User login

How coffee and cigarettes can affect the response to psychopharmacotherapy

When a patient who smokes enters a tobacco-free medical facility and has access to caffeinated beverages, he (she) might experience toxicity to many pharmaceuticals and caffeine. Similarly, if a patient is discharged from a smoke-free environment with a newly adjusted medication regimen and resumes smoking or caffeine consumption, alterations in enzyme activity might reduce therapeutic efficacy of prescribed medicines. These effects are a result of alterations in the hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme system.

Taking a careful history of tobacco and caffeine use, and knowing the effects that these substances will have on specific medications, will help guide treatment and management decisions.

The role of CYP enzymes

CYP hepatic enzymes detoxify a variety of environmental agents into water-soluble compounds that are excreted in urine. CYP1A2 metabolizes 20% of drugs handled by the CYP system and comprises 13% of all the CYP enzymes expressed in the liver. The wide interindividual variation in CYP1A2 enzyme activity is influenced by a combination of genetic, epigenetic, ethnic, and environmental variables.1

Influence of tobacco on CYP

The polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in tobacco smoke induce CYP1A2 and CYP2B6 hepatic enzymes.2 Smokers exhibit increased activity of these enzymes, which results in faster clearance of many drugs, lower concentrations in blood, and diminished clinical response. The Table lists psychotropic medicines that are metabolized by CYP1A2 and CYP2B6. Co-administration of these substrates could decrease the elimination rate of other drugs also metabolized by CYP1A2. Nicotine in tobacco or in nicotine replacement therapies does not play a role in inducing CYP enzymes.

Psychiatric patients smoke at a higher rate than the general population.2 One study found that approximately 70% of patients with schizophrenia and as many as 45% of those with bipolar disorder smoke enough cigarettes (7 to 20 a day) to induce CYP1A2 and CYP2B6 activity.2 Patients who smoke and are given clozapine, haloperidol, or olanzapine show a lower serum concentration than non-smokers; in fact, the clozapine level can be reduced as much as 2.4-fold.2-5 Subsequently, patients can experience diminished clinical response to these 3 psychotropics.3

The turnover time for CYP1A2 is rapid— approximately 3 days—and a new CYP1A2 steady state activity is reached after approximately 1 week,4 which is important to remember when managing inpatients in a smoke-free facility. During acute hospitalization, patients could experience drug toxicity if the outpatient dosage is maintained.5

When they resume smoking after being discharged on a stabilized dosage of any of the medications listed in the Table, previous enzyme activity rebounds and might reduce the drug level, potentially leading to inadequate clinical response.

Caffeine and other substances

Asking about the patient’s caffeine intake is necessary because consumption of coffee is prevalent among smokers, and caffeine is metabolized by CYP1A2. Smokers need to consume as much as 4 times the amount of caffeine as non-smokers to achieve a similar caffeine serum concentration.2 Caffeine can form an insoluble precipitate with antipsychotic medication in the gut, which decreases absorption. The interaction between smoking-related induction of CYP1A2 enzymes and forced smoking cessation during hospitalization, with ongoing caffeine consumption, could lead to caffeine toxicity.4,5

Other common inducers of CYP1A2 are insulin, cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, and charcoal-grilled meat. Also, cumin and turmeric inhibit CYP1A2 activity, which might explain an ethnic difference in drug tolerance across population groups. Additionally, certain genetic polymorphisms, in specific ethnic distributions, alter the potential for tobacco smoke to induce CYP1A2.6

Some of these polymorphisms can be genotyped for clinical application.3

Asking about a patient’s tobacco and caffeine use and understanding their interactions with specific medications provides guidance when prescribing antipsychotic medications and adjusting dosage for inpatients and during clinical follow-up care.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Wang B, Zhou SF. Synthetic and natural compounds that interact with human cytochrome P450 1A2 and implications in drug development. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(31):4066-4218.

2. Lucas C, Martin J. Smoking and drug interactions. Australian Prescriber. 2013;36(3):102-104.

3. Eap CB, Bender S, Jaquenoud Sirot E, et al. Nonresponse to clozapine and ultrarapid CYP1A2 activity: clinical data and analysis of CYP1A2 gene. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004; 24(2):214-209.

4. Faber MS, Fuhr U. Time response of cytochrome P450 1A2 activity on cessation of heavy smoking. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76(2):178-184.

5. Berk M, Ng F, Wang WV, et al. Going up in smoke: tobacco smoking is associated with worse treatment outcomes in mania. J Affect Disord. 2008;110(1-2):126-134.

6. Zhou SF, Yang LP, Zhou ZW, et al. Insights into the substrate specificity, inhibitors, regulation, and polymorphisms and the clinical impact of human cytochrome P450 1A2. AAPS. 2009;11(3):481-494.

When a patient who smokes enters a tobacco-free medical facility and has access to caffeinated beverages, he (she) might experience toxicity to many pharmaceuticals and caffeine. Similarly, if a patient is discharged from a smoke-free environment with a newly adjusted medication regimen and resumes smoking or caffeine consumption, alterations in enzyme activity might reduce therapeutic efficacy of prescribed medicines. These effects are a result of alterations in the hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme system.

Taking a careful history of tobacco and caffeine use, and knowing the effects that these substances will have on specific medications, will help guide treatment and management decisions.

The role of CYP enzymes

CYP hepatic enzymes detoxify a variety of environmental agents into water-soluble compounds that are excreted in urine. CYP1A2 metabolizes 20% of drugs handled by the CYP system and comprises 13% of all the CYP enzymes expressed in the liver. The wide interindividual variation in CYP1A2 enzyme activity is influenced by a combination of genetic, epigenetic, ethnic, and environmental variables.1

Influence of tobacco on CYP

The polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in tobacco smoke induce CYP1A2 and CYP2B6 hepatic enzymes.2 Smokers exhibit increased activity of these enzymes, which results in faster clearance of many drugs, lower concentrations in blood, and diminished clinical response. The Table lists psychotropic medicines that are metabolized by CYP1A2 and CYP2B6. Co-administration of these substrates could decrease the elimination rate of other drugs also metabolized by CYP1A2. Nicotine in tobacco or in nicotine replacement therapies does not play a role in inducing CYP enzymes.

Psychiatric patients smoke at a higher rate than the general population.2 One study found that approximately 70% of patients with schizophrenia and as many as 45% of those with bipolar disorder smoke enough cigarettes (7 to 20 a day) to induce CYP1A2 and CYP2B6 activity.2 Patients who smoke and are given clozapine, haloperidol, or olanzapine show a lower serum concentration than non-smokers; in fact, the clozapine level can be reduced as much as 2.4-fold.2-5 Subsequently, patients can experience diminished clinical response to these 3 psychotropics.3

The turnover time for CYP1A2 is rapid— approximately 3 days—and a new CYP1A2 steady state activity is reached after approximately 1 week,4 which is important to remember when managing inpatients in a smoke-free facility. During acute hospitalization, patients could experience drug toxicity if the outpatient dosage is maintained.5

When they resume smoking after being discharged on a stabilized dosage of any of the medications listed in the Table, previous enzyme activity rebounds and might reduce the drug level, potentially leading to inadequate clinical response.

Caffeine and other substances

Asking about the patient’s caffeine intake is necessary because consumption of coffee is prevalent among smokers, and caffeine is metabolized by CYP1A2. Smokers need to consume as much as 4 times the amount of caffeine as non-smokers to achieve a similar caffeine serum concentration.2 Caffeine can form an insoluble precipitate with antipsychotic medication in the gut, which decreases absorption. The interaction between smoking-related induction of CYP1A2 enzymes and forced smoking cessation during hospitalization, with ongoing caffeine consumption, could lead to caffeine toxicity.4,5

Other common inducers of CYP1A2 are insulin, cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, and charcoal-grilled meat. Also, cumin and turmeric inhibit CYP1A2 activity, which might explain an ethnic difference in drug tolerance across population groups. Additionally, certain genetic polymorphisms, in specific ethnic distributions, alter the potential for tobacco smoke to induce CYP1A2.6

Some of these polymorphisms can be genotyped for clinical application.3

Asking about a patient’s tobacco and caffeine use and understanding their interactions with specific medications provides guidance when prescribing antipsychotic medications and adjusting dosage for inpatients and during clinical follow-up care.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

When a patient who smokes enters a tobacco-free medical facility and has access to caffeinated beverages, he (she) might experience toxicity to many pharmaceuticals and caffeine. Similarly, if a patient is discharged from a smoke-free environment with a newly adjusted medication regimen and resumes smoking or caffeine consumption, alterations in enzyme activity might reduce therapeutic efficacy of prescribed medicines. These effects are a result of alterations in the hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme system.

Taking a careful history of tobacco and caffeine use, and knowing the effects that these substances will have on specific medications, will help guide treatment and management decisions.

The role of CYP enzymes

CYP hepatic enzymes detoxify a variety of environmental agents into water-soluble compounds that are excreted in urine. CYP1A2 metabolizes 20% of drugs handled by the CYP system and comprises 13% of all the CYP enzymes expressed in the liver. The wide interindividual variation in CYP1A2 enzyme activity is influenced by a combination of genetic, epigenetic, ethnic, and environmental variables.1

Influence of tobacco on CYP

The polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in tobacco smoke induce CYP1A2 and CYP2B6 hepatic enzymes.2 Smokers exhibit increased activity of these enzymes, which results in faster clearance of many drugs, lower concentrations in blood, and diminished clinical response. The Table lists psychotropic medicines that are metabolized by CYP1A2 and CYP2B6. Co-administration of these substrates could decrease the elimination rate of other drugs also metabolized by CYP1A2. Nicotine in tobacco or in nicotine replacement therapies does not play a role in inducing CYP enzymes.

Psychiatric patients smoke at a higher rate than the general population.2 One study found that approximately 70% of patients with schizophrenia and as many as 45% of those with bipolar disorder smoke enough cigarettes (7 to 20 a day) to induce CYP1A2 and CYP2B6 activity.2 Patients who smoke and are given clozapine, haloperidol, or olanzapine show a lower serum concentration than non-smokers; in fact, the clozapine level can be reduced as much as 2.4-fold.2-5 Subsequently, patients can experience diminished clinical response to these 3 psychotropics.3

The turnover time for CYP1A2 is rapid— approximately 3 days—and a new CYP1A2 steady state activity is reached after approximately 1 week,4 which is important to remember when managing inpatients in a smoke-free facility. During acute hospitalization, patients could experience drug toxicity if the outpatient dosage is maintained.5

When they resume smoking after being discharged on a stabilized dosage of any of the medications listed in the Table, previous enzyme activity rebounds and might reduce the drug level, potentially leading to inadequate clinical response.

Caffeine and other substances

Asking about the patient’s caffeine intake is necessary because consumption of coffee is prevalent among smokers, and caffeine is metabolized by CYP1A2. Smokers need to consume as much as 4 times the amount of caffeine as non-smokers to achieve a similar caffeine serum concentration.2 Caffeine can form an insoluble precipitate with antipsychotic medication in the gut, which decreases absorption. The interaction between smoking-related induction of CYP1A2 enzymes and forced smoking cessation during hospitalization, with ongoing caffeine consumption, could lead to caffeine toxicity.4,5

Other common inducers of CYP1A2 are insulin, cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, and charcoal-grilled meat. Also, cumin and turmeric inhibit CYP1A2 activity, which might explain an ethnic difference in drug tolerance across population groups. Additionally, certain genetic polymorphisms, in specific ethnic distributions, alter the potential for tobacco smoke to induce CYP1A2.6

Some of these polymorphisms can be genotyped for clinical application.3

Asking about a patient’s tobacco and caffeine use and understanding their interactions with specific medications provides guidance when prescribing antipsychotic medications and adjusting dosage for inpatients and during clinical follow-up care.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Wang B, Zhou SF. Synthetic and natural compounds that interact with human cytochrome P450 1A2 and implications in drug development. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(31):4066-4218.

2. Lucas C, Martin J. Smoking and drug interactions. Australian Prescriber. 2013;36(3):102-104.

3. Eap CB, Bender S, Jaquenoud Sirot E, et al. Nonresponse to clozapine and ultrarapid CYP1A2 activity: clinical data and analysis of CYP1A2 gene. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004; 24(2):214-209.

4. Faber MS, Fuhr U. Time response of cytochrome P450 1A2 activity on cessation of heavy smoking. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76(2):178-184.

5. Berk M, Ng F, Wang WV, et al. Going up in smoke: tobacco smoking is associated with worse treatment outcomes in mania. J Affect Disord. 2008;110(1-2):126-134.

6. Zhou SF, Yang LP, Zhou ZW, et al. Insights into the substrate specificity, inhibitors, regulation, and polymorphisms and the clinical impact of human cytochrome P450 1A2. AAPS. 2009;11(3):481-494.

1. Wang B, Zhou SF. Synthetic and natural compounds that interact with human cytochrome P450 1A2 and implications in drug development. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(31):4066-4218.

2. Lucas C, Martin J. Smoking and drug interactions. Australian Prescriber. 2013;36(3):102-104.

3. Eap CB, Bender S, Jaquenoud Sirot E, et al. Nonresponse to clozapine and ultrarapid CYP1A2 activity: clinical data and analysis of CYP1A2 gene. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004; 24(2):214-209.

4. Faber MS, Fuhr U. Time response of cytochrome P450 1A2 activity on cessation of heavy smoking. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76(2):178-184.

5. Berk M, Ng F, Wang WV, et al. Going up in smoke: tobacco smoking is associated with worse treatment outcomes in mania. J Affect Disord. 2008;110(1-2):126-134.

6. Zhou SF, Yang LP, Zhou ZW, et al. Insights into the substrate specificity, inhibitors, regulation, and polymorphisms and the clinical impact of human cytochrome P450 1A2. AAPS. 2009;11(3):481-494.

Abnormal calcium level in a psychiatric presentation? Rule out parathyroid disease

In some patients, symptoms of depression, psychosis, delirium, or dementia exist concomitantly with, or as a result of, an abnormal (elevated or low) serum calcium concentration that has been precipitated by an unrecognized endocrinopathy. The apparent psychiatric presentations of such patients might reflect parathyroid pathology—not psychopathology.

Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia often are related to a distinct spectrum of conditions, such as diseases of the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and various neoplasms including malignancies. Be alert to the possibility of parathyroid disease in patients whose presentation suggests mental illness concurrent with, or as a direct consequence of, an abnormal calcium level, and investigate appropriately.

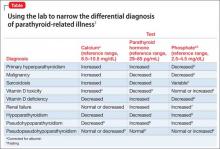

The Table1-9 illustrates how 3 clinical laboratory tests—serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), and phosphate—can narrow the differential diagnosis when the clinical impression is parathyroid-related illness. Seek endocrinology consultation whenever a parathyroid-associated ailment is discovered or suspected. Serum calcium is routinely assayed in hospitalized patients; when managing a patient with treatment-refractory psychiatric illness, (1) always check the reported result of that test and (2) consider measuring PTH.

Case reports1

Case 1: Woman with chronic depression. The patient was hospitalized while suicidal. Serial serum calcium levels were 12.5 mg/dL and 15.8 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The PTH level was elevated at 287 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL).

After thyroid imaging, surgery revealed a parathyroid mass, which was resected. Histologic examination confirmed an adenoma.

The calcium concentration declined to 8.6 mg/dL postoperatively and stabilized at 9.2 mg/dL. Psychiatric symptoms resolved fully; she experienced a complete recovery.

Case 2: Man on long-term lithium maintenance. The patient was admitted in a delusional psychotic state. The serum calcium level was 14.3 mg/dL initially, decreasing to 11.5 mg/dL after lithium was discontinued. The PTH level was elevated at 97 pg/mL at admission, consistent with hyperparathyroidism.

A parathyroid adenoma was resected. Serum calcium level normalized at 10.7 mg/dL; psychosis resolved with striking, sustained improvement in mental status.

Full return to mental, physical health

The diagnosis of parathyroid adenoma in these 2 patients, which began with a psychiatric presentation, was properly made after an abnormal serum calcium level was documented. Surgical treatment of the endocrinopathy produced full remission and a return to normal mental and physical health.

Although psychiatric manifestations are associated with an abnormal serum calcium concentration, the severity of those presentations does not correlate with the degree of abnormality of the calcium level.10

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Velasco PJ, Manshadi M, Breen K, et al. Psychiatric aspects of parathyroid disease. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(6):486-490.

2. Harrop JS, Bailey JE, Woodhead JS. Incidence of hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism in relation to the biochemical profile. J Clin Pathol. 1982; 35(4):395-400.

3. Assadi F. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based problem-solving approach to clinical cases. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4(3):195-201.

4. Ozkhan B, Hatun S, Bereket A. Vitamin D intoxication. Turk J Pediatr. 2012;54(2):93-98.

5. Studdy PR, Bird R, Neville E, et al. Biochemical findings in sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33(6):528-533.

6. Geller JL, Adam JS. Vitamin D therapy. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6(1):5-11.

7. Albaaj F, Hutchison A. Hyperphosphatemia in renal failure: causes, consequences and current management. Drugs. 2003;63(6):577-596.

8. Al-Azem H, Khan AA. Hypoparathyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):517-522.

9. Brown H, Englert E, Wallach S. The syndrome of pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1956;98(4):517-524.

10. Pfitzenmeyer P, Besancenot JF, Verges B, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in very old patients. Eur J Med. 1993;2(8):453-456.

In some patients, symptoms of depression, psychosis, delirium, or dementia exist concomitantly with, or as a result of, an abnormal (elevated or low) serum calcium concentration that has been precipitated by an unrecognized endocrinopathy. The apparent psychiatric presentations of such patients might reflect parathyroid pathology—not psychopathology.

Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia often are related to a distinct spectrum of conditions, such as diseases of the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and various neoplasms including malignancies. Be alert to the possibility of parathyroid disease in patients whose presentation suggests mental illness concurrent with, or as a direct consequence of, an abnormal calcium level, and investigate appropriately.

The Table1-9 illustrates how 3 clinical laboratory tests—serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), and phosphate—can narrow the differential diagnosis when the clinical impression is parathyroid-related illness. Seek endocrinology consultation whenever a parathyroid-associated ailment is discovered or suspected. Serum calcium is routinely assayed in hospitalized patients; when managing a patient with treatment-refractory psychiatric illness, (1) always check the reported result of that test and (2) consider measuring PTH.

Case reports1

Case 1: Woman with chronic depression. The patient was hospitalized while suicidal. Serial serum calcium levels were 12.5 mg/dL and 15.8 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The PTH level was elevated at 287 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL).

After thyroid imaging, surgery revealed a parathyroid mass, which was resected. Histologic examination confirmed an adenoma.

The calcium concentration declined to 8.6 mg/dL postoperatively and stabilized at 9.2 mg/dL. Psychiatric symptoms resolved fully; she experienced a complete recovery.

Case 2: Man on long-term lithium maintenance. The patient was admitted in a delusional psychotic state. The serum calcium level was 14.3 mg/dL initially, decreasing to 11.5 mg/dL after lithium was discontinued. The PTH level was elevated at 97 pg/mL at admission, consistent with hyperparathyroidism.

A parathyroid adenoma was resected. Serum calcium level normalized at 10.7 mg/dL; psychosis resolved with striking, sustained improvement in mental status.

Full return to mental, physical health

The diagnosis of parathyroid adenoma in these 2 patients, which began with a psychiatric presentation, was properly made after an abnormal serum calcium level was documented. Surgical treatment of the endocrinopathy produced full remission and a return to normal mental and physical health.

Although psychiatric manifestations are associated with an abnormal serum calcium concentration, the severity of those presentations does not correlate with the degree of abnormality of the calcium level.10

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

In some patients, symptoms of depression, psychosis, delirium, or dementia exist concomitantly with, or as a result of, an abnormal (elevated or low) serum calcium concentration that has been precipitated by an unrecognized endocrinopathy. The apparent psychiatric presentations of such patients might reflect parathyroid pathology—not psychopathology.

Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia often are related to a distinct spectrum of conditions, such as diseases of the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and various neoplasms including malignancies. Be alert to the possibility of parathyroid disease in patients whose presentation suggests mental illness concurrent with, or as a direct consequence of, an abnormal calcium level, and investigate appropriately.

The Table1-9 illustrates how 3 clinical laboratory tests—serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), and phosphate—can narrow the differential diagnosis when the clinical impression is parathyroid-related illness. Seek endocrinology consultation whenever a parathyroid-associated ailment is discovered or suspected. Serum calcium is routinely assayed in hospitalized patients; when managing a patient with treatment-refractory psychiatric illness, (1) always check the reported result of that test and (2) consider measuring PTH.

Case reports1

Case 1: Woman with chronic depression. The patient was hospitalized while suicidal. Serial serum calcium levels were 12.5 mg/dL and 15.8 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The PTH level was elevated at 287 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL).

After thyroid imaging, surgery revealed a parathyroid mass, which was resected. Histologic examination confirmed an adenoma.

The calcium concentration declined to 8.6 mg/dL postoperatively and stabilized at 9.2 mg/dL. Psychiatric symptoms resolved fully; she experienced a complete recovery.

Case 2: Man on long-term lithium maintenance. The patient was admitted in a delusional psychotic state. The serum calcium level was 14.3 mg/dL initially, decreasing to 11.5 mg/dL after lithium was discontinued. The PTH level was elevated at 97 pg/mL at admission, consistent with hyperparathyroidism.

A parathyroid adenoma was resected. Serum calcium level normalized at 10.7 mg/dL; psychosis resolved with striking, sustained improvement in mental status.

Full return to mental, physical health

The diagnosis of parathyroid adenoma in these 2 patients, which began with a psychiatric presentation, was properly made after an abnormal serum calcium level was documented. Surgical treatment of the endocrinopathy produced full remission and a return to normal mental and physical health.

Although psychiatric manifestations are associated with an abnormal serum calcium concentration, the severity of those presentations does not correlate with the degree of abnormality of the calcium level.10

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Velasco PJ, Manshadi M, Breen K, et al. Psychiatric aspects of parathyroid disease. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(6):486-490.

2. Harrop JS, Bailey JE, Woodhead JS. Incidence of hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism in relation to the biochemical profile. J Clin Pathol. 1982; 35(4):395-400.

3. Assadi F. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based problem-solving approach to clinical cases. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4(3):195-201.

4. Ozkhan B, Hatun S, Bereket A. Vitamin D intoxication. Turk J Pediatr. 2012;54(2):93-98.

5. Studdy PR, Bird R, Neville E, et al. Biochemical findings in sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33(6):528-533.

6. Geller JL, Adam JS. Vitamin D therapy. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6(1):5-11.

7. Albaaj F, Hutchison A. Hyperphosphatemia in renal failure: causes, consequences and current management. Drugs. 2003;63(6):577-596.

8. Al-Azem H, Khan AA. Hypoparathyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):517-522.

9. Brown H, Englert E, Wallach S. The syndrome of pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1956;98(4):517-524.

10. Pfitzenmeyer P, Besancenot JF, Verges B, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in very old patients. Eur J Med. 1993;2(8):453-456.

1. Velasco PJ, Manshadi M, Breen K, et al. Psychiatric aspects of parathyroid disease. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(6):486-490.

2. Harrop JS, Bailey JE, Woodhead JS. Incidence of hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism in relation to the biochemical profile. J Clin Pathol. 1982; 35(4):395-400.

3. Assadi F. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based problem-solving approach to clinical cases. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4(3):195-201.

4. Ozkhan B, Hatun S, Bereket A. Vitamin D intoxication. Turk J Pediatr. 2012;54(2):93-98.

5. Studdy PR, Bird R, Neville E, et al. Biochemical findings in sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33(6):528-533.

6. Geller JL, Adam JS. Vitamin D therapy. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6(1):5-11.

7. Albaaj F, Hutchison A. Hyperphosphatemia in renal failure: causes, consequences and current management. Drugs. 2003;63(6):577-596.

8. Al-Azem H, Khan AA. Hypoparathyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):517-522.

9. Brown H, Englert E, Wallach S. The syndrome of pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1956;98(4):517-524.

10. Pfitzenmeyer P, Besancenot JF, Verges B, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in very old patients. Eur J Med. 1993;2(8):453-456.