User login

The Integration of Extended Reality in Arthroplasty: Reviewing Technological Progress and Clinical Benefits

The Integration of Extended Reality in Arthroplasty: Reviewing Technological Progress and Clinical Benefits

The introduction of extended reality (XR) to the operating room (OR) has proved promising for enhancing surgical precision and improving patient outcomes. In the field of orthopedic surgery, precise alignment of implants is integral to maintaining functional range of motion and preventing impingement of adjacent neurovascular structures. XR systems have shown promise in arthroplasty including by improving precision and streamlining surgery by allowing surgeons to create 3D preoperative plans that are accessible intraoperatively. This article explores the current applications of XR in arthroplasty, highlights recent advancements and benefits, and describes limitations in comparison to traditional techniques.

Methods

A literature search identified studies involving the use of XR in arthroplasty and current US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved XR systems. Multiple electronic databases were used, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and IEEE Xplore. Search terms included: extended reality, augmented reality, virtual reality, arthroplasty, joint replacement, total knee arthroplasty, total shoulder arthroplasty, and total hip arthroplasty. The study design, intervention details, outcomes, and comparisons with traditional surgical techniques were thematically analyzed, with identification of common ideas associated with XR use in arthroplasty. This narrative report highlights the integration of XR in arthroplasty.

Extended Reality Fundamentals

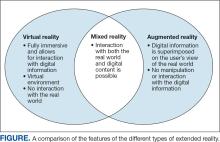

XR encompasses augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), and mixed reality (MR). AR involves superimposing digitally rendered information and images onto the surgeon’s view of the real world, typically through the use of a headset and smart glasses.1 AR allows the surgeon to move and interact freely within the OR, removing the need for additional screens or devices to display patient information or imaging. VR is a fully immersive simulation using a headset that obstructs the view of the real world but allows the user to move freely within this virtual setting, often with audio or other sensory stimuli. MR combines AR and VR to create a digital model that allows for real-world interaction, with the advantage of adapting information and models in real time.2 Whereas in AR the surgeon can view the data projected from the headset, MR provides the ability to interact with and manipulate the digital content (Figure). Both AR and MR have been adapted for use in the OR, while VR has been adapted for use in surgical planning and training.

Extended Reality Use in Orthopedics

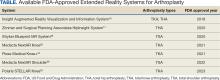

The HipNav system was introduced in 1995 to create preoperative plans that assist surgeons in accurately implanting the acetabular cup during total hip arthroplasty (THA).3 Although not commercially successful, this system spurred surgeons to experiment with XR to improve the accuracy and alignment of orthopedic implants. Systems capable of displaying the desired intraoperative implant placement have flourished, with applications in fracture reduction, arthroplasty, solid tumor resection, and hardware placement.4-7 Accurate alignment has been linked to improvements in patient outcomes.8-10 XR has great potential within the field of arthroplasty, with multiple new systems approved by the FDA and currently available in the US (Table).

Hip Arthroplasty

Orientation of the acetabular cup is a technically challenging part of THA. Accuracy in the anteversion and inclination angles of the acetabular cup is required to maintain implant stability, preserve functional range of motion (ROM), and prevent precocious wear.11,12 Despite preoperative planning, surgeons often overestimate the inclination angle and underestimate anteversion.13 Improper implantation of the acetabular cup can lead to joint instability caused by aseptic loosening, increasing the risk of dislocation and the need for revision surgery.14,15 Dislocations typically present to the emergency department, but primary care practitioners may encounter patients with pain or diminished sensation due to impingement or instability.16

The introduction of XR into the OR has provided the opportunity for real-time navigation and adjustment of the acetabular cup to maximize anteversion and inclination angles. Currently, 2 FDA-approved systems are available for THA: the Zimmer and Surgical Planning Associates HipInsight system, and the Insight Augmented Reality Visualization and Information System (ARVIS). The HipInsight system consists of a hologram projection using the Microsoft HoloLens2 device and optimizes preoperative planning, producing accuracy of anteversion and inclination angles within 3°.17 ARVIS employs existing surgical helmets and 2 mounted tracking cameras to provide navigation intraoperatively. ARVIS has also been approved for use in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty.18

HipInsight has shown utility in increasing the accuracy of acetabular cup placement along with the use of biplanar radiographic scans.19 However, there are no studies validating the efficacy of ARVIS and HipInsight and assessing long-term disease-oriented or patient-oriented outcomes.

Knee Arthroplasty

In the setting of TKA, XR is most effective in ensuring accurate resection of the tibial and femoral components. Achieving the planned femoral coronal, axial, and sagittal angles allows the prosthesis to be on the femoral axis of rotation, improving functional outcomes. XR systems for TKA have been shown to increase the accuracy of distal femoral resection with a limited increase in surgery duration.20,21 For TKA in particular, patients are often less satisfied with the result than surgeons expect.22 Accurate alignment can improve patient satisfaction and reduce return-to-clinic rates for postoperative pain management, a factor that primary care practitioners should consider when recommending a patient for TKA.23

Along with ARVIS, 3 additional XR systems are FDA-approved for use in TKA. The Pixee Medical Knee+ system uses smart glasses and trackers to aid in the positioning of instruments for improved accuracy while allowing real-time navigation.24 The Medacta NextAR Knee’s single-use tracking system allows for intraoperative navigation with the use of AR glasses.25 The Polaris STELLAR Knee uses MR and avoids the need for preoperative imaging by capturing real-time anatomic data.26

The Pixee Medical Knee+ system was commercially available in Europe for several years prior to FDA approval, so more research exists on its efficacy. One study found that the Pixee Medical Knee+ system initially demonstrated an inferior clinical outcome, attributed to the learning curve associated with using the system.27 However, more recent studies have shown its utility in improving alignment, regardless of implant specifications.28,29 The Medacta NextAR Knee system has been shown to improve accuracy of tibial rotation and soft tissue balance and even increase OR efficiency.30,31 The Polaris STELLAR Knee system received FDA approval in 2023; no published research exists on its accuracy and outcomes.26

Shoulder Arthroplasty

Minimally invasive techniques are favored in total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) due to the vitality of maintaining the surrounding soft tissue to maximize preservation of motility and strength.32 However, this complicates the procedure by decreasing the ability to effectively access and visualize key structures of the shoulder. Accordingly, issues with implant positioning and alignment are more common with TSA than other joint arthroplasties, making XR particularly promising.33 Some studies report that up to 67% of patients experience glenohumeral instability, which can clinically present as weakness, decreased range of motion, and persistent shoulder pain.34,35 The use of preoperative computed tomography to improve understanding of glenoid anatomy and glenohumeral subluxation is becoming increasingly common, and it can be combined with XR to improve accuracy.36,37

Two FDA-approved systems are available. The Stryker Blueprint MR system is used for intraoperative guidance and integration for patient imaging used for preoperative planning. The Medacta NextAR Shoulder system is a parallel of the company’s TKA system. The Stryker Blueprint MR system combines the Microsoft HoloLens 2 headset to display preoperative plans with a secondary display for coordination with the rest of the surgical team.38 Similar to the Medacta NextAR Knee, the Medacta NextAR Shoulder system uses the same single-use tracking system and AR glasses for intraoperative guidance.39

Data on the long-term outcomes of using these systems are still limited, but the Stryker Blueprint MR system has not been shown to accurately predict postoperative ROM.40 Cadaveric studies have demonstrated that the Medacta NextAR Shoulder system can provide accurate inclination, retroversion, entry point, depth, and rotation values based on the preoperative planned values.41,42 However, this accuracy has yet to be confirmed in vivo, and the impact of using XR in TSA on long-term outcomes is still unknown.

Challenges and Limitations

Though XR has proven to be promising in arthroplasty, several limitations regarding widespread implementation exist. In particular, there is a steep learning curve associated with the use of XR systems, which can cause increased operative time and even initial inferior outcomes, as demonstrated with the Pixee Medical Knee+ system. The need for extensive practice and training prior to use could delay widespread adoption and may cause discrepancies in surgical outcomes. Unfamiliarity with the system and technological difficulties that may require troubleshooting can also increase operative time, particularly for surgeons new to using the XR system. Though intraoperative navigation is expected to improve accuracy of implant alignment, its added complexity may also result in longer surgeries.

In addition to the steep learning curve and increased operative time, there is a high upfront cost associated with XR systems. Exact costs of XR systems are not typically disclosed, but available estimates suggest an average sales price of about $1000 per case. Given the proprietary nature of these technologies, publicly available cost data are limited, making it challenging to fully assess the financial burden on health care institutions. Though some systems, such as ARVIS, can be integrated with existing surgical helmets, many require the purchase of AR glasses and secondary displays. This can cause further variation in the total expense for each system. In low-resource settings, this represents a significant challenge to widespread implementation. To justify this cost, additional research on long-term patient outcomes is needed to ensure the benefits of XR systems outweigh the cost.

Although early studies on XR systems in arthroplasty have shown improvements in precision and short-term outcomes, long-term data regarding effectiveness remains. Even systems such as ARVIS and HipInsight have limited long-term follow-up, making it difficult to assess whether the improved accuracy with these XR systems translates into improved patient outcomes compared with traditional arthroplasty.

CONCLUSIONS

XR technologies have shown significant potential in enhancing precision and patient outcomes. Through the integration of XR in the OR, surgeons can visualize preoperative plans and even make intraoperative changes, with the benefit of improving implant alignment.

There are some disadvantages to its use, however, including high cost and increased operative time. Despite this, the integration of XR into surgical practice can deliver more precise implant alignment and address other challenges faced with conventional techniques. As these technologies evolve and studies on long-term outcomes validate their utility, XR has the potential to transform the field of arthroplasty.

Azuma RT. A survey of augmented reality. Presence-Teleop Virt. 1997;6:355-385. doi:10.1162/pres.1997.6.4.355

Speicher M, Hall BD, Nebeling M. What is Mixed Reality? In: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery; 2019:1-15. doi:10.1145/3290605.3300767

Digioia AM, Jaramaz B, Nikou C, et al. Surgical navigation for total hip replacement with the use of hipnav. Oper Tech Orthop. 2000;10:3-8. doi:10.1016/S1048-6666(00)80036-1

Ogawa H, Hasegawa S, Tsukada S, et al. A pilot study of augmented reality technology applied to the acetabular cup placement during total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1833-1837. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.01.067

Shen F, Chen B, Guo Q, et al. Augmented reality patient-specific reconstruction plate design for pelvic and acetabular fracture surgery. Int J CARS. 2013;8:169-179. doi:10.1007/s11548-012-0775-5

Cho HS, Park YK, Gupta S, et al. Augmented reality in bone tumour resection: an experimental study. Bone Joint Res. 2017;6:137-143. doi:10.1302/2046-3758.63.bjr-2016-0289.r1

Wu X, Liu R, Yu J, et al. Mixed reality technology launches in orthopedic surgery for comprehensive preoperative management of complicated cervical fractures. Surg Innov. 2018;25:421-422. doi:10.1177/1553350618761758

Dossett HG, Arthur JR, Makovicka JL, et al. A randomized controlled trial of kinematically and mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasties: long-term follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:S209-S214. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.03.065

Kazarian GS, Haddad FS, Donaldson MJ, et al. Implant malalignment may be a risk factor for poor patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) following total knee arthroplasty (TKA). J Arthroplasty. 2022;37:S129-S133. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2022.02.087

Peng Y, Arauz P, An S, et al. Does component alignment affect patient reported outcomes following bicruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty? An in vivo three-dimensional analysis. J Knee Surg. 2020;33:798-803. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1688500

D’Lima DD, Urquhart AG, Buehler KO, et al. The effect of the orientation of the acetabular and femoral components on the range of motion of the hip at different head-neck ratios. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:315-321. doi:10.2106/00004623-200003000-00003

Yamaguchi M, Akisue T, Bauer TW, et al. The spatial location of impingement in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:305-313. doi:10.1016/s0883-5403(00)90601-6

Grammatopoulos G, Alvand A, Monk AP, et al. Surgeons’ accuracy in achieving their desired acetabular component orientation. J Bone Joint Surg. 2016;98:e72. doi:10.2106/JBJS.15.01080

Kennedy JG, Rogers WB, Soffe KE, et al. Effect of acetabular component orientation on recurrent dislocation, pelvic osteolysis, polyethylene wear, and component migration. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:530-534. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(98)90052-3

Del Schutte H, Lipman AJ, Bannar SM, et al. Effects of acetabular abduction on cup wear rates in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:621-626. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(98)80003-X

Aresti N, Kassam J, Bartlett D, et al. Primary care management of postoperative shoulder, hip, and knee arthroplasty. BMJ. 2017;359:j4431. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4431

HipInsightTM System. Zimmer Biomet. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.zimmerbiomet.com/en/products-and-solutions/zb-edge/mixed-reality-portfolio/hipinsight-system.html

ARVIS. Insight Medical Systems. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.insightmedsys.com/arvis

Sun DC, Murphy WS, Amundson AJ, et al. Validation of a novel method of measuring cup orientation using biplanar simultaneous radiographic images. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:S252-S256. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.04.011

Tsukada S, Ogawa H, Nishino M, et al. Augmented reality-assisted femoral bone resection in total knee arthroplasty. JBJS Open Access. 2021;6:e21.00001. doi:10.2106/JBJS.OA.21.00001

Castellarin G, Bori E, Barbieux E, et al. Is total knee arthroplasty surgical performance enhanced using augmented reality? A single-center study on 76 consecutive patients. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39:332-335. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.08.013

Choi YJ, Ra HJ. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2016;28:1. doi:10.5792/ksrr.2016.28.1.1

Hazratwala K, Gouk C, Wilkinson MPR, et al. Navigated functional alignment total knee arthroplasty achieves reliable, reproducible and accurate results with high patient satisfaction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31:3861-3870. doi:10.1007/s00167-023-07327-w

Knee+. Pixee Medical. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.pixee-medical.com/en/products/knee-nexsight/

KNEE | NEXTAR. Nextar. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://nextar.medacta.com/knee

POLARIS AR receives clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for STELLAR Knee. News release. PRNewswire. November 3, 2023. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/polarisar-receives-clearance-from-the-us-food-and-drug-administration-for-stellar-knee-301976747.html

van Overschelde P, Vansintjan P, Byn P, Lapierre C, van Lysebettens W. Does augmented reality improve clinical outcome in TKA? A prospective observational report. In: The 20th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Computer Assisted Orthopaedic Surgery. 2022:170-174.

Sakellariou E, Alevrogiannis P, Alevrogianni F, et al. Single-center experience with Knee+TM augmented reality navigation system in primary total knee arthroplasty. World J Orthop. 2024;15:247-256. doi:10.5312/wjo.v15.i3.247

León-Muñoz VJ, Moya-Angeler J, López-López M, et al. Integration of square fiducial markers in patient-specific instrumentation and their applicability in knee surgery. J Pers Med. 2023;13:727. doi:10.3390/jpm13050727

Fucentese SF, Koch PP. A novel augmented reality-based surgical guidance system for total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021;141:2227-2233. doi:10.1007/s00402-021-04204-4

Sabatini L, Ascani D, Vezza D, et al. Novel surgical technique for total knee arthroplasty integrating kinematic alignment and real-time elongation of the ligaments using the NextAR system. J Pers Med. 2024;14:794. doi:10.3390/jpm14080794

Daher M, Ghanimeh J, Otayek J, et al. Augmented reality and shoulder replacement: a state-of-the-art review article. JSES Rev Rep Tech. 2023;3:274-278. doi:10.1016/j.xrrt.2023.01.008

Atmani H, Merienne F, Fofi D, et al. Computer aided surgery system for shoulder prosthesis placement. Comput Aided Surg. 2007;12:60-70. doi:10.3109/10929080701210832

Eichinger JK, Galvin JW. Management of complications after total shoulder arthroplasty. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;8:83-91. doi:10.1007/s12178-014-9251-x

Bonnevialle N, Melis B, Neyton L, et al. Aseptic glenoid loosening or failure in total shoulder arthroplasty: revision with glenoid reimplantation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:745-751. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.08.009

Erickson BJ, Chalmers PN, Denard P, et al. Does commercially available shoulder arthroplasty preoperative planning software agree with surgeon measurements of version, inclination, and subluxation? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30:413-420. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2020.05.027

Werner BS, Hudek R, Burkhart KJ, et al. The influence of three-dimensional planning on decision-making in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:1477-1483. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.01.006

Blueprint. Stryker. Updated August 2025. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.stryker.com/us/en/trauma-and-extremities/products/blueprint.html

NextAR Shoulder. Medacta. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://nextar.medacta.com/shoulder

Baumgarten KM. Accuracy of Blueprint software in predicting range of motion 1 year after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:1088-1094. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2022.12.009

Rojas JT, Jost B, Zipeto C, et al. Glenoid component placement in reverse shoulder arthroplasty assisted with augmented reality through a head-mounted display leads to low deviation between planned and postoperative parameters. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:e587-e596. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2023.05.002

Dey Hazra RO, Paksoy A, Imiolczyk JP, et al. Augmented reality–assisted intraoperative navigation increases precision of glenoid inclination in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2025;34(2):577-583. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2024.05.039

The introduction of extended reality (XR) to the operating room (OR) has proved promising for enhancing surgical precision and improving patient outcomes. In the field of orthopedic surgery, precise alignment of implants is integral to maintaining functional range of motion and preventing impingement of adjacent neurovascular structures. XR systems have shown promise in arthroplasty including by improving precision and streamlining surgery by allowing surgeons to create 3D preoperative plans that are accessible intraoperatively. This article explores the current applications of XR in arthroplasty, highlights recent advancements and benefits, and describes limitations in comparison to traditional techniques.

Methods

A literature search identified studies involving the use of XR in arthroplasty and current US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved XR systems. Multiple electronic databases were used, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and IEEE Xplore. Search terms included: extended reality, augmented reality, virtual reality, arthroplasty, joint replacement, total knee arthroplasty, total shoulder arthroplasty, and total hip arthroplasty. The study design, intervention details, outcomes, and comparisons with traditional surgical techniques were thematically analyzed, with identification of common ideas associated with XR use in arthroplasty. This narrative report highlights the integration of XR in arthroplasty.

Extended Reality Fundamentals

XR encompasses augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), and mixed reality (MR). AR involves superimposing digitally rendered information and images onto the surgeon’s view of the real world, typically through the use of a headset and smart glasses.1 AR allows the surgeon to move and interact freely within the OR, removing the need for additional screens or devices to display patient information or imaging. VR is a fully immersive simulation using a headset that obstructs the view of the real world but allows the user to move freely within this virtual setting, often with audio or other sensory stimuli. MR combines AR and VR to create a digital model that allows for real-world interaction, with the advantage of adapting information and models in real time.2 Whereas in AR the surgeon can view the data projected from the headset, MR provides the ability to interact with and manipulate the digital content (Figure). Both AR and MR have been adapted for use in the OR, while VR has been adapted for use in surgical planning and training.

Extended Reality Use in Orthopedics

The HipNav system was introduced in 1995 to create preoperative plans that assist surgeons in accurately implanting the acetabular cup during total hip arthroplasty (THA).3 Although not commercially successful, this system spurred surgeons to experiment with XR to improve the accuracy and alignment of orthopedic implants. Systems capable of displaying the desired intraoperative implant placement have flourished, with applications in fracture reduction, arthroplasty, solid tumor resection, and hardware placement.4-7 Accurate alignment has been linked to improvements in patient outcomes.8-10 XR has great potential within the field of arthroplasty, with multiple new systems approved by the FDA and currently available in the US (Table).

Hip Arthroplasty

Orientation of the acetabular cup is a technically challenging part of THA. Accuracy in the anteversion and inclination angles of the acetabular cup is required to maintain implant stability, preserve functional range of motion (ROM), and prevent precocious wear.11,12 Despite preoperative planning, surgeons often overestimate the inclination angle and underestimate anteversion.13 Improper implantation of the acetabular cup can lead to joint instability caused by aseptic loosening, increasing the risk of dislocation and the need for revision surgery.14,15 Dislocations typically present to the emergency department, but primary care practitioners may encounter patients with pain or diminished sensation due to impingement or instability.16

The introduction of XR into the OR has provided the opportunity for real-time navigation and adjustment of the acetabular cup to maximize anteversion and inclination angles. Currently, 2 FDA-approved systems are available for THA: the Zimmer and Surgical Planning Associates HipInsight system, and the Insight Augmented Reality Visualization and Information System (ARVIS). The HipInsight system consists of a hologram projection using the Microsoft HoloLens2 device and optimizes preoperative planning, producing accuracy of anteversion and inclination angles within 3°.17 ARVIS employs existing surgical helmets and 2 mounted tracking cameras to provide navigation intraoperatively. ARVIS has also been approved for use in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty.18

HipInsight has shown utility in increasing the accuracy of acetabular cup placement along with the use of biplanar radiographic scans.19 However, there are no studies validating the efficacy of ARVIS and HipInsight and assessing long-term disease-oriented or patient-oriented outcomes.

Knee Arthroplasty

In the setting of TKA, XR is most effective in ensuring accurate resection of the tibial and femoral components. Achieving the planned femoral coronal, axial, and sagittal angles allows the prosthesis to be on the femoral axis of rotation, improving functional outcomes. XR systems for TKA have been shown to increase the accuracy of distal femoral resection with a limited increase in surgery duration.20,21 For TKA in particular, patients are often less satisfied with the result than surgeons expect.22 Accurate alignment can improve patient satisfaction and reduce return-to-clinic rates for postoperative pain management, a factor that primary care practitioners should consider when recommending a patient for TKA.23

Along with ARVIS, 3 additional XR systems are FDA-approved for use in TKA. The Pixee Medical Knee+ system uses smart glasses and trackers to aid in the positioning of instruments for improved accuracy while allowing real-time navigation.24 The Medacta NextAR Knee’s single-use tracking system allows for intraoperative navigation with the use of AR glasses.25 The Polaris STELLAR Knee uses MR and avoids the need for preoperative imaging by capturing real-time anatomic data.26

The Pixee Medical Knee+ system was commercially available in Europe for several years prior to FDA approval, so more research exists on its efficacy. One study found that the Pixee Medical Knee+ system initially demonstrated an inferior clinical outcome, attributed to the learning curve associated with using the system.27 However, more recent studies have shown its utility in improving alignment, regardless of implant specifications.28,29 The Medacta NextAR Knee system has been shown to improve accuracy of tibial rotation and soft tissue balance and even increase OR efficiency.30,31 The Polaris STELLAR Knee system received FDA approval in 2023; no published research exists on its accuracy and outcomes.26

Shoulder Arthroplasty

Minimally invasive techniques are favored in total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) due to the vitality of maintaining the surrounding soft tissue to maximize preservation of motility and strength.32 However, this complicates the procedure by decreasing the ability to effectively access and visualize key structures of the shoulder. Accordingly, issues with implant positioning and alignment are more common with TSA than other joint arthroplasties, making XR particularly promising.33 Some studies report that up to 67% of patients experience glenohumeral instability, which can clinically present as weakness, decreased range of motion, and persistent shoulder pain.34,35 The use of preoperative computed tomography to improve understanding of glenoid anatomy and glenohumeral subluxation is becoming increasingly common, and it can be combined with XR to improve accuracy.36,37

Two FDA-approved systems are available. The Stryker Blueprint MR system is used for intraoperative guidance and integration for patient imaging used for preoperative planning. The Medacta NextAR Shoulder system is a parallel of the company’s TKA system. The Stryker Blueprint MR system combines the Microsoft HoloLens 2 headset to display preoperative plans with a secondary display for coordination with the rest of the surgical team.38 Similar to the Medacta NextAR Knee, the Medacta NextAR Shoulder system uses the same single-use tracking system and AR glasses for intraoperative guidance.39

Data on the long-term outcomes of using these systems are still limited, but the Stryker Blueprint MR system has not been shown to accurately predict postoperative ROM.40 Cadaveric studies have demonstrated that the Medacta NextAR Shoulder system can provide accurate inclination, retroversion, entry point, depth, and rotation values based on the preoperative planned values.41,42 However, this accuracy has yet to be confirmed in vivo, and the impact of using XR in TSA on long-term outcomes is still unknown.

Challenges and Limitations

Though XR has proven to be promising in arthroplasty, several limitations regarding widespread implementation exist. In particular, there is a steep learning curve associated with the use of XR systems, which can cause increased operative time and even initial inferior outcomes, as demonstrated with the Pixee Medical Knee+ system. The need for extensive practice and training prior to use could delay widespread adoption and may cause discrepancies in surgical outcomes. Unfamiliarity with the system and technological difficulties that may require troubleshooting can also increase operative time, particularly for surgeons new to using the XR system. Though intraoperative navigation is expected to improve accuracy of implant alignment, its added complexity may also result in longer surgeries.

In addition to the steep learning curve and increased operative time, there is a high upfront cost associated with XR systems. Exact costs of XR systems are not typically disclosed, but available estimates suggest an average sales price of about $1000 per case. Given the proprietary nature of these technologies, publicly available cost data are limited, making it challenging to fully assess the financial burden on health care institutions. Though some systems, such as ARVIS, can be integrated with existing surgical helmets, many require the purchase of AR glasses and secondary displays. This can cause further variation in the total expense for each system. In low-resource settings, this represents a significant challenge to widespread implementation. To justify this cost, additional research on long-term patient outcomes is needed to ensure the benefits of XR systems outweigh the cost.

Although early studies on XR systems in arthroplasty have shown improvements in precision and short-term outcomes, long-term data regarding effectiveness remains. Even systems such as ARVIS and HipInsight have limited long-term follow-up, making it difficult to assess whether the improved accuracy with these XR systems translates into improved patient outcomes compared with traditional arthroplasty.

CONCLUSIONS

XR technologies have shown significant potential in enhancing precision and patient outcomes. Through the integration of XR in the OR, surgeons can visualize preoperative plans and even make intraoperative changes, with the benefit of improving implant alignment.

There are some disadvantages to its use, however, including high cost and increased operative time. Despite this, the integration of XR into surgical practice can deliver more precise implant alignment and address other challenges faced with conventional techniques. As these technologies evolve and studies on long-term outcomes validate their utility, XR has the potential to transform the field of arthroplasty.

The introduction of extended reality (XR) to the operating room (OR) has proved promising for enhancing surgical precision and improving patient outcomes. In the field of orthopedic surgery, precise alignment of implants is integral to maintaining functional range of motion and preventing impingement of adjacent neurovascular structures. XR systems have shown promise in arthroplasty including by improving precision and streamlining surgery by allowing surgeons to create 3D preoperative plans that are accessible intraoperatively. This article explores the current applications of XR in arthroplasty, highlights recent advancements and benefits, and describes limitations in comparison to traditional techniques.

Methods

A literature search identified studies involving the use of XR in arthroplasty and current US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved XR systems. Multiple electronic databases were used, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and IEEE Xplore. Search terms included: extended reality, augmented reality, virtual reality, arthroplasty, joint replacement, total knee arthroplasty, total shoulder arthroplasty, and total hip arthroplasty. The study design, intervention details, outcomes, and comparisons with traditional surgical techniques were thematically analyzed, with identification of common ideas associated with XR use in arthroplasty. This narrative report highlights the integration of XR in arthroplasty.

Extended Reality Fundamentals

XR encompasses augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), and mixed reality (MR). AR involves superimposing digitally rendered information and images onto the surgeon’s view of the real world, typically through the use of a headset and smart glasses.1 AR allows the surgeon to move and interact freely within the OR, removing the need for additional screens or devices to display patient information or imaging. VR is a fully immersive simulation using a headset that obstructs the view of the real world but allows the user to move freely within this virtual setting, often with audio or other sensory stimuli. MR combines AR and VR to create a digital model that allows for real-world interaction, with the advantage of adapting information and models in real time.2 Whereas in AR the surgeon can view the data projected from the headset, MR provides the ability to interact with and manipulate the digital content (Figure). Both AR and MR have been adapted for use in the OR, while VR has been adapted for use in surgical planning and training.

Extended Reality Use in Orthopedics

The HipNav system was introduced in 1995 to create preoperative plans that assist surgeons in accurately implanting the acetabular cup during total hip arthroplasty (THA).3 Although not commercially successful, this system spurred surgeons to experiment with XR to improve the accuracy and alignment of orthopedic implants. Systems capable of displaying the desired intraoperative implant placement have flourished, with applications in fracture reduction, arthroplasty, solid tumor resection, and hardware placement.4-7 Accurate alignment has been linked to improvements in patient outcomes.8-10 XR has great potential within the field of arthroplasty, with multiple new systems approved by the FDA and currently available in the US (Table).

Hip Arthroplasty

Orientation of the acetabular cup is a technically challenging part of THA. Accuracy in the anteversion and inclination angles of the acetabular cup is required to maintain implant stability, preserve functional range of motion (ROM), and prevent precocious wear.11,12 Despite preoperative planning, surgeons often overestimate the inclination angle and underestimate anteversion.13 Improper implantation of the acetabular cup can lead to joint instability caused by aseptic loosening, increasing the risk of dislocation and the need for revision surgery.14,15 Dislocations typically present to the emergency department, but primary care practitioners may encounter patients with pain or diminished sensation due to impingement or instability.16

The introduction of XR into the OR has provided the opportunity for real-time navigation and adjustment of the acetabular cup to maximize anteversion and inclination angles. Currently, 2 FDA-approved systems are available for THA: the Zimmer and Surgical Planning Associates HipInsight system, and the Insight Augmented Reality Visualization and Information System (ARVIS). The HipInsight system consists of a hologram projection using the Microsoft HoloLens2 device and optimizes preoperative planning, producing accuracy of anteversion and inclination angles within 3°.17 ARVIS employs existing surgical helmets and 2 mounted tracking cameras to provide navigation intraoperatively. ARVIS has also been approved for use in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty.18

HipInsight has shown utility in increasing the accuracy of acetabular cup placement along with the use of biplanar radiographic scans.19 However, there are no studies validating the efficacy of ARVIS and HipInsight and assessing long-term disease-oriented or patient-oriented outcomes.

Knee Arthroplasty

In the setting of TKA, XR is most effective in ensuring accurate resection of the tibial and femoral components. Achieving the planned femoral coronal, axial, and sagittal angles allows the prosthesis to be on the femoral axis of rotation, improving functional outcomes. XR systems for TKA have been shown to increase the accuracy of distal femoral resection with a limited increase in surgery duration.20,21 For TKA in particular, patients are often less satisfied with the result than surgeons expect.22 Accurate alignment can improve patient satisfaction and reduce return-to-clinic rates for postoperative pain management, a factor that primary care practitioners should consider when recommending a patient for TKA.23

Along with ARVIS, 3 additional XR systems are FDA-approved for use in TKA. The Pixee Medical Knee+ system uses smart glasses and trackers to aid in the positioning of instruments for improved accuracy while allowing real-time navigation.24 The Medacta NextAR Knee’s single-use tracking system allows for intraoperative navigation with the use of AR glasses.25 The Polaris STELLAR Knee uses MR and avoids the need for preoperative imaging by capturing real-time anatomic data.26

The Pixee Medical Knee+ system was commercially available in Europe for several years prior to FDA approval, so more research exists on its efficacy. One study found that the Pixee Medical Knee+ system initially demonstrated an inferior clinical outcome, attributed to the learning curve associated with using the system.27 However, more recent studies have shown its utility in improving alignment, regardless of implant specifications.28,29 The Medacta NextAR Knee system has been shown to improve accuracy of tibial rotation and soft tissue balance and even increase OR efficiency.30,31 The Polaris STELLAR Knee system received FDA approval in 2023; no published research exists on its accuracy and outcomes.26

Shoulder Arthroplasty

Minimally invasive techniques are favored in total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) due to the vitality of maintaining the surrounding soft tissue to maximize preservation of motility and strength.32 However, this complicates the procedure by decreasing the ability to effectively access and visualize key structures of the shoulder. Accordingly, issues with implant positioning and alignment are more common with TSA than other joint arthroplasties, making XR particularly promising.33 Some studies report that up to 67% of patients experience glenohumeral instability, which can clinically present as weakness, decreased range of motion, and persistent shoulder pain.34,35 The use of preoperative computed tomography to improve understanding of glenoid anatomy and glenohumeral subluxation is becoming increasingly common, and it can be combined with XR to improve accuracy.36,37

Two FDA-approved systems are available. The Stryker Blueprint MR system is used for intraoperative guidance and integration for patient imaging used for preoperative planning. The Medacta NextAR Shoulder system is a parallel of the company’s TKA system. The Stryker Blueprint MR system combines the Microsoft HoloLens 2 headset to display preoperative plans with a secondary display for coordination with the rest of the surgical team.38 Similar to the Medacta NextAR Knee, the Medacta NextAR Shoulder system uses the same single-use tracking system and AR glasses for intraoperative guidance.39

Data on the long-term outcomes of using these systems are still limited, but the Stryker Blueprint MR system has not been shown to accurately predict postoperative ROM.40 Cadaveric studies have demonstrated that the Medacta NextAR Shoulder system can provide accurate inclination, retroversion, entry point, depth, and rotation values based on the preoperative planned values.41,42 However, this accuracy has yet to be confirmed in vivo, and the impact of using XR in TSA on long-term outcomes is still unknown.

Challenges and Limitations

Though XR has proven to be promising in arthroplasty, several limitations regarding widespread implementation exist. In particular, there is a steep learning curve associated with the use of XR systems, which can cause increased operative time and even initial inferior outcomes, as demonstrated with the Pixee Medical Knee+ system. The need for extensive practice and training prior to use could delay widespread adoption and may cause discrepancies in surgical outcomes. Unfamiliarity with the system and technological difficulties that may require troubleshooting can also increase operative time, particularly for surgeons new to using the XR system. Though intraoperative navigation is expected to improve accuracy of implant alignment, its added complexity may also result in longer surgeries.

In addition to the steep learning curve and increased operative time, there is a high upfront cost associated with XR systems. Exact costs of XR systems are not typically disclosed, but available estimates suggest an average sales price of about $1000 per case. Given the proprietary nature of these technologies, publicly available cost data are limited, making it challenging to fully assess the financial burden on health care institutions. Though some systems, such as ARVIS, can be integrated with existing surgical helmets, many require the purchase of AR glasses and secondary displays. This can cause further variation in the total expense for each system. In low-resource settings, this represents a significant challenge to widespread implementation. To justify this cost, additional research on long-term patient outcomes is needed to ensure the benefits of XR systems outweigh the cost.

Although early studies on XR systems in arthroplasty have shown improvements in precision and short-term outcomes, long-term data regarding effectiveness remains. Even systems such as ARVIS and HipInsight have limited long-term follow-up, making it difficult to assess whether the improved accuracy with these XR systems translates into improved patient outcomes compared with traditional arthroplasty.

CONCLUSIONS

XR technologies have shown significant potential in enhancing precision and patient outcomes. Through the integration of XR in the OR, surgeons can visualize preoperative plans and even make intraoperative changes, with the benefit of improving implant alignment.

There are some disadvantages to its use, however, including high cost and increased operative time. Despite this, the integration of XR into surgical practice can deliver more precise implant alignment and address other challenges faced with conventional techniques. As these technologies evolve and studies on long-term outcomes validate their utility, XR has the potential to transform the field of arthroplasty.

Azuma RT. A survey of augmented reality. Presence-Teleop Virt. 1997;6:355-385. doi:10.1162/pres.1997.6.4.355

Speicher M, Hall BD, Nebeling M. What is Mixed Reality? In: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery; 2019:1-15. doi:10.1145/3290605.3300767

Digioia AM, Jaramaz B, Nikou C, et al. Surgical navigation for total hip replacement with the use of hipnav. Oper Tech Orthop. 2000;10:3-8. doi:10.1016/S1048-6666(00)80036-1

Ogawa H, Hasegawa S, Tsukada S, et al. A pilot study of augmented reality technology applied to the acetabular cup placement during total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1833-1837. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.01.067

Shen F, Chen B, Guo Q, et al. Augmented reality patient-specific reconstruction plate design for pelvic and acetabular fracture surgery. Int J CARS. 2013;8:169-179. doi:10.1007/s11548-012-0775-5

Cho HS, Park YK, Gupta S, et al. Augmented reality in bone tumour resection: an experimental study. Bone Joint Res. 2017;6:137-143. doi:10.1302/2046-3758.63.bjr-2016-0289.r1

Wu X, Liu R, Yu J, et al. Mixed reality technology launches in orthopedic surgery for comprehensive preoperative management of complicated cervical fractures. Surg Innov. 2018;25:421-422. doi:10.1177/1553350618761758

Dossett HG, Arthur JR, Makovicka JL, et al. A randomized controlled trial of kinematically and mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasties: long-term follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:S209-S214. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.03.065

Kazarian GS, Haddad FS, Donaldson MJ, et al. Implant malalignment may be a risk factor for poor patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) following total knee arthroplasty (TKA). J Arthroplasty. 2022;37:S129-S133. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2022.02.087

Peng Y, Arauz P, An S, et al. Does component alignment affect patient reported outcomes following bicruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty? An in vivo three-dimensional analysis. J Knee Surg. 2020;33:798-803. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1688500

D’Lima DD, Urquhart AG, Buehler KO, et al. The effect of the orientation of the acetabular and femoral components on the range of motion of the hip at different head-neck ratios. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:315-321. doi:10.2106/00004623-200003000-00003

Yamaguchi M, Akisue T, Bauer TW, et al. The spatial location of impingement in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:305-313. doi:10.1016/s0883-5403(00)90601-6

Grammatopoulos G, Alvand A, Monk AP, et al. Surgeons’ accuracy in achieving their desired acetabular component orientation. J Bone Joint Surg. 2016;98:e72. doi:10.2106/JBJS.15.01080

Kennedy JG, Rogers WB, Soffe KE, et al. Effect of acetabular component orientation on recurrent dislocation, pelvic osteolysis, polyethylene wear, and component migration. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:530-534. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(98)90052-3

Del Schutte H, Lipman AJ, Bannar SM, et al. Effects of acetabular abduction on cup wear rates in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:621-626. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(98)80003-X

Aresti N, Kassam J, Bartlett D, et al. Primary care management of postoperative shoulder, hip, and knee arthroplasty. BMJ. 2017;359:j4431. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4431

HipInsightTM System. Zimmer Biomet. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.zimmerbiomet.com/en/products-and-solutions/zb-edge/mixed-reality-portfolio/hipinsight-system.html

ARVIS. Insight Medical Systems. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.insightmedsys.com/arvis

Sun DC, Murphy WS, Amundson AJ, et al. Validation of a novel method of measuring cup orientation using biplanar simultaneous radiographic images. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:S252-S256. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.04.011

Tsukada S, Ogawa H, Nishino M, et al. Augmented reality-assisted femoral bone resection in total knee arthroplasty. JBJS Open Access. 2021;6:e21.00001. doi:10.2106/JBJS.OA.21.00001

Castellarin G, Bori E, Barbieux E, et al. Is total knee arthroplasty surgical performance enhanced using augmented reality? A single-center study on 76 consecutive patients. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39:332-335. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.08.013

Choi YJ, Ra HJ. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2016;28:1. doi:10.5792/ksrr.2016.28.1.1

Hazratwala K, Gouk C, Wilkinson MPR, et al. Navigated functional alignment total knee arthroplasty achieves reliable, reproducible and accurate results with high patient satisfaction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31:3861-3870. doi:10.1007/s00167-023-07327-w

Knee+. Pixee Medical. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.pixee-medical.com/en/products/knee-nexsight/

KNEE | NEXTAR. Nextar. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://nextar.medacta.com/knee

POLARIS AR receives clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for STELLAR Knee. News release. PRNewswire. November 3, 2023. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/polarisar-receives-clearance-from-the-us-food-and-drug-administration-for-stellar-knee-301976747.html

van Overschelde P, Vansintjan P, Byn P, Lapierre C, van Lysebettens W. Does augmented reality improve clinical outcome in TKA? A prospective observational report. In: The 20th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Computer Assisted Orthopaedic Surgery. 2022:170-174.

Sakellariou E, Alevrogiannis P, Alevrogianni F, et al. Single-center experience with Knee+TM augmented reality navigation system in primary total knee arthroplasty. World J Orthop. 2024;15:247-256. doi:10.5312/wjo.v15.i3.247

León-Muñoz VJ, Moya-Angeler J, López-López M, et al. Integration of square fiducial markers in patient-specific instrumentation and their applicability in knee surgery. J Pers Med. 2023;13:727. doi:10.3390/jpm13050727

Fucentese SF, Koch PP. A novel augmented reality-based surgical guidance system for total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021;141:2227-2233. doi:10.1007/s00402-021-04204-4

Sabatini L, Ascani D, Vezza D, et al. Novel surgical technique for total knee arthroplasty integrating kinematic alignment and real-time elongation of the ligaments using the NextAR system. J Pers Med. 2024;14:794. doi:10.3390/jpm14080794

Daher M, Ghanimeh J, Otayek J, et al. Augmented reality and shoulder replacement: a state-of-the-art review article. JSES Rev Rep Tech. 2023;3:274-278. doi:10.1016/j.xrrt.2023.01.008

Atmani H, Merienne F, Fofi D, et al. Computer aided surgery system for shoulder prosthesis placement. Comput Aided Surg. 2007;12:60-70. doi:10.3109/10929080701210832

Eichinger JK, Galvin JW. Management of complications after total shoulder arthroplasty. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;8:83-91. doi:10.1007/s12178-014-9251-x

Bonnevialle N, Melis B, Neyton L, et al. Aseptic glenoid loosening or failure in total shoulder arthroplasty: revision with glenoid reimplantation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:745-751. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.08.009

Erickson BJ, Chalmers PN, Denard P, et al. Does commercially available shoulder arthroplasty preoperative planning software agree with surgeon measurements of version, inclination, and subluxation? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30:413-420. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2020.05.027

Werner BS, Hudek R, Burkhart KJ, et al. The influence of three-dimensional planning on decision-making in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:1477-1483. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.01.006

Blueprint. Stryker. Updated August 2025. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.stryker.com/us/en/trauma-and-extremities/products/blueprint.html

NextAR Shoulder. Medacta. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://nextar.medacta.com/shoulder

Baumgarten KM. Accuracy of Blueprint software in predicting range of motion 1 year after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:1088-1094. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2022.12.009

Rojas JT, Jost B, Zipeto C, et al. Glenoid component placement in reverse shoulder arthroplasty assisted with augmented reality through a head-mounted display leads to low deviation between planned and postoperative parameters. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:e587-e596. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2023.05.002

Dey Hazra RO, Paksoy A, Imiolczyk JP, et al. Augmented reality–assisted intraoperative navigation increases precision of glenoid inclination in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2025;34(2):577-583. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2024.05.039

Azuma RT. A survey of augmented reality. Presence-Teleop Virt. 1997;6:355-385. doi:10.1162/pres.1997.6.4.355

Speicher M, Hall BD, Nebeling M. What is Mixed Reality? In: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery; 2019:1-15. doi:10.1145/3290605.3300767

Digioia AM, Jaramaz B, Nikou C, et al. Surgical navigation for total hip replacement with the use of hipnav. Oper Tech Orthop. 2000;10:3-8. doi:10.1016/S1048-6666(00)80036-1

Ogawa H, Hasegawa S, Tsukada S, et al. A pilot study of augmented reality technology applied to the acetabular cup placement during total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1833-1837. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.01.067

Shen F, Chen B, Guo Q, et al. Augmented reality patient-specific reconstruction plate design for pelvic and acetabular fracture surgery. Int J CARS. 2013;8:169-179. doi:10.1007/s11548-012-0775-5

Cho HS, Park YK, Gupta S, et al. Augmented reality in bone tumour resection: an experimental study. Bone Joint Res. 2017;6:137-143. doi:10.1302/2046-3758.63.bjr-2016-0289.r1

Wu X, Liu R, Yu J, et al. Mixed reality technology launches in orthopedic surgery for comprehensive preoperative management of complicated cervical fractures. Surg Innov. 2018;25:421-422. doi:10.1177/1553350618761758

Dossett HG, Arthur JR, Makovicka JL, et al. A randomized controlled trial of kinematically and mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasties: long-term follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:S209-S214. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.03.065

Kazarian GS, Haddad FS, Donaldson MJ, et al. Implant malalignment may be a risk factor for poor patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) following total knee arthroplasty (TKA). J Arthroplasty. 2022;37:S129-S133. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2022.02.087

Peng Y, Arauz P, An S, et al. Does component alignment affect patient reported outcomes following bicruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty? An in vivo three-dimensional analysis. J Knee Surg. 2020;33:798-803. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1688500

D’Lima DD, Urquhart AG, Buehler KO, et al. The effect of the orientation of the acetabular and femoral components on the range of motion of the hip at different head-neck ratios. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:315-321. doi:10.2106/00004623-200003000-00003

Yamaguchi M, Akisue T, Bauer TW, et al. The spatial location of impingement in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:305-313. doi:10.1016/s0883-5403(00)90601-6

Grammatopoulos G, Alvand A, Monk AP, et al. Surgeons’ accuracy in achieving their desired acetabular component orientation. J Bone Joint Surg. 2016;98:e72. doi:10.2106/JBJS.15.01080

Kennedy JG, Rogers WB, Soffe KE, et al. Effect of acetabular component orientation on recurrent dislocation, pelvic osteolysis, polyethylene wear, and component migration. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:530-534. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(98)90052-3

Del Schutte H, Lipman AJ, Bannar SM, et al. Effects of acetabular abduction on cup wear rates in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:621-626. doi:10.1016/S0883-5403(98)80003-X

Aresti N, Kassam J, Bartlett D, et al. Primary care management of postoperative shoulder, hip, and knee arthroplasty. BMJ. 2017;359:j4431. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4431

HipInsightTM System. Zimmer Biomet. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.zimmerbiomet.com/en/products-and-solutions/zb-edge/mixed-reality-portfolio/hipinsight-system.html

ARVIS. Insight Medical Systems. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.insightmedsys.com/arvis

Sun DC, Murphy WS, Amundson AJ, et al. Validation of a novel method of measuring cup orientation using biplanar simultaneous radiographic images. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:S252-S256. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.04.011

Tsukada S, Ogawa H, Nishino M, et al. Augmented reality-assisted femoral bone resection in total knee arthroplasty. JBJS Open Access. 2021;6:e21.00001. doi:10.2106/JBJS.OA.21.00001

Castellarin G, Bori E, Barbieux E, et al. Is total knee arthroplasty surgical performance enhanced using augmented reality? A single-center study on 76 consecutive patients. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39:332-335. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.08.013

Choi YJ, Ra HJ. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2016;28:1. doi:10.5792/ksrr.2016.28.1.1

Hazratwala K, Gouk C, Wilkinson MPR, et al. Navigated functional alignment total knee arthroplasty achieves reliable, reproducible and accurate results with high patient satisfaction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31:3861-3870. doi:10.1007/s00167-023-07327-w

Knee+. Pixee Medical. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.pixee-medical.com/en/products/knee-nexsight/

KNEE | NEXTAR. Nextar. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://nextar.medacta.com/knee

POLARIS AR receives clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for STELLAR Knee. News release. PRNewswire. November 3, 2023. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/polarisar-receives-clearance-from-the-us-food-and-drug-administration-for-stellar-knee-301976747.html

van Overschelde P, Vansintjan P, Byn P, Lapierre C, van Lysebettens W. Does augmented reality improve clinical outcome in TKA? A prospective observational report. In: The 20th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Computer Assisted Orthopaedic Surgery. 2022:170-174.

Sakellariou E, Alevrogiannis P, Alevrogianni F, et al. Single-center experience with Knee+TM augmented reality navigation system in primary total knee arthroplasty. World J Orthop. 2024;15:247-256. doi:10.5312/wjo.v15.i3.247

León-Muñoz VJ, Moya-Angeler J, López-López M, et al. Integration of square fiducial markers in patient-specific instrumentation and their applicability in knee surgery. J Pers Med. 2023;13:727. doi:10.3390/jpm13050727

Fucentese SF, Koch PP. A novel augmented reality-based surgical guidance system for total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021;141:2227-2233. doi:10.1007/s00402-021-04204-4

Sabatini L, Ascani D, Vezza D, et al. Novel surgical technique for total knee arthroplasty integrating kinematic alignment and real-time elongation of the ligaments using the NextAR system. J Pers Med. 2024;14:794. doi:10.3390/jpm14080794

Daher M, Ghanimeh J, Otayek J, et al. Augmented reality and shoulder replacement: a state-of-the-art review article. JSES Rev Rep Tech. 2023;3:274-278. doi:10.1016/j.xrrt.2023.01.008

Atmani H, Merienne F, Fofi D, et al. Computer aided surgery system for shoulder prosthesis placement. Comput Aided Surg. 2007;12:60-70. doi:10.3109/10929080701210832

Eichinger JK, Galvin JW. Management of complications after total shoulder arthroplasty. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;8:83-91. doi:10.1007/s12178-014-9251-x

Bonnevialle N, Melis B, Neyton L, et al. Aseptic glenoid loosening or failure in total shoulder arthroplasty: revision with glenoid reimplantation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:745-751. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.08.009

Erickson BJ, Chalmers PN, Denard P, et al. Does commercially available shoulder arthroplasty preoperative planning software agree with surgeon measurements of version, inclination, and subluxation? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30:413-420. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2020.05.027

Werner BS, Hudek R, Burkhart KJ, et al. The influence of three-dimensional planning on decision-making in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:1477-1483. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.01.006

Blueprint. Stryker. Updated August 2025. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.stryker.com/us/en/trauma-and-extremities/products/blueprint.html

NextAR Shoulder. Medacta. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://nextar.medacta.com/shoulder

Baumgarten KM. Accuracy of Blueprint software in predicting range of motion 1 year after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:1088-1094. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2022.12.009

Rojas JT, Jost B, Zipeto C, et al. Glenoid component placement in reverse shoulder arthroplasty assisted with augmented reality through a head-mounted display leads to low deviation between planned and postoperative parameters. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:e587-e596. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2023.05.002

Dey Hazra RO, Paksoy A, Imiolczyk JP, et al. Augmented reality–assisted intraoperative navigation increases precision of glenoid inclination in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2025;34(2):577-583. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2024.05.039

The Integration of Extended Reality in Arthroplasty: Reviewing Technological Progress and Clinical Benefits

The Integration of Extended Reality in Arthroplasty: Reviewing Technological Progress and Clinical Benefits

A Candida Glabrata-Associated Prosthetic Joint Infection: Case Report and Literature Review

A Candida Glabrata-Associated Prosthetic Joint Infection: Case Report and Literature Review

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) occurs in about 1% to 2% of joint replacements. 1 Risk factors include immunosuppression, diabetes, chronic illnesses, and prolonged operative time.2 Bacterial infections constitute most of these infections, while fungal pathogens account for about 1%. Candida (C.) species, predominantly C. albicans, are responsible for most PJIs.1,3 In contrast, C. glabrata is a rare cause of fungal PJI, with only 18 PJI cases currently reported in the literature.4 C. glabrata PJI occurs more frequently among immunosuppressed patients and is associated with a higher treatment failure rate despite antifungal therapy.5 Treatment of fungal PJI is often complicated, involving multiple surgical debridements, prolonged antifungal therapy, and in some cases, prosthesis removal.6 However, given the rarity of C. glabrata as a PJI pathogen, no standardized treatment guidelines exist, leading to potential delays in diagnosis and tailored treatment.7,8

CASE PRESENTATION

A male Vietnam veteran aged 75 years presented to the emergency department in July 2023 with a fluid collection over his left hip surgical incision site. The patient had a complex medical history that included chronic kidney disease, well-controlled type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and osteoarthritis. His history was further complicated by nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with hepatocellular carcinoma that was treated with transarterial radioembolization and yttrium-90. The patient had undergone a left total hip arthroplasty in 1996 and subsequent open reduction and internal fixation about 9 months prior to his presentation. The patient reported the fluid had been present for about 6 weeks, while he received outpatient monitoring by the orthopedic surgery service. He sought emergency care after noting a moderate amount of purulent discharge on his clothing originating from his hip. In the week prior to admission, the patient observed progressive erythema, warmth, and tenderness over the incision site. Despite these symptoms, the patient remained ambulatory and able to walk long distances with the use of an assistive device.

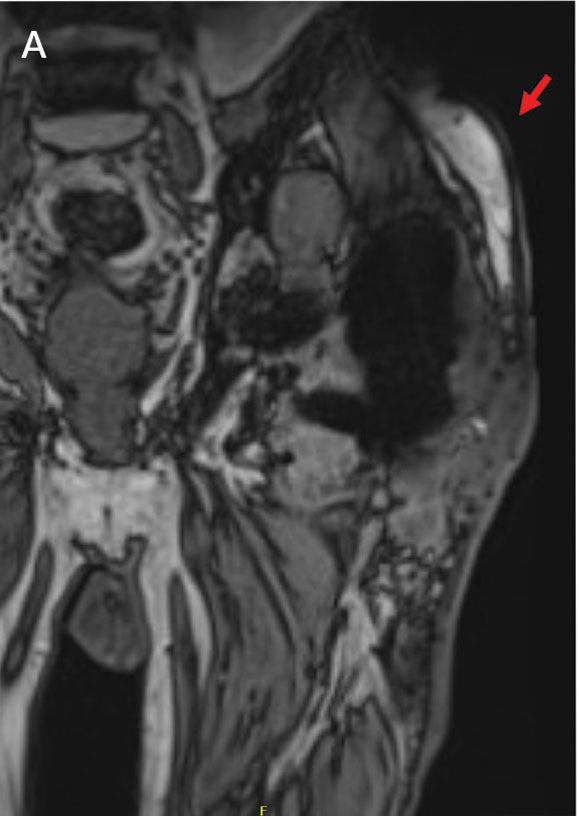

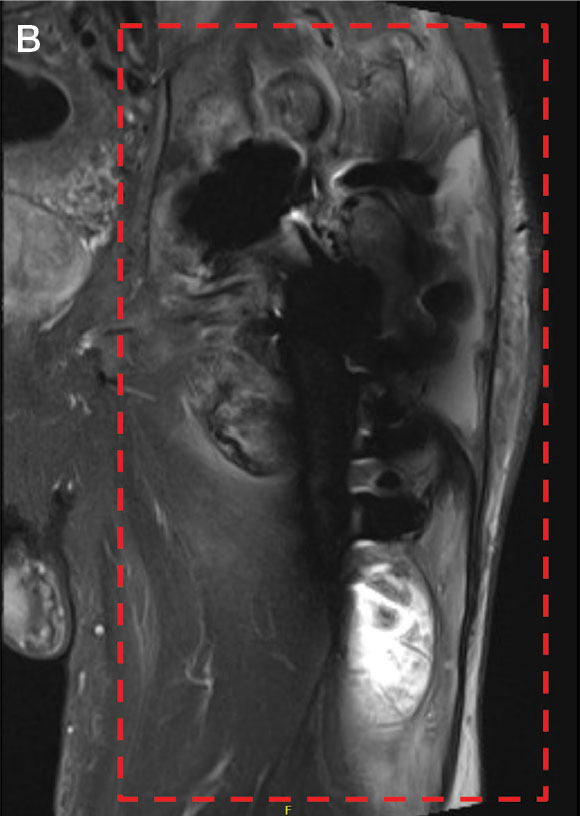

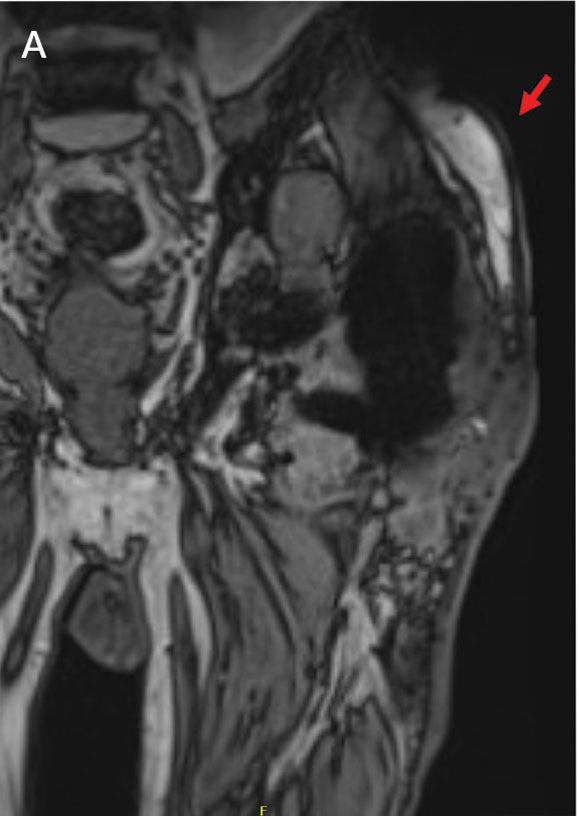

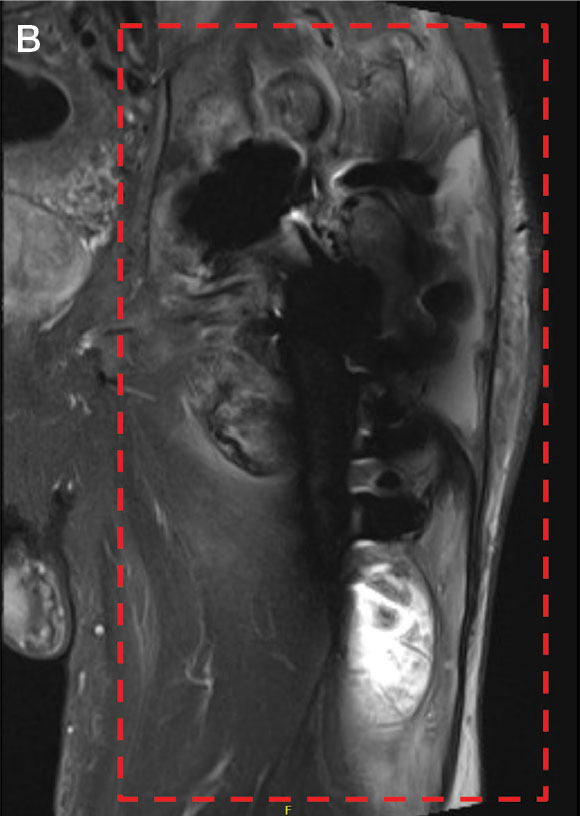

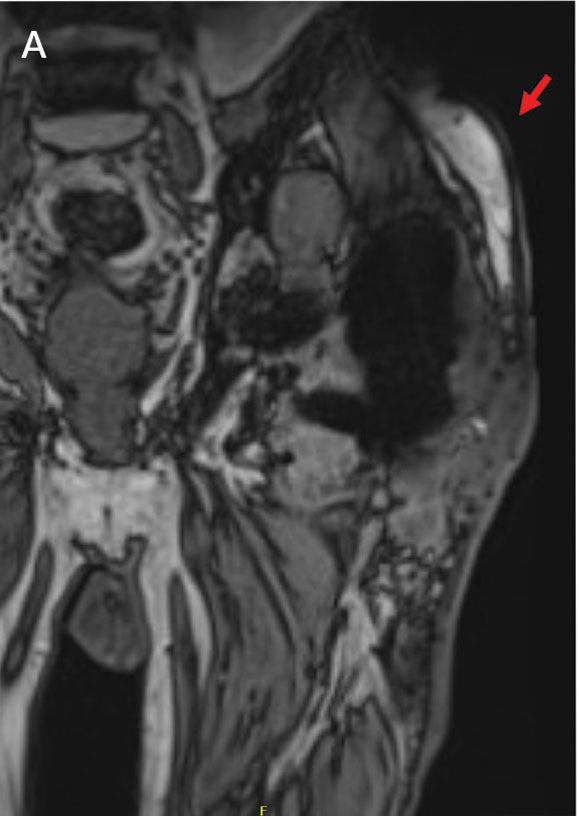

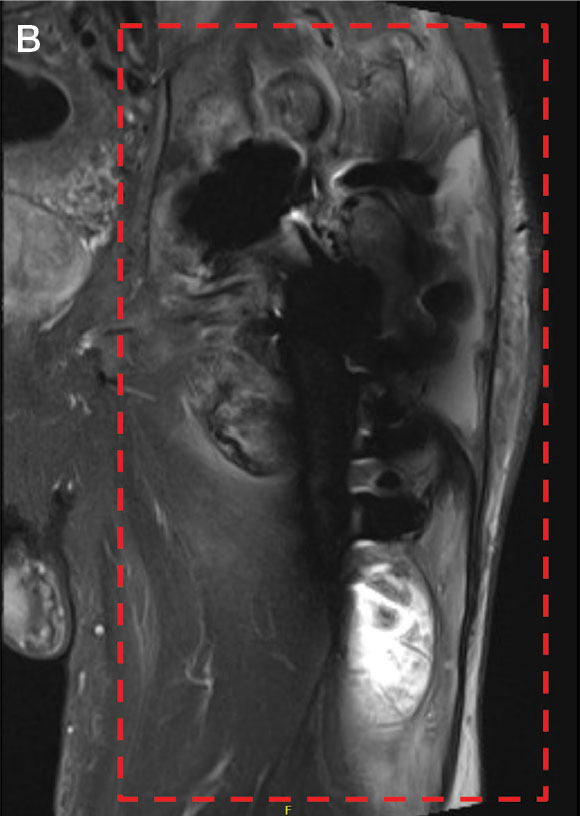

Upon presentation, the patient was afebrile and normotensive. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 77 mm/h (reference range, 0-20 mm/h) and a C-reactive protein of 9.8 mg/L (reference range, 0-2.5 mg/L), suggesting an underlying infectious process. A physical examination revealed a well-healed incision over the left hip with a poorly defined area of fluctuance and evidence of wound dehiscence. The left lower extremity was swollen with 2+ pitting edema, but tenderness was localized to the incision site. Magnetic resonance imaging of the left hip revealed a multiloculated fluid collection abutting the left greater trochanter with extension to the skin surface and inferior extension along the entire length of the surgical fixation hardware (Figure).

Upon admission, orthopedic surgery performed a bedside aspiration of the fluid collection. Samples were sent for analysis, including cell count and bacterial and fungal cultures. Initial blood cultures were sterile. Due to concerns for a bacterial infection, the patient was started on empiric intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone 2 g/day and IV vancomycin 1250 mg/day. Synovial fluid analysis revealed an elevated white blood cell count of 45,000/ìL, but bacterial cultures were negative. Five days after admission, the fungal culture from the left hip wound was notable for presence of C. glabrata, prompting an infectious diseases (ID) consultation. IV micafungin 100 mg/day was initiated as empiric antifungal therapy.

ID and orthopedic surgery teams determined that a combined medical and surgical approach would be best suited for infection control. They proposed 2 main approaches: complete hardware replacement with washout, which carried a higher morbidity risk but a better chance of infection resolution, or partial hardware replacement with washout, which was associated with a lower morbidity risk but a higher risk of infection persistence and recurrence. This decision was particularly challenging for the patient, who prioritized maintaining his functional status, including his ability to continue dancing for pleasure. The patient opted for a more conservative approach, electing to proceed with antifungal therapy and debridement while retaining the prosthetic joint.

After 11 days of hospitalization, the patient was discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter for long-term antifungal infusions of micafungin 150 mg/day at home. Fungal sensitivity test results several days after discharge confirmed susceptibility to micafungin.

About 2 weeks after discharge, the patient underwent debridement and implant retention (DAIR). Wound cultures were positive for C. glabrata, Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum. Based on susceptibilities, he completed a 2-month course of IV micafungin 150 mg daily and daptomycin 750 mg daily, followed by an oral suppressive regimen consisting of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily, amoxicillin-clavulanate 2 g twice daily, and fluconazole initially 800 mg daily adjusted to 400 mg daily. The patient continued wound management with twice-daily dressing changes.

Nine months after DAIR, the patient remained on suppressive antifungal and antibacterial therapy. He continued to experience serous drainage from the wound, which greatly affected his quality of life. After discussion with his family and the orthopedic surgery team, he agreed to proceed with a 2-staged revision arthroplasty involving prosthetic explant and antibiotic spacer placement. However, the surgery was postponed due to findings of anemia (hemoglobin, 8.9 g/dL) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 73 x 103/λL). At the time of this report, the patient was being monitored closely with his multidisciplinary care team for the planned orthopedic procedure.

DISCUSSION

PJI is the most common cause of primary hip arthroplasty failure; however, fungal species only make up about 1% of PJIs.3,9-11 Patients are typically immunocompromised, undergoing antineoplastic therapies for malignancy, or have other comorbid conditions such as diabetes.12,13 C. glabrata presents a unique diagnostic and therapeutic challenge as it is not only rare but also notorious for its resistance to common antifungal agents. C. glabrata is known to develop multidrug resistance through the rapid accumulation of genomic mutations.14 Its propensity towards forming protective biofilm also arms it with intrinsic resistance to agents like fluconazole.15 Furthermore, based on a review of the available reports in the literature, C. glabrata PJIs are often insidious and present with symptoms closely mimicking those of bacterial PJIs, as it did in the patient in this case.16

Synovial fluid analysis, fungal cultures, and sensitivity testing are paramount for ensuring proper diagnosis for fungal PJI. The patient in this case was empirically treated with micafungin based on recommendations from the ID team. When the sensitivities results were reviewed, the same antifungal therapy was continued. Echinocandins have a favorable toxicity profile in long-term use, as well as efficacy against biofilm-producing organisms like C. glabrata.17,18

While there are a few cases citing DAIR as a feasible surgical strategy for treating fungal PJI, more recent studies have reported greater success with a 2-staged revision arthroplasty involving some combination of debridement, placement of antibiotic-loaded bone cement spacers, and partial or total exchange of the infected prosthetic joint.4,19-23 In this case, complete hardware replacement would have offered the patient the most favorable outlook for eliminating this fungal infection. However, given the patient’s advanced age, significant underlying comorbidities, and functional status, medical management with antifungal therapy and DAIR was favored.

Based on the discussion from the 6-month follow-up visit, the patient was experiencing progressive and persistent wound drainage and frequent dressing changes, highlighting the limitations of medical management for PJI in the setting of retained prosthesis. If the patient ultimately proceeds with a more invasive surgical intervention, another important consideration will be the likelihood of fungal PJI recurrence. At present, fungal PJI recurrence rates following antifungal and surgical treatment have been reported to range between 0% to 50%, which is too imprecise to be considered clinically useful.22-24

Given the ambiguity surrounding management guidelines and limited treatment options, it is crucial to emphasize the timeline of this patient’s clinical presentation and subsequent course of treatment. Upon presentation to the ED in late July, fungal PJI was considered less likely. Initial blood cultures from presentation were negative, which is common with PJIs. It was not until 5 days later that the left hip wound culture showed moderate growth of C. glabrata. Identifying a PJI is clinically challenging due to the lack of standardized diagnostic criteria. However, timely identification and diagnosis of fungal PJI with appropriate antifungal therapy, in patients with limited curative options due to comorbidities, can significantly improve quality of life and overall outcomes.25 Routine fungal and mycobacterial cultures are not currently recommended in PJI guidelines, but this case illustrates it is imperative in immunocompromised hosts.26

This case and the current paucity of similar cases in the literature stress the importance of clinicians publishing their experience in the management of fungal PJI. We strongly recommend that clinicians approach each suspected PJI with careful consideration of the patient’s unique risk factors, comorbidities, and goals of care, when deciding on a curative vs suppressive approach to therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

This case report highlights the importance of considering fungal pathogens for PJIs, especially in high-risk patients, the value of obtaining fungal cultures, the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach, the role of antifungal susceptibility testing, and consideration for the feasibility of a surgical intervention. It underscores the challenges in diagnosis and treatment of C. glabrata-associated PJI, emphasizing the importance of clinician experience-sharing in developing evidence-based management strategies. As the understanding of fungal PJI evolves, continued research and clinical data collection remain crucial for improving patient outcomes in the management of these complex cases.

- Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, et al. Executive summary: diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(1):1-10. doi:10.1093/cid/cis966

- Eka A, Chen AF. Patient-related medical risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection of the hip and knee. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3(16):233. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.09.26

- Darouiche RO, Hamill RJ, Musher DM, Young EJ, Harris RL. Periprosthetic candidal infections following arthroplasty. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(1):89-96. doi:10.1093/clinids/11.1.89

- Koutserimpas C, Zervakis SG, Maraki S, et al. Non-albicans Candida prosthetic joint infections: a systematic review of treatment. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7(12):1430- 1443. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v7.i12.1430

- Fidel PL Jr, Vazquez JA, Sobel JD. Candida glabrata: review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical disease with comparison to C. albicans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(1):80-96. doi:10.1128/CMR.12.1.80

- Aboltins C, Daffy J, Choong P, Stanley P. Current concepts in the management of prosthetic joint infection. Intern Med J. 2014;44(9):834-840. doi:10.1111/imj.12510

- Lee YR, Kim HJ, Lee EJ, Sohn JW, Kim MJ, Yoon YK. Prosthetic joint infections caused by candida species: a systematic review and a case series. Mycopathologia. 2019;184(1):23-33. doi:10.1007/s11046-018-0286-1

- Herndon CL, Rowe TM, Metcalf RW, et al. Treatment outcomes of fungal periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38(11):2436-2440.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.05.009

- Delaunay C, Hamadouche M, Girard J, Duhamel A; SoFCOT. What are the causes for failures of primary hip arthroplasties in France? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(12): 3863-3869. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-2935-5

- Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Vail TP, Berry DJ. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1): 128-133. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00155

- Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987-99. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(4):579-586. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.83b4.11223

- Gonzalez MR, Bedi ADS, Karczewski D, Lozano-Calderon SA. Treatment and outcomes of fungal prosthetic joint infections: a systematic review of 225 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38(11):2464-2471.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.05.003

- Gonzalez MR, Pretell-Mazzini J, Lozano-Calderon SA. Risk factors and management of prosthetic joint infections in megaprostheses-a review of the literature. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023;13(1):25. doi:10.3390/antibiotics13010025

- Biswas C, Chen SC, Halliday C, et al. Identification of genetic markers of resistance to echinocandins, azoles and 5-fluorocytosine in Candida glabrata by next-generation sequencing: a feasibility study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(9):676.e7-676.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.03.014

- Hassan Y, Chew SY, Than LTL. Candida glabrata: pathogenicity and resistance mechanisms for adaptation and survival. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;7(8):667. doi:10.3390/jof7080667

- Aboltins C, Daffy J, Choong P, Stanley P. Current concepts in the management of prosthetic joint infection. Intern Med J. 2014;44(9):834-840. doi:10.1111/imj.12510

- Pierce CG, Uppuluri P, Tristan AR, et al. A simple and reproducible 96-well plate-based method for the formation of fungal biofilms and its application to antifungal susceptibility testing. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(9):1494-1500. doi:10.1038/nport.2008.141

- Koutserimpas C, Samonis G, Velivassakis E, Iliopoulou- Kosmadaki S, Kontakis G, Kofteridis DP. Candida glabrata prosthetic joint infection, successfully treated with anidulafungin: a case report and review of the literature. Mycoses. 2018;61(4):266-269. doi:10.1111/myc.12736

- Brooks DH, Pupparo F. Successful salvage of a primary total knee arthroplasty infected with Candida parapsilosis. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(6):707-712. doi:10.1016/s0883-5403(98)80017-x

- Merrer J, Dupont B, Nieszkowska A, De Jonghe B, Outin H. Candida albicans prosthetic arthritis treated with fluconazole alone. J Infect. 2001;42(3):208-209. doi:10.1053/jinf.2001.0819

- Koutserimpas C, Naoum S, Alpantaki K, et al. Fungal prosthetic joint infection in revised knee arthroplasty: an orthopaedic surgeon’s nightmare. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(7):1606. doi:10.3390/diagnostics12071606

- Gao Z, Li X, Du Y, Peng Y, Wu W, Zhou Y. Success rate of fungal peri-prosthetic joint infection treated by 2-stage revision and potential risk factors of treatment failure: a retrospective study. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:5549-5557. doi:10.12659/MSM.909168

- Hwang BH, Yoon JY, Nam CH, et al. Fungal periprosthetic joint infection after primary total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(5):656-659. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.94B5.28125

- Ueng SW, Lee CY, Hu CC, Hsieh PH, Chang Y. What is the success of treatment of hip and knee candidal periprosthetic joint infection? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(9):3002-3009. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3007-6

- Nodzo, Scott R. MD; Bauer, Thomas MD, PhD; Pottinger, et al. Conventional diagnostic challenges in periprosthetic joint infection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23 Suppl:S18-S25. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00385

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Diagnosis and prevention of periprosthetic joint infections. March 11, 2019. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://www.aaos.org/pjicpg

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) occurs in about 1% to 2% of joint replacements. 1 Risk factors include immunosuppression, diabetes, chronic illnesses, and prolonged operative time.2 Bacterial infections constitute most of these infections, while fungal pathogens account for about 1%. Candida (C.) species, predominantly C. albicans, are responsible for most PJIs.1,3 In contrast, C. glabrata is a rare cause of fungal PJI, with only 18 PJI cases currently reported in the literature.4 C. glabrata PJI occurs more frequently among immunosuppressed patients and is associated with a higher treatment failure rate despite antifungal therapy.5 Treatment of fungal PJI is often complicated, involving multiple surgical debridements, prolonged antifungal therapy, and in some cases, prosthesis removal.6 However, given the rarity of C. glabrata as a PJI pathogen, no standardized treatment guidelines exist, leading to potential delays in diagnosis and tailored treatment.7,8

CASE PRESENTATION