User login

Acute Renal Infarction

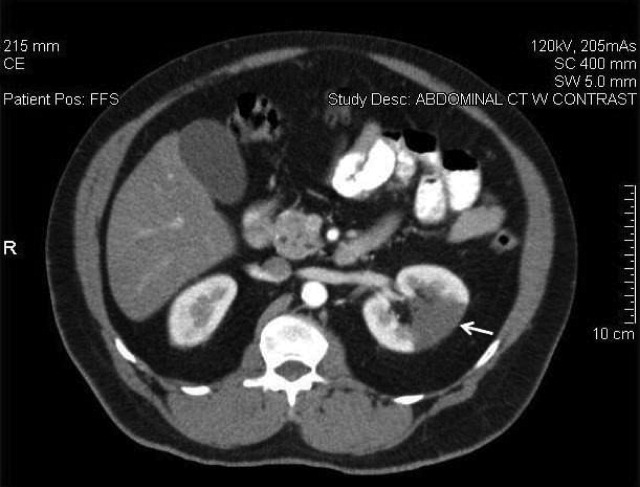

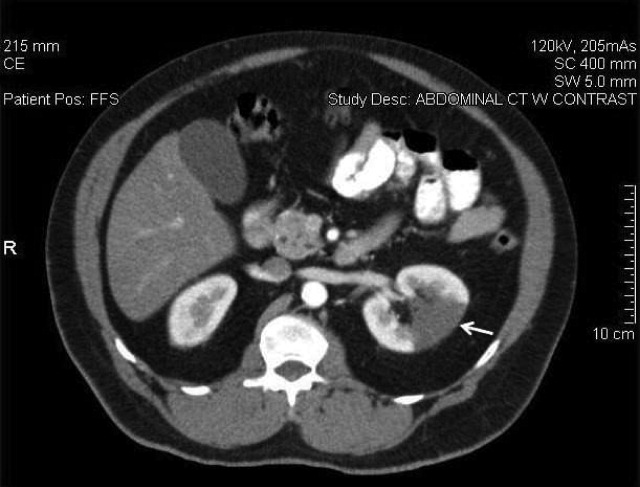

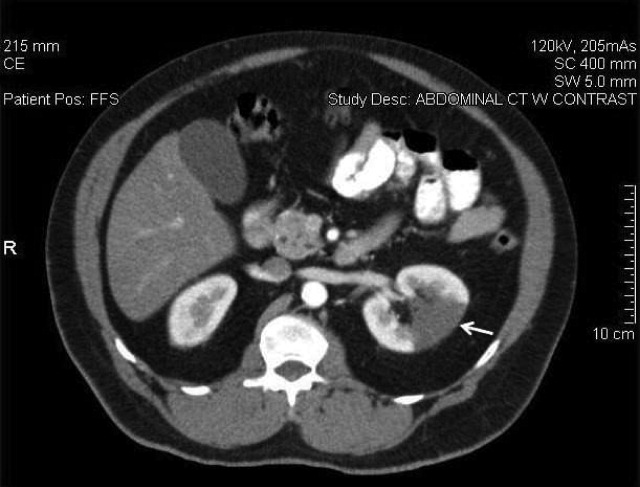

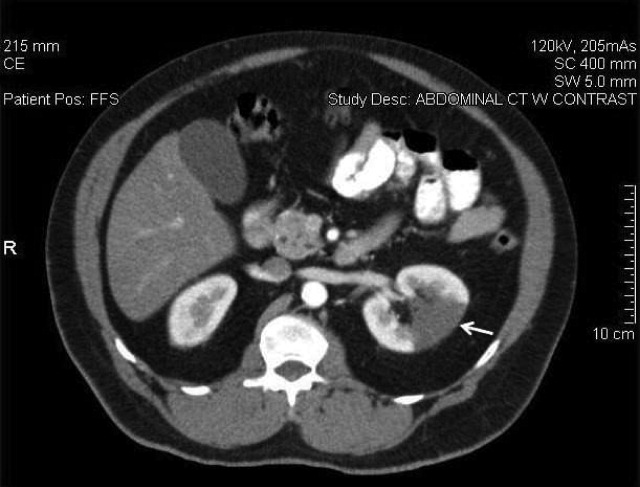

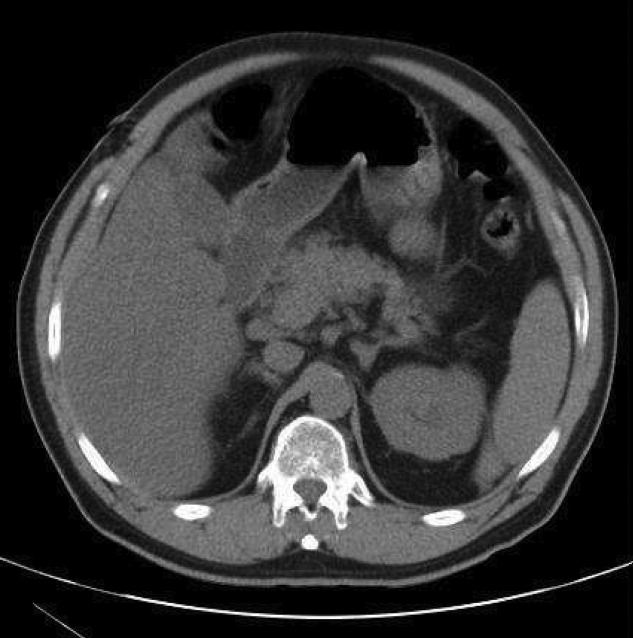

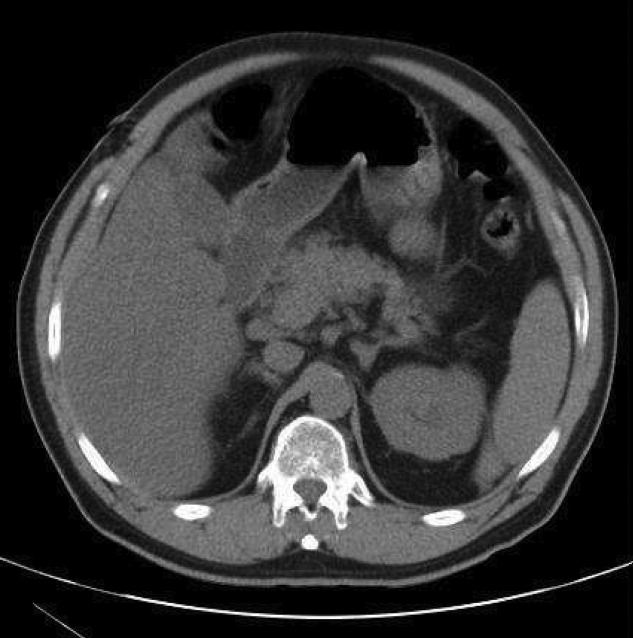

A 58‐year‐old man presented with a 1‐day history of left lower quadrant abdominal pain. He had a history of remote tobacco use, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. His white cell count was 18,500/mm,3 and urinalysis revealed hematuria. Contrast‐enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed decreased perfusion of a large section of the lower pole of the left kidney (Figure 1). On day 3, his flank pain persisted, despite hydration, analgesics, and intravenous (IV) antibiotics. His serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was elevated and renal infarction was suspected. Heparin was started and the patient was later discharged on warfarin. One month later, repeat contrast‐enhanced abdominal CT showed a less extensive wedge defect with scarring of the left kidney.

The diagnosis of acute renal infarction is often missed due to its nonspecific symptoms and the fact that it is an uncommon disease. It should be suspected in patients with acute flank pain and risk factors for thromboembolism including: valvular or ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and previous thromboembolic events.1, 2 Hypertension, which our patient had, is also a risk factor. In the appropriate setting hematuria and elevated LDH strongly suggest the diagnosis.3 Angiography remains the gold‐standard for diagnosis, but contrast‐enhanced CT is an acceptable alternative.3 In the setting of gross hematuria, we recommend that acute renal infarction should be suspected in all patients with the triad of persistent flank pain, high thromboembolic risk, and an increased LDH.

- ,,, et al.ED presentations of acute renal infarction.Am J Emerg Med.2007;25:164–169.

- ,,,.Renal artery embolism: clinical features and long‐term follow‐up of 17 cases.Ann Intern Med.1978;89:477–482.

- ,,, et al.Acute renal infarction. Clinical characteristics of 17 patients.Medicine (Baltimore).1999;78:386–394.

A 58‐year‐old man presented with a 1‐day history of left lower quadrant abdominal pain. He had a history of remote tobacco use, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. His white cell count was 18,500/mm,3 and urinalysis revealed hematuria. Contrast‐enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed decreased perfusion of a large section of the lower pole of the left kidney (Figure 1). On day 3, his flank pain persisted, despite hydration, analgesics, and intravenous (IV) antibiotics. His serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was elevated and renal infarction was suspected. Heparin was started and the patient was later discharged on warfarin. One month later, repeat contrast‐enhanced abdominal CT showed a less extensive wedge defect with scarring of the left kidney.

The diagnosis of acute renal infarction is often missed due to its nonspecific symptoms and the fact that it is an uncommon disease. It should be suspected in patients with acute flank pain and risk factors for thromboembolism including: valvular or ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and previous thromboembolic events.1, 2 Hypertension, which our patient had, is also a risk factor. In the appropriate setting hematuria and elevated LDH strongly suggest the diagnosis.3 Angiography remains the gold‐standard for diagnosis, but contrast‐enhanced CT is an acceptable alternative.3 In the setting of gross hematuria, we recommend that acute renal infarction should be suspected in all patients with the triad of persistent flank pain, high thromboembolic risk, and an increased LDH.

A 58‐year‐old man presented with a 1‐day history of left lower quadrant abdominal pain. He had a history of remote tobacco use, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. His white cell count was 18,500/mm,3 and urinalysis revealed hematuria. Contrast‐enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed decreased perfusion of a large section of the lower pole of the left kidney (Figure 1). On day 3, his flank pain persisted, despite hydration, analgesics, and intravenous (IV) antibiotics. His serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was elevated and renal infarction was suspected. Heparin was started and the patient was later discharged on warfarin. One month later, repeat contrast‐enhanced abdominal CT showed a less extensive wedge defect with scarring of the left kidney.

The diagnosis of acute renal infarction is often missed due to its nonspecific symptoms and the fact that it is an uncommon disease. It should be suspected in patients with acute flank pain and risk factors for thromboembolism including: valvular or ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and previous thromboembolic events.1, 2 Hypertension, which our patient had, is also a risk factor. In the appropriate setting hematuria and elevated LDH strongly suggest the diagnosis.3 Angiography remains the gold‐standard for diagnosis, but contrast‐enhanced CT is an acceptable alternative.3 In the setting of gross hematuria, we recommend that acute renal infarction should be suspected in all patients with the triad of persistent flank pain, high thromboembolic risk, and an increased LDH.

- ,,, et al.ED presentations of acute renal infarction.Am J Emerg Med.2007;25:164–169.

- ,,,.Renal artery embolism: clinical features and long‐term follow‐up of 17 cases.Ann Intern Med.1978;89:477–482.

- ,,, et al.Acute renal infarction. Clinical characteristics of 17 patients.Medicine (Baltimore).1999;78:386–394.

- ,,, et al.ED presentations of acute renal infarction.Am J Emerg Med.2007;25:164–169.

- ,,,.Renal artery embolism: clinical features and long‐term follow‐up of 17 cases.Ann Intern Med.1978;89:477–482.

- ,,, et al.Acute renal infarction. Clinical characteristics of 17 patients.Medicine (Baltimore).1999;78:386–394.

Acute Pancreatitis with Eruptive Xanthomas

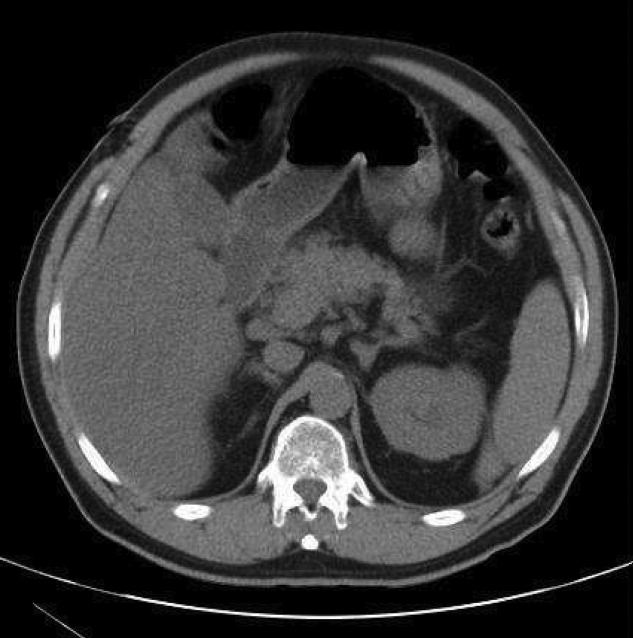

A 54‐year‐old man presented with a 1‐day history of epigastric abdominal pain. He also described 1 month of a nonpruritic but tender rash, on his right elbow, abdomen, buttocks, posterior thighs, and knees. He was obese with a past medical history remarkable for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus and hemoglobin A1C of 12.7. His abdomen was tender to palpation in the epigastric area with no rebound or guarding. Skin examination demonstrated multiple yellow waxy papules on the extensor surfaces of his arms, abdomen, thighs, knees, and buttocks, consistent with eruptive xanthomas (Figure 1). Laboratory values were significant for lipase at 852 g/L (normal, 8‐78 g/L) and triglycerides at 6200 mg/dL. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast demonstrated extensive inflammatory changes surrounding the head of the pancreas, consistent with acute pancreatitis (Figure 2). The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis secondary to hypertriglyceridemia was made. Dietary and pharmacologic interventions helped decrease the triglyceride level and his rash and abdominal pain were improved at outpatient follow‐up 2 weeks later.

Hypertriglyceridemia increases the risk of acute pancreatitis.1 Eruptive xanthomas can be associated with primary and secondary hypertriglyceridemia, particularly in the setting of poorly controlled diabetes.2 The risk of acute pancreatitis and eruptive xanthomas increases when the level of serum triglyceride reaches the thousands.

Rapid recognition of eruptive xanthomas can assist in identifying the etiology of acute pancreatitis.

- .Hyperlipidemic pancreatitis. [Review].Gastroenterol Clin North Am.1990;19(4):783–791.

- .Xanthomas and hyperlipidemias.J Am Acad Dermatol.1985;13(1):1–30.

A 54‐year‐old man presented with a 1‐day history of epigastric abdominal pain. He also described 1 month of a nonpruritic but tender rash, on his right elbow, abdomen, buttocks, posterior thighs, and knees. He was obese with a past medical history remarkable for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus and hemoglobin A1C of 12.7. His abdomen was tender to palpation in the epigastric area with no rebound or guarding. Skin examination demonstrated multiple yellow waxy papules on the extensor surfaces of his arms, abdomen, thighs, knees, and buttocks, consistent with eruptive xanthomas (Figure 1). Laboratory values were significant for lipase at 852 g/L (normal, 8‐78 g/L) and triglycerides at 6200 mg/dL. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast demonstrated extensive inflammatory changes surrounding the head of the pancreas, consistent with acute pancreatitis (Figure 2). The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis secondary to hypertriglyceridemia was made. Dietary and pharmacologic interventions helped decrease the triglyceride level and his rash and abdominal pain were improved at outpatient follow‐up 2 weeks later.

Hypertriglyceridemia increases the risk of acute pancreatitis.1 Eruptive xanthomas can be associated with primary and secondary hypertriglyceridemia, particularly in the setting of poorly controlled diabetes.2 The risk of acute pancreatitis and eruptive xanthomas increases when the level of serum triglyceride reaches the thousands.

Rapid recognition of eruptive xanthomas can assist in identifying the etiology of acute pancreatitis.

A 54‐year‐old man presented with a 1‐day history of epigastric abdominal pain. He also described 1 month of a nonpruritic but tender rash, on his right elbow, abdomen, buttocks, posterior thighs, and knees. He was obese with a past medical history remarkable for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus and hemoglobin A1C of 12.7. His abdomen was tender to palpation in the epigastric area with no rebound or guarding. Skin examination demonstrated multiple yellow waxy papules on the extensor surfaces of his arms, abdomen, thighs, knees, and buttocks, consistent with eruptive xanthomas (Figure 1). Laboratory values were significant for lipase at 852 g/L (normal, 8‐78 g/L) and triglycerides at 6200 mg/dL. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast demonstrated extensive inflammatory changes surrounding the head of the pancreas, consistent with acute pancreatitis (Figure 2). The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis secondary to hypertriglyceridemia was made. Dietary and pharmacologic interventions helped decrease the triglyceride level and his rash and abdominal pain were improved at outpatient follow‐up 2 weeks later.

Hypertriglyceridemia increases the risk of acute pancreatitis.1 Eruptive xanthomas can be associated with primary and secondary hypertriglyceridemia, particularly in the setting of poorly controlled diabetes.2 The risk of acute pancreatitis and eruptive xanthomas increases when the level of serum triglyceride reaches the thousands.

Rapid recognition of eruptive xanthomas can assist in identifying the etiology of acute pancreatitis.

- .Hyperlipidemic pancreatitis. [Review].Gastroenterol Clin North Am.1990;19(4):783–791.

- .Xanthomas and hyperlipidemias.J Am Acad Dermatol.1985;13(1):1–30.

- .Hyperlipidemic pancreatitis. [Review].Gastroenterol Clin North Am.1990;19(4):783–791.

- .Xanthomas and hyperlipidemias.J Am Acad Dermatol.1985;13(1):1–30.