User login

Pallor and weight loss

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory condition that characteristically involves the large bowel. Disease activity usually follows a pattern of periods of active inflammation alternating with periods of remission. Approximately 15% of patients experience an aggressive course of ulcerative colitis. Acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC) is a life-threatening medical emergency, which may require hospitalization for prompt medical treatment and colectomy if medical treatment fails. Predictors of an aggressive disease course and colectomy include young age at the time of diagnosis, extensive disease, severe endoscopic disease activity, presence of extraintestinal manifestations, elevated inflammatory markers, and early need for corticosteroids.

The diagnosis of ASUC is based on the Mayo Clinic Score and the Truelove and Witts criteria which consists of the presence of six or more bloody stools per day and at least one of these signs of systemic toxicity:

• Pulse rate > 90 beats/min

• Temperature > 100.04 °F

• Hemoglobin < 10.5 g/dL

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) > 30 mm/h

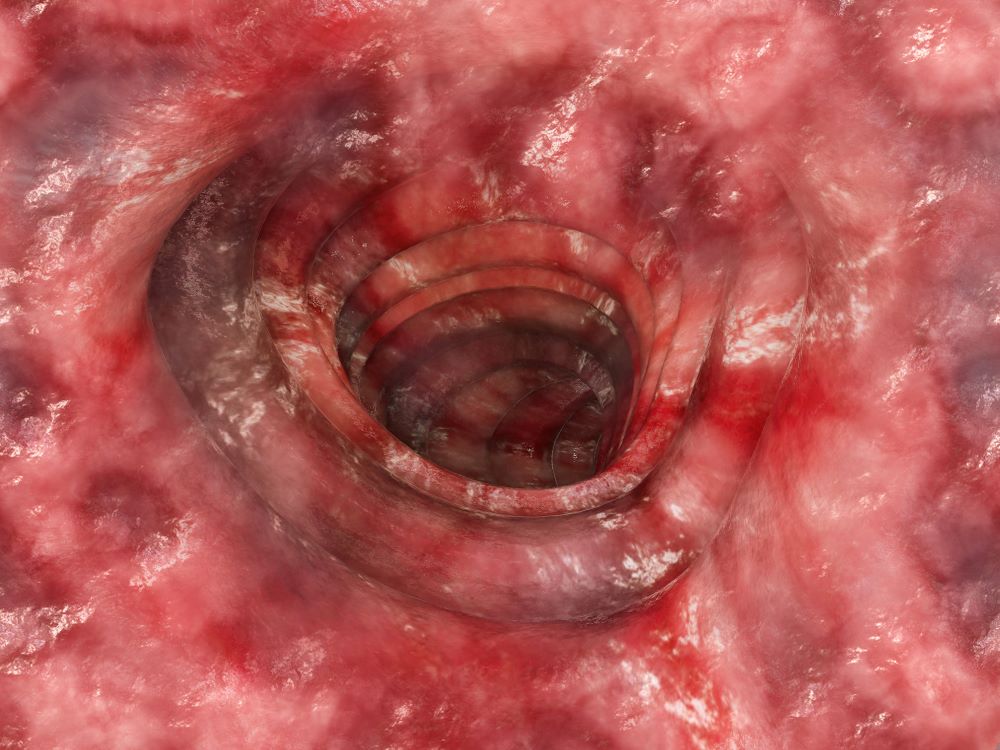

Further evaluation in patients with suspected ASUC aims to exclude alternative diagnoses and to determine the severity and extent of disease. Abdominal radiographs are obtained to rule out colonic dilatation and to evaluate for the possibility of microperforations. Stool studies should be obtained to evaluate for infections such as C difficile. To assess for the severity of mucosal disease a limited lower endoscopy is usually performed in hospitalized patients with ASUC. In addition, it allows for the opportunity to perform a biopsy to rule out cytomegalovirus as the cause of the disease flare. However, a colonoscopy should be avoided in these patients because of the increased risk for colonic dilation and perforation; a carefully performed flexible sigmoidoscopy with minimal insufflation by an experienced operator is sufficient for most patients. Endoscopic features of ASUC include erythema, absent vascular pattern, friability, erosions, and ulcerations.

The mainstay of management of hospitalized individuals with ASUC is intravenous corticosteroids. However, up to one third of patients may not show improvement in clinical or biochemical markers after treatment with steroids. In hospitalized patients with ASUC refractory to 3 to 5 days of intravenous corticosteroids infliximab or cyclosporin are suggested. Colectomy is a treatment option for patients unresponsive to medical therapy or for patients who develop life-threatening complications (colonic perforation, toxic megacolon, etc.)

Leyla Ghazi, MD, Physician, Dartmouth Health, GI Associates, Concord, New Hampshire.

Leyla Ghazi, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory condition that characteristically involves the large bowel. Disease activity usually follows a pattern of periods of active inflammation alternating with periods of remission. Approximately 15% of patients experience an aggressive course of ulcerative colitis. Acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC) is a life-threatening medical emergency, which may require hospitalization for prompt medical treatment and colectomy if medical treatment fails. Predictors of an aggressive disease course and colectomy include young age at the time of diagnosis, extensive disease, severe endoscopic disease activity, presence of extraintestinal manifestations, elevated inflammatory markers, and early need for corticosteroids.

The diagnosis of ASUC is based on the Mayo Clinic Score and the Truelove and Witts criteria which consists of the presence of six or more bloody stools per day and at least one of these signs of systemic toxicity:

• Pulse rate > 90 beats/min

• Temperature > 100.04 °F

• Hemoglobin < 10.5 g/dL

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) > 30 mm/h

Further evaluation in patients with suspected ASUC aims to exclude alternative diagnoses and to determine the severity and extent of disease. Abdominal radiographs are obtained to rule out colonic dilatation and to evaluate for the possibility of microperforations. Stool studies should be obtained to evaluate for infections such as C difficile. To assess for the severity of mucosal disease a limited lower endoscopy is usually performed in hospitalized patients with ASUC. In addition, it allows for the opportunity to perform a biopsy to rule out cytomegalovirus as the cause of the disease flare. However, a colonoscopy should be avoided in these patients because of the increased risk for colonic dilation and perforation; a carefully performed flexible sigmoidoscopy with minimal insufflation by an experienced operator is sufficient for most patients. Endoscopic features of ASUC include erythema, absent vascular pattern, friability, erosions, and ulcerations.

The mainstay of management of hospitalized individuals with ASUC is intravenous corticosteroids. However, up to one third of patients may not show improvement in clinical or biochemical markers after treatment with steroids. In hospitalized patients with ASUC refractory to 3 to 5 days of intravenous corticosteroids infliximab or cyclosporin are suggested. Colectomy is a treatment option for patients unresponsive to medical therapy or for patients who develop life-threatening complications (colonic perforation, toxic megacolon, etc.)

Leyla Ghazi, MD, Physician, Dartmouth Health, GI Associates, Concord, New Hampshire.

Leyla Ghazi, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory condition that characteristically involves the large bowel. Disease activity usually follows a pattern of periods of active inflammation alternating with periods of remission. Approximately 15% of patients experience an aggressive course of ulcerative colitis. Acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC) is a life-threatening medical emergency, which may require hospitalization for prompt medical treatment and colectomy if medical treatment fails. Predictors of an aggressive disease course and colectomy include young age at the time of diagnosis, extensive disease, severe endoscopic disease activity, presence of extraintestinal manifestations, elevated inflammatory markers, and early need for corticosteroids.

The diagnosis of ASUC is based on the Mayo Clinic Score and the Truelove and Witts criteria which consists of the presence of six or more bloody stools per day and at least one of these signs of systemic toxicity:

• Pulse rate > 90 beats/min

• Temperature > 100.04 °F

• Hemoglobin < 10.5 g/dL

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) > 30 mm/h

Further evaluation in patients with suspected ASUC aims to exclude alternative diagnoses and to determine the severity and extent of disease. Abdominal radiographs are obtained to rule out colonic dilatation and to evaluate for the possibility of microperforations. Stool studies should be obtained to evaluate for infections such as C difficile. To assess for the severity of mucosal disease a limited lower endoscopy is usually performed in hospitalized patients with ASUC. In addition, it allows for the opportunity to perform a biopsy to rule out cytomegalovirus as the cause of the disease flare. However, a colonoscopy should be avoided in these patients because of the increased risk for colonic dilation and perforation; a carefully performed flexible sigmoidoscopy with minimal insufflation by an experienced operator is sufficient for most patients. Endoscopic features of ASUC include erythema, absent vascular pattern, friability, erosions, and ulcerations.

The mainstay of management of hospitalized individuals with ASUC is intravenous corticosteroids. However, up to one third of patients may not show improvement in clinical or biochemical markers after treatment with steroids. In hospitalized patients with ASUC refractory to 3 to 5 days of intravenous corticosteroids infliximab or cyclosporin are suggested. Colectomy is a treatment option for patients unresponsive to medical therapy or for patients who develop life-threatening complications (colonic perforation, toxic megacolon, etc.)

Leyla Ghazi, MD, Physician, Dartmouth Health, GI Associates, Concord, New Hampshire.

Leyla Ghazi, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 36-year-old man presents reporting bouts of bloody diarrhea up to 10 times per day for the past 6 weeks. The diarrhea is associated with asymmetric polyarthralgia in the elbows and knees; a skin rash on the lower extremities; fatigue, weakness, and pallor; and a 12-lb weight loss. One month before, the patient had a colonoscopy that revealed left-sided ulcerative colitis (UC); results were confirmed with biopsy and the patient was started on mesalamine and prednisone.

Vital signs at the time of presentation include blood pressure 90/58, heart rate 112 beats/min, respiratory rate 21 breaths/min, and body temperature 101.9 °F. Examination shows generalized pallor with pale conjunctiva and dry mucosa. No heart murmurs are heard on auscultation. Palpation of the abdomen reveals no palpable masses or organomegaly. Mild pain is present on palpation of the left lower quadrant but without signs of peritoneal irritation. Bowel sounds are present. The lower extremities display erythematous nodular lesions and no edema. Peripheral pulses are present. Laboratory results showed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 60 mm, C-reactive protein of 20.2 mg/L, and hemoglobin of 9.8 g/dL. Abdominal radiographs were within normal limits. Stool cultures are pending. Flexible sigmoidoscopy was performed shortly after admission and showed the results above. Biopsies were taken to rule out infection.

Severe abdominal pain and vomiting

On the basis of the patient’s family history, personal history, and presentation, the likely diagnosis is Crohn disease. Although the disease may be diagnosed at any age, onset shows a bimodal distribution, with the first, more predominant wave occurring in adolescence and early adulthood. Peak global onset is between the ages of 15 and 30. Compared with adult-onset disease, pediatric Crohn disease is associated with a more serious disease course. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing this autoimmune disease than any other ethnic group.

Colonoscopy is the first-line approach for diagnosing and monitoring inflammatory bowel disease. Typical findings in patients with Crohn disease include histologic changes, such as focal crypt irregularity, transmural lymphoid aggregates, fissures and fistulas, and perianal disorders. In the differential diagnosis, ulcerative colitis (UC) must be carefully ruled out. UC involves only the large bowel, rarely causes fistulas, and is frequently seen with bleeding. Crohn disease is characteristically noncontiguous, with linear ulcerations of a cobblestone appearance. In addition, noncaseating granulomas are specific for Crohn disease. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low, as seen in the present case. During workup, fecal calprotectin can help differentiate inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome.

The patient in this case may be a candidate for 5-aminosalicylic acid, together with a nutritional plan, used in mild or moderate cases of pediatric Crohn disease. Clinical improvement plus a decrease of fecal calprotectin would be an indication of positive treatment response. Being newly diagnosed, if the patient does not achieve remission after the induction period, he may be at risk for a more complicated disease course. Treatment for Crohn disease in the pediatric setting, as in the adult setting, should be implemented through a step-up approach. Other treatment options for pediatric disease include antibiotics; immunomodulators; and, in moderate-to severe cases, corticosteroids and biologics.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient’s family history, personal history, and presentation, the likely diagnosis is Crohn disease. Although the disease may be diagnosed at any age, onset shows a bimodal distribution, with the first, more predominant wave occurring in adolescence and early adulthood. Peak global onset is between the ages of 15 and 30. Compared with adult-onset disease, pediatric Crohn disease is associated with a more serious disease course. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing this autoimmune disease than any other ethnic group.

Colonoscopy is the first-line approach for diagnosing and monitoring inflammatory bowel disease. Typical findings in patients with Crohn disease include histologic changes, such as focal crypt irregularity, transmural lymphoid aggregates, fissures and fistulas, and perianal disorders. In the differential diagnosis, ulcerative colitis (UC) must be carefully ruled out. UC involves only the large bowel, rarely causes fistulas, and is frequently seen with bleeding. Crohn disease is characteristically noncontiguous, with linear ulcerations of a cobblestone appearance. In addition, noncaseating granulomas are specific for Crohn disease. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low, as seen in the present case. During workup, fecal calprotectin can help differentiate inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome.

The patient in this case may be a candidate for 5-aminosalicylic acid, together with a nutritional plan, used in mild or moderate cases of pediatric Crohn disease. Clinical improvement plus a decrease of fecal calprotectin would be an indication of positive treatment response. Being newly diagnosed, if the patient does not achieve remission after the induction period, he may be at risk for a more complicated disease course. Treatment for Crohn disease in the pediatric setting, as in the adult setting, should be implemented through a step-up approach. Other treatment options for pediatric disease include antibiotics; immunomodulators; and, in moderate-to severe cases, corticosteroids and biologics.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient’s family history, personal history, and presentation, the likely diagnosis is Crohn disease. Although the disease may be diagnosed at any age, onset shows a bimodal distribution, with the first, more predominant wave occurring in adolescence and early adulthood. Peak global onset is between the ages of 15 and 30. Compared with adult-onset disease, pediatric Crohn disease is associated with a more serious disease course. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing this autoimmune disease than any other ethnic group.

Colonoscopy is the first-line approach for diagnosing and monitoring inflammatory bowel disease. Typical findings in patients with Crohn disease include histologic changes, such as focal crypt irregularity, transmural lymphoid aggregates, fissures and fistulas, and perianal disorders. In the differential diagnosis, ulcerative colitis (UC) must be carefully ruled out. UC involves only the large bowel, rarely causes fistulas, and is frequently seen with bleeding. Crohn disease is characteristically noncontiguous, with linear ulcerations of a cobblestone appearance. In addition, noncaseating granulomas are specific for Crohn disease. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low, as seen in the present case. During workup, fecal calprotectin can help differentiate inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome.

The patient in this case may be a candidate for 5-aminosalicylic acid, together with a nutritional plan, used in mild or moderate cases of pediatric Crohn disease. Clinical improvement plus a decrease of fecal calprotectin would be an indication of positive treatment response. Being newly diagnosed, if the patient does not achieve remission after the induction period, he may be at risk for a more complicated disease course. Treatment for Crohn disease in the pediatric setting, as in the adult setting, should be implemented through a step-up approach. Other treatment options for pediatric disease include antibiotics; immunomodulators; and, in moderate-to severe cases, corticosteroids and biologics.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 12-year-old boy presents to an urgent care center with severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. His height is 5 ft 3 in and weight is 99 lb (BMI 18.7). The patient has a history of chronic diarrhea and reports intermittent abdominal pain that began about 6 months ago. During this time, he has lost about 12 lb, as many foods exacerbate his symptoms, though his mother notes that even plain foods can bother his stomach. Further questioning reveals that his father has moderate Crohn disease (age of onset, 29 years), his sister has celiac disease, and the patient is of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. His body temperature is 100.2 °F. Vitamin B12, serum iron, total iron binding capacity, calcium, and magnesium are low. Stool cultures are negative. Ileocolonoscopy shows small aphthous erosions in the large intestine and in the terminal ileum.

Crohn Disease Medication Overview

Ulcerative Colitis Medications

Lower abdominal pain and dehydration

The diagnosis in this patient is ulcerative colitis (UC) on the basis of physical examination, laboratory values, and endoscopy. However, this patient has the most extensive form, pancolitis, which means that inflammation and damage extend the entire length of the colon.

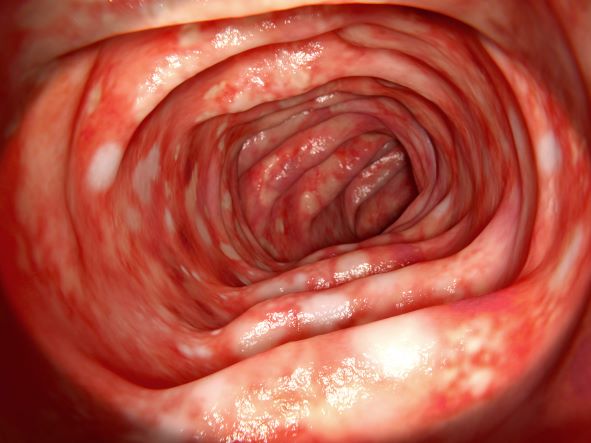

The diagnosis of UC is best made with endoscopy and mucosal biopsy for histopathology. Characteristic findings are abnormal erythematous mucosa, with or without ulceration, extending from the rectum to a part or all of the colon and uniform inflammation, without intervening areas of normal mucosa (skip lesions tend to characterize Crohn disease). Contact bleeding may also be observed, with mucus identified in the lumen of the bowel.

The bowel wall is thin or of normal thickness, but edema, accumulation of fat, and hypertrophy of the muscle layer may give it the appearance of a thickened bowel wall. The disease is largely confined to the mucosa and, to a lesser extent, the submucosa.

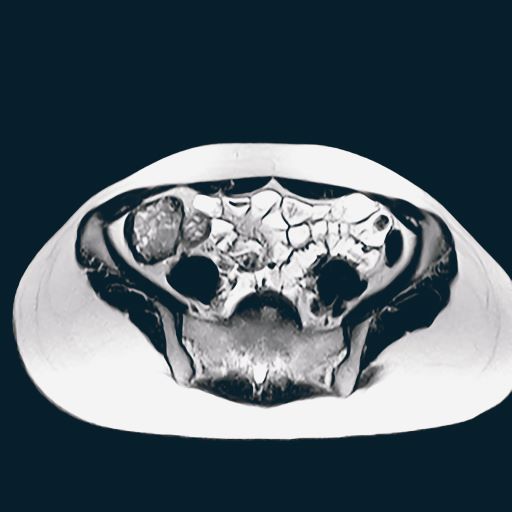

Laboratory studies are helpful to exclude other diagnoses and assess the patient's nutritional status, and serologic markers aid in the differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Radiographic imaging has an important role in differentiation of UC from Crohn disease. Fistulas or the presence of small bowel disease are seen only in Crohn disease.

According the American Gastroenterological Association, drug classes for the long-term management of moderate to severe UC include tumor necrosis factor–alpha antagonists, anti-integrin agent (vedolizumab), Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib), interleukin 12/23 antagonist (ustekinumab), and immunomodulators (thiopurines, methotrexate). Most drugs that are initiated for the induction of remission are continued as maintenance therapy if they are effective. This is not the case, however, if corticosteroids or cyclosporine are necessary to induce remission.

This patient's pancolitis presentation is also acute and severe, defined as more than 6 bloody bowel movements per day plus one of the following: fever > 100.4 °F, hemoglobin level < 10.5 g/dL, heart rate > 90 beats/min, erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 30 mm/h, or C-reactive protein level > 30 mg/dL). This requires hospitalization and treatment with intravenous corticosteroids (hydrocortisone 400 mg/d or methylprednisolone 60 mg/d). Considered a medical emergency, the situation requires prompt recognition and multidisciplinary management. In patients who fail therapy with 3-5 days of intravenous corticosteroids, medical rescue therapy is indicated with either infliximab or cyclosporine. If all measures fail, the patient may need emergency surgery.

Hospitalized patients with acute severe UC have short-term colectomy rates of 25%-30%.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The diagnosis in this patient is ulcerative colitis (UC) on the basis of physical examination, laboratory values, and endoscopy. However, this patient has the most extensive form, pancolitis, which means that inflammation and damage extend the entire length of the colon.

The diagnosis of UC is best made with endoscopy and mucosal biopsy for histopathology. Characteristic findings are abnormal erythematous mucosa, with or without ulceration, extending from the rectum to a part or all of the colon and uniform inflammation, without intervening areas of normal mucosa (skip lesions tend to characterize Crohn disease). Contact bleeding may also be observed, with mucus identified in the lumen of the bowel.

The bowel wall is thin or of normal thickness, but edema, accumulation of fat, and hypertrophy of the muscle layer may give it the appearance of a thickened bowel wall. The disease is largely confined to the mucosa and, to a lesser extent, the submucosa.

Laboratory studies are helpful to exclude other diagnoses and assess the patient's nutritional status, and serologic markers aid in the differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Radiographic imaging has an important role in differentiation of UC from Crohn disease. Fistulas or the presence of small bowel disease are seen only in Crohn disease.

According the American Gastroenterological Association, drug classes for the long-term management of moderate to severe UC include tumor necrosis factor–alpha antagonists, anti-integrin agent (vedolizumab), Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib), interleukin 12/23 antagonist (ustekinumab), and immunomodulators (thiopurines, methotrexate). Most drugs that are initiated for the induction of remission are continued as maintenance therapy if they are effective. This is not the case, however, if corticosteroids or cyclosporine are necessary to induce remission.

This patient's pancolitis presentation is also acute and severe, defined as more than 6 bloody bowel movements per day plus one of the following: fever > 100.4 °F, hemoglobin level < 10.5 g/dL, heart rate > 90 beats/min, erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 30 mm/h, or C-reactive protein level > 30 mg/dL). This requires hospitalization and treatment with intravenous corticosteroids (hydrocortisone 400 mg/d or methylprednisolone 60 mg/d). Considered a medical emergency, the situation requires prompt recognition and multidisciplinary management. In patients who fail therapy with 3-5 days of intravenous corticosteroids, medical rescue therapy is indicated with either infliximab or cyclosporine. If all measures fail, the patient may need emergency surgery.

Hospitalized patients with acute severe UC have short-term colectomy rates of 25%-30%.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The diagnosis in this patient is ulcerative colitis (UC) on the basis of physical examination, laboratory values, and endoscopy. However, this patient has the most extensive form, pancolitis, which means that inflammation and damage extend the entire length of the colon.

The diagnosis of UC is best made with endoscopy and mucosal biopsy for histopathology. Characteristic findings are abnormal erythematous mucosa, with or without ulceration, extending from the rectum to a part or all of the colon and uniform inflammation, without intervening areas of normal mucosa (skip lesions tend to characterize Crohn disease). Contact bleeding may also be observed, with mucus identified in the lumen of the bowel.

The bowel wall is thin or of normal thickness, but edema, accumulation of fat, and hypertrophy of the muscle layer may give it the appearance of a thickened bowel wall. The disease is largely confined to the mucosa and, to a lesser extent, the submucosa.

Laboratory studies are helpful to exclude other diagnoses and assess the patient's nutritional status, and serologic markers aid in the differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Radiographic imaging has an important role in differentiation of UC from Crohn disease. Fistulas or the presence of small bowel disease are seen only in Crohn disease.

According the American Gastroenterological Association, drug classes for the long-term management of moderate to severe UC include tumor necrosis factor–alpha antagonists, anti-integrin agent (vedolizumab), Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib), interleukin 12/23 antagonist (ustekinumab), and immunomodulators (thiopurines, methotrexate). Most drugs that are initiated for the induction of remission are continued as maintenance therapy if they are effective. This is not the case, however, if corticosteroids or cyclosporine are necessary to induce remission.

This patient's pancolitis presentation is also acute and severe, defined as more than 6 bloody bowel movements per day plus one of the following: fever > 100.4 °F, hemoglobin level < 10.5 g/dL, heart rate > 90 beats/min, erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 30 mm/h, or C-reactive protein level > 30 mg/dL). This requires hospitalization and treatment with intravenous corticosteroids (hydrocortisone 400 mg/d or methylprednisolone 60 mg/d). Considered a medical emergency, the situation requires prompt recognition and multidisciplinary management. In patients who fail therapy with 3-5 days of intravenous corticosteroids, medical rescue therapy is indicated with either infliximab or cyclosporine. If all measures fail, the patient may need emergency surgery.

Hospitalized patients with acute severe UC have short-term colectomy rates of 25%-30%.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 76-year-old man presents with complaints of severe lower abdominal pain and dehydration. He reports bloody diarrhea of 2 weeks' duration and an unintentional 12-lb weight loss. Dietary alterations and loperamide have not helped. He has a fever of 102.1 °F. Medications include naproxen 440 mg/d for osteoarthritis, losartan 50 mg/d and amlodipine 5 mg/d for hypertension, and simvastatin 20 mg/d for dyslipidemia.

Physical examination reveals tenderness, particularly at the left lower quadrant of the abdomen, without rebound tenderness or guarding. Bowel sounds are active. He has a purulent rectal discharge. Stool cultures for the pathogens are negative. He has hypoalbuminemia (2.5 g/dL). He is positive for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen test is negative. C-reactive protein is 32 mg/dL.

The patient is admitted to the hospital and receives intravenous fluids. Colonoscopy reveals inflammation and visible ulcers in the mucosa throughout the entire length of the colon.

Diarrhea and weight loss

On the basis of the patient's presentation and history, this is probably a case of Crohn disease. Considering that the age of onset of Crohn disease has a bimodal distribution, this case is representative of late-onset disease. Among patients diagnosed with Crohn disease, the first peak is seen between 15 and 30 years of age, whereas the second peak, occurring in up to 15% of diagnoses, is observed mainly in women between 60 and 70 years of age. A significant proportion of Crohn disease cases are heritable. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing the condition than any other ethnic group.

According to American Gastroenterological Association guidelines, a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should be considered in older patients who present with diarrhea, rectal bleeding, urgency, abdominal pain, or weight loss. Fecal calprotectin or lactoferrin measurement may help identify patients who warrant further endoscopic evaluation. Colonoscopy is indicated for patients presenting with chronic diarrhea or hematochezia due to suspected IBD, microscopic colitis, or colorectal neoplasia.

Upon further workup for IBD, signs that suggest Crohn disease rather than ulcerative colitis (UC) are sparing of the rectum; discontinuous involvement with skip areas, deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Antiglycan antibodies are more prevalent in Crohn disease than in ulcerative colitis, but they are not sensitive. Weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are common in Crohn disease but uncommon in UC.

In treating Crohn disease among older adults, systemic corticosteroids are not indicated for maintenance therapy, though they may be used for induction therapy. When possible, nonsystemic corticosteroids should be used, or, if the phenotype prevents their use, early biological therapy. The decision to treat a patient with immunosuppressive drugs should be based on age, functional status, and comorbidities. Immunomodulatory treatments with lower risks for infection and cancer may be safer for patients with late-onset disease. For maintenance of remission, thiopurine monotherapy may be used, with consideration given to its risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers and lymphoma in older patients.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation and history, this is probably a case of Crohn disease. Considering that the age of onset of Crohn disease has a bimodal distribution, this case is representative of late-onset disease. Among patients diagnosed with Crohn disease, the first peak is seen between 15 and 30 years of age, whereas the second peak, occurring in up to 15% of diagnoses, is observed mainly in women between 60 and 70 years of age. A significant proportion of Crohn disease cases are heritable. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing the condition than any other ethnic group.

According to American Gastroenterological Association guidelines, a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should be considered in older patients who present with diarrhea, rectal bleeding, urgency, abdominal pain, or weight loss. Fecal calprotectin or lactoferrin measurement may help identify patients who warrant further endoscopic evaluation. Colonoscopy is indicated for patients presenting with chronic diarrhea or hematochezia due to suspected IBD, microscopic colitis, or colorectal neoplasia.

Upon further workup for IBD, signs that suggest Crohn disease rather than ulcerative colitis (UC) are sparing of the rectum; discontinuous involvement with skip areas, deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Antiglycan antibodies are more prevalent in Crohn disease than in ulcerative colitis, but they are not sensitive. Weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are common in Crohn disease but uncommon in UC.

In treating Crohn disease among older adults, systemic corticosteroids are not indicated for maintenance therapy, though they may be used for induction therapy. When possible, nonsystemic corticosteroids should be used, or, if the phenotype prevents their use, early biological therapy. The decision to treat a patient with immunosuppressive drugs should be based on age, functional status, and comorbidities. Immunomodulatory treatments with lower risks for infection and cancer may be safer for patients with late-onset disease. For maintenance of remission, thiopurine monotherapy may be used, with consideration given to its risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers and lymphoma in older patients.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation and history, this is probably a case of Crohn disease. Considering that the age of onset of Crohn disease has a bimodal distribution, this case is representative of late-onset disease. Among patients diagnosed with Crohn disease, the first peak is seen between 15 and 30 years of age, whereas the second peak, occurring in up to 15% of diagnoses, is observed mainly in women between 60 and 70 years of age. A significant proportion of Crohn disease cases are heritable. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing the condition than any other ethnic group.

According to American Gastroenterological Association guidelines, a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should be considered in older patients who present with diarrhea, rectal bleeding, urgency, abdominal pain, or weight loss. Fecal calprotectin or lactoferrin measurement may help identify patients who warrant further endoscopic evaluation. Colonoscopy is indicated for patients presenting with chronic diarrhea or hematochezia due to suspected IBD, microscopic colitis, or colorectal neoplasia.

Upon further workup for IBD, signs that suggest Crohn disease rather than ulcerative colitis (UC) are sparing of the rectum; discontinuous involvement with skip areas, deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Antiglycan antibodies are more prevalent in Crohn disease than in ulcerative colitis, but they are not sensitive. Weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are common in Crohn disease but uncommon in UC.

In treating Crohn disease among older adults, systemic corticosteroids are not indicated for maintenance therapy, though they may be used for induction therapy. When possible, nonsystemic corticosteroids should be used, or, if the phenotype prevents their use, early biological therapy. The decision to treat a patient with immunosuppressive drugs should be based on age, functional status, and comorbidities. Immunomodulatory treatments with lower risks for infection and cancer may be safer for patients with late-onset disease. For maintenance of remission, thiopurine monotherapy may be used, with consideration given to its risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers and lymphoma in older patients.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 65-year-old woman presents with diarrhea which began several months ago, abdominal pain, and a 10-lb weight loss. Height is 5 ft 3 in and weight is 120 lb (BMI 21.3). The patient notes that she typically does not have a sensitive stomach and is concerned by the onset of symptoms. Current medications are levothyroxine, alendronic acid, and hydrochlorothiazide. Family history is notable for pancreatic cancer on her mother's side; her daughter has celiac disease. She is of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. Body temperature is 100.2 °F and hemoglobin level is 12.9 g/dL. Colonoscopy shows ileitis with skip areas. Lab analysis is remarkable for antiglycan antibodies.

Crohn Disease Treatment

Abdominal cramping and diarrhea

On the basis of the patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is extensive UC. Extensive colitis is defined by the presence of disease activity proximal to the splenic flexure. Because disease activity in UC is dynamic, up to half of patients who present with proctitis and 70% of those who present with left-sided colitis go on to develop extensive colitis on follow-up.

On the basis of the workup, it appears that this patient's UC has transitioned from left-sided to extensive disease, given the loss of treatment response. Endoscopic evaluation of patients with loss of treatment response may reveal patchiness of the histologic activity, as seen in this case.

Extensive colitis is a poor prognostic factor in UC, as is systemic steroid requirement, young age at diagnosis, and an elevated C-reactive protein level or erythrocyte sedimentation rate, all of which are associated with higher rates of colectomy. Over time, patients living with extensive ulcerative colitis develop an increased risk for colorectal cancer. Routine colonoscopic screening and surveillance are recommended for these high-risk patients.

UC most often presents as a continuously inflamed segment involving the distal rectum and extending proximally. Endoscopic features of inflammation include loss of vascular markings; granularity and friability of the mucosa; erosions; and, in the setting of severe inflammation, ulcerations and spontaneous bleeding. The diagnosis of UC involves both a lower gastrointestinal endoscopic examination and histologic confirmation. In general, a complete colonoscopy including examination of the terminal ileum should be performed, allowing clinicians to assess the full extent of the disease while ruling out distal ileal involvement, which is characteristic of Crohn's disease.

Evaluation of UC during relapses should include assessment of symptom severity and potential triggers, including enteric infections, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and recent smoking cessation. Nonadherence to therapy is common in patients with UC and may lead to relapse.

To treat a patient like the one represented here, the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines recommend oral 5-ASA at a dose of at least 2 g/d to induce remission. However, because this patient lost response to this treatment, the next step in the guidelines are appropriate oral systemic corticosteroids.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

On the basis of the patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is extensive UC. Extensive colitis is defined by the presence of disease activity proximal to the splenic flexure. Because disease activity in UC is dynamic, up to half of patients who present with proctitis and 70% of those who present with left-sided colitis go on to develop extensive colitis on follow-up.

On the basis of the workup, it appears that this patient's UC has transitioned from left-sided to extensive disease, given the loss of treatment response. Endoscopic evaluation of patients with loss of treatment response may reveal patchiness of the histologic activity, as seen in this case.

Extensive colitis is a poor prognostic factor in UC, as is systemic steroid requirement, young age at diagnosis, and an elevated C-reactive protein level or erythrocyte sedimentation rate, all of which are associated with higher rates of colectomy. Over time, patients living with extensive ulcerative colitis develop an increased risk for colorectal cancer. Routine colonoscopic screening and surveillance are recommended for these high-risk patients.

UC most often presents as a continuously inflamed segment involving the distal rectum and extending proximally. Endoscopic features of inflammation include loss of vascular markings; granularity and friability of the mucosa; erosions; and, in the setting of severe inflammation, ulcerations and spontaneous bleeding. The diagnosis of UC involves both a lower gastrointestinal endoscopic examination and histologic confirmation. In general, a complete colonoscopy including examination of the terminal ileum should be performed, allowing clinicians to assess the full extent of the disease while ruling out distal ileal involvement, which is characteristic of Crohn's disease.

Evaluation of UC during relapses should include assessment of symptom severity and potential triggers, including enteric infections, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and recent smoking cessation. Nonadherence to therapy is common in patients with UC and may lead to relapse.

To treat a patient like the one represented here, the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines recommend oral 5-ASA at a dose of at least 2 g/d to induce remission. However, because this patient lost response to this treatment, the next step in the guidelines are appropriate oral systemic corticosteroids.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

On the basis of the patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is extensive UC. Extensive colitis is defined by the presence of disease activity proximal to the splenic flexure. Because disease activity in UC is dynamic, up to half of patients who present with proctitis and 70% of those who present with left-sided colitis go on to develop extensive colitis on follow-up.

On the basis of the workup, it appears that this patient's UC has transitioned from left-sided to extensive disease, given the loss of treatment response. Endoscopic evaluation of patients with loss of treatment response may reveal patchiness of the histologic activity, as seen in this case.

Extensive colitis is a poor prognostic factor in UC, as is systemic steroid requirement, young age at diagnosis, and an elevated C-reactive protein level or erythrocyte sedimentation rate, all of which are associated with higher rates of colectomy. Over time, patients living with extensive ulcerative colitis develop an increased risk for colorectal cancer. Routine colonoscopic screening and surveillance are recommended for these high-risk patients.

UC most often presents as a continuously inflamed segment involving the distal rectum and extending proximally. Endoscopic features of inflammation include loss of vascular markings; granularity and friability of the mucosa; erosions; and, in the setting of severe inflammation, ulcerations and spontaneous bleeding. The diagnosis of UC involves both a lower gastrointestinal endoscopic examination and histologic confirmation. In general, a complete colonoscopy including examination of the terminal ileum should be performed, allowing clinicians to assess the full extent of the disease while ruling out distal ileal involvement, which is characteristic of Crohn's disease.

Evaluation of UC during relapses should include assessment of symptom severity and potential triggers, including enteric infections, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and recent smoking cessation. Nonadherence to therapy is common in patients with UC and may lead to relapse.

To treat a patient like the one represented here, the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines recommend oral 5-ASA at a dose of at least 2 g/d to induce remission. However, because this patient lost response to this treatment, the next step in the guidelines are appropriate oral systemic corticosteroids.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 46-year-old man presents with abdominal cramping and diarrhea and reports about five bowel movements per day for the past 2 weeks. Height is 5 ft 9 in and weight is 157 lb (BMI, 23.2). History is significant for ulcerative colitis (UC), diagnosed about 20 years ago with proctitis and having progressed about 8 years ago to left-sided disease. He smoked "lightly" through his 20s. Until about a month ago, the patient had been able to maintain remission with oral 5-aminosalicylic acid (ASA) therapy (2 g/d). Endoscopy shows granularity and friability of the mucosa with the inflamed segment extending proximal to the splenic flexure, though there is patchiness of the histologic activity. Colonoscopy rules out distal ileal involvement. Stool culture is negative.

Ulcerative Colitis Treatment

Symptoms of fatigue and abdominal pain

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that is becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide. It is estimated to affect three to 20 persons per 100,000. When not effectively managed, Crohn disease is associated with substantial morbidity and significant impairments in lifestyle and daily activities during flares and remissions. It is characterized by a transmural granulomatous inflammation that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract — usually, the ileum, colon, or both.

Abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue are often prominent symptoms in patients with Crohn disease. Crampy or steady right lower quadrant or periumbilical pain may develop; the pain both precedes and may be partially relieved by defecation. Diarrhea is frequently intermittent and is not usually grossly bloody. Diffuse abdominal pain accompanied by mucus, blood, and pus in the stool may be reported by patients if the colon is involved. Involvement of the small intestine usually presents with evidence of malabsorption, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and anorexia, which may be subtle early in the disease course. Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are more common in patients with gastroduodenal involvement, whereas debilitating perirectal pain, malodorous discharge from a fistula, and disfiguring scars from active disease or previous surgery may be present in patients with perianal disease. Patients may also present with symptoms suggestive of intestinal obstruction, or with anemia, recurrent fistulas, or fever.

As stated in guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), multiple streams of information, including history and physical examination, laboratory tests, endoscopy results, pathology findings, and radiographic tests, must be incorporated to arrive at a clinical diagnosis of Crohn disease. In most cases, the presence of chronic intestinal inflammation solidifies a diagnosis of Crohn disease. However, it can be challenging to differentiate Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis, particularly when the inflammation is confined to the colon. Bleeding is much more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn disease, whereas intestinal obstruction is common in Crohn disease and uncommon in ulcerative colitis. Fistulae and perianal disease are common in Crohn disease but are absent or rare in ulcerative colitis. Moreover, weight loss is typical in patients with Crohn disease but is uncommon in ulcerative colitis.

Additional diagnostic clues for Crohn disease include discontinuous involvement with skip areas; sparing of the rectum; deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Only a small percentage of patients have granulomas on biopsy. The presence of ileitis in a patient with extensive colitis (ie, backwash ileitis) can also make determining the inflammatory bowel disease subtype challenging.

Arthropathy (both axial and peripheral) is a classic extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease, as are dermatologic manifestations (including pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum); ocular manifestations (including uveitis, scleritis, and episcleritis); and hepatobiliary disease (ie, primary sclerosing cholangitis). Less common extraintestinal complications of Crohn disease include:

• Thromboembolism (both venous and arterial)

• Metabolic bone diseases

• Osteonecrosis

• Cholelithiasis

• Nephrolithiasis.

Only 20%-30% of patients with Crohn disease will have a nonprogressive or indolent course. Clinical features that are associated with a high risk for progressive disease burden include young age at diagnosis, initial extensive bowel involvement, ileal or ileocolonic involvement, perianal or severe rectal disease, and a penetrating or stenosis disease phenotype.

According to the AGA's Clinical Care Pathway for Crohn Disease, clinical laboratory testing in a patient with symptoms of Crohn disease should include:

• Complete blood cell count (anemia and leukocytosis are the most common abnormalities seen)

• C-reactive protein (not a specific marker, but may correlate with disease activity in a subset of patients)

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Fecal calprotectin (may correlate with intestinal inflammation; can help distinguish inflammatory bowel disorders from irritable bowel syndrome)

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (may be elevated in some patients; not a specific marker)

Ileocolonoscopy with biopsies should be performed in the evaluation of patients with suspected Crohn disease, and disease distribution and severity should be documented at the time of diagnosis. Biopsies of uninvolved mucosa are recommended to identify the extent of histologic disease.

Consult the AGA guidelines for more extensive details on the workup for Crohn disease, including indications for additional imaging and phenotypic classification.

In recent years, outcomes in Crohn disease have improved, which is probably the result of earlier diagnosis, increasing use of biologics, escalation or alteration of therapy based on disease severity, and endoscopic management of colorectal cancer. As noted above, Crohn disease includes multiple phenotypes, characterized by the Montreal Classification as stricturing, penetrating, inflammatory (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating), and perianal disease. Each of these phenotypes can present with a range in severity from mild to severe disease.

In general, therapeutic recommendations for patients are based on disease location, disease severity, disease-associated complications, and future disease prognosis and are individualized according to the symptomatic response and tolerance. Current therapeutic approaches should be considered a sequential continuum to treat acute disease or induce clinical remission, then maintain response or remission. Pharmacologic options include antidiarrheal agents, anti-inflammatory therapies (eg, sulfasalazine, mesalamine), corticosteroids (a short course for severe disease), biologic therapies (eg, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, natalizumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab), and occasionally immunosuppressive agents (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil). In addition to their 2014 guidelines on the management of Crohn disease in adults, the AGA recently released guidelines specific to the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and fistulizing Crohn disease.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that is becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide. It is estimated to affect three to 20 persons per 100,000. When not effectively managed, Crohn disease is associated with substantial morbidity and significant impairments in lifestyle and daily activities during flares and remissions. It is characterized by a transmural granulomatous inflammation that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract — usually, the ileum, colon, or both.

Abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue are often prominent symptoms in patients with Crohn disease. Crampy or steady right lower quadrant or periumbilical pain may develop; the pain both precedes and may be partially relieved by defecation. Diarrhea is frequently intermittent and is not usually grossly bloody. Diffuse abdominal pain accompanied by mucus, blood, and pus in the stool may be reported by patients if the colon is involved. Involvement of the small intestine usually presents with evidence of malabsorption, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and anorexia, which may be subtle early in the disease course. Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are more common in patients with gastroduodenal involvement, whereas debilitating perirectal pain, malodorous discharge from a fistula, and disfiguring scars from active disease or previous surgery may be present in patients with perianal disease. Patients may also present with symptoms suggestive of intestinal obstruction, or with anemia, recurrent fistulas, or fever.

As stated in guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), multiple streams of information, including history and physical examination, laboratory tests, endoscopy results, pathology findings, and radiographic tests, must be incorporated to arrive at a clinical diagnosis of Crohn disease. In most cases, the presence of chronic intestinal inflammation solidifies a diagnosis of Crohn disease. However, it can be challenging to differentiate Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis, particularly when the inflammation is confined to the colon. Bleeding is much more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn disease, whereas intestinal obstruction is common in Crohn disease and uncommon in ulcerative colitis. Fistulae and perianal disease are common in Crohn disease but are absent or rare in ulcerative colitis. Moreover, weight loss is typical in patients with Crohn disease but is uncommon in ulcerative colitis.

Additional diagnostic clues for Crohn disease include discontinuous involvement with skip areas; sparing of the rectum; deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Only a small percentage of patients have granulomas on biopsy. The presence of ileitis in a patient with extensive colitis (ie, backwash ileitis) can also make determining the inflammatory bowel disease subtype challenging.

Arthropathy (both axial and peripheral) is a classic extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease, as are dermatologic manifestations (including pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum); ocular manifestations (including uveitis, scleritis, and episcleritis); and hepatobiliary disease (ie, primary sclerosing cholangitis). Less common extraintestinal complications of Crohn disease include:

• Thromboembolism (both venous and arterial)

• Metabolic bone diseases

• Osteonecrosis

• Cholelithiasis

• Nephrolithiasis.

Only 20%-30% of patients with Crohn disease will have a nonprogressive or indolent course. Clinical features that are associated with a high risk for progressive disease burden include young age at diagnosis, initial extensive bowel involvement, ileal or ileocolonic involvement, perianal or severe rectal disease, and a penetrating or stenosis disease phenotype.

According to the AGA's Clinical Care Pathway for Crohn Disease, clinical laboratory testing in a patient with symptoms of Crohn disease should include:

• Complete blood cell count (anemia and leukocytosis are the most common abnormalities seen)

• C-reactive protein (not a specific marker, but may correlate with disease activity in a subset of patients)

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Fecal calprotectin (may correlate with intestinal inflammation; can help distinguish inflammatory bowel disorders from irritable bowel syndrome)

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (may be elevated in some patients; not a specific marker)

Ileocolonoscopy with biopsies should be performed in the evaluation of patients with suspected Crohn disease, and disease distribution and severity should be documented at the time of diagnosis. Biopsies of uninvolved mucosa are recommended to identify the extent of histologic disease.

Consult the AGA guidelines for more extensive details on the workup for Crohn disease, including indications for additional imaging and phenotypic classification.

In recent years, outcomes in Crohn disease have improved, which is probably the result of earlier diagnosis, increasing use of biologics, escalation or alteration of therapy based on disease severity, and endoscopic management of colorectal cancer. As noted above, Crohn disease includes multiple phenotypes, characterized by the Montreal Classification as stricturing, penetrating, inflammatory (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating), and perianal disease. Each of these phenotypes can present with a range in severity from mild to severe disease.

In general, therapeutic recommendations for patients are based on disease location, disease severity, disease-associated complications, and future disease prognosis and are individualized according to the symptomatic response and tolerance. Current therapeutic approaches should be considered a sequential continuum to treat acute disease or induce clinical remission, then maintain response or remission. Pharmacologic options include antidiarrheal agents, anti-inflammatory therapies (eg, sulfasalazine, mesalamine), corticosteroids (a short course for severe disease), biologic therapies (eg, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, natalizumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab), and occasionally immunosuppressive agents (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil). In addition to their 2014 guidelines on the management of Crohn disease in adults, the AGA recently released guidelines specific to the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and fistulizing Crohn disease.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that is becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide. It is estimated to affect three to 20 persons per 100,000. When not effectively managed, Crohn disease is associated with substantial morbidity and significant impairments in lifestyle and daily activities during flares and remissions. It is characterized by a transmural granulomatous inflammation that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract — usually, the ileum, colon, or both.

Abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue are often prominent symptoms in patients with Crohn disease. Crampy or steady right lower quadrant or periumbilical pain may develop; the pain both precedes and may be partially relieved by defecation. Diarrhea is frequently intermittent and is not usually grossly bloody. Diffuse abdominal pain accompanied by mucus, blood, and pus in the stool may be reported by patients if the colon is involved. Involvement of the small intestine usually presents with evidence of malabsorption, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and anorexia, which may be subtle early in the disease course. Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are more common in patients with gastroduodenal involvement, whereas debilitating perirectal pain, malodorous discharge from a fistula, and disfiguring scars from active disease or previous surgery may be present in patients with perianal disease. Patients may also present with symptoms suggestive of intestinal obstruction, or with anemia, recurrent fistulas, or fever.

As stated in guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), multiple streams of information, including history and physical examination, laboratory tests, endoscopy results, pathology findings, and radiographic tests, must be incorporated to arrive at a clinical diagnosis of Crohn disease. In most cases, the presence of chronic intestinal inflammation solidifies a diagnosis of Crohn disease. However, it can be challenging to differentiate Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis, particularly when the inflammation is confined to the colon. Bleeding is much more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn disease, whereas intestinal obstruction is common in Crohn disease and uncommon in ulcerative colitis. Fistulae and perianal disease are common in Crohn disease but are absent or rare in ulcerative colitis. Moreover, weight loss is typical in patients with Crohn disease but is uncommon in ulcerative colitis.

Additional diagnostic clues for Crohn disease include discontinuous involvement with skip areas; sparing of the rectum; deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Only a small percentage of patients have granulomas on biopsy. The presence of ileitis in a patient with extensive colitis (ie, backwash ileitis) can also make determining the inflammatory bowel disease subtype challenging.

Arthropathy (both axial and peripheral) is a classic extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease, as are dermatologic manifestations (including pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum); ocular manifestations (including uveitis, scleritis, and episcleritis); and hepatobiliary disease (ie, primary sclerosing cholangitis). Less common extraintestinal complications of Crohn disease include:

• Thromboembolism (both venous and arterial)

• Metabolic bone diseases

• Osteonecrosis

• Cholelithiasis

• Nephrolithiasis.

Only 20%-30% of patients with Crohn disease will have a nonprogressive or indolent course. Clinical features that are associated with a high risk for progressive disease burden include young age at diagnosis, initial extensive bowel involvement, ileal or ileocolonic involvement, perianal or severe rectal disease, and a penetrating or stenosis disease phenotype.

According to the AGA's Clinical Care Pathway for Crohn Disease, clinical laboratory testing in a patient with symptoms of Crohn disease should include:

• Complete blood cell count (anemia and leukocytosis are the most common abnormalities seen)

• C-reactive protein (not a specific marker, but may correlate with disease activity in a subset of patients)

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Fecal calprotectin (may correlate with intestinal inflammation; can help distinguish inflammatory bowel disorders from irritable bowel syndrome)

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (may be elevated in some patients; not a specific marker)

Ileocolonoscopy with biopsies should be performed in the evaluation of patients with suspected Crohn disease, and disease distribution and severity should be documented at the time of diagnosis. Biopsies of uninvolved mucosa are recommended to identify the extent of histologic disease.

Consult the AGA guidelines for more extensive details on the workup for Crohn disease, including indications for additional imaging and phenotypic classification.

In recent years, outcomes in Crohn disease have improved, which is probably the result of earlier diagnosis, increasing use of biologics, escalation or alteration of therapy based on disease severity, and endoscopic management of colorectal cancer. As noted above, Crohn disease includes multiple phenotypes, characterized by the Montreal Classification as stricturing, penetrating, inflammatory (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating), and perianal disease. Each of these phenotypes can present with a range in severity from mild to severe disease.

In general, therapeutic recommendations for patients are based on disease location, disease severity, disease-associated complications, and future disease prognosis and are individualized according to the symptomatic response and tolerance. Current therapeutic approaches should be considered a sequential continuum to treat acute disease or induce clinical remission, then maintain response or remission. Pharmacologic options include antidiarrheal agents, anti-inflammatory therapies (eg, sulfasalazine, mesalamine), corticosteroids (a short course for severe disease), biologic therapies (eg, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, natalizumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab), and occasionally immunosuppressive agents (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil). In addition to their 2014 guidelines on the management of Crohn disease in adults, the AGA recently released guidelines specific to the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and fistulizing Crohn disease.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

An 18-year-old man presents with increasing fatigue, prolonged diarrhea, and intermittent abdominal pain. The patient is nearly 6 months into his freshman year at the local university, where he resides. He states that his symptoms began approximately 12 weeks earlier. He describes passing an average of eight to 10 watery stools per day, including nocturnal diarrhea, with no noticeable blood or mucus and no rectal urgency. The patient has lost 13 lb since his symptoms began, which he attributes to the diarrhea and to adjusting to dormitory life and institutional meals. He also notes a slight decrease in appetite. His symptoms typically begin within an hour of awakening, after he has had his morning meal. The patient admits to smoking and occasional use of cannabis. He is not taking any medications or over-the-counter products.

Physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 120/70 mm Hg, pulse of 74 beats/min, and temperature of 98.4 °F (37 °C). His weight is 139 lb and his height is 5 ft 10 in. Diffuse abdominal tenderness is present; inspection of the perianal region and rectal examination are normal. There is a positive first-degree family history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and inflammatory bowel disease. His paternal grandmother died of colon cancer at 77 years of age and his maternal grandfather died of ischemic stroke at 82 years of age.

Laboratory findings are all within the normal range and stool testing excludes infectious etiologies. Subsequent endoscopic findings include multiple colonic ulcers longitudinally arranged with a cobblestone appearance.