User login

The American Journal of Orthopedics is an Index Medicus publication that is valued by orthopedic surgeons for its peer-reviewed, practice-oriented clinical information. Most articles are written by specialists at leading teaching institutions and help incorporate the latest technology into everyday practice.

Editorial Board Biographies

Struan H. Coleman, MD, PhD

Associate Editor for Practice Management/Economics

Dr. Coleman is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon specializing in hip preservation and sports medicine at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York and the Vincera Institute in Philadelphia, and currently is the Head Team Physician for the New York Mets. He earned a medical degree from Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons and holds a D.Phil in Microbiology from Oxford University in England. He completed his residency in Orthopedic Surgery and a fellowship in Sports Medicine at the Hospital for Special Surgery. Dr. Coleman focuses on the treatment of sports-related injuries of the hip, knee, and shoulder with a particular interest in hip arthroscopy and hip preservation. He has published multiple articles and book chapters, and holds numerous patents for technologies that are utilized by sports medicine physicians and surgeons.

Jack Farr II, MD

Associate Editor for Patellofemoral

Dr. Farr is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon and has a subspecialty practice in knee and cartilage restoration. He is affiliated with the OrthoIndy Hospital and Community Hospital South. He is also the Vice President of the Patellofemoral Foundation, is on the board for the International Cartilage Repair Society, holds a board position with the Cartilage Research Foundation, and holds a voluntary clinical full professorship in Orthopedic Surgery at the Indiana University Medical Center. Dr. Farr earned his medical degree from Indiana University, and completed his Orthopedic Surgery residency at Indiana University Medical Center. He was a design surgeon for a meniscal allograft transplant system and 2 knee patellofemoral osteotomy systems. He is also a member of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), the Arthroscopy Association of North America (AANA), and the European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy (ESSKA).

Kenneth Montgomery, MD

Associate Editor for Professional Sports

Dr. Montgomery is an orthopedic surgeon who is fellowship-trained in sports medicine and hand and upper extremity surgery. He is currently practicing at Tri-County Orthopedics and Sports Medicine in Morristown, New Jersey. He is also the Head Team Physician and Medical Director for the New York Jets. He served as a team orthopedist with the New York Islanders from 1997-2009, and was formerly the section chief of Sports Medicine at ProHEALTH Care Associates in Lake Success, New York. Dr. Montgomery completed his residency in Orthopedic Surgery at the Hospital for Special Surgery, and completed a Sports Medicine fellowship at Lenox Hill Hospital. He also completed a Hand and Upper Extremity fellowship at Harvard. He is one of the founders for OrthoNations, a nonprofit organization that helps educate orthopedic surgeons in developing countries. He is also one of the founding surgeons for Cayenne Medical, a medical device company specializing in sports medicine implants.

Struan H. Coleman, MD, PhD

Associate Editor for Practice Management/Economics

Dr. Coleman is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon specializing in hip preservation and sports medicine at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York and the Vincera Institute in Philadelphia, and currently is the Head Team Physician for the New York Mets. He earned a medical degree from Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons and holds a D.Phil in Microbiology from Oxford University in England. He completed his residency in Orthopedic Surgery and a fellowship in Sports Medicine at the Hospital for Special Surgery. Dr. Coleman focuses on the treatment of sports-related injuries of the hip, knee, and shoulder with a particular interest in hip arthroscopy and hip preservation. He has published multiple articles and book chapters, and holds numerous patents for technologies that are utilized by sports medicine physicians and surgeons.

Jack Farr II, MD

Associate Editor for Patellofemoral

Dr. Farr is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon and has a subspecialty practice in knee and cartilage restoration. He is affiliated with the OrthoIndy Hospital and Community Hospital South. He is also the Vice President of the Patellofemoral Foundation, is on the board for the International Cartilage Repair Society, holds a board position with the Cartilage Research Foundation, and holds a voluntary clinical full professorship in Orthopedic Surgery at the Indiana University Medical Center. Dr. Farr earned his medical degree from Indiana University, and completed his Orthopedic Surgery residency at Indiana University Medical Center. He was a design surgeon for a meniscal allograft transplant system and 2 knee patellofemoral osteotomy systems. He is also a member of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), the Arthroscopy Association of North America (AANA), and the European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy (ESSKA).

Kenneth Montgomery, MD

Associate Editor for Professional Sports

Dr. Montgomery is an orthopedic surgeon who is fellowship-trained in sports medicine and hand and upper extremity surgery. He is currently practicing at Tri-County Orthopedics and Sports Medicine in Morristown, New Jersey. He is also the Head Team Physician and Medical Director for the New York Jets. He served as a team orthopedist with the New York Islanders from 1997-2009, and was formerly the section chief of Sports Medicine at ProHEALTH Care Associates in Lake Success, New York. Dr. Montgomery completed his residency in Orthopedic Surgery at the Hospital for Special Surgery, and completed a Sports Medicine fellowship at Lenox Hill Hospital. He also completed a Hand and Upper Extremity fellowship at Harvard. He is one of the founders for OrthoNations, a nonprofit organization that helps educate orthopedic surgeons in developing countries. He is also one of the founding surgeons for Cayenne Medical, a medical device company specializing in sports medicine implants.

Struan H. Coleman, MD, PhD

Associate Editor for Practice Management/Economics

Dr. Coleman is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon specializing in hip preservation and sports medicine at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York and the Vincera Institute in Philadelphia, and currently is the Head Team Physician for the New York Mets. He earned a medical degree from Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons and holds a D.Phil in Microbiology from Oxford University in England. He completed his residency in Orthopedic Surgery and a fellowship in Sports Medicine at the Hospital for Special Surgery. Dr. Coleman focuses on the treatment of sports-related injuries of the hip, knee, and shoulder with a particular interest in hip arthroscopy and hip preservation. He has published multiple articles and book chapters, and holds numerous patents for technologies that are utilized by sports medicine physicians and surgeons.

Jack Farr II, MD

Associate Editor for Patellofemoral

Dr. Farr is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon and has a subspecialty practice in knee and cartilage restoration. He is affiliated with the OrthoIndy Hospital and Community Hospital South. He is also the Vice President of the Patellofemoral Foundation, is on the board for the International Cartilage Repair Society, holds a board position with the Cartilage Research Foundation, and holds a voluntary clinical full professorship in Orthopedic Surgery at the Indiana University Medical Center. Dr. Farr earned his medical degree from Indiana University, and completed his Orthopedic Surgery residency at Indiana University Medical Center. He was a design surgeon for a meniscal allograft transplant system and 2 knee patellofemoral osteotomy systems. He is also a member of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), the Arthroscopy Association of North America (AANA), and the European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy (ESSKA).

Kenneth Montgomery, MD

Associate Editor for Professional Sports

Dr. Montgomery is an orthopedic surgeon who is fellowship-trained in sports medicine and hand and upper extremity surgery. He is currently practicing at Tri-County Orthopedics and Sports Medicine in Morristown, New Jersey. He is also the Head Team Physician and Medical Director for the New York Jets. He served as a team orthopedist with the New York Islanders from 1997-2009, and was formerly the section chief of Sports Medicine at ProHEALTH Care Associates in Lake Success, New York. Dr. Montgomery completed his residency in Orthopedic Surgery at the Hospital for Special Surgery, and completed a Sports Medicine fellowship at Lenox Hill Hospital. He also completed a Hand and Upper Extremity fellowship at Harvard. He is one of the founders for OrthoNations, a nonprofit organization that helps educate orthopedic surgeons in developing countries. He is also one of the founding surgeons for Cayenne Medical, a medical device company specializing in sports medicine implants.

Engineered Bone Graft

Exactech

Optecure+ccc

(http://www.exac.com/products/biologics/optecure-optecure-ccc)

Autogenous bone graft remains the standard for augmenting the surgical care of severe fractures, promoting spinal fusion, filling bone voids, and treating nonunions. However, lingering problems with donor site morbidity, volume limitation, increased operative time, and increased case complexity have led to the growing use of bone graft substitutes.1 These alternatives include allograft bone, demineralized bone matrix, calcium sulfate and calcium phosphate, bioglass, growth factors (rhBMP-2, rhBMP-7, rhPDGF, and PRP [platelet-rich plasma]), collagen matrix, and new cellular-based compounds using mesenchymal stem cells. Since each individual class of bone substitute falls short of the optimal blend of osteoconduction, osteoinduction, and osteogenesis, novel composite grafts have been developed to combine the convenience, durability, and flexibility of synthetic grafts with the biologic activity of native bone.

Optecure+ccc (Exactech) is an engineered composite bone graft that contains demineralized bone mixed with gamma irradiated cortical cancellous chips in an absorbable synthetic hydrogel matrix (Figure). When mixed with saline, blood, autogenous bone, bone marrow aspirate, or PRP, it becomes a surprisingly robust and malleable 3-dimensional matrix that allows easy bone void filling with excellent osteoconductive and osteoinductive characteristics. Each individual lot is tested for sterility and endotoxin levels to confirm safety as well as in vivo testing in athymic mice to confirm osteoinductive potential. Optecure+ccc has been successfully used to augment healing when combined with bone marrow aspirate in minimally invasive spine fusion surgery.2

Surgical pearl: I treat a large number of bicycle injuries on Nantucket; many are quite serious. I have found Optecure+ccc to be particularly useful during locked volar plating of severe distal radius wrist fractures as a way to restore and support radial length when autogenous bone access is limited. In this application, Optecure’s ability to expand and mold into a functional bone scaffold is critical to create a stable, stress-resistant fracture construct.

After exposure of the comminuted fracture line of the distal radius, gentle axial traction is applied and a small osteotome or freer is used to carefully wedge open the cortex to allow metaphyseal window access. The Optecure+ccc is mixed with either blood or bone marrow aspirate to reach a “grape nuts cereal”-like consistency and then carefully packed into the metaphyseal window to backfill the void. Multiplanar fluoroscopy is used to monitor graft placement and gradual joint line restoration. Traction is then released after the void is filled sufficiently to support the provisional reduction. Additional grafting with standard Optecure without bone chips can be used to fill more difficult-to-access areas. Both forms of Optecure are resistant to diluent migration, giving them good intraoperative behavior. Excess graft can be easily wiped away from the fracture site prior to plate application.

After elevation and restoration of the joint line, the locking volar plate is then affixed, wrist alignment confirmed fluoroscopically, and the procedure completed. The result is a well-filled void and an improved fracture construct. While Optecure+ccc has proven its battle readiness in wrist fracture surgery, I have also found it very helpful in reconstructing complex proximal humerus and clavicle fractures. Its unique combination of intraoperative versatility and durability provides a welcome edge in challenging cases.

1. Rodgers WB, Gerber EJ, Patterson JR. Fusion after minimally disruptive anterior lumbar interbody fusion: analysis of extreme lateral interbody fusion by computed tomography. SAS J. 2010;4(2):63-66.

2. Sasso RC, LeHuec JC, Shaffrey C; Spine Interbody Research Group. Iliac crest bone graft donor site pain after anterior lumbar interbody fusion: a prospective patient satisfaction outcome assessment. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18 Suppl:S77-S81.

Exactech

Optecure+ccc

(http://www.exac.com/products/biologics/optecure-optecure-ccc)

Autogenous bone graft remains the standard for augmenting the surgical care of severe fractures, promoting spinal fusion, filling bone voids, and treating nonunions. However, lingering problems with donor site morbidity, volume limitation, increased operative time, and increased case complexity have led to the growing use of bone graft substitutes.1 These alternatives include allograft bone, demineralized bone matrix, calcium sulfate and calcium phosphate, bioglass, growth factors (rhBMP-2, rhBMP-7, rhPDGF, and PRP [platelet-rich plasma]), collagen matrix, and new cellular-based compounds using mesenchymal stem cells. Since each individual class of bone substitute falls short of the optimal blend of osteoconduction, osteoinduction, and osteogenesis, novel composite grafts have been developed to combine the convenience, durability, and flexibility of synthetic grafts with the biologic activity of native bone.

Optecure+ccc (Exactech) is an engineered composite bone graft that contains demineralized bone mixed with gamma irradiated cortical cancellous chips in an absorbable synthetic hydrogel matrix (Figure). When mixed with saline, blood, autogenous bone, bone marrow aspirate, or PRP, it becomes a surprisingly robust and malleable 3-dimensional matrix that allows easy bone void filling with excellent osteoconductive and osteoinductive characteristics. Each individual lot is tested for sterility and endotoxin levels to confirm safety as well as in vivo testing in athymic mice to confirm osteoinductive potential. Optecure+ccc has been successfully used to augment healing when combined with bone marrow aspirate in minimally invasive spine fusion surgery.2

Surgical pearl: I treat a large number of bicycle injuries on Nantucket; many are quite serious. I have found Optecure+ccc to be particularly useful during locked volar plating of severe distal radius wrist fractures as a way to restore and support radial length when autogenous bone access is limited. In this application, Optecure’s ability to expand and mold into a functional bone scaffold is critical to create a stable, stress-resistant fracture construct.

After exposure of the comminuted fracture line of the distal radius, gentle axial traction is applied and a small osteotome or freer is used to carefully wedge open the cortex to allow metaphyseal window access. The Optecure+ccc is mixed with either blood or bone marrow aspirate to reach a “grape nuts cereal”-like consistency and then carefully packed into the metaphyseal window to backfill the void. Multiplanar fluoroscopy is used to monitor graft placement and gradual joint line restoration. Traction is then released after the void is filled sufficiently to support the provisional reduction. Additional grafting with standard Optecure without bone chips can be used to fill more difficult-to-access areas. Both forms of Optecure are resistant to diluent migration, giving them good intraoperative behavior. Excess graft can be easily wiped away from the fracture site prior to plate application.

After elevation and restoration of the joint line, the locking volar plate is then affixed, wrist alignment confirmed fluoroscopically, and the procedure completed. The result is a well-filled void and an improved fracture construct. While Optecure+ccc has proven its battle readiness in wrist fracture surgery, I have also found it very helpful in reconstructing complex proximal humerus and clavicle fractures. Its unique combination of intraoperative versatility and durability provides a welcome edge in challenging cases.

Exactech

Optecure+ccc

(http://www.exac.com/products/biologics/optecure-optecure-ccc)

Autogenous bone graft remains the standard for augmenting the surgical care of severe fractures, promoting spinal fusion, filling bone voids, and treating nonunions. However, lingering problems with donor site morbidity, volume limitation, increased operative time, and increased case complexity have led to the growing use of bone graft substitutes.1 These alternatives include allograft bone, demineralized bone matrix, calcium sulfate and calcium phosphate, bioglass, growth factors (rhBMP-2, rhBMP-7, rhPDGF, and PRP [platelet-rich plasma]), collagen matrix, and new cellular-based compounds using mesenchymal stem cells. Since each individual class of bone substitute falls short of the optimal blend of osteoconduction, osteoinduction, and osteogenesis, novel composite grafts have been developed to combine the convenience, durability, and flexibility of synthetic grafts with the biologic activity of native bone.

Optecure+ccc (Exactech) is an engineered composite bone graft that contains demineralized bone mixed with gamma irradiated cortical cancellous chips in an absorbable synthetic hydrogel matrix (Figure). When mixed with saline, blood, autogenous bone, bone marrow aspirate, or PRP, it becomes a surprisingly robust and malleable 3-dimensional matrix that allows easy bone void filling with excellent osteoconductive and osteoinductive characteristics. Each individual lot is tested for sterility and endotoxin levels to confirm safety as well as in vivo testing in athymic mice to confirm osteoinductive potential. Optecure+ccc has been successfully used to augment healing when combined with bone marrow aspirate in minimally invasive spine fusion surgery.2

Surgical pearl: I treat a large number of bicycle injuries on Nantucket; many are quite serious. I have found Optecure+ccc to be particularly useful during locked volar plating of severe distal radius wrist fractures as a way to restore and support radial length when autogenous bone access is limited. In this application, Optecure’s ability to expand and mold into a functional bone scaffold is critical to create a stable, stress-resistant fracture construct.

After exposure of the comminuted fracture line of the distal radius, gentle axial traction is applied and a small osteotome or freer is used to carefully wedge open the cortex to allow metaphyseal window access. The Optecure+ccc is mixed with either blood or bone marrow aspirate to reach a “grape nuts cereal”-like consistency and then carefully packed into the metaphyseal window to backfill the void. Multiplanar fluoroscopy is used to monitor graft placement and gradual joint line restoration. Traction is then released after the void is filled sufficiently to support the provisional reduction. Additional grafting with standard Optecure without bone chips can be used to fill more difficult-to-access areas. Both forms of Optecure are resistant to diluent migration, giving them good intraoperative behavior. Excess graft can be easily wiped away from the fracture site prior to plate application.

After elevation and restoration of the joint line, the locking volar plate is then affixed, wrist alignment confirmed fluoroscopically, and the procedure completed. The result is a well-filled void and an improved fracture construct. While Optecure+ccc has proven its battle readiness in wrist fracture surgery, I have also found it very helpful in reconstructing complex proximal humerus and clavicle fractures. Its unique combination of intraoperative versatility and durability provides a welcome edge in challenging cases.

1. Rodgers WB, Gerber EJ, Patterson JR. Fusion after minimally disruptive anterior lumbar interbody fusion: analysis of extreme lateral interbody fusion by computed tomography. SAS J. 2010;4(2):63-66.

2. Sasso RC, LeHuec JC, Shaffrey C; Spine Interbody Research Group. Iliac crest bone graft donor site pain after anterior lumbar interbody fusion: a prospective patient satisfaction outcome assessment. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18 Suppl:S77-S81.

1. Rodgers WB, Gerber EJ, Patterson JR. Fusion after minimally disruptive anterior lumbar interbody fusion: analysis of extreme lateral interbody fusion by computed tomography. SAS J. 2010;4(2):63-66.

2. Sasso RC, LeHuec JC, Shaffrey C; Spine Interbody Research Group. Iliac crest bone graft donor site pain after anterior lumbar interbody fusion: a prospective patient satisfaction outcome assessment. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18 Suppl:S77-S81.

The Arthroscopic Superior Capsular Reconstruction

Rotator cuff tears are very common, and 250,000 to 500,000 rotator cuff repairs are performed in the United States each year.1,2 In most cases, a complete repair of even large or massive tears can be achieved. However, a subset of patients exist in whom the glenohumeral joint has minimal degenerative changes and the rotator cuff tendon is either irreparable or very poor quality and unlikely to heal (ie, failed previous cuff repair). Some authors have advocated for reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) in these patients despite the lack of glenohumeral arthritis. However, due to the permanent destruction of the glenohumeral articular surfaces, complication rates, and concerns about implant longevity with RSA, we believe the superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) is a viable alternative in patients in whom joint preservation is appropriate based on age limitations and/or activity requirements.3

The SCR was first described by Mihata and colleagues4 as a means to reconstruct the superior capsule in shoulders with large, irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Originally described using a fascia lata autograft, our technique has been adapted to incorporate a dermal allograft, which limits donor site morbidity and operative time. In most cases, the dermal allograft is fixed to the normal anatomic attachments of the superior glenoid just medial to the superior labrum, laterally to the greater tuberosity, and posteriorly with side-to-side sutures to the remaining rotator cuff. If there is a robust band of “comma” tissue anteriorly, we fix the anterior margin of the dermal graft to this with side-to-side sutures. The comma tissue represents the medial sling of the biceps tendon and connects the upper subscapularis tendon to the anterior supraspinatus. In most cases, this tissue is intact after repair of the subscapularis tendon.

Technique

The patient is positioned in either the lateral decubitus or beach chair position. The arm is positioned in 20° to 30° of abduction and 20° to 30° of forward flexion. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed through a posterior glenohumeral viewing portal. The subscapularis is visualized and repaired if torn. A biceps tenodesis is performed in most cases, as there is often a tear of the subscapularis, tear or instability of the biceps tendon, and/or a compromised attachment of the biceps root.

Attention is turned to the subacromial space. Posterior viewing and lateral working portals are established. A 10-mm flexible cannula (PassPort; Arthrex) is placed in the lateral portal to aid with suture management and graft passage. A limited subacromial decompression is performed that preserves the coracoacromial arch. The rotator cuff is carefully dissected and freed from the internal deltoid fascia. The scapular spine is identified to visualize the raphé between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. The infraspinatus is mobilized and repaired as much as possible.

If we think that the tear might be reparable by gaining added excursion from a posterior interval slide, or if it is clearly not reparable but the remaining rim of rotator cuff obscures clear visualization of the superior glenoid, we perform a posterior interval slide. If the additional excursion that is achieved by the posterior slide is adequate for a complete repair, we proceed with the repair. However, if the tear is not reparable even after the posterior interval slide, we have found that the exposure and preparation of the superior glenoid is greatly improved after the posterior slide. After fixation of the dermal graft, we typically perform a partial side-to-side repair of the supraspinatus to the infraspinatus over the top of the graft.

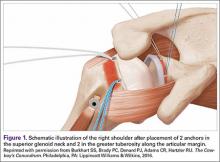

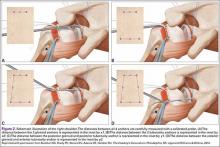

The bone beds of the greater tuberosity and just medial to the superior glenoid labrum are prepared with a shaver and motorized burr. Two anchors (3.0-mm BioComposite SutureTak; Arthrex) are placed in the superior glenoid neck at about the 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock positions approximately 5 mm medial to the superior labrum. Note: the placement medial to the labrum is chosen because this is the normal origin of the superior capsule and because of the angle of approach, these percutaneous portals are often more medial than typical portals for placing anchors during SLAP (superior labral anterior to posterior) repair. Next, 2 threaded anchors (4.75-mm BioComposite SwiveLock; Arthrex) preloaded with suture tape are placed in the greater tuberosity along the articular margin (Figure 1). However, if a biceps tenodesis with an interference screw is placed at the top of the bicipital groove, this anchor preloaded with suture tape can also serve as the anteromedial anchor in the greater tuberosity footprint. The distances between all 4 anchors are carefully measured with a calibrated probe (Figures 2A-2D).

We use a 3.0-mm acellular dermal allograft (ArthroFlex; Arthrex) to reconstruct the superior capsule. The positions of the 4 anchors are carefully marked on the dermal allograft. We routinely add an additional 5 mm of tissue to the medial, anterior, and posterior margins to decrease the risk of suture cut out. An additional 10 mm of tissue is added laterally to cover the greater tuberosity. The final contoured graft is typically trapezoidal in shape.

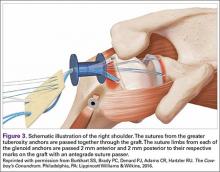

The sutures from the 4 anchors are then sequentially retrieved through the lateral cannula. The sutures from the greater tuberosity anchors are passed through their respective holes in the graft. However, the suture limbs from each of the glenoid anchors are individually passed 2 mm anterior and 2 mm posterior to their respective marks on the graft with an antegrade suture passer (Figure 3). It is important to have an assistant apply tension to each of the sutures after they are passed through the graft to decrease the chance of crossing and tangling the sutures.

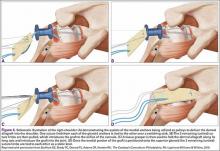

The eyelets of the medial anchors are utilized as pulleys to deliver the dermal allograft into the shoulder. One suture limb from each of the glenoid anchors is tied to the other over a switching stick (Figure 4A). The 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are then pulled, which introduces the graft to the orifice of the cannula (Figure 4B). A tissue grasper is then used to fold the dermal allograft along its long axis and introduce the graft into the joint (Figure 4C). Once the medial portion of the graft is positioned onto the superior glenoid the 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are tied to each other as a static knot in the subacromial space (Figure 4D).

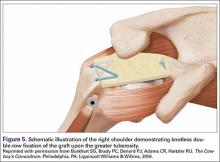

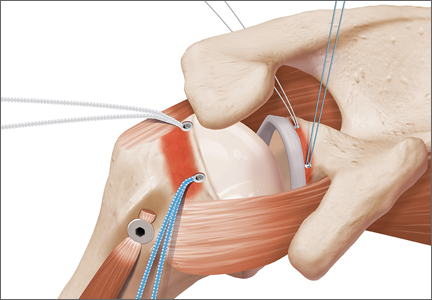

The redundancy in the suture tapes can be removed by sequentially sliding a retriever down each suture and tensioning the suture as the nose of the instrument pushes the dermal graft down to the tuberosity bone bed. The suture tapes are crisscrossed and secured laterally with 2 additional knotless threaded anchors (Figure 5). One may also place cinch stitches at the anterolateral and posterolateral corners of the graft that are incorporated into the lateral anchors. These sutures can be useful for pulling the graft back out of the subacromial space in the event of any suture tangles, and can be used for controlling the lateral aspect of the graft during lateral anchor placement.

At this point in the procedure, additional glenoid anchors can be placed both anterior and posterior to the superior glenoid anchors if additional glenoid fixation is desired. Finally, 2 to 3 side-to-side sutures are placed posteriorly attaching the anterior aspect of the infraspinatus to the posterior aspect of the dermal allograft (Figures 6A-6C). If rotator interval tissue (comma tissue) is present, anterior side-to-side sutures may be placed. However, we do not recommend placing anterior side-to-side sutures directly from the dermal allograft to the subscapularis as this may deform the graft, over- constrain the shoulder, and restrict motion.

Discussion

Reconstruction of the superior capsule has been shown to restore the normal restraint to superior translation of the humeral head and reestablish a stable fulcrum at the glenohumeral joint.5 It should be mentioned that we do not perform the SCR in patients with advanced glenohumeral arthritis. The short-term results of this novel procedure have been encouraging, including our own series of patients, in which most patients have had a significant reduction in pain, improvement in function, and very few complications (P. J. Denard, MD, S. S. Burkhart, MD, P. C. Brady, MD, J. Tokish, MD, C. R. Adams, MD, unpublished data, May 2016).

The early success of this procedure suggests that a robust superior capsule is necessary, in addition to functional muscle-tendon units, to restore the stable fulcrum and force couples that are necessary for normal shoulder function. Perhaps we have not paid enough attention to the integrity of the superior capsule in the past. In cases of revision cuff repair, we pay special attention to the quality of the capsular layer deep to the cuff tendon. If the capsule is poor quality, we sometimes reconstruct the capsule with a dermal allograft (SCR) and then do a rotator cuff repair (partial or complete) over the top of the SCR to maintain the normal anatomic deep to superficial layering of the capsule and rotator cuff.

We are very conservative with our postoperative rehabilitation program after a SCR. We know that the rate of stiffness with a conservative program after an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, even in the revision setting, is very low.6 Furthermore, both basic science on healing of soft tissue to bone and radiographic analysis of healing after postoperative rotator cuff repairs support a slow rehabilitation program.7,8 A canine model specifically evaluating acellular dermal allografts in the shoulder suggests that these grafts undergo significant remodeling and become weaker before they get stronger.9 We would rather err on the side of healing of the SCR with potentially a slight increase in the rate of shoulder stiffness than to regain early motion at the expense of graft failure. Therefore, we have the patient wear a sling with no shoulder motion for 6 weeks. Passive motion is started at 6 weeks postoperative and strengthening is delayed until 12 to 16 weeks postoperative.

1. Orr SB, Chainani A, Hippensteel KJ, et al. Aligned multilayered electrospun scaffolds for rotator cuff tendon tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2015;24:117-126.

2. Austin L, Black EM, Lombardi NJ, Pepe MD, Lazarus M. Arthroscopic transosseous rotator cuff repair. A prospective study on cost savings, surgical time, and outcomes. Ortho J Sports Med. 2015;3(2 Suppl). doi:10.1177/2325967115S00156.

3. Denard PJ, Lädermann A, Jiwani AZ, Burkhart SS. Functional outcome after arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears in individuals with pseudoparalysis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(9):1214-1219.

4. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459-470.

5. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2248-2255.

6. Huberty DP, Schoolfield JD, Brady PC, Vadala AP, Arrigoni P, Burkhart SS. Incidence and treatment of postoperative stiffness following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):880-890.

7. Sonnabend DH, Howlett CR, Young AA. Histological evaluation of repair of the rotator cuff in a primate model. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(4):586-594.

8. Lee BG, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Effect of two rehabilitation protocols on range of motion and healing rates after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: aggressive versus limited early passive exercises. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(1):34-42.

9. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS Jr, An KN, Steinmann SP. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: an in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.

Rotator cuff tears are very common, and 250,000 to 500,000 rotator cuff repairs are performed in the United States each year.1,2 In most cases, a complete repair of even large or massive tears can be achieved. However, a subset of patients exist in whom the glenohumeral joint has minimal degenerative changes and the rotator cuff tendon is either irreparable or very poor quality and unlikely to heal (ie, failed previous cuff repair). Some authors have advocated for reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) in these patients despite the lack of glenohumeral arthritis. However, due to the permanent destruction of the glenohumeral articular surfaces, complication rates, and concerns about implant longevity with RSA, we believe the superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) is a viable alternative in patients in whom joint preservation is appropriate based on age limitations and/or activity requirements.3

The SCR was first described by Mihata and colleagues4 as a means to reconstruct the superior capsule in shoulders with large, irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Originally described using a fascia lata autograft, our technique has been adapted to incorporate a dermal allograft, which limits donor site morbidity and operative time. In most cases, the dermal allograft is fixed to the normal anatomic attachments of the superior glenoid just medial to the superior labrum, laterally to the greater tuberosity, and posteriorly with side-to-side sutures to the remaining rotator cuff. If there is a robust band of “comma” tissue anteriorly, we fix the anterior margin of the dermal graft to this with side-to-side sutures. The comma tissue represents the medial sling of the biceps tendon and connects the upper subscapularis tendon to the anterior supraspinatus. In most cases, this tissue is intact after repair of the subscapularis tendon.

Technique

The patient is positioned in either the lateral decubitus or beach chair position. The arm is positioned in 20° to 30° of abduction and 20° to 30° of forward flexion. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed through a posterior glenohumeral viewing portal. The subscapularis is visualized and repaired if torn. A biceps tenodesis is performed in most cases, as there is often a tear of the subscapularis, tear or instability of the biceps tendon, and/or a compromised attachment of the biceps root.

Attention is turned to the subacromial space. Posterior viewing and lateral working portals are established. A 10-mm flexible cannula (PassPort; Arthrex) is placed in the lateral portal to aid with suture management and graft passage. A limited subacromial decompression is performed that preserves the coracoacromial arch. The rotator cuff is carefully dissected and freed from the internal deltoid fascia. The scapular spine is identified to visualize the raphé between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. The infraspinatus is mobilized and repaired as much as possible.

If we think that the tear might be reparable by gaining added excursion from a posterior interval slide, or if it is clearly not reparable but the remaining rim of rotator cuff obscures clear visualization of the superior glenoid, we perform a posterior interval slide. If the additional excursion that is achieved by the posterior slide is adequate for a complete repair, we proceed with the repair. However, if the tear is not reparable even after the posterior interval slide, we have found that the exposure and preparation of the superior glenoid is greatly improved after the posterior slide. After fixation of the dermal graft, we typically perform a partial side-to-side repair of the supraspinatus to the infraspinatus over the top of the graft.

The bone beds of the greater tuberosity and just medial to the superior glenoid labrum are prepared with a shaver and motorized burr. Two anchors (3.0-mm BioComposite SutureTak; Arthrex) are placed in the superior glenoid neck at about the 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock positions approximately 5 mm medial to the superior labrum. Note: the placement medial to the labrum is chosen because this is the normal origin of the superior capsule and because of the angle of approach, these percutaneous portals are often more medial than typical portals for placing anchors during SLAP (superior labral anterior to posterior) repair. Next, 2 threaded anchors (4.75-mm BioComposite SwiveLock; Arthrex) preloaded with suture tape are placed in the greater tuberosity along the articular margin (Figure 1). However, if a biceps tenodesis with an interference screw is placed at the top of the bicipital groove, this anchor preloaded with suture tape can also serve as the anteromedial anchor in the greater tuberosity footprint. The distances between all 4 anchors are carefully measured with a calibrated probe (Figures 2A-2D).

We use a 3.0-mm acellular dermal allograft (ArthroFlex; Arthrex) to reconstruct the superior capsule. The positions of the 4 anchors are carefully marked on the dermal allograft. We routinely add an additional 5 mm of tissue to the medial, anterior, and posterior margins to decrease the risk of suture cut out. An additional 10 mm of tissue is added laterally to cover the greater tuberosity. The final contoured graft is typically trapezoidal in shape.

The sutures from the 4 anchors are then sequentially retrieved through the lateral cannula. The sutures from the greater tuberosity anchors are passed through their respective holes in the graft. However, the suture limbs from each of the glenoid anchors are individually passed 2 mm anterior and 2 mm posterior to their respective marks on the graft with an antegrade suture passer (Figure 3). It is important to have an assistant apply tension to each of the sutures after they are passed through the graft to decrease the chance of crossing and tangling the sutures.

The eyelets of the medial anchors are utilized as pulleys to deliver the dermal allograft into the shoulder. One suture limb from each of the glenoid anchors is tied to the other over a switching stick (Figure 4A). The 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are then pulled, which introduces the graft to the orifice of the cannula (Figure 4B). A tissue grasper is then used to fold the dermal allograft along its long axis and introduce the graft into the joint (Figure 4C). Once the medial portion of the graft is positioned onto the superior glenoid the 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are tied to each other as a static knot in the subacromial space (Figure 4D).

The redundancy in the suture tapes can be removed by sequentially sliding a retriever down each suture and tensioning the suture as the nose of the instrument pushes the dermal graft down to the tuberosity bone bed. The suture tapes are crisscrossed and secured laterally with 2 additional knotless threaded anchors (Figure 5). One may also place cinch stitches at the anterolateral and posterolateral corners of the graft that are incorporated into the lateral anchors. These sutures can be useful for pulling the graft back out of the subacromial space in the event of any suture tangles, and can be used for controlling the lateral aspect of the graft during lateral anchor placement.

At this point in the procedure, additional glenoid anchors can be placed both anterior and posterior to the superior glenoid anchors if additional glenoid fixation is desired. Finally, 2 to 3 side-to-side sutures are placed posteriorly attaching the anterior aspect of the infraspinatus to the posterior aspect of the dermal allograft (Figures 6A-6C). If rotator interval tissue (comma tissue) is present, anterior side-to-side sutures may be placed. However, we do not recommend placing anterior side-to-side sutures directly from the dermal allograft to the subscapularis as this may deform the graft, over- constrain the shoulder, and restrict motion.

Discussion

Reconstruction of the superior capsule has been shown to restore the normal restraint to superior translation of the humeral head and reestablish a stable fulcrum at the glenohumeral joint.5 It should be mentioned that we do not perform the SCR in patients with advanced glenohumeral arthritis. The short-term results of this novel procedure have been encouraging, including our own series of patients, in which most patients have had a significant reduction in pain, improvement in function, and very few complications (P. J. Denard, MD, S. S. Burkhart, MD, P. C. Brady, MD, J. Tokish, MD, C. R. Adams, MD, unpublished data, May 2016).

The early success of this procedure suggests that a robust superior capsule is necessary, in addition to functional muscle-tendon units, to restore the stable fulcrum and force couples that are necessary for normal shoulder function. Perhaps we have not paid enough attention to the integrity of the superior capsule in the past. In cases of revision cuff repair, we pay special attention to the quality of the capsular layer deep to the cuff tendon. If the capsule is poor quality, we sometimes reconstruct the capsule with a dermal allograft (SCR) and then do a rotator cuff repair (partial or complete) over the top of the SCR to maintain the normal anatomic deep to superficial layering of the capsule and rotator cuff.

We are very conservative with our postoperative rehabilitation program after a SCR. We know that the rate of stiffness with a conservative program after an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, even in the revision setting, is very low.6 Furthermore, both basic science on healing of soft tissue to bone and radiographic analysis of healing after postoperative rotator cuff repairs support a slow rehabilitation program.7,8 A canine model specifically evaluating acellular dermal allografts in the shoulder suggests that these grafts undergo significant remodeling and become weaker before they get stronger.9 We would rather err on the side of healing of the SCR with potentially a slight increase in the rate of shoulder stiffness than to regain early motion at the expense of graft failure. Therefore, we have the patient wear a sling with no shoulder motion for 6 weeks. Passive motion is started at 6 weeks postoperative and strengthening is delayed until 12 to 16 weeks postoperative.

Rotator cuff tears are very common, and 250,000 to 500,000 rotator cuff repairs are performed in the United States each year.1,2 In most cases, a complete repair of even large or massive tears can be achieved. However, a subset of patients exist in whom the glenohumeral joint has minimal degenerative changes and the rotator cuff tendon is either irreparable or very poor quality and unlikely to heal (ie, failed previous cuff repair). Some authors have advocated for reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) in these patients despite the lack of glenohumeral arthritis. However, due to the permanent destruction of the glenohumeral articular surfaces, complication rates, and concerns about implant longevity with RSA, we believe the superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) is a viable alternative in patients in whom joint preservation is appropriate based on age limitations and/or activity requirements.3

The SCR was first described by Mihata and colleagues4 as a means to reconstruct the superior capsule in shoulders with large, irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Originally described using a fascia lata autograft, our technique has been adapted to incorporate a dermal allograft, which limits donor site morbidity and operative time. In most cases, the dermal allograft is fixed to the normal anatomic attachments of the superior glenoid just medial to the superior labrum, laterally to the greater tuberosity, and posteriorly with side-to-side sutures to the remaining rotator cuff. If there is a robust band of “comma” tissue anteriorly, we fix the anterior margin of the dermal graft to this with side-to-side sutures. The comma tissue represents the medial sling of the biceps tendon and connects the upper subscapularis tendon to the anterior supraspinatus. In most cases, this tissue is intact after repair of the subscapularis tendon.

Technique

The patient is positioned in either the lateral decubitus or beach chair position. The arm is positioned in 20° to 30° of abduction and 20° to 30° of forward flexion. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed through a posterior glenohumeral viewing portal. The subscapularis is visualized and repaired if torn. A biceps tenodesis is performed in most cases, as there is often a tear of the subscapularis, tear or instability of the biceps tendon, and/or a compromised attachment of the biceps root.

Attention is turned to the subacromial space. Posterior viewing and lateral working portals are established. A 10-mm flexible cannula (PassPort; Arthrex) is placed in the lateral portal to aid with suture management and graft passage. A limited subacromial decompression is performed that preserves the coracoacromial arch. The rotator cuff is carefully dissected and freed from the internal deltoid fascia. The scapular spine is identified to visualize the raphé between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. The infraspinatus is mobilized and repaired as much as possible.

If we think that the tear might be reparable by gaining added excursion from a posterior interval slide, or if it is clearly not reparable but the remaining rim of rotator cuff obscures clear visualization of the superior glenoid, we perform a posterior interval slide. If the additional excursion that is achieved by the posterior slide is adequate for a complete repair, we proceed with the repair. However, if the tear is not reparable even after the posterior interval slide, we have found that the exposure and preparation of the superior glenoid is greatly improved after the posterior slide. After fixation of the dermal graft, we typically perform a partial side-to-side repair of the supraspinatus to the infraspinatus over the top of the graft.

The bone beds of the greater tuberosity and just medial to the superior glenoid labrum are prepared with a shaver and motorized burr. Two anchors (3.0-mm BioComposite SutureTak; Arthrex) are placed in the superior glenoid neck at about the 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock positions approximately 5 mm medial to the superior labrum. Note: the placement medial to the labrum is chosen because this is the normal origin of the superior capsule and because of the angle of approach, these percutaneous portals are often more medial than typical portals for placing anchors during SLAP (superior labral anterior to posterior) repair. Next, 2 threaded anchors (4.75-mm BioComposite SwiveLock; Arthrex) preloaded with suture tape are placed in the greater tuberosity along the articular margin (Figure 1). However, if a biceps tenodesis with an interference screw is placed at the top of the bicipital groove, this anchor preloaded with suture tape can also serve as the anteromedial anchor in the greater tuberosity footprint. The distances between all 4 anchors are carefully measured with a calibrated probe (Figures 2A-2D).

We use a 3.0-mm acellular dermal allograft (ArthroFlex; Arthrex) to reconstruct the superior capsule. The positions of the 4 anchors are carefully marked on the dermal allograft. We routinely add an additional 5 mm of tissue to the medial, anterior, and posterior margins to decrease the risk of suture cut out. An additional 10 mm of tissue is added laterally to cover the greater tuberosity. The final contoured graft is typically trapezoidal in shape.

The sutures from the 4 anchors are then sequentially retrieved through the lateral cannula. The sutures from the greater tuberosity anchors are passed through their respective holes in the graft. However, the suture limbs from each of the glenoid anchors are individually passed 2 mm anterior and 2 mm posterior to their respective marks on the graft with an antegrade suture passer (Figure 3). It is important to have an assistant apply tension to each of the sutures after they are passed through the graft to decrease the chance of crossing and tangling the sutures.

The eyelets of the medial anchors are utilized as pulleys to deliver the dermal allograft into the shoulder. One suture limb from each of the glenoid anchors is tied to the other over a switching stick (Figure 4A). The 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are then pulled, which introduces the graft to the orifice of the cannula (Figure 4B). A tissue grasper is then used to fold the dermal allograft along its long axis and introduce the graft into the joint (Figure 4C). Once the medial portion of the graft is positioned onto the superior glenoid the 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are tied to each other as a static knot in the subacromial space (Figure 4D).

The redundancy in the suture tapes can be removed by sequentially sliding a retriever down each suture and tensioning the suture as the nose of the instrument pushes the dermal graft down to the tuberosity bone bed. The suture tapes are crisscrossed and secured laterally with 2 additional knotless threaded anchors (Figure 5). One may also place cinch stitches at the anterolateral and posterolateral corners of the graft that are incorporated into the lateral anchors. These sutures can be useful for pulling the graft back out of the subacromial space in the event of any suture tangles, and can be used for controlling the lateral aspect of the graft during lateral anchor placement.

At this point in the procedure, additional glenoid anchors can be placed both anterior and posterior to the superior glenoid anchors if additional glenoid fixation is desired. Finally, 2 to 3 side-to-side sutures are placed posteriorly attaching the anterior aspect of the infraspinatus to the posterior aspect of the dermal allograft (Figures 6A-6C). If rotator interval tissue (comma tissue) is present, anterior side-to-side sutures may be placed. However, we do not recommend placing anterior side-to-side sutures directly from the dermal allograft to the subscapularis as this may deform the graft, over- constrain the shoulder, and restrict motion.

Discussion

Reconstruction of the superior capsule has been shown to restore the normal restraint to superior translation of the humeral head and reestablish a stable fulcrum at the glenohumeral joint.5 It should be mentioned that we do not perform the SCR in patients with advanced glenohumeral arthritis. The short-term results of this novel procedure have been encouraging, including our own series of patients, in which most patients have had a significant reduction in pain, improvement in function, and very few complications (P. J. Denard, MD, S. S. Burkhart, MD, P. C. Brady, MD, J. Tokish, MD, C. R. Adams, MD, unpublished data, May 2016).

The early success of this procedure suggests that a robust superior capsule is necessary, in addition to functional muscle-tendon units, to restore the stable fulcrum and force couples that are necessary for normal shoulder function. Perhaps we have not paid enough attention to the integrity of the superior capsule in the past. In cases of revision cuff repair, we pay special attention to the quality of the capsular layer deep to the cuff tendon. If the capsule is poor quality, we sometimes reconstruct the capsule with a dermal allograft (SCR) and then do a rotator cuff repair (partial or complete) over the top of the SCR to maintain the normal anatomic deep to superficial layering of the capsule and rotator cuff.

We are very conservative with our postoperative rehabilitation program after a SCR. We know that the rate of stiffness with a conservative program after an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, even in the revision setting, is very low.6 Furthermore, both basic science on healing of soft tissue to bone and radiographic analysis of healing after postoperative rotator cuff repairs support a slow rehabilitation program.7,8 A canine model specifically evaluating acellular dermal allografts in the shoulder suggests that these grafts undergo significant remodeling and become weaker before they get stronger.9 We would rather err on the side of healing of the SCR with potentially a slight increase in the rate of shoulder stiffness than to regain early motion at the expense of graft failure. Therefore, we have the patient wear a sling with no shoulder motion for 6 weeks. Passive motion is started at 6 weeks postoperative and strengthening is delayed until 12 to 16 weeks postoperative.

1. Orr SB, Chainani A, Hippensteel KJ, et al. Aligned multilayered electrospun scaffolds for rotator cuff tendon tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2015;24:117-126.

2. Austin L, Black EM, Lombardi NJ, Pepe MD, Lazarus M. Arthroscopic transosseous rotator cuff repair. A prospective study on cost savings, surgical time, and outcomes. Ortho J Sports Med. 2015;3(2 Suppl). doi:10.1177/2325967115S00156.

3. Denard PJ, Lädermann A, Jiwani AZ, Burkhart SS. Functional outcome after arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears in individuals with pseudoparalysis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(9):1214-1219.

4. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459-470.

5. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2248-2255.

6. Huberty DP, Schoolfield JD, Brady PC, Vadala AP, Arrigoni P, Burkhart SS. Incidence and treatment of postoperative stiffness following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):880-890.

7. Sonnabend DH, Howlett CR, Young AA. Histological evaluation of repair of the rotator cuff in a primate model. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(4):586-594.

8. Lee BG, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Effect of two rehabilitation protocols on range of motion and healing rates after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: aggressive versus limited early passive exercises. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(1):34-42.

9. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS Jr, An KN, Steinmann SP. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: an in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.

1. Orr SB, Chainani A, Hippensteel KJ, et al. Aligned multilayered electrospun scaffolds for rotator cuff tendon tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2015;24:117-126.

2. Austin L, Black EM, Lombardi NJ, Pepe MD, Lazarus M. Arthroscopic transosseous rotator cuff repair. A prospective study on cost savings, surgical time, and outcomes. Ortho J Sports Med. 2015;3(2 Suppl). doi:10.1177/2325967115S00156.

3. Denard PJ, Lädermann A, Jiwani AZ, Burkhart SS. Functional outcome after arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears in individuals with pseudoparalysis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(9):1214-1219.

4. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459-470.

5. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2248-2255.

6. Huberty DP, Schoolfield JD, Brady PC, Vadala AP, Arrigoni P, Burkhart SS. Incidence and treatment of postoperative stiffness following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):880-890.

7. Sonnabend DH, Howlett CR, Young AA. Histological evaluation of repair of the rotator cuff in a primate model. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(4):586-594.

8. Lee BG, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Effect of two rehabilitation protocols on range of motion and healing rates after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: aggressive versus limited early passive exercises. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(1):34-42.

9. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS Jr, An KN, Steinmann SP. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: an in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.