User login

Medicare Fee Inspection

No one can call 2009 a dull year for healthcare policy. And 2010 already is shaping up as another humdinger, with several issues bubbling to the surface. One of the biggest comes courtesy of the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care (www.dartmouthatlas.org), as politicians, analysts, researchers, and physicians grapple over how to resolve the contentious issue of geographical disparities in healthcare spending.

One of the main bodies of evidence driving the debate, the interactive Dartmouth map, depicts a color-coded nation in which wide swaths of the Midwest and West are colored with a pale green hue, which represents a significantly reduced amount of Medicare reimbursements. Meanwhile, states such as New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Florida, Texas, and Louisiana are marked by a darker shade of green—representing the nation’s most expensive per capita reimbursement rates.

Tucked within 2009’s massive Affordable Health Care for America Act passed by the House is a provision calling for a study of “geographic variation in healthcare spending and promoting high-value healthcare,” which is aiming for a more evenly colored landscape.

More than 50 legislators, hailing primarily from the Midwest and Pacific Northwest and calling themselves the Quality Care Coalition, pushed through the wording as a condition for supporting the larger healthcare reform bill. One measure would direct the nonpartisan Institute of Medicine (IOM) to check the accuracy of the geographic adjustment factors that underlie existing Medicare reimbursements and suggest necessary revisions. The second would call upon the IOM “to conduct a study on geographic variation and growth in volume and intensity of services in per capita healthcare spending among the Medicare, Medicaid, privately insured, and uninsured populations.”

Recommendations to Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius as a result of that study would go into effect unless the House and Senate passed a joint resolution of disapproval with a two-thirds vote.

Reimbursement Battles

The implicit message is that some states, cities, and health providers have been shortchanged in their reimbursements—a complaint that flows into the larger meme that the country’s dysfunctional payment system rewards quantity, not quality. Officials at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., have suggested in media accounts that the current Medicare formula cost the clinic $840 million in lost reimbursements in 2008 alone.

Rep. Jay Inslee (D-Washington), whose district lies northwest of Seattle, served as one of the lead negotiators on the issue. According to Inslee spokesman Robert Kellar, the geographical disparity in healthcare spending has been a perennial concern for the Washington delegation due to reimbursement rates that lag by as much as 50%, depending on the procedure. “Hospitals haven’t been able to keep or attract the personnel that they could have because of this issue,” Kellar says. In Washington state, per capita Medicare reimbursements in 2006 hovered about $1,200 below the national average, though 15 other states, led by Hawaii, received even less.

Despite the specter of a skirmish between urban and rural states and hospitals, however, the Dartmouth Atlas suggests that many disparities are more geographically nuanced. In 2006, for example, the Miami hospital referral region received more than $16,300 in Medicare reimbursements per enrollee, while nearby Fort Lauderdale received $9,800 and Atlanta less than $7,400. By comparison, New York netted $12,100, Seattle received $7,200, Rochester, Minn., received $6,700, and Honolulu was reimbursed only $5,300.

Representatives of higher-spending areas have complained that the atlas doesn’t tell the whole story—that steep living costs, poorer populations seeking medical care, and infrastructure necessary for teaching institutions can drive up Medicare expenses. As part of a compromise negotiated with the Quality Care Coalition, the examination of per capita spending will not include expenses related to graduate medical education, disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, and health information technology.

In attempting to get at the source of remaining cost disparities, however, the IOM has been charged with considering such factors as a local population’s relative health and socioeconomic status (race, ethnicity, gender, age, income, and education). The study will scrutinize healthcare providers’ organizational models, practice patterns, healthcare outcomes, quality benchmarks, and doctors’ discretion in making treatment decisions, among other criteria.

Differences of Opinion

Dylan Roby, an assistant professor at the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, says the general expectation among healthcare analysts is that significant differences will remain even with additional sophisticated modeling techniques. “The main hypothesis by most people in the field is that it’s differences in practice patterns that are really driving this, not differences in need or differences in disease burden,” he says.

But what about outcomes? A recent study of heart failure patients at six California hospitals seemed to throw cold water on the notion that higher resource use doesn’t equate with better results with patients.1 The study found more treatment did lead to higher odds of survival.

Roby thinks the study’s results lay the framework for looking at hospital-to-hospital differences in how providers deliver care and allocate resources, but he cautions that they shouldn’t be overanalyzed. All six of the California hospitals in the study are linked to universities and have ample access to resources, he points out.

HM at the Forefront

As for hospitalists, Roby hopes they will be increasingly called upon as focal points for improving efficiencies within provider networks. He concedes that plenty of challenges remain: An institution’s internal politics, for instance, could stymie even the most efficient and proactive physician. Even so, Roby is hopeful that an independent study could at least spur a dialogue about best practices. “I think what the study could potentially do, rather than just act as a way to penalize hospitals that might not be efficient with care, is really offer the ability for us to look at the characteristics of hospitals, in terms of how the care is delivered,” he says.

Ideally, the ability to learn would be followed by the impetus to change. But as analysts have noted, a panel’s recommendations on how to improve healthcare delivery don’t always neatly translate into federal policy.

Consider November’s uproar over mammogram recommendations. When the 16-member U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that women wait until age 50 for routine mammograms instead of starting the screening process at 40, in large part to prevent overtreatment, the fallout was fast and furious. Sebelius quickly signaled in a strongly worded statement that federal policy wasn’t about to change, despite the evidence-based conclusions of a panel convened by her department’s Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. A group of Republican legislators decried the recommendation as evidence of bureaucrats intruding on healthcare decisions, and even Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schulz (D-Florida), herself a breast-cancer survivor, called the panel’s recommendations “disturbing” and considered Congressional hearings.

The take-home message is readily transferrable to hospitalists: The perception that patients might receive less care can spark public upheaval and force policy makers to beat a hasty retreat away from evidence-based medicine.

Despite the best intentions, a federal panel’s recommendations over resolving geographical disparities in spending could unleash far more drama. Inevitably, such a study will identify both winners and losers, the latter of whom might not accept reduced payments willingly or quietly. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance writer based in Seattle.

Reference

- Ellis SG, Miller D, Keys TF. Comparing physician-specific two-year patient outcomes after coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1278-1285.

No one can call 2009 a dull year for healthcare policy. And 2010 already is shaping up as another humdinger, with several issues bubbling to the surface. One of the biggest comes courtesy of the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care (www.dartmouthatlas.org), as politicians, analysts, researchers, and physicians grapple over how to resolve the contentious issue of geographical disparities in healthcare spending.

One of the main bodies of evidence driving the debate, the interactive Dartmouth map, depicts a color-coded nation in which wide swaths of the Midwest and West are colored with a pale green hue, which represents a significantly reduced amount of Medicare reimbursements. Meanwhile, states such as New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Florida, Texas, and Louisiana are marked by a darker shade of green—representing the nation’s most expensive per capita reimbursement rates.

Tucked within 2009’s massive Affordable Health Care for America Act passed by the House is a provision calling for a study of “geographic variation in healthcare spending and promoting high-value healthcare,” which is aiming for a more evenly colored landscape.

More than 50 legislators, hailing primarily from the Midwest and Pacific Northwest and calling themselves the Quality Care Coalition, pushed through the wording as a condition for supporting the larger healthcare reform bill. One measure would direct the nonpartisan Institute of Medicine (IOM) to check the accuracy of the geographic adjustment factors that underlie existing Medicare reimbursements and suggest necessary revisions. The second would call upon the IOM “to conduct a study on geographic variation and growth in volume and intensity of services in per capita healthcare spending among the Medicare, Medicaid, privately insured, and uninsured populations.”

Recommendations to Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius as a result of that study would go into effect unless the House and Senate passed a joint resolution of disapproval with a two-thirds vote.

Reimbursement Battles

The implicit message is that some states, cities, and health providers have been shortchanged in their reimbursements—a complaint that flows into the larger meme that the country’s dysfunctional payment system rewards quantity, not quality. Officials at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., have suggested in media accounts that the current Medicare formula cost the clinic $840 million in lost reimbursements in 2008 alone.

Rep. Jay Inslee (D-Washington), whose district lies northwest of Seattle, served as one of the lead negotiators on the issue. According to Inslee spokesman Robert Kellar, the geographical disparity in healthcare spending has been a perennial concern for the Washington delegation due to reimbursement rates that lag by as much as 50%, depending on the procedure. “Hospitals haven’t been able to keep or attract the personnel that they could have because of this issue,” Kellar says. In Washington state, per capita Medicare reimbursements in 2006 hovered about $1,200 below the national average, though 15 other states, led by Hawaii, received even less.

Despite the specter of a skirmish between urban and rural states and hospitals, however, the Dartmouth Atlas suggests that many disparities are more geographically nuanced. In 2006, for example, the Miami hospital referral region received more than $16,300 in Medicare reimbursements per enrollee, while nearby Fort Lauderdale received $9,800 and Atlanta less than $7,400. By comparison, New York netted $12,100, Seattle received $7,200, Rochester, Minn., received $6,700, and Honolulu was reimbursed only $5,300.

Representatives of higher-spending areas have complained that the atlas doesn’t tell the whole story—that steep living costs, poorer populations seeking medical care, and infrastructure necessary for teaching institutions can drive up Medicare expenses. As part of a compromise negotiated with the Quality Care Coalition, the examination of per capita spending will not include expenses related to graduate medical education, disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, and health information technology.

In attempting to get at the source of remaining cost disparities, however, the IOM has been charged with considering such factors as a local population’s relative health and socioeconomic status (race, ethnicity, gender, age, income, and education). The study will scrutinize healthcare providers’ organizational models, practice patterns, healthcare outcomes, quality benchmarks, and doctors’ discretion in making treatment decisions, among other criteria.

Differences of Opinion

Dylan Roby, an assistant professor at the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, says the general expectation among healthcare analysts is that significant differences will remain even with additional sophisticated modeling techniques. “The main hypothesis by most people in the field is that it’s differences in practice patterns that are really driving this, not differences in need or differences in disease burden,” he says.

But what about outcomes? A recent study of heart failure patients at six California hospitals seemed to throw cold water on the notion that higher resource use doesn’t equate with better results with patients.1 The study found more treatment did lead to higher odds of survival.

Roby thinks the study’s results lay the framework for looking at hospital-to-hospital differences in how providers deliver care and allocate resources, but he cautions that they shouldn’t be overanalyzed. All six of the California hospitals in the study are linked to universities and have ample access to resources, he points out.

HM at the Forefront

As for hospitalists, Roby hopes they will be increasingly called upon as focal points for improving efficiencies within provider networks. He concedes that plenty of challenges remain: An institution’s internal politics, for instance, could stymie even the most efficient and proactive physician. Even so, Roby is hopeful that an independent study could at least spur a dialogue about best practices. “I think what the study could potentially do, rather than just act as a way to penalize hospitals that might not be efficient with care, is really offer the ability for us to look at the characteristics of hospitals, in terms of how the care is delivered,” he says.

Ideally, the ability to learn would be followed by the impetus to change. But as analysts have noted, a panel’s recommendations on how to improve healthcare delivery don’t always neatly translate into federal policy.

Consider November’s uproar over mammogram recommendations. When the 16-member U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that women wait until age 50 for routine mammograms instead of starting the screening process at 40, in large part to prevent overtreatment, the fallout was fast and furious. Sebelius quickly signaled in a strongly worded statement that federal policy wasn’t about to change, despite the evidence-based conclusions of a panel convened by her department’s Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. A group of Republican legislators decried the recommendation as evidence of bureaucrats intruding on healthcare decisions, and even Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schulz (D-Florida), herself a breast-cancer survivor, called the panel’s recommendations “disturbing” and considered Congressional hearings.

The take-home message is readily transferrable to hospitalists: The perception that patients might receive less care can spark public upheaval and force policy makers to beat a hasty retreat away from evidence-based medicine.

Despite the best intentions, a federal panel’s recommendations over resolving geographical disparities in spending could unleash far more drama. Inevitably, such a study will identify both winners and losers, the latter of whom might not accept reduced payments willingly or quietly. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance writer based in Seattle.

Reference

- Ellis SG, Miller D, Keys TF. Comparing physician-specific two-year patient outcomes after coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1278-1285.

No one can call 2009 a dull year for healthcare policy. And 2010 already is shaping up as another humdinger, with several issues bubbling to the surface. One of the biggest comes courtesy of the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care (www.dartmouthatlas.org), as politicians, analysts, researchers, and physicians grapple over how to resolve the contentious issue of geographical disparities in healthcare spending.

One of the main bodies of evidence driving the debate, the interactive Dartmouth map, depicts a color-coded nation in which wide swaths of the Midwest and West are colored with a pale green hue, which represents a significantly reduced amount of Medicare reimbursements. Meanwhile, states such as New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Florida, Texas, and Louisiana are marked by a darker shade of green—representing the nation’s most expensive per capita reimbursement rates.

Tucked within 2009’s massive Affordable Health Care for America Act passed by the House is a provision calling for a study of “geographic variation in healthcare spending and promoting high-value healthcare,” which is aiming for a more evenly colored landscape.

More than 50 legislators, hailing primarily from the Midwest and Pacific Northwest and calling themselves the Quality Care Coalition, pushed through the wording as a condition for supporting the larger healthcare reform bill. One measure would direct the nonpartisan Institute of Medicine (IOM) to check the accuracy of the geographic adjustment factors that underlie existing Medicare reimbursements and suggest necessary revisions. The second would call upon the IOM “to conduct a study on geographic variation and growth in volume and intensity of services in per capita healthcare spending among the Medicare, Medicaid, privately insured, and uninsured populations.”

Recommendations to Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius as a result of that study would go into effect unless the House and Senate passed a joint resolution of disapproval with a two-thirds vote.

Reimbursement Battles

The implicit message is that some states, cities, and health providers have been shortchanged in their reimbursements—a complaint that flows into the larger meme that the country’s dysfunctional payment system rewards quantity, not quality. Officials at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., have suggested in media accounts that the current Medicare formula cost the clinic $840 million in lost reimbursements in 2008 alone.

Rep. Jay Inslee (D-Washington), whose district lies northwest of Seattle, served as one of the lead negotiators on the issue. According to Inslee spokesman Robert Kellar, the geographical disparity in healthcare spending has been a perennial concern for the Washington delegation due to reimbursement rates that lag by as much as 50%, depending on the procedure. “Hospitals haven’t been able to keep or attract the personnel that they could have because of this issue,” Kellar says. In Washington state, per capita Medicare reimbursements in 2006 hovered about $1,200 below the national average, though 15 other states, led by Hawaii, received even less.

Despite the specter of a skirmish between urban and rural states and hospitals, however, the Dartmouth Atlas suggests that many disparities are more geographically nuanced. In 2006, for example, the Miami hospital referral region received more than $16,300 in Medicare reimbursements per enrollee, while nearby Fort Lauderdale received $9,800 and Atlanta less than $7,400. By comparison, New York netted $12,100, Seattle received $7,200, Rochester, Minn., received $6,700, and Honolulu was reimbursed only $5,300.

Representatives of higher-spending areas have complained that the atlas doesn’t tell the whole story—that steep living costs, poorer populations seeking medical care, and infrastructure necessary for teaching institutions can drive up Medicare expenses. As part of a compromise negotiated with the Quality Care Coalition, the examination of per capita spending will not include expenses related to graduate medical education, disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, and health information technology.

In attempting to get at the source of remaining cost disparities, however, the IOM has been charged with considering such factors as a local population’s relative health and socioeconomic status (race, ethnicity, gender, age, income, and education). The study will scrutinize healthcare providers’ organizational models, practice patterns, healthcare outcomes, quality benchmarks, and doctors’ discretion in making treatment decisions, among other criteria.

Differences of Opinion

Dylan Roby, an assistant professor at the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, says the general expectation among healthcare analysts is that significant differences will remain even with additional sophisticated modeling techniques. “The main hypothesis by most people in the field is that it’s differences in practice patterns that are really driving this, not differences in need or differences in disease burden,” he says.

But what about outcomes? A recent study of heart failure patients at six California hospitals seemed to throw cold water on the notion that higher resource use doesn’t equate with better results with patients.1 The study found more treatment did lead to higher odds of survival.

Roby thinks the study’s results lay the framework for looking at hospital-to-hospital differences in how providers deliver care and allocate resources, but he cautions that they shouldn’t be overanalyzed. All six of the California hospitals in the study are linked to universities and have ample access to resources, he points out.

HM at the Forefront

As for hospitalists, Roby hopes they will be increasingly called upon as focal points for improving efficiencies within provider networks. He concedes that plenty of challenges remain: An institution’s internal politics, for instance, could stymie even the most efficient and proactive physician. Even so, Roby is hopeful that an independent study could at least spur a dialogue about best practices. “I think what the study could potentially do, rather than just act as a way to penalize hospitals that might not be efficient with care, is really offer the ability for us to look at the characteristics of hospitals, in terms of how the care is delivered,” he says.

Ideally, the ability to learn would be followed by the impetus to change. But as analysts have noted, a panel’s recommendations on how to improve healthcare delivery don’t always neatly translate into federal policy.

Consider November’s uproar over mammogram recommendations. When the 16-member U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that women wait until age 50 for routine mammograms instead of starting the screening process at 40, in large part to prevent overtreatment, the fallout was fast and furious. Sebelius quickly signaled in a strongly worded statement that federal policy wasn’t about to change, despite the evidence-based conclusions of a panel convened by her department’s Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. A group of Republican legislators decried the recommendation as evidence of bureaucrats intruding on healthcare decisions, and even Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schulz (D-Florida), herself a breast-cancer survivor, called the panel’s recommendations “disturbing” and considered Congressional hearings.

The take-home message is readily transferrable to hospitalists: The perception that patients might receive less care can spark public upheaval and force policy makers to beat a hasty retreat away from evidence-based medicine.

Despite the best intentions, a federal panel’s recommendations over resolving geographical disparities in spending could unleash far more drama. Inevitably, such a study will identify both winners and losers, the latter of whom might not accept reduced payments willingly or quietly. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance writer based in Seattle.

Reference

- Ellis SG, Miller D, Keys TF. Comparing physician-specific two-year patient outcomes after coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1278-1285.

Consultation Elimination

As of Jan. 1, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ceased physician payment for consultations. The elimination of consult codes will affect physician group payments as well as relative-value-unit (RVU)-based incentive payments to individual physicians.

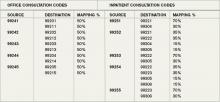

The Medicare-designated status of outpatient consultation (99241-99245) and inpatient consultation (99251-99255) codes has changed from “A” (separately payable under the physician fee schedule, when covered) to “I” (not valid for Medicare purposes; Medicare uses another code for the reporting of and the payment for these services). So if you submit consultation codes for Medicare beneficiaries, the result will be nonpayment.

While many physicians fear the negative impact of this ruling, hospitalists should consider its potential. Let’s take a look at a scenario hospitalists encounter on a routine basis.

Typical HM Scenario

A surgeon admits a 76-year-old man for aortic valve replacement. The patient’s history also includes well-controlled hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Postoperatively, the patient experiences an exacerbation of COPD related to anesthesia, elevated blood pressure, and hyperglycemia. The surgeon requests the hospitalist’s advice on appropriate medical interventions of these conditions. How should the hospitalist report the initial encounter with this Medicare beneficiary?

The hospitalist should select the CPT code that best fits the service and the payor. While most physicians regard this requested service as an inpatient consultation (99251-99255), Medicare no longer recognizes those codes. Instead, the hospitalist should report this encounter as an initial hospital care service (99221-99223).

Comanagement Issues

CMS and Medicare administrative contractors regularly uncover reporting errors for co-management requests. CMS decided the nature of these services were not consultative because the surgeon is not asking the physician or qualified nonphysician provider’s (NPP’s) opinion or advice for the surgeon’s use in treating the patient. Instead, these services constituted concurrent care and should have been billed using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233) in the hospital inpatient setting, subsequent NF care codes (99307-99310) in the SNF/NF setting, or office or other outpatient visit codes (99201-99215) in the office or outpatient settings.1

The new ruling simplifies coding and reduces reporting errors. The initial encounter with the patient is reported as such. Regardless of who is the attending of record or the consultant, the first physician from a particular provider group reports initial hospital care codes (i.e., 99221-99223) to represent the first patient encounter, even when this encounter does not occur on the admission date. Other physicians of the same specialty within the same provider group will not be permitted to report initial hospital care codes for their own initial encounter if someone from the group and specialty has already seen the patient during that hospitalization. In other words, the first hospitalist in the provider group reports 9922x, while the remaining hospitalists use subsequent hospital care codes (9923x).

In order to differentiate “consultant” services from “attending” services, CMS will be creating a modifier. The anticipated “AI” modifier must be appended to the attending physician’s initial encounter. Other initial hospital care codes reported throughout the hospital stay, as appropriate, are presumed to be that of “consultants” (i.e., physicians with a different specialty designation than the attending physician) participating in the case. Therefore, the hospitalist now can rightfully recover the increased work effort of the initial patient encounter (99223: 3.79 relative value units, ~$147 vs. 99233: 2.0 relative value units, ~$78, based on 2010 Medicare rates). Physicians will be required to meet the minimum documentation required for the selected visit code.

Other and Undefined Service Locations

Consultations in nursing facilities are handled much like inpatient hospital care. Physicians should report initial nursing facility services (99203-99306) for the first patient encounter, and subsequent nursing facility care codes (99307-99310) for each encounter thereafter. The attending physician of record appends the assigned modifier (presumed to be “AI”) when submitting their initial care service. All other initial care codes are presumed to be those of “consulting” physicians.

Initial information from CMS does not address observation services. Logically, these hospital-based services would follow the same methodology as inpatient care: report initial observation care (99218-99220) for the first “consulting” encounter. However, this might not be appropriate given Medicare’s existing rules for observation services, which guide physicians other than the admitting physician/group to “bill the office and other outpatient service codes or outpatient consultation codes as appropriate when they provide services to the patient.”2 With Medicare’s elimination of consultation codes, the consultant reports “office and other outpatient service codes” (i.e., new patient, 99201-99205, or established patient codes, 99212-99215) by default.

Without further clarification on observation services, hospitalists should report new or established patient service codes, depending on whether the patient has been seen by a group member within the last three years.

Medicare also has existing guidelines for the ED, which suggest that any physician not meeting the consultation criteria report ED service codes (99281-99285). Without further clarification, hospitalists should continue to follow this instruction for Medicare beneficiaries.

Nonphysician Providers

Medicare’s split/shared billing guidelines apply to most hospital inpatient, hospital outpatient, and ED evaluation and management (E/M) services, with consultations as one exception. Now, in accordance with the new ruling, hospitalists should select the appropriate initial service codes that correspond to patient’s location (e.g., 99223 for inpatients). NPPs can participate in the initial service provided to patients in these locations without the hospitalist having to replicate the entire service. The hospitalist can submit the claim in their name after selecting the visit level based upon the cumulative service personally provided on the same calendar day by both the NPP and the physician. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.10I. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/ manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8A. CMS Web site. Available at: www. cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- PFS Federal Regulation Notices: Proposed Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Part B for CY 2010. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/PhysicianFeeSched/PFSFRN/itemdetail.asp?filterType=none&filterByDID=99&sortByDID=4&sortOrder=descending&itemID=CMS1223902&intNumPerPage=10. Accessed Nov. 12, 2009.

- Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B (for CY 2010). CMS Web site. Available at: www.federalregister.gov/OFR Upload/OFRData/2009-26502_PI.pdf. Accessed Nov. 10, 2009.

As of Jan. 1, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ceased physician payment for consultations. The elimination of consult codes will affect physician group payments as well as relative-value-unit (RVU)-based incentive payments to individual physicians.

The Medicare-designated status of outpatient consultation (99241-99245) and inpatient consultation (99251-99255) codes has changed from “A” (separately payable under the physician fee schedule, when covered) to “I” (not valid for Medicare purposes; Medicare uses another code for the reporting of and the payment for these services). So if you submit consultation codes for Medicare beneficiaries, the result will be nonpayment.

While many physicians fear the negative impact of this ruling, hospitalists should consider its potential. Let’s take a look at a scenario hospitalists encounter on a routine basis.

Typical HM Scenario

A surgeon admits a 76-year-old man for aortic valve replacement. The patient’s history also includes well-controlled hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Postoperatively, the patient experiences an exacerbation of COPD related to anesthesia, elevated blood pressure, and hyperglycemia. The surgeon requests the hospitalist’s advice on appropriate medical interventions of these conditions. How should the hospitalist report the initial encounter with this Medicare beneficiary?

The hospitalist should select the CPT code that best fits the service and the payor. While most physicians regard this requested service as an inpatient consultation (99251-99255), Medicare no longer recognizes those codes. Instead, the hospitalist should report this encounter as an initial hospital care service (99221-99223).

Comanagement Issues

CMS and Medicare administrative contractors regularly uncover reporting errors for co-management requests. CMS decided the nature of these services were not consultative because the surgeon is not asking the physician or qualified nonphysician provider’s (NPP’s) opinion or advice for the surgeon’s use in treating the patient. Instead, these services constituted concurrent care and should have been billed using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233) in the hospital inpatient setting, subsequent NF care codes (99307-99310) in the SNF/NF setting, or office or other outpatient visit codes (99201-99215) in the office or outpatient settings.1

The new ruling simplifies coding and reduces reporting errors. The initial encounter with the patient is reported as such. Regardless of who is the attending of record or the consultant, the first physician from a particular provider group reports initial hospital care codes (i.e., 99221-99223) to represent the first patient encounter, even when this encounter does not occur on the admission date. Other physicians of the same specialty within the same provider group will not be permitted to report initial hospital care codes for their own initial encounter if someone from the group and specialty has already seen the patient during that hospitalization. In other words, the first hospitalist in the provider group reports 9922x, while the remaining hospitalists use subsequent hospital care codes (9923x).

In order to differentiate “consultant” services from “attending” services, CMS will be creating a modifier. The anticipated “AI” modifier must be appended to the attending physician’s initial encounter. Other initial hospital care codes reported throughout the hospital stay, as appropriate, are presumed to be that of “consultants” (i.e., physicians with a different specialty designation than the attending physician) participating in the case. Therefore, the hospitalist now can rightfully recover the increased work effort of the initial patient encounter (99223: 3.79 relative value units, ~$147 vs. 99233: 2.0 relative value units, ~$78, based on 2010 Medicare rates). Physicians will be required to meet the minimum documentation required for the selected visit code.

Other and Undefined Service Locations

Consultations in nursing facilities are handled much like inpatient hospital care. Physicians should report initial nursing facility services (99203-99306) for the first patient encounter, and subsequent nursing facility care codes (99307-99310) for each encounter thereafter. The attending physician of record appends the assigned modifier (presumed to be “AI”) when submitting their initial care service. All other initial care codes are presumed to be those of “consulting” physicians.

Initial information from CMS does not address observation services. Logically, these hospital-based services would follow the same methodology as inpatient care: report initial observation care (99218-99220) for the first “consulting” encounter. However, this might not be appropriate given Medicare’s existing rules for observation services, which guide physicians other than the admitting physician/group to “bill the office and other outpatient service codes or outpatient consultation codes as appropriate when they provide services to the patient.”2 With Medicare’s elimination of consultation codes, the consultant reports “office and other outpatient service codes” (i.e., new patient, 99201-99205, or established patient codes, 99212-99215) by default.

Without further clarification on observation services, hospitalists should report new or established patient service codes, depending on whether the patient has been seen by a group member within the last three years.

Medicare also has existing guidelines for the ED, which suggest that any physician not meeting the consultation criteria report ED service codes (99281-99285). Without further clarification, hospitalists should continue to follow this instruction for Medicare beneficiaries.

Nonphysician Providers

Medicare’s split/shared billing guidelines apply to most hospital inpatient, hospital outpatient, and ED evaluation and management (E/M) services, with consultations as one exception. Now, in accordance with the new ruling, hospitalists should select the appropriate initial service codes that correspond to patient’s location (e.g., 99223 for inpatients). NPPs can participate in the initial service provided to patients in these locations without the hospitalist having to replicate the entire service. The hospitalist can submit the claim in their name after selecting the visit level based upon the cumulative service personally provided on the same calendar day by both the NPP and the physician. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.10I. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/ manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8A. CMS Web site. Available at: www. cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- PFS Federal Regulation Notices: Proposed Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Part B for CY 2010. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/PhysicianFeeSched/PFSFRN/itemdetail.asp?filterType=none&filterByDID=99&sortByDID=4&sortOrder=descending&itemID=CMS1223902&intNumPerPage=10. Accessed Nov. 12, 2009.

- Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B (for CY 2010). CMS Web site. Available at: www.federalregister.gov/OFR Upload/OFRData/2009-26502_PI.pdf. Accessed Nov. 10, 2009.

As of Jan. 1, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ceased physician payment for consultations. The elimination of consult codes will affect physician group payments as well as relative-value-unit (RVU)-based incentive payments to individual physicians.

The Medicare-designated status of outpatient consultation (99241-99245) and inpatient consultation (99251-99255) codes has changed from “A” (separately payable under the physician fee schedule, when covered) to “I” (not valid for Medicare purposes; Medicare uses another code for the reporting of and the payment for these services). So if you submit consultation codes for Medicare beneficiaries, the result will be nonpayment.

While many physicians fear the negative impact of this ruling, hospitalists should consider its potential. Let’s take a look at a scenario hospitalists encounter on a routine basis.

Typical HM Scenario

A surgeon admits a 76-year-old man for aortic valve replacement. The patient’s history also includes well-controlled hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Postoperatively, the patient experiences an exacerbation of COPD related to anesthesia, elevated blood pressure, and hyperglycemia. The surgeon requests the hospitalist’s advice on appropriate medical interventions of these conditions. How should the hospitalist report the initial encounter with this Medicare beneficiary?

The hospitalist should select the CPT code that best fits the service and the payor. While most physicians regard this requested service as an inpatient consultation (99251-99255), Medicare no longer recognizes those codes. Instead, the hospitalist should report this encounter as an initial hospital care service (99221-99223).

Comanagement Issues

CMS and Medicare administrative contractors regularly uncover reporting errors for co-management requests. CMS decided the nature of these services were not consultative because the surgeon is not asking the physician or qualified nonphysician provider’s (NPP’s) opinion or advice for the surgeon’s use in treating the patient. Instead, these services constituted concurrent care and should have been billed using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233) in the hospital inpatient setting, subsequent NF care codes (99307-99310) in the SNF/NF setting, or office or other outpatient visit codes (99201-99215) in the office or outpatient settings.1

The new ruling simplifies coding and reduces reporting errors. The initial encounter with the patient is reported as such. Regardless of who is the attending of record or the consultant, the first physician from a particular provider group reports initial hospital care codes (i.e., 99221-99223) to represent the first patient encounter, even when this encounter does not occur on the admission date. Other physicians of the same specialty within the same provider group will not be permitted to report initial hospital care codes for their own initial encounter if someone from the group and specialty has already seen the patient during that hospitalization. In other words, the first hospitalist in the provider group reports 9922x, while the remaining hospitalists use subsequent hospital care codes (9923x).

In order to differentiate “consultant” services from “attending” services, CMS will be creating a modifier. The anticipated “AI” modifier must be appended to the attending physician’s initial encounter. Other initial hospital care codes reported throughout the hospital stay, as appropriate, are presumed to be that of “consultants” (i.e., physicians with a different specialty designation than the attending physician) participating in the case. Therefore, the hospitalist now can rightfully recover the increased work effort of the initial patient encounter (99223: 3.79 relative value units, ~$147 vs. 99233: 2.0 relative value units, ~$78, based on 2010 Medicare rates). Physicians will be required to meet the minimum documentation required for the selected visit code.

Other and Undefined Service Locations

Consultations in nursing facilities are handled much like inpatient hospital care. Physicians should report initial nursing facility services (99203-99306) for the first patient encounter, and subsequent nursing facility care codes (99307-99310) for each encounter thereafter. The attending physician of record appends the assigned modifier (presumed to be “AI”) when submitting their initial care service. All other initial care codes are presumed to be those of “consulting” physicians.

Initial information from CMS does not address observation services. Logically, these hospital-based services would follow the same methodology as inpatient care: report initial observation care (99218-99220) for the first “consulting” encounter. However, this might not be appropriate given Medicare’s existing rules for observation services, which guide physicians other than the admitting physician/group to “bill the office and other outpatient service codes or outpatient consultation codes as appropriate when they provide services to the patient.”2 With Medicare’s elimination of consultation codes, the consultant reports “office and other outpatient service codes” (i.e., new patient, 99201-99205, or established patient codes, 99212-99215) by default.

Without further clarification on observation services, hospitalists should report new or established patient service codes, depending on whether the patient has been seen by a group member within the last three years.

Medicare also has existing guidelines for the ED, which suggest that any physician not meeting the consultation criteria report ED service codes (99281-99285). Without further clarification, hospitalists should continue to follow this instruction for Medicare beneficiaries.

Nonphysician Providers

Medicare’s split/shared billing guidelines apply to most hospital inpatient, hospital outpatient, and ED evaluation and management (E/M) services, with consultations as one exception. Now, in accordance with the new ruling, hospitalists should select the appropriate initial service codes that correspond to patient’s location (e.g., 99223 for inpatients). NPPs can participate in the initial service provided to patients in these locations without the hospitalist having to replicate the entire service. The hospitalist can submit the claim in their name after selecting the visit level based upon the cumulative service personally provided on the same calendar day by both the NPP and the physician. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.10I. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/ manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8A. CMS Web site. Available at: www. cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- PFS Federal Regulation Notices: Proposed Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Part B for CY 2010. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/PhysicianFeeSched/PFSFRN/itemdetail.asp?filterType=none&filterByDID=99&sortByDID=4&sortOrder=descending&itemID=CMS1223902&intNumPerPage=10. Accessed Nov. 12, 2009.

- Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B (for CY 2010). CMS Web site. Available at: www.federalregister.gov/OFR Upload/OFRData/2009-26502_PI.pdf. Accessed Nov. 10, 2009.