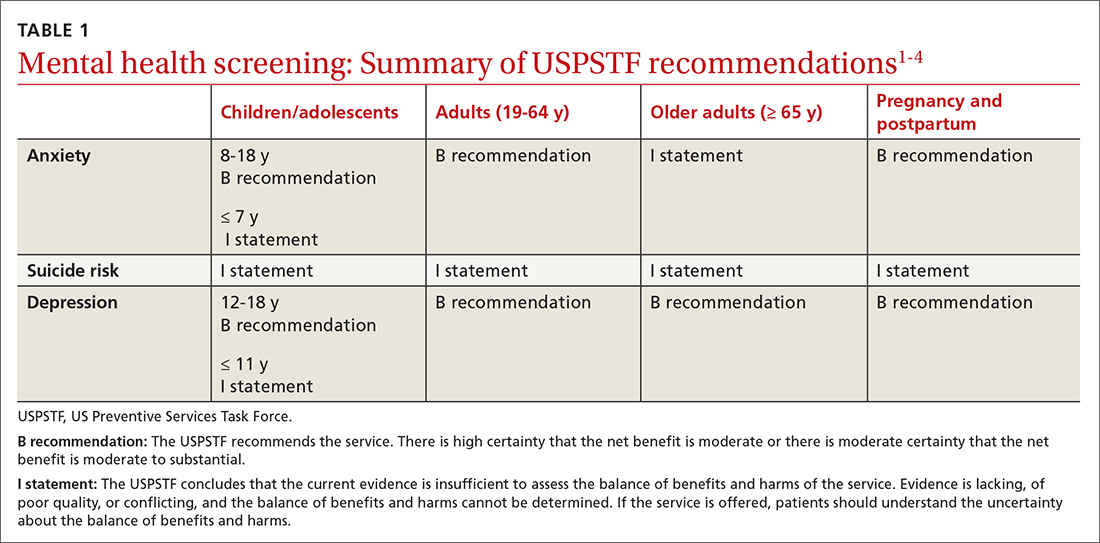

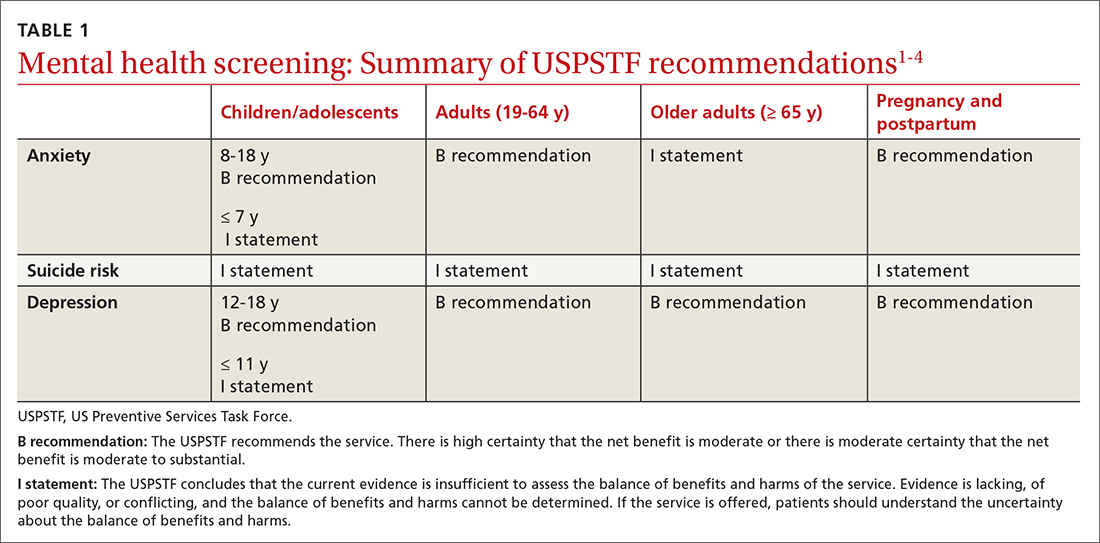

In September 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released 2 sets of draft recommendations on screening for 3 mental health conditions in adults: anxiety, depression, and suicide risk.1,2 These draft recommendations are summarized in TABLE 11-4 along with finalized recommendations on the same topics for children and adolescents, published in October 2022.3,4

The recommendations on depression and suicide risk screening in adults are updates of previous recommendations (2016 for depression and 2014 for suicide risk) with no major changes. Screening for anxiety is a topic addressed for the first time this year for adults and for children and adolescents.1,3

The recommendations are fairly consistent between age groups. A “B” recommendation supports screening for major depression in all patients starting at age 12 years, including during pregnancy and the postpartum period. (See TABLE 1 for grade definitions.) For all age groups, evidence was insufficient to recommend screening for suicide risk. A “B” recommendation was also assigned to screening for anxiety in those ages 8 to 64 years. The USPSTF believes the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation on screening for anxiety among adults ≥ 65 years of age.

The anxiety disorders common to both children and adults included in the USPSTF recommendations are generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, separation anxiety disorder, phobias, selective mutism, and anxiety type not specified. For adults, the USPSTF also includes substance/medication-induced anxiety and anxiety due to other medical conditions.

Adults with anxiety often present with generalized complaints such as sleep disturbance, pain, and other somatic disorders that can remain undiagnosed for years. The USPSTF cites a lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders of 26.4% for men and 40.4% for women, although the data used are 10 years old.5 The cited rate of generalized anxiety in pregnancy is 8.5% to 10.5%, and in the postpartum period, 4.4% to 10.8%.6

The data on direct benefits and harms of screening for anxiety in adults through age 64 are sparse. Nevertheless, the USPSTF deemed that screening tests for anxiety have adequate accuracy and that psychological interventions for anxiety result in moderate reduction of anxiety symptoms. Pharmacologic interventions produce a small benefit, although there is a lack of evidence for pharmacotherapy in pregnant and postpartum women. There is even less evidence of benefit for treatment in adults ≥ 65 years of age.1

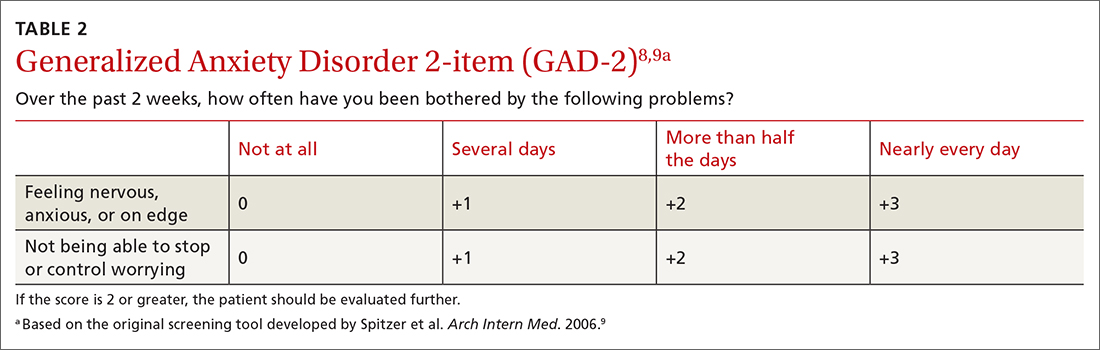

How anxiety screening tests compare

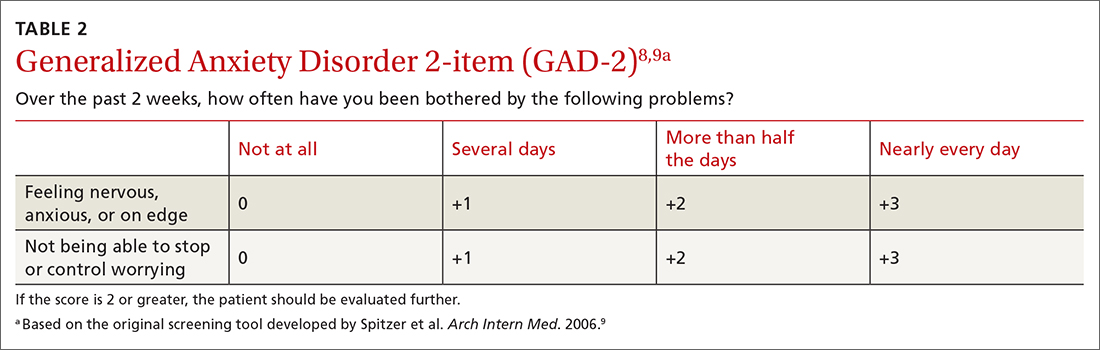

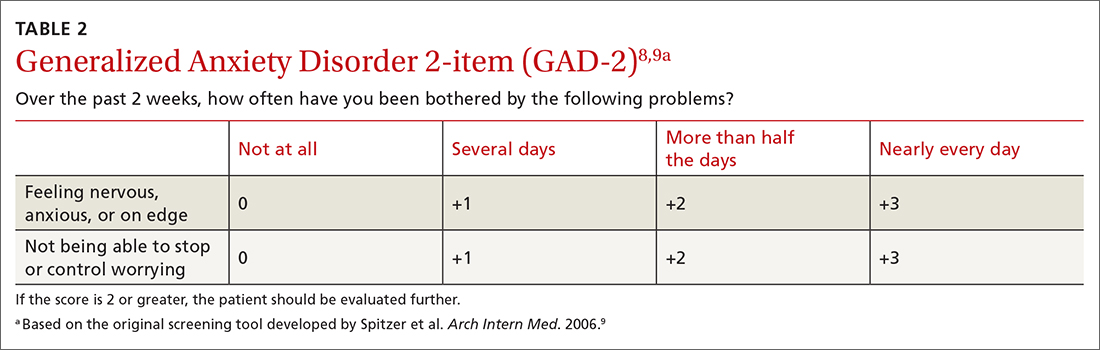

Screening tests for anxiety in adults reviewed by the USPSTF included the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) anxiety subscale.1 The most studied tools are the GAD-2 and GAD-7.

Continue to: The sensitivity and specificity...

The sensitivity and specificity of each test depends on the cutoff used. With the GAD-2, a cutoff of 2 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 68% for detecting generalized anxiety.7 A cutoff of 3 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 86%.7 The GAD-7, using 10 as a cutoff, achieves a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 89%.7 Given the similar performance of the 2 options, the GAD-2 (TABLE 28,9) is probably preferable for use in primary care because of its ease of administration.

The tests evaluated by the USPSTF for anxiety screening in children and adolescents ≥ 8 years of age included the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) and the Patient Health Questionnaire–Adolescent (PHQ-A).3 These tools ask more questions than the adult screening tools do: 41 for the SCARED and 13 for the PHQ-A. The sensitivity of SCARED for generalized anxiety disorder was 64% and the specificity was 63%.10 The sensitivity of the PHQ-A was 50% and the specificity was 98%.10

Various versions of all of these screening tools can be easily located on the internet. Search for them using the acronyms.

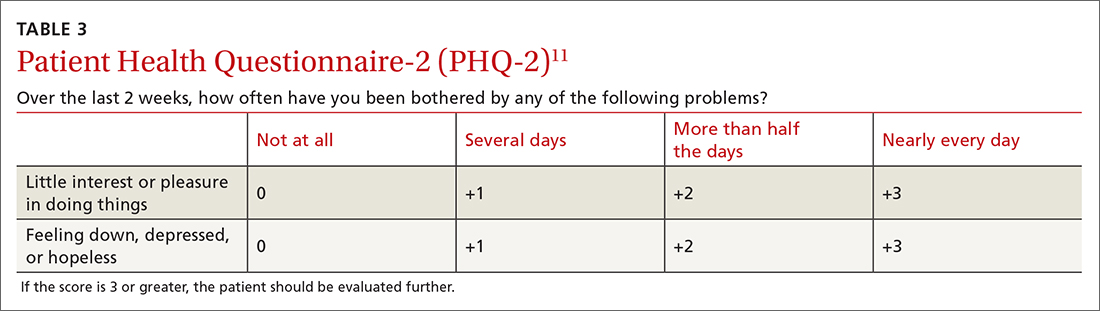

Screening for major depression

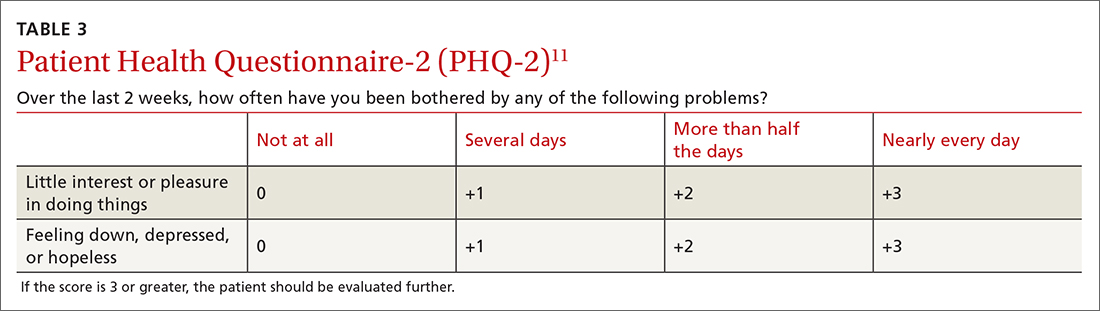

The depression screening tests the USPSTF examined were various versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in older adults, and the EPDS in postpartum and pregnant persons.7

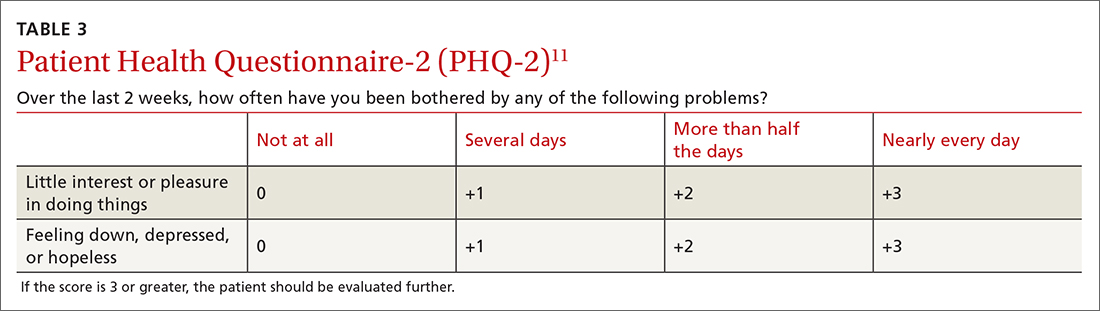

A 2-question version of the PHQ was found to have a sensitivity of 91% with a specificity of 67%. The 9-question PHQ was found to have a similar sensitivity (88%) but better specificity (85%).7 TABLE 311 lists the 2 questions in the PHQ-2 and explains how to score the results.

Continue to: The most commonly...

The most commonly studied screening tool for adolescents is the PHQ-A. Its sensitivity is 73% and specificity is 94%.12

The GAD-2 and PHQ-2 have the same possible answers and scores and can be combined into a 4-question screening tool to assess for anxiety and depression. If an initial screen for anxiety or depression (or both) is positive, further diagnostic testing and follow-up are needed.

Frequency of screening

The USPSTF recognized that limited information on the frequency of screening for both anxiety and depression does not support any recommendation on this matter. It suggested screening everyone once and then basing the need for subsequent screening tests on clinical judgment after considering risk factors and life events, with periodic rescreening of those at high risk. Finally, USPSTF recognized the many challenges to implementing screening tests for mental health conditions in primary care practice, but offered little practical advice on how to do this.

Suicide risk screening

As for the evidence on benefits and harms of screening for suicide risk in all age groups, the USPSTF still regards it as insufficient to make a recommendation. The lack of evidence applies to all aspects of screening, including the accuracy of the various screening tools and the potential benefits and harms of preventive interventions.2,7

Next steps

The recommendations on screening for depression, suicide risk, and anxiety in adults have been published as a draft, and the public comment period will be over by the time of this publication. The USPSTF generally takes 6 to 9 months to consider all the public comments and to publish final recommendations. The final recommendations on these topics for children and adolescents have been published since drafts were made available last April. There were no major changes between the draft and final versions.

1. USPSTF. Screening for anxiety in adults. Draft recommendation statement. Published September 20, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/anxiety-adults-screening

2. USPSTF. Screening for depression and suicide risk in adults. Updated September 14, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-update-summary/screening-depression-suicide-risk-adults

3. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

4. USPSTF. Depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: screening. Final recommendation statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-depression-suicide-risk-children-adolescents

5. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:169-184. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359

6. Misri S, Abizadeh J, Sanders S, et al. Perinatal generalized anxiety disorder: assessment and treatment. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:762-770. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5150

7. O’Connor E, Henninger M, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for depression, anxiety, and suicide risk in adults: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Accessed November 22, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/dpG5pjV5yCew8fXvctFJNK

8. Sapra A, Bhandari P, Sharma S, et al. Using Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and GAD-7 in a primary care setting. Cureus. 2020;12:e8224. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8224

9. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

10. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for anxiety in children and adolescents: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1445-1455. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.16303

11. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire‐2: validity of a two‐item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284‐1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

12. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1543-1556. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.16310

In September 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released 2 sets of draft recommendations on screening for 3 mental health conditions in adults: anxiety, depression, and suicide risk.1,2 These draft recommendations are summarized in TABLE 11-4 along with finalized recommendations on the same topics for children and adolescents, published in October 2022.3,4

The recommendations on depression and suicide risk screening in adults are updates of previous recommendations (2016 for depression and 2014 for suicide risk) with no major changes. Screening for anxiety is a topic addressed for the first time this year for adults and for children and adolescents.1,3

The recommendations are fairly consistent between age groups. A “B” recommendation supports screening for major depression in all patients starting at age 12 years, including during pregnancy and the postpartum period. (See TABLE 1 for grade definitions.) For all age groups, evidence was insufficient to recommend screening for suicide risk. A “B” recommendation was also assigned to screening for anxiety in those ages 8 to 64 years. The USPSTF believes the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation on screening for anxiety among adults ≥ 65 years of age.

The anxiety disorders common to both children and adults included in the USPSTF recommendations are generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, separation anxiety disorder, phobias, selective mutism, and anxiety type not specified. For adults, the USPSTF also includes substance/medication-induced anxiety and anxiety due to other medical conditions.

Adults with anxiety often present with generalized complaints such as sleep disturbance, pain, and other somatic disorders that can remain undiagnosed for years. The USPSTF cites a lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders of 26.4% for men and 40.4% for women, although the data used are 10 years old.5 The cited rate of generalized anxiety in pregnancy is 8.5% to 10.5%, and in the postpartum period, 4.4% to 10.8%.6

The data on direct benefits and harms of screening for anxiety in adults through age 64 are sparse. Nevertheless, the USPSTF deemed that screening tests for anxiety have adequate accuracy and that psychological interventions for anxiety result in moderate reduction of anxiety symptoms. Pharmacologic interventions produce a small benefit, although there is a lack of evidence for pharmacotherapy in pregnant and postpartum women. There is even less evidence of benefit for treatment in adults ≥ 65 years of age.1

How anxiety screening tests compare

Screening tests for anxiety in adults reviewed by the USPSTF included the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) anxiety subscale.1 The most studied tools are the GAD-2 and GAD-7.

Continue to: The sensitivity and specificity...

The sensitivity and specificity of each test depends on the cutoff used. With the GAD-2, a cutoff of 2 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 68% for detecting generalized anxiety.7 A cutoff of 3 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 86%.7 The GAD-7, using 10 as a cutoff, achieves a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 89%.7 Given the similar performance of the 2 options, the GAD-2 (TABLE 28,9) is probably preferable for use in primary care because of its ease of administration.

The tests evaluated by the USPSTF for anxiety screening in children and adolescents ≥ 8 years of age included the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) and the Patient Health Questionnaire–Adolescent (PHQ-A).3 These tools ask more questions than the adult screening tools do: 41 for the SCARED and 13 for the PHQ-A. The sensitivity of SCARED for generalized anxiety disorder was 64% and the specificity was 63%.10 The sensitivity of the PHQ-A was 50% and the specificity was 98%.10

Various versions of all of these screening tools can be easily located on the internet. Search for them using the acronyms.

Screening for major depression

The depression screening tests the USPSTF examined were various versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in older adults, and the EPDS in postpartum and pregnant persons.7

A 2-question version of the PHQ was found to have a sensitivity of 91% with a specificity of 67%. The 9-question PHQ was found to have a similar sensitivity (88%) but better specificity (85%).7 TABLE 311 lists the 2 questions in the PHQ-2 and explains how to score the results.

Continue to: The most commonly...

The most commonly studied screening tool for adolescents is the PHQ-A. Its sensitivity is 73% and specificity is 94%.12

The GAD-2 and PHQ-2 have the same possible answers and scores and can be combined into a 4-question screening tool to assess for anxiety and depression. If an initial screen for anxiety or depression (or both) is positive, further diagnostic testing and follow-up are needed.

Frequency of screening

The USPSTF recognized that limited information on the frequency of screening for both anxiety and depression does not support any recommendation on this matter. It suggested screening everyone once and then basing the need for subsequent screening tests on clinical judgment after considering risk factors and life events, with periodic rescreening of those at high risk. Finally, USPSTF recognized the many challenges to implementing screening tests for mental health conditions in primary care practice, but offered little practical advice on how to do this.

Suicide risk screening

As for the evidence on benefits and harms of screening for suicide risk in all age groups, the USPSTF still regards it as insufficient to make a recommendation. The lack of evidence applies to all aspects of screening, including the accuracy of the various screening tools and the potential benefits and harms of preventive interventions.2,7

Next steps

The recommendations on screening for depression, suicide risk, and anxiety in adults have been published as a draft, and the public comment period will be over by the time of this publication. The USPSTF generally takes 6 to 9 months to consider all the public comments and to publish final recommendations. The final recommendations on these topics for children and adolescents have been published since drafts were made available last April. There were no major changes between the draft and final versions.

In September 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released 2 sets of draft recommendations on screening for 3 mental health conditions in adults: anxiety, depression, and suicide risk.1,2 These draft recommendations are summarized in TABLE 11-4 along with finalized recommendations on the same topics for children and adolescents, published in October 2022.3,4

The recommendations on depression and suicide risk screening in adults are updates of previous recommendations (2016 for depression and 2014 for suicide risk) with no major changes. Screening for anxiety is a topic addressed for the first time this year for adults and for children and adolescents.1,3

The recommendations are fairly consistent between age groups. A “B” recommendation supports screening for major depression in all patients starting at age 12 years, including during pregnancy and the postpartum period. (See TABLE 1 for grade definitions.) For all age groups, evidence was insufficient to recommend screening for suicide risk. A “B” recommendation was also assigned to screening for anxiety in those ages 8 to 64 years. The USPSTF believes the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation on screening for anxiety among adults ≥ 65 years of age.

The anxiety disorders common to both children and adults included in the USPSTF recommendations are generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, separation anxiety disorder, phobias, selective mutism, and anxiety type not specified. For adults, the USPSTF also includes substance/medication-induced anxiety and anxiety due to other medical conditions.

Adults with anxiety often present with generalized complaints such as sleep disturbance, pain, and other somatic disorders that can remain undiagnosed for years. The USPSTF cites a lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders of 26.4% for men and 40.4% for women, although the data used are 10 years old.5 The cited rate of generalized anxiety in pregnancy is 8.5% to 10.5%, and in the postpartum period, 4.4% to 10.8%.6

The data on direct benefits and harms of screening for anxiety in adults through age 64 are sparse. Nevertheless, the USPSTF deemed that screening tests for anxiety have adequate accuracy and that psychological interventions for anxiety result in moderate reduction of anxiety symptoms. Pharmacologic interventions produce a small benefit, although there is a lack of evidence for pharmacotherapy in pregnant and postpartum women. There is even less evidence of benefit for treatment in adults ≥ 65 years of age.1

How anxiety screening tests compare

Screening tests for anxiety in adults reviewed by the USPSTF included the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) anxiety subscale.1 The most studied tools are the GAD-2 and GAD-7.

Continue to: The sensitivity and specificity...

The sensitivity and specificity of each test depends on the cutoff used. With the GAD-2, a cutoff of 2 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 68% for detecting generalized anxiety.7 A cutoff of 3 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 86%.7 The GAD-7, using 10 as a cutoff, achieves a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 89%.7 Given the similar performance of the 2 options, the GAD-2 (TABLE 28,9) is probably preferable for use in primary care because of its ease of administration.

The tests evaluated by the USPSTF for anxiety screening in children and adolescents ≥ 8 years of age included the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) and the Patient Health Questionnaire–Adolescent (PHQ-A).3 These tools ask more questions than the adult screening tools do: 41 for the SCARED and 13 for the PHQ-A. The sensitivity of SCARED for generalized anxiety disorder was 64% and the specificity was 63%.10 The sensitivity of the PHQ-A was 50% and the specificity was 98%.10

Various versions of all of these screening tools can be easily located on the internet. Search for them using the acronyms.

Screening for major depression

The depression screening tests the USPSTF examined were various versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in older adults, and the EPDS in postpartum and pregnant persons.7

A 2-question version of the PHQ was found to have a sensitivity of 91% with a specificity of 67%. The 9-question PHQ was found to have a similar sensitivity (88%) but better specificity (85%).7 TABLE 311 lists the 2 questions in the PHQ-2 and explains how to score the results.

Continue to: The most commonly...

The most commonly studied screening tool for adolescents is the PHQ-A. Its sensitivity is 73% and specificity is 94%.12

The GAD-2 and PHQ-2 have the same possible answers and scores and can be combined into a 4-question screening tool to assess for anxiety and depression. If an initial screen for anxiety or depression (or both) is positive, further diagnostic testing and follow-up are needed.

Frequency of screening

The USPSTF recognized that limited information on the frequency of screening for both anxiety and depression does not support any recommendation on this matter. It suggested screening everyone once and then basing the need for subsequent screening tests on clinical judgment after considering risk factors and life events, with periodic rescreening of those at high risk. Finally, USPSTF recognized the many challenges to implementing screening tests for mental health conditions in primary care practice, but offered little practical advice on how to do this.

Suicide risk screening

As for the evidence on benefits and harms of screening for suicide risk in all age groups, the USPSTF still regards it as insufficient to make a recommendation. The lack of evidence applies to all aspects of screening, including the accuracy of the various screening tools and the potential benefits and harms of preventive interventions.2,7

Next steps

The recommendations on screening for depression, suicide risk, and anxiety in adults have been published as a draft, and the public comment period will be over by the time of this publication. The USPSTF generally takes 6 to 9 months to consider all the public comments and to publish final recommendations. The final recommendations on these topics for children and adolescents have been published since drafts were made available last April. There were no major changes between the draft and final versions.

1. USPSTF. Screening for anxiety in adults. Draft recommendation statement. Published September 20, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/anxiety-adults-screening

2. USPSTF. Screening for depression and suicide risk in adults. Updated September 14, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-update-summary/screening-depression-suicide-risk-adults

3. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

4. USPSTF. Depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: screening. Final recommendation statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-depression-suicide-risk-children-adolescents

5. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:169-184. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359

6. Misri S, Abizadeh J, Sanders S, et al. Perinatal generalized anxiety disorder: assessment and treatment. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:762-770. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5150

7. O’Connor E, Henninger M, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for depression, anxiety, and suicide risk in adults: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Accessed November 22, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/dpG5pjV5yCew8fXvctFJNK

8. Sapra A, Bhandari P, Sharma S, et al. Using Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and GAD-7 in a primary care setting. Cureus. 2020;12:e8224. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8224

9. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

10. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for anxiety in children and adolescents: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1445-1455. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.16303

11. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire‐2: validity of a two‐item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284‐1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

12. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1543-1556. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.16310

1. USPSTF. Screening for anxiety in adults. Draft recommendation statement. Published September 20, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/anxiety-adults-screening

2. USPSTF. Screening for depression and suicide risk in adults. Updated September 14, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-update-summary/screening-depression-suicide-risk-adults

3. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

4. USPSTF. Depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: screening. Final recommendation statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-depression-suicide-risk-children-adolescents

5. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:169-184. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359

6. Misri S, Abizadeh J, Sanders S, et al. Perinatal generalized anxiety disorder: assessment and treatment. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:762-770. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5150

7. O’Connor E, Henninger M, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for depression, anxiety, and suicide risk in adults: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Accessed November 22, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/dpG5pjV5yCew8fXvctFJNK

8. Sapra A, Bhandari P, Sharma S, et al. Using Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and GAD-7 in a primary care setting. Cureus. 2020;12:e8224. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8224

9. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

10. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for anxiety in children and adolescents: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1445-1455. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.16303

11. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire‐2: validity of a two‐item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284‐1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

12. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1543-1556. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.16310

Why you (still) shouldn’t prescribe hormone therapy for disease prevention

On November 1, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published updated recommendations (and a supporting evidence report) for the use of hormone therapy in postmenopausal women for the prevention of chronic medical conditions, such as heart disease, cancer, and osteoporosis.1,2 The USPSTF continues to recommend against the use of either estrogen or combined estrogen plus progesterone for this purpose.

A bit of context. These recommendations apply to asymptomatic postmenopausal women and do not apply to those who are unable to manage menopausal symptoms (eg, hot flashes or vaginal dryness) with other interventions, or to those who have premature or surgically caused menopause.

This update is a reconfirmation of USPSTF’s 2017 recommendations on this topic. These recommendations are consistent with those of multiple other organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Physicians, and the American Heart Association.

A look at the evidence. The evidence report included data from 20 randomized clinical trials and 3 cohort studies that examined the use of oral or transdermal hormone therapy. The most commonly used therapy was oral conjugated equine estrogen 0.625 mg/d, with or without medroxyprogesterone acetate 2.5 mg/d. The strongest evidence is from the Women’s Health Initiative, which included postmenopausal women ages 50 to 79 years and had follow-up of 7.2 years for the estrogen-only trial, 5.6 years for the estrogen plus progestin trial, and a long-term follow-up of up to 20.7 years.2,3

Benefits and harms of hormone therapy. Among postmenopausal women, use of estrogen alone was associated with absolute reduction in risk for fractures (–388 per 10,000 women), diabetes (–134), and breast cancer (–52) and an absolute increase in risk for urinary incontinence (+ 885 per 10,000 women), gallbladder disease (+ 377), stroke (+ 79), and venous thromboembolism (+ 77). Use of estrogen plus progestin was associated with reduced risk for fractures (–230 per 10,000 women), diabetes (–78), and colorectal cancer (–34) and an increased risk for urinary incontinence ( + 562 per 10,000 women), gallbladder disease (+ 260), venous thromboembolism (+ 120), dementia (+ 88), stroke (+ 52), and breast cancer (+ 51).2,3

Lingering questions. The USPSTF felt that the evidence is too limited to answer the following: (1) Are the potential benefits and harms of hormone therapy affected by participants’ age or by the timing of therapy initiation in relation to menopause onset? and (2) Do different types, doses, or delivery modes of hormone therapy affect benefits and harms?1

The bottom line. In asymptomatic, healthy, postmenopausal women, do not prescribe hormone therapy to try to prevent chronic conditions.

1. USPSTF. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal persons: primary prevention of chronic conditions. Final recommendation statement. Published November 1, 2022. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/menopausal-hormone-therapy-preventive-medication

2. USPSTF. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal persons: primary prevention of chronic conditions. Evidence summary. Published November 1, 2022. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/final-evidence-summary28/menopausal-hormone-therapy-preventive-medication

3. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310:1353-1368. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278040

On November 1, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published updated recommendations (and a supporting evidence report) for the use of hormone therapy in postmenopausal women for the prevention of chronic medical conditions, such as heart disease, cancer, and osteoporosis.1,2 The USPSTF continues to recommend against the use of either estrogen or combined estrogen plus progesterone for this purpose.

A bit of context. These recommendations apply to asymptomatic postmenopausal women and do not apply to those who are unable to manage menopausal symptoms (eg, hot flashes or vaginal dryness) with other interventions, or to those who have premature or surgically caused menopause.

This update is a reconfirmation of USPSTF’s 2017 recommendations on this topic. These recommendations are consistent with those of multiple other organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Physicians, and the American Heart Association.

A look at the evidence. The evidence report included data from 20 randomized clinical trials and 3 cohort studies that examined the use of oral or transdermal hormone therapy. The most commonly used therapy was oral conjugated equine estrogen 0.625 mg/d, with or without medroxyprogesterone acetate 2.5 mg/d. The strongest evidence is from the Women’s Health Initiative, which included postmenopausal women ages 50 to 79 years and had follow-up of 7.2 years for the estrogen-only trial, 5.6 years for the estrogen plus progestin trial, and a long-term follow-up of up to 20.7 years.2,3

Benefits and harms of hormone therapy. Among postmenopausal women, use of estrogen alone was associated with absolute reduction in risk for fractures (–388 per 10,000 women), diabetes (–134), and breast cancer (–52) and an absolute increase in risk for urinary incontinence (+ 885 per 10,000 women), gallbladder disease (+ 377), stroke (+ 79), and venous thromboembolism (+ 77). Use of estrogen plus progestin was associated with reduced risk for fractures (–230 per 10,000 women), diabetes (–78), and colorectal cancer (–34) and an increased risk for urinary incontinence ( + 562 per 10,000 women), gallbladder disease (+ 260), venous thromboembolism (+ 120), dementia (+ 88), stroke (+ 52), and breast cancer (+ 51).2,3

Lingering questions. The USPSTF felt that the evidence is too limited to answer the following: (1) Are the potential benefits and harms of hormone therapy affected by participants’ age or by the timing of therapy initiation in relation to menopause onset? and (2) Do different types, doses, or delivery modes of hormone therapy affect benefits and harms?1

The bottom line. In asymptomatic, healthy, postmenopausal women, do not prescribe hormone therapy to try to prevent chronic conditions.

On November 1, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published updated recommendations (and a supporting evidence report) for the use of hormone therapy in postmenopausal women for the prevention of chronic medical conditions, such as heart disease, cancer, and osteoporosis.1,2 The USPSTF continues to recommend against the use of either estrogen or combined estrogen plus progesterone for this purpose.

A bit of context. These recommendations apply to asymptomatic postmenopausal women and do not apply to those who are unable to manage menopausal symptoms (eg, hot flashes or vaginal dryness) with other interventions, or to those who have premature or surgically caused menopause.

This update is a reconfirmation of USPSTF’s 2017 recommendations on this topic. These recommendations are consistent with those of multiple other organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Physicians, and the American Heart Association.

A look at the evidence. The evidence report included data from 20 randomized clinical trials and 3 cohort studies that examined the use of oral or transdermal hormone therapy. The most commonly used therapy was oral conjugated equine estrogen 0.625 mg/d, with or without medroxyprogesterone acetate 2.5 mg/d. The strongest evidence is from the Women’s Health Initiative, which included postmenopausal women ages 50 to 79 years and had follow-up of 7.2 years for the estrogen-only trial, 5.6 years for the estrogen plus progestin trial, and a long-term follow-up of up to 20.7 years.2,3

Benefits and harms of hormone therapy. Among postmenopausal women, use of estrogen alone was associated with absolute reduction in risk for fractures (–388 per 10,000 women), diabetes (–134), and breast cancer (–52) and an absolute increase in risk for urinary incontinence (+ 885 per 10,000 women), gallbladder disease (+ 377), stroke (+ 79), and venous thromboembolism (+ 77). Use of estrogen plus progestin was associated with reduced risk for fractures (–230 per 10,000 women), diabetes (–78), and colorectal cancer (–34) and an increased risk for urinary incontinence ( + 562 per 10,000 women), gallbladder disease (+ 260), venous thromboembolism (+ 120), dementia (+ 88), stroke (+ 52), and breast cancer (+ 51).2,3

Lingering questions. The USPSTF felt that the evidence is too limited to answer the following: (1) Are the potential benefits and harms of hormone therapy affected by participants’ age or by the timing of therapy initiation in relation to menopause onset? and (2) Do different types, doses, or delivery modes of hormone therapy affect benefits and harms?1

The bottom line. In asymptomatic, healthy, postmenopausal women, do not prescribe hormone therapy to try to prevent chronic conditions.

1. USPSTF. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal persons: primary prevention of chronic conditions. Final recommendation statement. Published November 1, 2022. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/menopausal-hormone-therapy-preventive-medication

2. USPSTF. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal persons: primary prevention of chronic conditions. Evidence summary. Published November 1, 2022. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/final-evidence-summary28/menopausal-hormone-therapy-preventive-medication

3. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310:1353-1368. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278040

1. USPSTF. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal persons: primary prevention of chronic conditions. Final recommendation statement. Published November 1, 2022. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/menopausal-hormone-therapy-preventive-medication

2. USPSTF. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal persons: primary prevention of chronic conditions. Evidence summary. Published November 1, 2022. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/final-evidence-summary28/menopausal-hormone-therapy-preventive-medication

3. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310:1353-1368. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278040

Syphilis screening: Who and when

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published updated recommendations on screening for syphilis on September 27.1 The Task Force continues to recommend screening for all adolescents and adults who are at increased risk for infection. (As part of previous recommendations, the USPSTF also advocates screening all pregnant women for syphilis early in their pregnancy to prevent congenital syphilis.2)