User login

Depressed and sick with ‘nothing to live for’

CASE ‘I’ve had enough’

The psychiatry consultation team is asked to evaluate Mr. M, age 76, for a passive death wish and depression 2 months after he was admitted to the hospital after a traumatic fall.

Mr. M has several chronic medical conditions, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease. Within 2 weeks of his admission, he developed Proteus mirabilis pneumonia and persistent respiratory failure requiring tracheostomy. Records indicate that Mr. M has told family and his treatment team, “I’m tired, just let me go.” He then developed antibiotic-induced Clostridium difficile colitis and acute renal failure requiring temporary renal replacement therapy (RRT).

Mr. M’s clinical status improves, allowing his transfer to a transitional unit, where he continues to state, “I have had enough. I’m done.” He asks for the tracheostomy tube to be removed and RRT discontinued. He is treated again for persistent C. difficile colitis and, within 2 weeks, develops hypotension, hypoxia, emesis, and abdominal distension, requiring transfer to the ICU for management of ileus.

He is stabilized with vasopressors and artificial nutritional support by nasogastric tube. Renal function improves, RRT is discontinued, and he is transferred to the general medical floor.

After a few days on the general medical floor, Mr. M develops a urinary tract infection and develops antibiotic-induced acute renal failure requiring re-initiation of RRT. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube is placed for nutrition when he shows little improvement with swallowing exercises. Two days after placing the PEG tube, he develops respiratory failure secondary to a left-sided pneumothorax and is transferred to the ICU for the third time, where he undergoes repeated bronchoscopies and requires pressure support ventilation.

One week later, Mr. M is weaned off the ventilator and transferred to the general medical floor with aggressive respiratory therapy, tube feeding, and RRT. Mr. M’s chart indicates that he expresses an ongoing desire to withdraw RRT, the tracheostomy, and feeding tube.

Which of the following would you consider when assessing Mr. M’s decision-making capacity (DMC)?

a) his ability to understand information relevant to treatment decision-making

b) his ability to appreciate the significance of his diagnoses and treatment options and consequences in the context of his own life circumstances

c) his ability to communicate a preference

d) his ability to reason through the relevant information to weigh the potential costs and benefits of treatment options

e) all of the above

HISTORY Guilt and regret

Mr. M reports a 30-year history of depression that has responded poorly to a variety of medications, outpatient psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy. Before admission, he says, he was adherent to citalopram, 20 mg/d, and buspirone, 30 mg/d. Citalopram is continued throughout his hospitalization, although buspirone was discontinued for unknown reasons during admission.

Mr. M is undergoing hemodialysis during his initial encounter with the psychiatry team. He struggles to communicate clearly because of the tracheostomy but is alert, oriented to person and location, answers questions appropriately, maintains good eye contact, and does not demonstrate any psychomotor abnormalities. He describes his disposition as “tired,” and is on the verge of tears during the interview.

Mr. M denies physical discomfort and states, “I have just had enough. I do not want all of this done.” He clarifies that he is not suicidal and denies a history of suicidal or self-injurious behaviors.

Mr. M describes having low mood, anhedonia, and insomnia to varying degrees throughout his adult life. He also reports feeling guilt and regret about earlier experiences, but does not elaborate. He denies symptoms of panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, mania, or hypomania. He reports an episode of visual hallucinations during an earlier hospitalization, likely a symptom of delirium, but denies any recent visual disturbances.

Mr. M’s thought process is linear and logical, with intact abstract reasoning and no evidence of delusions. Attention and concentration are intact for most of the interview but diminish as he becomes fatigued. Mr. M can describe past treatments in detail and recounts the events leading to this hospitalization.

The authors’ observations

Literature on assessment of DMC recently has centered on the 4-ability model, proposed by Grisso and Appelbaum.1 With this approach, impairment to any of the 4 processes of understanding, appreciation, ability to express a choice, and ability to use reasoning to weigh treatment options could interfere with capacity to make decisions. Few studies have clarified the mechanism and degree to which depression may impair these 4 elements, making capacity assessments in a depressed patient challenging.

Preliminary evidence suggests that depression severity, not the presence of depression, determines the degree to which DMC is impaired, if at all. In several studies, depressed patients did not demonstrate more impaired DMC compared with non-depressed patients based on standardized assessments.2-4 In depressed patients who lack DMC, case reports5-7 and cross-sectional studies8 indicate that appreciation—one’s ability to comprehend the personal relevance of illness and potential consequences of treatments in the context of one’s life—is most often impaired. Other studies suggest that the ability to reason through decision-specific information and weigh the risks and benefits of treatment options is commonly impaired in depressed patients.9,10

Even when a depressed patient demonstrates the 4 elements of DMC, providers might be concerned that the patient’s preferences are skewed by the negative emotions associated with depression.11-13 In such a case, the patient’s expressed wishes might not be consistent with views and priorities that were expressed during an earlier, euthymic period.

Rather than focusing on whether cognitive elements of DMC are impaired, some experts advocate for assessing how depression might lead to “unbalanced” decision-making that is impaired by a patient’s tendency to undervalue positive outcomes and overvalue negative ones.14 Some depressed patients will decide to forego additional medical interventions because they do not see the potential benefits of treatment, view events through a negative lens, and lack hope for the future; however, studies indicate this is not typically the case.15-17

In a study of >2,500 patients age >65 with chronic medical conditions, Garrett et al15 found that those who were depressed communicated a desire for more treatment compared with non-depressed patients. Another study of patients’ wishes for life-sustaining treatment among those who had mild or moderate depression found that most patients did not express a greater desire for life-sustaining medical interventions after their depressive episode remitted. An increased desire for life-sustaining medical interventions occurred only among the most severely depressed patients.16 Similarly, Lee and Ganzini17 found that treatment preferences among patients with mild or moderate depression and serious physical illness were unchanged after the mood disorder was treated.

These findings demonstrate that a clinician charged with assessing DMC must evaluate the severity of a patient’s depression and carefully consider how mood is influencing his (her) perspective and cognitive abilities. It is important to observe how the depressed patient perceives feelings of sadness or hopelessness in the context of decision-making, and how he (she) integrates these feelings when assigning relative value to potential outcomes and alternative treatment options. Because the intensity of depression could vary over time, assessment of the depressed patient’s decision-making abilities must be viewed as a dynamic process.

Clinical application

Recent studies indicate that, although the in-hospital mortality rate for critically ill patients who develop acute renal failure is high, it is variable, ranging from 28% to 90%.18 In one study, patients who required more interventions over the course of a hospital stay (eg, mechanical ventilation, vasopressors) had an in-hospital mortality rate closer to 60% after initiating RRT.19 In a similar trial,20,21 mean survival for critically ill patients with acute renal failure was 32 days from initiation of dialysis; only 27% of these patients were alive 6 months later.21

Given his complicated hospital course, the medical team estimates that Mr. M has a reasonable chance of surviving to discharge, although his longer-term prognosis is poor.

EVALUATION Conflicting preferences

Mr. M expresses reasonable understanding of the medical indications for temporary RRT, respiratory therapy, and enteral tube feedings, and the consequences of withdrawing these interventions. He understands that the primary team recommended ongoing but temporary use of life-sustaining interventions, anticipating that he would recover from his acute medical conditions. Mr. M clearly articulates that he wants to terminate RRT knowing that this would cause a buildup of urea and other toxins, to resume eating by mouth despite the risk of aspiration, and to be allowed to die “naturally.”

Mr. M declines to speak with a clergy member, explaining that he preferred direct contact with God and had reconciled himself to the “consequences” of his actions. He reports having “nothing left to live for” and “nothing left to do.” He says that he is “tired of being a burden” to his wife and son, regrets the way he treated them in the past, and believes they would be better off without him.

Although Mr. M’s abilities to understand, reason, and express a preference are intact, the psychiatry team is concerned that depression could be influencing his perspective, thereby compromising his appreciation for the personal relevance of his request to withdraw life-sustaining treatments. The psychiatrist shares this concern with Mr. M, who voices an understanding that undertreated depression could lead him to make irreversible decisions about his medical treatment that he might not make if he were not depressed; nevertheless, he continues to state that he is “ready” to die. With his permission, the team seeks additional information from Mr. M’s family.

Mr. M’s wife recalls a conversation with her husband 5 years ago in which he said that, were he to become seriously ill, “he would want everything done.” However, she also reports that Mr. M has been expressing a passive death wish “for years,” as he was struggling with chronic medical conditions that led to recurrent hospital admissions.

“He has always been a negative person,” she adds, and confirms that he has been depressed for most of their marriage.

The conflict between Mr. M’s earlier expressed preference for full care and his current wish to withdraw life-sustaining therapies and experience a “natural death” raises significant concern that depression could explain this change in perspective. When asked about this discrepancy, Mr. M admits that he “wanted everything done” in the past, when he was younger and healthier, but his preferences changed as his chronic medical problems progressed.

OUTCOME Better mood, discharge

We encourage Mr. M to continue discussing his treatment preferences with his family, while meeting with the palliative care team to address medical conditions that could be exacerbating depression and to clarify his goals of care. The medical team and Mr. M report feeling relieved when a palliative care consult is suggested, although his wife and son ask that it be delayed until Mr. M is more medically stable. The treatment team acknowledges the competing risks of proceeding too hastily with Mr. M’s request to withdraw life-sustaining treatments because of depression, and of delaying his decision, which could prolong suffering and violate his right to refuse medical treatment.

Mr. M agrees to increase citalopram to 40 mg/d to target depressive symptoms. We monitor Mr. M for treatment response and side effects, to provide ongoing support, to facilitate communication with the medical team, and to evaluate the influence of depression on treatment preferences and decision-making.

As Mr. M is stabilized over the next 3 weeks, he begins to reply, “I’m alive,” when asked about passive death wish. His renal function improves and RRT is discontinued. Mr. M reports a slight improvement in his mood and is discharged to a skilled nursing facility, with plans for closing his tracheostomy.

The authors’ observations

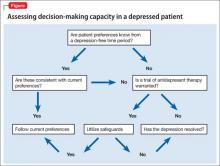

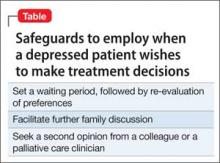

Capacity assessments can be challenging in depressed patients, often because of the uncertain role of features such as hopelessness, anhedonia, and passive death wish in the decision-making process. Depressed patients do not automatically lack DMC, and existing studies suggest that decisions regarding life-saving interventions typically are stable across time. The 4-ability model for capacity assessment is a useful starting point, but additional considerations are warranted in depressed patients with chronic illness (Figure). There is no evidence to date to guide these assessments in chronically depressed or dysthymic patients; therefore additional safeguards may be needed (Table).

In Mr. M’s case, the team’s decision to optimize depression treatment while continuing unwanted life-sustaining therapies led to improved mood and a positive health outcome. In some cases, patients do not respond quickly, if at all, to depression treatment. Also, what constitutes a reasonable attempt to treat depression, or an appropriate delay in decision-making related to life-sustaining therapies, is debatable.

When positive outcomes are not achieved or ethical dilemmas arise, health care providers could experience high moral distress.21 In Mr. M’s case, the consultation team felt moral distress because of the delayed involvement of palliative care, especially because this decision was driven by the family rather than the patient.

Related Resources

• Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA. 2011;306(4):420-427.

• American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. www. aahpm.org.

Drug Brand Names

Buspirone • Buspar Citalopram • Celexa

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing competence to consent to treatment: a guide for physicians and other health professionals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998.

2. Cohen BJ, McGarvey El, Pinkerton RC, et al. Willingness and competence of depressed and schizophrenic inpatients to consent to research. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2004;32(2):134-143.

3. Lapid MI, Rummans TA, Poole KL, et al. Decisional capacity of severely depressed patients requiring electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2003;19(2):67-72.

4. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, Frank E, et al. Competence of depressed patients for consent to research. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(9):1380-1384.

5. Leeman CP. Depression and the right to die. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1999;21(2):112-115.

6. Young EW, Corby JC, Johnson R. Does depression invalidate competence? Consultants’ ethical, psychiatric, and legal considerations. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 1993;2(4):505-515.

7. Halpern J. When concretized emotion-belief complexes derail decision-making capacity. Bioethics. 2012;26(2):108-116.

8. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study. III: abilities of patients to consent to psychiatric and medical treatments. Law Hum Behav. 1995;19(2):149-174.

9. Bean G, Nishisato S, Rector NA, et al. The assessment of competence to make a treatment decision: an empirical approach. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41(2):85-92.

10. Vollmann J, Bauer A, Danker-Hopfe H, et al. Competence of mentally ill patients: a comparative empirical study. Psychol Med. 2003;33(8):1463-1471.

11. Sullivan MD, Youngner SJ. Depression, competence, and the right to refuse lifesaving medical-treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(7):971-978.

12. Meynen G. Depression, possibilities, and competence: a phenomenological perspective. Theor Med Bioeth. 2011;32(3):181-193.

13. Elliott C. Caring about risks. Are severely depressed patients competent to consent to research? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(2):113-116.

14. Bursztajn HJ, Harding HP Jr, Gutheil TG, et al. Beyond cognition: the role of disordered affective states in impairing competence to consent to treatment. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1991;19(4):383-388.

15. Garrett JM, Harris RP, Norburn JK, et al. Life-sustaining treatments during terminal illness: who wants what? J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8(7):361-368.

16. Ganzini L, Lee MA, Heintz RT, et al. The effect of depression treatment on elderly patients’ p for life-sustaining medical therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(11):1631-1636.

17. Lee M, Ganzini L. The effect of recovery from depression on p for life-sustaining therapy in older patients. J Gerontol. 1994;49(1):M15-M21.

18. Metnitz PG, Krenn CG, Steltzer H, et al. Effect of acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy on outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;30(9):2051-2058.

19. Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al; Beginning and Ending Supportive Therapy for the Kidney (BEST Kidney) Investigators. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005;294(7):813-818.

20. The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and p for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA. 1995;274(20):1591-1598.

21. Kälvemark S, Höglund AT, Hansson MG, et al. Living the conflicts-ethical dilemmas and moral distress in the health care system. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(6):1075-1084.

CASE ‘I’ve had enough’

The psychiatry consultation team is asked to evaluate Mr. M, age 76, for a passive death wish and depression 2 months after he was admitted to the hospital after a traumatic fall.

Mr. M has several chronic medical conditions, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease. Within 2 weeks of his admission, he developed Proteus mirabilis pneumonia and persistent respiratory failure requiring tracheostomy. Records indicate that Mr. M has told family and his treatment team, “I’m tired, just let me go.” He then developed antibiotic-induced Clostridium difficile colitis and acute renal failure requiring temporary renal replacement therapy (RRT).

Mr. M’s clinical status improves, allowing his transfer to a transitional unit, where he continues to state, “I have had enough. I’m done.” He asks for the tracheostomy tube to be removed and RRT discontinued. He is treated again for persistent C. difficile colitis and, within 2 weeks, develops hypotension, hypoxia, emesis, and abdominal distension, requiring transfer to the ICU for management of ileus.

He is stabilized with vasopressors and artificial nutritional support by nasogastric tube. Renal function improves, RRT is discontinued, and he is transferred to the general medical floor.

After a few days on the general medical floor, Mr. M develops a urinary tract infection and develops antibiotic-induced acute renal failure requiring re-initiation of RRT. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube is placed for nutrition when he shows little improvement with swallowing exercises. Two days after placing the PEG tube, he develops respiratory failure secondary to a left-sided pneumothorax and is transferred to the ICU for the third time, where he undergoes repeated bronchoscopies and requires pressure support ventilation.

One week later, Mr. M is weaned off the ventilator and transferred to the general medical floor with aggressive respiratory therapy, tube feeding, and RRT. Mr. M’s chart indicates that he expresses an ongoing desire to withdraw RRT, the tracheostomy, and feeding tube.

Which of the following would you consider when assessing Mr. M’s decision-making capacity (DMC)?

a) his ability to understand information relevant to treatment decision-making

b) his ability to appreciate the significance of his diagnoses and treatment options and consequences in the context of his own life circumstances

c) his ability to communicate a preference

d) his ability to reason through the relevant information to weigh the potential costs and benefits of treatment options

e) all of the above

HISTORY Guilt and regret

Mr. M reports a 30-year history of depression that has responded poorly to a variety of medications, outpatient psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy. Before admission, he says, he was adherent to citalopram, 20 mg/d, and buspirone, 30 mg/d. Citalopram is continued throughout his hospitalization, although buspirone was discontinued for unknown reasons during admission.

Mr. M is undergoing hemodialysis during his initial encounter with the psychiatry team. He struggles to communicate clearly because of the tracheostomy but is alert, oriented to person and location, answers questions appropriately, maintains good eye contact, and does not demonstrate any psychomotor abnormalities. He describes his disposition as “tired,” and is on the verge of tears during the interview.

Mr. M denies physical discomfort and states, “I have just had enough. I do not want all of this done.” He clarifies that he is not suicidal and denies a history of suicidal or self-injurious behaviors.

Mr. M describes having low mood, anhedonia, and insomnia to varying degrees throughout his adult life. He also reports feeling guilt and regret about earlier experiences, but does not elaborate. He denies symptoms of panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, mania, or hypomania. He reports an episode of visual hallucinations during an earlier hospitalization, likely a symptom of delirium, but denies any recent visual disturbances.

Mr. M’s thought process is linear and logical, with intact abstract reasoning and no evidence of delusions. Attention and concentration are intact for most of the interview but diminish as he becomes fatigued. Mr. M can describe past treatments in detail and recounts the events leading to this hospitalization.

The authors’ observations

Literature on assessment of DMC recently has centered on the 4-ability model, proposed by Grisso and Appelbaum.1 With this approach, impairment to any of the 4 processes of understanding, appreciation, ability to express a choice, and ability to use reasoning to weigh treatment options could interfere with capacity to make decisions. Few studies have clarified the mechanism and degree to which depression may impair these 4 elements, making capacity assessments in a depressed patient challenging.

Preliminary evidence suggests that depression severity, not the presence of depression, determines the degree to which DMC is impaired, if at all. In several studies, depressed patients did not demonstrate more impaired DMC compared with non-depressed patients based on standardized assessments.2-4 In depressed patients who lack DMC, case reports5-7 and cross-sectional studies8 indicate that appreciation—one’s ability to comprehend the personal relevance of illness and potential consequences of treatments in the context of one’s life—is most often impaired. Other studies suggest that the ability to reason through decision-specific information and weigh the risks and benefits of treatment options is commonly impaired in depressed patients.9,10

Even when a depressed patient demonstrates the 4 elements of DMC, providers might be concerned that the patient’s preferences are skewed by the negative emotions associated with depression.11-13 In such a case, the patient’s expressed wishes might not be consistent with views and priorities that were expressed during an earlier, euthymic period.

Rather than focusing on whether cognitive elements of DMC are impaired, some experts advocate for assessing how depression might lead to “unbalanced” decision-making that is impaired by a patient’s tendency to undervalue positive outcomes and overvalue negative ones.14 Some depressed patients will decide to forego additional medical interventions because they do not see the potential benefits of treatment, view events through a negative lens, and lack hope for the future; however, studies indicate this is not typically the case.15-17

In a study of >2,500 patients age >65 with chronic medical conditions, Garrett et al15 found that those who were depressed communicated a desire for more treatment compared with non-depressed patients. Another study of patients’ wishes for life-sustaining treatment among those who had mild or moderate depression found that most patients did not express a greater desire for life-sustaining medical interventions after their depressive episode remitted. An increased desire for life-sustaining medical interventions occurred only among the most severely depressed patients.16 Similarly, Lee and Ganzini17 found that treatment preferences among patients with mild or moderate depression and serious physical illness were unchanged after the mood disorder was treated.

These findings demonstrate that a clinician charged with assessing DMC must evaluate the severity of a patient’s depression and carefully consider how mood is influencing his (her) perspective and cognitive abilities. It is important to observe how the depressed patient perceives feelings of sadness or hopelessness in the context of decision-making, and how he (she) integrates these feelings when assigning relative value to potential outcomes and alternative treatment options. Because the intensity of depression could vary over time, assessment of the depressed patient’s decision-making abilities must be viewed as a dynamic process.

Clinical application

Recent studies indicate that, although the in-hospital mortality rate for critically ill patients who develop acute renal failure is high, it is variable, ranging from 28% to 90%.18 In one study, patients who required more interventions over the course of a hospital stay (eg, mechanical ventilation, vasopressors) had an in-hospital mortality rate closer to 60% after initiating RRT.19 In a similar trial,20,21 mean survival for critically ill patients with acute renal failure was 32 days from initiation of dialysis; only 27% of these patients were alive 6 months later.21

Given his complicated hospital course, the medical team estimates that Mr. M has a reasonable chance of surviving to discharge, although his longer-term prognosis is poor.

EVALUATION Conflicting preferences

Mr. M expresses reasonable understanding of the medical indications for temporary RRT, respiratory therapy, and enteral tube feedings, and the consequences of withdrawing these interventions. He understands that the primary team recommended ongoing but temporary use of life-sustaining interventions, anticipating that he would recover from his acute medical conditions. Mr. M clearly articulates that he wants to terminate RRT knowing that this would cause a buildup of urea and other toxins, to resume eating by mouth despite the risk of aspiration, and to be allowed to die “naturally.”

Mr. M declines to speak with a clergy member, explaining that he preferred direct contact with God and had reconciled himself to the “consequences” of his actions. He reports having “nothing left to live for” and “nothing left to do.” He says that he is “tired of being a burden” to his wife and son, regrets the way he treated them in the past, and believes they would be better off without him.

Although Mr. M’s abilities to understand, reason, and express a preference are intact, the psychiatry team is concerned that depression could be influencing his perspective, thereby compromising his appreciation for the personal relevance of his request to withdraw life-sustaining treatments. The psychiatrist shares this concern with Mr. M, who voices an understanding that undertreated depression could lead him to make irreversible decisions about his medical treatment that he might not make if he were not depressed; nevertheless, he continues to state that he is “ready” to die. With his permission, the team seeks additional information from Mr. M’s family.

Mr. M’s wife recalls a conversation with her husband 5 years ago in which he said that, were he to become seriously ill, “he would want everything done.” However, she also reports that Mr. M has been expressing a passive death wish “for years,” as he was struggling with chronic medical conditions that led to recurrent hospital admissions.

“He has always been a negative person,” she adds, and confirms that he has been depressed for most of their marriage.

The conflict between Mr. M’s earlier expressed preference for full care and his current wish to withdraw life-sustaining therapies and experience a “natural death” raises significant concern that depression could explain this change in perspective. When asked about this discrepancy, Mr. M admits that he “wanted everything done” in the past, when he was younger and healthier, but his preferences changed as his chronic medical problems progressed.

OUTCOME Better mood, discharge

We encourage Mr. M to continue discussing his treatment preferences with his family, while meeting with the palliative care team to address medical conditions that could be exacerbating depression and to clarify his goals of care. The medical team and Mr. M report feeling relieved when a palliative care consult is suggested, although his wife and son ask that it be delayed until Mr. M is more medically stable. The treatment team acknowledges the competing risks of proceeding too hastily with Mr. M’s request to withdraw life-sustaining treatments because of depression, and of delaying his decision, which could prolong suffering and violate his right to refuse medical treatment.

Mr. M agrees to increase citalopram to 40 mg/d to target depressive symptoms. We monitor Mr. M for treatment response and side effects, to provide ongoing support, to facilitate communication with the medical team, and to evaluate the influence of depression on treatment preferences and decision-making.

As Mr. M is stabilized over the next 3 weeks, he begins to reply, “I’m alive,” when asked about passive death wish. His renal function improves and RRT is discontinued. Mr. M reports a slight improvement in his mood and is discharged to a skilled nursing facility, with plans for closing his tracheostomy.

The authors’ observations

Capacity assessments can be challenging in depressed patients, often because of the uncertain role of features such as hopelessness, anhedonia, and passive death wish in the decision-making process. Depressed patients do not automatically lack DMC, and existing studies suggest that decisions regarding life-saving interventions typically are stable across time. The 4-ability model for capacity assessment is a useful starting point, but additional considerations are warranted in depressed patients with chronic illness (Figure). There is no evidence to date to guide these assessments in chronically depressed or dysthymic patients; therefore additional safeguards may be needed (Table).

In Mr. M’s case, the team’s decision to optimize depression treatment while continuing unwanted life-sustaining therapies led to improved mood and a positive health outcome. In some cases, patients do not respond quickly, if at all, to depression treatment. Also, what constitutes a reasonable attempt to treat depression, or an appropriate delay in decision-making related to life-sustaining therapies, is debatable.

When positive outcomes are not achieved or ethical dilemmas arise, health care providers could experience high moral distress.21 In Mr. M’s case, the consultation team felt moral distress because of the delayed involvement of palliative care, especially because this decision was driven by the family rather than the patient.

Related Resources

• Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA. 2011;306(4):420-427.

• American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. www. aahpm.org.

Drug Brand Names

Buspirone • Buspar Citalopram • Celexa

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE ‘I’ve had enough’

The psychiatry consultation team is asked to evaluate Mr. M, age 76, for a passive death wish and depression 2 months after he was admitted to the hospital after a traumatic fall.

Mr. M has several chronic medical conditions, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease. Within 2 weeks of his admission, he developed Proteus mirabilis pneumonia and persistent respiratory failure requiring tracheostomy. Records indicate that Mr. M has told family and his treatment team, “I’m tired, just let me go.” He then developed antibiotic-induced Clostridium difficile colitis and acute renal failure requiring temporary renal replacement therapy (RRT).

Mr. M’s clinical status improves, allowing his transfer to a transitional unit, where he continues to state, “I have had enough. I’m done.” He asks for the tracheostomy tube to be removed and RRT discontinued. He is treated again for persistent C. difficile colitis and, within 2 weeks, develops hypotension, hypoxia, emesis, and abdominal distension, requiring transfer to the ICU for management of ileus.

He is stabilized with vasopressors and artificial nutritional support by nasogastric tube. Renal function improves, RRT is discontinued, and he is transferred to the general medical floor.

After a few days on the general medical floor, Mr. M develops a urinary tract infection and develops antibiotic-induced acute renal failure requiring re-initiation of RRT. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube is placed for nutrition when he shows little improvement with swallowing exercises. Two days after placing the PEG tube, he develops respiratory failure secondary to a left-sided pneumothorax and is transferred to the ICU for the third time, where he undergoes repeated bronchoscopies and requires pressure support ventilation.

One week later, Mr. M is weaned off the ventilator and transferred to the general medical floor with aggressive respiratory therapy, tube feeding, and RRT. Mr. M’s chart indicates that he expresses an ongoing desire to withdraw RRT, the tracheostomy, and feeding tube.

Which of the following would you consider when assessing Mr. M’s decision-making capacity (DMC)?

a) his ability to understand information relevant to treatment decision-making

b) his ability to appreciate the significance of his diagnoses and treatment options and consequences in the context of his own life circumstances

c) his ability to communicate a preference

d) his ability to reason through the relevant information to weigh the potential costs and benefits of treatment options

e) all of the above

HISTORY Guilt and regret

Mr. M reports a 30-year history of depression that has responded poorly to a variety of medications, outpatient psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy. Before admission, he says, he was adherent to citalopram, 20 mg/d, and buspirone, 30 mg/d. Citalopram is continued throughout his hospitalization, although buspirone was discontinued for unknown reasons during admission.

Mr. M is undergoing hemodialysis during his initial encounter with the psychiatry team. He struggles to communicate clearly because of the tracheostomy but is alert, oriented to person and location, answers questions appropriately, maintains good eye contact, and does not demonstrate any psychomotor abnormalities. He describes his disposition as “tired,” and is on the verge of tears during the interview.

Mr. M denies physical discomfort and states, “I have just had enough. I do not want all of this done.” He clarifies that he is not suicidal and denies a history of suicidal or self-injurious behaviors.

Mr. M describes having low mood, anhedonia, and insomnia to varying degrees throughout his adult life. He also reports feeling guilt and regret about earlier experiences, but does not elaborate. He denies symptoms of panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, mania, or hypomania. He reports an episode of visual hallucinations during an earlier hospitalization, likely a symptom of delirium, but denies any recent visual disturbances.

Mr. M’s thought process is linear and logical, with intact abstract reasoning and no evidence of delusions. Attention and concentration are intact for most of the interview but diminish as he becomes fatigued. Mr. M can describe past treatments in detail and recounts the events leading to this hospitalization.

The authors’ observations

Literature on assessment of DMC recently has centered on the 4-ability model, proposed by Grisso and Appelbaum.1 With this approach, impairment to any of the 4 processes of understanding, appreciation, ability to express a choice, and ability to use reasoning to weigh treatment options could interfere with capacity to make decisions. Few studies have clarified the mechanism and degree to which depression may impair these 4 elements, making capacity assessments in a depressed patient challenging.

Preliminary evidence suggests that depression severity, not the presence of depression, determines the degree to which DMC is impaired, if at all. In several studies, depressed patients did not demonstrate more impaired DMC compared with non-depressed patients based on standardized assessments.2-4 In depressed patients who lack DMC, case reports5-7 and cross-sectional studies8 indicate that appreciation—one’s ability to comprehend the personal relevance of illness and potential consequences of treatments in the context of one’s life—is most often impaired. Other studies suggest that the ability to reason through decision-specific information and weigh the risks and benefits of treatment options is commonly impaired in depressed patients.9,10

Even when a depressed patient demonstrates the 4 elements of DMC, providers might be concerned that the patient’s preferences are skewed by the negative emotions associated with depression.11-13 In such a case, the patient’s expressed wishes might not be consistent with views and priorities that were expressed during an earlier, euthymic period.

Rather than focusing on whether cognitive elements of DMC are impaired, some experts advocate for assessing how depression might lead to “unbalanced” decision-making that is impaired by a patient’s tendency to undervalue positive outcomes and overvalue negative ones.14 Some depressed patients will decide to forego additional medical interventions because they do not see the potential benefits of treatment, view events through a negative lens, and lack hope for the future; however, studies indicate this is not typically the case.15-17

In a study of >2,500 patients age >65 with chronic medical conditions, Garrett et al15 found that those who were depressed communicated a desire for more treatment compared with non-depressed patients. Another study of patients’ wishes for life-sustaining treatment among those who had mild or moderate depression found that most patients did not express a greater desire for life-sustaining medical interventions after their depressive episode remitted. An increased desire for life-sustaining medical interventions occurred only among the most severely depressed patients.16 Similarly, Lee and Ganzini17 found that treatment preferences among patients with mild or moderate depression and serious physical illness were unchanged after the mood disorder was treated.

These findings demonstrate that a clinician charged with assessing DMC must evaluate the severity of a patient’s depression and carefully consider how mood is influencing his (her) perspective and cognitive abilities. It is important to observe how the depressed patient perceives feelings of sadness or hopelessness in the context of decision-making, and how he (she) integrates these feelings when assigning relative value to potential outcomes and alternative treatment options. Because the intensity of depression could vary over time, assessment of the depressed patient’s decision-making abilities must be viewed as a dynamic process.

Clinical application

Recent studies indicate that, although the in-hospital mortality rate for critically ill patients who develop acute renal failure is high, it is variable, ranging from 28% to 90%.18 In one study, patients who required more interventions over the course of a hospital stay (eg, mechanical ventilation, vasopressors) had an in-hospital mortality rate closer to 60% after initiating RRT.19 In a similar trial,20,21 mean survival for critically ill patients with acute renal failure was 32 days from initiation of dialysis; only 27% of these patients were alive 6 months later.21

Given his complicated hospital course, the medical team estimates that Mr. M has a reasonable chance of surviving to discharge, although his longer-term prognosis is poor.

EVALUATION Conflicting preferences

Mr. M expresses reasonable understanding of the medical indications for temporary RRT, respiratory therapy, and enteral tube feedings, and the consequences of withdrawing these interventions. He understands that the primary team recommended ongoing but temporary use of life-sustaining interventions, anticipating that he would recover from his acute medical conditions. Mr. M clearly articulates that he wants to terminate RRT knowing that this would cause a buildup of urea and other toxins, to resume eating by mouth despite the risk of aspiration, and to be allowed to die “naturally.”

Mr. M declines to speak with a clergy member, explaining that he preferred direct contact with God and had reconciled himself to the “consequences” of his actions. He reports having “nothing left to live for” and “nothing left to do.” He says that he is “tired of being a burden” to his wife and son, regrets the way he treated them in the past, and believes they would be better off without him.

Although Mr. M’s abilities to understand, reason, and express a preference are intact, the psychiatry team is concerned that depression could be influencing his perspective, thereby compromising his appreciation for the personal relevance of his request to withdraw life-sustaining treatments. The psychiatrist shares this concern with Mr. M, who voices an understanding that undertreated depression could lead him to make irreversible decisions about his medical treatment that he might not make if he were not depressed; nevertheless, he continues to state that he is “ready” to die. With his permission, the team seeks additional information from Mr. M’s family.

Mr. M’s wife recalls a conversation with her husband 5 years ago in which he said that, were he to become seriously ill, “he would want everything done.” However, she also reports that Mr. M has been expressing a passive death wish “for years,” as he was struggling with chronic medical conditions that led to recurrent hospital admissions.

“He has always been a negative person,” she adds, and confirms that he has been depressed for most of their marriage.

The conflict between Mr. M’s earlier expressed preference for full care and his current wish to withdraw life-sustaining therapies and experience a “natural death” raises significant concern that depression could explain this change in perspective. When asked about this discrepancy, Mr. M admits that he “wanted everything done” in the past, when he was younger and healthier, but his preferences changed as his chronic medical problems progressed.

OUTCOME Better mood, discharge

We encourage Mr. M to continue discussing his treatment preferences with his family, while meeting with the palliative care team to address medical conditions that could be exacerbating depression and to clarify his goals of care. The medical team and Mr. M report feeling relieved when a palliative care consult is suggested, although his wife and son ask that it be delayed until Mr. M is more medically stable. The treatment team acknowledges the competing risks of proceeding too hastily with Mr. M’s request to withdraw life-sustaining treatments because of depression, and of delaying his decision, which could prolong suffering and violate his right to refuse medical treatment.

Mr. M agrees to increase citalopram to 40 mg/d to target depressive symptoms. We monitor Mr. M for treatment response and side effects, to provide ongoing support, to facilitate communication with the medical team, and to evaluate the influence of depression on treatment preferences and decision-making.

As Mr. M is stabilized over the next 3 weeks, he begins to reply, “I’m alive,” when asked about passive death wish. His renal function improves and RRT is discontinued. Mr. M reports a slight improvement in his mood and is discharged to a skilled nursing facility, with plans for closing his tracheostomy.

The authors’ observations

Capacity assessments can be challenging in depressed patients, often because of the uncertain role of features such as hopelessness, anhedonia, and passive death wish in the decision-making process. Depressed patients do not automatically lack DMC, and existing studies suggest that decisions regarding life-saving interventions typically are stable across time. The 4-ability model for capacity assessment is a useful starting point, but additional considerations are warranted in depressed patients with chronic illness (Figure). There is no evidence to date to guide these assessments in chronically depressed or dysthymic patients; therefore additional safeguards may be needed (Table).

In Mr. M’s case, the team’s decision to optimize depression treatment while continuing unwanted life-sustaining therapies led to improved mood and a positive health outcome. In some cases, patients do not respond quickly, if at all, to depression treatment. Also, what constitutes a reasonable attempt to treat depression, or an appropriate delay in decision-making related to life-sustaining therapies, is debatable.

When positive outcomes are not achieved or ethical dilemmas arise, health care providers could experience high moral distress.21 In Mr. M’s case, the consultation team felt moral distress because of the delayed involvement of palliative care, especially because this decision was driven by the family rather than the patient.

Related Resources

• Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA. 2011;306(4):420-427.

• American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. www. aahpm.org.

Drug Brand Names

Buspirone • Buspar Citalopram • Celexa

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing competence to consent to treatment: a guide for physicians and other health professionals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998.

2. Cohen BJ, McGarvey El, Pinkerton RC, et al. Willingness and competence of depressed and schizophrenic inpatients to consent to research. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2004;32(2):134-143.

3. Lapid MI, Rummans TA, Poole KL, et al. Decisional capacity of severely depressed patients requiring electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2003;19(2):67-72.

4. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, Frank E, et al. Competence of depressed patients for consent to research. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(9):1380-1384.

5. Leeman CP. Depression and the right to die. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1999;21(2):112-115.

6. Young EW, Corby JC, Johnson R. Does depression invalidate competence? Consultants’ ethical, psychiatric, and legal considerations. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 1993;2(4):505-515.

7. Halpern J. When concretized emotion-belief complexes derail decision-making capacity. Bioethics. 2012;26(2):108-116.

8. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study. III: abilities of patients to consent to psychiatric and medical treatments. Law Hum Behav. 1995;19(2):149-174.

9. Bean G, Nishisato S, Rector NA, et al. The assessment of competence to make a treatment decision: an empirical approach. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41(2):85-92.

10. Vollmann J, Bauer A, Danker-Hopfe H, et al. Competence of mentally ill patients: a comparative empirical study. Psychol Med. 2003;33(8):1463-1471.

11. Sullivan MD, Youngner SJ. Depression, competence, and the right to refuse lifesaving medical-treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(7):971-978.

12. Meynen G. Depression, possibilities, and competence: a phenomenological perspective. Theor Med Bioeth. 2011;32(3):181-193.

13. Elliott C. Caring about risks. Are severely depressed patients competent to consent to research? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(2):113-116.

14. Bursztajn HJ, Harding HP Jr, Gutheil TG, et al. Beyond cognition: the role of disordered affective states in impairing competence to consent to treatment. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1991;19(4):383-388.

15. Garrett JM, Harris RP, Norburn JK, et al. Life-sustaining treatments during terminal illness: who wants what? J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8(7):361-368.

16. Ganzini L, Lee MA, Heintz RT, et al. The effect of depression treatment on elderly patients’ p for life-sustaining medical therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(11):1631-1636.

17. Lee M, Ganzini L. The effect of recovery from depression on p for life-sustaining therapy in older patients. J Gerontol. 1994;49(1):M15-M21.

18. Metnitz PG, Krenn CG, Steltzer H, et al. Effect of acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy on outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;30(9):2051-2058.

19. Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al; Beginning and Ending Supportive Therapy for the Kidney (BEST Kidney) Investigators. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005;294(7):813-818.

20. The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and p for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA. 1995;274(20):1591-1598.

21. Kälvemark S, Höglund AT, Hansson MG, et al. Living the conflicts-ethical dilemmas and moral distress in the health care system. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(6):1075-1084.

1. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing competence to consent to treatment: a guide for physicians and other health professionals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998.

2. Cohen BJ, McGarvey El, Pinkerton RC, et al. Willingness and competence of depressed and schizophrenic inpatients to consent to research. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2004;32(2):134-143.

3. Lapid MI, Rummans TA, Poole KL, et al. Decisional capacity of severely depressed patients requiring electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2003;19(2):67-72.

4. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, Frank E, et al. Competence of depressed patients for consent to research. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(9):1380-1384.

5. Leeman CP. Depression and the right to die. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1999;21(2):112-115.

6. Young EW, Corby JC, Johnson R. Does depression invalidate competence? Consultants’ ethical, psychiatric, and legal considerations. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 1993;2(4):505-515.

7. Halpern J. When concretized emotion-belief complexes derail decision-making capacity. Bioethics. 2012;26(2):108-116.

8. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study. III: abilities of patients to consent to psychiatric and medical treatments. Law Hum Behav. 1995;19(2):149-174.

9. Bean G, Nishisato S, Rector NA, et al. The assessment of competence to make a treatment decision: an empirical approach. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41(2):85-92.

10. Vollmann J, Bauer A, Danker-Hopfe H, et al. Competence of mentally ill patients: a comparative empirical study. Psychol Med. 2003;33(8):1463-1471.

11. Sullivan MD, Youngner SJ. Depression, competence, and the right to refuse lifesaving medical-treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(7):971-978.

12. Meynen G. Depression, possibilities, and competence: a phenomenological perspective. Theor Med Bioeth. 2011;32(3):181-193.

13. Elliott C. Caring about risks. Are severely depressed patients competent to consent to research? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(2):113-116.

14. Bursztajn HJ, Harding HP Jr, Gutheil TG, et al. Beyond cognition: the role of disordered affective states in impairing competence to consent to treatment. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1991;19(4):383-388.

15. Garrett JM, Harris RP, Norburn JK, et al. Life-sustaining treatments during terminal illness: who wants what? J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8(7):361-368.

16. Ganzini L, Lee MA, Heintz RT, et al. The effect of depression treatment on elderly patients’ p for life-sustaining medical therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(11):1631-1636.

17. Lee M, Ganzini L. The effect of recovery from depression on p for life-sustaining therapy in older patients. J Gerontol. 1994;49(1):M15-M21.

18. Metnitz PG, Krenn CG, Steltzer H, et al. Effect of acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy on outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;30(9):2051-2058.

19. Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al; Beginning and Ending Supportive Therapy for the Kidney (BEST Kidney) Investigators. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005;294(7):813-818.

20. The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and p for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA. 1995;274(20):1591-1598.

21. Kälvemark S, Höglund AT, Hansson MG, et al. Living the conflicts-ethical dilemmas and moral distress in the health care system. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(6):1075-1084.

MEAN: How to manage a child who bullies

A survey from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development estimated that 20% of 6th through 10th graders admitted to bullying their classmates.1 In addition to an increased risk for personal injury, bullied children are more likely to report low self-esteem and emotional problems2 and often experience loneliness.1 In contrast, children who bully suffer in their school performance1 and are more likely to engage in drug use3 and violence4 later in life. Child psychiatrists often see both bullies and their victims.

Evidence-based recommendations are available to help educators improve the school climate5 and identify children who are at an increased risk for bullying,6 but research supporting specific clinical strategies for managing a child who bullies is limited. Establishing rapport and engaging a bully often is challenging; these difficulties further complicate assessment and successful management of such children.

We present the mnemonic MEAN to help clinicians assess and understand children who bully.

Model. Discuss, demonstrate, and practice models of alternative social skills and behaviors, including active listening, being open to others’ views, accepting failure, controlling impulses, developing problem-solving techniques, and treating others with respect.

Empathize. Encourage children who bully to explore their feelings about themselves—which may uncover poor self-esteem, anger, or guilt—and acknowledge the hurt they cause others by bullying. Focusing on the pain they inflict on others in the context of personal experiences of pain that likely is driving their aggression may enable bullies to empathize with their victims.

Assess. Help the bully assess the costs and benefits of his or her behavior. Point out what the bully stands to gain from ending his or her aggressive behavior, which likely already has resulted in lost recesses, after school detentions, missed sports practices, and the loss of privileges at home. Most importantly, assess and treat any underlying psychopathology, including mood and anxiety disorders.

Nurture. Aid the bully in identifying his or her prosocial strengths to build self-esteem and thereby reduce the need to commit aggressive acts as a means of gaining a sense of control or personal security. Disarm the child with your genuine concern for his or her well-being.

Using these psychotherapeutic techniques may enhance establishing rapport with a child who bullies and may improve outcomes.

Disclosures

Dr. Kepple reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Madaan receives grant or research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer Inc., and Shire.

1. Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, et al. Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2094-2100.

2. Guerra NG, Williams KR, Sadek S. Understanding bullying and victimization during childhood and adolescence: a mixed methods study. Child Dev. 2011;82(1):295-310.

3. Tharp-Taylor S, Haviland A, D’Amico EJ. Victimization from mental and physical bullying and substance use in early adolescence. Addict Behav. 2009;34(6-7):561-567.

4. Duke NN, Pettingell SL, McMorris BJ, et al. Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e778-e786.

5. Olweus D, Limber SP. Bullying in school: evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(1):124-134.

6. Jansen DE, Veenstra R, Ormel J, et al. Early risk factors for being a bully, victim, or bully/victim in late elementary and early secondary education. The longitudinal TRAILS study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:440.-

A survey from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development estimated that 20% of 6th through 10th graders admitted to bullying their classmates.1 In addition to an increased risk for personal injury, bullied children are more likely to report low self-esteem and emotional problems2 and often experience loneliness.1 In contrast, children who bully suffer in their school performance1 and are more likely to engage in drug use3 and violence4 later in life. Child psychiatrists often see both bullies and their victims.

Evidence-based recommendations are available to help educators improve the school climate5 and identify children who are at an increased risk for bullying,6 but research supporting specific clinical strategies for managing a child who bullies is limited. Establishing rapport and engaging a bully often is challenging; these difficulties further complicate assessment and successful management of such children.

We present the mnemonic MEAN to help clinicians assess and understand children who bully.

Model. Discuss, demonstrate, and practice models of alternative social skills and behaviors, including active listening, being open to others’ views, accepting failure, controlling impulses, developing problem-solving techniques, and treating others with respect.

Empathize. Encourage children who bully to explore their feelings about themselves—which may uncover poor self-esteem, anger, or guilt—and acknowledge the hurt they cause others by bullying. Focusing on the pain they inflict on others in the context of personal experiences of pain that likely is driving their aggression may enable bullies to empathize with their victims.

Assess. Help the bully assess the costs and benefits of his or her behavior. Point out what the bully stands to gain from ending his or her aggressive behavior, which likely already has resulted in lost recesses, after school detentions, missed sports practices, and the loss of privileges at home. Most importantly, assess and treat any underlying psychopathology, including mood and anxiety disorders.

Nurture. Aid the bully in identifying his or her prosocial strengths to build self-esteem and thereby reduce the need to commit aggressive acts as a means of gaining a sense of control or personal security. Disarm the child with your genuine concern for his or her well-being.

Using these psychotherapeutic techniques may enhance establishing rapport with a child who bullies and may improve outcomes.

Disclosures

Dr. Kepple reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Madaan receives grant or research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer Inc., and Shire.

A survey from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development estimated that 20% of 6th through 10th graders admitted to bullying their classmates.1 In addition to an increased risk for personal injury, bullied children are more likely to report low self-esteem and emotional problems2 and often experience loneliness.1 In contrast, children who bully suffer in their school performance1 and are more likely to engage in drug use3 and violence4 later in life. Child psychiatrists often see both bullies and their victims.

Evidence-based recommendations are available to help educators improve the school climate5 and identify children who are at an increased risk for bullying,6 but research supporting specific clinical strategies for managing a child who bullies is limited. Establishing rapport and engaging a bully often is challenging; these difficulties further complicate assessment and successful management of such children.

We present the mnemonic MEAN to help clinicians assess and understand children who bully.

Model. Discuss, demonstrate, and practice models of alternative social skills and behaviors, including active listening, being open to others’ views, accepting failure, controlling impulses, developing problem-solving techniques, and treating others with respect.

Empathize. Encourage children who bully to explore their feelings about themselves—which may uncover poor self-esteem, anger, or guilt—and acknowledge the hurt they cause others by bullying. Focusing on the pain they inflict on others in the context of personal experiences of pain that likely is driving their aggression may enable bullies to empathize with their victims.

Assess. Help the bully assess the costs and benefits of his or her behavior. Point out what the bully stands to gain from ending his or her aggressive behavior, which likely already has resulted in lost recesses, after school detentions, missed sports practices, and the loss of privileges at home. Most importantly, assess and treat any underlying psychopathology, including mood and anxiety disorders.

Nurture. Aid the bully in identifying his or her prosocial strengths to build self-esteem and thereby reduce the need to commit aggressive acts as a means of gaining a sense of control or personal security. Disarm the child with your genuine concern for his or her well-being.

Using these psychotherapeutic techniques may enhance establishing rapport with a child who bullies and may improve outcomes.

Disclosures

Dr. Kepple reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Madaan receives grant or research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer Inc., and Shire.

1. Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, et al. Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2094-2100.

2. Guerra NG, Williams KR, Sadek S. Understanding bullying and victimization during childhood and adolescence: a mixed methods study. Child Dev. 2011;82(1):295-310.

3. Tharp-Taylor S, Haviland A, D’Amico EJ. Victimization from mental and physical bullying and substance use in early adolescence. Addict Behav. 2009;34(6-7):561-567.

4. Duke NN, Pettingell SL, McMorris BJ, et al. Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e778-e786.

5. Olweus D, Limber SP. Bullying in school: evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(1):124-134.

6. Jansen DE, Veenstra R, Ormel J, et al. Early risk factors for being a bully, victim, or bully/victim in late elementary and early secondary education. The longitudinal TRAILS study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:440.-

1. Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, et al. Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2094-2100.

2. Guerra NG, Williams KR, Sadek S. Understanding bullying and victimization during childhood and adolescence: a mixed methods study. Child Dev. 2011;82(1):295-310.

3. Tharp-Taylor S, Haviland A, D’Amico EJ. Victimization from mental and physical bullying and substance use in early adolescence. Addict Behav. 2009;34(6-7):561-567.

4. Duke NN, Pettingell SL, McMorris BJ, et al. Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e778-e786.

5. Olweus D, Limber SP. Bullying in school: evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(1):124-134.

6. Jansen DE, Veenstra R, Ormel J, et al. Early risk factors for being a bully, victim, or bully/victim in late elementary and early secondary education. The longitudinal TRAILS study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:440.-