User login

A Motivational Interviewing Training Program for Tobacco Cessation Counseling in Primary Care

Primary care providers (PCPs) need effective tools for activating health behavior change for the 125 million Americans living with a chronic condition.1 Smoking is an important and difficult behavior to change, and a motivator for quitting is tobacco cessation advice from a PCP.2,3 However, few PCPs provide comprehensive tobacco cessation counseling as part of routine care.4,5 One perceived barrier that providers report is their lack of training to be effective tobacco cessation advocates.4,6-8

Motivational interviewing (MI) promotes behavior change by using a nonadversarial approach aimed at resolving patient ambivalence. Motivational interviewing tools, such as asking open-ended questions, providing summary statements of what the patient expresses, reflective listening, and affirmations, are used to spur an intrinsic drive to change. These techniques have been applied to a broad range of health behaviors with positive outcomes and demonstrated efficacy.9-11 Furthermore, MI can be used in primary care for changing tobacco use, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and diet.12-14

Despite its efficacy, MI can be time-intensive to learn. Fortunately, even abbreviated MI can influence patient behavior.15,16 Rollnick and others have developed MI interventions that are deliverable in 5 to 10 minutes.17,18 These brief interventions focus on performing a rapid assessment of patients’ perceived importance and self-efficacy for change.17,18

There is increased interest in training health care professionals (HCPs) in MI, yet there is no consensus on the most effective training approach.19,20 Practitioners with many competing priorities often like to learn new skills through self-study or onetime workshops. Yet evidence suggests that these are not effective methods for gaining MI proficiency. Instead, MI training sessions that offer feedback and coaching are more effective in helping participants retain MI skills over time.21,22

The authors developed and successfully pilot-tested an MI training program called the Motivational Interviewing Smoking Treatment Enhancement Program (MI-STEP) for HCPs. This program was designed to facilitate tobacco cessation care in the VHA primary care patient centered medical home, which VHA calls patient aligned care teams (PACTs).23 The main conclusions of this pilot study have been reported elsewhere.24

The objective of this article is to describe the process evaluation the authors conducted during the MI-STEP study to gain a better understanding of how the implementation of the MI training program could be improved. The authors identified barriers and facilitators from the perspectives of MI champions and PACT practitioners.

Methods

Thirty-four PACT practitioners (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and pharmacists) at 2 VA medical centers were randomly assigned to a high- or moderate-intensity MI training program during the summer of 2012. This training was delivered by “MI champions,” who were recruited from PACTs and who attended a 3-day advanced training class on MI. The training included MI skills practice, group case analysis, various role-play exercises, and didactics adapted from the Rx for Change program.25 The curriculum also addressed tobacco cessation counseling using the national tobacco cessation guideline.2 Each site’s health behavior coordinator (HBC) also was recruited to be an MI champion. The HBCs are typically psychologists who have received prior training in MI as well as facilitator and clinician coaching. At the VA, HBCs are charged with integrating preventive services into care. The participating sites’ institutional review boards approved all study procedures.

MI-STEP Training Program

All 34 practitioners attended a half-day on-site MI training workshop led by the site’s HBC. This training covered the basics of MI and used interactive learning methods such as role-play (Table 1). The study practitioners also received self-study materials, and throughout the study period had access to the MI champions. Practitioners who were randomized to high-intensity MI training also attended 6 supplemental 1-hour “booster sessions” to enhance specific MI skills. The MI champions led 3 of the 1-hour booster sessions with a standard agenda, including patient cases and MI exercises. During the other 3 booster sessions, participants used patient cases to interact with a standardized patient over the telephone, and the MI champions provided feedback and coaching.

Process Evaluation

Six months after the program’s completion, investigators conducted an evaluation of the MI-STEP training program with MI champions and study practitioners. One-hour focus group sessions (2 in Minneapolis; 1 in Denver) were conducted with the MI champions by a co-investigator in Minneapolis and a facilitator in Denver. Notes were taken during the sessions. MI champions were asked about the quality of their training sessions, challenges to getting PACT members to participate in the site training, challenges to teaching MI, and how they felt MI fit within VA health care philosophy.

Ten training study practitioners were randomly selected and stratified based on group intensity assignment, discipline, and site to participate in in-depth interviews. The interviews lasted about 30 minutes, and Minneapolis study investigators conducted in-person interviews with local participants and telephone interviews with Denver participants. The interviews focused on experiences with both high- and moderate-intensity MI training programs, how MI was used in their practice, barriers to implementing MI, impressions of the MI training program, and their interactions with MI champions.

Focus group leaders were experienced interviewers who had not previously interacted with MI champions in the context of this study. Investigators conducting study practitioner interviews were blinded to group assignment. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Study investigators reviewed the focus group notes and interview transcripts, identified themes independently, and then discussed group themes. The most salient themes were selected to inform implementation of a larger scale MI training program.

Results

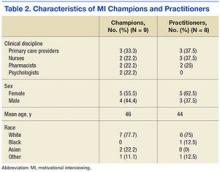

Nine MI champions participated in the focus groups, and 8 study practitioners from both sites representing all clinical disciplines completed in-depth interviews. Table 2 identifies the characteristics of each population.

MI Champion Focus Group Themes

The champions were asked to discuss all aspects of the program, including their training as champions, role as trainers, attitudes about using MI during patient encounters, and participation in the training program. Themes from the MI champion focus groups were placed in the following categories based on the authors’ analytic approach: training MI champions, training study practitioners, and attitudes about MI.

Training MI champions. The champions identified role-play exercises and receiving feedback as strengths of the training program. The champions also expressed the desire for more hands-on practice, especially in small groups. They wanted additional training on teaching MI and facilitating the booster sessions. The champions wanted an expert to train them on how to give feedback and how to best coach practitioners in their use of MI. Champions expressed a desire to have follow-up training sessions with the standardized patient to help them hone their newly acquired coaching skills.

Training study practitioners. The champions’ key role was to train local practitioners and lead the booster sessions for the high-intensity MI training group. Champions felt ill-prepared to fully cover the training materials during the initial half-day workshop and 6 booster sessions. Champions identified difficulty coordinating schedules with the practitioners and lack of compensation for participation as significant barriers to implementing the booster sessions. Champions felt that using a standardized patient during the booster sessions was a strength of the program and that making the cases more realistic could have further enhanced the program.

Attitudes about MI. Champions from both sites perceived MI to have a positive impact on patient care. However, all champions noted there were challenges in using MI in practice. Champions felt MI takes time, energy, and practice to gain proficiency. The current primary care system is not set up to support the use of MI. The appointment time slots are fixed, and VHA goals and the spirit of MI are not always compatible. VHA performance measures encourage providers to achieve performance targets with each patient, often requiring use of directives for patients on what to do. In contrast, MI encourages the patient to take the lead on goal setting and prioritizing.

Study Practitioner Interview Themes

The practitioners were asked to discuss MI skills training, using MI skills with patients, integrating MI into daily practice, getting other PACT members involved, booster sessions, interactions with champions, and suggestions for improving the MI program. Themes from the study practitioner interviews were grouped into the following categories: MI skills training, using MI skills, integrating MI into practice, and suggestions for improving MI training (Table 3).

MI skills training. Overall, the MI high-intensity participants stated they learned useful skills. They reported asking more questions that are open-ended and were more aware of the patient’s perspective. Practitioners reported that booster sessions provided a way to reinforce, refine, and practice their MI skills. Practitioners reported that having the champion located in their own PACT was critical for connecting with their champion between sessions. Nurses and doctors reported that not having time to meet with champions was a barrier, while pharmacists reported more flexibility.

The moderate-intensity participants reported that the training had less impact. Half the respondents reported that they did not remember much of the MI training and either forgot or did not use the newly learned MI skills.

Using MI skills. Both high- and moderate-intensity participants reported using open-ended questions, reflections, affirmations, motivation scales, and active listening.

Practitioners reported that MI helped them focus on patient-centered care, since MI is collaborative. Even when a session was not successful in leading to behavior change, practitioners felt more satisfied with the quality of the interaction.

Integrating MI into practice. The high- and moderate-intensity practitioners had different perceptions of using MI in daily practice. High-intensity participants thought MI required an initial time investment, but that would be balanced by a decrease in the number of follow-up visits needed and/or delay the time between visits. The moderate-intensity participants were more likely to report struggling with the amount of time MI took.

Suggestions for improving MI training. Practitioners from both training groups offered suggestions for improving MI training. Supervisor buy-in was deemed critical to getting other PACT members involved. Practitioners suggested providing compensation or making training mandatory to help motivate others to participate in MI training. Also, practitioners were ready to expand the MI training beyond smoking cessation to incorporate other diseases and multiple comorbidities.

The moderate-intensity participants suggested more training, practice, follow-up, and feedback. These participants also suggested boosterlike sessions.

Discussion

Champions and study practitioners reported that learning MI skills was useful. The participants felt that MI was consistent with their personal philosophies regarding patient-centered care and that MI had a positive impact on patient care. Practitioners and MI champions offered several insights for improving the delivery of MI training. First, practitioners and champions highlighted how important practice and feedback were to learning MI. Booster sessions, standardized patients, and critical feedback enhanced learning.

Second, champions reported that they wanted more training in how to teach MI. Third, practitioners and champions repeatedly stated that finding the time needed to become proficient in MI was difficult and that using the MI approach with patients took additional time during clinical sessions. However, participants in the high-intensity group reported more satisfaction with the quality of their patient encounters and the freedom to follow up with patients less often.

There were aspects of the environment and MI training program that facilitated the MI learning process. The high-intensity group cited booster session feedback as being reinforcing; the moderate-intensity group expressed a desire to practice their newly acquired skill and felt feedback and coaching would have enhanced their learning. Practitioners and champions reported that using a standardized patient to enhance experiential learning activities was an asset. Standardized patients have been used successfully in other training programs.21

Implementing an MI training program posed a number of challenges. The biggest barrier was lack of time. PACT members found it difficult to attend a half-day MI workshop, practice MI skills, and incorporate MI routinely into daily practice. However, without the investment of time, even basic MI proficiency is unachievable.22

This study highlighted several ways to improve feedback and coaching. First, the authors would expand the MI champion curriculum to include training to provide effective feedback/coaching. Second, the authors would train the standardized patient on how to provide feedback to the MI learner. As implemented, the standardized patient evaluated the learner only on whether the patient felt “heard” by the learner.

Perhaps most critical to the success of an MI training program is institutional support. There needs to be adequate time and space for the training process as well as support for ongoing learning and feedback as MI skills are refined. Furthermore, sufficient time is needed during patients’ appointments to allow for MI-oriented conversations. Time is an important, valuable, and scarce resource that institutions control. Administrators should realize that the up-front investment is likely to provide a downstream return as providers become proficient in MI.

There is an urgent need to find ways to incorporate training into the daily practice of busy HCPs. Although this study was limited by its small sample, it demonstrated the feasibility of implementing an MI training program for practitioners working in a busy primary care environment. This study offers concrete suggestions for overcoming barriers and enhancing facilitators, which can guide much needed larger studies as they examine MI training effectiveness on patient and clinician outcomes.

Champions and practitioners reported that learning MI was important, but opportunities to practice and receive critical feedback are needed to achieve proficiency and improve confidence. Both champions and study practitioners thought practicing with a standardized patient would enrich their learning. However, dedicated time for learning and practicing MI skills is critical and hard to arrange.

Conclusion

Practitioners can use MI to activate health behavior change in their patients. Training PACT practitioners to use MI is feasible. The results of this evaluation can be used to inform the next iteration of an MI training program for HCPs by highlighting the facilitators of and barriers to training.

Because of the interest in activating patient-centered health behavior change, these findings are important. The educational and practice opportunities were well received. Training with standardized patients and incorporating MI champions into PACTs facilitated training. However, the lack of time was a major barrier to learning and practicing MI skills and will need to be addressed. If effectively implemented, training providers by using an evidence-based approach, such as MI, can promote long-term health.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by VA Health Services Research & Development (HSR&D) Rapid Response Project 11-019. The Center for Chronic Disease Outcomes Research is supported by the VA, VHA, Office of Research and Development, and HSR&D. Dr. Widome was supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award.

1. Anderson G, Horvath J. The growing burden of chronic disease in America. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(3):263-270

2. Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008.

3. Park E, Eaton CA, Goldstein MG, et al. The development of a decisional balance measure of physician smoking cessation interventions. Prev Med. 2001;33(4):261-267.

4. Ferketich AK, Khan Y, Wewers ME. Are physicians asking about tobacco use and assisting with cessation? Results from the 2001-2004 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS). Prev Med. 2006;43(6):472-476.

5. Marcy TW, Skelly J, Shiffman RN, Flynn BS. Facilitating adherence to the tobacco use treatment guideline with computer-mediated decision support systems: physician and clinic office manager perspectives. Prev Med. 2005;41(2):479-487.

6. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465.

7. Jaén CR, McIlvain H, Pol L, Phillips RL Jr, Flocke S, Crabtree BF. Tailoring tobacco counseling to the competing demands in the clinical encounter. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(10):859-863.

8. Malte CA, McFall M, Chow B, Beckham JC, Carmody TP, Saxon AJ. Survey of providers' attitudes toward integrating smoking cessation treatment into posttraumatic stress disorder care. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27(1):249-255.

9. Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91-111.

10. Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler BC. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008.

11. Miller WR. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behav Psychother. 1983;11(2):147-172.

12. Brodie DA, Inoue A. Motivational interviewing to promote physical activity for people with chronic heart failure. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50(5):518-527.

13. Perry CK, Rosenfeld AG, Bennett JA, Potempa K. Heart-to-Heart: promoting walking in rural women through motivational interviewing and group support. J Cardiovascular Nurs. 2007;22(4):304-312.

14. West DS, DiLillo V, Bursac Z, Gore SA, Greene PG. Motivational interviewing improves weight loss in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1081-1087.

15. Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Pierce JP, et al. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. JAMA. 1989;261(1):49-55.

16. Lancaster T, Stead L. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;18(4):CD000165.

17. Butler C, Rollnick S, Cohen D, Bachmann M, Russell I, Stott N. Motivational counseling versus brief advice for smokers in general practice: a randomized trial. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(445):611-616.

18. Rollnick S, Heather N, Bell A. Negotiating behaviour change in medical settings: the development of brief motivational interviewing. J Ment Health. 1992;1(1):25-37.

19. Madson MB, Loignon AC, Lane C. Training in motivational interviewing: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(1):101-109.

20. Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1050-1062.

21. Lundahl B, Burke BL. The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: a practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. J Clin Pyschol. 2009;65(11):1232-1245.

22. Miller WR, Moyers TB. Eight stages in Learning motivational interviewing. J Teaching Addict. 2006;5(1):13-15.

23. Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263-e272.

24. Fu S, Roth C, Battaglia CT, et al. Training primary care clinicians in motivational interviewing: a comparison of two models. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(1):61-68.

25. School of Pharmacy & Medicine University of California, San Francisco. Rx for change website. http://rxforchange.ucsf.edu/. Accessed May 25, 2016.

Primary care providers (PCPs) need effective tools for activating health behavior change for the 125 million Americans living with a chronic condition.1 Smoking is an important and difficult behavior to change, and a motivator for quitting is tobacco cessation advice from a PCP.2,3 However, few PCPs provide comprehensive tobacco cessation counseling as part of routine care.4,5 One perceived barrier that providers report is their lack of training to be effective tobacco cessation advocates.4,6-8

Motivational interviewing (MI) promotes behavior change by using a nonadversarial approach aimed at resolving patient ambivalence. Motivational interviewing tools, such as asking open-ended questions, providing summary statements of what the patient expresses, reflective listening, and affirmations, are used to spur an intrinsic drive to change. These techniques have been applied to a broad range of health behaviors with positive outcomes and demonstrated efficacy.9-11 Furthermore, MI can be used in primary care for changing tobacco use, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and diet.12-14

Despite its efficacy, MI can be time-intensive to learn. Fortunately, even abbreviated MI can influence patient behavior.15,16 Rollnick and others have developed MI interventions that are deliverable in 5 to 10 minutes.17,18 These brief interventions focus on performing a rapid assessment of patients’ perceived importance and self-efficacy for change.17,18

There is increased interest in training health care professionals (HCPs) in MI, yet there is no consensus on the most effective training approach.19,20 Practitioners with many competing priorities often like to learn new skills through self-study or onetime workshops. Yet evidence suggests that these are not effective methods for gaining MI proficiency. Instead, MI training sessions that offer feedback and coaching are more effective in helping participants retain MI skills over time.21,22

The authors developed and successfully pilot-tested an MI training program called the Motivational Interviewing Smoking Treatment Enhancement Program (MI-STEP) for HCPs. This program was designed to facilitate tobacco cessation care in the VHA primary care patient centered medical home, which VHA calls patient aligned care teams (PACTs).23 The main conclusions of this pilot study have been reported elsewhere.24

The objective of this article is to describe the process evaluation the authors conducted during the MI-STEP study to gain a better understanding of how the implementation of the MI training program could be improved. The authors identified barriers and facilitators from the perspectives of MI champions and PACT practitioners.

Methods

Thirty-four PACT practitioners (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and pharmacists) at 2 VA medical centers were randomly assigned to a high- or moderate-intensity MI training program during the summer of 2012. This training was delivered by “MI champions,” who were recruited from PACTs and who attended a 3-day advanced training class on MI. The training included MI skills practice, group case analysis, various role-play exercises, and didactics adapted from the Rx for Change program.25 The curriculum also addressed tobacco cessation counseling using the national tobacco cessation guideline.2 Each site’s health behavior coordinator (HBC) also was recruited to be an MI champion. The HBCs are typically psychologists who have received prior training in MI as well as facilitator and clinician coaching. At the VA, HBCs are charged with integrating preventive services into care. The participating sites’ institutional review boards approved all study procedures.

MI-STEP Training Program

All 34 practitioners attended a half-day on-site MI training workshop led by the site’s HBC. This training covered the basics of MI and used interactive learning methods such as role-play (Table 1). The study practitioners also received self-study materials, and throughout the study period had access to the MI champions. Practitioners who were randomized to high-intensity MI training also attended 6 supplemental 1-hour “booster sessions” to enhance specific MI skills. The MI champions led 3 of the 1-hour booster sessions with a standard agenda, including patient cases and MI exercises. During the other 3 booster sessions, participants used patient cases to interact with a standardized patient over the telephone, and the MI champions provided feedback and coaching.

Process Evaluation

Six months after the program’s completion, investigators conducted an evaluation of the MI-STEP training program with MI champions and study practitioners. One-hour focus group sessions (2 in Minneapolis; 1 in Denver) were conducted with the MI champions by a co-investigator in Minneapolis and a facilitator in Denver. Notes were taken during the sessions. MI champions were asked about the quality of their training sessions, challenges to getting PACT members to participate in the site training, challenges to teaching MI, and how they felt MI fit within VA health care philosophy.

Ten training study practitioners were randomly selected and stratified based on group intensity assignment, discipline, and site to participate in in-depth interviews. The interviews lasted about 30 minutes, and Minneapolis study investigators conducted in-person interviews with local participants and telephone interviews with Denver participants. The interviews focused on experiences with both high- and moderate-intensity MI training programs, how MI was used in their practice, barriers to implementing MI, impressions of the MI training program, and their interactions with MI champions.

Focus group leaders were experienced interviewers who had not previously interacted with MI champions in the context of this study. Investigators conducting study practitioner interviews were blinded to group assignment. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Study investigators reviewed the focus group notes and interview transcripts, identified themes independently, and then discussed group themes. The most salient themes were selected to inform implementation of a larger scale MI training program.

Results

Nine MI champions participated in the focus groups, and 8 study practitioners from both sites representing all clinical disciplines completed in-depth interviews. Table 2 identifies the characteristics of each population.

MI Champion Focus Group Themes

The champions were asked to discuss all aspects of the program, including their training as champions, role as trainers, attitudes about using MI during patient encounters, and participation in the training program. Themes from the MI champion focus groups were placed in the following categories based on the authors’ analytic approach: training MI champions, training study practitioners, and attitudes about MI.

Training MI champions. The champions identified role-play exercises and receiving feedback as strengths of the training program. The champions also expressed the desire for more hands-on practice, especially in small groups. They wanted additional training on teaching MI and facilitating the booster sessions. The champions wanted an expert to train them on how to give feedback and how to best coach practitioners in their use of MI. Champions expressed a desire to have follow-up training sessions with the standardized patient to help them hone their newly acquired coaching skills.

Training study practitioners. The champions’ key role was to train local practitioners and lead the booster sessions for the high-intensity MI training group. Champions felt ill-prepared to fully cover the training materials during the initial half-day workshop and 6 booster sessions. Champions identified difficulty coordinating schedules with the practitioners and lack of compensation for participation as significant barriers to implementing the booster sessions. Champions felt that using a standardized patient during the booster sessions was a strength of the program and that making the cases more realistic could have further enhanced the program.

Attitudes about MI. Champions from both sites perceived MI to have a positive impact on patient care. However, all champions noted there were challenges in using MI in practice. Champions felt MI takes time, energy, and practice to gain proficiency. The current primary care system is not set up to support the use of MI. The appointment time slots are fixed, and VHA goals and the spirit of MI are not always compatible. VHA performance measures encourage providers to achieve performance targets with each patient, often requiring use of directives for patients on what to do. In contrast, MI encourages the patient to take the lead on goal setting and prioritizing.

Study Practitioner Interview Themes

The practitioners were asked to discuss MI skills training, using MI skills with patients, integrating MI into daily practice, getting other PACT members involved, booster sessions, interactions with champions, and suggestions for improving the MI program. Themes from the study practitioner interviews were grouped into the following categories: MI skills training, using MI skills, integrating MI into practice, and suggestions for improving MI training (Table 3).

MI skills training. Overall, the MI high-intensity participants stated they learned useful skills. They reported asking more questions that are open-ended and were more aware of the patient’s perspective. Practitioners reported that booster sessions provided a way to reinforce, refine, and practice their MI skills. Practitioners reported that having the champion located in their own PACT was critical for connecting with their champion between sessions. Nurses and doctors reported that not having time to meet with champions was a barrier, while pharmacists reported more flexibility.

The moderate-intensity participants reported that the training had less impact. Half the respondents reported that they did not remember much of the MI training and either forgot or did not use the newly learned MI skills.

Using MI skills. Both high- and moderate-intensity participants reported using open-ended questions, reflections, affirmations, motivation scales, and active listening.

Practitioners reported that MI helped them focus on patient-centered care, since MI is collaborative. Even when a session was not successful in leading to behavior change, practitioners felt more satisfied with the quality of the interaction.

Integrating MI into practice. The high- and moderate-intensity practitioners had different perceptions of using MI in daily practice. High-intensity participants thought MI required an initial time investment, but that would be balanced by a decrease in the number of follow-up visits needed and/or delay the time between visits. The moderate-intensity participants were more likely to report struggling with the amount of time MI took.

Suggestions for improving MI training. Practitioners from both training groups offered suggestions for improving MI training. Supervisor buy-in was deemed critical to getting other PACT members involved. Practitioners suggested providing compensation or making training mandatory to help motivate others to participate in MI training. Also, practitioners were ready to expand the MI training beyond smoking cessation to incorporate other diseases and multiple comorbidities.

The moderate-intensity participants suggested more training, practice, follow-up, and feedback. These participants also suggested boosterlike sessions.

Discussion

Champions and study practitioners reported that learning MI skills was useful. The participants felt that MI was consistent with their personal philosophies regarding patient-centered care and that MI had a positive impact on patient care. Practitioners and MI champions offered several insights for improving the delivery of MI training. First, practitioners and champions highlighted how important practice and feedback were to learning MI. Booster sessions, standardized patients, and critical feedback enhanced learning.

Second, champions reported that they wanted more training in how to teach MI. Third, practitioners and champions repeatedly stated that finding the time needed to become proficient in MI was difficult and that using the MI approach with patients took additional time during clinical sessions. However, participants in the high-intensity group reported more satisfaction with the quality of their patient encounters and the freedom to follow up with patients less often.

There were aspects of the environment and MI training program that facilitated the MI learning process. The high-intensity group cited booster session feedback as being reinforcing; the moderate-intensity group expressed a desire to practice their newly acquired skill and felt feedback and coaching would have enhanced their learning. Practitioners and champions reported that using a standardized patient to enhance experiential learning activities was an asset. Standardized patients have been used successfully in other training programs.21

Implementing an MI training program posed a number of challenges. The biggest barrier was lack of time. PACT members found it difficult to attend a half-day MI workshop, practice MI skills, and incorporate MI routinely into daily practice. However, without the investment of time, even basic MI proficiency is unachievable.22

This study highlighted several ways to improve feedback and coaching. First, the authors would expand the MI champion curriculum to include training to provide effective feedback/coaching. Second, the authors would train the standardized patient on how to provide feedback to the MI learner. As implemented, the standardized patient evaluated the learner only on whether the patient felt “heard” by the learner.

Perhaps most critical to the success of an MI training program is institutional support. There needs to be adequate time and space for the training process as well as support for ongoing learning and feedback as MI skills are refined. Furthermore, sufficient time is needed during patients’ appointments to allow for MI-oriented conversations. Time is an important, valuable, and scarce resource that institutions control. Administrators should realize that the up-front investment is likely to provide a downstream return as providers become proficient in MI.

There is an urgent need to find ways to incorporate training into the daily practice of busy HCPs. Although this study was limited by its small sample, it demonstrated the feasibility of implementing an MI training program for practitioners working in a busy primary care environment. This study offers concrete suggestions for overcoming barriers and enhancing facilitators, which can guide much needed larger studies as they examine MI training effectiveness on patient and clinician outcomes.

Champions and practitioners reported that learning MI was important, but opportunities to practice and receive critical feedback are needed to achieve proficiency and improve confidence. Both champions and study practitioners thought practicing with a standardized patient would enrich their learning. However, dedicated time for learning and practicing MI skills is critical and hard to arrange.

Conclusion

Practitioners can use MI to activate health behavior change in their patients. Training PACT practitioners to use MI is feasible. The results of this evaluation can be used to inform the next iteration of an MI training program for HCPs by highlighting the facilitators of and barriers to training.

Because of the interest in activating patient-centered health behavior change, these findings are important. The educational and practice opportunities were well received. Training with standardized patients and incorporating MI champions into PACTs facilitated training. However, the lack of time was a major barrier to learning and practicing MI skills and will need to be addressed. If effectively implemented, training providers by using an evidence-based approach, such as MI, can promote long-term health.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by VA Health Services Research & Development (HSR&D) Rapid Response Project 11-019. The Center for Chronic Disease Outcomes Research is supported by the VA, VHA, Office of Research and Development, and HSR&D. Dr. Widome was supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award.

Primary care providers (PCPs) need effective tools for activating health behavior change for the 125 million Americans living with a chronic condition.1 Smoking is an important and difficult behavior to change, and a motivator for quitting is tobacco cessation advice from a PCP.2,3 However, few PCPs provide comprehensive tobacco cessation counseling as part of routine care.4,5 One perceived barrier that providers report is their lack of training to be effective tobacco cessation advocates.4,6-8

Motivational interviewing (MI) promotes behavior change by using a nonadversarial approach aimed at resolving patient ambivalence. Motivational interviewing tools, such as asking open-ended questions, providing summary statements of what the patient expresses, reflective listening, and affirmations, are used to spur an intrinsic drive to change. These techniques have been applied to a broad range of health behaviors with positive outcomes and demonstrated efficacy.9-11 Furthermore, MI can be used in primary care for changing tobacco use, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and diet.12-14

Despite its efficacy, MI can be time-intensive to learn. Fortunately, even abbreviated MI can influence patient behavior.15,16 Rollnick and others have developed MI interventions that are deliverable in 5 to 10 minutes.17,18 These brief interventions focus on performing a rapid assessment of patients’ perceived importance and self-efficacy for change.17,18

There is increased interest in training health care professionals (HCPs) in MI, yet there is no consensus on the most effective training approach.19,20 Practitioners with many competing priorities often like to learn new skills through self-study or onetime workshops. Yet evidence suggests that these are not effective methods for gaining MI proficiency. Instead, MI training sessions that offer feedback and coaching are more effective in helping participants retain MI skills over time.21,22

The authors developed and successfully pilot-tested an MI training program called the Motivational Interviewing Smoking Treatment Enhancement Program (MI-STEP) for HCPs. This program was designed to facilitate tobacco cessation care in the VHA primary care patient centered medical home, which VHA calls patient aligned care teams (PACTs).23 The main conclusions of this pilot study have been reported elsewhere.24

The objective of this article is to describe the process evaluation the authors conducted during the MI-STEP study to gain a better understanding of how the implementation of the MI training program could be improved. The authors identified barriers and facilitators from the perspectives of MI champions and PACT practitioners.

Methods

Thirty-four PACT practitioners (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and pharmacists) at 2 VA medical centers were randomly assigned to a high- or moderate-intensity MI training program during the summer of 2012. This training was delivered by “MI champions,” who were recruited from PACTs and who attended a 3-day advanced training class on MI. The training included MI skills practice, group case analysis, various role-play exercises, and didactics adapted from the Rx for Change program.25 The curriculum also addressed tobacco cessation counseling using the national tobacco cessation guideline.2 Each site’s health behavior coordinator (HBC) also was recruited to be an MI champion. The HBCs are typically psychologists who have received prior training in MI as well as facilitator and clinician coaching. At the VA, HBCs are charged with integrating preventive services into care. The participating sites’ institutional review boards approved all study procedures.

MI-STEP Training Program

All 34 practitioners attended a half-day on-site MI training workshop led by the site’s HBC. This training covered the basics of MI and used interactive learning methods such as role-play (Table 1). The study practitioners also received self-study materials, and throughout the study period had access to the MI champions. Practitioners who were randomized to high-intensity MI training also attended 6 supplemental 1-hour “booster sessions” to enhance specific MI skills. The MI champions led 3 of the 1-hour booster sessions with a standard agenda, including patient cases and MI exercises. During the other 3 booster sessions, participants used patient cases to interact with a standardized patient over the telephone, and the MI champions provided feedback and coaching.

Process Evaluation

Six months after the program’s completion, investigators conducted an evaluation of the MI-STEP training program with MI champions and study practitioners. One-hour focus group sessions (2 in Minneapolis; 1 in Denver) were conducted with the MI champions by a co-investigator in Minneapolis and a facilitator in Denver. Notes were taken during the sessions. MI champions were asked about the quality of their training sessions, challenges to getting PACT members to participate in the site training, challenges to teaching MI, and how they felt MI fit within VA health care philosophy.

Ten training study practitioners were randomly selected and stratified based on group intensity assignment, discipline, and site to participate in in-depth interviews. The interviews lasted about 30 minutes, and Minneapolis study investigators conducted in-person interviews with local participants and telephone interviews with Denver participants. The interviews focused on experiences with both high- and moderate-intensity MI training programs, how MI was used in their practice, barriers to implementing MI, impressions of the MI training program, and their interactions with MI champions.

Focus group leaders were experienced interviewers who had not previously interacted with MI champions in the context of this study. Investigators conducting study practitioner interviews were blinded to group assignment. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Study investigators reviewed the focus group notes and interview transcripts, identified themes independently, and then discussed group themes. The most salient themes were selected to inform implementation of a larger scale MI training program.

Results

Nine MI champions participated in the focus groups, and 8 study practitioners from both sites representing all clinical disciplines completed in-depth interviews. Table 2 identifies the characteristics of each population.

MI Champion Focus Group Themes

The champions were asked to discuss all aspects of the program, including their training as champions, role as trainers, attitudes about using MI during patient encounters, and participation in the training program. Themes from the MI champion focus groups were placed in the following categories based on the authors’ analytic approach: training MI champions, training study practitioners, and attitudes about MI.

Training MI champions. The champions identified role-play exercises and receiving feedback as strengths of the training program. The champions also expressed the desire for more hands-on practice, especially in small groups. They wanted additional training on teaching MI and facilitating the booster sessions. The champions wanted an expert to train them on how to give feedback and how to best coach practitioners in their use of MI. Champions expressed a desire to have follow-up training sessions with the standardized patient to help them hone their newly acquired coaching skills.

Training study practitioners. The champions’ key role was to train local practitioners and lead the booster sessions for the high-intensity MI training group. Champions felt ill-prepared to fully cover the training materials during the initial half-day workshop and 6 booster sessions. Champions identified difficulty coordinating schedules with the practitioners and lack of compensation for participation as significant barriers to implementing the booster sessions. Champions felt that using a standardized patient during the booster sessions was a strength of the program and that making the cases more realistic could have further enhanced the program.

Attitudes about MI. Champions from both sites perceived MI to have a positive impact on patient care. However, all champions noted there were challenges in using MI in practice. Champions felt MI takes time, energy, and practice to gain proficiency. The current primary care system is not set up to support the use of MI. The appointment time slots are fixed, and VHA goals and the spirit of MI are not always compatible. VHA performance measures encourage providers to achieve performance targets with each patient, often requiring use of directives for patients on what to do. In contrast, MI encourages the patient to take the lead on goal setting and prioritizing.

Study Practitioner Interview Themes

The practitioners were asked to discuss MI skills training, using MI skills with patients, integrating MI into daily practice, getting other PACT members involved, booster sessions, interactions with champions, and suggestions for improving the MI program. Themes from the study practitioner interviews were grouped into the following categories: MI skills training, using MI skills, integrating MI into practice, and suggestions for improving MI training (Table 3).

MI skills training. Overall, the MI high-intensity participants stated they learned useful skills. They reported asking more questions that are open-ended and were more aware of the patient’s perspective. Practitioners reported that booster sessions provided a way to reinforce, refine, and practice their MI skills. Practitioners reported that having the champion located in their own PACT was critical for connecting with their champion between sessions. Nurses and doctors reported that not having time to meet with champions was a barrier, while pharmacists reported more flexibility.

The moderate-intensity participants reported that the training had less impact. Half the respondents reported that they did not remember much of the MI training and either forgot or did not use the newly learned MI skills.

Using MI skills. Both high- and moderate-intensity participants reported using open-ended questions, reflections, affirmations, motivation scales, and active listening.

Practitioners reported that MI helped them focus on patient-centered care, since MI is collaborative. Even when a session was not successful in leading to behavior change, practitioners felt more satisfied with the quality of the interaction.

Integrating MI into practice. The high- and moderate-intensity practitioners had different perceptions of using MI in daily practice. High-intensity participants thought MI required an initial time investment, but that would be balanced by a decrease in the number of follow-up visits needed and/or delay the time between visits. The moderate-intensity participants were more likely to report struggling with the amount of time MI took.

Suggestions for improving MI training. Practitioners from both training groups offered suggestions for improving MI training. Supervisor buy-in was deemed critical to getting other PACT members involved. Practitioners suggested providing compensation or making training mandatory to help motivate others to participate in MI training. Also, practitioners were ready to expand the MI training beyond smoking cessation to incorporate other diseases and multiple comorbidities.

The moderate-intensity participants suggested more training, practice, follow-up, and feedback. These participants also suggested boosterlike sessions.

Discussion

Champions and study practitioners reported that learning MI skills was useful. The participants felt that MI was consistent with their personal philosophies regarding patient-centered care and that MI had a positive impact on patient care. Practitioners and MI champions offered several insights for improving the delivery of MI training. First, practitioners and champions highlighted how important practice and feedback were to learning MI. Booster sessions, standardized patients, and critical feedback enhanced learning.

Second, champions reported that they wanted more training in how to teach MI. Third, practitioners and champions repeatedly stated that finding the time needed to become proficient in MI was difficult and that using the MI approach with patients took additional time during clinical sessions. However, participants in the high-intensity group reported more satisfaction with the quality of their patient encounters and the freedom to follow up with patients less often.

There were aspects of the environment and MI training program that facilitated the MI learning process. The high-intensity group cited booster session feedback as being reinforcing; the moderate-intensity group expressed a desire to practice their newly acquired skill and felt feedback and coaching would have enhanced their learning. Practitioners and champions reported that using a standardized patient to enhance experiential learning activities was an asset. Standardized patients have been used successfully in other training programs.21

Implementing an MI training program posed a number of challenges. The biggest barrier was lack of time. PACT members found it difficult to attend a half-day MI workshop, practice MI skills, and incorporate MI routinely into daily practice. However, without the investment of time, even basic MI proficiency is unachievable.22

This study highlighted several ways to improve feedback and coaching. First, the authors would expand the MI champion curriculum to include training to provide effective feedback/coaching. Second, the authors would train the standardized patient on how to provide feedback to the MI learner. As implemented, the standardized patient evaluated the learner only on whether the patient felt “heard” by the learner.

Perhaps most critical to the success of an MI training program is institutional support. There needs to be adequate time and space for the training process as well as support for ongoing learning and feedback as MI skills are refined. Furthermore, sufficient time is needed during patients’ appointments to allow for MI-oriented conversations. Time is an important, valuable, and scarce resource that institutions control. Administrators should realize that the up-front investment is likely to provide a downstream return as providers become proficient in MI.

There is an urgent need to find ways to incorporate training into the daily practice of busy HCPs. Although this study was limited by its small sample, it demonstrated the feasibility of implementing an MI training program for practitioners working in a busy primary care environment. This study offers concrete suggestions for overcoming barriers and enhancing facilitators, which can guide much needed larger studies as they examine MI training effectiveness on patient and clinician outcomes.

Champions and practitioners reported that learning MI was important, but opportunities to practice and receive critical feedback are needed to achieve proficiency and improve confidence. Both champions and study practitioners thought practicing with a standardized patient would enrich their learning. However, dedicated time for learning and practicing MI skills is critical and hard to arrange.

Conclusion

Practitioners can use MI to activate health behavior change in their patients. Training PACT practitioners to use MI is feasible. The results of this evaluation can be used to inform the next iteration of an MI training program for HCPs by highlighting the facilitators of and barriers to training.

Because of the interest in activating patient-centered health behavior change, these findings are important. The educational and practice opportunities were well received. Training with standardized patients and incorporating MI champions into PACTs facilitated training. However, the lack of time was a major barrier to learning and practicing MI skills and will need to be addressed. If effectively implemented, training providers by using an evidence-based approach, such as MI, can promote long-term health.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by VA Health Services Research & Development (HSR&D) Rapid Response Project 11-019. The Center for Chronic Disease Outcomes Research is supported by the VA, VHA, Office of Research and Development, and HSR&D. Dr. Widome was supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award.

1. Anderson G, Horvath J. The growing burden of chronic disease in America. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(3):263-270

2. Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008.

3. Park E, Eaton CA, Goldstein MG, et al. The development of a decisional balance measure of physician smoking cessation interventions. Prev Med. 2001;33(4):261-267.

4. Ferketich AK, Khan Y, Wewers ME. Are physicians asking about tobacco use and assisting with cessation? Results from the 2001-2004 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS). Prev Med. 2006;43(6):472-476.

5. Marcy TW, Skelly J, Shiffman RN, Flynn BS. Facilitating adherence to the tobacco use treatment guideline with computer-mediated decision support systems: physician and clinic office manager perspectives. Prev Med. 2005;41(2):479-487.

6. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465.

7. Jaén CR, McIlvain H, Pol L, Phillips RL Jr, Flocke S, Crabtree BF. Tailoring tobacco counseling to the competing demands in the clinical encounter. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(10):859-863.

8. Malte CA, McFall M, Chow B, Beckham JC, Carmody TP, Saxon AJ. Survey of providers' attitudes toward integrating smoking cessation treatment into posttraumatic stress disorder care. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27(1):249-255.

9. Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91-111.

10. Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler BC. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008.

11. Miller WR. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behav Psychother. 1983;11(2):147-172.

12. Brodie DA, Inoue A. Motivational interviewing to promote physical activity for people with chronic heart failure. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50(5):518-527.

13. Perry CK, Rosenfeld AG, Bennett JA, Potempa K. Heart-to-Heart: promoting walking in rural women through motivational interviewing and group support. J Cardiovascular Nurs. 2007;22(4):304-312.

14. West DS, DiLillo V, Bursac Z, Gore SA, Greene PG. Motivational interviewing improves weight loss in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1081-1087.

15. Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Pierce JP, et al. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. JAMA. 1989;261(1):49-55.

16. Lancaster T, Stead L. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;18(4):CD000165.

17. Butler C, Rollnick S, Cohen D, Bachmann M, Russell I, Stott N. Motivational counseling versus brief advice for smokers in general practice: a randomized trial. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(445):611-616.

18. Rollnick S, Heather N, Bell A. Negotiating behaviour change in medical settings: the development of brief motivational interviewing. J Ment Health. 1992;1(1):25-37.

19. Madson MB, Loignon AC, Lane C. Training in motivational interviewing: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(1):101-109.

20. Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1050-1062.

21. Lundahl B, Burke BL. The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: a practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. J Clin Pyschol. 2009;65(11):1232-1245.

22. Miller WR, Moyers TB. Eight stages in Learning motivational interviewing. J Teaching Addict. 2006;5(1):13-15.

23. Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263-e272.

24. Fu S, Roth C, Battaglia CT, et al. Training primary care clinicians in motivational interviewing: a comparison of two models. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(1):61-68.

25. School of Pharmacy & Medicine University of California, San Francisco. Rx for change website. http://rxforchange.ucsf.edu/. Accessed May 25, 2016.

1. Anderson G, Horvath J. The growing burden of chronic disease in America. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(3):263-270

2. Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008.

3. Park E, Eaton CA, Goldstein MG, et al. The development of a decisional balance measure of physician smoking cessation interventions. Prev Med. 2001;33(4):261-267.

4. Ferketich AK, Khan Y, Wewers ME. Are physicians asking about tobacco use and assisting with cessation? Results from the 2001-2004 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS). Prev Med. 2006;43(6):472-476.

5. Marcy TW, Skelly J, Shiffman RN, Flynn BS. Facilitating adherence to the tobacco use treatment guideline with computer-mediated decision support systems: physician and clinic office manager perspectives. Prev Med. 2005;41(2):479-487.

6. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465.

7. Jaén CR, McIlvain H, Pol L, Phillips RL Jr, Flocke S, Crabtree BF. Tailoring tobacco counseling to the competing demands in the clinical encounter. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(10):859-863.

8. Malte CA, McFall M, Chow B, Beckham JC, Carmody TP, Saxon AJ. Survey of providers' attitudes toward integrating smoking cessation treatment into posttraumatic stress disorder care. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27(1):249-255.

9. Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91-111.

10. Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler BC. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008.

11. Miller WR. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behav Psychother. 1983;11(2):147-172.

12. Brodie DA, Inoue A. Motivational interviewing to promote physical activity for people with chronic heart failure. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50(5):518-527.

13. Perry CK, Rosenfeld AG, Bennett JA, Potempa K. Heart-to-Heart: promoting walking in rural women through motivational interviewing and group support. J Cardiovascular Nurs. 2007;22(4):304-312.

14. West DS, DiLillo V, Bursac Z, Gore SA, Greene PG. Motivational interviewing improves weight loss in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1081-1087.

15. Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Pierce JP, et al. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. JAMA. 1989;261(1):49-55.

16. Lancaster T, Stead L. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;18(4):CD000165.

17. Butler C, Rollnick S, Cohen D, Bachmann M, Russell I, Stott N. Motivational counseling versus brief advice for smokers in general practice: a randomized trial. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(445):611-616.

18. Rollnick S, Heather N, Bell A. Negotiating behaviour change in medical settings: the development of brief motivational interviewing. J Ment Health. 1992;1(1):25-37.

19. Madson MB, Loignon AC, Lane C. Training in motivational interviewing: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(1):101-109.

20. Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1050-1062.

21. Lundahl B, Burke BL. The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: a practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. J Clin Pyschol. 2009;65(11):1232-1245.

22. Miller WR, Moyers TB. Eight stages in Learning motivational interviewing. J Teaching Addict. 2006;5(1):13-15.

23. Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263-e272.

24. Fu S, Roth C, Battaglia CT, et al. Training primary care clinicians in motivational interviewing: a comparison of two models. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(1):61-68.

25. School of Pharmacy & Medicine University of California, San Francisco. Rx for change website. http://rxforchange.ucsf.edu/. Accessed May 25, 2016.