User login

I stand in the hospital room of a little girl who was shot in her own home just two weeks ago. She was drawing in her sketchbook when a group of teenagers drove by her apartment and took aim. She was shot twice in the chest. Her life and her health will forever be altered. I am not part of her care team, but I am there because just hours after their arrival to the hospital her mother declared that she was going to do something, that gun violence must be stopped. She wants to speak out and she wants to give her daughter a voice. She does not want this to happen to other little girls. My colleagues know that I can help this woman by elevating her voice, by telling her daughter’s story. I have found a passion in gun violence prevention advocacy and I fight every day for little girls like this.

For almost 10 years, I studied asthma. I presented lectures. I conducted research. I published papers. It was my thing. In fact, it still is my thing. But one day shortly after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, I was dropping my oldest daughter off at Kindergarten and for the first time, I saw an armed police officer patrolling the drop-off line. It hit me like a ton of bricks. I went home and called my Senators and Representatives. As I was talking to an aide about evidence-based gun safety legislation, I lost it. I started crying. I finished the call and just sat there. I was momentarily frozen, uncertain of what to do next yet compelled to take action. I decided to attend a meeting of a local gun violence prevention group. Maybe this action of going to one meeting would quell the anxiety and fear that was building inside of me. I found my local Moms Demand Action chapter and I went. About halfway through the meeting, the chapter leader began describing their gun safety campaign, Be SMART for kids, and mentioned that they had been trying to make connections with the Children’s Hospital. That is the moment. That is when it clicked. I have a voice that this movement needs. I can help them. And I did.

Gun violence is the second leading cause of death in children.1 Gun violence is a public health epidemic. Every day in America, approximately 100 people are shot and killed.2 The rate of firearm deaths among children and teens in the United States is 36.5 times higher than that of 12 other high-income countries.1 We know that states with stricter gun laws have lower rates of child firearm mortality.3 We also know that safe gun storage practices (storing guns locked, unloaded, and separate from ammunition) reduce the risk of suicide and firearm injuries,4 yet 4.6 million American children live in a home with a loaded, unlocked firearm.5 Promoting safe gun storage practices and advocating for common sense gun safety legislation are two effective ways to address this crisis.

Gun violence prevention is my passion, but it might not be yours. Regardless of your passion, the blueprint for becoming a physician advocate is the same.

WHY DO PHYSICIANS MAKE NATURAL, EFFECTIVE ADVOCATES?

Advocacy, in its most distilled form, is speaking out for something you believe in, often for someone who cannot speak out for themselves. This is at the core of what we, as healthcare providers, do every day. We help people through some of the hardest moments of their lives, when they are sick and vulnerable. Every day, we are faced with problems that need to be solved. Our experience at the bedside helps us understand how policies affect real people. We understand evidence, data, and science. We recognize that anecdotes are powerful but if not backed up with data will be unlikely to lead to meaningful change. Perhaps most importantly, as professional members of the community, we have agency. We can use our voice and our privilege as physicians to elevate the voices of others.

As you go through medical training, you may not even realize that what you are doing on a daily basis is advocacy. But there comes a moment when you realize that the problem is bigger than the individual patient in front of you. There are systems that are broken that, if fixed, could improve the health of patients everywhere and save lives. To create change on a population level, the status quo will need to be challenged and systems may need to be disrupted.

Hospitalists are particularly well positioned to be advocates because we interact with virtually all aspects of the healthcare system either directly or indirectly. We care for patients with a myriad of disease processes and medical needs using varying levels of resources and social support systems. We often see patients in their most dire moments and, unlike outpatient physicians, we have the luxury of time. Hospitalized patients are a captive audience. We have time to educate, assess what patients need, and connect patients with community resources.

HOW TO BECOME A PHYSICIAN ADVOCATE

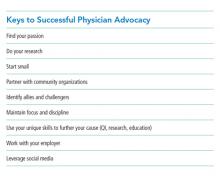

Find your passion. Often, your passion will find you. When it does, listen to it. Initially, most of your advocacy will be done on your own time. If you are not passionate about your cause, you will struggle and you will be less likely to be an effective advocate. Keep in mind that sometimes the deeper you dig into an issue, the bigger problems you find and, as a result, your passion can grow.

Do your research. Read the literature. Do you really understand the issue? Identify local and national experts, read their work, and follow their careers. You do not need an advanced degree. Your experience as a physician, willingness to learn, and your voice are all you need.

Start small. Do something small every day. Read an article. Make a new contact. Talk to a colleague. Be thoughtful in your approach. Is this a problem that community advocacy can solve? Will legislation be an effective way to achieve my goal? Would state or federal legislation be more appropriate? In most cases, a combination of community advocacy and legislative advocacy is necessary.

Partner with community organizations. Find local organizations that have existing infrastructure and are engaged on the issue and create partnerships. Community organizations are fighting every day and are waiting for a powerful authoritative voice like yours. They want your voice and you need their support.

Find your allies and your challengers. Identify allies in your community, your institution, your field, and in government. Anticipate potential challengers. When you encounter them, work diligently to find common ground and be respectful. If you only talk to people who agree with you, you will not make progress. Tread carefully when necessary. Develop a thick skin. Read people and try to figure out what it is that they want, what is motivating their position. Make your first ask small and as noncontroversial as possible. Stick to the facts. If you keep your patients at the heart of what you are doing, it is hard to go wrong.

Stay focused and disciplined, but do not quiet the anger and frustration that you feel. That is your fuel. Build momentum and build your team. Passion is contagious; when people see that you are making progress, they will want to join you. Together, you can create a dialog that will change minds.

Align advocacy with your other work. Ideally, this work will not be done in isolation from your other professional duties. Advocacy initiatives make excellent quality improvement projects. When you identify holes in the evidence that could potentially inform the policy debate, apply health services research methods and publish. This approach builds the evidence base to affect change and contributes to your professional development. Consider developing an advocacy curriculum for trainees. Identify trainees interested in advocacy and mentor them. Look for opportunities to speak and write on the topic. Use your unique skillset to further your cause.

Work with your employer. Find common ground. Even if they fundamentally disagree with your point of view, you can still speak out as a private citizen. Recognize the difference between speaking as a physician and speaking as an employee of a specific institution. Unless you have explicit permission, you are speaking for yourself, not your institution. Do not be afraid to push leaders at your institution. Help them see why it is important for you to speak up on a particular issue. If your professional organization has a statement on the issue, use it to support your position.

Leverage social media. Social media is a powerful method to amplify your voice. Consider the impact of the #thisisourlane movement. It will connect you with people, across the world, who share similar passions. It will help you identify local allies. It will open opportunities for speaking engagements and publications. It can be a great way to bring positive attention to your institution. It will take time to find your voice. Try to use consistent messaging. Keep it professional. Tag people who you want to see the great work you are doing. It only takes one retweet by someone with hundreds of thousands of followers to get your message in the feed of exponentially more viewers. Tag your institution when you want them to know what you are up to or when you are doing something that you think they should be proud of. Tag the professional organizations that would be interested in your work. Tag community leaders. This can be a great way to elevate their voice with your platform. Include an “opinions my own” statement in your social media profiles. Beware of disinformation. Read articles before retweeting. Ignore the trolls. I repeat, ignore the trolls.

CONCLUSION

I did not start my career with a focus on advocacy and in becoming an advocate, I have not given up my previous focus on asthma research. I did not get an advanced degree or specialized training in advocacy. I let my passion drive me. I am now an active member and leader in our Moms Demand Action chapter. The safe storage campaign in our resident clinic has had significant success. We increased the frequency of discussion of gun safety during well-child visits from 2% to 50% and shared this success at local and national scientific meetings. We have worked with our local media to spread awareness about safe gun storage. We have spent time at the state capital to discuss child access prevention laws with legislators. We have collaborated with community leaders and elected officials for gun violence awareness events. We earned support from leaders at our institution. If you walk through our hospital units, clinics, resident areas, and faculty offices, you will see evidence of our success. Physicians and nurses are still wearing their ribbons from the Wear Orange day on their name badges. “We Can End Gun Violence” signs are hanging on faculty members’ doors. Thanks to local police departments, the clinic has a constant supply of gun locks that are provided to families free of charge. Our residents proudly walk the halls with Be SMART buttons on their badges. These physical reminders of our progress are incredibly motivating as we continue this work. However, it is the quiet moments alone with children and parents who are suffering because of the epidemic of gun violence that really move me. I will not give up this fight until children in our communities are safe.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Andrews wishes to thank Dr. Kelsey Gastineau for her efforts to increase the frequency of gun safety discussions in our Pediatric Primary Care clinic and for her support in all of this work.

1. Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Carter PM. The major causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(25):2468-2475. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1804754.

2. Prevention CfDCa. National centers for injury prevention and control, web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS) Fatal Injury Reports. 2013-2017.

3. Goyal MK, Badolato GM, Patel SJ, Iqbal SF, Parikh K, McCarter R. State gun laws and pediatric firearm-related mortality. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3283

4. Grossman DC, Mueller BA , Riedy C, Dowd MD, Villaveces A, Prodzinski J, et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA. 2005;293(6):707-714. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.6.707.

5. Azrael D, Cohen J, Salhi C, Miller M. Firearm storage in gun-owning households with children: results of a 2015 national survey. J Urban Health. 2018;95(3):295-304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0261-7

I stand in the hospital room of a little girl who was shot in her own home just two weeks ago. She was drawing in her sketchbook when a group of teenagers drove by her apartment and took aim. She was shot twice in the chest. Her life and her health will forever be altered. I am not part of her care team, but I am there because just hours after their arrival to the hospital her mother declared that she was going to do something, that gun violence must be stopped. She wants to speak out and she wants to give her daughter a voice. She does not want this to happen to other little girls. My colleagues know that I can help this woman by elevating her voice, by telling her daughter’s story. I have found a passion in gun violence prevention advocacy and I fight every day for little girls like this.

For almost 10 years, I studied asthma. I presented lectures. I conducted research. I published papers. It was my thing. In fact, it still is my thing. But one day shortly after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, I was dropping my oldest daughter off at Kindergarten and for the first time, I saw an armed police officer patrolling the drop-off line. It hit me like a ton of bricks. I went home and called my Senators and Representatives. As I was talking to an aide about evidence-based gun safety legislation, I lost it. I started crying. I finished the call and just sat there. I was momentarily frozen, uncertain of what to do next yet compelled to take action. I decided to attend a meeting of a local gun violence prevention group. Maybe this action of going to one meeting would quell the anxiety and fear that was building inside of me. I found my local Moms Demand Action chapter and I went. About halfway through the meeting, the chapter leader began describing their gun safety campaign, Be SMART for kids, and mentioned that they had been trying to make connections with the Children’s Hospital. That is the moment. That is when it clicked. I have a voice that this movement needs. I can help them. And I did.

Gun violence is the second leading cause of death in children.1 Gun violence is a public health epidemic. Every day in America, approximately 100 people are shot and killed.2 The rate of firearm deaths among children and teens in the United States is 36.5 times higher than that of 12 other high-income countries.1 We know that states with stricter gun laws have lower rates of child firearm mortality.3 We also know that safe gun storage practices (storing guns locked, unloaded, and separate from ammunition) reduce the risk of suicide and firearm injuries,4 yet 4.6 million American children live in a home with a loaded, unlocked firearm.5 Promoting safe gun storage practices and advocating for common sense gun safety legislation are two effective ways to address this crisis.

Gun violence prevention is my passion, but it might not be yours. Regardless of your passion, the blueprint for becoming a physician advocate is the same.

WHY DO PHYSICIANS MAKE NATURAL, EFFECTIVE ADVOCATES?

Advocacy, in its most distilled form, is speaking out for something you believe in, often for someone who cannot speak out for themselves. This is at the core of what we, as healthcare providers, do every day. We help people through some of the hardest moments of their lives, when they are sick and vulnerable. Every day, we are faced with problems that need to be solved. Our experience at the bedside helps us understand how policies affect real people. We understand evidence, data, and science. We recognize that anecdotes are powerful but if not backed up with data will be unlikely to lead to meaningful change. Perhaps most importantly, as professional members of the community, we have agency. We can use our voice and our privilege as physicians to elevate the voices of others.

As you go through medical training, you may not even realize that what you are doing on a daily basis is advocacy. But there comes a moment when you realize that the problem is bigger than the individual patient in front of you. There are systems that are broken that, if fixed, could improve the health of patients everywhere and save lives. To create change on a population level, the status quo will need to be challenged and systems may need to be disrupted.

Hospitalists are particularly well positioned to be advocates because we interact with virtually all aspects of the healthcare system either directly or indirectly. We care for patients with a myriad of disease processes and medical needs using varying levels of resources and social support systems. We often see patients in their most dire moments and, unlike outpatient physicians, we have the luxury of time. Hospitalized patients are a captive audience. We have time to educate, assess what patients need, and connect patients with community resources.

HOW TO BECOME A PHYSICIAN ADVOCATE

Find your passion. Often, your passion will find you. When it does, listen to it. Initially, most of your advocacy will be done on your own time. If you are not passionate about your cause, you will struggle and you will be less likely to be an effective advocate. Keep in mind that sometimes the deeper you dig into an issue, the bigger problems you find and, as a result, your passion can grow.

Do your research. Read the literature. Do you really understand the issue? Identify local and national experts, read their work, and follow their careers. You do not need an advanced degree. Your experience as a physician, willingness to learn, and your voice are all you need.

Start small. Do something small every day. Read an article. Make a new contact. Talk to a colleague. Be thoughtful in your approach. Is this a problem that community advocacy can solve? Will legislation be an effective way to achieve my goal? Would state or federal legislation be more appropriate? In most cases, a combination of community advocacy and legislative advocacy is necessary.

Partner with community organizations. Find local organizations that have existing infrastructure and are engaged on the issue and create partnerships. Community organizations are fighting every day and are waiting for a powerful authoritative voice like yours. They want your voice and you need their support.

Find your allies and your challengers. Identify allies in your community, your institution, your field, and in government. Anticipate potential challengers. When you encounter them, work diligently to find common ground and be respectful. If you only talk to people who agree with you, you will not make progress. Tread carefully when necessary. Develop a thick skin. Read people and try to figure out what it is that they want, what is motivating their position. Make your first ask small and as noncontroversial as possible. Stick to the facts. If you keep your patients at the heart of what you are doing, it is hard to go wrong.

Stay focused and disciplined, but do not quiet the anger and frustration that you feel. That is your fuel. Build momentum and build your team. Passion is contagious; when people see that you are making progress, they will want to join you. Together, you can create a dialog that will change minds.

Align advocacy with your other work. Ideally, this work will not be done in isolation from your other professional duties. Advocacy initiatives make excellent quality improvement projects. When you identify holes in the evidence that could potentially inform the policy debate, apply health services research methods and publish. This approach builds the evidence base to affect change and contributes to your professional development. Consider developing an advocacy curriculum for trainees. Identify trainees interested in advocacy and mentor them. Look for opportunities to speak and write on the topic. Use your unique skillset to further your cause.

Work with your employer. Find common ground. Even if they fundamentally disagree with your point of view, you can still speak out as a private citizen. Recognize the difference between speaking as a physician and speaking as an employee of a specific institution. Unless you have explicit permission, you are speaking for yourself, not your institution. Do not be afraid to push leaders at your institution. Help them see why it is important for you to speak up on a particular issue. If your professional organization has a statement on the issue, use it to support your position.

Leverage social media. Social media is a powerful method to amplify your voice. Consider the impact of the #thisisourlane movement. It will connect you with people, across the world, who share similar passions. It will help you identify local allies. It will open opportunities for speaking engagements and publications. It can be a great way to bring positive attention to your institution. It will take time to find your voice. Try to use consistent messaging. Keep it professional. Tag people who you want to see the great work you are doing. It only takes one retweet by someone with hundreds of thousands of followers to get your message in the feed of exponentially more viewers. Tag your institution when you want them to know what you are up to or when you are doing something that you think they should be proud of. Tag the professional organizations that would be interested in your work. Tag community leaders. This can be a great way to elevate their voice with your platform. Include an “opinions my own” statement in your social media profiles. Beware of disinformation. Read articles before retweeting. Ignore the trolls. I repeat, ignore the trolls.

CONCLUSION

I did not start my career with a focus on advocacy and in becoming an advocate, I have not given up my previous focus on asthma research. I did not get an advanced degree or specialized training in advocacy. I let my passion drive me. I am now an active member and leader in our Moms Demand Action chapter. The safe storage campaign in our resident clinic has had significant success. We increased the frequency of discussion of gun safety during well-child visits from 2% to 50% and shared this success at local and national scientific meetings. We have worked with our local media to spread awareness about safe gun storage. We have spent time at the state capital to discuss child access prevention laws with legislators. We have collaborated with community leaders and elected officials for gun violence awareness events. We earned support from leaders at our institution. If you walk through our hospital units, clinics, resident areas, and faculty offices, you will see evidence of our success. Physicians and nurses are still wearing their ribbons from the Wear Orange day on their name badges. “We Can End Gun Violence” signs are hanging on faculty members’ doors. Thanks to local police departments, the clinic has a constant supply of gun locks that are provided to families free of charge. Our residents proudly walk the halls with Be SMART buttons on their badges. These physical reminders of our progress are incredibly motivating as we continue this work. However, it is the quiet moments alone with children and parents who are suffering because of the epidemic of gun violence that really move me. I will not give up this fight until children in our communities are safe.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Andrews wishes to thank Dr. Kelsey Gastineau for her efforts to increase the frequency of gun safety discussions in our Pediatric Primary Care clinic and for her support in all of this work.

I stand in the hospital room of a little girl who was shot in her own home just two weeks ago. She was drawing in her sketchbook when a group of teenagers drove by her apartment and took aim. She was shot twice in the chest. Her life and her health will forever be altered. I am not part of her care team, but I am there because just hours after their arrival to the hospital her mother declared that she was going to do something, that gun violence must be stopped. She wants to speak out and she wants to give her daughter a voice. She does not want this to happen to other little girls. My colleagues know that I can help this woman by elevating her voice, by telling her daughter’s story. I have found a passion in gun violence prevention advocacy and I fight every day for little girls like this.

For almost 10 years, I studied asthma. I presented lectures. I conducted research. I published papers. It was my thing. In fact, it still is my thing. But one day shortly after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, I was dropping my oldest daughter off at Kindergarten and for the first time, I saw an armed police officer patrolling the drop-off line. It hit me like a ton of bricks. I went home and called my Senators and Representatives. As I was talking to an aide about evidence-based gun safety legislation, I lost it. I started crying. I finished the call and just sat there. I was momentarily frozen, uncertain of what to do next yet compelled to take action. I decided to attend a meeting of a local gun violence prevention group. Maybe this action of going to one meeting would quell the anxiety and fear that was building inside of me. I found my local Moms Demand Action chapter and I went. About halfway through the meeting, the chapter leader began describing their gun safety campaign, Be SMART for kids, and mentioned that they had been trying to make connections with the Children’s Hospital. That is the moment. That is when it clicked. I have a voice that this movement needs. I can help them. And I did.

Gun violence is the second leading cause of death in children.1 Gun violence is a public health epidemic. Every day in America, approximately 100 people are shot and killed.2 The rate of firearm deaths among children and teens in the United States is 36.5 times higher than that of 12 other high-income countries.1 We know that states with stricter gun laws have lower rates of child firearm mortality.3 We also know that safe gun storage practices (storing guns locked, unloaded, and separate from ammunition) reduce the risk of suicide and firearm injuries,4 yet 4.6 million American children live in a home with a loaded, unlocked firearm.5 Promoting safe gun storage practices and advocating for common sense gun safety legislation are two effective ways to address this crisis.

Gun violence prevention is my passion, but it might not be yours. Regardless of your passion, the blueprint for becoming a physician advocate is the same.

WHY DO PHYSICIANS MAKE NATURAL, EFFECTIVE ADVOCATES?

Advocacy, in its most distilled form, is speaking out for something you believe in, often for someone who cannot speak out for themselves. This is at the core of what we, as healthcare providers, do every day. We help people through some of the hardest moments of their lives, when they are sick and vulnerable. Every day, we are faced with problems that need to be solved. Our experience at the bedside helps us understand how policies affect real people. We understand evidence, data, and science. We recognize that anecdotes are powerful but if not backed up with data will be unlikely to lead to meaningful change. Perhaps most importantly, as professional members of the community, we have agency. We can use our voice and our privilege as physicians to elevate the voices of others.

As you go through medical training, you may not even realize that what you are doing on a daily basis is advocacy. But there comes a moment when you realize that the problem is bigger than the individual patient in front of you. There are systems that are broken that, if fixed, could improve the health of patients everywhere and save lives. To create change on a population level, the status quo will need to be challenged and systems may need to be disrupted.

Hospitalists are particularly well positioned to be advocates because we interact with virtually all aspects of the healthcare system either directly or indirectly. We care for patients with a myriad of disease processes and medical needs using varying levels of resources and social support systems. We often see patients in their most dire moments and, unlike outpatient physicians, we have the luxury of time. Hospitalized patients are a captive audience. We have time to educate, assess what patients need, and connect patients with community resources.

HOW TO BECOME A PHYSICIAN ADVOCATE

Find your passion. Often, your passion will find you. When it does, listen to it. Initially, most of your advocacy will be done on your own time. If you are not passionate about your cause, you will struggle and you will be less likely to be an effective advocate. Keep in mind that sometimes the deeper you dig into an issue, the bigger problems you find and, as a result, your passion can grow.

Do your research. Read the literature. Do you really understand the issue? Identify local and national experts, read their work, and follow their careers. You do not need an advanced degree. Your experience as a physician, willingness to learn, and your voice are all you need.

Start small. Do something small every day. Read an article. Make a new contact. Talk to a colleague. Be thoughtful in your approach. Is this a problem that community advocacy can solve? Will legislation be an effective way to achieve my goal? Would state or federal legislation be more appropriate? In most cases, a combination of community advocacy and legislative advocacy is necessary.

Partner with community organizations. Find local organizations that have existing infrastructure and are engaged on the issue and create partnerships. Community organizations are fighting every day and are waiting for a powerful authoritative voice like yours. They want your voice and you need their support.

Find your allies and your challengers. Identify allies in your community, your institution, your field, and in government. Anticipate potential challengers. When you encounter them, work diligently to find common ground and be respectful. If you only talk to people who agree with you, you will not make progress. Tread carefully when necessary. Develop a thick skin. Read people and try to figure out what it is that they want, what is motivating their position. Make your first ask small and as noncontroversial as possible. Stick to the facts. If you keep your patients at the heart of what you are doing, it is hard to go wrong.

Stay focused and disciplined, but do not quiet the anger and frustration that you feel. That is your fuel. Build momentum and build your team. Passion is contagious; when people see that you are making progress, they will want to join you. Together, you can create a dialog that will change minds.

Align advocacy with your other work. Ideally, this work will not be done in isolation from your other professional duties. Advocacy initiatives make excellent quality improvement projects. When you identify holes in the evidence that could potentially inform the policy debate, apply health services research methods and publish. This approach builds the evidence base to affect change and contributes to your professional development. Consider developing an advocacy curriculum for trainees. Identify trainees interested in advocacy and mentor them. Look for opportunities to speak and write on the topic. Use your unique skillset to further your cause.

Work with your employer. Find common ground. Even if they fundamentally disagree with your point of view, you can still speak out as a private citizen. Recognize the difference between speaking as a physician and speaking as an employee of a specific institution. Unless you have explicit permission, you are speaking for yourself, not your institution. Do not be afraid to push leaders at your institution. Help them see why it is important for you to speak up on a particular issue. If your professional organization has a statement on the issue, use it to support your position.

Leverage social media. Social media is a powerful method to amplify your voice. Consider the impact of the #thisisourlane movement. It will connect you with people, across the world, who share similar passions. It will help you identify local allies. It will open opportunities for speaking engagements and publications. It can be a great way to bring positive attention to your institution. It will take time to find your voice. Try to use consistent messaging. Keep it professional. Tag people who you want to see the great work you are doing. It only takes one retweet by someone with hundreds of thousands of followers to get your message in the feed of exponentially more viewers. Tag your institution when you want them to know what you are up to or when you are doing something that you think they should be proud of. Tag the professional organizations that would be interested in your work. Tag community leaders. This can be a great way to elevate their voice with your platform. Include an “opinions my own” statement in your social media profiles. Beware of disinformation. Read articles before retweeting. Ignore the trolls. I repeat, ignore the trolls.

CONCLUSION

I did not start my career with a focus on advocacy and in becoming an advocate, I have not given up my previous focus on asthma research. I did not get an advanced degree or specialized training in advocacy. I let my passion drive me. I am now an active member and leader in our Moms Demand Action chapter. The safe storage campaign in our resident clinic has had significant success. We increased the frequency of discussion of gun safety during well-child visits from 2% to 50% and shared this success at local and national scientific meetings. We have worked with our local media to spread awareness about safe gun storage. We have spent time at the state capital to discuss child access prevention laws with legislators. We have collaborated with community leaders and elected officials for gun violence awareness events. We earned support from leaders at our institution. If you walk through our hospital units, clinics, resident areas, and faculty offices, you will see evidence of our success. Physicians and nurses are still wearing their ribbons from the Wear Orange day on their name badges. “We Can End Gun Violence” signs are hanging on faculty members’ doors. Thanks to local police departments, the clinic has a constant supply of gun locks that are provided to families free of charge. Our residents proudly walk the halls with Be SMART buttons on their badges. These physical reminders of our progress are incredibly motivating as we continue this work. However, it is the quiet moments alone with children and parents who are suffering because of the epidemic of gun violence that really move me. I will not give up this fight until children in our communities are safe.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Andrews wishes to thank Dr. Kelsey Gastineau for her efforts to increase the frequency of gun safety discussions in our Pediatric Primary Care clinic and for her support in all of this work.

1. Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Carter PM. The major causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(25):2468-2475. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1804754.

2. Prevention CfDCa. National centers for injury prevention and control, web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS) Fatal Injury Reports. 2013-2017.

3. Goyal MK, Badolato GM, Patel SJ, Iqbal SF, Parikh K, McCarter R. State gun laws and pediatric firearm-related mortality. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3283

4. Grossman DC, Mueller BA , Riedy C, Dowd MD, Villaveces A, Prodzinski J, et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA. 2005;293(6):707-714. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.6.707.

5. Azrael D, Cohen J, Salhi C, Miller M. Firearm storage in gun-owning households with children: results of a 2015 national survey. J Urban Health. 2018;95(3):295-304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0261-7

1. Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Carter PM. The major causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(25):2468-2475. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1804754.

2. Prevention CfDCa. National centers for injury prevention and control, web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS) Fatal Injury Reports. 2013-2017.

3. Goyal MK, Badolato GM, Patel SJ, Iqbal SF, Parikh K, McCarter R. State gun laws and pediatric firearm-related mortality. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3283

4. Grossman DC, Mueller BA , Riedy C, Dowd MD, Villaveces A, Prodzinski J, et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA. 2005;293(6):707-714. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.6.707.

5. Azrael D, Cohen J, Salhi C, Miller M. Firearm storage in gun-owning households with children: results of a 2015 national survey. J Urban Health. 2018;95(3):295-304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0261-7

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine