User login

EC approves drug for acquired hemophilia A

Photo courtesy of

Baxter International Inc.

The European Commission (EC) has approved a recombinant porcine factor VIII (FVIII) product, Obizur, to treat bleeding episodes in adults with acquired hemophilia A caused by autoantibodies to FVIII.

Obizur is the first recombinant porcine treatment to be made available for acquired hemophilia A in Europe.

It is specifically designed so physicians can monitor treatment response by measuring FVIII activity levels in addition to making clinical assessments.

The EC’s approval is based on a phase 2/3 trial in which patients with acquired hemophilia A received Obizur as treatment for serious bleeding episodes.

Twenty-nine patients were enrolled in this trial and evaluated for safety. Twenty-eight patients were evaluated for efficacy, as researchers determined that one of the patients did not actually have acquired hemophilia A.

At 24 hours after the initial infusion, all 28 patients in the efficacy analysis had a positive response to Obizur. This meant that bleeding stopped or decreased, the patients experienced clinical stabilization or improvement, and FVIII levels were 20% or higher.

Eighty-six percent of patients (24/28) had successful treatment of their initial bleeding episode. The overall treatment success was determined by the investigator based on the ability to discontinue or reduce the dose and/or dosing frequency of Obizur.

The adverse event most frequently reported in the 29 patients in the safety analysis was the development of inhibitors to porcine FVIII.

Nineteen patients were negative for anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, and 5 of these patients (26%) developed anti-porcine FVIII antibodies following exposure to Obizur.

Of the 10 patients with detectable anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, 2 (20%) experienced an increase in titer, and 8 (80%) decreased to a non-detectable titer.

Obizur is under development by Baxalta Incorporated. The drug is approved for use in the US and Canada as well as the European Union. It is under regulatory review in Switzerland, Australia, and Colombia. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

Baxter International Inc.

The European Commission (EC) has approved a recombinant porcine factor VIII (FVIII) product, Obizur, to treat bleeding episodes in adults with acquired hemophilia A caused by autoantibodies to FVIII.

Obizur is the first recombinant porcine treatment to be made available for acquired hemophilia A in Europe.

It is specifically designed so physicians can monitor treatment response by measuring FVIII activity levels in addition to making clinical assessments.

The EC’s approval is based on a phase 2/3 trial in which patients with acquired hemophilia A received Obizur as treatment for serious bleeding episodes.

Twenty-nine patients were enrolled in this trial and evaluated for safety. Twenty-eight patients were evaluated for efficacy, as researchers determined that one of the patients did not actually have acquired hemophilia A.

At 24 hours after the initial infusion, all 28 patients in the efficacy analysis had a positive response to Obizur. This meant that bleeding stopped or decreased, the patients experienced clinical stabilization or improvement, and FVIII levels were 20% or higher.

Eighty-six percent of patients (24/28) had successful treatment of their initial bleeding episode. The overall treatment success was determined by the investigator based on the ability to discontinue or reduce the dose and/or dosing frequency of Obizur.

The adverse event most frequently reported in the 29 patients in the safety analysis was the development of inhibitors to porcine FVIII.

Nineteen patients were negative for anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, and 5 of these patients (26%) developed anti-porcine FVIII antibodies following exposure to Obizur.

Of the 10 patients with detectable anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, 2 (20%) experienced an increase in titer, and 8 (80%) decreased to a non-detectable titer.

Obizur is under development by Baxalta Incorporated. The drug is approved for use in the US and Canada as well as the European Union. It is under regulatory review in Switzerland, Australia, and Colombia. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

Baxter International Inc.

The European Commission (EC) has approved a recombinant porcine factor VIII (FVIII) product, Obizur, to treat bleeding episodes in adults with acquired hemophilia A caused by autoantibodies to FVIII.

Obizur is the first recombinant porcine treatment to be made available for acquired hemophilia A in Europe.

It is specifically designed so physicians can monitor treatment response by measuring FVIII activity levels in addition to making clinical assessments.

The EC’s approval is based on a phase 2/3 trial in which patients with acquired hemophilia A received Obizur as treatment for serious bleeding episodes.

Twenty-nine patients were enrolled in this trial and evaluated for safety. Twenty-eight patients were evaluated for efficacy, as researchers determined that one of the patients did not actually have acquired hemophilia A.

At 24 hours after the initial infusion, all 28 patients in the efficacy analysis had a positive response to Obizur. This meant that bleeding stopped or decreased, the patients experienced clinical stabilization or improvement, and FVIII levels were 20% or higher.

Eighty-six percent of patients (24/28) had successful treatment of their initial bleeding episode. The overall treatment success was determined by the investigator based on the ability to discontinue or reduce the dose and/or dosing frequency of Obizur.

The adverse event most frequently reported in the 29 patients in the safety analysis was the development of inhibitors to porcine FVIII.

Nineteen patients were negative for anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, and 5 of these patients (26%) developed anti-porcine FVIII antibodies following exposure to Obizur.

Of the 10 patients with detectable anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, 2 (20%) experienced an increase in titer, and 8 (80%) decreased to a non-detectable titer.

Obizur is under development by Baxalta Incorporated. The drug is approved for use in the US and Canada as well as the European Union. It is under regulatory review in Switzerland, Australia, and Colombia. ![]()

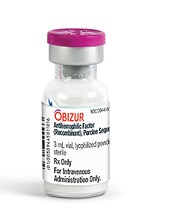

Role of cyclins in malaria parasite development

Photo by James Gathany

Researchers say they have characterized the cyclin protein family in the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei.

The team found there are only 3 cyclins in this parasite, but one of these, the single P-type cyclin CYC3, plays a “vital role” in parasite development in the mosquito.

The researchers believe this work, published in PLoS Pathogens, could pave the way to a better understanding of malaria parasites and lead to potential new treatments.

“This first functional study of cyclin in the malaria parasite and its consequences in parasite development within pathogen-carrying mosquitoes will definitely further our understanding of parasite cell division, which I hope will lead to the elimination of this disease in the future,” said study author Magali Roques, PhD, of the University of Nottingham in the UK. ![]()

Photo by James Gathany

Researchers say they have characterized the cyclin protein family in the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei.

The team found there are only 3 cyclins in this parasite, but one of these, the single P-type cyclin CYC3, plays a “vital role” in parasite development in the mosquito.

The researchers believe this work, published in PLoS Pathogens, could pave the way to a better understanding of malaria parasites and lead to potential new treatments.

“This first functional study of cyclin in the malaria parasite and its consequences in parasite development within pathogen-carrying mosquitoes will definitely further our understanding of parasite cell division, which I hope will lead to the elimination of this disease in the future,” said study author Magali Roques, PhD, of the University of Nottingham in the UK. ![]()

Photo by James Gathany

Researchers say they have characterized the cyclin protein family in the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei.

The team found there are only 3 cyclins in this parasite, but one of these, the single P-type cyclin CYC3, plays a “vital role” in parasite development in the mosquito.

The researchers believe this work, published in PLoS Pathogens, could pave the way to a better understanding of malaria parasites and lead to potential new treatments.

“This first functional study of cyclin in the malaria parasite and its consequences in parasite development within pathogen-carrying mosquitoes will definitely further our understanding of parasite cell division, which I hope will lead to the elimination of this disease in the future,” said study author Magali Roques, PhD, of the University of Nottingham in the UK. ![]()

Pharma companies fail to disclose trial information

Photo by Esther Dyson

New research indicates that pharmaceutical companies are still failing to disclose trial information publicly, despite efforts made over the last several years to increase transparency.

Investigators examined publicly available information for 15 drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012.

They found that two-thirds of clinical trials per drug were disclosed publicly, which is below legal standards.

In an attempt to fix this problem, the investigators developed the “Good Pharma Scorecard,” which ranks companies according to their adherence to transparency practices.

Jennifer Miller, PhD, of NYU Langone Medical Center in New York, New York, and her colleagues described the scorecard and reported their research results in BMJ Open.

“Selectively disclosing trial information can distort the medical evidence and challenge the abilities of physicians, prescription guideline writers, payers, and formulary decision-makers to recommend and provide the right drugs for the right patients,” Dr Miller said.

She also noted that selectively disclosing information violates the rights of human research subjects laid out in the US Common Rule, a rule of ethics that requires that human-subject experiments have the potential to contribute to generalizable knowledge.

Study details

Dr Miller and her colleagues examined publicly available information for all drugs approved by the FDA in 2012 that were sponsored by the 20 pharmaceutical companies with the highest market value.

The information was gathered from a variety of publicly available documents, including Drugs@FDA, ClinicalTrials.gov, and journals indexed in Medline.

From this information, the team identified 15 drugs from 10 companies with more than 318 associated clinical trials involving 99,599 research subjects.

Almost half of all the drugs reviewed had at least 1 undisclosed phase 2 or 3 trial. A median of 57% of trials per drug were properly registered, 20% of final results were reported on ClinicalTrials.gov, and 56% of trials were published in academic journals.

A median of 65% of trial results were publicly available—either on ClinicalTrials.gov or in the medical literature. But the investigators found “considerable variation” between companies.

Per drug, a median of 17% of trials were subject to public disclosure by the 2007 US Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA). Of these trials, a median of 67% were FDAAA-compliant.

A majority of the research subjects—68%—participated in trials subject to the FDAAA, and 51% of these subjects were enrolled in trials that were noncompliant with the act.

Good Pharma Scorecard

Dr Miller and her colleagues believe they have devised a solution to help fix the transparency problem—the Good Pharma Scorecard.

The scorecard ranks drug sponsors according to 5 elements of transparency:

- Trial registration

- Results reporting

- Publication of trial data in a medical journal

- Compliance with legal disclosure requirements

- Adherence with the ethics standards enshrined in the Common Rule.

“The scorecard and rankings have the potential to benefit consumers by helping assure the integrity and completeness of clinical trial information,” Dr Miller said. “Full transparency of clinical trials would also strengthen the protection of human research subjects by avoiding their unknowing recruitment into already failed experiments.”

The pilot rankings on the Good Pharma Scorecard score the largest pharmaceutical companies for drugs approved by the FDA in 2012.

But Dr Miller and her team plan to publish this scorecard annually, ranking each new group of FDA-approved drugs going forward. A ranking of drugs approved in 2015 and their sponsors is scheduled to be released in 2016. ![]()

Photo by Esther Dyson

New research indicates that pharmaceutical companies are still failing to disclose trial information publicly, despite efforts made over the last several years to increase transparency.

Investigators examined publicly available information for 15 drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012.

They found that two-thirds of clinical trials per drug were disclosed publicly, which is below legal standards.

In an attempt to fix this problem, the investigators developed the “Good Pharma Scorecard,” which ranks companies according to their adherence to transparency practices.

Jennifer Miller, PhD, of NYU Langone Medical Center in New York, New York, and her colleagues described the scorecard and reported their research results in BMJ Open.

“Selectively disclosing trial information can distort the medical evidence and challenge the abilities of physicians, prescription guideline writers, payers, and formulary decision-makers to recommend and provide the right drugs for the right patients,” Dr Miller said.

She also noted that selectively disclosing information violates the rights of human research subjects laid out in the US Common Rule, a rule of ethics that requires that human-subject experiments have the potential to contribute to generalizable knowledge.

Study details

Dr Miller and her colleagues examined publicly available information for all drugs approved by the FDA in 2012 that were sponsored by the 20 pharmaceutical companies with the highest market value.

The information was gathered from a variety of publicly available documents, including Drugs@FDA, ClinicalTrials.gov, and journals indexed in Medline.

From this information, the team identified 15 drugs from 10 companies with more than 318 associated clinical trials involving 99,599 research subjects.

Almost half of all the drugs reviewed had at least 1 undisclosed phase 2 or 3 trial. A median of 57% of trials per drug were properly registered, 20% of final results were reported on ClinicalTrials.gov, and 56% of trials were published in academic journals.

A median of 65% of trial results were publicly available—either on ClinicalTrials.gov or in the medical literature. But the investigators found “considerable variation” between companies.

Per drug, a median of 17% of trials were subject to public disclosure by the 2007 US Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA). Of these trials, a median of 67% were FDAAA-compliant.

A majority of the research subjects—68%—participated in trials subject to the FDAAA, and 51% of these subjects were enrolled in trials that were noncompliant with the act.

Good Pharma Scorecard

Dr Miller and her colleagues believe they have devised a solution to help fix the transparency problem—the Good Pharma Scorecard.

The scorecard ranks drug sponsors according to 5 elements of transparency:

- Trial registration

- Results reporting

- Publication of trial data in a medical journal

- Compliance with legal disclosure requirements

- Adherence with the ethics standards enshrined in the Common Rule.

“The scorecard and rankings have the potential to benefit consumers by helping assure the integrity and completeness of clinical trial information,” Dr Miller said. “Full transparency of clinical trials would also strengthen the protection of human research subjects by avoiding their unknowing recruitment into already failed experiments.”

The pilot rankings on the Good Pharma Scorecard score the largest pharmaceutical companies for drugs approved by the FDA in 2012.

But Dr Miller and her team plan to publish this scorecard annually, ranking each new group of FDA-approved drugs going forward. A ranking of drugs approved in 2015 and their sponsors is scheduled to be released in 2016. ![]()

Photo by Esther Dyson

New research indicates that pharmaceutical companies are still failing to disclose trial information publicly, despite efforts made over the last several years to increase transparency.

Investigators examined publicly available information for 15 drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012.

They found that two-thirds of clinical trials per drug were disclosed publicly, which is below legal standards.

In an attempt to fix this problem, the investigators developed the “Good Pharma Scorecard,” which ranks companies according to their adherence to transparency practices.

Jennifer Miller, PhD, of NYU Langone Medical Center in New York, New York, and her colleagues described the scorecard and reported their research results in BMJ Open.

“Selectively disclosing trial information can distort the medical evidence and challenge the abilities of physicians, prescription guideline writers, payers, and formulary decision-makers to recommend and provide the right drugs for the right patients,” Dr Miller said.

She also noted that selectively disclosing information violates the rights of human research subjects laid out in the US Common Rule, a rule of ethics that requires that human-subject experiments have the potential to contribute to generalizable knowledge.

Study details

Dr Miller and her colleagues examined publicly available information for all drugs approved by the FDA in 2012 that were sponsored by the 20 pharmaceutical companies with the highest market value.

The information was gathered from a variety of publicly available documents, including Drugs@FDA, ClinicalTrials.gov, and journals indexed in Medline.

From this information, the team identified 15 drugs from 10 companies with more than 318 associated clinical trials involving 99,599 research subjects.

Almost half of all the drugs reviewed had at least 1 undisclosed phase 2 or 3 trial. A median of 57% of trials per drug were properly registered, 20% of final results were reported on ClinicalTrials.gov, and 56% of trials were published in academic journals.

A median of 65% of trial results were publicly available—either on ClinicalTrials.gov or in the medical literature. But the investigators found “considerable variation” between companies.

Per drug, a median of 17% of trials were subject to public disclosure by the 2007 US Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA). Of these trials, a median of 67% were FDAAA-compliant.

A majority of the research subjects—68%—participated in trials subject to the FDAAA, and 51% of these subjects were enrolled in trials that were noncompliant with the act.

Good Pharma Scorecard

Dr Miller and her colleagues believe they have devised a solution to help fix the transparency problem—the Good Pharma Scorecard.

The scorecard ranks drug sponsors according to 5 elements of transparency:

- Trial registration

- Results reporting

- Publication of trial data in a medical journal

- Compliance with legal disclosure requirements

- Adherence with the ethics standards enshrined in the Common Rule.

“The scorecard and rankings have the potential to benefit consumers by helping assure the integrity and completeness of clinical trial information,” Dr Miller said. “Full transparency of clinical trials would also strengthen the protection of human research subjects by avoiding their unknowing recruitment into already failed experiments.”

The pilot rankings on the Good Pharma Scorecard score the largest pharmaceutical companies for drugs approved by the FDA in 2012.

But Dr Miller and her team plan to publish this scorecard annually, ranking each new group of FDA-approved drugs going forward. A ranking of drugs approved in 2015 and their sponsors is scheduled to be released in 2016. ![]()

Findings may help advance treatment of malaria

infecting a red blood cell

Image courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Researchers have found that a screening model can classify antimalarial drugs and reveal drug targets for Plasmodium falciparum, according to a paper published in Scientific Reports.

The team performed chemogenomic profiling of P falciparum for the first time.

They used a collection of malaria parasite mutants that each had altered metabolism linked to a defect in a single P falciparum gene.

They then screened 53 drugs and compounds against 71 of these P falciparum piggyBac single-insertion mutant parasites.

Computational analysis of the response patterns linked the different antimalarial drug candidates and metabolic inhibitors to the specific gene defect.

This revealed new insights into the drugs’ mechanism of action and uncovered 6 new genes that were involved in P falciparum’s response to artemisinin but were associated with increased susceptibility to the drugs tested.

“That represents 6 new targets potentially as effective as artemisinin for killing the malaria parasite,” said study author Dennis Kyle, PhD, of the University of South Florida in Tampa.

“There is definitely a sense of urgency for discovering new antimalarial drugs that may replace artemisinin, or work better with artemisinin, to prevent or delay drug resistance.”

P falciparum, which is becoming increasingly resistant to artemisinin, causes three-quarters of all malaria cases in Africa and 95% of malaria deaths worldwide. ![]()

infecting a red blood cell

Image courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Researchers have found that a screening model can classify antimalarial drugs and reveal drug targets for Plasmodium falciparum, according to a paper published in Scientific Reports.

The team performed chemogenomic profiling of P falciparum for the first time.

They used a collection of malaria parasite mutants that each had altered metabolism linked to a defect in a single P falciparum gene.

They then screened 53 drugs and compounds against 71 of these P falciparum piggyBac single-insertion mutant parasites.

Computational analysis of the response patterns linked the different antimalarial drug candidates and metabolic inhibitors to the specific gene defect.

This revealed new insights into the drugs’ mechanism of action and uncovered 6 new genes that were involved in P falciparum’s response to artemisinin but were associated with increased susceptibility to the drugs tested.

“That represents 6 new targets potentially as effective as artemisinin for killing the malaria parasite,” said study author Dennis Kyle, PhD, of the University of South Florida in Tampa.

“There is definitely a sense of urgency for discovering new antimalarial drugs that may replace artemisinin, or work better with artemisinin, to prevent or delay drug resistance.”

P falciparum, which is becoming increasingly resistant to artemisinin, causes three-quarters of all malaria cases in Africa and 95% of malaria deaths worldwide. ![]()

infecting a red blood cell

Image courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Researchers have found that a screening model can classify antimalarial drugs and reveal drug targets for Plasmodium falciparum, according to a paper published in Scientific Reports.

The team performed chemogenomic profiling of P falciparum for the first time.

They used a collection of malaria parasite mutants that each had altered metabolism linked to a defect in a single P falciparum gene.

They then screened 53 drugs and compounds against 71 of these P falciparum piggyBac single-insertion mutant parasites.

Computational analysis of the response patterns linked the different antimalarial drug candidates and metabolic inhibitors to the specific gene defect.

This revealed new insights into the drugs’ mechanism of action and uncovered 6 new genes that were involved in P falciparum’s response to artemisinin but were associated with increased susceptibility to the drugs tested.

“That represents 6 new targets potentially as effective as artemisinin for killing the malaria parasite,” said study author Dennis Kyle, PhD, of the University of South Florida in Tampa.

“There is definitely a sense of urgency for discovering new antimalarial drugs that may replace artemisinin, or work better with artemisinin, to prevent or delay drug resistance.”

P falciparum, which is becoming increasingly resistant to artemisinin, causes three-quarters of all malaria cases in Africa and 95% of malaria deaths worldwide. ![]()

Relapses ‘critical’ for sustained malaria transmission

Plasmodium vivax

Image by Mae Melvin

New research indicates that most childhood malaria infections in Papua New Guinea (PNG) are the result of relapsed, not new, infections.

The data suggest that, among children ages 5 to 10 living in a malaria-hyperendemic region of PNG, relapses cause about 4 of every 5 Plasmodium vivax infections and 3 of every 5 Plasmodium ovale infections.

Investigators therefore concluded that relapses are important for sustaining malaria transmission in PNG.

The team reported their findings in PLOS Medicine.

“Our research has shown that one of the biggest problems in realizing malaria eradication is relapsing P vivax infections, which are critical for sustained transmission in the region,” said study author Leanne Robinson, PhD, of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Parkville, Victoria, Australia.

“P vivax parasites are able to hide in the liver for long periods of time before ‘reawakening’ to cause disease and continue the transmission cycle. Mass drug administration that includes a drug that kills parasites in the liver is likely to be a highly effective strategy for eliminating malaria in PNG.”

To investigate this possibility, Dr Robinson and her colleagues analyzed 524 children, ages 5 to 10, living in a region of PNG where Plasmodium falciparum and P vivax are hyperendemic.

Roughly half the children (n=261) received an antimalarial treatment regimen that targets both blood-stage and liver-stage parasites (3 days of chloroquine, 3 days of artemether-lumefantrine, and 20 days of primaquine).

The other half (n=263) received antimalarial treatment targeting only blood-stage parasites (3 days of chloroquine, 3 days of artemether-lumefantrine, and 20 days of placebo).

The subjects were followed for 8 months. Compared to children in the placebo arm, those in the primaquine arm had a reduced risk of having at least 1 P vivax or P ovale infection during the follow-up period. The hazard ratio was 0.18 for P vivax (P<0.001) and 0.31 for P ovale (P=0.011).

“Children treated with drugs that targeted the liver and blood stages of infection had 80% fewer malaria infections than those treated with drugs that only targeted the blood stage of infection,” Dr Robinson said.

Children in the primaquine arm also had a reduced risk of having at least 1 clinical P vivax episode. The hazard ratio was 0.25 (P=0.002).

In addition, primaquine reduced the molecular force of P vivax blood-stage infection in the first 3 months of follow-up. The incidence rate ratio was 0.21 (P<0.001).

And children who received primaquine were less likely to carry P vivax gametocytes than children who received placebo, with an incidence rate ratio of 0.27 (P<0.001).

To build upon these findings, the investigators fed the trial data into a mathematical transmission model.

The model predicted that a mass drug administration program using blood-stage treatment alone would have only a transient effect on P vivax transmission levels. But a mass drug administration program that includes blood- and liver-stage treatment would be an effective strategy for P vivax elimination.

“We need a better way of identifying children who are chronically infected with malaria so that they can be treated,” said study author Ivo Mueller, PhD, of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

“It is the only way to stop the malaria transmission cycle in PNG and is likely to be the case for eliminating malaria in other parts of the Asia-Pacific and Americas.”

Dr Mueller and an international team of collaborators are currently developing a test that identifies people with dormant malaria parasites in their liver. ![]()

Plasmodium vivax

Image by Mae Melvin

New research indicates that most childhood malaria infections in Papua New Guinea (PNG) are the result of relapsed, not new, infections.

The data suggest that, among children ages 5 to 10 living in a malaria-hyperendemic region of PNG, relapses cause about 4 of every 5 Plasmodium vivax infections and 3 of every 5 Plasmodium ovale infections.

Investigators therefore concluded that relapses are important for sustaining malaria transmission in PNG.

The team reported their findings in PLOS Medicine.

“Our research has shown that one of the biggest problems in realizing malaria eradication is relapsing P vivax infections, which are critical for sustained transmission in the region,” said study author Leanne Robinson, PhD, of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Parkville, Victoria, Australia.

“P vivax parasites are able to hide in the liver for long periods of time before ‘reawakening’ to cause disease and continue the transmission cycle. Mass drug administration that includes a drug that kills parasites in the liver is likely to be a highly effective strategy for eliminating malaria in PNG.”

To investigate this possibility, Dr Robinson and her colleagues analyzed 524 children, ages 5 to 10, living in a region of PNG where Plasmodium falciparum and P vivax are hyperendemic.

Roughly half the children (n=261) received an antimalarial treatment regimen that targets both blood-stage and liver-stage parasites (3 days of chloroquine, 3 days of artemether-lumefantrine, and 20 days of primaquine).

The other half (n=263) received antimalarial treatment targeting only blood-stage parasites (3 days of chloroquine, 3 days of artemether-lumefantrine, and 20 days of placebo).

The subjects were followed for 8 months. Compared to children in the placebo arm, those in the primaquine arm had a reduced risk of having at least 1 P vivax or P ovale infection during the follow-up period. The hazard ratio was 0.18 for P vivax (P<0.001) and 0.31 for P ovale (P=0.011).

“Children treated with drugs that targeted the liver and blood stages of infection had 80% fewer malaria infections than those treated with drugs that only targeted the blood stage of infection,” Dr Robinson said.

Children in the primaquine arm also had a reduced risk of having at least 1 clinical P vivax episode. The hazard ratio was 0.25 (P=0.002).

In addition, primaquine reduced the molecular force of P vivax blood-stage infection in the first 3 months of follow-up. The incidence rate ratio was 0.21 (P<0.001).

And children who received primaquine were less likely to carry P vivax gametocytes than children who received placebo, with an incidence rate ratio of 0.27 (P<0.001).

To build upon these findings, the investigators fed the trial data into a mathematical transmission model.

The model predicted that a mass drug administration program using blood-stage treatment alone would have only a transient effect on P vivax transmission levels. But a mass drug administration program that includes blood- and liver-stage treatment would be an effective strategy for P vivax elimination.

“We need a better way of identifying children who are chronically infected with malaria so that they can be treated,” said study author Ivo Mueller, PhD, of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

“It is the only way to stop the malaria transmission cycle in PNG and is likely to be the case for eliminating malaria in other parts of the Asia-Pacific and Americas.”

Dr Mueller and an international team of collaborators are currently developing a test that identifies people with dormant malaria parasites in their liver. ![]()

Plasmodium vivax

Image by Mae Melvin

New research indicates that most childhood malaria infections in Papua New Guinea (PNG) are the result of relapsed, not new, infections.

The data suggest that, among children ages 5 to 10 living in a malaria-hyperendemic region of PNG, relapses cause about 4 of every 5 Plasmodium vivax infections and 3 of every 5 Plasmodium ovale infections.

Investigators therefore concluded that relapses are important for sustaining malaria transmission in PNG.

The team reported their findings in PLOS Medicine.

“Our research has shown that one of the biggest problems in realizing malaria eradication is relapsing P vivax infections, which are critical for sustained transmission in the region,” said study author Leanne Robinson, PhD, of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Parkville, Victoria, Australia.

“P vivax parasites are able to hide in the liver for long periods of time before ‘reawakening’ to cause disease and continue the transmission cycle. Mass drug administration that includes a drug that kills parasites in the liver is likely to be a highly effective strategy for eliminating malaria in PNG.”

To investigate this possibility, Dr Robinson and her colleagues analyzed 524 children, ages 5 to 10, living in a region of PNG where Plasmodium falciparum and P vivax are hyperendemic.

Roughly half the children (n=261) received an antimalarial treatment regimen that targets both blood-stage and liver-stage parasites (3 days of chloroquine, 3 days of artemether-lumefantrine, and 20 days of primaquine).

The other half (n=263) received antimalarial treatment targeting only blood-stage parasites (3 days of chloroquine, 3 days of artemether-lumefantrine, and 20 days of placebo).

The subjects were followed for 8 months. Compared to children in the placebo arm, those in the primaquine arm had a reduced risk of having at least 1 P vivax or P ovale infection during the follow-up period. The hazard ratio was 0.18 for P vivax (P<0.001) and 0.31 for P ovale (P=0.011).

“Children treated with drugs that targeted the liver and blood stages of infection had 80% fewer malaria infections than those treated with drugs that only targeted the blood stage of infection,” Dr Robinson said.

Children in the primaquine arm also had a reduced risk of having at least 1 clinical P vivax episode. The hazard ratio was 0.25 (P=0.002).

In addition, primaquine reduced the molecular force of P vivax blood-stage infection in the first 3 months of follow-up. The incidence rate ratio was 0.21 (P<0.001).

And children who received primaquine were less likely to carry P vivax gametocytes than children who received placebo, with an incidence rate ratio of 0.27 (P<0.001).

To build upon these findings, the investigators fed the trial data into a mathematical transmission model.

The model predicted that a mass drug administration program using blood-stage treatment alone would have only a transient effect on P vivax transmission levels. But a mass drug administration program that includes blood- and liver-stage treatment would be an effective strategy for P vivax elimination.

“We need a better way of identifying children who are chronically infected with malaria so that they can be treated,” said study author Ivo Mueller, PhD, of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

“It is the only way to stop the malaria transmission cycle in PNG and is likely to be the case for eliminating malaria in other parts of the Asia-Pacific and Americas.”

Dr Mueller and an international team of collaborators are currently developing a test that identifies people with dormant malaria parasites in their liver. ![]()

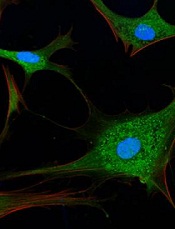

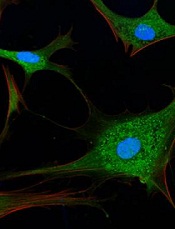

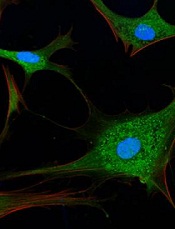

Team describes new way to edit HSPCs

Image by Tom Ellenberger

Researchers say they have discovered a more efficient way to edit the genomes of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).

The approach involves adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype 6 and zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) messenger RNA (mRNA).

Combining these delivery techniques allowed the team to “achieve high levels of precise genome editing” in HSPCs, including the most primitive cell population.

Paula Cannon, PhD, of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, and her colleagues described this work in Nature Biotechnology.

The researchers have been using ZFNs to cut a cell’s DNA at a precise location or sequence. The cell normally uses a copy of the cut DNA sequence as a template to repair the DNA break.

During this process, there is the opportunity to introduce new DNA sequences or to repair mutations, effectively fooling the cell into making a genetic edit.

To provide the cell with both the targeted nuclease and the new DNA template, researchers can use a variety of delivery vehicles or vectors, including viruses and mRNA.

With this study, Dr Cannon and her colleagues found they could deliver the DNA repair template using AAV6, which can naturally enter HSPCs.

At the same time, they found that delivering the ZFNs as short-lived mRNA molecules allowed the DNA cutting and repair process to occur without disrupting the HSPCs.

By combining these delivery methods, the researchers were able to insert a gene at a precise site in even the most primitive human HSPCs, with efficiency rates ranging from 17% to 43%.

The team then transplanted these edited HSPCs into immune-deficient mice and found the cells thrived and differentiated into many different blood cell types, all of which retained the edits to their DNA.

“Our results provide a strategy for broadening the application of genome editing technologies in HSPCs,” said study author Michael C. Holmes, PhD, vice president of research at Sangamo BioSciences in Richmond, California.

“This significantly advances our progress towards applying genome editing to the treatment of human diseases of the blood and immune systems.” ![]()

Image by Tom Ellenberger

Researchers say they have discovered a more efficient way to edit the genomes of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).

The approach involves adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype 6 and zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) messenger RNA (mRNA).

Combining these delivery techniques allowed the team to “achieve high levels of precise genome editing” in HSPCs, including the most primitive cell population.

Paula Cannon, PhD, of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, and her colleagues described this work in Nature Biotechnology.

The researchers have been using ZFNs to cut a cell’s DNA at a precise location or sequence. The cell normally uses a copy of the cut DNA sequence as a template to repair the DNA break.

During this process, there is the opportunity to introduce new DNA sequences or to repair mutations, effectively fooling the cell into making a genetic edit.

To provide the cell with both the targeted nuclease and the new DNA template, researchers can use a variety of delivery vehicles or vectors, including viruses and mRNA.

With this study, Dr Cannon and her colleagues found they could deliver the DNA repair template using AAV6, which can naturally enter HSPCs.

At the same time, they found that delivering the ZFNs as short-lived mRNA molecules allowed the DNA cutting and repair process to occur without disrupting the HSPCs.

By combining these delivery methods, the researchers were able to insert a gene at a precise site in even the most primitive human HSPCs, with efficiency rates ranging from 17% to 43%.

The team then transplanted these edited HSPCs into immune-deficient mice and found the cells thrived and differentiated into many different blood cell types, all of which retained the edits to their DNA.

“Our results provide a strategy for broadening the application of genome editing technologies in HSPCs,” said study author Michael C. Holmes, PhD, vice president of research at Sangamo BioSciences in Richmond, California.

“This significantly advances our progress towards applying genome editing to the treatment of human diseases of the blood and immune systems.” ![]()

Image by Tom Ellenberger

Researchers say they have discovered a more efficient way to edit the genomes of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).

The approach involves adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype 6 and zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) messenger RNA (mRNA).

Combining these delivery techniques allowed the team to “achieve high levels of precise genome editing” in HSPCs, including the most primitive cell population.

Paula Cannon, PhD, of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, and her colleagues described this work in Nature Biotechnology.

The researchers have been using ZFNs to cut a cell’s DNA at a precise location or sequence. The cell normally uses a copy of the cut DNA sequence as a template to repair the DNA break.

During this process, there is the opportunity to introduce new DNA sequences or to repair mutations, effectively fooling the cell into making a genetic edit.

To provide the cell with both the targeted nuclease and the new DNA template, researchers can use a variety of delivery vehicles or vectors, including viruses and mRNA.

With this study, Dr Cannon and her colleagues found they could deliver the DNA repair template using AAV6, which can naturally enter HSPCs.

At the same time, they found that delivering the ZFNs as short-lived mRNA molecules allowed the DNA cutting and repair process to occur without disrupting the HSPCs.

By combining these delivery methods, the researchers were able to insert a gene at a precise site in even the most primitive human HSPCs, with efficiency rates ranging from 17% to 43%.

The team then transplanted these edited HSPCs into immune-deficient mice and found the cells thrived and differentiated into many different blood cell types, all of which retained the edits to their DNA.

“Our results provide a strategy for broadening the application of genome editing technologies in HSPCs,” said study author Michael C. Holmes, PhD, vice president of research at Sangamo BioSciences in Richmond, California.

“This significantly advances our progress towards applying genome editing to the treatment of human diseases of the blood and immune systems.” ![]()

Models predict impact of malaria vaccine candidate

Photo by Caitlin Kleiboer

The malaria vaccine candidate RTS,S/AS01 (Mosquirix) could have a significant impact on public health in a range of settings across sub-Saharan Africa, according to mathematical models.

Researchers found that, over a 15-year time horizon, an average of 116,500 cases of clinical malaria and 484 malaria deaths would be averted for every 100,000 children vaccinated under a 4-dose schedule of immunizations at 6, 7.5, 9, and 27 months of age.

This translates to approximately 1.2 malaria cases averted per vaccinated child and 1 malaria death averted for every 200 children vaccinated.

These data apply to children living in regions of Africa that experience moderate to high malaria transmission—countries where prevalence rates for the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum range from 10% to 65%—and assumes a vaccine coverage rate at the fourth dose of approximately 70%.

The findings, published in The Lancet, contribute to the scientific evidence being considered by the World Health Organization, which is assessing the vaccine candidate for use in Africa.

“We took a realistic look at expected coverage of the RTS,S vaccine in a variety of African settings and found it would have significant impact on malaria disease in all but the lowest malaria transmission regions,” said Melissa Penny, PhD, of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute in Basel.

“Our numbers indicate that 6% to 29% of malaria deaths in children younger than age 5 could potentially be averted by the vaccine in the areas in which it is implemented, when used alongside other malaria control interventions.”

This is the first modeling study to use final, site-specific results of the RTS,S phase 3 safety and efficacy trial coordinated by GlaxoSmithKline and conducted at 11 sites in 7 African countries. And it accounts for implementation of the vaccine alongside use of long-lasting, insecticide-treated bed nets.

There was consensus across the predictions from all 4 groups that took part in the study. The participating institutions are Imperial College London in the UK, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, the Institute for Disease Modeling in the US, and GlaxoSmithKline in Belgium.

According to the study authors, public health authorities require these types of impact estimates on malaria disease and deaths to inform vaccine implementation.

Models can account for differences between the trial and real-life settings in transmission levels and healthcare accessibility, as well as predict RTS,S’s impact on malaria mortality, which was not possible to assess in the trial.

Cost-effectiveness

As part of the modeling study, the researchers considered a range of possible prices for RTS,S, from $2 to $10. They found that, compared to current malaria interventions, the vaccine would be cost-effective to implement under an assumed price of USD$5 per dose in areas of moderate and high malaria transmission.

”The cost-effectiveness of RTS,S is similar to what we’ve seen for other recently introduced childhood vaccines,” said Azra Ghani, PhD, of Imperial College London.

“It also overlaps within the ranges of cost-effectiveness of other malaria control interventions like bed nets and indoor residual sprays. However, it is important that the vaccine is introduced in addition to these other highly cost-effective interventions.”

The researchers measured cost-effectiveness in terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), a metric used by health economists to compare the impacts of health interventions in populations over time. One DALY is equivalent to 1 lost year of healthy life. The lower the amount spent per DALY averted, the greater the cost-effectiveness of an intervention.

With the vaccine priced at $5 per dose, the researchers estimated a median cost of $87 per DALY averted for a 4-dose vaccine schedule across the range of transmission settings with parasite prevalence 10% to 65%.

This cost was estimated to vary depending on the level of malaria transmission found in a particular location—with the vaccine being increasingly cost-effective in areas with a higher malaria burden.

The researchers noted that, according to earlier studies, the cost per DALY averted for other malaria interventions indicate averages of $27 for long-lasting, insecticide-treated bed nets; $143 for indoor residual spraying; and $24 for intermittent preventative treatment.

Caveats

The researchers conceded that this study has its limitations. One is the remaining uncertainty regarding the vaccine’s efficacy after the 4 years of follow-up observed in the phase 3 trial.

The team also noted that, since the phase 3 trial of RTS,S was not large enough to test for a reduction in deaths from malaria (versus reduction in incidence of malaria cases) and the quality of care provided to participants was high, the modeling studies’ projection of deaths requires further validation during the implementation phase.

“It will be important to continue to track the long-term impact of this vaccine to ensure that the effectiveness predicted by the models is borne out in practice,” said Caitlin Bever, PhD, of the Institute for Disease Modeling in Bellevue, Washington. ![]()

Photo by Caitlin Kleiboer

The malaria vaccine candidate RTS,S/AS01 (Mosquirix) could have a significant impact on public health in a range of settings across sub-Saharan Africa, according to mathematical models.

Researchers found that, over a 15-year time horizon, an average of 116,500 cases of clinical malaria and 484 malaria deaths would be averted for every 100,000 children vaccinated under a 4-dose schedule of immunizations at 6, 7.5, 9, and 27 months of age.

This translates to approximately 1.2 malaria cases averted per vaccinated child and 1 malaria death averted for every 200 children vaccinated.

These data apply to children living in regions of Africa that experience moderate to high malaria transmission—countries where prevalence rates for the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum range from 10% to 65%—and assumes a vaccine coverage rate at the fourth dose of approximately 70%.

The findings, published in The Lancet, contribute to the scientific evidence being considered by the World Health Organization, which is assessing the vaccine candidate for use in Africa.

“We took a realistic look at expected coverage of the RTS,S vaccine in a variety of African settings and found it would have significant impact on malaria disease in all but the lowest malaria transmission regions,” said Melissa Penny, PhD, of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute in Basel.

“Our numbers indicate that 6% to 29% of malaria deaths in children younger than age 5 could potentially be averted by the vaccine in the areas in which it is implemented, when used alongside other malaria control interventions.”

This is the first modeling study to use final, site-specific results of the RTS,S phase 3 safety and efficacy trial coordinated by GlaxoSmithKline and conducted at 11 sites in 7 African countries. And it accounts for implementation of the vaccine alongside use of long-lasting, insecticide-treated bed nets.

There was consensus across the predictions from all 4 groups that took part in the study. The participating institutions are Imperial College London in the UK, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, the Institute for Disease Modeling in the US, and GlaxoSmithKline in Belgium.

According to the study authors, public health authorities require these types of impact estimates on malaria disease and deaths to inform vaccine implementation.

Models can account for differences between the trial and real-life settings in transmission levels and healthcare accessibility, as well as predict RTS,S’s impact on malaria mortality, which was not possible to assess in the trial.

Cost-effectiveness

As part of the modeling study, the researchers considered a range of possible prices for RTS,S, from $2 to $10. They found that, compared to current malaria interventions, the vaccine would be cost-effective to implement under an assumed price of USD$5 per dose in areas of moderate and high malaria transmission.

”The cost-effectiveness of RTS,S is similar to what we’ve seen for other recently introduced childhood vaccines,” said Azra Ghani, PhD, of Imperial College London.

“It also overlaps within the ranges of cost-effectiveness of other malaria control interventions like bed nets and indoor residual sprays. However, it is important that the vaccine is introduced in addition to these other highly cost-effective interventions.”

The researchers measured cost-effectiveness in terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), a metric used by health economists to compare the impacts of health interventions in populations over time. One DALY is equivalent to 1 lost year of healthy life. The lower the amount spent per DALY averted, the greater the cost-effectiveness of an intervention.

With the vaccine priced at $5 per dose, the researchers estimated a median cost of $87 per DALY averted for a 4-dose vaccine schedule across the range of transmission settings with parasite prevalence 10% to 65%.

This cost was estimated to vary depending on the level of malaria transmission found in a particular location—with the vaccine being increasingly cost-effective in areas with a higher malaria burden.

The researchers noted that, according to earlier studies, the cost per DALY averted for other malaria interventions indicate averages of $27 for long-lasting, insecticide-treated bed nets; $143 for indoor residual spraying; and $24 for intermittent preventative treatment.

Caveats

The researchers conceded that this study has its limitations. One is the remaining uncertainty regarding the vaccine’s efficacy after the 4 years of follow-up observed in the phase 3 trial.

The team also noted that, since the phase 3 trial of RTS,S was not large enough to test for a reduction in deaths from malaria (versus reduction in incidence of malaria cases) and the quality of care provided to participants was high, the modeling studies’ projection of deaths requires further validation during the implementation phase.

“It will be important to continue to track the long-term impact of this vaccine to ensure that the effectiveness predicted by the models is borne out in practice,” said Caitlin Bever, PhD, of the Institute for Disease Modeling in Bellevue, Washington. ![]()

Photo by Caitlin Kleiboer

The malaria vaccine candidate RTS,S/AS01 (Mosquirix) could have a significant impact on public health in a range of settings across sub-Saharan Africa, according to mathematical models.

Researchers found that, over a 15-year time horizon, an average of 116,500 cases of clinical malaria and 484 malaria deaths would be averted for every 100,000 children vaccinated under a 4-dose schedule of immunizations at 6, 7.5, 9, and 27 months of age.

This translates to approximately 1.2 malaria cases averted per vaccinated child and 1 malaria death averted for every 200 children vaccinated.

These data apply to children living in regions of Africa that experience moderate to high malaria transmission—countries where prevalence rates for the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum range from 10% to 65%—and assumes a vaccine coverage rate at the fourth dose of approximately 70%.

The findings, published in The Lancet, contribute to the scientific evidence being considered by the World Health Organization, which is assessing the vaccine candidate for use in Africa.

“We took a realistic look at expected coverage of the RTS,S vaccine in a variety of African settings and found it would have significant impact on malaria disease in all but the lowest malaria transmission regions,” said Melissa Penny, PhD, of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute in Basel.

“Our numbers indicate that 6% to 29% of malaria deaths in children younger than age 5 could potentially be averted by the vaccine in the areas in which it is implemented, when used alongside other malaria control interventions.”

This is the first modeling study to use final, site-specific results of the RTS,S phase 3 safety and efficacy trial coordinated by GlaxoSmithKline and conducted at 11 sites in 7 African countries. And it accounts for implementation of the vaccine alongside use of long-lasting, insecticide-treated bed nets.

There was consensus across the predictions from all 4 groups that took part in the study. The participating institutions are Imperial College London in the UK, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, the Institute for Disease Modeling in the US, and GlaxoSmithKline in Belgium.

According to the study authors, public health authorities require these types of impact estimates on malaria disease and deaths to inform vaccine implementation.

Models can account for differences between the trial and real-life settings in transmission levels and healthcare accessibility, as well as predict RTS,S’s impact on malaria mortality, which was not possible to assess in the trial.

Cost-effectiveness

As part of the modeling study, the researchers considered a range of possible prices for RTS,S, from $2 to $10. They found that, compared to current malaria interventions, the vaccine would be cost-effective to implement under an assumed price of USD$5 per dose in areas of moderate and high malaria transmission.

”The cost-effectiveness of RTS,S is similar to what we’ve seen for other recently introduced childhood vaccines,” said Azra Ghani, PhD, of Imperial College London.

“It also overlaps within the ranges of cost-effectiveness of other malaria control interventions like bed nets and indoor residual sprays. However, it is important that the vaccine is introduced in addition to these other highly cost-effective interventions.”

The researchers measured cost-effectiveness in terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), a metric used by health economists to compare the impacts of health interventions in populations over time. One DALY is equivalent to 1 lost year of healthy life. The lower the amount spent per DALY averted, the greater the cost-effectiveness of an intervention.

With the vaccine priced at $5 per dose, the researchers estimated a median cost of $87 per DALY averted for a 4-dose vaccine schedule across the range of transmission settings with parasite prevalence 10% to 65%.

This cost was estimated to vary depending on the level of malaria transmission found in a particular location—with the vaccine being increasingly cost-effective in areas with a higher malaria burden.

The researchers noted that, according to earlier studies, the cost per DALY averted for other malaria interventions indicate averages of $27 for long-lasting, insecticide-treated bed nets; $143 for indoor residual spraying; and $24 for intermittent preventative treatment.

Caveats

The researchers conceded that this study has its limitations. One is the remaining uncertainty regarding the vaccine’s efficacy after the 4 years of follow-up observed in the phase 3 trial.

The team also noted that, since the phase 3 trial of RTS,S was not large enough to test for a reduction in deaths from malaria (versus reduction in incidence of malaria cases) and the quality of care provided to participants was high, the modeling studies’ projection of deaths requires further validation during the implementation phase.

“It will be important to continue to track the long-term impact of this vaccine to ensure that the effectiveness predicted by the models is borne out in practice,” said Caitlin Bever, PhD, of the Institute for Disease Modeling in Bellevue, Washington.

Study challenges ‘textbook’ view of hematopoiesis

University Health Network

Results of a study published in Science challenge traditional ideas about how blood is made.

The findings suggest hematopoiesis does not occur through a gradual process consisting of multipotent, oligopotent, and unilineage progenitor stages.

Rather, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) mature into different types of blood cells quickly, and the process differs between early human development (fetal liver HSCs) and adulthood (HSCs from bone marrow).

The research indicates “that the whole classic ‘textbook’ view we thought we knew doesn’t actually even exist,” said study investigator John Dick, PhD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

He and his colleagues mapped the lineage potential of nearly 3000 single cells from 33 different populations of HSCs obtained from human blood samples taken at various life stages and ages.

The team’s discoveries build on research published in Science in 2011. In that paper, Dr Dick and his colleagues described isolating an HSC in its purest form—as a single cell capable of regenerating the entire blood system.

“Four years ago, when we isolated the pure stem cell, we realized we had also uncovered populations of stem-cell like ‘daughter’ cells that we thought at the time were other types of stem cells,” Dr Dick said.

“When we burrowed further to study these ‘daughters,’ we discovered they were actually already mature blood lineages. In other words, lineages that had broken off almost immediately from the stem cell compartment and had not developed downstream through the slow, gradual ‘textbook’ process.”

“So in human blood formation, everything begins with the stem cell, which is the executive decision-maker quickly driving the process that replenishes blood at a daily rate that exceeds 300 billion cells.”

The investigators believe this work could help advance the manufacture of blood cells in the lab, and it should aid the study of blood disorders.

“Our discovery means we will be able to understand far better a wide variety of human blood disorders and diseases—from anemia . . . to leukemia,” Dr Dick said. “Think of it as moving from the old world of black-and-white television into the new world of high-definition.”

University Health Network

Results of a study published in Science challenge traditional ideas about how blood is made.

The findings suggest hematopoiesis does not occur through a gradual process consisting of multipotent, oligopotent, and unilineage progenitor stages.

Rather, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) mature into different types of blood cells quickly, and the process differs between early human development (fetal liver HSCs) and adulthood (HSCs from bone marrow).

The research indicates “that the whole classic ‘textbook’ view we thought we knew doesn’t actually even exist,” said study investigator John Dick, PhD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

He and his colleagues mapped the lineage potential of nearly 3000 single cells from 33 different populations of HSCs obtained from human blood samples taken at various life stages and ages.

The team’s discoveries build on research published in Science in 2011. In that paper, Dr Dick and his colleagues described isolating an HSC in its purest form—as a single cell capable of regenerating the entire blood system.

“Four years ago, when we isolated the pure stem cell, we realized we had also uncovered populations of stem-cell like ‘daughter’ cells that we thought at the time were other types of stem cells,” Dr Dick said.

“When we burrowed further to study these ‘daughters,’ we discovered they were actually already mature blood lineages. In other words, lineages that had broken off almost immediately from the stem cell compartment and had not developed downstream through the slow, gradual ‘textbook’ process.”

“So in human blood formation, everything begins with the stem cell, which is the executive decision-maker quickly driving the process that replenishes blood at a daily rate that exceeds 300 billion cells.”

The investigators believe this work could help advance the manufacture of blood cells in the lab, and it should aid the study of blood disorders.

“Our discovery means we will be able to understand far better a wide variety of human blood disorders and diseases—from anemia . . . to leukemia,” Dr Dick said. “Think of it as moving from the old world of black-and-white television into the new world of high-definition.”

University Health Network

Results of a study published in Science challenge traditional ideas about how blood is made.

The findings suggest hematopoiesis does not occur through a gradual process consisting of multipotent, oligopotent, and unilineage progenitor stages.

Rather, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) mature into different types of blood cells quickly, and the process differs between early human development (fetal liver HSCs) and adulthood (HSCs from bone marrow).

The research indicates “that the whole classic ‘textbook’ view we thought we knew doesn’t actually even exist,” said study investigator John Dick, PhD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

He and his colleagues mapped the lineage potential of nearly 3000 single cells from 33 different populations of HSCs obtained from human blood samples taken at various life stages and ages.

The team’s discoveries build on research published in Science in 2011. In that paper, Dr Dick and his colleagues described isolating an HSC in its purest form—as a single cell capable of regenerating the entire blood system.

“Four years ago, when we isolated the pure stem cell, we realized we had also uncovered populations of stem-cell like ‘daughter’ cells that we thought at the time were other types of stem cells,” Dr Dick said.

“When we burrowed further to study these ‘daughters,’ we discovered they were actually already mature blood lineages. In other words, lineages that had broken off almost immediately from the stem cell compartment and had not developed downstream through the slow, gradual ‘textbook’ process.”

“So in human blood formation, everything begins with the stem cell, which is the executive decision-maker quickly driving the process that replenishes blood at a daily rate that exceeds 300 billion cells.”

The investigators believe this work could help advance the manufacture of blood cells in the lab, and it should aid the study of blood disorders.

“Our discovery means we will be able to understand far better a wide variety of human blood disorders and diseases—from anemia . . . to leukemia,” Dr Dick said. “Think of it as moving from the old world of black-and-white television into the new world of high-definition.”

HSC self-renewal depends on surroundings

in the bone marrow

Scientists say that, using a model of the hematopoietic system, they have determined which signaling pathways play an essential role in the self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).

They found that a particularly important role in this process is the interactive communication with surrounding tissue cells in the bone marrow.

Robert Oostendorp, PhD, of Klinikum Rechts der Isar der Technischen Universität München in Munich, Germany, and his colleagues described these findings in Stem Cell Reports.

The team noted that, in steady-state conditions, HSCs are maintained as slow-dividing clones of quiescent cells. However, when stress occurs, such as an accident that leads to substantial blood loss or the defense against a pathogen requires more blood cells in the course of an infection, HSCs are activated.

In response, the entire hematopoietic system switches from “standby” mode into a state of alert. The activated HSCs generate new blood cells to counteract the blood loss or combat the pathogen. At the same time, self-renewal keeps the stem cell pool replenished.

This switch is accompanied by a complex communication process between the HSCs and tissue cells—an area that had not previously been examined in depth.

“In our study, we set out to establish which tissue signals are important to stem cell maintenance and functionality, and which HSC signals influence the microenvironment,” Dr Oostendorp said.

He and his colleagues used mixed cultures of tissue cells and HSCs to investigate how these cell types interact.

The scientists analyzed factors that are upregulated or downregulated in the interplay between tissue cells and HSCs. And they linked these findings with the signaling pathways described in existing literature.

The team then consolidated this information in a bioinformatics computer model. And they conducted extensive cell experiments to confirm the computer-generated signaling pathway model.

“The outcome was very interesting indeed,” Dr Oostendorp said. “The entire system operates in a feedback loop. In ‘alert’ mode, the stem cells first influence the behavior of the tissue cells, which, in turn, impact on the stem cells, triggering the self-renewal step.”

In alert mode, HSCs emit signaling substances, which induce tissue cells to release the connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) messenger. This is essential to maintain the HSCs through self-renewal. In the absence of CTGF, HSCs age and cannot replenish the stem cell pool.

“Our findings could prove significant in treating leukemia,” Dr Oostendorp noted. “In this condition, the stem cells are hyperactive, and their division is unchecked. Leukemic blood cells are in a constant state of alert, so we would expect a similar interplay with the tissue cells.”

To date, however, the focus here has been limited to stem cells as the actual source of the defect.

“Given what we know now about feedback loops, it would be important to integrate the surrounding cells in therapeutic approaches too, since they exert a strong influence on stem cell division,” Dr Oostendorp concluded.

in the bone marrow

Scientists say that, using a model of the hematopoietic system, they have determined which signaling pathways play an essential role in the self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).

They found that a particularly important role in this process is the interactive communication with surrounding tissue cells in the bone marrow.

Robert Oostendorp, PhD, of Klinikum Rechts der Isar der Technischen Universität München in Munich, Germany, and his colleagues described these findings in Stem Cell Reports.

The team noted that, in steady-state conditions, HSCs are maintained as slow-dividing clones of quiescent cells. However, when stress occurs, such as an accident that leads to substantial blood loss or the defense against a pathogen requires more blood cells in the course of an infection, HSCs are activated.

In response, the entire hematopoietic system switches from “standby” mode into a state of alert. The activated HSCs generate new blood cells to counteract the blood loss or combat the pathogen. At the same time, self-renewal keeps the stem cell pool replenished.

This switch is accompanied by a complex communication process between the HSCs and tissue cells—an area that had not previously been examined in depth.

“In our study, we set out to establish which tissue signals are important to stem cell maintenance and functionality, and which HSC signals influence the microenvironment,” Dr Oostendorp said.

He and his colleagues used mixed cultures of tissue cells and HSCs to investigate how these cell types interact.

The scientists analyzed factors that are upregulated or downregulated in the interplay between tissue cells and HSCs. And they linked these findings with the signaling pathways described in existing literature.

The team then consolidated this information in a bioinformatics computer model. And they conducted extensive cell experiments to confirm the computer-generated signaling pathway model.

“The outcome was very interesting indeed,” Dr Oostendorp said. “The entire system operates in a feedback loop. In ‘alert’ mode, the stem cells first influence the behavior of the tissue cells, which, in turn, impact on the stem cells, triggering the self-renewal step.”

In alert mode, HSCs emit signaling substances, which induce tissue cells to release the connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) messenger. This is essential to maintain the HSCs through self-renewal. In the absence of CTGF, HSCs age and cannot replenish the stem cell pool.

“Our findings could prove significant in treating leukemia,” Dr Oostendorp noted. “In this condition, the stem cells are hyperactive, and their division is unchecked. Leukemic blood cells are in a constant state of alert, so we would expect a similar interplay with the tissue cells.”

To date, however, the focus here has been limited to stem cells as the actual source of the defect.

“Given what we know now about feedback loops, it would be important to integrate the surrounding cells in therapeutic approaches too, since they exert a strong influence on stem cell division,” Dr Oostendorp concluded.

in the bone marrow

Scientists say that, using a model of the hematopoietic system, they have determined which signaling pathways play an essential role in the self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).

They found that a particularly important role in this process is the interactive communication with surrounding tissue cells in the bone marrow.

Robert Oostendorp, PhD, of Klinikum Rechts der Isar der Technischen Universität München in Munich, Germany, and his colleagues described these findings in Stem Cell Reports.

The team noted that, in steady-state conditions, HSCs are maintained as slow-dividing clones of quiescent cells. However, when stress occurs, such as an accident that leads to substantial blood loss or the defense against a pathogen requires more blood cells in the course of an infection, HSCs are activated.

In response, the entire hematopoietic system switches from “standby” mode into a state of alert. The activated HSCs generate new blood cells to counteract the blood loss or combat the pathogen. At the same time, self-renewal keeps the stem cell pool replenished.

This switch is accompanied by a complex communication process between the HSCs and tissue cells—an area that had not previously been examined in depth.

“In our study, we set out to establish which tissue signals are important to stem cell maintenance and functionality, and which HSC signals influence the microenvironment,” Dr Oostendorp said.

He and his colleagues used mixed cultures of tissue cells and HSCs to investigate how these cell types interact.

The scientists analyzed factors that are upregulated or downregulated in the interplay between tissue cells and HSCs. And they linked these findings with the signaling pathways described in existing literature.

The team then consolidated this information in a bioinformatics computer model. And they conducted extensive cell experiments to confirm the computer-generated signaling pathway model.

“The outcome was very interesting indeed,” Dr Oostendorp said. “The entire system operates in a feedback loop. In ‘alert’ mode, the stem cells first influence the behavior of the tissue cells, which, in turn, impact on the stem cells, triggering the self-renewal step.”

In alert mode, HSCs emit signaling substances, which induce tissue cells to release the connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) messenger. This is essential to maintain the HSCs through self-renewal. In the absence of CTGF, HSCs age and cannot replenish the stem cell pool.

“Our findings could prove significant in treating leukemia,” Dr Oostendorp noted. “In this condition, the stem cells are hyperactive, and their division is unchecked. Leukemic blood cells are in a constant state of alert, so we would expect a similar interplay with the tissue cells.”

To date, however, the focus here has been limited to stem cells as the actual source of the defect.

“Given what we know now about feedback loops, it would be important to integrate the surrounding cells in therapeutic approaches too, since they exert a strong influence on stem cell division,” Dr Oostendorp concluded.

Autophagy works in nucleus to ward off cancer

Image by Sarah Pfau

Autophagy works in the cell nucleus to guard against the start of cancer, according to research published in Nature.

The study showed, for the first time, that autophagy is used to digest nuclear material in mammalian cells.

“We found that the molecular machinery of autophagy guides the degradation of components of the nuclear lamina in mammals,” said study author Shelley Berger, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

The nuclear lamina is a network of protein filaments lining the inside of the membrane of the nucleus. It provides mechanical support to the nucleus and regulates gene expression by making some areas of the genome less or more available to be transcribed into messenger RNA.

Previous studies showed that the autophagy protein LC3 can be found in the nucleus, but it was not clear why, as the protein was thought to be functional in the cytoplasm. Study author Zhixun Dou, PhD, came to the Berger lab with this in mind.

At the same time, Peter Adams, PhD, from the University of Glasgow in Scotland, published a study on the breakdown of the nuclear lamina in which he observed a peculiar protrusion, or blebbing, of the nuclear envelope into the cytoplasm. These blebs contained DNA, nuclear lamina proteins, and chromatin.

This evidence led the Berger and Adams labs to work together to find out what was going on.

Using biochemical and sequencing methods, Dr Dou found that laminB1, a key component of the nuclear lamina, and LC3 were contacting each other in the same places on chromatin.

In fact, LC3 and laminB1 are physically bound to each other. LC3 directly interacts with lamin B1 and binds to lamin-associated domains on chromatin.

Autophagy in cancer and aging

The investigators found that, in response to cellular stress that can cause cancer, LC3, chromatin, and laminB1 migrate from the nucleus—via the nuclear blebs—into the cytoplasm and are eventually targeted for disposal.

This breakdown of laminB1 and other nuclear material leads to senescence. The Berger and Adams labs have been studying senescence in conjunction with cancer for quite some time. One way human cells protect themselves from becoming cancerous is to accelerate aging via senescence so the cells can no longer replicate.

The team showed that when a cell’s DNA is damaged or an oncogene is activated (both of which can cause cancer), a normal cell triggers the digestion of nuclear lamina by autophagy, which promotes senescence. Inhibiting this digestion of nuclear material weakens the senescence program and leads to cancerous growth of cells.

“The nucleus is the headquarters of a cell,” Dr Dou said. “When a cell receives a danger alarm, amazingly, it deliberately messes up its headquarters, with the consequence that many functions are completely stopped for the cell. Our study suggests this new function of autophagy is a guarding mechanism that protects cells from becoming cancerous.”