User login

Abnormal calcium level in a psychiatric presentation? Rule out parathyroid disease

In some patients, symptoms of depression, psychosis, delirium, or dementia exist concomitantly with, or as a result of, an abnormal (elevated or low) serum calcium concentration that has been precipitated by an unrecognized endocrinopathy. The apparent psychiatric presentations of such patients might reflect parathyroid pathology—not psychopathology.

Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia often are related to a distinct spectrum of conditions, such as diseases of the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and various neoplasms including malignancies. Be alert to the possibility of parathyroid disease in patients whose presentation suggests mental illness concurrent with, or as a direct consequence of, an abnormal calcium level, and investigate appropriately.

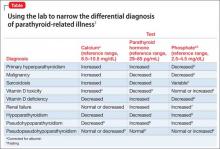

The Table1-9 illustrates how 3 clinical laboratory tests—serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), and phosphate—can narrow the differential diagnosis when the clinical impression is parathyroid-related illness. Seek endocrinology consultation whenever a parathyroid-associated ailment is discovered or suspected. Serum calcium is routinely assayed in hospitalized patients; when managing a patient with treatment-refractory psychiatric illness, (1) always check the reported result of that test and (2) consider measuring PTH.

Case reports1

Case 1: Woman with chronic depression. The patient was hospitalized while suicidal. Serial serum calcium levels were 12.5 mg/dL and 15.8 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The PTH level was elevated at 287 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL).

After thyroid imaging, surgery revealed a parathyroid mass, which was resected. Histologic examination confirmed an adenoma.

The calcium concentration declined to 8.6 mg/dL postoperatively and stabilized at 9.2 mg/dL. Psychiatric symptoms resolved fully; she experienced a complete recovery.

Case 2: Man on long-term lithium maintenance. The patient was admitted in a delusional psychotic state. The serum calcium level was 14.3 mg/dL initially, decreasing to 11.5 mg/dL after lithium was discontinued. The PTH level was elevated at 97 pg/mL at admission, consistent with hyperparathyroidism.

A parathyroid adenoma was resected. Serum calcium level normalized at 10.7 mg/dL; psychosis resolved with striking, sustained improvement in mental status.

Full return to mental, physical health

The diagnosis of parathyroid adenoma in these 2 patients, which began with a psychiatric presentation, was properly made after an abnormal serum calcium level was documented. Surgical treatment of the endocrinopathy produced full remission and a return to normal mental and physical health.

Although psychiatric manifestations are associated with an abnormal serum calcium concentration, the severity of those presentations does not correlate with the degree of abnormality of the calcium level.10

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Velasco PJ, Manshadi M, Breen K, et al. Psychiatric aspects of parathyroid disease. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(6):486-490.

2. Harrop JS, Bailey JE, Woodhead JS. Incidence of hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism in relation to the biochemical profile. J Clin Pathol. 1982; 35(4):395-400.

3. Assadi F. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based problem-solving approach to clinical cases. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4(3):195-201.

4. Ozkhan B, Hatun S, Bereket A. Vitamin D intoxication. Turk J Pediatr. 2012;54(2):93-98.

5. Studdy PR, Bird R, Neville E, et al. Biochemical findings in sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33(6):528-533.

6. Geller JL, Adam JS. Vitamin D therapy. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6(1):5-11.

7. Albaaj F, Hutchison A. Hyperphosphatemia in renal failure: causes, consequences and current management. Drugs. 2003;63(6):577-596.

8. Al-Azem H, Khan AA. Hypoparathyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):517-522.

9. Brown H, Englert E, Wallach S. The syndrome of pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1956;98(4):517-524.

10. Pfitzenmeyer P, Besancenot JF, Verges B, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in very old patients. Eur J Med. 1993;2(8):453-456.

In some patients, symptoms of depression, psychosis, delirium, or dementia exist concomitantly with, or as a result of, an abnormal (elevated or low) serum calcium concentration that has been precipitated by an unrecognized endocrinopathy. The apparent psychiatric presentations of such patients might reflect parathyroid pathology—not psychopathology.

Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia often are related to a distinct spectrum of conditions, such as diseases of the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and various neoplasms including malignancies. Be alert to the possibility of parathyroid disease in patients whose presentation suggests mental illness concurrent with, or as a direct consequence of, an abnormal calcium level, and investigate appropriately.

The Table1-9 illustrates how 3 clinical laboratory tests—serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), and phosphate—can narrow the differential diagnosis when the clinical impression is parathyroid-related illness. Seek endocrinology consultation whenever a parathyroid-associated ailment is discovered or suspected. Serum calcium is routinely assayed in hospitalized patients; when managing a patient with treatment-refractory psychiatric illness, (1) always check the reported result of that test and (2) consider measuring PTH.

Case reports1

Case 1: Woman with chronic depression. The patient was hospitalized while suicidal. Serial serum calcium levels were 12.5 mg/dL and 15.8 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The PTH level was elevated at 287 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL).

After thyroid imaging, surgery revealed a parathyroid mass, which was resected. Histologic examination confirmed an adenoma.

The calcium concentration declined to 8.6 mg/dL postoperatively and stabilized at 9.2 mg/dL. Psychiatric symptoms resolved fully; she experienced a complete recovery.

Case 2: Man on long-term lithium maintenance. The patient was admitted in a delusional psychotic state. The serum calcium level was 14.3 mg/dL initially, decreasing to 11.5 mg/dL after lithium was discontinued. The PTH level was elevated at 97 pg/mL at admission, consistent with hyperparathyroidism.

A parathyroid adenoma was resected. Serum calcium level normalized at 10.7 mg/dL; psychosis resolved with striking, sustained improvement in mental status.

Full return to mental, physical health

The diagnosis of parathyroid adenoma in these 2 patients, which began with a psychiatric presentation, was properly made after an abnormal serum calcium level was documented. Surgical treatment of the endocrinopathy produced full remission and a return to normal mental and physical health.

Although psychiatric manifestations are associated with an abnormal serum calcium concentration, the severity of those presentations does not correlate with the degree of abnormality of the calcium level.10

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

In some patients, symptoms of depression, psychosis, delirium, or dementia exist concomitantly with, or as a result of, an abnormal (elevated or low) serum calcium concentration that has been precipitated by an unrecognized endocrinopathy. The apparent psychiatric presentations of such patients might reflect parathyroid pathology—not psychopathology.

Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia often are related to a distinct spectrum of conditions, such as diseases of the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and various neoplasms including malignancies. Be alert to the possibility of parathyroid disease in patients whose presentation suggests mental illness concurrent with, or as a direct consequence of, an abnormal calcium level, and investigate appropriately.

The Table1-9 illustrates how 3 clinical laboratory tests—serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), and phosphate—can narrow the differential diagnosis when the clinical impression is parathyroid-related illness. Seek endocrinology consultation whenever a parathyroid-associated ailment is discovered or suspected. Serum calcium is routinely assayed in hospitalized patients; when managing a patient with treatment-refractory psychiatric illness, (1) always check the reported result of that test and (2) consider measuring PTH.

Case reports1

Case 1: Woman with chronic depression. The patient was hospitalized while suicidal. Serial serum calcium levels were 12.5 mg/dL and 15.8 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The PTH level was elevated at 287 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL).

After thyroid imaging, surgery revealed a parathyroid mass, which was resected. Histologic examination confirmed an adenoma.

The calcium concentration declined to 8.6 mg/dL postoperatively and stabilized at 9.2 mg/dL. Psychiatric symptoms resolved fully; she experienced a complete recovery.

Case 2: Man on long-term lithium maintenance. The patient was admitted in a delusional psychotic state. The serum calcium level was 14.3 mg/dL initially, decreasing to 11.5 mg/dL after lithium was discontinued. The PTH level was elevated at 97 pg/mL at admission, consistent with hyperparathyroidism.

A parathyroid adenoma was resected. Serum calcium level normalized at 10.7 mg/dL; psychosis resolved with striking, sustained improvement in mental status.

Full return to mental, physical health

The diagnosis of parathyroid adenoma in these 2 patients, which began with a psychiatric presentation, was properly made after an abnormal serum calcium level was documented. Surgical treatment of the endocrinopathy produced full remission and a return to normal mental and physical health.

Although psychiatric manifestations are associated with an abnormal serum calcium concentration, the severity of those presentations does not correlate with the degree of abnormality of the calcium level.10

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Velasco PJ, Manshadi M, Breen K, et al. Psychiatric aspects of parathyroid disease. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(6):486-490.

2. Harrop JS, Bailey JE, Woodhead JS. Incidence of hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism in relation to the biochemical profile. J Clin Pathol. 1982; 35(4):395-400.

3. Assadi F. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based problem-solving approach to clinical cases. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4(3):195-201.

4. Ozkhan B, Hatun S, Bereket A. Vitamin D intoxication. Turk J Pediatr. 2012;54(2):93-98.

5. Studdy PR, Bird R, Neville E, et al. Biochemical findings in sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33(6):528-533.

6. Geller JL, Adam JS. Vitamin D therapy. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6(1):5-11.

7. Albaaj F, Hutchison A. Hyperphosphatemia in renal failure: causes, consequences and current management. Drugs. 2003;63(6):577-596.

8. Al-Azem H, Khan AA. Hypoparathyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):517-522.

9. Brown H, Englert E, Wallach S. The syndrome of pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1956;98(4):517-524.

10. Pfitzenmeyer P, Besancenot JF, Verges B, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in very old patients. Eur J Med. 1993;2(8):453-456.

1. Velasco PJ, Manshadi M, Breen K, et al. Psychiatric aspects of parathyroid disease. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(6):486-490.

2. Harrop JS, Bailey JE, Woodhead JS. Incidence of hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism in relation to the biochemical profile. J Clin Pathol. 1982; 35(4):395-400.

3. Assadi F. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based problem-solving approach to clinical cases. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4(3):195-201.

4. Ozkhan B, Hatun S, Bereket A. Vitamin D intoxication. Turk J Pediatr. 2012;54(2):93-98.

5. Studdy PR, Bird R, Neville E, et al. Biochemical findings in sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33(6):528-533.

6. Geller JL, Adam JS. Vitamin D therapy. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6(1):5-11.

7. Albaaj F, Hutchison A. Hyperphosphatemia in renal failure: causes, consequences and current management. Drugs. 2003;63(6):577-596.

8. Al-Azem H, Khan AA. Hypoparathyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):517-522.

9. Brown H, Englert E, Wallach S. The syndrome of pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1956;98(4):517-524.

10. Pfitzenmeyer P, Besancenot JF, Verges B, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in very old patients. Eur J Med. 1993;2(8):453-456.

Consider a mandibular positioning device to alleviate sleep-disordered breathing

Snoring, snorting, gasping, and obstructive sleep apnea are caused by collapse of the pharyngeal airway during sleep.1 Pathophysiology includes a combination of anatomical and physiological variables.1 Common anatomical predisposing conditions include abnormalities of pharyngeal, lingual, and dental arches; physiological concerns are advancing age, male sex, obesity, use of sedatives, body positioning, and reduced muscle tone during rapid eye movement sleep. Coexistence of anatomic and physiological elements can produce significant narrowing of the upper airway.

Comorbidities include vascular, metabolic, and psychiatric conditions. As many as one-third of people with symptoms of sleep apnea report depressed mood; approximately 10% of these patients meet criteria for moderate or severe depression.2

In short, sleep-disordered breathing has a globally negative effect on mental health.

When should you consider obtaining a sleep apnea study?

Refer patients for a sleep study when snoring, snorting, gasping, or pauses in breathing occur during sleep, or in the case of daytime sleepiness, fatigue, or unrefreshing sleep that cannot be explained by another medical or psychiatric illness.2 A sleep specialist can determine the most appropriate intervention for sleep-disordered breathing.

An apneic event is characterized by complete cessation of airflow; hypopnea is a partially compromised airway. In either event, at least a 3% decrease in oxygen saturation occurs for at least 10 seconds.3 A diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea or hypopnea is required when polysomnography reveals either of:

• ≥5 episodes of apnea or hypopnea, or both, per hour of sleep, with symptoms of a rhythmic breathing disturbance or daytime sleepiness or fatigue

• ≥15 episodes of apnea or hypopnea, or both, per hour of sleep, regardless of accompanying symptoms.2

What are the treatment options?

• Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines.

• Surgical procedures include adeno-tonsillectomy in children and surgical maxilla-mandibular advancement or palatal implants for adults.

• A novel implantable electrical stimulation device stimulates the hypoglossal nerve, which activates the genioglossus muscle, thus moving the tongue forward to open the airway.

• An anterior mandibular positioning (AMP) device increases the diameter of the retroglossal space by preventing posterior movement of the mandible and tongue, thereby limiting encroachment on the airway diameter and reducing the potential for collapse.1-4

When should you recommend an AMP device?

Consider recommending an AMP device to treat sleep-disordered breathing when (1) lifestyle changes, such as sleep hygiene, weight loss, and stopping sedatives, do not work and (2) a CPAP machine or a surgical procedure is contraindicated or has been ineffective.1 An AMP device can minimize snoring and relieve airway obstruction, especially in patients with supine position-related apnea.4 To keep the airway open in non-supine position-related cases, an AMP device might be indicated in addition to CPAP delivered nasally.1

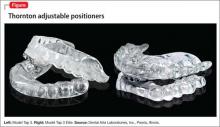

This plastic oral appliance is either a 1- or 2-piece design, and looks and is sized similarly to an athletic mouth-protection guard or an oral anti-bruxism tooth-protection appliance. It is affixed to the mandible and maxillary arches by clasps (Figure).

An AMP device often is most beneficial for supine-dependent sleep apnea patients and those with loud snoring, without sleep apnea.4 Response is best in young adults and in patients who have a low body mass index, are free of sedatives, and have appropriate cephalometrics of the oral, dental, or pharyngeal anatomy. Improved sleep architecture, continuous sleep with less snoring, and increased daytime alertness are observed in patients who respond to an AMP device.

An AMP device is contraindicated when the device cannot be affixed to the dental arches and in some patients with an anatomical or pain-related temporomandibular joint disorder.5 The device is easy to use, noninvasive, readily accessible, and less expensive than alternatives.3

How can you help maintain treatment adherence?

AMP devices can induce adverse effects, including dental pain or discomfort through orthodontic alterations; patient reports and follow-up can yield detection and device adjustments can alleviate such problems. Adherence generally is good, with complaints usually limited to minor tooth discomfort, occlusive changes, and increased or decreased salivation.5 In our clinical experience, many patients find these devices comfortable and easy to use, but might complain of feeling awkward when wearing them.

Changes in occlusion can occur during long-term treatment with an AMP device. Proper fitting is essential to facilitate a more open airway and the ability to speak and drink fluids, and to maintain safety, even if vomiting occurs while the device is in place.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):263-276.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. de Britto Teixeira AO, Abi-Ramia LB, de Oliveira Almeida MA. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with oral appliances. Prog Orthod. 2013;14:10.

4. Marklund M, Stenlund H, Franklin K. Mandibular advancement devices in 630 men and women with obstructive sleep apnea and snoring: tolerability and predictors of treatment success. Chest. 2004;125(4):1270-1278.

5. Ferguson KA, Cartwright R, Rogers R, et al. Oral appliances for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: a review. Sleep. 2006;29(2):244-262.

Snoring, snorting, gasping, and obstructive sleep apnea are caused by collapse of the pharyngeal airway during sleep.1 Pathophysiology includes a combination of anatomical and physiological variables.1 Common anatomical predisposing conditions include abnormalities of pharyngeal, lingual, and dental arches; physiological concerns are advancing age, male sex, obesity, use of sedatives, body positioning, and reduced muscle tone during rapid eye movement sleep. Coexistence of anatomic and physiological elements can produce significant narrowing of the upper airway.

Comorbidities include vascular, metabolic, and psychiatric conditions. As many as one-third of people with symptoms of sleep apnea report depressed mood; approximately 10% of these patients meet criteria for moderate or severe depression.2

In short, sleep-disordered breathing has a globally negative effect on mental health.

When should you consider obtaining a sleep apnea study?

Refer patients for a sleep study when snoring, snorting, gasping, or pauses in breathing occur during sleep, or in the case of daytime sleepiness, fatigue, or unrefreshing sleep that cannot be explained by another medical or psychiatric illness.2 A sleep specialist can determine the most appropriate intervention for sleep-disordered breathing.

An apneic event is characterized by complete cessation of airflow; hypopnea is a partially compromised airway. In either event, at least a 3% decrease in oxygen saturation occurs for at least 10 seconds.3 A diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea or hypopnea is required when polysomnography reveals either of:

• ≥5 episodes of apnea or hypopnea, or both, per hour of sleep, with symptoms of a rhythmic breathing disturbance or daytime sleepiness or fatigue

• ≥15 episodes of apnea or hypopnea, or both, per hour of sleep, regardless of accompanying symptoms.2

What are the treatment options?

• Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines.

• Surgical procedures include adeno-tonsillectomy in children and surgical maxilla-mandibular advancement or palatal implants for adults.

• A novel implantable electrical stimulation device stimulates the hypoglossal nerve, which activates the genioglossus muscle, thus moving the tongue forward to open the airway.

• An anterior mandibular positioning (AMP) device increases the diameter of the retroglossal space by preventing posterior movement of the mandible and tongue, thereby limiting encroachment on the airway diameter and reducing the potential for collapse.1-4

When should you recommend an AMP device?

Consider recommending an AMP device to treat sleep-disordered breathing when (1) lifestyle changes, such as sleep hygiene, weight loss, and stopping sedatives, do not work and (2) a CPAP machine or a surgical procedure is contraindicated or has been ineffective.1 An AMP device can minimize snoring and relieve airway obstruction, especially in patients with supine position-related apnea.4 To keep the airway open in non-supine position-related cases, an AMP device might be indicated in addition to CPAP delivered nasally.1

This plastic oral appliance is either a 1- or 2-piece design, and looks and is sized similarly to an athletic mouth-protection guard or an oral anti-bruxism tooth-protection appliance. It is affixed to the mandible and maxillary arches by clasps (Figure).

An AMP device often is most beneficial for supine-dependent sleep apnea patients and those with loud snoring, without sleep apnea.4 Response is best in young adults and in patients who have a low body mass index, are free of sedatives, and have appropriate cephalometrics of the oral, dental, or pharyngeal anatomy. Improved sleep architecture, continuous sleep with less snoring, and increased daytime alertness are observed in patients who respond to an AMP device.

An AMP device is contraindicated when the device cannot be affixed to the dental arches and in some patients with an anatomical or pain-related temporomandibular joint disorder.5 The device is easy to use, noninvasive, readily accessible, and less expensive than alternatives.3

How can you help maintain treatment adherence?

AMP devices can induce adverse effects, including dental pain or discomfort through orthodontic alterations; patient reports and follow-up can yield detection and device adjustments can alleviate such problems. Adherence generally is good, with complaints usually limited to minor tooth discomfort, occlusive changes, and increased or decreased salivation.5 In our clinical experience, many patients find these devices comfortable and easy to use, but might complain of feeling awkward when wearing them.

Changes in occlusion can occur during long-term treatment with an AMP device. Proper fitting is essential to facilitate a more open airway and the ability to speak and drink fluids, and to maintain safety, even if vomiting occurs while the device is in place.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Snoring, snorting, gasping, and obstructive sleep apnea are caused by collapse of the pharyngeal airway during sleep.1 Pathophysiology includes a combination of anatomical and physiological variables.1 Common anatomical predisposing conditions include abnormalities of pharyngeal, lingual, and dental arches; physiological concerns are advancing age, male sex, obesity, use of sedatives, body positioning, and reduced muscle tone during rapid eye movement sleep. Coexistence of anatomic and physiological elements can produce significant narrowing of the upper airway.

Comorbidities include vascular, metabolic, and psychiatric conditions. As many as one-third of people with symptoms of sleep apnea report depressed mood; approximately 10% of these patients meet criteria for moderate or severe depression.2

In short, sleep-disordered breathing has a globally negative effect on mental health.

When should you consider obtaining a sleep apnea study?

Refer patients for a sleep study when snoring, snorting, gasping, or pauses in breathing occur during sleep, or in the case of daytime sleepiness, fatigue, or unrefreshing sleep that cannot be explained by another medical or psychiatric illness.2 A sleep specialist can determine the most appropriate intervention for sleep-disordered breathing.

An apneic event is characterized by complete cessation of airflow; hypopnea is a partially compromised airway. In either event, at least a 3% decrease in oxygen saturation occurs for at least 10 seconds.3 A diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea or hypopnea is required when polysomnography reveals either of:

• ≥5 episodes of apnea or hypopnea, or both, per hour of sleep, with symptoms of a rhythmic breathing disturbance or daytime sleepiness or fatigue

• ≥15 episodes of apnea or hypopnea, or both, per hour of sleep, regardless of accompanying symptoms.2

What are the treatment options?

• Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines.

• Surgical procedures include adeno-tonsillectomy in children and surgical maxilla-mandibular advancement or palatal implants for adults.

• A novel implantable electrical stimulation device stimulates the hypoglossal nerve, which activates the genioglossus muscle, thus moving the tongue forward to open the airway.

• An anterior mandibular positioning (AMP) device increases the diameter of the retroglossal space by preventing posterior movement of the mandible and tongue, thereby limiting encroachment on the airway diameter and reducing the potential for collapse.1-4

When should you recommend an AMP device?

Consider recommending an AMP device to treat sleep-disordered breathing when (1) lifestyle changes, such as sleep hygiene, weight loss, and stopping sedatives, do not work and (2) a CPAP machine or a surgical procedure is contraindicated or has been ineffective.1 An AMP device can minimize snoring and relieve airway obstruction, especially in patients with supine position-related apnea.4 To keep the airway open in non-supine position-related cases, an AMP device might be indicated in addition to CPAP delivered nasally.1

This plastic oral appliance is either a 1- or 2-piece design, and looks and is sized similarly to an athletic mouth-protection guard or an oral anti-bruxism tooth-protection appliance. It is affixed to the mandible and maxillary arches by clasps (Figure).

An AMP device often is most beneficial for supine-dependent sleep apnea patients and those with loud snoring, without sleep apnea.4 Response is best in young adults and in patients who have a low body mass index, are free of sedatives, and have appropriate cephalometrics of the oral, dental, or pharyngeal anatomy. Improved sleep architecture, continuous sleep with less snoring, and increased daytime alertness are observed in patients who respond to an AMP device.

An AMP device is contraindicated when the device cannot be affixed to the dental arches and in some patients with an anatomical or pain-related temporomandibular joint disorder.5 The device is easy to use, noninvasive, readily accessible, and less expensive than alternatives.3

How can you help maintain treatment adherence?

AMP devices can induce adverse effects, including dental pain or discomfort through orthodontic alterations; patient reports and follow-up can yield detection and device adjustments can alleviate such problems. Adherence generally is good, with complaints usually limited to minor tooth discomfort, occlusive changes, and increased or decreased salivation.5 In our clinical experience, many patients find these devices comfortable and easy to use, but might complain of feeling awkward when wearing them.

Changes in occlusion can occur during long-term treatment with an AMP device. Proper fitting is essential to facilitate a more open airway and the ability to speak and drink fluids, and to maintain safety, even if vomiting occurs while the device is in place.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):263-276.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. de Britto Teixeira AO, Abi-Ramia LB, de Oliveira Almeida MA. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with oral appliances. Prog Orthod. 2013;14:10.

4. Marklund M, Stenlund H, Franklin K. Mandibular advancement devices in 630 men and women with obstructive sleep apnea and snoring: tolerability and predictors of treatment success. Chest. 2004;125(4):1270-1278.

5. Ferguson KA, Cartwright R, Rogers R, et al. Oral appliances for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: a review. Sleep. 2006;29(2):244-262.

1. Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):263-276.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. de Britto Teixeira AO, Abi-Ramia LB, de Oliveira Almeida MA. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with oral appliances. Prog Orthod. 2013;14:10.

4. Marklund M, Stenlund H, Franklin K. Mandibular advancement devices in 630 men and women with obstructive sleep apnea and snoring: tolerability and predictors of treatment success. Chest. 2004;125(4):1270-1278.

5. Ferguson KA, Cartwright R, Rogers R, et al. Oral appliances for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: a review. Sleep. 2006;29(2):244-262.

Frontotemporal dementia and its variants: What to look for

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a neurologic disease that affects the frontal and the temporal lobes of the cerebral cortex.1 This disorder is observed most often in people between age 45 to 65, but also can manifest in younger or older persons.1 The cause varies among a range of pathologies affecting the anterior portions of the brain.2

Presentations

FTD presents with changes in personality, social skills, ability to concentrate, motivation, reasoning, and language abnormality.3 Memory loss is less prominent in this condition compared with other dementias; therefore, identification may be a diagnostic challenge. FTD can be misdiagnosed as a psychiatric illness or not recognized because social symptoms dominate over cognitive dysfunction. As the disease progresses, patients may become increasingly unable to plan or organize activities of daily living, behave appropriately, and react normally in social interactions.1

FTD has 3 diagnostic variants1-4:

Behavioral variant. Known as Pick disease or the “frontal variant,”1,2 this type of FTD manifests as changes in personality, improper behavior in social settings, personal neglect, or impulsivity, such as shoplifting or hypersexuality.

Primary progressive aphasia. Two types of language dysfunction are observed in FTD:

• Semantic dementia (SD)3: Left-sided SD presents with “meaningless speech” or “word substitutions” (eg, “chair” instead of “table”). Right-sided SD, however, is characterized by forgetting the faces of familiar people or objects.

• Primary nonfluent aphasia3: Language fluency is compromised. Persons with such language dysfunction cannot produce words easily, and their speech is stumbling and nonfluent.

FTD with motor neuron disease.4 The most common type of motor neuron disease associated with FTD is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Afflicted patients exhibit muscle weakness, spasms, and rigidity. This leads to difficulty in swallowing or breathing because the diaphragm and pharynx are paralyzed. Other diseases associated with FTD include corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy.

Diagnosis

In DSM-5, FTD has been renamed “frontotemporal lobar degeneration” under the category of “Major and Mild Neurocognitive Disorders.”5 The workup begins with a history, physical examination, and mental status assessment. Physical signs can include frontal-release, primitive reflexes. Early in the disease course, a palmomental reflex often is observed; later, as disease progress, the rooting reflex or palmar grasp may become apparent.1,5

Diagnosing FTD requires recognizing its symptoms and ruling out conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and schizophrenia.6 Laboratory studies may help identify other conditions. Brain imaging, such as MRI, can depict frontotemporal pathology and rule in or exclude other diseases.3,5

Psychometric testing can evaluate memory or cognitive ability, which might be unremarkable during the initial phases of FTD.4 Further psychological assessments may provide objective verification of frontal lobe deficiencies in social skills or activities of daily living.3 Positron emission tomography and single-photon emission computed tomography may demonstrate areas of decreased activity or hypoperfusion in frontal and temporal lobes.7

Interventions

Treatment of FTD is limited to symptomatic therapy8; there are no specific, approved countermeasures available. Comorbid conditions, such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension, should be treated medically. Social interventions such as day care, increased supervision, and emotional support from the family can be effective adjuvants.2

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Snowden JS, Neary D, Mann DM. Frontotemporal dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:140-143.

2. Frontotemporal degeneration. The Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration. http://www.theaftd.org/ frontotemporal-degeneration/ftd-overview. Accessed April 24, 2014.

3. Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1546-1554.

4. Clark CM, Forman MS. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration with motor neuron disease: a clinical and pathological spectrum. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(4):489-490.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:614-618.

6. Frontotemporal dementia diagnosis. UCSF Medical Center. http://www.ucsfhealth.org/conditions/frontotemporal_ dementia/diagnosis.html. Accessed April 24, 2014.

7. McMurtray AM, Chen AK, Shapira JS, et al. Variations in regional SPECT hypoperfusion and clinical features in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2006;66(4):517-522.

8. Miller BL, Lee SE. Frontotemporal dementia: treatment. Up To Date. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/frontotemporal-dementia-treatment?source=search_result&search=frontote mporal+dementia+treatment&selectedTitle=1~150. Updated December 30, 2013. Accessed April 24, 2014.

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a neurologic disease that affects the frontal and the temporal lobes of the cerebral cortex.1 This disorder is observed most often in people between age 45 to 65, but also can manifest in younger or older persons.1 The cause varies among a range of pathologies affecting the anterior portions of the brain.2

Presentations

FTD presents with changes in personality, social skills, ability to concentrate, motivation, reasoning, and language abnormality.3 Memory loss is less prominent in this condition compared with other dementias; therefore, identification may be a diagnostic challenge. FTD can be misdiagnosed as a psychiatric illness or not recognized because social symptoms dominate over cognitive dysfunction. As the disease progresses, patients may become increasingly unable to plan or organize activities of daily living, behave appropriately, and react normally in social interactions.1

FTD has 3 diagnostic variants1-4:

Behavioral variant. Known as Pick disease or the “frontal variant,”1,2 this type of FTD manifests as changes in personality, improper behavior in social settings, personal neglect, or impulsivity, such as shoplifting or hypersexuality.

Primary progressive aphasia. Two types of language dysfunction are observed in FTD:

• Semantic dementia (SD)3: Left-sided SD presents with “meaningless speech” or “word substitutions” (eg, “chair” instead of “table”). Right-sided SD, however, is characterized by forgetting the faces of familiar people or objects.

• Primary nonfluent aphasia3: Language fluency is compromised. Persons with such language dysfunction cannot produce words easily, and their speech is stumbling and nonfluent.

FTD with motor neuron disease.4 The most common type of motor neuron disease associated with FTD is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Afflicted patients exhibit muscle weakness, spasms, and rigidity. This leads to difficulty in swallowing or breathing because the diaphragm and pharynx are paralyzed. Other diseases associated with FTD include corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy.

Diagnosis

In DSM-5, FTD has been renamed “frontotemporal lobar degeneration” under the category of “Major and Mild Neurocognitive Disorders.”5 The workup begins with a history, physical examination, and mental status assessment. Physical signs can include frontal-release, primitive reflexes. Early in the disease course, a palmomental reflex often is observed; later, as disease progress, the rooting reflex or palmar grasp may become apparent.1,5

Diagnosing FTD requires recognizing its symptoms and ruling out conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and schizophrenia.6 Laboratory studies may help identify other conditions. Brain imaging, such as MRI, can depict frontotemporal pathology and rule in or exclude other diseases.3,5

Psychometric testing can evaluate memory or cognitive ability, which might be unremarkable during the initial phases of FTD.4 Further psychological assessments may provide objective verification of frontal lobe deficiencies in social skills or activities of daily living.3 Positron emission tomography and single-photon emission computed tomography may demonstrate areas of decreased activity or hypoperfusion in frontal and temporal lobes.7

Interventions

Treatment of FTD is limited to symptomatic therapy8; there are no specific, approved countermeasures available. Comorbid conditions, such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension, should be treated medically. Social interventions such as day care, increased supervision, and emotional support from the family can be effective adjuvants.2

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a neurologic disease that affects the frontal and the temporal lobes of the cerebral cortex.1 This disorder is observed most often in people between age 45 to 65, but also can manifest in younger or older persons.1 The cause varies among a range of pathologies affecting the anterior portions of the brain.2

Presentations

FTD presents with changes in personality, social skills, ability to concentrate, motivation, reasoning, and language abnormality.3 Memory loss is less prominent in this condition compared with other dementias; therefore, identification may be a diagnostic challenge. FTD can be misdiagnosed as a psychiatric illness or not recognized because social symptoms dominate over cognitive dysfunction. As the disease progresses, patients may become increasingly unable to plan or organize activities of daily living, behave appropriately, and react normally in social interactions.1

FTD has 3 diagnostic variants1-4:

Behavioral variant. Known as Pick disease or the “frontal variant,”1,2 this type of FTD manifests as changes in personality, improper behavior in social settings, personal neglect, or impulsivity, such as shoplifting or hypersexuality.

Primary progressive aphasia. Two types of language dysfunction are observed in FTD:

• Semantic dementia (SD)3: Left-sided SD presents with “meaningless speech” or “word substitutions” (eg, “chair” instead of “table”). Right-sided SD, however, is characterized by forgetting the faces of familiar people or objects.

• Primary nonfluent aphasia3: Language fluency is compromised. Persons with such language dysfunction cannot produce words easily, and their speech is stumbling and nonfluent.

FTD with motor neuron disease.4 The most common type of motor neuron disease associated with FTD is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Afflicted patients exhibit muscle weakness, spasms, and rigidity. This leads to difficulty in swallowing or breathing because the diaphragm and pharynx are paralyzed. Other diseases associated with FTD include corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy.

Diagnosis

In DSM-5, FTD has been renamed “frontotemporal lobar degeneration” under the category of “Major and Mild Neurocognitive Disorders.”5 The workup begins with a history, physical examination, and mental status assessment. Physical signs can include frontal-release, primitive reflexes. Early in the disease course, a palmomental reflex often is observed; later, as disease progress, the rooting reflex or palmar grasp may become apparent.1,5

Diagnosing FTD requires recognizing its symptoms and ruling out conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and schizophrenia.6 Laboratory studies may help identify other conditions. Brain imaging, such as MRI, can depict frontotemporal pathology and rule in or exclude other diseases.3,5

Psychometric testing can evaluate memory or cognitive ability, which might be unremarkable during the initial phases of FTD.4 Further psychological assessments may provide objective verification of frontal lobe deficiencies in social skills or activities of daily living.3 Positron emission tomography and single-photon emission computed tomography may demonstrate areas of decreased activity or hypoperfusion in frontal and temporal lobes.7

Interventions

Treatment of FTD is limited to symptomatic therapy8; there are no specific, approved countermeasures available. Comorbid conditions, such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension, should be treated medically. Social interventions such as day care, increased supervision, and emotional support from the family can be effective adjuvants.2

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Snowden JS, Neary D, Mann DM. Frontotemporal dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:140-143.

2. Frontotemporal degeneration. The Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration. http://www.theaftd.org/ frontotemporal-degeneration/ftd-overview. Accessed April 24, 2014.

3. Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1546-1554.

4. Clark CM, Forman MS. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration with motor neuron disease: a clinical and pathological spectrum. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(4):489-490.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:614-618.

6. Frontotemporal dementia diagnosis. UCSF Medical Center. http://www.ucsfhealth.org/conditions/frontotemporal_ dementia/diagnosis.html. Accessed April 24, 2014.

7. McMurtray AM, Chen AK, Shapira JS, et al. Variations in regional SPECT hypoperfusion and clinical features in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2006;66(4):517-522.

8. Miller BL, Lee SE. Frontotemporal dementia: treatment. Up To Date. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/frontotemporal-dementia-treatment?source=search_result&search=frontote mporal+dementia+treatment&selectedTitle=1~150. Updated December 30, 2013. Accessed April 24, 2014.

1. Snowden JS, Neary D, Mann DM. Frontotemporal dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:140-143.

2. Frontotemporal degeneration. The Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration. http://www.theaftd.org/ frontotemporal-degeneration/ftd-overview. Accessed April 24, 2014.

3. Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1546-1554.

4. Clark CM, Forman MS. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration with motor neuron disease: a clinical and pathological spectrum. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(4):489-490.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:614-618.

6. Frontotemporal dementia diagnosis. UCSF Medical Center. http://www.ucsfhealth.org/conditions/frontotemporal_ dementia/diagnosis.html. Accessed April 24, 2014.

7. McMurtray AM, Chen AK, Shapira JS, et al. Variations in regional SPECT hypoperfusion and clinical features in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2006;66(4):517-522.

8. Miller BL, Lee SE. Frontotemporal dementia: treatment. Up To Date. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/frontotemporal-dementia-treatment?source=search_result&search=frontote mporal+dementia+treatment&selectedTitle=1~150. Updated December 30, 2013. Accessed April 24, 2014.