User login

Council of Networks: Reflecting on the success of 2024

I have had the privilege of being the Chair of the Council of Networks this past year, and the engagement of the Chairs, Vice-Chairs, and steering committee members has contributed to a very successful CHEST 2024. Highlights from the meeting include the depth and breadth of 22 Experience CHEST sessions, which were held in the Exhibit Hall and gave trainees and early career faculty the opportunity to submit and present concise teaching on a topic. This year, many of these presentations were devoted to topics of diversity and inclusion.

Our program this year also honored Network Rising Stars at the Network Open Forums. These individuals were early career members who were nominated for their active engagement within CHEST and the Networks. The Networks also hosted a fun and engaging mixer, where members came together and had the opportunity to meet Network leadership, catch up with old friends, and sample a variety of Boston cuisine. I personally had the opportunity to meet several junior faculty who were excited to become involved in the Networks.

One of the initiatives we are working on is developing a robust mentoring program for fellows who are involved in the Networks and Sections. The pieces were put in place over the summer, and we will be gauging success of the program in the spring.

For those of you who have yet to join a Network, we would love for you to be involved. To see the current leadership of each Network, check out their pages on chesnet.org. You can log in to your CHEST account and join as many Networks as you want.

I have had the privilege of being the Chair of the Council of Networks this past year, and the engagement of the Chairs, Vice-Chairs, and steering committee members has contributed to a very successful CHEST 2024. Highlights from the meeting include the depth and breadth of 22 Experience CHEST sessions, which were held in the Exhibit Hall and gave trainees and early career faculty the opportunity to submit and present concise teaching on a topic. This year, many of these presentations were devoted to topics of diversity and inclusion.

Our program this year also honored Network Rising Stars at the Network Open Forums. These individuals were early career members who were nominated for their active engagement within CHEST and the Networks. The Networks also hosted a fun and engaging mixer, where members came together and had the opportunity to meet Network leadership, catch up with old friends, and sample a variety of Boston cuisine. I personally had the opportunity to meet several junior faculty who were excited to become involved in the Networks.

One of the initiatives we are working on is developing a robust mentoring program for fellows who are involved in the Networks and Sections. The pieces were put in place over the summer, and we will be gauging success of the program in the spring.

For those of you who have yet to join a Network, we would love for you to be involved. To see the current leadership of each Network, check out their pages on chesnet.org. You can log in to your CHEST account and join as many Networks as you want.

I have had the privilege of being the Chair of the Council of Networks this past year, and the engagement of the Chairs, Vice-Chairs, and steering committee members has contributed to a very successful CHEST 2024. Highlights from the meeting include the depth and breadth of 22 Experience CHEST sessions, which were held in the Exhibit Hall and gave trainees and early career faculty the opportunity to submit and present concise teaching on a topic. This year, many of these presentations were devoted to topics of diversity and inclusion.

Our program this year also honored Network Rising Stars at the Network Open Forums. These individuals were early career members who were nominated for their active engagement within CHEST and the Networks. The Networks also hosted a fun and engaging mixer, where members came together and had the opportunity to meet Network leadership, catch up with old friends, and sample a variety of Boston cuisine. I personally had the opportunity to meet several junior faculty who were excited to become involved in the Networks.

One of the initiatives we are working on is developing a robust mentoring program for fellows who are involved in the Networks and Sections. The pieces were put in place over the summer, and we will be gauging success of the program in the spring.

For those of you who have yet to join a Network, we would love for you to be involved. To see the current leadership of each Network, check out their pages on chesnet.org. You can log in to your CHEST account and join as many Networks as you want.

A visible impact

In 2023, CHEST’s philanthropic approach evolved to align with the organizational mission and elevate the value placed on giving. This was a pivotal transformation allowing CHEST to broaden its scope and deepen its impact, ensuring that every contribution continues to make a meaningful difference. 2024 was the first full year since the transition, and Bob Musacchio, PhD, CEO of CHEST, and Bob De Marco, MD, FCCP, Chair of the CHEST Board of Advisors, sat down to reflect on the year of CHEST philanthropy.

It’s been a full year since the transition to CHEST philanthropy; from your perspective, how has that transition gone so far?

Bob De Marco, MD, FCCP: It’s been a real pleasure to watch the evolution over the past year. The pillars that we defined to support our giving strategy resonated with a lot of past donors and also helped to engage new donors. Through clinical research, community impact, and dedication to education, we know exactly where our focus should be, allowing us to have the strongest impact while ensuring that donors know exactly where their gifts are going.

Bob Musacchio, PhD: Another benefit to the redefined strategy was its clear integration with the CHEST organization. In the past year, CHEST added social responsibility as one of the organizational pillars, which clarified the commitment to both philanthropy and advocacy. By aligning every element of philanthropy with the existing CHEST mission, we are able to expand our reach exponentially.

Let’s talk about an example of impact you’ve seen in the past year.

De Marco: When the original CHEST Foundation merged with CHEST, we established a new priority that continues to drive our mission: bridging gaps, breaking barriers, and improving health care interactions to enhance patient outcomes and overall health. This commitment is reflected in initiatives like Bridging Specialties® and the First 5 Minutes®—both of which you can learn more about on the CHEST website.

We’ve also entered into the second year of our partnership grant with the Association of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Program Directors, which supports a fellow pursuing pulmonary and critical care medicine. This award recognizes the value of a diverse community in advancing medical education in pulmonary and critical care medicine. It provides an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education fellow-in-training with the support, training, and mentorship needed to pursue a career in medical education and eventually serve as a mentor to future trainees.

Musacchio: I’d like to highlight the growth we’ve seen in our Community Impact grants. Following the shift, the impact grants now follow a participatory grantmaking model that empowers local organizations embedded within their communities to solve problems with the unique insights and solutions that only they can provide. This new strategy includes supporting our Community Connections partners, which are highlighted during the annual meeting. In Boston for CHEST 2024, we partnered with three local organizations—Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, We Got Us, and the Tufts Community Health Workers Engaging in Integrated Care and Community Action Programs Inter-City collaboration—as our Community Connections to financially support their causes and to highlight their work throughout our meeting. Through partnership, we can strengthen our impact and empower communities to prioritize and improve respiratory well-being, and I look forward to continuing to grow this program in Chicago for CHEST 2025.

What’s next for CHEST philanthropy? Any closing thoughts for CHEST Physician® readers?

De Marco: The future is limitless for CHEST philanthropy. The more funding we receive, the more we can distribute to deserving projects. This includes expanding support to additional disease states, funding the next wave of travel grants, and giving more to support the research and clinical innovations that will shape the future of chest medicine . What I’d love to see is more CHEST members engaging with CHEST philanthropy. We invite you to connect with us—CHEST’s philanthropy team—to discuss how your continued investment can drive even greater impact or ask any questions you may have about the program. We’d welcome the opportunity to talk with you!

Also, if you’re thinking about giving before the end of the year, please know that every gift, new or increased, will be matched dollar for dollar through December 31.

To each and every one of you: Thank you for being a part of the CHEST community—and for your generosity and dedication.

Musacchio: I echo Dr. De Marco’s sentiment and want to reiterate that whether you’re a seasoned donor or considering your first gift, you can play a vital role in shaping the future of our field. Every gift—large or small—moves us forward and strengthens the community we all value. Thank you, and have a happy and healthy holiday season.

MAKE A GIFT TODAY

In 2023, CHEST’s philanthropic approach evolved to align with the organizational mission and elevate the value placed on giving. This was a pivotal transformation allowing CHEST to broaden its scope and deepen its impact, ensuring that every contribution continues to make a meaningful difference. 2024 was the first full year since the transition, and Bob Musacchio, PhD, CEO of CHEST, and Bob De Marco, MD, FCCP, Chair of the CHEST Board of Advisors, sat down to reflect on the year of CHEST philanthropy.

It’s been a full year since the transition to CHEST philanthropy; from your perspective, how has that transition gone so far?

Bob De Marco, MD, FCCP: It’s been a real pleasure to watch the evolution over the past year. The pillars that we defined to support our giving strategy resonated with a lot of past donors and also helped to engage new donors. Through clinical research, community impact, and dedication to education, we know exactly where our focus should be, allowing us to have the strongest impact while ensuring that donors know exactly where their gifts are going.

Bob Musacchio, PhD: Another benefit to the redefined strategy was its clear integration with the CHEST organization. In the past year, CHEST added social responsibility as one of the organizational pillars, which clarified the commitment to both philanthropy and advocacy. By aligning every element of philanthropy with the existing CHEST mission, we are able to expand our reach exponentially.

Let’s talk about an example of impact you’ve seen in the past year.

De Marco: When the original CHEST Foundation merged with CHEST, we established a new priority that continues to drive our mission: bridging gaps, breaking barriers, and improving health care interactions to enhance patient outcomes and overall health. This commitment is reflected in initiatives like Bridging Specialties® and the First 5 Minutes®—both of which you can learn more about on the CHEST website.

We’ve also entered into the second year of our partnership grant with the Association of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Program Directors, which supports a fellow pursuing pulmonary and critical care medicine. This award recognizes the value of a diverse community in advancing medical education in pulmonary and critical care medicine. It provides an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education fellow-in-training with the support, training, and mentorship needed to pursue a career in medical education and eventually serve as a mentor to future trainees.

Musacchio: I’d like to highlight the growth we’ve seen in our Community Impact grants. Following the shift, the impact grants now follow a participatory grantmaking model that empowers local organizations embedded within their communities to solve problems with the unique insights and solutions that only they can provide. This new strategy includes supporting our Community Connections partners, which are highlighted during the annual meeting. In Boston for CHEST 2024, we partnered with three local organizations—Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, We Got Us, and the Tufts Community Health Workers Engaging in Integrated Care and Community Action Programs Inter-City collaboration—as our Community Connections to financially support their causes and to highlight their work throughout our meeting. Through partnership, we can strengthen our impact and empower communities to prioritize and improve respiratory well-being, and I look forward to continuing to grow this program in Chicago for CHEST 2025.

What’s next for CHEST philanthropy? Any closing thoughts for CHEST Physician® readers?

De Marco: The future is limitless for CHEST philanthropy. The more funding we receive, the more we can distribute to deserving projects. This includes expanding support to additional disease states, funding the next wave of travel grants, and giving more to support the research and clinical innovations that will shape the future of chest medicine . What I’d love to see is more CHEST members engaging with CHEST philanthropy. We invite you to connect with us—CHEST’s philanthropy team—to discuss how your continued investment can drive even greater impact or ask any questions you may have about the program. We’d welcome the opportunity to talk with you!

Also, if you’re thinking about giving before the end of the year, please know that every gift, new or increased, will be matched dollar for dollar through December 31.

To each and every one of you: Thank you for being a part of the CHEST community—and for your generosity and dedication.

Musacchio: I echo Dr. De Marco’s sentiment and want to reiterate that whether you’re a seasoned donor or considering your first gift, you can play a vital role in shaping the future of our field. Every gift—large or small—moves us forward and strengthens the community we all value. Thank you, and have a happy and healthy holiday season.

MAKE A GIFT TODAY

In 2023, CHEST’s philanthropic approach evolved to align with the organizational mission and elevate the value placed on giving. This was a pivotal transformation allowing CHEST to broaden its scope and deepen its impact, ensuring that every contribution continues to make a meaningful difference. 2024 was the first full year since the transition, and Bob Musacchio, PhD, CEO of CHEST, and Bob De Marco, MD, FCCP, Chair of the CHEST Board of Advisors, sat down to reflect on the year of CHEST philanthropy.

It’s been a full year since the transition to CHEST philanthropy; from your perspective, how has that transition gone so far?

Bob De Marco, MD, FCCP: It’s been a real pleasure to watch the evolution over the past year. The pillars that we defined to support our giving strategy resonated with a lot of past donors and also helped to engage new donors. Through clinical research, community impact, and dedication to education, we know exactly where our focus should be, allowing us to have the strongest impact while ensuring that donors know exactly where their gifts are going.

Bob Musacchio, PhD: Another benefit to the redefined strategy was its clear integration with the CHEST organization. In the past year, CHEST added social responsibility as one of the organizational pillars, which clarified the commitment to both philanthropy and advocacy. By aligning every element of philanthropy with the existing CHEST mission, we are able to expand our reach exponentially.

Let’s talk about an example of impact you’ve seen in the past year.

De Marco: When the original CHEST Foundation merged with CHEST, we established a new priority that continues to drive our mission: bridging gaps, breaking barriers, and improving health care interactions to enhance patient outcomes and overall health. This commitment is reflected in initiatives like Bridging Specialties® and the First 5 Minutes®—both of which you can learn more about on the CHEST website.

We’ve also entered into the second year of our partnership grant with the Association of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Program Directors, which supports a fellow pursuing pulmonary and critical care medicine. This award recognizes the value of a diverse community in advancing medical education in pulmonary and critical care medicine. It provides an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education fellow-in-training with the support, training, and mentorship needed to pursue a career in medical education and eventually serve as a mentor to future trainees.

Musacchio: I’d like to highlight the growth we’ve seen in our Community Impact grants. Following the shift, the impact grants now follow a participatory grantmaking model that empowers local organizations embedded within their communities to solve problems with the unique insights and solutions that only they can provide. This new strategy includes supporting our Community Connections partners, which are highlighted during the annual meeting. In Boston for CHEST 2024, we partnered with three local organizations—Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, We Got Us, and the Tufts Community Health Workers Engaging in Integrated Care and Community Action Programs Inter-City collaboration—as our Community Connections to financially support their causes and to highlight their work throughout our meeting. Through partnership, we can strengthen our impact and empower communities to prioritize and improve respiratory well-being, and I look forward to continuing to grow this program in Chicago for CHEST 2025.

What’s next for CHEST philanthropy? Any closing thoughts for CHEST Physician® readers?

De Marco: The future is limitless for CHEST philanthropy. The more funding we receive, the more we can distribute to deserving projects. This includes expanding support to additional disease states, funding the next wave of travel grants, and giving more to support the research and clinical innovations that will shape the future of chest medicine . What I’d love to see is more CHEST members engaging with CHEST philanthropy. We invite you to connect with us—CHEST’s philanthropy team—to discuss how your continued investment can drive even greater impact or ask any questions you may have about the program. We’d welcome the opportunity to talk with you!

Also, if you’re thinking about giving before the end of the year, please know that every gift, new or increased, will be matched dollar for dollar through December 31.

To each and every one of you: Thank you for being a part of the CHEST community—and for your generosity and dedication.

Musacchio: I echo Dr. De Marco’s sentiment and want to reiterate that whether you’re a seasoned donor or considering your first gift, you can play a vital role in shaping the future of our field. Every gift—large or small—moves us forward and strengthens the community we all value. Thank you, and have a happy and healthy holiday season.

MAKE A GIFT TODAY

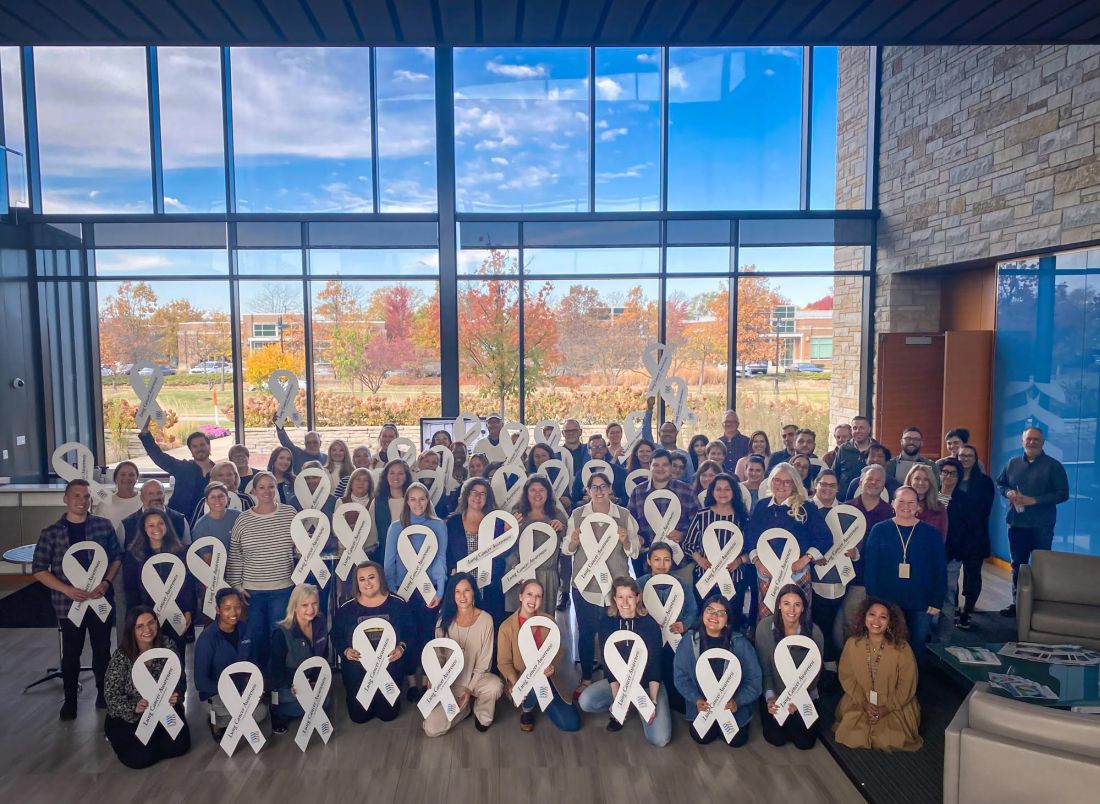

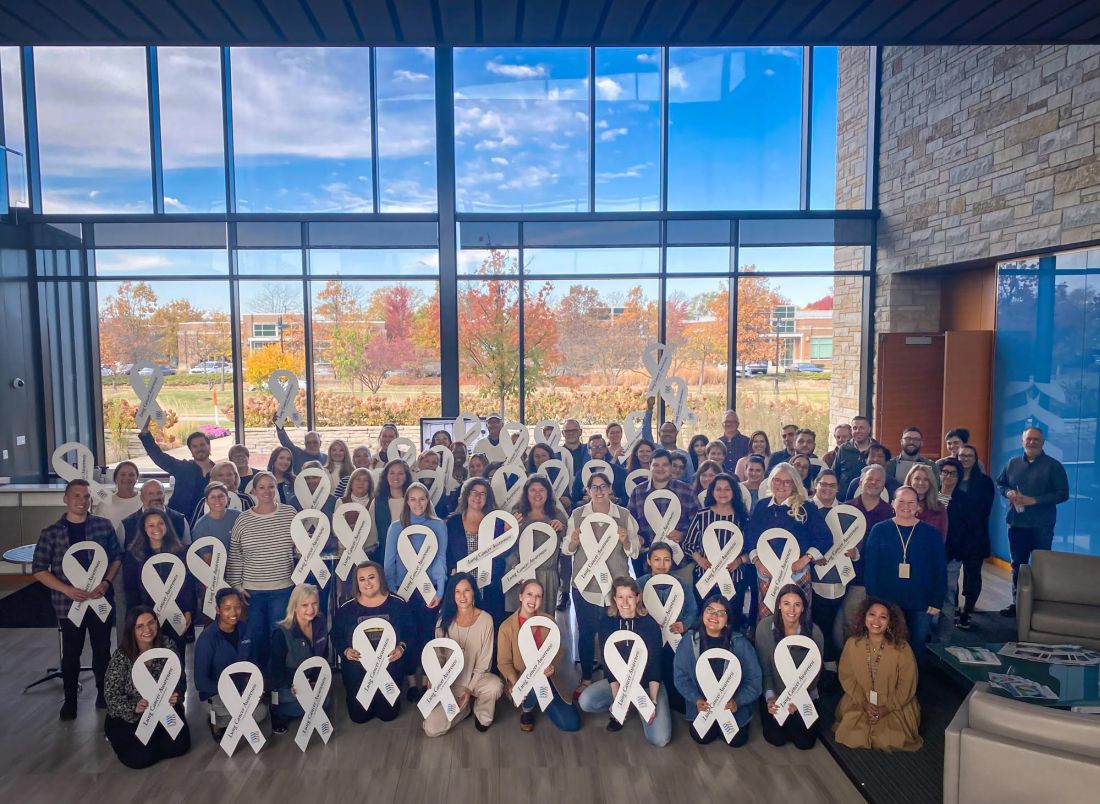

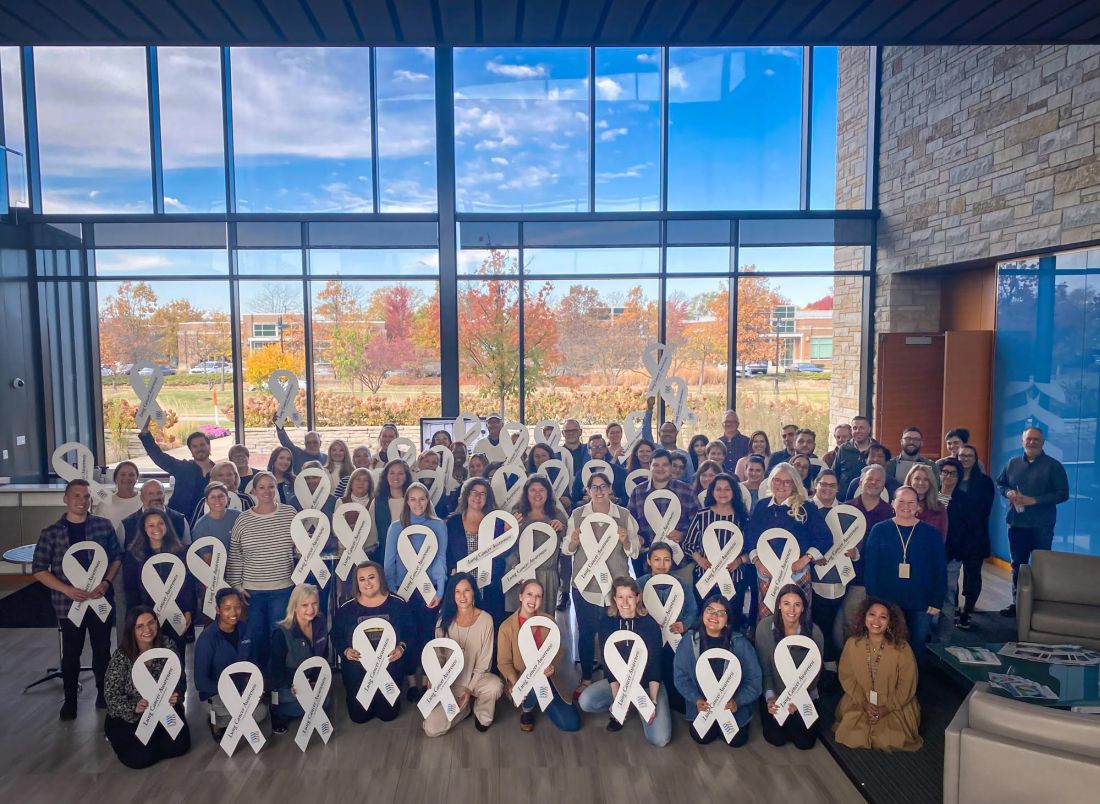

White ribbons around CHEST HQ raise awareness for lung cancer screening and early detection

During the month of November, CHEST displayed white ribbons around its headquarters in Glenview, Illinois, to raise awareness for lung cancer screening and early detection.

According to the World Health Organization, lung cancer kills more people yearly than breast, colon, and prostate cancers combined, and there are 2.1 million lung cancer cases worldwide.

“Lung Cancer Awareness Month was an opportunity for us to shine the spotlight on a disease that is impacting the lives of so many,” said Robert Musacchio, PhD, CEO of CHEST. “As a society of 22,000 respiratory professionals, we continuously provide the latest resources to our members, including the latest guidelines for lung cancer screening. Leveraging the awareness month, we wanted to spread the message throughout our local community that the best way to combat lung cancer is through early screening and detection.”

To identify and diagnose lung cancer in its earlier stages, it is recommended to seek lung cancer screening with a low-dose tomography scan (also known as low-dose CT or LDCT scan). Individuals who meet the below criteria are considered to be at high risk for developing lung cancer and should be screened:

- 50 to 80 years of age;

- have a 20 pack-year history of smoking (one pack a day for 20 years, two packs a day for 10 years, etc.); or

- currently smoke or have quit within the last 15 years.

To secure the ribbons, CHEST worked with an organization called the White Ribbon Project, which promotes awareness about lung cancer by changing public perception of the disease. Started by lung cancer survivor Heidi Onda and her husband, Pierre Onda, MD, the white ribbon initiative has spurred a movement to build community, reframe education, increase awareness, and remove the stigma against lung cancer.

“We are grateful for the advocacy and support of the American College of Chest Physicians in raising awareness for lung cancer,” Ms. Onda said. “We believe as a team of survivors, caregivers, those who have lost loved ones, advocates, the medical and science communities, industry representatives, advocacy organizations, legislators, and cancer centers that we can change the public perception of lung cancer. Anyone with lungs can get lung cancer, no one deserves it, and awareness and early detection of the disease are crucial.”

During the month of November, CHEST displayed white ribbons around its headquarters in Glenview, Illinois, to raise awareness for lung cancer screening and early detection.

According to the World Health Organization, lung cancer kills more people yearly than breast, colon, and prostate cancers combined, and there are 2.1 million lung cancer cases worldwide.

“Lung Cancer Awareness Month was an opportunity for us to shine the spotlight on a disease that is impacting the lives of so many,” said Robert Musacchio, PhD, CEO of CHEST. “As a society of 22,000 respiratory professionals, we continuously provide the latest resources to our members, including the latest guidelines for lung cancer screening. Leveraging the awareness month, we wanted to spread the message throughout our local community that the best way to combat lung cancer is through early screening and detection.”

To identify and diagnose lung cancer in its earlier stages, it is recommended to seek lung cancer screening with a low-dose tomography scan (also known as low-dose CT or LDCT scan). Individuals who meet the below criteria are considered to be at high risk for developing lung cancer and should be screened:

- 50 to 80 years of age;

- have a 20 pack-year history of smoking (one pack a day for 20 years, two packs a day for 10 years, etc.); or

- currently smoke or have quit within the last 15 years.

To secure the ribbons, CHEST worked with an organization called the White Ribbon Project, which promotes awareness about lung cancer by changing public perception of the disease. Started by lung cancer survivor Heidi Onda and her husband, Pierre Onda, MD, the white ribbon initiative has spurred a movement to build community, reframe education, increase awareness, and remove the stigma against lung cancer.

“We are grateful for the advocacy and support of the American College of Chest Physicians in raising awareness for lung cancer,” Ms. Onda said. “We believe as a team of survivors, caregivers, those who have lost loved ones, advocates, the medical and science communities, industry representatives, advocacy organizations, legislators, and cancer centers that we can change the public perception of lung cancer. Anyone with lungs can get lung cancer, no one deserves it, and awareness and early detection of the disease are crucial.”

During the month of November, CHEST displayed white ribbons around its headquarters in Glenview, Illinois, to raise awareness for lung cancer screening and early detection.

According to the World Health Organization, lung cancer kills more people yearly than breast, colon, and prostate cancers combined, and there are 2.1 million lung cancer cases worldwide.

“Lung Cancer Awareness Month was an opportunity for us to shine the spotlight on a disease that is impacting the lives of so many,” said Robert Musacchio, PhD, CEO of CHEST. “As a society of 22,000 respiratory professionals, we continuously provide the latest resources to our members, including the latest guidelines for lung cancer screening. Leveraging the awareness month, we wanted to spread the message throughout our local community that the best way to combat lung cancer is through early screening and detection.”

To identify and diagnose lung cancer in its earlier stages, it is recommended to seek lung cancer screening with a low-dose tomography scan (also known as low-dose CT or LDCT scan). Individuals who meet the below criteria are considered to be at high risk for developing lung cancer and should be screened:

- 50 to 80 years of age;

- have a 20 pack-year history of smoking (one pack a day for 20 years, two packs a day for 10 years, etc.); or

- currently smoke or have quit within the last 15 years.

To secure the ribbons, CHEST worked with an organization called the White Ribbon Project, which promotes awareness about lung cancer by changing public perception of the disease. Started by lung cancer survivor Heidi Onda and her husband, Pierre Onda, MD, the white ribbon initiative has spurred a movement to build community, reframe education, increase awareness, and remove the stigma against lung cancer.

“We are grateful for the advocacy and support of the American College of Chest Physicians in raising awareness for lung cancer,” Ms. Onda said. “We believe as a team of survivors, caregivers, those who have lost loved ones, advocates, the medical and science communities, industry representatives, advocacy organizations, legislators, and cancer centers that we can change the public perception of lung cancer. Anyone with lungs can get lung cancer, no one deserves it, and awareness and early detection of the disease are crucial.”

Get to know Incoming CHEST President, John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP

Starting January 1, 2025, current President-Elect, John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP, will become the new President of CHEST.

Before Dr. Howington steps into the role of President, he spoke with CHEST for a glimpse into his aspirations for 2025.

What would you like to accomplish as President of CHEST?

First, I want to express my gratitude for the honor and privilege of serving as the 87th President of CHEST. The organization is well-served by a high functioning Board of Regents and an incredible staff. My primary goal is to build on the success and momentum of the presidential years of Dr. Buckley and Dr. Addrizzo-Harris. Their annual meetings were a huge success, and the energy and enthusiasm of our members are palpable.

I feel very strongly that great things are ahead of us in the fields of pulmonary medicine and critical care. The CHEST organization will continue to focus on our mission to crush lung disease and stay true to our values of community, inclusivity, innovation, advocacy, and integrity. With 2025 marking the 90th anniversary of the college, I very much look forward to sharing the impact of the organization and showcasing what is yet to come.

We will continue to collaborate with sister societies and like-minded industry partners to improve the quality of patient care and support clinicians in our field. Specifically, I look forward to continuing the momentum we’ve seen in early identification of lung cancer and increasing cure rates. Working as a team of interventional pulmonologists, respiratory therapists, advanced practice providers, thoracic surgeons, and more, we can make a real impact on what it means to be diagnosed with lung cancer.

What do you consider to be CHEST’s greatest strength, and how will you build upon this during your presidency?

CHEST’s greatest strength is the people involved with the organization. There is such a wonderful culture of inclusivity and innovation cultivated by the outstanding staff, committed volunteers, and expert faculty leaders. We have focused on continuous board development for the last eight years and are seeing the benefits in the strategic and innovative steps the Board of Regents have taken to better serve our members and patients. It’s an honor to step into the role of leading such an extraordinary group.

What are some of the challenges facing CHEST, and how will you address them?

While not unique to CHEST, stress and burnout remain an issue in the field of health care. Clinicians are asked to do more with limited resources to provide high-quality care to an increasing number of patients with widely varying needs. We will continue to focus on providing guidance on best practices in the field of chest medicine and sharing innovations that reduce the burdens of health care delivery. To help alleviate the stress put on clinicians, we want to do our part to help remove anything that stands between a clinician and their ability to provide the best care for patients.

What do you ask of members to support you during your presidency?

What I would ask of our members is that they reach out to connect. I want to both celebrate your wins in the field and work with your suggestions to improve CHEST. Making the organization stronger is a collaborative effort, and every voice matters. My email starting January 1 is [email protected], and if you need some writing inspiration, I’ve got some suggested prompts:

- Share with me a recent personal success or that of a colleague; we want to help spread the word.

- What do you find most rewarding in your practice?

- What’s a recurring challenge you face in practice?

- What is CHEST getting right? Where can we improve?

I look forward to hearing from you.

Warmest regards,

John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP

Starting January 1, 2025, current President-Elect, John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP, will become the new President of CHEST.

Before Dr. Howington steps into the role of President, he spoke with CHEST for a glimpse into his aspirations for 2025.

What would you like to accomplish as President of CHEST?

First, I want to express my gratitude for the honor and privilege of serving as the 87th President of CHEST. The organization is well-served by a high functioning Board of Regents and an incredible staff. My primary goal is to build on the success and momentum of the presidential years of Dr. Buckley and Dr. Addrizzo-Harris. Their annual meetings were a huge success, and the energy and enthusiasm of our members are palpable.

I feel very strongly that great things are ahead of us in the fields of pulmonary medicine and critical care. The CHEST organization will continue to focus on our mission to crush lung disease and stay true to our values of community, inclusivity, innovation, advocacy, and integrity. With 2025 marking the 90th anniversary of the college, I very much look forward to sharing the impact of the organization and showcasing what is yet to come.

We will continue to collaborate with sister societies and like-minded industry partners to improve the quality of patient care and support clinicians in our field. Specifically, I look forward to continuing the momentum we’ve seen in early identification of lung cancer and increasing cure rates. Working as a team of interventional pulmonologists, respiratory therapists, advanced practice providers, thoracic surgeons, and more, we can make a real impact on what it means to be diagnosed with lung cancer.

What do you consider to be CHEST’s greatest strength, and how will you build upon this during your presidency?

CHEST’s greatest strength is the people involved with the organization. There is such a wonderful culture of inclusivity and innovation cultivated by the outstanding staff, committed volunteers, and expert faculty leaders. We have focused on continuous board development for the last eight years and are seeing the benefits in the strategic and innovative steps the Board of Regents have taken to better serve our members and patients. It’s an honor to step into the role of leading such an extraordinary group.

What are some of the challenges facing CHEST, and how will you address them?

While not unique to CHEST, stress and burnout remain an issue in the field of health care. Clinicians are asked to do more with limited resources to provide high-quality care to an increasing number of patients with widely varying needs. We will continue to focus on providing guidance on best practices in the field of chest medicine and sharing innovations that reduce the burdens of health care delivery. To help alleviate the stress put on clinicians, we want to do our part to help remove anything that stands between a clinician and their ability to provide the best care for patients.

What do you ask of members to support you during your presidency?

What I would ask of our members is that they reach out to connect. I want to both celebrate your wins in the field and work with your suggestions to improve CHEST. Making the organization stronger is a collaborative effort, and every voice matters. My email starting January 1 is [email protected], and if you need some writing inspiration, I’ve got some suggested prompts:

- Share with me a recent personal success or that of a colleague; we want to help spread the word.

- What do you find most rewarding in your practice?

- What’s a recurring challenge you face in practice?

- What is CHEST getting right? Where can we improve?

I look forward to hearing from you.

Warmest regards,

John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP

Starting January 1, 2025, current President-Elect, John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP, will become the new President of CHEST.

Before Dr. Howington steps into the role of President, he spoke with CHEST for a glimpse into his aspirations for 2025.

What would you like to accomplish as President of CHEST?

First, I want to express my gratitude for the honor and privilege of serving as the 87th President of CHEST. The organization is well-served by a high functioning Board of Regents and an incredible staff. My primary goal is to build on the success and momentum of the presidential years of Dr. Buckley and Dr. Addrizzo-Harris. Their annual meetings were a huge success, and the energy and enthusiasm of our members are palpable.

I feel very strongly that great things are ahead of us in the fields of pulmonary medicine and critical care. The CHEST organization will continue to focus on our mission to crush lung disease and stay true to our values of community, inclusivity, innovation, advocacy, and integrity. With 2025 marking the 90th anniversary of the college, I very much look forward to sharing the impact of the organization and showcasing what is yet to come.

We will continue to collaborate with sister societies and like-minded industry partners to improve the quality of patient care and support clinicians in our field. Specifically, I look forward to continuing the momentum we’ve seen in early identification of lung cancer and increasing cure rates. Working as a team of interventional pulmonologists, respiratory therapists, advanced practice providers, thoracic surgeons, and more, we can make a real impact on what it means to be diagnosed with lung cancer.

What do you consider to be CHEST’s greatest strength, and how will you build upon this during your presidency?

CHEST’s greatest strength is the people involved with the organization. There is such a wonderful culture of inclusivity and innovation cultivated by the outstanding staff, committed volunteers, and expert faculty leaders. We have focused on continuous board development for the last eight years and are seeing the benefits in the strategic and innovative steps the Board of Regents have taken to better serve our members and patients. It’s an honor to step into the role of leading such an extraordinary group.

What are some of the challenges facing CHEST, and how will you address them?

While not unique to CHEST, stress and burnout remain an issue in the field of health care. Clinicians are asked to do more with limited resources to provide high-quality care to an increasing number of patients with widely varying needs. We will continue to focus on providing guidance on best practices in the field of chest medicine and sharing innovations that reduce the burdens of health care delivery. To help alleviate the stress put on clinicians, we want to do our part to help remove anything that stands between a clinician and their ability to provide the best care for patients.

What do you ask of members to support you during your presidency?

What I would ask of our members is that they reach out to connect. I want to both celebrate your wins in the field and work with your suggestions to improve CHEST. Making the organization stronger is a collaborative effort, and every voice matters. My email starting January 1 is [email protected], and if you need some writing inspiration, I’ve got some suggested prompts:

- Share with me a recent personal success or that of a colleague; we want to help spread the word.

- What do you find most rewarding in your practice?

- What’s a recurring challenge you face in practice?

- What is CHEST getting right? Where can we improve?

I look forward to hearing from you.

Warmest regards,

John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP

RBC transfusion guidelines in critical care: Making the case for a restrictive approach

In the high-stakes environment of the intensive care unit (ICU), red blood cell (RBC) transfusions are a common intervention. With approximately 25% of critically ill patients in the US receiving RBC transfusions, optimizing the approach to transfusion is vital not only for patient safety but also for resource management. For the bedside clinician and health care systems, this presents both an opportunity and a challenge: to recalibrate transfusion practices while maintaining the highest standards of patient care.

Why a restrictive strategy?

Historically, transfusions were administered to optimize oxygen delivery to organs in the presence of anemia. However, studies have highlighted the risks associated with transfusions, such as transfusion-related lung injury, circulatory overload, and increased nosocomial infections. These risks are particularly pronounced in critically ill patients, who are often more vulnerable to complications from any additional physiological burden.

The restrictive approach—typically recommended at a hemoglobin threshold of 7 to 8 g/dL—has been shown to be the safer alternative for most ICU patients, as highlighted in recently published clinical guidelines. The data supporting this approach suggest that a restrictive transfusion strategy not only spares patients unnecessary transfusions but also aligns with cost-effective and resource-efficient health care practices.

Key recommendations

For ICU providers, this guideline presents specific recommendations based on a patient’s condition:

• General critical illness: The restrictive approach is preferred over a permissive one, with no adverse effect on ICU mortality, one-year survival, or adverse events. In other words, lower Hgb thresholds do not correlate with poorer outcomes in most critically ill patients.

• Acute gastrointestinal bleeding: Evidence favors a restrictive approach, associated with reduced rebleeding risk and short-term mortality. Studies show a significantly lower incidence of transfusion reactions and costs without compromising patient safety.

• Acute coronary syndrome (ACS): A more cautious approach is advised here. In cases of ACS, a restrictive RBC transfusion strategy could potentially increase the risk of cardiac death. It is recommended to avoid a restrictive approach, as it remains unclear whether there is a gradient effect—where risk progressively increases below a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL—or a threshold effect at 10 g/dL. In other words, the data does not clarify if a hemoglobin level of 9 g/dL is as safe as 10 g/dL. An individualized transfusion approach, considering patient symptoms and other physiological markers, is recommended.

• Post-cardiac surgery: For postoperative patients, a restrictive strategy is suggested, as it conserves RBCs without impacting outcomes such as mortality or length of hospital stay.

• Isolated troponin elevation: In cases of elevated troponin without evidence of cardiac ischemia, transfusion decisions should consider additional patient-specific variables, with a restrictive approach as the baseline.

• Septic shock: RBC transfusions as part of a resuscitation bundle were not analyzed, as isolating the impact of RBC transfusions from other bundle elements was not feasible. However, with no clear benefit and similar adverse effects, neither strategy proved clinically superior. Nonetheless, a restrictive approach conserves RBC units, thereby saving resources and reducing costs.

The economics of restriction

Beyond clinical benefits, a restrictive approach conserves precious health care resources. With the cost of a single RBC unit hovering around $200—and significantly higher once administrative and logistic expenses are accounted for—reducing unnecessary transfusions translates into substantial savings. For a health care system already strained by limited blood supply and rising demand, a 40% reduction in transfusions across ICUs could alleviate supply pressures and contribute to more equitable resource distribution.

Easier said than done

Adopting a restrictive transfusion policy is not without challenges. Clinicians are trained to act decisively in critical situations, and, often, the instinct is to do more rather than less. However, studies indicate that with proper education, awareness, and decision-support systems, a restrictive policy is both feasible and effective. Institutions may consider behavior modification strategies, such as standardized transfusion order sets and decision-support tools within electronic medical records, to aid in adjusting transfusion practices.

Call to action

The message is clear: For most critically ill patients, a restrictive RBC transfusion strategy is not only safe but optimal. For ICU teams, this calls for a proactive shift in approach. It is a call to scrutinize transfusion triggers and lean toward a judicious, evidence-based approach.

While cases like ACS may require a different approach, the evidence strongly supports that, under most circumstances, less is more. Embracing this approach requires careful consideration, yet the potential benefits for patient safety and health care sustainability are compelling.

As critical care professionals, let us lead the way in refining transfusion practices to uphold patient safety, optimize resources, and adapt to evidence-based guidelines.

ACCESS THE FULL GUIDELINE

In the high-stakes environment of the intensive care unit (ICU), red blood cell (RBC) transfusions are a common intervention. With approximately 25% of critically ill patients in the US receiving RBC transfusions, optimizing the approach to transfusion is vital not only for patient safety but also for resource management. For the bedside clinician and health care systems, this presents both an opportunity and a challenge: to recalibrate transfusion practices while maintaining the highest standards of patient care.

Why a restrictive strategy?

Historically, transfusions were administered to optimize oxygen delivery to organs in the presence of anemia. However, studies have highlighted the risks associated with transfusions, such as transfusion-related lung injury, circulatory overload, and increased nosocomial infections. These risks are particularly pronounced in critically ill patients, who are often more vulnerable to complications from any additional physiological burden.

The restrictive approach—typically recommended at a hemoglobin threshold of 7 to 8 g/dL—has been shown to be the safer alternative for most ICU patients, as highlighted in recently published clinical guidelines. The data supporting this approach suggest that a restrictive transfusion strategy not only spares patients unnecessary transfusions but also aligns with cost-effective and resource-efficient health care practices.

Key recommendations

For ICU providers, this guideline presents specific recommendations based on a patient’s condition:

• General critical illness: The restrictive approach is preferred over a permissive one, with no adverse effect on ICU mortality, one-year survival, or adverse events. In other words, lower Hgb thresholds do not correlate with poorer outcomes in most critically ill patients.

• Acute gastrointestinal bleeding: Evidence favors a restrictive approach, associated with reduced rebleeding risk and short-term mortality. Studies show a significantly lower incidence of transfusion reactions and costs without compromising patient safety.

• Acute coronary syndrome (ACS): A more cautious approach is advised here. In cases of ACS, a restrictive RBC transfusion strategy could potentially increase the risk of cardiac death. It is recommended to avoid a restrictive approach, as it remains unclear whether there is a gradient effect—where risk progressively increases below a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL—or a threshold effect at 10 g/dL. In other words, the data does not clarify if a hemoglobin level of 9 g/dL is as safe as 10 g/dL. An individualized transfusion approach, considering patient symptoms and other physiological markers, is recommended.

• Post-cardiac surgery: For postoperative patients, a restrictive strategy is suggested, as it conserves RBCs without impacting outcomes such as mortality or length of hospital stay.

• Isolated troponin elevation: In cases of elevated troponin without evidence of cardiac ischemia, transfusion decisions should consider additional patient-specific variables, with a restrictive approach as the baseline.

• Septic shock: RBC transfusions as part of a resuscitation bundle were not analyzed, as isolating the impact of RBC transfusions from other bundle elements was not feasible. However, with no clear benefit and similar adverse effects, neither strategy proved clinically superior. Nonetheless, a restrictive approach conserves RBC units, thereby saving resources and reducing costs.

The economics of restriction

Beyond clinical benefits, a restrictive approach conserves precious health care resources. With the cost of a single RBC unit hovering around $200—and significantly higher once administrative and logistic expenses are accounted for—reducing unnecessary transfusions translates into substantial savings. For a health care system already strained by limited blood supply and rising demand, a 40% reduction in transfusions across ICUs could alleviate supply pressures and contribute to more equitable resource distribution.

Easier said than done

Adopting a restrictive transfusion policy is not without challenges. Clinicians are trained to act decisively in critical situations, and, often, the instinct is to do more rather than less. However, studies indicate that with proper education, awareness, and decision-support systems, a restrictive policy is both feasible and effective. Institutions may consider behavior modification strategies, such as standardized transfusion order sets and decision-support tools within electronic medical records, to aid in adjusting transfusion practices.

Call to action

The message is clear: For most critically ill patients, a restrictive RBC transfusion strategy is not only safe but optimal. For ICU teams, this calls for a proactive shift in approach. It is a call to scrutinize transfusion triggers and lean toward a judicious, evidence-based approach.

While cases like ACS may require a different approach, the evidence strongly supports that, under most circumstances, less is more. Embracing this approach requires careful consideration, yet the potential benefits for patient safety and health care sustainability are compelling.

As critical care professionals, let us lead the way in refining transfusion practices to uphold patient safety, optimize resources, and adapt to evidence-based guidelines.

ACCESS THE FULL GUIDELINE

In the high-stakes environment of the intensive care unit (ICU), red blood cell (RBC) transfusions are a common intervention. With approximately 25% of critically ill patients in the US receiving RBC transfusions, optimizing the approach to transfusion is vital not only for patient safety but also for resource management. For the bedside clinician and health care systems, this presents both an opportunity and a challenge: to recalibrate transfusion practices while maintaining the highest standards of patient care.

Why a restrictive strategy?

Historically, transfusions were administered to optimize oxygen delivery to organs in the presence of anemia. However, studies have highlighted the risks associated with transfusions, such as transfusion-related lung injury, circulatory overload, and increased nosocomial infections. These risks are particularly pronounced in critically ill patients, who are often more vulnerable to complications from any additional physiological burden.

The restrictive approach—typically recommended at a hemoglobin threshold of 7 to 8 g/dL—has been shown to be the safer alternative for most ICU patients, as highlighted in recently published clinical guidelines. The data supporting this approach suggest that a restrictive transfusion strategy not only spares patients unnecessary transfusions but also aligns with cost-effective and resource-efficient health care practices.

Key recommendations

For ICU providers, this guideline presents specific recommendations based on a patient’s condition:

• General critical illness: The restrictive approach is preferred over a permissive one, with no adverse effect on ICU mortality, one-year survival, or adverse events. In other words, lower Hgb thresholds do not correlate with poorer outcomes in most critically ill patients.

• Acute gastrointestinal bleeding: Evidence favors a restrictive approach, associated with reduced rebleeding risk and short-term mortality. Studies show a significantly lower incidence of transfusion reactions and costs without compromising patient safety.

• Acute coronary syndrome (ACS): A more cautious approach is advised here. In cases of ACS, a restrictive RBC transfusion strategy could potentially increase the risk of cardiac death. It is recommended to avoid a restrictive approach, as it remains unclear whether there is a gradient effect—where risk progressively increases below a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL—or a threshold effect at 10 g/dL. In other words, the data does not clarify if a hemoglobin level of 9 g/dL is as safe as 10 g/dL. An individualized transfusion approach, considering patient symptoms and other physiological markers, is recommended.

• Post-cardiac surgery: For postoperative patients, a restrictive strategy is suggested, as it conserves RBCs without impacting outcomes such as mortality or length of hospital stay.

• Isolated troponin elevation: In cases of elevated troponin without evidence of cardiac ischemia, transfusion decisions should consider additional patient-specific variables, with a restrictive approach as the baseline.

• Septic shock: RBC transfusions as part of a resuscitation bundle were not analyzed, as isolating the impact of RBC transfusions from other bundle elements was not feasible. However, with no clear benefit and similar adverse effects, neither strategy proved clinically superior. Nonetheless, a restrictive approach conserves RBC units, thereby saving resources and reducing costs.

The economics of restriction

Beyond clinical benefits, a restrictive approach conserves precious health care resources. With the cost of a single RBC unit hovering around $200—and significantly higher once administrative and logistic expenses are accounted for—reducing unnecessary transfusions translates into substantial savings. For a health care system already strained by limited blood supply and rising demand, a 40% reduction in transfusions across ICUs could alleviate supply pressures and contribute to more equitable resource distribution.

Easier said than done

Adopting a restrictive transfusion policy is not without challenges. Clinicians are trained to act decisively in critical situations, and, often, the instinct is to do more rather than less. However, studies indicate that with proper education, awareness, and decision-support systems, a restrictive policy is both feasible and effective. Institutions may consider behavior modification strategies, such as standardized transfusion order sets and decision-support tools within electronic medical records, to aid in adjusting transfusion practices.

Call to action

The message is clear: For most critically ill patients, a restrictive RBC transfusion strategy is not only safe but optimal. For ICU teams, this calls for a proactive shift in approach. It is a call to scrutinize transfusion triggers and lean toward a judicious, evidence-based approach.

While cases like ACS may require a different approach, the evidence strongly supports that, under most circumstances, less is more. Embracing this approach requires careful consideration, yet the potential benefits for patient safety and health care sustainability are compelling.

As critical care professionals, let us lead the way in refining transfusion practices to uphold patient safety, optimize resources, and adapt to evidence-based guidelines.

ACCESS THE FULL GUIDELINE

DDSEP Plus Can Help You Achieve Your Educational Goals

Challenge yourself with these practice questions! This is just a sample of the nearly 900 questions available with an annual DDSEP Plus subscription. AGA member trainees receive a discounted subscription.

Purchase a subscription to continue learning.

Practice Question #1

A 45-year-old woman diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea presents to your clinic. Her diarrhea is well controlled with loperamide, but her abdominal pain persists.

Her primary care provider previously prescribed dicyclomine, but this did not improve her abdominal pain symptoms.

What is the next best medication to treat her abdominal pain?

A. Amitriptyline

B. Codeine/acetaminophen

C. Hydrocodone

D. Meloxicam

Correct answer:

A. Amitriptyline

Commentary:

Amitriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant medication that functions as a central neuromodulator. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of 6-12 weeks’ duration showed a modest improvement in global symptom relief and abdominal pain in patients with IBS treated with tricyclic anti-depressants. Opioid medications and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are not recommended to treat abdominal pain in patients with IBS.

Practice Question #2

A 52-year-old man with hypertension and diabetes mellitus type 2 is referred to you for 8 months of troublesome regurgitation and heartburn. He has a body mass index of 29 kg/m2.

He had minimal relief with single-dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy before breakfast and partial response with double-dose PPI therapy taken before breakfast and before dinner. Regurgitation after dinner and at bedtime is his most troublesome symptom.

What is the next best step in management?

A. Counsel on weight management

B. Increase PPI to quadruple dose

C. Perform gastric emptying study

D. Refer for bariatric surgery evaluation

E. Switch PPI to before bedtime

Correct answer:

A. Counsel on weight management

Commentary:

This presentation represents typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease that are not responsive to an optimized regimen of PPI therapy.

Management of refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms begins with optimizing lifestyle and weight loss.

Quadruple-dose PPI therapy has no established role. A gastric emptying study would be recommended if gastroparesis was suspected.

This patient does not meet criteria for bariatric surgery as his body mass index is less than 30 kg/m2.

PPI therapy optimization with before-meal dosing (30-60 min before breakfast for single-dose therapy and before breakfast and dinner for double-dose therapy) would be the next step after weight management.

Challenge yourself with these practice questions! This is just a sample of the nearly 900 questions available with an annual DDSEP Plus subscription. AGA member trainees receive a discounted subscription.

Purchase a subscription to continue learning.

Practice Question #1

A 45-year-old woman diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea presents to your clinic. Her diarrhea is well controlled with loperamide, but her abdominal pain persists.

Her primary care provider previously prescribed dicyclomine, but this did not improve her abdominal pain symptoms.

What is the next best medication to treat her abdominal pain?

A. Amitriptyline

B. Codeine/acetaminophen

C. Hydrocodone

D. Meloxicam

Correct answer:

A. Amitriptyline

Commentary:

Amitriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant medication that functions as a central neuromodulator. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of 6-12 weeks’ duration showed a modest improvement in global symptom relief and abdominal pain in patients with IBS treated with tricyclic anti-depressants. Opioid medications and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are not recommended to treat abdominal pain in patients with IBS.

Practice Question #2

A 52-year-old man with hypertension and diabetes mellitus type 2 is referred to you for 8 months of troublesome regurgitation and heartburn. He has a body mass index of 29 kg/m2.

He had minimal relief with single-dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy before breakfast and partial response with double-dose PPI therapy taken before breakfast and before dinner. Regurgitation after dinner and at bedtime is his most troublesome symptom.

What is the next best step in management?

A. Counsel on weight management

B. Increase PPI to quadruple dose

C. Perform gastric emptying study

D. Refer for bariatric surgery evaluation

E. Switch PPI to before bedtime

Correct answer:

A. Counsel on weight management

Commentary:

This presentation represents typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease that are not responsive to an optimized regimen of PPI therapy.

Management of refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms begins with optimizing lifestyle and weight loss.

Quadruple-dose PPI therapy has no established role. A gastric emptying study would be recommended if gastroparesis was suspected.

This patient does not meet criteria for bariatric surgery as his body mass index is less than 30 kg/m2.

PPI therapy optimization with before-meal dosing (30-60 min before breakfast for single-dose therapy and before breakfast and dinner for double-dose therapy) would be the next step after weight management.

Challenge yourself with these practice questions! This is just a sample of the nearly 900 questions available with an annual DDSEP Plus subscription. AGA member trainees receive a discounted subscription.

Purchase a subscription to continue learning.

Practice Question #1

A 45-year-old woman diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea presents to your clinic. Her diarrhea is well controlled with loperamide, but her abdominal pain persists.

Her primary care provider previously prescribed dicyclomine, but this did not improve her abdominal pain symptoms.

What is the next best medication to treat her abdominal pain?

A. Amitriptyline

B. Codeine/acetaminophen

C. Hydrocodone

D. Meloxicam

Correct answer:

A. Amitriptyline

Commentary:

Amitriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant medication that functions as a central neuromodulator. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of 6-12 weeks’ duration showed a modest improvement in global symptom relief and abdominal pain in patients with IBS treated with tricyclic anti-depressants. Opioid medications and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are not recommended to treat abdominal pain in patients with IBS.

Practice Question #2

A 52-year-old man with hypertension and diabetes mellitus type 2 is referred to you for 8 months of troublesome regurgitation and heartburn. He has a body mass index of 29 kg/m2.

He had minimal relief with single-dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy before breakfast and partial response with double-dose PPI therapy taken before breakfast and before dinner. Regurgitation after dinner and at bedtime is his most troublesome symptom.

What is the next best step in management?

A. Counsel on weight management

B. Increase PPI to quadruple dose

C. Perform gastric emptying study

D. Refer for bariatric surgery evaluation

E. Switch PPI to before bedtime

Correct answer:

A. Counsel on weight management

Commentary:

This presentation represents typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease that are not responsive to an optimized regimen of PPI therapy.

Management of refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms begins with optimizing lifestyle and weight loss.

Quadruple-dose PPI therapy has no established role. A gastric emptying study would be recommended if gastroparesis was suspected.

This patient does not meet criteria for bariatric surgery as his body mass index is less than 30 kg/m2.

PPI therapy optimization with before-meal dosing (30-60 min before breakfast for single-dose therapy and before breakfast and dinner for double-dose therapy) would be the next step after weight management.

AGA Research Foundation: You Can Help

To my fellow AGA Members, I’m not the first to tell you that real progress in the diagnosis, treatment, and cure of digestive disease is at risk. Research funding from traditional sources, like the National Institutes of Health, continues to shrink. We can expect even greater cuts on the horizon.

GI investigators in the early stages of their careers are particularly hard hit. They are finding it much more difficult to secure needed federal funding. As a result, many of these investigators are walking away from GI research frustrated by a lack of support.

It is our hope that physicians have an abundance of new tools and treatments to care for their patients suffering from digestive disorders.

You know that research has revolutionized the care of many digestive disease patients. These patients, as well as everyone in the GI field clinicians and researchers alike, have benefited from the discoveries of passionate investigators, past and present.

This is where you can help.

New treatments and devices are the result of years of research. The AGA Research Foundation grants are critical to continuing the GI pipeline.

Help us fund more researchers by supporting the AGA Research Foundation with a year-end donation. Your donation will support young investigators’ research careers and help assure research is continued.

Be gracious, generous and giving to the future of the GI specialty this holiday season. There are three easy ways to give:

Make a tax-deductible donation online at www. foundation.gastro.org.

Send a donation through the mail to:

AGA Research Foundation

4930 Del Ray Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20814

Or donate over the phone by calling (301) 222-4002. All gifts are tax-deductible to the fullest extent of US law. Join us!

Dr. Camilleri is AGA Research Foundation Chair and Past AGA Institute President. He is a consultant in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

To my fellow AGA Members, I’m not the first to tell you that real progress in the diagnosis, treatment, and cure of digestive disease is at risk. Research funding from traditional sources, like the National Institutes of Health, continues to shrink. We can expect even greater cuts on the horizon.

GI investigators in the early stages of their careers are particularly hard hit. They are finding it much more difficult to secure needed federal funding. As a result, many of these investigators are walking away from GI research frustrated by a lack of support.

It is our hope that physicians have an abundance of new tools and treatments to care for their patients suffering from digestive disorders.

You know that research has revolutionized the care of many digestive disease patients. These patients, as well as everyone in the GI field clinicians and researchers alike, have benefited from the discoveries of passionate investigators, past and present.

This is where you can help.

New treatments and devices are the result of years of research. The AGA Research Foundation grants are critical to continuing the GI pipeline.

Help us fund more researchers by supporting the AGA Research Foundation with a year-end donation. Your donation will support young investigators’ research careers and help assure research is continued.

Be gracious, generous and giving to the future of the GI specialty this holiday season. There are three easy ways to give:

Make a tax-deductible donation online at www. foundation.gastro.org.

Send a donation through the mail to:

AGA Research Foundation

4930 Del Ray Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20814

Or donate over the phone by calling (301) 222-4002. All gifts are tax-deductible to the fullest extent of US law. Join us!

Dr. Camilleri is AGA Research Foundation Chair and Past AGA Institute President. He is a consultant in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

To my fellow AGA Members, I’m not the first to tell you that real progress in the diagnosis, treatment, and cure of digestive disease is at risk. Research funding from traditional sources, like the National Institutes of Health, continues to shrink. We can expect even greater cuts on the horizon.

GI investigators in the early stages of their careers are particularly hard hit. They are finding it much more difficult to secure needed federal funding. As a result, many of these investigators are walking away from GI research frustrated by a lack of support.

It is our hope that physicians have an abundance of new tools and treatments to care for their patients suffering from digestive disorders.

You know that research has revolutionized the care of many digestive disease patients. These patients, as well as everyone in the GI field clinicians and researchers alike, have benefited from the discoveries of passionate investigators, past and present.

This is where you can help.

New treatments and devices are the result of years of research. The AGA Research Foundation grants are critical to continuing the GI pipeline.

Help us fund more researchers by supporting the AGA Research Foundation with a year-end donation. Your donation will support young investigators’ research careers and help assure research is continued.

Be gracious, generous and giving to the future of the GI specialty this holiday season. There are three easy ways to give:

Make a tax-deductible donation online at www. foundation.gastro.org.

Send a donation through the mail to:

AGA Research Foundation

4930 Del Ray Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20814

Or donate over the phone by calling (301) 222-4002. All gifts are tax-deductible to the fullest extent of US law. Join us!

Dr. Camilleri is AGA Research Foundation Chair and Past AGA Institute President. He is a consultant in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

Unlock the Latest Clinical Updates with the 2024 PG Course OnDemand

Did you miss out on the AGA Postgraduate Course this year?

Visit agau.gastro.org to purchase today for flexible, on-the-go access to the latest clinical advances in the GI field.

- Unparalleled access: Choose when and where you dive into content with convenient access from any computer or mobile device.

- Incredible faculty: Learn from renowned experts who will offer their perspectives on cutting-edge research and clinical guidance.

- Tangible strategies: Expert and early career faculty will guide you through challenging patient cases and provide strategies you can easily implement upon your return to the office.

- Efficient learning: Content is organized by category: GI oncology, neurogastroenterology & motility, obesity, advanced endoscopy, and liver.

- Continuing education: With CME testing integrated directly into each session, you can easily earn up to 16 CME and MOC credits through December 31, 2024.

Did you miss out on the AGA Postgraduate Course this year?

Visit agau.gastro.org to purchase today for flexible, on-the-go access to the latest clinical advances in the GI field.

- Unparalleled access: Choose when and where you dive into content with convenient access from any computer or mobile device.

- Incredible faculty: Learn from renowned experts who will offer their perspectives on cutting-edge research and clinical guidance.

- Tangible strategies: Expert and early career faculty will guide you through challenging patient cases and provide strategies you can easily implement upon your return to the office.

- Efficient learning: Content is organized by category: GI oncology, neurogastroenterology & motility, obesity, advanced endoscopy, and liver.

- Continuing education: With CME testing integrated directly into each session, you can easily earn up to 16 CME and MOC credits through December 31, 2024.

Did you miss out on the AGA Postgraduate Course this year?

Visit agau.gastro.org to purchase today for flexible, on-the-go access to the latest clinical advances in the GI field.

- Unparalleled access: Choose when and where you dive into content with convenient access from any computer or mobile device.

- Incredible faculty: Learn from renowned experts who will offer their perspectives on cutting-edge research and clinical guidance.

- Tangible strategies: Expert and early career faculty will guide you through challenging patient cases and provide strategies you can easily implement upon your return to the office.

- Efficient learning: Content is organized by category: GI oncology, neurogastroenterology & motility, obesity, advanced endoscopy, and liver.

- Continuing education: With CME testing integrated directly into each session, you can easily earn up to 16 CME and MOC credits through December 31, 2024.

Revival of the aspiration vs chest tube debate for PSP

Thoracic Oncology and Chest Procedures Network

Pleural Disease Section

Considerable heterogeneity exists in the management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP). American and European guidelines have been grappling with this question for decades: What is the best way to manage PSP? A 2023 randomized, controlled trial (Marx et al. AJRCCM) sought to answer this.

The study recruited 379 adults aged 18 to 55 years between 2009 and 2015, with complete and first PSP in 31 French hospitals. One hundred eighty-nine patients initially received simple aspiration and 190 received chest tube drainage. The aspiration device was removed if a chest radiograph (CXR) following 30 minutes of aspiration showed lung apposition, with suction repeated up to one time with incomplete re-expansion. The chest tubes were large-bore (16-F or 20-F) and removed 72 hours postprocedure if the CXR showed complete lung re-expansion.

Simple aspiration was statistically inferior to chest tube drainage (29% vs 18%). However, first-line simple aspiration resulted in shorter length of stay, less subcutaneous emphysema, site infection, pain, and one-year recurrence.

Since most first-time PSP occurs in younger, healthier adults, simple aspiration could still be considered as it is better tolerated than large-bore chest tubes. However, with more frequent use of small-bore (≤14-F) catheters, ambulatory drainage could also be a suitable option in carefully selected patients. Additionally, inpatient chest tubes do not need to remain in place for 72 hours, as was this study’s protocol. Society guidelines will need to weigh in on the latest high-quality evidence available for final recommendations.

Thoracic Oncology and Chest Procedures Network

Pleural Disease Section

Considerable heterogeneity exists in the management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP). American and European guidelines have been grappling with this question for decades: What is the best way to manage PSP? A 2023 randomized, controlled trial (Marx et al. AJRCCM) sought to answer this.

The study recruited 379 adults aged 18 to 55 years between 2009 and 2015, with complete and first PSP in 31 French hospitals. One hundred eighty-nine patients initially received simple aspiration and 190 received chest tube drainage. The aspiration device was removed if a chest radiograph (CXR) following 30 minutes of aspiration showed lung apposition, with suction repeated up to one time with incomplete re-expansion. The chest tubes were large-bore (16-F or 20-F) and removed 72 hours postprocedure if the CXR showed complete lung re-expansion.

Simple aspiration was statistically inferior to chest tube drainage (29% vs 18%). However, first-line simple aspiration resulted in shorter length of stay, less subcutaneous emphysema, site infection, pain, and one-year recurrence.

Since most first-time PSP occurs in younger, healthier adults, simple aspiration could still be considered as it is better tolerated than large-bore chest tubes. However, with more frequent use of small-bore (≤14-F) catheters, ambulatory drainage could also be a suitable option in carefully selected patients. Additionally, inpatient chest tubes do not need to remain in place for 72 hours, as was this study’s protocol. Society guidelines will need to weigh in on the latest high-quality evidence available for final recommendations.

Thoracic Oncology and Chest Procedures Network

Pleural Disease Section

Considerable heterogeneity exists in the management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP). American and European guidelines have been grappling with this question for decades: What is the best way to manage PSP? A 2023 randomized, controlled trial (Marx et al. AJRCCM) sought to answer this.

The study recruited 379 adults aged 18 to 55 years between 2009 and 2015, with complete and first PSP in 31 French hospitals. One hundred eighty-nine patients initially received simple aspiration and 190 received chest tube drainage. The aspiration device was removed if a chest radiograph (CXR) following 30 minutes of aspiration showed lung apposition, with suction repeated up to one time with incomplete re-expansion. The chest tubes were large-bore (16-F or 20-F) and removed 72 hours postprocedure if the CXR showed complete lung re-expansion.

Simple aspiration was statistically inferior to chest tube drainage (29% vs 18%). However, first-line simple aspiration resulted in shorter length of stay, less subcutaneous emphysema, site infection, pain, and one-year recurrence.

Since most first-time PSP occurs in younger, healthier adults, simple aspiration could still be considered as it is better tolerated than large-bore chest tubes. However, with more frequent use of small-bore (≤14-F) catheters, ambulatory drainage could also be a suitable option in carefully selected patients. Additionally, inpatient chest tubes do not need to remain in place for 72 hours, as was this study’s protocol. Society guidelines will need to weigh in on the latest high-quality evidence available for final recommendations.

AI applications in pediatric pulmonary, sleep, and critical care medicine

Airways Disorders Network

Pediatric Chest Medicine Section

Artificial intelligence (AI) refers to the science and engineering of making intelligent machines that mimic human cognitive functions, such as learning and problem solving.1 Asthma exacerbations in young children were detected reliably by AI-aided stethoscope alone.2 Inhaler use has been successfully tracked using active and passive patient input to cloud-based dashboards.3 Asthma specialists can potentially use this knowledge to intervene in real time or more frequent intervals than the current episodic care.

Sleep trackers using commercial-grade sensors can provide useful information about sleep hygiene, sleep duration, and nocturnal awakenings. An increasing number of “wearables” and “nearables” that utilize AI algorithms to evaluate sleep duration and quality are FDA approved. AI-based scoring of polysomnography data can improve the efficiency of a sleep laboratory. Big data analysis of CPAP compliance in children led to identification of actionable items that can be targeted to improve patient outcomes.4

The use of AI models in clinical decision support can result in fewer false alerts and missed patients due to increased model accuracy. Additionally, large language model tools can automatically generate comprehensive progress notes incorporating relevant electronic medical records data, thereby reducing physician charting time.

These case uses highlight the potential to improve workflow efficiency and clinical outcomes in pediatric pulmonary and critical care by incorporating AI tools in medical decision-making and management.

References