User login

New Author Guidelines for Addressing Race and Racism in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

We are committed to using our platform at the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) to address inequities in healthcare delivery, policy, and research. Race was conceived as a mechanism of social division, leading to the false belief, propagated over time, of race as a biological variable.1 As a result, racism has contributed to the medical abuse and exploitation of Black and Brown communities and inequities in health status among racialized groups. We must abandon practices that perpetuate inequities and champion practices that resolve them. Racial health equity—the absence of unjust and avoidable health disparities among racialized groups—is unattainable if we continue to simply identify inequities without naming racism as a determinant of health. As a journal, our responsibility is to disseminate evidence-based manuscripts that reflect an understanding of race, racism, and health.

We have modified our author guidelines. First, we now require authors to clearly define race and provide justification for its inclusion in clinical case descriptions and study analyses. We aim to contribute to the necessary course correction as well as promote self-reflection on study design choices that propagate false notions of race as a biological concept and conclusions that reinforce race-based rather than race-conscious practices in medicine.2 Second, we expect authors to explicitly name racism and make a concerted effort to explore its role, identify its specific forms, and examine mutually reinforcing mechanisms of inequity that potentially contributed to study findings. Finally, we instruct authors to avoid the use of phrases like “patient mistrust,” which places blame for inequities on patients and their families and decouples mistrust from the fraught history of racism in medicine.

We must also acknowledge and reflect on our previous contributions to such inequity as authors, reviewers, and editors in order to learn and grow. Among the more than 2,000 articles published in JHM since its inception, only four included the term “racism.” Three of these articles are perspectives published in June 2020 and beyond. The only original research manuscript that directly addressed racism was a qualitative study of adults with sickle cell disease.3 The authors described study participants’ perspectives: “In contrast, the hospital experience during adulthood was often punctuated by bitter relationships with staff, and distrust over possible excessive use of opioids. Moreover, participants raised the possibility of racism in their interactions with hospital staff.” In this example, patients called out racism and its impact on their experience. We know JHM is not alone in falling woefully short in advancing our understanding of racism and racial health inequities. Each of us should identify missed opportunities to call out racism as a driver of racial health disparities in our own publications. We must act on these lessons regarding the ways in which racism infiltrates scientific publishing. We must use this awareness, along with our influence, voice, and collective power, to enact change for the betterment of our patients, their families, and the medical community.

We at JHM will contribute to uncovering and disseminating solutions to health inequities that result from racism. We are grateful to Boyd et al for their call to action and for providing a blueprint for improvement to those of us who write, review, and publish scholarly work.4

1. Roberts D. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century. 2nd ed. The New Press; 2012.

2. Cerdeña JP, Plaisime MV, Tsai J. From race-based to race-conscious medicine: how anti-racist uprisings call us to act. Lancet. 2020;396:1125-1128. https://doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32076-6

3. Weisberg D, Balf-Soran G, Becker W, et al. “I’m talking about pain”: sickle cell disease patients with extremely high hospital use. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:42-46. https://doi:10.1002/jhm.1987

4. Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog. July 2, 2020. Accessed January 22, 2021. https://doi:10.1377/hblog20200630.939347 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200630.939347/full/

We are committed to using our platform at the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) to address inequities in healthcare delivery, policy, and research. Race was conceived as a mechanism of social division, leading to the false belief, propagated over time, of race as a biological variable.1 As a result, racism has contributed to the medical abuse and exploitation of Black and Brown communities and inequities in health status among racialized groups. We must abandon practices that perpetuate inequities and champion practices that resolve them. Racial health equity—the absence of unjust and avoidable health disparities among racialized groups—is unattainable if we continue to simply identify inequities without naming racism as a determinant of health. As a journal, our responsibility is to disseminate evidence-based manuscripts that reflect an understanding of race, racism, and health.

We have modified our author guidelines. First, we now require authors to clearly define race and provide justification for its inclusion in clinical case descriptions and study analyses. We aim to contribute to the necessary course correction as well as promote self-reflection on study design choices that propagate false notions of race as a biological concept and conclusions that reinforce race-based rather than race-conscious practices in medicine.2 Second, we expect authors to explicitly name racism and make a concerted effort to explore its role, identify its specific forms, and examine mutually reinforcing mechanisms of inequity that potentially contributed to study findings. Finally, we instruct authors to avoid the use of phrases like “patient mistrust,” which places blame for inequities on patients and their families and decouples mistrust from the fraught history of racism in medicine.

We must also acknowledge and reflect on our previous contributions to such inequity as authors, reviewers, and editors in order to learn and grow. Among the more than 2,000 articles published in JHM since its inception, only four included the term “racism.” Three of these articles are perspectives published in June 2020 and beyond. The only original research manuscript that directly addressed racism was a qualitative study of adults with sickle cell disease.3 The authors described study participants’ perspectives: “In contrast, the hospital experience during adulthood was often punctuated by bitter relationships with staff, and distrust over possible excessive use of opioids. Moreover, participants raised the possibility of racism in their interactions with hospital staff.” In this example, patients called out racism and its impact on their experience. We know JHM is not alone in falling woefully short in advancing our understanding of racism and racial health inequities. Each of us should identify missed opportunities to call out racism as a driver of racial health disparities in our own publications. We must act on these lessons regarding the ways in which racism infiltrates scientific publishing. We must use this awareness, along with our influence, voice, and collective power, to enact change for the betterment of our patients, their families, and the medical community.

We at JHM will contribute to uncovering and disseminating solutions to health inequities that result from racism. We are grateful to Boyd et al for their call to action and for providing a blueprint for improvement to those of us who write, review, and publish scholarly work.4

We are committed to using our platform at the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) to address inequities in healthcare delivery, policy, and research. Race was conceived as a mechanism of social division, leading to the false belief, propagated over time, of race as a biological variable.1 As a result, racism has contributed to the medical abuse and exploitation of Black and Brown communities and inequities in health status among racialized groups. We must abandon practices that perpetuate inequities and champion practices that resolve them. Racial health equity—the absence of unjust and avoidable health disparities among racialized groups—is unattainable if we continue to simply identify inequities without naming racism as a determinant of health. As a journal, our responsibility is to disseminate evidence-based manuscripts that reflect an understanding of race, racism, and health.

We have modified our author guidelines. First, we now require authors to clearly define race and provide justification for its inclusion in clinical case descriptions and study analyses. We aim to contribute to the necessary course correction as well as promote self-reflection on study design choices that propagate false notions of race as a biological concept and conclusions that reinforce race-based rather than race-conscious practices in medicine.2 Second, we expect authors to explicitly name racism and make a concerted effort to explore its role, identify its specific forms, and examine mutually reinforcing mechanisms of inequity that potentially contributed to study findings. Finally, we instruct authors to avoid the use of phrases like “patient mistrust,” which places blame for inequities on patients and their families and decouples mistrust from the fraught history of racism in medicine.

We must also acknowledge and reflect on our previous contributions to such inequity as authors, reviewers, and editors in order to learn and grow. Among the more than 2,000 articles published in JHM since its inception, only four included the term “racism.” Three of these articles are perspectives published in June 2020 and beyond. The only original research manuscript that directly addressed racism was a qualitative study of adults with sickle cell disease.3 The authors described study participants’ perspectives: “In contrast, the hospital experience during adulthood was often punctuated by bitter relationships with staff, and distrust over possible excessive use of opioids. Moreover, participants raised the possibility of racism in their interactions with hospital staff.” In this example, patients called out racism and its impact on their experience. We know JHM is not alone in falling woefully short in advancing our understanding of racism and racial health inequities. Each of us should identify missed opportunities to call out racism as a driver of racial health disparities in our own publications. We must act on these lessons regarding the ways in which racism infiltrates scientific publishing. We must use this awareness, along with our influence, voice, and collective power, to enact change for the betterment of our patients, their families, and the medical community.

We at JHM will contribute to uncovering and disseminating solutions to health inequities that result from racism. We are grateful to Boyd et al for their call to action and for providing a blueprint for improvement to those of us who write, review, and publish scholarly work.4

1. Roberts D. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century. 2nd ed. The New Press; 2012.

2. Cerdeña JP, Plaisime MV, Tsai J. From race-based to race-conscious medicine: how anti-racist uprisings call us to act. Lancet. 2020;396:1125-1128. https://doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32076-6

3. Weisberg D, Balf-Soran G, Becker W, et al. “I’m talking about pain”: sickle cell disease patients with extremely high hospital use. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:42-46. https://doi:10.1002/jhm.1987

4. Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog. July 2, 2020. Accessed January 22, 2021. https://doi:10.1377/hblog20200630.939347 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200630.939347/full/

1. Roberts D. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century. 2nd ed. The New Press; 2012.

2. Cerdeña JP, Plaisime MV, Tsai J. From race-based to race-conscious medicine: how anti-racist uprisings call us to act. Lancet. 2020;396:1125-1128. https://doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32076-6

3. Weisberg D, Balf-Soran G, Becker W, et al. “I’m talking about pain”: sickle cell disease patients with extremely high hospital use. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:42-46. https://doi:10.1002/jhm.1987

4. Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog. July 2, 2020. Accessed January 22, 2021. https://doi:10.1377/hblog20200630.939347 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200630.939347/full/

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Clinical Progress Note: Care of Children Hospitalized for Acute Asthma Exacerbation

Since the last National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s (NHLBI) guidelines that were released in 2007, additional evidence has emerged in several areas of asthma care.1 To provide a concise clinical update relevant to the practice of pediatric hospital medicine, we searched PubMed for asthma publications in the last 10 years with a particular focus on articles published in the last 5 years. We used a validated pediatric search filter to identify pediatric studies, MeSH term for “Asthma,” and the following terms: “Clinical Pathways,” “Clinical Protocols,” “Dexamethasone,” and “Albuterol.” From these articles, we identified three areas of emerging evidence supporting practice change relative to the inpatient care of children with asthma, which are summarized in this brief review. This clinical practice update covers the emerging evidence supporting dexamethasone use for acute asthma exacerbations, the shift away from nebulized albuterol toward metered dose inhaler (MDI) albuterol, and the utility of asthma clinical pathways.

DEXAMETHASONE VS PREDNISONE FOR ACUTE ASTHMA EXACERBATIONS

In the last decade, emergency departments (EDs) have increasingly prescribed dexamethasone over prednisone because it is noninferior and has a superior side-effect profile, including less vomiting.2 However, the evidence for dexamethasone use in hospitalized children lagged behind ED practice change. This led to uncertainty among pediatric hospitalists regarding the most appropriate oral steroid to use, particularly for children who received dexamethasone in the ED prior to admission.3

Several studies have been published to address this gap in the literature. In 2015 Parikh et al. published a multicenter retrospective cohort study of dexamethasone vs prednisone among hospitalized children using the Pediatric Health Information Systems (PHIS) database. 4 The authors compared 1,166 patients who received dexamethasone only with a propensity-matched cohort of 1,284 patients receiving only prednisone/prednisolone. Outcomes included the proportion with a length of stay (LOS) greater than 3 days, all-cause readmission at 7 and 30 days, and cost of admission. A greater proportion of patients receiving prednisone/prednisolone had a LOS greater than 3 days when compared with those in the dexamethasone cohort. There were no significant differences in all cause 7- or 30-day readmission. The dexamethasone cohort had statistically significantly lower costs. The authors concluded that dexamethasone may be a viable alternative to prednisone/prednisolone for children admitted for acute asthma exacerbation not requiring admission to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

In 2019, Tyler et al. published a single-center, retrospective, cohort study that used interrupted time series analysis to evaluate outcomes for inpatients with asthma before and after an ED’s protocol was changed to dexamethasone.5 Outcomes analyzed included LOS, hospital charges, and PICU transfer rates. The study included 1,015 subjects over a 36-month period. In the post–protocol change group, 65% of the subjects received dexamethasone only while 28% received a combination of dexamethasone and prednisone/prednisolone. The authors found no immediate significant differences in LOS, ICU transfers, or charges after the protocol change. However, they did see an overall 10% increased rate of PICU transfers in the period following the protocol change, a trend that could have been caused by difficult-to-measure differences in severity of patients before and after the protocol change. If the increase in PICU transfer rate was temporally associated with the ED protocol change, an immediate change in rate would be expected, and this was not seen. The authors speculated that dexamethasone may be inferior to prednisone for inpatients with the highest severity of asthma.

Combined with the practical benefit of dexamethasone’s shorter treatment course and decreased vomiting,2 these two studies support the use of dexamethasone in the inpatient setting for patients who don’t require ICU level care. A feasibility trial to determine noninferiority of dexamethasone vs prednisone is currently enrolling, according to clinicaltrials.gov.

NEBULIZED VS METERED-DOSE INHALER ALBUTEROL FOR ACUTE ASTHMA EXACERBATIONS

The 2007 NHLBI guidelines are clear that short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABA), delivered via nebulization or metered-dose inhaler (MDI) with a valved holding chamber (VHC), along with systemic steroids, should be the primary treatment in pediatric acute asthma exacerbations.1 The guidelines caution that nebulization therapy might be needed for patients who are ineffective in using MDIs because of age, level of agitation, or severity of asthma symptoms. Specific recommendations for management in the inpatient setting are brief but note that inpatient medication administration and care should mirror ED management strategies.1 Specific in-hospital management recommendations regarding nebulization vs MDI are not addressed.

A Cochrane Review by Cates et al. assessed pediatric and adult randomized trials comparing SABA delivery via MDI-VHC with that via nebulization.6 The analysis included 39 trials with a total of 729 adults and 1,897 children. Six of the included trials were conducted in an inpatient setting (207 enrolled children in these studies). The authors found that mechanism of SABA delivery did not affect ED admission rates or significantly influence other markers of treatment response (peak flow and forced expiratory volumes). In children, MDI-VHC use was associated with shorter ED length of stay, as well as a decreased frequency of common SABA side effects (ie, tachycardia and tremor). This review cites several areas in which research is needed, including MDI use in severe asthma exacerbations. This population often falls outside pediatric hospitalists’ scope of practice because these patients often require ICU-level care.

A recent systematic review of pediatric acute asthma management strategies by Castro-Rodriguez et al. found that using MDI-VHC to deliver SABA was superior to using nebulization as measured by decreased ED admission rates and ED length of stay, improved asthma clinical scores, and reduced SABA side effects.7 A 2016 prospective randomized trial of MDI-VHC vs nebulization in preschool-aged children presenting to an ED with asthma or virally mediated wheeze found that the SABA delivered via MDI-VHC was at least as effective as that delivered via nebulization.8

International asthma management guidelines more strongly recommend MDI-only treatment for pediatric patients admitted with moderate asthma.9 Despite this guidance, and the literature supporting transition in inpatient settings to bronchodilator administration via MDI, there are several barriers to exclusive MDI use in the inpatient setting. As mentioned by Cates et al., a recognized challenge in MDI-VHC adoption is overcoming the “nebulizer culture” in treating pediatric acute asthma symptoms.6 Perhaps not surprisingly, Press et al., in a retrospective secondary analysis of 25 institutions managing adults and children with acute asthma symptoms, found that 32% of all pediatric patients assessed received only nebulized SABA treatments during their hospitalization.10 Transitioning from nebulized albuterol to exclusively MDI-VHC albuterol will require significant systems changes.

UTILITY OF CLINICAL PATHWAYS

Clinical pathways operationalize practice guidelines and provide guidance on the treatments, testing, and management of an illness. Use of pediatric asthma pathways has increased steadily in the past decade, with one study of over 300 hospitals finding that, between 2005 to 2015, pathway implementation increased from 27% to 86%.11 This expanded use has coincided with a proliferation of publications evaluating the effects of these pathways. A systematic review examining the implementation and impact of asthma protocols identified over 100 articles published between 1986 and 2010, with the majority published after 2005.12 The study found implementation of guidelines through an asthma pathway generally improved patient care and provider performance regardless of implementation method.

Since that review, Kaiser et al. investigated the effects of pathway implementation at 42 children’s hospitals.13 They used interrupted time series to determine the effect of pathway implementation on LOS. Secondary outcomes included cost, use of bronchodilators, antibiotic use, and 30-day readmissions. This study found pathway implementation was associated with an 8.8% decrease in LOS and 3% decrease in hospital costs while increasing bronchodilator administration and decreasing antibiotic exposure. To determine the factors that allowed successful implementation of asthma pathways (as determined by reduction in LOS), Kaiser et al. performed qualitative interviews of key stakeholders at high- and low-performing hospitals.14 The most successful hospitals all used rigorous data-driven quality-improvement methodologies, set shared goals with key stakeholders, integrated the pathway into their electronic medical record, allowed nurses and respiratory therapists to titrate albuterol frequency, and engaged hospital leadership to secure needed resources.

Although in each of these studies, pathway implementation led to improvements in the acute management of patients, there was no reduction in pediatric asthma readmissions at 30 days.12,13 A meta-analysis of asthma-related quality improvement interventions also did not find an association between pathway implementation alone and decreased readmissions or ED revisits.15 The lack of improvement in these metrics may have been caused by the tendency for pathways to focus on the acute asthma management and lack of focus on chronic asthma severity. Asthma admissions are an opportunity for full evaluation of disease severity, allergen exposures, and education on medication and spacer technique. Refinement of pathways with a focus on chronic control and on transition from hospital to home may move the needle on decreasing the long-term morbidity of pediatric asthma.

CONCLUSION

Current evidence suggests pediatric hospitalists should consider transitioning from prednisolone/prednisone to dexamethasone and from nebulized albuterol delivery to MDI albuterol delivery for children admitted for acute asthma exacerbation who do not require ICU-level care. Implementing asthma clinical pathways that use rigorous quality improvement methods is an effective approach to adopt these and other evidence-based practice changes.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. National Asthma E, Prevention P. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma–Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5 Suppl):S94-S138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.029.

2. Keeney GE, Gray MP, Morrison AK, et al. Dexamethasone for acute asthma exacerbations in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):493-499. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2273.

3. Cotter JM, Tyler A, Reese J, et al. Steroid variability in pediatric inpatient asthmatics: Survey on provider preferences of dexamethasone versus prednisone. J Asthma. 2019:1-7. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2019.1622713.

4. Parikh K, Hall M, Mittal V, et al. Comparative effectiveness of dexamethasone versus prednisone in children hospitalized with asthma. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):639-644.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.06.038.

5. Tyler A, Cotter JM, Moss A, et al. Outcomes for pediatric asthmatic inpatients after implementation of an emergency department dexamethasone treatment protocol. Hosp Pediatr. 2019;9(2):92-99. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2018-0099.

6. Cates CJ, Welsh EJ, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulisers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(9):CD000052. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000052.pub3.

7. Castro-Rodriguez JA, J Rodrigo G, E Rodriguea-Martinez C. Principal findings of systematic reviews of acute asthma treatment in childhood. J Asthma. 2015;52(10):1038-1045. https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2015.1033725.

8. Mitselou N, Hedlin G, Hederos CA. Spacers versus nebulizers in treatment of acute asthma - a prospective randomized study in preschool children. J Asthma. 2016;53(10):1059-1062. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2016.1185114.

9. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. https://www.ginasthma.org. Accessed December 10, 2019.

10. Press VG, Hasegawa K, Heidt J, Bittner JC, Camargo CA Jr. Missed opportunities to transition from nebulizers to inhalers during hospitalization for acute asthma: A multicenter observational study. J Asthma. 2017;54(9):968-976. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2017.

11. Kaiser SV, Rodean J, Bekmezian A, et al. Rising utilization of inpatient pediatric asthma pathways. J Asthma. 2018;55(2):196-207. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/02770903.2017.1316392.

12. Dexheimer JW, Borycki EM, Chiu KW, Johnson KB, Aronsky D. A systematic review of the implementation and impact of asthma protocols. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:82. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-14-82.

13. Kaiser SV, Rodean J, Bekmezian A, et al. effectiveness of pediatric asthma pathways for hospitalized children: A multicenter, national analysis. J Pediatr. 2018;197:165-171.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.01.084.

14. Kaiser SV, Lam R, Cabana MD, et al. Best practices in implementing inpatient pediatric asthma pathways: a qualitative study. J Asthma. 2019:1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2019.1606237.

15. Parikh K, Keller S, Ralston S. Inpatient quality improvement interventions for asthma: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3334.

Since the last National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s (NHLBI) guidelines that were released in 2007, additional evidence has emerged in several areas of asthma care.1 To provide a concise clinical update relevant to the practice of pediatric hospital medicine, we searched PubMed for asthma publications in the last 10 years with a particular focus on articles published in the last 5 years. We used a validated pediatric search filter to identify pediatric studies, MeSH term for “Asthma,” and the following terms: “Clinical Pathways,” “Clinical Protocols,” “Dexamethasone,” and “Albuterol.” From these articles, we identified three areas of emerging evidence supporting practice change relative to the inpatient care of children with asthma, which are summarized in this brief review. This clinical practice update covers the emerging evidence supporting dexamethasone use for acute asthma exacerbations, the shift away from nebulized albuterol toward metered dose inhaler (MDI) albuterol, and the utility of asthma clinical pathways.

DEXAMETHASONE VS PREDNISONE FOR ACUTE ASTHMA EXACERBATIONS

In the last decade, emergency departments (EDs) have increasingly prescribed dexamethasone over prednisone because it is noninferior and has a superior side-effect profile, including less vomiting.2 However, the evidence for dexamethasone use in hospitalized children lagged behind ED practice change. This led to uncertainty among pediatric hospitalists regarding the most appropriate oral steroid to use, particularly for children who received dexamethasone in the ED prior to admission.3

Several studies have been published to address this gap in the literature. In 2015 Parikh et al. published a multicenter retrospective cohort study of dexamethasone vs prednisone among hospitalized children using the Pediatric Health Information Systems (PHIS) database. 4 The authors compared 1,166 patients who received dexamethasone only with a propensity-matched cohort of 1,284 patients receiving only prednisone/prednisolone. Outcomes included the proportion with a length of stay (LOS) greater than 3 days, all-cause readmission at 7 and 30 days, and cost of admission. A greater proportion of patients receiving prednisone/prednisolone had a LOS greater than 3 days when compared with those in the dexamethasone cohort. There were no significant differences in all cause 7- or 30-day readmission. The dexamethasone cohort had statistically significantly lower costs. The authors concluded that dexamethasone may be a viable alternative to prednisone/prednisolone for children admitted for acute asthma exacerbation not requiring admission to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

In 2019, Tyler et al. published a single-center, retrospective, cohort study that used interrupted time series analysis to evaluate outcomes for inpatients with asthma before and after an ED’s protocol was changed to dexamethasone.5 Outcomes analyzed included LOS, hospital charges, and PICU transfer rates. The study included 1,015 subjects over a 36-month period. In the post–protocol change group, 65% of the subjects received dexamethasone only while 28% received a combination of dexamethasone and prednisone/prednisolone. The authors found no immediate significant differences in LOS, ICU transfers, or charges after the protocol change. However, they did see an overall 10% increased rate of PICU transfers in the period following the protocol change, a trend that could have been caused by difficult-to-measure differences in severity of patients before and after the protocol change. If the increase in PICU transfer rate was temporally associated with the ED protocol change, an immediate change in rate would be expected, and this was not seen. The authors speculated that dexamethasone may be inferior to prednisone for inpatients with the highest severity of asthma.

Combined with the practical benefit of dexamethasone’s shorter treatment course and decreased vomiting,2 these two studies support the use of dexamethasone in the inpatient setting for patients who don’t require ICU level care. A feasibility trial to determine noninferiority of dexamethasone vs prednisone is currently enrolling, according to clinicaltrials.gov.

NEBULIZED VS METERED-DOSE INHALER ALBUTEROL FOR ACUTE ASTHMA EXACERBATIONS

The 2007 NHLBI guidelines are clear that short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABA), delivered via nebulization or metered-dose inhaler (MDI) with a valved holding chamber (VHC), along with systemic steroids, should be the primary treatment in pediatric acute asthma exacerbations.1 The guidelines caution that nebulization therapy might be needed for patients who are ineffective in using MDIs because of age, level of agitation, or severity of asthma symptoms. Specific recommendations for management in the inpatient setting are brief but note that inpatient medication administration and care should mirror ED management strategies.1 Specific in-hospital management recommendations regarding nebulization vs MDI are not addressed.

A Cochrane Review by Cates et al. assessed pediatric and adult randomized trials comparing SABA delivery via MDI-VHC with that via nebulization.6 The analysis included 39 trials with a total of 729 adults and 1,897 children. Six of the included trials were conducted in an inpatient setting (207 enrolled children in these studies). The authors found that mechanism of SABA delivery did not affect ED admission rates or significantly influence other markers of treatment response (peak flow and forced expiratory volumes). In children, MDI-VHC use was associated with shorter ED length of stay, as well as a decreased frequency of common SABA side effects (ie, tachycardia and tremor). This review cites several areas in which research is needed, including MDI use in severe asthma exacerbations. This population often falls outside pediatric hospitalists’ scope of practice because these patients often require ICU-level care.

A recent systematic review of pediatric acute asthma management strategies by Castro-Rodriguez et al. found that using MDI-VHC to deliver SABA was superior to using nebulization as measured by decreased ED admission rates and ED length of stay, improved asthma clinical scores, and reduced SABA side effects.7 A 2016 prospective randomized trial of MDI-VHC vs nebulization in preschool-aged children presenting to an ED with asthma or virally mediated wheeze found that the SABA delivered via MDI-VHC was at least as effective as that delivered via nebulization.8

International asthma management guidelines more strongly recommend MDI-only treatment for pediatric patients admitted with moderate asthma.9 Despite this guidance, and the literature supporting transition in inpatient settings to bronchodilator administration via MDI, there are several barriers to exclusive MDI use in the inpatient setting. As mentioned by Cates et al., a recognized challenge in MDI-VHC adoption is overcoming the “nebulizer culture” in treating pediatric acute asthma symptoms.6 Perhaps not surprisingly, Press et al., in a retrospective secondary analysis of 25 institutions managing adults and children with acute asthma symptoms, found that 32% of all pediatric patients assessed received only nebulized SABA treatments during their hospitalization.10 Transitioning from nebulized albuterol to exclusively MDI-VHC albuterol will require significant systems changes.

UTILITY OF CLINICAL PATHWAYS

Clinical pathways operationalize practice guidelines and provide guidance on the treatments, testing, and management of an illness. Use of pediatric asthma pathways has increased steadily in the past decade, with one study of over 300 hospitals finding that, between 2005 to 2015, pathway implementation increased from 27% to 86%.11 This expanded use has coincided with a proliferation of publications evaluating the effects of these pathways. A systematic review examining the implementation and impact of asthma protocols identified over 100 articles published between 1986 and 2010, with the majority published after 2005.12 The study found implementation of guidelines through an asthma pathway generally improved patient care and provider performance regardless of implementation method.

Since that review, Kaiser et al. investigated the effects of pathway implementation at 42 children’s hospitals.13 They used interrupted time series to determine the effect of pathway implementation on LOS. Secondary outcomes included cost, use of bronchodilators, antibiotic use, and 30-day readmissions. This study found pathway implementation was associated with an 8.8% decrease in LOS and 3% decrease in hospital costs while increasing bronchodilator administration and decreasing antibiotic exposure. To determine the factors that allowed successful implementation of asthma pathways (as determined by reduction in LOS), Kaiser et al. performed qualitative interviews of key stakeholders at high- and low-performing hospitals.14 The most successful hospitals all used rigorous data-driven quality-improvement methodologies, set shared goals with key stakeholders, integrated the pathway into their electronic medical record, allowed nurses and respiratory therapists to titrate albuterol frequency, and engaged hospital leadership to secure needed resources.

Although in each of these studies, pathway implementation led to improvements in the acute management of patients, there was no reduction in pediatric asthma readmissions at 30 days.12,13 A meta-analysis of asthma-related quality improvement interventions also did not find an association between pathway implementation alone and decreased readmissions or ED revisits.15 The lack of improvement in these metrics may have been caused by the tendency for pathways to focus on the acute asthma management and lack of focus on chronic asthma severity. Asthma admissions are an opportunity for full evaluation of disease severity, allergen exposures, and education on medication and spacer technique. Refinement of pathways with a focus on chronic control and on transition from hospital to home may move the needle on decreasing the long-term morbidity of pediatric asthma.

CONCLUSION

Current evidence suggests pediatric hospitalists should consider transitioning from prednisolone/prednisone to dexamethasone and from nebulized albuterol delivery to MDI albuterol delivery for children admitted for acute asthma exacerbation who do not require ICU-level care. Implementing asthma clinical pathways that use rigorous quality improvement methods is an effective approach to adopt these and other evidence-based practice changes.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Since the last National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s (NHLBI) guidelines that were released in 2007, additional evidence has emerged in several areas of asthma care.1 To provide a concise clinical update relevant to the practice of pediatric hospital medicine, we searched PubMed for asthma publications in the last 10 years with a particular focus on articles published in the last 5 years. We used a validated pediatric search filter to identify pediatric studies, MeSH term for “Asthma,” and the following terms: “Clinical Pathways,” “Clinical Protocols,” “Dexamethasone,” and “Albuterol.” From these articles, we identified three areas of emerging evidence supporting practice change relative to the inpatient care of children with asthma, which are summarized in this brief review. This clinical practice update covers the emerging evidence supporting dexamethasone use for acute asthma exacerbations, the shift away from nebulized albuterol toward metered dose inhaler (MDI) albuterol, and the utility of asthma clinical pathways.

DEXAMETHASONE VS PREDNISONE FOR ACUTE ASTHMA EXACERBATIONS

In the last decade, emergency departments (EDs) have increasingly prescribed dexamethasone over prednisone because it is noninferior and has a superior side-effect profile, including less vomiting.2 However, the evidence for dexamethasone use in hospitalized children lagged behind ED practice change. This led to uncertainty among pediatric hospitalists regarding the most appropriate oral steroid to use, particularly for children who received dexamethasone in the ED prior to admission.3

Several studies have been published to address this gap in the literature. In 2015 Parikh et al. published a multicenter retrospective cohort study of dexamethasone vs prednisone among hospitalized children using the Pediatric Health Information Systems (PHIS) database. 4 The authors compared 1,166 patients who received dexamethasone only with a propensity-matched cohort of 1,284 patients receiving only prednisone/prednisolone. Outcomes included the proportion with a length of stay (LOS) greater than 3 days, all-cause readmission at 7 and 30 days, and cost of admission. A greater proportion of patients receiving prednisone/prednisolone had a LOS greater than 3 days when compared with those in the dexamethasone cohort. There were no significant differences in all cause 7- or 30-day readmission. The dexamethasone cohort had statistically significantly lower costs. The authors concluded that dexamethasone may be a viable alternative to prednisone/prednisolone for children admitted for acute asthma exacerbation not requiring admission to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

In 2019, Tyler et al. published a single-center, retrospective, cohort study that used interrupted time series analysis to evaluate outcomes for inpatients with asthma before and after an ED’s protocol was changed to dexamethasone.5 Outcomes analyzed included LOS, hospital charges, and PICU transfer rates. The study included 1,015 subjects over a 36-month period. In the post–protocol change group, 65% of the subjects received dexamethasone only while 28% received a combination of dexamethasone and prednisone/prednisolone. The authors found no immediate significant differences in LOS, ICU transfers, or charges after the protocol change. However, they did see an overall 10% increased rate of PICU transfers in the period following the protocol change, a trend that could have been caused by difficult-to-measure differences in severity of patients before and after the protocol change. If the increase in PICU transfer rate was temporally associated with the ED protocol change, an immediate change in rate would be expected, and this was not seen. The authors speculated that dexamethasone may be inferior to prednisone for inpatients with the highest severity of asthma.

Combined with the practical benefit of dexamethasone’s shorter treatment course and decreased vomiting,2 these two studies support the use of dexamethasone in the inpatient setting for patients who don’t require ICU level care. A feasibility trial to determine noninferiority of dexamethasone vs prednisone is currently enrolling, according to clinicaltrials.gov.

NEBULIZED VS METERED-DOSE INHALER ALBUTEROL FOR ACUTE ASTHMA EXACERBATIONS

The 2007 NHLBI guidelines are clear that short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABA), delivered via nebulization or metered-dose inhaler (MDI) with a valved holding chamber (VHC), along with systemic steroids, should be the primary treatment in pediatric acute asthma exacerbations.1 The guidelines caution that nebulization therapy might be needed for patients who are ineffective in using MDIs because of age, level of agitation, or severity of asthma symptoms. Specific recommendations for management in the inpatient setting are brief but note that inpatient medication administration and care should mirror ED management strategies.1 Specific in-hospital management recommendations regarding nebulization vs MDI are not addressed.

A Cochrane Review by Cates et al. assessed pediatric and adult randomized trials comparing SABA delivery via MDI-VHC with that via nebulization.6 The analysis included 39 trials with a total of 729 adults and 1,897 children. Six of the included trials were conducted in an inpatient setting (207 enrolled children in these studies). The authors found that mechanism of SABA delivery did not affect ED admission rates or significantly influence other markers of treatment response (peak flow and forced expiratory volumes). In children, MDI-VHC use was associated with shorter ED length of stay, as well as a decreased frequency of common SABA side effects (ie, tachycardia and tremor). This review cites several areas in which research is needed, including MDI use in severe asthma exacerbations. This population often falls outside pediatric hospitalists’ scope of practice because these patients often require ICU-level care.

A recent systematic review of pediatric acute asthma management strategies by Castro-Rodriguez et al. found that using MDI-VHC to deliver SABA was superior to using nebulization as measured by decreased ED admission rates and ED length of stay, improved asthma clinical scores, and reduced SABA side effects.7 A 2016 prospective randomized trial of MDI-VHC vs nebulization in preschool-aged children presenting to an ED with asthma or virally mediated wheeze found that the SABA delivered via MDI-VHC was at least as effective as that delivered via nebulization.8

International asthma management guidelines more strongly recommend MDI-only treatment for pediatric patients admitted with moderate asthma.9 Despite this guidance, and the literature supporting transition in inpatient settings to bronchodilator administration via MDI, there are several barriers to exclusive MDI use in the inpatient setting. As mentioned by Cates et al., a recognized challenge in MDI-VHC adoption is overcoming the “nebulizer culture” in treating pediatric acute asthma symptoms.6 Perhaps not surprisingly, Press et al., in a retrospective secondary analysis of 25 institutions managing adults and children with acute asthma symptoms, found that 32% of all pediatric patients assessed received only nebulized SABA treatments during their hospitalization.10 Transitioning from nebulized albuterol to exclusively MDI-VHC albuterol will require significant systems changes.

UTILITY OF CLINICAL PATHWAYS

Clinical pathways operationalize practice guidelines and provide guidance on the treatments, testing, and management of an illness. Use of pediatric asthma pathways has increased steadily in the past decade, with one study of over 300 hospitals finding that, between 2005 to 2015, pathway implementation increased from 27% to 86%.11 This expanded use has coincided with a proliferation of publications evaluating the effects of these pathways. A systematic review examining the implementation and impact of asthma protocols identified over 100 articles published between 1986 and 2010, with the majority published after 2005.12 The study found implementation of guidelines through an asthma pathway generally improved patient care and provider performance regardless of implementation method.

Since that review, Kaiser et al. investigated the effects of pathway implementation at 42 children’s hospitals.13 They used interrupted time series to determine the effect of pathway implementation on LOS. Secondary outcomes included cost, use of bronchodilators, antibiotic use, and 30-day readmissions. This study found pathway implementation was associated with an 8.8% decrease in LOS and 3% decrease in hospital costs while increasing bronchodilator administration and decreasing antibiotic exposure. To determine the factors that allowed successful implementation of asthma pathways (as determined by reduction in LOS), Kaiser et al. performed qualitative interviews of key stakeholders at high- and low-performing hospitals.14 The most successful hospitals all used rigorous data-driven quality-improvement methodologies, set shared goals with key stakeholders, integrated the pathway into their electronic medical record, allowed nurses and respiratory therapists to titrate albuterol frequency, and engaged hospital leadership to secure needed resources.

Although in each of these studies, pathway implementation led to improvements in the acute management of patients, there was no reduction in pediatric asthma readmissions at 30 days.12,13 A meta-analysis of asthma-related quality improvement interventions also did not find an association between pathway implementation alone and decreased readmissions or ED revisits.15 The lack of improvement in these metrics may have been caused by the tendency for pathways to focus on the acute asthma management and lack of focus on chronic asthma severity. Asthma admissions are an opportunity for full evaluation of disease severity, allergen exposures, and education on medication and spacer technique. Refinement of pathways with a focus on chronic control and on transition from hospital to home may move the needle on decreasing the long-term morbidity of pediatric asthma.

CONCLUSION

Current evidence suggests pediatric hospitalists should consider transitioning from prednisolone/prednisone to dexamethasone and from nebulized albuterol delivery to MDI albuterol delivery for children admitted for acute asthma exacerbation who do not require ICU-level care. Implementing asthma clinical pathways that use rigorous quality improvement methods is an effective approach to adopt these and other evidence-based practice changes.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. National Asthma E, Prevention P. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma–Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5 Suppl):S94-S138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.029.

2. Keeney GE, Gray MP, Morrison AK, et al. Dexamethasone for acute asthma exacerbations in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):493-499. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2273.

3. Cotter JM, Tyler A, Reese J, et al. Steroid variability in pediatric inpatient asthmatics: Survey on provider preferences of dexamethasone versus prednisone. J Asthma. 2019:1-7. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2019.1622713.

4. Parikh K, Hall M, Mittal V, et al. Comparative effectiveness of dexamethasone versus prednisone in children hospitalized with asthma. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):639-644.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.06.038.

5. Tyler A, Cotter JM, Moss A, et al. Outcomes for pediatric asthmatic inpatients after implementation of an emergency department dexamethasone treatment protocol. Hosp Pediatr. 2019;9(2):92-99. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2018-0099.

6. Cates CJ, Welsh EJ, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulisers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(9):CD000052. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000052.pub3.

7. Castro-Rodriguez JA, J Rodrigo G, E Rodriguea-Martinez C. Principal findings of systematic reviews of acute asthma treatment in childhood. J Asthma. 2015;52(10):1038-1045. https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2015.1033725.

8. Mitselou N, Hedlin G, Hederos CA. Spacers versus nebulizers in treatment of acute asthma - a prospective randomized study in preschool children. J Asthma. 2016;53(10):1059-1062. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2016.1185114.

9. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. https://www.ginasthma.org. Accessed December 10, 2019.

10. Press VG, Hasegawa K, Heidt J, Bittner JC, Camargo CA Jr. Missed opportunities to transition from nebulizers to inhalers during hospitalization for acute asthma: A multicenter observational study. J Asthma. 2017;54(9):968-976. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2017.

11. Kaiser SV, Rodean J, Bekmezian A, et al. Rising utilization of inpatient pediatric asthma pathways. J Asthma. 2018;55(2):196-207. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/02770903.2017.1316392.

12. Dexheimer JW, Borycki EM, Chiu KW, Johnson KB, Aronsky D. A systematic review of the implementation and impact of asthma protocols. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:82. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-14-82.

13. Kaiser SV, Rodean J, Bekmezian A, et al. effectiveness of pediatric asthma pathways for hospitalized children: A multicenter, national analysis. J Pediatr. 2018;197:165-171.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.01.084.

14. Kaiser SV, Lam R, Cabana MD, et al. Best practices in implementing inpatient pediatric asthma pathways: a qualitative study. J Asthma. 2019:1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2019.1606237.

15. Parikh K, Keller S, Ralston S. Inpatient quality improvement interventions for asthma: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3334.

1. National Asthma E, Prevention P. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma–Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5 Suppl):S94-S138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.029.

2. Keeney GE, Gray MP, Morrison AK, et al. Dexamethasone for acute asthma exacerbations in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):493-499. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2273.

3. Cotter JM, Tyler A, Reese J, et al. Steroid variability in pediatric inpatient asthmatics: Survey on provider preferences of dexamethasone versus prednisone. J Asthma. 2019:1-7. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2019.1622713.

4. Parikh K, Hall M, Mittal V, et al. Comparative effectiveness of dexamethasone versus prednisone in children hospitalized with asthma. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):639-644.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.06.038.

5. Tyler A, Cotter JM, Moss A, et al. Outcomes for pediatric asthmatic inpatients after implementation of an emergency department dexamethasone treatment protocol. Hosp Pediatr. 2019;9(2):92-99. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2018-0099.

6. Cates CJ, Welsh EJ, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulisers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(9):CD000052. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000052.pub3.

7. Castro-Rodriguez JA, J Rodrigo G, E Rodriguea-Martinez C. Principal findings of systematic reviews of acute asthma treatment in childhood. J Asthma. 2015;52(10):1038-1045. https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2015.1033725.

8. Mitselou N, Hedlin G, Hederos CA. Spacers versus nebulizers in treatment of acute asthma - a prospective randomized study in preschool children. J Asthma. 2016;53(10):1059-1062. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2016.1185114.

9. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. https://www.ginasthma.org. Accessed December 10, 2019.

10. Press VG, Hasegawa K, Heidt J, Bittner JC, Camargo CA Jr. Missed opportunities to transition from nebulizers to inhalers during hospitalization for acute asthma: A multicenter observational study. J Asthma. 2017;54(9):968-976. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2017.

11. Kaiser SV, Rodean J, Bekmezian A, et al. Rising utilization of inpatient pediatric asthma pathways. J Asthma. 2018;55(2):196-207. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/02770903.2017.1316392.

12. Dexheimer JW, Borycki EM, Chiu KW, Johnson KB, Aronsky D. A systematic review of the implementation and impact of asthma protocols. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:82. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-14-82.

13. Kaiser SV, Rodean J, Bekmezian A, et al. effectiveness of pediatric asthma pathways for hospitalized children: A multicenter, national analysis. J Pediatr. 2018;197:165-171.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.01.084.

14. Kaiser SV, Lam R, Cabana MD, et al. Best practices in implementing inpatient pediatric asthma pathways: a qualitative study. J Asthma. 2019:1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2019.1606237.

15. Parikh K, Keller S, Ralston S. Inpatient quality improvement interventions for asthma: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3334.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Turning Your Passion into Action: Becoming a Physician Advocate

I stand in the hospital room of a little girl who was shot in her own home just two weeks ago. She was drawing in her sketchbook when a group of teenagers drove by her apartment and took aim. She was shot twice in the chest. Her life and her health will forever be altered. I am not part of her care team, but I am there because just hours after their arrival to the hospital her mother declared that she was going to do something, that gun violence must be stopped. She wants to speak out and she wants to give her daughter a voice. She does not want this to happen to other little girls. My colleagues know that I can help this woman by elevating her voice, by telling her daughter’s story. I have found a passion in gun violence prevention advocacy and I fight every day for little girls like this.

For almost 10 years, I studied asthma. I presented lectures. I conducted research. I published papers. It was my thing. In fact, it still is my thing. But one day shortly after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, I was dropping my oldest daughter off at Kindergarten and for the first time, I saw an armed police officer patrolling the drop-off line. It hit me like a ton of bricks. I went home and called my Senators and Representatives. As I was talking to an aide about evidence-based gun safety legislation, I lost it. I started crying. I finished the call and just sat there. I was momentarily frozen, uncertain of what to do next yet compelled to take action. I decided to attend a meeting of a local gun violence prevention group. Maybe this action of going to one meeting would quell the anxiety and fear that was building inside of me. I found my local Moms Demand Action chapter and I went. About halfway through the meeting, the chapter leader began describing their gun safety campaign, Be SMART for kids, and mentioned that they had been trying to make connections with the Children’s Hospital. That is the moment. That is when it clicked. I have a voice that this movement needs. I can help them. And I did.

Gun violence is the second leading cause of death in children.1 Gun violence is a public health epidemic. Every day in America, approximately 100 people are shot and killed.2 The rate of firearm deaths among children and teens in the United States is 36.5 times higher than that of 12 other high-income countries.1 We know that states with stricter gun laws have lower rates of child firearm mortality.3 We also know that safe gun storage practices (storing guns locked, unloaded, and separate from ammunition) reduce the risk of suicide and firearm injuries,4 yet 4.6 million American children live in a home with a loaded, unlocked firearm.5 Promoting safe gun storage practices and advocating for common sense gun safety legislation are two effective ways to address this crisis.

Gun violence prevention is my passion, but it might not be yours. Regardless of your passion, the blueprint for becoming a physician advocate is the same.

WHY DO PHYSICIANS MAKE NATURAL, EFFECTIVE ADVOCATES?

Advocacy, in its most distilled form, is speaking out for something you believe in, often for someone who cannot speak out for themselves. This is at the core of what we, as healthcare providers, do every day. We help people through some of the hardest moments of their lives, when they are sick and vulnerable. Every day, we are faced with problems that need to be solved. Our experience at the bedside helps us understand how policies affect real people. We understand evidence, data, and science. We recognize that anecdotes are powerful but if not backed up with data will be unlikely to lead to meaningful change. Perhaps most importantly, as professional members of the community, we have agency. We can use our voice and our privilege as physicians to elevate the voices of others.

As you go through medical training, you may not even realize that what you are doing on a daily basis is advocacy. But there comes a moment when you realize that the problem is bigger than the individual patient in front of you. There are systems that are broken that, if fixed, could improve the health of patients everywhere and save lives. To create change on a population level, the status quo will need to be challenged and systems may need to be disrupted.

Hospitalists are particularly well positioned to be advocates because we interact with virtually all aspects of the healthcare system either directly or indirectly. We care for patients with a myriad of disease processes and medical needs using varying levels of resources and social support systems. We often see patients in their most dire moments and, unlike outpatient physicians, we have the luxury of time. Hospitalized patients are a captive audience. We have time to educate, assess what patients need, and connect patients with community resources.

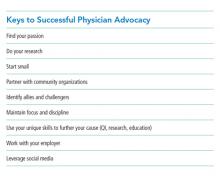

HOW TO BECOME A PHYSICIAN ADVOCATE

Find your passion. Often, your passion will find you. When it does, listen to it. Initially, most of your advocacy will be done on your own time. If you are not passionate about your cause, you will struggle and you will be less likely to be an effective advocate. Keep in mind that sometimes the deeper you dig into an issue, the bigger problems you find and, as a result, your passion can grow.

Do your research. Read the literature. Do you really understand the issue? Identify local and national experts, read their work, and follow their careers. You do not need an advanced degree. Your experience as a physician, willingness to learn, and your voice are all you need.

Start small. Do something small every day. Read an article. Make a new contact. Talk to a colleague. Be thoughtful in your approach. Is this a problem that community advocacy can solve? Will legislation be an effective way to achieve my goal? Would state or federal legislation be more appropriate? In most cases, a combination of community advocacy and legislative advocacy is necessary.

Partner with community organizations. Find local organizations that have existing infrastructure and are engaged on the issue and create partnerships. Community organizations are fighting every day and are waiting for a powerful authoritative voice like yours. They want your voice and you need their support.

Find your allies and your challengers. Identify allies in your community, your institution, your field, and in government. Anticipate potential challengers. When you encounter them, work diligently to find common ground and be respectful. If you only talk to people who agree with you, you will not make progress. Tread carefully when necessary. Develop a thick skin. Read people and try to figure out what it is that they want, what is motivating their position. Make your first ask small and as noncontroversial as possible. Stick to the facts. If you keep your patients at the heart of what you are doing, it is hard to go wrong.

Stay focused and disciplined, but do not quiet the anger and frustration that you feel. That is your fuel. Build momentum and build your team. Passion is contagious; when people see that you are making progress, they will want to join you. Together, you can create a dialog that will change minds.

Align advocacy with your other work. Ideally, this work will not be done in isolation from your other professional duties. Advocacy initiatives make excellent quality improvement projects. When you identify holes in the evidence that could potentially inform the policy debate, apply health services research methods and publish. This approach builds the evidence base to affect change and contributes to your professional development. Consider developing an advocacy curriculum for trainees. Identify trainees interested in advocacy and mentor them. Look for opportunities to speak and write on the topic. Use your unique skillset to further your cause.

Work with your employer. Find common ground. Even if they fundamentally disagree with your point of view, you can still speak out as a private citizen. Recognize the difference between speaking as a physician and speaking as an employee of a specific institution. Unless you have explicit permission, you are speaking for yourself, not your institution. Do not be afraid to push leaders at your institution. Help them see why it is important for you to speak up on a particular issue. If your professional organization has a statement on the issue, use it to support your position.

Leverage social media. Social media is a powerful method to amplify your voice. Consider the impact of the #thisisourlane movement. It will connect you with people, across the world, who share similar passions. It will help you identify local allies. It will open opportunities for speaking engagements and publications. It can be a great way to bring positive attention to your institution. It will take time to find your voice. Try to use consistent messaging. Keep it professional. Tag people who you want to see the great work you are doing. It only takes one retweet by someone with hundreds of thousands of followers to get your message in the feed of exponentially more viewers. Tag your institution when you want them to know what you are up to or when you are doing something that you think they should be proud of. Tag the professional organizations that would be interested in your work. Tag community leaders. This can be a great way to elevate their voice with your platform. Include an “opinions my own” statement in your social media profiles. Beware of disinformation. Read articles before retweeting. Ignore the trolls. I repeat, ignore the trolls.

CONCLUSION

I did not start my career with a focus on advocacy and in becoming an advocate, I have not given up my previous focus on asthma research. I did not get an advanced degree or specialized training in advocacy. I let my passion drive me. I am now an active member and leader in our Moms Demand Action chapter. The safe storage campaign in our resident clinic has had significant success. We increased the frequency of discussion of gun safety during well-child visits from 2% to 50% and shared this success at local and national scientific meetings. We have worked with our local media to spread awareness about safe gun storage. We have spent time at the state capital to discuss child access prevention laws with legislators. We have collaborated with community leaders and elected officials for gun violence awareness events. We earned support from leaders at our institution. If you walk through our hospital units, clinics, resident areas, and faculty offices, you will see evidence of our success. Physicians and nurses are still wearing their ribbons from the Wear Orange day on their name badges. “We Can End Gun Violence” signs are hanging on faculty members’ doors. Thanks to local police departments, the clinic has a constant supply of gun locks that are provided to families free of charge. Our residents proudly walk the halls with Be SMART buttons on their badges. These physical reminders of our progress are incredibly motivating as we continue this work. However, it is the quiet moments alone with children and parents who are suffering because of the epidemic of gun violence that really move me. I will not give up this fight until children in our communities are safe.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Andrews wishes to thank Dr. Kelsey Gastineau for her efforts to increase the frequency of gun safety discussions in our Pediatric Primary Care clinic and for her support in all of this work.

1. Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Carter PM. The major causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(25):2468-2475. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1804754.

2. Prevention CfDCa. National centers for injury prevention and control, web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS) Fatal Injury Reports. 2013-2017.

3. Goyal MK, Badolato GM, Patel SJ, Iqbal SF, Parikh K, McCarter R. State gun laws and pediatric firearm-related mortality. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3283

4. Grossman DC, Mueller BA , Riedy C, Dowd MD, Villaveces A, Prodzinski J, et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA. 2005;293(6):707-714. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.6.707.

5. Azrael D, Cohen J, Salhi C, Miller M. Firearm storage in gun-owning households with children: results of a 2015 national survey. J Urban Health. 2018;95(3):295-304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0261-7

I stand in the hospital room of a little girl who was shot in her own home just two weeks ago. She was drawing in her sketchbook when a group of teenagers drove by her apartment and took aim. She was shot twice in the chest. Her life and her health will forever be altered. I am not part of her care team, but I am there because just hours after their arrival to the hospital her mother declared that she was going to do something, that gun violence must be stopped. She wants to speak out and she wants to give her daughter a voice. She does not want this to happen to other little girls. My colleagues know that I can help this woman by elevating her voice, by telling her daughter’s story. I have found a passion in gun violence prevention advocacy and I fight every day for little girls like this.

For almost 10 years, I studied asthma. I presented lectures. I conducted research. I published papers. It was my thing. In fact, it still is my thing. But one day shortly after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, I was dropping my oldest daughter off at Kindergarten and for the first time, I saw an armed police officer patrolling the drop-off line. It hit me like a ton of bricks. I went home and called my Senators and Representatives. As I was talking to an aide about evidence-based gun safety legislation, I lost it. I started crying. I finished the call and just sat there. I was momentarily frozen, uncertain of what to do next yet compelled to take action. I decided to attend a meeting of a local gun violence prevention group. Maybe this action of going to one meeting would quell the anxiety and fear that was building inside of me. I found my local Moms Demand Action chapter and I went. About halfway through the meeting, the chapter leader began describing their gun safety campaign, Be SMART for kids, and mentioned that they had been trying to make connections with the Children’s Hospital. That is the moment. That is when it clicked. I have a voice that this movement needs. I can help them. And I did.

Gun violence is the second leading cause of death in children.1 Gun violence is a public health epidemic. Every day in America, approximately 100 people are shot and killed.2 The rate of firearm deaths among children and teens in the United States is 36.5 times higher than that of 12 other high-income countries.1 We know that states with stricter gun laws have lower rates of child firearm mortality.3 We also know that safe gun storage practices (storing guns locked, unloaded, and separate from ammunition) reduce the risk of suicide and firearm injuries,4 yet 4.6 million American children live in a home with a loaded, unlocked firearm.5 Promoting safe gun storage practices and advocating for common sense gun safety legislation are two effective ways to address this crisis.

Gun violence prevention is my passion, but it might not be yours. Regardless of your passion, the blueprint for becoming a physician advocate is the same.

WHY DO PHYSICIANS MAKE NATURAL, EFFECTIVE ADVOCATES?

Advocacy, in its most distilled form, is speaking out for something you believe in, often for someone who cannot speak out for themselves. This is at the core of what we, as healthcare providers, do every day. We help people through some of the hardest moments of their lives, when they are sick and vulnerable. Every day, we are faced with problems that need to be solved. Our experience at the bedside helps us understand how policies affect real people. We understand evidence, data, and science. We recognize that anecdotes are powerful but if not backed up with data will be unlikely to lead to meaningful change. Perhaps most importantly, as professional members of the community, we have agency. We can use our voice and our privilege as physicians to elevate the voices of others.

As you go through medical training, you may not even realize that what you are doing on a daily basis is advocacy. But there comes a moment when you realize that the problem is bigger than the individual patient in front of you. There are systems that are broken that, if fixed, could improve the health of patients everywhere and save lives. To create change on a population level, the status quo will need to be challenged and systems may need to be disrupted.

Hospitalists are particularly well positioned to be advocates because we interact with virtually all aspects of the healthcare system either directly or indirectly. We care for patients with a myriad of disease processes and medical needs using varying levels of resources and social support systems. We often see patients in their most dire moments and, unlike outpatient physicians, we have the luxury of time. Hospitalized patients are a captive audience. We have time to educate, assess what patients need, and connect patients with community resources.

HOW TO BECOME A PHYSICIAN ADVOCATE

Find your passion. Often, your passion will find you. When it does, listen to it. Initially, most of your advocacy will be done on your own time. If you are not passionate about your cause, you will struggle and you will be less likely to be an effective advocate. Keep in mind that sometimes the deeper you dig into an issue, the bigger problems you find and, as a result, your passion can grow.

Do your research. Read the literature. Do you really understand the issue? Identify local and national experts, read their work, and follow their careers. You do not need an advanced degree. Your experience as a physician, willingness to learn, and your voice are all you need.

Start small. Do something small every day. Read an article. Make a new contact. Talk to a colleague. Be thoughtful in your approach. Is this a problem that community advocacy can solve? Will legislation be an effective way to achieve my goal? Would state or federal legislation be more appropriate? In most cases, a combination of community advocacy and legislative advocacy is necessary.

Partner with community organizations. Find local organizations that have existing infrastructure and are engaged on the issue and create partnerships. Community organizations are fighting every day and are waiting for a powerful authoritative voice like yours. They want your voice and you need their support.

Find your allies and your challengers. Identify allies in your community, your institution, your field, and in government. Anticipate potential challengers. When you encounter them, work diligently to find common ground and be respectful. If you only talk to people who agree with you, you will not make progress. Tread carefully when necessary. Develop a thick skin. Read people and try to figure out what it is that they want, what is motivating their position. Make your first ask small and as noncontroversial as possible. Stick to the facts. If you keep your patients at the heart of what you are doing, it is hard to go wrong.

Stay focused and disciplined, but do not quiet the anger and frustration that you feel. That is your fuel. Build momentum and build your team. Passion is contagious; when people see that you are making progress, they will want to join you. Together, you can create a dialog that will change minds.

Align advocacy with your other work. Ideally, this work will not be done in isolation from your other professional duties. Advocacy initiatives make excellent quality improvement projects. When you identify holes in the evidence that could potentially inform the policy debate, apply health services research methods and publish. This approach builds the evidence base to affect change and contributes to your professional development. Consider developing an advocacy curriculum for trainees. Identify trainees interested in advocacy and mentor them. Look for opportunities to speak and write on the topic. Use your unique skillset to further your cause.

Work with your employer. Find common ground. Even if they fundamentally disagree with your point of view, you can still speak out as a private citizen. Recognize the difference between speaking as a physician and speaking as an employee of a specific institution. Unless you have explicit permission, you are speaking for yourself, not your institution. Do not be afraid to push leaders at your institution. Help them see why it is important for you to speak up on a particular issue. If your professional organization has a statement on the issue, use it to support your position.

Leverage social media. Social media is a powerful method to amplify your voice. Consider the impact of the #thisisourlane movement. It will connect you with people, across the world, who share similar passions. It will help you identify local allies. It will open opportunities for speaking engagements and publications. It can be a great way to bring positive attention to your institution. It will take time to find your voice. Try to use consistent messaging. Keep it professional. Tag people who you want to see the great work you are doing. It only takes one retweet by someone with hundreds of thousands of followers to get your message in the feed of exponentially more viewers. Tag your institution when you want them to know what you are up to or when you are doing something that you think they should be proud of. Tag the professional organizations that would be interested in your work. Tag community leaders. This can be a great way to elevate their voice with your platform. Include an “opinions my own” statement in your social media profiles. Beware of disinformation. Read articles before retweeting. Ignore the trolls. I repeat, ignore the trolls.

CONCLUSION

I did not start my career with a focus on advocacy and in becoming an advocate, I have not given up my previous focus on asthma research. I did not get an advanced degree or specialized training in advocacy. I let my passion drive me. I am now an active member and leader in our Moms Demand Action chapter. The safe storage campaign in our resident clinic has had significant success. We increased the frequency of discussion of gun safety during well-child visits from 2% to 50% and shared this success at local and national scientific meetings. We have worked with our local media to spread awareness about safe gun storage. We have spent time at the state capital to discuss child access prevention laws with legislators. We have collaborated with community leaders and elected officials for gun violence awareness events. We earned support from leaders at our institution. If you walk through our hospital units, clinics, resident areas, and faculty offices, you will see evidence of our success. Physicians and nurses are still wearing their ribbons from the Wear Orange day on their name badges. “We Can End Gun Violence” signs are hanging on faculty members’ doors. Thanks to local police departments, the clinic has a constant supply of gun locks that are provided to families free of charge. Our residents proudly walk the halls with Be SMART buttons on their badges. These physical reminders of our progress are incredibly motivating as we continue this work. However, it is the quiet moments alone with children and parents who are suffering because of the epidemic of gun violence that really move me. I will not give up this fight until children in our communities are safe.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Andrews wishes to thank Dr. Kelsey Gastineau for her efforts to increase the frequency of gun safety discussions in our Pediatric Primary Care clinic and for her support in all of this work.