User login

Cochrane Data: Food, Water in Labor OK in Low-Risk Women

Major Finding: In women at low risk of needing general anesthesia during childbirth, there was no significant association with eating and drinking during labor and the rate of cesarean section, operative vaginal birth, or Apgar scores of less than 7 at 5 minutes.

Data Source: A Cochrane database review of five randomized controlled trials comprising 3,130 women.

Disclosures: The review was sponsored by the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Liverpool, as well as the National Institute for Health Research, and by a World Health Organization grant. One of the authors was the primary investigator on a study included in the review.

Women at low risk of complications during childbirth should be allowed to take food and water as they desire during active labor, a Cochrane database review has concluded.

“The review identified no benefits or harms of restricting foods and fluids during labor in women at low risk of needing anesthesia,” wrote lead author Mandisa Singata, R.N., and her associates. “Given these findings, women should be free to eat and drink in labor or not, as they wish” (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010;CD003930 [doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003930.pub2]).

The review of five studies comprising 3,130 women suggests that the prohibition on oral intake during labor may be based on outdated concerns, wrote Ms. Singata of the University of Witwatersrand, East London, South Africa, and her associates.

“Restricting oral food and fluid intake … is a strongly held obstetric and anesthetic tradition,” related to research performed in the 1940s on regurgitation under general anesthetic and resulting inhalation pneumonia. “Most [eating prohibitions] are based on historical, but important, concerns related to these risks. … The incidence is very rare with modern anesthetic techniques and the use of regional rather than general anesthesia.”

Ms. Singata and her colleagues identified five randomized controlled trials that examined this issue. The studies were conducted from 1999 to 2009.

All included women at low risk of requiring general anesthesia during childbirth. One study looked at restricting intake to ice chips and sips of water vs. full access to food and drink. Two compared water only to encouraging the consumption of some food and fluid, and two compared water only to carbohydrate drinks during labor.

The analysis was dominated by the largest and most recent study, which contained 2,443 women. The other four studies together comprised 687 women. The largest study was conducted in a “highly medicalized environment,” in which 30% of women had a cesarean section, over 50% had oxytocin, just under 70% received intravenous fluids and epidural anesthesia, and 27% underwent operative vaginal birth.

“In addition, 20% of the women in the water-only arm ate during labor and 295 in the food and fluid arm chose not to eat in labor. This clearly reflects the wide variation in women's wishes for food and fluids during labor,” the authors wrote.

When considering any restriction of food and fluid versus allowing them, the authors found no significant associations with the rate of cesarean section, operative vaginal birth, or Apgar scores of less than 7 at 5 minutes. Neither were there significant relationships with duration of labor, maternal nausea or vomiting, narcotic pain relief, or infant admission to intensive care.

None of the outcomes were significantly related in any of the other analyses: complete restriction of food and fluid vs. freedom to eat and drink, water only vs. freedom to eat and drink, or complete food and fluid restriction vs. carbohydrate-based fluid only.

Major Finding: In women at low risk of needing general anesthesia during childbirth, there was no significant association with eating and drinking during labor and the rate of cesarean section, operative vaginal birth, or Apgar scores of less than 7 at 5 minutes.

Data Source: A Cochrane database review of five randomized controlled trials comprising 3,130 women.

Disclosures: The review was sponsored by the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Liverpool, as well as the National Institute for Health Research, and by a World Health Organization grant. One of the authors was the primary investigator on a study included in the review.

Women at low risk of complications during childbirth should be allowed to take food and water as they desire during active labor, a Cochrane database review has concluded.

“The review identified no benefits or harms of restricting foods and fluids during labor in women at low risk of needing anesthesia,” wrote lead author Mandisa Singata, R.N., and her associates. “Given these findings, women should be free to eat and drink in labor or not, as they wish” (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010;CD003930 [doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003930.pub2]).

The review of five studies comprising 3,130 women suggests that the prohibition on oral intake during labor may be based on outdated concerns, wrote Ms. Singata of the University of Witwatersrand, East London, South Africa, and her associates.

“Restricting oral food and fluid intake … is a strongly held obstetric and anesthetic tradition,” related to research performed in the 1940s on regurgitation under general anesthetic and resulting inhalation pneumonia. “Most [eating prohibitions] are based on historical, but important, concerns related to these risks. … The incidence is very rare with modern anesthetic techniques and the use of regional rather than general anesthesia.”

Ms. Singata and her colleagues identified five randomized controlled trials that examined this issue. The studies were conducted from 1999 to 2009.

All included women at low risk of requiring general anesthesia during childbirth. One study looked at restricting intake to ice chips and sips of water vs. full access to food and drink. Two compared water only to encouraging the consumption of some food and fluid, and two compared water only to carbohydrate drinks during labor.

The analysis was dominated by the largest and most recent study, which contained 2,443 women. The other four studies together comprised 687 women. The largest study was conducted in a “highly medicalized environment,” in which 30% of women had a cesarean section, over 50% had oxytocin, just under 70% received intravenous fluids and epidural anesthesia, and 27% underwent operative vaginal birth.

“In addition, 20% of the women in the water-only arm ate during labor and 295 in the food and fluid arm chose not to eat in labor. This clearly reflects the wide variation in women's wishes for food and fluids during labor,” the authors wrote.

When considering any restriction of food and fluid versus allowing them, the authors found no significant associations with the rate of cesarean section, operative vaginal birth, or Apgar scores of less than 7 at 5 minutes. Neither were there significant relationships with duration of labor, maternal nausea or vomiting, narcotic pain relief, or infant admission to intensive care.

None of the outcomes were significantly related in any of the other analyses: complete restriction of food and fluid vs. freedom to eat and drink, water only vs. freedom to eat and drink, or complete food and fluid restriction vs. carbohydrate-based fluid only.

Major Finding: In women at low risk of needing general anesthesia during childbirth, there was no significant association with eating and drinking during labor and the rate of cesarean section, operative vaginal birth, or Apgar scores of less than 7 at 5 minutes.

Data Source: A Cochrane database review of five randomized controlled trials comprising 3,130 women.

Disclosures: The review was sponsored by the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Liverpool, as well as the National Institute for Health Research, and by a World Health Organization grant. One of the authors was the primary investigator on a study included in the review.

Women at low risk of complications during childbirth should be allowed to take food and water as they desire during active labor, a Cochrane database review has concluded.

“The review identified no benefits or harms of restricting foods and fluids during labor in women at low risk of needing anesthesia,” wrote lead author Mandisa Singata, R.N., and her associates. “Given these findings, women should be free to eat and drink in labor or not, as they wish” (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010;CD003930 [doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003930.pub2]).

The review of five studies comprising 3,130 women suggests that the prohibition on oral intake during labor may be based on outdated concerns, wrote Ms. Singata of the University of Witwatersrand, East London, South Africa, and her associates.

“Restricting oral food and fluid intake … is a strongly held obstetric and anesthetic tradition,” related to research performed in the 1940s on regurgitation under general anesthetic and resulting inhalation pneumonia. “Most [eating prohibitions] are based on historical, but important, concerns related to these risks. … The incidence is very rare with modern anesthetic techniques and the use of regional rather than general anesthesia.”

Ms. Singata and her colleagues identified five randomized controlled trials that examined this issue. The studies were conducted from 1999 to 2009.

All included women at low risk of requiring general anesthesia during childbirth. One study looked at restricting intake to ice chips and sips of water vs. full access to food and drink. Two compared water only to encouraging the consumption of some food and fluid, and two compared water only to carbohydrate drinks during labor.

The analysis was dominated by the largest and most recent study, which contained 2,443 women. The other four studies together comprised 687 women. The largest study was conducted in a “highly medicalized environment,” in which 30% of women had a cesarean section, over 50% had oxytocin, just under 70% received intravenous fluids and epidural anesthesia, and 27% underwent operative vaginal birth.

“In addition, 20% of the women in the water-only arm ate during labor and 295 in the food and fluid arm chose not to eat in labor. This clearly reflects the wide variation in women's wishes for food and fluids during labor,” the authors wrote.

When considering any restriction of food and fluid versus allowing them, the authors found no significant associations with the rate of cesarean section, operative vaginal birth, or Apgar scores of less than 7 at 5 minutes. Neither were there significant relationships with duration of labor, maternal nausea or vomiting, narcotic pain relief, or infant admission to intensive care.

None of the outcomes were significantly related in any of the other analyses: complete restriction of food and fluid vs. freedom to eat and drink, water only vs. freedom to eat and drink, or complete food and fluid restriction vs. carbohydrate-based fluid only.

Slight Uptick Seen in Teen Pregnancy Rates : Increase unlikely to be due solely to increase in abstinence-only sex education, experts say.

Major Finding: The rates of teen pregnancy, birth, and abortion increased in 2006 after declining every year since 1990.

Data Source: Data compiled from national-level and state-level sources.

Disclosures: Preparation of the report was funded by the Brush Foundation, the California Wellness Foundation, and the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Teen pregnancy rates increased 3% in the United States in 2006 after declining every year since 1990, according to a report from the Guttmacher Institute.

In addition, teen births rose 4% and teen abortions rose 1% between 2005 and 2006, according to the report, which the institute compiled from a variety of national and state-level sources.

The teen pregnancy rate hit its peak in 1990, with 117 pregnancies per 1,000 women aged 15–19 years. By 2005 it had declined 40%, to 70/1,000. But in 2006, the rate increased to 72/1,000.

“After more than a decade of progress, this reversal is deeply troubling,” Heather Boonstra, a senior public policy associate at the Guttmacher Institute, said in a prepared statement. “It coincides with an increase in rigid abstinence-only-until-marriage programs, which received major funding boosts under the Bush administration. A strong body of research shows that these programs do not work. Fortunately, the heyday of this failed experiment has come to an end with the enactment of a new teen pregnancy prevention initiative that ensures that programs will be age appropriate, medically accurate, and, most importantly, based on research demonstrating their effectiveness.”

Two experts interviewed by this news organization weren't so sure that the increase in pregnancy rates could be attributed to abstinence-only sex education. “The temporal association between the increase in abstinence-only programs and the increase in the pregnancy rate definitely deserves closer attention,” said Dr. Lee Savio Beers, a pediatrician who is director of the healthy generations clinic at Children's National Medical Center, Washington, D.C. “I don't know that anyone knows for sure whether it's directly related, but the two kind of came together. It's such a multifactorial issue that we may never have an answer on that.”

Dr. Melissa Kottke, who is with the department of ob.gyn. at Emory University and is director of the Jane Fonda Center for Adolescent Reproductive Health, both in Atlanta, said, “I think there's going to be a lot of things contributing to [increases in teen pregnancy rates], and I don't think we're going to know what all of those are.”

Dr. Kottke listed some of the other possibilities: teenage sexual activity, poverty, the media, parenting, funding for care, and funding for family planning services. “All of those things are going to contribute,” she said, “and I don't think we're going to be able to point our finger at one thing or the other.”

About the Guttmacher Institute, Dr. Beers said, “They're a well-respected organization. Their policy views tend to be on the liberal side. But I think everyone pretty much agrees that their facts are good, and their numbers are good, and for pregnancy numbers, they're better than pretty much anyone.”

Although the long decline and recent uptick in teen pregnancy rates were seen in blacks, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic whites, there were some substantial racial and ethic differences (see box). Among black teens, the pregnancy rate declined by 45%, from 224/1,000 in 1990 to 123/1,000 in 2005, and then increased 2.4%, to 126/1,000 in 2006.

Among Hispanic teens, the pregnancy rate declined by 26%, from 170/1,000 in 1992 to 125/1,000 in 2005, and then increased 1% to 127/1,000 in 2006.

And among non-Hispanic whites, the rate declined by 51%, from 87/1,000 in 1990 to 43/1,000 in 2005, and then increased 2% to 44/1,000 in 2006.

State-level data were not available for 2006, but in 2005 the highest teen pregnancy rates were in New Mexico (93/1,000), Nevada (90/1,000), and Arizona (89/1,000). The lowest rates were in New Hampshire (33/1,000), Vermont (49/1,000), and Maine (48/1,000).

Although there has been a long decline in the teen pregnancy rate in the United States, even at their low point in 2005, the U.S teen pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates were still way above those for all other developed nations, Dr. Beers said.

And Dr. Kottke said that there's already evidence that the 1-year uptick is not a statistical fluke. She's seen preliminary data for 2007 indicating that the increase in teen pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates increased for a second year.

Physicians have a unique opportunity to help turn these numbers around, she said. “What we know is that young people still trust their physicians, and they look to their physicians for important education. Physicians who are serving young teens need to make sure they are an avenue for education, for care, and for confidentiality.”

The full report is available at www.guttmacher.org/pubs/USTPtrends.pdf

Vitals

Source Elsevier Global Medical News

Major Finding: The rates of teen pregnancy, birth, and abortion increased in 2006 after declining every year since 1990.

Data Source: Data compiled from national-level and state-level sources.

Disclosures: Preparation of the report was funded by the Brush Foundation, the California Wellness Foundation, and the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Teen pregnancy rates increased 3% in the United States in 2006 after declining every year since 1990, according to a report from the Guttmacher Institute.

In addition, teen births rose 4% and teen abortions rose 1% between 2005 and 2006, according to the report, which the institute compiled from a variety of national and state-level sources.

The teen pregnancy rate hit its peak in 1990, with 117 pregnancies per 1,000 women aged 15–19 years. By 2005 it had declined 40%, to 70/1,000. But in 2006, the rate increased to 72/1,000.

“After more than a decade of progress, this reversal is deeply troubling,” Heather Boonstra, a senior public policy associate at the Guttmacher Institute, said in a prepared statement. “It coincides with an increase in rigid abstinence-only-until-marriage programs, which received major funding boosts under the Bush administration. A strong body of research shows that these programs do not work. Fortunately, the heyday of this failed experiment has come to an end with the enactment of a new teen pregnancy prevention initiative that ensures that programs will be age appropriate, medically accurate, and, most importantly, based on research demonstrating their effectiveness.”

Two experts interviewed by this news organization weren't so sure that the increase in pregnancy rates could be attributed to abstinence-only sex education. “The temporal association between the increase in abstinence-only programs and the increase in the pregnancy rate definitely deserves closer attention,” said Dr. Lee Savio Beers, a pediatrician who is director of the healthy generations clinic at Children's National Medical Center, Washington, D.C. “I don't know that anyone knows for sure whether it's directly related, but the two kind of came together. It's such a multifactorial issue that we may never have an answer on that.”

Dr. Melissa Kottke, who is with the department of ob.gyn. at Emory University and is director of the Jane Fonda Center for Adolescent Reproductive Health, both in Atlanta, said, “I think there's going to be a lot of things contributing to [increases in teen pregnancy rates], and I don't think we're going to know what all of those are.”

Dr. Kottke listed some of the other possibilities: teenage sexual activity, poverty, the media, parenting, funding for care, and funding for family planning services. “All of those things are going to contribute,” she said, “and I don't think we're going to be able to point our finger at one thing or the other.”

About the Guttmacher Institute, Dr. Beers said, “They're a well-respected organization. Their policy views tend to be on the liberal side. But I think everyone pretty much agrees that their facts are good, and their numbers are good, and for pregnancy numbers, they're better than pretty much anyone.”

Although the long decline and recent uptick in teen pregnancy rates were seen in blacks, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic whites, there were some substantial racial and ethic differences (see box). Among black teens, the pregnancy rate declined by 45%, from 224/1,000 in 1990 to 123/1,000 in 2005, and then increased 2.4%, to 126/1,000 in 2006.

Among Hispanic teens, the pregnancy rate declined by 26%, from 170/1,000 in 1992 to 125/1,000 in 2005, and then increased 1% to 127/1,000 in 2006.

And among non-Hispanic whites, the rate declined by 51%, from 87/1,000 in 1990 to 43/1,000 in 2005, and then increased 2% to 44/1,000 in 2006.

State-level data were not available for 2006, but in 2005 the highest teen pregnancy rates were in New Mexico (93/1,000), Nevada (90/1,000), and Arizona (89/1,000). The lowest rates were in New Hampshire (33/1,000), Vermont (49/1,000), and Maine (48/1,000).

Although there has been a long decline in the teen pregnancy rate in the United States, even at their low point in 2005, the U.S teen pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates were still way above those for all other developed nations, Dr. Beers said.

And Dr. Kottke said that there's already evidence that the 1-year uptick is not a statistical fluke. She's seen preliminary data for 2007 indicating that the increase in teen pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates increased for a second year.

Physicians have a unique opportunity to help turn these numbers around, she said. “What we know is that young people still trust their physicians, and they look to their physicians for important education. Physicians who are serving young teens need to make sure they are an avenue for education, for care, and for confidentiality.”

The full report is available at www.guttmacher.org/pubs/USTPtrends.pdf

Vitals

Source Elsevier Global Medical News

Major Finding: The rates of teen pregnancy, birth, and abortion increased in 2006 after declining every year since 1990.

Data Source: Data compiled from national-level and state-level sources.

Disclosures: Preparation of the report was funded by the Brush Foundation, the California Wellness Foundation, and the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Teen pregnancy rates increased 3% in the United States in 2006 after declining every year since 1990, according to a report from the Guttmacher Institute.

In addition, teen births rose 4% and teen abortions rose 1% between 2005 and 2006, according to the report, which the institute compiled from a variety of national and state-level sources.

The teen pregnancy rate hit its peak in 1990, with 117 pregnancies per 1,000 women aged 15–19 years. By 2005 it had declined 40%, to 70/1,000. But in 2006, the rate increased to 72/1,000.

“After more than a decade of progress, this reversal is deeply troubling,” Heather Boonstra, a senior public policy associate at the Guttmacher Institute, said in a prepared statement. “It coincides with an increase in rigid abstinence-only-until-marriage programs, which received major funding boosts under the Bush administration. A strong body of research shows that these programs do not work. Fortunately, the heyday of this failed experiment has come to an end with the enactment of a new teen pregnancy prevention initiative that ensures that programs will be age appropriate, medically accurate, and, most importantly, based on research demonstrating their effectiveness.”

Two experts interviewed by this news organization weren't so sure that the increase in pregnancy rates could be attributed to abstinence-only sex education. “The temporal association between the increase in abstinence-only programs and the increase in the pregnancy rate definitely deserves closer attention,” said Dr. Lee Savio Beers, a pediatrician who is director of the healthy generations clinic at Children's National Medical Center, Washington, D.C. “I don't know that anyone knows for sure whether it's directly related, but the two kind of came together. It's such a multifactorial issue that we may never have an answer on that.”

Dr. Melissa Kottke, who is with the department of ob.gyn. at Emory University and is director of the Jane Fonda Center for Adolescent Reproductive Health, both in Atlanta, said, “I think there's going to be a lot of things contributing to [increases in teen pregnancy rates], and I don't think we're going to know what all of those are.”

Dr. Kottke listed some of the other possibilities: teenage sexual activity, poverty, the media, parenting, funding for care, and funding for family planning services. “All of those things are going to contribute,” she said, “and I don't think we're going to be able to point our finger at one thing or the other.”

About the Guttmacher Institute, Dr. Beers said, “They're a well-respected organization. Their policy views tend to be on the liberal side. But I think everyone pretty much agrees that their facts are good, and their numbers are good, and for pregnancy numbers, they're better than pretty much anyone.”

Although the long decline and recent uptick in teen pregnancy rates were seen in blacks, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic whites, there were some substantial racial and ethic differences (see box). Among black teens, the pregnancy rate declined by 45%, from 224/1,000 in 1990 to 123/1,000 in 2005, and then increased 2.4%, to 126/1,000 in 2006.

Among Hispanic teens, the pregnancy rate declined by 26%, from 170/1,000 in 1992 to 125/1,000 in 2005, and then increased 1% to 127/1,000 in 2006.

And among non-Hispanic whites, the rate declined by 51%, from 87/1,000 in 1990 to 43/1,000 in 2005, and then increased 2% to 44/1,000 in 2006.

State-level data were not available for 2006, but in 2005 the highest teen pregnancy rates were in New Mexico (93/1,000), Nevada (90/1,000), and Arizona (89/1,000). The lowest rates were in New Hampshire (33/1,000), Vermont (49/1,000), and Maine (48/1,000).

Although there has been a long decline in the teen pregnancy rate in the United States, even at their low point in 2005, the U.S teen pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates were still way above those for all other developed nations, Dr. Beers said.

And Dr. Kottke said that there's already evidence that the 1-year uptick is not a statistical fluke. She's seen preliminary data for 2007 indicating that the increase in teen pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates increased for a second year.

Physicians have a unique opportunity to help turn these numbers around, she said. “What we know is that young people still trust their physicians, and they look to their physicians for important education. Physicians who are serving young teens need to make sure they are an avenue for education, for care, and for confidentiality.”

The full report is available at www.guttmacher.org/pubs/USTPtrends.pdf

Vitals

Source Elsevier Global Medical News

Stillbirth: Preventable tragedy or a lethal “act of nature”?

Stillbirth late in pregnancy is a major obstetric tragedy. It traumatizes the mother, reverberates through the family for weeks, months, and, sometimes, painful years, and creates recurring waves of sadness, loneliness, anger, and wonder about a child who might have been.

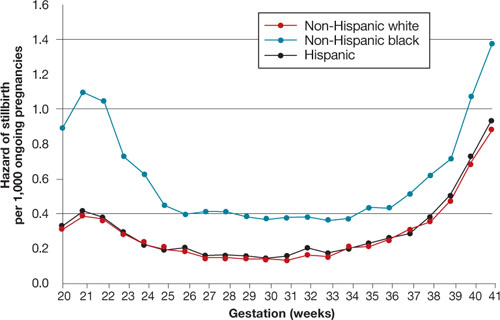

Stillbirth is often defined as fetal loss after 20 weeks of pregnancy (if gestational age is known). By that definition, there are about 6 stillbirths for every 1,000 total births in the United States. Over the past 20 years, the rate of early fetal loss (at 20 to 27 weeks’ gestation) has remained relatively stable, whereas the rate of late fetal loss (28 weeks and later) has decreased by about 30%—likely because of better obstetric care.

Yet much more can be—should be—done to prevent stillbirth because, in part, a substantial number of stillbirths occur after 37 weeks of pregnancy. Here is one standardized, inexpensive way that we can reduce late fetal loss.

Assessing fetal movement

The Cochrane Systematic Review on the assessment of fetal movement as an indicator of fetal well-being, which was updated in 2006, concluded that 1) available data were insufficient to influence practice and 2) robust research was needed in this area.1

In a recent study of more than 65,000 pregnancies, however, Tveit and coworkers reported that taking a standardized approach to a woman’s report of decreased fetal movement reduced the rate of late fetal loss by approximately 33%.2 The study was designed as a multicenter intervention comprising:

- 7 months of preintervention (baseline) data collection, followed by

- standardized changes in practice, and then

- 17 more months of data collection.

Those “changes in practice” included 1) a standardized approach to patient education on how a mother should assess, and respond to, what she perceives to be a decrease in fetal movement and 2) a guideline for clinicians on how to respond when a patient offers a chief complaint of decreased fetal movement.

The centerpiece of the study’s patient education intervention is a brochure that includes a kick chart and detailed advice to the mother about how to count kicks and respond to what she perceives to be a decrease in fetal movement. She is advised to never wait until the next day to contact a health-care provider when she thinks that fetal movement has decreased.

The clinical guideline used in the study recommends that clinicians obtain, from all women who report decreased fetal movement, a nonstress test (NST) and an obstetric sonogram to assess fetal movement, amniotic fluid volume, and fetal growth and anatomy.

Impact of the intervention

Here is what investigators found:

- Before the intervention, baseline late fetal loss rate for the entire pregnant population at the study sites was 3 for every 1,000 births; afterward, that rate fell to 2 for every 1,000.

- The intervention did not significantly increase the number of women who self-reported decreased fetal movement.

- Before the intervention, 6.3% of pregnant women reported decreased fetal movement; afterward, that rate was 6.6%.

- Among women who reported decreased fetal movement, the late fetal loss rate fell—from 4.2% at baseline to 2.4% after the intervention (P < .004).

- Among women who reported decreased fetal movement, the late fetal loss of a normally formed fetus decreased—from 3.9% to 2.2% (P < .005).

- Because of ultrasonography, antenatal detection of growth-restricted fetuses increased significantly after the intervention.

You can do a world of good by providing support for a woman who has just experienced stillbirth; in fact, such support, done well, is as important as the interventions you put in place to prevent fetal loss. Although few high-quality studies have yielded evidence that can guide your response, after the tragedy of a stillbirth, to a grieving mother and her family, two small-scale observational and qualitative studies1,2 recommend that you:

- reduce the woman’s perception of chaos and loss of control

- support an individualized approach to her interaction with, and separation from, the fetus

- support her grieving and be sensitive to its critical steps, including denial, isolation, anger, and depression

- provide her with a comprehensible explanation for the stillbirth

- develop a well-organized care pathway from diagnosis of the loss through to delivery or surgical termination and recovery

- provide opportunity for follow-up with her and her family as a way to offer closure.

What lesson can we take home?

In many birthing centers in the United States, the approach to decreased fetal movement isn’t standardized. Taking a standardized approach to patient education about fetal movement and having a standardized clinical response that includes NST and sonography—the cornerstones of the Tviet study—is likely to reduce the rate of late fetal loss.

This approach to testing has a serendipitous advantage: It isn’t associated with a massive increase in cost for additional testing.

Many hurdles ahead

The risk of late fetal loss is influenced by many variables, including:

- gestational length

- maternal age

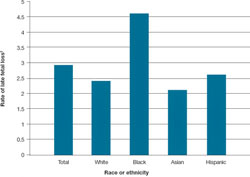

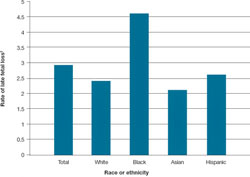

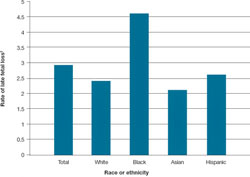

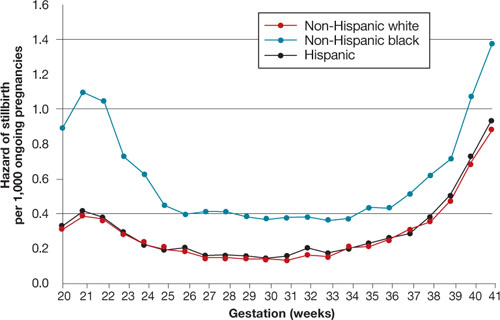

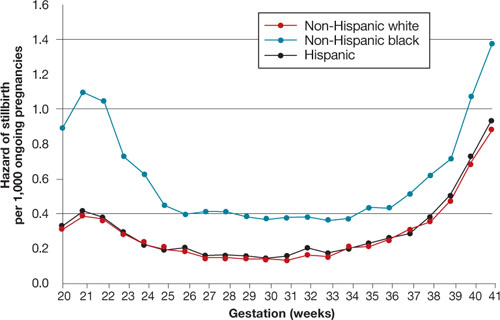

- race and ethnicity (see the FIGURE )

- parity

- level of education

- history of fetal loss

- numerous maternal and fetal diseases (e.g., maternal diabetes, hyperthyroidism, and hypertension; fetal growth restriction and congenital anomalies).

Key word: “Optimize.” The question of how to develop clinical algorithms that optimize pregnancy outcome by identifying an optimal upper limit of an optimal time for delivery hasn’t been answered because the matter hasn’t been exhaustively studied in randomized trials. It will be a challenge to validate such algorithms, because any strategy runs the risk of utilizing substantial health-care resources for modest clinical gain.3–5

Until sophisticated, multifactorial algorithms for identifying an optimal due date are developed, clinicians are left to select a few prominent variables to guide their recommendations—such as gestational length and maternal age. For a healthy woman, expectant management of pregnancy beyond 41 weeks is associated with an increase in the rates of stillbirth; meconium staining and meconium aspiration syndrome; and cesarean delivery. Based on these observations, many obstetricians routinely offer elective delivery to women who have reached 41 weeks’ gestation but have not begun spontaneous labor.6

As I noted, in addition to gestational age, such variables as the mother’s age and race influence optimal timing of delivery. Examples: For a woman 40 to 44 years old, delivery between 38 and 39 weeks’ gestation may be optimal to prevent stillbirth. For a woman 25 to 29 years old, it is likely safe to allow the pregnancy to progress to 41, possibly 42 weeks’ gestation before delivery.7

In addition, given the increased risk of stillbirth among black women ( FIGURE ), it might be reasonable to consider using race to 1) guide the decision to initiate fetal testing and 2) determine the optimal time for delivery.8,9

FIGURE Looking by race and ethnicity, blacks have the highest rate of late* fetal loss

*28 weeks or later.

† For every 1,000 (total) births beyond 20 weeks’ gestation.

Adapted from: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MacDorman MF, Kirmeyer S. Fetal and perinatal mortality, United States, 2005. Natl Vit Stat Rep. 2009;57:1–20.

4,000 fewer tragedies would be a blessing

With 4 million births annually in the United States, a late fetal loss rate of 3 for every 1,000 total births means 12,000 near-term stillbirths. Monitoring fetal movement, and responding promptly and in a standardized manner when it decreases, would reduce late fetal loss by 33%. That is 4,000 more live births, every year.

Look how a small shift in practice can bring a significant change in outcome—each one of those babies a precious gift to a mother and family!

1. Mangesi L, Hofmeyr GJ. Fetal movement counting for assessment of fetal wellbeing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD004909.-

2. Tveit JVH, Saastad E, Stray-Pedersen B, et al. Reduction of late stillbirth with the introduction of fetal movement information and guidelines—a clinical quality improvement. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:32.-

3. Nicholson JM, Parry S, Caughey AB, Rosen S, Keen A, Macones GA. The impact of the active management of risk in pregnancy at term on birth outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:511.e1-511.e15.

4. Klein MC. Preventive Labor Induction-AMORIPAT: much promise, not yet realized. Birth. 2009;36:83-85.

5. Fretts RC, Elkin EB, Myers ER, Heffner LJ. Should older women have antepartum testing to prevent unexplained stillbirth? Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:56-64.

6. Bahtiyar MO, Funai EF, Rosenberg V, et al. Stillbirth at term in women of advanced maternal age in the United States: when could the antenatal testing be initiated? Am J Perinatol. 2008;25:301-304.

7. Caughey AB, Sundaram V, Kaimal AJ, et al. Systematic review: elective induction of labor versus expectant management of pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:252-263.

8. Willinger M, Ko CW, Reddy UM. Racial disparities in stillbirth risk across gestation in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:469.e1-469.e8.

9. MacDorman MF, Kirmeyer S. Fetal and perinatal mortality, United States, 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;57:1-19.

Stillbirth late in pregnancy is a major obstetric tragedy. It traumatizes the mother, reverberates through the family for weeks, months, and, sometimes, painful years, and creates recurring waves of sadness, loneliness, anger, and wonder about a child who might have been.

Stillbirth is often defined as fetal loss after 20 weeks of pregnancy (if gestational age is known). By that definition, there are about 6 stillbirths for every 1,000 total births in the United States. Over the past 20 years, the rate of early fetal loss (at 20 to 27 weeks’ gestation) has remained relatively stable, whereas the rate of late fetal loss (28 weeks and later) has decreased by about 30%—likely because of better obstetric care.

Yet much more can be—should be—done to prevent stillbirth because, in part, a substantial number of stillbirths occur after 37 weeks of pregnancy. Here is one standardized, inexpensive way that we can reduce late fetal loss.

Assessing fetal movement

The Cochrane Systematic Review on the assessment of fetal movement as an indicator of fetal well-being, which was updated in 2006, concluded that 1) available data were insufficient to influence practice and 2) robust research was needed in this area.1

In a recent study of more than 65,000 pregnancies, however, Tveit and coworkers reported that taking a standardized approach to a woman’s report of decreased fetal movement reduced the rate of late fetal loss by approximately 33%.2 The study was designed as a multicenter intervention comprising:

- 7 months of preintervention (baseline) data collection, followed by

- standardized changes in practice, and then

- 17 more months of data collection.

Those “changes in practice” included 1) a standardized approach to patient education on how a mother should assess, and respond to, what she perceives to be a decrease in fetal movement and 2) a guideline for clinicians on how to respond when a patient offers a chief complaint of decreased fetal movement.

The centerpiece of the study’s patient education intervention is a brochure that includes a kick chart and detailed advice to the mother about how to count kicks and respond to what she perceives to be a decrease in fetal movement. She is advised to never wait until the next day to contact a health-care provider when she thinks that fetal movement has decreased.

The clinical guideline used in the study recommends that clinicians obtain, from all women who report decreased fetal movement, a nonstress test (NST) and an obstetric sonogram to assess fetal movement, amniotic fluid volume, and fetal growth and anatomy.

Impact of the intervention

Here is what investigators found:

- Before the intervention, baseline late fetal loss rate for the entire pregnant population at the study sites was 3 for every 1,000 births; afterward, that rate fell to 2 for every 1,000.

- The intervention did not significantly increase the number of women who self-reported decreased fetal movement.

- Before the intervention, 6.3% of pregnant women reported decreased fetal movement; afterward, that rate was 6.6%.

- Among women who reported decreased fetal movement, the late fetal loss rate fell—from 4.2% at baseline to 2.4% after the intervention (P < .004).

- Among women who reported decreased fetal movement, the late fetal loss of a normally formed fetus decreased—from 3.9% to 2.2% (P < .005).

- Because of ultrasonography, antenatal detection of growth-restricted fetuses increased significantly after the intervention.

You can do a world of good by providing support for a woman who has just experienced stillbirth; in fact, such support, done well, is as important as the interventions you put in place to prevent fetal loss. Although few high-quality studies have yielded evidence that can guide your response, after the tragedy of a stillbirth, to a grieving mother and her family, two small-scale observational and qualitative studies1,2 recommend that you:

- reduce the woman’s perception of chaos and loss of control

- support an individualized approach to her interaction with, and separation from, the fetus

- support her grieving and be sensitive to its critical steps, including denial, isolation, anger, and depression

- provide her with a comprehensible explanation for the stillbirth

- develop a well-organized care pathway from diagnosis of the loss through to delivery or surgical termination and recovery

- provide opportunity for follow-up with her and her family as a way to offer closure.

What lesson can we take home?

In many birthing centers in the United States, the approach to decreased fetal movement isn’t standardized. Taking a standardized approach to patient education about fetal movement and having a standardized clinical response that includes NST and sonography—the cornerstones of the Tviet study—is likely to reduce the rate of late fetal loss.

This approach to testing has a serendipitous advantage: It isn’t associated with a massive increase in cost for additional testing.

Many hurdles ahead

The risk of late fetal loss is influenced by many variables, including:

- gestational length

- maternal age

- race and ethnicity (see the FIGURE )

- parity

- level of education

- history of fetal loss

- numerous maternal and fetal diseases (e.g., maternal diabetes, hyperthyroidism, and hypertension; fetal growth restriction and congenital anomalies).

Key word: “Optimize.” The question of how to develop clinical algorithms that optimize pregnancy outcome by identifying an optimal upper limit of an optimal time for delivery hasn’t been answered because the matter hasn’t been exhaustively studied in randomized trials. It will be a challenge to validate such algorithms, because any strategy runs the risk of utilizing substantial health-care resources for modest clinical gain.3–5

Until sophisticated, multifactorial algorithms for identifying an optimal due date are developed, clinicians are left to select a few prominent variables to guide their recommendations—such as gestational length and maternal age. For a healthy woman, expectant management of pregnancy beyond 41 weeks is associated with an increase in the rates of stillbirth; meconium staining and meconium aspiration syndrome; and cesarean delivery. Based on these observations, many obstetricians routinely offer elective delivery to women who have reached 41 weeks’ gestation but have not begun spontaneous labor.6

As I noted, in addition to gestational age, such variables as the mother’s age and race influence optimal timing of delivery. Examples: For a woman 40 to 44 years old, delivery between 38 and 39 weeks’ gestation may be optimal to prevent stillbirth. For a woman 25 to 29 years old, it is likely safe to allow the pregnancy to progress to 41, possibly 42 weeks’ gestation before delivery.7

In addition, given the increased risk of stillbirth among black women ( FIGURE ), it might be reasonable to consider using race to 1) guide the decision to initiate fetal testing and 2) determine the optimal time for delivery.8,9

FIGURE Looking by race and ethnicity, blacks have the highest rate of late* fetal loss

*28 weeks or later.

† For every 1,000 (total) births beyond 20 weeks’ gestation.

Adapted from: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MacDorman MF, Kirmeyer S. Fetal and perinatal mortality, United States, 2005. Natl Vit Stat Rep. 2009;57:1–20.

4,000 fewer tragedies would be a blessing

With 4 million births annually in the United States, a late fetal loss rate of 3 for every 1,000 total births means 12,000 near-term stillbirths. Monitoring fetal movement, and responding promptly and in a standardized manner when it decreases, would reduce late fetal loss by 33%. That is 4,000 more live births, every year.

Look how a small shift in practice can bring a significant change in outcome—each one of those babies a precious gift to a mother and family!

Stillbirth late in pregnancy is a major obstetric tragedy. It traumatizes the mother, reverberates through the family for weeks, months, and, sometimes, painful years, and creates recurring waves of sadness, loneliness, anger, and wonder about a child who might have been.

Stillbirth is often defined as fetal loss after 20 weeks of pregnancy (if gestational age is known). By that definition, there are about 6 stillbirths for every 1,000 total births in the United States. Over the past 20 years, the rate of early fetal loss (at 20 to 27 weeks’ gestation) has remained relatively stable, whereas the rate of late fetal loss (28 weeks and later) has decreased by about 30%—likely because of better obstetric care.

Yet much more can be—should be—done to prevent stillbirth because, in part, a substantial number of stillbirths occur after 37 weeks of pregnancy. Here is one standardized, inexpensive way that we can reduce late fetal loss.

Assessing fetal movement

The Cochrane Systematic Review on the assessment of fetal movement as an indicator of fetal well-being, which was updated in 2006, concluded that 1) available data were insufficient to influence practice and 2) robust research was needed in this area.1

In a recent study of more than 65,000 pregnancies, however, Tveit and coworkers reported that taking a standardized approach to a woman’s report of decreased fetal movement reduced the rate of late fetal loss by approximately 33%.2 The study was designed as a multicenter intervention comprising:

- 7 months of preintervention (baseline) data collection, followed by

- standardized changes in practice, and then

- 17 more months of data collection.

Those “changes in practice” included 1) a standardized approach to patient education on how a mother should assess, and respond to, what she perceives to be a decrease in fetal movement and 2) a guideline for clinicians on how to respond when a patient offers a chief complaint of decreased fetal movement.

The centerpiece of the study’s patient education intervention is a brochure that includes a kick chart and detailed advice to the mother about how to count kicks and respond to what she perceives to be a decrease in fetal movement. She is advised to never wait until the next day to contact a health-care provider when she thinks that fetal movement has decreased.

The clinical guideline used in the study recommends that clinicians obtain, from all women who report decreased fetal movement, a nonstress test (NST) and an obstetric sonogram to assess fetal movement, amniotic fluid volume, and fetal growth and anatomy.

Impact of the intervention

Here is what investigators found:

- Before the intervention, baseline late fetal loss rate for the entire pregnant population at the study sites was 3 for every 1,000 births; afterward, that rate fell to 2 for every 1,000.

- The intervention did not significantly increase the number of women who self-reported decreased fetal movement.

- Before the intervention, 6.3% of pregnant women reported decreased fetal movement; afterward, that rate was 6.6%.

- Among women who reported decreased fetal movement, the late fetal loss rate fell—from 4.2% at baseline to 2.4% after the intervention (P < .004).

- Among women who reported decreased fetal movement, the late fetal loss of a normally formed fetus decreased—from 3.9% to 2.2% (P < .005).

- Because of ultrasonography, antenatal detection of growth-restricted fetuses increased significantly after the intervention.

You can do a world of good by providing support for a woman who has just experienced stillbirth; in fact, such support, done well, is as important as the interventions you put in place to prevent fetal loss. Although few high-quality studies have yielded evidence that can guide your response, after the tragedy of a stillbirth, to a grieving mother and her family, two small-scale observational and qualitative studies1,2 recommend that you:

- reduce the woman’s perception of chaos and loss of control

- support an individualized approach to her interaction with, and separation from, the fetus

- support her grieving and be sensitive to its critical steps, including denial, isolation, anger, and depression

- provide her with a comprehensible explanation for the stillbirth

- develop a well-organized care pathway from diagnosis of the loss through to delivery or surgical termination and recovery

- provide opportunity for follow-up with her and her family as a way to offer closure.

What lesson can we take home?

In many birthing centers in the United States, the approach to decreased fetal movement isn’t standardized. Taking a standardized approach to patient education about fetal movement and having a standardized clinical response that includes NST and sonography—the cornerstones of the Tviet study—is likely to reduce the rate of late fetal loss.

This approach to testing has a serendipitous advantage: It isn’t associated with a massive increase in cost for additional testing.

Many hurdles ahead

The risk of late fetal loss is influenced by many variables, including:

- gestational length

- maternal age

- race and ethnicity (see the FIGURE )

- parity

- level of education

- history of fetal loss

- numerous maternal and fetal diseases (e.g., maternal diabetes, hyperthyroidism, and hypertension; fetal growth restriction and congenital anomalies).

Key word: “Optimize.” The question of how to develop clinical algorithms that optimize pregnancy outcome by identifying an optimal upper limit of an optimal time for delivery hasn’t been answered because the matter hasn’t been exhaustively studied in randomized trials. It will be a challenge to validate such algorithms, because any strategy runs the risk of utilizing substantial health-care resources for modest clinical gain.3–5

Until sophisticated, multifactorial algorithms for identifying an optimal due date are developed, clinicians are left to select a few prominent variables to guide their recommendations—such as gestational length and maternal age. For a healthy woman, expectant management of pregnancy beyond 41 weeks is associated with an increase in the rates of stillbirth; meconium staining and meconium aspiration syndrome; and cesarean delivery. Based on these observations, many obstetricians routinely offer elective delivery to women who have reached 41 weeks’ gestation but have not begun spontaneous labor.6

As I noted, in addition to gestational age, such variables as the mother’s age and race influence optimal timing of delivery. Examples: For a woman 40 to 44 years old, delivery between 38 and 39 weeks’ gestation may be optimal to prevent stillbirth. For a woman 25 to 29 years old, it is likely safe to allow the pregnancy to progress to 41, possibly 42 weeks’ gestation before delivery.7

In addition, given the increased risk of stillbirth among black women ( FIGURE ), it might be reasonable to consider using race to 1) guide the decision to initiate fetal testing and 2) determine the optimal time for delivery.8,9

FIGURE Looking by race and ethnicity, blacks have the highest rate of late* fetal loss

*28 weeks or later.

† For every 1,000 (total) births beyond 20 weeks’ gestation.

Adapted from: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MacDorman MF, Kirmeyer S. Fetal and perinatal mortality, United States, 2005. Natl Vit Stat Rep. 2009;57:1–20.

4,000 fewer tragedies would be a blessing

With 4 million births annually in the United States, a late fetal loss rate of 3 for every 1,000 total births means 12,000 near-term stillbirths. Monitoring fetal movement, and responding promptly and in a standardized manner when it decreases, would reduce late fetal loss by 33%. That is 4,000 more live births, every year.

Look how a small shift in practice can bring a significant change in outcome—each one of those babies a precious gift to a mother and family!

1. Mangesi L, Hofmeyr GJ. Fetal movement counting for assessment of fetal wellbeing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD004909.-

2. Tveit JVH, Saastad E, Stray-Pedersen B, et al. Reduction of late stillbirth with the introduction of fetal movement information and guidelines—a clinical quality improvement. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:32.-

3. Nicholson JM, Parry S, Caughey AB, Rosen S, Keen A, Macones GA. The impact of the active management of risk in pregnancy at term on birth outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:511.e1-511.e15.

4. Klein MC. Preventive Labor Induction-AMORIPAT: much promise, not yet realized. Birth. 2009;36:83-85.

5. Fretts RC, Elkin EB, Myers ER, Heffner LJ. Should older women have antepartum testing to prevent unexplained stillbirth? Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:56-64.

6. Bahtiyar MO, Funai EF, Rosenberg V, et al. Stillbirth at term in women of advanced maternal age in the United States: when could the antenatal testing be initiated? Am J Perinatol. 2008;25:301-304.

7. Caughey AB, Sundaram V, Kaimal AJ, et al. Systematic review: elective induction of labor versus expectant management of pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:252-263.

8. Willinger M, Ko CW, Reddy UM. Racial disparities in stillbirth risk across gestation in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:469.e1-469.e8.

9. MacDorman MF, Kirmeyer S. Fetal and perinatal mortality, United States, 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;57:1-19.

1. Mangesi L, Hofmeyr GJ. Fetal movement counting for assessment of fetal wellbeing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD004909.-

2. Tveit JVH, Saastad E, Stray-Pedersen B, et al. Reduction of late stillbirth with the introduction of fetal movement information and guidelines—a clinical quality improvement. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:32.-

3. Nicholson JM, Parry S, Caughey AB, Rosen S, Keen A, Macones GA. The impact of the active management of risk in pregnancy at term on birth outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:511.e1-511.e15.

4. Klein MC. Preventive Labor Induction-AMORIPAT: much promise, not yet realized. Birth. 2009;36:83-85.

5. Fretts RC, Elkin EB, Myers ER, Heffner LJ. Should older women have antepartum testing to prevent unexplained stillbirth? Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:56-64.

6. Bahtiyar MO, Funai EF, Rosenberg V, et al. Stillbirth at term in women of advanced maternal age in the United States: when could the antenatal testing be initiated? Am J Perinatol. 2008;25:301-304.

7. Caughey AB, Sundaram V, Kaimal AJ, et al. Systematic review: elective induction of labor versus expectant management of pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:252-263.

8. Willinger M, Ko CW, Reddy UM. Racial disparities in stillbirth risk across gestation in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:469.e1-469.e8.

9. MacDorman MF, Kirmeyer S. Fetal and perinatal mortality, United States, 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;57:1-19.

IUGR Infants May Be at Risk for Atherosclerosis

Major Finding: Abdominal aortic intima media thickness was significantly greater in infants with IUGR than in controls, as was blood pressure, in one small study. In a second study of 59 IUGR fetuses, fetal ultrasonographic cardiovascular indices were significantly worse in the fetuses that died compared with survivors.

Data Source: The first study involved 25 infants with IUGR and 25 controls, while the second included 59 IUGR fetuses, in which the 8 fetuses that died were compared with survivors.

Disclosures: None reported.

HAMBURG, GERMANY — The environment experienced in utero was found in two small studies to influence the development of later cardiovascular disease and even perinatal death.

“We found that in fetuses and neonates with intrauterine growth restriction, aortic intima media wall thickness is increased with respect to controls, suggesting that it may represent an in utero marker of potential atherosclerosis development,” lead author Dr. Erich Cosmi said at the World Congress on Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Doppler ultrasound revealed that maximum abdominal aortic intima media thickness (aIMT) was significantly increased in 25 infants with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), compared with 25 controls, at a mean gestational age of 32 weeks (2.05 mm vs. 1.05 mm) and at a mean of 18 months after birth (2.3 mm vs. 1.06 mm).

Blood pressure values were also significantly correlated with prenatal and postnatal aIMT values, reported Dr. Cosmi of the department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Padua (Italy). Systolic blood pressure was 123 mm Hg in IUGR infants and 104 mm Hg in controls, which was significantly different at a P value of .0004.

When asked by the audience if any of the infants were on hypertension medication at the time of evaluation, Dr. Cosmi responded, “No, but they are now. We didn't know they would have hypertension. It was surprising for us.”

The researchers also assessed renal function after birth, as previous research in animal models suggests a renal contribution to developmentally programmed hypertension.

Compared with controls, IUGR infants had significantly higher urinary microalbumin (4.4 mg/L vs. 10.7 mg/L) and sodium (56 mmol/L vs. 122 mmol/L) levels and albumin/creatinine ratios (14.7 mg/g vs. 26.9 mg/g). All are markers of glomerular function.

Kidney length and volume were similar, as were levels of lysozyme, a marker of tubular function.

“The clinical implications of this study are that fetuses that were IUGR necessitate follow-up after birth, as they are at risk for cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Cosmi said in an interview.

Fetuses were classified as IUGR if their estimated fetal weight was below the 10th percentile with Doppler velocimetry greater than 2 standard deviations.

In a separate study presented during the same session, Dr. Elisenda Eixarchof the University of Barcelona reported that perinatal death in preterm IUGR fetuses is associated with the presence of markedly abnormal myocardial function before delivery and biomarkers of myocardial cell damage in cord blood.

Among 59 IUGR fetuses, the 8 fetuses who died as compared with survivors had significantly worse myocardial performance index z scores (2.5 vs. 1.7), left E/A (ratio of peak velocity during early diastolic filling to peak velocity during atrial contraction) z scores (2.4 vs. 0.8), and right E/A z scores (2.3 vs. 1). Only cardiac output was not significantly different at 816 mL/min per kilogram in those who died and 750 mL/min per kilogram in survivors.

Significant increases were also observed in fetuses who died versus survivors in B-type natriuretic peptide (350 pg/mL vs. 64 pg/mL), heart-type fatty acid–binding protein (23 mcg/L vs. 11 mcg/L), and troponin I levels (0.07 ng/mL vs. 0.02 ng/mL).

Major Finding: Abdominal aortic intima media thickness was significantly greater in infants with IUGR than in controls, as was blood pressure, in one small study. In a second study of 59 IUGR fetuses, fetal ultrasonographic cardiovascular indices were significantly worse in the fetuses that died compared with survivors.

Data Source: The first study involved 25 infants with IUGR and 25 controls, while the second included 59 IUGR fetuses, in which the 8 fetuses that died were compared with survivors.

Disclosures: None reported.

HAMBURG, GERMANY — The environment experienced in utero was found in two small studies to influence the development of later cardiovascular disease and even perinatal death.

“We found that in fetuses and neonates with intrauterine growth restriction, aortic intima media wall thickness is increased with respect to controls, suggesting that it may represent an in utero marker of potential atherosclerosis development,” lead author Dr. Erich Cosmi said at the World Congress on Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Doppler ultrasound revealed that maximum abdominal aortic intima media thickness (aIMT) was significantly increased in 25 infants with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), compared with 25 controls, at a mean gestational age of 32 weeks (2.05 mm vs. 1.05 mm) and at a mean of 18 months after birth (2.3 mm vs. 1.06 mm).

Blood pressure values were also significantly correlated with prenatal and postnatal aIMT values, reported Dr. Cosmi of the department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Padua (Italy). Systolic blood pressure was 123 mm Hg in IUGR infants and 104 mm Hg in controls, which was significantly different at a P value of .0004.

When asked by the audience if any of the infants were on hypertension medication at the time of evaluation, Dr. Cosmi responded, “No, but they are now. We didn't know they would have hypertension. It was surprising for us.”

The researchers also assessed renal function after birth, as previous research in animal models suggests a renal contribution to developmentally programmed hypertension.

Compared with controls, IUGR infants had significantly higher urinary microalbumin (4.4 mg/L vs. 10.7 mg/L) and sodium (56 mmol/L vs. 122 mmol/L) levels and albumin/creatinine ratios (14.7 mg/g vs. 26.9 mg/g). All are markers of glomerular function.

Kidney length and volume were similar, as were levels of lysozyme, a marker of tubular function.

“The clinical implications of this study are that fetuses that were IUGR necessitate follow-up after birth, as they are at risk for cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Cosmi said in an interview.

Fetuses were classified as IUGR if their estimated fetal weight was below the 10th percentile with Doppler velocimetry greater than 2 standard deviations.

In a separate study presented during the same session, Dr. Elisenda Eixarchof the University of Barcelona reported that perinatal death in preterm IUGR fetuses is associated with the presence of markedly abnormal myocardial function before delivery and biomarkers of myocardial cell damage in cord blood.

Among 59 IUGR fetuses, the 8 fetuses who died as compared with survivors had significantly worse myocardial performance index z scores (2.5 vs. 1.7), left E/A (ratio of peak velocity during early diastolic filling to peak velocity during atrial contraction) z scores (2.4 vs. 0.8), and right E/A z scores (2.3 vs. 1). Only cardiac output was not significantly different at 816 mL/min per kilogram in those who died and 750 mL/min per kilogram in survivors.

Significant increases were also observed in fetuses who died versus survivors in B-type natriuretic peptide (350 pg/mL vs. 64 pg/mL), heart-type fatty acid–binding protein (23 mcg/L vs. 11 mcg/L), and troponin I levels (0.07 ng/mL vs. 0.02 ng/mL).

Major Finding: Abdominal aortic intima media thickness was significantly greater in infants with IUGR than in controls, as was blood pressure, in one small study. In a second study of 59 IUGR fetuses, fetal ultrasonographic cardiovascular indices were significantly worse in the fetuses that died compared with survivors.

Data Source: The first study involved 25 infants with IUGR and 25 controls, while the second included 59 IUGR fetuses, in which the 8 fetuses that died were compared with survivors.

Disclosures: None reported.

HAMBURG, GERMANY — The environment experienced in utero was found in two small studies to influence the development of later cardiovascular disease and even perinatal death.

“We found that in fetuses and neonates with intrauterine growth restriction, aortic intima media wall thickness is increased with respect to controls, suggesting that it may represent an in utero marker of potential atherosclerosis development,” lead author Dr. Erich Cosmi said at the World Congress on Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Doppler ultrasound revealed that maximum abdominal aortic intima media thickness (aIMT) was significantly increased in 25 infants with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), compared with 25 controls, at a mean gestational age of 32 weeks (2.05 mm vs. 1.05 mm) and at a mean of 18 months after birth (2.3 mm vs. 1.06 mm).

Blood pressure values were also significantly correlated with prenatal and postnatal aIMT values, reported Dr. Cosmi of the department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Padua (Italy). Systolic blood pressure was 123 mm Hg in IUGR infants and 104 mm Hg in controls, which was significantly different at a P value of .0004.

When asked by the audience if any of the infants were on hypertension medication at the time of evaluation, Dr. Cosmi responded, “No, but they are now. We didn't know they would have hypertension. It was surprising for us.”

The researchers also assessed renal function after birth, as previous research in animal models suggests a renal contribution to developmentally programmed hypertension.

Compared with controls, IUGR infants had significantly higher urinary microalbumin (4.4 mg/L vs. 10.7 mg/L) and sodium (56 mmol/L vs. 122 mmol/L) levels and albumin/creatinine ratios (14.7 mg/g vs. 26.9 mg/g). All are markers of glomerular function.

Kidney length and volume were similar, as were levels of lysozyme, a marker of tubular function.

“The clinical implications of this study are that fetuses that were IUGR necessitate follow-up after birth, as they are at risk for cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Cosmi said in an interview.

Fetuses were classified as IUGR if their estimated fetal weight was below the 10th percentile with Doppler velocimetry greater than 2 standard deviations.

In a separate study presented during the same session, Dr. Elisenda Eixarchof the University of Barcelona reported that perinatal death in preterm IUGR fetuses is associated with the presence of markedly abnormal myocardial function before delivery and biomarkers of myocardial cell damage in cord blood.

Among 59 IUGR fetuses, the 8 fetuses who died as compared with survivors had significantly worse myocardial performance index z scores (2.5 vs. 1.7), left E/A (ratio of peak velocity during early diastolic filling to peak velocity during atrial contraction) z scores (2.4 vs. 0.8), and right E/A z scores (2.3 vs. 1). Only cardiac output was not significantly different at 816 mL/min per kilogram in those who died and 750 mL/min per kilogram in survivors.

Significant increases were also observed in fetuses who died versus survivors in B-type natriuretic peptide (350 pg/mL vs. 64 pg/mL), heart-type fatty acid–binding protein (23 mcg/L vs. 11 mcg/L), and troponin I levels (0.07 ng/mL vs. 0.02 ng/mL).

2009 H1N1 Maternal Deaths May Up Overall Rate

Major Finding: Of the six pregnant and two postpartum patients who died, six had underlying medical conditions. None had received antiviral medication within 48 hours after symptom onset.

Data Source: Data from 94 pregnant women, 8 postpartum women, and 137 nonpregnant women of reproductive age who were hospitalized with or died of 2009 H1N1 influenza.

Disclosures: None reported.

Maternal mortality from 2009 influenza H1N1 was estimated at 4.3/100,000 live births in California, based on the results of statewide surveillance.

The maternal mortality ratio—the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births—from any cause was 19.3 in California in 2005 and 13.3 in the United States in 2006. More than two-thirds of maternal deaths in the United States are directly related to obstetrical factors, and deaths from influenza had been rare prior to the 2009 influenza H1N1 outbreak, Dr. Janice K. Louieof the California Department of Public Health, Richmond, and her associates wrote (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:27-35).

Now, the high maternal death rate attributed to this flu has the potential to notably increase the overall maternal mortality rate in the United States for 2009, Dr. Louie and her associates said.

From April 23 through Aug. 11, 2009, data were reported for 94 pregnant women, 8 postpartum women, and 137 nonpregnant women of reproductive age who were hospitalized with or died of 2009 H1N1 influenza.

Of the 78 pregnant women whose race/ethnicity was known, 43 were Hispanic, 15 were white, 9 were Asian or Pacific Islander, 6 were non-Hispanic black, and 5 were “other.”

About one-third (32) of the 93 pregnant women for whom the data were available had underlying medical conditions that placed them at increased risk for influenza complications, as did a fourth (2) of the 8 postpartum women and two-thirds (82) of the 137 nonpregnant women. The most common condition was asthma, affecting 16% of the pregnant and 28% of the nonpregnant women.

The most commonly reported symptoms among pregnant patients were cough (93%), fever (91%), sore throat (41%), shortness of breath (41%), muscle aches (41%), and nausea or vomiting (33%).

Eighteen (19%) of the pregnant patients were admitted to intensive care, as were 4 of the 8 (50%) postpartum patients and 41 (30%) of the nonpregnant patients.

In some of the cases, reliance on rapid influenza tests appears to have contributed to treatment delays. Rapid influenza tests were falsely negative in 38% of the total 153 who were tested. Of those 58 patients, 28 (48%) were pregnant. Only 7 of the 25 (28%) pregnant women with falsely negative results for whom information was available received antiviral treatment within the recommended 48 hours after symptom onset. Five of the eight patients (63%) who died had false-negative rapid test results, Dr. Louie and her associates noted.

In all, while 81% of both pregnant and nonpregnant women received antiviral treatment, only half of the pregnant women and a third of the nonpregnant women received it within the recommended 48-hour time frame, the investigators reported.

Of the six pregnant and two postpartum patients who died, six had underlying medical conditions, including hypothyroidism in two, gestational diabetes in one, and a history of Hodgkin's disease in one. All eight required intensive care, and none had received antiviral medication within 48 hours after symptom onset.

The maternal mortality ratio was based on an estimated 188,383 births in the state of California from April 3 through Aug. 5. The eight deaths caused by 2009 H1N1 during that time resulted in a cause-specific maternal mortality ratio of 4.3, they said.

Major Finding: Of the six pregnant and two postpartum patients who died, six had underlying medical conditions. None had received antiviral medication within 48 hours after symptom onset.

Data Source: Data from 94 pregnant women, 8 postpartum women, and 137 nonpregnant women of reproductive age who were hospitalized with or died of 2009 H1N1 influenza.

Disclosures: None reported.

Maternal mortality from 2009 influenza H1N1 was estimated at 4.3/100,000 live births in California, based on the results of statewide surveillance.

The maternal mortality ratio—the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births—from any cause was 19.3 in California in 2005 and 13.3 in the United States in 2006. More than two-thirds of maternal deaths in the United States are directly related to obstetrical factors, and deaths from influenza had been rare prior to the 2009 influenza H1N1 outbreak, Dr. Janice K. Louieof the California Department of Public Health, Richmond, and her associates wrote (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:27-35).

Now, the high maternal death rate attributed to this flu has the potential to notably increase the overall maternal mortality rate in the United States for 2009, Dr. Louie and her associates said.

From April 23 through Aug. 11, 2009, data were reported for 94 pregnant women, 8 postpartum women, and 137 nonpregnant women of reproductive age who were hospitalized with or died of 2009 H1N1 influenza.

Of the 78 pregnant women whose race/ethnicity was known, 43 were Hispanic, 15 were white, 9 were Asian or Pacific Islander, 6 were non-Hispanic black, and 5 were “other.”

About one-third (32) of the 93 pregnant women for whom the data were available had underlying medical conditions that placed them at increased risk for influenza complications, as did a fourth (2) of the 8 postpartum women and two-thirds (82) of the 137 nonpregnant women. The most common condition was asthma, affecting 16% of the pregnant and 28% of the nonpregnant women.

The most commonly reported symptoms among pregnant patients were cough (93%), fever (91%), sore throat (41%), shortness of breath (41%), muscle aches (41%), and nausea or vomiting (33%).

Eighteen (19%) of the pregnant patients were admitted to intensive care, as were 4 of the 8 (50%) postpartum patients and 41 (30%) of the nonpregnant patients.

In some of the cases, reliance on rapid influenza tests appears to have contributed to treatment delays. Rapid influenza tests were falsely negative in 38% of the total 153 who were tested. Of those 58 patients, 28 (48%) were pregnant. Only 7 of the 25 (28%) pregnant women with falsely negative results for whom information was available received antiviral treatment within the recommended 48 hours after symptom onset. Five of the eight patients (63%) who died had false-negative rapid test results, Dr. Louie and her associates noted.

In all, while 81% of both pregnant and nonpregnant women received antiviral treatment, only half of the pregnant women and a third of the nonpregnant women received it within the recommended 48-hour time frame, the investigators reported.

Of the six pregnant and two postpartum patients who died, six had underlying medical conditions, including hypothyroidism in two, gestational diabetes in one, and a history of Hodgkin's disease in one. All eight required intensive care, and none had received antiviral medication within 48 hours after symptom onset.

The maternal mortality ratio was based on an estimated 188,383 births in the state of California from April 3 through Aug. 5. The eight deaths caused by 2009 H1N1 during that time resulted in a cause-specific maternal mortality ratio of 4.3, they said.

Major Finding: Of the six pregnant and two postpartum patients who died, six had underlying medical conditions. None had received antiviral medication within 48 hours after symptom onset.

Data Source: Data from 94 pregnant women, 8 postpartum women, and 137 nonpregnant women of reproductive age who were hospitalized with or died of 2009 H1N1 influenza.

Disclosures: None reported.

Maternal mortality from 2009 influenza H1N1 was estimated at 4.3/100,000 live births in California, based on the results of statewide surveillance.

The maternal mortality ratio—the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births—from any cause was 19.3 in California in 2005 and 13.3 in the United States in 2006. More than two-thirds of maternal deaths in the United States are directly related to obstetrical factors, and deaths from influenza had been rare prior to the 2009 influenza H1N1 outbreak, Dr. Janice K. Louieof the California Department of Public Health, Richmond, and her associates wrote (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:27-35).

Now, the high maternal death rate attributed to this flu has the potential to notably increase the overall maternal mortality rate in the United States for 2009, Dr. Louie and her associates said.

From April 23 through Aug. 11, 2009, data were reported for 94 pregnant women, 8 postpartum women, and 137 nonpregnant women of reproductive age who were hospitalized with or died of 2009 H1N1 influenza.

Of the 78 pregnant women whose race/ethnicity was known, 43 were Hispanic, 15 were white, 9 were Asian or Pacific Islander, 6 were non-Hispanic black, and 5 were “other.”

About one-third (32) of the 93 pregnant women for whom the data were available had underlying medical conditions that placed them at increased risk for influenza complications, as did a fourth (2) of the 8 postpartum women and two-thirds (82) of the 137 nonpregnant women. The most common condition was asthma, affecting 16% of the pregnant and 28% of the nonpregnant women.

The most commonly reported symptoms among pregnant patients were cough (93%), fever (91%), sore throat (41%), shortness of breath (41%), muscle aches (41%), and nausea or vomiting (33%).

Eighteen (19%) of the pregnant patients were admitted to intensive care, as were 4 of the 8 (50%) postpartum patients and 41 (30%) of the nonpregnant patients.

In some of the cases, reliance on rapid influenza tests appears to have contributed to treatment delays. Rapid influenza tests were falsely negative in 38% of the total 153 who were tested. Of those 58 patients, 28 (48%) were pregnant. Only 7 of the 25 (28%) pregnant women with falsely negative results for whom information was available received antiviral treatment within the recommended 48 hours after symptom onset. Five of the eight patients (63%) who died had false-negative rapid test results, Dr. Louie and her associates noted.

In all, while 81% of both pregnant and nonpregnant women received antiviral treatment, only half of the pregnant women and a third of the nonpregnant women received it within the recommended 48-hour time frame, the investigators reported.

Of the six pregnant and two postpartum patients who died, six had underlying medical conditions, including hypothyroidism in two, gestational diabetes in one, and a history of Hodgkin's disease in one. All eight required intensive care, and none had received antiviral medication within 48 hours after symptom onset.

The maternal mortality ratio was based on an estimated 188,383 births in the state of California from April 3 through Aug. 5. The eight deaths caused by 2009 H1N1 during that time resulted in a cause-specific maternal mortality ratio of 4.3, they said.

Misoprostol vs. Oxytocin For Postpartum Bleeding

Major Finding: Oral misoprostol may be an alternative to intravenous oxytocin for controlling postpartum hemorrhage.

Data Source: Efficacy of oral misoprostol as an alternative to intravenous oxytocin was studied in 978 women in four hospitals in one trial, and in another 809 women who had received prophylactic oxytocin during the third stage of labor in five hospitals in a second trial.

Disclosures: Both studies were funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Dr. Winikoff and Ms. Blum said they had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Oral misoprostol may be as effective as intravenous oxytocin for controlling postpartum hemorrhage, based on data from two studies. Both studies involved an off-label use of misoprostol, and each study included more than 800 women.

Oxytocin is the drug of choice for postpartum bleeding, but misoprostol may be more feasible in areas with limited resources, said Dr. Beverly Winikoff of Gynuity Health Projects in New York City and her colleagues.