User login

Obama addresses health exchange website woes

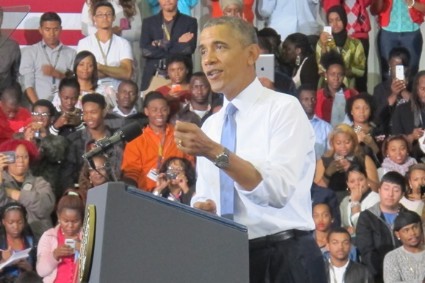

President Obama acknowledged that ongoing problems with the healthcare.gov website – the health insurance exchange for Americans in most states – were giving consumers pause, making supporters nervous, and helping adversaries discredit the Affordable Care Act.

"There’s no sugarcoating it. The website has been too slow," President Obama said during an Oct. 21 White House speech. He said that consumers were having trouble logging on to the website and have gotten bogged down during the application process.

"Nobody’s more frustrated by that than I am," he said, adding that "I want the cash registers to work; I want the checkout lines to be smooth. So I want people to be able to get this great product."

That product, according to the president, is high-quality health insurance that’s offered at a good price.

He said there has been "massive demand," citing nearly 20 million visitors to healthcare.gov. Thirty-four states are directing their residents to buy coverage through that federal website. The president also said there was a lot of demand for plans offered through the exchanges being run by 16 states and the District of Columbia.

Overall, half a million consumers have submitted applications through the federal and state websites, President Obama said. "People don’t just want it; they’re showing up to buy it," he said.

For consumers who have difficulty in accessing the website, President Obama referred them to a toll-free phone number, 800-318-2596. He also said that people could apply in-person at various locations.

"Nobody’s madder than me about the fact that the website isn’t working as well as it should, which means it’s going to get fixed," he said.

On Oct. 20, Health and Human Services department officials said that some of those fixes were underway. The site has been sluggish because "the initial wave of interest stressed the account service," according to HHS officials. But they said that the "data hub" was working, meaning that consumers would be told if they were eligible for subsidies. They also noted that the agency is bringing in technical help to fix the website – something President Obama repeated in his speech.

But the president also said he was frustrated that there was so much focus on the website, given that it was only 3 weeks into a 6-month enrollment process, and that many of the ACA’s benefits were already in place.

He addressed what he called "some of the politics that have swirled around the Affordable Care Act," noting Republican efforts to defund or repeal the ACA.

"And I’m sure that, given the problems with the website so far, they’re going to be looking to go after it even harder," he said.

But, he said, "We did not wage this long and contentious battle just around a website." The battle was "to make sure that millions of Americans in the wealthiest nation on Earth finally have the same chance to get the same security of affordable quality health care as anybody else."

Speaker of the House John Boehner (R-Ohio) was not impressed. "If the president is frustrated by the mounting failures of his health care law, it wasn’t apparent today," said Rep. Boehner, in a statement. "Instead of answers, we got well-worn talking points. Instead of explanations, we got excuses."

He added that "the House’s oversight of this failure is just beginning."

On Oct. 24, the House Energy and Commerce Committee will hold the first of what is likely to be many hearings on the website rollout. HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius was invited to testify, but declined because of a scheduling conflict.

Rep. Boehner said that "Secretary Sebelius must change her mind and appear at this week’s hearing."

On Twitter @aliciaault

*This story was updated 10/22/13.

President Obama acknowledged that ongoing problems with the healthcare.gov website – the health insurance exchange for Americans in most states – were giving consumers pause, making supporters nervous, and helping adversaries discredit the Affordable Care Act.

"There’s no sugarcoating it. The website has been too slow," President Obama said during an Oct. 21 White House speech. He said that consumers were having trouble logging on to the website and have gotten bogged down during the application process.

"Nobody’s more frustrated by that than I am," he said, adding that "I want the cash registers to work; I want the checkout lines to be smooth. So I want people to be able to get this great product."

That product, according to the president, is high-quality health insurance that’s offered at a good price.

He said there has been "massive demand," citing nearly 20 million visitors to healthcare.gov. Thirty-four states are directing their residents to buy coverage through that federal website. The president also said there was a lot of demand for plans offered through the exchanges being run by 16 states and the District of Columbia.

Overall, half a million consumers have submitted applications through the federal and state websites, President Obama said. "People don’t just want it; they’re showing up to buy it," he said.

For consumers who have difficulty in accessing the website, President Obama referred them to a toll-free phone number, 800-318-2596. He also said that people could apply in-person at various locations.

"Nobody’s madder than me about the fact that the website isn’t working as well as it should, which means it’s going to get fixed," he said.

On Oct. 20, Health and Human Services department officials said that some of those fixes were underway. The site has been sluggish because "the initial wave of interest stressed the account service," according to HHS officials. But they said that the "data hub" was working, meaning that consumers would be told if they were eligible for subsidies. They also noted that the agency is bringing in technical help to fix the website – something President Obama repeated in his speech.

But the president also said he was frustrated that there was so much focus on the website, given that it was only 3 weeks into a 6-month enrollment process, and that many of the ACA’s benefits were already in place.

He addressed what he called "some of the politics that have swirled around the Affordable Care Act," noting Republican efforts to defund or repeal the ACA.

"And I’m sure that, given the problems with the website so far, they’re going to be looking to go after it even harder," he said.

But, he said, "We did not wage this long and contentious battle just around a website." The battle was "to make sure that millions of Americans in the wealthiest nation on Earth finally have the same chance to get the same security of affordable quality health care as anybody else."

Speaker of the House John Boehner (R-Ohio) was not impressed. "If the president is frustrated by the mounting failures of his health care law, it wasn’t apparent today," said Rep. Boehner, in a statement. "Instead of answers, we got well-worn talking points. Instead of explanations, we got excuses."

He added that "the House’s oversight of this failure is just beginning."

On Oct. 24, the House Energy and Commerce Committee will hold the first of what is likely to be many hearings on the website rollout. HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius was invited to testify, but declined because of a scheduling conflict.

Rep. Boehner said that "Secretary Sebelius must change her mind and appear at this week’s hearing."

On Twitter @aliciaault

*This story was updated 10/22/13.

President Obama acknowledged that ongoing problems with the healthcare.gov website – the health insurance exchange for Americans in most states – were giving consumers pause, making supporters nervous, and helping adversaries discredit the Affordable Care Act.

"There’s no sugarcoating it. The website has been too slow," President Obama said during an Oct. 21 White House speech. He said that consumers were having trouble logging on to the website and have gotten bogged down during the application process.

"Nobody’s more frustrated by that than I am," he said, adding that "I want the cash registers to work; I want the checkout lines to be smooth. So I want people to be able to get this great product."

That product, according to the president, is high-quality health insurance that’s offered at a good price.

He said there has been "massive demand," citing nearly 20 million visitors to healthcare.gov. Thirty-four states are directing their residents to buy coverage through that federal website. The president also said there was a lot of demand for plans offered through the exchanges being run by 16 states and the District of Columbia.

Overall, half a million consumers have submitted applications through the federal and state websites, President Obama said. "People don’t just want it; they’re showing up to buy it," he said.

For consumers who have difficulty in accessing the website, President Obama referred them to a toll-free phone number, 800-318-2596. He also said that people could apply in-person at various locations.

"Nobody’s madder than me about the fact that the website isn’t working as well as it should, which means it’s going to get fixed," he said.

On Oct. 20, Health and Human Services department officials said that some of those fixes were underway. The site has been sluggish because "the initial wave of interest stressed the account service," according to HHS officials. But they said that the "data hub" was working, meaning that consumers would be told if they were eligible for subsidies. They also noted that the agency is bringing in technical help to fix the website – something President Obama repeated in his speech.

But the president also said he was frustrated that there was so much focus on the website, given that it was only 3 weeks into a 6-month enrollment process, and that many of the ACA’s benefits were already in place.

He addressed what he called "some of the politics that have swirled around the Affordable Care Act," noting Republican efforts to defund or repeal the ACA.

"And I’m sure that, given the problems with the website so far, they’re going to be looking to go after it even harder," he said.

But, he said, "We did not wage this long and contentious battle just around a website." The battle was "to make sure that millions of Americans in the wealthiest nation on Earth finally have the same chance to get the same security of affordable quality health care as anybody else."

Speaker of the House John Boehner (R-Ohio) was not impressed. "If the president is frustrated by the mounting failures of his health care law, it wasn’t apparent today," said Rep. Boehner, in a statement. "Instead of answers, we got well-worn talking points. Instead of explanations, we got excuses."

He added that "the House’s oversight of this failure is just beginning."

On Oct. 24, the House Energy and Commerce Committee will hold the first of what is likely to be many hearings on the website rollout. HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius was invited to testify, but declined because of a scheduling conflict.

Rep. Boehner said that "Secretary Sebelius must change her mind and appear at this week’s hearing."

On Twitter @aliciaault

*This story was updated 10/22/13.

Patrick Kennedy urges psychiatry to embrace the ACA’s potential

PHILADELPHIA – Former congressman Patrick Kennedy says that psychiatrists have a unique opportunity to advance their profession and assume a more active role in the health care system now that the Affordable Care Act is underway.

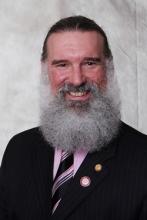

"With health care reform, we’re rewriting the rule book on what health care means," said Mr. Kennedy, at the American Psychiatric Association’s annual institute on psychiatric services. Mr. Kennedy was interviewed by APA President Jeffrey Lieberman.

"Now, mental health is going to be an essential health benefit," Mr. Kennedy added. That means psychiatrists need to step up and say what they think needs to be included and what should be reimbursed, he said.

"We need your thinking now. Giving it to us 5 years from now is going to be a lost cause," said Mr. Kennedy, a former Democratic House member from Rhode Island who has been very public about his struggles with bipolar disorder and substance abuse.

Mr. Kennedy urged psychiatrists to push for an end to what he called the "silos" between intellectual disabilities and mental health disorders, noting that many of the services required were similar.

Dr. Lieberman agreed, saying that "this artificial separation between intellectual disabilities, mental disorders, substance use, and addiction" should end, but that it was up to psychiatry to tell policy makers how best to do that.

He asked Mr. Kennedy his opinion of some of the key policy challenges for psychiatry, especially under the new health law.

For one, psychiatrists should focus more on adequately diagnosing patients from a medical standpoint – that is, assessing their coexisting conditions and helping to integrate medical and psychiatric care, Mr. Kennedy said. This will help generate bottom line savings for accountable care organizations and, in turn, validate the profession’s value, he said.

"You all have the key to treating cancer better," he said. "You all have the key to treating diabetes and cardiovascular disease better. And no one’s ever thought of calling you!"

As it stands in most of the health system, the rest of the medical profession does not have adequate training in psychiatry and does not know how to reach out to psychiatrists, he said. "Insurance companies ought to know that by paying for the kind of value added that you bring, they’ll get value added to their bottom lines," said Mr. Kennedy, adding that many chronic conditions are "driven by untreated mental illness."

He also reminded psychiatrists that they need to keep campaigning for parity between physical and mental health when it comes to coverage and reimbursement, even though it is the law. Everyone in the mental health field should band together to make sure parity becomes reality, he said.

Dr. Lieberman agreed, saying, "We have to demonstrate some leadership." He said that the APA could be the lead organization bringing others together.

"This is a moment in history where we have a chance to change the landscape," Dr. Lieberman said.

On Twitter @aliciaault

PHILADELPHIA – Former congressman Patrick Kennedy says that psychiatrists have a unique opportunity to advance their profession and assume a more active role in the health care system now that the Affordable Care Act is underway.

"With health care reform, we’re rewriting the rule book on what health care means," said Mr. Kennedy, at the American Psychiatric Association’s annual institute on psychiatric services. Mr. Kennedy was interviewed by APA President Jeffrey Lieberman.

"Now, mental health is going to be an essential health benefit," Mr. Kennedy added. That means psychiatrists need to step up and say what they think needs to be included and what should be reimbursed, he said.

"We need your thinking now. Giving it to us 5 years from now is going to be a lost cause," said Mr. Kennedy, a former Democratic House member from Rhode Island who has been very public about his struggles with bipolar disorder and substance abuse.

Mr. Kennedy urged psychiatrists to push for an end to what he called the "silos" between intellectual disabilities and mental health disorders, noting that many of the services required were similar.

Dr. Lieberman agreed, saying that "this artificial separation between intellectual disabilities, mental disorders, substance use, and addiction" should end, but that it was up to psychiatry to tell policy makers how best to do that.

He asked Mr. Kennedy his opinion of some of the key policy challenges for psychiatry, especially under the new health law.

For one, psychiatrists should focus more on adequately diagnosing patients from a medical standpoint – that is, assessing their coexisting conditions and helping to integrate medical and psychiatric care, Mr. Kennedy said. This will help generate bottom line savings for accountable care organizations and, in turn, validate the profession’s value, he said.

"You all have the key to treating cancer better," he said. "You all have the key to treating diabetes and cardiovascular disease better. And no one’s ever thought of calling you!"

As it stands in most of the health system, the rest of the medical profession does not have adequate training in psychiatry and does not know how to reach out to psychiatrists, he said. "Insurance companies ought to know that by paying for the kind of value added that you bring, they’ll get value added to their bottom lines," said Mr. Kennedy, adding that many chronic conditions are "driven by untreated mental illness."

He also reminded psychiatrists that they need to keep campaigning for parity between physical and mental health when it comes to coverage and reimbursement, even though it is the law. Everyone in the mental health field should band together to make sure parity becomes reality, he said.

Dr. Lieberman agreed, saying, "We have to demonstrate some leadership." He said that the APA could be the lead organization bringing others together.

"This is a moment in history where we have a chance to change the landscape," Dr. Lieberman said.

On Twitter @aliciaault

PHILADELPHIA – Former congressman Patrick Kennedy says that psychiatrists have a unique opportunity to advance their profession and assume a more active role in the health care system now that the Affordable Care Act is underway.

"With health care reform, we’re rewriting the rule book on what health care means," said Mr. Kennedy, at the American Psychiatric Association’s annual institute on psychiatric services. Mr. Kennedy was interviewed by APA President Jeffrey Lieberman.

"Now, mental health is going to be an essential health benefit," Mr. Kennedy added. That means psychiatrists need to step up and say what they think needs to be included and what should be reimbursed, he said.

"We need your thinking now. Giving it to us 5 years from now is going to be a lost cause," said Mr. Kennedy, a former Democratic House member from Rhode Island who has been very public about his struggles with bipolar disorder and substance abuse.

Mr. Kennedy urged psychiatrists to push for an end to what he called the "silos" between intellectual disabilities and mental health disorders, noting that many of the services required were similar.

Dr. Lieberman agreed, saying that "this artificial separation between intellectual disabilities, mental disorders, substance use, and addiction" should end, but that it was up to psychiatry to tell policy makers how best to do that.

He asked Mr. Kennedy his opinion of some of the key policy challenges for psychiatry, especially under the new health law.

For one, psychiatrists should focus more on adequately diagnosing patients from a medical standpoint – that is, assessing their coexisting conditions and helping to integrate medical and psychiatric care, Mr. Kennedy said. This will help generate bottom line savings for accountable care organizations and, in turn, validate the profession’s value, he said.

"You all have the key to treating cancer better," he said. "You all have the key to treating diabetes and cardiovascular disease better. And no one’s ever thought of calling you!"

As it stands in most of the health system, the rest of the medical profession does not have adequate training in psychiatry and does not know how to reach out to psychiatrists, he said. "Insurance companies ought to know that by paying for the kind of value added that you bring, they’ll get value added to their bottom lines," said Mr. Kennedy, adding that many chronic conditions are "driven by untreated mental illness."

He also reminded psychiatrists that they need to keep campaigning for parity between physical and mental health when it comes to coverage and reimbursement, even though it is the law. Everyone in the mental health field should band together to make sure parity becomes reality, he said.

Dr. Lieberman agreed, saying, "We have to demonstrate some leadership." He said that the APA could be the lead organization bringing others together.

"This is a moment in history where we have a chance to change the landscape," Dr. Lieberman said.

On Twitter @aliciaault

AT THE APA INSTITUTE ON PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES

What you need to know about health insurance exchanges

As the state and federal health insurance exchanges get up and running, physicians will face questions from patients about eligibility, enrollment, and how the marketplaces work.

The dizzying array of plans, costs, subsidies, and more could easily overwhelm even those who have been closely following the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, which established the exchanges.

Physicians don’t have to go it alone. Several organizations – including the American Medical Association, the American College of Physicians, and the American Academy of Family Physicians – have set up websites to help doctors help their patients through the open enrollment period (Oct. 1, 2013, to March 31, 2014).

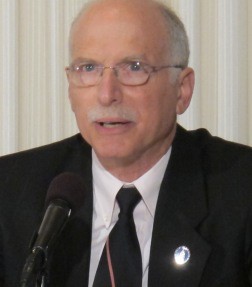

"We’re going to give facts, figures, and information to doctors so they have it in their offices, to help them and their staff navigate this period of time," Dr. Ardis Dee Hoven, AMA president, said in an interview.

Dr. Reid Blackwelder, president of the AAFP, agreed that physicians did not have to be the only ones helping patients. Family physicians, in particular, "often feel we’re supposed to have the answer for everything, and that’s not really possible," he said in an interview.

Knowing about the exchanges, whether one agrees with the premise of the ACA or not, is important to patient care, Dr. Blackwelder said. "Even if physicians are not happy with [the law], they need to help patients recognize this is an option available to them to help them with their health care costs."

Dr. Charles Cutler, chairman of the ACP Board of Regents, said, "personally, this is a conversation I want to have with the patient." He said that a physician is most knowledgeable about that patient’s medical needs and can help guide what kind of coverage to choose.

There will be much to navigate. To a large extent, what doctors tell patients about the exchanges will depend on where they practice.

Each state has chosen its own pathway for an exchange as well as whether it will expand Medicaid eligibility, which impacts how, and how many, patients will receive coverage.

Under the ACA, Medicaid coverage is available to all Americans who earn up to 133% of the federal poverty level ($14,856 for an individual and $30,657 for a family of four). Twenty-four states have said they will make Medicaid available at that level or higher, 21 won’t expand, and 5 are uncommitted.

That means a lot of people will make too little to buy coverage on an exchange and too much to get Medicaid. According to a recent study by the Commonwealth Fund, in states that aren’t expanding, about 42% of adults who were uninsured for any time over the past 2 years won’t have access to new coverage.

At press time, 16 states and the District of Columbia had created their own exchanges, 26 states were letting the federal government run the exchange, and 7 states were operating partnership with the feds. In Utah, the state has opened an exchange for small businesses, but the federal government runs the exchange for individuals.

There are a lot of questions about how many patients will enroll through exchanges and how diligently they will stick with the new insurance plans.

*In the first week the exchanges were open, some 8 million people visited the federal exchanges' healthcare.gov website. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) was not able to say how many of them had actually applied for insurance coverage. The number of hits and applications on the state exchange sites varied, but in most states, the initial amount of traffic was massive.

Families USA has estimated that as many as 26 million Americans who make between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level (between $24,000 and $94,000 for a family of four) will be eligible for tax credits to buy insurance.

Although individuals will be required to have health insurance beginning in January, some will choose not to. Those who opt out in 2014 will pay a penalty to the federal government with their 2015 tax return. The penalty will be either 1% of their income or $95, whichever is higher. By 2016, that amount rises to 2.5% of income or $695 per person, with exceptions for low-income individuals.

The government is also cutting enrollees a break on premium payments. As long as they have paid at least one premium, they’ll have a 90-day grace period to pay the next one. If they don’t pay, the insurer can drop the patient from the plan. But, if they’ve received services during that 90-day period, the insurer is not obligated to pay. That doesn't sit well with many physicians.

"It makes no sense at all – the patient is protected but the rest of the system isn’t and that’s not how it’s supposed to work," the AMA’s Dr. Hoven said.

Much remains to be seen with how the exchanges work, including what kind of clout they will have in negotiating with physicians. Many predict that the exchanges will grow as forces to be reckoned with in the insurance market.

Eventually, they will be able to set quality standards, bar plans that don’t meet certain standards, and limit the sale of insurance outside exchanges, according to Henry Aaron of the Brookings Institution and Kevin W. Lucia of Georgetown University (N. Engl. J. Med. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1308032).

Vermont and Washington, D.C., already prohibit sales of individual policies outside their exchanges.

The insurance exchanges also are expected to expand their reach. They will start offering plans to employers with 51 to 100 workers in 2016, and could be adding larger employers in 2017. Over time, "we believe that the exchanges will be seen as a means for promoting a competitive insurance market in which consumers can make rational decisions, and that they will become an instrument that can reshape the health care delivery system," wrote Mr. Aaron and Mr. Lucia.

Exchanges will vary from state to state

*The Commonwealth Fund has mapped it out, with links to each state's exchange website, details on how each exchange is governed, who serves on the board of directors, and whether and when quality data have to be reported.

*Not every insurer in every state is participating. In some states, only one insurer is offering plans. A list of every insurer and all the plans being offered in every state can be found at The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. There is also information on insurers participating in the federally-run exchanges at www.healthcare.gov.

Each state exchange is using different ways to get patients enrolled. For the most part, physicians are not being asked to get involved personally; however, the department of Health and Human Services has enlisted physician organizations – such as the AMA, the AAFP, the ACP, and the American Academy of Pediatrics – as "Champions for Coverage," to help spread the word.

Plans offered through the exchanges will have to cover a set of essential benefits. All Medicaid plans have to cover those services as well.

Exchange plans can’t deny coverage or charge higher premiums for preexisting conditions, and premiums can’t be different for men and women. Insurers can still charge more as people age, except in Vermont and New York, which prohibit age-rating by state law.

Plans will be able to offer five levels of coverage, ranging from the least protective and least expensive to the most protective and most expensive: catastrophic, bronze, silver, gold, and platinum. Not every state requires that every level of coverage be offered.

Premiums will be based on income and age. An individual with an income below $45,960 and a family of four with an income below $94,200 will be eligible for some kind of assistance. Tax credits are given directly to the insurance company so that the enrollee doesn’t have to pay the higher premium up front. Out-of-pocket costs will also be limited, depending on income.

The Kaiser Family Foundation has estimated that older Americans, those between 60-65 years, are likely to benefit the most from subsidies.

On Twitter @aliciaault

*Updated 10/9/13

As the state and federal health insurance exchanges get up and running, physicians will face questions from patients about eligibility, enrollment, and how the marketplaces work.

The dizzying array of plans, costs, subsidies, and more could easily overwhelm even those who have been closely following the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, which established the exchanges.

Physicians don’t have to go it alone. Several organizations – including the American Medical Association, the American College of Physicians, and the American Academy of Family Physicians – have set up websites to help doctors help their patients through the open enrollment period (Oct. 1, 2013, to March 31, 2014).

"We’re going to give facts, figures, and information to doctors so they have it in their offices, to help them and their staff navigate this period of time," Dr. Ardis Dee Hoven, AMA president, said in an interview.

Dr. Reid Blackwelder, president of the AAFP, agreed that physicians did not have to be the only ones helping patients. Family physicians, in particular, "often feel we’re supposed to have the answer for everything, and that’s not really possible," he said in an interview.

Knowing about the exchanges, whether one agrees with the premise of the ACA or not, is important to patient care, Dr. Blackwelder said. "Even if physicians are not happy with [the law], they need to help patients recognize this is an option available to them to help them with their health care costs."

Dr. Charles Cutler, chairman of the ACP Board of Regents, said, "personally, this is a conversation I want to have with the patient." He said that a physician is most knowledgeable about that patient’s medical needs and can help guide what kind of coverage to choose.

There will be much to navigate. To a large extent, what doctors tell patients about the exchanges will depend on where they practice.

Each state has chosen its own pathway for an exchange as well as whether it will expand Medicaid eligibility, which impacts how, and how many, patients will receive coverage.

Under the ACA, Medicaid coverage is available to all Americans who earn up to 133% of the federal poverty level ($14,856 for an individual and $30,657 for a family of four). Twenty-four states have said they will make Medicaid available at that level or higher, 21 won’t expand, and 5 are uncommitted.

That means a lot of people will make too little to buy coverage on an exchange and too much to get Medicaid. According to a recent study by the Commonwealth Fund, in states that aren’t expanding, about 42% of adults who were uninsured for any time over the past 2 years won’t have access to new coverage.

At press time, 16 states and the District of Columbia had created their own exchanges, 26 states were letting the federal government run the exchange, and 7 states were operating partnership with the feds. In Utah, the state has opened an exchange for small businesses, but the federal government runs the exchange for individuals.

There are a lot of questions about how many patients will enroll through exchanges and how diligently they will stick with the new insurance plans.

*In the first week the exchanges were open, some 8 million people visited the federal exchanges' healthcare.gov website. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) was not able to say how many of them had actually applied for insurance coverage. The number of hits and applications on the state exchange sites varied, but in most states, the initial amount of traffic was massive.

Families USA has estimated that as many as 26 million Americans who make between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level (between $24,000 and $94,000 for a family of four) will be eligible for tax credits to buy insurance.

Although individuals will be required to have health insurance beginning in January, some will choose not to. Those who opt out in 2014 will pay a penalty to the federal government with their 2015 tax return. The penalty will be either 1% of their income or $95, whichever is higher. By 2016, that amount rises to 2.5% of income or $695 per person, with exceptions for low-income individuals.

The government is also cutting enrollees a break on premium payments. As long as they have paid at least one premium, they’ll have a 90-day grace period to pay the next one. If they don’t pay, the insurer can drop the patient from the plan. But, if they’ve received services during that 90-day period, the insurer is not obligated to pay. That doesn't sit well with many physicians.

"It makes no sense at all – the patient is protected but the rest of the system isn’t and that’s not how it’s supposed to work," the AMA’s Dr. Hoven said.

Much remains to be seen with how the exchanges work, including what kind of clout they will have in negotiating with physicians. Many predict that the exchanges will grow as forces to be reckoned with in the insurance market.

Eventually, they will be able to set quality standards, bar plans that don’t meet certain standards, and limit the sale of insurance outside exchanges, according to Henry Aaron of the Brookings Institution and Kevin W. Lucia of Georgetown University (N. Engl. J. Med. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1308032).

Vermont and Washington, D.C., already prohibit sales of individual policies outside their exchanges.

The insurance exchanges also are expected to expand their reach. They will start offering plans to employers with 51 to 100 workers in 2016, and could be adding larger employers in 2017. Over time, "we believe that the exchanges will be seen as a means for promoting a competitive insurance market in which consumers can make rational decisions, and that they will become an instrument that can reshape the health care delivery system," wrote Mr. Aaron and Mr. Lucia.

Exchanges will vary from state to state

*The Commonwealth Fund has mapped it out, with links to each state's exchange website, details on how each exchange is governed, who serves on the board of directors, and whether and when quality data have to be reported.

*Not every insurer in every state is participating. In some states, only one insurer is offering plans. A list of every insurer and all the plans being offered in every state can be found at The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. There is also information on insurers participating in the federally-run exchanges at www.healthcare.gov.

Each state exchange is using different ways to get patients enrolled. For the most part, physicians are not being asked to get involved personally; however, the department of Health and Human Services has enlisted physician organizations – such as the AMA, the AAFP, the ACP, and the American Academy of Pediatrics – as "Champions for Coverage," to help spread the word.

Plans offered through the exchanges will have to cover a set of essential benefits. All Medicaid plans have to cover those services as well.

Exchange plans can’t deny coverage or charge higher premiums for preexisting conditions, and premiums can’t be different for men and women. Insurers can still charge more as people age, except in Vermont and New York, which prohibit age-rating by state law.

Plans will be able to offer five levels of coverage, ranging from the least protective and least expensive to the most protective and most expensive: catastrophic, bronze, silver, gold, and platinum. Not every state requires that every level of coverage be offered.

Premiums will be based on income and age. An individual with an income below $45,960 and a family of four with an income below $94,200 will be eligible for some kind of assistance. Tax credits are given directly to the insurance company so that the enrollee doesn’t have to pay the higher premium up front. Out-of-pocket costs will also be limited, depending on income.

The Kaiser Family Foundation has estimated that older Americans, those between 60-65 years, are likely to benefit the most from subsidies.

On Twitter @aliciaault

*Updated 10/9/13

As the state and federal health insurance exchanges get up and running, physicians will face questions from patients about eligibility, enrollment, and how the marketplaces work.

The dizzying array of plans, costs, subsidies, and more could easily overwhelm even those who have been closely following the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, which established the exchanges.

Physicians don’t have to go it alone. Several organizations – including the American Medical Association, the American College of Physicians, and the American Academy of Family Physicians – have set up websites to help doctors help their patients through the open enrollment period (Oct. 1, 2013, to March 31, 2014).

"We’re going to give facts, figures, and information to doctors so they have it in their offices, to help them and their staff navigate this period of time," Dr. Ardis Dee Hoven, AMA president, said in an interview.

Dr. Reid Blackwelder, president of the AAFP, agreed that physicians did not have to be the only ones helping patients. Family physicians, in particular, "often feel we’re supposed to have the answer for everything, and that’s not really possible," he said in an interview.

Knowing about the exchanges, whether one agrees with the premise of the ACA or not, is important to patient care, Dr. Blackwelder said. "Even if physicians are not happy with [the law], they need to help patients recognize this is an option available to them to help them with their health care costs."

Dr. Charles Cutler, chairman of the ACP Board of Regents, said, "personally, this is a conversation I want to have with the patient." He said that a physician is most knowledgeable about that patient’s medical needs and can help guide what kind of coverage to choose.

There will be much to navigate. To a large extent, what doctors tell patients about the exchanges will depend on where they practice.

Each state has chosen its own pathway for an exchange as well as whether it will expand Medicaid eligibility, which impacts how, and how many, patients will receive coverage.

Under the ACA, Medicaid coverage is available to all Americans who earn up to 133% of the federal poverty level ($14,856 for an individual and $30,657 for a family of four). Twenty-four states have said they will make Medicaid available at that level or higher, 21 won’t expand, and 5 are uncommitted.

That means a lot of people will make too little to buy coverage on an exchange and too much to get Medicaid. According to a recent study by the Commonwealth Fund, in states that aren’t expanding, about 42% of adults who were uninsured for any time over the past 2 years won’t have access to new coverage.

At press time, 16 states and the District of Columbia had created their own exchanges, 26 states were letting the federal government run the exchange, and 7 states were operating partnership with the feds. In Utah, the state has opened an exchange for small businesses, but the federal government runs the exchange for individuals.

There are a lot of questions about how many patients will enroll through exchanges and how diligently they will stick with the new insurance plans.

*In the first week the exchanges were open, some 8 million people visited the federal exchanges' healthcare.gov website. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) was not able to say how many of them had actually applied for insurance coverage. The number of hits and applications on the state exchange sites varied, but in most states, the initial amount of traffic was massive.

Families USA has estimated that as many as 26 million Americans who make between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level (between $24,000 and $94,000 for a family of four) will be eligible for tax credits to buy insurance.

Although individuals will be required to have health insurance beginning in January, some will choose not to. Those who opt out in 2014 will pay a penalty to the federal government with their 2015 tax return. The penalty will be either 1% of their income or $95, whichever is higher. By 2016, that amount rises to 2.5% of income or $695 per person, with exceptions for low-income individuals.

The government is also cutting enrollees a break on premium payments. As long as they have paid at least one premium, they’ll have a 90-day grace period to pay the next one. If they don’t pay, the insurer can drop the patient from the plan. But, if they’ve received services during that 90-day period, the insurer is not obligated to pay. That doesn't sit well with many physicians.

"It makes no sense at all – the patient is protected but the rest of the system isn’t and that’s not how it’s supposed to work," the AMA’s Dr. Hoven said.

Much remains to be seen with how the exchanges work, including what kind of clout they will have in negotiating with physicians. Many predict that the exchanges will grow as forces to be reckoned with in the insurance market.

Eventually, they will be able to set quality standards, bar plans that don’t meet certain standards, and limit the sale of insurance outside exchanges, according to Henry Aaron of the Brookings Institution and Kevin W. Lucia of Georgetown University (N. Engl. J. Med. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1308032).

Vermont and Washington, D.C., already prohibit sales of individual policies outside their exchanges.

The insurance exchanges also are expected to expand their reach. They will start offering plans to employers with 51 to 100 workers in 2016, and could be adding larger employers in 2017. Over time, "we believe that the exchanges will be seen as a means for promoting a competitive insurance market in which consumers can make rational decisions, and that they will become an instrument that can reshape the health care delivery system," wrote Mr. Aaron and Mr. Lucia.

Exchanges will vary from state to state

*The Commonwealth Fund has mapped it out, with links to each state's exchange website, details on how each exchange is governed, who serves on the board of directors, and whether and when quality data have to be reported.

*Not every insurer in every state is participating. In some states, only one insurer is offering plans. A list of every insurer and all the plans being offered in every state can be found at The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. There is also information on insurers participating in the federally-run exchanges at www.healthcare.gov.

Each state exchange is using different ways to get patients enrolled. For the most part, physicians are not being asked to get involved personally; however, the department of Health and Human Services has enlisted physician organizations – such as the AMA, the AAFP, the ACP, and the American Academy of Pediatrics – as "Champions for Coverage," to help spread the word.

Plans offered through the exchanges will have to cover a set of essential benefits. All Medicaid plans have to cover those services as well.

Exchange plans can’t deny coverage or charge higher premiums for preexisting conditions, and premiums can’t be different for men and women. Insurers can still charge more as people age, except in Vermont and New York, which prohibit age-rating by state law.

Plans will be able to offer five levels of coverage, ranging from the least protective and least expensive to the most protective and most expensive: catastrophic, bronze, silver, gold, and platinum. Not every state requires that every level of coverage be offered.

Premiums will be based on income and age. An individual with an income below $45,960 and a family of four with an income below $94,200 will be eligible for some kind of assistance. Tax credits are given directly to the insurance company so that the enrollee doesn’t have to pay the higher premium up front. Out-of-pocket costs will also be limited, depending on income.

The Kaiser Family Foundation has estimated that older Americans, those between 60-65 years, are likely to benefit the most from subsidies.

On Twitter @aliciaault

*Updated 10/9/13

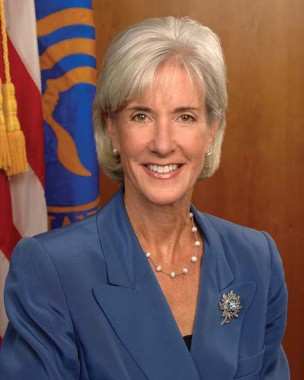

Sebelius: Shutdown, sequester bad for medical research

WASHINGTON – A government shutdown will compound the negative effects that sequestration is already having on U.S. researchers’ ability to discover new therapeutics and advance knowledge in oncology and other fields, according to Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius.

Speaking Sept. 30 at the Association of American Cancer Institutes annual meeting, Ms. Sebelius said it looked increasingly likely that Congress would fail to reach a federal budget agreement and that the government would be shut down Oct. 1.

With a shutdown, "entrance to new [federally funded] clinical trials will stop right away," she said.

In the meantime, biomedical research continues to be diminished by the ongoing automatic budget cuts known as sequestration, she said. In March, Congress’ failure to come to an agreement on deficit reduction triggered an across-the-board cut at most federal agencies.

For the National Institutes of Health, that resulted in a 5% reduction to its $30 billion budget. Dr. Harold Varmus, director of the National Cancer Institute, said in May that his agency’s budget would by reduced by almost 6%, or $293 million. Most of the reduction was due to sequestration. The NCI expected to fund about 100 fewer new and competing grants than in the previous year (fiscal 2012).

Ms. Sebelius said that, at NIH overall, sequestration has resulted in 640 fewer grants being awarded in fiscal 2013 as compared to fiscal 2012. And it also has meant that there are "hundreds more projects we’ll be unable to advance in the year ahead." About 750 fewer patients were enrolled in clinical trials.

"When as a country, we neglect to invest in the NIH – the gold standard for research in the world – we pay for that neglect," she said. She added that slashing research funding hurts the nation’s global competitiveness at a time when other countries, such as India, China, South Korea, Brazil, and Japan are increasing their investment in biomedical research.

Many physician organizations and others have urged Congress to rescind the NIH budget cuts.

Oncology organizations have urged their members to support the Cancer Patient Protection Act of 2013 (H.R. 1416), which would eliminate sequestration cuts for physician-administered Medicare Part B drugs. At press time, the bill had 108 cosponsors. The House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Health held a hearing on the legislation in June. The legislation has not moved since then.

On Twitter @aliciaault

WASHINGTON – A government shutdown will compound the negative effects that sequestration is already having on U.S. researchers’ ability to discover new therapeutics and advance knowledge in oncology and other fields, according to Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius.

Speaking Sept. 30 at the Association of American Cancer Institutes annual meeting, Ms. Sebelius said it looked increasingly likely that Congress would fail to reach a federal budget agreement and that the government would be shut down Oct. 1.

With a shutdown, "entrance to new [federally funded] clinical trials will stop right away," she said.

In the meantime, biomedical research continues to be diminished by the ongoing automatic budget cuts known as sequestration, she said. In March, Congress’ failure to come to an agreement on deficit reduction triggered an across-the-board cut at most federal agencies.

For the National Institutes of Health, that resulted in a 5% reduction to its $30 billion budget. Dr. Harold Varmus, director of the National Cancer Institute, said in May that his agency’s budget would by reduced by almost 6%, or $293 million. Most of the reduction was due to sequestration. The NCI expected to fund about 100 fewer new and competing grants than in the previous year (fiscal 2012).

Ms. Sebelius said that, at NIH overall, sequestration has resulted in 640 fewer grants being awarded in fiscal 2013 as compared to fiscal 2012. And it also has meant that there are "hundreds more projects we’ll be unable to advance in the year ahead." About 750 fewer patients were enrolled in clinical trials.

"When as a country, we neglect to invest in the NIH – the gold standard for research in the world – we pay for that neglect," she said. She added that slashing research funding hurts the nation’s global competitiveness at a time when other countries, such as India, China, South Korea, Brazil, and Japan are increasing their investment in biomedical research.

Many physician organizations and others have urged Congress to rescind the NIH budget cuts.

Oncology organizations have urged their members to support the Cancer Patient Protection Act of 2013 (H.R. 1416), which would eliminate sequestration cuts for physician-administered Medicare Part B drugs. At press time, the bill had 108 cosponsors. The House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Health held a hearing on the legislation in June. The legislation has not moved since then.

On Twitter @aliciaault

WASHINGTON – A government shutdown will compound the negative effects that sequestration is already having on U.S. researchers’ ability to discover new therapeutics and advance knowledge in oncology and other fields, according to Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius.

Speaking Sept. 30 at the Association of American Cancer Institutes annual meeting, Ms. Sebelius said it looked increasingly likely that Congress would fail to reach a federal budget agreement and that the government would be shut down Oct. 1.

With a shutdown, "entrance to new [federally funded] clinical trials will stop right away," she said.

In the meantime, biomedical research continues to be diminished by the ongoing automatic budget cuts known as sequestration, she said. In March, Congress’ failure to come to an agreement on deficit reduction triggered an across-the-board cut at most federal agencies.

For the National Institutes of Health, that resulted in a 5% reduction to its $30 billion budget. Dr. Harold Varmus, director of the National Cancer Institute, said in May that his agency’s budget would by reduced by almost 6%, or $293 million. Most of the reduction was due to sequestration. The NCI expected to fund about 100 fewer new and competing grants than in the previous year (fiscal 2012).

Ms. Sebelius said that, at NIH overall, sequestration has resulted in 640 fewer grants being awarded in fiscal 2013 as compared to fiscal 2012. And it also has meant that there are "hundreds more projects we’ll be unable to advance in the year ahead." About 750 fewer patients were enrolled in clinical trials.

"When as a country, we neglect to invest in the NIH – the gold standard for research in the world – we pay for that neglect," she said. She added that slashing research funding hurts the nation’s global competitiveness at a time when other countries, such as India, China, South Korea, Brazil, and Japan are increasing their investment in biomedical research.

Many physician organizations and others have urged Congress to rescind the NIH budget cuts.

Oncology organizations have urged their members to support the Cancer Patient Protection Act of 2013 (H.R. 1416), which would eliminate sequestration cuts for physician-administered Medicare Part B drugs. At press time, the bill had 108 cosponsors. The House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Health held a hearing on the legislation in June. The legislation has not moved since then.

On Twitter @aliciaault

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AACI

Retail clinics seeking stronger partnerships with physicians

Two of the nation’s biggest retail pharmacy chains have begun to embrace physicians as partners with their in-store clinics and, in the process, position themselves as integral parts of accountable care organizations and patient-centered medical homes.

And, some of America’s biggest and best-known health systems are returning the embrace, although somewhat tentatively.

In Ohio, the Cleveland Clinic and MinuteClinic have teamed up. The affiliation with MinuteClinic, a division of CVS Caremark, began in 2010, mainly as the Cleveland Clinic explored whether to provide drop-in care, according to Dr. Michael Rabovsky, vice chair of the Cleveland Clinic’s Medicine Institute. Now, 21 MinuteClinics carry the Cleveland Clinic brand; that number soon will expand to 24, he said.

Cleveland Clinic physicians – paid a small stipend – are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week to consult with the MinuteClinic nurse practitioners and physician assistants; they also conduct chart reviews and educational sessions with MinuteClinic staff.

The retail clinics are "helping to provide access to our patients in the right type of medical setting, where they’re going to get the best value for the cost," Dr. Rabovsky said, adding that the relationship offers patients an alternative to the emergency room, and a place get care on nights and weekends.

Having the retail clinics as an access point for urgent and primary care services also could free up physicians’ time to manage chronic diseases, Dr. Rabovsky said. "We have to figure out models to accommodate that demand."

An IT integration has strengthened the relationship. Now, when a Cleveland Clinic patient goes to a MinuteClinic, the notes from that encounter are sent electronically to his or her physician.

Dr. Andrew Sussman, MinuteClinic president, said that typically notes are faxed to the primary care physician for all encounters. When the electronic health records are integrated, notes are sent electronically and MinuteClinic providers have better access to information such as medication lists and allergies.

In collaboration with other health systems, MinuteClinic is expanding the services it provides – offering hypertension and diabetes management, for example. In those instances, the programs and protocols are developed with the collaborating health system, Dr. Sussman said.

"We don’t take over the care of their chronic disease," he said, noting that patients are always sent back to their physicians for medication adjustment or for anything that requires more than counseling or measurement. "We don’t see ourselves becoming their primary care physician or their exclusive medical home."

Dr. Rabovsky said that MinuteClinic has approached the Cleveland Clinic to offer more in-depth services, but "we haven’t decided yet how we want to partner with delivering that aspect of chronic care," he said.

In Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Medicine* is proceeding slowly on its collaboration with Walgreens. That affiliation began in 2011, with Hopkins agreeing to help develop guidelines and disease management protocols for the pharmacy chain’s Healthcare Clinics (formerly known as Take Care).

In June, the two announced their collaboration on a new model pharmacy to be built on Hopkins’ East Baltimore campus.

The store – slated to open in November – will house a Healthcare Clinic. Besides offering acute care and immunizations, the clinic will offer student health services, education, treatment and management of chronic disease, smoking cessation, and HIV testing.

For Hopkins, the idea is to have a community resource that can be closely linked back to the health system and fill in some of the gaps, said Dr. Jeanne Clark, interim director of the university’s division of general internal medicine. "I don’t think we’re providing adequate care and adequate access for all the patients," she said, suggesting collaboration with retail clinics could ensure adequate care and improve access to care for patients.*

The collaboration can offer patients better access to acute care, or it can serve as an initial transition into primary care, she said. It’s also possible that Hopkins will get referrals from the clinic.

"Together with Hopkins physicians, we’re going to be working hand-in-hand," said Dr. Jay Rosan, Walgreens’ senior vice president of health innovation.

Dr. Rosan noted that a third or more of patients who use Walgreens clinics do not have a primary care physician. Studies and surveys have shown that retail clinic users are less likely to have insurance or a usual source of care and that they are generally under age 30.

In January, Walgreens announced that it formed accountable care organizations with three physician-led groups: Advocare in Marlton, N.J.; The Diagnostic Clinic in Largo, Fla.; and Scott & White Healthcare in Temple, Tex. Walgreens pharmacists and Healthcare Clinic providers will work closely with primary care physicians to improve access and quality of care while reducing overall health care costs. The three ACOs have been approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Walgreens wants to "develop a system that makes sense for the physician and the patient community," Dr. Rosan said.

Dr. Sussman agreed. "We don’t see ourselves as separate or competitive" with physicians, he said. "We see ourselves as collaborating in an environment where there are fewer primary care physicians."

On Twitter @aliciaault

CLARIFICATION 10/4/2013: the institution with which Walgreens is collaborating was misstated. Walgreens is in collaboration with Johns Hopkins Medicine. Further, a quote from Dr. Jeanne Clark was clarified to suggest collaboration with retail clinics could ensure adequate care and improve access to care for patients.

Two of the nation’s biggest retail pharmacy chains have begun to embrace physicians as partners with their in-store clinics and, in the process, position themselves as integral parts of accountable care organizations and patient-centered medical homes.

And, some of America’s biggest and best-known health systems are returning the embrace, although somewhat tentatively.

In Ohio, the Cleveland Clinic and MinuteClinic have teamed up. The affiliation with MinuteClinic, a division of CVS Caremark, began in 2010, mainly as the Cleveland Clinic explored whether to provide drop-in care, according to Dr. Michael Rabovsky, vice chair of the Cleveland Clinic’s Medicine Institute. Now, 21 MinuteClinics carry the Cleveland Clinic brand; that number soon will expand to 24, he said.

Cleveland Clinic physicians – paid a small stipend – are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week to consult with the MinuteClinic nurse practitioners and physician assistants; they also conduct chart reviews and educational sessions with MinuteClinic staff.

The retail clinics are "helping to provide access to our patients in the right type of medical setting, where they’re going to get the best value for the cost," Dr. Rabovsky said, adding that the relationship offers patients an alternative to the emergency room, and a place get care on nights and weekends.

Having the retail clinics as an access point for urgent and primary care services also could free up physicians’ time to manage chronic diseases, Dr. Rabovsky said. "We have to figure out models to accommodate that demand."

An IT integration has strengthened the relationship. Now, when a Cleveland Clinic patient goes to a MinuteClinic, the notes from that encounter are sent electronically to his or her physician.

Dr. Andrew Sussman, MinuteClinic president, said that typically notes are faxed to the primary care physician for all encounters. When the electronic health records are integrated, notes are sent electronically and MinuteClinic providers have better access to information such as medication lists and allergies.

In collaboration with other health systems, MinuteClinic is expanding the services it provides – offering hypertension and diabetes management, for example. In those instances, the programs and protocols are developed with the collaborating health system, Dr. Sussman said.

"We don’t take over the care of their chronic disease," he said, noting that patients are always sent back to their physicians for medication adjustment or for anything that requires more than counseling or measurement. "We don’t see ourselves becoming their primary care physician or their exclusive medical home."

Dr. Rabovsky said that MinuteClinic has approached the Cleveland Clinic to offer more in-depth services, but "we haven’t decided yet how we want to partner with delivering that aspect of chronic care," he said.

In Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Medicine* is proceeding slowly on its collaboration with Walgreens. That affiliation began in 2011, with Hopkins agreeing to help develop guidelines and disease management protocols for the pharmacy chain’s Healthcare Clinics (formerly known as Take Care).

In June, the two announced their collaboration on a new model pharmacy to be built on Hopkins’ East Baltimore campus.

The store – slated to open in November – will house a Healthcare Clinic. Besides offering acute care and immunizations, the clinic will offer student health services, education, treatment and management of chronic disease, smoking cessation, and HIV testing.

For Hopkins, the idea is to have a community resource that can be closely linked back to the health system and fill in some of the gaps, said Dr. Jeanne Clark, interim director of the university’s division of general internal medicine. "I don’t think we’re providing adequate care and adequate access for all the patients," she said, suggesting collaboration with retail clinics could ensure adequate care and improve access to care for patients.*

The collaboration can offer patients better access to acute care, or it can serve as an initial transition into primary care, she said. It’s also possible that Hopkins will get referrals from the clinic.

"Together with Hopkins physicians, we’re going to be working hand-in-hand," said Dr. Jay Rosan, Walgreens’ senior vice president of health innovation.

Dr. Rosan noted that a third or more of patients who use Walgreens clinics do not have a primary care physician. Studies and surveys have shown that retail clinic users are less likely to have insurance or a usual source of care and that they are generally under age 30.

In January, Walgreens announced that it formed accountable care organizations with three physician-led groups: Advocare in Marlton, N.J.; The Diagnostic Clinic in Largo, Fla.; and Scott & White Healthcare in Temple, Tex. Walgreens pharmacists and Healthcare Clinic providers will work closely with primary care physicians to improve access and quality of care while reducing overall health care costs. The three ACOs have been approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Walgreens wants to "develop a system that makes sense for the physician and the patient community," Dr. Rosan said.

Dr. Sussman agreed. "We don’t see ourselves as separate or competitive" with physicians, he said. "We see ourselves as collaborating in an environment where there are fewer primary care physicians."

On Twitter @aliciaault

CLARIFICATION 10/4/2013: the institution with which Walgreens is collaborating was misstated. Walgreens is in collaboration with Johns Hopkins Medicine. Further, a quote from Dr. Jeanne Clark was clarified to suggest collaboration with retail clinics could ensure adequate care and improve access to care for patients.

Two of the nation’s biggest retail pharmacy chains have begun to embrace physicians as partners with their in-store clinics and, in the process, position themselves as integral parts of accountable care organizations and patient-centered medical homes.

And, some of America’s biggest and best-known health systems are returning the embrace, although somewhat tentatively.

In Ohio, the Cleveland Clinic and MinuteClinic have teamed up. The affiliation with MinuteClinic, a division of CVS Caremark, began in 2010, mainly as the Cleveland Clinic explored whether to provide drop-in care, according to Dr. Michael Rabovsky, vice chair of the Cleveland Clinic’s Medicine Institute. Now, 21 MinuteClinics carry the Cleveland Clinic brand; that number soon will expand to 24, he said.

Cleveland Clinic physicians – paid a small stipend – are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week to consult with the MinuteClinic nurse practitioners and physician assistants; they also conduct chart reviews and educational sessions with MinuteClinic staff.

The retail clinics are "helping to provide access to our patients in the right type of medical setting, where they’re going to get the best value for the cost," Dr. Rabovsky said, adding that the relationship offers patients an alternative to the emergency room, and a place get care on nights and weekends.

Having the retail clinics as an access point for urgent and primary care services also could free up physicians’ time to manage chronic diseases, Dr. Rabovsky said. "We have to figure out models to accommodate that demand."

An IT integration has strengthened the relationship. Now, when a Cleveland Clinic patient goes to a MinuteClinic, the notes from that encounter are sent electronically to his or her physician.

Dr. Andrew Sussman, MinuteClinic president, said that typically notes are faxed to the primary care physician for all encounters. When the electronic health records are integrated, notes are sent electronically and MinuteClinic providers have better access to information such as medication lists and allergies.

In collaboration with other health systems, MinuteClinic is expanding the services it provides – offering hypertension and diabetes management, for example. In those instances, the programs and protocols are developed with the collaborating health system, Dr. Sussman said.

"We don’t take over the care of their chronic disease," he said, noting that patients are always sent back to their physicians for medication adjustment or for anything that requires more than counseling or measurement. "We don’t see ourselves becoming their primary care physician or their exclusive medical home."

Dr. Rabovsky said that MinuteClinic has approached the Cleveland Clinic to offer more in-depth services, but "we haven’t decided yet how we want to partner with delivering that aspect of chronic care," he said.

In Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Medicine* is proceeding slowly on its collaboration with Walgreens. That affiliation began in 2011, with Hopkins agreeing to help develop guidelines and disease management protocols for the pharmacy chain’s Healthcare Clinics (formerly known as Take Care).

In June, the two announced their collaboration on a new model pharmacy to be built on Hopkins’ East Baltimore campus.

The store – slated to open in November – will house a Healthcare Clinic. Besides offering acute care and immunizations, the clinic will offer student health services, education, treatment and management of chronic disease, smoking cessation, and HIV testing.

For Hopkins, the idea is to have a community resource that can be closely linked back to the health system and fill in some of the gaps, said Dr. Jeanne Clark, interim director of the university’s division of general internal medicine. "I don’t think we’re providing adequate care and adequate access for all the patients," she said, suggesting collaboration with retail clinics could ensure adequate care and improve access to care for patients.*

The collaboration can offer patients better access to acute care, or it can serve as an initial transition into primary care, she said. It’s also possible that Hopkins will get referrals from the clinic.

"Together with Hopkins physicians, we’re going to be working hand-in-hand," said Dr. Jay Rosan, Walgreens’ senior vice president of health innovation.

Dr. Rosan noted that a third or more of patients who use Walgreens clinics do not have a primary care physician. Studies and surveys have shown that retail clinic users are less likely to have insurance or a usual source of care and that they are generally under age 30.

In January, Walgreens announced that it formed accountable care organizations with three physician-led groups: Advocare in Marlton, N.J.; The Diagnostic Clinic in Largo, Fla.; and Scott & White Healthcare in Temple, Tex. Walgreens pharmacists and Healthcare Clinic providers will work closely with primary care physicians to improve access and quality of care while reducing overall health care costs. The three ACOs have been approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Walgreens wants to "develop a system that makes sense for the physician and the patient community," Dr. Rosan said.

Dr. Sussman agreed. "We don’t see ourselves as separate or competitive" with physicians, he said. "We see ourselves as collaborating in an environment where there are fewer primary care physicians."

On Twitter @aliciaault

CLARIFICATION 10/4/2013: the institution with which Walgreens is collaborating was misstated. Walgreens is in collaboration with Johns Hopkins Medicine. Further, a quote from Dr. Jeanne Clark was clarified to suggest collaboration with retail clinics could ensure adequate care and improve access to care for patients.

ACO spillover effect: lower spending for all

Implementing the requirements of an accountable care organization for one group of patients may lower costs and improve care for every patient seen in a physician’s practice, according to a study published online Aug. 27 in JAMA.

Dr. J. Michael McWilliams of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his colleagues looked at whether the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts’ Alternative Quality Contract (AQC), a successful ACO started in 2009, was associated with changes in spending or quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries who were not part of the ACO.

In the AQC, physicians and other providers assumed financial risk if they spent more than a global budget, but shared savings with the insurer if spending was under budget. Physicians could also receive bonuses for meeting quality targets.

The investigators compared total quarterly medical spending per beneficiary between two groups: beneficiaries who received care through the AQC in 2009 or 2010 (1.7 million person-years) and controls who received care from other providers (JAMA 2013;310:829-836).

Quarterly spending per beneficiary in 2007 and 2008 (prior to the AQC contracts) was $150 higher for the AQC group than the control group. Two years after the AQC contracts went into effect, the difference was $51 per quarter. The biggest reduction in spending was for beneficiaries with five or more conditions, and in spending on outpatient care. Spending was significantly reduced for office visits, emergency department visits, minor procedures, imaging, and lab tests.

Some improvement was seen on quality measures. The number of beneficiaries tested for low-density lipoprotein levels increased. Prior to the AQC, LDL testing rates for diabetic beneficiaries in the AQC group were 2.2% higher than for controls. By the second year, the testing rate was 5.2% higher for those in the AQC. LDL testing rates also improved for cardiovascular disease patients in the AQC.

No improvement was seen on other quality measures, including hospitalization for an ambulatory care–sensitive condition related to cardiovascular disease or diabetes; readmission within 30 days of discharge; screening mammography for women aged 65-69 years; LDL testing for beneficiaries with a history of ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, or stroke; and hemoglobin A1c testing and retinal exams for beneficiaries with diabetes.

"These findings suggest that global payment incentives in the AQC elicited responses from participating organizations that extended beyond targeted case management of BCBS enrollees," the authors wrote.

Overall, the study "suggests that organizations in Massachusetts willing to assume greater financial risk were capable of achieving modest reductions in spending for Medicare beneficiaries without compromising quality of care," wrote Dr. McWilliams and his colleagues.

The study also showed that physicians and provider organizations who see spillover effects from one ACO contract might be willing "to enter similar contracts with additional insurers."

But there is a potential downside to the spillover effect, according to the authors: Because cost and quality may be improved overall, "competing insurers with similar provider networks could offer lower premiums without incurring the costs of managing an ACO."

On Twitter @aliciaault

The Alternative Quality Contract is touted as a payment mechanism where "provider organizations bear financial risk for spending in excess of a global budget, gain from reducing spending below the budget, and receive bonuses for meeting performance targets on quality measures." Groups are incentivized to steer patients toward lower-cost specialists, achieving savings through shifting procedures, imaging, and tests to facilities with lower fees, as well as reduced utilization. At present, the only AQC measure that touches upon gastroenterology is colorectal cancer screening rates.

The authors note that the AQC "was associated with significant reductions in spending for Medicare beneficiaries but not with consistently better quality of care." If you are financially at risk for a significant group of your patients, you will likely treat all of your patients in a similar manner regardless of payment source. The imperative to cut costs will lead risk-bearing providers to seek the least costly manner for achieving the process quality metric that they are eligible to receive bonuses on. The risk for hospital-based specialists is clear – those who lack access to a lower cost site of service are in danger of being marginalized out of the network, even if one’s outcomes are superior. The imperative for gastroenterology is to develop outcome measures such as complication rates after endoscopic procedures, so that what we are being measured on is more meaningful than just cost.

Dr. Joel Brill, AGAF, is chief medical officer of predictive health, LLC, in Phoenix, and is an assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of Arizona School of Medicine, Tucson. He represents the AGA at FairHealth Inc., which was established to serve as an independent, objective, and transparent source of health care reimbursement data.

The Alternative Quality Contract is touted as a payment mechanism where "provider organizations bear financial risk for spending in excess of a global budget, gain from reducing spending below the budget, and receive bonuses for meeting performance targets on quality measures." Groups are incentivized to steer patients toward lower-cost specialists, achieving savings through shifting procedures, imaging, and tests to facilities with lower fees, as well as reduced utilization. At present, the only AQC measure that touches upon gastroenterology is colorectal cancer screening rates.

The authors note that the AQC "was associated with significant reductions in spending for Medicare beneficiaries but not with consistently better quality of care." If you are financially at risk for a significant group of your patients, you will likely treat all of your patients in a similar manner regardless of payment source. The imperative to cut costs will lead risk-bearing providers to seek the least costly manner for achieving the process quality metric that they are eligible to receive bonuses on. The risk for hospital-based specialists is clear – those who lack access to a lower cost site of service are in danger of being marginalized out of the network, even if one’s outcomes are superior. The imperative for gastroenterology is to develop outcome measures such as complication rates after endoscopic procedures, so that what we are being measured on is more meaningful than just cost.

Dr. Joel Brill, AGAF, is chief medical officer of predictive health, LLC, in Phoenix, and is an assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of Arizona School of Medicine, Tucson. He represents the AGA at FairHealth Inc., which was established to serve as an independent, objective, and transparent source of health care reimbursement data.

The Alternative Quality Contract is touted as a payment mechanism where "provider organizations bear financial risk for spending in excess of a global budget, gain from reducing spending below the budget, and receive bonuses for meeting performance targets on quality measures." Groups are incentivized to steer patients toward lower-cost specialists, achieving savings through shifting procedures, imaging, and tests to facilities with lower fees, as well as reduced utilization. At present, the only AQC measure that touches upon gastroenterology is colorectal cancer screening rates.

The authors note that the AQC "was associated with significant reductions in spending for Medicare beneficiaries but not with consistently better quality of care." If you are financially at risk for a significant group of your patients, you will likely treat all of your patients in a similar manner regardless of payment source. The imperative to cut costs will lead risk-bearing providers to seek the least costly manner for achieving the process quality metric that they are eligible to receive bonuses on. The risk for hospital-based specialists is clear – those who lack access to a lower cost site of service are in danger of being marginalized out of the network, even if one’s outcomes are superior. The imperative for gastroenterology is to develop outcome measures such as complication rates after endoscopic procedures, so that what we are being measured on is more meaningful than just cost.