User login

SCLC Imaging

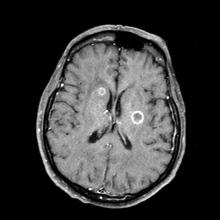

Blurred vision and shortness of breath

Given her symptomatology, imaging, and laboratory study results, this patient is diagnosed with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and brain metastases. The pulmonologist shares the findings with the patient, and over the next several days, a multidisciplinary team, which includes oncology and radiology, forms to guide the patient through staging and treatment options.

SCLC is a neuroendocrine carcinoma, which is an aggressive form of lung cancer associated with rapid growth and early spread to distant sites and frequent association with distinct paraneoplastic syndromes. Approximately 13% of newly diagnosed lung cancers are SCLC. Clinical presentation is often advanced stage and includes shortness of breath, cough, bone pain, weight loss, fatigue, and neurologic dysfunction, including blurred vision, dizziness, and headaches that disturb sleep. Typically, symptom onset is quick, with the duration of symptoms lasting between 8 and 12 weeks before presentation.

According to CHEST guidelines, when clinical and radiographic findings suggest SCLC, diagnosis should be confirmed using the least invasive technique possible on the basis of presentation. Fine-needle aspiration or biopsy is recommended to assess a suspicious singular extrathoracic site for metastasis. If that approach is not feasible, guidelines recommend diagnosing the primary lung lesion. If there is an accessible pleural effusion, ultrasound-guided thoracentesis is recommended for diagnosis. If the result of pleural fluid cytology is negative, pleural biopsy using image-guided pleural biopsy, medical, or surgical thoracoscopy is recommended next. Common mutations associated with SCLC include RB1 and TP53 gene mutations.

Nearly all patients with SCLC (98%) have a history of tobacco use. Uranium or radon exposure has also been linked to SCLC. Pathogenesis occurs in the peribronchial region of the respiratory system and moves into the bronchial submucosa. Widespread metastases can appear early during SCLC and generally affect mediastinal lymph nodes, bones, brain, liver, and adrenal glands.

Patient education should include information about clinical trials, available treatment options, and associated adverse events. Smoking cessation is encouraged for current smokers with SCLC.

For patients with extensive-stage metastatic SCLC, the new standard of care combines the immunotherapy atezolizumab, a humanized monoclonal anti–programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody, with chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide). When used in the first-line setting, this combination has been shown to improve survival outcomes. Of course, clinical trials are ongoing; other treatments in development include additional classes of immunotherapies (programmed cell death protein1 [PD-1] inhibitor antibody, anti-PD1 antibody, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor antibody) and targeted therapies (delta-like protein 3 antibody-drug conjugate).

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given her symptomatology, imaging, and laboratory study results, this patient is diagnosed with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and brain metastases. The pulmonologist shares the findings with the patient, and over the next several days, a multidisciplinary team, which includes oncology and radiology, forms to guide the patient through staging and treatment options.

SCLC is a neuroendocrine carcinoma, which is an aggressive form of lung cancer associated with rapid growth and early spread to distant sites and frequent association with distinct paraneoplastic syndromes. Approximately 13% of newly diagnosed lung cancers are SCLC. Clinical presentation is often advanced stage and includes shortness of breath, cough, bone pain, weight loss, fatigue, and neurologic dysfunction, including blurred vision, dizziness, and headaches that disturb sleep. Typically, symptom onset is quick, with the duration of symptoms lasting between 8 and 12 weeks before presentation.

According to CHEST guidelines, when clinical and radiographic findings suggest SCLC, diagnosis should be confirmed using the least invasive technique possible on the basis of presentation. Fine-needle aspiration or biopsy is recommended to assess a suspicious singular extrathoracic site for metastasis. If that approach is not feasible, guidelines recommend diagnosing the primary lung lesion. If there is an accessible pleural effusion, ultrasound-guided thoracentesis is recommended for diagnosis. If the result of pleural fluid cytology is negative, pleural biopsy using image-guided pleural biopsy, medical, or surgical thoracoscopy is recommended next. Common mutations associated with SCLC include RB1 and TP53 gene mutations.

Nearly all patients with SCLC (98%) have a history of tobacco use. Uranium or radon exposure has also been linked to SCLC. Pathogenesis occurs in the peribronchial region of the respiratory system and moves into the bronchial submucosa. Widespread metastases can appear early during SCLC and generally affect mediastinal lymph nodes, bones, brain, liver, and adrenal glands.

Patient education should include information about clinical trials, available treatment options, and associated adverse events. Smoking cessation is encouraged for current smokers with SCLC.

For patients with extensive-stage metastatic SCLC, the new standard of care combines the immunotherapy atezolizumab, a humanized monoclonal anti–programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody, with chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide). When used in the first-line setting, this combination has been shown to improve survival outcomes. Of course, clinical trials are ongoing; other treatments in development include additional classes of immunotherapies (programmed cell death protein1 [PD-1] inhibitor antibody, anti-PD1 antibody, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor antibody) and targeted therapies (delta-like protein 3 antibody-drug conjugate).

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given her symptomatology, imaging, and laboratory study results, this patient is diagnosed with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and brain metastases. The pulmonologist shares the findings with the patient, and over the next several days, a multidisciplinary team, which includes oncology and radiology, forms to guide the patient through staging and treatment options.

SCLC is a neuroendocrine carcinoma, which is an aggressive form of lung cancer associated with rapid growth and early spread to distant sites and frequent association with distinct paraneoplastic syndromes. Approximately 13% of newly diagnosed lung cancers are SCLC. Clinical presentation is often advanced stage and includes shortness of breath, cough, bone pain, weight loss, fatigue, and neurologic dysfunction, including blurred vision, dizziness, and headaches that disturb sleep. Typically, symptom onset is quick, with the duration of symptoms lasting between 8 and 12 weeks before presentation.

According to CHEST guidelines, when clinical and radiographic findings suggest SCLC, diagnosis should be confirmed using the least invasive technique possible on the basis of presentation. Fine-needle aspiration or biopsy is recommended to assess a suspicious singular extrathoracic site for metastasis. If that approach is not feasible, guidelines recommend diagnosing the primary lung lesion. If there is an accessible pleural effusion, ultrasound-guided thoracentesis is recommended for diagnosis. If the result of pleural fluid cytology is negative, pleural biopsy using image-guided pleural biopsy, medical, or surgical thoracoscopy is recommended next. Common mutations associated with SCLC include RB1 and TP53 gene mutations.

Nearly all patients with SCLC (98%) have a history of tobacco use. Uranium or radon exposure has also been linked to SCLC. Pathogenesis occurs in the peribronchial region of the respiratory system and moves into the bronchial submucosa. Widespread metastases can appear early during SCLC and generally affect mediastinal lymph nodes, bones, brain, liver, and adrenal glands.

Patient education should include information about clinical trials, available treatment options, and associated adverse events. Smoking cessation is encouraged for current smokers with SCLC.

For patients with extensive-stage metastatic SCLC, the new standard of care combines the immunotherapy atezolizumab, a humanized monoclonal anti–programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody, with chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide). When used in the first-line setting, this combination has been shown to improve survival outcomes. Of course, clinical trials are ongoing; other treatments in development include additional classes of immunotherapies (programmed cell death protein1 [PD-1] inhibitor antibody, anti-PD1 antibody, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor antibody) and targeted therapies (delta-like protein 3 antibody-drug conjugate).

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 66-year-old woman who is a former smoker presents to her primary care physician with a recent history of dizziness, blurred vision, shortness of breath, and headaches that wake her up in the morning. The patient reports significant weight loss, persistent cough, and fatigue over the past 2 months. The patient owns and runs a local French bakery and reports difficulty keeping up with routine productivity. In addition, she has had to skip several days of work lately and rely more on her staff, which increases business costs, because of the severity of her symptoms. Her height is 5 ft 6 in and weight is 176 lb; her BMI is 28.4.

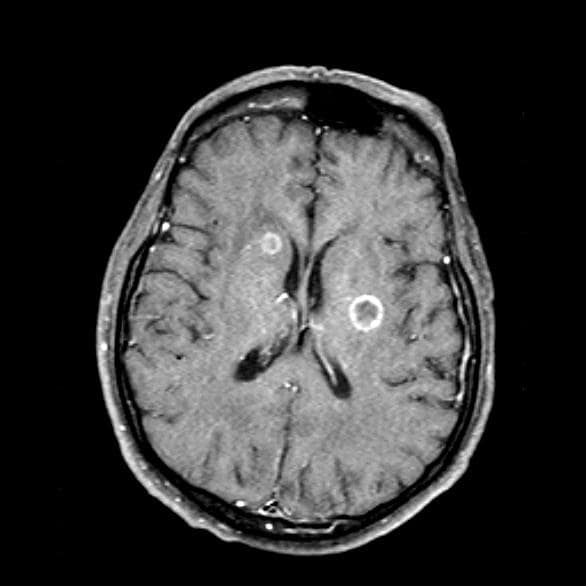

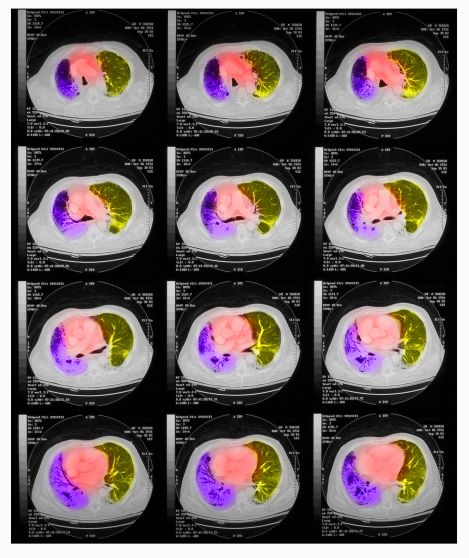

On physical examination, her physician detects enlarged axillary lymph nodes and dullness to percussion and decreased breath sounds in the central right lung. Fundoscopy reveals increased intracranial pressure, and a neurologic exam shows abnormalities in cerebellar function. The physician orders a CT from the base of the skull to mid-thigh as well as a brain MRI. Results show tumors in the right ipsilateral hemithorax and contralateral lung and metastases in the brain. The patient is referred to pulmonology, where she undergoes a fine needle aspiration of the suspected axillary lymph nodes; cytology reveals metastatic cancer. Thereafter, the patient undergoes a bronchoscopy and transbronchial biopsy. Comprehensive genomic profiling of the tumor sample reveals TP53 and RB1 gene mutations.

SCLC Pathophysiology & Epidemiology

Cough and hemoptysis

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of combined small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Globally, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer incidence and mortality, accounting for an estimated 2 million new diagnoses and 1.76 million deaths per year. It consists of two major subtypes: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and SCLC. SCLC is unique in its presentation, imaging appearances, treatment, and prognosis. SCLC accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancers and is associated with an exceptionally high proliferative rate, strong predilection for early metastasis, and poor prognosis.

There are two subtypes of SCLC: oat cell carcinoma and combined SCLC. Combined SCLC is defined as SCLC with non-small cell components, such as squamous cell or adenocarcinoma. Men are affected more frequently than are women. Most presenting patients are older than 70 years and are either a current or former smoker. Patients frequently have multiple cardiovascular or pulmonary comorbidities.

In most cases, patients experience rapid onset of symptoms, normally beginning 8-12 weeks before presentation. Signs and symptoms vary depending on the location and bulk of the primary tumor, but may include cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis as well as weight loss, debility, and other signs of metastatic disease. Local intrathoracic tumor growth can affect the superior vena cava (leading to superior vena cava syndrome), chest wall, or esophagus. Neurologic problems, recurrent nerve pain, fatigue, and anorexia may result from extrapulmonary metastasis. Nearly 60% of patients present with metastatic disease, most commonly in the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bone, and bone marrow. If left untreated, SCLC tumors progress rapidly, with a median survival of 2-4 months.

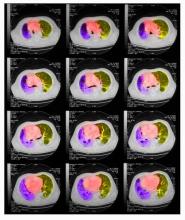

All patients with SCLC require a thorough staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. The initial imaging workup includes plain film radiography and contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and upper abdomen, brain MRI, and PET-CT. Laboratory studies to evaluate for the presence of neoplastic syndromes include complete blood count, electrolytes, calcium, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, and creatinine. Biopsy is usually obtained via CT-guided biopsy or transbronchial biopsy, though this can vary depending on the location of the tumor.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), most patients with limited-stage SCLC are not eligible for surgery or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR). Surgery is only recommended for select patients with stage I–IIA SCLC (about 5% of patients). Concurrent chemoradiation or SABR is recommended for patients with limited stage I-IIA (T1-2,N0) SCLC who are ineligible for or do not want to pursue surgical resection. The majority of patients with SCLC have extensive-stage disease, and treatment with systemic therapy alone (with or without palliative radiotherapy) is recommended. Preferred cytotoxic and immunotherapeutic agents can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of combined small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Globally, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer incidence and mortality, accounting for an estimated 2 million new diagnoses and 1.76 million deaths per year. It consists of two major subtypes: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and SCLC. SCLC is unique in its presentation, imaging appearances, treatment, and prognosis. SCLC accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancers and is associated with an exceptionally high proliferative rate, strong predilection for early metastasis, and poor prognosis.

There are two subtypes of SCLC: oat cell carcinoma and combined SCLC. Combined SCLC is defined as SCLC with non-small cell components, such as squamous cell or adenocarcinoma. Men are affected more frequently than are women. Most presenting patients are older than 70 years and are either a current or former smoker. Patients frequently have multiple cardiovascular or pulmonary comorbidities.

In most cases, patients experience rapid onset of symptoms, normally beginning 8-12 weeks before presentation. Signs and symptoms vary depending on the location and bulk of the primary tumor, but may include cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis as well as weight loss, debility, and other signs of metastatic disease. Local intrathoracic tumor growth can affect the superior vena cava (leading to superior vena cava syndrome), chest wall, or esophagus. Neurologic problems, recurrent nerve pain, fatigue, and anorexia may result from extrapulmonary metastasis. Nearly 60% of patients present with metastatic disease, most commonly in the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bone, and bone marrow. If left untreated, SCLC tumors progress rapidly, with a median survival of 2-4 months.

All patients with SCLC require a thorough staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. The initial imaging workup includes plain film radiography and contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and upper abdomen, brain MRI, and PET-CT. Laboratory studies to evaluate for the presence of neoplastic syndromes include complete blood count, electrolytes, calcium, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, and creatinine. Biopsy is usually obtained via CT-guided biopsy or transbronchial biopsy, though this can vary depending on the location of the tumor.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), most patients with limited-stage SCLC are not eligible for surgery or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR). Surgery is only recommended for select patients with stage I–IIA SCLC (about 5% of patients). Concurrent chemoradiation or SABR is recommended for patients with limited stage I-IIA (T1-2,N0) SCLC who are ineligible for or do not want to pursue surgical resection. The majority of patients with SCLC have extensive-stage disease, and treatment with systemic therapy alone (with or without palliative radiotherapy) is recommended. Preferred cytotoxic and immunotherapeutic agents can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of combined small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Globally, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer incidence and mortality, accounting for an estimated 2 million new diagnoses and 1.76 million deaths per year. It consists of two major subtypes: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and SCLC. SCLC is unique in its presentation, imaging appearances, treatment, and prognosis. SCLC accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancers and is associated with an exceptionally high proliferative rate, strong predilection for early metastasis, and poor prognosis.

There are two subtypes of SCLC: oat cell carcinoma and combined SCLC. Combined SCLC is defined as SCLC with non-small cell components, such as squamous cell or adenocarcinoma. Men are affected more frequently than are women. Most presenting patients are older than 70 years and are either a current or former smoker. Patients frequently have multiple cardiovascular or pulmonary comorbidities.

In most cases, patients experience rapid onset of symptoms, normally beginning 8-12 weeks before presentation. Signs and symptoms vary depending on the location and bulk of the primary tumor, but may include cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis as well as weight loss, debility, and other signs of metastatic disease. Local intrathoracic tumor growth can affect the superior vena cava (leading to superior vena cava syndrome), chest wall, or esophagus. Neurologic problems, recurrent nerve pain, fatigue, and anorexia may result from extrapulmonary metastasis. Nearly 60% of patients present with metastatic disease, most commonly in the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bone, and bone marrow. If left untreated, SCLC tumors progress rapidly, with a median survival of 2-4 months.

All patients with SCLC require a thorough staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. The initial imaging workup includes plain film radiography and contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and upper abdomen, brain MRI, and PET-CT. Laboratory studies to evaluate for the presence of neoplastic syndromes include complete blood count, electrolytes, calcium, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, and creatinine. Biopsy is usually obtained via CT-guided biopsy or transbronchial biopsy, though this can vary depending on the location of the tumor.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), most patients with limited-stage SCLC are not eligible for surgery or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR). Surgery is only recommended for select patients with stage I–IIA SCLC (about 5% of patients). Concurrent chemoradiation or SABR is recommended for patients with limited stage I-IIA (T1-2,N0) SCLC who are ineligible for or do not want to pursue surgical resection. The majority of patients with SCLC have extensive-stage disease, and treatment with systemic therapy alone (with or without palliative radiotherapy) is recommended. Preferred cytotoxic and immunotherapeutic agents can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 74-year-old man presents to the emergency department with reports of cough, hemoptysis, and unintentional weight loss of approximately 8 weeks' duration. The patient has a 35-year history of smoking (35 pack years). The patient's vital signs include temperature of 98.4 °F, BP of 135/80 mm Hg, and pulse oximeter reading of 94%. Physical examination reveals rales over the left side of the chest and decreased breath sounds in bilateral bases of the lungs. The patient appears cachexic. He is 6 ft 2 in and weighs 163 lb.

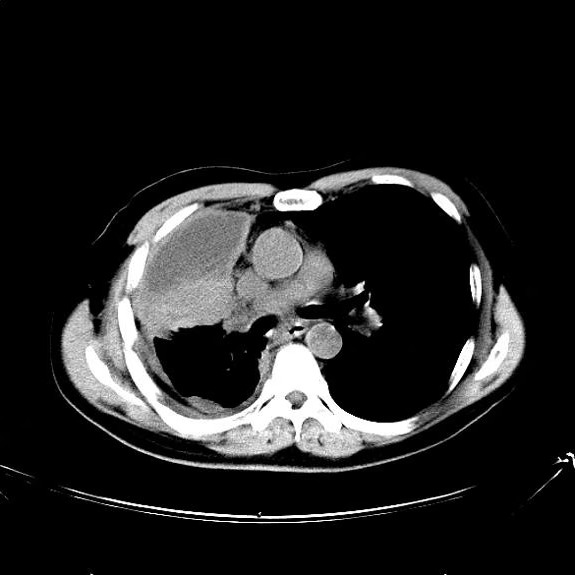

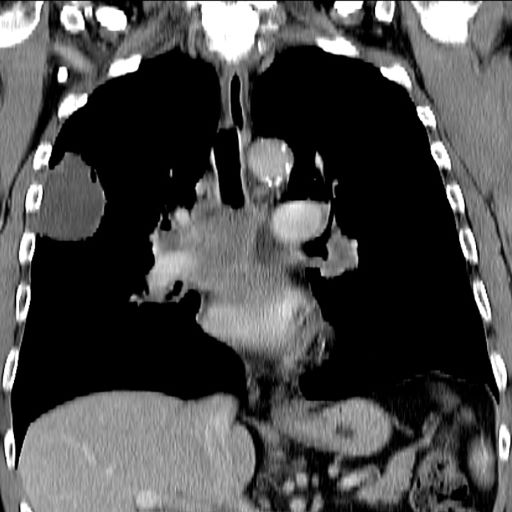

A chest radiograph reveals a mass in the right lung field. A subsequent CT of the chest reveals multiple pulmonary nodules and extensive mediastinal nodal metastases. Histopathology reveals small, uniform, poorly differentiated necrotic cancers and adenocarcinoma with papillary and acinar features.

SCLC: Presentation and Diagnosis

Older woman presents with shortness of breath

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is the most aggressive lung cancer subtype, has a poor prognosis, and is highly associated with smoking. It accounts for 10%-15% of all lung cancers. Rapid tumor growth may lead to obstruction of major airways, with distal collapse leading to postobstructive pneumonitis, infection, and fever. SCLCs usually grow rapidly and metastasize to mediastinal lymph nodes relatively early in the course of the disease. At presentation, patients may have very large intrathoracic tumors, and distinguishing the primary tumor from lymph node metastases may be difficult.

CT of all common sites of metastasis should be performed to stage the disease. CT scanning of the thorax (lungs and mediastinum) and commonly involved abdominal viscera is the minimum requirement in standard staging workup of SCLC. Intravenous contrast agents should be used whenever possible. In the United States, CT scans of the chest and upper abdomen to include the liver and adrenal glands are standard. The liver is a common site of metastasis.

Most cases of SCLC will present in advanced stages, be inoperable, and have a dismal prognosis. Only about 5% of patients present at an early stage (Ia, Ib, or IIa). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that these patients be managed with aggressive chemoradiation therapy; in some, lobectomy associated with mediastinal lymph node dissection may be performed. The NCCN notes that advanced disease is managed primarily with chemotherapy, mainly for palliation and symptom control. Older patients, such as the current patient, who have a good performance status (ECOG 0 or 1) and intact organ function should receive standard carboplatin-based chemotherapy. However, even those who have poor prognostic factors (eg, poor performance status, medically significant concomitant conditions) may still be considered for chemotherapy if appropriate precautions are taken to avoid excessive toxicity and further decline in performance status.

Unlike non-SCLC, which has seen waves of new drug approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the prognosis for SCLC has not changed substantially in the past two decades and remains poor. However, the FDA approved atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin and etoposide for first-line treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage SCLC. Further, the approval of durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy; and the approval of lurbinectedin, a novel chemotherapy agent approved for second-line treatment of SCLC, have added to the therapeutic options for patients with SCLC.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is the most aggressive lung cancer subtype, has a poor prognosis, and is highly associated with smoking. It accounts for 10%-15% of all lung cancers. Rapid tumor growth may lead to obstruction of major airways, with distal collapse leading to postobstructive pneumonitis, infection, and fever. SCLCs usually grow rapidly and metastasize to mediastinal lymph nodes relatively early in the course of the disease. At presentation, patients may have very large intrathoracic tumors, and distinguishing the primary tumor from lymph node metastases may be difficult.

CT of all common sites of metastasis should be performed to stage the disease. CT scanning of the thorax (lungs and mediastinum) and commonly involved abdominal viscera is the minimum requirement in standard staging workup of SCLC. Intravenous contrast agents should be used whenever possible. In the United States, CT scans of the chest and upper abdomen to include the liver and adrenal glands are standard. The liver is a common site of metastasis.

Most cases of SCLC will present in advanced stages, be inoperable, and have a dismal prognosis. Only about 5% of patients present at an early stage (Ia, Ib, or IIa). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that these patients be managed with aggressive chemoradiation therapy; in some, lobectomy associated with mediastinal lymph node dissection may be performed. The NCCN notes that advanced disease is managed primarily with chemotherapy, mainly for palliation and symptom control. Older patients, such as the current patient, who have a good performance status (ECOG 0 or 1) and intact organ function should receive standard carboplatin-based chemotherapy. However, even those who have poor prognostic factors (eg, poor performance status, medically significant concomitant conditions) may still be considered for chemotherapy if appropriate precautions are taken to avoid excessive toxicity and further decline in performance status.

Unlike non-SCLC, which has seen waves of new drug approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the prognosis for SCLC has not changed substantially in the past two decades and remains poor. However, the FDA approved atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin and etoposide for first-line treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage SCLC. Further, the approval of durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy; and the approval of lurbinectedin, a novel chemotherapy agent approved for second-line treatment of SCLC, have added to the therapeutic options for patients with SCLC.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is the most aggressive lung cancer subtype, has a poor prognosis, and is highly associated with smoking. It accounts for 10%-15% of all lung cancers. Rapid tumor growth may lead to obstruction of major airways, with distal collapse leading to postobstructive pneumonitis, infection, and fever. SCLCs usually grow rapidly and metastasize to mediastinal lymph nodes relatively early in the course of the disease. At presentation, patients may have very large intrathoracic tumors, and distinguishing the primary tumor from lymph node metastases may be difficult.

CT of all common sites of metastasis should be performed to stage the disease. CT scanning of the thorax (lungs and mediastinum) and commonly involved abdominal viscera is the minimum requirement in standard staging workup of SCLC. Intravenous contrast agents should be used whenever possible. In the United States, CT scans of the chest and upper abdomen to include the liver and adrenal glands are standard. The liver is a common site of metastasis.

Most cases of SCLC will present in advanced stages, be inoperable, and have a dismal prognosis. Only about 5% of patients present at an early stage (Ia, Ib, or IIa). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that these patients be managed with aggressive chemoradiation therapy; in some, lobectomy associated with mediastinal lymph node dissection may be performed. The NCCN notes that advanced disease is managed primarily with chemotherapy, mainly for palliation and symptom control. Older patients, such as the current patient, who have a good performance status (ECOG 0 or 1) and intact organ function should receive standard carboplatin-based chemotherapy. However, even those who have poor prognostic factors (eg, poor performance status, medically significant concomitant conditions) may still be considered for chemotherapy if appropriate precautions are taken to avoid excessive toxicity and further decline in performance status.

Unlike non-SCLC, which has seen waves of new drug approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the prognosis for SCLC has not changed substantially in the past two decades and remains poor. However, the FDA approved atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin and etoposide for first-line treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage SCLC. Further, the approval of durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy; and the approval of lurbinectedin, a novel chemotherapy agent approved for second-line treatment of SCLC, have added to the therapeutic options for patients with SCLC.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 72-year-old woman presents with shortness of breath, a productive cough, chest pain, some fatigue, anorexia, a recent 18-pound weight loss, and a history of hypertension. She is currently a smoker and has a 45–pack-year smoking history. On physical examination she has some dullness to percussion with some decreased breath sounds. She has a distended abdomen and complains of itchy skin. The chest x-ray shows a left hilar mass and a 5.4-cm left upper-lobe mass. A CT scan reveals a hilar mass with a mediastinal extension.

Shortness of breath and chest pain

Liver biopsy will reveal the cause of the liver dysfunction and confirm whether this patient has small cell lung cancer (SCLC), as suspected, and whether it has spread to the liver. This will affect chemotherapy options.

Most cases of SCLC will present in advanced stages, be inoperable, and have a dismal prognosis. Only about 5% of patients present at an early stage (Ia, Ib, or IIa). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that patients with advanced disease be managed with aggressive chemoradiation therapy and immunotherapy.

SCLC is the most aggressive lung cancer subtype. It is almost always associated with smoking. It accounts for 10%-15% of all lung cancers. Rapid tumor growth may lead to obstruction of major airways, with distal collapse leading to postobstructive pneumonitis, infection, and fever. About 70% of patients show metastatic spread at presentation, and the liver is one of the most common sites of metastasis.

Unlike non-SCLC, for which the prognosis has improved in part because of several new drug approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration, the prognosis for SCLC has not changed substantially in the past two decades and remains poor. However, with immunotherapy, the outlook may be improving. The NCCN recommends atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin and etoposide for first-line treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage SCLC. Furthermore, the approval of durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy and the approval of lurbinectedin, a novel chemotherapy agent approved for second-line treatment of SCLC, have added to the therapeutic options for patients with advanced SCLC.

Maurie Markman, MD, President, Department of Medical Oncology, Cancer Treatment Centers of America.

Maurie Markman, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Merck

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Novis; Glaxo Smith Kline

Received research grants from: AstraZeneca; Novis; GSK; Merck

Liver biopsy will reveal the cause of the liver dysfunction and confirm whether this patient has small cell lung cancer (SCLC), as suspected, and whether it has spread to the liver. This will affect chemotherapy options.

Most cases of SCLC will present in advanced stages, be inoperable, and have a dismal prognosis. Only about 5% of patients present at an early stage (Ia, Ib, or IIa). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that patients with advanced disease be managed with aggressive chemoradiation therapy and immunotherapy.

SCLC is the most aggressive lung cancer subtype. It is almost always associated with smoking. It accounts for 10%-15% of all lung cancers. Rapid tumor growth may lead to obstruction of major airways, with distal collapse leading to postobstructive pneumonitis, infection, and fever. About 70% of patients show metastatic spread at presentation, and the liver is one of the most common sites of metastasis.

Unlike non-SCLC, for which the prognosis has improved in part because of several new drug approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration, the prognosis for SCLC has not changed substantially in the past two decades and remains poor. However, with immunotherapy, the outlook may be improving. The NCCN recommends atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin and etoposide for first-line treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage SCLC. Furthermore, the approval of durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy and the approval of lurbinectedin, a novel chemotherapy agent approved for second-line treatment of SCLC, have added to the therapeutic options for patients with advanced SCLC.

Maurie Markman, MD, President, Department of Medical Oncology, Cancer Treatment Centers of America.

Maurie Markman, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Merck

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Novis; Glaxo Smith Kline

Received research grants from: AstraZeneca; Novis; GSK; Merck

Liver biopsy will reveal the cause of the liver dysfunction and confirm whether this patient has small cell lung cancer (SCLC), as suspected, and whether it has spread to the liver. This will affect chemotherapy options.

Most cases of SCLC will present in advanced stages, be inoperable, and have a dismal prognosis. Only about 5% of patients present at an early stage (Ia, Ib, or IIa). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that patients with advanced disease be managed with aggressive chemoradiation therapy and immunotherapy.

SCLC is the most aggressive lung cancer subtype. It is almost always associated with smoking. It accounts for 10%-15% of all lung cancers. Rapid tumor growth may lead to obstruction of major airways, with distal collapse leading to postobstructive pneumonitis, infection, and fever. About 70% of patients show metastatic spread at presentation, and the liver is one of the most common sites of metastasis.

Unlike non-SCLC, for which the prognosis has improved in part because of several new drug approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration, the prognosis for SCLC has not changed substantially in the past two decades and remains poor. However, with immunotherapy, the outlook may be improving. The NCCN recommends atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin and etoposide for first-line treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage SCLC. Furthermore, the approval of durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy and the approval of lurbinectedin, a novel chemotherapy agent approved for second-line treatment of SCLC, have added to the therapeutic options for patients with advanced SCLC.

Maurie Markman, MD, President, Department of Medical Oncology, Cancer Treatment Centers of America.

Maurie Markman, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Merck

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Novis; Glaxo Smith Kline

Received research grants from: AstraZeneca; Novis; GSK; Merck

A 64-year-old man presents with shortness of breath, a productive cough, chest pain, some fatigue, anorexia, a recent 15-lb weight loss, jaundice, and a history of type 2 diabetes. He is a college professor and has a 35–pack-year smoking history; he quit 3 years ago.

On physical examination, he has dullness to percussion and decreased breath sounds. His laboratory data reveal elevated serum liver enzyme levels. Chest radiography shows a left hilar mass and a 5.6-cm left upper lobe mass. CT reveals a hilar mass with a bilateral mediastinal extension and pneumonia. PET shows activity in the left upper lobe mass, with supraclavicular nodal areas and liver lesions. MRI shows that there are no metastases to the brain.

SCLC: The Basics

Increasing fatigue and dry cough

This patient's clinical presentation is consistent with a diagnosis of superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS), secondary to SCLC.

SCLC is an aggressive, poorly differentiated, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma that accounts for approximately 13%-15% of all new lung cancer cases in the United States. SCLC has a propensity for early dissemination; as such, 80%-85% of patients are diagnosed with extensive disease (ES-SCLC). This is common in heavy smokers. Most SCLC tumors are found in hilar or perihilar areas; <5% present in peripheral locations. In many cases, invasion into the peribronchial tissue and lymph node can be clearly identified, with a typical circumferential spread along the submucosa of the bronchi.

Up to 10% of patients with SCLC develop SVCS, which comprises an array of signs and symptoms that result from the obstruction of blood flow through the thin-walled superior vena cava. Clinical symptoms may include cough, dyspnea, and orthopnea; facial edema and plethora, upper extremity swelling, and venous distension of the chest wall and neck are the most commonly encountered signs. Most cases of SVCS occur in patients with mediastinal tumors, although noncancerous causes (eg, thrombosis and fibrosing mediastinitis) can also give rise to it. The diagnosis of SVCS is usually made clinically and then confirmed with imaging (chest radiography, contrast-enhanced CT, duplex ultrasound, conventional venography, and/or magnetic resonance venography).

Though it was traditionally considered a virtual emergency, patients seldom experience life-threatening complications from SVCS. The goals of treatment are to alleviate the symptoms of SVC obstruction and treat the underlying disease process. Treatment approaches include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, open surgery, and endovenous recanalization; however, patients with clinical SVCS often achieve significant improvement in symptoms from conservative treatment approaches, including elevation of the head of the bed and supplemental oxygen. Systemic chemotherapy can effectively relieve the symptoms of SVCS obstruction, typically within 1-2 weeks of treatment initiation. Up to 80% of patients with SCLC and non-Hodgkin lymphoma may experience complete relief of SVCS symptoms with chemotherapy treatment.

Radiation therapy was once considered the standard approach to the management of SVCS in patients with cancer; however, endovenous recanalization can alleviate symptoms faster than radiation therapy — usually within 72 hours, whereas radiation therapy can take up to 2 weeks to provide relief. Endovascular therapy is also associated with higher efficacy rates than is radiation therapy.

Open surgery plays a limited role in the management of SVC obstruction, although it may be the best approach in select cases.

In cases involving brain edema, decreased cardiac output, or upper airway edema, emergency treatment is indicated.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation is consistent with a diagnosis of superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS), secondary to SCLC.

SCLC is an aggressive, poorly differentiated, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma that accounts for approximately 13%-15% of all new lung cancer cases in the United States. SCLC has a propensity for early dissemination; as such, 80%-85% of patients are diagnosed with extensive disease (ES-SCLC). This is common in heavy smokers. Most SCLC tumors are found in hilar or perihilar areas; <5% present in peripheral locations. In many cases, invasion into the peribronchial tissue and lymph node can be clearly identified, with a typical circumferential spread along the submucosa of the bronchi.

Up to 10% of patients with SCLC develop SVCS, which comprises an array of signs and symptoms that result from the obstruction of blood flow through the thin-walled superior vena cava. Clinical symptoms may include cough, dyspnea, and orthopnea; facial edema and plethora, upper extremity swelling, and venous distension of the chest wall and neck are the most commonly encountered signs. Most cases of SVCS occur in patients with mediastinal tumors, although noncancerous causes (eg, thrombosis and fibrosing mediastinitis) can also give rise to it. The diagnosis of SVCS is usually made clinically and then confirmed with imaging (chest radiography, contrast-enhanced CT, duplex ultrasound, conventional venography, and/or magnetic resonance venography).

Though it was traditionally considered a virtual emergency, patients seldom experience life-threatening complications from SVCS. The goals of treatment are to alleviate the symptoms of SVC obstruction and treat the underlying disease process. Treatment approaches include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, open surgery, and endovenous recanalization; however, patients with clinical SVCS often achieve significant improvement in symptoms from conservative treatment approaches, including elevation of the head of the bed and supplemental oxygen. Systemic chemotherapy can effectively relieve the symptoms of SVCS obstruction, typically within 1-2 weeks of treatment initiation. Up to 80% of patients with SCLC and non-Hodgkin lymphoma may experience complete relief of SVCS symptoms with chemotherapy treatment.

Radiation therapy was once considered the standard approach to the management of SVCS in patients with cancer; however, endovenous recanalization can alleviate symptoms faster than radiation therapy — usually within 72 hours, whereas radiation therapy can take up to 2 weeks to provide relief. Endovascular therapy is also associated with higher efficacy rates than is radiation therapy.

Open surgery plays a limited role in the management of SVC obstruction, although it may be the best approach in select cases.

In cases involving brain edema, decreased cardiac output, or upper airway edema, emergency treatment is indicated.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation is consistent with a diagnosis of superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS), secondary to SCLC.

SCLC is an aggressive, poorly differentiated, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma that accounts for approximately 13%-15% of all new lung cancer cases in the United States. SCLC has a propensity for early dissemination; as such, 80%-85% of patients are diagnosed with extensive disease (ES-SCLC). This is common in heavy smokers. Most SCLC tumors are found in hilar or perihilar areas; <5% present in peripheral locations. In many cases, invasion into the peribronchial tissue and lymph node can be clearly identified, with a typical circumferential spread along the submucosa of the bronchi.

Up to 10% of patients with SCLC develop SVCS, which comprises an array of signs and symptoms that result from the obstruction of blood flow through the thin-walled superior vena cava. Clinical symptoms may include cough, dyspnea, and orthopnea; facial edema and plethora, upper extremity swelling, and venous distension of the chest wall and neck are the most commonly encountered signs. Most cases of SVCS occur in patients with mediastinal tumors, although noncancerous causes (eg, thrombosis and fibrosing mediastinitis) can also give rise to it. The diagnosis of SVCS is usually made clinically and then confirmed with imaging (chest radiography, contrast-enhanced CT, duplex ultrasound, conventional venography, and/or magnetic resonance venography).

Though it was traditionally considered a virtual emergency, patients seldom experience life-threatening complications from SVCS. The goals of treatment are to alleviate the symptoms of SVC obstruction and treat the underlying disease process. Treatment approaches include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, open surgery, and endovenous recanalization; however, patients with clinical SVCS often achieve significant improvement in symptoms from conservative treatment approaches, including elevation of the head of the bed and supplemental oxygen. Systemic chemotherapy can effectively relieve the symptoms of SVCS obstruction, typically within 1-2 weeks of treatment initiation. Up to 80% of patients with SCLC and non-Hodgkin lymphoma may experience complete relief of SVCS symptoms with chemotherapy treatment.

Radiation therapy was once considered the standard approach to the management of SVCS in patients with cancer; however, endovenous recanalization can alleviate symptoms faster than radiation therapy — usually within 72 hours, whereas radiation therapy can take up to 2 weeks to provide relief. Endovascular therapy is also associated with higher efficacy rates than is radiation therapy.

Open surgery plays a limited role in the management of SVC obstruction, although it may be the best approach in select cases.

In cases involving brain edema, decreased cardiac output, or upper airway edema, emergency treatment is indicated.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 66-year-old African American man was diagnosed with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) after the discovery of an endobronchial tumor on bronchoscopy. A biopsy of the tumor was positive for SCLC and CT revealed multiple pulmonary nodules and extensive mediastinal nodal metastases. The patient completed his first cycle of carboplatin-based chemotherapy about 1 month ago. At today's visit, he presents with complaints of worsening symptoms over the past week or so; specifically, he reports increasing fatigue and shortness of breath, a dry cough, light-headedness, difficulty swallowing, and facial swelling. Physical examination reveals facial edema and venous distension of the neck and chest wall; blood pressure is 140/70 mm Hg, respiratory rate is 19 breaths/min, and pulse is 84 beats/min. The patient has a 45-pack-year smoking history and reports having two or three alcoholic drinks per day. His previous medical history is positive for hypertension, which is treated with enalapril 20 mg/day and metoprolol 200 mg/day. Complete blood cell count findings are all within normal range.