User login

Eight things hospitalists need to know about post-acute care

Whether you’re a hospitalist who works only in a hospital, a hospitalist who works only in a post-acute care (PAC) setting, or a hospitalist who works in both types of facilities, knowing about current trends at PAC facilities and what the future may hold can help you excel in your current capacity and, ultimately, improve patient care.

The Hospitalist tapped experts in the post-acute space to tell us what they thought HM should know about working in PAC – which, in many ways, is quite different from the hospital setting. Here’s a compilation of their top eight must-knows.

1. PAC settings rely more on mid-level medical staff than hospitals do.

PAC facilities employ more mid-level providers, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, because they can support the level of medical complexity and decision making 95% of the time, says James D. Tollman, MD, FHM, president of Essex Inpatient Physicians in Boxford, Mass. Further, they are more heavily staffed by licensed practical nurses than are acute-care settings.

Usually, there is no physician or nurse practitioner presence at night. Clinicians rely on nursing staff’s assessment to make decisions regarding changes in patient status during off-hours, says Virginia Cummings, MD, director of long-term care, gerontology division, at Boston-based Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

2. Testing takes longer, and options are limited.

Access to some acute urgent resources such as laboratory testing, imaging tests, and pharmacy products is more challenging at PAC facilities because most of these resources are not on-site. Consequently, there is a time lag between ordering tests and new medications and implementing these orders.

“If a patient needs something performed diagnostically immediately, they usually have to be transported to the emergency room or a facility with the necessary testing equipment,” Dr. Tollman says.

However, Paul T. Liistro, managing partner, Arbors of Hop Brook Limited Partnership in Manchester, Conn., and Vernon Manor Health Care Center in Vernon, Conn., and administrator, Manchester Manor Health Care Center, notes that it’s possible for a laboratory service or mobile diagnostic unit to provide laboratory testing or certain imaging at a PAC facility. More-involved diagnostics, such as an MRI or a PET scan, typically require testing at a remote location.

3. Patient populations mainly include rehab and terminally ill patients.

Patients are typically sent to a PAC facility either to recover from an illness or injury or because they are chronically ill and have exhausted treatment options. Regarding the latter, “They are mostly there for palliation; we don’t perform daily tests or prescribe aggressive medications on these patients,” Dr. Nazir says.

Dr. Cummings explains that PAC clinicians go through “the dying process with the patient.”

“They may or may not have assistance from hospice organizations,” she says, “and when they don’t, [hospitalists] take on the role of palliative-care providers.”

Dr. Cummings has seen an increase in psychiatric patients entering PAC facilities.

“Many patients with chronic psychological problems are aging, and there are fewer inpatient psychiatric beds available to those with concurrent medical and psychiatric problems,” she says. Much of this work is now being done in PAC settings.

4. You can build a relationship with your patient.

Because the pace of a PAC facility is slower and a patient typically stays in a PAC facility longer than at a hospital, there’s time for a hospitalist to have more in-depth conversations with patients and their families.

“Building a deeper relationship with a patient may give the hospitalist an opportunity to discover the cause of an acute problem,” Dr. Nazir says. “They can go in-depth into the psychosocial aspect of medicine and may be able to find out what led to the initial problem and the real root cause, which can help prevent future recurrences, such as repeat falls or forgetting to take a medication.”

5. Using EHRs can improve transitions.

Care transitions between a hospital and PAC facility can be compromised by a lack of information sharing, and they can affect the quality and safety of patient care, says Dori Cross, a doctoral candidate in health services organization and policy at the University of Michigan School of Public Health in Ann Arbor. Handoffs between providers require information continuity – information that is complete, timely, and in a usable format – to ensure appropriate medical decisions and to provide high-quality care during and after transition.

Electronic health records (EHRs) as well as health information exchanges (HIEs) allow providers to communicate and share patient information. For example, hospitals can send information electronically to PAC facilities (“push” exchange) or make information available online securely for PAC providers to log in and access (“pull” exchange). According to a 2014 survey data by the American Hospital Association, more than 50% of hospitals report sending structured summary-of-care records electronically to long-term care settings; a little less than half of those hospitals (23% of the total sample of hospitals) were also receiving information electronically from long-term care sites.1

“This bidirectional exchange, in particular, can make it easier to share information across provider organizations electronically and, in turn, improve care delivery,” says Ms. Cross, who authored an accepted paper on the subject in the Journal of Post-Acute and Long-Term Medicine.

6. Hospitalists can work with providers in PAC settings to improve transitions.

Despite improvements in the electronic transfer of medical information, gaps still exist and can cause problems. One chasm when discharging patients to a PAC facility, is when a hospital IT system is incapable of communicating with the PAC facility system. In this instance, Dr. Nazir says, the hospitalist “can help bridge the gap.”

“[We] can verbally relay relevant information to physicians at PAC facilities so they understand the patient’s status, needs, and expectations,” he says. “Furthermore, hospitalists and a PAC facility’s administration can brainstorm methods to improve the systems of care so the patient receives more effective and timely care.”

7. Hospitalists switching to the PAC setting should have formal training.

The two main obstacles for hospitalists who change from working in a hospital to a PAC facility are the lack of exposure to PAC work in training and the assumption that it requires the same skills sets of a typical hospitalist, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Los Angeles–based Agilon Health. The PAC setting has quite a number of differences compared with a hospital setting. For example, some regulations apply specifically to PAC facilities. In addition to formal training, hospitalists can benefit from using SHM’s Post-Acute Care Transitions Toolkit, having a mentor, or using resources from other organizations that function in this space such as The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine, Dr. Nazir says.

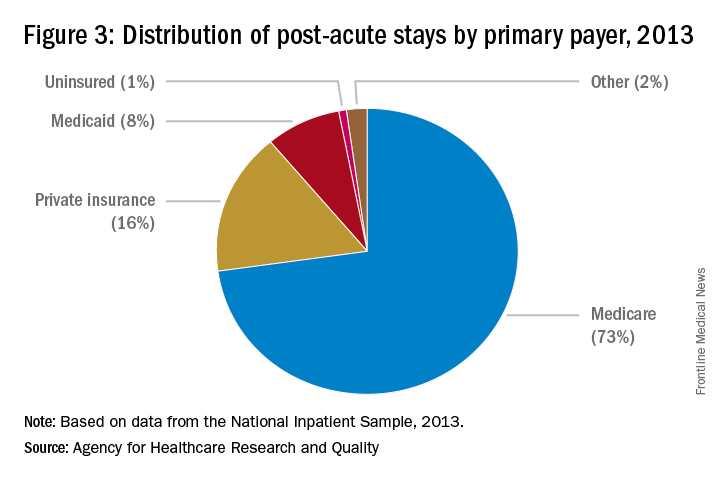

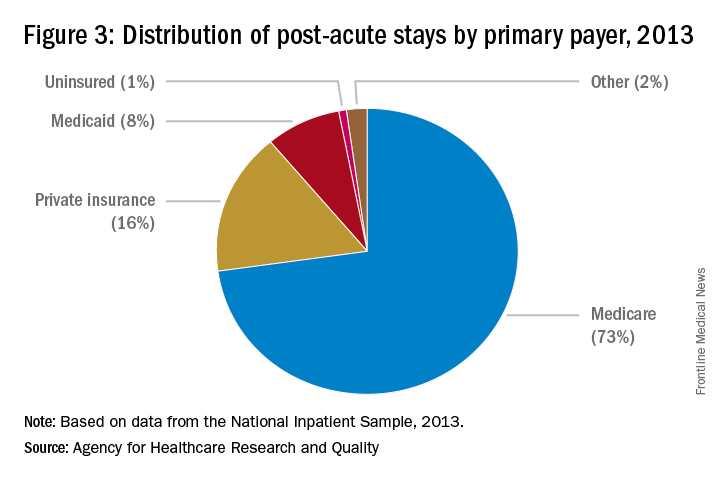

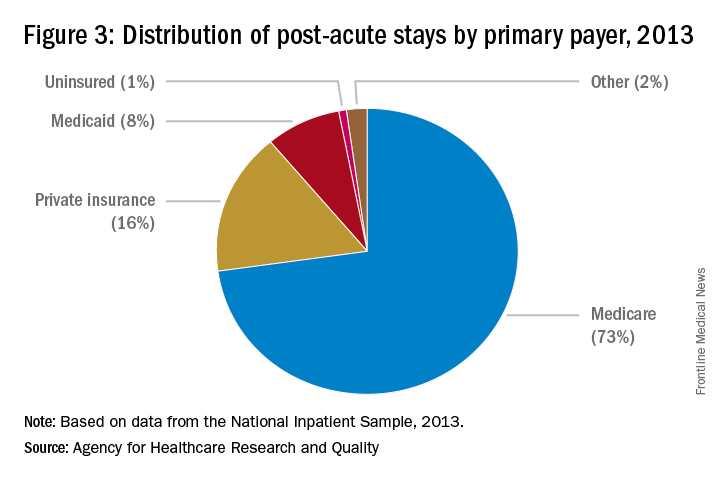

8. A variety of payors and payment models are in play.

Commercial insurers continue to be major payors for PAC, especially for individuals younger than 65 years. Medicare and Medicaid, administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, are the primary payors for patients aged 65 years and older.

“These scorecards are using a variety of criteria to rank providers, such as length of stay, cost, readmissions to hospitals, and quality.”

Because Medicare Part A covers many patients discharged to a PAC setting, any changes in payment incentives or benefit structures by the Medicare program will drive changes in PAC.

“For example, as Medicare implements payment adjustments for hospitals that have high rates of readmissions, hospitals have a new incentive to work closely with SNFs and other providers of PAC to ensure patients can avoid unnecessary readmissions,” says Tiffany A. Radcliff, PhD, a health economist and associate professor in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station.

Providers must follow the billing rules for each payor. The rules for Medicare payments are outlined on CMS’ website. Bundled payments for PAC under the Medicare Part A program are scheduled to be implemented by 2018.

Reference

Cross DA, Adler-Milstein J. Investing in post-acute care transitions: electronic information exchange between hospitals and long-term care facilities [published online ahead of print Sept. 14, 2016]. JAMDA. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.07.024.

Whether you’re a hospitalist who works only in a hospital, a hospitalist who works only in a post-acute care (PAC) setting, or a hospitalist who works in both types of facilities, knowing about current trends at PAC facilities and what the future may hold can help you excel in your current capacity and, ultimately, improve patient care.

The Hospitalist tapped experts in the post-acute space to tell us what they thought HM should know about working in PAC – which, in many ways, is quite different from the hospital setting. Here’s a compilation of their top eight must-knows.

1. PAC settings rely more on mid-level medical staff than hospitals do.

PAC facilities employ more mid-level providers, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, because they can support the level of medical complexity and decision making 95% of the time, says James D. Tollman, MD, FHM, president of Essex Inpatient Physicians in Boxford, Mass. Further, they are more heavily staffed by licensed practical nurses than are acute-care settings.

Usually, there is no physician or nurse practitioner presence at night. Clinicians rely on nursing staff’s assessment to make decisions regarding changes in patient status during off-hours, says Virginia Cummings, MD, director of long-term care, gerontology division, at Boston-based Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

2. Testing takes longer, and options are limited.

Access to some acute urgent resources such as laboratory testing, imaging tests, and pharmacy products is more challenging at PAC facilities because most of these resources are not on-site. Consequently, there is a time lag between ordering tests and new medications and implementing these orders.

“If a patient needs something performed diagnostically immediately, they usually have to be transported to the emergency room or a facility with the necessary testing equipment,” Dr. Tollman says.

However, Paul T. Liistro, managing partner, Arbors of Hop Brook Limited Partnership in Manchester, Conn., and Vernon Manor Health Care Center in Vernon, Conn., and administrator, Manchester Manor Health Care Center, notes that it’s possible for a laboratory service or mobile diagnostic unit to provide laboratory testing or certain imaging at a PAC facility. More-involved diagnostics, such as an MRI or a PET scan, typically require testing at a remote location.

3. Patient populations mainly include rehab and terminally ill patients.

Patients are typically sent to a PAC facility either to recover from an illness or injury or because they are chronically ill and have exhausted treatment options. Regarding the latter, “They are mostly there for palliation; we don’t perform daily tests or prescribe aggressive medications on these patients,” Dr. Nazir says.

Dr. Cummings explains that PAC clinicians go through “the dying process with the patient.”

“They may or may not have assistance from hospice organizations,” she says, “and when they don’t, [hospitalists] take on the role of palliative-care providers.”

Dr. Cummings has seen an increase in psychiatric patients entering PAC facilities.

“Many patients with chronic psychological problems are aging, and there are fewer inpatient psychiatric beds available to those with concurrent medical and psychiatric problems,” she says. Much of this work is now being done in PAC settings.

4. You can build a relationship with your patient.

Because the pace of a PAC facility is slower and a patient typically stays in a PAC facility longer than at a hospital, there’s time for a hospitalist to have more in-depth conversations with patients and their families.

“Building a deeper relationship with a patient may give the hospitalist an opportunity to discover the cause of an acute problem,” Dr. Nazir says. “They can go in-depth into the psychosocial aspect of medicine and may be able to find out what led to the initial problem and the real root cause, which can help prevent future recurrences, such as repeat falls or forgetting to take a medication.”

5. Using EHRs can improve transitions.

Care transitions between a hospital and PAC facility can be compromised by a lack of information sharing, and they can affect the quality and safety of patient care, says Dori Cross, a doctoral candidate in health services organization and policy at the University of Michigan School of Public Health in Ann Arbor. Handoffs between providers require information continuity – information that is complete, timely, and in a usable format – to ensure appropriate medical decisions and to provide high-quality care during and after transition.

Electronic health records (EHRs) as well as health information exchanges (HIEs) allow providers to communicate and share patient information. For example, hospitals can send information electronically to PAC facilities (“push” exchange) or make information available online securely for PAC providers to log in and access (“pull” exchange). According to a 2014 survey data by the American Hospital Association, more than 50% of hospitals report sending structured summary-of-care records electronically to long-term care settings; a little less than half of those hospitals (23% of the total sample of hospitals) were also receiving information electronically from long-term care sites.1

“This bidirectional exchange, in particular, can make it easier to share information across provider organizations electronically and, in turn, improve care delivery,” says Ms. Cross, who authored an accepted paper on the subject in the Journal of Post-Acute and Long-Term Medicine.

6. Hospitalists can work with providers in PAC settings to improve transitions.

Despite improvements in the electronic transfer of medical information, gaps still exist and can cause problems. One chasm when discharging patients to a PAC facility, is when a hospital IT system is incapable of communicating with the PAC facility system. In this instance, Dr. Nazir says, the hospitalist “can help bridge the gap.”

“[We] can verbally relay relevant information to physicians at PAC facilities so they understand the patient’s status, needs, and expectations,” he says. “Furthermore, hospitalists and a PAC facility’s administration can brainstorm methods to improve the systems of care so the patient receives more effective and timely care.”

7. Hospitalists switching to the PAC setting should have formal training.

The two main obstacles for hospitalists who change from working in a hospital to a PAC facility are the lack of exposure to PAC work in training and the assumption that it requires the same skills sets of a typical hospitalist, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Los Angeles–based Agilon Health. The PAC setting has quite a number of differences compared with a hospital setting. For example, some regulations apply specifically to PAC facilities. In addition to formal training, hospitalists can benefit from using SHM’s Post-Acute Care Transitions Toolkit, having a mentor, or using resources from other organizations that function in this space such as The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine, Dr. Nazir says.

8. A variety of payors and payment models are in play.

Commercial insurers continue to be major payors for PAC, especially for individuals younger than 65 years. Medicare and Medicaid, administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, are the primary payors for patients aged 65 years and older.

“These scorecards are using a variety of criteria to rank providers, such as length of stay, cost, readmissions to hospitals, and quality.”

Because Medicare Part A covers many patients discharged to a PAC setting, any changes in payment incentives or benefit structures by the Medicare program will drive changes in PAC.

“For example, as Medicare implements payment adjustments for hospitals that have high rates of readmissions, hospitals have a new incentive to work closely with SNFs and other providers of PAC to ensure patients can avoid unnecessary readmissions,” says Tiffany A. Radcliff, PhD, a health economist and associate professor in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station.

Providers must follow the billing rules for each payor. The rules for Medicare payments are outlined on CMS’ website. Bundled payments for PAC under the Medicare Part A program are scheduled to be implemented by 2018.

Reference

Cross DA, Adler-Milstein J. Investing in post-acute care transitions: electronic information exchange between hospitals and long-term care facilities [published online ahead of print Sept. 14, 2016]. JAMDA. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.07.024.

Whether you’re a hospitalist who works only in a hospital, a hospitalist who works only in a post-acute care (PAC) setting, or a hospitalist who works in both types of facilities, knowing about current trends at PAC facilities and what the future may hold can help you excel in your current capacity and, ultimately, improve patient care.

The Hospitalist tapped experts in the post-acute space to tell us what they thought HM should know about working in PAC – which, in many ways, is quite different from the hospital setting. Here’s a compilation of their top eight must-knows.

1. PAC settings rely more on mid-level medical staff than hospitals do.

PAC facilities employ more mid-level providers, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, because they can support the level of medical complexity and decision making 95% of the time, says James D. Tollman, MD, FHM, president of Essex Inpatient Physicians in Boxford, Mass. Further, they are more heavily staffed by licensed practical nurses than are acute-care settings.

Usually, there is no physician or nurse practitioner presence at night. Clinicians rely on nursing staff’s assessment to make decisions regarding changes in patient status during off-hours, says Virginia Cummings, MD, director of long-term care, gerontology division, at Boston-based Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

2. Testing takes longer, and options are limited.

Access to some acute urgent resources such as laboratory testing, imaging tests, and pharmacy products is more challenging at PAC facilities because most of these resources are not on-site. Consequently, there is a time lag between ordering tests and new medications and implementing these orders.

“If a patient needs something performed diagnostically immediately, they usually have to be transported to the emergency room or a facility with the necessary testing equipment,” Dr. Tollman says.

However, Paul T. Liistro, managing partner, Arbors of Hop Brook Limited Partnership in Manchester, Conn., and Vernon Manor Health Care Center in Vernon, Conn., and administrator, Manchester Manor Health Care Center, notes that it’s possible for a laboratory service or mobile diagnostic unit to provide laboratory testing or certain imaging at a PAC facility. More-involved diagnostics, such as an MRI or a PET scan, typically require testing at a remote location.

3. Patient populations mainly include rehab and terminally ill patients.

Patients are typically sent to a PAC facility either to recover from an illness or injury or because they are chronically ill and have exhausted treatment options. Regarding the latter, “They are mostly there for palliation; we don’t perform daily tests or prescribe aggressive medications on these patients,” Dr. Nazir says.

Dr. Cummings explains that PAC clinicians go through “the dying process with the patient.”

“They may or may not have assistance from hospice organizations,” she says, “and when they don’t, [hospitalists] take on the role of palliative-care providers.”

Dr. Cummings has seen an increase in psychiatric patients entering PAC facilities.

“Many patients with chronic psychological problems are aging, and there are fewer inpatient psychiatric beds available to those with concurrent medical and psychiatric problems,” she says. Much of this work is now being done in PAC settings.

4. You can build a relationship with your patient.

Because the pace of a PAC facility is slower and a patient typically stays in a PAC facility longer than at a hospital, there’s time for a hospitalist to have more in-depth conversations with patients and their families.

“Building a deeper relationship with a patient may give the hospitalist an opportunity to discover the cause of an acute problem,” Dr. Nazir says. “They can go in-depth into the psychosocial aspect of medicine and may be able to find out what led to the initial problem and the real root cause, which can help prevent future recurrences, such as repeat falls or forgetting to take a medication.”

5. Using EHRs can improve transitions.

Care transitions between a hospital and PAC facility can be compromised by a lack of information sharing, and they can affect the quality and safety of patient care, says Dori Cross, a doctoral candidate in health services organization and policy at the University of Michigan School of Public Health in Ann Arbor. Handoffs between providers require information continuity – information that is complete, timely, and in a usable format – to ensure appropriate medical decisions and to provide high-quality care during and after transition.

Electronic health records (EHRs) as well as health information exchanges (HIEs) allow providers to communicate and share patient information. For example, hospitals can send information electronically to PAC facilities (“push” exchange) or make information available online securely for PAC providers to log in and access (“pull” exchange). According to a 2014 survey data by the American Hospital Association, more than 50% of hospitals report sending structured summary-of-care records electronically to long-term care settings; a little less than half of those hospitals (23% of the total sample of hospitals) were also receiving information electronically from long-term care sites.1

“This bidirectional exchange, in particular, can make it easier to share information across provider organizations electronically and, in turn, improve care delivery,” says Ms. Cross, who authored an accepted paper on the subject in the Journal of Post-Acute and Long-Term Medicine.

6. Hospitalists can work with providers in PAC settings to improve transitions.

Despite improvements in the electronic transfer of medical information, gaps still exist and can cause problems. One chasm when discharging patients to a PAC facility, is when a hospital IT system is incapable of communicating with the PAC facility system. In this instance, Dr. Nazir says, the hospitalist “can help bridge the gap.”

“[We] can verbally relay relevant information to physicians at PAC facilities so they understand the patient’s status, needs, and expectations,” he says. “Furthermore, hospitalists and a PAC facility’s administration can brainstorm methods to improve the systems of care so the patient receives more effective and timely care.”

7. Hospitalists switching to the PAC setting should have formal training.

The two main obstacles for hospitalists who change from working in a hospital to a PAC facility are the lack of exposure to PAC work in training and the assumption that it requires the same skills sets of a typical hospitalist, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Los Angeles–based Agilon Health. The PAC setting has quite a number of differences compared with a hospital setting. For example, some regulations apply specifically to PAC facilities. In addition to formal training, hospitalists can benefit from using SHM’s Post-Acute Care Transitions Toolkit, having a mentor, or using resources from other organizations that function in this space such as The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine, Dr. Nazir says.

8. A variety of payors and payment models are in play.

Commercial insurers continue to be major payors for PAC, especially for individuals younger than 65 years. Medicare and Medicaid, administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, are the primary payors for patients aged 65 years and older.

“These scorecards are using a variety of criteria to rank providers, such as length of stay, cost, readmissions to hospitals, and quality.”

Because Medicare Part A covers many patients discharged to a PAC setting, any changes in payment incentives or benefit structures by the Medicare program will drive changes in PAC.

“For example, as Medicare implements payment adjustments for hospitals that have high rates of readmissions, hospitals have a new incentive to work closely with SNFs and other providers of PAC to ensure patients can avoid unnecessary readmissions,” says Tiffany A. Radcliff, PhD, a health economist and associate professor in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station.

Providers must follow the billing rules for each payor. The rules for Medicare payments are outlined on CMS’ website. Bundled payments for PAC under the Medicare Part A program are scheduled to be implemented by 2018.

Reference

Cross DA, Adler-Milstein J. Investing in post-acute care transitions: electronic information exchange between hospitals and long-term care facilities [published online ahead of print Sept. 14, 2016]. JAMDA. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.07.024.

LISTEN NOW: Scott Sears, MD, Discusses Hospitalist Challenges with Unassigned, Uninsured Patients

Risk Adjusting Readmissions: Coming Soon?

Nearly three-quarters of hospitals will be receiving penalties from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2016 for excess readmissions, having failed to prevent enough patients from returning to the hospital 30 days post-discharge. With so many hospitals impacted by penalties, it is understandable that the underlying methodology of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) is coming under intense scrutiny.

Research published in JAMA Internal Medicine in September hit upon many of the myriad factors—often outside of the hospital or providers’ control—that influence whether a patient is readmitted to the hospital. This information adds weight to criticism of the measures included in the HRRP and asserts the need to refine or reform the measures to better account for readmissions preventable through the interventions of the healthcare system. The behavior these measures are meant to curb, including poor quality care, inadequate access to follow-up or medications, and gaps in transitions of care, are not identifiable within broad-based, all-cause readmission measures. Instead, hospitals are being penalized for all readmissions, a majority of which may be attributable to community or patient-related factors, such as sociodemographic or housing status, among other variables.

A growing consensus on two fronts asserts that these measures, as currently structured, might not be appropriate for use in pay-for-performance programs. Measure developers, bolstered by a recent decision by the National Quality Forum to institute a trial run of risk adjusting measures for sociodemographic status, are exploring the impact of using different available variables to enhance risk adjusting their measures. Measures for readmissions are at the front of the line of these efforts. Although it is only in the beginning stages, this work could change the foundation of all quality measures used in pay-for-performance programs.

In Congress, legislation has been introduced in both the House of Representatives and the Senate aiming to refine the HRRP through additional risk adjustments. The Establishing Beneficiary Equity in the Hospital Readmission Program Act of 2015 (H.R. 1343 and S. 688), introduced by Rep. Jim Renacci (R-Ohio) and Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.), would create immediate relief for hospitals by implementing risk adjustment for dual-eligible patients and the socioeconomic status of the hospital’s patients. At the same time, when reports that are currently in progress about risk adjustment in readmission measures and the use of a 30-day window for categorizing readmissions are completed, CMS would be required to incorporate their findings into the risk adjustment in the HRRP in the future.

SHM is supporting both of these pathways toward improving risk adjustment in readmissions measures. By engaging in the measure process and advocating for the passage of legislation to refine risk adjustment, SHM has taken a stand. The goal of reducing preventable readmissions is too important to use imprecise metrics that seem to penalize the hospitals serving the nation’s neediest patients.

As hospitalists on the front line, you can join SHM in advocating for these common sense, and necessary, changes to the HRRP.

Visit SHM’s Legislative Action Center to send a message to Congress in support of the Establishing Beneficiary Equity in the Hospital Readmission Program Act of 2015.

Joshua Lapps is SHM’s government relations manager.

Nearly three-quarters of hospitals will be receiving penalties from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2016 for excess readmissions, having failed to prevent enough patients from returning to the hospital 30 days post-discharge. With so many hospitals impacted by penalties, it is understandable that the underlying methodology of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) is coming under intense scrutiny.

Research published in JAMA Internal Medicine in September hit upon many of the myriad factors—often outside of the hospital or providers’ control—that influence whether a patient is readmitted to the hospital. This information adds weight to criticism of the measures included in the HRRP and asserts the need to refine or reform the measures to better account for readmissions preventable through the interventions of the healthcare system. The behavior these measures are meant to curb, including poor quality care, inadequate access to follow-up or medications, and gaps in transitions of care, are not identifiable within broad-based, all-cause readmission measures. Instead, hospitals are being penalized for all readmissions, a majority of which may be attributable to community or patient-related factors, such as sociodemographic or housing status, among other variables.

A growing consensus on two fronts asserts that these measures, as currently structured, might not be appropriate for use in pay-for-performance programs. Measure developers, bolstered by a recent decision by the National Quality Forum to institute a trial run of risk adjusting measures for sociodemographic status, are exploring the impact of using different available variables to enhance risk adjusting their measures. Measures for readmissions are at the front of the line of these efforts. Although it is only in the beginning stages, this work could change the foundation of all quality measures used in pay-for-performance programs.

In Congress, legislation has been introduced in both the House of Representatives and the Senate aiming to refine the HRRP through additional risk adjustments. The Establishing Beneficiary Equity in the Hospital Readmission Program Act of 2015 (H.R. 1343 and S. 688), introduced by Rep. Jim Renacci (R-Ohio) and Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.), would create immediate relief for hospitals by implementing risk adjustment for dual-eligible patients and the socioeconomic status of the hospital’s patients. At the same time, when reports that are currently in progress about risk adjustment in readmission measures and the use of a 30-day window for categorizing readmissions are completed, CMS would be required to incorporate their findings into the risk adjustment in the HRRP in the future.

SHM is supporting both of these pathways toward improving risk adjustment in readmissions measures. By engaging in the measure process and advocating for the passage of legislation to refine risk adjustment, SHM has taken a stand. The goal of reducing preventable readmissions is too important to use imprecise metrics that seem to penalize the hospitals serving the nation’s neediest patients.

As hospitalists on the front line, you can join SHM in advocating for these common sense, and necessary, changes to the HRRP.

Visit SHM’s Legislative Action Center to send a message to Congress in support of the Establishing Beneficiary Equity in the Hospital Readmission Program Act of 2015.

Joshua Lapps is SHM’s government relations manager.

Nearly three-quarters of hospitals will be receiving penalties from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2016 for excess readmissions, having failed to prevent enough patients from returning to the hospital 30 days post-discharge. With so many hospitals impacted by penalties, it is understandable that the underlying methodology of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) is coming under intense scrutiny.

Research published in JAMA Internal Medicine in September hit upon many of the myriad factors—often outside of the hospital or providers’ control—that influence whether a patient is readmitted to the hospital. This information adds weight to criticism of the measures included in the HRRP and asserts the need to refine or reform the measures to better account for readmissions preventable through the interventions of the healthcare system. The behavior these measures are meant to curb, including poor quality care, inadequate access to follow-up or medications, and gaps in transitions of care, are not identifiable within broad-based, all-cause readmission measures. Instead, hospitals are being penalized for all readmissions, a majority of which may be attributable to community or patient-related factors, such as sociodemographic or housing status, among other variables.

A growing consensus on two fronts asserts that these measures, as currently structured, might not be appropriate for use in pay-for-performance programs. Measure developers, bolstered by a recent decision by the National Quality Forum to institute a trial run of risk adjusting measures for sociodemographic status, are exploring the impact of using different available variables to enhance risk adjusting their measures. Measures for readmissions are at the front of the line of these efforts. Although it is only in the beginning stages, this work could change the foundation of all quality measures used in pay-for-performance programs.

In Congress, legislation has been introduced in both the House of Representatives and the Senate aiming to refine the HRRP through additional risk adjustments. The Establishing Beneficiary Equity in the Hospital Readmission Program Act of 2015 (H.R. 1343 and S. 688), introduced by Rep. Jim Renacci (R-Ohio) and Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.), would create immediate relief for hospitals by implementing risk adjustment for dual-eligible patients and the socioeconomic status of the hospital’s patients. At the same time, when reports that are currently in progress about risk adjustment in readmission measures and the use of a 30-day window for categorizing readmissions are completed, CMS would be required to incorporate their findings into the risk adjustment in the HRRP in the future.

SHM is supporting both of these pathways toward improving risk adjustment in readmissions measures. By engaging in the measure process and advocating for the passage of legislation to refine risk adjustment, SHM has taken a stand. The goal of reducing preventable readmissions is too important to use imprecise metrics that seem to penalize the hospitals serving the nation’s neediest patients.

As hospitalists on the front line, you can join SHM in advocating for these common sense, and necessary, changes to the HRRP.

Visit SHM’s Legislative Action Center to send a message to Congress in support of the Establishing Beneficiary Equity in the Hospital Readmission Program Act of 2015.

Joshua Lapps is SHM’s government relations manager.

Case Studies in Improving Patient Care – “Missing the Beat on Patient Experience”

Presenter: Elizabeth Harry, MD

Summation: Dr. Harry structured her talk on Jonathan Sweller’s theory of Cognitive Load. Representing 3 components; Intrinsic Load (acute focused analysis and problem solving), Extrinsic load (external forces affecting our focus) and Germane Load (that which we have already learned and/or automated to minimize acute effort)

This theory applies very well to what we do as physicians. Focus on this model can make the days better for our colleges, our patients and us. It also greatly affects the patient experience. This has application both on an individual level and a system level.

Key Points:

Improve our germane load capability.

- Develop automatic behaviors regarding patient interaction that help with patient ownership and engagement.

- Develop clinical facility with standards of care, necessary studies and labs regarding the most frequent diagnosis we see

- How can we use our IT systems and daily rounding schedules to help with germane load?

Minimize our extrinsic load.

- Organized structure for communication between colleagues and staff

- Make things automatic as part of our workflow during the day

- Set up work areas and expectations that minimize interruptions

Focus effort on our intrinsic load.

- Intrinsic load is the area where we make the most difference in clinical decisions.

- Focusing on the information and wishes that are patients are conveying

- Input from different members of our teams to coordinate care

- Intrinsic load is also where we provide great value for our patient’s experience

- Is the cognitive component that provides professional satisfaction for physicians

Negative interactions, short tempers and fatigue area main symptoms of cognitive overload

“The Watchman’s Rattle” By Rebecca D. Costa was a book Dr. Harry recommended

Presenter: Elizabeth Harry, MD

Summation: Dr. Harry structured her talk on Jonathan Sweller’s theory of Cognitive Load. Representing 3 components; Intrinsic Load (acute focused analysis and problem solving), Extrinsic load (external forces affecting our focus) and Germane Load (that which we have already learned and/or automated to minimize acute effort)

This theory applies very well to what we do as physicians. Focus on this model can make the days better for our colleges, our patients and us. It also greatly affects the patient experience. This has application both on an individual level and a system level.

Key Points:

Improve our germane load capability.

- Develop automatic behaviors regarding patient interaction that help with patient ownership and engagement.

- Develop clinical facility with standards of care, necessary studies and labs regarding the most frequent diagnosis we see

- How can we use our IT systems and daily rounding schedules to help with germane load?

Minimize our extrinsic load.

- Organized structure for communication between colleagues and staff

- Make things automatic as part of our workflow during the day

- Set up work areas and expectations that minimize interruptions

Focus effort on our intrinsic load.

- Intrinsic load is the area where we make the most difference in clinical decisions.

- Focusing on the information and wishes that are patients are conveying

- Input from different members of our teams to coordinate care

- Intrinsic load is also where we provide great value for our patient’s experience

- Is the cognitive component that provides professional satisfaction for physicians

Negative interactions, short tempers and fatigue area main symptoms of cognitive overload

“The Watchman’s Rattle” By Rebecca D. Costa was a book Dr. Harry recommended

Presenter: Elizabeth Harry, MD

Summation: Dr. Harry structured her talk on Jonathan Sweller’s theory of Cognitive Load. Representing 3 components; Intrinsic Load (acute focused analysis and problem solving), Extrinsic load (external forces affecting our focus) and Germane Load (that which we have already learned and/or automated to minimize acute effort)

This theory applies very well to what we do as physicians. Focus on this model can make the days better for our colleges, our patients and us. It also greatly affects the patient experience. This has application both on an individual level and a system level.

Key Points:

Improve our germane load capability.

- Develop automatic behaviors regarding patient interaction that help with patient ownership and engagement.

- Develop clinical facility with standards of care, necessary studies and labs regarding the most frequent diagnosis we see

- How can we use our IT systems and daily rounding schedules to help with germane load?

Minimize our extrinsic load.

- Organized structure for communication between colleagues and staff

- Make things automatic as part of our workflow during the day

- Set up work areas and expectations that minimize interruptions

Focus effort on our intrinsic load.

- Intrinsic load is the area where we make the most difference in clinical decisions.

- Focusing on the information and wishes that are patients are conveying

- Input from different members of our teams to coordinate care

- Intrinsic load is also where we provide great value for our patient’s experience

- Is the cognitive component that provides professional satisfaction for physicians

Negative interactions, short tempers and fatigue area main symptoms of cognitive overload

“The Watchman’s Rattle” By Rebecca D. Costa was a book Dr. Harry recommended

Good Hospital Discharge Summaries Identified

A Yale University research team has described what constitutes a good hospital discharge, based on its analysis of 1,500 discharge summaries from patients with exacerbations of heart failure at 46 hospitals enrolled in TeleMonitoring to Improve Heart Failure Outcomes (TELE-HF), a large multicenter study of patients hospitalized with heart failure.

“We consider a good discharge to be a three-legged stool composed of timeliness, transmission to the right person, and having the right components, as defined by The Joint Commission and the Transitions of Care Consensus Conference,” says co-author Leora Horwitz, MD, MHS, director of the Center for Healthcare Innovation and Delivery Science at New York University.

“This study tells us for the first time that it is actually worth spending the time and effort to improve discharge communication, and patients do seem to benefit.”—Leora Horwitz, MD, MHS

Historically, discharge summaries were used primarily for billing, but the medical community has not made full use of them as tools for transition or considered what was really needed by the physician who will see the patient next, Dr. Horwitz says. In a previous study at Yale, as many as a third of discharge summaries were never received by a follow-up physician, and only 15% included the patient’s discharge weight—an essential detail for managing their cardiac care.

A second study using the TELE-HF data found that when the quality of the discharge summary was improved, readmissions rates were lower.

“This study tells us for the first time that it is actually worth spending the time and effort to improve discharge communication, and patients do seem to benefit,” Dr. Horwitz says.

Individual physicians should feel empowered by the result to work on system change in their hospitals, she says.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

A Yale University research team has described what constitutes a good hospital discharge, based on its analysis of 1,500 discharge summaries from patients with exacerbations of heart failure at 46 hospitals enrolled in TeleMonitoring to Improve Heart Failure Outcomes (TELE-HF), a large multicenter study of patients hospitalized with heart failure.

“We consider a good discharge to be a three-legged stool composed of timeliness, transmission to the right person, and having the right components, as defined by The Joint Commission and the Transitions of Care Consensus Conference,” says co-author Leora Horwitz, MD, MHS, director of the Center for Healthcare Innovation and Delivery Science at New York University.

“This study tells us for the first time that it is actually worth spending the time and effort to improve discharge communication, and patients do seem to benefit.”—Leora Horwitz, MD, MHS

Historically, discharge summaries were used primarily for billing, but the medical community has not made full use of them as tools for transition or considered what was really needed by the physician who will see the patient next, Dr. Horwitz says. In a previous study at Yale, as many as a third of discharge summaries were never received by a follow-up physician, and only 15% included the patient’s discharge weight—an essential detail for managing their cardiac care.

A second study using the TELE-HF data found that when the quality of the discharge summary was improved, readmissions rates were lower.

“This study tells us for the first time that it is actually worth spending the time and effort to improve discharge communication, and patients do seem to benefit,” Dr. Horwitz says.

Individual physicians should feel empowered by the result to work on system change in their hospitals, she says.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

A Yale University research team has described what constitutes a good hospital discharge, based on its analysis of 1,500 discharge summaries from patients with exacerbations of heart failure at 46 hospitals enrolled in TeleMonitoring to Improve Heart Failure Outcomes (TELE-HF), a large multicenter study of patients hospitalized with heart failure.

“We consider a good discharge to be a three-legged stool composed of timeliness, transmission to the right person, and having the right components, as defined by The Joint Commission and the Transitions of Care Consensus Conference,” says co-author Leora Horwitz, MD, MHS, director of the Center for Healthcare Innovation and Delivery Science at New York University.

“This study tells us for the first time that it is actually worth spending the time and effort to improve discharge communication, and patients do seem to benefit.”—Leora Horwitz, MD, MHS

Historically, discharge summaries were used primarily for billing, but the medical community has not made full use of them as tools for transition or considered what was really needed by the physician who will see the patient next, Dr. Horwitz says. In a previous study at Yale, as many as a third of discharge summaries were never received by a follow-up physician, and only 15% included the patient’s discharge weight—an essential detail for managing their cardiac care.

A second study using the TELE-HF data found that when the quality of the discharge summary was improved, readmissions rates were lower.

“This study tells us for the first time that it is actually worth spending the time and effort to improve discharge communication, and patients do seem to benefit,” Dr. Horwitz says.

Individual physicians should feel empowered by the result to work on system change in their hospitals, she says.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

Hospital Readmissions Rates, Medicare Penalty Analysis

A widely cited statistic in the national readmissions debate holds that one in five acute hospital discharges will lead to a readmission within 30 days.1 Associated costs are estimated at $17.5 billion, although that figure encapsulates significant variation across diagnoses, regions, and hospital models.1 Analyses by CMS and others suggest that average 30-day readmission rates have been falling, albeit slowly, to 17.8% during the fourth quarter of 2012 after averaging 19% over the previous five years, according to Congressional testimony by Medicare Director Jonathan Blum in February 2013.2

CMS calculates “excessive readmissions rates” for subsequent hospital admissions to the same or a different hospital for specific diagnoses within 30 days of discharge, risk-adjusted for planned and unrelated readmissions using methodology endorsed by the National Quality Forum. Based on the hospital’s rate of actual to expected readmissions, HRRP penalties are applied to all Medicare-based diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments to the hospital for the fiscal year in question, to a maximum of 3% of Medicare payments. The list of conditions now includes heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, acute exacerbation of COPD, other lung ailments such as chronic bronchitis, and admissions for elective total hip and total knee arthroplasty.

Aggregate average penalty in FY2015 for 2,610 hospitals paying penalties, or three-fourths of those subject to the program, will be 0.63% of total base hospital DRG reimbursement, or approximately $428 million in total readmissions penalties. Thirty-nine hospitals are paying the full 3% penalty, based on their posted readmissions between July 2010 and June 2013.3 If a hospital has fewer than 25 discharges for a given condition, then CMS does not calculate its excess readmissions penalty for that condition.

In its June 2013 report to Congress, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), which first proposed readmissions payment incentives in 2008, recommended steps to refine the computation of penalties, all with “the goal that any policy change should maintain a hospital’s incentive to reduce readmissions.”4 CMS has stated that it is continuing to revise its algorithms for excluding planned and unrelated readmissions from the penalty calculation.5

MedPAC found that the rate of “potentially preventable readmissions” (PPR) was 12.3% in 2011, according to the “3M Algorithm” developed by 3M Health Information Systems, which uses administrative data to identify hospital readmissions that may indicate problems with quality of care. The PPR logic determines whether the reason for readmission is clinically related to a prior admission and therefore potentially preventable.6

Others define preventable readmissions in terms of quality problems, medical errors through actions taken or omitted during the initial hospital stay that could lead to patient harm.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428.

- Blum J. Statement of Jonathan Blum on delivery system reform: progress report from CMS before the U.S. Senate Finance Committee. February 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/CMS%20Delivery%20System%20Reform%20Testimony%202.28.13%20(J.%20Blum).pdf. Accessed March 12, 2015.

- Rau J. Medicare Fines 2,610 Hospitals in Third Round of Readmissions Penalties. Kaiser Health News. October 2, 2014. Available at: http://kaiserhealthnews.org/news/medicare-readmissions-penalties-2015/. Accessed March 12, 2015.

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system. Chapter 4: refining the hospital readmissions reduction program. June 2013. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/reports/jun13_entirereport.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2015.

- Rodak S. CMS responds to 6 major critiques of readmissions measures. Becker’s Infection Control and Clinical Quality. August 7, 2013. Available at: http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/quality/cms-responds-to-6-major-critiques-of-readmission-measure.html. Accessed March 12 2015.

- Goldfield NI, McCullough EC, Hughes JS, et al. Identifying potentially preventable readmissions. Healthcare Financing Review. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/HealthCareFinancingReview/downloads/08Fallpg75.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2015.

A widely cited statistic in the national readmissions debate holds that one in five acute hospital discharges will lead to a readmission within 30 days.1 Associated costs are estimated at $17.5 billion, although that figure encapsulates significant variation across diagnoses, regions, and hospital models.1 Analyses by CMS and others suggest that average 30-day readmission rates have been falling, albeit slowly, to 17.8% during the fourth quarter of 2012 after averaging 19% over the previous five years, according to Congressional testimony by Medicare Director Jonathan Blum in February 2013.2

CMS calculates “excessive readmissions rates” for subsequent hospital admissions to the same or a different hospital for specific diagnoses within 30 days of discharge, risk-adjusted for planned and unrelated readmissions using methodology endorsed by the National Quality Forum. Based on the hospital’s rate of actual to expected readmissions, HRRP penalties are applied to all Medicare-based diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments to the hospital for the fiscal year in question, to a maximum of 3% of Medicare payments. The list of conditions now includes heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, acute exacerbation of COPD, other lung ailments such as chronic bronchitis, and admissions for elective total hip and total knee arthroplasty.

Aggregate average penalty in FY2015 for 2,610 hospitals paying penalties, or three-fourths of those subject to the program, will be 0.63% of total base hospital DRG reimbursement, or approximately $428 million in total readmissions penalties. Thirty-nine hospitals are paying the full 3% penalty, based on their posted readmissions between July 2010 and June 2013.3 If a hospital has fewer than 25 discharges for a given condition, then CMS does not calculate its excess readmissions penalty for that condition.

In its June 2013 report to Congress, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), which first proposed readmissions payment incentives in 2008, recommended steps to refine the computation of penalties, all with “the goal that any policy change should maintain a hospital’s incentive to reduce readmissions.”4 CMS has stated that it is continuing to revise its algorithms for excluding planned and unrelated readmissions from the penalty calculation.5

MedPAC found that the rate of “potentially preventable readmissions” (PPR) was 12.3% in 2011, according to the “3M Algorithm” developed by 3M Health Information Systems, which uses administrative data to identify hospital readmissions that may indicate problems with quality of care. The PPR logic determines whether the reason for readmission is clinically related to a prior admission and therefore potentially preventable.6

Others define preventable readmissions in terms of quality problems, medical errors through actions taken or omitted during the initial hospital stay that could lead to patient harm.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428.

- Blum J. Statement of Jonathan Blum on delivery system reform: progress report from CMS before the U.S. Senate Finance Committee. February 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/CMS%20Delivery%20System%20Reform%20Testimony%202.28.13%20(J.%20Blum).pdf. Accessed March 12, 2015.

- Rau J. Medicare Fines 2,610 Hospitals in Third Round of Readmissions Penalties. Kaiser Health News. October 2, 2014. Available at: http://kaiserhealthnews.org/news/medicare-readmissions-penalties-2015/. Accessed March 12, 2015.

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system. Chapter 4: refining the hospital readmissions reduction program. June 2013. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/reports/jun13_entirereport.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2015.

- Rodak S. CMS responds to 6 major critiques of readmissions measures. Becker’s Infection Control and Clinical Quality. August 7, 2013. Available at: http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/quality/cms-responds-to-6-major-critiques-of-readmission-measure.html. Accessed March 12 2015.

- Goldfield NI, McCullough EC, Hughes JS, et al. Identifying potentially preventable readmissions. Healthcare Financing Review. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/HealthCareFinancingReview/downloads/08Fallpg75.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2015.

A widely cited statistic in the national readmissions debate holds that one in five acute hospital discharges will lead to a readmission within 30 days.1 Associated costs are estimated at $17.5 billion, although that figure encapsulates significant variation across diagnoses, regions, and hospital models.1 Analyses by CMS and others suggest that average 30-day readmission rates have been falling, albeit slowly, to 17.8% during the fourth quarter of 2012 after averaging 19% over the previous five years, according to Congressional testimony by Medicare Director Jonathan Blum in February 2013.2

CMS calculates “excessive readmissions rates” for subsequent hospital admissions to the same or a different hospital for specific diagnoses within 30 days of discharge, risk-adjusted for planned and unrelated readmissions using methodology endorsed by the National Quality Forum. Based on the hospital’s rate of actual to expected readmissions, HRRP penalties are applied to all Medicare-based diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments to the hospital for the fiscal year in question, to a maximum of 3% of Medicare payments. The list of conditions now includes heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, acute exacerbation of COPD, other lung ailments such as chronic bronchitis, and admissions for elective total hip and total knee arthroplasty.

Aggregate average penalty in FY2015 for 2,610 hospitals paying penalties, or three-fourths of those subject to the program, will be 0.63% of total base hospital DRG reimbursement, or approximately $428 million in total readmissions penalties. Thirty-nine hospitals are paying the full 3% penalty, based on their posted readmissions between July 2010 and June 2013.3 If a hospital has fewer than 25 discharges for a given condition, then CMS does not calculate its excess readmissions penalty for that condition.

In its June 2013 report to Congress, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), which first proposed readmissions payment incentives in 2008, recommended steps to refine the computation of penalties, all with “the goal that any policy change should maintain a hospital’s incentive to reduce readmissions.”4 CMS has stated that it is continuing to revise its algorithms for excluding planned and unrelated readmissions from the penalty calculation.5

MedPAC found that the rate of “potentially preventable readmissions” (PPR) was 12.3% in 2011, according to the “3M Algorithm” developed by 3M Health Information Systems, which uses administrative data to identify hospital readmissions that may indicate problems with quality of care. The PPR logic determines whether the reason for readmission is clinically related to a prior admission and therefore potentially preventable.6

Others define preventable readmissions in terms of quality problems, medical errors through actions taken or omitted during the initial hospital stay that could lead to patient harm.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428.

- Blum J. Statement of Jonathan Blum on delivery system reform: progress report from CMS before the U.S. Senate Finance Committee. February 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/CMS%20Delivery%20System%20Reform%20Testimony%202.28.13%20(J.%20Blum).pdf. Accessed March 12, 2015.

- Rau J. Medicare Fines 2,610 Hospitals in Third Round of Readmissions Penalties. Kaiser Health News. October 2, 2014. Available at: http://kaiserhealthnews.org/news/medicare-readmissions-penalties-2015/. Accessed March 12, 2015.

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system. Chapter 4: refining the hospital readmissions reduction program. June 2013. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/reports/jun13_entirereport.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2015.

- Rodak S. CMS responds to 6 major critiques of readmissions measures. Becker’s Infection Control and Clinical Quality. August 7, 2013. Available at: http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/quality/cms-responds-to-6-major-critiques-of-readmission-measure.html. Accessed March 12 2015.

- Goldfield NI, McCullough EC, Hughes JS, et al. Identifying potentially preventable readmissions. Healthcare Financing Review. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/HealthCareFinancingReview/downloads/08Fallpg75.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2015.

Primary-Care Physicians Weigh in on Quality of Care Transitions

A new study on transitions of care gives hospitalists a view from the other side.

Published recently online in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the authors surveyed 22 primary-care physician leaders in California-based post-discharge clinics and asked them about ways to improve care transitions.

Physicians' responses focused on several areas that need work, most notably aligned financial incentives, regulations to standardize interoperability among electronic health records (EHR) and data sharing, and more opportunities for professional networking, the authors note.

Although the qualitative study takes a broad view of the healthcare system, its lead author says hospitalists should view "systems change" as a long-term goal achievable via incremental improvements that can start now.

"National policy change is needed to move the needle for the whole health system," says hospitalist Oanh Kieu Nguyen, MD, MAS, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. "But locally, you can innovate within these domains and start to make changes to improve practice settings more immediately. National policy to align financial incentives and improve EHR interoperability will be key to helping local changes take hold and spread across systems. Otherwise, there will continue to be a lot of variability and fragmentation around care transitions on a national level."

Dr. Nguyen, who has practiced as both a hospitalist and PCP, says that because policies and studies on post-discharge care transitions primarily have focused on the hospital perspective, it is important to gain an understanding of the primary-care point of view.

"As a hospitalist, it's really easy to get caught up in just wanting to get patients teed up and sent home. Once they're out, we think they're no longer really our problem," Dr. Nguyen adds. "It's easy to forget that primary care is an important part of the other side of the equation. The way our healthcare system is designed doesn't really give physicians an incentive to look at the whole picture of a patient across all the environments they're in."

Many hospitalists are sharing their challenges and successes in care transitions through HMX. Join the conversation now.

Visit our website for more information on transitions of care.

A new study on transitions of care gives hospitalists a view from the other side.

Published recently online in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the authors surveyed 22 primary-care physician leaders in California-based post-discharge clinics and asked them about ways to improve care transitions.

Physicians' responses focused on several areas that need work, most notably aligned financial incentives, regulations to standardize interoperability among electronic health records (EHR) and data sharing, and more opportunities for professional networking, the authors note.

Although the qualitative study takes a broad view of the healthcare system, its lead author says hospitalists should view "systems change" as a long-term goal achievable via incremental improvements that can start now.

"National policy change is needed to move the needle for the whole health system," says hospitalist Oanh Kieu Nguyen, MD, MAS, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. "But locally, you can innovate within these domains and start to make changes to improve practice settings more immediately. National policy to align financial incentives and improve EHR interoperability will be key to helping local changes take hold and spread across systems. Otherwise, there will continue to be a lot of variability and fragmentation around care transitions on a national level."

Dr. Nguyen, who has practiced as both a hospitalist and PCP, says that because policies and studies on post-discharge care transitions primarily have focused on the hospital perspective, it is important to gain an understanding of the primary-care point of view.

"As a hospitalist, it's really easy to get caught up in just wanting to get patients teed up and sent home. Once they're out, we think they're no longer really our problem," Dr. Nguyen adds. "It's easy to forget that primary care is an important part of the other side of the equation. The way our healthcare system is designed doesn't really give physicians an incentive to look at the whole picture of a patient across all the environments they're in."

Many hospitalists are sharing their challenges and successes in care transitions through HMX. Join the conversation now.

Visit our website for more information on transitions of care.

A new study on transitions of care gives hospitalists a view from the other side.

Published recently online in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the authors surveyed 22 primary-care physician leaders in California-based post-discharge clinics and asked them about ways to improve care transitions.

Physicians' responses focused on several areas that need work, most notably aligned financial incentives, regulations to standardize interoperability among electronic health records (EHR) and data sharing, and more opportunities for professional networking, the authors note.

Although the qualitative study takes a broad view of the healthcare system, its lead author says hospitalists should view "systems change" as a long-term goal achievable via incremental improvements that can start now.

"National policy change is needed to move the needle for the whole health system," says hospitalist Oanh Kieu Nguyen, MD, MAS, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. "But locally, you can innovate within these domains and start to make changes to improve practice settings more immediately. National policy to align financial incentives and improve EHR interoperability will be key to helping local changes take hold and spread across systems. Otherwise, there will continue to be a lot of variability and fragmentation around care transitions on a national level."

Dr. Nguyen, who has practiced as both a hospitalist and PCP, says that because policies and studies on post-discharge care transitions primarily have focused on the hospital perspective, it is important to gain an understanding of the primary-care point of view.

"As a hospitalist, it's really easy to get caught up in just wanting to get patients teed up and sent home. Once they're out, we think they're no longer really our problem," Dr. Nguyen adds. "It's easy to forget that primary care is an important part of the other side of the equation. The way our healthcare system is designed doesn't really give physicians an incentive to look at the whole picture of a patient across all the environments they're in."

Many hospitalists are sharing their challenges and successes in care transitions through HMX. Join the conversation now.

Visit our website for more information on transitions of care.

Homecare Will Help You Achieve the Triple Aim

Where there is variation, there is room for improvement. The Institute of Medicine’s report on geographic variation in Medicare spending concluded that the largest contributor to overall spending variation is spending for post-acute care services.1 Furthermore, we know that a significant amount of overall spending is devoted to post-acute care. For example, for patients hospitalized with a flare-up of a chronic condition like COPD or heart failure, Medicare spends nearly as much on post-acute care and readmissions in the first 30 days after discharge as it does on the initial admission.1

What does this mean for hospitalists?

Numerous research articles and quality improvement projects have focused on what makes a good hospital discharge or hand off to the ‘next provider of care’; however, hospitalists are increasingly participating in value-based payment programs like accountable care organizations (ACOs), risk contracts, and bundled payments. This means they must begin to pay attention to the cost side of the value equation (quality divided by cost) as it relates to hospital discharge.

A day of home care represents a more cost-effective alternative than a day of care in a skilled nursing facility (SNF). Hospitalists who can identify those patients who are appropriate to send home with home health services—and who otherwise would have gone to a SNF—will serve the dual goals of improving patient experience and decreasing costs.

Hospitalists will need to develop a decision-making process that determines the appropriate level of care for the patient after discharge. The decision-making process should address questions like:

- What skilled services lead a patient to go to a SNF instead of home with home health?

- Which patients go to a SNF instead of home simply because they don’t have family or a caregiver to help them with activities of daily living?

- Are there services requiring a nurse or a therapist that can’t be delivered in the home?

Hospitalists also will need to develop a more intimate understanding of the following levels of care:

- Skilled nursing includes management of a nursing care plan, assessment of a patient’s changing condition, and services like wound care, infusion therapy, and management of medications, feeding or drainage tubes, and pain.

- Skilled rehabilitation refers to the array of services provided by physical, occupational, speech, and respiratory therapists.

- Custodial care, usually supplied by a home health aid or family member, includes help with activities of daily living (feeding, dressing, bathing, grooming, personal hygiene, and toileting).

It should be noted that most skilled nursing or therapy services can be delivered in the home setting if the patient’s custodial care needs are met—a big ‘if’ in some cases. Some patients go to a SNF because they require three or more skilled nursing or therapy services, and it is therefore impractical for them to go home.

Here are my suggestions to hospitalists seeking to reengineer the discharge process with the goals of “right-sizing” the number of patients who go to SNFs and optimizing the utilization of home healthcare services:

- Become familiar with the range of post-acute care providers and care coordination services in your community.

- Refer any patient who wishes to go home, either directly or after a SNF stay, for a home care evaluation. Home care agencies are experts in determining if and how patients can return home.

- If a need for help with activities of daily living is the major barrier to having a patient discharged to home, create a system in which case management develops a custodial care plan with the patient and caregivers during the inpatient stay. Currently, this step is delayed until well into the SNF stay and may prolong that stay. Such a plan includes a financial analysis, screening for Medicaid eligibility, and evaluating whether a family member can assume some or all of the custodial care needs.

- If a patient is being discharged to a SNF, review the list of needed services leading to the SNF transfer. Ask the case manager if these services can be provided in the home. If not, then why?

- Bed capacity permitting, consider keeping patients who are functionally improving in the hospital an extra day so they can be discharged directly home instead of to a SNF.2

In his seminal work, The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton Christensen describes “disruptive innovation” as that which gives rise to products or services that are cheaper, simpler, and more convenient to use. Even though home care has been around for a while, there is a sizeable group of patients, especially in geographic areas of high SNF spending, who might be better served in the home environment. As we create better systems under value-based payment, we should see an increase in the use of home healthcare as a disruptive innovation when applied to appropriate patients transitioning out of the hospital or a SNF.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

References

Where there is variation, there is room for improvement. The Institute of Medicine’s report on geographic variation in Medicare spending concluded that the largest contributor to overall spending variation is spending for post-acute care services.1 Furthermore, we know that a significant amount of overall spending is devoted to post-acute care. For example, for patients hospitalized with a flare-up of a chronic condition like COPD or heart failure, Medicare spends nearly as much on post-acute care and readmissions in the first 30 days after discharge as it does on the initial admission.1

What does this mean for hospitalists?

Numerous research articles and quality improvement projects have focused on what makes a good hospital discharge or hand off to the ‘next provider of care’; however, hospitalists are increasingly participating in value-based payment programs like accountable care organizations (ACOs), risk contracts, and bundled payments. This means they must begin to pay attention to the cost side of the value equation (quality divided by cost) as it relates to hospital discharge.

A day of home care represents a more cost-effective alternative than a day of care in a skilled nursing facility (SNF). Hospitalists who can identify those patients who are appropriate to send home with home health services—and who otherwise would have gone to a SNF—will serve the dual goals of improving patient experience and decreasing costs.

Hospitalists will need to develop a decision-making process that determines the appropriate level of care for the patient after discharge. The decision-making process should address questions like:

- What skilled services lead a patient to go to a SNF instead of home with home health?

- Which patients go to a SNF instead of home simply because they don’t have family or a caregiver to help them with activities of daily living?

- Are there services requiring a nurse or a therapist that can’t be delivered in the home?

Hospitalists also will need to develop a more intimate understanding of the following levels of care:

- Skilled nursing includes management of a nursing care plan, assessment of a patient’s changing condition, and services like wound care, infusion therapy, and management of medications, feeding or drainage tubes, and pain.

- Skilled rehabilitation refers to the array of services provided by physical, occupational, speech, and respiratory therapists.

- Custodial care, usually supplied by a home health aid or family member, includes help with activities of daily living (feeding, dressing, bathing, grooming, personal hygiene, and toileting).

It should be noted that most skilled nursing or therapy services can be delivered in the home setting if the patient’s custodial care needs are met—a big ‘if’ in some cases. Some patients go to a SNF because they require three or more skilled nursing or therapy services, and it is therefore impractical for them to go home.

Here are my suggestions to hospitalists seeking to reengineer the discharge process with the goals of “right-sizing” the number of patients who go to SNFs and optimizing the utilization of home healthcare services:

- Become familiar with the range of post-acute care providers and care coordination services in your community.

- Refer any patient who wishes to go home, either directly or after a SNF stay, for a home care evaluation. Home care agencies are experts in determining if and how patients can return home.

- If a need for help with activities of daily living is the major barrier to having a patient discharged to home, create a system in which case management develops a custodial care plan with the patient and caregivers during the inpatient stay. Currently, this step is delayed until well into the SNF stay and may prolong that stay. Such a plan includes a financial analysis, screening for Medicaid eligibility, and evaluating whether a family member can assume some or all of the custodial care needs.

- If a patient is being discharged to a SNF, review the list of needed services leading to the SNF transfer. Ask the case manager if these services can be provided in the home. If not, then why?

- Bed capacity permitting, consider keeping patients who are functionally improving in the hospital an extra day so they can be discharged directly home instead of to a SNF.2