User login

In CLL, specific mutation is key to ibrutinib resistance

Acquired BTKC481S and PLCG2 mutations led to ibrutinib resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), investigators reported online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

These mutations preceded 85% of clinical relapses, appearing a median of 9.3 months beforehand, Jennifer A. Woyach, MD, and her associates from the Ohio State University, Columbus, concluded from a retrospective study of 308 patients. In a separate prospective study of 112 patients, acquired BTKC481S mutation and clonal expansion preceded all eight cases of relapse, they said. “Relapse of CLL after ibrutinib is an issue of increasing clinical significance,” they concluded. “We show that mutations in Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) and PLCG2 appear early and have the potential to be used as a biomarker for future relapse, suggesting an opportunity for intervention.”

Ibrutinib has transformed the CLL treatment landscape, but patients face poor outcomes if they relapse with Richter transformation or develop progressive disease. Past work has linked ibrutinib resistance to acquired mutations in BTK at the binding site of ibrutinib and in PLCG2 located just downstream. But the scope of ibrutinib resistance in CLL and key mutational players were unknown (J Clin Oncol. 2017. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.2282).

To fill that gap, the researchers retrospectively analyzed data from four sequential ibrutinib CLL trials at the Ohio State University. The separate prospective analysis involved analyzing the entire BTK and PLCG2 coding regions every 3 months.

In the retrospective study, patients had received a median of 3 and up to 16 prior therapies. Given the median follow-up period of 3.4 years, about 19% of patients experienced clinical relapse within 4 years of starting ibrutinib, the researchers estimated (95% confidence interval, 14%-24%). Deep sequencing by Ion Torrent (Life Technologies) identified mutations in BTKC481S and/or PLCG2, in 40 of 47 (85%) relapses. In 31 cases, BTKC481S was the sole mutation. Mutational burdens varied among patients, but generally correlated with CLL progression in peripheral blood versus primarily nodal relapse.

At baseline, 172 (58%) of retrospective study participants had complex cytogenetics, 52% had del(13q), 40% had del(17p), and 21% had MYC abnormality. Median age was 65 years (range, 26-91 years) and 70% of patients were female. Multivariable analyses linked transformation to complex karyotype (hazard ratio, 5.0; 95% CI, 1.5-16.5) and MYC abnormality (HR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.0-4.7), and linked progressive CLL to age younger than 65 years, complex karyotype, and del(17)(p13.1).

Richter transformation usually occurred within 2 years of starting ibrutinib and had a cumulative 4-year incidence of 10%, the investigators also reported. Patients survived a median of only 3.9 months after stopping ibrutinib because of transformation. The cumulative rate of progressive CLL was higher (19.1%), but early progression was rare, and patients who stopped ibrutinib because of progression survived longer (median, 22.7 months).

In the prospective study, all eight patients with BTKC481S who had not yet clinically relapsed nonetheless had increasing frequency of this mutation over time, the investigators reported. Together, the findings confirm BTK and PLCG2 mutations as the key players in CLL resistance to ibrutinib, they stated. Perhaps most importantly, they reveal “a prolonged period of asymptomatic clonal expression” in CLL that precedes clinical relapse and provides a window of opportunity to target these cells with novel therapies in clinical trials, they wrote.

Given that ibrutinib was approved for use in relapsed CLL only 2 years ago, “We are likely just starting to see the first emergence of relapse in the community setting,” the researchers concluded. “Enhanced knowledge of both the molecular and clinical mechanisms of relapse may allow for strategic alterations in monitoring and management that could change the natural history of ibrutinib resistance.”

Funding sources included the D. Warren Brown Foundation, Mr. and Mrs. Michael Thomas, the Four Winds Foundation, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Pelotonia, and the National Cancer Institute. Pharmacyclics also provided partial support. Dr. Woyach disclosed ties to Janssen, Acerta Pharma, Karyopharm Therapeutics, and MorphoSys, and a provisional patent related to C481S detection.

Acquired BTKC481S and PLCG2 mutations led to ibrutinib resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), investigators reported online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

These mutations preceded 85% of clinical relapses, appearing a median of 9.3 months beforehand, Jennifer A. Woyach, MD, and her associates from the Ohio State University, Columbus, concluded from a retrospective study of 308 patients. In a separate prospective study of 112 patients, acquired BTKC481S mutation and clonal expansion preceded all eight cases of relapse, they said. “Relapse of CLL after ibrutinib is an issue of increasing clinical significance,” they concluded. “We show that mutations in Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) and PLCG2 appear early and have the potential to be used as a biomarker for future relapse, suggesting an opportunity for intervention.”

Ibrutinib has transformed the CLL treatment landscape, but patients face poor outcomes if they relapse with Richter transformation or develop progressive disease. Past work has linked ibrutinib resistance to acquired mutations in BTK at the binding site of ibrutinib and in PLCG2 located just downstream. But the scope of ibrutinib resistance in CLL and key mutational players were unknown (J Clin Oncol. 2017. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.2282).

To fill that gap, the researchers retrospectively analyzed data from four sequential ibrutinib CLL trials at the Ohio State University. The separate prospective analysis involved analyzing the entire BTK and PLCG2 coding regions every 3 months.

In the retrospective study, patients had received a median of 3 and up to 16 prior therapies. Given the median follow-up period of 3.4 years, about 19% of patients experienced clinical relapse within 4 years of starting ibrutinib, the researchers estimated (95% confidence interval, 14%-24%). Deep sequencing by Ion Torrent (Life Technologies) identified mutations in BTKC481S and/or PLCG2, in 40 of 47 (85%) relapses. In 31 cases, BTKC481S was the sole mutation. Mutational burdens varied among patients, but generally correlated with CLL progression in peripheral blood versus primarily nodal relapse.

At baseline, 172 (58%) of retrospective study participants had complex cytogenetics, 52% had del(13q), 40% had del(17p), and 21% had MYC abnormality. Median age was 65 years (range, 26-91 years) and 70% of patients were female. Multivariable analyses linked transformation to complex karyotype (hazard ratio, 5.0; 95% CI, 1.5-16.5) and MYC abnormality (HR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.0-4.7), and linked progressive CLL to age younger than 65 years, complex karyotype, and del(17)(p13.1).

Richter transformation usually occurred within 2 years of starting ibrutinib and had a cumulative 4-year incidence of 10%, the investigators also reported. Patients survived a median of only 3.9 months after stopping ibrutinib because of transformation. The cumulative rate of progressive CLL was higher (19.1%), but early progression was rare, and patients who stopped ibrutinib because of progression survived longer (median, 22.7 months).

In the prospective study, all eight patients with BTKC481S who had not yet clinically relapsed nonetheless had increasing frequency of this mutation over time, the investigators reported. Together, the findings confirm BTK and PLCG2 mutations as the key players in CLL resistance to ibrutinib, they stated. Perhaps most importantly, they reveal “a prolonged period of asymptomatic clonal expression” in CLL that precedes clinical relapse and provides a window of opportunity to target these cells with novel therapies in clinical trials, they wrote.

Given that ibrutinib was approved for use in relapsed CLL only 2 years ago, “We are likely just starting to see the first emergence of relapse in the community setting,” the researchers concluded. “Enhanced knowledge of both the molecular and clinical mechanisms of relapse may allow for strategic alterations in monitoring and management that could change the natural history of ibrutinib resistance.”

Funding sources included the D. Warren Brown Foundation, Mr. and Mrs. Michael Thomas, the Four Winds Foundation, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Pelotonia, and the National Cancer Institute. Pharmacyclics also provided partial support. Dr. Woyach disclosed ties to Janssen, Acerta Pharma, Karyopharm Therapeutics, and MorphoSys, and a provisional patent related to C481S detection.

Acquired BTKC481S and PLCG2 mutations led to ibrutinib resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), investigators reported online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

These mutations preceded 85% of clinical relapses, appearing a median of 9.3 months beforehand, Jennifer A. Woyach, MD, and her associates from the Ohio State University, Columbus, concluded from a retrospective study of 308 patients. In a separate prospective study of 112 patients, acquired BTKC481S mutation and clonal expansion preceded all eight cases of relapse, they said. “Relapse of CLL after ibrutinib is an issue of increasing clinical significance,” they concluded. “We show that mutations in Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) and PLCG2 appear early and have the potential to be used as a biomarker for future relapse, suggesting an opportunity for intervention.”

Ibrutinib has transformed the CLL treatment landscape, but patients face poor outcomes if they relapse with Richter transformation or develop progressive disease. Past work has linked ibrutinib resistance to acquired mutations in BTK at the binding site of ibrutinib and in PLCG2 located just downstream. But the scope of ibrutinib resistance in CLL and key mutational players were unknown (J Clin Oncol. 2017. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.2282).

To fill that gap, the researchers retrospectively analyzed data from four sequential ibrutinib CLL trials at the Ohio State University. The separate prospective analysis involved analyzing the entire BTK and PLCG2 coding regions every 3 months.

In the retrospective study, patients had received a median of 3 and up to 16 prior therapies. Given the median follow-up period of 3.4 years, about 19% of patients experienced clinical relapse within 4 years of starting ibrutinib, the researchers estimated (95% confidence interval, 14%-24%). Deep sequencing by Ion Torrent (Life Technologies) identified mutations in BTKC481S and/or PLCG2, in 40 of 47 (85%) relapses. In 31 cases, BTKC481S was the sole mutation. Mutational burdens varied among patients, but generally correlated with CLL progression in peripheral blood versus primarily nodal relapse.

At baseline, 172 (58%) of retrospective study participants had complex cytogenetics, 52% had del(13q), 40% had del(17p), and 21% had MYC abnormality. Median age was 65 years (range, 26-91 years) and 70% of patients were female. Multivariable analyses linked transformation to complex karyotype (hazard ratio, 5.0; 95% CI, 1.5-16.5) and MYC abnormality (HR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.0-4.7), and linked progressive CLL to age younger than 65 years, complex karyotype, and del(17)(p13.1).

Richter transformation usually occurred within 2 years of starting ibrutinib and had a cumulative 4-year incidence of 10%, the investigators also reported. Patients survived a median of only 3.9 months after stopping ibrutinib because of transformation. The cumulative rate of progressive CLL was higher (19.1%), but early progression was rare, and patients who stopped ibrutinib because of progression survived longer (median, 22.7 months).

In the prospective study, all eight patients with BTKC481S who had not yet clinically relapsed nonetheless had increasing frequency of this mutation over time, the investigators reported. Together, the findings confirm BTK and PLCG2 mutations as the key players in CLL resistance to ibrutinib, they stated. Perhaps most importantly, they reveal “a prolonged period of asymptomatic clonal expression” in CLL that precedes clinical relapse and provides a window of opportunity to target these cells with novel therapies in clinical trials, they wrote.

Given that ibrutinib was approved for use in relapsed CLL only 2 years ago, “We are likely just starting to see the first emergence of relapse in the community setting,” the researchers concluded. “Enhanced knowledge of both the molecular and clinical mechanisms of relapse may allow for strategic alterations in monitoring and management that could change the natural history of ibrutinib resistance.”

Funding sources included the D. Warren Brown Foundation, Mr. and Mrs. Michael Thomas, the Four Winds Foundation, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Pelotonia, and the National Cancer Institute. Pharmacyclics also provided partial support. Dr. Woyach disclosed ties to Janssen, Acerta Pharma, Karyopharm Therapeutics, and MorphoSys, and a provisional patent related to C481S detection.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Acquired mutations in BTKC481S and PLCG2 predict ibrutinib resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Major finding: These mutations appeared a median of 9.3 months before clinical relapse in 85% of cases. In a separate study, all eight CLL patients who relapsed on ibrutinib had previously developed the BTKC481S mutation with clonal expansion.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of 308 CLL patients from four ibrutinib trials, and a separate prospective study of 118 CLL patients.

Disclosures: Funding sources included the D. Warren Brown Foundation, Mr. and Mrs. Michael Thomas, the Four Winds Foundation, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Pelotonia, and the National Cancer Institute. Pharmacyclics also provided partial support. Dr. Woyach disclosed ties to Janssen, Acerta Pharma, Karyopharm Therapeutics, and MorphoSys, and a provisional patent related to C481S detection.

In active CLL with deletion 17p, consider trial enrollment

NEW YORK – Outside of clinical trials, therapy for early stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia in patients with deletion of the short arm of chromosome 17 (del[17]p) and/or mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53 requires the presence of active disease, according to Neil E. Kay, MD.

“Right now, we would propose that patients with del[17]p should have additional prognostic work-up. It’s very important to know if they are unmutated or mutated for the IgVH gene,” he said, adding that stimulated karyotype is also important to perform in those with del[17]p.

“The median overall survivorship in many phase II and phase III trials appears to be around 2 to 3 years,” he said.

Those with a chromosome 17 (del[17]p) and/or mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53 who receive chemoimmunotherapy very rarely achieve a complete response, or if they do they have a short duration of response, he added.

In treated patients, 17p deletion and p53 mutation are the most common abnormalities acquired during the course of the disease.

“Unfortunately there appears to be a selection pressure, and [in treated patients] the incidence of 17p and the p53 mutation has been reported up to 23%-44%. No one understands completely the biology of this, but it may be that subclones are present and expand, or that new mutations occur due to selection pressure of [chemoimmunotherapy] and the overgrowth of these subclones,” he said.

Importantly, not all patients with del[17]p or p53 mutation have bad outcomes; there are patients with indolent disease, he noted, adding that various criteria have been shown to help identify which patients are at risk for poor outcomes and to classify them according to risk. In general, lower-risk patients have mutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene status, early stage disease, younger age, good performance status, and normal serum lactate dehydrogenase. These criteria could be used to identify low-risk patients who can be followed, he said.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) evaluation of patients is a useful tool when there is no access to sequencing and other tests, Dr. Kay said, describing a recent multinational CLL Research Consortium study of nearly 1,600 patients (Br J Haematol. 2016 Apr;173[1]:105-13).

In that study, he and his colleagues found that patients with less than 50% 17p did not have such poor outcomes, but at 50%-plus they did much worse in terms of time to first treatment.

Based on the available data, Dr. Kay said that treatment is unnecessary in asymptomatic patients, except, perhaps, in high-risk patients identified using recently published risk models, for whom clinical trial enrollment may be considered.

“We do advocate having a discussion about allogeneic stem cell transplant since this may still be the only curative approach,” he added.

In patients with del[17]p and/or p53 mutation who have progressive disease, Dr. Kay said his take on the available data is that patients should first be categorized by age, then by whether they are fit or frail, and finally by whether or not they have del[17]p. Those under age 70 years without del[17]p and who have a mutated IgVH status should be considered for a clinical trial, and are also good candidates for chemoimmunotherapy. If they do have del[17]p or p53 mutation, consider clinical trial enrollment or treatment with ibrutinib, he said.

Fit patients in a complete response can be referred for transplant evaluation, but while the other treatments can be considered in frail patients or those aged 70 years or older, transplant is not advised, he added.

For relapsed or refractory patients, FISH testing should be performed or repeated, because such patients are at high risk of progression to develop del[17]p or mutation, he noted.

Those who are asymptomatic can be observed or enrolled in a clinical trial, and those who are symptomatic can be enrolled in a clinical trial or treated with various novel agents, including ibrutinib, idelalisib/rituximab, venetoclax, or combination therapies with methylpred–anti-CD20, or alemtuzumab with or without rituximab. Referral for transplant may be warranted in these patients if they are fit.

“Progressive CLL patients with 17p deletion/p53 mutations are much less likely to do well with chemoimmunotherapy, and novel inhibitors are effective, but we still need to enhance complete response rates and minimal residual disease-negative status for these high-risk patients,” he said.

Dr. Kay reported consulting for or receiving grant/research support from Acerta, Celgene, Gilead, Infinity, MorphoSys, Pharmacyclics, and Tolero.

NEW YORK – Outside of clinical trials, therapy for early stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia in patients with deletion of the short arm of chromosome 17 (del[17]p) and/or mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53 requires the presence of active disease, according to Neil E. Kay, MD.

“Right now, we would propose that patients with del[17]p should have additional prognostic work-up. It’s very important to know if they are unmutated or mutated for the IgVH gene,” he said, adding that stimulated karyotype is also important to perform in those with del[17]p.

“The median overall survivorship in many phase II and phase III trials appears to be around 2 to 3 years,” he said.

Those with a chromosome 17 (del[17]p) and/or mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53 who receive chemoimmunotherapy very rarely achieve a complete response, or if they do they have a short duration of response, he added.

In treated patients, 17p deletion and p53 mutation are the most common abnormalities acquired during the course of the disease.

“Unfortunately there appears to be a selection pressure, and [in treated patients] the incidence of 17p and the p53 mutation has been reported up to 23%-44%. No one understands completely the biology of this, but it may be that subclones are present and expand, or that new mutations occur due to selection pressure of [chemoimmunotherapy] and the overgrowth of these subclones,” he said.

Importantly, not all patients with del[17]p or p53 mutation have bad outcomes; there are patients with indolent disease, he noted, adding that various criteria have been shown to help identify which patients are at risk for poor outcomes and to classify them according to risk. In general, lower-risk patients have mutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene status, early stage disease, younger age, good performance status, and normal serum lactate dehydrogenase. These criteria could be used to identify low-risk patients who can be followed, he said.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) evaluation of patients is a useful tool when there is no access to sequencing and other tests, Dr. Kay said, describing a recent multinational CLL Research Consortium study of nearly 1,600 patients (Br J Haematol. 2016 Apr;173[1]:105-13).

In that study, he and his colleagues found that patients with less than 50% 17p did not have such poor outcomes, but at 50%-plus they did much worse in terms of time to first treatment.

Based on the available data, Dr. Kay said that treatment is unnecessary in asymptomatic patients, except, perhaps, in high-risk patients identified using recently published risk models, for whom clinical trial enrollment may be considered.

“We do advocate having a discussion about allogeneic stem cell transplant since this may still be the only curative approach,” he added.

In patients with del[17]p and/or p53 mutation who have progressive disease, Dr. Kay said his take on the available data is that patients should first be categorized by age, then by whether they are fit or frail, and finally by whether or not they have del[17]p. Those under age 70 years without del[17]p and who have a mutated IgVH status should be considered for a clinical trial, and are also good candidates for chemoimmunotherapy. If they do have del[17]p or p53 mutation, consider clinical trial enrollment or treatment with ibrutinib, he said.

Fit patients in a complete response can be referred for transplant evaluation, but while the other treatments can be considered in frail patients or those aged 70 years or older, transplant is not advised, he added.

For relapsed or refractory patients, FISH testing should be performed or repeated, because such patients are at high risk of progression to develop del[17]p or mutation, he noted.

Those who are asymptomatic can be observed or enrolled in a clinical trial, and those who are symptomatic can be enrolled in a clinical trial or treated with various novel agents, including ibrutinib, idelalisib/rituximab, venetoclax, or combination therapies with methylpred–anti-CD20, or alemtuzumab with or without rituximab. Referral for transplant may be warranted in these patients if they are fit.

“Progressive CLL patients with 17p deletion/p53 mutations are much less likely to do well with chemoimmunotherapy, and novel inhibitors are effective, but we still need to enhance complete response rates and minimal residual disease-negative status for these high-risk patients,” he said.

Dr. Kay reported consulting for or receiving grant/research support from Acerta, Celgene, Gilead, Infinity, MorphoSys, Pharmacyclics, and Tolero.

NEW YORK – Outside of clinical trials, therapy for early stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia in patients with deletion of the short arm of chromosome 17 (del[17]p) and/or mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53 requires the presence of active disease, according to Neil E. Kay, MD.

“Right now, we would propose that patients with del[17]p should have additional prognostic work-up. It’s very important to know if they are unmutated or mutated for the IgVH gene,” he said, adding that stimulated karyotype is also important to perform in those with del[17]p.

“The median overall survivorship in many phase II and phase III trials appears to be around 2 to 3 years,” he said.

Those with a chromosome 17 (del[17]p) and/or mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53 who receive chemoimmunotherapy very rarely achieve a complete response, or if they do they have a short duration of response, he added.

In treated patients, 17p deletion and p53 mutation are the most common abnormalities acquired during the course of the disease.

“Unfortunately there appears to be a selection pressure, and [in treated patients] the incidence of 17p and the p53 mutation has been reported up to 23%-44%. No one understands completely the biology of this, but it may be that subclones are present and expand, or that new mutations occur due to selection pressure of [chemoimmunotherapy] and the overgrowth of these subclones,” he said.

Importantly, not all patients with del[17]p or p53 mutation have bad outcomes; there are patients with indolent disease, he noted, adding that various criteria have been shown to help identify which patients are at risk for poor outcomes and to classify them according to risk. In general, lower-risk patients have mutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene status, early stage disease, younger age, good performance status, and normal serum lactate dehydrogenase. These criteria could be used to identify low-risk patients who can be followed, he said.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) evaluation of patients is a useful tool when there is no access to sequencing and other tests, Dr. Kay said, describing a recent multinational CLL Research Consortium study of nearly 1,600 patients (Br J Haematol. 2016 Apr;173[1]:105-13).

In that study, he and his colleagues found that patients with less than 50% 17p did not have such poor outcomes, but at 50%-plus they did much worse in terms of time to first treatment.

Based on the available data, Dr. Kay said that treatment is unnecessary in asymptomatic patients, except, perhaps, in high-risk patients identified using recently published risk models, for whom clinical trial enrollment may be considered.

“We do advocate having a discussion about allogeneic stem cell transplant since this may still be the only curative approach,” he added.

In patients with del[17]p and/or p53 mutation who have progressive disease, Dr. Kay said his take on the available data is that patients should first be categorized by age, then by whether they are fit or frail, and finally by whether or not they have del[17]p. Those under age 70 years without del[17]p and who have a mutated IgVH status should be considered for a clinical trial, and are also good candidates for chemoimmunotherapy. If they do have del[17]p or p53 mutation, consider clinical trial enrollment or treatment with ibrutinib, he said.

Fit patients in a complete response can be referred for transplant evaluation, but while the other treatments can be considered in frail patients or those aged 70 years or older, transplant is not advised, he added.

For relapsed or refractory patients, FISH testing should be performed or repeated, because such patients are at high risk of progression to develop del[17]p or mutation, he noted.

Those who are asymptomatic can be observed or enrolled in a clinical trial, and those who are symptomatic can be enrolled in a clinical trial or treated with various novel agents, including ibrutinib, idelalisib/rituximab, venetoclax, or combination therapies with methylpred–anti-CD20, or alemtuzumab with or without rituximab. Referral for transplant may be warranted in these patients if they are fit.

“Progressive CLL patients with 17p deletion/p53 mutations are much less likely to do well with chemoimmunotherapy, and novel inhibitors are effective, but we still need to enhance complete response rates and minimal residual disease-negative status for these high-risk patients,” he said.

Dr. Kay reported consulting for or receiving grant/research support from Acerta, Celgene, Gilead, Infinity, MorphoSys, Pharmacyclics, and Tolero.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM LYMPHOMA & MYELOMA

Why CLL may go chemo free

NEW YORK – The approach to treating chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is evolving, and while chemoimmunotherapy remains a reasonable initial option in some cases, a “chemo-free” approach is also a very real possibility, according to Bruce D. Cheson, MD.

A number of studies showing survival benefits with targeted therapies vs. chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) regimens have been completed, including studies that look specifically at outcomes by mutation status and other factors. One example – a likely game changer – is the ALLIANCE trial, a randomized phase III study of bendamustine plus rituximab vs. ibrutinib plus rituximab vs. ibrutinib alone in untreated CLL patients aged 65 years or older, Dr. Cheson of Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, said at an international congress on hematologic malignancies.

“I think [the ALLIANCE] trial has the possibility of totally changing how we treat patients with CLL, even though it was done in older patients,” he said, noting that the study is completed, but final results are pending adequate follow-up.

Based on the available data, he suggests a treatment paradigm for untreated CLL patients who require therapy that begins with consideration of patient age, comorbidities, functional status, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

While clinical trial enrollment is preferable, those who are CIT eligible based on age and comorbidities can be treated with bendamustine/rituximab (BR), fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab (FCR), or ibrutinib.

“I think BR and FCR are both reasonable options, although the latter primarily for young, IGHV-mutated patients, and certainly ibrutinib remains an option for this patient population,” he said.

For those not eligible for CIT, options include ibrutinib and chlorambucil/obinutuzumab. For those with deletion 17p, ibrutinib is the standard for frontline therapy. And for those who are frail, ibrutinib is a good option.

“Some might use an anti-CD20, but as a single agent, it’s not what I would prefer,” Dr. Cheson said, explaining that response rates with such agents are low and tend to lack durability.

CIT remains a reasonable initial option for those patients who are mutated, but with the prolonged progression-free survival seen with ibrutinib in several trials, he predicted that will change over time.

“The role of targeted approaches is a subject of discussion. It takes the most time in my clinic of any discussion I have. [Patients ask] ‘Should I get ibrutinib? Should I get chemoimmunotherapy?’ ” he said. “One needs to take into account patient age and comorbidities, the fact that with CIT you are six [treatments] and done vs. indefinite therapy [with ibrutinib]. There is cost and there is compliance that one needs to consider.”

As for relapsed/refractory CLL, the role of CIT is particularly diminished in the wake of trials such as HELIOS and RESONATE, showing survival benefits with ibrutinib, others showing survival benefits with rituximab/idelalisib (R-idelalisib), and trials showing better results with venetoclax non-CIT regimens than would be expected with CIT regimens. As with treatment-naive CLL patients, age, comorbidities, functional status, and FISH should be considered in those with previously treated CLL who require therapy, and if clinical trial enrollment is not possible, treatment options depend on certain patient characteristics.

“For patients who had a long first response to chemoimmunotherapy, I would still use ibrutinib, and in select patients, R-idelalisib,” he said.

If they had a long response with BR, or FCR, retreatment with those can be considered as well, he noted, adding, “But I don’t see the point when the results with kinase inhibitors are at least as good as, if not better than one would expect with CIT in this context.”

In patients who had short first response, ibrutinib and R-idelalisib are the best options. For those with deletion 17p, the best options are ibrutinib or venetoclax, and possibly R-idelalisib. For frail patients, options include ibrutinib, R-idelalisib, or anti-CD20, although, as with untreated patients, the latter is his least favorite option because of the increased risk of toxicity in this population, he said.

“I think the role of chemoimmunotherapy in CLL is vanishing, and a chemo-free world for CLL patients is a reality,” he said.

Dr. Cheson reported consulting for Acerta, Celgene Pharmacyclics, and Roche-Genentech.

NEW YORK – The approach to treating chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is evolving, and while chemoimmunotherapy remains a reasonable initial option in some cases, a “chemo-free” approach is also a very real possibility, according to Bruce D. Cheson, MD.

A number of studies showing survival benefits with targeted therapies vs. chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) regimens have been completed, including studies that look specifically at outcomes by mutation status and other factors. One example – a likely game changer – is the ALLIANCE trial, a randomized phase III study of bendamustine plus rituximab vs. ibrutinib plus rituximab vs. ibrutinib alone in untreated CLL patients aged 65 years or older, Dr. Cheson of Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, said at an international congress on hematologic malignancies.

“I think [the ALLIANCE] trial has the possibility of totally changing how we treat patients with CLL, even though it was done in older patients,” he said, noting that the study is completed, but final results are pending adequate follow-up.

Based on the available data, he suggests a treatment paradigm for untreated CLL patients who require therapy that begins with consideration of patient age, comorbidities, functional status, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

While clinical trial enrollment is preferable, those who are CIT eligible based on age and comorbidities can be treated with bendamustine/rituximab (BR), fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab (FCR), or ibrutinib.

“I think BR and FCR are both reasonable options, although the latter primarily for young, IGHV-mutated patients, and certainly ibrutinib remains an option for this patient population,” he said.

For those not eligible for CIT, options include ibrutinib and chlorambucil/obinutuzumab. For those with deletion 17p, ibrutinib is the standard for frontline therapy. And for those who are frail, ibrutinib is a good option.

“Some might use an anti-CD20, but as a single agent, it’s not what I would prefer,” Dr. Cheson said, explaining that response rates with such agents are low and tend to lack durability.

CIT remains a reasonable initial option for those patients who are mutated, but with the prolonged progression-free survival seen with ibrutinib in several trials, he predicted that will change over time.

“The role of targeted approaches is a subject of discussion. It takes the most time in my clinic of any discussion I have. [Patients ask] ‘Should I get ibrutinib? Should I get chemoimmunotherapy?’ ” he said. “One needs to take into account patient age and comorbidities, the fact that with CIT you are six [treatments] and done vs. indefinite therapy [with ibrutinib]. There is cost and there is compliance that one needs to consider.”

As for relapsed/refractory CLL, the role of CIT is particularly diminished in the wake of trials such as HELIOS and RESONATE, showing survival benefits with ibrutinib, others showing survival benefits with rituximab/idelalisib (R-idelalisib), and trials showing better results with venetoclax non-CIT regimens than would be expected with CIT regimens. As with treatment-naive CLL patients, age, comorbidities, functional status, and FISH should be considered in those with previously treated CLL who require therapy, and if clinical trial enrollment is not possible, treatment options depend on certain patient characteristics.

“For patients who had a long first response to chemoimmunotherapy, I would still use ibrutinib, and in select patients, R-idelalisib,” he said.

If they had a long response with BR, or FCR, retreatment with those can be considered as well, he noted, adding, “But I don’t see the point when the results with kinase inhibitors are at least as good as, if not better than one would expect with CIT in this context.”

In patients who had short first response, ibrutinib and R-idelalisib are the best options. For those with deletion 17p, the best options are ibrutinib or venetoclax, and possibly R-idelalisib. For frail patients, options include ibrutinib, R-idelalisib, or anti-CD20, although, as with untreated patients, the latter is his least favorite option because of the increased risk of toxicity in this population, he said.

“I think the role of chemoimmunotherapy in CLL is vanishing, and a chemo-free world for CLL patients is a reality,” he said.

Dr. Cheson reported consulting for Acerta, Celgene Pharmacyclics, and Roche-Genentech.

NEW YORK – The approach to treating chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is evolving, and while chemoimmunotherapy remains a reasonable initial option in some cases, a “chemo-free” approach is also a very real possibility, according to Bruce D. Cheson, MD.

A number of studies showing survival benefits with targeted therapies vs. chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) regimens have been completed, including studies that look specifically at outcomes by mutation status and other factors. One example – a likely game changer – is the ALLIANCE trial, a randomized phase III study of bendamustine plus rituximab vs. ibrutinib plus rituximab vs. ibrutinib alone in untreated CLL patients aged 65 years or older, Dr. Cheson of Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, said at an international congress on hematologic malignancies.

“I think [the ALLIANCE] trial has the possibility of totally changing how we treat patients with CLL, even though it was done in older patients,” he said, noting that the study is completed, but final results are pending adequate follow-up.

Based on the available data, he suggests a treatment paradigm for untreated CLL patients who require therapy that begins with consideration of patient age, comorbidities, functional status, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

While clinical trial enrollment is preferable, those who are CIT eligible based on age and comorbidities can be treated with bendamustine/rituximab (BR), fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab (FCR), or ibrutinib.

“I think BR and FCR are both reasonable options, although the latter primarily for young, IGHV-mutated patients, and certainly ibrutinib remains an option for this patient population,” he said.

For those not eligible for CIT, options include ibrutinib and chlorambucil/obinutuzumab. For those with deletion 17p, ibrutinib is the standard for frontline therapy. And for those who are frail, ibrutinib is a good option.

“Some might use an anti-CD20, but as a single agent, it’s not what I would prefer,” Dr. Cheson said, explaining that response rates with such agents are low and tend to lack durability.

CIT remains a reasonable initial option for those patients who are mutated, but with the prolonged progression-free survival seen with ibrutinib in several trials, he predicted that will change over time.

“The role of targeted approaches is a subject of discussion. It takes the most time in my clinic of any discussion I have. [Patients ask] ‘Should I get ibrutinib? Should I get chemoimmunotherapy?’ ” he said. “One needs to take into account patient age and comorbidities, the fact that with CIT you are six [treatments] and done vs. indefinite therapy [with ibrutinib]. There is cost and there is compliance that one needs to consider.”

As for relapsed/refractory CLL, the role of CIT is particularly diminished in the wake of trials such as HELIOS and RESONATE, showing survival benefits with ibrutinib, others showing survival benefits with rituximab/idelalisib (R-idelalisib), and trials showing better results with venetoclax non-CIT regimens than would be expected with CIT regimens. As with treatment-naive CLL patients, age, comorbidities, functional status, and FISH should be considered in those with previously treated CLL who require therapy, and if clinical trial enrollment is not possible, treatment options depend on certain patient characteristics.

“For patients who had a long first response to chemoimmunotherapy, I would still use ibrutinib, and in select patients, R-idelalisib,” he said.

If they had a long response with BR, or FCR, retreatment with those can be considered as well, he noted, adding, “But I don’t see the point when the results with kinase inhibitors are at least as good as, if not better than one would expect with CIT in this context.”

In patients who had short first response, ibrutinib and R-idelalisib are the best options. For those with deletion 17p, the best options are ibrutinib or venetoclax, and possibly R-idelalisib. For frail patients, options include ibrutinib, R-idelalisib, or anti-CD20, although, as with untreated patients, the latter is his least favorite option because of the increased risk of toxicity in this population, he said.

“I think the role of chemoimmunotherapy in CLL is vanishing, and a chemo-free world for CLL patients is a reality,” he said.

Dr. Cheson reported consulting for Acerta, Celgene Pharmacyclics, and Roche-Genentech.

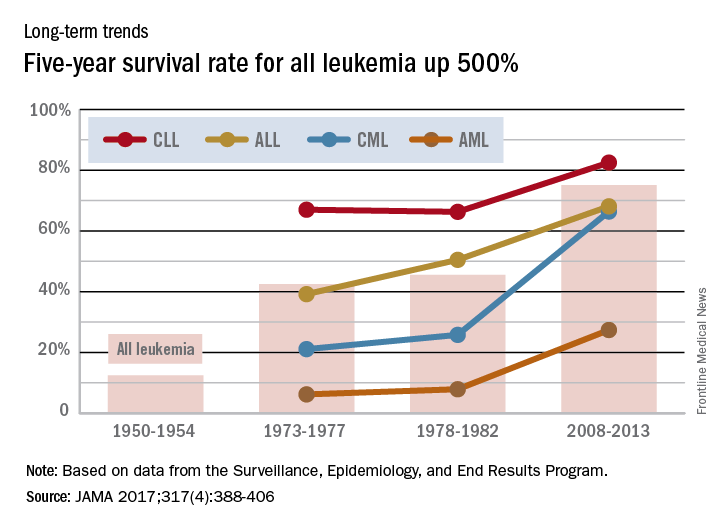

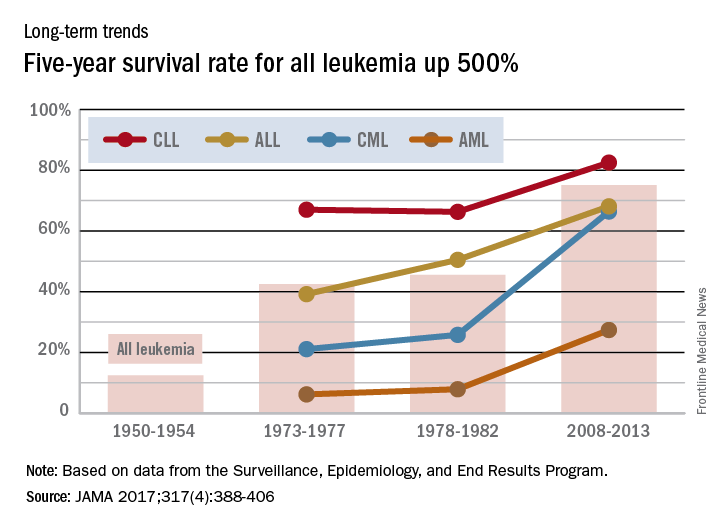

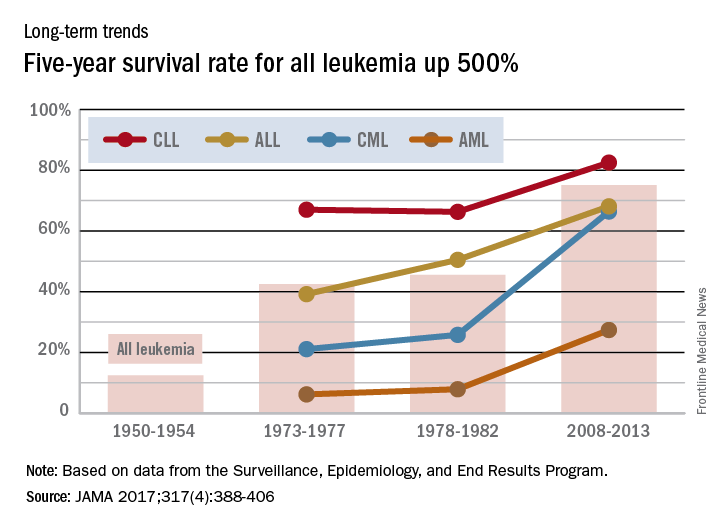

AML leads percent gains in 5-year survival among leukemias

Over the 60-year span from the early 1950s to 2013, the 5-year survival rate for all leukemias increased by 500%, according to data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

For 2008-2013, the 5-year relative survival rate for all leukemias was 60.1%, compared with 10% during 1950-1954, said Ali H. Mokdad, PhD, and his associates at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle (JAMA 2017;317[4]:388-406).

Over the 60-year span from the early 1950s to 2013, the 5-year survival rate for all leukemias increased by 500%, according to data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

For 2008-2013, the 5-year relative survival rate for all leukemias was 60.1%, compared with 10% during 1950-1954, said Ali H. Mokdad, PhD, and his associates at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle (JAMA 2017;317[4]:388-406).

Over the 60-year span from the early 1950s to 2013, the 5-year survival rate for all leukemias increased by 500%, according to data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

For 2008-2013, the 5-year relative survival rate for all leukemias was 60.1%, compared with 10% during 1950-1954, said Ali H. Mokdad, PhD, and his associates at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle (JAMA 2017;317[4]:388-406).

Lenalidomide maintenance extended progression-free survival in high-risk CLL

SAN DIEGO – Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia at risk for early relapse were about 85% less likely to progress on lenalidomide maintenance therapy compared with placebo, based on an interim analysis of the randomized phase III CLLM1 study.

After a typical follow-up time of 17.5 months, median durations of progression-free survival were not reached with lenalidomide and were 13 months with placebo, for a hazard ratio of 0.15 (95% confidence interval, 0.06-0.35). These results were “statistically significant, robust, and reliable in favor of lenalidomide,” Anna Fink, MD, said at the 2016 meeting of the American Society of Hematology. Several patients in the lenalidomide arm also converted to minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity, added Dr. Fink of University Hospital Cologne (Germany).

The study included patients whose CLL responded at least partially to front-line chemoimmunotherapy, but who were at high risk of progression – minimal residual disease levels were at least 10–2, or were between 10–4 and 10–2 in patients who also had an unmutated IGHV gene status or del(17p) or TP53 mutations at baseline. Among 89 patients who met these criteria, 60 received lenalidomide maintenance and 20 received placebo.

The initial lenalidomide cycle consisted of 5 mg daily for 28 days. To achieve MRD negativity, clinicians increased this dose during subsequent cycles to a maximum of 15 mg daily for patients who were MRD negative after cycle 12, 20 mg for patients who were MRD negative after cycle 18, and 25 mg for patients who remained MRD positive. Median age was 64 years, more than 80% of patients were male, and the median cumulative illness rating was relatively low at 2, ranging between 0 and 8.

A total of 37% of patients had a high MRD level and 63% had an intermediate level. For both cohorts, lenalidomide maintenance significantly prolonged progression-free survival, compared with placebo, with hazard ratios of 0.17 and 0.13, respectively. Patients received a median of 11 and up to 40 cycles of lenalidomide, but a median of only 8 cycles of placebo.

In all, 43% of lenalidomide patients and 72% of placebo patients stopped maintenance. Nearly a third of those who discontinued lenalidomide did so because of adverse events, but 45% of patients who stopped placebo did so because of progressive disease, Dr. Fink said. Lenalidomide was associated with more neutropenia, gastrointestinal disorders, nervous system disorders, and respiratory and skin disorders than was placebo, but the events were usually mild to moderate in severity, she added.

The three deaths in this study yielded no treatment-based difference in rates of overall survival. Causes of death included acute lymphoblastic leukemia (lenalidomide arm), progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (placebo), and Richter’s syndrome (placebo). Venous thromboembolic events were uncommon because patients were given low-dose aspirin or anticoagulant therapy, Dr. Fink noted.

“Lenalidomide is a feasible and efficacious maintenance option for high-risk CLL after chemoimmunotherapy,” she concluded. The low duration of progression-free survival in the placebo group confirms the prognostic utility of assessing risk based on MRD, which might be useful in future studies, she added.

The German CLL Study Group sponsored the trial. Dr. Fink disclosed ties to Mundipharma, Roche, Celgene, and AbbVie.

SAN DIEGO – Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia at risk for early relapse were about 85% less likely to progress on lenalidomide maintenance therapy compared with placebo, based on an interim analysis of the randomized phase III CLLM1 study.

After a typical follow-up time of 17.5 months, median durations of progression-free survival were not reached with lenalidomide and were 13 months with placebo, for a hazard ratio of 0.15 (95% confidence interval, 0.06-0.35). These results were “statistically significant, robust, and reliable in favor of lenalidomide,” Anna Fink, MD, said at the 2016 meeting of the American Society of Hematology. Several patients in the lenalidomide arm also converted to minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity, added Dr. Fink of University Hospital Cologne (Germany).

The study included patients whose CLL responded at least partially to front-line chemoimmunotherapy, but who were at high risk of progression – minimal residual disease levels were at least 10–2, or were between 10–4 and 10–2 in patients who also had an unmutated IGHV gene status or del(17p) or TP53 mutations at baseline. Among 89 patients who met these criteria, 60 received lenalidomide maintenance and 20 received placebo.

The initial lenalidomide cycle consisted of 5 mg daily for 28 days. To achieve MRD negativity, clinicians increased this dose during subsequent cycles to a maximum of 15 mg daily for patients who were MRD negative after cycle 12, 20 mg for patients who were MRD negative after cycle 18, and 25 mg for patients who remained MRD positive. Median age was 64 years, more than 80% of patients were male, and the median cumulative illness rating was relatively low at 2, ranging between 0 and 8.

A total of 37% of patients had a high MRD level and 63% had an intermediate level. For both cohorts, lenalidomide maintenance significantly prolonged progression-free survival, compared with placebo, with hazard ratios of 0.17 and 0.13, respectively. Patients received a median of 11 and up to 40 cycles of lenalidomide, but a median of only 8 cycles of placebo.

In all, 43% of lenalidomide patients and 72% of placebo patients stopped maintenance. Nearly a third of those who discontinued lenalidomide did so because of adverse events, but 45% of patients who stopped placebo did so because of progressive disease, Dr. Fink said. Lenalidomide was associated with more neutropenia, gastrointestinal disorders, nervous system disorders, and respiratory and skin disorders than was placebo, but the events were usually mild to moderate in severity, she added.

The three deaths in this study yielded no treatment-based difference in rates of overall survival. Causes of death included acute lymphoblastic leukemia (lenalidomide arm), progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (placebo), and Richter’s syndrome (placebo). Venous thromboembolic events were uncommon because patients were given low-dose aspirin or anticoagulant therapy, Dr. Fink noted.

“Lenalidomide is a feasible and efficacious maintenance option for high-risk CLL after chemoimmunotherapy,” she concluded. The low duration of progression-free survival in the placebo group confirms the prognostic utility of assessing risk based on MRD, which might be useful in future studies, she added.

The German CLL Study Group sponsored the trial. Dr. Fink disclosed ties to Mundipharma, Roche, Celgene, and AbbVie.

SAN DIEGO – Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia at risk for early relapse were about 85% less likely to progress on lenalidomide maintenance therapy compared with placebo, based on an interim analysis of the randomized phase III CLLM1 study.

After a typical follow-up time of 17.5 months, median durations of progression-free survival were not reached with lenalidomide and were 13 months with placebo, for a hazard ratio of 0.15 (95% confidence interval, 0.06-0.35). These results were “statistically significant, robust, and reliable in favor of lenalidomide,” Anna Fink, MD, said at the 2016 meeting of the American Society of Hematology. Several patients in the lenalidomide arm also converted to minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity, added Dr. Fink of University Hospital Cologne (Germany).

The study included patients whose CLL responded at least partially to front-line chemoimmunotherapy, but who were at high risk of progression – minimal residual disease levels were at least 10–2, or were between 10–4 and 10–2 in patients who also had an unmutated IGHV gene status or del(17p) or TP53 mutations at baseline. Among 89 patients who met these criteria, 60 received lenalidomide maintenance and 20 received placebo.

The initial lenalidomide cycle consisted of 5 mg daily for 28 days. To achieve MRD negativity, clinicians increased this dose during subsequent cycles to a maximum of 15 mg daily for patients who were MRD negative after cycle 12, 20 mg for patients who were MRD negative after cycle 18, and 25 mg for patients who remained MRD positive. Median age was 64 years, more than 80% of patients were male, and the median cumulative illness rating was relatively low at 2, ranging between 0 and 8.

A total of 37% of patients had a high MRD level and 63% had an intermediate level. For both cohorts, lenalidomide maintenance significantly prolonged progression-free survival, compared with placebo, with hazard ratios of 0.17 and 0.13, respectively. Patients received a median of 11 and up to 40 cycles of lenalidomide, but a median of only 8 cycles of placebo.

In all, 43% of lenalidomide patients and 72% of placebo patients stopped maintenance. Nearly a third of those who discontinued lenalidomide did so because of adverse events, but 45% of patients who stopped placebo did so because of progressive disease, Dr. Fink said. Lenalidomide was associated with more neutropenia, gastrointestinal disorders, nervous system disorders, and respiratory and skin disorders than was placebo, but the events were usually mild to moderate in severity, she added.

The three deaths in this study yielded no treatment-based difference in rates of overall survival. Causes of death included acute lymphoblastic leukemia (lenalidomide arm), progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (placebo), and Richter’s syndrome (placebo). Venous thromboembolic events were uncommon because patients were given low-dose aspirin or anticoagulant therapy, Dr. Fink noted.

“Lenalidomide is a feasible and efficacious maintenance option for high-risk CLL after chemoimmunotherapy,” she concluded. The low duration of progression-free survival in the placebo group confirms the prognostic utility of assessing risk based on MRD, which might be useful in future studies, she added.

The German CLL Study Group sponsored the trial. Dr. Fink disclosed ties to Mundipharma, Roche, Celgene, and AbbVie.

AT ASH 2016

Key clinical point: Lenalidomide maintenance may be an option for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia at risk of early progression.

Major finding: Median progression-free survival times were 13 months with placebo but were not reached with lenalidomide, for a hazard ratio of 0.15 (95% confidence interval, 0.06-0.35).

Data source: An interim analysis of 89 partial responders to frontline chemotherapy in the randomized, phase III CLLM1 study.

Disclosures: The German CLL Study Group sponsored the trial. Dr. Fink disclosed ties to Mundipharma, Roche, Celgene, and AbbVie.

Ibrutinib continues to wow in CLL/SLL

SAN DIEGO – More than 90% of the first patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia who received ibrutinib in an early study are alive and without disease progression 5 years later, investigators reported.

Among 31 treatment-naive patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic leukemia (CLL/SLL) who were started on the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) in the phase Ib/II PCYC-1102/1103 study, the 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate was 92%, with the median PFS not reached. Estimated 5-year overall survival (OS) among these patients was also 92%, with the median not reached, Susan O’Brien, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

The 5-year PFS rate for patients with relapsed/refractory disease who had received a median of four prior lines of therapy before starting on single-agent ibrutinib was 43%, with a median PFS of 52 months. In this group, the overall survival (OS) rate was 57%, with the median not reached.

“At 5 years of follow-up, there are very durable responses in treatment-naive and relapsed refractory patients. You saw that, in the treatment-naive group, there is, in fact, only one patient who has progressed so far,” Dr. O’Brien said.

In a separate study, investigators from the phase III RESONATE-2 trial reported updated safety and efficacy data showing that in first-line therapy for patients aged 65 years and older with CLL/SLL with active disease, ibrutinib was associated with significantly better PFS at 24 months, compared with chlorambucil.

In this study by Dr. O’Brien and colleagues, 31 patients with previously untreated CLL/SLL and 101 patients with relapsed/refractory disease (progression or no objective response within 24 months of starting on chemoimmunotherapy) were treated with oral ibrutinib once daily at doses of 420 mg or 840 mg until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

After 5 years of follow-up, 20 of the 31 treatment-naive patients (65%) and 30 of the 101 relapsed/refractory patients (30%) remained on ibrutinib therapy. The primary reasons for discontinuation among relapsed/refractory patients included progressive disease in 33%, adverse events in 21%, and investigator decision in 11%.

Best response rates in treatment-naive patients were 87% (29% complete response, 55% partial response, 3% partial response-L) and 89% in relapsed/refractory patients (10%, 76%, and 3%, respectively).

An analysis of survival by IGHV (immunoglobulin heavy chain variable) mutational status in patients with relapsed/refractory disease showed a 53% 5-year PFS rate among patients with mutated IGHV and a median PFS of 63 months, compared with 38% and 43 months for patients with unmutated IGHV. Respective 5-year overall survival rates were 66% (median OS, 63 months) and 55% (median not reached).

In an analysis of survival outcomes by chromosomal abnormalities detected by FISH (fluorescent in situ hybridization) among patients with relapsed/refractory disease, median PFS and OS rates were highest among patients with the 13q deletion, at 91% for both PFS and OS, compared with 80% for each in patients with trisomy 12, 33% and 61% for patients with deletion 11q, and 19% and 32% for patients with deletion 17p. In patients with no chromosomal abnormalities, the 5-year PFS rate was 66% (median not reached), and the 5-year OS rate was 83% (median not reached).

Among patients with complex karyotype, 90% of whom had relapsed refractory disease, the 5-year PFS rate was 36% (median 33 months), and the OS rate was 46% (median 57 months). In contrast, respective PFS and OS rates for patients without complex karyotype were 69% and 84%, with the median not reached in either survival category.

In multivariate analysis, only deletion 17p was identified as a significant predictor of PFS and OS.

Grade 3 or greater treatment-emergent adverse events occurred mostly frequently in the first year of therapy and declined thereafter. The most common grade 3 or greater events were hypertension, (26% of all patients), pneumonia (22%), neutropenia (17%), and atrial fibrillation (9%).

Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester presented updated data from RESONATE-2, comparing ibrutinib with chlorambucil in patients 65 and older with newly diagnosed, active CLL/SLL.

At a median follow-up of 29 months, the rates of 2-year PFS were 89% for patients treated with ibrutinib (median PFS not reached) vs. 34% for chlorambucil (median PFS 15 months). This translated into a hazard ratio for ibrutinib of 0.121 (P less than .0001). The benefit of ibrutinib occurred without regard to IGHV status, and ibrutinib continues to demonstrate an OS benefit over chlorambucil with longer follow-up and crossover. Overall survival at 24 months was 95% for patients treated with ibrutinib (included 55 patients who were crossed over from chlorambucil) vs. 84% for patients treated with chlorambucil only.

“The depth of the responses has improved over time, now with 18% of patients achieving a CR with ibrutinib, and lastly, ibrutinib remains tolerable in this elderly population, with 79% of patients that are continuing on therapy,” Dr. Barr said.

Both studies were funded by Pharmacyclics. Dr. Barr and Dr. O’Brien disclosed serving as consultants to the company, and Dr. O’Brien further disclosed honoraria and research funding from Pharmacyclics.

SAN DIEGO – More than 90% of the first patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia who received ibrutinib in an early study are alive and without disease progression 5 years later, investigators reported.

Among 31 treatment-naive patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic leukemia (CLL/SLL) who were started on the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) in the phase Ib/II PCYC-1102/1103 study, the 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate was 92%, with the median PFS not reached. Estimated 5-year overall survival (OS) among these patients was also 92%, with the median not reached, Susan O’Brien, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

The 5-year PFS rate for patients with relapsed/refractory disease who had received a median of four prior lines of therapy before starting on single-agent ibrutinib was 43%, with a median PFS of 52 months. In this group, the overall survival (OS) rate was 57%, with the median not reached.

“At 5 years of follow-up, there are very durable responses in treatment-naive and relapsed refractory patients. You saw that, in the treatment-naive group, there is, in fact, only one patient who has progressed so far,” Dr. O’Brien said.

In a separate study, investigators from the phase III RESONATE-2 trial reported updated safety and efficacy data showing that in first-line therapy for patients aged 65 years and older with CLL/SLL with active disease, ibrutinib was associated with significantly better PFS at 24 months, compared with chlorambucil.

In this study by Dr. O’Brien and colleagues, 31 patients with previously untreated CLL/SLL and 101 patients with relapsed/refractory disease (progression or no objective response within 24 months of starting on chemoimmunotherapy) were treated with oral ibrutinib once daily at doses of 420 mg or 840 mg until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

After 5 years of follow-up, 20 of the 31 treatment-naive patients (65%) and 30 of the 101 relapsed/refractory patients (30%) remained on ibrutinib therapy. The primary reasons for discontinuation among relapsed/refractory patients included progressive disease in 33%, adverse events in 21%, and investigator decision in 11%.

Best response rates in treatment-naive patients were 87% (29% complete response, 55% partial response, 3% partial response-L) and 89% in relapsed/refractory patients (10%, 76%, and 3%, respectively).

An analysis of survival by IGHV (immunoglobulin heavy chain variable) mutational status in patients with relapsed/refractory disease showed a 53% 5-year PFS rate among patients with mutated IGHV and a median PFS of 63 months, compared with 38% and 43 months for patients with unmutated IGHV. Respective 5-year overall survival rates were 66% (median OS, 63 months) and 55% (median not reached).

In an analysis of survival outcomes by chromosomal abnormalities detected by FISH (fluorescent in situ hybridization) among patients with relapsed/refractory disease, median PFS and OS rates were highest among patients with the 13q deletion, at 91% for both PFS and OS, compared with 80% for each in patients with trisomy 12, 33% and 61% for patients with deletion 11q, and 19% and 32% for patients with deletion 17p. In patients with no chromosomal abnormalities, the 5-year PFS rate was 66% (median not reached), and the 5-year OS rate was 83% (median not reached).

Among patients with complex karyotype, 90% of whom had relapsed refractory disease, the 5-year PFS rate was 36% (median 33 months), and the OS rate was 46% (median 57 months). In contrast, respective PFS and OS rates for patients without complex karyotype were 69% and 84%, with the median not reached in either survival category.

In multivariate analysis, only deletion 17p was identified as a significant predictor of PFS and OS.

Grade 3 or greater treatment-emergent adverse events occurred mostly frequently in the first year of therapy and declined thereafter. The most common grade 3 or greater events were hypertension, (26% of all patients), pneumonia (22%), neutropenia (17%), and atrial fibrillation (9%).

Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester presented updated data from RESONATE-2, comparing ibrutinib with chlorambucil in patients 65 and older with newly diagnosed, active CLL/SLL.

At a median follow-up of 29 months, the rates of 2-year PFS were 89% for patients treated with ibrutinib (median PFS not reached) vs. 34% for chlorambucil (median PFS 15 months). This translated into a hazard ratio for ibrutinib of 0.121 (P less than .0001). The benefit of ibrutinib occurred without regard to IGHV status, and ibrutinib continues to demonstrate an OS benefit over chlorambucil with longer follow-up and crossover. Overall survival at 24 months was 95% for patients treated with ibrutinib (included 55 patients who were crossed over from chlorambucil) vs. 84% for patients treated with chlorambucil only.

“The depth of the responses has improved over time, now with 18% of patients achieving a CR with ibrutinib, and lastly, ibrutinib remains tolerable in this elderly population, with 79% of patients that are continuing on therapy,” Dr. Barr said.

Both studies were funded by Pharmacyclics. Dr. Barr and Dr. O’Brien disclosed serving as consultants to the company, and Dr. O’Brien further disclosed honoraria and research funding from Pharmacyclics.

SAN DIEGO – More than 90% of the first patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia who received ibrutinib in an early study are alive and without disease progression 5 years later, investigators reported.

Among 31 treatment-naive patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic leukemia (CLL/SLL) who were started on the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) in the phase Ib/II PCYC-1102/1103 study, the 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate was 92%, with the median PFS not reached. Estimated 5-year overall survival (OS) among these patients was also 92%, with the median not reached, Susan O’Brien, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

The 5-year PFS rate for patients with relapsed/refractory disease who had received a median of four prior lines of therapy before starting on single-agent ibrutinib was 43%, with a median PFS of 52 months. In this group, the overall survival (OS) rate was 57%, with the median not reached.

“At 5 years of follow-up, there are very durable responses in treatment-naive and relapsed refractory patients. You saw that, in the treatment-naive group, there is, in fact, only one patient who has progressed so far,” Dr. O’Brien said.

In a separate study, investigators from the phase III RESONATE-2 trial reported updated safety and efficacy data showing that in first-line therapy for patients aged 65 years and older with CLL/SLL with active disease, ibrutinib was associated with significantly better PFS at 24 months, compared with chlorambucil.

In this study by Dr. O’Brien and colleagues, 31 patients with previously untreated CLL/SLL and 101 patients with relapsed/refractory disease (progression or no objective response within 24 months of starting on chemoimmunotherapy) were treated with oral ibrutinib once daily at doses of 420 mg or 840 mg until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

After 5 years of follow-up, 20 of the 31 treatment-naive patients (65%) and 30 of the 101 relapsed/refractory patients (30%) remained on ibrutinib therapy. The primary reasons for discontinuation among relapsed/refractory patients included progressive disease in 33%, adverse events in 21%, and investigator decision in 11%.

Best response rates in treatment-naive patients were 87% (29% complete response, 55% partial response, 3% partial response-L) and 89% in relapsed/refractory patients (10%, 76%, and 3%, respectively).

An analysis of survival by IGHV (immunoglobulin heavy chain variable) mutational status in patients with relapsed/refractory disease showed a 53% 5-year PFS rate among patients with mutated IGHV and a median PFS of 63 months, compared with 38% and 43 months for patients with unmutated IGHV. Respective 5-year overall survival rates were 66% (median OS, 63 months) and 55% (median not reached).

In an analysis of survival outcomes by chromosomal abnormalities detected by FISH (fluorescent in situ hybridization) among patients with relapsed/refractory disease, median PFS and OS rates were highest among patients with the 13q deletion, at 91% for both PFS and OS, compared with 80% for each in patients with trisomy 12, 33% and 61% for patients with deletion 11q, and 19% and 32% for patients with deletion 17p. In patients with no chromosomal abnormalities, the 5-year PFS rate was 66% (median not reached), and the 5-year OS rate was 83% (median not reached).

Among patients with complex karyotype, 90% of whom had relapsed refractory disease, the 5-year PFS rate was 36% (median 33 months), and the OS rate was 46% (median 57 months). In contrast, respective PFS and OS rates for patients without complex karyotype were 69% and 84%, with the median not reached in either survival category.

In multivariate analysis, only deletion 17p was identified as a significant predictor of PFS and OS.

Grade 3 or greater treatment-emergent adverse events occurred mostly frequently in the first year of therapy and declined thereafter. The most common grade 3 or greater events were hypertension, (26% of all patients), pneumonia (22%), neutropenia (17%), and atrial fibrillation (9%).

Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester presented updated data from RESONATE-2, comparing ibrutinib with chlorambucil in patients 65 and older with newly diagnosed, active CLL/SLL.

At a median follow-up of 29 months, the rates of 2-year PFS were 89% for patients treated with ibrutinib (median PFS not reached) vs. 34% for chlorambucil (median PFS 15 months). This translated into a hazard ratio for ibrutinib of 0.121 (P less than .0001). The benefit of ibrutinib occurred without regard to IGHV status, and ibrutinib continues to demonstrate an OS benefit over chlorambucil with longer follow-up and crossover. Overall survival at 24 months was 95% for patients treated with ibrutinib (included 55 patients who were crossed over from chlorambucil) vs. 84% for patients treated with chlorambucil only.

“The depth of the responses has improved over time, now with 18% of patients achieving a CR with ibrutinib, and lastly, ibrutinib remains tolerable in this elderly population, with 79% of patients that are continuing on therapy,” Dr. Barr said.

Both studies were funded by Pharmacyclics. Dr. Barr and Dr. O’Brien disclosed serving as consultants to the company, and Dr. O’Brien further disclosed honoraria and research funding from Pharmacyclics.

AT ASH 2016

Key clinical point: Long-term follow-up of two studies shows a progression-free and overall survival advantage with ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic leukemia.

Major finding: 5-year PFS and OS rates were 92% for treatment-naive patients with CLL/SLL treated with ibrutinib.

Data source: Phase Ib/II study and randomized phase III study of ibrutinib for treatment-naive and relapsed/refractory CLL/SLL.

Disclosures: Both studies were funded by Pharmacyclics. Dr. Barr and Dr. O’Brien disclosed serving as consultants to the company; Dr. O’Brien disclosed honoraria and research funding from the company.

Lenalidomide improves PFS after 1st and 2nd line CLL therapy

SAN DIEGO – Lenalidomide, a mainstay of maintenance therapy for multiple myeloma, is now making inroads into maintenance therapy following first- and second-line therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), investigators reported in two phase III studies.

Among patients with previously untreated CLL who were at high risk for early disease progression following standard chemotherapy, lenalidomide (Revlimid) maintenance therapy was associated with an 80% reduction in the relative risk for disease progression compared with placebo, reported Anna Fink, MD, of the University of Cologne, Germany, and her colleagues in the German CLL Study Group.

Similarly, lenalidomide maintenance significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared with placebo among patients with CLL who had at least partial responses to second-line therapy, reported Anna Schuh, MD, of the University of Oxford, England, and her colleagues in the CONTINUUM trial.

“Lenalidomide maintenance therapy significantly improved progression-free survival, from just about 9 months to almost 40 months when given to patients with CLL who responded to second-line therapy,” Dr. Schuh said at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting.

Both studies were unblinded because of the superiority of lenalidomide after prespecified analyses, on the recommendation of the respective data safety monitoring boards (DSMBs).

The PFS advantage with lenalidomide seen in each study did not translate into differences in overall survival in either study, however.

Maintenance after first-line therapy

In the CLLM1 trial, Dr. Fink and her colleagues enrolled physically fit, previously untreated patients with CLL and delivered chemoimmunotherapy at the investigator’s choice: either FCR (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab), FR (fludarabine and rituximab), FC (fludarabine and cyclophosphamide), or BR (bendamustine and rituximab).

Patients who had at least a partial response after a minimum of four cycles were identified as being at high risk for progression if they had minimal residual disease (MRD) levels of at least 10-2 cells, or MRD levels from 10-4 to less than 10-2 combined with either an unmutated IGHV gene status, del(17p) or TP53 mutation at baseline.

Of 468 screened patients, 89 were deemed to have high risk disease, and these patients were randomly assigned on a 2:1 basis to maintenance with lenalidomide given 5 mg orally for the first cycle and escalated to a target dose of 15 mg by the seventh cycle, or to placebo.

Additional dose escalations could be performed based on MRD assessments every 6 months, with the drug continued until progression or unacceptable toxicity. Patients also were assigned to daily low-dose aspirin or to an anticoagulation agent depending on their individual risk for thromboembolic events.

The study was stopped and unblinded after a planned interim analysis showed that the difference in PFS met the stopping boundary for efficacy.

Ultimately, 56 patients assigned to lenalidomide received study treatment, as did 29 assigned to placebo.

At a median follow-up of 17.5 months, the median PFS according to independent review was not reached for lenalidomide, vs. 13.3 months for placebo. Lenalidomide was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) for progression of 0.148 (P less than .00001), and a relative risk reduction of 80%.

Lenalidomide was also significantly better for PFS in analysis by MRD at baseline, with a PFS of 19.4 months for placebo vs. not reached among patients with less than 10-2 but more than 10-4 cells (HR, 0.125) and 3.7 vs. 32.3 months, respectively, for patients with MRD greater than 10-2 (HR 0.165).

There were three deaths (two in patients on placebo), and at the last analysis there was no difference in overall survival. In all, 42.9% of patients on lenalidomide discontinued because of adverse events, compared with 72.4% of those on placebo.

Maintenance after second-line therapy

In CONTINUUM, patients with at least a partial response after two prior lines of therapy and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of 0-2 were enrolled and randomized to receive either lenalidomide (160 patients) at a starting dose of 2.5 mg/day for the first 28-day cycle, 5 mg/day from cycle 2, and, if well tolerated, up to 10 mg/day from cycle 7 on, or to placebo (154 patients).

This study, as noted before, was also unblinded at the time of the primary analysis as recommended by the DSMB, after a prespecified number of events had occurred.

At a median follow-up of 31.5 months, the median PFS, a co-primary endpoint with OS, was 33.9 months in the lenalidomide arm, compared with 9.2 months in the placebo arm, translating into a HR for lenalidomide of 0.40 (P less than .001).

The lenalidomide advantage also was seen in a subgroup analysis by age, prior response to chemotherapy, and number of factors for poor prognosis. Of note, among patients older than age 70, the PFS with lenalidomide was 52.5 months, compared with 7.3 months for placebo (HR 0.34, P = .005).

In a second PFS analysis conducted after 71 months of follow-up, lenalidomide remained superior, with a median PFS of 57.5 months vs. 32.7 months in the placebo arm. As noted, there was no difference in overall survival in this study.

Grade 3 or greater adverse events occurring more frequently with lenalidomide were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, diarrhea, pneumonia, fatigue, hypokalemia, pulmonary embolism, and sepsis. There was no difference in the incidence of second primary malignancies, however.

CLLM1 was sponsored by the German CLL Study Group with support from Celgene. CONTINUUM was supported by Celgene. Dr. Fink disclosed research funding from the company, and travel grants and honoraria from others. Dr. Schuh disclosed honoraria from and consulting with Celgene and other companies.

SAN DIEGO – Lenalidomide, a mainstay of maintenance therapy for multiple myeloma, is now making inroads into maintenance therapy following first- and second-line therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), investigators reported in two phase III studies.

Among patients with previously untreated CLL who were at high risk for early disease progression following standard chemotherapy, lenalidomide (Revlimid) maintenance therapy was associated with an 80% reduction in the relative risk for disease progression compared with placebo, reported Anna Fink, MD, of the University of Cologne, Germany, and her colleagues in the German CLL Study Group.

Similarly, lenalidomide maintenance significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared with placebo among patients with CLL who had at least partial responses to second-line therapy, reported Anna Schuh, MD, of the University of Oxford, England, and her colleagues in the CONTINUUM trial.

“Lenalidomide maintenance therapy significantly improved progression-free survival, from just about 9 months to almost 40 months when given to patients with CLL who responded to second-line therapy,” Dr. Schuh said at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting.

Both studies were unblinded because of the superiority of lenalidomide after prespecified analyses, on the recommendation of the respective data safety monitoring boards (DSMBs).

The PFS advantage with lenalidomide seen in each study did not translate into differences in overall survival in either study, however.

Maintenance after first-line therapy