User login

Adjustment for characteristics not used by Medicare reduces hospital variations in readmission rates

Clinical question: Can differences in hospital readmission rates be explained by patient characteristics not accounted for by Medicare?

Background: In its Pay for Performance program, Medicare ties payments to readmission rates but adjusts these rates only for limited patient characteristics. Hospitals serving higher-risk patients have received greater penalties. These programs may have the unintended consequence of penalizing hospitals that provide care to higher-risk patients.

Study design: Observational study.

Setting: Medicare admissions claims from 2013 through 2014 in 2,215 hospitals.

Synopsis: Using Medicare claims for admission and linked U.S. census data, the study assessed several clinical and social characteristics not currently used for risk adjustment. A sample of 1,169,014 index admissions among 1,003,664 unique beneficiaries was analyzed. The study compared rates with and without these additional adjustments.

Additional adjustments reduced overall variation in hospital readmission by 9.6%, changed rates upward or downward by 0.4%-0.7% for the 10% of hospitals most affected by the readjustments, and they would be expected to reduce penalties by 52%, 46%, and 41% for hospitals with the largest 1%, 5%, and 10% of penalty reductions, respectively.

Bottom line: Hospitals serving higher-risk patients may be penalized because of the patients they serve rather that the quality of care they provide.

Citation: Roberts ET et al. Assessment of the effect of adjustment for patient characteristics on hospital readmission rates: Implications for Pay for Performance. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11)1498-1507.

Dr. Asuen is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Can differences in hospital readmission rates be explained by patient characteristics not accounted for by Medicare?

Background: In its Pay for Performance program, Medicare ties payments to readmission rates but adjusts these rates only for limited patient characteristics. Hospitals serving higher-risk patients have received greater penalties. These programs may have the unintended consequence of penalizing hospitals that provide care to higher-risk patients.

Study design: Observational study.

Setting: Medicare admissions claims from 2013 through 2014 in 2,215 hospitals.

Synopsis: Using Medicare claims for admission and linked U.S. census data, the study assessed several clinical and social characteristics not currently used for risk adjustment. A sample of 1,169,014 index admissions among 1,003,664 unique beneficiaries was analyzed. The study compared rates with and without these additional adjustments.

Additional adjustments reduced overall variation in hospital readmission by 9.6%, changed rates upward or downward by 0.4%-0.7% for the 10% of hospitals most affected by the readjustments, and they would be expected to reduce penalties by 52%, 46%, and 41% for hospitals with the largest 1%, 5%, and 10% of penalty reductions, respectively.

Bottom line: Hospitals serving higher-risk patients may be penalized because of the patients they serve rather that the quality of care they provide.

Citation: Roberts ET et al. Assessment of the effect of adjustment for patient characteristics on hospital readmission rates: Implications for Pay for Performance. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11)1498-1507.

Dr. Asuen is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Can differences in hospital readmission rates be explained by patient characteristics not accounted for by Medicare?

Background: In its Pay for Performance program, Medicare ties payments to readmission rates but adjusts these rates only for limited patient characteristics. Hospitals serving higher-risk patients have received greater penalties. These programs may have the unintended consequence of penalizing hospitals that provide care to higher-risk patients.

Study design: Observational study.

Setting: Medicare admissions claims from 2013 through 2014 in 2,215 hospitals.

Synopsis: Using Medicare claims for admission and linked U.S. census data, the study assessed several clinical and social characteristics not currently used for risk adjustment. A sample of 1,169,014 index admissions among 1,003,664 unique beneficiaries was analyzed. The study compared rates with and without these additional adjustments.

Additional adjustments reduced overall variation in hospital readmission by 9.6%, changed rates upward or downward by 0.4%-0.7% for the 10% of hospitals most affected by the readjustments, and they would be expected to reduce penalties by 52%, 46%, and 41% for hospitals with the largest 1%, 5%, and 10% of penalty reductions, respectively.

Bottom line: Hospitals serving higher-risk patients may be penalized because of the patients they serve rather that the quality of care they provide.

Citation: Roberts ET et al. Assessment of the effect of adjustment for patient characteristics on hospital readmission rates: Implications for Pay for Performance. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11)1498-1507.

Dr. Asuen is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Becoming a high-value care physician

‘Culture shift’ comes from collective efforts

It’s Monday morning, and Mrs. Jones still has abdominal pain. Your ward team decides to order a CT. On chart review you notice she’s had three other abdominal CTs for the same indication this year. How did this happen? What should you do?

High-value care has been defined by the Institute of Medicine as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.”1 With an estimated $700 billion dollars – 30% of medical expenditures – spent on wasted care, there are rising calls for a transformational shift.2

You are now asked to consider not just everything you can do for a patient, but also the benefits, harms, and costs associated with those choices. But where to start? We recommend that trainees integrate these tips for high-value care into their routine practice.

1. Use evidence-based resources that highlight value

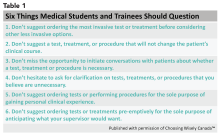

A great place to begin is the “Six Things Medical Students and Trainees Should Question,” originally published in Academic Medicine and created by Choosing Wisely Canada™. Recommendations range from avoiding tests or treatments that will not change a patient’s clinical course to holding off on ordering tests solely based on what you assume your preceptor will want (see the full list in Table 1).3

Other ways to avoid low-value care include following the United States Choosing Wisely™ campaign, which has collected more than 500 specialty society recommendations. Likewise, the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria are designed to assist providers with ordering the appropriate imaging tests (for a more extensive list see Table 2).

2. Express your clinical reasoning

One driver of health care expenditures that is especially prevalent in academia is the pressure to demonstrate knowledge by recommending extensive testing. While these tests may rule out obscure diagnoses, they often do not change management.

You can still demonstrate a mastery of your patients’ care by expressing your thought process overtly. For instance, “I considered secondary causes of the patient’s severe hypertension but felt it was most reasonable to first treat her pain and restart her home medications before pursuing a larger work-up. If the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated and she is hypokalemic, we could consider testing for hyperaldosteronism.” If you explain why you think a diagnosis is less likely and order tests accordingly, others will be encouraged to consider value in their own medical decision making.

3. Hone your communication skills

One of the most cited reasons for providing unnecessary care is the time required to discuss treatment plans with patients – it’s much faster to just order the test than to explain why it isn’t needed. Research, however, shows that these cost conversations take 68 seconds on average.4 Costs of Care (see Table 2) has an excellent video series that highlights how effective communication allows for shared decision making, which promotes both patient engagement and helps avoid wasteful care.

Physicians’ first instincts are often defensive when a patient asks for care we perceive as unnecessary. However, exploring what the patient hopes to gain from said test or treatment frequently reveals concern for a specific, missed diagnosis or complication. Addressing this underlying fear, rather than defending your ordering patterns, can create improved rapport and may serve to provide more reassurance than a test ever could.5

As a physician-in-training, try to observe others having these conversations and take every opportunity to practice. By focusing on this key skill set, you will increase your comfort with in-depth discussions on the value of care.

4. Get involved in a project related to high-value care

While you are developing your own practice patterns, you may be inspired to tackle areas of overuse and underuse at a more systemwide level. If your hospital does not have a committee for high-value care, perhaps a quality improvement leader can support your ideas to launch a project or participate in an ongoing initiative. Physicians-in-training have been identified as crucial to these projects’ success – your frontline insight can highlight potential problems and the nuances of workflow that are key to effective solutions.6

5. Embrace lifelong learning and reflection

The process of becoming a physician and of practicing high-value care is not a sprint but a marathon. Multiple barriers to high-value care exist, and you may feel these pressures differently at various points in your career. These include malpractice concerns, addressing patient expectations, and the desire to take action “just to be safe.”6

Interestingly, fear of malpractice does not seem to dissipate in areas where tort reform has provided stronger provider protections.7 Practitioners may also inaccurately assume a patient’s desire for additional work-up or treatment.8 Furthermore, be aware of the role of “commission bias” by which a provider regrets not doing something that could have helped a previous patient. This regret can prove to be a stronger motivator than the potential harm related to unnecessary diagnostic tests or treatments.9

While these barriers cannot be removed easily, learners and providers can practice active reflection by examining their own fears, biases, and motivations before and after they order additional testing or treatment.

As a physician-in-training, you may feel that your decisions do not have a major impact on the health care system as a whole. However, the culture shift needed to “bend the cost curve” will come from the collective efforts of individuals like you. Practicing high-value care is not just a matter of ordering fewer tests – appropriate ordering of an expensive test that expedites a diagnosis may be more cost-effective and enhance the quality of care provided. Increasing your own awareness of both necessary and unnecessary practices is a major step toward realizing system change. Your efforts to resist and reform the medical culture that propagates low value care will encourage your colleagues to follow suit.

Dr. Lacy is assistant professor and associate clerkship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, as well as division director of high-value care for the division of hospital medicine. Dr. Goetz is assistant professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. They met as 2015 Copello Fellows at the National Physician Alliance. Both have been involved in numerous high-value care initiatives, curricular development, and medical education at their respective institutions.

References

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, Institute of Medicine. “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Edited by Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, and McGinnis JM. (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207225/.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-6.

3. Lakhani A et al. Choosing Wisely for Medical Education: Six things medical students and trainees should question. Acad Med. 2016 Oct;91(10):1374-8.

4. Hunter WG et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: Definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:108.

5. van Ravesteijn H et al. The reassuring value of diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):3-8.

6. Moriates C, Wong BM. High-value care programmes from the bottom-up… and the top-down. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):821-3.

7. Snyder Sulmasy L, Weinberger SE. Better care is the best defense: High-value clinical practice vs. defensive medicine. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014;81(8):464-7.

8. Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: Patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572.

9. Scott IA. Cognitive challenges to minimising low value care. Intern Med J. 2017;47(9):1079-1083.

‘Culture shift’ comes from collective efforts

‘Culture shift’ comes from collective efforts

It’s Monday morning, and Mrs. Jones still has abdominal pain. Your ward team decides to order a CT. On chart review you notice she’s had three other abdominal CTs for the same indication this year. How did this happen? What should you do?

High-value care has been defined by the Institute of Medicine as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.”1 With an estimated $700 billion dollars – 30% of medical expenditures – spent on wasted care, there are rising calls for a transformational shift.2

You are now asked to consider not just everything you can do for a patient, but also the benefits, harms, and costs associated with those choices. But where to start? We recommend that trainees integrate these tips for high-value care into their routine practice.

1. Use evidence-based resources that highlight value

A great place to begin is the “Six Things Medical Students and Trainees Should Question,” originally published in Academic Medicine and created by Choosing Wisely Canada™. Recommendations range from avoiding tests or treatments that will not change a patient’s clinical course to holding off on ordering tests solely based on what you assume your preceptor will want (see the full list in Table 1).3

Other ways to avoid low-value care include following the United States Choosing Wisely™ campaign, which has collected more than 500 specialty society recommendations. Likewise, the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria are designed to assist providers with ordering the appropriate imaging tests (for a more extensive list see Table 2).

2. Express your clinical reasoning

One driver of health care expenditures that is especially prevalent in academia is the pressure to demonstrate knowledge by recommending extensive testing. While these tests may rule out obscure diagnoses, they often do not change management.

You can still demonstrate a mastery of your patients’ care by expressing your thought process overtly. For instance, “I considered secondary causes of the patient’s severe hypertension but felt it was most reasonable to first treat her pain and restart her home medications before pursuing a larger work-up. If the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated and she is hypokalemic, we could consider testing for hyperaldosteronism.” If you explain why you think a diagnosis is less likely and order tests accordingly, others will be encouraged to consider value in their own medical decision making.

3. Hone your communication skills

One of the most cited reasons for providing unnecessary care is the time required to discuss treatment plans with patients – it’s much faster to just order the test than to explain why it isn’t needed. Research, however, shows that these cost conversations take 68 seconds on average.4 Costs of Care (see Table 2) has an excellent video series that highlights how effective communication allows for shared decision making, which promotes both patient engagement and helps avoid wasteful care.

Physicians’ first instincts are often defensive when a patient asks for care we perceive as unnecessary. However, exploring what the patient hopes to gain from said test or treatment frequently reveals concern for a specific, missed diagnosis or complication. Addressing this underlying fear, rather than defending your ordering patterns, can create improved rapport and may serve to provide more reassurance than a test ever could.5

As a physician-in-training, try to observe others having these conversations and take every opportunity to practice. By focusing on this key skill set, you will increase your comfort with in-depth discussions on the value of care.

4. Get involved in a project related to high-value care

While you are developing your own practice patterns, you may be inspired to tackle areas of overuse and underuse at a more systemwide level. If your hospital does not have a committee for high-value care, perhaps a quality improvement leader can support your ideas to launch a project or participate in an ongoing initiative. Physicians-in-training have been identified as crucial to these projects’ success – your frontline insight can highlight potential problems and the nuances of workflow that are key to effective solutions.6

5. Embrace lifelong learning and reflection

The process of becoming a physician and of practicing high-value care is not a sprint but a marathon. Multiple barriers to high-value care exist, and you may feel these pressures differently at various points in your career. These include malpractice concerns, addressing patient expectations, and the desire to take action “just to be safe.”6

Interestingly, fear of malpractice does not seem to dissipate in areas where tort reform has provided stronger provider protections.7 Practitioners may also inaccurately assume a patient’s desire for additional work-up or treatment.8 Furthermore, be aware of the role of “commission bias” by which a provider regrets not doing something that could have helped a previous patient. This regret can prove to be a stronger motivator than the potential harm related to unnecessary diagnostic tests or treatments.9

While these barriers cannot be removed easily, learners and providers can practice active reflection by examining their own fears, biases, and motivations before and after they order additional testing or treatment.

As a physician-in-training, you may feel that your decisions do not have a major impact on the health care system as a whole. However, the culture shift needed to “bend the cost curve” will come from the collective efforts of individuals like you. Practicing high-value care is not just a matter of ordering fewer tests – appropriate ordering of an expensive test that expedites a diagnosis may be more cost-effective and enhance the quality of care provided. Increasing your own awareness of both necessary and unnecessary practices is a major step toward realizing system change. Your efforts to resist and reform the medical culture that propagates low value care will encourage your colleagues to follow suit.

Dr. Lacy is assistant professor and associate clerkship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, as well as division director of high-value care for the division of hospital medicine. Dr. Goetz is assistant professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. They met as 2015 Copello Fellows at the National Physician Alliance. Both have been involved in numerous high-value care initiatives, curricular development, and medical education at their respective institutions.

References

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, Institute of Medicine. “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Edited by Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, and McGinnis JM. (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207225/.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-6.

3. Lakhani A et al. Choosing Wisely for Medical Education: Six things medical students and trainees should question. Acad Med. 2016 Oct;91(10):1374-8.

4. Hunter WG et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: Definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:108.

5. van Ravesteijn H et al. The reassuring value of diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):3-8.

6. Moriates C, Wong BM. High-value care programmes from the bottom-up… and the top-down. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):821-3.

7. Snyder Sulmasy L, Weinberger SE. Better care is the best defense: High-value clinical practice vs. defensive medicine. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014;81(8):464-7.

8. Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: Patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572.

9. Scott IA. Cognitive challenges to minimising low value care. Intern Med J. 2017;47(9):1079-1083.

It’s Monday morning, and Mrs. Jones still has abdominal pain. Your ward team decides to order a CT. On chart review you notice she’s had three other abdominal CTs for the same indication this year. How did this happen? What should you do?

High-value care has been defined by the Institute of Medicine as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.”1 With an estimated $700 billion dollars – 30% of medical expenditures – spent on wasted care, there are rising calls for a transformational shift.2

You are now asked to consider not just everything you can do for a patient, but also the benefits, harms, and costs associated with those choices. But where to start? We recommend that trainees integrate these tips for high-value care into their routine practice.

1. Use evidence-based resources that highlight value

A great place to begin is the “Six Things Medical Students and Trainees Should Question,” originally published in Academic Medicine and created by Choosing Wisely Canada™. Recommendations range from avoiding tests or treatments that will not change a patient’s clinical course to holding off on ordering tests solely based on what you assume your preceptor will want (see the full list in Table 1).3

Other ways to avoid low-value care include following the United States Choosing Wisely™ campaign, which has collected more than 500 specialty society recommendations. Likewise, the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria are designed to assist providers with ordering the appropriate imaging tests (for a more extensive list see Table 2).

2. Express your clinical reasoning

One driver of health care expenditures that is especially prevalent in academia is the pressure to demonstrate knowledge by recommending extensive testing. While these tests may rule out obscure diagnoses, they often do not change management.

You can still demonstrate a mastery of your patients’ care by expressing your thought process overtly. For instance, “I considered secondary causes of the patient’s severe hypertension but felt it was most reasonable to first treat her pain and restart her home medications before pursuing a larger work-up. If the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated and she is hypokalemic, we could consider testing for hyperaldosteronism.” If you explain why you think a diagnosis is less likely and order tests accordingly, others will be encouraged to consider value in their own medical decision making.

3. Hone your communication skills

One of the most cited reasons for providing unnecessary care is the time required to discuss treatment plans with patients – it’s much faster to just order the test than to explain why it isn’t needed. Research, however, shows that these cost conversations take 68 seconds on average.4 Costs of Care (see Table 2) has an excellent video series that highlights how effective communication allows for shared decision making, which promotes both patient engagement and helps avoid wasteful care.

Physicians’ first instincts are often defensive when a patient asks for care we perceive as unnecessary. However, exploring what the patient hopes to gain from said test or treatment frequently reveals concern for a specific, missed diagnosis or complication. Addressing this underlying fear, rather than defending your ordering patterns, can create improved rapport and may serve to provide more reassurance than a test ever could.5

As a physician-in-training, try to observe others having these conversations and take every opportunity to practice. By focusing on this key skill set, you will increase your comfort with in-depth discussions on the value of care.

4. Get involved in a project related to high-value care

While you are developing your own practice patterns, you may be inspired to tackle areas of overuse and underuse at a more systemwide level. If your hospital does not have a committee for high-value care, perhaps a quality improvement leader can support your ideas to launch a project or participate in an ongoing initiative. Physicians-in-training have been identified as crucial to these projects’ success – your frontline insight can highlight potential problems and the nuances of workflow that are key to effective solutions.6

5. Embrace lifelong learning and reflection

The process of becoming a physician and of practicing high-value care is not a sprint but a marathon. Multiple barriers to high-value care exist, and you may feel these pressures differently at various points in your career. These include malpractice concerns, addressing patient expectations, and the desire to take action “just to be safe.”6

Interestingly, fear of malpractice does not seem to dissipate in areas where tort reform has provided stronger provider protections.7 Practitioners may also inaccurately assume a patient’s desire for additional work-up or treatment.8 Furthermore, be aware of the role of “commission bias” by which a provider regrets not doing something that could have helped a previous patient. This regret can prove to be a stronger motivator than the potential harm related to unnecessary diagnostic tests or treatments.9

While these barriers cannot be removed easily, learners and providers can practice active reflection by examining their own fears, biases, and motivations before and after they order additional testing or treatment.

As a physician-in-training, you may feel that your decisions do not have a major impact on the health care system as a whole. However, the culture shift needed to “bend the cost curve” will come from the collective efforts of individuals like you. Practicing high-value care is not just a matter of ordering fewer tests – appropriate ordering of an expensive test that expedites a diagnosis may be more cost-effective and enhance the quality of care provided. Increasing your own awareness of both necessary and unnecessary practices is a major step toward realizing system change. Your efforts to resist and reform the medical culture that propagates low value care will encourage your colleagues to follow suit.

Dr. Lacy is assistant professor and associate clerkship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, as well as division director of high-value care for the division of hospital medicine. Dr. Goetz is assistant professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. They met as 2015 Copello Fellows at the National Physician Alliance. Both have been involved in numerous high-value care initiatives, curricular development, and medical education at their respective institutions.

References

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, Institute of Medicine. “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Edited by Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, and McGinnis JM. (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207225/.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-6.

3. Lakhani A et al. Choosing Wisely for Medical Education: Six things medical students and trainees should question. Acad Med. 2016 Oct;91(10):1374-8.

4. Hunter WG et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: Definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:108.

5. van Ravesteijn H et al. The reassuring value of diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):3-8.

6. Moriates C, Wong BM. High-value care programmes from the bottom-up… and the top-down. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):821-3.

7. Snyder Sulmasy L, Weinberger SE. Better care is the best defense: High-value clinical practice vs. defensive medicine. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014;81(8):464-7.

8. Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: Patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572.

9. Scott IA. Cognitive challenges to minimising low value care. Intern Med J. 2017;47(9):1079-1083.

Physician burnout may be jeopardizing patient care

Clinical question: Is physician burnout associated with more patient safety issues, low professionalism, or poor patient satisfaction?

Background: Burnout is common among physicians and has a negative effect on their personal lives. It is unclear whether physician burnout is associated with poor outcomes for patients.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Forty-seven published studies from 19 countries assessing inpatient and outpatient physicians and the relationship between physician burnout and patient care.

Synopsis: After a systematic review of the published literature, 47 studies were included to pool data from 42,473 physicians. Study subjects included residents, early-career and late-career physicians, and both hospital and outpatient physicians. All studies used validated measures of physician burnout.

Burnout was associated with a two-fold increased risk of physician-reported safety incidents (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), low professionalism (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85), and likelihood of low patient-reported satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68). There were no significant differences in these results based on country of origin of the study. Early-career physicians were more likely to have burnout associated with low professionalism than were late-career physicians.

Of the components of burnout, depersonalization was most strongly associated with these negative outcomes. Interestingly, the increased risk of patient safety incidents was associated with physician-reported, but not health care system–reported, patient safety outcomes. This raises concerns that the health care systems may not be capturing “near misses” in their metrics.

Bottom line: Physician burnout doubles the risk of being involved in a patient safety incident, low professionalism, and poor patient satisfaction.

Citation: Panagioti M et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-30.

Dr. Gabriel is assistant professor of medicine and director of Pre-operative Medicine and Medicine Consult Service in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Is physician burnout associated with more patient safety issues, low professionalism, or poor patient satisfaction?

Background: Burnout is common among physicians and has a negative effect on their personal lives. It is unclear whether physician burnout is associated with poor outcomes for patients.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Forty-seven published studies from 19 countries assessing inpatient and outpatient physicians and the relationship between physician burnout and patient care.

Synopsis: After a systematic review of the published literature, 47 studies were included to pool data from 42,473 physicians. Study subjects included residents, early-career and late-career physicians, and both hospital and outpatient physicians. All studies used validated measures of physician burnout.

Burnout was associated with a two-fold increased risk of physician-reported safety incidents (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), low professionalism (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85), and likelihood of low patient-reported satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68). There were no significant differences in these results based on country of origin of the study. Early-career physicians were more likely to have burnout associated with low professionalism than were late-career physicians.

Of the components of burnout, depersonalization was most strongly associated with these negative outcomes. Interestingly, the increased risk of patient safety incidents was associated with physician-reported, but not health care system–reported, patient safety outcomes. This raises concerns that the health care systems may not be capturing “near misses” in their metrics.

Bottom line: Physician burnout doubles the risk of being involved in a patient safety incident, low professionalism, and poor patient satisfaction.

Citation: Panagioti M et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-30.

Dr. Gabriel is assistant professor of medicine and director of Pre-operative Medicine and Medicine Consult Service in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Is physician burnout associated with more patient safety issues, low professionalism, or poor patient satisfaction?

Background: Burnout is common among physicians and has a negative effect on their personal lives. It is unclear whether physician burnout is associated with poor outcomes for patients.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Forty-seven published studies from 19 countries assessing inpatient and outpatient physicians and the relationship between physician burnout and patient care.

Synopsis: After a systematic review of the published literature, 47 studies were included to pool data from 42,473 physicians. Study subjects included residents, early-career and late-career physicians, and both hospital and outpatient physicians. All studies used validated measures of physician burnout.

Burnout was associated with a two-fold increased risk of physician-reported safety incidents (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), low professionalism (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85), and likelihood of low patient-reported satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68). There were no significant differences in these results based on country of origin of the study. Early-career physicians were more likely to have burnout associated with low professionalism than were late-career physicians.

Of the components of burnout, depersonalization was most strongly associated with these negative outcomes. Interestingly, the increased risk of patient safety incidents was associated with physician-reported, but not health care system–reported, patient safety outcomes. This raises concerns that the health care systems may not be capturing “near misses” in their metrics.

Bottom line: Physician burnout doubles the risk of being involved in a patient safety incident, low professionalism, and poor patient satisfaction.

Citation: Panagioti M et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-30.

Dr. Gabriel is assistant professor of medicine and director of Pre-operative Medicine and Medicine Consult Service in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Creating better performance incentives

P4P programs suffer from several flaws

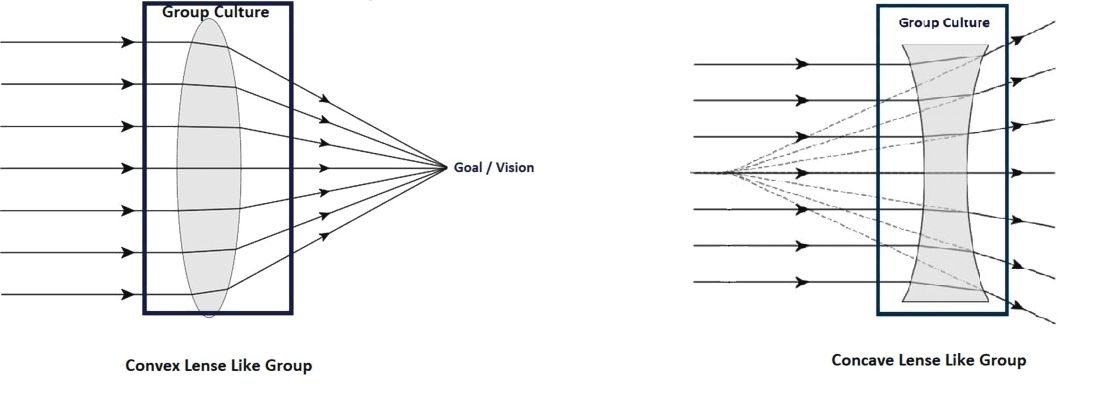

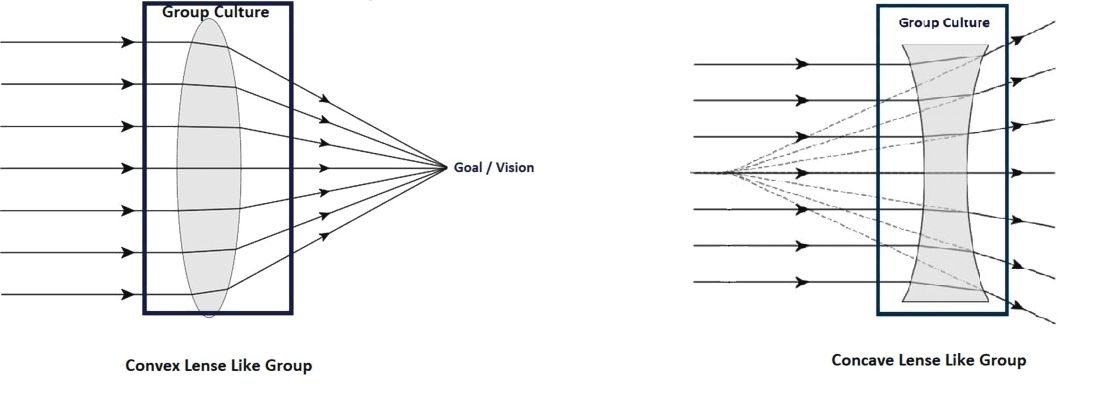

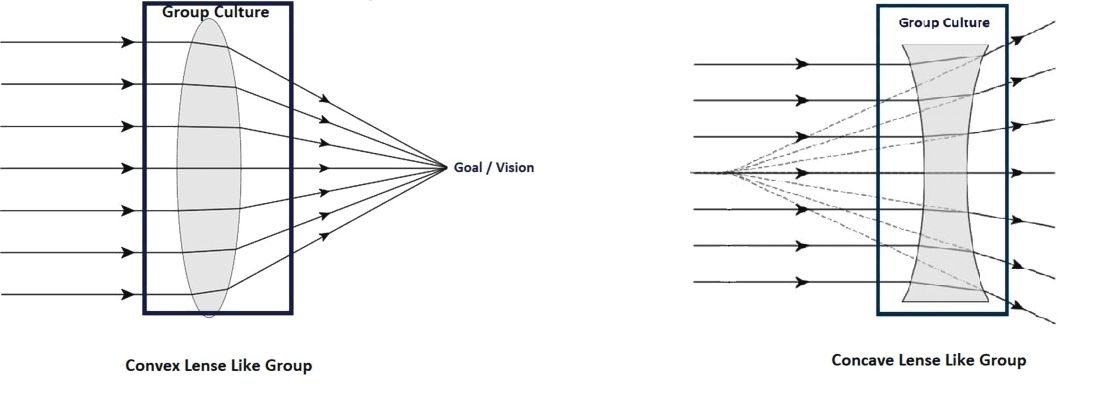

Many performance improvement programs try to create a higher value health system by incentivizing physicians and health systems to behave in particular ways. These have often been pay-for-performance programs that offer bonuses or impose penalties depending on how providers perform on various metrics.

“In theory, this makes sense,” said Dhruv Khullar, MD, MPP, lead author of a JAMA article about the future of incentives, and assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. “But in practice, these programs have not been successful in consistently improving quality, and sometimes they have been counterproductive. In our article, we argued that focusing too narrowly on financial rewards is not the right strategy to improve health system performance – and is sometimes at odds with the physician professionalism and what really motivates most clinicians.”

Pay-for-performance programs suffer from several fundamental flaws: they focus too narrowly on financial incentives and use centralized accountability instead of local culture, for example, Dr. Khullar said.

“A better future state would involve capitalizing on physician professionalism through nonfinancial rewards, resources for quality improvement, team-based assessments, and emphasizing continuous learning and organizational culture,” he noted. Performance programs would take a more global view of clinical care by emphasizing culture, teams, trust, and learning. Such a system would allow hospitalists and other physicians to worry less about meeting specific metrics and focus more on providing high-quality care to their patients.

“I would hope physicians, payers, and administrators would reconsider some previously held beliefs about quality improvement, especially the idea that better quality requires giving people bonus payments or imposing financial penalties,” Dr. Khullar said. “We believe the next wave of performance improvement programs should entertain other paths to better quality, which are more in line with human motivation and physician professionalism.”

Reference

1. Khullar D, Wolfson D, Casalino LP. Professionalism, Performance, and the Future of Physician Incentives. JAMA. 2018 Nov 26 (Epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17719. Accessed Dec. 11, 2018.

P4P programs suffer from several flaws

P4P programs suffer from several flaws

Many performance improvement programs try to create a higher value health system by incentivizing physicians and health systems to behave in particular ways. These have often been pay-for-performance programs that offer bonuses or impose penalties depending on how providers perform on various metrics.

“In theory, this makes sense,” said Dhruv Khullar, MD, MPP, lead author of a JAMA article about the future of incentives, and assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. “But in practice, these programs have not been successful in consistently improving quality, and sometimes they have been counterproductive. In our article, we argued that focusing too narrowly on financial rewards is not the right strategy to improve health system performance – and is sometimes at odds with the physician professionalism and what really motivates most clinicians.”

Pay-for-performance programs suffer from several fundamental flaws: they focus too narrowly on financial incentives and use centralized accountability instead of local culture, for example, Dr. Khullar said.

“A better future state would involve capitalizing on physician professionalism through nonfinancial rewards, resources for quality improvement, team-based assessments, and emphasizing continuous learning and organizational culture,” he noted. Performance programs would take a more global view of clinical care by emphasizing culture, teams, trust, and learning. Such a system would allow hospitalists and other physicians to worry less about meeting specific metrics and focus more on providing high-quality care to their patients.

“I would hope physicians, payers, and administrators would reconsider some previously held beliefs about quality improvement, especially the idea that better quality requires giving people bonus payments or imposing financial penalties,” Dr. Khullar said. “We believe the next wave of performance improvement programs should entertain other paths to better quality, which are more in line with human motivation and physician professionalism.”

Reference

1. Khullar D, Wolfson D, Casalino LP. Professionalism, Performance, and the Future of Physician Incentives. JAMA. 2018 Nov 26 (Epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17719. Accessed Dec. 11, 2018.

Many performance improvement programs try to create a higher value health system by incentivizing physicians and health systems to behave in particular ways. These have often been pay-for-performance programs that offer bonuses or impose penalties depending on how providers perform on various metrics.

“In theory, this makes sense,” said Dhruv Khullar, MD, MPP, lead author of a JAMA article about the future of incentives, and assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. “But in practice, these programs have not been successful in consistently improving quality, and sometimes they have been counterproductive. In our article, we argued that focusing too narrowly on financial rewards is not the right strategy to improve health system performance – and is sometimes at odds with the physician professionalism and what really motivates most clinicians.”

Pay-for-performance programs suffer from several fundamental flaws: they focus too narrowly on financial incentives and use centralized accountability instead of local culture, for example, Dr. Khullar said.

“A better future state would involve capitalizing on physician professionalism through nonfinancial rewards, resources for quality improvement, team-based assessments, and emphasizing continuous learning and organizational culture,” he noted. Performance programs would take a more global view of clinical care by emphasizing culture, teams, trust, and learning. Such a system would allow hospitalists and other physicians to worry less about meeting specific metrics and focus more on providing high-quality care to their patients.

“I would hope physicians, payers, and administrators would reconsider some previously held beliefs about quality improvement, especially the idea that better quality requires giving people bonus payments or imposing financial penalties,” Dr. Khullar said. “We believe the next wave of performance improvement programs should entertain other paths to better quality, which are more in line with human motivation and physician professionalism.”

Reference

1. Khullar D, Wolfson D, Casalino LP. Professionalism, Performance, and the Future of Physician Incentives. JAMA. 2018 Nov 26 (Epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17719. Accessed Dec. 11, 2018.

Reducing adverse drug reactions

Easing the inpatient/outpatient transition

Adverse drug reactions are a problem hospitalists encounter often. An estimated 9% of hospital admissions in older adults are the result of adverse drug reactions, and up to one in five adults experience an adverse drug reaction during hospitalization.

“Many interventions have been tried to solve this problem, and certain of them have worked, but to date we don’t have any great solutions that meaningfully impact the rate of these events in a way that’s feasible in most health care environments, so any efforts to reduce the burden of these problems in older adults could be hugely beneficial,” said Michael Steinman, MD, author of an editorial highlighting a new approach.

His editorial in BMJ Quality & Safety cites research on the Pharm2Pharm program, implemented in six Hawaiian hospitals, in which hospital-based pharmacists identified inpatients at high risk of medication misadventures with criteria such as use of multiple medications, presence of high-risk medications such as warfarin or glucose-lowering drugs, and a history of previous acute care use resulting from medication-related problems. The hospital pharmacist would then meet with the patient to reconcile medications and facilitate a coordinated hand-off to a community pharmacist, who would meet with the patient after discharge.

In addition to a 36% reduction in the rate of medication-related hospitalizations, the intervention generated an estimated savings of $6.6 million per year in avoided hospitalizations.

There are two major takeaways, said Dr. Steinman, who is based in the division of geriatrics at the University of California, San Francisco: It’s critical to focus on transitions and coordination between inpatient and outpatient care to address medication-related problems, and pharmacists can be extremely helpful in that.

“Decisions about drug therapy in the hospital may seem reasonable in the short term but often won’t stick in the long term unless there is a coordinated care that can help ensure appropriate follow-through once patients return home,” Dr. Steinman said. “The study that the editorial references is a systems intervention that hospitalists can advocate for in their own institutions, but in the immediate day-to-day, trying to ensure solid coordination of medication management from the inpatient to outpatient setting is likely to be very helpful for their patients.”

The long-term outcomes of hospitalized patients are largely influenced by getting them set up with appropriate community resources and supports once they leave the hospital, he added, and the hospital can play a critical role in putting these pieces into place.

Reference

1. Steinman MA. Reducing hospital admissions for adverse drug events through coordinated pharmacist care: learning from Hawai’i without a field trip. BMJ Qual Saf. Epub 2018 Nov 24. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008815. Accessed Dec. 11, 2018.

Easing the inpatient/outpatient transition

Easing the inpatient/outpatient transition

Adverse drug reactions are a problem hospitalists encounter often. An estimated 9% of hospital admissions in older adults are the result of adverse drug reactions, and up to one in five adults experience an adverse drug reaction during hospitalization.

“Many interventions have been tried to solve this problem, and certain of them have worked, but to date we don’t have any great solutions that meaningfully impact the rate of these events in a way that’s feasible in most health care environments, so any efforts to reduce the burden of these problems in older adults could be hugely beneficial,” said Michael Steinman, MD, author of an editorial highlighting a new approach.

His editorial in BMJ Quality & Safety cites research on the Pharm2Pharm program, implemented in six Hawaiian hospitals, in which hospital-based pharmacists identified inpatients at high risk of medication misadventures with criteria such as use of multiple medications, presence of high-risk medications such as warfarin or glucose-lowering drugs, and a history of previous acute care use resulting from medication-related problems. The hospital pharmacist would then meet with the patient to reconcile medications and facilitate a coordinated hand-off to a community pharmacist, who would meet with the patient after discharge.

In addition to a 36% reduction in the rate of medication-related hospitalizations, the intervention generated an estimated savings of $6.6 million per year in avoided hospitalizations.

There are two major takeaways, said Dr. Steinman, who is based in the division of geriatrics at the University of California, San Francisco: It’s critical to focus on transitions and coordination between inpatient and outpatient care to address medication-related problems, and pharmacists can be extremely helpful in that.

“Decisions about drug therapy in the hospital may seem reasonable in the short term but often won’t stick in the long term unless there is a coordinated care that can help ensure appropriate follow-through once patients return home,” Dr. Steinman said. “The study that the editorial references is a systems intervention that hospitalists can advocate for in their own institutions, but in the immediate day-to-day, trying to ensure solid coordination of medication management from the inpatient to outpatient setting is likely to be very helpful for their patients.”

The long-term outcomes of hospitalized patients are largely influenced by getting them set up with appropriate community resources and supports once they leave the hospital, he added, and the hospital can play a critical role in putting these pieces into place.

Reference

1. Steinman MA. Reducing hospital admissions for adverse drug events through coordinated pharmacist care: learning from Hawai’i without a field trip. BMJ Qual Saf. Epub 2018 Nov 24. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008815. Accessed Dec. 11, 2018.

Adverse drug reactions are a problem hospitalists encounter often. An estimated 9% of hospital admissions in older adults are the result of adverse drug reactions, and up to one in five adults experience an adverse drug reaction during hospitalization.

“Many interventions have been tried to solve this problem, and certain of them have worked, but to date we don’t have any great solutions that meaningfully impact the rate of these events in a way that’s feasible in most health care environments, so any efforts to reduce the burden of these problems in older adults could be hugely beneficial,” said Michael Steinman, MD, author of an editorial highlighting a new approach.

His editorial in BMJ Quality & Safety cites research on the Pharm2Pharm program, implemented in six Hawaiian hospitals, in which hospital-based pharmacists identified inpatients at high risk of medication misadventures with criteria such as use of multiple medications, presence of high-risk medications such as warfarin or glucose-lowering drugs, and a history of previous acute care use resulting from medication-related problems. The hospital pharmacist would then meet with the patient to reconcile medications and facilitate a coordinated hand-off to a community pharmacist, who would meet with the patient after discharge.

In addition to a 36% reduction in the rate of medication-related hospitalizations, the intervention generated an estimated savings of $6.6 million per year in avoided hospitalizations.

There are two major takeaways, said Dr. Steinman, who is based in the division of geriatrics at the University of California, San Francisco: It’s critical to focus on transitions and coordination between inpatient and outpatient care to address medication-related problems, and pharmacists can be extremely helpful in that.

“Decisions about drug therapy in the hospital may seem reasonable in the short term but often won’t stick in the long term unless there is a coordinated care that can help ensure appropriate follow-through once patients return home,” Dr. Steinman said. “The study that the editorial references is a systems intervention that hospitalists can advocate for in their own institutions, but in the immediate day-to-day, trying to ensure solid coordination of medication management from the inpatient to outpatient setting is likely to be very helpful for their patients.”

The long-term outcomes of hospitalized patients are largely influenced by getting them set up with appropriate community resources and supports once they leave the hospital, he added, and the hospital can play a critical role in putting these pieces into place.

Reference

1. Steinman MA. Reducing hospital admissions for adverse drug events through coordinated pharmacist care: learning from Hawai’i without a field trip. BMJ Qual Saf. Epub 2018 Nov 24. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008815. Accessed Dec. 11, 2018.

Bringing QI training to an IM residency program

Consider a formal step-wise curriculum

For current and future hospitalists, there’s no doubt that knowledge of quality improvement (QI) fundamentals is an important component of a successful practice. One physician team set out to provide their trainees with that QI foundation and described the results.

“We believed that implementing a formal step-wise QI curriculum would not only meet the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements, but also increase residents’ knowledge of QI fundamentals and ultimately establish a culture of continuous improvement aiming to provide high-value care to our health care consumers,” said lead author J. Colt Cowdell, MD, MBA, of Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

Prior to any interventions, the team surveyed internal medicine residents regarding three unique patient scenarios and scored their answers. Residents were then assigned to one of five unique QI projects for the academic year in combination with a structured didactic QI curriculum.

After the structured progressive curriculum, in combination with team-based QI projects, residents were surveyed again. Results showed not only increased QI knowledge, but also improved patient safety and reduced waste.

“Keys to successful implementation included a thorough explanation of the need for this curriculum to the learners and ensuring that QI teams were multidisciplinary – residents, QI experts, nurses, techs, pharmacy, administrators, etc.,” said Dr. Cowdell.

For hospitalists in an academic setting, this work can provide a framework to incorporate QI into their residency programs. “I hope, if they have a passion for QI, they would seek out opportunities to mentor residents and help lead multidisciplinary team-based projects,” Dr. Cowdell said.

Reference

1. Cowdell, JC; Trautman, C; Lewis, M; Dawson, N. Integration of a Novel Quality Improvement Curriculum into an Internal Medicine Residency Program. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2018; April 8-11; Orlando, Fla. Abstract 54. https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/integration-of-a-novel-quality-improvement-curriculum-into-an-internal-medicine-residency-program/. Accessed Dec. 11, 2018.

Consider a formal step-wise curriculum

Consider a formal step-wise curriculum

For current and future hospitalists, there’s no doubt that knowledge of quality improvement (QI) fundamentals is an important component of a successful practice. One physician team set out to provide their trainees with that QI foundation and described the results.

“We believed that implementing a formal step-wise QI curriculum would not only meet the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements, but also increase residents’ knowledge of QI fundamentals and ultimately establish a culture of continuous improvement aiming to provide high-value care to our health care consumers,” said lead author J. Colt Cowdell, MD, MBA, of Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

Prior to any interventions, the team surveyed internal medicine residents regarding three unique patient scenarios and scored their answers. Residents were then assigned to one of five unique QI projects for the academic year in combination with a structured didactic QI curriculum.

After the structured progressive curriculum, in combination with team-based QI projects, residents were surveyed again. Results showed not only increased QI knowledge, but also improved patient safety and reduced waste.

“Keys to successful implementation included a thorough explanation of the need for this curriculum to the learners and ensuring that QI teams were multidisciplinary – residents, QI experts, nurses, techs, pharmacy, administrators, etc.,” said Dr. Cowdell.

For hospitalists in an academic setting, this work can provide a framework to incorporate QI into their residency programs. “I hope, if they have a passion for QI, they would seek out opportunities to mentor residents and help lead multidisciplinary team-based projects,” Dr. Cowdell said.

Reference

1. Cowdell, JC; Trautman, C; Lewis, M; Dawson, N. Integration of a Novel Quality Improvement Curriculum into an Internal Medicine Residency Program. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2018; April 8-11; Orlando, Fla. Abstract 54. https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/integration-of-a-novel-quality-improvement-curriculum-into-an-internal-medicine-residency-program/. Accessed Dec. 11, 2018.

For current and future hospitalists, there’s no doubt that knowledge of quality improvement (QI) fundamentals is an important component of a successful practice. One physician team set out to provide their trainees with that QI foundation and described the results.

“We believed that implementing a formal step-wise QI curriculum would not only meet the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements, but also increase residents’ knowledge of QI fundamentals and ultimately establish a culture of continuous improvement aiming to provide high-value care to our health care consumers,” said lead author J. Colt Cowdell, MD, MBA, of Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

Prior to any interventions, the team surveyed internal medicine residents regarding three unique patient scenarios and scored their answers. Residents were then assigned to one of five unique QI projects for the academic year in combination with a structured didactic QI curriculum.

After the structured progressive curriculum, in combination with team-based QI projects, residents were surveyed again. Results showed not only increased QI knowledge, but also improved patient safety and reduced waste.

“Keys to successful implementation included a thorough explanation of the need for this curriculum to the learners and ensuring that QI teams were multidisciplinary – residents, QI experts, nurses, techs, pharmacy, administrators, etc.,” said Dr. Cowdell.

For hospitalists in an academic setting, this work can provide a framework to incorporate QI into their residency programs. “I hope, if they have a passion for QI, they would seek out opportunities to mentor residents and help lead multidisciplinary team-based projects,” Dr. Cowdell said.

Reference

1. Cowdell, JC; Trautman, C; Lewis, M; Dawson, N. Integration of a Novel Quality Improvement Curriculum into an Internal Medicine Residency Program. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2018; April 8-11; Orlando, Fla. Abstract 54. https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/integration-of-a-novel-quality-improvement-curriculum-into-an-internal-medicine-residency-program/. Accessed Dec. 11, 2018.

Following the path of leadership

VA Hospitalist Dr. Matthew Tuck

For Matthew Tuck, MD, MEd, FACP, associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Washington, leadership is something that hospitalists can and should be learning at every opportunity.

Some of the best insights about effective leadership, teamwork, and process improvement come from the business world and have been slower to infiltrate into hospital settings and hospitalist groups, he says. But Dr. Tuck has tried to take advantage of numerous opportunities for leadership development in his own career.

He has been a hospitalist since 2010 and is part of a group of 13 physicians, all of whom carry clinical, teaching, and research responsibilities while pursuing a variety of education, quality improvement, and performance improvement topics.

“My chair has been generous about giving me time to do teaching and research and to pursue opportunities for career development,” he said. The Washington VAMC works with four affiliate medical schools in the area, and its six daily hospital medicine services are all 100% teaching services with assigned residents and interns.

Dr. Tuck divides his professional time roughly one-third each between clinical – seeing patients 5 months a year on a consultative or inpatient basis with resident teams; administrative in a variety of roles; and research. He has academic appointments at the George Washington University (GWU) School of Medicine and at the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md. He developed the coursework for teaching evidence-based medicine to first- and second-year medical students at GWU.

He is also part of a large research consortium with five sites and $7.5 million in funding over 5 years from NIH’s National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities to study how genetic information from African American patients can predict their response to cardiovascular medications. He serves as the study’s site Principal Investigator at the VAMC.

Opportunities to advance his leadership skills have included the VA’s Aspiring Leaders Program and Leadership Development Mentoring Program, which teach leadership skills on topical subjects such as teaching, communications skills, and finance. The Master Teacher Leadership Development Program for medical faculty at GWU, where he attended medical school and did his internship and residency, offers six intensive, classroom-based 8-week courses over a 1-year period. They cover various topical subjects with faculty from the business world teaching principles of leadership. The program includes a mentoring action plan for participants and leads to a graduate certificate in leadership development from GWU’s Graduate School of Education and Human Development at the end of the year’s studies.

Dr. Tuck credits completing this kind of coursework for his current position of leadership in the VA and he tries to share what he has learned with the medical students he teaches.

“When I was starting out as a physician, I never received training in how to lead a team. I found myself trying to get everything done for my patients while teaching my learners, and I really struggled for the first couple of years to manage these competing demands on my time,” he said.

Now, on the first day of a new clinical rotation, he meets one-on-one with his residents to set out goals and expectations. “I say: ‘This is how I want rounds to be run. What are your expectations?’ That way we make sure we’re collaborating as a team. I don’t know that medical school prepares you for this kind of teamwork. Unless you bring a background in business, you can really struggle.”

Interest in hospital medicine

“Throughout our medical training we do a variety of rotations and clerkships. I found myself falling in love with all of them – surgery, psychiatry, obstetrics, and gynecology,” Dr. Tuck explained, as he reflected on how he ended up in hospital medicine. “As someone who was interested in all of these different fields of medicine, I considered myself a true medical generalist. And in hospitalized patients, who struggle with all of the different issues that bring them to the hospital, I saw a compilation of all my experiences in residency training combined in one setting.”

Hospital medicine was a relatively young field at that time, with few academic hospitalists, he said. “But I had good mentors who encouraged me to pursue my educational, research, and administrative interests. My affinity for the VA was also largely due to my training. We worked in multiple settings – academic, community-based, National Institutes of Health, and at the VA.”

Dr. Tuck said that, of all the settings in which he practiced, he felt the VA truly trained him best to be a doctor. “The experience made me feel like a holistic practitioner,” he said. “The system allowed me to take the best care of my patients, since I didn’t have to worry about whether I could make needed referrals to specialists. Very early in my internship year we were seeing very sick patients with multiple comorbidities, but it was easy to get a social worker or case manager involved, compared to other settings, which can be more difficult to navigate.”

While the VA is a “great health system,” Dr. Tuck said, the challenge is learning how to work with its bureaucracy. “If you don’t know how the system works, it can seem to get in your way.” But overall, he said, the VA functions well and compares favorably with private sector hospitals and health systems. That was also the conclusion of a recent study in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, which compared the quality of outpatient and inpatient care in VA and non-VA settings using recent performance measure data.1 The authors concluded that the VA system performed similarly or better than non-VA health care on most nationally recognized measures of inpatient and outpatient care quality, although there is wide variation between VA facilities.

Working with the team

Another major interest for Dr. Tuck is team-based learning, which also grew out of his GWU leadership certificate course work on teaching teams and team development. He is working on a draft paper for publication with coauthor Patrick Rendon, MD, associate program director for the University of New Mexico’s internal medicine residency program, building on the group development stage theory – “Forming/Storming/Norming/Performing” – developed by Tuckman and Jenson.2

The theory offers 12 tips for optimizing inpatient ward team performance, such as getting the learners to buy in at an early stage of a project. “Everyone I talk to about our research is eager to learn how to apply these principles. I don’t think we’re unique at this center. We’re constantly rotating learners through the program. If you apply these principles, you can get learners to be more efficient starting from the first day,” he said.

The current inpatient team model at the Washington VAMC involves a broadly representative team from nursing, case management, social work, the business office, medical coding, utilization management, and administration that convenes every morning to discuss patient navigation and difficult discharges. “Everyone sits around a big table, and the six hospital medicine teams rotate through every fifteen minutes to review their patients’ admitting diagnoses, barriers to discharge and plans of care.”

At the patient’s bedside, a Focused Interdisciplinary Team (FIT) model, which Dr. Tuck helped to implement, incorporates a four-step process with clearly defined roles for the attending, nurse, pharmacist, and case manager or social worker. “Since implementation, our data show overall reductions in lengths of stay,” he said.

Dr. Tuck urges other hospitalists to pursue opportunities available to them to develop their leadership skills. “Look to your professional societies such as the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) or SHM.” For example, SGIM’s Academic Hospitalist Commission, which he cochairs, provides a voice on the national stage for academic hospitalists and cosponsors with SHM an annual Academic Hospitalist Academy to support career development for junior academic hospitalists as educational leaders. Since 2016, its Distinguished Professor of Hospital Medicine recognizes a professor of hospital medicine to give a plenary address at the SGIM national meeting.

SGIM’s SCHOLAR Project, a subgroup of its Academic Hospitalist Commission, has worked to identify features of successful academic hospitalist programs, with the results published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.3

“We learned that what sets successful programs apart is their leadership – as well as protected time for scholarly pursuits,” he said. “We’re all leaders in this field, whether we view ourselves that way or not.”

References

1. Price RA et al. Comparing quality of care in Veterans Affairs and Non–Veterans Affairs settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Oct;33(10):1631-38.

2. Tuckman B, Jensen M. Stages of small group development revisited. Group and Organizational Studies. 1977;2:419-427.

3. Seymann GB et al. Features of successful academic hospitalist programs: Insights from the SCHOLAR (Successful hospitalists in academics and research) project. J Hosp Med. 2016 Oct;11(10):708-13.

VA Hospitalist Dr. Matthew Tuck

VA Hospitalist Dr. Matthew Tuck

For Matthew Tuck, MD, MEd, FACP, associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Washington, leadership is something that hospitalists can and should be learning at every opportunity.

Some of the best insights about effective leadership, teamwork, and process improvement come from the business world and have been slower to infiltrate into hospital settings and hospitalist groups, he says. But Dr. Tuck has tried to take advantage of numerous opportunities for leadership development in his own career.

He has been a hospitalist since 2010 and is part of a group of 13 physicians, all of whom carry clinical, teaching, and research responsibilities while pursuing a variety of education, quality improvement, and performance improvement topics.

“My chair has been generous about giving me time to do teaching and research and to pursue opportunities for career development,” he said. The Washington VAMC works with four affiliate medical schools in the area, and its six daily hospital medicine services are all 100% teaching services with assigned residents and interns.

Dr. Tuck divides his professional time roughly one-third each between clinical – seeing patients 5 months a year on a consultative or inpatient basis with resident teams; administrative in a variety of roles; and research. He has academic appointments at the George Washington University (GWU) School of Medicine and at the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md. He developed the coursework for teaching evidence-based medicine to first- and second-year medical students at GWU.

He is also part of a large research consortium with five sites and $7.5 million in funding over 5 years from NIH’s National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities to study how genetic information from African American patients can predict their response to cardiovascular medications. He serves as the study’s site Principal Investigator at the VAMC.

Opportunities to advance his leadership skills have included the VA’s Aspiring Leaders Program and Leadership Development Mentoring Program, which teach leadership skills on topical subjects such as teaching, communications skills, and finance. The Master Teacher Leadership Development Program for medical faculty at GWU, where he attended medical school and did his internship and residency, offers six intensive, classroom-based 8-week courses over a 1-year period. They cover various topical subjects with faculty from the business world teaching principles of leadership. The program includes a mentoring action plan for participants and leads to a graduate certificate in leadership development from GWU’s Graduate School of Education and Human Development at the end of the year’s studies.

Dr. Tuck credits completing this kind of coursework for his current position of leadership in the VA and he tries to share what he has learned with the medical students he teaches.

“When I was starting out as a physician, I never received training in how to lead a team. I found myself trying to get everything done for my patients while teaching my learners, and I really struggled for the first couple of years to manage these competing demands on my time,” he said.

Now, on the first day of a new clinical rotation, he meets one-on-one with his residents to set out goals and expectations. “I say: ‘This is how I want rounds to be run. What are your expectations?’ That way we make sure we’re collaborating as a team. I don’t know that medical school prepares you for this kind of teamwork. Unless you bring a background in business, you can really struggle.”

Interest in hospital medicine

“Throughout our medical training we do a variety of rotations and clerkships. I found myself falling in love with all of them – surgery, psychiatry, obstetrics, and gynecology,” Dr. Tuck explained, as he reflected on how he ended up in hospital medicine. “As someone who was interested in all of these different fields of medicine, I considered myself a true medical generalist. And in hospitalized patients, who struggle with all of the different issues that bring them to the hospital, I saw a compilation of all my experiences in residency training combined in one setting.”

Hospital medicine was a relatively young field at that time, with few academic hospitalists, he said. “But I had good mentors who encouraged me to pursue my educational, research, and administrative interests. My affinity for the VA was also largely due to my training. We worked in multiple settings – academic, community-based, National Institutes of Health, and at the VA.”

Dr. Tuck said that, of all the settings in which he practiced, he felt the VA truly trained him best to be a doctor. “The experience made me feel like a holistic practitioner,” he said. “The system allowed me to take the best care of my patients, since I didn’t have to worry about whether I could make needed referrals to specialists. Very early in my internship year we were seeing very sick patients with multiple comorbidities, but it was easy to get a social worker or case manager involved, compared to other settings, which can be more difficult to navigate.”

While the VA is a “great health system,” Dr. Tuck said, the challenge is learning how to work with its bureaucracy. “If you don’t know how the system works, it can seem to get in your way.” But overall, he said, the VA functions well and compares favorably with private sector hospitals and health systems. That was also the conclusion of a recent study in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, which compared the quality of outpatient and inpatient care in VA and non-VA settings using recent performance measure data.1 The authors concluded that the VA system performed similarly or better than non-VA health care on most nationally recognized measures of inpatient and outpatient care quality, although there is wide variation between VA facilities.

Working with the team

Another major interest for Dr. Tuck is team-based learning, which also grew out of his GWU leadership certificate course work on teaching teams and team development. He is working on a draft paper for publication with coauthor Patrick Rendon, MD, associate program director for the University of New Mexico’s internal medicine residency program, building on the group development stage theory – “Forming/Storming/Norming/Performing” – developed by Tuckman and Jenson.2

The theory offers 12 tips for optimizing inpatient ward team performance, such as getting the learners to buy in at an early stage of a project. “Everyone I talk to about our research is eager to learn how to apply these principles. I don’t think we’re unique at this center. We’re constantly rotating learners through the program. If you apply these principles, you can get learners to be more efficient starting from the first day,” he said.

The current inpatient team model at the Washington VAMC involves a broadly representative team from nursing, case management, social work, the business office, medical coding, utilization management, and administration that convenes every morning to discuss patient navigation and difficult discharges. “Everyone sits around a big table, and the six hospital medicine teams rotate through every fifteen minutes to review their patients’ admitting diagnoses, barriers to discharge and plans of care.”

At the patient’s bedside, a Focused Interdisciplinary Team (FIT) model, which Dr. Tuck helped to implement, incorporates a four-step process with clearly defined roles for the attending, nurse, pharmacist, and case manager or social worker. “Since implementation, our data show overall reductions in lengths of stay,” he said.

Dr. Tuck urges other hospitalists to pursue opportunities available to them to develop their leadership skills. “Look to your professional societies such as the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) or SHM.” For example, SGIM’s Academic Hospitalist Commission, which he cochairs, provides a voice on the national stage for academic hospitalists and cosponsors with SHM an annual Academic Hospitalist Academy to support career development for junior academic hospitalists as educational leaders. Since 2016, its Distinguished Professor of Hospital Medicine recognizes a professor of hospital medicine to give a plenary address at the SGIM national meeting.

SGIM’s SCHOLAR Project, a subgroup of its Academic Hospitalist Commission, has worked to identify features of successful academic hospitalist programs, with the results published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.3

“We learned that what sets successful programs apart is their leadership – as well as protected time for scholarly pursuits,” he said. “We’re all leaders in this field, whether we view ourselves that way or not.”

References

1. Price RA et al. Comparing quality of care in Veterans Affairs and Non–Veterans Affairs settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Oct;33(10):1631-38.

2. Tuckman B, Jensen M. Stages of small group development revisited. Group and Organizational Studies. 1977;2:419-427.

3. Seymann GB et al. Features of successful academic hospitalist programs: Insights from the SCHOLAR (Successful hospitalists in academics and research) project. J Hosp Med. 2016 Oct;11(10):708-13.

For Matthew Tuck, MD, MEd, FACP, associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Washington, leadership is something that hospitalists can and should be learning at every opportunity.

Some of the best insights about effective leadership, teamwork, and process improvement come from the business world and have been slower to infiltrate into hospital settings and hospitalist groups, he says. But Dr. Tuck has tried to take advantage of numerous opportunities for leadership development in his own career.

He has been a hospitalist since 2010 and is part of a group of 13 physicians, all of whom carry clinical, teaching, and research responsibilities while pursuing a variety of education, quality improvement, and performance improvement topics.