User login

Gastric outlet obstruction: A red flag, potentially manageable

A 72-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with progressive nausea and vomiting. One week earlier, she developed early satiety and nausea with vomiting after eating solid food. Three days later her symptoms progressed, and she became unable to take anything by mouth. The patient also experienced a 40-lb weight loss in the previous 3 months. She denies symptoms of abdominal pain, hematemesis, or melena. Her medical history includes cholecystectomy and type 2 diabetes mellitus, diagnosed 1 year ago. She has no family history of gastrointestinal malignancy. She says she smoked 1 pack a day in her 20s. She does not consume alcohol.

On physical examination, she is normotensive with a heart rate of 105 beats per minute. The oral mucosa is dry, and the abdomen is mildly distended and tender to palpation in the epigastrium. Laboratory evaluation reveals hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis.

Computed tomography (CT) reveals a mass 3 cm by 4 cm in the pancreatic head. The mass has invaded the medial wall of the duodenum, with obstruction of the pancreatic and common bile ducts and extension into and occlusion of the superior mesenteric vein, with soft-tissue expansion around the superior mesenteric artery. CT also reveals retained stomach contents and an air-fluid level consistent with gastric outlet obstruction.

INTRINSIC OR EXTRINSIC BLOCKAGE

Gastric outlet obstruction, also called pyloric obstruction, is caused by intrinsic or extrinsic mechanical blockage of gastric emptying, generally in the distal stomach, pyloric channel, or duodenum, with associated symptoms of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and early satiety. It is encountered in both the clinic and the hospital.

Here, we review the causes, diagnosis, and management of this disorder.

BENIGN AND MALIGNANT CAUSES

In a retrospective study of 76 patients hospitalized with gastric outlet obstruction between 2006 and 2015 at our institution,2 29 cases (38%) were due to malignancy and 47 (62%) were due to benign causes. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma accounted for 13 cases (17%), while gastric adenocarcinoma accounted for 5 cases (7%); less common malignant causes were cholangiocarcinoma, cancer of the ampulla of Vater, duodenal adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and metastatic disease. Of the benign causes, the most common were peptic ulcer disease (13 cases, 17%) and postoperative strictures or adhesions (11 cases, 14%).

These numbers reflect general trends around the world.

Less gastric cancer, more pancreatic cancer

The last several decades have seen a trend toward more cases due to cancer and fewer due to benign causes.3–14

In earlier studies in both developed and developing countries, gastric adenocarcinoma was the most common malignant cause of gastric outlet obstruction. Since then, it has become less common in Western countries, although it remains more common in Asia and Africa.7–14 This trend likely reflects environmental factors, including decreased prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection, a major risk factor for gastric cancer, in Western countries.15–17

At the same time, pancreatic cancer is on the rise,16 and up to 20% of patients with pancreatic cancer develop gastric outlet obstruction.18 In a prospective observational study of 108 patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction undergoing endoscopic stenting, pancreatic cancer was by far the most common malignancy, occurring in 54% of patients, followed by gastric cancer in 13%.19

Less peptic ulcer disease, but still common

Peptic ulcer disease used to account for up to 90% of cases of gastric outlet obstruction, and it is still the most common benign cause.

In 1990, gastric outlet obstruction was estimated to occur in 5% to 10% of all hospital admissions for ulcer-related complications, accounting for 2,000 operations annually.20,21 Gastric outlet obstruction now occurs in fewer than 5% of patients with duodenal ulcer disease and fewer than 2% of patients with gastric ulcer disease.22

Peptic ulcer disease remains an important cause of obstruction in countries with poor access to acid-suppressing drugs.23

Gastric outlet obstruction occurs in both acute and chronic peptic ulcer disease. In acute peptic ulcer disease, tissue inflammation and edema result in mechanical obstruction. Chronic peptic ulcer disease results in tissue scarring and fibrosis with strictures.20

Environmental factors, including improved diet, hygiene, physical activity, and the decreased prevalence of H pylori infection, also contribute to the decreased prevalence of peptic ulcer disease and its complications, including gastric outlet obstruction.3 The continued occurrence of peptic ulcer disease is associated with widespread use of low-dose aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), the most common causes of peptic ulcer disease in Western countries.24,25

Other nonmalignant causes of gastric outlet obstruction are diverse and less common. They include caustic ingestion, postsurgical strictures, benign tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, Crohn disease, and pancreatic disorders including acute pancreatitis, pancreatic pseudocyst, chronic pancreatitis, and annular pancreas. Intramural duodenal hematoma may cause obstruction after blunt abdominal trauma, endoscopic biopsy, or gastrostomy tube migration, especially in the setting of a bleeding disorder or anticoagulation.26

Tuberculosis should be suspected in countries in which it is common.7 In a prospective study of 64 patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction in India,27 16 (25%) had corrosive injury, 16 (25%) had tuberculosis, and 15 (23%) had peptic ulcer disease. Compared with patients with corrosive injury and peptic ulcer disease, patients with gastroduodenal tuberculosis had the best outcomes with appropriate treatment.

Other reported causes include Bouveret syndrome (an impacted gallstone in the proximal duodenum), phytobezoar, diaphragmatic hernia, gastric volvulus, and Ladd bands (peritoneal bands associated with intestinal malrotation).7,28,29

PRESENTING SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction include nausea, nonbilious vomiting, epigastric pain, early satiety, abdominal distention, and weight loss.

In our patients, the most common presenting symptoms were nausea and vomiting (80%), followed by abdominal pain (72%); weight loss (15%), abdominal distention (15%), and early satiety (9%) were less common.2

Patients with gastric outlet obstruction secondary to malignancy generally present with a shorter duration of symptoms than those with peptic ulcer disease and are more likely to be older.8,13 Other conditions with an acute onset of symptoms include gastric polyp prolapse, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube migration, gastric volvulus, and gallstone impaction.

Patients with gastric outlet obstruction associated with peptic ulcer disease generally have a long-standing history of symptoms, including dyspepsia and weight loss over several years.4

SIGNS ON EXAMINATION

On examination, look for signs of chronic gastric obstruction and its consequences, such as malnutrition, cachexia, volume depletion, and dental erosions.

A succussion splash may suggest gastric outlet obstruction. This is elicited by rocking the patient back and forth by the hips or abdomen while listening over the stomach for a splash, which may be heard without a stethoscope. The test is considered positive if present 3 or more hours after drinking fluids and suggests retention of gastric materials.30,31

In thin individuals, chronic gastric outlet obstruction makes the stomach dilate and hypertrophy, which may be evident by a palpably thickened stomach with visible gastric peristalsis.4

Other notable findings on physical examination may include a palpable abdominal mass, epigastric pain, or an abnormality suggestive of metastatic gastric cancer, such as an enlarged left supraclavicular lymph node (Virchow node) or periumbilical lymph node (Sister Mary Joseph nodule). The Virchow node is at the junction of the thoracic duct and the left subclavian vein where the lymphatic circulation from the body drains into the systemic circulation, and it may be the first sign of gastric cancer.32 Sister Mary Joseph nodule (named after a surgical assistant to Dr. William James Mayo) refers to a palpable mass at the umbilicus, generally resulting from metastasis of an abdominal malignancy.33

SIGNS ON FURTHER STUDIES

Laboratory evaluation may show signs of poor oral intake and electrolyte abnormalities secondary to chronic nausea, vomiting, and dehydration, including hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis and hypokalemia.

The underlying cause of gastric outlet obstruction has major implications for treatment and prognosis and cannot be differentiated by clinical presentation alone.1,9 Diagnosis is based on clinical features and radiologic or endoscopic evaluation consistent with gastric outlet obstruction.

Plain radiography may reveal an enlarged gastric bubble, and contrast studies may be useful to determine whether the obstruction is partial or complete, depending on whether the contrast passes into the small bowel.

Upper endoscopy is often needed to establish the diagnosis and cause. Emptying the stomach with a nasogastric tube is recommended before endoscopy to minimize the risk of aspiration during the procedure, and endotracheal intubation should be considered for airway protection.34 Findings of gastric outlet obstruction on upper endoscopy include retained food and liquid. Endoscopic biopsy is important to differentiate between benign and malignant causes. For patients with malignancy, endoscopic ultrasonography is useful for diagnosis via tissue sampling with fine-needle aspiration and locoregional staging.35

A strategy. Most patients whose clinical presentation suggests gastric outlet obstruction require cross-sectional radiologic imaging, upper endoscopy, or both.36 CT is the preferred imaging study to evaluate for intestinal obstruction.36,37 Patients with suspected complete obstruction or perforation should undergo CT before upper endoscopy. Oral contrast may interfere with endoscopy and should be avoided if endoscopy is planned. Additionally, giving oral contrast may worsen patient discomfort and increase the risk of nausea, vomiting, and aspiration.36,37

Following radiographic evaluation, upper endoscopy can be performed after gastric decompression to identify the location and extent of the obstruction and to potentially provide a definitive diagnosis with biopsy.36

DIFFERENTIATE FROM GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is a chronic neuromuscular disorder characterized by delayed gastric emptying without mechanical obstruction.38 The most common causes are diabetes, surgery, and idiopathy. Other causes include viral infection, connective tissue diseases, ischemia, infiltrative disorders, radiation, neurologic disorders, and paraneoplastic syndromes.39,40

Gastric outlet obstruction and gastroparesis share clinical symptoms including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, early satiety, and weight loss and are important to differentiate.36,38 Although abdominal pain may be present in both gastric outlet obstruction and gastroparesis, in gastroparesis it tends not to be the dominant symptom.40

Gastric scintigraphy is most commonly used to objectively quantify delayed gastric emptying.39 Upper endoscopy is imperative to exclude mechanical obstruction.39

MANAGEMENT

Initially, patients with signs and symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction should be given:

- Nothing by mouth (NPO)

- Intravenous fluids to correct volume depletion and electrolyte abnormalities

- A nasogastric tube for gastric decompression and symptom relief if symptoms persist despite being NPO

- A parenteral proton pump inhibitor, regardless of the cause of obstruction, to decrease gastric secretions41

- Medications for pain and nausea, if needed.

Definitive treatment of gastric outlet obstruction depends on the underlying cause, whether benign or malignant.

Management of benign gastric outlet obstruction

Symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction resolve spontaneously in about half of cases caused by acute peptic ulcer disease, as acute inflammation resolves.9,22

Endoscopic dilation is an important option in patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction, including peptic ulcer disease. Peptic ulcer disease-induced gastric outlet obstruction can be safely treated with endoscopic balloon dilation. This treatment almost always relieves symptoms immediately; however, the long-term response has varied from 16% to 100%, and patients may require more than 1 dilation procedure.25,42,43 The need for 2 or more dilation procedures may predict need for surgery.44 Gastric outlet obstruction after caustic ingestion or endoscopic submucosal dissection may also respond to endoscopic balloon dilation.36

Eradication of H pylori may be effective and lead to complete resolution of symptoms in patients with gastric outlet obstruction due to this infection.45–47

NSAIDs should be discontinued in patients with peptic ulcer disease and gastric outlet obstruction. These drugs damage the gastrointestinal mucosa by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase (COX) enzymes and decreasing synthesis of prostaglandins, which are important for mucosal defense.48 Patients may be unaware of NSAIDs contained in over-the-counter medications and may have difficulty discontinuing NSAIDs taken for pain.49

These drugs are an important cause of refractory peptic ulcer disease and can be detected by platelet COX activity testing, although this test is not widely available. In a study of patients with peptic ulcer disease without definite NSAID use or H pylori infection, up to one-third had evidence of surreptitious NSAID use as detected by platelet COX activity testing.50 In another study,51 platelet COX activity testing discovered over 20% more aspirin users than clinical history alone.

Surgery for patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction is used only when medical management and endoscopic dilation fail. Ideally, surgery should relieve the obstruction and target the underlying cause, such as peptic ulcer disease. Laparoscopic surgery is generally preferred to open surgery because patients can resume oral intake sooner, have a shorter hospital stay, and have less intraoperative blood loss.52 The simplest surgical procedure to relieve obstruction is laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.

Patients with gastric outlet obstruction and peptic ulcer disease warrant laparoscopic vagotomy and antrectomy or distal gastrectomy. This removes the obstruction and the stimulus for gastric secretion.53 An alternative is vagotomy with a drainage procedure (pyloroplasty or gastrojejunostomy), which has a similar postoperative course and reduction in gastric acid secretion compared with antrectomy or distal gastrectomy.53,54

Daily proton pump inhibitors can be used for patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction not associated with peptic ulcer disease or risk factors; for such cases, vagotomy is not required.

Management of malignant gastric outlet obstruction

Patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction may have intractable nausea and abdominal pain secondary to retention of gastric contents. The major goal of therapy is to improve symptoms and restore tolerance of an oral diet. The short-term prognosis of malignant gastric outlet obstruction is poor, with a median survival of 3 to 4 months, as these patients often have unresectable disease.55

Surgical bypass used to be the standard of care for palliation of malignant gastric obstruction, but that was before endoscopic stenting was developed.

Endoscopic stenting allows patients to resume oral intake and get out of the hospital sooner with fewer complications than with open surgical bypass. It may be a more appropriate option for palliation of symptoms in patients with malignant obstruction who have a poor prognosis and prefer a less invasive intervention.55,56

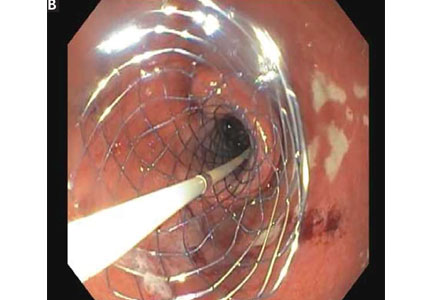

Endoscopic duodenal stenting of malignant gastric outlet obstruction has a success rate of greater than 90%, and most patients can tolerate a mechanical soft diet afterward.34 The procedure is usually performed with a 9-cm or 12-cm self-expanding duodenal stent, 22 mm in diameter, placed over a guide wire under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance (Figure 2). The stent is placed by removing the outer catheter, with distal-to-proximal stent deployment.

Patients who also have biliary obstruction may require biliary stent placement, which is generally performed before duodenal stenting. For patients with an endoscopic stent who develop biliary obstruction, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography can be attempted with placement of a biliary stent; however, these patients may require biliary drain placement by percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography or by endoscopic ultrasonographically guided transduodenal or transgastric biliary drainage.

From 20% to 30% of patients require repeated endoscopic stent placement, although most patients die within several months after stenting.34 Surgical options for patients who do not respond to endoscopic stenting include open or laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.55

Laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy may provide better long-term outcomes than duodenal stenting for patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction and a life expectancy longer than a few months.

A 2017 retrospective study of 155 patients with gastric outlet obstruction secondary to unresectable gastric cancer suggested that those who underwent laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy had better oral intake, better tolerance of chemotherapy, and longer overall survival than those who underwent duodenal stenting. Postsurgical complications were more common in the laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy group (16%) than in the duodenal stenting group (0%).57

In most of the studies comparing endoscopic stenting with surgery, the surgery was open gastrojejunostomy; there are limited data directly comparing stenting with laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.55 Endoscopic stenting is estimated to be significantly less costly than surgery, with a median cost of $12,000 less than gastrojejunostomy.58 As an alternative to enteral stenting and surgical gastrojejunostomy, ultrasonography-guided endoscopic gastrojejunostomy or gastroenterostomy with placement of a lumen-apposing metal stent is emerging as a third treatment option and is under active investigation.59

Patients with malignancy that is potentially curable by resection should undergo surgical evaluation before consideration of endoscopic stenting. For patients who are not candidates for surgery or endoscopic stenting, a percutaneous gastrostomy tube can be considered for gastric decompression and symptom relief.

CASE CONCLUDED

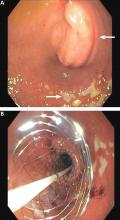

The patient underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with endoscopic ultrasonography for evaluation of her pancreatic mass. Before the procedure, she was intubated to minimize the risk of aspiration due to persistent nausea and retained gastric contents. A large submucosal mass was found in the duodenal bulb. Endoscopic ultrasonography showed a mass within the pancreatic head with pancreatic duct obstruction. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy was performed, and pathology study revealed pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The patient underwent stenting with a 22-mm by 12-cm WallFlex stent (Boston Scientific), which led to resolution of nausea and advancement to a mechanical soft diet on hospital discharge.

She was scheduled for follow-up in the outpatient clinic for treatment of pancreatic cancer.

- Johnson CD. Gastric outlet obstruction malignant until proved otherwise. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90(10):1740. pmid:7572886

- Koop AH, Palmer WC, Mareth K, Burton MC, Bowman A, Stancampiano F. Tu1335 - Pancreatic cancer most common cause of malignant gastric outlet obstruction at a tertiary referral center: a 10 year retrospective study [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2018; 154(6, suppl 1):S-1343.

- Hall R, Royston C, Bardhan KD. The scars of time: the disappearance of peptic ulcer-related pyloric stenosis through the 20th century. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2014; 44(3):201–208. doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2014.303

- Kreel L, Ellis H. Pyloric stenosis in adults: a clinical and radiological study of 100 consecutive patients. Gut 1965; 6(3):253–261. pmid:18668780

- Shone DN, Nikoomanesh P, Smith-Meek MM, Bender JS. Malignancy is the most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction in the era of H2 blockers. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90(10):1769–1770. pmid:7572891

- Ellis H. The diagnosis of benign and malignant pyloric obstruction. Clin Oncol 1976; 2(1):11–15. pmid:1277618

- Samad A, Khanzada TW, Shoukat I. Gastric outlet obstruction: change in etiology. Pak J Surg 2007; 23(1):29–32.

- Chowdhury A, Dhali GK, Banerjee PK. Etiology of gastric outlet obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(8):1679. pmid:8759707

- Johnson CD, Ellis H. Gastric outlet obstruction now predicts malignancy. Br J Surg 1990; 77(9):1023–1024. pmid:2207566

- Misra SP, Dwivedi M, Misra V. Malignancy is the most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction even in a developing country. Endoscopy 1998; 30(5):484–486. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1001313

- Essoun SD, Dakubo JCB. Update of aetiological patterns of adult gastric outlet obstruction in Accra, Ghana. Int J Clin Med 2014; 5(17):1059–1064. doi:10.4236/ijcm.2014.517136

- Jaka H, Mchembe MD, Rambau PF, Chalya PL. Gastric outlet obstruction at Bugando Medical Centre in Northwestern Tanzania: a prospective review of 184 cases. BMC Surg 2013; 13:41. doi:10.1186/1471-2482-13-41

- Sukumar V, Ravindran C, Prasad RV. Demographic and etiological patterns of gastric outlet obstruction in Kerala, South India. N Am J Med Sci 2015; 7(9):403–406. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.166220

- Yoursef M, Mirza MR, Khan S. Gastric outlet obstruction. Pak J Surg 2005; 10(4):48–50.

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015; 136(5):E359–E386. doi:10.1002/ijc.29210

- Parkin DM, Stjernsward J, Muir CS. Estimates of the worldwide frequency of twelve major cancers. Bull World Health Organ 1984; 62(2):163–182. pmid:6610488

- Karimi P, Islami F, Anandasabapathy S, Freedman ND, Kamangar F. Gastric cancer: descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014; 23(5):700–713. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1057

- Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg EW, van Hooft JE, et al; Dutch SUSTENT Study Group. Surgical gastrojejunostomy or endoscopic stent placement for the palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction (SUSTENT) study): a multicenter randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71(3):490–499. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.042

- Tringali A, Didden P, Repici A, et al. Endoscopic treatment of malignant gastric and duodenal strictures: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 79(1):66–75. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2013.06.032

- Malfertheiner P, Chan FK, McColl KE. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet 2009; 374(9699):1449–1461. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60938-7

- Gibson JB, Behrman SW, Fabian TC, Britt LG. Gastric outlet obstruction resulting from peptic ulcer disease requiring surgical intervention is infrequently associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. J Am Coll Surg 2000; 191(1):32–37. pmid:10898181

- Kochhar R, Kochhar S. Endoscopic balloon dilation for benign gastric outlet obstruction in adults. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 2(1):29–35. doi:10.4253/wjge.v2.i1.29

- Kotisso R. Gastric outlet obstruction in Northwestern Ethiopia. East Cent Afr J Surg 2000; 5(2):25-29.

- Hamzaoui L, Bouassida M, Ben Mansour I, et al. Balloon dilatation in patients with gastric outlet obstruction related to peptic ulcer disease. Arab J Gastroenterol 2015; 16(3–4):121–124. doi:10.1016/j.ajg.2015.07.004

- Najm WI. Peptic ulcer disease. Prim Care 2011; 38(3):383–394. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2011.05.001

- Veloso N, Amaro P, Ferreira M, Romaozinho JM, Sofia C. Acute pancreatitis associated with a nontraumatic, intramural duodenal hematoma. Endoscopy 2013; 45(suppl 2):E51–E52. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1325969

- Maharshi S, Puri AS, Sachdeva S, Kumar A, Dalal A, Gupta M. Aetiological spectrum of benign gastric outlet obstruction in India: new trends. Trop Doct 2016; 46(4):186–191. doi:10.1177/0049475515626032

- Sala MA, Ligabo AN, de Arruda MC, Indiani JM, Nacif MS. Intestinal malrotation associated with duodenal obstruction secondary to Ladd’s bands. Radiol Bras 2016; 49(4):271–272. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2015.0106

- Alibegovic E, Kurtcehajic A, Hujdurovic A, Mujagic S, Alibegovic J, Kurtcehajic D. Bouveret syndrome or gallstone ileus. Am J Med 2018; 131(4):e175. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.10.044

- Lau JY, Chung SC, Sung JJ, et al. Through-the-scope balloon dilation for pyloric stenosis: long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc 1996; 43(2 Pt 1):98–101. pmid:8635729

- Ray K, Snowden C, Khatri K, McFall M. Gastric outlet obstruction from a caecal volvulus, herniated through epiploic foramen: a case report. BMJ Case Rep 2009; pii:bcr05.2009.1880. doi:10.1136/bcr.05.2009.1880

- Baumgart DC, Fischer A. Virchow’s node. Lancet 2007; 370(9598):1568. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61661-4

- Dar IH, Kamili MA, Dar SH, Kuchaai FA. Sister Mary Joseph nodule—a case report with review of literature. J Res Med Sci 2009; 14(6):385–387. pmid:21772912

- Tang SJ. Endoscopic stent placement for gastric outlet obstruction. Video Journal and Encyclopedia of GI Endoscopy 2013; 1(1):133–136.

- Valero M, Robles-Medranda C. Endoscopic ultrasound in oncology: an update of clinical applications in the gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(6):243–254.

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Fukami N, Anderson MA, Khan K, et al. The role of endoscopy in gastroduodenal obstruction and gastroparesis. Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 74(1):13–21. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2010.12.003

- Ros PR, Huprich JE. ACR appropriateness criteria on suspected small-bowel obstruction. J Am Coll Radiol 2006; 3(11):838–841. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2006.09.018

- Pasricha PJ, Parkman HP. Gastroparesis: definitions and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2015; 44(1):1–7. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2014.11.001

- Stein B, Everhart KK, Lacy BE. Gastroparesis: a review of current diagnosis and treatment options. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015; 49(7):550–558. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000320

- Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, Abell TL, Gerson L; American College of Gastroenterology. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(1):18–37.

- Gursoy O, Memis D, Sut N. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on gastric juice volume, gastric pH and gastric intramucosal pH in critically ill patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Drug Investig 2008; 28(12):777–782. doi:10.2165/0044011-200828120-00005

- Kuwada SK, Alexander GL. Long-term outcome of endoscopic dilation of nonmalignant pyloric stenosis. Gastrointest Endosc 1995; 41(1):15–17. pmid:7698619

- Kochhar R, Sethy PK, Nagi B, Wig JD. Endoscopic balloon dilatation of benign gastric outlet obstruction. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 19(4):418–422. pmid:15012779

- Perng CL, Lin HJ, Lo WC, Lai CR, Guo WS, Lee SD. Characteristics of patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction requiring surgery after endoscopic balloon dilation. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(5):987–990. pmid:8633593

- Taskin V, Gurer I, Ozyilkan E, Sare M, Hilmioglu F. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on peptic ulcer disease complicated with outlet obstruction. Helicobacter 2000; 5(1):38–40. pmid:10672050

- de Boer WA, Driessen WM. Resolution of gastric outlet obstruction after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Gastroenterol 1995; 21(4):329–330. pmid:8583113

- Tursi A, Cammarota G, Papa A, Montalto M, Fedeli G, Gasbarrini G. Helicobacter pylori eradication helps resolve pyloric and duodenal stenosis. J Clin Gastroenterol 1996; 23(2):157–158. pmid:8877648

- Schmassmann A. Mechanisms of ulcer healing and effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med 1998; 104(3A):43S–51S; discussion 79S–80S. pmid:9572320

- Kim HU. Diagnostic and treatment approaches for refractory peptic ulcers. Clin Endosc 2015; 48(4):285–290. doi:10.5946/ce.2015.48.4.285

- Ong TZ, Hawkey CJ, Ho KY. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use is a significant cause of peptic ulcer disease in a tertiary hospital in Singapore: a prospective study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2006; 40(9):795–800. doi:10.1097/01.mcg.0000225610.41105.7f

- Lanas A, Sekar MC, Hirschowitz BI. Objective evidence of aspirin use in both ulcer and nonulcer upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology 1992; 103(3):862–869. pmid:1499936

- Zhang LP, Tabrizian P, Nguyen S, Telem D, Divino C. Laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy for the treatment of gastric outlet obstruction. JSLS 2011; 15(2):169–173. doi:10.4293/108680811X13022985132074

- Lagoo J, Pappas TN, Perez A. A relic or still relevant: the narrowing role for vagotomy in the treatment of peptic ulcer disease. Am J Surg 2014; 207(1):120–126. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.02.012

- Csendes A, Maluenda F, Braghetto I, Schutte H, Burdiles P, Diaz JC. Prospective randomized study comparing three surgical techniques for the treatment of gastric outlet obstruction secondary to duodenal ulcer. Am J Surg 1993; 166(1):45–49. pmid:8101050

- Ly J, O’Grady G, Mittal A, Plank L, Windsor JA. A systematic review of methods to palliate malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Surg Endosc 2010; 24(2):290–297. doi:10.1007/s00464-009-0577-1

- Goldberg EM. Palliative treatment of gastric outlet obstruction in terminal patients: SEMS. Stent every malignant stricture! Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 79(1):76–78. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2013.07.056

- Min SH, Son SY, Jung DH, et al. Laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy versus duodenal stenting in unresectable gastric cancer with gastric outlet obstruction. Ann Surg Treat Res 2017; 93(3):130–136. doi:10.4174/astr.2017.93.3.130

- Roy A, Kim M, Christein J, Varadarajulu S. Stenting versus gastrojejunostomy for management of malignant gastric outlet obstruction: comparison of clinical outcomes and costs. Surg Endosc 2012; 26(11):3114–119. doi:10.1007/s00464-012-2301-9

- Amin S, Sethi A. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2017; 27(4):707–713. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2017.06.009

A 72-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with progressive nausea and vomiting. One week earlier, she developed early satiety and nausea with vomiting after eating solid food. Three days later her symptoms progressed, and she became unable to take anything by mouth. The patient also experienced a 40-lb weight loss in the previous 3 months. She denies symptoms of abdominal pain, hematemesis, or melena. Her medical history includes cholecystectomy and type 2 diabetes mellitus, diagnosed 1 year ago. She has no family history of gastrointestinal malignancy. She says she smoked 1 pack a day in her 20s. She does not consume alcohol.

On physical examination, she is normotensive with a heart rate of 105 beats per minute. The oral mucosa is dry, and the abdomen is mildly distended and tender to palpation in the epigastrium. Laboratory evaluation reveals hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis.

Computed tomography (CT) reveals a mass 3 cm by 4 cm in the pancreatic head. The mass has invaded the medial wall of the duodenum, with obstruction of the pancreatic and common bile ducts and extension into and occlusion of the superior mesenteric vein, with soft-tissue expansion around the superior mesenteric artery. CT also reveals retained stomach contents and an air-fluid level consistent with gastric outlet obstruction.

INTRINSIC OR EXTRINSIC BLOCKAGE

Gastric outlet obstruction, also called pyloric obstruction, is caused by intrinsic or extrinsic mechanical blockage of gastric emptying, generally in the distal stomach, pyloric channel, or duodenum, with associated symptoms of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and early satiety. It is encountered in both the clinic and the hospital.

Here, we review the causes, diagnosis, and management of this disorder.

BENIGN AND MALIGNANT CAUSES

In a retrospective study of 76 patients hospitalized with gastric outlet obstruction between 2006 and 2015 at our institution,2 29 cases (38%) were due to malignancy and 47 (62%) were due to benign causes. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma accounted for 13 cases (17%), while gastric adenocarcinoma accounted for 5 cases (7%); less common malignant causes were cholangiocarcinoma, cancer of the ampulla of Vater, duodenal adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and metastatic disease. Of the benign causes, the most common were peptic ulcer disease (13 cases, 17%) and postoperative strictures or adhesions (11 cases, 14%).

These numbers reflect general trends around the world.

Less gastric cancer, more pancreatic cancer

The last several decades have seen a trend toward more cases due to cancer and fewer due to benign causes.3–14

In earlier studies in both developed and developing countries, gastric adenocarcinoma was the most common malignant cause of gastric outlet obstruction. Since then, it has become less common in Western countries, although it remains more common in Asia and Africa.7–14 This trend likely reflects environmental factors, including decreased prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection, a major risk factor for gastric cancer, in Western countries.15–17

At the same time, pancreatic cancer is on the rise,16 and up to 20% of patients with pancreatic cancer develop gastric outlet obstruction.18 In a prospective observational study of 108 patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction undergoing endoscopic stenting, pancreatic cancer was by far the most common malignancy, occurring in 54% of patients, followed by gastric cancer in 13%.19

Less peptic ulcer disease, but still common

Peptic ulcer disease used to account for up to 90% of cases of gastric outlet obstruction, and it is still the most common benign cause.

In 1990, gastric outlet obstruction was estimated to occur in 5% to 10% of all hospital admissions for ulcer-related complications, accounting for 2,000 operations annually.20,21 Gastric outlet obstruction now occurs in fewer than 5% of patients with duodenal ulcer disease and fewer than 2% of patients with gastric ulcer disease.22

Peptic ulcer disease remains an important cause of obstruction in countries with poor access to acid-suppressing drugs.23

Gastric outlet obstruction occurs in both acute and chronic peptic ulcer disease. In acute peptic ulcer disease, tissue inflammation and edema result in mechanical obstruction. Chronic peptic ulcer disease results in tissue scarring and fibrosis with strictures.20

Environmental factors, including improved diet, hygiene, physical activity, and the decreased prevalence of H pylori infection, also contribute to the decreased prevalence of peptic ulcer disease and its complications, including gastric outlet obstruction.3 The continued occurrence of peptic ulcer disease is associated with widespread use of low-dose aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), the most common causes of peptic ulcer disease in Western countries.24,25

Other nonmalignant causes of gastric outlet obstruction are diverse and less common. They include caustic ingestion, postsurgical strictures, benign tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, Crohn disease, and pancreatic disorders including acute pancreatitis, pancreatic pseudocyst, chronic pancreatitis, and annular pancreas. Intramural duodenal hematoma may cause obstruction after blunt abdominal trauma, endoscopic biopsy, or gastrostomy tube migration, especially in the setting of a bleeding disorder or anticoagulation.26

Tuberculosis should be suspected in countries in which it is common.7 In a prospective study of 64 patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction in India,27 16 (25%) had corrosive injury, 16 (25%) had tuberculosis, and 15 (23%) had peptic ulcer disease. Compared with patients with corrosive injury and peptic ulcer disease, patients with gastroduodenal tuberculosis had the best outcomes with appropriate treatment.

Other reported causes include Bouveret syndrome (an impacted gallstone in the proximal duodenum), phytobezoar, diaphragmatic hernia, gastric volvulus, and Ladd bands (peritoneal bands associated with intestinal malrotation).7,28,29

PRESENTING SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction include nausea, nonbilious vomiting, epigastric pain, early satiety, abdominal distention, and weight loss.

In our patients, the most common presenting symptoms were nausea and vomiting (80%), followed by abdominal pain (72%); weight loss (15%), abdominal distention (15%), and early satiety (9%) were less common.2

Patients with gastric outlet obstruction secondary to malignancy generally present with a shorter duration of symptoms than those with peptic ulcer disease and are more likely to be older.8,13 Other conditions with an acute onset of symptoms include gastric polyp prolapse, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube migration, gastric volvulus, and gallstone impaction.

Patients with gastric outlet obstruction associated with peptic ulcer disease generally have a long-standing history of symptoms, including dyspepsia and weight loss over several years.4

SIGNS ON EXAMINATION

On examination, look for signs of chronic gastric obstruction and its consequences, such as malnutrition, cachexia, volume depletion, and dental erosions.

A succussion splash may suggest gastric outlet obstruction. This is elicited by rocking the patient back and forth by the hips or abdomen while listening over the stomach for a splash, which may be heard without a stethoscope. The test is considered positive if present 3 or more hours after drinking fluids and suggests retention of gastric materials.30,31

In thin individuals, chronic gastric outlet obstruction makes the stomach dilate and hypertrophy, which may be evident by a palpably thickened stomach with visible gastric peristalsis.4

Other notable findings on physical examination may include a palpable abdominal mass, epigastric pain, or an abnormality suggestive of metastatic gastric cancer, such as an enlarged left supraclavicular lymph node (Virchow node) or periumbilical lymph node (Sister Mary Joseph nodule). The Virchow node is at the junction of the thoracic duct and the left subclavian vein where the lymphatic circulation from the body drains into the systemic circulation, and it may be the first sign of gastric cancer.32 Sister Mary Joseph nodule (named after a surgical assistant to Dr. William James Mayo) refers to a palpable mass at the umbilicus, generally resulting from metastasis of an abdominal malignancy.33

SIGNS ON FURTHER STUDIES

Laboratory evaluation may show signs of poor oral intake and electrolyte abnormalities secondary to chronic nausea, vomiting, and dehydration, including hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis and hypokalemia.

The underlying cause of gastric outlet obstruction has major implications for treatment and prognosis and cannot be differentiated by clinical presentation alone.1,9 Diagnosis is based on clinical features and radiologic or endoscopic evaluation consistent with gastric outlet obstruction.

Plain radiography may reveal an enlarged gastric bubble, and contrast studies may be useful to determine whether the obstruction is partial or complete, depending on whether the contrast passes into the small bowel.

Upper endoscopy is often needed to establish the diagnosis and cause. Emptying the stomach with a nasogastric tube is recommended before endoscopy to minimize the risk of aspiration during the procedure, and endotracheal intubation should be considered for airway protection.34 Findings of gastric outlet obstruction on upper endoscopy include retained food and liquid. Endoscopic biopsy is important to differentiate between benign and malignant causes. For patients with malignancy, endoscopic ultrasonography is useful for diagnosis via tissue sampling with fine-needle aspiration and locoregional staging.35

A strategy. Most patients whose clinical presentation suggests gastric outlet obstruction require cross-sectional radiologic imaging, upper endoscopy, or both.36 CT is the preferred imaging study to evaluate for intestinal obstruction.36,37 Patients with suspected complete obstruction or perforation should undergo CT before upper endoscopy. Oral contrast may interfere with endoscopy and should be avoided if endoscopy is planned. Additionally, giving oral contrast may worsen patient discomfort and increase the risk of nausea, vomiting, and aspiration.36,37

Following radiographic evaluation, upper endoscopy can be performed after gastric decompression to identify the location and extent of the obstruction and to potentially provide a definitive diagnosis with biopsy.36

DIFFERENTIATE FROM GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is a chronic neuromuscular disorder characterized by delayed gastric emptying without mechanical obstruction.38 The most common causes are diabetes, surgery, and idiopathy. Other causes include viral infection, connective tissue diseases, ischemia, infiltrative disorders, radiation, neurologic disorders, and paraneoplastic syndromes.39,40

Gastric outlet obstruction and gastroparesis share clinical symptoms including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, early satiety, and weight loss and are important to differentiate.36,38 Although abdominal pain may be present in both gastric outlet obstruction and gastroparesis, in gastroparesis it tends not to be the dominant symptom.40

Gastric scintigraphy is most commonly used to objectively quantify delayed gastric emptying.39 Upper endoscopy is imperative to exclude mechanical obstruction.39

MANAGEMENT

Initially, patients with signs and symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction should be given:

- Nothing by mouth (NPO)

- Intravenous fluids to correct volume depletion and electrolyte abnormalities

- A nasogastric tube for gastric decompression and symptom relief if symptoms persist despite being NPO

- A parenteral proton pump inhibitor, regardless of the cause of obstruction, to decrease gastric secretions41

- Medications for pain and nausea, if needed.

Definitive treatment of gastric outlet obstruction depends on the underlying cause, whether benign or malignant.

Management of benign gastric outlet obstruction

Symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction resolve spontaneously in about half of cases caused by acute peptic ulcer disease, as acute inflammation resolves.9,22

Endoscopic dilation is an important option in patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction, including peptic ulcer disease. Peptic ulcer disease-induced gastric outlet obstruction can be safely treated with endoscopic balloon dilation. This treatment almost always relieves symptoms immediately; however, the long-term response has varied from 16% to 100%, and patients may require more than 1 dilation procedure.25,42,43 The need for 2 or more dilation procedures may predict need for surgery.44 Gastric outlet obstruction after caustic ingestion or endoscopic submucosal dissection may also respond to endoscopic balloon dilation.36

Eradication of H pylori may be effective and lead to complete resolution of symptoms in patients with gastric outlet obstruction due to this infection.45–47

NSAIDs should be discontinued in patients with peptic ulcer disease and gastric outlet obstruction. These drugs damage the gastrointestinal mucosa by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase (COX) enzymes and decreasing synthesis of prostaglandins, which are important for mucosal defense.48 Patients may be unaware of NSAIDs contained in over-the-counter medications and may have difficulty discontinuing NSAIDs taken for pain.49

These drugs are an important cause of refractory peptic ulcer disease and can be detected by platelet COX activity testing, although this test is not widely available. In a study of patients with peptic ulcer disease without definite NSAID use or H pylori infection, up to one-third had evidence of surreptitious NSAID use as detected by platelet COX activity testing.50 In another study,51 platelet COX activity testing discovered over 20% more aspirin users than clinical history alone.

Surgery for patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction is used only when medical management and endoscopic dilation fail. Ideally, surgery should relieve the obstruction and target the underlying cause, such as peptic ulcer disease. Laparoscopic surgery is generally preferred to open surgery because patients can resume oral intake sooner, have a shorter hospital stay, and have less intraoperative blood loss.52 The simplest surgical procedure to relieve obstruction is laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.

Patients with gastric outlet obstruction and peptic ulcer disease warrant laparoscopic vagotomy and antrectomy or distal gastrectomy. This removes the obstruction and the stimulus for gastric secretion.53 An alternative is vagotomy with a drainage procedure (pyloroplasty or gastrojejunostomy), which has a similar postoperative course and reduction in gastric acid secretion compared with antrectomy or distal gastrectomy.53,54

Daily proton pump inhibitors can be used for patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction not associated with peptic ulcer disease or risk factors; for such cases, vagotomy is not required.

Management of malignant gastric outlet obstruction

Patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction may have intractable nausea and abdominal pain secondary to retention of gastric contents. The major goal of therapy is to improve symptoms and restore tolerance of an oral diet. The short-term prognosis of malignant gastric outlet obstruction is poor, with a median survival of 3 to 4 months, as these patients often have unresectable disease.55

Surgical bypass used to be the standard of care for palliation of malignant gastric obstruction, but that was before endoscopic stenting was developed.

Endoscopic stenting allows patients to resume oral intake and get out of the hospital sooner with fewer complications than with open surgical bypass. It may be a more appropriate option for palliation of symptoms in patients with malignant obstruction who have a poor prognosis and prefer a less invasive intervention.55,56

Endoscopic duodenal stenting of malignant gastric outlet obstruction has a success rate of greater than 90%, and most patients can tolerate a mechanical soft diet afterward.34 The procedure is usually performed with a 9-cm or 12-cm self-expanding duodenal stent, 22 mm in diameter, placed over a guide wire under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance (Figure 2). The stent is placed by removing the outer catheter, with distal-to-proximal stent deployment.

Patients who also have biliary obstruction may require biliary stent placement, which is generally performed before duodenal stenting. For patients with an endoscopic stent who develop biliary obstruction, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography can be attempted with placement of a biliary stent; however, these patients may require biliary drain placement by percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography or by endoscopic ultrasonographically guided transduodenal or transgastric biliary drainage.

From 20% to 30% of patients require repeated endoscopic stent placement, although most patients die within several months after stenting.34 Surgical options for patients who do not respond to endoscopic stenting include open or laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.55

Laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy may provide better long-term outcomes than duodenal stenting for patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction and a life expectancy longer than a few months.

A 2017 retrospective study of 155 patients with gastric outlet obstruction secondary to unresectable gastric cancer suggested that those who underwent laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy had better oral intake, better tolerance of chemotherapy, and longer overall survival than those who underwent duodenal stenting. Postsurgical complications were more common in the laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy group (16%) than in the duodenal stenting group (0%).57

In most of the studies comparing endoscopic stenting with surgery, the surgery was open gastrojejunostomy; there are limited data directly comparing stenting with laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.55 Endoscopic stenting is estimated to be significantly less costly than surgery, with a median cost of $12,000 less than gastrojejunostomy.58 As an alternative to enteral stenting and surgical gastrojejunostomy, ultrasonography-guided endoscopic gastrojejunostomy or gastroenterostomy with placement of a lumen-apposing metal stent is emerging as a third treatment option and is under active investigation.59

Patients with malignancy that is potentially curable by resection should undergo surgical evaluation before consideration of endoscopic stenting. For patients who are not candidates for surgery or endoscopic stenting, a percutaneous gastrostomy tube can be considered for gastric decompression and symptom relief.

CASE CONCLUDED

The patient underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with endoscopic ultrasonography for evaluation of her pancreatic mass. Before the procedure, she was intubated to minimize the risk of aspiration due to persistent nausea and retained gastric contents. A large submucosal mass was found in the duodenal bulb. Endoscopic ultrasonography showed a mass within the pancreatic head with pancreatic duct obstruction. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy was performed, and pathology study revealed pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The patient underwent stenting with a 22-mm by 12-cm WallFlex stent (Boston Scientific), which led to resolution of nausea and advancement to a mechanical soft diet on hospital discharge.

She was scheduled for follow-up in the outpatient clinic for treatment of pancreatic cancer.

A 72-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with progressive nausea and vomiting. One week earlier, she developed early satiety and nausea with vomiting after eating solid food. Three days later her symptoms progressed, and she became unable to take anything by mouth. The patient also experienced a 40-lb weight loss in the previous 3 months. She denies symptoms of abdominal pain, hematemesis, or melena. Her medical history includes cholecystectomy and type 2 diabetes mellitus, diagnosed 1 year ago. She has no family history of gastrointestinal malignancy. She says she smoked 1 pack a day in her 20s. She does not consume alcohol.

On physical examination, she is normotensive with a heart rate of 105 beats per minute. The oral mucosa is dry, and the abdomen is mildly distended and tender to palpation in the epigastrium. Laboratory evaluation reveals hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis.

Computed tomography (CT) reveals a mass 3 cm by 4 cm in the pancreatic head. The mass has invaded the medial wall of the duodenum, with obstruction of the pancreatic and common bile ducts and extension into and occlusion of the superior mesenteric vein, with soft-tissue expansion around the superior mesenteric artery. CT also reveals retained stomach contents and an air-fluid level consistent with gastric outlet obstruction.

INTRINSIC OR EXTRINSIC BLOCKAGE

Gastric outlet obstruction, also called pyloric obstruction, is caused by intrinsic or extrinsic mechanical blockage of gastric emptying, generally in the distal stomach, pyloric channel, or duodenum, with associated symptoms of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and early satiety. It is encountered in both the clinic and the hospital.

Here, we review the causes, diagnosis, and management of this disorder.

BENIGN AND MALIGNANT CAUSES

In a retrospective study of 76 patients hospitalized with gastric outlet obstruction between 2006 and 2015 at our institution,2 29 cases (38%) were due to malignancy and 47 (62%) were due to benign causes. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma accounted for 13 cases (17%), while gastric adenocarcinoma accounted for 5 cases (7%); less common malignant causes were cholangiocarcinoma, cancer of the ampulla of Vater, duodenal adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and metastatic disease. Of the benign causes, the most common were peptic ulcer disease (13 cases, 17%) and postoperative strictures or adhesions (11 cases, 14%).

These numbers reflect general trends around the world.

Less gastric cancer, more pancreatic cancer

The last several decades have seen a trend toward more cases due to cancer and fewer due to benign causes.3–14

In earlier studies in both developed and developing countries, gastric adenocarcinoma was the most common malignant cause of gastric outlet obstruction. Since then, it has become less common in Western countries, although it remains more common in Asia and Africa.7–14 This trend likely reflects environmental factors, including decreased prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection, a major risk factor for gastric cancer, in Western countries.15–17

At the same time, pancreatic cancer is on the rise,16 and up to 20% of patients with pancreatic cancer develop gastric outlet obstruction.18 In a prospective observational study of 108 patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction undergoing endoscopic stenting, pancreatic cancer was by far the most common malignancy, occurring in 54% of patients, followed by gastric cancer in 13%.19

Less peptic ulcer disease, but still common

Peptic ulcer disease used to account for up to 90% of cases of gastric outlet obstruction, and it is still the most common benign cause.

In 1990, gastric outlet obstruction was estimated to occur in 5% to 10% of all hospital admissions for ulcer-related complications, accounting for 2,000 operations annually.20,21 Gastric outlet obstruction now occurs in fewer than 5% of patients with duodenal ulcer disease and fewer than 2% of patients with gastric ulcer disease.22

Peptic ulcer disease remains an important cause of obstruction in countries with poor access to acid-suppressing drugs.23

Gastric outlet obstruction occurs in both acute and chronic peptic ulcer disease. In acute peptic ulcer disease, tissue inflammation and edema result in mechanical obstruction. Chronic peptic ulcer disease results in tissue scarring and fibrosis with strictures.20

Environmental factors, including improved diet, hygiene, physical activity, and the decreased prevalence of H pylori infection, also contribute to the decreased prevalence of peptic ulcer disease and its complications, including gastric outlet obstruction.3 The continued occurrence of peptic ulcer disease is associated with widespread use of low-dose aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), the most common causes of peptic ulcer disease in Western countries.24,25

Other nonmalignant causes of gastric outlet obstruction are diverse and less common. They include caustic ingestion, postsurgical strictures, benign tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, Crohn disease, and pancreatic disorders including acute pancreatitis, pancreatic pseudocyst, chronic pancreatitis, and annular pancreas. Intramural duodenal hematoma may cause obstruction after blunt abdominal trauma, endoscopic biopsy, or gastrostomy tube migration, especially in the setting of a bleeding disorder or anticoagulation.26

Tuberculosis should be suspected in countries in which it is common.7 In a prospective study of 64 patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction in India,27 16 (25%) had corrosive injury, 16 (25%) had tuberculosis, and 15 (23%) had peptic ulcer disease. Compared with patients with corrosive injury and peptic ulcer disease, patients with gastroduodenal tuberculosis had the best outcomes with appropriate treatment.

Other reported causes include Bouveret syndrome (an impacted gallstone in the proximal duodenum), phytobezoar, diaphragmatic hernia, gastric volvulus, and Ladd bands (peritoneal bands associated with intestinal malrotation).7,28,29

PRESENTING SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction include nausea, nonbilious vomiting, epigastric pain, early satiety, abdominal distention, and weight loss.

In our patients, the most common presenting symptoms were nausea and vomiting (80%), followed by abdominal pain (72%); weight loss (15%), abdominal distention (15%), and early satiety (9%) were less common.2

Patients with gastric outlet obstruction secondary to malignancy generally present with a shorter duration of symptoms than those with peptic ulcer disease and are more likely to be older.8,13 Other conditions with an acute onset of symptoms include gastric polyp prolapse, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube migration, gastric volvulus, and gallstone impaction.

Patients with gastric outlet obstruction associated with peptic ulcer disease generally have a long-standing history of symptoms, including dyspepsia and weight loss over several years.4

SIGNS ON EXAMINATION

On examination, look for signs of chronic gastric obstruction and its consequences, such as malnutrition, cachexia, volume depletion, and dental erosions.

A succussion splash may suggest gastric outlet obstruction. This is elicited by rocking the patient back and forth by the hips or abdomen while listening over the stomach for a splash, which may be heard without a stethoscope. The test is considered positive if present 3 or more hours after drinking fluids and suggests retention of gastric materials.30,31

In thin individuals, chronic gastric outlet obstruction makes the stomach dilate and hypertrophy, which may be evident by a palpably thickened stomach with visible gastric peristalsis.4

Other notable findings on physical examination may include a palpable abdominal mass, epigastric pain, or an abnormality suggestive of metastatic gastric cancer, such as an enlarged left supraclavicular lymph node (Virchow node) or periumbilical lymph node (Sister Mary Joseph nodule). The Virchow node is at the junction of the thoracic duct and the left subclavian vein where the lymphatic circulation from the body drains into the systemic circulation, and it may be the first sign of gastric cancer.32 Sister Mary Joseph nodule (named after a surgical assistant to Dr. William James Mayo) refers to a palpable mass at the umbilicus, generally resulting from metastasis of an abdominal malignancy.33

SIGNS ON FURTHER STUDIES

Laboratory evaluation may show signs of poor oral intake and electrolyte abnormalities secondary to chronic nausea, vomiting, and dehydration, including hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis and hypokalemia.

The underlying cause of gastric outlet obstruction has major implications for treatment and prognosis and cannot be differentiated by clinical presentation alone.1,9 Diagnosis is based on clinical features and radiologic or endoscopic evaluation consistent with gastric outlet obstruction.

Plain radiography may reveal an enlarged gastric bubble, and contrast studies may be useful to determine whether the obstruction is partial or complete, depending on whether the contrast passes into the small bowel.

Upper endoscopy is often needed to establish the diagnosis and cause. Emptying the stomach with a nasogastric tube is recommended before endoscopy to minimize the risk of aspiration during the procedure, and endotracheal intubation should be considered for airway protection.34 Findings of gastric outlet obstruction on upper endoscopy include retained food and liquid. Endoscopic biopsy is important to differentiate between benign and malignant causes. For patients with malignancy, endoscopic ultrasonography is useful for diagnosis via tissue sampling with fine-needle aspiration and locoregional staging.35

A strategy. Most patients whose clinical presentation suggests gastric outlet obstruction require cross-sectional radiologic imaging, upper endoscopy, or both.36 CT is the preferred imaging study to evaluate for intestinal obstruction.36,37 Patients with suspected complete obstruction or perforation should undergo CT before upper endoscopy. Oral contrast may interfere with endoscopy and should be avoided if endoscopy is planned. Additionally, giving oral contrast may worsen patient discomfort and increase the risk of nausea, vomiting, and aspiration.36,37

Following radiographic evaluation, upper endoscopy can be performed after gastric decompression to identify the location and extent of the obstruction and to potentially provide a definitive diagnosis with biopsy.36

DIFFERENTIATE FROM GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is a chronic neuromuscular disorder characterized by delayed gastric emptying without mechanical obstruction.38 The most common causes are diabetes, surgery, and idiopathy. Other causes include viral infection, connective tissue diseases, ischemia, infiltrative disorders, radiation, neurologic disorders, and paraneoplastic syndromes.39,40

Gastric outlet obstruction and gastroparesis share clinical symptoms including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, early satiety, and weight loss and are important to differentiate.36,38 Although abdominal pain may be present in both gastric outlet obstruction and gastroparesis, in gastroparesis it tends not to be the dominant symptom.40

Gastric scintigraphy is most commonly used to objectively quantify delayed gastric emptying.39 Upper endoscopy is imperative to exclude mechanical obstruction.39

MANAGEMENT

Initially, patients with signs and symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction should be given:

- Nothing by mouth (NPO)

- Intravenous fluids to correct volume depletion and electrolyte abnormalities

- A nasogastric tube for gastric decompression and symptom relief if symptoms persist despite being NPO

- A parenteral proton pump inhibitor, regardless of the cause of obstruction, to decrease gastric secretions41

- Medications for pain and nausea, if needed.

Definitive treatment of gastric outlet obstruction depends on the underlying cause, whether benign or malignant.

Management of benign gastric outlet obstruction

Symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction resolve spontaneously in about half of cases caused by acute peptic ulcer disease, as acute inflammation resolves.9,22

Endoscopic dilation is an important option in patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction, including peptic ulcer disease. Peptic ulcer disease-induced gastric outlet obstruction can be safely treated with endoscopic balloon dilation. This treatment almost always relieves symptoms immediately; however, the long-term response has varied from 16% to 100%, and patients may require more than 1 dilation procedure.25,42,43 The need for 2 or more dilation procedures may predict need for surgery.44 Gastric outlet obstruction after caustic ingestion or endoscopic submucosal dissection may also respond to endoscopic balloon dilation.36

Eradication of H pylori may be effective and lead to complete resolution of symptoms in patients with gastric outlet obstruction due to this infection.45–47

NSAIDs should be discontinued in patients with peptic ulcer disease and gastric outlet obstruction. These drugs damage the gastrointestinal mucosa by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase (COX) enzymes and decreasing synthesis of prostaglandins, which are important for mucosal defense.48 Patients may be unaware of NSAIDs contained in over-the-counter medications and may have difficulty discontinuing NSAIDs taken for pain.49

These drugs are an important cause of refractory peptic ulcer disease and can be detected by platelet COX activity testing, although this test is not widely available. In a study of patients with peptic ulcer disease without definite NSAID use or H pylori infection, up to one-third had evidence of surreptitious NSAID use as detected by platelet COX activity testing.50 In another study,51 platelet COX activity testing discovered over 20% more aspirin users than clinical history alone.

Surgery for patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction is used only when medical management and endoscopic dilation fail. Ideally, surgery should relieve the obstruction and target the underlying cause, such as peptic ulcer disease. Laparoscopic surgery is generally preferred to open surgery because patients can resume oral intake sooner, have a shorter hospital stay, and have less intraoperative blood loss.52 The simplest surgical procedure to relieve obstruction is laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.

Patients with gastric outlet obstruction and peptic ulcer disease warrant laparoscopic vagotomy and antrectomy or distal gastrectomy. This removes the obstruction and the stimulus for gastric secretion.53 An alternative is vagotomy with a drainage procedure (pyloroplasty or gastrojejunostomy), which has a similar postoperative course and reduction in gastric acid secretion compared with antrectomy or distal gastrectomy.53,54

Daily proton pump inhibitors can be used for patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction not associated with peptic ulcer disease or risk factors; for such cases, vagotomy is not required.

Management of malignant gastric outlet obstruction

Patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction may have intractable nausea and abdominal pain secondary to retention of gastric contents. The major goal of therapy is to improve symptoms and restore tolerance of an oral diet. The short-term prognosis of malignant gastric outlet obstruction is poor, with a median survival of 3 to 4 months, as these patients often have unresectable disease.55

Surgical bypass used to be the standard of care for palliation of malignant gastric obstruction, but that was before endoscopic stenting was developed.

Endoscopic stenting allows patients to resume oral intake and get out of the hospital sooner with fewer complications than with open surgical bypass. It may be a more appropriate option for palliation of symptoms in patients with malignant obstruction who have a poor prognosis and prefer a less invasive intervention.55,56

Endoscopic duodenal stenting of malignant gastric outlet obstruction has a success rate of greater than 90%, and most patients can tolerate a mechanical soft diet afterward.34 The procedure is usually performed with a 9-cm or 12-cm self-expanding duodenal stent, 22 mm in diameter, placed over a guide wire under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance (Figure 2). The stent is placed by removing the outer catheter, with distal-to-proximal stent deployment.

Patients who also have biliary obstruction may require biliary stent placement, which is generally performed before duodenal stenting. For patients with an endoscopic stent who develop biliary obstruction, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography can be attempted with placement of a biliary stent; however, these patients may require biliary drain placement by percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography or by endoscopic ultrasonographically guided transduodenal or transgastric biliary drainage.

From 20% to 30% of patients require repeated endoscopic stent placement, although most patients die within several months after stenting.34 Surgical options for patients who do not respond to endoscopic stenting include open or laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.55

Laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy may provide better long-term outcomes than duodenal stenting for patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction and a life expectancy longer than a few months.

A 2017 retrospective study of 155 patients with gastric outlet obstruction secondary to unresectable gastric cancer suggested that those who underwent laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy had better oral intake, better tolerance of chemotherapy, and longer overall survival than those who underwent duodenal stenting. Postsurgical complications were more common in the laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy group (16%) than in the duodenal stenting group (0%).57

In most of the studies comparing endoscopic stenting with surgery, the surgery was open gastrojejunostomy; there are limited data directly comparing stenting with laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.55 Endoscopic stenting is estimated to be significantly less costly than surgery, with a median cost of $12,000 less than gastrojejunostomy.58 As an alternative to enteral stenting and surgical gastrojejunostomy, ultrasonography-guided endoscopic gastrojejunostomy or gastroenterostomy with placement of a lumen-apposing metal stent is emerging as a third treatment option and is under active investigation.59

Patients with malignancy that is potentially curable by resection should undergo surgical evaluation before consideration of endoscopic stenting. For patients who are not candidates for surgery or endoscopic stenting, a percutaneous gastrostomy tube can be considered for gastric decompression and symptom relief.

CASE CONCLUDED

The patient underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with endoscopic ultrasonography for evaluation of her pancreatic mass. Before the procedure, she was intubated to minimize the risk of aspiration due to persistent nausea and retained gastric contents. A large submucosal mass was found in the duodenal bulb. Endoscopic ultrasonography showed a mass within the pancreatic head with pancreatic duct obstruction. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy was performed, and pathology study revealed pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The patient underwent stenting with a 22-mm by 12-cm WallFlex stent (Boston Scientific), which led to resolution of nausea and advancement to a mechanical soft diet on hospital discharge.

She was scheduled for follow-up in the outpatient clinic for treatment of pancreatic cancer.

- Johnson CD. Gastric outlet obstruction malignant until proved otherwise. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90(10):1740. pmid:7572886

- Koop AH, Palmer WC, Mareth K, Burton MC, Bowman A, Stancampiano F. Tu1335 - Pancreatic cancer most common cause of malignant gastric outlet obstruction at a tertiary referral center: a 10 year retrospective study [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2018; 154(6, suppl 1):S-1343.

- Hall R, Royston C, Bardhan KD. The scars of time: the disappearance of peptic ulcer-related pyloric stenosis through the 20th century. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2014; 44(3):201–208. doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2014.303

- Kreel L, Ellis H. Pyloric stenosis in adults: a clinical and radiological study of 100 consecutive patients. Gut 1965; 6(3):253–261. pmid:18668780

- Shone DN, Nikoomanesh P, Smith-Meek MM, Bender JS. Malignancy is the most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction in the era of H2 blockers. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90(10):1769–1770. pmid:7572891

- Ellis H. The diagnosis of benign and malignant pyloric obstruction. Clin Oncol 1976; 2(1):11–15. pmid:1277618

- Samad A, Khanzada TW, Shoukat I. Gastric outlet obstruction: change in etiology. Pak J Surg 2007; 23(1):29–32.

- Chowdhury A, Dhali GK, Banerjee PK. Etiology of gastric outlet obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(8):1679. pmid:8759707

- Johnson CD, Ellis H. Gastric outlet obstruction now predicts malignancy. Br J Surg 1990; 77(9):1023–1024. pmid:2207566

- Misra SP, Dwivedi M, Misra V. Malignancy is the most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction even in a developing country. Endoscopy 1998; 30(5):484–486. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1001313

- Essoun SD, Dakubo JCB. Update of aetiological patterns of adult gastric outlet obstruction in Accra, Ghana. Int J Clin Med 2014; 5(17):1059–1064. doi:10.4236/ijcm.2014.517136

- Jaka H, Mchembe MD, Rambau PF, Chalya PL. Gastric outlet obstruction at Bugando Medical Centre in Northwestern Tanzania: a prospective review of 184 cases. BMC Surg 2013; 13:41. doi:10.1186/1471-2482-13-41

- Sukumar V, Ravindran C, Prasad RV. Demographic and etiological patterns of gastric outlet obstruction in Kerala, South India. N Am J Med Sci 2015; 7(9):403–406. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.166220

- Yoursef M, Mirza MR, Khan S. Gastric outlet obstruction. Pak J Surg 2005; 10(4):48–50.

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015; 136(5):E359–E386. doi:10.1002/ijc.29210

- Parkin DM, Stjernsward J, Muir CS. Estimates of the worldwide frequency of twelve major cancers. Bull World Health Organ 1984; 62(2):163–182. pmid:6610488

- Karimi P, Islami F, Anandasabapathy S, Freedman ND, Kamangar F. Gastric cancer: descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014; 23(5):700–713. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1057

- Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg EW, van Hooft JE, et al; Dutch SUSTENT Study Group. Surgical gastrojejunostomy or endoscopic stent placement for the palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction (SUSTENT) study): a multicenter randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71(3):490–499. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.042

- Tringali A, Didden P, Repici A, et al. Endoscopic treatment of malignant gastric and duodenal strictures: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 79(1):66–75. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2013.06.032

- Malfertheiner P, Chan FK, McColl KE. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet 2009; 374(9699):1449–1461. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60938-7

- Gibson JB, Behrman SW, Fabian TC, Britt LG. Gastric outlet obstruction resulting from peptic ulcer disease requiring surgical intervention is infrequently associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. J Am Coll Surg 2000; 191(1):32–37. pmid:10898181

- Kochhar R, Kochhar S. Endoscopic balloon dilation for benign gastric outlet obstruction in adults. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 2(1):29–35. doi:10.4253/wjge.v2.i1.29

- Kotisso R. Gastric outlet obstruction in Northwestern Ethiopia. East Cent Afr J Surg 2000; 5(2):25-29.

- Hamzaoui L, Bouassida M, Ben Mansour I, et al. Balloon dilatation in patients with gastric outlet obstruction related to peptic ulcer disease. Arab J Gastroenterol 2015; 16(3–4):121–124. doi:10.1016/j.ajg.2015.07.004

- Najm WI. Peptic ulcer disease. Prim Care 2011; 38(3):383–394. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2011.05.001

- Veloso N, Amaro P, Ferreira M, Romaozinho JM, Sofia C. Acute pancreatitis associated with a nontraumatic, intramural duodenal hematoma. Endoscopy 2013; 45(suppl 2):E51–E52. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1325969

- Maharshi S, Puri AS, Sachdeva S, Kumar A, Dalal A, Gupta M. Aetiological spectrum of benign gastric outlet obstruction in India: new trends. Trop Doct 2016; 46(4):186–191. doi:10.1177/0049475515626032

- Sala MA, Ligabo AN, de Arruda MC, Indiani JM, Nacif MS. Intestinal malrotation associated with duodenal obstruction secondary to Ladd’s bands. Radiol Bras 2016; 49(4):271–272. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2015.0106

- Alibegovic E, Kurtcehajic A, Hujdurovic A, Mujagic S, Alibegovic J, Kurtcehajic D. Bouveret syndrome or gallstone ileus. Am J Med 2018; 131(4):e175. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.10.044

- Lau JY, Chung SC, Sung JJ, et al. Through-the-scope balloon dilation for pyloric stenosis: long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc 1996; 43(2 Pt 1):98–101. pmid:8635729

- Ray K, Snowden C, Khatri K, McFall M. Gastric outlet obstruction from a caecal volvulus, herniated through epiploic foramen: a case report. BMJ Case Rep 2009; pii:bcr05.2009.1880. doi:10.1136/bcr.05.2009.1880

- Baumgart DC, Fischer A. Virchow’s node. Lancet 2007; 370(9598):1568. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61661-4

- Dar IH, Kamili MA, Dar SH, Kuchaai FA. Sister Mary Joseph nodule—a case report with review of literature. J Res Med Sci 2009; 14(6):385–387. pmid:21772912

- Tang SJ. Endoscopic stent placement for gastric outlet obstruction. Video Journal and Encyclopedia of GI Endoscopy 2013; 1(1):133–136.

- Valero M, Robles-Medranda C. Endoscopic ultrasound in oncology: an update of clinical applications in the gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(6):243–254.

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Fukami N, Anderson MA, Khan K, et al. The role of endoscopy in gastroduodenal obstruction and gastroparesis. Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 74(1):13–21. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2010.12.003

- Ros PR, Huprich JE. ACR appropriateness criteria on suspected small-bowel obstruction. J Am Coll Radiol 2006; 3(11):838–841. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2006.09.018

- Pasricha PJ, Parkman HP. Gastroparesis: definitions and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2015; 44(1):1–7. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2014.11.001

- Stein B, Everhart KK, Lacy BE. Gastroparesis: a review of current diagnosis and treatment options. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015; 49(7):550–558. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000320

- Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, Abell TL, Gerson L; American College of Gastroenterology. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(1):18–37.

- Gursoy O, Memis D, Sut N. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on gastric juice volume, gastric pH and gastric intramucosal pH in critically ill patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Drug Investig 2008; 28(12):777–782. doi:10.2165/0044011-200828120-00005

- Kuwada SK, Alexander GL. Long-term outcome of endoscopic dilation of nonmalignant pyloric stenosis. Gastrointest Endosc 1995; 41(1):15–17. pmid:7698619

- Kochhar R, Sethy PK, Nagi B, Wig JD. Endoscopic balloon dilatation of benign gastric outlet obstruction. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 19(4):418–422. pmid:15012779

- Perng CL, Lin HJ, Lo WC, Lai CR, Guo WS, Lee SD. Characteristics of patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction requiring surgery after endoscopic balloon dilation. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(5):987–990. pmid:8633593

- Taskin V, Gurer I, Ozyilkan E, Sare M, Hilmioglu F. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on peptic ulcer disease complicated with outlet obstruction. Helicobacter 2000; 5(1):38–40. pmid:10672050

- de Boer WA, Driessen WM. Resolution of gastric outlet obstruction after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Gastroenterol 1995; 21(4):329–330. pmid:8583113

- Tursi A, Cammarota G, Papa A, Montalto M, Fedeli G, Gasbarrini G. Helicobacter pylori eradication helps resolve pyloric and duodenal stenosis. J Clin Gastroenterol 1996; 23(2):157–158. pmid:8877648

- Schmassmann A. Mechanisms of ulcer healing and effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med 1998; 104(3A):43S–51S; discussion 79S–80S. pmid:9572320