User login

Study reveals potential strategy for treating leukemia

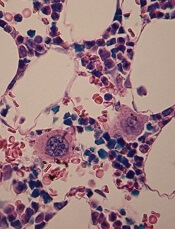

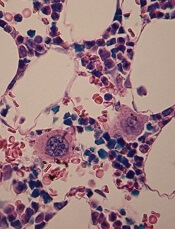

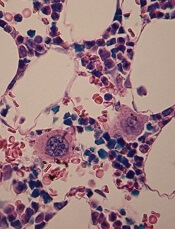

The protein kinases Cdk4 and Cdk6 may determine the incidence and aggressiveness of leukemia, according to preclinical research.

The study showed that Cdk4 and Cdk6 cooperate to promote hematopoietic tumor development in mice.

And inhibiting Cdk4 and Cdk6 simultaneously proved a more effective method of fighting leukemia than inhibiting either protein alone.

The researchers recounted these findings in Blood.

“Cdk4/6 inhibitors used in cancer treatment don’t differentiate between the two molecules,” said study author Marcos Malumbres, PhD, of the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO).

“The effectiveness of blocking both proteins at once has not been demonstrated to date.”

To get a wider perspective on this issue, Dr Malumbres and his colleagues designed genetically modified mice carrying active Cdk4, active Cdk6, or both versions of the active proteins.

The researchers found that simultaneous activation of both proteins promoted tumor growth in the mice, leading to more aggressive tumors and an increased risk of developing leukemia.

The team also found an explanation for why the simultaneous activation of Cdk4 and Cdk6 leads to such aggressive tumors.

Under normal conditions, Cdk4 and Cdk6 are inhibited by p16INK4A proteins. But when both Cdk4 and Cdk6 are present at high levels, p16INK4A proteins are unable to act as a retaining wall, leading to uncontrolled tumor growth.

“The assumption to date has been that these molecules act independently of each other,” Dr Malumbres said. “However, our recent findings now suggest that the combined inhibitors could be a more effective cancer treatment.”

“The clinical success of these compounds depends on the appropriate selection of patients. Our findings could help us to understand the molecular basis underpinning the success of these inhibitors, thereby contributing to the development of novel and more effective drugs.” ![]()

The protein kinases Cdk4 and Cdk6 may determine the incidence and aggressiveness of leukemia, according to preclinical research.

The study showed that Cdk4 and Cdk6 cooperate to promote hematopoietic tumor development in mice.

And inhibiting Cdk4 and Cdk6 simultaneously proved a more effective method of fighting leukemia than inhibiting either protein alone.

The researchers recounted these findings in Blood.

“Cdk4/6 inhibitors used in cancer treatment don’t differentiate between the two molecules,” said study author Marcos Malumbres, PhD, of the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO).

“The effectiveness of blocking both proteins at once has not been demonstrated to date.”

To get a wider perspective on this issue, Dr Malumbres and his colleagues designed genetically modified mice carrying active Cdk4, active Cdk6, or both versions of the active proteins.

The researchers found that simultaneous activation of both proteins promoted tumor growth in the mice, leading to more aggressive tumors and an increased risk of developing leukemia.

The team also found an explanation for why the simultaneous activation of Cdk4 and Cdk6 leads to such aggressive tumors.

Under normal conditions, Cdk4 and Cdk6 are inhibited by p16INK4A proteins. But when both Cdk4 and Cdk6 are present at high levels, p16INK4A proteins are unable to act as a retaining wall, leading to uncontrolled tumor growth.

“The assumption to date has been that these molecules act independently of each other,” Dr Malumbres said. “However, our recent findings now suggest that the combined inhibitors could be a more effective cancer treatment.”

“The clinical success of these compounds depends on the appropriate selection of patients. Our findings could help us to understand the molecular basis underpinning the success of these inhibitors, thereby contributing to the development of novel and more effective drugs.” ![]()

The protein kinases Cdk4 and Cdk6 may determine the incidence and aggressiveness of leukemia, according to preclinical research.

The study showed that Cdk4 and Cdk6 cooperate to promote hematopoietic tumor development in mice.

And inhibiting Cdk4 and Cdk6 simultaneously proved a more effective method of fighting leukemia than inhibiting either protein alone.

The researchers recounted these findings in Blood.

“Cdk4/6 inhibitors used in cancer treatment don’t differentiate between the two molecules,” said study author Marcos Malumbres, PhD, of the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO).

“The effectiveness of blocking both proteins at once has not been demonstrated to date.”

To get a wider perspective on this issue, Dr Malumbres and his colleagues designed genetically modified mice carrying active Cdk4, active Cdk6, or both versions of the active proteins.

The researchers found that simultaneous activation of both proteins promoted tumor growth in the mice, leading to more aggressive tumors and an increased risk of developing leukemia.

The team also found an explanation for why the simultaneous activation of Cdk4 and Cdk6 leads to such aggressive tumors.

Under normal conditions, Cdk4 and Cdk6 are inhibited by p16INK4A proteins. But when both Cdk4 and Cdk6 are present at high levels, p16INK4A proteins are unable to act as a retaining wall, leading to uncontrolled tumor growth.

“The assumption to date has been that these molecules act independently of each other,” Dr Malumbres said. “However, our recent findings now suggest that the combined inhibitors could be a more effective cancer treatment.”

“The clinical success of these compounds depends on the appropriate selection of patients. Our findings could help us to understand the molecular basis underpinning the success of these inhibitors, thereby contributing to the development of novel and more effective drugs.” ![]()

FDA allows access to pathogen inactivation system

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authorized the use of a pathogen inactivation system in regions of the US and its territories affected by outbreaks of Chikungunya and dengue virus.

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets is used for the preparation and storage of whole blood-derived and apheresis platelets.

The system can inactivate a range of viruses, bacteria, and parasites to reduce the risk of transmission via platelet transfusion. It can also prevent transfusion-associated graft-vs-host disease and reduce the risk of other adverse effects due to transfusion of contaminating donor leukocytes.

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets has not been granted full FDA approval. The agency has approved use of the system via an investigational device exemption (IDE).

This allows for early access to a device not yet approved in the US when no satisfactory alternative is available to treat patients with serious or life-threatening conditions.

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets will initially be available to sites in Puerto Rico that agree to participate in a clinical study. Depending on the scope of participation there, the system may be made available to sites in other areas where cases of Chikungunya and dengue have been reported, such as Florida and Texas.

“We are pleased to provide US blood centers and hospitals early access to INTERCEPT for the treatment of platelet components in light of the escalating threat of Chikungunya and dengue transfusion-transmitted infections,” said Carol Moore, of Cerus Corporation, the company developing the INTERCEPT system.

“With this expeditious approval of our IDE, we hope to initiate our first study site before year-end.”

About the system

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets is based on the premise that platelets don’t require functional DNA or RNA, but pathogens and contaminating leukocytes do. The system deploys proprietary molecules that, when activated, bind to and block the replication of DNA and RNA in the blood.

The system uses amotosalen HCl (a photoactive compound) and long-wavelength ultraviolet illumination to photochemically treat platelet components, rendering susceptible pathogens incapable of replicating and causing disease.

Published studies have demonstrated INTERCEPT inactivation of >6.4 log of Chikungunya and >5.3 log of dengue infectious titers, both in excess of observed titers in asymptomatic donors.

The INTERCEPT platelet system has been approved in Europe since 2002 and is currently used at more than 100 blood centers in 20 countries. The system is under regulatory review in the US, Canada, Brazil, and China.

About dengue and Chikungunya

Dengue virus is endemic to the Caribbean region. Local transmission of Chikungunya virus was detected in the Caribbean for the first time in February 2014. Both viruses are spread by species of mosquitoes common in tropical climates and regions within the continental US.

As of September 30, 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported 11 confirmed locally transmitted cases of Chikungunya in

Florida, 421 cases in Puerto Rico, and 45 cases in the US Virgin Islands. Local transmission of dengue has also been reported in Texas and Florida.

Chikungunya virus causes high fevers, joint pain and swelling, headaches, and a rash. Symptoms have been reported to persist for up to 2 years in chronic cases. Rarely, Chikungunya can be fatal.

Symptoms of dengue include high fever, headaches, joint and muscle pain, vomiting, and a rash. In some cases, dengue infection is life-threatening due to dengue hemorrhagic fever, which causes bleeding from the nose, gums, or under the skin. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authorized the use of a pathogen inactivation system in regions of the US and its territories affected by outbreaks of Chikungunya and dengue virus.

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets is used for the preparation and storage of whole blood-derived and apheresis platelets.

The system can inactivate a range of viruses, bacteria, and parasites to reduce the risk of transmission via platelet transfusion. It can also prevent transfusion-associated graft-vs-host disease and reduce the risk of other adverse effects due to transfusion of contaminating donor leukocytes.

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets has not been granted full FDA approval. The agency has approved use of the system via an investigational device exemption (IDE).

This allows for early access to a device not yet approved in the US when no satisfactory alternative is available to treat patients with serious or life-threatening conditions.

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets will initially be available to sites in Puerto Rico that agree to participate in a clinical study. Depending on the scope of participation there, the system may be made available to sites in other areas where cases of Chikungunya and dengue have been reported, such as Florida and Texas.

“We are pleased to provide US blood centers and hospitals early access to INTERCEPT for the treatment of platelet components in light of the escalating threat of Chikungunya and dengue transfusion-transmitted infections,” said Carol Moore, of Cerus Corporation, the company developing the INTERCEPT system.

“With this expeditious approval of our IDE, we hope to initiate our first study site before year-end.”

About the system

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets is based on the premise that platelets don’t require functional DNA or RNA, but pathogens and contaminating leukocytes do. The system deploys proprietary molecules that, when activated, bind to and block the replication of DNA and RNA in the blood.

The system uses amotosalen HCl (a photoactive compound) and long-wavelength ultraviolet illumination to photochemically treat platelet components, rendering susceptible pathogens incapable of replicating and causing disease.

Published studies have demonstrated INTERCEPT inactivation of >6.4 log of Chikungunya and >5.3 log of dengue infectious titers, both in excess of observed titers in asymptomatic donors.

The INTERCEPT platelet system has been approved in Europe since 2002 and is currently used at more than 100 blood centers in 20 countries. The system is under regulatory review in the US, Canada, Brazil, and China.

About dengue and Chikungunya

Dengue virus is endemic to the Caribbean region. Local transmission of Chikungunya virus was detected in the Caribbean for the first time in February 2014. Both viruses are spread by species of mosquitoes common in tropical climates and regions within the continental US.

As of September 30, 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported 11 confirmed locally transmitted cases of Chikungunya in

Florida, 421 cases in Puerto Rico, and 45 cases in the US Virgin Islands. Local transmission of dengue has also been reported in Texas and Florida.

Chikungunya virus causes high fevers, joint pain and swelling, headaches, and a rash. Symptoms have been reported to persist for up to 2 years in chronic cases. Rarely, Chikungunya can be fatal.

Symptoms of dengue include high fever, headaches, joint and muscle pain, vomiting, and a rash. In some cases, dengue infection is life-threatening due to dengue hemorrhagic fever, which causes bleeding from the nose, gums, or under the skin. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authorized the use of a pathogen inactivation system in regions of the US and its territories affected by outbreaks of Chikungunya and dengue virus.

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets is used for the preparation and storage of whole blood-derived and apheresis platelets.

The system can inactivate a range of viruses, bacteria, and parasites to reduce the risk of transmission via platelet transfusion. It can also prevent transfusion-associated graft-vs-host disease and reduce the risk of other adverse effects due to transfusion of contaminating donor leukocytes.

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets has not been granted full FDA approval. The agency has approved use of the system via an investigational device exemption (IDE).

This allows for early access to a device not yet approved in the US when no satisfactory alternative is available to treat patients with serious or life-threatening conditions.

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets will initially be available to sites in Puerto Rico that agree to participate in a clinical study. Depending on the scope of participation there, the system may be made available to sites in other areas where cases of Chikungunya and dengue have been reported, such as Florida and Texas.

“We are pleased to provide US blood centers and hospitals early access to INTERCEPT for the treatment of platelet components in light of the escalating threat of Chikungunya and dengue transfusion-transmitted infections,” said Carol Moore, of Cerus Corporation, the company developing the INTERCEPT system.

“With this expeditious approval of our IDE, we hope to initiate our first study site before year-end.”

About the system

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets is based on the premise that platelets don’t require functional DNA or RNA, but pathogens and contaminating leukocytes do. The system deploys proprietary molecules that, when activated, bind to and block the replication of DNA and RNA in the blood.

The system uses amotosalen HCl (a photoactive compound) and long-wavelength ultraviolet illumination to photochemically treat platelet components, rendering susceptible pathogens incapable of replicating and causing disease.

Published studies have demonstrated INTERCEPT inactivation of >6.4 log of Chikungunya and >5.3 log of dengue infectious titers, both in excess of observed titers in asymptomatic donors.

The INTERCEPT platelet system has been approved in Europe since 2002 and is currently used at more than 100 blood centers in 20 countries. The system is under regulatory review in the US, Canada, Brazil, and China.

About dengue and Chikungunya

Dengue virus is endemic to the Caribbean region. Local transmission of Chikungunya virus was detected in the Caribbean for the first time in February 2014. Both viruses are spread by species of mosquitoes common in tropical climates and regions within the continental US.

As of September 30, 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported 11 confirmed locally transmitted cases of Chikungunya in

Florida, 421 cases in Puerto Rico, and 45 cases in the US Virgin Islands. Local transmission of dengue has also been reported in Texas and Florida.

Chikungunya virus causes high fevers, joint pain and swelling, headaches, and a rash. Symptoms have been reported to persist for up to 2 years in chronic cases. Rarely, Chikungunya can be fatal.

Symptoms of dengue include high fever, headaches, joint and muscle pain, vomiting, and a rash. In some cases, dengue infection is life-threatening due to dengue hemorrhagic fever, which causes bleeding from the nose, gums, or under the skin. ![]()

Research could aid platelet production

in the bone marrow

Scientists say they’ve shed new light on the mechanism of platelet formation, paving the way to accelerating and enhancing platelet production using stem cells.

The group uncovered their findings by studying the effects of shear stress on megakaryocyte maturation and the formation of preplatelets, platelet-like particles, and megakaryocyte microparticles.

“Until recently, these microparticles were viewed as inconsequential cell debris,” said Terry Papoutsakis, PhD, of the University of Delaware in Newark.

“We now know that they play a significant biological role in platelet formation. The enhanced generation of preplatelets and platelet-like particles under shear stress correlates with physiological observations—in healthy adults, both acute and prolonged exercise leads to elevated platelet counts.”

“Now, these findings can be used to develop better bioreactor technologies for producing platelets, preplatelets, platelet-like particles, and megakaryocyte microparticles for transfusion medicine, using stem cells as starting material.”

Dr Papoutsakis and his colleagues described these findings in Blood.

The researchers discovered that shear stress accelerated DNA synthesis of immature megakaryocytes, and this was dependent upon exposure time and the shear stress level.

Physiological shear stress increased the formation of preplatelets and platelet-like particles up to 10.8-fold. And it increased megakaryocyte microparticle production up to 47-fold. Platelet-like particles generated under shear flow showed improved function.

Experiments also revealed that phosphatidylserine exposure and caspase-3 activation were enhanced by shear stress. But inhibiting caspase-3 reduced the formation of preplatelets, platelet-like particles, and megakaryocyte microparticles.

Finally, the researchers found that coculturing megakaryocyte microparticles with hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells promoted differentiation to mature megakaryocytes that synthesized α- and dense-granules, and formed preplatelets without exogenous thrombopoietin.

The team noted that, unlike platelets themselves, these microparticles can be frozen, which will enable them to be stored and used for platelet production on an as-needed basis.

“Knowing that these microparticles have a biological function opens the door to other applications, including genetic therapies,” Dr Papoutsakis said. “We’re hopeful that our discovery can break the vicious cycle of [immune thrombocytopenia] as well as other conditions that cause reduced platelet count and cause life-threatening bleeding.” ![]()

in the bone marrow

Scientists say they’ve shed new light on the mechanism of platelet formation, paving the way to accelerating and enhancing platelet production using stem cells.

The group uncovered their findings by studying the effects of shear stress on megakaryocyte maturation and the formation of preplatelets, platelet-like particles, and megakaryocyte microparticles.

“Until recently, these microparticles were viewed as inconsequential cell debris,” said Terry Papoutsakis, PhD, of the University of Delaware in Newark.

“We now know that they play a significant biological role in platelet formation. The enhanced generation of preplatelets and platelet-like particles under shear stress correlates with physiological observations—in healthy adults, both acute and prolonged exercise leads to elevated platelet counts.”

“Now, these findings can be used to develop better bioreactor technologies for producing platelets, preplatelets, platelet-like particles, and megakaryocyte microparticles for transfusion medicine, using stem cells as starting material.”

Dr Papoutsakis and his colleagues described these findings in Blood.

The researchers discovered that shear stress accelerated DNA synthesis of immature megakaryocytes, and this was dependent upon exposure time and the shear stress level.

Physiological shear stress increased the formation of preplatelets and platelet-like particles up to 10.8-fold. And it increased megakaryocyte microparticle production up to 47-fold. Platelet-like particles generated under shear flow showed improved function.

Experiments also revealed that phosphatidylserine exposure and caspase-3 activation were enhanced by shear stress. But inhibiting caspase-3 reduced the formation of preplatelets, platelet-like particles, and megakaryocyte microparticles.

Finally, the researchers found that coculturing megakaryocyte microparticles with hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells promoted differentiation to mature megakaryocytes that synthesized α- and dense-granules, and formed preplatelets without exogenous thrombopoietin.

The team noted that, unlike platelets themselves, these microparticles can be frozen, which will enable them to be stored and used for platelet production on an as-needed basis.

“Knowing that these microparticles have a biological function opens the door to other applications, including genetic therapies,” Dr Papoutsakis said. “We’re hopeful that our discovery can break the vicious cycle of [immune thrombocytopenia] as well as other conditions that cause reduced platelet count and cause life-threatening bleeding.” ![]()

in the bone marrow

Scientists say they’ve shed new light on the mechanism of platelet formation, paving the way to accelerating and enhancing platelet production using stem cells.

The group uncovered their findings by studying the effects of shear stress on megakaryocyte maturation and the formation of preplatelets, platelet-like particles, and megakaryocyte microparticles.

“Until recently, these microparticles were viewed as inconsequential cell debris,” said Terry Papoutsakis, PhD, of the University of Delaware in Newark.

“We now know that they play a significant biological role in platelet formation. The enhanced generation of preplatelets and platelet-like particles under shear stress correlates with physiological observations—in healthy adults, both acute and prolonged exercise leads to elevated platelet counts.”

“Now, these findings can be used to develop better bioreactor technologies for producing platelets, preplatelets, platelet-like particles, and megakaryocyte microparticles for transfusion medicine, using stem cells as starting material.”

Dr Papoutsakis and his colleagues described these findings in Blood.

The researchers discovered that shear stress accelerated DNA synthesis of immature megakaryocytes, and this was dependent upon exposure time and the shear stress level.

Physiological shear stress increased the formation of preplatelets and platelet-like particles up to 10.8-fold. And it increased megakaryocyte microparticle production up to 47-fold. Platelet-like particles generated under shear flow showed improved function.

Experiments also revealed that phosphatidylserine exposure and caspase-3 activation were enhanced by shear stress. But inhibiting caspase-3 reduced the formation of preplatelets, platelet-like particles, and megakaryocyte microparticles.

Finally, the researchers found that coculturing megakaryocyte microparticles with hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells promoted differentiation to mature megakaryocytes that synthesized α- and dense-granules, and formed preplatelets without exogenous thrombopoietin.

The team noted that, unlike platelets themselves, these microparticles can be frozen, which will enable them to be stored and used for platelet production on an as-needed basis.

“Knowing that these microparticles have a biological function opens the door to other applications, including genetic therapies,” Dr Papoutsakis said. “We’re hopeful that our discovery can break the vicious cycle of [immune thrombocytopenia] as well as other conditions that cause reduced platelet count and cause life-threatening bleeding.” ![]()

Proper transfusion practice prevents CMV

Credit: Vera Kratochvil

New research confirms that transfusing leukoreduced, cytomegalovirus (CMV)-seronegative blood products prevents CMV transmission in very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants.

The study showed that, with this approach, maternal breast milk becomes the primary source of postnatal CMV infection.

“Previously, the risk of CMV infection from blood transfusion of seronegative or leukoreduced transfusions was estimated to be 1% to 3%,” said Cassandra Josephson, MD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

“We showed that, using blood components that are both CMV-seronegative and leukoreduced, we can effectively prevent the transfusion-transmission of CMV. Therefore, we believe that this is the safest approach to reduce the risk of CMV infection when giving transfusions to VLBW infants.”

Dr Josephson and her colleagues described this research in JAMA Pediatrics.

The researchers evaluated 462 mothers and 539 VLBW infants who were admitted to 3 neonatal intensive care units between January 2010 and June 2013.

A majority of mothers had a history of CMV infection prior to delivery (CMV sero-prevalence of 76.2%). The infants were enrolled in the study within 5 days of birth and had not received a blood transfusion at that time.

The infants were tested for congenital infection at birth and again at 5 additional intervals between birth and 90 days, discharge, or death.

Twenty-nine of the infants had CMV infection (cumulative incidence of 6.9% at 12 weeks). Five infants with CMV infection developed severe disease or died.

Although 2061 transfusions were administered to 310 of the infants (57.5%), the blood products were CMV-seronegative and leukoreduced, and none of the CMV infections was linked to transfusion.

Twenty-seven of 28 infections acquired after birth occurred among infants fed CMV-positive breast milk.

Dr Josephson and her colleagues estimate that between 1 in 5 and 1 in 10 VLBW infants who are fed CMV-positive breast milk from mothers with a history of CMV infection will develop postnatal CMV infection.

The American Academy of Pediatrics currently states that the value of routinely feeding breast milk from CMV-seropositive mothers to preterm infants outweighs the risks of clinical disease from CMV.

But the researchers noted that new strategies to prevent breast milk transmission of CMV are needed because freezing and thawing breast milk did not completely prevent transmission in this study.

The team said alternative approaches to prevent breast milk transmission of CMV could include routine CMV-serologic testing of pregnant mothers to enable counseling regarding the risk of infection, closer surveillance of infants with CMV-positive mothers, and pasteurization of breast milk until a corrected gestational age of 34 weeks (as recommended by the Austrian Society of Pediatrics).

In addition, routine screening for postnatal CMV infection may help identify infants who are likely to develop symptomatic disease.

The researchers also said the frequency of CMV infection in this study raises significant concern about the potential consequences of CMV infection among VLBW infants and points to the need for large, long-term follow-up studies of neurological outcomes in infants with postnatal CMV infection. ![]()

Credit: Vera Kratochvil

New research confirms that transfusing leukoreduced, cytomegalovirus (CMV)-seronegative blood products prevents CMV transmission in very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants.

The study showed that, with this approach, maternal breast milk becomes the primary source of postnatal CMV infection.

“Previously, the risk of CMV infection from blood transfusion of seronegative or leukoreduced transfusions was estimated to be 1% to 3%,” said Cassandra Josephson, MD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

“We showed that, using blood components that are both CMV-seronegative and leukoreduced, we can effectively prevent the transfusion-transmission of CMV. Therefore, we believe that this is the safest approach to reduce the risk of CMV infection when giving transfusions to VLBW infants.”

Dr Josephson and her colleagues described this research in JAMA Pediatrics.

The researchers evaluated 462 mothers and 539 VLBW infants who were admitted to 3 neonatal intensive care units between January 2010 and June 2013.

A majority of mothers had a history of CMV infection prior to delivery (CMV sero-prevalence of 76.2%). The infants were enrolled in the study within 5 days of birth and had not received a blood transfusion at that time.

The infants were tested for congenital infection at birth and again at 5 additional intervals between birth and 90 days, discharge, or death.

Twenty-nine of the infants had CMV infection (cumulative incidence of 6.9% at 12 weeks). Five infants with CMV infection developed severe disease or died.

Although 2061 transfusions were administered to 310 of the infants (57.5%), the blood products were CMV-seronegative and leukoreduced, and none of the CMV infections was linked to transfusion.

Twenty-seven of 28 infections acquired after birth occurred among infants fed CMV-positive breast milk.

Dr Josephson and her colleagues estimate that between 1 in 5 and 1 in 10 VLBW infants who are fed CMV-positive breast milk from mothers with a history of CMV infection will develop postnatal CMV infection.

The American Academy of Pediatrics currently states that the value of routinely feeding breast milk from CMV-seropositive mothers to preterm infants outweighs the risks of clinical disease from CMV.

But the researchers noted that new strategies to prevent breast milk transmission of CMV are needed because freezing and thawing breast milk did not completely prevent transmission in this study.

The team said alternative approaches to prevent breast milk transmission of CMV could include routine CMV-serologic testing of pregnant mothers to enable counseling regarding the risk of infection, closer surveillance of infants with CMV-positive mothers, and pasteurization of breast milk until a corrected gestational age of 34 weeks (as recommended by the Austrian Society of Pediatrics).

In addition, routine screening for postnatal CMV infection may help identify infants who are likely to develop symptomatic disease.

The researchers also said the frequency of CMV infection in this study raises significant concern about the potential consequences of CMV infection among VLBW infants and points to the need for large, long-term follow-up studies of neurological outcomes in infants with postnatal CMV infection. ![]()

Credit: Vera Kratochvil

New research confirms that transfusing leukoreduced, cytomegalovirus (CMV)-seronegative blood products prevents CMV transmission in very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants.

The study showed that, with this approach, maternal breast milk becomes the primary source of postnatal CMV infection.

“Previously, the risk of CMV infection from blood transfusion of seronegative or leukoreduced transfusions was estimated to be 1% to 3%,” said Cassandra Josephson, MD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

“We showed that, using blood components that are both CMV-seronegative and leukoreduced, we can effectively prevent the transfusion-transmission of CMV. Therefore, we believe that this is the safest approach to reduce the risk of CMV infection when giving transfusions to VLBW infants.”

Dr Josephson and her colleagues described this research in JAMA Pediatrics.

The researchers evaluated 462 mothers and 539 VLBW infants who were admitted to 3 neonatal intensive care units between January 2010 and June 2013.

A majority of mothers had a history of CMV infection prior to delivery (CMV sero-prevalence of 76.2%). The infants were enrolled in the study within 5 days of birth and had not received a blood transfusion at that time.

The infants were tested for congenital infection at birth and again at 5 additional intervals between birth and 90 days, discharge, or death.

Twenty-nine of the infants had CMV infection (cumulative incidence of 6.9% at 12 weeks). Five infants with CMV infection developed severe disease or died.

Although 2061 transfusions were administered to 310 of the infants (57.5%), the blood products were CMV-seronegative and leukoreduced, and none of the CMV infections was linked to transfusion.

Twenty-seven of 28 infections acquired after birth occurred among infants fed CMV-positive breast milk.

Dr Josephson and her colleagues estimate that between 1 in 5 and 1 in 10 VLBW infants who are fed CMV-positive breast milk from mothers with a history of CMV infection will develop postnatal CMV infection.

The American Academy of Pediatrics currently states that the value of routinely feeding breast milk from CMV-seropositive mothers to preterm infants outweighs the risks of clinical disease from CMV.

But the researchers noted that new strategies to prevent breast milk transmission of CMV are needed because freezing and thawing breast milk did not completely prevent transmission in this study.

The team said alternative approaches to prevent breast milk transmission of CMV could include routine CMV-serologic testing of pregnant mothers to enable counseling regarding the risk of infection, closer surveillance of infants with CMV-positive mothers, and pasteurization of breast milk until a corrected gestational age of 34 weeks (as recommended by the Austrian Society of Pediatrics).

In addition, routine screening for postnatal CMV infection may help identify infants who are likely to develop symptomatic disease.

The researchers also said the frequency of CMV infection in this study raises significant concern about the potential consequences of CMV infection among VLBW infants and points to the need for large, long-term follow-up studies of neurological outcomes in infants with postnatal CMV infection. ![]()

Molecule enables ‘robust’ expansion of cord blood cells

Credit: NHS

Investigators say they have identified a molecule that allows for robust ex vivo expansion of human cord blood (CB) cells.

CB cells expanded with this molecule, known as UM171, were capable of human hematopoietic reconstitution in NSG mice, an effect that lasted more than 6 months.

The researchers believe UM171 acts by enhancing the long-term-hematopoietic stem cell (LT-HSC) self-renewal machinery independently of AhR suppression.

Guy Sauvageau, MD, PhD, of the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada, and his colleagues identified UM171 and described the discovery in Science.

The team first screened a library of 5280 low-molecular-weight compounds looking for those with the ability to expand human CD34+CD45RA- mobilized peripheral blood cells, which are enriched in LT-HSCs.

They got 7 hits, and only 2 of these—UM729 and UM118428—did not suppress the AhR pathway. The researchers selected UM729 for further characterization and optimization because it demonstrated superior activity in expanding CD34+CD45RA- cells.

The investigators analyzed more than 300 newly synthesized analogs of UM729 and identified one that was 10 to 20 times more potent than UM729. That compound was UM171.

UM171 could expand CD34+CD45RA- cells at concentrations of 17 nM to 19 nM. The highest expansion of multipotent progenitors and long-term culture-initiating cells occurred on day 12.

The effect of UM171 required its constant presence in the media, and the compound lacked direct mitogenic activity. UM171 did not affect the division rate of phenotypically primitive cell populations.

The researchers compared UM171 to SR1 (a compound known to promote self-renewal of HSCs) in fed-batch culture. They found that frequencies of CD34+ CB cells were similar in cultures containing SR1 and those containing UM171. But CD34+CD45RA- cells were more abundant with UM171 (P<0.005).

The team then evaluated LT-HSC populations. Twenty weeks after CD34+ CB cells were transplanted into mice, LT-HSC frequencies were similar in mice that received control and SR1-expanded cells. But LT-HSC frequencies were 13-fold higher in the mice that received UM171-expanded cells.

Next, the investigators assessed human hematopoietic reconstitution in NSG mice transplanted with fresh or expanded cells. They observed 2 patterns of reconstitution. One was from predominantly lymphomyeloid LT-HSCs that occurred with high cell doses in most conditions.

And the other was from LT-HSCs that display a lymphoid-deficient differentiation phenotype mostly observed with UM171 treatment, with or without SR1. However, UM171 did not negatively affect B lymphopoiesis or the frequency or number of lymphomyeloid LT-HSCs.

The impact of UM171 on LT-HSCs was preserved at 30 weeks post-transplant. And myeloid cell output was slightly augmented, a phenomenon that has been observed with normal, unexpanded cells.

The researchers also transplanted UM171-treated LT-HSC populations into secondary recipients. And they found the cells were still competent, but they had no advantage over unmanipulated CD34+ cells.

A clinical study of UM171 and a new type of bioreactor developed for stem cell culture is set to begin this December. The cells will be expanded at Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital, and grafts will be distributed to patients in Montreal, Quebec City, and Vancouver. The investigators expect tangible results will be available in December 2015. ![]()

Credit: NHS

Investigators say they have identified a molecule that allows for robust ex vivo expansion of human cord blood (CB) cells.

CB cells expanded with this molecule, known as UM171, were capable of human hematopoietic reconstitution in NSG mice, an effect that lasted more than 6 months.

The researchers believe UM171 acts by enhancing the long-term-hematopoietic stem cell (LT-HSC) self-renewal machinery independently of AhR suppression.

Guy Sauvageau, MD, PhD, of the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada, and his colleagues identified UM171 and described the discovery in Science.

The team first screened a library of 5280 low-molecular-weight compounds looking for those with the ability to expand human CD34+CD45RA- mobilized peripheral blood cells, which are enriched in LT-HSCs.

They got 7 hits, and only 2 of these—UM729 and UM118428—did not suppress the AhR pathway. The researchers selected UM729 for further characterization and optimization because it demonstrated superior activity in expanding CD34+CD45RA- cells.

The investigators analyzed more than 300 newly synthesized analogs of UM729 and identified one that was 10 to 20 times more potent than UM729. That compound was UM171.

UM171 could expand CD34+CD45RA- cells at concentrations of 17 nM to 19 nM. The highest expansion of multipotent progenitors and long-term culture-initiating cells occurred on day 12.

The effect of UM171 required its constant presence in the media, and the compound lacked direct mitogenic activity. UM171 did not affect the division rate of phenotypically primitive cell populations.

The researchers compared UM171 to SR1 (a compound known to promote self-renewal of HSCs) in fed-batch culture. They found that frequencies of CD34+ CB cells were similar in cultures containing SR1 and those containing UM171. But CD34+CD45RA- cells were more abundant with UM171 (P<0.005).

The team then evaluated LT-HSC populations. Twenty weeks after CD34+ CB cells were transplanted into mice, LT-HSC frequencies were similar in mice that received control and SR1-expanded cells. But LT-HSC frequencies were 13-fold higher in the mice that received UM171-expanded cells.

Next, the investigators assessed human hematopoietic reconstitution in NSG mice transplanted with fresh or expanded cells. They observed 2 patterns of reconstitution. One was from predominantly lymphomyeloid LT-HSCs that occurred with high cell doses in most conditions.

And the other was from LT-HSCs that display a lymphoid-deficient differentiation phenotype mostly observed with UM171 treatment, with or without SR1. However, UM171 did not negatively affect B lymphopoiesis or the frequency or number of lymphomyeloid LT-HSCs.

The impact of UM171 on LT-HSCs was preserved at 30 weeks post-transplant. And myeloid cell output was slightly augmented, a phenomenon that has been observed with normal, unexpanded cells.

The researchers also transplanted UM171-treated LT-HSC populations into secondary recipients. And they found the cells were still competent, but they had no advantage over unmanipulated CD34+ cells.

A clinical study of UM171 and a new type of bioreactor developed for stem cell culture is set to begin this December. The cells will be expanded at Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital, and grafts will be distributed to patients in Montreal, Quebec City, and Vancouver. The investigators expect tangible results will be available in December 2015. ![]()

Credit: NHS

Investigators say they have identified a molecule that allows for robust ex vivo expansion of human cord blood (CB) cells.

CB cells expanded with this molecule, known as UM171, were capable of human hematopoietic reconstitution in NSG mice, an effect that lasted more than 6 months.

The researchers believe UM171 acts by enhancing the long-term-hematopoietic stem cell (LT-HSC) self-renewal machinery independently of AhR suppression.

Guy Sauvageau, MD, PhD, of the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada, and his colleagues identified UM171 and described the discovery in Science.

The team first screened a library of 5280 low-molecular-weight compounds looking for those with the ability to expand human CD34+CD45RA- mobilized peripheral blood cells, which are enriched in LT-HSCs.

They got 7 hits, and only 2 of these—UM729 and UM118428—did not suppress the AhR pathway. The researchers selected UM729 for further characterization and optimization because it demonstrated superior activity in expanding CD34+CD45RA- cells.

The investigators analyzed more than 300 newly synthesized analogs of UM729 and identified one that was 10 to 20 times more potent than UM729. That compound was UM171.

UM171 could expand CD34+CD45RA- cells at concentrations of 17 nM to 19 nM. The highest expansion of multipotent progenitors and long-term culture-initiating cells occurred on day 12.

The effect of UM171 required its constant presence in the media, and the compound lacked direct mitogenic activity. UM171 did not affect the division rate of phenotypically primitive cell populations.

The researchers compared UM171 to SR1 (a compound known to promote self-renewal of HSCs) in fed-batch culture. They found that frequencies of CD34+ CB cells were similar in cultures containing SR1 and those containing UM171. But CD34+CD45RA- cells were more abundant with UM171 (P<0.005).

The team then evaluated LT-HSC populations. Twenty weeks after CD34+ CB cells were transplanted into mice, LT-HSC frequencies were similar in mice that received control and SR1-expanded cells. But LT-HSC frequencies were 13-fold higher in the mice that received UM171-expanded cells.

Next, the investigators assessed human hematopoietic reconstitution in NSG mice transplanted with fresh or expanded cells. They observed 2 patterns of reconstitution. One was from predominantly lymphomyeloid LT-HSCs that occurred with high cell doses in most conditions.

And the other was from LT-HSCs that display a lymphoid-deficient differentiation phenotype mostly observed with UM171 treatment, with or without SR1. However, UM171 did not negatively affect B lymphopoiesis or the frequency or number of lymphomyeloid LT-HSCs.

The impact of UM171 on LT-HSCs was preserved at 30 weeks post-transplant. And myeloid cell output was slightly augmented, a phenomenon that has been observed with normal, unexpanded cells.

The researchers also transplanted UM171-treated LT-HSC populations into secondary recipients. And they found the cells were still competent, but they had no advantage over unmanipulated CD34+ cells.

A clinical study of UM171 and a new type of bioreactor developed for stem cell culture is set to begin this December. The cells will be expanded at Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital, and grafts will be distributed to patients in Montreal, Quebec City, and Vancouver. The investigators expect tangible results will be available in December 2015. ![]()

Hemostats may decrease costs, use of resources

Credit: Piotr Bodzek

HOUSTON—A family of hemostatic products can decrease the need for blood transfusions, reduce hospital stays, and cut the cost of care for certain surgical patients, a retrospective study suggests.

Researchers compared the SURGICEL family of topical, absorbable hemostats—which are based on oxidized regenerated cellulose—to other adjunctive hemostats—flowables, gelatin, and thrombin—in patients undergoing a range of surgical procedures.

The team presented their findings in a poster at the Society for the Advancement of Blood Management Annual Meeting. The study was sponsored by Ethicon, makers of the SURGICEL products.

The goal of this research was to compare the healthcare resource utilization, costs, and outcomes associated with SURGICEL products—SURGICEL® ORIGINAL, SURGICEL® NU-KNIT®, SURGICEL® FIBRILLAR™, and SURGICEL® SNOW™—to those associated with other adjunctive hemostats.

The researchers analyzed data from adult patients (18 years and older) from the Premier Research Database who were discharged from the hospital between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2012.

Patients had undergone cholecystectomy (n=3045), cardiovascular surgery (n=11,359), hysterectomy (n=4674), or carotid endarterectomy (5445).

The researchers found that fewer units of hemostat were used per discharge among patients who received SURGICEL products than among those who received other hemostats, regardless of the type of surgery.

Hemostat use was 18% lower for cholecystectomy patients (P<0.0001), 28% lower for cardiovascular patients (P<0.0001), 16% lower for hysterectomy patients (P<0.05), and 41% for carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001).

SURGICEL products were also associated with a reduction in blood transfusions for some patients. Transfusions were reduced by 5% among hysterectomy patients (not significant), 18% in cholecystectomy patients (P<0.05), and 32% for carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001).

The mean length of hospital stay and the mean length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) were both lower for certain patients who received SURGICEL products.

Hospital stays were 12% lower in cholecystectomy patients (P<0.05) and 8% lower in carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001). And ICU stays were 3% lower in cholecystectomy patients (not significant) and 8% lower in carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.05).

ICU costs were not significantly lower for patients who received SURGICEL products. However, the costs of hemostats and all-cause costs were lower with SURGICEL products than with other hemostats.

The cost of hemostats was 59% lower for in cholecystectomy patients (P<0.0001), 33% lower in cardiovascular patients (P<0.0001), 57% lower in hysterectomy patients (P<0.0001), and 49% lower in carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001).

The all-cause costs per discharge were 1% lower for hysterectomy patients (P<0.05), 6% lower for carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001), and 14% lower for cholecystectomy patients (P<0.0001).

Cost savings ranged from $71 to $155 per procedure.

“This study adds to the growing body of evidence that suggests the SURGICEL family of topical, absorbable hemostats has the potential to reduce burdens associated with bleeding and bleeding-related complications, which translates into cost and resource-use savings for healthcare providers,” said study investigator Jerome Riebman, MD, director of medical affairs at Ethicon.

Dr Riebman and his colleagues did note that this study was subject to limitations. For example, not all of the factors influencing the physicians’ choice of treatment were available in the dataset.

Furthermore, it’s not clear whether the hospitals studied are representative of all US hospitals. And coding errors or omitted procedure/product codes could have led to patient misclassification and potential bias in the results. ![]()

Credit: Piotr Bodzek

HOUSTON—A family of hemostatic products can decrease the need for blood transfusions, reduce hospital stays, and cut the cost of care for certain surgical patients, a retrospective study suggests.

Researchers compared the SURGICEL family of topical, absorbable hemostats—which are based on oxidized regenerated cellulose—to other adjunctive hemostats—flowables, gelatin, and thrombin—in patients undergoing a range of surgical procedures.

The team presented their findings in a poster at the Society for the Advancement of Blood Management Annual Meeting. The study was sponsored by Ethicon, makers of the SURGICEL products.

The goal of this research was to compare the healthcare resource utilization, costs, and outcomes associated with SURGICEL products—SURGICEL® ORIGINAL, SURGICEL® NU-KNIT®, SURGICEL® FIBRILLAR™, and SURGICEL® SNOW™—to those associated with other adjunctive hemostats.

The researchers analyzed data from adult patients (18 years and older) from the Premier Research Database who were discharged from the hospital between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2012.

Patients had undergone cholecystectomy (n=3045), cardiovascular surgery (n=11,359), hysterectomy (n=4674), or carotid endarterectomy (5445).

The researchers found that fewer units of hemostat were used per discharge among patients who received SURGICEL products than among those who received other hemostats, regardless of the type of surgery.

Hemostat use was 18% lower for cholecystectomy patients (P<0.0001), 28% lower for cardiovascular patients (P<0.0001), 16% lower for hysterectomy patients (P<0.05), and 41% for carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001).

SURGICEL products were also associated with a reduction in blood transfusions for some patients. Transfusions were reduced by 5% among hysterectomy patients (not significant), 18% in cholecystectomy patients (P<0.05), and 32% for carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001).

The mean length of hospital stay and the mean length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) were both lower for certain patients who received SURGICEL products.

Hospital stays were 12% lower in cholecystectomy patients (P<0.05) and 8% lower in carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001). And ICU stays were 3% lower in cholecystectomy patients (not significant) and 8% lower in carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.05).

ICU costs were not significantly lower for patients who received SURGICEL products. However, the costs of hemostats and all-cause costs were lower with SURGICEL products than with other hemostats.

The cost of hemostats was 59% lower for in cholecystectomy patients (P<0.0001), 33% lower in cardiovascular patients (P<0.0001), 57% lower in hysterectomy patients (P<0.0001), and 49% lower in carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001).

The all-cause costs per discharge were 1% lower for hysterectomy patients (P<0.05), 6% lower for carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001), and 14% lower for cholecystectomy patients (P<0.0001).

Cost savings ranged from $71 to $155 per procedure.

“This study adds to the growing body of evidence that suggests the SURGICEL family of topical, absorbable hemostats has the potential to reduce burdens associated with bleeding and bleeding-related complications, which translates into cost and resource-use savings for healthcare providers,” said study investigator Jerome Riebman, MD, director of medical affairs at Ethicon.

Dr Riebman and his colleagues did note that this study was subject to limitations. For example, not all of the factors influencing the physicians’ choice of treatment were available in the dataset.

Furthermore, it’s not clear whether the hospitals studied are representative of all US hospitals. And coding errors or omitted procedure/product codes could have led to patient misclassification and potential bias in the results. ![]()

Credit: Piotr Bodzek

HOUSTON—A family of hemostatic products can decrease the need for blood transfusions, reduce hospital stays, and cut the cost of care for certain surgical patients, a retrospective study suggests.

Researchers compared the SURGICEL family of topical, absorbable hemostats—which are based on oxidized regenerated cellulose—to other adjunctive hemostats—flowables, gelatin, and thrombin—in patients undergoing a range of surgical procedures.

The team presented their findings in a poster at the Society for the Advancement of Blood Management Annual Meeting. The study was sponsored by Ethicon, makers of the SURGICEL products.

The goal of this research was to compare the healthcare resource utilization, costs, and outcomes associated with SURGICEL products—SURGICEL® ORIGINAL, SURGICEL® NU-KNIT®, SURGICEL® FIBRILLAR™, and SURGICEL® SNOW™—to those associated with other adjunctive hemostats.

The researchers analyzed data from adult patients (18 years and older) from the Premier Research Database who were discharged from the hospital between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2012.

Patients had undergone cholecystectomy (n=3045), cardiovascular surgery (n=11,359), hysterectomy (n=4674), or carotid endarterectomy (5445).

The researchers found that fewer units of hemostat were used per discharge among patients who received SURGICEL products than among those who received other hemostats, regardless of the type of surgery.

Hemostat use was 18% lower for cholecystectomy patients (P<0.0001), 28% lower for cardiovascular patients (P<0.0001), 16% lower for hysterectomy patients (P<0.05), and 41% for carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001).

SURGICEL products were also associated with a reduction in blood transfusions for some patients. Transfusions were reduced by 5% among hysterectomy patients (not significant), 18% in cholecystectomy patients (P<0.05), and 32% for carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001).

The mean length of hospital stay and the mean length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) were both lower for certain patients who received SURGICEL products.

Hospital stays were 12% lower in cholecystectomy patients (P<0.05) and 8% lower in carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001). And ICU stays were 3% lower in cholecystectomy patients (not significant) and 8% lower in carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.05).

ICU costs were not significantly lower for patients who received SURGICEL products. However, the costs of hemostats and all-cause costs were lower with SURGICEL products than with other hemostats.

The cost of hemostats was 59% lower for in cholecystectomy patients (P<0.0001), 33% lower in cardiovascular patients (P<0.0001), 57% lower in hysterectomy patients (P<0.0001), and 49% lower in carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001).

The all-cause costs per discharge were 1% lower for hysterectomy patients (P<0.05), 6% lower for carotid endarterectomy patients (P<0.0001), and 14% lower for cholecystectomy patients (P<0.0001).

Cost savings ranged from $71 to $155 per procedure.

“This study adds to the growing body of evidence that suggests the SURGICEL family of topical, absorbable hemostats has the potential to reduce burdens associated with bleeding and bleeding-related complications, which translates into cost and resource-use savings for healthcare providers,” said study investigator Jerome Riebman, MD, director of medical affairs at Ethicon.

Dr Riebman and his colleagues did note that this study was subject to limitations. For example, not all of the factors influencing the physicians’ choice of treatment were available in the dataset.

Furthermore, it’s not clear whether the hospitals studied are representative of all US hospitals. And coding errors or omitted procedure/product codes could have led to patient misclassification and potential bias in the results. ![]()

WHO supports study of blood transfusions for Ebola

Credit: Elise Amendola

Experts from the World Health Organization (WHO) have identified several interventions that should be the focus of clinical evaluation for treating and preventing Ebola.

Transfusions of blood products from Ebola survivors topped this list.

Of course, such blood preparations, like the other interventions the WHO discussed, have not been approved to treat or prevent Ebola.

However, they could be available before the year is out, according to WHO estimates. The organization is exploring options to conduct clinical trials of blood products in Ebola patients.

Previous studies have suggested blood transfusions from Ebola survivors might prevent or treat Ebola virus infection. However, it is unclear whether antibodies in the plasma of survivors are sufficient to treat or prevent the disease.

Safety is also a concern, although the WHO said transfusions should be safe if they are provided by well-managed blood banks. Still, there is a risk of transmitting blood-borne pathogens and a theoretical concern about antibody-dependent enhancement of Ebola virus infection.

“[T]here was a lot of discussion and emphasis on blood, on blood transfusion, whole-blood transfusion, as well as on plasma that can be purified from convalescent serum,” said Marie-Paule Kieny, Assistant Director-General at the WHO.

“There was consensus that this has a good chance to work and that, also, this is something that can be produced now from the affected countries themselves.”

The experts also agreed that the international community needs to help affected countries create the necessary infrastructure to draw blood safely and prepare the blood products safely.

Aside from blood transfusions, the WHO experts mentioned 2 potential Ebola vaccines that should be a priority. Safety studies of these vaccines—based on vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-EBO) and chimpanzee adenovirus (ChAd-EBO)—are beginning in the US and are slated to begin in Africa and Europe in mid-September.

If proven safe, a vaccine could be available in November 2014 for priority use in healthcare workers.

The WHO experts also discussed the availability and evidence supporting the use of novel therapeutic drugs, including monoclonal antibodies, RNA-based drugs, and small antiviral molecules. They considered the potential use of existing drugs approved for other diseases and conditions as well.

Of the novel products discussed, some have shown great promise in monkey models. Others have been used in a few Ebola patients and appear safe, but the numbers are too small to permit any definitive conclusions about efficacy.

Existing supplies of all experimental medicines are limited, the WHO said. While many efforts are underway to accelerate production, supplies will not be sufficient for several months to come. The prospects of having augmented supplies of vaccines rapidly look slightly better.

The WHO also cautioned that the investigation of the aforementioned interventions should not detract attention from measures to prevent Ebola from spreading. ![]()

Credit: Elise Amendola

Experts from the World Health Organization (WHO) have identified several interventions that should be the focus of clinical evaluation for treating and preventing Ebola.

Transfusions of blood products from Ebola survivors topped this list.

Of course, such blood preparations, like the other interventions the WHO discussed, have not been approved to treat or prevent Ebola.

However, they could be available before the year is out, according to WHO estimates. The organization is exploring options to conduct clinical trials of blood products in Ebola patients.

Previous studies have suggested blood transfusions from Ebola survivors might prevent or treat Ebola virus infection. However, it is unclear whether antibodies in the plasma of survivors are sufficient to treat or prevent the disease.

Safety is also a concern, although the WHO said transfusions should be safe if they are provided by well-managed blood banks. Still, there is a risk of transmitting blood-borne pathogens and a theoretical concern about antibody-dependent enhancement of Ebola virus infection.

“[T]here was a lot of discussion and emphasis on blood, on blood transfusion, whole-blood transfusion, as well as on plasma that can be purified from convalescent serum,” said Marie-Paule Kieny, Assistant Director-General at the WHO.

“There was consensus that this has a good chance to work and that, also, this is something that can be produced now from the affected countries themselves.”

The experts also agreed that the international community needs to help affected countries create the necessary infrastructure to draw blood safely and prepare the blood products safely.

Aside from blood transfusions, the WHO experts mentioned 2 potential Ebola vaccines that should be a priority. Safety studies of these vaccines—based on vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-EBO) and chimpanzee adenovirus (ChAd-EBO)—are beginning in the US and are slated to begin in Africa and Europe in mid-September.

If proven safe, a vaccine could be available in November 2014 for priority use in healthcare workers.

The WHO experts also discussed the availability and evidence supporting the use of novel therapeutic drugs, including monoclonal antibodies, RNA-based drugs, and small antiviral molecules. They considered the potential use of existing drugs approved for other diseases and conditions as well.

Of the novel products discussed, some have shown great promise in monkey models. Others have been used in a few Ebola patients and appear safe, but the numbers are too small to permit any definitive conclusions about efficacy.

Existing supplies of all experimental medicines are limited, the WHO said. While many efforts are underway to accelerate production, supplies will not be sufficient for several months to come. The prospects of having augmented supplies of vaccines rapidly look slightly better.

The WHO also cautioned that the investigation of the aforementioned interventions should not detract attention from measures to prevent Ebola from spreading. ![]()

Credit: Elise Amendola

Experts from the World Health Organization (WHO) have identified several interventions that should be the focus of clinical evaluation for treating and preventing Ebola.

Transfusions of blood products from Ebola survivors topped this list.

Of course, such blood preparations, like the other interventions the WHO discussed, have not been approved to treat or prevent Ebola.

However, they could be available before the year is out, according to WHO estimates. The organization is exploring options to conduct clinical trials of blood products in Ebola patients.

Previous studies have suggested blood transfusions from Ebola survivors might prevent or treat Ebola virus infection. However, it is unclear whether antibodies in the plasma of survivors are sufficient to treat or prevent the disease.

Safety is also a concern, although the WHO said transfusions should be safe if they are provided by well-managed blood banks. Still, there is a risk of transmitting blood-borne pathogens and a theoretical concern about antibody-dependent enhancement of Ebola virus infection.

“[T]here was a lot of discussion and emphasis on blood, on blood transfusion, whole-blood transfusion, as well as on plasma that can be purified from convalescent serum,” said Marie-Paule Kieny, Assistant Director-General at the WHO.

“There was consensus that this has a good chance to work and that, also, this is something that can be produced now from the affected countries themselves.”

The experts also agreed that the international community needs to help affected countries create the necessary infrastructure to draw blood safely and prepare the blood products safely.

Aside from blood transfusions, the WHO experts mentioned 2 potential Ebola vaccines that should be a priority. Safety studies of these vaccines—based on vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-EBO) and chimpanzee adenovirus (ChAd-EBO)—are beginning in the US and are slated to begin in Africa and Europe in mid-September.

If proven safe, a vaccine could be available in November 2014 for priority use in healthcare workers.

The WHO experts also discussed the availability and evidence supporting the use of novel therapeutic drugs, including monoclonal antibodies, RNA-based drugs, and small antiviral molecules. They considered the potential use of existing drugs approved for other diseases and conditions as well.

Of the novel products discussed, some have shown great promise in monkey models. Others have been used in a few Ebola patients and appear safe, but the numbers are too small to permit any definitive conclusions about efficacy.

Existing supplies of all experimental medicines are limited, the WHO said. While many efforts are underway to accelerate production, supplies will not be sufficient for several months to come. The prospects of having augmented supplies of vaccines rapidly look slightly better.

The WHO also cautioned that the investigation of the aforementioned interventions should not detract attention from measures to prevent Ebola from spreading.

Banked blood grows stiffer with age, study shows

Credit: Daniel Gay

The longer blood is stored, the less it is able to carry oxygen into the tiny microcapillaries of the body, according to a study published in Scientific Reports.

Using advanced optical techniques, researchers measured the stiffness of the membrane surrounding red blood cells.

They found that, even though the cells retain their shape and hemoglobin content, the membranes get stiffer over time, which steadily decreases the cells’ functionality.

“Our results show some surprising facts: Even though the blood looks good on the surface, its functionality is degrading steadily with time,” said study author Gabriel Popescu, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Dr Popescu and his colleagues wanted to measure changes in red blood cells over time to help determine what effect older blood could have on a patient.

They used an optical technique called spatial light interference microscopy (SLIM), which was developed in Dr Popescu’s lab in 2011. It uses light to noninvasively measure cell mass and topology with nanoscale accuracy. Through software and hardware advances, the SLIM system today acquires images almost 100 times faster than it did 3 years ago.

The researchers took time-lapse images of red blood cells, measuring and charting their properties. In particular, the team was able to measure nanometer-scale motions of the cell membrane, which are indicative of the cell’s stiffness and function. The fainter the membrane motion, the less functional the cell.

The measurements revealed that a lot of characteristics stay the same over time. The cells retain their shape, mass, and hemoglobin content, for example.

However, the membranes become stiffer and less elastic as time passes. This is important because the cells need to be flexible enough to travel through tiny capillaries and permeable enough for oxygen to pass through.

“In microcirculation, such as that in the brain, cells need to squeeze though very narrow capillaries to carry oxygen,” said study author Basanta Bhaduri, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

“If they are not deformable enough, the oxygen transport is impeded to that particular organ, and major clinical problems may arise. This is the reason why new red blood cells are produced continuously by the bone marrow, such that no cells older than 100 days or so exist in our circulation.”

The researchers hope the SLIM imaging method will be used clinically to monitor stored blood before it is given to patients, since conventional white-light microscopes can be easily adapted for SLIM with a few extra components.

“These results can have a wide variety of clinical applications,” said author Krishna Tangella, MD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

“Functional data from red blood cells would help physicians determine when to give red cell transfusions for patients with anemia. This study may help better utilization of red cell transfusions, which will not only decrease healthcare costs but also increase the quality of care.”

Credit: Daniel Gay

The longer blood is stored, the less it is able to carry oxygen into the tiny microcapillaries of the body, according to a study published in Scientific Reports.

Using advanced optical techniques, researchers measured the stiffness of the membrane surrounding red blood cells.

They found that, even though the cells retain their shape and hemoglobin content, the membranes get stiffer over time, which steadily decreases the cells’ functionality.

“Our results show some surprising facts: Even though the blood looks good on the surface, its functionality is degrading steadily with time,” said study author Gabriel Popescu, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Dr Popescu and his colleagues wanted to measure changes in red blood cells over time to help determine what effect older blood could have on a patient.

They used an optical technique called spatial light interference microscopy (SLIM), which was developed in Dr Popescu’s lab in 2011. It uses light to noninvasively measure cell mass and topology with nanoscale accuracy. Through software and hardware advances, the SLIM system today acquires images almost 100 times faster than it did 3 years ago.

The researchers took time-lapse images of red blood cells, measuring and charting their properties. In particular, the team was able to measure nanometer-scale motions of the cell membrane, which are indicative of the cell’s stiffness and function. The fainter the membrane motion, the less functional the cell.

The measurements revealed that a lot of characteristics stay the same over time. The cells retain their shape, mass, and hemoglobin content, for example.

However, the membranes become stiffer and less elastic as time passes. This is important because the cells need to be flexible enough to travel through tiny capillaries and permeable enough for oxygen to pass through.

“In microcirculation, such as that in the brain, cells need to squeeze though very narrow capillaries to carry oxygen,” said study author Basanta Bhaduri, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

“If they are not deformable enough, the oxygen transport is impeded to that particular organ, and major clinical problems may arise. This is the reason why new red blood cells are produced continuously by the bone marrow, such that no cells older than 100 days or so exist in our circulation.”

The researchers hope the SLIM imaging method will be used clinically to monitor stored blood before it is given to patients, since conventional white-light microscopes can be easily adapted for SLIM with a few extra components.

“These results can have a wide variety of clinical applications,” said author Krishna Tangella, MD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

“Functional data from red blood cells would help physicians determine when to give red cell transfusions for patients with anemia. This study may help better utilization of red cell transfusions, which will not only decrease healthcare costs but also increase the quality of care.”

Credit: Daniel Gay

The longer blood is stored, the less it is able to carry oxygen into the tiny microcapillaries of the body, according to a study published in Scientific Reports.

Using advanced optical techniques, researchers measured the stiffness of the membrane surrounding red blood cells.

They found that, even though the cells retain their shape and hemoglobin content, the membranes get stiffer over time, which steadily decreases the cells’ functionality.

“Our results show some surprising facts: Even though the blood looks good on the surface, its functionality is degrading steadily with time,” said study author Gabriel Popescu, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Dr Popescu and his colleagues wanted to measure changes in red blood cells over time to help determine what effect older blood could have on a patient.

They used an optical technique called spatial light interference microscopy (SLIM), which was developed in Dr Popescu’s lab in 2011. It uses light to noninvasively measure cell mass and topology with nanoscale accuracy. Through software and hardware advances, the SLIM system today acquires images almost 100 times faster than it did 3 years ago.

The researchers took time-lapse images of red blood cells, measuring and charting their properties. In particular, the team was able to measure nanometer-scale motions of the cell membrane, which are indicative of the cell’s stiffness and function. The fainter the membrane motion, the less functional the cell.

The measurements revealed that a lot of characteristics stay the same over time. The cells retain their shape, mass, and hemoglobin content, for example.

However, the membranes become stiffer and less elastic as time passes. This is important because the cells need to be flexible enough to travel through tiny capillaries and permeable enough for oxygen to pass through.

“In microcirculation, such as that in the brain, cells need to squeeze though very narrow capillaries to carry oxygen,” said study author Basanta Bhaduri, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

“If they are not deformable enough, the oxygen transport is impeded to that particular organ, and major clinical problems may arise. This is the reason why new red blood cells are produced continuously by the bone marrow, such that no cells older than 100 days or so exist in our circulation.”

The researchers hope the SLIM imaging method will be used clinically to monitor stored blood before it is given to patients, since conventional white-light microscopes can be easily adapted for SLIM with a few extra components.

“These results can have a wide variety of clinical applications,” said author Krishna Tangella, MD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

“Functional data from red blood cells would help physicians determine when to give red cell transfusions for patients with anemia. This study may help better utilization of red cell transfusions, which will not only decrease healthcare costs but also increase the quality of care.”

Overcoming an obstacle to RBC development

Researchers have discovered a natural barrier to hematopoiesis and a way to circumvent it, according to a paper published in Blood.

The group found that components of the exosome complex—exosc8 and exosc9—suppress red blood cell (RBC) maturation.

“From a fundamental perspective, this is very important because this mechanism counteracts the development of precursor cells into red blood cells, thereby establishing a balance between developed cells and the progenitor population,” said study author Emery Bresnick, PhD, of the UW School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison, Wisconsin.

“In the context of translation, if you want to maximize the output of end-stage red blood cells, which we’re not able to do at this time, our study provides a rational approach involving lowering the levels of these subunits.”

Specifically, the researchers found that GATA-1 and Foxo3 can repress the exosome components, thereby allowing for RBC maturation.

The barrier explained

Dr Bresnick and his colleagues noted that the primary obstacle in converting hematopoietic stem cells into RBCs involves late-stage maturation.

“The problem isn’t simply getting erythroid precursors produced by the bucket, but understanding how these cells systematically lose their nuclei and organelles to become a red blood cell, the final product,” Dr Bresnick said.

“This is the bottleneck, even in the stem cell world of embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. We know little about how the cell orchestrates the intricate processes that constitute late-stage maturation.”

At the end of RBC development, the erythroid precursor must eject its own genetic material via enucleation. Although it’s clear why enucleation is important (making the cell more flexible and allowing it to carry more oxygen), exactly how the cell does it has been unclear.

Besides ejecting the nucleus, the cell must be cleared of other organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. This process (autophagy) is linked to a pair of transcription factors—GATA1 and Foxo3—that control gene expression important in RBC development.

Because they knew GATA1 and Foxo3 promote autophagy, Dr Bresnick and his colleagues wondered if the proteins these transcription factors repress play an important role in cell maturation.

This led them to identify exosc8 and exosc9, two units of the exosome that ultimately established the development barrier.