User login

EMA recommends orphan status for drug in SCD

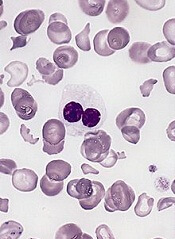

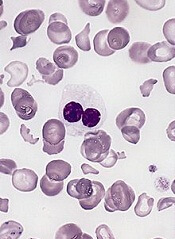

and normal red blood cells

Image by Graham Beards

The European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP) has issued a positive opinion recommending that LJPC-401 receive orphan designation as a treatment for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

LJPC-401 is a formulation of synthetic human hepcidin.

La Jolla Pharmaceutical Company is developing LJPC-401 for the treatment of iron overload, which can occur in SCD and other diseases.

LJPC-401 already has orphan designation in the European Union as a treatment for patients with beta-thalassemia intermedia and major.

La Jolla recently reported positive results from a phase 1 study of LJPC-401 in patients at risk of iron overload suffering from hereditary hemochromatosis, thalassemia, or SCD. Fifteen patients received LJPC-401 at escalating dose levels ranging from 1 mg to 20 mg.

The researchers observed a dose-dependent, statistically significant reduction in serum iron (P=0.008 for dose response; not adjusted for multiple comparisons).

At the 20 mg dose level, LJPC-401 reduced serum iron by an average of 58.1% from baseline to hour 8 (P=0.001; not adjusted for potential regression to the mean effect), and serum iron had not returned to baseline through day 7 (21.2% reduction from baseline to the end of day 7).

The researchers also said LJPC-401 was well tolerated, with no dose-limiting toxicities. Injection-site reactions were the most commonly reported adverse event. These were all mild or moderate in severity, self-limiting, and fully resolved.

Now, La Jolla is working to initiate a pivotal study of LJPC-401. This will be a randomized, controlled, multicenter study in beta-thalassemia patients suffering from iron overload. La Jolla plans to initiate this study in mid-2017.

About orphan designation

The EMA’s COMP adopts an opinion on the granting of orphan drug designation, and that opinion is submitted to the European Commission for a final decision.

Orphan designation provides regulatory and financial incentives for companies to develop and market therapies that treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Orphan designation provides a 10-year period of marketing exclusivity if the drug receives regulatory approval. The designation also provides incentives for companies seeking protocol assistance from the EMA during the product development phase and direct access to the centralized authorization procedure. ![]()

and normal red blood cells

Image by Graham Beards

The European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP) has issued a positive opinion recommending that LJPC-401 receive orphan designation as a treatment for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

LJPC-401 is a formulation of synthetic human hepcidin.

La Jolla Pharmaceutical Company is developing LJPC-401 for the treatment of iron overload, which can occur in SCD and other diseases.

LJPC-401 already has orphan designation in the European Union as a treatment for patients with beta-thalassemia intermedia and major.

La Jolla recently reported positive results from a phase 1 study of LJPC-401 in patients at risk of iron overload suffering from hereditary hemochromatosis, thalassemia, or SCD. Fifteen patients received LJPC-401 at escalating dose levels ranging from 1 mg to 20 mg.

The researchers observed a dose-dependent, statistically significant reduction in serum iron (P=0.008 for dose response; not adjusted for multiple comparisons).

At the 20 mg dose level, LJPC-401 reduced serum iron by an average of 58.1% from baseline to hour 8 (P=0.001; not adjusted for potential regression to the mean effect), and serum iron had not returned to baseline through day 7 (21.2% reduction from baseline to the end of day 7).

The researchers also said LJPC-401 was well tolerated, with no dose-limiting toxicities. Injection-site reactions were the most commonly reported adverse event. These were all mild or moderate in severity, self-limiting, and fully resolved.

Now, La Jolla is working to initiate a pivotal study of LJPC-401. This will be a randomized, controlled, multicenter study in beta-thalassemia patients suffering from iron overload. La Jolla plans to initiate this study in mid-2017.

About orphan designation

The EMA’s COMP adopts an opinion on the granting of orphan drug designation, and that opinion is submitted to the European Commission for a final decision.

Orphan designation provides regulatory and financial incentives for companies to develop and market therapies that treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Orphan designation provides a 10-year period of marketing exclusivity if the drug receives regulatory approval. The designation also provides incentives for companies seeking protocol assistance from the EMA during the product development phase and direct access to the centralized authorization procedure. ![]()

and normal red blood cells

Image by Graham Beards

The European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP) has issued a positive opinion recommending that LJPC-401 receive orphan designation as a treatment for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

LJPC-401 is a formulation of synthetic human hepcidin.

La Jolla Pharmaceutical Company is developing LJPC-401 for the treatment of iron overload, which can occur in SCD and other diseases.

LJPC-401 already has orphan designation in the European Union as a treatment for patients with beta-thalassemia intermedia and major.

La Jolla recently reported positive results from a phase 1 study of LJPC-401 in patients at risk of iron overload suffering from hereditary hemochromatosis, thalassemia, or SCD. Fifteen patients received LJPC-401 at escalating dose levels ranging from 1 mg to 20 mg.

The researchers observed a dose-dependent, statistically significant reduction in serum iron (P=0.008 for dose response; not adjusted for multiple comparisons).

At the 20 mg dose level, LJPC-401 reduced serum iron by an average of 58.1% from baseline to hour 8 (P=0.001; not adjusted for potential regression to the mean effect), and serum iron had not returned to baseline through day 7 (21.2% reduction from baseline to the end of day 7).

The researchers also said LJPC-401 was well tolerated, with no dose-limiting toxicities. Injection-site reactions were the most commonly reported adverse event. These were all mild or moderate in severity, self-limiting, and fully resolved.

Now, La Jolla is working to initiate a pivotal study of LJPC-401. This will be a randomized, controlled, multicenter study in beta-thalassemia patients suffering from iron overload. La Jolla plans to initiate this study in mid-2017.

About orphan designation

The EMA’s COMP adopts an opinion on the granting of orphan drug designation, and that opinion is submitted to the European Commission for a final decision.

Orphan designation provides regulatory and financial incentives for companies to develop and market therapies that treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Orphan designation provides a 10-year period of marketing exclusivity if the drug receives regulatory approval. The designation also provides incentives for companies seeking protocol assistance from the EMA during the product development phase and direct access to the centralized authorization procedure. ![]()

Test approved to screen donated blood for sickle cell trait

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved use of the PreciseType HEA test to screen blood donors for sickle cell trait (SCT).

The test was previously FDA approved for use in determining blood compatibility between donors and transfusion recipients.

The added utility of screening donors for SCT addresses the desire to avoid transfusing red blood cells from SCT donors to neonates or patients with sickle cell disease.

Blood from SCT donors can also present a problem when performing the required filtration of white cells from the blood donation.

The PreciseType HEA test will allow these units to be identified prior to filtration and provide blood center staff with the opportunity to decide how best to utilize the various components of a whole blood donation.

The PreciseType HEA test is manufactured by BioArray Solutions, a wholly owned subsidiary of Immucor, Inc.

“We’ve successfully demonstrated the clinical benefits of our PreciseType HEA test, and this is evident in the FDA broadening its approved use,” said Michael Spigarelli, vice president of medical affairs at Immucor.

“The use of PreciseType HEA to screen donor units for patients with sickle cell disease, neonates, or any individual that may require SCT-negative blood provides a great improvement over previously used methods and offers the first FDA-approved molecular method specifically for screening units.”

SCT screening has traditionally been performed by solubility testing of sickle hemoglobin in buffer, but blood centers have been looking for an alternative due to limitations in this method.

According to Immucor, a molecular approach using PreciseType HEA can overcome the throughput limitations and reduce the false-positive rates observed with the traditional SCT screening method.

“We had already validated the PreciseType HEA test for [SCT screening] in our lab,” said Connie Westhoff, PhD, of the New York Blood Center in New York, New York.

“Our previous screening method required manual testing and interpretation of the results and had high false-positive rates. About 1 in 12 minority donors possess the sickle trait, so accurate results are important to us to avoid unnecessary notifications to donors and deferred blood units. We are now able to identify SCT in our donors utilizing the same PreciseType HEA test we are already running on many of our donors without running additional tests.” ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved use of the PreciseType HEA test to screen blood donors for sickle cell trait (SCT).

The test was previously FDA approved for use in determining blood compatibility between donors and transfusion recipients.

The added utility of screening donors for SCT addresses the desire to avoid transfusing red blood cells from SCT donors to neonates or patients with sickle cell disease.

Blood from SCT donors can also present a problem when performing the required filtration of white cells from the blood donation.

The PreciseType HEA test will allow these units to be identified prior to filtration and provide blood center staff with the opportunity to decide how best to utilize the various components of a whole blood donation.

The PreciseType HEA test is manufactured by BioArray Solutions, a wholly owned subsidiary of Immucor, Inc.

“We’ve successfully demonstrated the clinical benefits of our PreciseType HEA test, and this is evident in the FDA broadening its approved use,” said Michael Spigarelli, vice president of medical affairs at Immucor.

“The use of PreciseType HEA to screen donor units for patients with sickle cell disease, neonates, or any individual that may require SCT-negative blood provides a great improvement over previously used methods and offers the first FDA-approved molecular method specifically for screening units.”

SCT screening has traditionally been performed by solubility testing of sickle hemoglobin in buffer, but blood centers have been looking for an alternative due to limitations in this method.

According to Immucor, a molecular approach using PreciseType HEA can overcome the throughput limitations and reduce the false-positive rates observed with the traditional SCT screening method.

“We had already validated the PreciseType HEA test for [SCT screening] in our lab,” said Connie Westhoff, PhD, of the New York Blood Center in New York, New York.

“Our previous screening method required manual testing and interpretation of the results and had high false-positive rates. About 1 in 12 minority donors possess the sickle trait, so accurate results are important to us to avoid unnecessary notifications to donors and deferred blood units. We are now able to identify SCT in our donors utilizing the same PreciseType HEA test we are already running on many of our donors without running additional tests.” ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved use of the PreciseType HEA test to screen blood donors for sickle cell trait (SCT).

The test was previously FDA approved for use in determining blood compatibility between donors and transfusion recipients.

The added utility of screening donors for SCT addresses the desire to avoid transfusing red blood cells from SCT donors to neonates or patients with sickle cell disease.

Blood from SCT donors can also present a problem when performing the required filtration of white cells from the blood donation.

The PreciseType HEA test will allow these units to be identified prior to filtration and provide blood center staff with the opportunity to decide how best to utilize the various components of a whole blood donation.

The PreciseType HEA test is manufactured by BioArray Solutions, a wholly owned subsidiary of Immucor, Inc.

“We’ve successfully demonstrated the clinical benefits of our PreciseType HEA test, and this is evident in the FDA broadening its approved use,” said Michael Spigarelli, vice president of medical affairs at Immucor.

“The use of PreciseType HEA to screen donor units for patients with sickle cell disease, neonates, or any individual that may require SCT-negative blood provides a great improvement over previously used methods and offers the first FDA-approved molecular method specifically for screening units.”

SCT screening has traditionally been performed by solubility testing of sickle hemoglobin in buffer, but blood centers have been looking for an alternative due to limitations in this method.

According to Immucor, a molecular approach using PreciseType HEA can overcome the throughput limitations and reduce the false-positive rates observed with the traditional SCT screening method.

“We had already validated the PreciseType HEA test for [SCT screening] in our lab,” said Connie Westhoff, PhD, of the New York Blood Center in New York, New York.

“Our previous screening method required manual testing and interpretation of the results and had high false-positive rates. About 1 in 12 minority donors possess the sickle trait, so accurate results are important to us to avoid unnecessary notifications to donors and deferred blood units. We are now able to identify SCT in our donors utilizing the same PreciseType HEA test we are already running on many of our donors without running additional tests.” ![]()

Drug fails to meet endpoint in phase 3 ITP trial

The SYK inhibitor fostamatinib did not meet the primary endpoint in a phase 3 study of adults with chronic/persistent immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), according to Rigel Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing the drug.

However, fostamatinib did meet that endpoint—a significantly higher incidence of stable platelet response compared to placebo—in an identical phase 3 study.

The combined data from both studies—known as FIT 1 and FIT 2—suggest fostamatinib confers a benefit over placebo.

Therefore, Rigel Pharmaceuticals is still planning to submit a new drug application for fostamatinib to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) next year, pending feedback from the agency.

“We believe that the totality and consistency of data from the FIT phase 3 program . . . strongly supports a clear treatment effect, with a sustained clinical benefit of fostamatinib,” said Raul Rodriguez, president and chief executive officer of Rigel Pharmaceuticals.

“We are encouraged by these results and believe that the risk/benefit ratio for fostamatinib is positive for patients with chronic/persistent ITP . . . . As a result, we will continue to pursue this opportunity. Our next step is to seek feedback from the FDA.”

About the FIT studies

Rigel’s FIT program consists of 2 identical, multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies of approximately 75 adults each—FIT 1 (Study 047) and FIT 2 (Study 048).

The patients enrolled in each study had been diagnosed with persistent or chronic ITP, had failed at least 1 prior therapy for ITP, and had platelet counts consistently below 30,000/uL of blood.

In both studies, patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either fostamatinib or placebo orally twice a day for up to 24 weeks.

Patients were subsequently given the opportunity to enroll in an open-label, long-term, phase 3 extension study (Study 049), which is ongoing.

Patient characteristics

In FIT 1, 51 patients were randomized to fostamatinib and 25 to placebo. The median age was 57 in both treatment arms. The duration of ITP was 7.5 years (range, 0.6-53) in the fostamatinib arm and 5.5 years (range, 0.4-45) in the placebo arm.

Prior treatments (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included steroids (90% and 100%), rituximab (51% and 44%), thrombopoietic agents (50% and 60%), and splenectomy (39% and 40%).

The median platelet count at baseline was 15,000/uL in the fostamatinib arm and 16,000/uL in the placebo arm.

In FIT 2, 50 patients were randomized to fostamatinib and 24 to placebo. The median age was 50 in both treatment arms. The duration of ITP was 8.8 years (range, 0.3-50) in the fostamatinib arm and 10.8 years (range, 0.9-29) in the placebo arm.

Prior treatments (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included steroids (90% and 92%), rituximab (16% and 13%), thrombopoietic agents (40% and 42%), and splenectomy (28% and 38%).

The median platelet count at baseline was 16,000/uL in the fostamatinib arm and 21,000/uL in the placebo arm.

Efficacy

The primary efficacy endpoint in both studies is a stable platelet response, which is defined as achieving platelet counts greater than 50,000/uL of blood for at least 4 of the 6 scheduled clinic visits between weeks 14 and 24 of treatment.

In FIT 1, the rate of stable platelet response was significantly higher in the fostamatinib arm than the placebo arm—18% (n=9) and 0%, respectively (P=0.026).

In FIT 2, however, the difference in stable platelet response between the 2 arms was not significant—18% (n=9) and 4% (n=1), respectively (P=0.152).

When the data from FIT 1 and FIT 2 are combined, the response rate is significantly higher in the fostamatinib arm than the placebo arm—18% (18/101) and 2% (1/49), respectively (P=0.007).

The response rate is significantly better in the fostamatinib arm across all subgroups, regardless of whether patients had prior splenectomy, prior exposure to thrombopoietic agents, or baseline platelet counts above or below 15,000/uL.

In the combined dataset, patients who met the primary endpoint had their platelet counts increase from a median of 18,500/uL at baseline to more than 100,000/uL at week 24 of treatment.

In addition, patients who met the primary endpoint had a timely platelet response, and that response was enduring, according to James B. Bussel, MD, a professor at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York, principal investigator on the FIT phase 3 program, and a member of Rigel’s advisory/scientific board.

“The FIT phase 3 studies have both demonstrated that fostamatinib provided a robust and enduring benefit for those patients who responded to the drug,” he said.

Safety

In FIT 1, the overall incidence of adverse events (AEs) was 96% in the fostamatinib arm and 76% in the placebo arm. The incidence of serious AEs was 16% and 20%, respectively. And the incidence of treatment-related AEs was 77% and 28%, respectively.

AEs (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included gastrointestinal complaints (nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain; 61% and 20%), nausea (29% and 4%), diarrhea (45% and 16%), infection (33% and 20%), hypertension during visit (35% and 8%), and transaminase elevation (22% and 0%).

In FIT 2, the overall incidence of AEs was 71% in the fostamatinib arm and 78% in the placebo arm. The incidence of serious AEs was 10% and 26%, respectively. And the incidence of treatment-related AEs was 39% and 26%, respectively.

AEs (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included gastrointestinal complaints (22% in both arms), nausea (8% and 13%), diarrhea (18% and 13%), infection (22% in both arms), hypertension during visit (20% and 17%), and transaminase elevation (6% and 0%). ![]()

The SYK inhibitor fostamatinib did not meet the primary endpoint in a phase 3 study of adults with chronic/persistent immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), according to Rigel Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing the drug.

However, fostamatinib did meet that endpoint—a significantly higher incidence of stable platelet response compared to placebo—in an identical phase 3 study.

The combined data from both studies—known as FIT 1 and FIT 2—suggest fostamatinib confers a benefit over placebo.

Therefore, Rigel Pharmaceuticals is still planning to submit a new drug application for fostamatinib to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) next year, pending feedback from the agency.

“We believe that the totality and consistency of data from the FIT phase 3 program . . . strongly supports a clear treatment effect, with a sustained clinical benefit of fostamatinib,” said Raul Rodriguez, president and chief executive officer of Rigel Pharmaceuticals.

“We are encouraged by these results and believe that the risk/benefit ratio for fostamatinib is positive for patients with chronic/persistent ITP . . . . As a result, we will continue to pursue this opportunity. Our next step is to seek feedback from the FDA.”

About the FIT studies

Rigel’s FIT program consists of 2 identical, multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies of approximately 75 adults each—FIT 1 (Study 047) and FIT 2 (Study 048).

The patients enrolled in each study had been diagnosed with persistent or chronic ITP, had failed at least 1 prior therapy for ITP, and had platelet counts consistently below 30,000/uL of blood.

In both studies, patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either fostamatinib or placebo orally twice a day for up to 24 weeks.

Patients were subsequently given the opportunity to enroll in an open-label, long-term, phase 3 extension study (Study 049), which is ongoing.

Patient characteristics

In FIT 1, 51 patients were randomized to fostamatinib and 25 to placebo. The median age was 57 in both treatment arms. The duration of ITP was 7.5 years (range, 0.6-53) in the fostamatinib arm and 5.5 years (range, 0.4-45) in the placebo arm.

Prior treatments (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included steroids (90% and 100%), rituximab (51% and 44%), thrombopoietic agents (50% and 60%), and splenectomy (39% and 40%).

The median platelet count at baseline was 15,000/uL in the fostamatinib arm and 16,000/uL in the placebo arm.

In FIT 2, 50 patients were randomized to fostamatinib and 24 to placebo. The median age was 50 in both treatment arms. The duration of ITP was 8.8 years (range, 0.3-50) in the fostamatinib arm and 10.8 years (range, 0.9-29) in the placebo arm.

Prior treatments (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included steroids (90% and 92%), rituximab (16% and 13%), thrombopoietic agents (40% and 42%), and splenectomy (28% and 38%).

The median platelet count at baseline was 16,000/uL in the fostamatinib arm and 21,000/uL in the placebo arm.

Efficacy

The primary efficacy endpoint in both studies is a stable platelet response, which is defined as achieving platelet counts greater than 50,000/uL of blood for at least 4 of the 6 scheduled clinic visits between weeks 14 and 24 of treatment.

In FIT 1, the rate of stable platelet response was significantly higher in the fostamatinib arm than the placebo arm—18% (n=9) and 0%, respectively (P=0.026).

In FIT 2, however, the difference in stable platelet response between the 2 arms was not significant—18% (n=9) and 4% (n=1), respectively (P=0.152).

When the data from FIT 1 and FIT 2 are combined, the response rate is significantly higher in the fostamatinib arm than the placebo arm—18% (18/101) and 2% (1/49), respectively (P=0.007).

The response rate is significantly better in the fostamatinib arm across all subgroups, regardless of whether patients had prior splenectomy, prior exposure to thrombopoietic agents, or baseline platelet counts above or below 15,000/uL.

In the combined dataset, patients who met the primary endpoint had their platelet counts increase from a median of 18,500/uL at baseline to more than 100,000/uL at week 24 of treatment.

In addition, patients who met the primary endpoint had a timely platelet response, and that response was enduring, according to James B. Bussel, MD, a professor at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York, principal investigator on the FIT phase 3 program, and a member of Rigel’s advisory/scientific board.

“The FIT phase 3 studies have both demonstrated that fostamatinib provided a robust and enduring benefit for those patients who responded to the drug,” he said.

Safety

In FIT 1, the overall incidence of adverse events (AEs) was 96% in the fostamatinib arm and 76% in the placebo arm. The incidence of serious AEs was 16% and 20%, respectively. And the incidence of treatment-related AEs was 77% and 28%, respectively.

AEs (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included gastrointestinal complaints (nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain; 61% and 20%), nausea (29% and 4%), diarrhea (45% and 16%), infection (33% and 20%), hypertension during visit (35% and 8%), and transaminase elevation (22% and 0%).

In FIT 2, the overall incidence of AEs was 71% in the fostamatinib arm and 78% in the placebo arm. The incidence of serious AEs was 10% and 26%, respectively. And the incidence of treatment-related AEs was 39% and 26%, respectively.

AEs (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included gastrointestinal complaints (22% in both arms), nausea (8% and 13%), diarrhea (18% and 13%), infection (22% in both arms), hypertension during visit (20% and 17%), and transaminase elevation (6% and 0%). ![]()

The SYK inhibitor fostamatinib did not meet the primary endpoint in a phase 3 study of adults with chronic/persistent immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), according to Rigel Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing the drug.

However, fostamatinib did meet that endpoint—a significantly higher incidence of stable platelet response compared to placebo—in an identical phase 3 study.

The combined data from both studies—known as FIT 1 and FIT 2—suggest fostamatinib confers a benefit over placebo.

Therefore, Rigel Pharmaceuticals is still planning to submit a new drug application for fostamatinib to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) next year, pending feedback from the agency.

“We believe that the totality and consistency of data from the FIT phase 3 program . . . strongly supports a clear treatment effect, with a sustained clinical benefit of fostamatinib,” said Raul Rodriguez, president and chief executive officer of Rigel Pharmaceuticals.

“We are encouraged by these results and believe that the risk/benefit ratio for fostamatinib is positive for patients with chronic/persistent ITP . . . . As a result, we will continue to pursue this opportunity. Our next step is to seek feedback from the FDA.”

About the FIT studies

Rigel’s FIT program consists of 2 identical, multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies of approximately 75 adults each—FIT 1 (Study 047) and FIT 2 (Study 048).

The patients enrolled in each study had been diagnosed with persistent or chronic ITP, had failed at least 1 prior therapy for ITP, and had platelet counts consistently below 30,000/uL of blood.

In both studies, patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either fostamatinib or placebo orally twice a day for up to 24 weeks.

Patients were subsequently given the opportunity to enroll in an open-label, long-term, phase 3 extension study (Study 049), which is ongoing.

Patient characteristics

In FIT 1, 51 patients were randomized to fostamatinib and 25 to placebo. The median age was 57 in both treatment arms. The duration of ITP was 7.5 years (range, 0.6-53) in the fostamatinib arm and 5.5 years (range, 0.4-45) in the placebo arm.

Prior treatments (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included steroids (90% and 100%), rituximab (51% and 44%), thrombopoietic agents (50% and 60%), and splenectomy (39% and 40%).

The median platelet count at baseline was 15,000/uL in the fostamatinib arm and 16,000/uL in the placebo arm.

In FIT 2, 50 patients were randomized to fostamatinib and 24 to placebo. The median age was 50 in both treatment arms. The duration of ITP was 8.8 years (range, 0.3-50) in the fostamatinib arm and 10.8 years (range, 0.9-29) in the placebo arm.

Prior treatments (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included steroids (90% and 92%), rituximab (16% and 13%), thrombopoietic agents (40% and 42%), and splenectomy (28% and 38%).

The median platelet count at baseline was 16,000/uL in the fostamatinib arm and 21,000/uL in the placebo arm.

Efficacy

The primary efficacy endpoint in both studies is a stable platelet response, which is defined as achieving platelet counts greater than 50,000/uL of blood for at least 4 of the 6 scheduled clinic visits between weeks 14 and 24 of treatment.

In FIT 1, the rate of stable platelet response was significantly higher in the fostamatinib arm than the placebo arm—18% (n=9) and 0%, respectively (P=0.026).

In FIT 2, however, the difference in stable platelet response between the 2 arms was not significant—18% (n=9) and 4% (n=1), respectively (P=0.152).

When the data from FIT 1 and FIT 2 are combined, the response rate is significantly higher in the fostamatinib arm than the placebo arm—18% (18/101) and 2% (1/49), respectively (P=0.007).

The response rate is significantly better in the fostamatinib arm across all subgroups, regardless of whether patients had prior splenectomy, prior exposure to thrombopoietic agents, or baseline platelet counts above or below 15,000/uL.

In the combined dataset, patients who met the primary endpoint had their platelet counts increase from a median of 18,500/uL at baseline to more than 100,000/uL at week 24 of treatment.

In addition, patients who met the primary endpoint had a timely platelet response, and that response was enduring, according to James B. Bussel, MD, a professor at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York, principal investigator on the FIT phase 3 program, and a member of Rigel’s advisory/scientific board.

“The FIT phase 3 studies have both demonstrated that fostamatinib provided a robust and enduring benefit for those patients who responded to the drug,” he said.

Safety

In FIT 1, the overall incidence of adverse events (AEs) was 96% in the fostamatinib arm and 76% in the placebo arm. The incidence of serious AEs was 16% and 20%, respectively. And the incidence of treatment-related AEs was 77% and 28%, respectively.

AEs (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included gastrointestinal complaints (nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain; 61% and 20%), nausea (29% and 4%), diarrhea (45% and 16%), infection (33% and 20%), hypertension during visit (35% and 8%), and transaminase elevation (22% and 0%).

In FIT 2, the overall incidence of AEs was 71% in the fostamatinib arm and 78% in the placebo arm. The incidence of serious AEs was 10% and 26%, respectively. And the incidence of treatment-related AEs was 39% and 26%, respectively.

AEs (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included gastrointestinal complaints (22% in both arms), nausea (8% and 13%), diarrhea (18% and 13%), infection (22% in both arms), hypertension during visit (20% and 17%), and transaminase elevation (6% and 0%). ![]()

Gene-editing approach is ‘important advance’ in SCD, doc says

sickle cell disease

Image by Graham Beards

Researchers have described a gene-editing technique that can correct the sickle cell mutation in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) isolated from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The investigators said these edited HSPCs produced wild-type adult and fetal hemoglobin.

The HSPCs were also able to engraft in mice and maintained their SCD gene edits long-term without showing any signs of side effects.

“This is an important advance because, for the first time, we show a level of correction in stem cells that should be sufficient for a clinical benefit in persons with sickle cell anemia,” said Mark Walters, MD, of UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland in California.

Dr Walters and his colleagues described this work in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers said they used a ribonucleoprotein complex consisting of Cas9 protein and unmodified single guide RNA, together with a single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide donor, to enable efficient replacement of the SCD mutation in human HSPCs.

The team then differentiated pools of these HSPCs into enucleated erythrocytes and late-stage erythroblasts to measure hemoglobin production.

They said the edited HSPCs produced “substantial amounts” of adult wild-type hemoglobin. The cells also showed a decrease in sickle hemoglobin and an increase in fetal hemoglobin.

When implanted in mice, the edited HSPCs repopulated and maintained their SCD gene edits for 16 weeks, with no signs of side effects. (The mice were sacrificed at 16 weeks.)

“We’re very excited about the promise of this technology,” said study author Jacob Corn, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley.

“There is still a lot of work to be done before this approach might be used in the clinic, but we’re hopeful that it will pave the way for new kinds of treatment for patients with sickle cell disease.”

In fact, Dr Corn and his lab have joined with Dr Walters to initiate an early phase clinical trial to test this gene-editing approach within the next 5 years.

The investigators also noted that the approach might be effective for treating other disorders, such as β-thalassemia, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, and Fanconi anemia.

“Sickle cell disease is just one of many blood disorders caused by a single mutation in the genome,” Dr Corn said. “It’s very possible that other researchers and clinicians could use this type of gene editing to explore ways to cure a large number of diseases.” ![]()

sickle cell disease

Image by Graham Beards

Researchers have described a gene-editing technique that can correct the sickle cell mutation in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) isolated from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The investigators said these edited HSPCs produced wild-type adult and fetal hemoglobin.

The HSPCs were also able to engraft in mice and maintained their SCD gene edits long-term without showing any signs of side effects.

“This is an important advance because, for the first time, we show a level of correction in stem cells that should be sufficient for a clinical benefit in persons with sickle cell anemia,” said Mark Walters, MD, of UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland in California.

Dr Walters and his colleagues described this work in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers said they used a ribonucleoprotein complex consisting of Cas9 protein and unmodified single guide RNA, together with a single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide donor, to enable efficient replacement of the SCD mutation in human HSPCs.

The team then differentiated pools of these HSPCs into enucleated erythrocytes and late-stage erythroblasts to measure hemoglobin production.

They said the edited HSPCs produced “substantial amounts” of adult wild-type hemoglobin. The cells also showed a decrease in sickle hemoglobin and an increase in fetal hemoglobin.

When implanted in mice, the edited HSPCs repopulated and maintained their SCD gene edits for 16 weeks, with no signs of side effects. (The mice were sacrificed at 16 weeks.)

“We’re very excited about the promise of this technology,” said study author Jacob Corn, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley.

“There is still a lot of work to be done before this approach might be used in the clinic, but we’re hopeful that it will pave the way for new kinds of treatment for patients with sickle cell disease.”

In fact, Dr Corn and his lab have joined with Dr Walters to initiate an early phase clinical trial to test this gene-editing approach within the next 5 years.

The investigators also noted that the approach might be effective for treating other disorders, such as β-thalassemia, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, and Fanconi anemia.

“Sickle cell disease is just one of many blood disorders caused by a single mutation in the genome,” Dr Corn said. “It’s very possible that other researchers and clinicians could use this type of gene editing to explore ways to cure a large number of diseases.” ![]()

sickle cell disease

Image by Graham Beards

Researchers have described a gene-editing technique that can correct the sickle cell mutation in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) isolated from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The investigators said these edited HSPCs produced wild-type adult and fetal hemoglobin.

The HSPCs were also able to engraft in mice and maintained their SCD gene edits long-term without showing any signs of side effects.

“This is an important advance because, for the first time, we show a level of correction in stem cells that should be sufficient for a clinical benefit in persons with sickle cell anemia,” said Mark Walters, MD, of UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland in California.

Dr Walters and his colleagues described this work in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers said they used a ribonucleoprotein complex consisting of Cas9 protein and unmodified single guide RNA, together with a single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide donor, to enable efficient replacement of the SCD mutation in human HSPCs.

The team then differentiated pools of these HSPCs into enucleated erythrocytes and late-stage erythroblasts to measure hemoglobin production.

They said the edited HSPCs produced “substantial amounts” of adult wild-type hemoglobin. The cells also showed a decrease in sickle hemoglobin and an increase in fetal hemoglobin.

When implanted in mice, the edited HSPCs repopulated and maintained their SCD gene edits for 16 weeks, with no signs of side effects. (The mice were sacrificed at 16 weeks.)

“We’re very excited about the promise of this technology,” said study author Jacob Corn, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley.

“There is still a lot of work to be done before this approach might be used in the clinic, but we’re hopeful that it will pave the way for new kinds of treatment for patients with sickle cell disease.”

In fact, Dr Corn and his lab have joined with Dr Walters to initiate an early phase clinical trial to test this gene-editing approach within the next 5 years.

The investigators also noted that the approach might be effective for treating other disorders, such as β-thalassemia, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, and Fanconi anemia.

“Sickle cell disease is just one of many blood disorders caused by a single mutation in the genome,” Dr Corn said. “It’s very possible that other researchers and clinicians could use this type of gene editing to explore ways to cure a large number of diseases.” ![]()

Calcium channel blocker reduces cardiac iron loading in thalassemia major

The calcium channel blocker amlodipine, added to iron chelation therapy, significantly reduced excess myocardial iron concentration in patients with thalassemia major, compared with chelation alone, according to results from a randomized trial.

The findings (Blood. 2016;128[12]:1555-61) suggest that amlodipine, a cheap, widely available drug with a well-established safety profile, may serve as an adjunct to standard treatment for people with thalassemia major and cardiac siderosis. Cardiovascular disease caused by excess myocardial iron remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in thalassemia major.

Juliano L. Fernandes, MD, PhD, of the Jose Michel Kalaf Research Institute in Campinas, Brazil, led the study, which randomized 62 patients already receiving chelation treatment for thalassemia major to 1 year of chelation plus placebo (n = 31) or chelation plus 5 mg daily amlodipine (n = 31).

Patients in each arm were subdivided into two subgroups: those whose baseline myocardial iron concentration was within normal thresholds, and those with excess myocardial iron concentration as measured by magnetic resonance imaging (above 0.59 mg/g dry weight or with a cardiac T2* below 35 milliseconds).

In the amlodipine arm, patients with excess cardiac iron at baseline (n = 15) saw significant reductions in myocardial iron concentrations at 1 year, compared with those randomized to placebo (n = 15). The former had a median reduction of –0.26 mg/g (95% confidence interval, –1.02 to –0.01) while the placebo group saw an increase of 0.01 mg/g (95% CI, 20.13 to 20.23; P = .02).

The investigators acknowledged that some of the findings were limited by the study’s short observation period.

Patients without excess myocardial iron concentration at baseline did not see significant changes associated with amlodipine. While Dr. Fernandes and his colleagues could not conclude that the drug prevented excess cardiac iron from accumulating, “our data cannot rule out the possibility that extended use of amlodipine might prevent myocardial iron accumulation with a longer observation period.”

Secondary endpoints of the study included measurements of iron storage in the liver and of serum ferritin, neither of which appeared to be affected by amlodipine treatment, which the investigators said was consistent with the drug’s known mechanism of action. No serious adverse effects were reported related to amlodipine treatment.

Dr. Fernandes and his colleagues also did not find improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction associated with amlodipine use at 12 months. This may be due, they wrote in their analysis, to a “relatively low prevalence of reduced ejection fraction or severe myocardial siderosis upon trial enrollment, limiting the power of the study to assess these outcomes.”

The government of Brazil and the Sultan Bin Khalifa Translational Research Scholarship sponsored the study. Dr. Fernandes reported receiving fees from Novartis and Sanofi. The remaining 12 authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Why is this small clinical trial of such pivotal importance in this day and age of massive multicenter prospective randomized studies? The answer is that it tells us that iron entry into the heart through L-type calcium channels, a mechanism that has been clearly demonstrated in vitro, seems to be actually occurring in humans. As an added bonus, we have a possible new adjunctive treatment of iron cardiomyopathy. More clinical studies are needed, and certainly biochemical studies need to continue because all calcium channel blockers do not have the same effect in vitro, but at least the “channels” for more progress on both clinical and biochemical fronts are now open.

Thomas D. Coates, MD, is with Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles and University of Southern California, Los Angeles. He made his remarks in an editorial that accompanied the published study.

Why is this small clinical trial of such pivotal importance in this day and age of massive multicenter prospective randomized studies? The answer is that it tells us that iron entry into the heart through L-type calcium channels, a mechanism that has been clearly demonstrated in vitro, seems to be actually occurring in humans. As an added bonus, we have a possible new adjunctive treatment of iron cardiomyopathy. More clinical studies are needed, and certainly biochemical studies need to continue because all calcium channel blockers do not have the same effect in vitro, but at least the “channels” for more progress on both clinical and biochemical fronts are now open.

Thomas D. Coates, MD, is with Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles and University of Southern California, Los Angeles. He made his remarks in an editorial that accompanied the published study.

Why is this small clinical trial of such pivotal importance in this day and age of massive multicenter prospective randomized studies? The answer is that it tells us that iron entry into the heart through L-type calcium channels, a mechanism that has been clearly demonstrated in vitro, seems to be actually occurring in humans. As an added bonus, we have a possible new adjunctive treatment of iron cardiomyopathy. More clinical studies are needed, and certainly biochemical studies need to continue because all calcium channel blockers do not have the same effect in vitro, but at least the “channels” for more progress on both clinical and biochemical fronts are now open.

Thomas D. Coates, MD, is with Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles and University of Southern California, Los Angeles. He made his remarks in an editorial that accompanied the published study.

The calcium channel blocker amlodipine, added to iron chelation therapy, significantly reduced excess myocardial iron concentration in patients with thalassemia major, compared with chelation alone, according to results from a randomized trial.

The findings (Blood. 2016;128[12]:1555-61) suggest that amlodipine, a cheap, widely available drug with a well-established safety profile, may serve as an adjunct to standard treatment for people with thalassemia major and cardiac siderosis. Cardiovascular disease caused by excess myocardial iron remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in thalassemia major.

Juliano L. Fernandes, MD, PhD, of the Jose Michel Kalaf Research Institute in Campinas, Brazil, led the study, which randomized 62 patients already receiving chelation treatment for thalassemia major to 1 year of chelation plus placebo (n = 31) or chelation plus 5 mg daily amlodipine (n = 31).

Patients in each arm were subdivided into two subgroups: those whose baseline myocardial iron concentration was within normal thresholds, and those with excess myocardial iron concentration as measured by magnetic resonance imaging (above 0.59 mg/g dry weight or with a cardiac T2* below 35 milliseconds).

In the amlodipine arm, patients with excess cardiac iron at baseline (n = 15) saw significant reductions in myocardial iron concentrations at 1 year, compared with those randomized to placebo (n = 15). The former had a median reduction of –0.26 mg/g (95% confidence interval, –1.02 to –0.01) while the placebo group saw an increase of 0.01 mg/g (95% CI, 20.13 to 20.23; P = .02).

The investigators acknowledged that some of the findings were limited by the study’s short observation period.

Patients without excess myocardial iron concentration at baseline did not see significant changes associated with amlodipine. While Dr. Fernandes and his colleagues could not conclude that the drug prevented excess cardiac iron from accumulating, “our data cannot rule out the possibility that extended use of amlodipine might prevent myocardial iron accumulation with a longer observation period.”

Secondary endpoints of the study included measurements of iron storage in the liver and of serum ferritin, neither of which appeared to be affected by amlodipine treatment, which the investigators said was consistent with the drug’s known mechanism of action. No serious adverse effects were reported related to amlodipine treatment.

Dr. Fernandes and his colleagues also did not find improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction associated with amlodipine use at 12 months. This may be due, they wrote in their analysis, to a “relatively low prevalence of reduced ejection fraction or severe myocardial siderosis upon trial enrollment, limiting the power of the study to assess these outcomes.”

The government of Brazil and the Sultan Bin Khalifa Translational Research Scholarship sponsored the study. Dr. Fernandes reported receiving fees from Novartis and Sanofi. The remaining 12 authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

The calcium channel blocker amlodipine, added to iron chelation therapy, significantly reduced excess myocardial iron concentration in patients with thalassemia major, compared with chelation alone, according to results from a randomized trial.

The findings (Blood. 2016;128[12]:1555-61) suggest that amlodipine, a cheap, widely available drug with a well-established safety profile, may serve as an adjunct to standard treatment for people with thalassemia major and cardiac siderosis. Cardiovascular disease caused by excess myocardial iron remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in thalassemia major.

Juliano L. Fernandes, MD, PhD, of the Jose Michel Kalaf Research Institute in Campinas, Brazil, led the study, which randomized 62 patients already receiving chelation treatment for thalassemia major to 1 year of chelation plus placebo (n = 31) or chelation plus 5 mg daily amlodipine (n = 31).

Patients in each arm were subdivided into two subgroups: those whose baseline myocardial iron concentration was within normal thresholds, and those with excess myocardial iron concentration as measured by magnetic resonance imaging (above 0.59 mg/g dry weight or with a cardiac T2* below 35 milliseconds).

In the amlodipine arm, patients with excess cardiac iron at baseline (n = 15) saw significant reductions in myocardial iron concentrations at 1 year, compared with those randomized to placebo (n = 15). The former had a median reduction of –0.26 mg/g (95% confidence interval, –1.02 to –0.01) while the placebo group saw an increase of 0.01 mg/g (95% CI, 20.13 to 20.23; P = .02).

The investigators acknowledged that some of the findings were limited by the study’s short observation period.

Patients without excess myocardial iron concentration at baseline did not see significant changes associated with amlodipine. While Dr. Fernandes and his colleagues could not conclude that the drug prevented excess cardiac iron from accumulating, “our data cannot rule out the possibility that extended use of amlodipine might prevent myocardial iron accumulation with a longer observation period.”

Secondary endpoints of the study included measurements of iron storage in the liver and of serum ferritin, neither of which appeared to be affected by amlodipine treatment, which the investigators said was consistent with the drug’s known mechanism of action. No serious adverse effects were reported related to amlodipine treatment.

Dr. Fernandes and his colleagues also did not find improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction associated with amlodipine use at 12 months. This may be due, they wrote in their analysis, to a “relatively low prevalence of reduced ejection fraction or severe myocardial siderosis upon trial enrollment, limiting the power of the study to assess these outcomes.”

The government of Brazil and the Sultan Bin Khalifa Translational Research Scholarship sponsored the study. Dr. Fernandes reported receiving fees from Novartis and Sanofi. The remaining 12 authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM BLOOD

Key clinical point: Amlodipine added to standard chelation therapy significantly reduced cardiac iron in thalassemia major patients with cardiac siderosis.

Major finding: At 12 months, cardiac iron was a median 0.26 mg/g lower in subjects with myocardial iron overload treated with 5 mg daily amlodipine plus chelation, while patients treated with chelation alone saw a 0.01 mg/g increase (P = .02).

Data source: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial enrolling from 62 patients with TM from six centers in Brazil, about half with cardiac siderosis at baseline.

Disclosures: The Brazil government and the Sultan Bin Khalifa Translational Research Scholarship sponsored the investigation. Its lead author reported receiving fees from Novartis and Sanofi. Other study investigators and the author of a linked editorial declared no conflicts of interest.

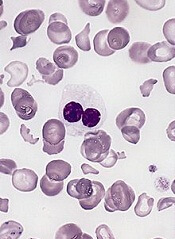

Lifestyle may impact life expectancy in mild SCD

alongside a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

A case series published in Blood indicates that some patients with mildly symptomatic sickle cell disease (SCD) can live long lives if they

comply with treatment recommendations and lead a healthy lifestyle.

The paper includes details on 4 women with milder forms of SCD who survived beyond age 80.

“For those with mild forms of SCD, these women show that lifestyle modifications may improve disease outcomes,” said author Samir K. Ballas, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Three of the women described in this case series were treated at the Sickle Cell Center of Thomas Jefferson University, and 1 was treated in Brazil’s Instituto de Hematologia Arthur de Siqueira Cavalcanti in Rio de Janeiro.

The women had different ancestries—2 African-American, 1 Italian-American, and 1 African-Brazilian—and different diagnoses—2 with hemoglobin SC disease and 2 with sickle cell anemia. But all 4 women had what Dr Ballas called “desirable” disease states.

“These women never had a stroke, never had recurrent acute chest syndrome, had a relatively high fetal hemoglobin count, and had infrequent painful crises,” Dr Ballas said. “Patients like this usually—but not always—experience relatively mild SCD, and they live longer with better quality of life.”

In addition, all of the women took steps to maintain and improve their health and had long-term family support. Dr Ballas said these factors likely contributed to the women’s long lives and high quality of life.

“All of the women were non-smokers who consumed little to no alcohol and maintained a normal body mass index,” he said. “This was coupled with a strong compliance to their treatment regimens and excellent family support at home.”

Family support was defined as having a spouse or child who provided attentive, ongoing care. And all of the women had at least 1 such caregiver.

Treatment compliance was based on observations by healthcare providers, including study authors. According to these observations, all of the women showed “excellent” adherence when it came to medication intake, appointments, and referrals.

As the women had relatively mild disease states, none of them were qualified to receive treatment with hydroxyurea. Instead, they received hydration, vaccination (including annual flu shots), and blood transfusion and analgesics as needed.

Even with their mild disease states and healthy lifestyles, these women did not live crisis-free lives. Each experienced disease-related complications necessitating medical attention.

The women had 0 to 3 vaso-occlusive crises per year. Two women required frequent transfusions (and had iron overload), and 2 required occasional transfusions. One woman had 2 episodes of acute chest syndrome, and the second episode led to her death.

Ultimately, 3 of the women died. One died of acute chest syndrome and septicemia at age 82, and another died of cardiac complications at age 86. For a third woman, the cause of death, at age 82, was unknown. The fourth woman remains alive at age 82.

As the median life expectancy of women with SCD in the US is 47, Dr Ballas and his colleagues said these 4 women may “provide a blueprint of how to live a long life despite having a serious medical condition like SCD.”

“I would often come out to the waiting room and find these ladies talking with other SCD patients, and I could tell that they gave others hope, that just because they have SCD does not mean that they are doomed to die by their 40s . . . ,” Dr Ballas said. “[I]f they take care of themselves and live closely with those who can help keep them well, that there is hope for them to lead long, full lives.” ![]()

alongside a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

A case series published in Blood indicates that some patients with mildly symptomatic sickle cell disease (SCD) can live long lives if they

comply with treatment recommendations and lead a healthy lifestyle.

The paper includes details on 4 women with milder forms of SCD who survived beyond age 80.

“For those with mild forms of SCD, these women show that lifestyle modifications may improve disease outcomes,” said author Samir K. Ballas, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Three of the women described in this case series were treated at the Sickle Cell Center of Thomas Jefferson University, and 1 was treated in Brazil’s Instituto de Hematologia Arthur de Siqueira Cavalcanti in Rio de Janeiro.

The women had different ancestries—2 African-American, 1 Italian-American, and 1 African-Brazilian—and different diagnoses—2 with hemoglobin SC disease and 2 with sickle cell anemia. But all 4 women had what Dr Ballas called “desirable” disease states.

“These women never had a stroke, never had recurrent acute chest syndrome, had a relatively high fetal hemoglobin count, and had infrequent painful crises,” Dr Ballas said. “Patients like this usually—but not always—experience relatively mild SCD, and they live longer with better quality of life.”

In addition, all of the women took steps to maintain and improve their health and had long-term family support. Dr Ballas said these factors likely contributed to the women’s long lives and high quality of life.

“All of the women were non-smokers who consumed little to no alcohol and maintained a normal body mass index,” he said. “This was coupled with a strong compliance to their treatment regimens and excellent family support at home.”

Family support was defined as having a spouse or child who provided attentive, ongoing care. And all of the women had at least 1 such caregiver.

Treatment compliance was based on observations by healthcare providers, including study authors. According to these observations, all of the women showed “excellent” adherence when it came to medication intake, appointments, and referrals.

As the women had relatively mild disease states, none of them were qualified to receive treatment with hydroxyurea. Instead, they received hydration, vaccination (including annual flu shots), and blood transfusion and analgesics as needed.

Even with their mild disease states and healthy lifestyles, these women did not live crisis-free lives. Each experienced disease-related complications necessitating medical attention.

The women had 0 to 3 vaso-occlusive crises per year. Two women required frequent transfusions (and had iron overload), and 2 required occasional transfusions. One woman had 2 episodes of acute chest syndrome, and the second episode led to her death.

Ultimately, 3 of the women died. One died of acute chest syndrome and septicemia at age 82, and another died of cardiac complications at age 86. For a third woman, the cause of death, at age 82, was unknown. The fourth woman remains alive at age 82.

As the median life expectancy of women with SCD in the US is 47, Dr Ballas and his colleagues said these 4 women may “provide a blueprint of how to live a long life despite having a serious medical condition like SCD.”

“I would often come out to the waiting room and find these ladies talking with other SCD patients, and I could tell that they gave others hope, that just because they have SCD does not mean that they are doomed to die by their 40s . . . ,” Dr Ballas said. “[I]f they take care of themselves and live closely with those who can help keep them well, that there is hope for them to lead long, full lives.” ![]()

alongside a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

A case series published in Blood indicates that some patients with mildly symptomatic sickle cell disease (SCD) can live long lives if they

comply with treatment recommendations and lead a healthy lifestyle.

The paper includes details on 4 women with milder forms of SCD who survived beyond age 80.

“For those with mild forms of SCD, these women show that lifestyle modifications may improve disease outcomes,” said author Samir K. Ballas, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Three of the women described in this case series were treated at the Sickle Cell Center of Thomas Jefferson University, and 1 was treated in Brazil’s Instituto de Hematologia Arthur de Siqueira Cavalcanti in Rio de Janeiro.

The women had different ancestries—2 African-American, 1 Italian-American, and 1 African-Brazilian—and different diagnoses—2 with hemoglobin SC disease and 2 with sickle cell anemia. But all 4 women had what Dr Ballas called “desirable” disease states.

“These women never had a stroke, never had recurrent acute chest syndrome, had a relatively high fetal hemoglobin count, and had infrequent painful crises,” Dr Ballas said. “Patients like this usually—but not always—experience relatively mild SCD, and they live longer with better quality of life.”

In addition, all of the women took steps to maintain and improve their health and had long-term family support. Dr Ballas said these factors likely contributed to the women’s long lives and high quality of life.

“All of the women were non-smokers who consumed little to no alcohol and maintained a normal body mass index,” he said. “This was coupled with a strong compliance to their treatment regimens and excellent family support at home.”

Family support was defined as having a spouse or child who provided attentive, ongoing care. And all of the women had at least 1 such caregiver.

Treatment compliance was based on observations by healthcare providers, including study authors. According to these observations, all of the women showed “excellent” adherence when it came to medication intake, appointments, and referrals.

As the women had relatively mild disease states, none of them were qualified to receive treatment with hydroxyurea. Instead, they received hydration, vaccination (including annual flu shots), and blood transfusion and analgesics as needed.

Even with their mild disease states and healthy lifestyles, these women did not live crisis-free lives. Each experienced disease-related complications necessitating medical attention.

The women had 0 to 3 vaso-occlusive crises per year. Two women required frequent transfusions (and had iron overload), and 2 required occasional transfusions. One woman had 2 episodes of acute chest syndrome, and the second episode led to her death.

Ultimately, 3 of the women died. One died of acute chest syndrome and septicemia at age 82, and another died of cardiac complications at age 86. For a third woman, the cause of death, at age 82, was unknown. The fourth woman remains alive at age 82.

As the median life expectancy of women with SCD in the US is 47, Dr Ballas and his colleagues said these 4 women may “provide a blueprint of how to live a long life despite having a serious medical condition like SCD.”

“I would often come out to the waiting room and find these ladies talking with other SCD patients, and I could tell that they gave others hope, that just because they have SCD does not mean that they are doomed to die by their 40s . . . ,” Dr Ballas said. “[I]f they take care of themselves and live closely with those who can help keep them well, that there is hope for them to lead long, full lives.” ![]()

Inflammation may predict transformation to AML

Inflammatory signaling in mesenchymal niche cells can be used to predict the transformation from pre-leukemic syndrome to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to preclinical research published in Cell Stem Cell.

“This discovery sheds new light on the long-standing association between inflammation and cancer,” said study author Marc Raaijmakers, MD, PhD, of the Erasmus MC Cancer Institute in Rotterdam, Netherlands.

“The elucidation of the molecular mechanism underlying this concept opens the prospect of improved diagnosis of patients at increased risk for the development of leukemia and the potential of future, niche-targeted therapy to delay or prevent the development of leukemia.”

In a previous study, Dr Raaijmakers and his colleagues discovered that mutations in mesenchymal progenitor cells can induce myelodysplasia in mice and promote the development of AML.

With the current study, the researchers wanted to build upon those findings by identifying the underlying mechanisms and determining their relevance to human disease.

So the team performed massive parallel RNA sequencing of mesenchymal cells in mice with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome and bone marrow samples from patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, Diamond-Blackfan anemia, and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The researchers found that mesenchymal cells in these pre-leukemic disorders are under stress. The stress leads to the release of inflammatory molecules called S100A8 and S100A9, which cause mitochondrial and DNA damage in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.

The team also found that activation of this inflammatory pathway in mesenchymal cells predicted the development of AML and clinical outcomes in patients with MDS.

Leukemic evolution occurred in 29.4% (5/17) of MDS patients whose mesenchymal cells overexpressed S100A8/9 and 14.2% (4/28) of MDS patients without S100A8/9 overexpression.

The time to leukemic evolution and the length of progression-free survival were both significantly shorter in niche S100A8/9+ patients than niche S100A8/9- patients.

The average time to leukemic evolution was 3.4 months and 18.5 months, respectively (P=0.03). And the median progression-free survival was 11.5 months and 53 months, respectively (P=0.03)

The researchers believe these findings, if confirmed in subsequent studies, could lead to the development of tests to identify patients with pre-leukemic syndromes who have a high risk of developing AML.

“These high-risk patients could be treated more aggressively at an earlier stage, thereby preventing or slowing down disease progression,” Dr Raaijmakers said. “Moreover, the findings suggest that new drugs targeting the inflammatory pathway should be tested in future preclinical studies.” ![]()

Inflammatory signaling in mesenchymal niche cells can be used to predict the transformation from pre-leukemic syndrome to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to preclinical research published in Cell Stem Cell.

“This discovery sheds new light on the long-standing association between inflammation and cancer,” said study author Marc Raaijmakers, MD, PhD, of the Erasmus MC Cancer Institute in Rotterdam, Netherlands.

“The elucidation of the molecular mechanism underlying this concept opens the prospect of improved diagnosis of patients at increased risk for the development of leukemia and the potential of future, niche-targeted therapy to delay or prevent the development of leukemia.”

In a previous study, Dr Raaijmakers and his colleagues discovered that mutations in mesenchymal progenitor cells can induce myelodysplasia in mice and promote the development of AML.

With the current study, the researchers wanted to build upon those findings by identifying the underlying mechanisms and determining their relevance to human disease.

So the team performed massive parallel RNA sequencing of mesenchymal cells in mice with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome and bone marrow samples from patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, Diamond-Blackfan anemia, and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The researchers found that mesenchymal cells in these pre-leukemic disorders are under stress. The stress leads to the release of inflammatory molecules called S100A8 and S100A9, which cause mitochondrial and DNA damage in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.

The team also found that activation of this inflammatory pathway in mesenchymal cells predicted the development of AML and clinical outcomes in patients with MDS.

Leukemic evolution occurred in 29.4% (5/17) of MDS patients whose mesenchymal cells overexpressed S100A8/9 and 14.2% (4/28) of MDS patients without S100A8/9 overexpression.

The time to leukemic evolution and the length of progression-free survival were both significantly shorter in niche S100A8/9+ patients than niche S100A8/9- patients.

The average time to leukemic evolution was 3.4 months and 18.5 months, respectively (P=0.03). And the median progression-free survival was 11.5 months and 53 months, respectively (P=0.03)

The researchers believe these findings, if confirmed in subsequent studies, could lead to the development of tests to identify patients with pre-leukemic syndromes who have a high risk of developing AML.

“These high-risk patients could be treated more aggressively at an earlier stage, thereby preventing or slowing down disease progression,” Dr Raaijmakers said. “Moreover, the findings suggest that new drugs targeting the inflammatory pathway should be tested in future preclinical studies.” ![]()

Inflammatory signaling in mesenchymal niche cells can be used to predict the transformation from pre-leukemic syndrome to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to preclinical research published in Cell Stem Cell.

“This discovery sheds new light on the long-standing association between inflammation and cancer,” said study author Marc Raaijmakers, MD, PhD, of the Erasmus MC Cancer Institute in Rotterdam, Netherlands.

“The elucidation of the molecular mechanism underlying this concept opens the prospect of improved diagnosis of patients at increased risk for the development of leukemia and the potential of future, niche-targeted therapy to delay or prevent the development of leukemia.”

In a previous study, Dr Raaijmakers and his colleagues discovered that mutations in mesenchymal progenitor cells can induce myelodysplasia in mice and promote the development of AML.

With the current study, the researchers wanted to build upon those findings by identifying the underlying mechanisms and determining their relevance to human disease.

So the team performed massive parallel RNA sequencing of mesenchymal cells in mice with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome and bone marrow samples from patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, Diamond-Blackfan anemia, and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The researchers found that mesenchymal cells in these pre-leukemic disorders are under stress. The stress leads to the release of inflammatory molecules called S100A8 and S100A9, which cause mitochondrial and DNA damage in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.

The team also found that activation of this inflammatory pathway in mesenchymal cells predicted the development of AML and clinical outcomes in patients with MDS.

Leukemic evolution occurred in 29.4% (5/17) of MDS patients whose mesenchymal cells overexpressed S100A8/9 and 14.2% (4/28) of MDS patients without S100A8/9 overexpression.

The time to leukemic evolution and the length of progression-free survival were both significantly shorter in niche S100A8/9+ patients than niche S100A8/9- patients.

The average time to leukemic evolution was 3.4 months and 18.5 months, respectively (P=0.03). And the median progression-free survival was 11.5 months and 53 months, respectively (P=0.03)

The researchers believe these findings, if confirmed in subsequent studies, could lead to the development of tests to identify patients with pre-leukemic syndromes who have a high risk of developing AML.

“These high-risk patients could be treated more aggressively at an earlier stage, thereby preventing or slowing down disease progression,” Dr Raaijmakers said. “Moreover, the findings suggest that new drugs targeting the inflammatory pathway should be tested in future preclinical studies.” ![]()

Drug could reduce morbidity, mortality in aTTP, doc says

Photo courtesy of ASH

THE HAGUE—Caplacizumab has the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP), according to the principal investigator of the phase 2 TITAN study.

Post-hoc analyses of data from this study suggested that adding caplacizumab to standard therapy can reduce major thromboembolic complications and aTTP-related death, as well as refractoriness to standard treatment.

These findings were recently presented at the European Congress on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ECTH). The study was sponsored by Ablynx, the company developing caplacizumab.

Caplacizumab is an anti-von Willebrand factor nanobody that works by blocking the interaction of ultra-large von Willebrand factor multimers with platelets.

According to Ablynx, the nanobody has an immediate effect on platelet aggregation and the ensuing formation and accumulation of the micro-clots that cause severe thrombocytopenia and organ and tissue damage in patients with aTTP. This immediate effect protects the patient from the manifestations of the disease while the underlying disease process resolves.

Previous results from TITAN

TITAN was a single-blinded study that enrolled 75 aTTP patients. They all received the current standard of care for aTTP—daily plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy. Thirty-six patients were randomized to receive caplacizumab as well, and 39 were randomized to placebo.

The study’s primary endpoint was time to response (platelet count normalization). Patients in the caplacizumab arm had a 39% reduction in the median time to response compared to patients in the placebo arm (P=0.005).

The rate of confirmed response was 86.1% (n=31) in the caplacizumab arm and 71.8% (n=28) in the placebo arm.

There were more relapses in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—8 (22.2%) and 0, respectively. Relapse was defined as a TTP event occurring more than 30 days after the end of daily plasma exchange.

There were fewer exacerbations in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—3 (8.3%) and 11 (28.2%), respectively. Exacerbation was defined as recurrent thrombocytopenia within 30 days of the end of daily plasma exchange that required reinitiation of daily exchange.

The rate of adverse events thought to be related to the study drug was 17% in the caplacizumab arm and 11% in the placebo arm. The rate of events that were possibly related was 54% and 8%, respectively.

These and other results from TITAN were published in NEJM earlier this year.

Post-hoc analyses

Investigators performed post-hoc analyses of TITAN data to assess the impact of caplacizumab on a composite endpoint of major thromboembolic complications and aTTP-related mortality, as well as on refractoriness to standard treatment.

The proportion of patients who died or had at least 1 major thromboembolic event was lower in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—11.4% and 43.2%, respectively.

There were 4 major thromboembolic events in the caplacizumab arm—3 recurrences of TTP during the treatment period and 1 pulmonary embolism.

There were 20 major thromboembolic events in the placebo arm—13 recurrences of TTP during the treatment period (in 11 patients), 2 acute myocardial infarctions, 1 deep vein thrombosis, 1 venous thrombosis, 1 pulmonary embolism, 1 ischemic stroke, and 1 hemorrhagic stroke.

There were no deaths in the caplacizumab arm, but there were 2 deaths in the placebo arm. Both of those patients were refractory to treatment.

Fewer patients in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm were refractory to treatment.

When refractoriness was defined as “failure of platelet response after 7 days despite daily plasma exchange treatment,” the rates of refractoriness were 5.7% in the caplacizumab arm and 21.6% in the placebo arm.

When refractoriness was defined as “absence of platelet count doubling after 4 days of standard treatment and lactate dehydrogenase greater than the upper limit of normal,” the rates of refractoriness were 0% in the caplacizumab arm and 10.8% in the placebo arm.

“Acquired TTP is a very severe disease with high unmet medical need,” said TITAN’s principal investigator Flora Peyvandi, MD, PhD, of the University of Milan in Italy.

“Any new treatment option would need to act fast to immediately inhibit the formation of micro-clots in order to protect the patient during the acute phase of the disease and so have the potential to avoid the resulting complications.”

“The top-line results and the subsequent post-hoc analyses of the phase 2 TITAN data demonstrate that caplacizumab has the potential to reduce the major morbidity and mortality associated with acquired TTP, and confirm our conviction that it should become an important pillar in the management of acquired TTP.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of ASH

THE HAGUE—Caplacizumab has the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP), according to the principal investigator of the phase 2 TITAN study.

Post-hoc analyses of data from this study suggested that adding caplacizumab to standard therapy can reduce major thromboembolic complications and aTTP-related death, as well as refractoriness to standard treatment.

These findings were recently presented at the European Congress on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ECTH). The study was sponsored by Ablynx, the company developing caplacizumab.

Caplacizumab is an anti-von Willebrand factor nanobody that works by blocking the interaction of ultra-large von Willebrand factor multimers with platelets.