User login

The Hospitalist only

New telehealth legislation would provide for testing, expansion

A bipartisan bill introduced in the U.S. Senate in late March 2017 would authorize the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to test expanded telehealth services provided to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Telehealth Innovation and Improvement Act (S.787), currently in the Senate Finance Committee, was introduced by Sen. Gary Peters (D-Mich.) and Sen. Cory Gardner (R-Colo.). A similar bill they introduced in 2015 was never enacted.

However, there are physicians hoping to see this bill or others like it granted consideration. Currently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimburses only for certain telemedicine services provided in rural or underserved geographic areas, but the new bill would apply in suburban and urban areas as well, based on pilot testing of models and evaluating them for cost, quality, and effectiveness. Successful models would be covered by Medicare.

“Medicare has made some provisions for specific rural sites and niche areas, but writ large, there’s no prescribed way for people to just open a telemedicine shop and begin to bill,” said Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM, a member of the SHM Public Policy Committee.

With the exception of telestroke and critical care, “evidence is needed for the type of setting and type of clinical problems addressed by telemedicine. It’s not been tested enough,” added Dr. Flansbaum, who holds a dual appointment in hospital medicine and population health at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Penn. “How does it work for routine inpatient problems and how do hospitalists use it? We haven’t seen data there and that’s where a pilot comes in.”

Dr. Mac believes it inconsistent that, in many circumstances, physicians providing services via telemedicine technology are not reimbursed by Medicare and other payers.

“The expansion and ability to provide care in more unique ways – more specialties and in more environments – has expanded more quickly than the systems of reimbursement for professional fees have and it really is a bit of a hodgepodge now,” he said. “We certainly are pleased that this is getting attention and that we have leaders pushing for this in Congress. We don’t know for sure how the final legislation (on this bill) may look but hopefully there will be some form of this that will come to fruition.”

Whether telemedicine can reduce costs while improving outcomes, or improve outcomes without increasing costs, remains unsettled. A study published in Health Affairs in March 2017 indicates that while telehealth can improve access to care, it results in greater utilization, thereby increasing costs.1

The study relied on claims data for more than 300,000 patients in the California Public Employees’ Retirement System during 2011-2013. It looked at utilization of direct-to-consumer telehealth and spending for acute respiratory illness, one of the most common reasons patients seek telehealth services. While, per episode, telehealth visits cost 50% less than did an outpatient visit and less than 5% of an emergency department visit, annual spending per individual for acute respiratory illness went up $45 because, as the authors estimated, 88% of direct-to-consumer telehealth visits represented new utilization.

Whether this would be the case for hospitalist patients remains to be tested.

“It gets back to whether or not you’re adding a necessary service or substituting a less expensive one for a more expensive one,” said Dr. Flansbaum. “Are physicians providing a needed service or adding unnecessary visits to the system?”

Jayne Lee, MD, has been a hospitalist with Eagle for nearly a decade. Before making the transition from an in-hospital physician to one treating patients from behind a robot – with assistance at the point of service from a nurse – she was working 10 shifts in a row at her home in the United States before traveling to her home in Paris. Dr. Mac offered her the opportunity to practice full time as a telehospitalist from overseas. Today, she is also the company’s chief medical officer and estimates she’s had more than 7,000 patient encounters using telemedicine technology.

Dr. Lee is licensed in multiple states – a barrier that plagues many would-be telehealth providers, but which Eagle has solved with its licensing and credentialing staff – and because she is often providing services at night to urban and rural areas, she sees a broad range of patients.

“We see things from coronary artery disease, COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] exacerbations, and diabetes-related conditions to drug overdoses and alcohol abuse,” she said. “I enjoy seeing the variety of patients I encounter every night.”

Dr. Lee has to navigate each health system’s electronic medical records and triage systems but, she says, patient care has remained the same. And she’s providing services for hospitals that may not have another hospitalist to assign.

“Our practices keep growing, a sign that hospitals are needing our services now more than ever, given that there is a physician shortage and given the financial constraints we’re seeing in the healthcare system.” she said.

References

1. Ashwood JS, Mehrota A, Cowling D, et al. Direct-to-consumer telehealth may increase access to care but does not decrease spending. Health Affairs. 2017; 36(3):485-491. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1130.

A bipartisan bill introduced in the U.S. Senate in late March 2017 would authorize the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to test expanded telehealth services provided to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Telehealth Innovation and Improvement Act (S.787), currently in the Senate Finance Committee, was introduced by Sen. Gary Peters (D-Mich.) and Sen. Cory Gardner (R-Colo.). A similar bill they introduced in 2015 was never enacted.

However, there are physicians hoping to see this bill or others like it granted consideration. Currently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimburses only for certain telemedicine services provided in rural or underserved geographic areas, but the new bill would apply in suburban and urban areas as well, based on pilot testing of models and evaluating them for cost, quality, and effectiveness. Successful models would be covered by Medicare.

“Medicare has made some provisions for specific rural sites and niche areas, but writ large, there’s no prescribed way for people to just open a telemedicine shop and begin to bill,” said Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM, a member of the SHM Public Policy Committee.

With the exception of telestroke and critical care, “evidence is needed for the type of setting and type of clinical problems addressed by telemedicine. It’s not been tested enough,” added Dr. Flansbaum, who holds a dual appointment in hospital medicine and population health at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Penn. “How does it work for routine inpatient problems and how do hospitalists use it? We haven’t seen data there and that’s where a pilot comes in.”

Dr. Mac believes it inconsistent that, in many circumstances, physicians providing services via telemedicine technology are not reimbursed by Medicare and other payers.

“The expansion and ability to provide care in more unique ways – more specialties and in more environments – has expanded more quickly than the systems of reimbursement for professional fees have and it really is a bit of a hodgepodge now,” he said. “We certainly are pleased that this is getting attention and that we have leaders pushing for this in Congress. We don’t know for sure how the final legislation (on this bill) may look but hopefully there will be some form of this that will come to fruition.”

Whether telemedicine can reduce costs while improving outcomes, or improve outcomes without increasing costs, remains unsettled. A study published in Health Affairs in March 2017 indicates that while telehealth can improve access to care, it results in greater utilization, thereby increasing costs.1

The study relied on claims data for more than 300,000 patients in the California Public Employees’ Retirement System during 2011-2013. It looked at utilization of direct-to-consumer telehealth and spending for acute respiratory illness, one of the most common reasons patients seek telehealth services. While, per episode, telehealth visits cost 50% less than did an outpatient visit and less than 5% of an emergency department visit, annual spending per individual for acute respiratory illness went up $45 because, as the authors estimated, 88% of direct-to-consumer telehealth visits represented new utilization.

Whether this would be the case for hospitalist patients remains to be tested.

“It gets back to whether or not you’re adding a necessary service or substituting a less expensive one for a more expensive one,” said Dr. Flansbaum. “Are physicians providing a needed service or adding unnecessary visits to the system?”

Jayne Lee, MD, has been a hospitalist with Eagle for nearly a decade. Before making the transition from an in-hospital physician to one treating patients from behind a robot – with assistance at the point of service from a nurse – she was working 10 shifts in a row at her home in the United States before traveling to her home in Paris. Dr. Mac offered her the opportunity to practice full time as a telehospitalist from overseas. Today, she is also the company’s chief medical officer and estimates she’s had more than 7,000 patient encounters using telemedicine technology.

Dr. Lee is licensed in multiple states – a barrier that plagues many would-be telehealth providers, but which Eagle has solved with its licensing and credentialing staff – and because she is often providing services at night to urban and rural areas, she sees a broad range of patients.

“We see things from coronary artery disease, COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] exacerbations, and diabetes-related conditions to drug overdoses and alcohol abuse,” she said. “I enjoy seeing the variety of patients I encounter every night.”

Dr. Lee has to navigate each health system’s electronic medical records and triage systems but, she says, patient care has remained the same. And she’s providing services for hospitals that may not have another hospitalist to assign.

“Our practices keep growing, a sign that hospitals are needing our services now more than ever, given that there is a physician shortage and given the financial constraints we’re seeing in the healthcare system.” she said.

References

1. Ashwood JS, Mehrota A, Cowling D, et al. Direct-to-consumer telehealth may increase access to care but does not decrease spending. Health Affairs. 2017; 36(3):485-491. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1130.

A bipartisan bill introduced in the U.S. Senate in late March 2017 would authorize the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to test expanded telehealth services provided to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Telehealth Innovation and Improvement Act (S.787), currently in the Senate Finance Committee, was introduced by Sen. Gary Peters (D-Mich.) and Sen. Cory Gardner (R-Colo.). A similar bill they introduced in 2015 was never enacted.

However, there are physicians hoping to see this bill or others like it granted consideration. Currently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimburses only for certain telemedicine services provided in rural or underserved geographic areas, but the new bill would apply in suburban and urban areas as well, based on pilot testing of models and evaluating them for cost, quality, and effectiveness. Successful models would be covered by Medicare.

“Medicare has made some provisions for specific rural sites and niche areas, but writ large, there’s no prescribed way for people to just open a telemedicine shop and begin to bill,” said Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM, a member of the SHM Public Policy Committee.

With the exception of telestroke and critical care, “evidence is needed for the type of setting and type of clinical problems addressed by telemedicine. It’s not been tested enough,” added Dr. Flansbaum, who holds a dual appointment in hospital medicine and population health at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Penn. “How does it work for routine inpatient problems and how do hospitalists use it? We haven’t seen data there and that’s where a pilot comes in.”

Dr. Mac believes it inconsistent that, in many circumstances, physicians providing services via telemedicine technology are not reimbursed by Medicare and other payers.

“The expansion and ability to provide care in more unique ways – more specialties and in more environments – has expanded more quickly than the systems of reimbursement for professional fees have and it really is a bit of a hodgepodge now,” he said. “We certainly are pleased that this is getting attention and that we have leaders pushing for this in Congress. We don’t know for sure how the final legislation (on this bill) may look but hopefully there will be some form of this that will come to fruition.”

Whether telemedicine can reduce costs while improving outcomes, or improve outcomes without increasing costs, remains unsettled. A study published in Health Affairs in March 2017 indicates that while telehealth can improve access to care, it results in greater utilization, thereby increasing costs.1

The study relied on claims data for more than 300,000 patients in the California Public Employees’ Retirement System during 2011-2013. It looked at utilization of direct-to-consumer telehealth and spending for acute respiratory illness, one of the most common reasons patients seek telehealth services. While, per episode, telehealth visits cost 50% less than did an outpatient visit and less than 5% of an emergency department visit, annual spending per individual for acute respiratory illness went up $45 because, as the authors estimated, 88% of direct-to-consumer telehealth visits represented new utilization.

Whether this would be the case for hospitalist patients remains to be tested.

“It gets back to whether or not you’re adding a necessary service or substituting a less expensive one for a more expensive one,” said Dr. Flansbaum. “Are physicians providing a needed service or adding unnecessary visits to the system?”

Jayne Lee, MD, has been a hospitalist with Eagle for nearly a decade. Before making the transition from an in-hospital physician to one treating patients from behind a robot – with assistance at the point of service from a nurse – she was working 10 shifts in a row at her home in the United States before traveling to her home in Paris. Dr. Mac offered her the opportunity to practice full time as a telehospitalist from overseas. Today, she is also the company’s chief medical officer and estimates she’s had more than 7,000 patient encounters using telemedicine technology.

Dr. Lee is licensed in multiple states – a barrier that plagues many would-be telehealth providers, but which Eagle has solved with its licensing and credentialing staff – and because she is often providing services at night to urban and rural areas, she sees a broad range of patients.

“We see things from coronary artery disease, COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] exacerbations, and diabetes-related conditions to drug overdoses and alcohol abuse,” she said. “I enjoy seeing the variety of patients I encounter every night.”

Dr. Lee has to navigate each health system’s electronic medical records and triage systems but, she says, patient care has remained the same. And she’s providing services for hospitals that may not have another hospitalist to assign.

“Our practices keep growing, a sign that hospitals are needing our services now more than ever, given that there is a physician shortage and given the financial constraints we’re seeing in the healthcare system.” she said.

References

1. Ashwood JS, Mehrota A, Cowling D, et al. Direct-to-consumer telehealth may increase access to care but does not decrease spending. Health Affairs. 2017; 36(3):485-491. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1130.

Study: No increased mortality with ACA-prompted readmission declines

Concerns that efforts to reduce 30-day hospital readmission rates under the Affordable Care Act’s Hospital Readmission Reduction Program might lead to unintended increases in mortality rates appear to be unfounded, according to a review of more than 6.7 million hospitalizations for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia between 2008 and 2014.

In fact, reductions in 30-day readmission rates among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries are weakly but significantly correlated with reductions in hospital 30-day mortality rates after discharge, according to Kumar Dharmarajan, MD, of Yale New Haven (Conn.) Health, and colleagues (JAMA 2017 Jul 18;318[3]:270-8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8444).

From 2008 to 2014, the RARRs declined in aggregate across hospitals (–0.053% for heart failure, –0.044% for acute MI, and –0.033% for pneumonia).

“In contrast, monthly aggregate trends across hospitals in 30-day risk-adjusted mortality rates after discharge varied by admitting condition” the investigators said.

For heart failure, acute MI, and pneumonia, there was an increase of 0.008%, a decrease of 0.003%, and an increase of 0.001%, respectively, they said. However, paired monthly trends in 30-day RARRs and 30-day RAMRs after discharge “identified concomitant reduction in readmission and mortality rates within hospitals.”

Correlation coefficients of the paired monthly trends for heart failure, acute MI, and pneumonia in 2008-2014 were 0.066, 0.067, and 0.108, respectively.

“Paired trends in hospital 30-day risk-adjusted readmission rates and both 90-day risk-adjusted mortality rates after discharge and 90-day risk-adjusted mortality rates after the admission date also identified concomitant reductions in readmission and mortality rates within hospitals,” the authors wrote.

The findings “do not support increasing postdischarge mortality related to reducing hospital readmissions,” they concluded.

The authors work under contract with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop and maintain performance measures. Dr. Dharmarajan reported serving as a consultant and scientific advisory board member for Clover Health at the time this research was performed. He is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the American Federation for Aging Research, and the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center.

The findings by Dharmarajan and colleagues are “certainly good news,” Karen E. Joynt Maddox, MD, wrote in an editorial.

The study provides support for strategies that hospitals are using to reduce readmissions, and also underscores the importance of evaluating unintended consequences of policy changes such as the Affordable Care Act’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), she said (JAMA. 2017 Jul 18;318[3]:243-4).

The study did not address the possibility that attention to reducing readmissions has taken priority over reducing mortality, which could have the unintended consequence of slowing improvements in mortality, she noted, suggesting that for this and other reasons it may be “time to reexamine and reengineer the HRRP to avoid unintended consequences and to ensure that its incentives are fully aligned with the ultimate goal of improving the health outcomes of patients.

“Only with full knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of a particular policy decision can policy makers and advocates work to craft statutes and rules that maximize benefits while minimizing harms,” she wrote.

Dr. Joynt Maddox is with Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. She is supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The findings by Dharmarajan and colleagues are “certainly good news,” Karen E. Joynt Maddox, MD, wrote in an editorial.

The study provides support for strategies that hospitals are using to reduce readmissions, and also underscores the importance of evaluating unintended consequences of policy changes such as the Affordable Care Act’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), she said (JAMA. 2017 Jul 18;318[3]:243-4).

The study did not address the possibility that attention to reducing readmissions has taken priority over reducing mortality, which could have the unintended consequence of slowing improvements in mortality, she noted, suggesting that for this and other reasons it may be “time to reexamine and reengineer the HRRP to avoid unintended consequences and to ensure that its incentives are fully aligned with the ultimate goal of improving the health outcomes of patients.

“Only with full knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of a particular policy decision can policy makers and advocates work to craft statutes and rules that maximize benefits while minimizing harms,” she wrote.

Dr. Joynt Maddox is with Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. She is supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The findings by Dharmarajan and colleagues are “certainly good news,” Karen E. Joynt Maddox, MD, wrote in an editorial.

The study provides support for strategies that hospitals are using to reduce readmissions, and also underscores the importance of evaluating unintended consequences of policy changes such as the Affordable Care Act’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), she said (JAMA. 2017 Jul 18;318[3]:243-4).

The study did not address the possibility that attention to reducing readmissions has taken priority over reducing mortality, which could have the unintended consequence of slowing improvements in mortality, she noted, suggesting that for this and other reasons it may be “time to reexamine and reengineer the HRRP to avoid unintended consequences and to ensure that its incentives are fully aligned with the ultimate goal of improving the health outcomes of patients.

“Only with full knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of a particular policy decision can policy makers and advocates work to craft statutes and rules that maximize benefits while minimizing harms,” she wrote.

Dr. Joynt Maddox is with Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. She is supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Concerns that efforts to reduce 30-day hospital readmission rates under the Affordable Care Act’s Hospital Readmission Reduction Program might lead to unintended increases in mortality rates appear to be unfounded, according to a review of more than 6.7 million hospitalizations for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia between 2008 and 2014.

In fact, reductions in 30-day readmission rates among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries are weakly but significantly correlated with reductions in hospital 30-day mortality rates after discharge, according to Kumar Dharmarajan, MD, of Yale New Haven (Conn.) Health, and colleagues (JAMA 2017 Jul 18;318[3]:270-8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8444).

From 2008 to 2014, the RARRs declined in aggregate across hospitals (–0.053% for heart failure, –0.044% for acute MI, and –0.033% for pneumonia).

“In contrast, monthly aggregate trends across hospitals in 30-day risk-adjusted mortality rates after discharge varied by admitting condition” the investigators said.

For heart failure, acute MI, and pneumonia, there was an increase of 0.008%, a decrease of 0.003%, and an increase of 0.001%, respectively, they said. However, paired monthly trends in 30-day RARRs and 30-day RAMRs after discharge “identified concomitant reduction in readmission and mortality rates within hospitals.”

Correlation coefficients of the paired monthly trends for heart failure, acute MI, and pneumonia in 2008-2014 were 0.066, 0.067, and 0.108, respectively.

“Paired trends in hospital 30-day risk-adjusted readmission rates and both 90-day risk-adjusted mortality rates after discharge and 90-day risk-adjusted mortality rates after the admission date also identified concomitant reductions in readmission and mortality rates within hospitals,” the authors wrote.

The findings “do not support increasing postdischarge mortality related to reducing hospital readmissions,” they concluded.

The authors work under contract with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop and maintain performance measures. Dr. Dharmarajan reported serving as a consultant and scientific advisory board member for Clover Health at the time this research was performed. He is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the American Federation for Aging Research, and the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center.

Concerns that efforts to reduce 30-day hospital readmission rates under the Affordable Care Act’s Hospital Readmission Reduction Program might lead to unintended increases in mortality rates appear to be unfounded, according to a review of more than 6.7 million hospitalizations for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia between 2008 and 2014.

In fact, reductions in 30-day readmission rates among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries are weakly but significantly correlated with reductions in hospital 30-day mortality rates after discharge, according to Kumar Dharmarajan, MD, of Yale New Haven (Conn.) Health, and colleagues (JAMA 2017 Jul 18;318[3]:270-8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8444).

From 2008 to 2014, the RARRs declined in aggregate across hospitals (–0.053% for heart failure, –0.044% for acute MI, and –0.033% for pneumonia).

“In contrast, monthly aggregate trends across hospitals in 30-day risk-adjusted mortality rates after discharge varied by admitting condition” the investigators said.

For heart failure, acute MI, and pneumonia, there was an increase of 0.008%, a decrease of 0.003%, and an increase of 0.001%, respectively, they said. However, paired monthly trends in 30-day RARRs and 30-day RAMRs after discharge “identified concomitant reduction in readmission and mortality rates within hospitals.”

Correlation coefficients of the paired monthly trends for heart failure, acute MI, and pneumonia in 2008-2014 were 0.066, 0.067, and 0.108, respectively.

“Paired trends in hospital 30-day risk-adjusted readmission rates and both 90-day risk-adjusted mortality rates after discharge and 90-day risk-adjusted mortality rates after the admission date also identified concomitant reductions in readmission and mortality rates within hospitals,” the authors wrote.

The findings “do not support increasing postdischarge mortality related to reducing hospital readmissions,” they concluded.

The authors work under contract with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop and maintain performance measures. Dr. Dharmarajan reported serving as a consultant and scientific advisory board member for Clover Health at the time this research was performed. He is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the American Federation for Aging Research, and the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Correlation coefficients of the paired monthly trends for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia in 2008-2014 were 0.066, 0.067, and 0.108, respectively.

Data source: A retrospective review of more than 6.7 million hospitalized Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries.

Disclosures: The authors work under contract with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop and maintain performance measures. Dr. Dharmarajan reported serving as a consultant and scientific advisory board member for Clover Health at the time this research was performed. He is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the American Federation for Aging Research, and the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center.

The role of NPs and PAs in hospital medicine programs

Background and growth

Hospitalist nurse practitioner (NP) and physician assistant (PA) providers have been a growing and evolving part of the inpatient medical workforce, seemingly since the inception of hospital medicine. Given the growth of these disciplines within hospital medicine, at this juncture it is helpful to look at this journey, to see what roles these providers have been serving, and to consider newer and novel trends in how NPs and PAs are being weaved into hospital medicine programs.

The drivers for growth in this provider population are not unlike those of physician hospitalists. The same milieu that provided inroads for physicians in hospital-based care have led the way for increased use of NP/PA providers. An aging physician workforce, residency work hour reforms, increasing complexity of patients and systems on the inpatient side, and the recognition that caring for inpatients is a specialty vastly different from the role of internist in primary care have all impacted the numbers of NPs and PAs in this arena.

• 2007 Today’s Hospitalist article: “Midlevels make a rocky entrance into hospital medicine”1

• 2009 ACP Hospitalist article: “When hiring midlevels, proceed with caution”2

These titles reflect the uncertainty at the time in how best to utilize NP/PA providers in hospital medicine (as well as an unfashionable vocabulary). The numbers at the time tell a similar story. In the Society of Hospital Medicine survey in 2007-2008, about 29% and 21% of hospital medicine practices utilized NPs and PAs, respectively. However, by 2014 about 50% of Veterans Affairs inpatient medical services deployed NP/PA providers, and most recent data from the Society of Hospital Medicine reveal that about 63% of groups use these advanced practice providers (APPs), with higher numbers in pediatric programs. Clearly there is evolving growth and enthusiasm for NP/PAs in hospital medicine.

Program models

Determining how best to use NP/PAs in hospital medicine programs has had a similar evolution. Reviewing past articles addressing these issues, one can see that there has been clear migration; initially NP/PAs were primarily hired to assist with late-afternoon admission surges, with about 60% of the APP workload being utilized to admit in 2007. Their role has continued to grow and change, much as hospitalist practices have; current program models consist of a few major types, with some novel models coming to the fore.

Another model is use of an NP/PA in an observation unit or with lower acuity observation patients. The majority of the management of the patients is completed and billed by the APP, with the physician available for backup. This hits the “sweet spot,” utilizing the right provider with the right skill set for the right patient. The program has to account for some reimbursement or compensation for the physician oversight time, but it is a very efficient use of APPs.

The third major deployment of APPs is with admissions. Many groups use APPs to admit into the late afternoon and evening, getting patients “tucked in,” including starting diagnostic work-ups and treatment plans. The physician hospitalist then evaluates the patient the next day and often bills for the admission. This model works in situations where the patient work-up is dependent on lab testing, imaging, or other diagnostic testing to understand and plan for the “arc” of the hospitalization; or in situations where the diagnosis is clear, but the patient needs time with treatment to determine response. The downside of this model is long-term job satisfaction for the APP (although some programs have them rotate through such a model at intervals).

Another area where APPs have made strong inroads is that of comanagement services. The NP or PA develops a long-term relationship with a surgical comanagement team, and is often highly engaged and extremely appreciated for managing chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. This can be a very satisfying model for both teams. The NP/PA usually bills independently for these encounters.

APPS are also used in cross coverage and triage roles, allowing the day teams to focus on their primary patients. In a triage role, they can interface with the emergency department, providing a semi-neutral “mediator” for patient disposition.

On the more novel end of the spectrum, there is growth in more independent roles for APP hospitalists. Some groups are having success at using the paired rounding or dyad model, but having the physician see the patient every third day. This is most successful where there is strong onboarding and deep clarity for when to contact the backup physician. There are some data to support the effectiveness of this model, most recently in the Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.3

Critical access hospitals are also having success in deploying APPs in a very independent role, staffing these hospitals at night. Smaller, rural hospitals with aging medical staff have learned to maximize the scope of practice of their APPs to remain viable and provide care for inpatients. This can be a very successful model for APPs working at the maximum scope of their practice. In addition, the use of telemedicine has been implemented to allow for remote physician backup. This may be a rapidly growing arm to hospital medicine practices in the future.

Ongoing barriers

There are many barriers to maximizing the scope of practice and efficiency of APPs in hospital medicine. They range from the “macro” to the “micro.”

On the larger stage, Medicare requires that home care orders be signed by an attending physician, which can be inefficient and difficult to accomplish. Other payers may have somewhat arcane statutes that limit billing practices, and state practice limitations vary widely. Although 22 states now allow for independent practice for NPs, other states may have a very restrictive practice environment that can impede creative care delivery models. But regardless of how liberal a practice the state allows, a hospital’s medical bylaws can still restrict the day-to-day practice of APPs. And those restrictive bylaws are emblematic of a more constant and corporeal barrier to APP practice, that of medical staff culture.

If there are physicians on the staff who fear that utilization of NP/PA providers will lead to a decay in the quality of care, or who feel threatened by the use of APPs, that can create a local stopgap to maximizing utilization of APPs. In addition, hospitalist physicians and leaders may lack knowledge or experience in APP practice. APPs take more time to successfully onboard than physicians; without clear expectations or road maps to accomplish this onboarding, leaders may feel that APP integration doesn’t work. And one bad experience can create long-term barriers for future practices.

Other barriers are the lack of standardized rigor and vigor in graduate education programs (in both educational and clinical experiences). This results in variation in the quality of NP/PA providers at graduation. Knowledge gaps may be perceived as incompetence, rather than just a lack of experience. There is a certificate for added qualification in hospital medicine for PA providers (which includes a specialty exam), and there is an acute care focus for NPs in training; however, there is no standardized licensure to ensure hospital medicine competency, creating a quagmire for hospitalist leaders who desire demonstrable competence of these providers.

Another barrier for some programs is financial; physicians may not want to give up their RVUs to an NP/PA provider. This can really inhibit a more independent role for the APP. It is important that financial incentives align with all members of the practice working at maximum scope.

Summary and future

In summary, the role of PA/NP in hospital medicine has continued to grow and evolve, to meet the needs of the industry. This includes an increase in the scope and independence of APPs, including the use of telehealth for required oversight. As a specialty, it is imperative that we continue to research APP model effectiveness, embrace innovative delivery models, and support effective onboarding and career development opportunities for our NP/PA providers.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Ms. Cardin is vice president, Advanced Practice Providers, at Sound Physicians, and is a member of SHM’s Board of Directors.

References

1. “Midlevels make a rocky entrance into hospital medicine,” by Bonnie Darves, Today’s Hospitalist, January 2007.

2. “When hiring midlevels, proceed with caution,” by Jessica Berthold, ACP Hospitalist, April 2009.

3. “A Comparison of Conventional and Expanded Physician Assistant Hospitalist Staffing Models at a Community Hospital,” J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2016 Oct 1;23[10]:455-61.

Background and growth

Hospitalist nurse practitioner (NP) and physician assistant (PA) providers have been a growing and evolving part of the inpatient medical workforce, seemingly since the inception of hospital medicine. Given the growth of these disciplines within hospital medicine, at this juncture it is helpful to look at this journey, to see what roles these providers have been serving, and to consider newer and novel trends in how NPs and PAs are being weaved into hospital medicine programs.

The drivers for growth in this provider population are not unlike those of physician hospitalists. The same milieu that provided inroads for physicians in hospital-based care have led the way for increased use of NP/PA providers. An aging physician workforce, residency work hour reforms, increasing complexity of patients and systems on the inpatient side, and the recognition that caring for inpatients is a specialty vastly different from the role of internist in primary care have all impacted the numbers of NPs and PAs in this arena.

• 2007 Today’s Hospitalist article: “Midlevels make a rocky entrance into hospital medicine”1

• 2009 ACP Hospitalist article: “When hiring midlevels, proceed with caution”2

These titles reflect the uncertainty at the time in how best to utilize NP/PA providers in hospital medicine (as well as an unfashionable vocabulary). The numbers at the time tell a similar story. In the Society of Hospital Medicine survey in 2007-2008, about 29% and 21% of hospital medicine practices utilized NPs and PAs, respectively. However, by 2014 about 50% of Veterans Affairs inpatient medical services deployed NP/PA providers, and most recent data from the Society of Hospital Medicine reveal that about 63% of groups use these advanced practice providers (APPs), with higher numbers in pediatric programs. Clearly there is evolving growth and enthusiasm for NP/PAs in hospital medicine.

Program models

Determining how best to use NP/PAs in hospital medicine programs has had a similar evolution. Reviewing past articles addressing these issues, one can see that there has been clear migration; initially NP/PAs were primarily hired to assist with late-afternoon admission surges, with about 60% of the APP workload being utilized to admit in 2007. Their role has continued to grow and change, much as hospitalist practices have; current program models consist of a few major types, with some novel models coming to the fore.

Another model is use of an NP/PA in an observation unit or with lower acuity observation patients. The majority of the management of the patients is completed and billed by the APP, with the physician available for backup. This hits the “sweet spot,” utilizing the right provider with the right skill set for the right patient. The program has to account for some reimbursement or compensation for the physician oversight time, but it is a very efficient use of APPs.

The third major deployment of APPs is with admissions. Many groups use APPs to admit into the late afternoon and evening, getting patients “tucked in,” including starting diagnostic work-ups and treatment plans. The physician hospitalist then evaluates the patient the next day and often bills for the admission. This model works in situations where the patient work-up is dependent on lab testing, imaging, or other diagnostic testing to understand and plan for the “arc” of the hospitalization; or in situations where the diagnosis is clear, but the patient needs time with treatment to determine response. The downside of this model is long-term job satisfaction for the APP (although some programs have them rotate through such a model at intervals).

Another area where APPs have made strong inroads is that of comanagement services. The NP or PA develops a long-term relationship with a surgical comanagement team, and is often highly engaged and extremely appreciated for managing chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. This can be a very satisfying model for both teams. The NP/PA usually bills independently for these encounters.

APPS are also used in cross coverage and triage roles, allowing the day teams to focus on their primary patients. In a triage role, they can interface with the emergency department, providing a semi-neutral “mediator” for patient disposition.

On the more novel end of the spectrum, there is growth in more independent roles for APP hospitalists. Some groups are having success at using the paired rounding or dyad model, but having the physician see the patient every third day. This is most successful where there is strong onboarding and deep clarity for when to contact the backup physician. There are some data to support the effectiveness of this model, most recently in the Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.3

Critical access hospitals are also having success in deploying APPs in a very independent role, staffing these hospitals at night. Smaller, rural hospitals with aging medical staff have learned to maximize the scope of practice of their APPs to remain viable and provide care for inpatients. This can be a very successful model for APPs working at the maximum scope of their practice. In addition, the use of telemedicine has been implemented to allow for remote physician backup. This may be a rapidly growing arm to hospital medicine practices in the future.

Ongoing barriers

There are many barriers to maximizing the scope of practice and efficiency of APPs in hospital medicine. They range from the “macro” to the “micro.”

On the larger stage, Medicare requires that home care orders be signed by an attending physician, which can be inefficient and difficult to accomplish. Other payers may have somewhat arcane statutes that limit billing practices, and state practice limitations vary widely. Although 22 states now allow for independent practice for NPs, other states may have a very restrictive practice environment that can impede creative care delivery models. But regardless of how liberal a practice the state allows, a hospital’s medical bylaws can still restrict the day-to-day practice of APPs. And those restrictive bylaws are emblematic of a more constant and corporeal barrier to APP practice, that of medical staff culture.

If there are physicians on the staff who fear that utilization of NP/PA providers will lead to a decay in the quality of care, or who feel threatened by the use of APPs, that can create a local stopgap to maximizing utilization of APPs. In addition, hospitalist physicians and leaders may lack knowledge or experience in APP practice. APPs take more time to successfully onboard than physicians; without clear expectations or road maps to accomplish this onboarding, leaders may feel that APP integration doesn’t work. And one bad experience can create long-term barriers for future practices.

Other barriers are the lack of standardized rigor and vigor in graduate education programs (in both educational and clinical experiences). This results in variation in the quality of NP/PA providers at graduation. Knowledge gaps may be perceived as incompetence, rather than just a lack of experience. There is a certificate for added qualification in hospital medicine for PA providers (which includes a specialty exam), and there is an acute care focus for NPs in training; however, there is no standardized licensure to ensure hospital medicine competency, creating a quagmire for hospitalist leaders who desire demonstrable competence of these providers.

Another barrier for some programs is financial; physicians may not want to give up their RVUs to an NP/PA provider. This can really inhibit a more independent role for the APP. It is important that financial incentives align with all members of the practice working at maximum scope.

Summary and future

In summary, the role of PA/NP in hospital medicine has continued to grow and evolve, to meet the needs of the industry. This includes an increase in the scope and independence of APPs, including the use of telehealth for required oversight. As a specialty, it is imperative that we continue to research APP model effectiveness, embrace innovative delivery models, and support effective onboarding and career development opportunities for our NP/PA providers.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Ms. Cardin is vice president, Advanced Practice Providers, at Sound Physicians, and is a member of SHM’s Board of Directors.

References

1. “Midlevels make a rocky entrance into hospital medicine,” by Bonnie Darves, Today’s Hospitalist, January 2007.

2. “When hiring midlevels, proceed with caution,” by Jessica Berthold, ACP Hospitalist, April 2009.

3. “A Comparison of Conventional and Expanded Physician Assistant Hospitalist Staffing Models at a Community Hospital,” J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2016 Oct 1;23[10]:455-61.

Background and growth

Hospitalist nurse practitioner (NP) and physician assistant (PA) providers have been a growing and evolving part of the inpatient medical workforce, seemingly since the inception of hospital medicine. Given the growth of these disciplines within hospital medicine, at this juncture it is helpful to look at this journey, to see what roles these providers have been serving, and to consider newer and novel trends in how NPs and PAs are being weaved into hospital medicine programs.

The drivers for growth in this provider population are not unlike those of physician hospitalists. The same milieu that provided inroads for physicians in hospital-based care have led the way for increased use of NP/PA providers. An aging physician workforce, residency work hour reforms, increasing complexity of patients and systems on the inpatient side, and the recognition that caring for inpatients is a specialty vastly different from the role of internist in primary care have all impacted the numbers of NPs and PAs in this arena.

• 2007 Today’s Hospitalist article: “Midlevels make a rocky entrance into hospital medicine”1

• 2009 ACP Hospitalist article: “When hiring midlevels, proceed with caution”2

These titles reflect the uncertainty at the time in how best to utilize NP/PA providers in hospital medicine (as well as an unfashionable vocabulary). The numbers at the time tell a similar story. In the Society of Hospital Medicine survey in 2007-2008, about 29% and 21% of hospital medicine practices utilized NPs and PAs, respectively. However, by 2014 about 50% of Veterans Affairs inpatient medical services deployed NP/PA providers, and most recent data from the Society of Hospital Medicine reveal that about 63% of groups use these advanced practice providers (APPs), with higher numbers in pediatric programs. Clearly there is evolving growth and enthusiasm for NP/PAs in hospital medicine.

Program models

Determining how best to use NP/PAs in hospital medicine programs has had a similar evolution. Reviewing past articles addressing these issues, one can see that there has been clear migration; initially NP/PAs were primarily hired to assist with late-afternoon admission surges, with about 60% of the APP workload being utilized to admit in 2007. Their role has continued to grow and change, much as hospitalist practices have; current program models consist of a few major types, with some novel models coming to the fore.

Another model is use of an NP/PA in an observation unit or with lower acuity observation patients. The majority of the management of the patients is completed and billed by the APP, with the physician available for backup. This hits the “sweet spot,” utilizing the right provider with the right skill set for the right patient. The program has to account for some reimbursement or compensation for the physician oversight time, but it is a very efficient use of APPs.

The third major deployment of APPs is with admissions. Many groups use APPs to admit into the late afternoon and evening, getting patients “tucked in,” including starting diagnostic work-ups and treatment plans. The physician hospitalist then evaluates the patient the next day and often bills for the admission. This model works in situations where the patient work-up is dependent on lab testing, imaging, or other diagnostic testing to understand and plan for the “arc” of the hospitalization; or in situations where the diagnosis is clear, but the patient needs time with treatment to determine response. The downside of this model is long-term job satisfaction for the APP (although some programs have them rotate through such a model at intervals).

Another area where APPs have made strong inroads is that of comanagement services. The NP or PA develops a long-term relationship with a surgical comanagement team, and is often highly engaged and extremely appreciated for managing chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. This can be a very satisfying model for both teams. The NP/PA usually bills independently for these encounters.

APPS are also used in cross coverage and triage roles, allowing the day teams to focus on their primary patients. In a triage role, they can interface with the emergency department, providing a semi-neutral “mediator” for patient disposition.

On the more novel end of the spectrum, there is growth in more independent roles for APP hospitalists. Some groups are having success at using the paired rounding or dyad model, but having the physician see the patient every third day. This is most successful where there is strong onboarding and deep clarity for when to contact the backup physician. There are some data to support the effectiveness of this model, most recently in the Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.3

Critical access hospitals are also having success in deploying APPs in a very independent role, staffing these hospitals at night. Smaller, rural hospitals with aging medical staff have learned to maximize the scope of practice of their APPs to remain viable and provide care for inpatients. This can be a very successful model for APPs working at the maximum scope of their practice. In addition, the use of telemedicine has been implemented to allow for remote physician backup. This may be a rapidly growing arm to hospital medicine practices in the future.

Ongoing barriers

There are many barriers to maximizing the scope of practice and efficiency of APPs in hospital medicine. They range from the “macro” to the “micro.”

On the larger stage, Medicare requires that home care orders be signed by an attending physician, which can be inefficient and difficult to accomplish. Other payers may have somewhat arcane statutes that limit billing practices, and state practice limitations vary widely. Although 22 states now allow for independent practice for NPs, other states may have a very restrictive practice environment that can impede creative care delivery models. But regardless of how liberal a practice the state allows, a hospital’s medical bylaws can still restrict the day-to-day practice of APPs. And those restrictive bylaws are emblematic of a more constant and corporeal barrier to APP practice, that of medical staff culture.

If there are physicians on the staff who fear that utilization of NP/PA providers will lead to a decay in the quality of care, or who feel threatened by the use of APPs, that can create a local stopgap to maximizing utilization of APPs. In addition, hospitalist physicians and leaders may lack knowledge or experience in APP practice. APPs take more time to successfully onboard than physicians; without clear expectations or road maps to accomplish this onboarding, leaders may feel that APP integration doesn’t work. And one bad experience can create long-term barriers for future practices.

Other barriers are the lack of standardized rigor and vigor in graduate education programs (in both educational and clinical experiences). This results in variation in the quality of NP/PA providers at graduation. Knowledge gaps may be perceived as incompetence, rather than just a lack of experience. There is a certificate for added qualification in hospital medicine for PA providers (which includes a specialty exam), and there is an acute care focus for NPs in training; however, there is no standardized licensure to ensure hospital medicine competency, creating a quagmire for hospitalist leaders who desire demonstrable competence of these providers.

Another barrier for some programs is financial; physicians may not want to give up their RVUs to an NP/PA provider. This can really inhibit a more independent role for the APP. It is important that financial incentives align with all members of the practice working at maximum scope.

Summary and future

In summary, the role of PA/NP in hospital medicine has continued to grow and evolve, to meet the needs of the industry. This includes an increase in the scope and independence of APPs, including the use of telehealth for required oversight. As a specialty, it is imperative that we continue to research APP model effectiveness, embrace innovative delivery models, and support effective onboarding and career development opportunities for our NP/PA providers.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Ms. Cardin is vice president, Advanced Practice Providers, at Sound Physicians, and is a member of SHM’s Board of Directors.

References

1. “Midlevels make a rocky entrance into hospital medicine,” by Bonnie Darves, Today’s Hospitalist, January 2007.

2. “When hiring midlevels, proceed with caution,” by Jessica Berthold, ACP Hospitalist, April 2009.

3. “A Comparison of Conventional and Expanded Physician Assistant Hospitalist Staffing Models at a Community Hospital,” J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2016 Oct 1;23[10]:455-61.

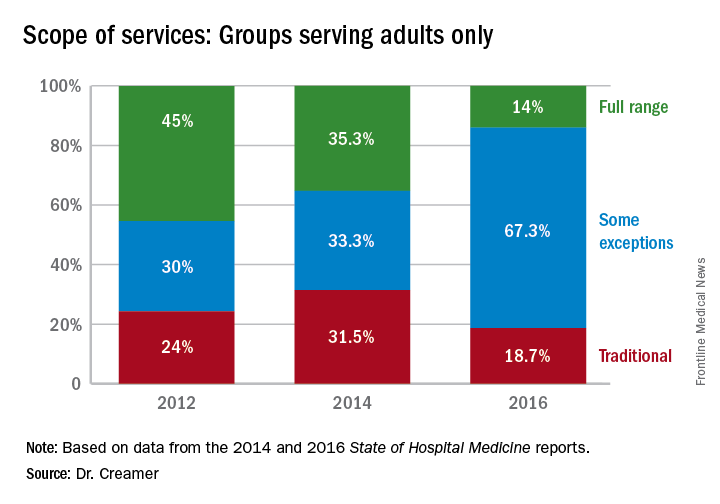

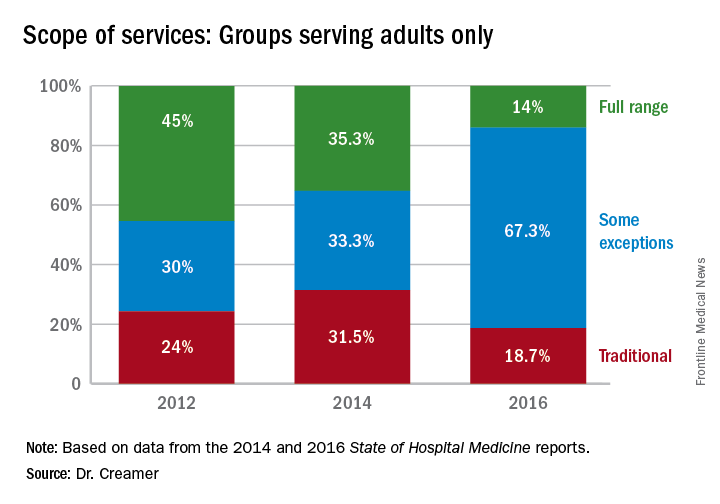

Hospitalists’ scope of services continues to evolve

Over the course of serial iterations of the State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) Report, SHM has presented survey data that describe the evolving role hospitalists play in patient care. The 2016 SOHM Report shows the continuation of prior trends in hospital medicine groups’ (HMGs) scope of admittance and comanagement services. Some downturns are notable among previously increased specialty services.

The SOHM Report characterizes HMGs by their general scope of admitted patients – as admitters of purely traditional internal medicine or pediatrics hospitalized patients; full-range, nearly universal admitters who admit most patients within their age designation except OB and emergency surgery patients; or traditional admitters with some exceptions (for example, limited classically surgical patients).

As adult and adult-ped HMGs make up almost 97% of survey respondents, the predominance of the “some exceptions” category seems to represent a serious trend in much of Hospital Medicine practice. This could mean that HMGs have worked out more specific arrangements as to which patients they will admit or that the definitions are more in flux. It comes at a time when concerns figure prominently in national discussions over the stretching of hospitalists by their expanding scope of care and the need for ever more coordinated care between hospitalists and specialists.

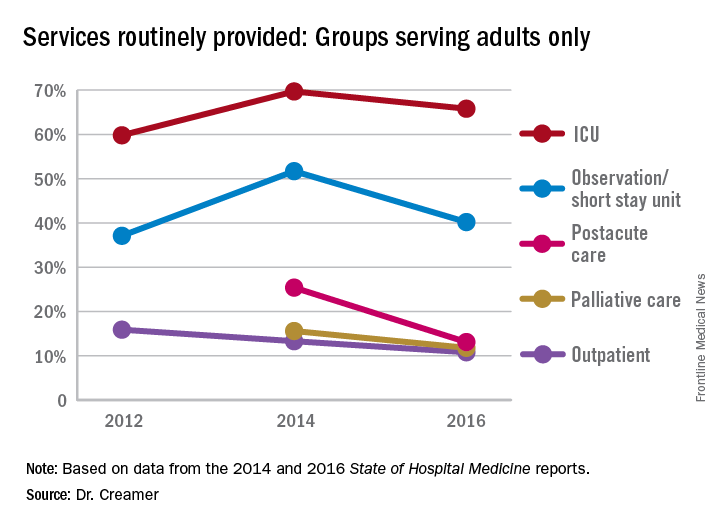

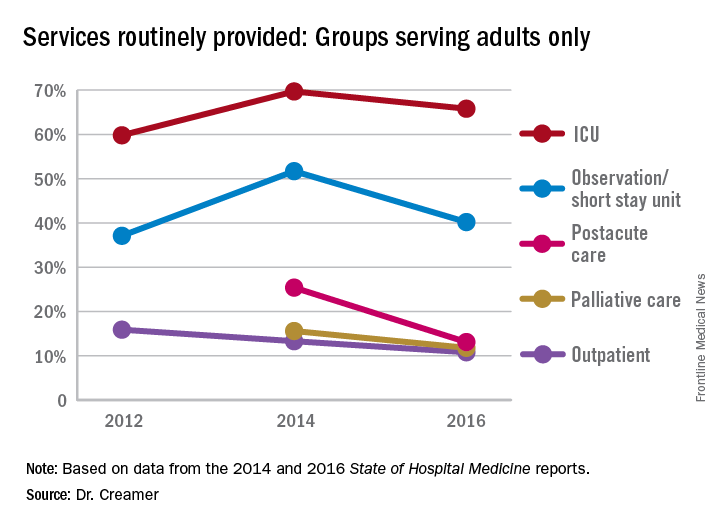

Again, with these opportunities, concerns have arisen about scope-creep and its potential deleterious effects on patient care. Hospitalists have been noted to be prodded into providing critical, geriatric, and palliative care, without specialty training in these areas.1 Interestingly, however, specialty work reported by HMGs has largely shown a downturn since 2014, when most specialty services had appeared to be on the rise.

Whether this means that there is relief from scope-creep or that it is “just a blip” will remain to be seen in future data. If HMGs are able to capture the opportunity to improve outcomes through greater involvement in postacute care, this particular area may be one to watch, despite its apparent downturn since the 2014 report.

Thus, it is as imperative as ever that HMGs participate in the State of Hospital Medicine survey.

Dr. Creamer is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. He is a hospitalist and informaticist with the MetroHealth System in Cleveland.

References

1. Wellikson, L. Hospitalists Stretched as their Responsibilities Broaden. The Hospitalist. 2016 Nov;2016(11).

Over the course of serial iterations of the State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) Report, SHM has presented survey data that describe the evolving role hospitalists play in patient care. The 2016 SOHM Report shows the continuation of prior trends in hospital medicine groups’ (HMGs) scope of admittance and comanagement services. Some downturns are notable among previously increased specialty services.

The SOHM Report characterizes HMGs by their general scope of admitted patients – as admitters of purely traditional internal medicine or pediatrics hospitalized patients; full-range, nearly universal admitters who admit most patients within their age designation except OB and emergency surgery patients; or traditional admitters with some exceptions (for example, limited classically surgical patients).

As adult and adult-ped HMGs make up almost 97% of survey respondents, the predominance of the “some exceptions” category seems to represent a serious trend in much of Hospital Medicine practice. This could mean that HMGs have worked out more specific arrangements as to which patients they will admit or that the definitions are more in flux. It comes at a time when concerns figure prominently in national discussions over the stretching of hospitalists by their expanding scope of care and the need for ever more coordinated care between hospitalists and specialists.

Again, with these opportunities, concerns have arisen about scope-creep and its potential deleterious effects on patient care. Hospitalists have been noted to be prodded into providing critical, geriatric, and palliative care, without specialty training in these areas.1 Interestingly, however, specialty work reported by HMGs has largely shown a downturn since 2014, when most specialty services had appeared to be on the rise.

Whether this means that there is relief from scope-creep or that it is “just a blip” will remain to be seen in future data. If HMGs are able to capture the opportunity to improve outcomes through greater involvement in postacute care, this particular area may be one to watch, despite its apparent downturn since the 2014 report.

Thus, it is as imperative as ever that HMGs participate in the State of Hospital Medicine survey.

Dr. Creamer is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. He is a hospitalist and informaticist with the MetroHealth System in Cleveland.

References

1. Wellikson, L. Hospitalists Stretched as their Responsibilities Broaden. The Hospitalist. 2016 Nov;2016(11).

Over the course of serial iterations of the State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) Report, SHM has presented survey data that describe the evolving role hospitalists play in patient care. The 2016 SOHM Report shows the continuation of prior trends in hospital medicine groups’ (HMGs) scope of admittance and comanagement services. Some downturns are notable among previously increased specialty services.

The SOHM Report characterizes HMGs by their general scope of admitted patients – as admitters of purely traditional internal medicine or pediatrics hospitalized patients; full-range, nearly universal admitters who admit most patients within their age designation except OB and emergency surgery patients; or traditional admitters with some exceptions (for example, limited classically surgical patients).

As adult and adult-ped HMGs make up almost 97% of survey respondents, the predominance of the “some exceptions” category seems to represent a serious trend in much of Hospital Medicine practice. This could mean that HMGs have worked out more specific arrangements as to which patients they will admit or that the definitions are more in flux. It comes at a time when concerns figure prominently in national discussions over the stretching of hospitalists by their expanding scope of care and the need for ever more coordinated care between hospitalists and specialists.

Again, with these opportunities, concerns have arisen about scope-creep and its potential deleterious effects on patient care. Hospitalists have been noted to be prodded into providing critical, geriatric, and palliative care, without specialty training in these areas.1 Interestingly, however, specialty work reported by HMGs has largely shown a downturn since 2014, when most specialty services had appeared to be on the rise.

Whether this means that there is relief from scope-creep or that it is “just a blip” will remain to be seen in future data. If HMGs are able to capture the opportunity to improve outcomes through greater involvement in postacute care, this particular area may be one to watch, despite its apparent downturn since the 2014 report.

Thus, it is as imperative as ever that HMGs participate in the State of Hospital Medicine survey.

Dr. Creamer is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. He is a hospitalist and informaticist with the MetroHealth System in Cleveland.

References

1. Wellikson, L. Hospitalists Stretched as their Responsibilities Broaden. The Hospitalist. 2016 Nov;2016(11).

HM17 session summary: Hospitalists as leaders in patient flow and hospital throughput

Presenters

Gaby Berger, MD; Aaron Hamilton, MD, FHM; Christopher Kim, MD, SFHM; Eduardo Margo, MD; Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM; Anneliese Schleyer, MD, SFHM; Emily Wang, MD

Session Summary

This HM17 workshop brought together academic and community hospitalists to share effective strategies for improving hospital patient flow.

This was followed by a break-out session, in which hospitalists were encouraged to further explore these and other strategies for improving patient flow.

Key takeaways for HM

- Expedited discharge: Identify patients who can be safely discharged before noon. Consider creating standard work to ensure that key steps in discharge planning process, such as completion of medication reconciliation and discharge instructions and communication with patient and families and the interdisciplinary team, occur the day prior to discharge.

- Length of stay reduction strategies: Partner with utilization management to identify and develop a strategy to actively manage patients with long length of stay. Several institutions have set up committees to review such cases and address barriers, escalating requests for resources to executive leadership as needed.

- Facilitate transfers: Develop a standard process that is streamlined and patient-centered and includes established criteria for deciding whether interhospital transfers are appropriate.

- Short Stay Units: Some hospitals have had success with hospitalist-run short stay units as a strategy to decrease length of stay in observation patients. This strategy is most ideal for patients with a predictable length of stay. If you are thinking of starting an observation unit at your hospital, consider establishing criteria and protocols to expedite care.

- Hospitalist Quarterback: Given their broad perspective and clinical knowledge, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to help manage hospital, and even system-wide, capacity in real time. Some hospitals have successfully employed this strategy in some form to improve throughput. However, hospitalists need tools to help them electronically track incoming patients, integration with utilization management resources, and support from executive leadership to be successful.

Dr. Stella is a hospitalist in Denver and an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Presenters

Gaby Berger, MD; Aaron Hamilton, MD, FHM; Christopher Kim, MD, SFHM; Eduardo Margo, MD; Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM; Anneliese Schleyer, MD, SFHM; Emily Wang, MD

Session Summary

This HM17 workshop brought together academic and community hospitalists to share effective strategies for improving hospital patient flow.

This was followed by a break-out session, in which hospitalists were encouraged to further explore these and other strategies for improving patient flow.

Key takeaways for HM

- Expedited discharge: Identify patients who can be safely discharged before noon. Consider creating standard work to ensure that key steps in discharge planning process, such as completion of medication reconciliation and discharge instructions and communication with patient and families and the interdisciplinary team, occur the day prior to discharge.

- Length of stay reduction strategies: Partner with utilization management to identify and develop a strategy to actively manage patients with long length of stay. Several institutions have set up committees to review such cases and address barriers, escalating requests for resources to executive leadership as needed.

- Facilitate transfers: Develop a standard process that is streamlined and patient-centered and includes established criteria for deciding whether interhospital transfers are appropriate.

- Short Stay Units: Some hospitals have had success with hospitalist-run short stay units as a strategy to decrease length of stay in observation patients. This strategy is most ideal for patients with a predictable length of stay. If you are thinking of starting an observation unit at your hospital, consider establishing criteria and protocols to expedite care.

- Hospitalist Quarterback: Given their broad perspective and clinical knowledge, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to help manage hospital, and even system-wide, capacity in real time. Some hospitals have successfully employed this strategy in some form to improve throughput. However, hospitalists need tools to help them electronically track incoming patients, integration with utilization management resources, and support from executive leadership to be successful.

Dr. Stella is a hospitalist in Denver and an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Presenters

Gaby Berger, MD; Aaron Hamilton, MD, FHM; Christopher Kim, MD, SFHM; Eduardo Margo, MD; Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM; Anneliese Schleyer, MD, SFHM; Emily Wang, MD

Session Summary

This HM17 workshop brought together academic and community hospitalists to share effective strategies for improving hospital patient flow.

This was followed by a break-out session, in which hospitalists were encouraged to further explore these and other strategies for improving patient flow.

Key takeaways for HM

- Expedited discharge: Identify patients who can be safely discharged before noon. Consider creating standard work to ensure that key steps in discharge planning process, such as completion of medication reconciliation and discharge instructions and communication with patient and families and the interdisciplinary team, occur the day prior to discharge.

- Length of stay reduction strategies: Partner with utilization management to identify and develop a strategy to actively manage patients with long length of stay. Several institutions have set up committees to review such cases and address barriers, escalating requests for resources to executive leadership as needed.

- Facilitate transfers: Develop a standard process that is streamlined and patient-centered and includes established criteria for deciding whether interhospital transfers are appropriate.

- Short Stay Units: Some hospitals have had success with hospitalist-run short stay units as a strategy to decrease length of stay in observation patients. This strategy is most ideal for patients with a predictable length of stay. If you are thinking of starting an observation unit at your hospital, consider establishing criteria and protocols to expedite care.

- Hospitalist Quarterback: Given their broad perspective and clinical knowledge, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to help manage hospital, and even system-wide, capacity in real time. Some hospitals have successfully employed this strategy in some form to improve throughput. However, hospitalists need tools to help them electronically track incoming patients, integration with utilization management resources, and support from executive leadership to be successful.

Dr. Stella is a hospitalist in Denver and an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Hospitalist meta-leader: Your new mission has arrived

If you are a hospitalist and leader in your health care organization, the ongoing controversies surrounding the Affordable Care Act repeal and replace campaign are unsettling. No matter your politics, Washington’s political drama and gamesmanship pose a genuine threat to the solvency of your hospital’s budget, services, workforce, and patients.

Health care has devolved into a political football, tossed from skirmish to skirmish. Political leaders warn of the implosion of the health care system as a political tactic, not an outcome that could cost and ruin lives. Both Democrats and Republicans hope that if or when that happens, it does so in ways that allow them to blame the other side. For them, this is a game of partisan advantage that wagers the well-being of your health care system.

For you, the situation remains predictably unpredictable. The future directives from Washington are unknowable. This makes your strategic planning – and health care leadership itself – a complex and puzzling task. Your job now is not simply leading your organization for today. Your more important mission is preparing your organization to perform in this unpredictable and perplexing future.

Forecasting is the life blood of leadership: Craft a vision and the work to achieve it; be mindful of the range of obstacles and opportunities; and know and coalesce your followers. The problem is that today’s prospects are loaded with puzzling twists and turns. The viability of both the private insurance market and public dollars are – maybe! – in future jeopardy. Patients and the workforce are understandably jittery. What is a hospitalist leader to do?

It is time to refresh your thinking, to take a big picture view of what is happening and to assess what can be done about it. There is a tendency for leaders to look at problems and then wonder how to fit solutions into their established organizational framework. In other words, solutions are cast into the mold of retaining what you have, ignoring larger options and innovative possibilities. Solutions are expected to adapt to the organization rather than the organization adapting to the solutions.

The hospitalist movement grew as early leaders – true innovators – recognized the problems of costly, inefficient and uncoordinated care. Rather than tinkering with what was, hospitalist leaders introduced a new and proactive model to provide care. It had to first prove itself and once it did, a once revolutionary idea evolved into an institutionalized solution.

No matter what emerges from the current policy debate, the national pressures on the health care system persist: rising expectations for access; decreasing patience for spending; increasing appetite for breakthrough technology; shifting workforce requirements; all combined with a population that is aging and more in need of care. These are meta-trends that will redefine how the health system operates and what it will achieve. What is a health care leader to do?

Think and act like a “meta-leader.” This framework, developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, guides leaders facing complex and transformational problem solving. The prefix “meta-” encourages expansive analysis directed toward a wide range of options and opportunities. In keeping with the strategies employed by hospitalist pioneers, rather than building solutions around “what already is,” meta-leaders pursue “what could be.” In this way, solutions are designed and constructed to fit the problems they are intended to overcome.

There are three critical dimensions to the thinking and practices of meta-leadership.

The first is the Person of the meta-leader. This is who you are, your priorities and values. This is how other people regard your leadership, translated into the respect, trust, and “followership” you garner. Be a role model. This involves building your own confidence for the task at hand so that you gain and then foster the confidence of those you lead. As a meta-leader, you shape your mindset and that of others for innovation, sharpening the curiosity necessary for fostering discovery and exploration of new ideas. Be ready to take appropriate risks.

The second dimension of meta-leadership practice is the Situation. This is what is happening and what can be done about it. You did not create the complex circumstances that derive from the political showdown in Washington. However, it is your job to understand them and to develop effective strategies and operations in response. This is where the “think big” of meta-leadership comes into play. You distinguish the chasm between the adversarial policy confrontation in Washington and the collaborative solution building needed in your home institution. You want to set the stage to meaningfully coalesce the thinking, resources, and people in your organization. The invigorated shared mission is a health care system that leads into the future.

The third dimension of meta-leadership practice is about building the Connectivity needed to make that happen. This involves developing the communication, coordination, and cooperation necessary for constructing something new. Many of your answers lie within the walls of your organization, even the most innovative among them. This is where you sow adaptability and flexibility. It translates into necessary change and transformation. This is reorienting what you and others do and how you go about doing it, from shifts and adjustments to, when necessary, disruptive innovation.

A recent Harvard Business School and Harvard Medical School forum on health care innovation identified five imperatives for meeting innovation challenges in health care: 1) Creating value is the key aim for innovation and it requires a combination of care coordination along with communication; 2) Seek opportunities for process improvement that allows new ideas to be tested, accepting that failure is a step on the road to discovery; 3) Adopt a consumerism strategy for service organization that engages and involves active patients; 4) Decentralize problem solving to encourage field innovation and collaboration; and 5) Integrate new models into established institutions, introducing fresh thinking to replace outdated practices.

Meta-leadership is not a formula for an easy fix. While much remains unpredictable, an impending economic squeeze is a likely scenario. There is nothing easy about a shortage of dollars to serve more and more people in need of clinical care. This may very well be the prompt – today – that encourages the sort of innovative thinking and disruptive solution development that the future requires. Will you and your organization get ahead of this curve?

Your mission as a hospitalist meta-leader is in forging this process of discovery. Perceive what is going on through a wide lens. Orient yourself to emerging trends. Predict what is likely to emerge from this unpredictable policy environment. Take decisions and operationalize them in ways responsive to the circumstances at hand. And then communicate with your constituencies, not only to inform them of direction but also to learn from them what is working and what not. And then you start the process again, trying on ideas and practices, learning from them and through this continuous process, finding solutions that fit your situation at hand.

Health care meta-leaders today must keep both eyes firmly on their feet, to know that current operations are achieving necessary success. At the same time, they must also keep both eyes focused on the horizon, to ensure that when conditions change, their organizations are ready to adaptively innovate and transform.

Leonard J. Marcus, Ph.D. is coauthor of Renegotiating Health Care: Resolving Conflict to Build Collaboration, Second Edition (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 2011) and is director of the program for health care negotiation and conflict resolution, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Dr. Marcus teaches regularly in the SHM Leadership Academy. He can be reached at [email protected]

If you are a hospitalist and leader in your health care organization, the ongoing controversies surrounding the Affordable Care Act repeal and replace campaign are unsettling. No matter your politics, Washington’s political drama and gamesmanship pose a genuine threat to the solvency of your hospital’s budget, services, workforce, and patients.

Health care has devolved into a political football, tossed from skirmish to skirmish. Political leaders warn of the implosion of the health care system as a political tactic, not an outcome that could cost and ruin lives. Both Democrats and Republicans hope that if or when that happens, it does so in ways that allow them to blame the other side. For them, this is a game of partisan advantage that wagers the well-being of your health care system.