User login

Are new tools for correcting prolapse and incontinence better just because they’re new?

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

From my vantage point, it appears that economic factors are playing an increasingly important role in how pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and urinary incontinence (UI) are managed—particularly, in regard to the use of surgical devices. As such, the topic of treating POP and UI deserves our attention to ensure that we make the best decisions for our patients.

Now, I’m a staunch supporter of innovation in treatment; certainly, there is room for improvement in current approaches—particularly in surgery—for treating POP and UI. At the same time, I strongly believe that innovation must be demonstrated to be an improvement before it is incorporated into practice. Although innovation is commonly taken on faith, we should know better than to equate “new” with “better” until evidence, gathered through clinical research, has demonstrated this conclusively. A look at the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) process for clearing medical devices for clinical use reveals that such a standard often doesn’t apply—and this should matter to us.

The meaning of 510(k)

Most medical devices are evaluated through an FDA clearance mechanism known as the 510(k) process. This is wholly distinct from the agency’s drug approval process with which most of us are familiar. It’s beyond the scope of this commentary for me to go into detail about 510(k); if you are interested, see two recent commentaries1,2 and visit http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/devadvice/314.html.

In a nutshell, the 510(k) process requires only that an applicant demonstrate that a new medical device has “substantial equivalence” to an already legally marketed device, known as the predicate, which may also have been cleared only through the 510(k) process. That means it’s possible to have generations of products cleared on the basis of one predicate device that was itself never studied adequately.

Indeed, this is the case with most medical devices that have been sold for the surgical treatment of POP and UI—from before the ProteGen Sling (Boston Scientific), through Tension-Free Vaginal Tape (TVT) (Gynecare), and continuing with the newest devices.

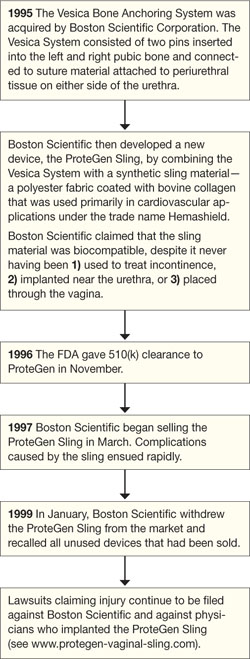

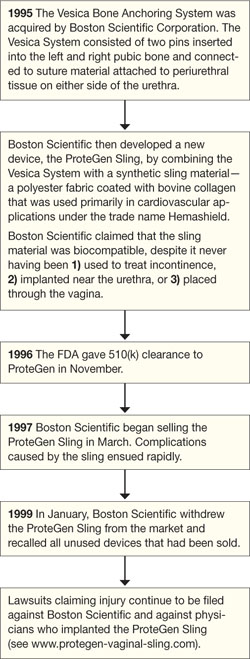

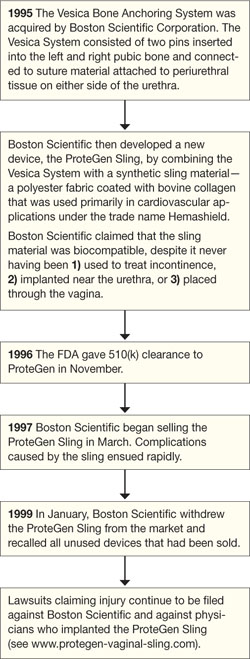

The story of the ProteGen Sling (FIGURE) offers a cautionary tale about what can go wrong when new devices are cleared by the FDA through 510(k), rather than evaluated through rigorous clinical trials, as drugs are. More recently, experience with the ObTape (Mentor Corporation) followed virtually the same trajectory of events; the product was pulled from the market in 2006 and is now the focus of lawsuits nationwide.

Fortunately, for our patients, experience with TVT (Gynecare) has been favorable. Although TVT was also cleared by the FDA through 510(k), clinical research performed after TVT was introduced has demonstrated its effectiveness and relative safety. Indeed, TVT has revolutionized the treatment of stress UI in women—and, even, our understanding of its etiology.

Several companies are capitalizing on the success of TVT by introducing competing products that are designed to be 1) similar enough to ride on the coattails of TVT yet 2) different enough to capture their own share of market—without evidence of safety or effectiveness required. Even Gynecare (part of Ethicon Women’s Health and Urology, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson) has introduced TVT SECUR to compete with its own TVT—again, without independent evidence of safety or effectiveness.

The current market in devices for stress UI is a moving target that makes it nearly impossible—even for research organizations, such as the federally funded Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, that are independent of industry—to develop and implement sound clinical trials of those devices. Why do I say “moving target”? First, there are no assurances that any device chosen for study will remain the same for the duration of a trial. Second, there is no way to foresee which products will be abandoned over the time required for a large clinical trial.

FIGURE The saga of the ProteGen Sling

Transparency over what might be considered “experimental”

Until the FDA changes its process—to one in which 1) medical devices are adequately assessed before they reach market and 2) postmarketing surveillance is required—it’s our duty to insist on evidence of safety and effectiveness before adopting the latest and greatest products that companies have to offer.

Of all the questions that a patient might ask before treatment, three of the most important, surely, are:

- “Will this help me?”

- “If it helps me, how long will it help?”

- “Whether or not this treatment helps me, what risks—in the short-term and over the long-term—does it present?”

Until we can provide our patients with answers that are supported by evidence, products that lack such evidence should be considered experimental, and patients should be counseled accordingly.

Some patients may accept what they’ve been advised are new and unproven treatments—in the way that some physicians are early adopters. Nevertheless, I am concerned that some clinicians do not appear to appreciate the true lack of evidence that accompanies most marketed devices for prolapse and incontinence. They may mistake the FDA 510(k) process of clearance for something similar to the agency’s extended and complex drug approval process. They may accept claims made in industry-produced white papers that are often largely promotional materials, and fail to look further into those claims.

Now, more than ever and above all else, we must stand between marketing and our patients’ safety. We are familiar with the toll that prolapse and incontinence, as chronic conditions, take on our patients; yet it’s that very chronic nature that should lead us to adopt patience and caution in accepting new treatments before they have been adequately studied.

If we cannot always rely on industry to provide clear information about the risks and benefits of new devices, neither can we routinely look to our professional organizations for unbiased information. Often, professional organizations accept cash contributions from industry, raising the question of conflict of interest that may undermine their actions when the priorities of industry do not align with the goal of safeguarding patients’ well-being.

In an unprecedented example of how a professional association can interfere with its own, expert-authored clinical practice guidelines, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) more than a year ago rescinded one of its published guidelines on POP (Issue 79, February 20073) and replaced it with a new guideline (Issue 85, September 20074). The new guideline is nearly identical to the prior one—save for one sentence, in which “experimental” is deleted in a discussion of kits of trocar-based synthetic materials sold for the surgical treatment of pelvic organ prolapse (see the EXCERPT).

The deletion is crucial because offering informed consent for surgery requires a patient to accept risks in balance with an expectation of benefit. A patient cannot be appropriately informed when no evidence of benefit exists and evidence of postoperative risk is extremely limited.

Now, I am not declaring that ACOG acted with bias because of a financial conflict of interest with industry in this instance; the fact that a financial conflict of interest exists for ACOG, however, cannot be disputed if one examines the College’s Annual Report, where contributors are listed. (For a comprehensive, if disillusioning, treatise on the many effects of financial conflict of interest within medicine, I recommend the book On The Take.5)

organ prolapse

Differences between the two bulletins are marked in boldface

Bulletin #79 (original wording): “Given the limited data and frequent changes in the marketed products (particularly with regard to type of mesh material itself, which is most closely associated with several of the postoperative risks especially mesh erosion), if clinicians recommend these procedures before evidence of their risk-benefit is fully understood, the procedures should be considered experimental and patients consented for surgery with that understanding.”

Bulletin #84 (revised wording): “Given the limited data and frequent changes in the marketed products for vaginal surgery for prolapse repair (particularly with regard to type of mesh material itself, which is most closely associated with several of the postoperative risks especially mesh erosion), patients should consent to surgery with an understanding of the post-operative risks and lack of long-term outcomes data.”

Case: Radiofrequency therapy. Even when clinical experience demonstrates lack of effectiveness or an unacceptable rate of complications associated with certain techniques or devices, unequivocal evidence of such problems does not always appear in the literature. One example of this is how a technique was translated into a treatment for incontinence by way of its use in other fields.

Radiofrequency has, among other uses, been used to ablate nerves in intractable chronic pain and to address joint instability in orthopedic surgery. Radiofrequency energy was then, by extension, applied transvaginally to tissue (known as “endopelvic” fascia, of a distinctly different nature than parietal fascia involved in orthopedic procedures) surrounding the urethra. The goal was to coagulate “supporting” tissues and “correct” urethral hypermobility that purportedly causes stress incontinence.

Marketing of the SURx Transvaginal System (CooperSurgical, Inc.) began in 2002, followed by reports of success. One industry-sponsored study, for example, reported a 73% rate of either continence or improvement after 12 months.6

Despite such favorable early results, however, in 2006 CooperSurgical decided to abandon this system, citing “technique-dependent” results of the procedure. Since then, independent research has shown a very low initial success rate that declines rapidly—within weeks or months—of treatment.7,8

A different radiofrequency technique continues to be marketed—the Renessa System™ (NovaSys Medical), which uses a urethral catheter-mounted system to deliver radiofrequency energy through the urethral mucosa to the submucosa and adjacent tissues. Once again, initial reports of industry-sponsored research showed promising results; one study of 110 patients reported 74% achieved continence or improvement after 1 year.9 In a follow-up report of 21 of the original 110 patients, “improvement” was reported in 74% after 3 years.10 Independent research has yet to be reported in the literature.

Of particular concern, no data exist on the long-term effect of denaturing collagen in the urethra and adjacent tissues in relation to UI, other aspects of bladder function, or sexual function. An apparent lack of immediate complications cannot be equated with safety; we need long-term studies to determine whether urethral function is affected adversely compared with that in untreated women and women treated with surgery.

Bring on innovation—in context!

For those who consider my argument anti-innovation, let me repeat: I believe strongly in innovation to improve care for our patients. Am I anti-industry? Only when there is an unbridled race to profit from marketing products without safeguards to ensure, first and foremost, the safety of our patients and, second, their long-term effectiveness. Knowingly or unknowingly, patients then become the guinea pigs on whom these products are tested—just not in the appropriate context of clinical research and informed consent for participation.

Instead (as happened in the US Public Health Service’s Tuskegee syphilis experiments), patients serve as research subjects without their consent when they receive untested products and undergo unproven treatments. And because clinicians are the conduit through which patients receive untested and unproven treatments, who is ultimately responsible for the outcome?

Industry brings innovation to clinical practice. But it is incumbent on clinicians to recognize, with unflinching honesty, the bottom line on which industry operates. Prolapse and incontinence are deeply distressing for our patients, but these chronic conditions are not life-threatening; virtually all women who suffer these conditions have been symptomatic for years before they come for care. I see no need, except to increase that bottom line, to rush products to market before they have been evaluated sufficiently to determine whether “new” is actually “better.”

For clinicians who style themselves as early adopters, remember: It’s not you, but your patient, who is “adopting” a foreign material and having it placed deep in the most intimate area of her body—a foreign material intended to stay for life (except for those unfortunate patients who must have it removed). Above all, we must do no harm—an elusive goal when some of us try to attract patients by being the first to use a product before evidence of its risk and utility have been established in practice.

Does this kind of talk encourage litigation?

Does a commentary like this one provide fodder for plaintiff attorneys who are seeking grounds for product liability lawsuits against manufacturers and malpractice claims against clinicians? Please! Spend a moment on the Web, and you will see that the lawyers are already busy—especially since the FDA’s October 2008 alert about complications with surgical mesh for prolapse and incontinence. [See “FDA alert: Transvaginal placement of surgical mesh carries serious risks,” in the December 2008 issue of OBG Management.] It’s worth noting how these lawyers see themselves: They would likely tell you that they “provide an important service in protecting patients from unscrupulous manufacturers who profit from the vulnerability of people seeking treatment for distressing conditions.” As clinicians, are we absolutely sure that we can say the same of ourselves?

Is it wrong to harp on what happened in the past?

Why revisit events surrounding, for example, the ProteGen Sling? My reply is another question: Where is the evidence that such sequences of events are in the past? Among clinicians, who knows which is best in a collection of kits that changes from one month to the next, without their promoters skipping a beat in proclaiming theirs as the “best”? It isn’t shameful to admit that one doesn’t know which one is best; but it is a shame to act as if one does know, especially when the risk falls to another. The names change; the events are the same.

What is the solution to this problem?

Businesses succeed only when their products are purchased. If clinicians refused to be participants whenever the device industry introduces unproven treatments into the market, industry would be compelled to test their products beforehand. Patients would benefit—by being able to make truly informed choices, with adequate information about risk and benefit. Clinicians would benefit—by being able to provide the most effective treatment without sacrificing their integrity in the process. Ultimately, industry would benefit, by profiting appropriately from products that truly help our patients. Is that an impossible wish?

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Goldman HB. Is new always better? Curr Urol Rep. 2007;8(4):253-254.

2. Ostergard DR. Lessons from the past: directions for the future. Do new marketed surgical procedures and grafts produce ethical, personal liability, and legal concerns for physicians? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:591-598.

3. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 79: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 Pt 1):461-473.

4. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:717-729.

5. Kassirer JP. On the Take: How Medicine’s Complicity with Big Business Can Endanger Your Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

6. Dmochowski RR, Avon M, Ross J, et al. Transvaginal radiofrequency treatment of the endopelvic fascia: a prospective evaluation for the treatment of genuine stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2003;169:1028-1032.

7. Buchsbaum GM, McConville J, Korni R, Duecy EE. Outcome of transvaginal radiofrequency for treatment of women with stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(3):263-265.

8. Ismail SI. Radiofrequency remodelling of the endopelvic fascia is not an effective procedure for urodynamic stress incontinence in women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1205-1209.

9. Appell RA, Juma S, Wells WG, et al. Transurethral radio-frequency energy collagen micro-remodeling for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2006;25(4):331-336.

10. Appell RA, Singh G, Klimberg IW, et al. Nonsurgical radiofrequency collagen denaturation for stress urinary incontinence: retrospective 3-year evaluation. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2007;4:455-461.

just because they’re new;Anne M. Weber MD;Commentary;economic factors;urinary incontinence;pelvic organ prolapse;POP;transvaginal mesh;urethral sling;UI;innovation in treatment;FDA;medical device;510(k);ProteGen Sling;ObTape;TVT;Gynecare;TVT Secur;early adopters;ACOG;Clinical Practice Bulletin;informed consent;financial conflict of interest;radiofrequency therapy;SURx Transvaginal system;Renessa;do no harm;FDA Alert;

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

From my vantage point, it appears that economic factors are playing an increasingly important role in how pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and urinary incontinence (UI) are managed—particularly, in regard to the use of surgical devices. As such, the topic of treating POP and UI deserves our attention to ensure that we make the best decisions for our patients.

Now, I’m a staunch supporter of innovation in treatment; certainly, there is room for improvement in current approaches—particularly in surgery—for treating POP and UI. At the same time, I strongly believe that innovation must be demonstrated to be an improvement before it is incorporated into practice. Although innovation is commonly taken on faith, we should know better than to equate “new” with “better” until evidence, gathered through clinical research, has demonstrated this conclusively. A look at the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) process for clearing medical devices for clinical use reveals that such a standard often doesn’t apply—and this should matter to us.

The meaning of 510(k)

Most medical devices are evaluated through an FDA clearance mechanism known as the 510(k) process. This is wholly distinct from the agency’s drug approval process with which most of us are familiar. It’s beyond the scope of this commentary for me to go into detail about 510(k); if you are interested, see two recent commentaries1,2 and visit http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/devadvice/314.html.

In a nutshell, the 510(k) process requires only that an applicant demonstrate that a new medical device has “substantial equivalence” to an already legally marketed device, known as the predicate, which may also have been cleared only through the 510(k) process. That means it’s possible to have generations of products cleared on the basis of one predicate device that was itself never studied adequately.

Indeed, this is the case with most medical devices that have been sold for the surgical treatment of POP and UI—from before the ProteGen Sling (Boston Scientific), through Tension-Free Vaginal Tape (TVT) (Gynecare), and continuing with the newest devices.

The story of the ProteGen Sling (FIGURE) offers a cautionary tale about what can go wrong when new devices are cleared by the FDA through 510(k), rather than evaluated through rigorous clinical trials, as drugs are. More recently, experience with the ObTape (Mentor Corporation) followed virtually the same trajectory of events; the product was pulled from the market in 2006 and is now the focus of lawsuits nationwide.

Fortunately, for our patients, experience with TVT (Gynecare) has been favorable. Although TVT was also cleared by the FDA through 510(k), clinical research performed after TVT was introduced has demonstrated its effectiveness and relative safety. Indeed, TVT has revolutionized the treatment of stress UI in women—and, even, our understanding of its etiology.

Several companies are capitalizing on the success of TVT by introducing competing products that are designed to be 1) similar enough to ride on the coattails of TVT yet 2) different enough to capture their own share of market—without evidence of safety or effectiveness required. Even Gynecare (part of Ethicon Women’s Health and Urology, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson) has introduced TVT SECUR to compete with its own TVT—again, without independent evidence of safety or effectiveness.

The current market in devices for stress UI is a moving target that makes it nearly impossible—even for research organizations, such as the federally funded Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, that are independent of industry—to develop and implement sound clinical trials of those devices. Why do I say “moving target”? First, there are no assurances that any device chosen for study will remain the same for the duration of a trial. Second, there is no way to foresee which products will be abandoned over the time required for a large clinical trial.

FIGURE The saga of the ProteGen Sling

Transparency over what might be considered “experimental”

Until the FDA changes its process—to one in which 1) medical devices are adequately assessed before they reach market and 2) postmarketing surveillance is required—it’s our duty to insist on evidence of safety and effectiveness before adopting the latest and greatest products that companies have to offer.

Of all the questions that a patient might ask before treatment, three of the most important, surely, are:

- “Will this help me?”

- “If it helps me, how long will it help?”

- “Whether or not this treatment helps me, what risks—in the short-term and over the long-term—does it present?”

Until we can provide our patients with answers that are supported by evidence, products that lack such evidence should be considered experimental, and patients should be counseled accordingly.

Some patients may accept what they’ve been advised are new and unproven treatments—in the way that some physicians are early adopters. Nevertheless, I am concerned that some clinicians do not appear to appreciate the true lack of evidence that accompanies most marketed devices for prolapse and incontinence. They may mistake the FDA 510(k) process of clearance for something similar to the agency’s extended and complex drug approval process. They may accept claims made in industry-produced white papers that are often largely promotional materials, and fail to look further into those claims.

Now, more than ever and above all else, we must stand between marketing and our patients’ safety. We are familiar with the toll that prolapse and incontinence, as chronic conditions, take on our patients; yet it’s that very chronic nature that should lead us to adopt patience and caution in accepting new treatments before they have been adequately studied.

If we cannot always rely on industry to provide clear information about the risks and benefits of new devices, neither can we routinely look to our professional organizations for unbiased information. Often, professional organizations accept cash contributions from industry, raising the question of conflict of interest that may undermine their actions when the priorities of industry do not align with the goal of safeguarding patients’ well-being.

In an unprecedented example of how a professional association can interfere with its own, expert-authored clinical practice guidelines, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) more than a year ago rescinded one of its published guidelines on POP (Issue 79, February 20073) and replaced it with a new guideline (Issue 85, September 20074). The new guideline is nearly identical to the prior one—save for one sentence, in which “experimental” is deleted in a discussion of kits of trocar-based synthetic materials sold for the surgical treatment of pelvic organ prolapse (see the EXCERPT).

The deletion is crucial because offering informed consent for surgery requires a patient to accept risks in balance with an expectation of benefit. A patient cannot be appropriately informed when no evidence of benefit exists and evidence of postoperative risk is extremely limited.

Now, I am not declaring that ACOG acted with bias because of a financial conflict of interest with industry in this instance; the fact that a financial conflict of interest exists for ACOG, however, cannot be disputed if one examines the College’s Annual Report, where contributors are listed. (For a comprehensive, if disillusioning, treatise on the many effects of financial conflict of interest within medicine, I recommend the book On The Take.5)

organ prolapse

Differences between the two bulletins are marked in boldface

Bulletin #79 (original wording): “Given the limited data and frequent changes in the marketed products (particularly with regard to type of mesh material itself, which is most closely associated with several of the postoperative risks especially mesh erosion), if clinicians recommend these procedures before evidence of their risk-benefit is fully understood, the procedures should be considered experimental and patients consented for surgery with that understanding.”

Bulletin #84 (revised wording): “Given the limited data and frequent changes in the marketed products for vaginal surgery for prolapse repair (particularly with regard to type of mesh material itself, which is most closely associated with several of the postoperative risks especially mesh erosion), patients should consent to surgery with an understanding of the post-operative risks and lack of long-term outcomes data.”

Case: Radiofrequency therapy. Even when clinical experience demonstrates lack of effectiveness or an unacceptable rate of complications associated with certain techniques or devices, unequivocal evidence of such problems does not always appear in the literature. One example of this is how a technique was translated into a treatment for incontinence by way of its use in other fields.

Radiofrequency has, among other uses, been used to ablate nerves in intractable chronic pain and to address joint instability in orthopedic surgery. Radiofrequency energy was then, by extension, applied transvaginally to tissue (known as “endopelvic” fascia, of a distinctly different nature than parietal fascia involved in orthopedic procedures) surrounding the urethra. The goal was to coagulate “supporting” tissues and “correct” urethral hypermobility that purportedly causes stress incontinence.

Marketing of the SURx Transvaginal System (CooperSurgical, Inc.) began in 2002, followed by reports of success. One industry-sponsored study, for example, reported a 73% rate of either continence or improvement after 12 months.6

Despite such favorable early results, however, in 2006 CooperSurgical decided to abandon this system, citing “technique-dependent” results of the procedure. Since then, independent research has shown a very low initial success rate that declines rapidly—within weeks or months—of treatment.7,8

A different radiofrequency technique continues to be marketed—the Renessa System™ (NovaSys Medical), which uses a urethral catheter-mounted system to deliver radiofrequency energy through the urethral mucosa to the submucosa and adjacent tissues. Once again, initial reports of industry-sponsored research showed promising results; one study of 110 patients reported 74% achieved continence or improvement after 1 year.9 In a follow-up report of 21 of the original 110 patients, “improvement” was reported in 74% after 3 years.10 Independent research has yet to be reported in the literature.

Of particular concern, no data exist on the long-term effect of denaturing collagen in the urethra and adjacent tissues in relation to UI, other aspects of bladder function, or sexual function. An apparent lack of immediate complications cannot be equated with safety; we need long-term studies to determine whether urethral function is affected adversely compared with that in untreated women and women treated with surgery.

Bring on innovation—in context!

For those who consider my argument anti-innovation, let me repeat: I believe strongly in innovation to improve care for our patients. Am I anti-industry? Only when there is an unbridled race to profit from marketing products without safeguards to ensure, first and foremost, the safety of our patients and, second, their long-term effectiveness. Knowingly or unknowingly, patients then become the guinea pigs on whom these products are tested—just not in the appropriate context of clinical research and informed consent for participation.

Instead (as happened in the US Public Health Service’s Tuskegee syphilis experiments), patients serve as research subjects without their consent when they receive untested products and undergo unproven treatments. And because clinicians are the conduit through which patients receive untested and unproven treatments, who is ultimately responsible for the outcome?

Industry brings innovation to clinical practice. But it is incumbent on clinicians to recognize, with unflinching honesty, the bottom line on which industry operates. Prolapse and incontinence are deeply distressing for our patients, but these chronic conditions are not life-threatening; virtually all women who suffer these conditions have been symptomatic for years before they come for care. I see no need, except to increase that bottom line, to rush products to market before they have been evaluated sufficiently to determine whether “new” is actually “better.”

For clinicians who style themselves as early adopters, remember: It’s not you, but your patient, who is “adopting” a foreign material and having it placed deep in the most intimate area of her body—a foreign material intended to stay for life (except for those unfortunate patients who must have it removed). Above all, we must do no harm—an elusive goal when some of us try to attract patients by being the first to use a product before evidence of its risk and utility have been established in practice.

Does this kind of talk encourage litigation?

Does a commentary like this one provide fodder for plaintiff attorneys who are seeking grounds for product liability lawsuits against manufacturers and malpractice claims against clinicians? Please! Spend a moment on the Web, and you will see that the lawyers are already busy—especially since the FDA’s October 2008 alert about complications with surgical mesh for prolapse and incontinence. [See “FDA alert: Transvaginal placement of surgical mesh carries serious risks,” in the December 2008 issue of OBG Management.] It’s worth noting how these lawyers see themselves: They would likely tell you that they “provide an important service in protecting patients from unscrupulous manufacturers who profit from the vulnerability of people seeking treatment for distressing conditions.” As clinicians, are we absolutely sure that we can say the same of ourselves?

Is it wrong to harp on what happened in the past?

Why revisit events surrounding, for example, the ProteGen Sling? My reply is another question: Where is the evidence that such sequences of events are in the past? Among clinicians, who knows which is best in a collection of kits that changes from one month to the next, without their promoters skipping a beat in proclaiming theirs as the “best”? It isn’t shameful to admit that one doesn’t know which one is best; but it is a shame to act as if one does know, especially when the risk falls to another. The names change; the events are the same.

What is the solution to this problem?

Businesses succeed only when their products are purchased. If clinicians refused to be participants whenever the device industry introduces unproven treatments into the market, industry would be compelled to test their products beforehand. Patients would benefit—by being able to make truly informed choices, with adequate information about risk and benefit. Clinicians would benefit—by being able to provide the most effective treatment without sacrificing their integrity in the process. Ultimately, industry would benefit, by profiting appropriately from products that truly help our patients. Is that an impossible wish?

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

From my vantage point, it appears that economic factors are playing an increasingly important role in how pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and urinary incontinence (UI) are managed—particularly, in regard to the use of surgical devices. As such, the topic of treating POP and UI deserves our attention to ensure that we make the best decisions for our patients.

Now, I’m a staunch supporter of innovation in treatment; certainly, there is room for improvement in current approaches—particularly in surgery—for treating POP and UI. At the same time, I strongly believe that innovation must be demonstrated to be an improvement before it is incorporated into practice. Although innovation is commonly taken on faith, we should know better than to equate “new” with “better” until evidence, gathered through clinical research, has demonstrated this conclusively. A look at the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) process for clearing medical devices for clinical use reveals that such a standard often doesn’t apply—and this should matter to us.

The meaning of 510(k)

Most medical devices are evaluated through an FDA clearance mechanism known as the 510(k) process. This is wholly distinct from the agency’s drug approval process with which most of us are familiar. It’s beyond the scope of this commentary for me to go into detail about 510(k); if you are interested, see two recent commentaries1,2 and visit http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/devadvice/314.html.

In a nutshell, the 510(k) process requires only that an applicant demonstrate that a new medical device has “substantial equivalence” to an already legally marketed device, known as the predicate, which may also have been cleared only through the 510(k) process. That means it’s possible to have generations of products cleared on the basis of one predicate device that was itself never studied adequately.

Indeed, this is the case with most medical devices that have been sold for the surgical treatment of POP and UI—from before the ProteGen Sling (Boston Scientific), through Tension-Free Vaginal Tape (TVT) (Gynecare), and continuing with the newest devices.

The story of the ProteGen Sling (FIGURE) offers a cautionary tale about what can go wrong when new devices are cleared by the FDA through 510(k), rather than evaluated through rigorous clinical trials, as drugs are. More recently, experience with the ObTape (Mentor Corporation) followed virtually the same trajectory of events; the product was pulled from the market in 2006 and is now the focus of lawsuits nationwide.

Fortunately, for our patients, experience with TVT (Gynecare) has been favorable. Although TVT was also cleared by the FDA through 510(k), clinical research performed after TVT was introduced has demonstrated its effectiveness and relative safety. Indeed, TVT has revolutionized the treatment of stress UI in women—and, even, our understanding of its etiology.

Several companies are capitalizing on the success of TVT by introducing competing products that are designed to be 1) similar enough to ride on the coattails of TVT yet 2) different enough to capture their own share of market—without evidence of safety or effectiveness required. Even Gynecare (part of Ethicon Women’s Health and Urology, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson) has introduced TVT SECUR to compete with its own TVT—again, without independent evidence of safety or effectiveness.

The current market in devices for stress UI is a moving target that makes it nearly impossible—even for research organizations, such as the federally funded Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, that are independent of industry—to develop and implement sound clinical trials of those devices. Why do I say “moving target”? First, there are no assurances that any device chosen for study will remain the same for the duration of a trial. Second, there is no way to foresee which products will be abandoned over the time required for a large clinical trial.

FIGURE The saga of the ProteGen Sling

Transparency over what might be considered “experimental”

Until the FDA changes its process—to one in which 1) medical devices are adequately assessed before they reach market and 2) postmarketing surveillance is required—it’s our duty to insist on evidence of safety and effectiveness before adopting the latest and greatest products that companies have to offer.

Of all the questions that a patient might ask before treatment, three of the most important, surely, are:

- “Will this help me?”

- “If it helps me, how long will it help?”

- “Whether or not this treatment helps me, what risks—in the short-term and over the long-term—does it present?”

Until we can provide our patients with answers that are supported by evidence, products that lack such evidence should be considered experimental, and patients should be counseled accordingly.

Some patients may accept what they’ve been advised are new and unproven treatments—in the way that some physicians are early adopters. Nevertheless, I am concerned that some clinicians do not appear to appreciate the true lack of evidence that accompanies most marketed devices for prolapse and incontinence. They may mistake the FDA 510(k) process of clearance for something similar to the agency’s extended and complex drug approval process. They may accept claims made in industry-produced white papers that are often largely promotional materials, and fail to look further into those claims.

Now, more than ever and above all else, we must stand between marketing and our patients’ safety. We are familiar with the toll that prolapse and incontinence, as chronic conditions, take on our patients; yet it’s that very chronic nature that should lead us to adopt patience and caution in accepting new treatments before they have been adequately studied.

If we cannot always rely on industry to provide clear information about the risks and benefits of new devices, neither can we routinely look to our professional organizations for unbiased information. Often, professional organizations accept cash contributions from industry, raising the question of conflict of interest that may undermine their actions when the priorities of industry do not align with the goal of safeguarding patients’ well-being.

In an unprecedented example of how a professional association can interfere with its own, expert-authored clinical practice guidelines, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) more than a year ago rescinded one of its published guidelines on POP (Issue 79, February 20073) and replaced it with a new guideline (Issue 85, September 20074). The new guideline is nearly identical to the prior one—save for one sentence, in which “experimental” is deleted in a discussion of kits of trocar-based synthetic materials sold for the surgical treatment of pelvic organ prolapse (see the EXCERPT).

The deletion is crucial because offering informed consent for surgery requires a patient to accept risks in balance with an expectation of benefit. A patient cannot be appropriately informed when no evidence of benefit exists and evidence of postoperative risk is extremely limited.

Now, I am not declaring that ACOG acted with bias because of a financial conflict of interest with industry in this instance; the fact that a financial conflict of interest exists for ACOG, however, cannot be disputed if one examines the College’s Annual Report, where contributors are listed. (For a comprehensive, if disillusioning, treatise on the many effects of financial conflict of interest within medicine, I recommend the book On The Take.5)

organ prolapse

Differences between the two bulletins are marked in boldface

Bulletin #79 (original wording): “Given the limited data and frequent changes in the marketed products (particularly with regard to type of mesh material itself, which is most closely associated with several of the postoperative risks especially mesh erosion), if clinicians recommend these procedures before evidence of their risk-benefit is fully understood, the procedures should be considered experimental and patients consented for surgery with that understanding.”

Bulletin #84 (revised wording): “Given the limited data and frequent changes in the marketed products for vaginal surgery for prolapse repair (particularly with regard to type of mesh material itself, which is most closely associated with several of the postoperative risks especially mesh erosion), patients should consent to surgery with an understanding of the post-operative risks and lack of long-term outcomes data.”

Case: Radiofrequency therapy. Even when clinical experience demonstrates lack of effectiveness or an unacceptable rate of complications associated with certain techniques or devices, unequivocal evidence of such problems does not always appear in the literature. One example of this is how a technique was translated into a treatment for incontinence by way of its use in other fields.

Radiofrequency has, among other uses, been used to ablate nerves in intractable chronic pain and to address joint instability in orthopedic surgery. Radiofrequency energy was then, by extension, applied transvaginally to tissue (known as “endopelvic” fascia, of a distinctly different nature than parietal fascia involved in orthopedic procedures) surrounding the urethra. The goal was to coagulate “supporting” tissues and “correct” urethral hypermobility that purportedly causes stress incontinence.

Marketing of the SURx Transvaginal System (CooperSurgical, Inc.) began in 2002, followed by reports of success. One industry-sponsored study, for example, reported a 73% rate of either continence or improvement after 12 months.6

Despite such favorable early results, however, in 2006 CooperSurgical decided to abandon this system, citing “technique-dependent” results of the procedure. Since then, independent research has shown a very low initial success rate that declines rapidly—within weeks or months—of treatment.7,8

A different radiofrequency technique continues to be marketed—the Renessa System™ (NovaSys Medical), which uses a urethral catheter-mounted system to deliver radiofrequency energy through the urethral mucosa to the submucosa and adjacent tissues. Once again, initial reports of industry-sponsored research showed promising results; one study of 110 patients reported 74% achieved continence or improvement after 1 year.9 In a follow-up report of 21 of the original 110 patients, “improvement” was reported in 74% after 3 years.10 Independent research has yet to be reported in the literature.

Of particular concern, no data exist on the long-term effect of denaturing collagen in the urethra and adjacent tissues in relation to UI, other aspects of bladder function, or sexual function. An apparent lack of immediate complications cannot be equated with safety; we need long-term studies to determine whether urethral function is affected adversely compared with that in untreated women and women treated with surgery.

Bring on innovation—in context!

For those who consider my argument anti-innovation, let me repeat: I believe strongly in innovation to improve care for our patients. Am I anti-industry? Only when there is an unbridled race to profit from marketing products without safeguards to ensure, first and foremost, the safety of our patients and, second, their long-term effectiveness. Knowingly or unknowingly, patients then become the guinea pigs on whom these products are tested—just not in the appropriate context of clinical research and informed consent for participation.

Instead (as happened in the US Public Health Service’s Tuskegee syphilis experiments), patients serve as research subjects without their consent when they receive untested products and undergo unproven treatments. And because clinicians are the conduit through which patients receive untested and unproven treatments, who is ultimately responsible for the outcome?

Industry brings innovation to clinical practice. But it is incumbent on clinicians to recognize, with unflinching honesty, the bottom line on which industry operates. Prolapse and incontinence are deeply distressing for our patients, but these chronic conditions are not life-threatening; virtually all women who suffer these conditions have been symptomatic for years before they come for care. I see no need, except to increase that bottom line, to rush products to market before they have been evaluated sufficiently to determine whether “new” is actually “better.”

For clinicians who style themselves as early adopters, remember: It’s not you, but your patient, who is “adopting” a foreign material and having it placed deep in the most intimate area of her body—a foreign material intended to stay for life (except for those unfortunate patients who must have it removed). Above all, we must do no harm—an elusive goal when some of us try to attract patients by being the first to use a product before evidence of its risk and utility have been established in practice.

Does this kind of talk encourage litigation?

Does a commentary like this one provide fodder for plaintiff attorneys who are seeking grounds for product liability lawsuits against manufacturers and malpractice claims against clinicians? Please! Spend a moment on the Web, and you will see that the lawyers are already busy—especially since the FDA’s October 2008 alert about complications with surgical mesh for prolapse and incontinence. [See “FDA alert: Transvaginal placement of surgical mesh carries serious risks,” in the December 2008 issue of OBG Management.] It’s worth noting how these lawyers see themselves: They would likely tell you that they “provide an important service in protecting patients from unscrupulous manufacturers who profit from the vulnerability of people seeking treatment for distressing conditions.” As clinicians, are we absolutely sure that we can say the same of ourselves?

Is it wrong to harp on what happened in the past?

Why revisit events surrounding, for example, the ProteGen Sling? My reply is another question: Where is the evidence that such sequences of events are in the past? Among clinicians, who knows which is best in a collection of kits that changes from one month to the next, without their promoters skipping a beat in proclaiming theirs as the “best”? It isn’t shameful to admit that one doesn’t know which one is best; but it is a shame to act as if one does know, especially when the risk falls to another. The names change; the events are the same.

What is the solution to this problem?

Businesses succeed only when their products are purchased. If clinicians refused to be participants whenever the device industry introduces unproven treatments into the market, industry would be compelled to test their products beforehand. Patients would benefit—by being able to make truly informed choices, with adequate information about risk and benefit. Clinicians would benefit—by being able to provide the most effective treatment without sacrificing their integrity in the process. Ultimately, industry would benefit, by profiting appropriately from products that truly help our patients. Is that an impossible wish?

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Goldman HB. Is new always better? Curr Urol Rep. 2007;8(4):253-254.

2. Ostergard DR. Lessons from the past: directions for the future. Do new marketed surgical procedures and grafts produce ethical, personal liability, and legal concerns for physicians? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:591-598.

3. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 79: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 Pt 1):461-473.

4. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:717-729.

5. Kassirer JP. On the Take: How Medicine’s Complicity with Big Business Can Endanger Your Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

6. Dmochowski RR, Avon M, Ross J, et al. Transvaginal radiofrequency treatment of the endopelvic fascia: a prospective evaluation for the treatment of genuine stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2003;169:1028-1032.

7. Buchsbaum GM, McConville J, Korni R, Duecy EE. Outcome of transvaginal radiofrequency for treatment of women with stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(3):263-265.

8. Ismail SI. Radiofrequency remodelling of the endopelvic fascia is not an effective procedure for urodynamic stress incontinence in women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1205-1209.

9. Appell RA, Juma S, Wells WG, et al. Transurethral radio-frequency energy collagen micro-remodeling for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2006;25(4):331-336.

10. Appell RA, Singh G, Klimberg IW, et al. Nonsurgical radiofrequency collagen denaturation for stress urinary incontinence: retrospective 3-year evaluation. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2007;4:455-461.

1. Goldman HB. Is new always better? Curr Urol Rep. 2007;8(4):253-254.

2. Ostergard DR. Lessons from the past: directions for the future. Do new marketed surgical procedures and grafts produce ethical, personal liability, and legal concerns for physicians? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:591-598.

3. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 79: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 Pt 1):461-473.

4. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:717-729.

5. Kassirer JP. On the Take: How Medicine’s Complicity with Big Business Can Endanger Your Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

6. Dmochowski RR, Avon M, Ross J, et al. Transvaginal radiofrequency treatment of the endopelvic fascia: a prospective evaluation for the treatment of genuine stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2003;169:1028-1032.

7. Buchsbaum GM, McConville J, Korni R, Duecy EE. Outcome of transvaginal radiofrequency for treatment of women with stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(3):263-265.

8. Ismail SI. Radiofrequency remodelling of the endopelvic fascia is not an effective procedure for urodynamic stress incontinence in women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1205-1209.

9. Appell RA, Juma S, Wells WG, et al. Transurethral radio-frequency energy collagen micro-remodeling for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2006;25(4):331-336.

10. Appell RA, Singh G, Klimberg IW, et al. Nonsurgical radiofrequency collagen denaturation for stress urinary incontinence: retrospective 3-year evaluation. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2007;4:455-461.

just because they’re new;Anne M. Weber MD;Commentary;economic factors;urinary incontinence;pelvic organ prolapse;POP;transvaginal mesh;urethral sling;UI;innovation in treatment;FDA;medical device;510(k);ProteGen Sling;ObTape;TVT;Gynecare;TVT Secur;early adopters;ACOG;Clinical Practice Bulletin;informed consent;financial conflict of interest;radiofrequency therapy;SURx Transvaginal system;Renessa;do no harm;FDA Alert;

just because they’re new;Anne M. Weber MD;Commentary;economic factors;urinary incontinence;pelvic organ prolapse;POP;transvaginal mesh;urethral sling;UI;innovation in treatment;FDA;medical device;510(k);ProteGen Sling;ObTape;TVT;Gynecare;TVT Secur;early adopters;ACOG;Clinical Practice Bulletin;informed consent;financial conflict of interest;radiofrequency therapy;SURx Transvaginal system;Renessa;do no harm;FDA Alert;

Are new tools for correcting prolapse and incontinence better just because they’re new?

From my vantage point, it appears that economic factors are playing an increasingly important role in how pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and urinary incontinence (UI) are managed—particularly, in regard to the use of surgical devices. As such, the topic of treating POP and UI deserves our attention to ensure that we make the best decisions for our patients.

Now, I’m a staunch supporter of innovation in treatment; certainly, there is room for improvement in current approaches—particularly in surgery—for treating POP and UI. At the same time, I strongly believe that innovation must be demonstrated to be an improvement before it is incorporated into practice. Although innovation is commonly taken on faith, we should know better than to equate “new” with “better” until evidence, gathered through clinical research, has demonstrated this conclusively. A look at the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) process for clearing medical devices for clinical use reveals that such a standard often doesn’t apply—and this should matter to us.

The meaning of 510(k)

Most medical devices are evaluated through an FDA clearance mechanism known as the 510(k) process. This is wholly distinct from the agency’s drug approval process with which most of us are familiar. It’s beyond the scope of this commentary for me to go into detail about 510(k); if you are interested, see two recent commentaries1,2 and visit http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/devadvice/314.html .

In a nutshell, the 510(k) process requires only that an applicant demonstrate that a new medical device has “substantial equivalence” to an already legally marketed device, known as the predicate, which may also have been cleared only through the 510(k) process. That means it’s possible to have generations of products cleared on the basis of one predicate device that was itself never studied adequately.

Indeed, this is the case with most medical devices that have been sold for the surgical treatment of POP and UI—from before the ProteGen Sling (Boston Scientific), through Tension-Free Vaginal Tape (TVT) (Gynecare), and continuing with the newest devices.

The story of the ProteGen Sling ( FIGURE ) offers a cautionary tale about what can go wrong when new devices are cleared by the FDA through 510(k), rather than evaluated through rigorous clinical trials, as drugs are. More recently, experience with the ObTape (Mentor Corporation) followed virtually the same trajectory of events; the product was pulled from the market in 2006 and is now the focus of lawsuits nationwide.

Fortunately, for our patients, experience with TVT (Gynecare) has been favorable. Although TVT was also cleared by the FDA through 510(k), clinical research performed after TVT was introduced has demonstrated its effectiveness and relative safety. Indeed, TVT has revolutionized the treatment of stress UI in women—and, even, our understanding of its etiology.

Several companies are capitalizing on the success of TVT by introducing competing products that are designed to be 1) similar enough to ride on the coattails of TVT yet 2) different enough to capture their own share of market—without evidence of safety or effectiveness required. Even Gynecare (part of Ethicon Women’s Health and Urology, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson) has introduced TVT SECUR to compete with its own TVT—again, without independent evidence of safety or effectiveness.

The current market in devices for stress UI is a moving target that makes it nearly impossible—even for research organizations, such as the federally funded Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, that are independent of industry—to develop and implement sound clinical trials of those devices. Why do I say “moving target”? First, there are no assurances that any device chosen for study will remain the same for the duration of a trial. Second, there is no way to foresee which products will be abandoned over the time required for a large clinical trial.

FIGURE The saga of the ProteGen Sling

Transparency over what might be considered “experimental”

Until the FDA changes its process—to one in which 1) medical devices are adequately assessed before they reach market and 2) postmarketing surveillance is required—it’s our duty to insist on evidence of safety and effectiveness before adopting the latest and greatest products that companies have to offer.

Of all the questions that a patient might ask before treatment, three of the most important, surely, are:

- “Will this help me?”

- “If it helps me, how long will it help?”

- “Whether or not this treatment helps me, what risks—in the short-term and over the long-term—does it present?”

Until we can provide our patients with answers that are supported by evidence, products that lack such evidence should be considered experimental, and patients should be counseled accordingly.

Some patients may accept what they’ve been advised are new and unproven treatments—in the way that some physicians are early adopters. Nevertheless, I am concerned that some clinicians do not appear to appreciate the true lack of evidence that accompanies most marketed devices for prolapse and incontinence. They may mistake the FDA 510(k) process of clearance for something similar to the agency’s extended and complex drug approval process. They may accept claims made in industry-produced white papers that are often largely promotional materials, and fail to look further into those claims.

Now, more than ever and above all else, we must stand between marketing and our patients’ safety. We are familiar with the toll that prolapse and incontinence, as chronic conditions, take on our patients; yet it’s that very chronic nature that should lead us to adopt patience and caution in accepting new treatments before they have been adequately studied.

If we cannot always rely on industry to provide clear information about the risks and benefits of new devices, neither can we routinely look to our professional organizations for unbiased information. Often, professional organizations accept cash contributions from industry, raising the question of conflict of interest that may undermine their actions when the priorities of industry do not align with the goal of safeguarding patients’ well-being.

In an unprecedented example of how a professional association can interfere with its own, expert-authored clinical practice guidelines, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) more than a year ago rescinded one of its published guidelines on POP (Issue 79, February 20073 ) and replaced it with a new guideline (Issue 85, September 20074 ). The new guideline is nearly identical to the prior one—save for one sentence, in which “experimental” is deleted in a discussion of kits of trocar-based synthetic materials sold for the surgical treatment of pelvic organ prolapse (see the EXCERPT ).

The deletion is crucial because offering informed consent for surgery requires a patient to accept risks in balance with an expectation of benefit. A patient cannot be appropriately informed when no evidence of benefit exists and evidence of postoperative risk is extremely limited.

Now, I am not declaring that ACOG acted with bias because of a financial conflict of interest with industry in this instance; the fact that a financial conflict of interest exists for ACOG, however, cannot be disputed if one examines the College’s Annual Report, where contributors are listed. (For a comprehensive, if disillusioning, treatise on the many effects of financial conflict of interest within medicine, I recommend the book On The Take.5 )

Differences between the two bulletins are marked in boldface

Bulletin #79 (original wording): “Given the limited data and frequent changes in the marketed products (particularly with regard to type of mesh material itself, which is most closely associated with several of the postoperative risks especially mesh erosion), if clinicians recommend these procedures before evidence of their risk-benefit is fully understood, the procedures should be considered experimental and patients consented for surgery with that understanding.”

Bulletin #84 (revised wording): “Given the limited data and frequent changes in the marketed products for vaginal surgery for prolapse repair (particularly with regard to type of mesh material itself, which is most closely associated with several of the postoperative risks especially mesh erosion), patients should consent to surgery with an understanding of the post-operative risks and lack of long-term outcomes data.”

Case: Radiofrequency therapy. Even when clinical experience demonstrates lack of effectiveness or an unacceptable rate of complications associated with certain techniques or devices, unequivocal evidence of such problems does not always appear in the literature. One example of this is how a technique was translated into a treatment for incontinence by way of its use in other fields.

Radiofrequency has, among other uses, been used to ablate nerves in intractable chronic pain and to address joint instability in orthopedic surgery. Radiofrequency energy was then, by extension, applied transvaginally to tissue (known as “endopelvic” fascia, of a distinctly different nature than parietal fascia involved in orthopedic procedures) surrounding the urethra. The goal was to coagulate “supporting” tissues and “correct” urethral hypermobility that purportedly causes stress incontinence.

Marketing of the SURx Transvaginal System (CooperSurgical, Inc.) began in 2002, followed by reports of success. One industry-sponsored study, for example, reported a 73% rate of either continence or improvement after 12 months.6

Despite such favorable early results, however, in 2006 CooperSurgical decided to abandon this system, citing “technique-dependent” results of the procedure. Since then, independent research has shown a very low initial success rate that declines rapidly—within weeks or months—of treatment.7,8

A different radiofrequency technique continues to be marketed—the Renessa System™ (NovaSys Medical), which uses a urethral catheter-mounted system to deliver radiofrequency energy through the urethral mucosa to the submucosa and adjacent tissues. Once again, initial reports of industry-sponsored research showed promising results; one study of 110 patients reported 74% achieved continence or improvement after 1 year.9 In a follow-up report of 21 of the original 110 patients, “improvement” was reported in 74% after 3 years.10 Independent research has yet to be reported in the literature.

Of particular concern, no data exist on the long-term effect of denaturing collagen in the urethra and adjacent tissues in relation to UI, other aspects of bladder function, or sexual function. An apparent lack of immediate complications cannot be equated with safety; we need long-term studies to determine whether urethral function is affected adversely compared with that in untreated women and women treated with surgery.

Bring on innovation—in context!

For those who consider my argument anti-innovation, let me repeat: I believe strongly in innovation to improve care for our patients. Am I anti-industry? Only when there is an unbridled race to profit from marketing products without safeguards to ensure, first and foremost, the safety of our patients and, second, their long-term effectiveness. Knowingly or unknowingly, patients then become the guinea pigs on whom these products are tested—just not in the appropriate context of clinical research and informed consent for participation.

Instead (as happened in the US Public Health Service’s Tuskegee syphilis experiments), patients serve as research subjects without their consent when they receive untested products and undergo unproven treatments. And because clinicians are the conduit through which patients receive untested and unproven treatments, who is ultimately responsible for the outcome?

Industry brings innovation to clinical practice. But it is incumbent on clinicians to recognize, with unflinching honesty, the bottom line on which industry operates. Prolapse and incontinence are deeply distressing for our patients, but these chronic conditions are not life-threatening; virtually all women who suffer these conditions have been symptomatic for years before they come for care. I see no need, except to increase that bottom line, to rush products to market before they have been evaluated sufficiently to determine whether “new” is actually “better.”

For clinicians who style themselves as early adopters, remember: It’s not you, but your patient, who is “adopting” a foreign material and having it placed deep in the most intimate area of her body—a foreign material intended to stay for life (except for those unfortunate patients who must have it removed). Above all, we must do no harm—an elusive goal when some of us try to attract patients by being the first to use a product before evidence of its risk and utility have been established in practice.

Does this kind of talk encourage litigation?

Does a commentary like this one provide fodder for plaintiff attorneys who are seeking grounds for product liability lawsuits against manufacturers and malpractice claims against clinicians? Please! Spend a moment on the Web, and you will see that the lawyers are already busy—especially since the FDA’s October 2008 alert about complications with surgical mesh for prolapse and incontinence. [See “FDA alert: Transvaginal placement of surgical mesh carries serious risks,” in the December 2008 issue of OBG Management, at www.obgmanagement.com.] It’s worth noting how these lawyers see themselves: They would likely tell you that they “provide an important service in protecting patients from unscrupulous manufacturers who profit from the vulnerability of people seeking treatment for distressing conditions.” As clinicians, are we absolutely sure that we can say the same of ourselves?

Is it wrong to harp on what happened in the past?

Why revisit events surrounding, for example, the ProteGen Sling? My reply is another question: Where is the evidence that such sequences of events are in the past? Among clinicians, who knows which is best in a collection of kits that changes from one month to the next, without their promoters skipping a beat in proclaiming theirs as the “best”? It isn’t shameful to admit that one doesn’t know which one is best; but it is a shame to act as if one does know, especially when the risk falls to another. The names change; the events are the same.

What is the solution to this problem?

Businesses succeed only when their products are purchased. If clinicians refused to be participants whenever the device industry introduces unproven treatments into the market, industry would be compelled to test their products beforehand. Patients would benefit—by being able to make truly informed choices, with adequate information about risk and benefit. Clinicians would benefit—by being able to provide the most effective treatment without sacrificing their integrity in the process. Ultimately, industry would benefit, by profiting appropriately from products that truly help our patients. Is that an impossible wish?

1. Goldman HB. Is new always better? Curr Urol Rep. 2007;8(4):253-254.

2. Ostergard DR. Lessons from the past: directions for the future. Do new marketed surgical procedures and grafts produce ethical, personal liability, and legal concerns for physicians? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:591-598.

3. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 79: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 Pt 1):461-473.

4. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:717-729.

5. Kassirer JP. On the Take: How Medicine’s Complicity with Big Business Can Endanger Your Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

6. Dmochowski RR, Avon M, Ross J, et al. Transvaginal radiofrequency treatment of the endopelvic fascia: a prospective evaluation for the treatment of genuine stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2003;169:1028-1032.

7. Buchsbaum GM, McConville J, Korni R, Duecy EE. Outcome of transvaginal radiofrequency for treatment of women with stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(3):263-265.

8. Ismail SI. Radiofrequency remodelling of the endopelvic fascia is not an effective procedure for urodynamic stress incontinence in women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1205-1209.

9. Appell RA, Juma S, Wells WG, et al. Transurethral radio-frequency energy collagen micro-remodeling for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2006;25(4):331-336.

10. Appell RA, Singh G, Klimberg IW, et al. Nonsurgical radiofrequency collagen denaturation for stress urinary incontinence: retrospective 3-year evaluation. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2007;4:455-461.

From my vantage point, it appears that economic factors are playing an increasingly important role in how pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and urinary incontinence (UI) are managed—particularly, in regard to the use of surgical devices. As such, the topic of treating POP and UI deserves our attention to ensure that we make the best decisions for our patients.

Now, I’m a staunch supporter of innovation in treatment; certainly, there is room for improvement in current approaches—particularly in surgery—for treating POP and UI. At the same time, I strongly believe that innovation must be demonstrated to be an improvement before it is incorporated into practice. Although innovation is commonly taken on faith, we should know better than to equate “new” with “better” until evidence, gathered through clinical research, has demonstrated this conclusively. A look at the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) process for clearing medical devices for clinical use reveals that such a standard often doesn’t apply—and this should matter to us.

The meaning of 510(k)

Most medical devices are evaluated through an FDA clearance mechanism known as the 510(k) process. This is wholly distinct from the agency’s drug approval process with which most of us are familiar. It’s beyond the scope of this commentary for me to go into detail about 510(k); if you are interested, see two recent commentaries1,2 and visit http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/devadvice/314.html .

In a nutshell, the 510(k) process requires only that an applicant demonstrate that a new medical device has “substantial equivalence” to an already legally marketed device, known as the predicate, which may also have been cleared only through the 510(k) process. That means it’s possible to have generations of products cleared on the basis of one predicate device that was itself never studied adequately.

Indeed, this is the case with most medical devices that have been sold for the surgical treatment of POP and UI—from before the ProteGen Sling (Boston Scientific), through Tension-Free Vaginal Tape (TVT) (Gynecare), and continuing with the newest devices.

The story of the ProteGen Sling ( FIGURE ) offers a cautionary tale about what can go wrong when new devices are cleared by the FDA through 510(k), rather than evaluated through rigorous clinical trials, as drugs are. More recently, experience with the ObTape (Mentor Corporation) followed virtually the same trajectory of events; the product was pulled from the market in 2006 and is now the focus of lawsuits nationwide.

Fortunately, for our patients, experience with TVT (Gynecare) has been favorable. Although TVT was also cleared by the FDA through 510(k), clinical research performed after TVT was introduced has demonstrated its effectiveness and relative safety. Indeed, TVT has revolutionized the treatment of stress UI in women—and, even, our understanding of its etiology.

Several companies are capitalizing on the success of TVT by introducing competing products that are designed to be 1) similar enough to ride on the coattails of TVT yet 2) different enough to capture their own share of market—without evidence of safety or effectiveness required. Even Gynecare (part of Ethicon Women’s Health and Urology, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson) has introduced TVT SECUR to compete with its own TVT—again, without independent evidence of safety or effectiveness.

The current market in devices for stress UI is a moving target that makes it nearly impossible—even for research organizations, such as the federally funded Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, that are independent of industry—to develop and implement sound clinical trials of those devices. Why do I say “moving target”? First, there are no assurances that any device chosen for study will remain the same for the duration of a trial. Second, there is no way to foresee which products will be abandoned over the time required for a large clinical trial.

FIGURE The saga of the ProteGen Sling

Transparency over what might be considered “experimental”

Until the FDA changes its process—to one in which 1) medical devices are adequately assessed before they reach market and 2) postmarketing surveillance is required—it’s our duty to insist on evidence of safety and effectiveness before adopting the latest and greatest products that companies have to offer.

Of all the questions that a patient might ask before treatment, three of the most important, surely, are:

- “Will this help me?”

- “If it helps me, how long will it help?”

- “Whether or not this treatment helps me, what risks—in the short-term and over the long-term—does it present?”

Until we can provide our patients with answers that are supported by evidence, products that lack such evidence should be considered experimental, and patients should be counseled accordingly.

Some patients may accept what they’ve been advised are new and unproven treatments—in the way that some physicians are early adopters. Nevertheless, I am concerned that some clinicians do not appear to appreciate the true lack of evidence that accompanies most marketed devices for prolapse and incontinence. They may mistake the FDA 510(k) process of clearance for something similar to the agency’s extended and complex drug approval process. They may accept claims made in industry-produced white papers that are often largely promotional materials, and fail to look further into those claims.

Now, more than ever and above all else, we must stand between marketing and our patients’ safety. We are familiar with the toll that prolapse and incontinence, as chronic conditions, take on our patients; yet it’s that very chronic nature that should lead us to adopt patience and caution in accepting new treatments before they have been adequately studied.

If we cannot always rely on industry to provide clear information about the risks and benefits of new devices, neither can we routinely look to our professional organizations for unbiased information. Often, professional organizations accept cash contributions from industry, raising the question of conflict of interest that may undermine their actions when the priorities of industry do not align with the goal of safeguarding patients’ well-being.

In an unprecedented example of how a professional association can interfere with its own, expert-authored clinical practice guidelines, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) more than a year ago rescinded one of its published guidelines on POP (Issue 79, February 20073 ) and replaced it with a new guideline (Issue 85, September 20074 ). The new guideline is nearly identical to the prior one—save for one sentence, in which “experimental” is deleted in a discussion of kits of trocar-based synthetic materials sold for the surgical treatment of pelvic organ prolapse (see the EXCERPT ).

The deletion is crucial because offering informed consent for surgery requires a patient to accept risks in balance with an expectation of benefit. A patient cannot be appropriately informed when no evidence of benefit exists and evidence of postoperative risk is extremely limited.

Now, I am not declaring that ACOG acted with bias because of a financial conflict of interest with industry in this instance; the fact that a financial conflict of interest exists for ACOG, however, cannot be disputed if one examines the College’s Annual Report, where contributors are listed. (For a comprehensive, if disillusioning, treatise on the many effects of financial conflict of interest within medicine, I recommend the book On The Take.5 )

Differences between the two bulletins are marked in boldface

Bulletin #79 (original wording): “Given the limited data and frequent changes in the marketed products (particularly with regard to type of mesh material itself, which is most closely associated with several of the postoperative risks especially mesh erosion), if clinicians recommend these procedures before evidence of their risk-benefit is fully understood, the procedures should be considered experimental and patients consented for surgery with that understanding.”

Bulletin #84 (revised wording): “Given the limited data and frequent changes in the marketed products for vaginal surgery for prolapse repair (particularly with regard to type of mesh material itself, which is most closely associated with several of the postoperative risks especially mesh erosion), patients should consent to surgery with an understanding of the post-operative risks and lack of long-term outcomes data.”