User login

Remove the black-box warning for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate!

- Update on contraception

Rachel B. Rapkin, MD; Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (August 2011) - 10 (+1) practical, evidence-based recommendations for you to improve contraceptive care now

Colleen Krajewski, MD; Mark D. Walters, MD (August 2011) - Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other?

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; March 2011) - IUD use in nulliparous and adolescent women

Jennefer A. Russo, MD; Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (Update on Contraception, August 2010)

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should remove the black-box warning regarding skeletal health that the agency inserted into labeling for the injectable contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA; Depo-Provera) in 2004. The black box 1) indicates that use of DMPA for longer than 2 years may reduce peak bone mass and place a woman at increased risk of osteoporotic fracture and 2) suggests that ObGyns order bone-density assessment in women who use DMPA long-term.

This warning is not based on scientific evidence. By depriving women of long-term use of a safe, effective contraceptive, the black-box warning damages women’s health and the public health.

The scientific argument for removing the black box

Although DMPA does cause reduced ovarian estradiol production, with a decline in bone mineral density (BMD), complete recovery of BMD occurs approximately 1 or 2 years after discontinuation in adolescent girls1,2 and 3 years after discontinuation in adult women.3,4 BMD trends observed with the use of DMPA parallel those associated with another normal but hypoestrogenic state: breastfeeding. Although BMD declines noted in nursing mothers are similar to those associated with DMPA, breastfeeding one or more infants has not been reported to increase the risk of subsequent osteoporotic fractures.5 The FDA does not warn women against breastfeeding for fear of a theoretical negative impact on skeletal health.

BMD can help predict a risk of osteoporotic fracture in menopausal women, but it is not a valid surrogate endpoint for fracture in women of reproductive age.6 Basing clinical recommendations on invalid surrogate endpoints can cause harm.7-9 Clinical recommendations, including those from the FDA, should be based on sound studies that address important clinical outcomes.

No convincing evidence links the use of DMPA for contraception to fracture. Studies of menopausal women have not suggested that prior use of DMPA increased their risk of osteoporosis.10-12 Two recently published case-control studies, one using a Danish National Patient Registry13 and one based on the United Kingdom Family Practice Research database,14 have demonstrated that DMPA is associated with an elevated risk of fracture in reproductive-age women. However, a cohort analysis using the same British Family Practice database clarifies that the elevated fracture risk observed in women using DMPA occurred before initiation of injectable contraception and was not the result of DMPA use.15

A clearly harmful effect on women’s health

The black-box warning for DMPA has caused clinicians and women to reduce use of this effective method of contraception. The 2008 National Survey of Family Growth shows that the overall percentage of US women, 15 to 44 years of age, who now use DMPA has declined—from 3.3% in 2002 to 2.0% in 2006 to 2008.16

In fact, a survey of ObGyns in Florida found that 1) almost one half of respondents place a time limit on duration of DMPA and 2) two thirds of those respondents base that restriction on the black-box warning.17 Restricting the use of DMPA can lead to more unintended pregnancies and induced abortions.

In the Florida survey, two thirds of respondents order BMD assessment in women who use DMPA, with 58% of those physicians who do so attributing their decision to, again, the black-box warning. Indeed, more than 5% of respondents reported that they selectively prescribe bisphosphonates to women of reproductive age who use DMPA—an expensive practice that is not evidence-based and is potentially dangerous.

FDA guidance is far out of step

The black-box warning for DMPA is not in accord with the guidance provided major medical and public health organizations. The World Health Organization,6 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,18 the Society for Adolescent Medicine,19 and the Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Canada,20 have all stated that skeletal health concerns shouldn’t restrict the use of DMPA, including the duration of use.

In the US Medical Eligibility Criteria for contraceptive use, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared that use of DMPA is Category 1 (no restriction on use) in women 18 to 45 years of age and Category 2 (advantages of the method generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks) in younger women.21 The FDA’s black-box warning is therefore inconsistent with the recommendation of its sister agency.

An opportunity to improve the health of women

The FDA appropriately takes action when a pharmaceutical company mislabels a product or promotes it in a way that isn’t based on sound evidence. Shouldn’t the FDA apply the same scientific standards to itself? Guidance included in DMPA’s black box is not evidence-based—and that reduces use of DMPA in US women and increases the potential for harm. Removing the black box would encourage use of this convenient, effective, and safe contraceptive22 and, in turn, improve the health of women and their families.

Again: We urge the FDA to promptly remove the black-box warning from labeling for DMPA.

Do you agree? We want to hear your opinion: Write to us in care of The Editors, at [email protected]!

Long-acting reversible contraceptives are safe, effective for most women, study shows

But most use other methods because of lack of knowledge and cost concerns

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) are safe and effective for almost all women of reproductive age, according to an ACOG practice bulletin published in the July issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Eve Espey, MD, MPH, and Rameet H. Singh, MD, MPH, from ACOG in Washington, DC, and colleagues compiled the latest recommendations on LARC use. The recommendations identify candidates for LARCs and help obstetricians and gynecologists manage LARC-related clinical issues.

The investigators reported that the LARC methods currently available have few contraindications, and that most women are eligible to use them. Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are suitable for women with a previous ectopic pregnancy and for women immediately after abortion or miscarriage. Routine antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended before IUD insertion.

Copper IUD inserted up to 5 days after unprotected intercourse is the most effective method of postcoital contraception. The copper IUD can be used and remains effective for up to 10 continuous years. The levonorgestrel IUD may be effective for up to 7 years.

IUD complications are rare and include expulsion, method failure, and perforation. Implants can be safely inserted at any time after childbirth in non-breastfeeding women, or after 4 weeks for breastfeeding mothers. All LARC methods are safe for nulliparous women and adolescents.

The use of IUDs increased from 1.3% to 5.5% from 2002 to 2006-2008. Despite the benefits of LARCs, the majority of women choose other birth control methods, probably due to lack of knowledge about LARCs and cost concerns.

“LARC methods are the best tool we have to fight against unintended pregnancies, which currently account for 49% of US pregnancies each year,” Espey said in a statement.

Copyright © 2011 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

Has the FDA’s warning about DMPA had a chilling effect? Does the black-box warning prevent you from prescribing DMPA? Or does it alter your approach to using it? How?

To tell us, click here

1. Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. Change in bone mineral density among adolescent women using and discontinuing depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception. Arch Pediatric Adolesc Med. 2005;159(2):139-144.

2. Harel Z, Johnson CC, Gold MA, et al. Recovery of bone mineral density in adolescents following the use of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraceptive injections. Contraception. 2010;81(4):281-291.

3. Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. Injectable hormone contraception and bone density: Results from a prospective study. Epidemiology. 2002;13(5):581-7.

4. Kaunitz AM, Miller PD, Rice VM, Ross D, McClung MR. Bone mineral density in women aged 25-35 years receiving depot medroxyprogesterone acetate: recovery following discontinuation. Contraception. 2006;74(2):90-99.

5. Schnatz PF, Barker KG, Marakovits KA, O’Sullivan DM. Effects of age at first pregnancy and breast-feeding on the development of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Menopause. 2010;17(6):1161-1166.

6. World Health Organization WHO Epidemiological Record No. 35: WHO statement on hormonal contraception and bone health. Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2005;80(35):302-304.

7. Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Surrogate end points in clinical research: hazardous to your health. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 pt 1):1114-1118.

8. Grimes DA, Schulz KF, Raymond EG. Surrogate end points in women’s health research: science protoscience, and pseudoscience. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(6):1731-1734.

9. Shulman LP, Bateman LH, Creinin MD, et al. Surrogate markers, emboldened and boxed warnings, and an expanding culture of misinformation: evidence-based clinical science should guide FDA decision making about product labeling. Contraception. 2006;73(5):440-442.

10. Cundy T, Cornish J, Roberts H, Reid IR. Menopausal bone loss in long-term users of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5):978-983.

11. Orr-Walker BJ, Evans MC, Ames RW, Clearwater JM, Cundy T, Reid IR. The effect of past use of the injectable contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate on bone mineral density in normal post-menopausal women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1998;49(5):615-618.

12. Viola AS, Castro S, Marchi NM, Bahamondes MV, Viola CFM, Bahamondes L. Long-term assessment of forearm bone mineral density in postmenopausal former users of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate. Contraception. In press.

13. Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. The effects of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and intrauterine device use on fracture risk in Danish women. Contraception. 2008;78(6):459-464.

14. Meier C, Brauchli YB, Jick SS, Kraenzlin ME, Meier CR. Use of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and fracture risk. J Clin Endocrin Metab. 2010;95(11):4909-4916.

15. Kaunitz AM, Harel Z, Bone H, et al. Retrospective cohort study of DMPA and fractures in reproductive age women. Paper presented at: Association of Reproductive Health Professional Annual Meeting; September 24, 2010; Atlanta, GA.

16. Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982-2008. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 23. 2010;23(29):1-44.

17. Paschall S, Kaunitz AM. Depo-Provera and skeletal health: A survey of Florida obstetrics and gynecologist physicians. Contraception. 2008;78(5):370-376.

18. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 415: Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and bone effects. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(3):727-730.

19. Cromer BA, Scholes D, Berenson A, Cundy T, Clark MK, Kaunitz AM; Society for Adolescent Medicine. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and bone mineral density in adolescent—the black box warning: A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(2):296-301.

20. Black A; Ad Hoc DMPA Committee of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Canadian contraception consensus: update on depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28(4):305-313.

21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria contraceptive use 2010. MMWR. 2010;59 (RR04);1:6.

22. Kaunitz AM, Grimes DA. Removing the black box warning for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate [published online ahead of print February 21 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.009.

- Update on contraception

Rachel B. Rapkin, MD; Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (August 2011) - 10 (+1) practical, evidence-based recommendations for you to improve contraceptive care now

Colleen Krajewski, MD; Mark D. Walters, MD (August 2011) - Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other?

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; March 2011) - IUD use in nulliparous and adolescent women

Jennefer A. Russo, MD; Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (Update on Contraception, August 2010)

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should remove the black-box warning regarding skeletal health that the agency inserted into labeling for the injectable contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA; Depo-Provera) in 2004. The black box 1) indicates that use of DMPA for longer than 2 years may reduce peak bone mass and place a woman at increased risk of osteoporotic fracture and 2) suggests that ObGyns order bone-density assessment in women who use DMPA long-term.

This warning is not based on scientific evidence. By depriving women of long-term use of a safe, effective contraceptive, the black-box warning damages women’s health and the public health.

The scientific argument for removing the black box

Although DMPA does cause reduced ovarian estradiol production, with a decline in bone mineral density (BMD), complete recovery of BMD occurs approximately 1 or 2 years after discontinuation in adolescent girls1,2 and 3 years after discontinuation in adult women.3,4 BMD trends observed with the use of DMPA parallel those associated with another normal but hypoestrogenic state: breastfeeding. Although BMD declines noted in nursing mothers are similar to those associated with DMPA, breastfeeding one or more infants has not been reported to increase the risk of subsequent osteoporotic fractures.5 The FDA does not warn women against breastfeeding for fear of a theoretical negative impact on skeletal health.

BMD can help predict a risk of osteoporotic fracture in menopausal women, but it is not a valid surrogate endpoint for fracture in women of reproductive age.6 Basing clinical recommendations on invalid surrogate endpoints can cause harm.7-9 Clinical recommendations, including those from the FDA, should be based on sound studies that address important clinical outcomes.

No convincing evidence links the use of DMPA for contraception to fracture. Studies of menopausal women have not suggested that prior use of DMPA increased their risk of osteoporosis.10-12 Two recently published case-control studies, one using a Danish National Patient Registry13 and one based on the United Kingdom Family Practice Research database,14 have demonstrated that DMPA is associated with an elevated risk of fracture in reproductive-age women. However, a cohort analysis using the same British Family Practice database clarifies that the elevated fracture risk observed in women using DMPA occurred before initiation of injectable contraception and was not the result of DMPA use.15

A clearly harmful effect on women’s health

The black-box warning for DMPA has caused clinicians and women to reduce use of this effective method of contraception. The 2008 National Survey of Family Growth shows that the overall percentage of US women, 15 to 44 years of age, who now use DMPA has declined—from 3.3% in 2002 to 2.0% in 2006 to 2008.16

In fact, a survey of ObGyns in Florida found that 1) almost one half of respondents place a time limit on duration of DMPA and 2) two thirds of those respondents base that restriction on the black-box warning.17 Restricting the use of DMPA can lead to more unintended pregnancies and induced abortions.

In the Florida survey, two thirds of respondents order BMD assessment in women who use DMPA, with 58% of those physicians who do so attributing their decision to, again, the black-box warning. Indeed, more than 5% of respondents reported that they selectively prescribe bisphosphonates to women of reproductive age who use DMPA—an expensive practice that is not evidence-based and is potentially dangerous.

FDA guidance is far out of step

The black-box warning for DMPA is not in accord with the guidance provided major medical and public health organizations. The World Health Organization,6 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,18 the Society for Adolescent Medicine,19 and the Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Canada,20 have all stated that skeletal health concerns shouldn’t restrict the use of DMPA, including the duration of use.

In the US Medical Eligibility Criteria for contraceptive use, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared that use of DMPA is Category 1 (no restriction on use) in women 18 to 45 years of age and Category 2 (advantages of the method generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks) in younger women.21 The FDA’s black-box warning is therefore inconsistent with the recommendation of its sister agency.

An opportunity to improve the health of women

The FDA appropriately takes action when a pharmaceutical company mislabels a product or promotes it in a way that isn’t based on sound evidence. Shouldn’t the FDA apply the same scientific standards to itself? Guidance included in DMPA’s black box is not evidence-based—and that reduces use of DMPA in US women and increases the potential for harm. Removing the black box would encourage use of this convenient, effective, and safe contraceptive22 and, in turn, improve the health of women and their families.

Again: We urge the FDA to promptly remove the black-box warning from labeling for DMPA.

Do you agree? We want to hear your opinion: Write to us in care of The Editors, at [email protected]!

Long-acting reversible contraceptives are safe, effective for most women, study shows

But most use other methods because of lack of knowledge and cost concerns

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) are safe and effective for almost all women of reproductive age, according to an ACOG practice bulletin published in the July issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Eve Espey, MD, MPH, and Rameet H. Singh, MD, MPH, from ACOG in Washington, DC, and colleagues compiled the latest recommendations on LARC use. The recommendations identify candidates for LARCs and help obstetricians and gynecologists manage LARC-related clinical issues.

The investigators reported that the LARC methods currently available have few contraindications, and that most women are eligible to use them. Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are suitable for women with a previous ectopic pregnancy and for women immediately after abortion or miscarriage. Routine antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended before IUD insertion.

Copper IUD inserted up to 5 days after unprotected intercourse is the most effective method of postcoital contraception. The copper IUD can be used and remains effective for up to 10 continuous years. The levonorgestrel IUD may be effective for up to 7 years.

IUD complications are rare and include expulsion, method failure, and perforation. Implants can be safely inserted at any time after childbirth in non-breastfeeding women, or after 4 weeks for breastfeeding mothers. All LARC methods are safe for nulliparous women and adolescents.

The use of IUDs increased from 1.3% to 5.5% from 2002 to 2006-2008. Despite the benefits of LARCs, the majority of women choose other birth control methods, probably due to lack of knowledge about LARCs and cost concerns.

“LARC methods are the best tool we have to fight against unintended pregnancies, which currently account for 49% of US pregnancies each year,” Espey said in a statement.

Copyright © 2011 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

Has the FDA’s warning about DMPA had a chilling effect? Does the black-box warning prevent you from prescribing DMPA? Or does it alter your approach to using it? How?

To tell us, click here

- Update on contraception

Rachel B. Rapkin, MD; Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (August 2011) - 10 (+1) practical, evidence-based recommendations for you to improve contraceptive care now

Colleen Krajewski, MD; Mark D. Walters, MD (August 2011) - Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other?

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; March 2011) - IUD use in nulliparous and adolescent women

Jennefer A. Russo, MD; Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (Update on Contraception, August 2010)

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should remove the black-box warning regarding skeletal health that the agency inserted into labeling for the injectable contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA; Depo-Provera) in 2004. The black box 1) indicates that use of DMPA for longer than 2 years may reduce peak bone mass and place a woman at increased risk of osteoporotic fracture and 2) suggests that ObGyns order bone-density assessment in women who use DMPA long-term.

This warning is not based on scientific evidence. By depriving women of long-term use of a safe, effective contraceptive, the black-box warning damages women’s health and the public health.

The scientific argument for removing the black box

Although DMPA does cause reduced ovarian estradiol production, with a decline in bone mineral density (BMD), complete recovery of BMD occurs approximately 1 or 2 years after discontinuation in adolescent girls1,2 and 3 years after discontinuation in adult women.3,4 BMD trends observed with the use of DMPA parallel those associated with another normal but hypoestrogenic state: breastfeeding. Although BMD declines noted in nursing mothers are similar to those associated with DMPA, breastfeeding one or more infants has not been reported to increase the risk of subsequent osteoporotic fractures.5 The FDA does not warn women against breastfeeding for fear of a theoretical negative impact on skeletal health.

BMD can help predict a risk of osteoporotic fracture in menopausal women, but it is not a valid surrogate endpoint for fracture in women of reproductive age.6 Basing clinical recommendations on invalid surrogate endpoints can cause harm.7-9 Clinical recommendations, including those from the FDA, should be based on sound studies that address important clinical outcomes.

No convincing evidence links the use of DMPA for contraception to fracture. Studies of menopausal women have not suggested that prior use of DMPA increased their risk of osteoporosis.10-12 Two recently published case-control studies, one using a Danish National Patient Registry13 and one based on the United Kingdom Family Practice Research database,14 have demonstrated that DMPA is associated with an elevated risk of fracture in reproductive-age women. However, a cohort analysis using the same British Family Practice database clarifies that the elevated fracture risk observed in women using DMPA occurred before initiation of injectable contraception and was not the result of DMPA use.15

A clearly harmful effect on women’s health

The black-box warning for DMPA has caused clinicians and women to reduce use of this effective method of contraception. The 2008 National Survey of Family Growth shows that the overall percentage of US women, 15 to 44 years of age, who now use DMPA has declined—from 3.3% in 2002 to 2.0% in 2006 to 2008.16

In fact, a survey of ObGyns in Florida found that 1) almost one half of respondents place a time limit on duration of DMPA and 2) two thirds of those respondents base that restriction on the black-box warning.17 Restricting the use of DMPA can lead to more unintended pregnancies and induced abortions.

In the Florida survey, two thirds of respondents order BMD assessment in women who use DMPA, with 58% of those physicians who do so attributing their decision to, again, the black-box warning. Indeed, more than 5% of respondents reported that they selectively prescribe bisphosphonates to women of reproductive age who use DMPA—an expensive practice that is not evidence-based and is potentially dangerous.

FDA guidance is far out of step

The black-box warning for DMPA is not in accord with the guidance provided major medical and public health organizations. The World Health Organization,6 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,18 the Society for Adolescent Medicine,19 and the Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Canada,20 have all stated that skeletal health concerns shouldn’t restrict the use of DMPA, including the duration of use.

In the US Medical Eligibility Criteria for contraceptive use, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared that use of DMPA is Category 1 (no restriction on use) in women 18 to 45 years of age and Category 2 (advantages of the method generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks) in younger women.21 The FDA’s black-box warning is therefore inconsistent with the recommendation of its sister agency.

An opportunity to improve the health of women

The FDA appropriately takes action when a pharmaceutical company mislabels a product or promotes it in a way that isn’t based on sound evidence. Shouldn’t the FDA apply the same scientific standards to itself? Guidance included in DMPA’s black box is not evidence-based—and that reduces use of DMPA in US women and increases the potential for harm. Removing the black box would encourage use of this convenient, effective, and safe contraceptive22 and, in turn, improve the health of women and their families.

Again: We urge the FDA to promptly remove the black-box warning from labeling for DMPA.

Do you agree? We want to hear your opinion: Write to us in care of The Editors, at [email protected]!

Long-acting reversible contraceptives are safe, effective for most women, study shows

But most use other methods because of lack of knowledge and cost concerns

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) are safe and effective for almost all women of reproductive age, according to an ACOG practice bulletin published in the July issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Eve Espey, MD, MPH, and Rameet H. Singh, MD, MPH, from ACOG in Washington, DC, and colleagues compiled the latest recommendations on LARC use. The recommendations identify candidates for LARCs and help obstetricians and gynecologists manage LARC-related clinical issues.

The investigators reported that the LARC methods currently available have few contraindications, and that most women are eligible to use them. Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are suitable for women with a previous ectopic pregnancy and for women immediately after abortion or miscarriage. Routine antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended before IUD insertion.

Copper IUD inserted up to 5 days after unprotected intercourse is the most effective method of postcoital contraception. The copper IUD can be used and remains effective for up to 10 continuous years. The levonorgestrel IUD may be effective for up to 7 years.

IUD complications are rare and include expulsion, method failure, and perforation. Implants can be safely inserted at any time after childbirth in non-breastfeeding women, or after 4 weeks for breastfeeding mothers. All LARC methods are safe for nulliparous women and adolescents.

The use of IUDs increased from 1.3% to 5.5% from 2002 to 2006-2008. Despite the benefits of LARCs, the majority of women choose other birth control methods, probably due to lack of knowledge about LARCs and cost concerns.

“LARC methods are the best tool we have to fight against unintended pregnancies, which currently account for 49% of US pregnancies each year,” Espey said in a statement.

Copyright © 2011 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

Has the FDA’s warning about DMPA had a chilling effect? Does the black-box warning prevent you from prescribing DMPA? Or does it alter your approach to using it? How?

To tell us, click here

1. Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. Change in bone mineral density among adolescent women using and discontinuing depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception. Arch Pediatric Adolesc Med. 2005;159(2):139-144.

2. Harel Z, Johnson CC, Gold MA, et al. Recovery of bone mineral density in adolescents following the use of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraceptive injections. Contraception. 2010;81(4):281-291.

3. Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. Injectable hormone contraception and bone density: Results from a prospective study. Epidemiology. 2002;13(5):581-7.

4. Kaunitz AM, Miller PD, Rice VM, Ross D, McClung MR. Bone mineral density in women aged 25-35 years receiving depot medroxyprogesterone acetate: recovery following discontinuation. Contraception. 2006;74(2):90-99.

5. Schnatz PF, Barker KG, Marakovits KA, O’Sullivan DM. Effects of age at first pregnancy and breast-feeding on the development of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Menopause. 2010;17(6):1161-1166.

6. World Health Organization WHO Epidemiological Record No. 35: WHO statement on hormonal contraception and bone health. Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2005;80(35):302-304.

7. Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Surrogate end points in clinical research: hazardous to your health. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 pt 1):1114-1118.

8. Grimes DA, Schulz KF, Raymond EG. Surrogate end points in women’s health research: science protoscience, and pseudoscience. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(6):1731-1734.

9. Shulman LP, Bateman LH, Creinin MD, et al. Surrogate markers, emboldened and boxed warnings, and an expanding culture of misinformation: evidence-based clinical science should guide FDA decision making about product labeling. Contraception. 2006;73(5):440-442.

10. Cundy T, Cornish J, Roberts H, Reid IR. Menopausal bone loss in long-term users of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5):978-983.

11. Orr-Walker BJ, Evans MC, Ames RW, Clearwater JM, Cundy T, Reid IR. The effect of past use of the injectable contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate on bone mineral density in normal post-menopausal women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1998;49(5):615-618.

12. Viola AS, Castro S, Marchi NM, Bahamondes MV, Viola CFM, Bahamondes L. Long-term assessment of forearm bone mineral density in postmenopausal former users of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate. Contraception. In press.

13. Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. The effects of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and intrauterine device use on fracture risk in Danish women. Contraception. 2008;78(6):459-464.

14. Meier C, Brauchli YB, Jick SS, Kraenzlin ME, Meier CR. Use of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and fracture risk. J Clin Endocrin Metab. 2010;95(11):4909-4916.

15. Kaunitz AM, Harel Z, Bone H, et al. Retrospective cohort study of DMPA and fractures in reproductive age women. Paper presented at: Association of Reproductive Health Professional Annual Meeting; September 24, 2010; Atlanta, GA.

16. Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982-2008. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 23. 2010;23(29):1-44.

17. Paschall S, Kaunitz AM. Depo-Provera and skeletal health: A survey of Florida obstetrics and gynecologist physicians. Contraception. 2008;78(5):370-376.

18. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 415: Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and bone effects. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(3):727-730.

19. Cromer BA, Scholes D, Berenson A, Cundy T, Clark MK, Kaunitz AM; Society for Adolescent Medicine. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and bone mineral density in adolescent—the black box warning: A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(2):296-301.

20. Black A; Ad Hoc DMPA Committee of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Canadian contraception consensus: update on depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28(4):305-313.

21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria contraceptive use 2010. MMWR. 2010;59 (RR04);1:6.

22. Kaunitz AM, Grimes DA. Removing the black box warning for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate [published online ahead of print February 21 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.009.

1. Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. Change in bone mineral density among adolescent women using and discontinuing depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception. Arch Pediatric Adolesc Med. 2005;159(2):139-144.

2. Harel Z, Johnson CC, Gold MA, et al. Recovery of bone mineral density in adolescents following the use of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraceptive injections. Contraception. 2010;81(4):281-291.

3. Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. Injectable hormone contraception and bone density: Results from a prospective study. Epidemiology. 2002;13(5):581-7.

4. Kaunitz AM, Miller PD, Rice VM, Ross D, McClung MR. Bone mineral density in women aged 25-35 years receiving depot medroxyprogesterone acetate: recovery following discontinuation. Contraception. 2006;74(2):90-99.

5. Schnatz PF, Barker KG, Marakovits KA, O’Sullivan DM. Effects of age at first pregnancy and breast-feeding on the development of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Menopause. 2010;17(6):1161-1166.

6. World Health Organization WHO Epidemiological Record No. 35: WHO statement on hormonal contraception and bone health. Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2005;80(35):302-304.

7. Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Surrogate end points in clinical research: hazardous to your health. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 pt 1):1114-1118.

8. Grimes DA, Schulz KF, Raymond EG. Surrogate end points in women’s health research: science protoscience, and pseudoscience. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(6):1731-1734.

9. Shulman LP, Bateman LH, Creinin MD, et al. Surrogate markers, emboldened and boxed warnings, and an expanding culture of misinformation: evidence-based clinical science should guide FDA decision making about product labeling. Contraception. 2006;73(5):440-442.

10. Cundy T, Cornish J, Roberts H, Reid IR. Menopausal bone loss in long-term users of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5):978-983.

11. Orr-Walker BJ, Evans MC, Ames RW, Clearwater JM, Cundy T, Reid IR. The effect of past use of the injectable contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate on bone mineral density in normal post-menopausal women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1998;49(5):615-618.

12. Viola AS, Castro S, Marchi NM, Bahamondes MV, Viola CFM, Bahamondes L. Long-term assessment of forearm bone mineral density in postmenopausal former users of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate. Contraception. In press.

13. Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. The effects of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and intrauterine device use on fracture risk in Danish women. Contraception. 2008;78(6):459-464.

14. Meier C, Brauchli YB, Jick SS, Kraenzlin ME, Meier CR. Use of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and fracture risk. J Clin Endocrin Metab. 2010;95(11):4909-4916.

15. Kaunitz AM, Harel Z, Bone H, et al. Retrospective cohort study of DMPA and fractures in reproductive age women. Paper presented at: Association of Reproductive Health Professional Annual Meeting; September 24, 2010; Atlanta, GA.

16. Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982-2008. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 23. 2010;23(29):1-44.

17. Paschall S, Kaunitz AM. Depo-Provera and skeletal health: A survey of Florida obstetrics and gynecologist physicians. Contraception. 2008;78(5):370-376.

18. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 415: Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and bone effects. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(3):727-730.

19. Cromer BA, Scholes D, Berenson A, Cundy T, Clark MK, Kaunitz AM; Society for Adolescent Medicine. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and bone mineral density in adolescent—the black box warning: A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(2):296-301.

20. Black A; Ad Hoc DMPA Committee of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Canadian contraception consensus: update on depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28(4):305-313.

21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria contraceptive use 2010. MMWR. 2010;59 (RR04);1:6.

22. Kaunitz AM, Grimes DA. Removing the black box warning for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate [published online ahead of print February 21 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.009.

IN THIS ARTICLE

UPDATE ON MENOPAUSE

- Is hormone therapy still a valid option? 12 ObGyns address this question

Members of the OBG MANAGEMENT Virtual Board of Editors and Janelle Yates, Senior Editor (May 2011)

Dr. Kaunitz receives grant or research support from Bayer, Agile, Noven, Teva, and Medical Diagnostic Laboratories, is a consultant to Bayer, Merck, and Teva, and owns stock in Becton Dickinson.

Among the developments of the past year in the care of menopausal women are:

- updated guidelines from the Institute of Medicine regarding vitamin D requirements—suggesting that fewer women are deficient in this nutrient than experts had believed

- new data from Europe on hormone therapy (HT) that highlight the safety of transdermal estrogen in comparison with oral administration

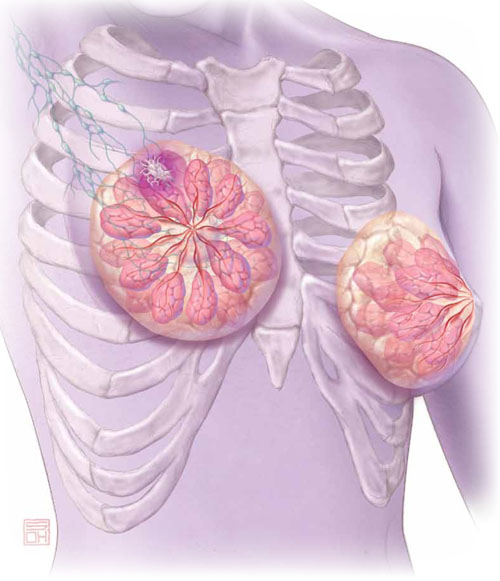

- a recent analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), confirming a small elevated risk of breast cancer mortality with use of combination estrogen-progestin HT

- confirmation that age at initiation of HT determines its effect on cardiovascular health

- clarification of the association between HT and dementia

- new data demonstrating modest improvement in hot flushes when the serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) escitalopram is used

- a brand new report from the WHI estrogen-alone arm that shows a protective effect against breast cancer.

The new data on HT suggest that we still have much to learn about its benefits and risks. We also are reaching an understanding that, for many young, symptomatic, menopausal patients, HT can represent a safe choice, with much depending on the timing and duration of therapy.

For more on how your colleagues are managing menopausal patients with and without hormone therapy, see “Is hormone therapy still a valid option? 12 ObGyns address this question,” on the facing page.

Menopausal women need less vitamin D than we thought

Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: IOM; December 2010. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2010/Dietary-Reference-Intakes-for-Calcium-and-Vitamin-D/Vitamin%20D%20and%20Calcium%202010%20Report%20Brief.pdf. Accessed March 24, 2011.

In the 2010 Update on Menopause, I summarized recent findings on vitamin D requirements, including recommendations that menopausal women should take at least 800 IU of vitamin D daily. I also described the prevailing expert opinion that many North American women are deficient in this nutrient.

What a difference a year can make! In late November, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a comprehensive report on vitamin D. Here are some of its conclusions:

- Vitamin D plays an important role in skeletal health but its role in other areas, including cardiovascular disease and cancer, is uncertain

- An intake of 600 IU of vitamin D daily is appropriate for girls and for women as old as 70 years; an in-take of 800 IU daily is appropriate for women older than 70 years

- A serum level of 25-hydroxy vitamin D of 20 ng/mL is consistent with adequate vitamin D status; this is lower than the threshold many have recommended

- With few exceptions, all people who live in North America—including those who have minimal or no exposure to sunlight—are receiving adequate calcium and vitamin D

- Ingestion of more than 4,000 IU of vitamin D daily can cause renal damage and injure other tissues.

The IOM report will likely prompt multivitamin manufacturers to increase the amount of vitamin D contained in their supplements to 600 IU daily. In addition, the report will probably discourage the common practice of checking serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels and prescribing a high dosage of vitamin D supplementation when the level is below 30 ng/mL.

I continue to recommend multivitamin supplements that include calcium and vitamin D (but no iron) to my menopausal patients. However, I no longer routinely recommend that they take additional calcium and vitamin D or undergo assessment of serum vitamin D levels.

Is transdermal estrogen safer than oral administration?

Canonico M, Fournier A, Carcaillon L, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of idiopathic venous thromboembolism: results from the E3N cohort study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(2):340–345.

Renoux C, Dell’aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: a nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2519.

In the WHI, the combination of oral conjugated equine estrogen and medroxyprogesterone acetate more than doubled the risk of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism and modestly increased the risk of stroke, compared with nonuse.1

A year after publication of the initial findings of the WHI estrogen-progestin arm, the Estrogen and THromboEmbolism Risk Study Group (ESTHER) case-control study from France provided evidence that transdermal estrogen does not increase the risk of venous thrombosis.2 In France, many menopausal women use HT, and the transdermal route of administration is common.

In 2010, the E3N cohort study from France also assessed the risk of thrombosis associated with oral and transdermal HT. Investigators followed more than 80,000 postmenopausal women and found that, unlike oral HT, the transdermal route did not increase the risk of venous thrombosis.

More recent evidence also suggests a safety advantage for transdermal HT. The newest data come from the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database, which includes information on more than 870,000 women who were 50 to 70 years old from 1987 to 2006. Investigators identified more than 15,000 women who were given a diagnosis of stroke during this period and compared the use of HT in these women with that of almost 60,000 women in a control group. The risk of stroke associated with current use of transdermal HT was similar to the risk associated with nonuse of HT. Women who used a patch containing 0.05 mg of estradiol or less had a risk of stroke 19% lower than women who did not use HT.

In contrast, the risk of stroke in users of patches that contained a higher dosage of estradiol was almost twice the risk in nonusers of HT. Current users of oral HT had a risk of stroke 28% higher than that of nonusers of HT.

The WHI assessed the risks and benefits of oral HT only. Although no randomized, clinical trial has compared cardiovascular risks among users of oral and transdermal HT, I believe that a preponderance of evidence points to a superior safety profile for the transdermal route, particularly at a dosage of 0.05 mg of estradiol or less.

I encourage my patients who are initiating HT to consider the transdermal route—particularly women who have an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease, including those who are overweight, smoke cigarettes, or who have hypertension or diabetes. I suggest the transdermal route despite its higher cost (oral micronized estradiol can be purchased for as little as $4 for a month’s supply at a chain pharmacy).

When a patient prefers to avoid a patch (because of local irritation), I offer her estradiol gel or spray or the vaginal ring. (Femring is systemic estradiol, whereas Estring is local.) These formulations should provide the same safety benefits as the patch.

Estrogen-progestin HT raises the risk of death from breast cancer

Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Gass M, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2010;304(15):1684–1692.

Toh S, Hernandez-Diaz S, Logan R, Rossouw JE, Hernan MA. Coronary heart disease in postmenopausal recipients of estrogen plus progestin: does the increased risk ever disappear? Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(4):211–217.

In the estrogen-progestin arm of the WHI, initially published in 2002, the risk of invasive breast cancer was modestly elevated (hazard ratio [HR], 1.26) among women who had used HT longer than 5 years.3

In 2010, investigators reported on breast cancer mortality in WHI participants at a mean follow-up of 11 years. They found that combination HT users had breast cancer histology similar to that of nonusers. However, the tumors were more likely to be node-positive in combination HT users (23.7% vs 16.2%). In addition, breast cancer mortality was slightly higher among users of HT (2.6 vs 1.3 deaths in every 10,000 woman-years) (HR, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.00–4.04).

Earlier observational studies had suggested that the death rate from breast cancer is lower in users of combination HT than in nonusers. Consistent with the UK Million Women Study, however, a 2010 report from the WHI found a higher mortality rate among women who have used HT.4

These new WHI findings reinforce the importance of assessing whether micronized progesterone combined with estrogen might lower the risk of death from breast cancer—a possibility suggested by findings of the French E3N cohort study.5

In addition, given the possibility that HT may be cardioprotective when it is initiated within 10 years after the onset of menopause, a WHI report that addresses long-term all-cause mortality would allow us to better counsel our menopausal patients who are trying to decide whether to start or continue HT. See, for example, the data from the California Teachers Study (below) and the estrogen-alone arm of the WHI (page 46).

The findings of this important WHI publication have strengthened the resolve of some clinicians to stop prescribing HT for menopausal women. I continue to prescribe HT to patients who have bothersome vasomotor and related symptoms, however. I also counsel women about the other benefits of HT, which include alleviation of genital atrophy and prevention of osteoporotic fractures. For patients considering or using estrogen-progestin HT, I include discussion of the small increase in their risk of developing, and dying from, breast cancer.

Age at initiation of HT determines its effect on CHD

Stram DO, Liu Y, Henderson KD, et al. Age-specific effects of hormone therapy use on overall mortality and ischemic heart disease mortality among women in the California Teachers Study. Menopause 2011;18(3):253-261.

Allison MA, Manson JE. Age, hormone therapy use, coronary heart disease, and mortality [editorial]. Menopause. 2011;18(3):243-245.

The initial findings of the WHI estrogen-progestin arm suggested that menopausal HT increases the risk of CHD. Since then, however, further analyses from the WHI and other HT trials, as well as reports from the observational Nurses’ Health Study, have suggested that the timing of initiation of HT determines its effect on cardiovascular health.

In this study from the California Teachers Study (CTS), investigators explored the effect of age at initiation of HT on cardiovascular and overall mortality. The CTS is a prospective study of more than 133,000 current and retired female teachers and administrators who returned an initial questionnaire in 1995 and 1996. Participants were then followed until late 2004, or death, whichever came first. More than 71,000 participants were eligible for analysis.

Current HT users were leaner, less likely to smoke, and more likely to exercise and consume alcohol than nonusers were. The analysis was adjusted for a variety of potential cardiovascular and other confounders.

Youngest HT users had the lowest risk of death

During follow-up, 18.3% of never-users of HT died, compared with 17.9% of former users. In contrast, 6.9% of women taking HT at the time of the baseline questionnaire died during follow-up.

Overall, current HT use was associated with a reduced risk of death from CHD (hazard ratio [HR], 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.74–0.95). This risk reduction was most notable (HR, 0.38) in the youngest HT users (36 to 59 years old). The risk of death from CHD gradually increased with the age of current HT users, reaching a hazard ratio of approximately 0.9 in current users who were 70 years and older. However, the CHD mortality hazard ratio did not reach or exceed the referent hazard ratio (1.0) assigned to never users of HT of any age.

The overall mortality rate was lowest for the youngest HT users (HR, 0.54) and approached 1.0 in the oldest current HT users.

The associations between overall and CHD mortality were similar among users of estrogen-only and estrogen-progestin HT.

As Allison and Manson point out in an editorial accompanying this study, the findings from the CTS are congruent with an extensive body of evidence from women and nonhuman primates. These data provide robust reassurance that HT does not increase the risk of death from CHD when it is used by recently menopausal women who have bothersome vasomotor symptoms.

Hormone therapy and dementia: Earlier use is better

Whitmer RA, Quesenberry CP, Zhou J, Yaffe K. Timing of hormone therapy and dementia: the critical window theory revisited. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(1):163–169.

Alzheimer’s disease is more common among women than men. In addition, caregivers to those who have dementia are more likely to be women. Therefore, it’s no surprise that women are especially concerned about their risk of dementia. Menopausal patients in my practice often ask whether use of HT might alter this risk.

Because vasomotor symptoms usually arise in late perimenopause or early menopause, women in observational studies (which reflect clinical practice) tend to begin HT when they are in their late 40s or early 50s. Overall, observational studies have suggested that HT is associated with a reduced risk of dementia. In contrast, the WHI clinical trial, in which the mean age of women who were randomized to HT or placebo was 63 years, found that the initiation of HT later in life increased the risk of dementia.

These observations led to the “critical window” theory regarding HT and dementia: Estrogen protects against dementia when it is taken by perimenopausal or early menopausal women, whereas it is not protective and may even accelerate cognitive decline when it is started many years after the onset of menopause.

In this recent study from the California Kaiser Permanente health maintenance organization, investigators assessed the long-term risk of dementia by timing of HT. From 1964 through 1973, menopausal “midlife” women who were 40 to 55 years old and free of dementia reported whether or not they used HT. Twenty-five to 30 years later, participants were reassessed for “late life” HT use.

Women who used HT in midlife only had the lowest prevalence of dementia, whereas those who used HT only in late life had the highest prevalence. Women who used HT at both time points had a prevalence of dementia similar to that of women who had never used HT.

Given these important findings, I believe it is now reasonable to counsel women in late perimenopause and early menopause that the use of HT may lower their risk of dementia. How long we should continue to prescribe HT depends on individual variables, including the presence of vasomotor symptoms, the risk of osteoporosis, and concerns about breast cancer.

I encourage women to taper their dosage of HT over time, aiming at complete discontinuation or a low maintenance dosage.

Are SRIs an effective alternative to HT for hot flushes?

Freeman EW, Guthrie K, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in healthy menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(3):267–274.

Interest in nonhormonal management of menopausal vasomotor symptoms continues to run high, although only hormonal therapy has FDA approval for this indication. Many trials of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms have focused on breast cancer survivors, many of whom use anti-estrogen agents that increase the prevalence of these symptoms. In contrast, this well-conducted multicenter trial, funded by the National Institutes of Health, enrolled healthy, symptomatic, menopausal women.

In the trial, 205 perimenopausal or postmenopausal women 40 to 62 years old who had at least 28 bothersome or severe episodes of hot flushes and night sweats a week were randomized to 10 mg daily of the SRI escitalopram (Lexapro) or placebo for 8 weeks. Women who did not report a reduction in hot flushes and night sweats of at least 50% at 4 weeks, or a decrease in the severity of these symptoms, were increased to a dosage of 20 mg daily of escitalopram or placebo. The mean baseline frequency of vasomotor symptoms was 9.79.

Within 1 week, women taking the SRI experienced significantly greater improvement than those taking placebo. By 8 weeks, the daily frequency of vasomotor symptoms had diminished by 4.6 hot flushes among women taking the SRI, compared with 3.20 among women taking placebo (P < .01).

Overall, adverse effects were reported by approximately 58% of participants. The pattern of these side effects was similar in the active and placebo treatment arms. No adverse events serious enough to require withdrawal from the study were reported in either arm.

Patient satisfaction with treatment was 70% in the SRI group, compared with 43% among women taking placebo (P < .001).

Although Freeman and colleagues convincingly demonstrate that escitalopram is more effective than placebo, the drug is less effective than HT. I agree with Nelson and coworkers, who, in a meta-analysis of nonhormonal treatments for vasomotor symptoms, concluded: “These therapies may be most useful for highly symptomatic women who cannot take estrogen but are not optimal choices for most women.”6

Unopposed estrogen appears to protect against breast cancer

LaCroix AZ, Chlebowski RT, Manson JE, et al; WHI Investigators. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1305–1314.

The WHI continues to surprise with its findings almost a decade after publication of initial data. In this brand new report from the estrogen-alone arm, postmenopausal, hysterectomized women who were followed for a mean of 10.7 years experienced a reduced risk of breast cancer after a mean of 5.9 years of use of conjugated equine estrogens (CEE).

They experienced no increased or diminished risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), deep venous thrombosis, stroke, hip fracture, colorectal cancer, or total mortality after post-intervention follow-up.

Keep in mind that the women in this arm were instructed to discontinue the study medication at the time the intervention phase was halted because of an increased risk of stroke among CEE users. The elevated risk of stroke attenuated with the longer follow-up.

All ages experienced a reduced risk of breast cancer

Some subgroup analyses from the WHI have found differential effects of HT by age of the user, with younger women experiencing fewer risks and more benefits than those who are more than 10 years past the menopausal transition. In this analysis, all three age groups (50–59 years, 60–69 years, and 70–79 years) of women who used CEE had a reduced risk of breast cancer, compared with placebo users.

Other risks did appear to differ by age. For example, the overall hazard ratio for CHD was 0.59 among CEE users 50 to 59 years old, but it approached unity among the older women.

As new and seemingly conflicting data are published, many clinicians and their menopausal patients may feel confused and frustrated. My perspective: It is becoming clear that age during HT use matters with respect to CHD and dementia, and that estrogen-only HT has a different impact on breast cancer risk than does combination estrogen-progestin HT. When this new information from the WHI is considered in aggregate with earlier WHI reports, as well as with data from the Nurses Health Study, the California Teachers Study, and Kaiser Permanente, we can, with growing confidence, advise our patients that menopausal HT does not increase the risk of fatal CHD and may reduce the risk of dementia when used by younger menopausal women with bothersome symptoms. I would define “younger” here as an age younger than 60 years or within 10 years of the onset of menopause.

In regard to breast cancer, it is now clear that, although estrogen-only HT lowers risk, use of combination estrogen-progestin therapy for more than approximately 5 years modestly elevates risk. Each menopausal woman may use this information to make an individual decision regarding use of HT.

In sum, current evidence allows me to feel comfortable counseling most young menopausal women who have bothersome symptoms that the initiation of HT for symptom relief is a safe and reasonable option.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women. Principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321-333.

2. Scarabin PY, Oger E, Plu-Bureau G. Estrogen and THromboembolism Risk (ESTHER) Study Group. Differential association of oral and transdermal oestrogen-replacement therapy with venous thromboembolism risk. Lancet. 2003;362(9382):428-432.

3. Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Rossouw JE, et al. Prior hormone therapy and breast cancer risk in the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial of estrogen and progestin. Maturitas. 2006;55(2):103-115.

4. Million Women Study Collaborators. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet. 2003;362(9382):419-427.

5. Fournier A, Fabre A, Misrine S, et al. Use of different postmenopausal hormone therapies and risk of histology- and hormone receptor-defined invasive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1260-1268.

6. Nelson HD, Vesco KK, Haney E, et al. Nonhormonal therapies for menopausal hot flashes: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2057-2071.

- Is hormone therapy still a valid option? 12 ObGyns address this question

Members of the OBG MANAGEMENT Virtual Board of Editors and Janelle Yates, Senior Editor (May 2011)

Dr. Kaunitz receives grant or research support from Bayer, Agile, Noven, Teva, and Medical Diagnostic Laboratories, is a consultant to Bayer, Merck, and Teva, and owns stock in Becton Dickinson.

Among the developments of the past year in the care of menopausal women are:

- updated guidelines from the Institute of Medicine regarding vitamin D requirements—suggesting that fewer women are deficient in this nutrient than experts had believed

- new data from Europe on hormone therapy (HT) that highlight the safety of transdermal estrogen in comparison with oral administration

- a recent analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), confirming a small elevated risk of breast cancer mortality with use of combination estrogen-progestin HT

- confirmation that age at initiation of HT determines its effect on cardiovascular health

- clarification of the association between HT and dementia

- new data demonstrating modest improvement in hot flushes when the serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) escitalopram is used

- a brand new report from the WHI estrogen-alone arm that shows a protective effect against breast cancer.

The new data on HT suggest that we still have much to learn about its benefits and risks. We also are reaching an understanding that, for many young, symptomatic, menopausal patients, HT can represent a safe choice, with much depending on the timing and duration of therapy.

For more on how your colleagues are managing menopausal patients with and without hormone therapy, see “Is hormone therapy still a valid option? 12 ObGyns address this question,” on the facing page.

Menopausal women need less vitamin D than we thought

Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: IOM; December 2010. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2010/Dietary-Reference-Intakes-for-Calcium-and-Vitamin-D/Vitamin%20D%20and%20Calcium%202010%20Report%20Brief.pdf. Accessed March 24, 2011.

In the 2010 Update on Menopause, I summarized recent findings on vitamin D requirements, including recommendations that menopausal women should take at least 800 IU of vitamin D daily. I also described the prevailing expert opinion that many North American women are deficient in this nutrient.

What a difference a year can make! In late November, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a comprehensive report on vitamin D. Here are some of its conclusions:

- Vitamin D plays an important role in skeletal health but its role in other areas, including cardiovascular disease and cancer, is uncertain

- An intake of 600 IU of vitamin D daily is appropriate for girls and for women as old as 70 years; an in-take of 800 IU daily is appropriate for women older than 70 years

- A serum level of 25-hydroxy vitamin D of 20 ng/mL is consistent with adequate vitamin D status; this is lower than the threshold many have recommended

- With few exceptions, all people who live in North America—including those who have minimal or no exposure to sunlight—are receiving adequate calcium and vitamin D

- Ingestion of more than 4,000 IU of vitamin D daily can cause renal damage and injure other tissues.

The IOM report will likely prompt multivitamin manufacturers to increase the amount of vitamin D contained in their supplements to 600 IU daily. In addition, the report will probably discourage the common practice of checking serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels and prescribing a high dosage of vitamin D supplementation when the level is below 30 ng/mL.

I continue to recommend multivitamin supplements that include calcium and vitamin D (but no iron) to my menopausal patients. However, I no longer routinely recommend that they take additional calcium and vitamin D or undergo assessment of serum vitamin D levels.

Is transdermal estrogen safer than oral administration?

Canonico M, Fournier A, Carcaillon L, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of idiopathic venous thromboembolism: results from the E3N cohort study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(2):340–345.

Renoux C, Dell’aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: a nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2519.

In the WHI, the combination of oral conjugated equine estrogen and medroxyprogesterone acetate more than doubled the risk of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism and modestly increased the risk of stroke, compared with nonuse.1

A year after publication of the initial findings of the WHI estrogen-progestin arm, the Estrogen and THromboEmbolism Risk Study Group (ESTHER) case-control study from France provided evidence that transdermal estrogen does not increase the risk of venous thrombosis.2 In France, many menopausal women use HT, and the transdermal route of administration is common.

In 2010, the E3N cohort study from France also assessed the risk of thrombosis associated with oral and transdermal HT. Investigators followed more than 80,000 postmenopausal women and found that, unlike oral HT, the transdermal route did not increase the risk of venous thrombosis.

More recent evidence also suggests a safety advantage for transdermal HT. The newest data come from the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database, which includes information on more than 870,000 women who were 50 to 70 years old from 1987 to 2006. Investigators identified more than 15,000 women who were given a diagnosis of stroke during this period and compared the use of HT in these women with that of almost 60,000 women in a control group. The risk of stroke associated with current use of transdermal HT was similar to the risk associated with nonuse of HT. Women who used a patch containing 0.05 mg of estradiol or less had a risk of stroke 19% lower than women who did not use HT.

In contrast, the risk of stroke in users of patches that contained a higher dosage of estradiol was almost twice the risk in nonusers of HT. Current users of oral HT had a risk of stroke 28% higher than that of nonusers of HT.

The WHI assessed the risks and benefits of oral HT only. Although no randomized, clinical trial has compared cardiovascular risks among users of oral and transdermal HT, I believe that a preponderance of evidence points to a superior safety profile for the transdermal route, particularly at a dosage of 0.05 mg of estradiol or less.

I encourage my patients who are initiating HT to consider the transdermal route—particularly women who have an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease, including those who are overweight, smoke cigarettes, or who have hypertension or diabetes. I suggest the transdermal route despite its higher cost (oral micronized estradiol can be purchased for as little as $4 for a month’s supply at a chain pharmacy).

When a patient prefers to avoid a patch (because of local irritation), I offer her estradiol gel or spray or the vaginal ring. (Femring is systemic estradiol, whereas Estring is local.) These formulations should provide the same safety benefits as the patch.

Estrogen-progestin HT raises the risk of death from breast cancer

Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Gass M, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2010;304(15):1684–1692.

Toh S, Hernandez-Diaz S, Logan R, Rossouw JE, Hernan MA. Coronary heart disease in postmenopausal recipients of estrogen plus progestin: does the increased risk ever disappear? Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(4):211–217.

In the estrogen-progestin arm of the WHI, initially published in 2002, the risk of invasive breast cancer was modestly elevated (hazard ratio [HR], 1.26) among women who had used HT longer than 5 years.3

In 2010, investigators reported on breast cancer mortality in WHI participants at a mean follow-up of 11 years. They found that combination HT users had breast cancer histology similar to that of nonusers. However, the tumors were more likely to be node-positive in combination HT users (23.7% vs 16.2%). In addition, breast cancer mortality was slightly higher among users of HT (2.6 vs 1.3 deaths in every 10,000 woman-years) (HR, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.00–4.04).

Earlier observational studies had suggested that the death rate from breast cancer is lower in users of combination HT than in nonusers. Consistent with the UK Million Women Study, however, a 2010 report from the WHI found a higher mortality rate among women who have used HT.4

These new WHI findings reinforce the importance of assessing whether micronized progesterone combined with estrogen might lower the risk of death from breast cancer—a possibility suggested by findings of the French E3N cohort study.5

In addition, given the possibility that HT may be cardioprotective when it is initiated within 10 years after the onset of menopause, a WHI report that addresses long-term all-cause mortality would allow us to better counsel our menopausal patients who are trying to decide whether to start or continue HT. See, for example, the data from the California Teachers Study (below) and the estrogen-alone arm of the WHI (page 46).

The findings of this important WHI publication have strengthened the resolve of some clinicians to stop prescribing HT for menopausal women. I continue to prescribe HT to patients who have bothersome vasomotor and related symptoms, however. I also counsel women about the other benefits of HT, which include alleviation of genital atrophy and prevention of osteoporotic fractures. For patients considering or using estrogen-progestin HT, I include discussion of the small increase in their risk of developing, and dying from, breast cancer.

Age at initiation of HT determines its effect on CHD

Stram DO, Liu Y, Henderson KD, et al. Age-specific effects of hormone therapy use on overall mortality and ischemic heart disease mortality among women in the California Teachers Study. Menopause 2011;18(3):253-261.

Allison MA, Manson JE. Age, hormone therapy use, coronary heart disease, and mortality [editorial]. Menopause. 2011;18(3):243-245.

The initial findings of the WHI estrogen-progestin arm suggested that menopausal HT increases the risk of CHD. Since then, however, further analyses from the WHI and other HT trials, as well as reports from the observational Nurses’ Health Study, have suggested that the timing of initiation of HT determines its effect on cardiovascular health.

In this study from the California Teachers Study (CTS), investigators explored the effect of age at initiation of HT on cardiovascular and overall mortality. The CTS is a prospective study of more than 133,000 current and retired female teachers and administrators who returned an initial questionnaire in 1995 and 1996. Participants were then followed until late 2004, or death, whichever came first. More than 71,000 participants were eligible for analysis.

Current HT users were leaner, less likely to smoke, and more likely to exercise and consume alcohol than nonusers were. The analysis was adjusted for a variety of potential cardiovascular and other confounders.

Youngest HT users had the lowest risk of death

During follow-up, 18.3% of never-users of HT died, compared with 17.9% of former users. In contrast, 6.9% of women taking HT at the time of the baseline questionnaire died during follow-up.

Overall, current HT use was associated with a reduced risk of death from CHD (hazard ratio [HR], 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.74–0.95). This risk reduction was most notable (HR, 0.38) in the youngest HT users (36 to 59 years old). The risk of death from CHD gradually increased with the age of current HT users, reaching a hazard ratio of approximately 0.9 in current users who were 70 years and older. However, the CHD mortality hazard ratio did not reach or exceed the referent hazard ratio (1.0) assigned to never users of HT of any age.

The overall mortality rate was lowest for the youngest HT users (HR, 0.54) and approached 1.0 in the oldest current HT users.

The associations between overall and CHD mortality were similar among users of estrogen-only and estrogen-progestin HT.

As Allison and Manson point out in an editorial accompanying this study, the findings from the CTS are congruent with an extensive body of evidence from women and nonhuman primates. These data provide robust reassurance that HT does not increase the risk of death from CHD when it is used by recently menopausal women who have bothersome vasomotor symptoms.

Hormone therapy and dementia: Earlier use is better

Whitmer RA, Quesenberry CP, Zhou J, Yaffe K. Timing of hormone therapy and dementia: the critical window theory revisited. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(1):163–169.

Alzheimer’s disease is more common among women than men. In addition, caregivers to those who have dementia are more likely to be women. Therefore, it’s no surprise that women are especially concerned about their risk of dementia. Menopausal patients in my practice often ask whether use of HT might alter this risk.

Because vasomotor symptoms usually arise in late perimenopause or early menopause, women in observational studies (which reflect clinical practice) tend to begin HT when they are in their late 40s or early 50s. Overall, observational studies have suggested that HT is associated with a reduced risk of dementia. In contrast, the WHI clinical trial, in which the mean age of women who were randomized to HT or placebo was 63 years, found that the initiation of HT later in life increased the risk of dementia.

These observations led to the “critical window” theory regarding HT and dementia: Estrogen protects against dementia when it is taken by perimenopausal or early menopausal women, whereas it is not protective and may even accelerate cognitive decline when it is started many years after the onset of menopause.

In this recent study from the California Kaiser Permanente health maintenance organization, investigators assessed the long-term risk of dementia by timing of HT. From 1964 through 1973, menopausal “midlife” women who were 40 to 55 years old and free of dementia reported whether or not they used HT. Twenty-five to 30 years later, participants were reassessed for “late life” HT use.

Women who used HT in midlife only had the lowest prevalence of dementia, whereas those who used HT only in late life had the highest prevalence. Women who used HT at both time points had a prevalence of dementia similar to that of women who had never used HT.

Given these important findings, I believe it is now reasonable to counsel women in late perimenopause and early menopause that the use of HT may lower their risk of dementia. How long we should continue to prescribe HT depends on individual variables, including the presence of vasomotor symptoms, the risk of osteoporosis, and concerns about breast cancer.

I encourage women to taper their dosage of HT over time, aiming at complete discontinuation or a low maintenance dosage.

Are SRIs an effective alternative to HT for hot flushes?

Freeman EW, Guthrie K, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in healthy menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(3):267–274.

Interest in nonhormonal management of menopausal vasomotor symptoms continues to run high, although only hormonal therapy has FDA approval for this indication. Many trials of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms have focused on breast cancer survivors, many of whom use anti-estrogen agents that increase the prevalence of these symptoms. In contrast, this well-conducted multicenter trial, funded by the National Institutes of Health, enrolled healthy, symptomatic, menopausal women.

In the trial, 205 perimenopausal or postmenopausal women 40 to 62 years old who had at least 28 bothersome or severe episodes of hot flushes and night sweats a week were randomized to 10 mg daily of the SRI escitalopram (Lexapro) or placebo for 8 weeks. Women who did not report a reduction in hot flushes and night sweats of at least 50% at 4 weeks, or a decrease in the severity of these symptoms, were increased to a dosage of 20 mg daily of escitalopram or placebo. The mean baseline frequency of vasomotor symptoms was 9.79.

Within 1 week, women taking the SRI experienced significantly greater improvement than those taking placebo. By 8 weeks, the daily frequency of vasomotor symptoms had diminished by 4.6 hot flushes among women taking the SRI, compared with 3.20 among women taking placebo (P < .01).

Overall, adverse effects were reported by approximately 58% of participants. The pattern of these side effects was similar in the active and placebo treatment arms. No adverse events serious enough to require withdrawal from the study were reported in either arm.

Patient satisfaction with treatment was 70% in the SRI group, compared with 43% among women taking placebo (P < .001).

Although Freeman and colleagues convincingly demonstrate that escitalopram is more effective than placebo, the drug is less effective than HT. I agree with Nelson and coworkers, who, in a meta-analysis of nonhormonal treatments for vasomotor symptoms, concluded: “These therapies may be most useful for highly symptomatic women who cannot take estrogen but are not optimal choices for most women.”6

Unopposed estrogen appears to protect against breast cancer

LaCroix AZ, Chlebowski RT, Manson JE, et al; WHI Investigators. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1305–1314.

The WHI continues to surprise with its findings almost a decade after publication of initial data. In this brand new report from the estrogen-alone arm, postmenopausal, hysterectomized women who were followed for a mean of 10.7 years experienced a reduced risk of breast cancer after a mean of 5.9 years of use of conjugated equine estrogens (CEE).

They experienced no increased or diminished risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), deep venous thrombosis, stroke, hip fracture, colorectal cancer, or total mortality after post-intervention follow-up.

Keep in mind that the women in this arm were instructed to discontinue the study medication at the time the intervention phase was halted because of an increased risk of stroke among CEE users. The elevated risk of stroke attenuated with the longer follow-up.

All ages experienced a reduced risk of breast cancer

Some subgroup analyses from the WHI have found differential effects of HT by age of the user, with younger women experiencing fewer risks and more benefits than those who are more than 10 years past the menopausal transition. In this analysis, all three age groups (50–59 years, 60–69 years, and 70–79 years) of women who used CEE had a reduced risk of breast cancer, compared with placebo users.

Other risks did appear to differ by age. For example, the overall hazard ratio for CHD was 0.59 among CEE users 50 to 59 years old, but it approached unity among the older women.