User login

Does Combination ACEi/ARB Therapy Benefit Patients With Proteinuria?

Q: I have a diabetic patient with microscopic proteinuria. I put her on an ACE inhibitor, but she still has the same albumin–creatinine ratio. My supervising physician suggested I add an ARB to her regimen, but I seem to remember reading that this does not work. Is that true? Or should I prescribe an ACE inhibitor/ARB combination?

This is a common question, but there is no consensus regarding the correct answer. The question should be: Are two drugs better than one when it comes to reducing proteinuria and progression to end-stage renal disease? Researchers have demonstrated a decrease in proteinuria in patients given combination ACE inhibitor/angiotension receptor blocker (ARB) therapy; however, the studies involved were found to have flaws, including small sample sizes and relatively short follow-up, once treatment was initiated.1,2

A larger study, known as Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET),3,4 is a multiyear study with more than 25,000 patients enrolled. ONTARGET (which excludes patients with heart failure) addresses the question of whether an ACE inhibitor in combination with an ARB, or either agent alone, is more effective in the reduction of proteinuria. In ONTARGET, combination therapy was associated with a decrease in proteinuria; however, the incidence of renal impairment was much higher.3

ONTARGET was the first trial to cast doubt on the belief that proteinuria is an accurate marker for progressive renal dysfunction. Combination treatment led to an advanced risk for increased serum creatinine and need for dialysis, despite the reduction in proteinuria. Further, combination therapy was more likely than either agent alone to cause adverse effects, including hypotension and hyperkalemia.3,4

Finally, the study also demonstrated that ACE inhibitors are not superior to ARBs. Both drugs reduce proteinuria, and each one taken alone decreases progression to end-stage renal disease. Therefore, the conclusion is that either an ACE inhibitor or an ARB alone is more efficacious than the two drugs combined.

Tricia A. Howard, MHS, PA-C, South University PA Program, Tampa, FL

References

1. Misra S, Stevermer JJ. ACE inhibitors and ARBs: one or the other—not both—for high-risk patients. J Fam Pract. 2009;58:24-26.

2. Jennings DL, Kalus JS, Coleman CI, et al. Combination therapy with an ACE inhibitor and an angiotensin receptor blocker for diabetic nephropathy: a meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2007;24:486-493.

3. Mann JF, Schmieder RE, McQueen M, et al; ONTARGET investigators. Renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:547-553.

4. Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al; ONTARGET Investigators. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1547-1559.

Q: I have a diabetic patient with microscopic proteinuria. I put her on an ACE inhibitor, but she still has the same albumin–creatinine ratio. My supervising physician suggested I add an ARB to her regimen, but I seem to remember reading that this does not work. Is that true? Or should I prescribe an ACE inhibitor/ARB combination?

This is a common question, but there is no consensus regarding the correct answer. The question should be: Are two drugs better than one when it comes to reducing proteinuria and progression to end-stage renal disease? Researchers have demonstrated a decrease in proteinuria in patients given combination ACE inhibitor/angiotension receptor blocker (ARB) therapy; however, the studies involved were found to have flaws, including small sample sizes and relatively short follow-up, once treatment was initiated.1,2

A larger study, known as Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET),3,4 is a multiyear study with more than 25,000 patients enrolled. ONTARGET (which excludes patients with heart failure) addresses the question of whether an ACE inhibitor in combination with an ARB, or either agent alone, is more effective in the reduction of proteinuria. In ONTARGET, combination therapy was associated with a decrease in proteinuria; however, the incidence of renal impairment was much higher.3

ONTARGET was the first trial to cast doubt on the belief that proteinuria is an accurate marker for progressive renal dysfunction. Combination treatment led to an advanced risk for increased serum creatinine and need for dialysis, despite the reduction in proteinuria. Further, combination therapy was more likely than either agent alone to cause adverse effects, including hypotension and hyperkalemia.3,4

Finally, the study also demonstrated that ACE inhibitors are not superior to ARBs. Both drugs reduce proteinuria, and each one taken alone decreases progression to end-stage renal disease. Therefore, the conclusion is that either an ACE inhibitor or an ARB alone is more efficacious than the two drugs combined.

Tricia A. Howard, MHS, PA-C, South University PA Program, Tampa, FL

References

1. Misra S, Stevermer JJ. ACE inhibitors and ARBs: one or the other—not both—for high-risk patients. J Fam Pract. 2009;58:24-26.

2. Jennings DL, Kalus JS, Coleman CI, et al. Combination therapy with an ACE inhibitor and an angiotensin receptor blocker for diabetic nephropathy: a meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2007;24:486-493.

3. Mann JF, Schmieder RE, McQueen M, et al; ONTARGET investigators. Renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:547-553.

4. Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al; ONTARGET Investigators. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1547-1559.

Q: I have a diabetic patient with microscopic proteinuria. I put her on an ACE inhibitor, but she still has the same albumin–creatinine ratio. My supervising physician suggested I add an ARB to her regimen, but I seem to remember reading that this does not work. Is that true? Or should I prescribe an ACE inhibitor/ARB combination?

This is a common question, but there is no consensus regarding the correct answer. The question should be: Are two drugs better than one when it comes to reducing proteinuria and progression to end-stage renal disease? Researchers have demonstrated a decrease in proteinuria in patients given combination ACE inhibitor/angiotension receptor blocker (ARB) therapy; however, the studies involved were found to have flaws, including small sample sizes and relatively short follow-up, once treatment was initiated.1,2

A larger study, known as Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET),3,4 is a multiyear study with more than 25,000 patients enrolled. ONTARGET (which excludes patients with heart failure) addresses the question of whether an ACE inhibitor in combination with an ARB, or either agent alone, is more effective in the reduction of proteinuria. In ONTARGET, combination therapy was associated with a decrease in proteinuria; however, the incidence of renal impairment was much higher.3

ONTARGET was the first trial to cast doubt on the belief that proteinuria is an accurate marker for progressive renal dysfunction. Combination treatment led to an advanced risk for increased serum creatinine and need for dialysis, despite the reduction in proteinuria. Further, combination therapy was more likely than either agent alone to cause adverse effects, including hypotension and hyperkalemia.3,4

Finally, the study also demonstrated that ACE inhibitors are not superior to ARBs. Both drugs reduce proteinuria, and each one taken alone decreases progression to end-stage renal disease. Therefore, the conclusion is that either an ACE inhibitor or an ARB alone is more efficacious than the two drugs combined.

Tricia A. Howard, MHS, PA-C, South University PA Program, Tampa, FL

References

1. Misra S, Stevermer JJ. ACE inhibitors and ARBs: one or the other—not both—for high-risk patients. J Fam Pract. 2009;58:24-26.

2. Jennings DL, Kalus JS, Coleman CI, et al. Combination therapy with an ACE inhibitor and an angiotensin receptor blocker for diabetic nephropathy: a meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2007;24:486-493.

3. Mann JF, Schmieder RE, McQueen M, et al; ONTARGET investigators. Renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:547-553.

4. Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al; ONTARGET Investigators. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1547-1559.

A Reader Asks About Wild Ginger

Q: A friend of my teenage daughter was telling her about a new, “natural” weight-loss medication that contains wild ginger. Besides the obvious (a teen should not be taking “drugs” to lose weight), I seem to remember a problem with wild ginger. Is this substance dangerous?

A source of the herbal drug aristolochic acid (AA), wild ginger is a plant in the birthwort family. Its common name may be explained by the fact that it smells and tastes somewhat like ginger. However, wild ginger is not related to the common herb, ginger, that is found in the grocery store.

After multiple incidents of acute kidney failure in Europe, China, India, and the Balkans were linked to AA, the FDA sent out warning letters in 2001.5 However, as the saying goes, what goes around, comes around. A new wave of “natural” weight-loss remedies containing AA has become available for sale to unsuspecting consumers over the Internet.

Wild ginger plants grow in temperate regions, with a kidney-shaped leaf—ironic, since ingesting this substance can induce kidney failure. In an article published in 2012, researchers reported that a Chinese company had replaced Stephania tetrandra with Aristolochia fangchi in their weight-loss formula, resulting in multiple incidents of kidney failure.6 In 2013, investigators from London and Germany showed that products containing AA were commonly available online.7

Symptoms of AA ingestion include acute kidney failure with normal blood pressure; a normochromic, normocytic anemia with a moderate amount of urine protein excretion (< 1.5 g/d); and urine sediment with a few red blood cells. The serum creatininehas been reported anywhere from 1.4 to 12.7 mg/dL on presentation,7 but due to AA-associated reductions in fluid and food intake (ie, its “weight-loss” component), this can quickly progress to kidney failure.

Discontinuing use of the herbal remedy does not appear to stop users’ progression to kidney failure, as damage to the interstitial cells is already done by the time of presentation.

AA use is also associated with an increased incidence of both kidney cancer and urinary cancer. Quite a high-risk “natural” herbal remedy!

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA,Department Co-editor

References

5. Boyle B. FDA warns consumers to discontinue use of botanical products that contain aristolochic acid (2001). www.hcvadvocate.org/news/NewsUpdates_pdf/2.1.1.2_News_Review_Archive_2001/aristocholic.pdf. Accessed April 5, 2013.

6. Asif M. A brief study of toxic effects of some medicinal herbs on kidney. Adv Biomed Res. 2012;1:44.

7. Gökmen MR, Cosyns JP, Arlt VM, et al. The epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of aristolochic acid nephropathy: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:469-477.

Q: A friend of my teenage daughter was telling her about a new, “natural” weight-loss medication that contains wild ginger. Besides the obvious (a teen should not be taking “drugs” to lose weight), I seem to remember a problem with wild ginger. Is this substance dangerous?

A source of the herbal drug aristolochic acid (AA), wild ginger is a plant in the birthwort family. Its common name may be explained by the fact that it smells and tastes somewhat like ginger. However, wild ginger is not related to the common herb, ginger, that is found in the grocery store.

After multiple incidents of acute kidney failure in Europe, China, India, and the Balkans were linked to AA, the FDA sent out warning letters in 2001.5 However, as the saying goes, what goes around, comes around. A new wave of “natural” weight-loss remedies containing AA has become available for sale to unsuspecting consumers over the Internet.

Wild ginger plants grow in temperate regions, with a kidney-shaped leaf—ironic, since ingesting this substance can induce kidney failure. In an article published in 2012, researchers reported that a Chinese company had replaced Stephania tetrandra with Aristolochia fangchi in their weight-loss formula, resulting in multiple incidents of kidney failure.6 In 2013, investigators from London and Germany showed that products containing AA were commonly available online.7

Symptoms of AA ingestion include acute kidney failure with normal blood pressure; a normochromic, normocytic anemia with a moderate amount of urine protein excretion (< 1.5 g/d); and urine sediment with a few red blood cells. The serum creatininehas been reported anywhere from 1.4 to 12.7 mg/dL on presentation,7 but due to AA-associated reductions in fluid and food intake (ie, its “weight-loss” component), this can quickly progress to kidney failure.

Discontinuing use of the herbal remedy does not appear to stop users’ progression to kidney failure, as damage to the interstitial cells is already done by the time of presentation.

AA use is also associated with an increased incidence of both kidney cancer and urinary cancer. Quite a high-risk “natural” herbal remedy!

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA,Department Co-editor

References

5. Boyle B. FDA warns consumers to discontinue use of botanical products that contain aristolochic acid (2001). www.hcvadvocate.org/news/NewsUpdates_pdf/2.1.1.2_News_Review_Archive_2001/aristocholic.pdf. Accessed April 5, 2013.

6. Asif M. A brief study of toxic effects of some medicinal herbs on kidney. Adv Biomed Res. 2012;1:44.

7. Gökmen MR, Cosyns JP, Arlt VM, et al. The epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of aristolochic acid nephropathy: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:469-477.

Q: A friend of my teenage daughter was telling her about a new, “natural” weight-loss medication that contains wild ginger. Besides the obvious (a teen should not be taking “drugs” to lose weight), I seem to remember a problem with wild ginger. Is this substance dangerous?

A source of the herbal drug aristolochic acid (AA), wild ginger is a plant in the birthwort family. Its common name may be explained by the fact that it smells and tastes somewhat like ginger. However, wild ginger is not related to the common herb, ginger, that is found in the grocery store.

After multiple incidents of acute kidney failure in Europe, China, India, and the Balkans were linked to AA, the FDA sent out warning letters in 2001.5 However, as the saying goes, what goes around, comes around. A new wave of “natural” weight-loss remedies containing AA has become available for sale to unsuspecting consumers over the Internet.

Wild ginger plants grow in temperate regions, with a kidney-shaped leaf—ironic, since ingesting this substance can induce kidney failure. In an article published in 2012, researchers reported that a Chinese company had replaced Stephania tetrandra with Aristolochia fangchi in their weight-loss formula, resulting in multiple incidents of kidney failure.6 In 2013, investigators from London and Germany showed that products containing AA were commonly available online.7

Symptoms of AA ingestion include acute kidney failure with normal blood pressure; a normochromic, normocytic anemia with a moderate amount of urine protein excretion (< 1.5 g/d); and urine sediment with a few red blood cells. The serum creatininehas been reported anywhere from 1.4 to 12.7 mg/dL on presentation,7 but due to AA-associated reductions in fluid and food intake (ie, its “weight-loss” component), this can quickly progress to kidney failure.

Discontinuing use of the herbal remedy does not appear to stop users’ progression to kidney failure, as damage to the interstitial cells is already done by the time of presentation.

AA use is also associated with an increased incidence of both kidney cancer and urinary cancer. Quite a high-risk “natural” herbal remedy!

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA,Department Co-editor

References

5. Boyle B. FDA warns consumers to discontinue use of botanical products that contain aristolochic acid (2001). www.hcvadvocate.org/news/NewsUpdates_pdf/2.1.1.2_News_Review_Archive_2001/aristocholic.pdf. Accessed April 5, 2013.

6. Asif M. A brief study of toxic effects of some medicinal herbs on kidney. Adv Biomed Res. 2012;1:44.

7. Gökmen MR, Cosyns JP, Arlt VM, et al. The epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of aristolochic acid nephropathy: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:469-477.

Acute Kidney Injury in the ICU: Medication Dosing

Q: As a hospitalist, I often see patients in our ICU develop AKI. Our pharmacist helps us with medication dosing, but sometimes I feel as if we're pulling a dose out of the air. Are there any studies or guidelines we can refer to?

Standard medication dosing adjustments for patients with impaired renal function are generally based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Because SCr is a lagging indicator of AKI, all methods of deriving eGFR from SCr are valid only when the patient is in a steady state.10

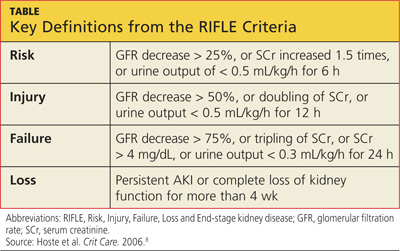

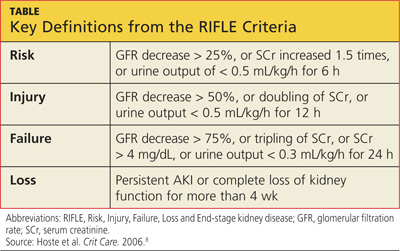

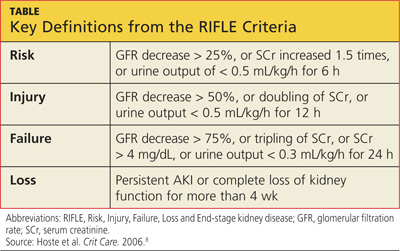

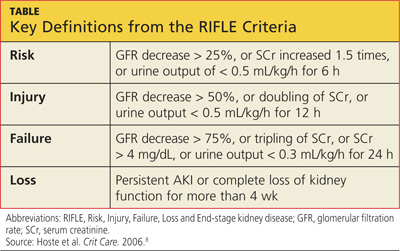

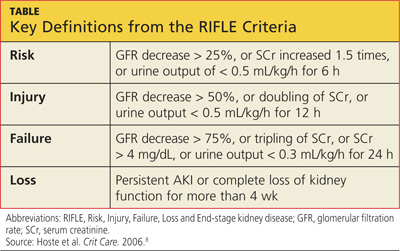

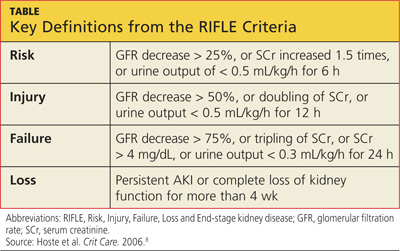

SCr has yet to be replaced by a real-time biomarker for AKI; this has left clinicians in the ICU setting with no simple or concise method for real-time assessment of renal function. In response to this common clinical conundrum, the RIFLE criteria,8 mentioned above, incorporates urinary output and relative increase in SCr as assessment criteria (see table for definitions).

This revised classification system may help the clinician define the severity of AKI in the acute setting. However, no medication dosing guidelines currently correspond with RIFLE staging. To further complicate the picture, there is evidence to suggest that AKI may affect drug metabolism through nonrenal pathways, such as hepatic clearance and transport functions.11 Add to this the potential for impaired drug absorption, distribution, and/or clearance due to variance in intravascular volume status, hepatic hypoperfusion, hypoxia, decreased protein synthesis, and competitive inhibition from concomitant medications—in short, the variables become too complex for calculating therapeutic drug dosing to be possible.

In the absence of definitive guidelines, the clinician plays a critical role in medication dosing adjustment for the ICU patient with AKI. The clinician must use astute clinical judgment to assess and prioritize the unique constellation of factors in any given case. Some of the factors that should be carefully considered when estimating medication dose adjustments in this context include RIFLE staging, trend in SCr, baseline SCr, nephrotoxicity of the medication to be administered, the drug's volume of distribution, the metabolic pathways of drug excretion, and the patient's weight.

A serum drug level, when available, is generally the best guide for dosing adjustment.10 The RIFLE staging does offer some clinical pearls that may be helpful. Though not evidence-based recommendations, these guides are commonly used in the clinical environment.

When patients are in the Failure stage, for example (see specifics in the table), they are generally considered to have an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min for purposes of drug dose adjustment (personal communication, Gideon Kayanan, PharmD, February 2013). However, patients in this category are much more likely than others to be undergoing dialysis, in which case the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are further complicated. In some cases, it may be appropriate to order creatinine clearance studies with a 6- or 12-hour urine collection and extrapolate a 24-hour creatinine clearance from this value.

The dearth of literature addressing this topic (despite the prevalence of AKI in the acute care setting) is a clear indication of the complexity of creating guidelines to address such a dynamic, multivariate pharmacokinetic process. Review of the literature clearly demonstrates that medical science in this area is not yet sufficiently developed to produce a standardized, data-driven guideline for dose adjustment calculation in patients with AKI.10 Until biomarkers are detected that offer real-time assessment of renal function and that can be used in the clinical setting, there will continue to be a component of estimation, analysis of trends, and reliance on clinical judgment in adjusting medication doses for inpatients with AKI. —AC

References

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2010 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2010/view/default.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2011 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2011/view/v2_00_appx.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

3. Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:844-861.

4. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, et al. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365-3370.

5. Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, et al. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;24:37-42.

6. Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:349-355.

7. Nisula S, Kaukonen KM, Vaara ST, et al. Incidence, risk factors and 90-day mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in Finnish intensive care units: the FINNAKI study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:420-428.

8. Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R73.

9. Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, et al. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:961-973.

10. Matzke GR, Aronoff GR, Atkinson AJ Jr, et al. Drug dosing consideration in patients with acute and chronic kidney disease: a clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011;80:1122-1137.

11. Vilay AM, Churchwell MD, Mueller BA. Clinical review: drug metabolism and nonrenal clearance in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:235.

Q: As a hospitalist, I often see patients in our ICU develop AKI. Our pharmacist helps us with medication dosing, but sometimes I feel as if we're pulling a dose out of the air. Are there any studies or guidelines we can refer to?

Standard medication dosing adjustments for patients with impaired renal function are generally based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Because SCr is a lagging indicator of AKI, all methods of deriving eGFR from SCr are valid only when the patient is in a steady state.10

SCr has yet to be replaced by a real-time biomarker for AKI; this has left clinicians in the ICU setting with no simple or concise method for real-time assessment of renal function. In response to this common clinical conundrum, the RIFLE criteria,8 mentioned above, incorporates urinary output and relative increase in SCr as assessment criteria (see table for definitions).

This revised classification system may help the clinician define the severity of AKI in the acute setting. However, no medication dosing guidelines currently correspond with RIFLE staging. To further complicate the picture, there is evidence to suggest that AKI may affect drug metabolism through nonrenal pathways, such as hepatic clearance and transport functions.11 Add to this the potential for impaired drug absorption, distribution, and/or clearance due to variance in intravascular volume status, hepatic hypoperfusion, hypoxia, decreased protein synthesis, and competitive inhibition from concomitant medications—in short, the variables become too complex for calculating therapeutic drug dosing to be possible.

In the absence of definitive guidelines, the clinician plays a critical role in medication dosing adjustment for the ICU patient with AKI. The clinician must use astute clinical judgment to assess and prioritize the unique constellation of factors in any given case. Some of the factors that should be carefully considered when estimating medication dose adjustments in this context include RIFLE staging, trend in SCr, baseline SCr, nephrotoxicity of the medication to be administered, the drug's volume of distribution, the metabolic pathways of drug excretion, and the patient's weight.

A serum drug level, when available, is generally the best guide for dosing adjustment.10 The RIFLE staging does offer some clinical pearls that may be helpful. Though not evidence-based recommendations, these guides are commonly used in the clinical environment.

When patients are in the Failure stage, for example (see specifics in the table), they are generally considered to have an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min for purposes of drug dose adjustment (personal communication, Gideon Kayanan, PharmD, February 2013). However, patients in this category are much more likely than others to be undergoing dialysis, in which case the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are further complicated. In some cases, it may be appropriate to order creatinine clearance studies with a 6- or 12-hour urine collection and extrapolate a 24-hour creatinine clearance from this value.

The dearth of literature addressing this topic (despite the prevalence of AKI in the acute care setting) is a clear indication of the complexity of creating guidelines to address such a dynamic, multivariate pharmacokinetic process. Review of the literature clearly demonstrates that medical science in this area is not yet sufficiently developed to produce a standardized, data-driven guideline for dose adjustment calculation in patients with AKI.10 Until biomarkers are detected that offer real-time assessment of renal function and that can be used in the clinical setting, there will continue to be a component of estimation, analysis of trends, and reliance on clinical judgment in adjusting medication doses for inpatients with AKI. —AC

References

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2010 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2010/view/default.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2011 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2011/view/v2_00_appx.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

3. Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:844-861.

4. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, et al. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365-3370.

5. Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, et al. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;24:37-42.

6. Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:349-355.

7. Nisula S, Kaukonen KM, Vaara ST, et al. Incidence, risk factors and 90-day mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in Finnish intensive care units: the FINNAKI study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:420-428.

8. Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R73.

9. Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, et al. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:961-973.

10. Matzke GR, Aronoff GR, Atkinson AJ Jr, et al. Drug dosing consideration in patients with acute and chronic kidney disease: a clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011;80:1122-1137.

11. Vilay AM, Churchwell MD, Mueller BA. Clinical review: drug metabolism and nonrenal clearance in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:235.

Q: As a hospitalist, I often see patients in our ICU develop AKI. Our pharmacist helps us with medication dosing, but sometimes I feel as if we're pulling a dose out of the air. Are there any studies or guidelines we can refer to?

Standard medication dosing adjustments for patients with impaired renal function are generally based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Because SCr is a lagging indicator of AKI, all methods of deriving eGFR from SCr are valid only when the patient is in a steady state.10

SCr has yet to be replaced by a real-time biomarker for AKI; this has left clinicians in the ICU setting with no simple or concise method for real-time assessment of renal function. In response to this common clinical conundrum, the RIFLE criteria,8 mentioned above, incorporates urinary output and relative increase in SCr as assessment criteria (see table for definitions).

This revised classification system may help the clinician define the severity of AKI in the acute setting. However, no medication dosing guidelines currently correspond with RIFLE staging. To further complicate the picture, there is evidence to suggest that AKI may affect drug metabolism through nonrenal pathways, such as hepatic clearance and transport functions.11 Add to this the potential for impaired drug absorption, distribution, and/or clearance due to variance in intravascular volume status, hepatic hypoperfusion, hypoxia, decreased protein synthesis, and competitive inhibition from concomitant medications—in short, the variables become too complex for calculating therapeutic drug dosing to be possible.

In the absence of definitive guidelines, the clinician plays a critical role in medication dosing adjustment for the ICU patient with AKI. The clinician must use astute clinical judgment to assess and prioritize the unique constellation of factors in any given case. Some of the factors that should be carefully considered when estimating medication dose adjustments in this context include RIFLE staging, trend in SCr, baseline SCr, nephrotoxicity of the medication to be administered, the drug's volume of distribution, the metabolic pathways of drug excretion, and the patient's weight.

A serum drug level, when available, is generally the best guide for dosing adjustment.10 The RIFLE staging does offer some clinical pearls that may be helpful. Though not evidence-based recommendations, these guides are commonly used in the clinical environment.

When patients are in the Failure stage, for example (see specifics in the table), they are generally considered to have an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min for purposes of drug dose adjustment (personal communication, Gideon Kayanan, PharmD, February 2013). However, patients in this category are much more likely than others to be undergoing dialysis, in which case the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are further complicated. In some cases, it may be appropriate to order creatinine clearance studies with a 6- or 12-hour urine collection and extrapolate a 24-hour creatinine clearance from this value.

The dearth of literature addressing this topic (despite the prevalence of AKI in the acute care setting) is a clear indication of the complexity of creating guidelines to address such a dynamic, multivariate pharmacokinetic process. Review of the literature clearly demonstrates that medical science in this area is not yet sufficiently developed to produce a standardized, data-driven guideline for dose adjustment calculation in patients with AKI.10 Until biomarkers are detected that offer real-time assessment of renal function and that can be used in the clinical setting, there will continue to be a component of estimation, analysis of trends, and reliance on clinical judgment in adjusting medication doses for inpatients with AKI. —AC

References

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2010 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2010/view/default.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2011 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2011/view/v2_00_appx.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

3. Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:844-861.

4. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, et al. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365-3370.

5. Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, et al. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;24:37-42.

6. Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:349-355.

7. Nisula S, Kaukonen KM, Vaara ST, et al. Incidence, risk factors and 90-day mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in Finnish intensive care units: the FINNAKI study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:420-428.

8. Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R73.

9. Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, et al. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:961-973.

10. Matzke GR, Aronoff GR, Atkinson AJ Jr, et al. Drug dosing consideration in patients with acute and chronic kidney disease: a clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011;80:1122-1137.

11. Vilay AM, Churchwell MD, Mueller BA. Clinical review: drug metabolism and nonrenal clearance in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:235.

Acute Kidney Injury in the ICU: Increasing Prevalence

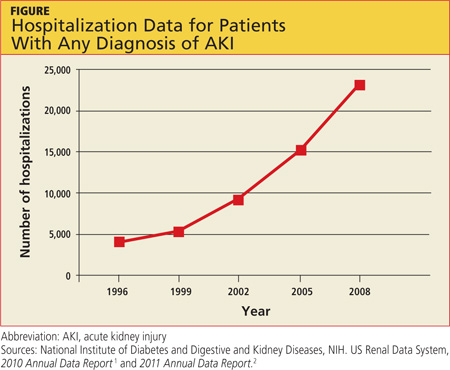

Q: In 10 years as a hospitalist advanced practitioner, I've been seeing more and more AKI in our ICU. Is this true everywhere, or are we doing something wrong?

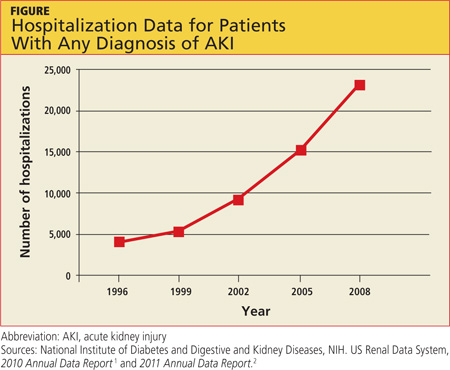

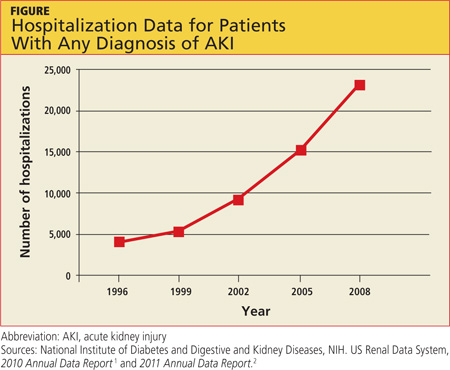

AKI is on the rise nationwide (see hospitalization data in figure), and it carries grim implications for patient outcomes.1-3 AKI with a rise in serum creatinine (SCr) as modest as 0.3 mg/dL is associated with a 70% increase in mortality risk. A rise in SCr exceeding 0.5 mg/dL has been associated with a 6.5-fold rise in the risk for death, even when adjusted for age and gender.4 This is higher than the mortality rate for inpatients admitted with cardiovascular disease or cancer, and just slightly more favorable than the mortality risk associated with sepsis (odds ratios, 6.6 and 7.5, respectively). AKI management in the non-ICU setting incurs the third highest median direct hospital cost, after acute MI and stroke.3

A recent retrospective analysis of hospital admissions nationwide from 2000 to 2009 shows a 10% annual increase in the incidence of AKI requiring dialysis, with at least doubling of the incidence and the number of deaths during that 10-year time period.5 Analyzing the incidence of AKI not requiring dialysis over time is more challenging because the criteria to define AKI have not been static; however, the rise in AKI requiring dialysis has mirrored the rise in AKI not requiring dialysis—suggesting that there is in fact an increased incidence of AKI, independent of variability in the defining criteria.3

Researchers reported in 2012 that during the previous year, the incidence of AKI among all hospitalized patients was 1 in 5.6 In the ICU, incidence of AKI has been reported at 39%, with a mortality rate of 25%.7 Based on the RIFLE criteria (a recently revised classification system whose name refers to Risk, Injury, Failure; Loss and End-stage kidney disease),8 as many as two-thirds of patients admitted to the ICU meet criteria for a diagnosis of AKI.

Predictors for AKI include advancing age, baseline SCr below 1.2 mg/dL, the presence of diabetes, use of IV contrast, acute coronary syndromes, sepsis, liver or heart failure, and use of nephrotoxic medications.3

It is important for clinicians to recognize the implications of AKI, even when it manifests as a relatively minor rise in SCr. In addition to its association with poor outcomes in hospitalized patients, AKI increases the risk for chronic kidney disease and for readmissions within six months after hospital discharge.9 Unfortunately, our increased awareness of the implications of AKI in the inpatient setting has yet to translate into significant improvement in outcomes.

The evolution and availability of epidemiologic and outcome data, we can only hope, will serve to direct more resources and further study toward this issue. Clinicians' efforts to prevent and treat AKI can have profound implications for many of our nation's most chronically and critically ill patients. —AC

REFERENCES

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2010 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2010/view/default.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2011 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2011/view/v2_00_appx.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

3. Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:844-861.

4. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, et al. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365-3370.

5. Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, et al. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;24:37-42.

6. Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:349-355.

7. Nisula S, Kaukonen KM, Vaara ST, et al. Incidence, risk factors and 90-day mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in Finnish intensive care units: the FINNAKI study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:420-428.

8. Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R73.

9. Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, et al. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:961-973.

10. Matzke GR, Aronoff GR, Atkinson AJ Jr, et al. Drug dosing consideration in patients with acute and chronic kidney disease: a clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011;80:1122-1137.

11. Vilay AM, Churchwell MD, Mueller BA. Clinical review: drug metabolism and nonrenal clearance in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:235.

Q: In 10 years as a hospitalist advanced practitioner, I've been seeing more and more AKI in our ICU. Is this true everywhere, or are we doing something wrong?

AKI is on the rise nationwide (see hospitalization data in figure), and it carries grim implications for patient outcomes.1-3 AKI with a rise in serum creatinine (SCr) as modest as 0.3 mg/dL is associated with a 70% increase in mortality risk. A rise in SCr exceeding 0.5 mg/dL has been associated with a 6.5-fold rise in the risk for death, even when adjusted for age and gender.4 This is higher than the mortality rate for inpatients admitted with cardiovascular disease or cancer, and just slightly more favorable than the mortality risk associated with sepsis (odds ratios, 6.6 and 7.5, respectively). AKI management in the non-ICU setting incurs the third highest median direct hospital cost, after acute MI and stroke.3

A recent retrospective analysis of hospital admissions nationwide from 2000 to 2009 shows a 10% annual increase in the incidence of AKI requiring dialysis, with at least doubling of the incidence and the number of deaths during that 10-year time period.5 Analyzing the incidence of AKI not requiring dialysis over time is more challenging because the criteria to define AKI have not been static; however, the rise in AKI requiring dialysis has mirrored the rise in AKI not requiring dialysis—suggesting that there is in fact an increased incidence of AKI, independent of variability in the defining criteria.3

Researchers reported in 2012 that during the previous year, the incidence of AKI among all hospitalized patients was 1 in 5.6 In the ICU, incidence of AKI has been reported at 39%, with a mortality rate of 25%.7 Based on the RIFLE criteria (a recently revised classification system whose name refers to Risk, Injury, Failure; Loss and End-stage kidney disease),8 as many as two-thirds of patients admitted to the ICU meet criteria for a diagnosis of AKI.

Predictors for AKI include advancing age, baseline SCr below 1.2 mg/dL, the presence of diabetes, use of IV contrast, acute coronary syndromes, sepsis, liver or heart failure, and use of nephrotoxic medications.3

It is important for clinicians to recognize the implications of AKI, even when it manifests as a relatively minor rise in SCr. In addition to its association with poor outcomes in hospitalized patients, AKI increases the risk for chronic kidney disease and for readmissions within six months after hospital discharge.9 Unfortunately, our increased awareness of the implications of AKI in the inpatient setting has yet to translate into significant improvement in outcomes.

The evolution and availability of epidemiologic and outcome data, we can only hope, will serve to direct more resources and further study toward this issue. Clinicians' efforts to prevent and treat AKI can have profound implications for many of our nation's most chronically and critically ill patients. —AC

REFERENCES

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2010 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2010/view/default.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2011 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2011/view/v2_00_appx.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

3. Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:844-861.

4. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, et al. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365-3370.

5. Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, et al. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;24:37-42.

6. Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:349-355.

7. Nisula S, Kaukonen KM, Vaara ST, et al. Incidence, risk factors and 90-day mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in Finnish intensive care units: the FINNAKI study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:420-428.

8. Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R73.

9. Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, et al. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:961-973.

10. Matzke GR, Aronoff GR, Atkinson AJ Jr, et al. Drug dosing consideration in patients with acute and chronic kidney disease: a clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011;80:1122-1137.

11. Vilay AM, Churchwell MD, Mueller BA. Clinical review: drug metabolism and nonrenal clearance in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:235.

Q: In 10 years as a hospitalist advanced practitioner, I've been seeing more and more AKI in our ICU. Is this true everywhere, or are we doing something wrong?

AKI is on the rise nationwide (see hospitalization data in figure), and it carries grim implications for patient outcomes.1-3 AKI with a rise in serum creatinine (SCr) as modest as 0.3 mg/dL is associated with a 70% increase in mortality risk. A rise in SCr exceeding 0.5 mg/dL has been associated with a 6.5-fold rise in the risk for death, even when adjusted for age and gender.4 This is higher than the mortality rate for inpatients admitted with cardiovascular disease or cancer, and just slightly more favorable than the mortality risk associated with sepsis (odds ratios, 6.6 and 7.5, respectively). AKI management in the non-ICU setting incurs the third highest median direct hospital cost, after acute MI and stroke.3

A recent retrospective analysis of hospital admissions nationwide from 2000 to 2009 shows a 10% annual increase in the incidence of AKI requiring dialysis, with at least doubling of the incidence and the number of deaths during that 10-year time period.5 Analyzing the incidence of AKI not requiring dialysis over time is more challenging because the criteria to define AKI have not been static; however, the rise in AKI requiring dialysis has mirrored the rise in AKI not requiring dialysis—suggesting that there is in fact an increased incidence of AKI, independent of variability in the defining criteria.3

Researchers reported in 2012 that during the previous year, the incidence of AKI among all hospitalized patients was 1 in 5.6 In the ICU, incidence of AKI has been reported at 39%, with a mortality rate of 25%.7 Based on the RIFLE criteria (a recently revised classification system whose name refers to Risk, Injury, Failure; Loss and End-stage kidney disease),8 as many as two-thirds of patients admitted to the ICU meet criteria for a diagnosis of AKI.

Predictors for AKI include advancing age, baseline SCr below 1.2 mg/dL, the presence of diabetes, use of IV contrast, acute coronary syndromes, sepsis, liver or heart failure, and use of nephrotoxic medications.3

It is important for clinicians to recognize the implications of AKI, even when it manifests as a relatively minor rise in SCr. In addition to its association with poor outcomes in hospitalized patients, AKI increases the risk for chronic kidney disease and for readmissions within six months after hospital discharge.9 Unfortunately, our increased awareness of the implications of AKI in the inpatient setting has yet to translate into significant improvement in outcomes.

The evolution and availability of epidemiologic and outcome data, we can only hope, will serve to direct more resources and further study toward this issue. Clinicians' efforts to prevent and treat AKI can have profound implications for many of our nation's most chronically and critically ill patients. —AC

REFERENCES

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2010 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2010/view/default.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2011 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2011/view/v2_00_appx.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

3. Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:844-861.

4. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, et al. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365-3370.

5. Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, et al. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;24:37-42.

6. Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:349-355.

7. Nisula S, Kaukonen KM, Vaara ST, et al. Incidence, risk factors and 90-day mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in Finnish intensive care units: the FINNAKI study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:420-428.

8. Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R73.

9. Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, et al. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:961-973.

10. Matzke GR, Aronoff GR, Atkinson AJ Jr, et al. Drug dosing consideration in patients with acute and chronic kidney disease: a clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011;80:1122-1137.

11. Vilay AM, Churchwell MD, Mueller BA. Clinical review: drug metabolism and nonrenal clearance in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:235.

Acute Kidney Injury in an Unexpected Patient Population

Q: When I was doing sports physicals at the high school this week, several students asked if it was true that marijuana causes kidney failure. I had not heard this. Is it true? What should I tell teens who ask about this?

Synthetic marijuana, which goes by the street names of Spice, K2, Black Mamba, Fake Weed, Genie, and Zohai, is a mixture of herbs and spices that is sprayed with a synthetic THC-type compound.1 These can be sold over the Internet as "incense" or "bath salts." However, as is often the case with drugs purchased online or from a neighborhood dealer, other compounds toxic to humans can be cut and mixed in with these substances. While hypertension, nausea, cognitive dysfunction, and dizziness have all been associated with Spice, there has been a recent flurry of reports of severe and lasting cardiac and renal damage following use of these drugs.

In 2011, three cases of Spice-associated acute coronary syndrome were reported in the pediatric literature.2 In late 2012, four residents of the same Alabama community developed AKI after using Spice. While all four eventually recovered kidney function, they now have some permanent chronic kidney damage, and all four patients required kidney biopsies.3 Similarly, the CDC recently reported 14 cases of AKI in Wyoming that developed in patients who had smoked Spice.4 Six cases were reported from Oregon, two each from New York and Oklahoma, and one each from Rhode Island and Kansas. Half of the case patients required hemodialysis and kidney biopsy. All had residual chronic kidney disease after recovery.4

The patients' presentations were similar: they were all young and healthy with no history of kidney problems—then, wham! After they had smoked Spice, severe nausea and vomiting with flank pain took them to the ER. On admission, serum creatinine (SCr) was mildly abnormal, but it rose to an average of 8 mg/dL, with one patient's SCr peaking at 21 mg/dL.4

While there have been no Spice-associated deaths reported, the critical care needed for these young people included hemodialysis. Perhaps a graphic description of the standard 15-gauge needles we use for dialysis would be helpful during a discussion of drug use with teens.

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA, Metropolitan Nephrology, Alexandria, VA, and Clinton, MD

REFERENCES

1. US Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug Fact Sheet: K2 or Spice. www.justice.gov/dea/druginfo/drug_data_sheets/K2_Spice.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

2. Mir A, Obafemi A, Young A, Kane C. Myocardial infarction associated with use of the synthetic cannabinoid K2. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1622-e1627.

3. Bhanushali GK, Jain G, Fatima H, et al. AKI associated with synthetic cannabinoids: a case series. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 Dec 14. [Epub ahead of print]

4. CDC. Acute kidney injury associated with synthetic cannabinoid use—multiple states, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:93-98.

Q: When I was doing sports physicals at the high school this week, several students asked if it was true that marijuana causes kidney failure. I had not heard this. Is it true? What should I tell teens who ask about this?

Synthetic marijuana, which goes by the street names of Spice, K2, Black Mamba, Fake Weed, Genie, and Zohai, is a mixture of herbs and spices that is sprayed with a synthetic THC-type compound.1 These can be sold over the Internet as "incense" or "bath salts." However, as is often the case with drugs purchased online or from a neighborhood dealer, other compounds toxic to humans can be cut and mixed in with these substances. While hypertension, nausea, cognitive dysfunction, and dizziness have all been associated with Spice, there has been a recent flurry of reports of severe and lasting cardiac and renal damage following use of these drugs.

In 2011, three cases of Spice-associated acute coronary syndrome were reported in the pediatric literature.2 In late 2012, four residents of the same Alabama community developed AKI after using Spice. While all four eventually recovered kidney function, they now have some permanent chronic kidney damage, and all four patients required kidney biopsies.3 Similarly, the CDC recently reported 14 cases of AKI in Wyoming that developed in patients who had smoked Spice.4 Six cases were reported from Oregon, two each from New York and Oklahoma, and one each from Rhode Island and Kansas. Half of the case patients required hemodialysis and kidney biopsy. All had residual chronic kidney disease after recovery.4

The patients' presentations were similar: they were all young and healthy with no history of kidney problems—then, wham! After they had smoked Spice, severe nausea and vomiting with flank pain took them to the ER. On admission, serum creatinine (SCr) was mildly abnormal, but it rose to an average of 8 mg/dL, with one patient's SCr peaking at 21 mg/dL.4

While there have been no Spice-associated deaths reported, the critical care needed for these young people included hemodialysis. Perhaps a graphic description of the standard 15-gauge needles we use for dialysis would be helpful during a discussion of drug use with teens.

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA, Metropolitan Nephrology, Alexandria, VA, and Clinton, MD

REFERENCES

1. US Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug Fact Sheet: K2 or Spice. www.justice.gov/dea/druginfo/drug_data_sheets/K2_Spice.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

2. Mir A, Obafemi A, Young A, Kane C. Myocardial infarction associated with use of the synthetic cannabinoid K2. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1622-e1627.

3. Bhanushali GK, Jain G, Fatima H, et al. AKI associated with synthetic cannabinoids: a case series. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 Dec 14. [Epub ahead of print]

4. CDC. Acute kidney injury associated with synthetic cannabinoid use—multiple states, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:93-98.

Q: When I was doing sports physicals at the high school this week, several students asked if it was true that marijuana causes kidney failure. I had not heard this. Is it true? What should I tell teens who ask about this?

Synthetic marijuana, which goes by the street names of Spice, K2, Black Mamba, Fake Weed, Genie, and Zohai, is a mixture of herbs and spices that is sprayed with a synthetic THC-type compound.1 These can be sold over the Internet as "incense" or "bath salts." However, as is often the case with drugs purchased online or from a neighborhood dealer, other compounds toxic to humans can be cut and mixed in with these substances. While hypertension, nausea, cognitive dysfunction, and dizziness have all been associated with Spice, there has been a recent flurry of reports of severe and lasting cardiac and renal damage following use of these drugs.

In 2011, three cases of Spice-associated acute coronary syndrome were reported in the pediatric literature.2 In late 2012, four residents of the same Alabama community developed AKI after using Spice. While all four eventually recovered kidney function, they now have some permanent chronic kidney damage, and all four patients required kidney biopsies.3 Similarly, the CDC recently reported 14 cases of AKI in Wyoming that developed in patients who had smoked Spice.4 Six cases were reported from Oregon, two each from New York and Oklahoma, and one each from Rhode Island and Kansas. Half of the case patients required hemodialysis and kidney biopsy. All had residual chronic kidney disease after recovery.4

The patients' presentations were similar: they were all young and healthy with no history of kidney problems—then, wham! After they had smoked Spice, severe nausea and vomiting with flank pain took them to the ER. On admission, serum creatinine (SCr) was mildly abnormal, but it rose to an average of 8 mg/dL, with one patient's SCr peaking at 21 mg/dL.4

While there have been no Spice-associated deaths reported, the critical care needed for these young people included hemodialysis. Perhaps a graphic description of the standard 15-gauge needles we use for dialysis would be helpful during a discussion of drug use with teens.

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA, Metropolitan Nephrology, Alexandria, VA, and Clinton, MD

REFERENCES

1. US Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug Fact Sheet: K2 or Spice. www.justice.gov/dea/druginfo/drug_data_sheets/K2_Spice.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

2. Mir A, Obafemi A, Young A, Kane C. Myocardial infarction associated with use of the synthetic cannabinoid K2. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1622-e1627.

3. Bhanushali GK, Jain G, Fatima H, et al. AKI associated with synthetic cannabinoids: a case series. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 Dec 14. [Epub ahead of print]

4. CDC. Acute kidney injury associated with synthetic cannabinoid use—multiple states, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:93-98.

Guidelines on Hematuria: Determing the Cause

The American Urological Association (AUA) published guidelines for asymptomatic microhematuria. The document includes 19 guidelines with recommendation levels ranging from A to C (high to low) and some expert opinion recommendations included. The full guidelines can be accessed at http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Asymptomatic-Microhematuria.pdf.

Q: A 45-year-old man came into my office complaining that he had seen “pink” in his urine. I dipped the urine in the office, and it was positive for blood. What should I do now? Should I send him directly to nephrology or urology? Or should I do a work-up myself? And if I do the work-up, what tests should I order?

When treating the patient with hematuria, it is important to keep in mind both the most common benign causes and the more serious causes of hematuria. The most common benign causes, according to the AUA guideline 6,1 include infection, menstruation, vigorous exercise, trauma, anticoagulant use, and a recent urologic procedure. The potentially serious causes include glomerulonephritis (which can be rapidly progressive) and malignancy.

The AUA (guidelines 1 to 4, based on expert opinion)1 recommends confirming hematuria with a microscopic exam rather than relying on a urine dipstick.

The common benign causes of hematuria can usually be identified in the course of a thorough history and physical. Because hematuria can be a harbinger of renal disease, however, serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) should be ordered at the initial evaluation in the primary care setting.

If a benign cause of hematuria is identified and renal function is normal, the patient should be treated by the primary care provider and re-evaluated as indicated, based on the underlying diagnosis. If there is a rise in serum creatinine or a reduction in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in conjunction with the hematuria, the patient should be referred to nephrology for further evaluation.

If no benign cause of hematuria is identified and renal function is unaffected, the patient should be referred to urology for urologic evaluation.1

Alexis Chettiar, ACNP, East Bay Nephrology Medical Group, Oakland, CA

References

1. Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA, et al; American Urological Association. Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Follow-up of Asymptomatic Microhematuria (AMH) in Adults: AUA Guideline. Linthicum, MD: American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc; 2012. http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Asymptomatic-Microhematuria.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2013.

2. National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse. Hematuria: blood in the urine (2012). http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/hematuria. Accessed January 17, 2013.

3. Geavlete B, Jecu M, Multescu R, et al. HAL blue-light cystoscopy in high-risk nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer: re-TURBT recurrence rates in a prospective, randomized study. Urology. 2010;76(3):664-669.

Suggested Reading

Feldman AS, Hsu C-Y, Kurtz M, Cho KC. Etiology and evaluation of hematuria in adults (2012). www.uptodate.com/contents/etiology-and-evaluation-of-hematuria-in-adults. Accessed January 17, 2013.

Jayne D. Hematuria and proteinuria. In: Greenberg A, ed; National Kidney Foundation. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Saunders; 2009:33-42.

The American Urological Association (AUA) published guidelines for asymptomatic microhematuria. The document includes 19 guidelines with recommendation levels ranging from A to C (high to low) and some expert opinion recommendations included. The full guidelines can be accessed at http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Asymptomatic-Microhematuria.pdf.

Q: A 45-year-old man came into my office complaining that he had seen “pink” in his urine. I dipped the urine in the office, and it was positive for blood. What should I do now? Should I send him directly to nephrology or urology? Or should I do a work-up myself? And if I do the work-up, what tests should I order?

When treating the patient with hematuria, it is important to keep in mind both the most common benign causes and the more serious causes of hematuria. The most common benign causes, according to the AUA guideline 6,1 include infection, menstruation, vigorous exercise, trauma, anticoagulant use, and a recent urologic procedure. The potentially serious causes include glomerulonephritis (which can be rapidly progressive) and malignancy.

The AUA (guidelines 1 to 4, based on expert opinion)1 recommends confirming hematuria with a microscopic exam rather than relying on a urine dipstick.

The common benign causes of hematuria can usually be identified in the course of a thorough history and physical. Because hematuria can be a harbinger of renal disease, however, serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) should be ordered at the initial evaluation in the primary care setting.

If a benign cause of hematuria is identified and renal function is normal, the patient should be treated by the primary care provider and re-evaluated as indicated, based on the underlying diagnosis. If there is a rise in serum creatinine or a reduction in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in conjunction with the hematuria, the patient should be referred to nephrology for further evaluation.

If no benign cause of hematuria is identified and renal function is unaffected, the patient should be referred to urology for urologic evaluation.1

Alexis Chettiar, ACNP, East Bay Nephrology Medical Group, Oakland, CA

References

1. Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA, et al; American Urological Association. Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Follow-up of Asymptomatic Microhematuria (AMH) in Adults: AUA Guideline. Linthicum, MD: American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc; 2012. http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Asymptomatic-Microhematuria.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2013.

2. National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse. Hematuria: blood in the urine (2012). http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/hematuria. Accessed January 17, 2013.

3. Geavlete B, Jecu M, Multescu R, et al. HAL blue-light cystoscopy in high-risk nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer: re-TURBT recurrence rates in a prospective, randomized study. Urology. 2010;76(3):664-669.

Suggested Reading

Feldman AS, Hsu C-Y, Kurtz M, Cho KC. Etiology and evaluation of hematuria in adults (2012). www.uptodate.com/contents/etiology-and-evaluation-of-hematuria-in-adults. Accessed January 17, 2013.

Jayne D. Hematuria and proteinuria. In: Greenberg A, ed; National Kidney Foundation. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Saunders; 2009:33-42.

The American Urological Association (AUA) published guidelines for asymptomatic microhematuria. The document includes 19 guidelines with recommendation levels ranging from A to C (high to low) and some expert opinion recommendations included. The full guidelines can be accessed at http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Asymptomatic-Microhematuria.pdf.

Q: A 45-year-old man came into my office complaining that he had seen “pink” in his urine. I dipped the urine in the office, and it was positive for blood. What should I do now? Should I send him directly to nephrology or urology? Or should I do a work-up myself? And if I do the work-up, what tests should I order?

When treating the patient with hematuria, it is important to keep in mind both the most common benign causes and the more serious causes of hematuria. The most common benign causes, according to the AUA guideline 6,1 include infection, menstruation, vigorous exercise, trauma, anticoagulant use, and a recent urologic procedure. The potentially serious causes include glomerulonephritis (which can be rapidly progressive) and malignancy.

The AUA (guidelines 1 to 4, based on expert opinion)1 recommends confirming hematuria with a microscopic exam rather than relying on a urine dipstick.

The common benign causes of hematuria can usually be identified in the course of a thorough history and physical. Because hematuria can be a harbinger of renal disease, however, serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) should be ordered at the initial evaluation in the primary care setting.

If a benign cause of hematuria is identified and renal function is normal, the patient should be treated by the primary care provider and re-evaluated as indicated, based on the underlying diagnosis. If there is a rise in serum creatinine or a reduction in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in conjunction with the hematuria, the patient should be referred to nephrology for further evaluation.

If no benign cause of hematuria is identified and renal function is unaffected, the patient should be referred to urology for urologic evaluation.1

Alexis Chettiar, ACNP, East Bay Nephrology Medical Group, Oakland, CA

References

1. Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA, et al; American Urological Association. Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Follow-up of Asymptomatic Microhematuria (AMH) in Adults: AUA Guideline. Linthicum, MD: American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc; 2012. http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Asymptomatic-Microhematuria.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2013.

2. National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse. Hematuria: blood in the urine (2012). http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/hematuria. Accessed January 17, 2013.

3. Geavlete B, Jecu M, Multescu R, et al. HAL blue-light cystoscopy in high-risk nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer: re-TURBT recurrence rates in a prospective, randomized study. Urology. 2010;76(3):664-669.

Suggested Reading

Feldman AS, Hsu C-Y, Kurtz M, Cho KC. Etiology and evaluation of hematuria in adults (2012). www.uptodate.com/contents/etiology-and-evaluation-of-hematuria-in-adults. Accessed January 17, 2013.

Jayne D. Hematuria and proteinuria. In: Greenberg A, ed; National Kidney Foundation. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Saunders; 2009:33-42.

Guidelines on Hematuria: Urologic and Nephrologic Evaluation

The American Urological Association (AUA) published guidelines for asymptomatic microhematuria. The document includes 19 guidelines with recommendation levels ranging from A to C (high to low) and some expert opinion recommendations included. The full guidelines can be accessed at http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Asymptomatic-Microhematuria.pdf.

Q: I have a 58-year-old female patient who is taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation and is complaining about blood in her urine. She is postmenopausal, so I think it is just the warfarin. Other than checking her international normalized ratio (INR), what else should I be doing?

In addition to checking an INR, it is important to investigate benign causes for the hematuria. Asymptomatic hematuria requires obtaining a thorough history, which includes common risk factors for urinary tract malignancy, physical exam, and laboratory evaluation. Initially, a noncontaminated urinalysis with culture and sensitivity should be obtained to rule out infection.

If a benign cause cannot be found in any patient undergoing anticoagulation therapy, the AUA (guideline 6)1 recommends a urologic and nephrologic evaluation. Anticoagulation therapy would include all anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents, such as aspirin, Plavix (clopidogrel), Pletal (cilostazol), Coumadin (warfarin), heparin, or heparin derivatives, such as Lovenox (enoxaparin).

The urologic evaluation may include urology referral, cystoscopy for patients 35 or older, and multiphasic CT urography, performed with and without contrast. A nephrologic evaluation would initially include a urinalysis, calculated eGFR, creatinine, and BUN, and a nephrology referral when indicated. A thorough evaluation is indicated for all patients with hematuria who are on anticoagulant therapy to ensure that a urinary tract malignancy is not present.

AUA guidelines 10 through 131 address alternative tests for patients with kidney disease in whom contrast dye is contraindicated.

Kristy Washinger, MSN, CRNP, Nephrology Associates of Central Pennsylvania, Camp Hill, PA

References

1. Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA, et al; American Urological Association. Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Follow-up of Asymptomatic Microhematuria (AMH) in Adults: AUA Guideline. Linthicum, MD: American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc; 2012. http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Asymptomatic-Microhematuria.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2013.

2. National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse. Hematuria: blood in the urine (2012). http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/hematuria. Accessed January 17, 2013.

3. Geavlete B, Jecu M, Multescu R, et al. HAL blue-light cystoscopy in high-risk nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer: re-TURBT recurrence rates in a prospective, randomized study. Urology. 2010;76(3):664-669.

Suggested Reading

Feldman AS, Hsu C-Y, Kurtz M, Cho KC. Etiology and evaluation of hematuria in adults (2012). www.uptodate.com/contents/etiology-and-evaluation-of-hematuria-in-adults. Accessed January 17, 2013.

Jayne D. Hematuria and proteinuria. In: Greenberg A, ed; National Kidney Foundation. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Saunders; 2009:33-42.

The American Urological Association (AUA) published guidelines for asymptomatic microhematuria. The document includes 19 guidelines with recommendation levels ranging from A to C (high to low) and some expert opinion recommendations included. The full guidelines can be accessed at http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Asymptomatic-Microhematuria.pdf.

Q: I have a 58-year-old female patient who is taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation and is complaining about blood in her urine. She is postmenopausal, so I think it is just the warfarin. Other than checking her international normalized ratio (INR), what else should I be doing?

In addition to checking an INR, it is important to investigate benign causes for the hematuria. Asymptomatic hematuria requires obtaining a thorough history, which includes common risk factors for urinary tract malignancy, physical exam, and laboratory evaluation. Initially, a noncontaminated urinalysis with culture and sensitivity should be obtained to rule out infection.

If a benign cause cannot be found in any patient undergoing anticoagulation therapy, the AUA (guideline 6)1 recommends a urologic and nephrologic evaluation. Anticoagulation therapy would include all anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents, such as aspirin, Plavix (clopidogrel), Pletal (cilostazol), Coumadin (warfarin), heparin, or heparin derivatives, such as Lovenox (enoxaparin).

The urologic evaluation may include urology referral, cystoscopy for patients 35 or older, and multiphasic CT urography, performed with and without contrast. A nephrologic evaluation would initially include a urinalysis, calculated eGFR, creatinine, and BUN, and a nephrology referral when indicated. A thorough evaluation is indicated for all patients with hematuria who are on anticoagulant therapy to ensure that a urinary tract malignancy is not present.

AUA guidelines 10 through 131 address alternative tests for patients with kidney disease in whom contrast dye is contraindicated.

Kristy Washinger, MSN, CRNP, Nephrology Associates of Central Pennsylvania, Camp Hill, PA

References

1. Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA, et al; American Urological Association. Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Follow-up of Asymptomatic Microhematuria (AMH) in Adults: AUA Guideline. Linthicum, MD: American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc; 2012. http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Asymptomatic-Microhematuria.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2013.

2. National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse. Hematuria: blood in the urine (2012). http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/hematuria. Accessed January 17, 2013.

3. Geavlete B, Jecu M, Multescu R, et al. HAL blue-light cystoscopy in high-risk nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer: re-TURBT recurrence rates in a prospective, randomized study. Urology. 2010;76(3):664-669.

Suggested Reading

Feldman AS, Hsu C-Y, Kurtz M, Cho KC. Etiology and evaluation of hematuria in adults (2012). www.uptodate.com/contents/etiology-and-evaluation-of-hematuria-in-adults. Accessed January 17, 2013.

Jayne D. Hematuria and proteinuria. In: Greenberg A, ed; National Kidney Foundation. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Saunders; 2009:33-42.

The American Urological Association (AUA) published guidelines for asymptomatic microhematuria. The document includes 19 guidelines with recommendation levels ranging from A to C (high to low) and some expert opinion recommendations included. The full guidelines can be accessed at http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Asymptomatic-Microhematuria.pdf.

Q: I have a 58-year-old female patient who is taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation and is complaining about blood in her urine. She is postmenopausal, so I think it is just the warfarin. Other than checking her international normalized ratio (INR), what else should I be doing?

In addition to checking an INR, it is important to investigate benign causes for the hematuria. Asymptomatic hematuria requires obtaining a thorough history, which includes common risk factors for urinary tract malignancy, physical exam, and laboratory evaluation. Initially, a noncontaminated urinalysis with culture and sensitivity should be obtained to rule out infection.

If a benign cause cannot be found in any patient undergoing anticoagulation therapy, the AUA (guideline 6)1 recommends a urologic and nephrologic evaluation. Anticoagulation therapy would include all anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents, such as aspirin, Plavix (clopidogrel), Pletal (cilostazol), Coumadin (warfarin), heparin, or heparin derivatives, such as Lovenox (enoxaparin).

The urologic evaluation may include urology referral, cystoscopy for patients 35 or older, and multiphasic CT urography, performed with and without contrast. A nephrologic evaluation would initially include a urinalysis, calculated eGFR, creatinine, and BUN, and a nephrology referral when indicated. A thorough evaluation is indicated for all patients with hematuria who are on anticoagulant therapy to ensure that a urinary tract malignancy is not present.

AUA guidelines 10 through 131 address alternative tests for patients with kidney disease in whom contrast dye is contraindicated.

Kristy Washinger, MSN, CRNP, Nephrology Associates of Central Pennsylvania, Camp Hill, PA

References

1. Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA, et al; American Urological Association. Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Follow-up of Asymptomatic Microhematuria (AMH) in Adults: AUA Guideline. Linthicum, MD: American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc; 2012. http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Asymptomatic-Microhematuria.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2013.

2. National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse. Hematuria: blood in the urine (2012). http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/hematuria. Accessed January 17, 2013.

3. Geavlete B, Jecu M, Multescu R, et al. HAL blue-light cystoscopy in high-risk nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer: re-TURBT recurrence rates in a prospective, randomized study. Urology. 2010;76(3):664-669.

Suggested Reading

Feldman AS, Hsu C-Y, Kurtz M, Cho KC. Etiology and evaluation of hematuria in adults (2012). www.uptodate.com/contents/etiology-and-evaluation-of-hematuria-in-adults. Accessed January 17, 2013.

Jayne D. Hematuria and proteinuria. In: Greenberg A, ed; National Kidney Foundation. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Saunders; 2009:33-42.

Guidelines on Hematuria: First-line Evaluation

The American Urological Association (AUA) published guidelines for asymptomatic microhematuria. The document includes 19 guidelines with recommendation levels ranging from A to C (high to low) and some expert opinion recommendations included. The full guidelines can be accessed at http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Asymptomatic-Microhematuria.pdf.