User login

Acute and Recurrent Bacterial Vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the most common cause of abnormal vaginal discharge in women of reproductive age, with a prevalence in North America of 29.2% among women ages 14 to 49.1-3 BV is a condition in which the normal vaginal flora are altered, primarily due to a reduction in hydrogen peroxide–producing strains of lactobacilli. This leads to an elevated vaginal pH and increased levels of proteolytic enzymes (eg, sialidase), organic acids, and volatile amines.4 This change in pH allows an overgrowth of multiple types of anaerobic, mycoplasmic, and gram-negative bacteria.

In most cases of BV, the predominant microbe is the facultative anaerobe Gardnerella vaginalis. However, evidence from recent studies of the pathogenesis of BV suggests that this bacterium forms a biofilm in the vaginal epithelium that serves as a “scaffolding” to which other bacterial species adhere in a symbiotic fashion, colonizing the vagina.5 Though asymptomatic in at least half of affected women,2,6,7 this polymicrobial condition can produce a thin, white, homogenous discharge with a distinct “fishy” odor.

The changes in the vaginal flora seen in BV are associated with serious sequelae, such as preterm delivery, spontaneous abortion, postpartum endometritis, and increased susceptibility to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).4,8,9 The polymicrobial nature of BV and its propensity for recurrence make treatment a challenge.

PATIENT PRESENTATION/HISTORY

The most common symptom of BV is increased vaginal discharge, which usually is thin and white or dull gray.4 Some women report a strong fishy odor, especially after sex. Vaginal pain, itching, or burning may also be present, especially if the discharge is copious. Dyspareunia and dysuria are rare, but possible, symptoms. Fever, malaise, and other systemic symptoms are not associated with BV and should prompt the clinician to consider other causes. About half of women with bacterial vaginosis have no symptoms.2,6

The typical finding on physical examination is a homogeneous, off-white, creamy, malodorous discharge that adheres to the vaginal walls and pools in the vaginal vault. There are usually no or minimal signs of vaginal inflammation, and the vulva, labia, and cervix are typically normal. In some cases, BV can lead to cervicitis.6,9,10

Continue for the diagnosis >>

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of BV can be made based on the history, physical examination, and microscopic examination of the vaginal discharge. Unlike with many other bacterial diseases, culture is not recommended for diagnosis of BV because many of the implicated organisms cannot be easily isolated in the laboratory, and because asymptomatic women also have small numbers of these flora in the vagina.

In 1991, Nugent et al11 described a Gram stain scoring system of vaginal smears to diagnose BV, which has a sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 96%, respectively; it remains the gold standard for diagnosis.7 However, because this method requires considerable time and skill, it is not routinely used in most clinic settings.

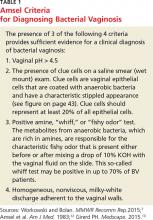

A widely used method of diagnosing BV is the Amsel criteria (see Table 1). The Amsel method has a sensitivity and specificity of 81% and 94%, respectively.1,12 The presence of clue cells is the most reliable indicator of BV (see figure). The positive predictive value of this test for the presence of BV is 95%.14 The Amsel method requires microscopy,4,12 which is not always available in clinics.

There are several commercially available point-of-care tests for BV that do not require microscopy. These include rapid antigen and nucleic acid amplification tests to detect elevated levels of G vaginalis, as well as tests that detect the presence of bacterial amines, elevated vaginal pH, and bacterial sialidase.4,7,15 Compared with the Nugent and Amsel methods, one test that detects elevated vaginal fluid sialidase activity was shown to have a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 91% to 95%.4,7,15 These point-of-care tests are most effective for diagnosing BV when the vaginal pH exceeds 4.5 and when they are used in conjunction with other clinical criteria.

Continue for treatment/management >>

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

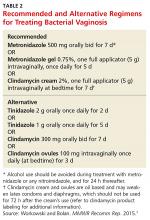

Treatment is recommended for women with symptoms. The established benefit of therapy in nonpregnant women is relief of vaginal symptoms and signs of infection. Other potential benefits to treatment include reduction in the risk for Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhea infection, HIV, and other viral STIs. Table 2 includes the recommended and alternative treatment regimens for BV, according to the CDC’s 2015 treatment guidelines for sexually transmitted infections.7 These regimens are also recommended by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).16

Treatment is also recommended for all symptomatic pregnant women. Older CDC guidelines noted a preference for oral therapy in pregnant women with BV, due to the possibility of subclinical upper genital tract infection.17 However, the 2015 CDC guidelinesstate that symptomatic pregnant women can be treated with either the oral or vaginal regimens recommended for nonpregnant women, as oral therapy has not been shown to outperform vaginal therapy in effecting cure or preventing adverse outcomes.7

PATIENT EDUCATION AND FOLLOW-UP

Patient preferences, possible adverse effects, drug interactions, and other coinfections should be considered when selecting a treatment regimen. Women should be advised to refrain from sexual intercourse or to use condoms consistently and correctly during treatment. Douching may increase the risk for relapse, and no data support its use for treatment or relief of symptoms. Follow-up visits are unnecessary unless symptoms do not resolve. Because recurrence of BV is common, however, women should be advised to return for evaluation if symptoms recur.1,8,18

Continue for when BV recurs >>

WHEN BV RECURS

Recurrence rates of 15% to 30% have been reported at three months,18,19 and of 28% when patients were tested cumulatively over six months,1 but few researchers have looked at long-term recurrence rates. In one observational study, recurrence rates of 51% were reported during a six-year follow-up period among women previously treated with oral metronidazole.20 Whether these high recurrence rates are due to treatment failure to eradicate the causative organism or to a reinfection from sexual partners remains unclear.21 Some studies have shown that treatment of male partners does not affect recurrence rates.21,22

Risk factors

Various research teams have identified risk factors associated with BV recurrence, but study results have been inconsistent. The strongest risk factor appears to be sexual activity, specifically with increased numbers of sexual partners and inconsistent condom use.1,23,24 Women who have sex with women also appear to be at increased risk for BV recurrence.9,10

BV tends to recur around the time of menstruation, and some suppressive therapies include administration of antibiotics during this time.1,8 Although reports conflict, other risk factors that may be implicated in recurrent BV include vaginal douching, cigarette smoking, and increased BMI.2,18 Use of an oral contraceptive may have a protective effect against BV recurrence.1

Caring for patients with multiple recurrences of BV can be challenging for many clinicians. Although a few studies have evaluated suppressive therapy for recurrent BV, there are no clear treatment guidelines for multiple recurrent infections. Sobel and colleagues evaluated twice-weekly use of metronidazole gel for 16 weeks and found a significant reduction in BV recurrence during treatment.25 However, there was only a 34% to 37% probability of patients’ remaining clinically cured at seven months posttreatment. Similarly, Reichman et al evaluated suppressive therapy with oral metronidazole, topical boric acid, and metronidazole gel. They found an 88% to 92% initial cure rate, but a 50% failure rate at 36 weeks’ follow-up.26

Management

Studies examining the use of probiotics for the prevention and treatment of BV have yielded mixed results. The theory is that probiotics containing lactobacillus organisms may protect women from infection by maintaining or restoring vaginal pH and preventing adhesion of bacteria to the epithelium of the vaginal walls.27 Despite the conflicting results, no adverse effects have been reported and, as a consequence, many experts recommend probiotics to reduce the risk for recurrent BV. When discussing suppressive therapy options with patients, clinicians should be mindful of the limited data and the clinically unfavorable long-term cure rates demonstrated.

In addition to treatment limitations for recurrent BV, clinicians often find it challenging to effectively address the psychosocial implications of distress, embarrassment, and lack of control that are commonly associated with recurrent BV.28 Beyond its impact on sexual activity, women have also reported refraining from their daily activities out of fear that others around them may detect their vaginal odor. Helping women take a proactive approach in the treatment and prevention of BV may ease some of this distress.

Women with recurrent BV are often eager to hear about measures they can take to reduce their risk for acute and recurrent infection. Patients should be counseled on the association of BV with douching, numerous sexual partners, unprotected sex, increased psychosocial stress, and cigarette smoking.7,18,29-31 Patients may inquire about the potential risk for BV when they use feminine hygiene spray, panty liners or pads, and underwear made from synthetic fabrics; however, one longitudinal study30 showed no association between any of these hygienic behaviors and BV.

Continue for the conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Bacterial vaginosis is a common cause of vaginal discharge in women. Current recommendations for treatment are not very effective, with up to half of women experiencing recurrence. The likelihood of recurrence can result in significant frustration for both patient and clinician. Although recent studies have advanced our understanding of the pathophysiology of BV, further research is needed to develop more effective treatments that reduce recurrence. Addressing modifiable risk factors and considering the use of suppressive and/or probiotic therapy may improve quality of life for women affected by this condition.

REFERENCES

1. Bradshaw CS, Vodstrcil LA, Hocking JS, et al. Recurrence of bacterial vaginosis is significantly associated with posttreatment sexual activities and hormonal contraceptive use. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(6):777-786.

2. Koumans EH, Sternberg M, Bruce C, et al. The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in the United States, 2001-2004: associations with symptoms, sexual behaviors, and reproductive health. Sex Trans Dis. 2007;34(11): 864-869.

3. Allsworth JE, Peipert JF. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis: 2001-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(1):114-120.

4. Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Garland SM, et al. Evaluation of a point-of-care test, BVBlue, and clinical and laboratory criteria for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(3):1304-1308.

5. Swidsinski A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, et al. An adherent Gardnerella vaginalis biofilm persists on the vaginal epithelium after standard therapy with oral metronidazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(1):97.e1-e6.

6. Schwebke JR. Vaginal discharge. In: Klausner JD, Hook EW III, eds. Current Diagnosis & Treatment of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007. http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=369&Sectionid=39914778. Accessed November 11, 2015.

7. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; CDC. Bacterial vaginosis. In: Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):69-72.

8. Hay P. Recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22(1): 82-86.

9. Taylor BD, Darville T, Haggerty CL. Does bacterial vaginosis cause pelvic inflammatory disease? Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(2):117-122.

10. Marrazzo JM, Wiesenfeld HC, Murray PG, et al. Risk factors for cervicitis among women with bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(5):617-624.

11. Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of Gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29(2):297-301.

12. Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, et al. Nonspecific vaginitis: diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983; 74(1):14-22.

13. Girerd PH. Bacterial vaginosis workup (2014). http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/254342-workup. Accessed November 11, 2015.

14. Hoffman BL, Schorge JO, Schaffer JI, et al. Gynecologic infection. In: Hoffman BL, Schorge JO, Schaffer JI, et al, eds. Williams Gynecology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

15. Hainer BL, Gibson MV. Vaginitis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(7):807-815.

16. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists, No. 72: Vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(5):1195-1206.

17. Workowski KA, Berman S; CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12): 1-110.

18. Wilson J. Managing recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(1):8-11.

19. Cook RL, Redondo-Lopez V, Schmitt C, et al. Clinical, microbiological, and biochemical factors in recurrent bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(4):870-877.

20. Boris J, Påhlson C, Larsson P-G. Six years observation after successful treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Infect Dis Obstetr Gynecol. 1997;5(4): 297-302.

21. Mehta SD. Systematic review of randomized trials of treatment of male sexual partners for improved bacterial vaginosis outcomes in women. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(10):822-830.

22. Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(11): 1478-1486.

23. Fethers KA, Fairley CK, Hocking JS, et al. Sexual risk factors and bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(11):1426-1435.

24. Schwebke JR, Desmond RA. A randomized trial of the duration of therapy with metronidazole plus or minus azithromycin for treatment of symptomatic bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):213-219.

25. Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1283-1289.

26. Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(11):732-734.

27. Homayouni A, Bastani P, Ziyadi S, et al. Effects of probiotics on the recurrence of bacterial vaginosis: a review. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014;18(1):79-86.

28. Bilardi JE, Walker S, Temple-Smith M, et al. The burden of bacterial vaginosis: women’s experience of the physical, emotional, sexual and social impact of living with recurrent bacterial vaginosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e74378.

29. Smart S, Singal A, Mindel A. Social and sexual risk factors for bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(1):58-62.

30. Klebanoff MA, Nansel TR, Brotman RM, et al. Personal hygienic behaviors and bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(2):94-99.

31. Nansel TR, Riggs MA, Yu K-F, et al. The association of psychosocial stress and bacterial vaginosis in a longitudinal cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(2):381-386.

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the most common cause of abnormal vaginal discharge in women of reproductive age, with a prevalence in North America of 29.2% among women ages 14 to 49.1-3 BV is a condition in which the normal vaginal flora are altered, primarily due to a reduction in hydrogen peroxide–producing strains of lactobacilli. This leads to an elevated vaginal pH and increased levels of proteolytic enzymes (eg, sialidase), organic acids, and volatile amines.4 This change in pH allows an overgrowth of multiple types of anaerobic, mycoplasmic, and gram-negative bacteria.

In most cases of BV, the predominant microbe is the facultative anaerobe Gardnerella vaginalis. However, evidence from recent studies of the pathogenesis of BV suggests that this bacterium forms a biofilm in the vaginal epithelium that serves as a “scaffolding” to which other bacterial species adhere in a symbiotic fashion, colonizing the vagina.5 Though asymptomatic in at least half of affected women,2,6,7 this polymicrobial condition can produce a thin, white, homogenous discharge with a distinct “fishy” odor.

The changes in the vaginal flora seen in BV are associated with serious sequelae, such as preterm delivery, spontaneous abortion, postpartum endometritis, and increased susceptibility to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).4,8,9 The polymicrobial nature of BV and its propensity for recurrence make treatment a challenge.

PATIENT PRESENTATION/HISTORY

The most common symptom of BV is increased vaginal discharge, which usually is thin and white or dull gray.4 Some women report a strong fishy odor, especially after sex. Vaginal pain, itching, or burning may also be present, especially if the discharge is copious. Dyspareunia and dysuria are rare, but possible, symptoms. Fever, malaise, and other systemic symptoms are not associated with BV and should prompt the clinician to consider other causes. About half of women with bacterial vaginosis have no symptoms.2,6

The typical finding on physical examination is a homogeneous, off-white, creamy, malodorous discharge that adheres to the vaginal walls and pools in the vaginal vault. There are usually no or minimal signs of vaginal inflammation, and the vulva, labia, and cervix are typically normal. In some cases, BV can lead to cervicitis.6,9,10

Continue for the diagnosis >>

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of BV can be made based on the history, physical examination, and microscopic examination of the vaginal discharge. Unlike with many other bacterial diseases, culture is not recommended for diagnosis of BV because many of the implicated organisms cannot be easily isolated in the laboratory, and because asymptomatic women also have small numbers of these flora in the vagina.

In 1991, Nugent et al11 described a Gram stain scoring system of vaginal smears to diagnose BV, which has a sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 96%, respectively; it remains the gold standard for diagnosis.7 However, because this method requires considerable time and skill, it is not routinely used in most clinic settings.

A widely used method of diagnosing BV is the Amsel criteria (see Table 1). The Amsel method has a sensitivity and specificity of 81% and 94%, respectively.1,12 The presence of clue cells is the most reliable indicator of BV (see figure). The positive predictive value of this test for the presence of BV is 95%.14 The Amsel method requires microscopy,4,12 which is not always available in clinics.

There are several commercially available point-of-care tests for BV that do not require microscopy. These include rapid antigen and nucleic acid amplification tests to detect elevated levels of G vaginalis, as well as tests that detect the presence of bacterial amines, elevated vaginal pH, and bacterial sialidase.4,7,15 Compared with the Nugent and Amsel methods, one test that detects elevated vaginal fluid sialidase activity was shown to have a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 91% to 95%.4,7,15 These point-of-care tests are most effective for diagnosing BV when the vaginal pH exceeds 4.5 and when they are used in conjunction with other clinical criteria.

Continue for treatment/management >>

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

Treatment is recommended for women with symptoms. The established benefit of therapy in nonpregnant women is relief of vaginal symptoms and signs of infection. Other potential benefits to treatment include reduction in the risk for Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhea infection, HIV, and other viral STIs. Table 2 includes the recommended and alternative treatment regimens for BV, according to the CDC’s 2015 treatment guidelines for sexually transmitted infections.7 These regimens are also recommended by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).16

Treatment is also recommended for all symptomatic pregnant women. Older CDC guidelines noted a preference for oral therapy in pregnant women with BV, due to the possibility of subclinical upper genital tract infection.17 However, the 2015 CDC guidelinesstate that symptomatic pregnant women can be treated with either the oral or vaginal regimens recommended for nonpregnant women, as oral therapy has not been shown to outperform vaginal therapy in effecting cure or preventing adverse outcomes.7

PATIENT EDUCATION AND FOLLOW-UP

Patient preferences, possible adverse effects, drug interactions, and other coinfections should be considered when selecting a treatment regimen. Women should be advised to refrain from sexual intercourse or to use condoms consistently and correctly during treatment. Douching may increase the risk for relapse, and no data support its use for treatment or relief of symptoms. Follow-up visits are unnecessary unless symptoms do not resolve. Because recurrence of BV is common, however, women should be advised to return for evaluation if symptoms recur.1,8,18

Continue for when BV recurs >>

WHEN BV RECURS

Recurrence rates of 15% to 30% have been reported at three months,18,19 and of 28% when patients were tested cumulatively over six months,1 but few researchers have looked at long-term recurrence rates. In one observational study, recurrence rates of 51% were reported during a six-year follow-up period among women previously treated with oral metronidazole.20 Whether these high recurrence rates are due to treatment failure to eradicate the causative organism or to a reinfection from sexual partners remains unclear.21 Some studies have shown that treatment of male partners does not affect recurrence rates.21,22

Risk factors

Various research teams have identified risk factors associated with BV recurrence, but study results have been inconsistent. The strongest risk factor appears to be sexual activity, specifically with increased numbers of sexual partners and inconsistent condom use.1,23,24 Women who have sex with women also appear to be at increased risk for BV recurrence.9,10

BV tends to recur around the time of menstruation, and some suppressive therapies include administration of antibiotics during this time.1,8 Although reports conflict, other risk factors that may be implicated in recurrent BV include vaginal douching, cigarette smoking, and increased BMI.2,18 Use of an oral contraceptive may have a protective effect against BV recurrence.1

Caring for patients with multiple recurrences of BV can be challenging for many clinicians. Although a few studies have evaluated suppressive therapy for recurrent BV, there are no clear treatment guidelines for multiple recurrent infections. Sobel and colleagues evaluated twice-weekly use of metronidazole gel for 16 weeks and found a significant reduction in BV recurrence during treatment.25 However, there was only a 34% to 37% probability of patients’ remaining clinically cured at seven months posttreatment. Similarly, Reichman et al evaluated suppressive therapy with oral metronidazole, topical boric acid, and metronidazole gel. They found an 88% to 92% initial cure rate, but a 50% failure rate at 36 weeks’ follow-up.26

Management

Studies examining the use of probiotics for the prevention and treatment of BV have yielded mixed results. The theory is that probiotics containing lactobacillus organisms may protect women from infection by maintaining or restoring vaginal pH and preventing adhesion of bacteria to the epithelium of the vaginal walls.27 Despite the conflicting results, no adverse effects have been reported and, as a consequence, many experts recommend probiotics to reduce the risk for recurrent BV. When discussing suppressive therapy options with patients, clinicians should be mindful of the limited data and the clinically unfavorable long-term cure rates demonstrated.

In addition to treatment limitations for recurrent BV, clinicians often find it challenging to effectively address the psychosocial implications of distress, embarrassment, and lack of control that are commonly associated with recurrent BV.28 Beyond its impact on sexual activity, women have also reported refraining from their daily activities out of fear that others around them may detect their vaginal odor. Helping women take a proactive approach in the treatment and prevention of BV may ease some of this distress.

Women with recurrent BV are often eager to hear about measures they can take to reduce their risk for acute and recurrent infection. Patients should be counseled on the association of BV with douching, numerous sexual partners, unprotected sex, increased psychosocial stress, and cigarette smoking.7,18,29-31 Patients may inquire about the potential risk for BV when they use feminine hygiene spray, panty liners or pads, and underwear made from synthetic fabrics; however, one longitudinal study30 showed no association between any of these hygienic behaviors and BV.

Continue for the conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Bacterial vaginosis is a common cause of vaginal discharge in women. Current recommendations for treatment are not very effective, with up to half of women experiencing recurrence. The likelihood of recurrence can result in significant frustration for both patient and clinician. Although recent studies have advanced our understanding of the pathophysiology of BV, further research is needed to develop more effective treatments that reduce recurrence. Addressing modifiable risk factors and considering the use of suppressive and/or probiotic therapy may improve quality of life for women affected by this condition.

REFERENCES

1. Bradshaw CS, Vodstrcil LA, Hocking JS, et al. Recurrence of bacterial vaginosis is significantly associated with posttreatment sexual activities and hormonal contraceptive use. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(6):777-786.

2. Koumans EH, Sternberg M, Bruce C, et al. The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in the United States, 2001-2004: associations with symptoms, sexual behaviors, and reproductive health. Sex Trans Dis. 2007;34(11): 864-869.

3. Allsworth JE, Peipert JF. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis: 2001-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(1):114-120.

4. Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Garland SM, et al. Evaluation of a point-of-care test, BVBlue, and clinical and laboratory criteria for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(3):1304-1308.

5. Swidsinski A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, et al. An adherent Gardnerella vaginalis biofilm persists on the vaginal epithelium after standard therapy with oral metronidazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(1):97.e1-e6.

6. Schwebke JR. Vaginal discharge. In: Klausner JD, Hook EW III, eds. Current Diagnosis & Treatment of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007. http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=369&Sectionid=39914778. Accessed November 11, 2015.

7. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; CDC. Bacterial vaginosis. In: Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):69-72.

8. Hay P. Recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22(1): 82-86.

9. Taylor BD, Darville T, Haggerty CL. Does bacterial vaginosis cause pelvic inflammatory disease? Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(2):117-122.

10. Marrazzo JM, Wiesenfeld HC, Murray PG, et al. Risk factors for cervicitis among women with bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(5):617-624.

11. Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of Gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29(2):297-301.

12. Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, et al. Nonspecific vaginitis: diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983; 74(1):14-22.

13. Girerd PH. Bacterial vaginosis workup (2014). http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/254342-workup. Accessed November 11, 2015.

14. Hoffman BL, Schorge JO, Schaffer JI, et al. Gynecologic infection. In: Hoffman BL, Schorge JO, Schaffer JI, et al, eds. Williams Gynecology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

15. Hainer BL, Gibson MV. Vaginitis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(7):807-815.

16. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists, No. 72: Vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(5):1195-1206.

17. Workowski KA, Berman S; CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12): 1-110.

18. Wilson J. Managing recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(1):8-11.

19. Cook RL, Redondo-Lopez V, Schmitt C, et al. Clinical, microbiological, and biochemical factors in recurrent bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(4):870-877.

20. Boris J, Påhlson C, Larsson P-G. Six years observation after successful treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Infect Dis Obstetr Gynecol. 1997;5(4): 297-302.

21. Mehta SD. Systematic review of randomized trials of treatment of male sexual partners for improved bacterial vaginosis outcomes in women. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(10):822-830.

22. Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(11): 1478-1486.

23. Fethers KA, Fairley CK, Hocking JS, et al. Sexual risk factors and bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(11):1426-1435.

24. Schwebke JR, Desmond RA. A randomized trial of the duration of therapy with metronidazole plus or minus azithromycin for treatment of symptomatic bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):213-219.

25. Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1283-1289.

26. Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(11):732-734.

27. Homayouni A, Bastani P, Ziyadi S, et al. Effects of probiotics on the recurrence of bacterial vaginosis: a review. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014;18(1):79-86.

28. Bilardi JE, Walker S, Temple-Smith M, et al. The burden of bacterial vaginosis: women’s experience of the physical, emotional, sexual and social impact of living with recurrent bacterial vaginosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e74378.

29. Smart S, Singal A, Mindel A. Social and sexual risk factors for bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(1):58-62.

30. Klebanoff MA, Nansel TR, Brotman RM, et al. Personal hygienic behaviors and bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(2):94-99.

31. Nansel TR, Riggs MA, Yu K-F, et al. The association of psychosocial stress and bacterial vaginosis in a longitudinal cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(2):381-386.

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the most common cause of abnormal vaginal discharge in women of reproductive age, with a prevalence in North America of 29.2% among women ages 14 to 49.1-3 BV is a condition in which the normal vaginal flora are altered, primarily due to a reduction in hydrogen peroxide–producing strains of lactobacilli. This leads to an elevated vaginal pH and increased levels of proteolytic enzymes (eg, sialidase), organic acids, and volatile amines.4 This change in pH allows an overgrowth of multiple types of anaerobic, mycoplasmic, and gram-negative bacteria.

In most cases of BV, the predominant microbe is the facultative anaerobe Gardnerella vaginalis. However, evidence from recent studies of the pathogenesis of BV suggests that this bacterium forms a biofilm in the vaginal epithelium that serves as a “scaffolding” to which other bacterial species adhere in a symbiotic fashion, colonizing the vagina.5 Though asymptomatic in at least half of affected women,2,6,7 this polymicrobial condition can produce a thin, white, homogenous discharge with a distinct “fishy” odor.

The changes in the vaginal flora seen in BV are associated with serious sequelae, such as preterm delivery, spontaneous abortion, postpartum endometritis, and increased susceptibility to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).4,8,9 The polymicrobial nature of BV and its propensity for recurrence make treatment a challenge.

PATIENT PRESENTATION/HISTORY

The most common symptom of BV is increased vaginal discharge, which usually is thin and white or dull gray.4 Some women report a strong fishy odor, especially after sex. Vaginal pain, itching, or burning may also be present, especially if the discharge is copious. Dyspareunia and dysuria are rare, but possible, symptoms. Fever, malaise, and other systemic symptoms are not associated with BV and should prompt the clinician to consider other causes. About half of women with bacterial vaginosis have no symptoms.2,6

The typical finding on physical examination is a homogeneous, off-white, creamy, malodorous discharge that adheres to the vaginal walls and pools in the vaginal vault. There are usually no or minimal signs of vaginal inflammation, and the vulva, labia, and cervix are typically normal. In some cases, BV can lead to cervicitis.6,9,10

Continue for the diagnosis >>

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of BV can be made based on the history, physical examination, and microscopic examination of the vaginal discharge. Unlike with many other bacterial diseases, culture is not recommended for diagnosis of BV because many of the implicated organisms cannot be easily isolated in the laboratory, and because asymptomatic women also have small numbers of these flora in the vagina.

In 1991, Nugent et al11 described a Gram stain scoring system of vaginal smears to diagnose BV, which has a sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 96%, respectively; it remains the gold standard for diagnosis.7 However, because this method requires considerable time and skill, it is not routinely used in most clinic settings.

A widely used method of diagnosing BV is the Amsel criteria (see Table 1). The Amsel method has a sensitivity and specificity of 81% and 94%, respectively.1,12 The presence of clue cells is the most reliable indicator of BV (see figure). The positive predictive value of this test for the presence of BV is 95%.14 The Amsel method requires microscopy,4,12 which is not always available in clinics.

There are several commercially available point-of-care tests for BV that do not require microscopy. These include rapid antigen and nucleic acid amplification tests to detect elevated levels of G vaginalis, as well as tests that detect the presence of bacterial amines, elevated vaginal pH, and bacterial sialidase.4,7,15 Compared with the Nugent and Amsel methods, one test that detects elevated vaginal fluid sialidase activity was shown to have a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 91% to 95%.4,7,15 These point-of-care tests are most effective for diagnosing BV when the vaginal pH exceeds 4.5 and when they are used in conjunction with other clinical criteria.

Continue for treatment/management >>

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

Treatment is recommended for women with symptoms. The established benefit of therapy in nonpregnant women is relief of vaginal symptoms and signs of infection. Other potential benefits to treatment include reduction in the risk for Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhea infection, HIV, and other viral STIs. Table 2 includes the recommended and alternative treatment regimens for BV, according to the CDC’s 2015 treatment guidelines for sexually transmitted infections.7 These regimens are also recommended by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).16

Treatment is also recommended for all symptomatic pregnant women. Older CDC guidelines noted a preference for oral therapy in pregnant women with BV, due to the possibility of subclinical upper genital tract infection.17 However, the 2015 CDC guidelinesstate that symptomatic pregnant women can be treated with either the oral or vaginal regimens recommended for nonpregnant women, as oral therapy has not been shown to outperform vaginal therapy in effecting cure or preventing adverse outcomes.7

PATIENT EDUCATION AND FOLLOW-UP

Patient preferences, possible adverse effects, drug interactions, and other coinfections should be considered when selecting a treatment regimen. Women should be advised to refrain from sexual intercourse or to use condoms consistently and correctly during treatment. Douching may increase the risk for relapse, and no data support its use for treatment or relief of symptoms. Follow-up visits are unnecessary unless symptoms do not resolve. Because recurrence of BV is common, however, women should be advised to return for evaluation if symptoms recur.1,8,18

Continue for when BV recurs >>

WHEN BV RECURS

Recurrence rates of 15% to 30% have been reported at three months,18,19 and of 28% when patients were tested cumulatively over six months,1 but few researchers have looked at long-term recurrence rates. In one observational study, recurrence rates of 51% were reported during a six-year follow-up period among women previously treated with oral metronidazole.20 Whether these high recurrence rates are due to treatment failure to eradicate the causative organism or to a reinfection from sexual partners remains unclear.21 Some studies have shown that treatment of male partners does not affect recurrence rates.21,22

Risk factors

Various research teams have identified risk factors associated with BV recurrence, but study results have been inconsistent. The strongest risk factor appears to be sexual activity, specifically with increased numbers of sexual partners and inconsistent condom use.1,23,24 Women who have sex with women also appear to be at increased risk for BV recurrence.9,10

BV tends to recur around the time of menstruation, and some suppressive therapies include administration of antibiotics during this time.1,8 Although reports conflict, other risk factors that may be implicated in recurrent BV include vaginal douching, cigarette smoking, and increased BMI.2,18 Use of an oral contraceptive may have a protective effect against BV recurrence.1

Caring for patients with multiple recurrences of BV can be challenging for many clinicians. Although a few studies have evaluated suppressive therapy for recurrent BV, there are no clear treatment guidelines for multiple recurrent infections. Sobel and colleagues evaluated twice-weekly use of metronidazole gel for 16 weeks and found a significant reduction in BV recurrence during treatment.25 However, there was only a 34% to 37% probability of patients’ remaining clinically cured at seven months posttreatment. Similarly, Reichman et al evaluated suppressive therapy with oral metronidazole, topical boric acid, and metronidazole gel. They found an 88% to 92% initial cure rate, but a 50% failure rate at 36 weeks’ follow-up.26

Management

Studies examining the use of probiotics for the prevention and treatment of BV have yielded mixed results. The theory is that probiotics containing lactobacillus organisms may protect women from infection by maintaining or restoring vaginal pH and preventing adhesion of bacteria to the epithelium of the vaginal walls.27 Despite the conflicting results, no adverse effects have been reported and, as a consequence, many experts recommend probiotics to reduce the risk for recurrent BV. When discussing suppressive therapy options with patients, clinicians should be mindful of the limited data and the clinically unfavorable long-term cure rates demonstrated.

In addition to treatment limitations for recurrent BV, clinicians often find it challenging to effectively address the psychosocial implications of distress, embarrassment, and lack of control that are commonly associated with recurrent BV.28 Beyond its impact on sexual activity, women have also reported refraining from their daily activities out of fear that others around them may detect their vaginal odor. Helping women take a proactive approach in the treatment and prevention of BV may ease some of this distress.

Women with recurrent BV are often eager to hear about measures they can take to reduce their risk for acute and recurrent infection. Patients should be counseled on the association of BV with douching, numerous sexual partners, unprotected sex, increased psychosocial stress, and cigarette smoking.7,18,29-31 Patients may inquire about the potential risk for BV when they use feminine hygiene spray, panty liners or pads, and underwear made from synthetic fabrics; however, one longitudinal study30 showed no association between any of these hygienic behaviors and BV.

Continue for the conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Bacterial vaginosis is a common cause of vaginal discharge in women. Current recommendations for treatment are not very effective, with up to half of women experiencing recurrence. The likelihood of recurrence can result in significant frustration for both patient and clinician. Although recent studies have advanced our understanding of the pathophysiology of BV, further research is needed to develop more effective treatments that reduce recurrence. Addressing modifiable risk factors and considering the use of suppressive and/or probiotic therapy may improve quality of life for women affected by this condition.

REFERENCES

1. Bradshaw CS, Vodstrcil LA, Hocking JS, et al. Recurrence of bacterial vaginosis is significantly associated with posttreatment sexual activities and hormonal contraceptive use. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(6):777-786.

2. Koumans EH, Sternberg M, Bruce C, et al. The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in the United States, 2001-2004: associations with symptoms, sexual behaviors, and reproductive health. Sex Trans Dis. 2007;34(11): 864-869.

3. Allsworth JE, Peipert JF. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis: 2001-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(1):114-120.

4. Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Garland SM, et al. Evaluation of a point-of-care test, BVBlue, and clinical and laboratory criteria for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(3):1304-1308.

5. Swidsinski A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, et al. An adherent Gardnerella vaginalis biofilm persists on the vaginal epithelium after standard therapy with oral metronidazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(1):97.e1-e6.

6. Schwebke JR. Vaginal discharge. In: Klausner JD, Hook EW III, eds. Current Diagnosis & Treatment of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007. http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=369&Sectionid=39914778. Accessed November 11, 2015.

7. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; CDC. Bacterial vaginosis. In: Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):69-72.

8. Hay P. Recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22(1): 82-86.

9. Taylor BD, Darville T, Haggerty CL. Does bacterial vaginosis cause pelvic inflammatory disease? Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(2):117-122.

10. Marrazzo JM, Wiesenfeld HC, Murray PG, et al. Risk factors for cervicitis among women with bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(5):617-624.

11. Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of Gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29(2):297-301.

12. Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, et al. Nonspecific vaginitis: diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983; 74(1):14-22.

13. Girerd PH. Bacterial vaginosis workup (2014). http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/254342-workup. Accessed November 11, 2015.

14. Hoffman BL, Schorge JO, Schaffer JI, et al. Gynecologic infection. In: Hoffman BL, Schorge JO, Schaffer JI, et al, eds. Williams Gynecology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

15. Hainer BL, Gibson MV. Vaginitis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(7):807-815.

16. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists, No. 72: Vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(5):1195-1206.

17. Workowski KA, Berman S; CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12): 1-110.

18. Wilson J. Managing recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(1):8-11.

19. Cook RL, Redondo-Lopez V, Schmitt C, et al. Clinical, microbiological, and biochemical factors in recurrent bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(4):870-877.

20. Boris J, Påhlson C, Larsson P-G. Six years observation after successful treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Infect Dis Obstetr Gynecol. 1997;5(4): 297-302.

21. Mehta SD. Systematic review of randomized trials of treatment of male sexual partners for improved bacterial vaginosis outcomes in women. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(10):822-830.

22. Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(11): 1478-1486.

23. Fethers KA, Fairley CK, Hocking JS, et al. Sexual risk factors and bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(11):1426-1435.

24. Schwebke JR, Desmond RA. A randomized trial of the duration of therapy with metronidazole plus or minus azithromycin for treatment of symptomatic bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):213-219.

25. Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1283-1289.

26. Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(11):732-734.

27. Homayouni A, Bastani P, Ziyadi S, et al. Effects of probiotics on the recurrence of bacterial vaginosis: a review. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014;18(1):79-86.

28. Bilardi JE, Walker S, Temple-Smith M, et al. The burden of bacterial vaginosis: women’s experience of the physical, emotional, sexual and social impact of living with recurrent bacterial vaginosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e74378.

29. Smart S, Singal A, Mindel A. Social and sexual risk factors for bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(1):58-62.

30. Klebanoff MA, Nansel TR, Brotman RM, et al. Personal hygienic behaviors and bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(2):94-99.

31. Nansel TR, Riggs MA, Yu K-F, et al. The association of psychosocial stress and bacterial vaginosis in a longitudinal cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(2):381-386.