User login

Pregabalin‐induced trismus in a leukemia patient

A 24‐year‐old man with relapsed acute myeloid leukemia and leptomeningeal infiltration (confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging, and leukemic cells in the cerebrospinal fluid) was successful treated with systemic and intrathecal chemotherapy. Concomitantly, he developed an anal fissure, which deteriorated despite treatment with meropenem. The pain was so severe that he required multiple analgesics, with little symptomatic improvement.

Findings

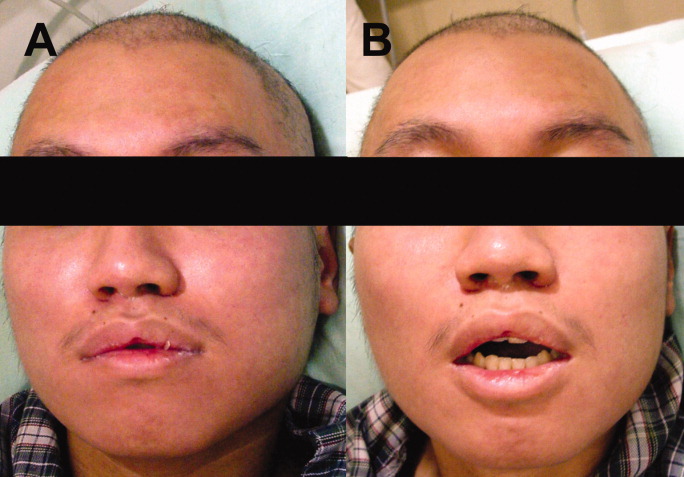

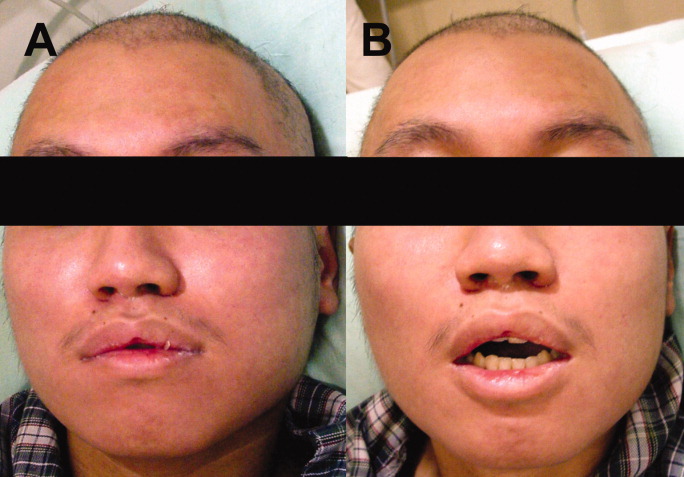

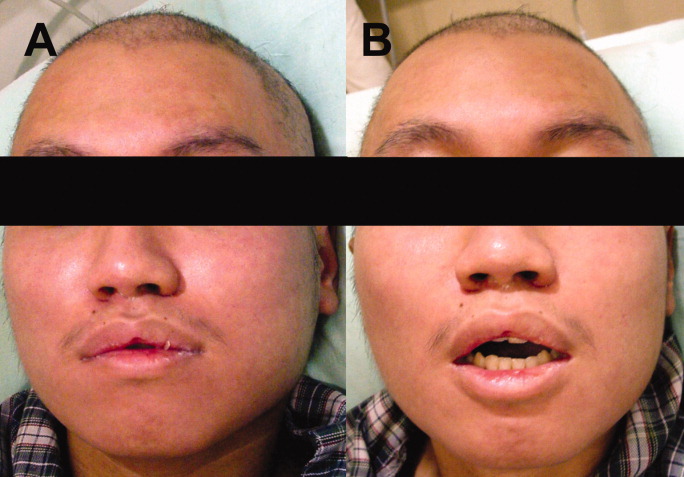

Four weeks afterwards he woke up unable to open his mouth. On physical examination, there was total trismus (Figure 1A). Pharyngeal muscles were also spastic, as he was unable to swallow his saliva or phonate. Respiration was preserved. The anal fissure was inconspicuous with disproportionately excruciating pain. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, besides showing resolution of the leptomeningeal leukemia, was unremarkable.

Because the patient grew up in China with an unclear vaccination history, the physical signs were believed to be potentially consistent with localized tetanus. The source of infection was felt to possibly be the anal fissure, although it is unclear if Clostridium tetani can normally be found in gut flora.1 He was given 500 units of human tetanus immune globulin (antitoxin); and metronidazole was commenced. As he was receiving multiple medications (including tramadol, acetaminophen, celecoxib, pregabalin, metronidazole, moxifloxacin and fexofenadine), drug‐induced oromandibular dystonia was also considered. Intravenous diphenhydramine (25 mg) was administered. There was minimal improvement (Figure 1B), and total trismus rapidly recurred.

The patient was admitted into the intensive care unit for airway monitoring. The trismus gradually improved, and completely resolved after 12 hours. His pharyngeal spasm persisted longer, and phonation remained impaired for about 2 days. There was no recurrence of trismus.

Discussion

The clinical course by then was incompatible with tetanus, which would not improve so quickly. Trismus may be caused by dental or pharyngeal infections, temporomandibular joint disorders, and drugs. The trismus in this patient was painless, ruling out infective or inflammatory causes. A review of adverse effects of drugs he was receiving showed that dystonia had not been reported for tramadol, acetaminophen, celecoxib, metronidazole, moxifloxacin and fexofenadine at therapeutic doses. The package insert of pregabalin made no mention of trismus, and a PubMed search failed to show any such association. However, the on‐line drug information of pregabalin from its manufacturer2 actually includes trismus as a rare (1/1000) side effect, without further elaboration on the cumulative dosage required or treatment. In this patient, 6 daily doses of 75 mg of pregabalin had been administered, the last dose 9 hours before the onset of trismus. Pregabalin binds to the alpha 2 delta subunit of voltage‐dependent calcium channels, reducing the release of neurotransmitters including glutamate, noradrenaline, serotonin, dopamine, and substance P.3 The exact mechanism of and antidote to pregabalin‐induced trismus (or oromandibular dystonia in this case, owing to involvement of pharyngeal muscles) is unknown. Diphenhydramine gave partial relief, an early clue that tetanus was not the cause of the trismus, which would not have been expected to respond to this agent. The exact reason why diphenhydramine, an anticholinergic drug, resulted in temporary relaxation remained unclear.

Pregabalin is approved for adult partial‐onset epilepsy, diabetic neuropathic pain, post‐herpetic neuralgia and fibromyalgia. Therefore, this case represented an off‐label use of pregabalin. The effectiveness of pregabalin for postoperative pain relief has been studied,2 but its efficacy in other types of pain remains undefined. In our patient, pregabalin did not appear to be effective.

This case to our knowledge represents the first report of pregabalin‐induced trismus in the peer‐reviewed literature, although the manufacturer was apparently aware that this association had been seen on rare occasions. This underscores the fact that prescribers need to be vigilant for potential adverse drug reactions in the post‐marketing period, both those rarely previously reported as well as those previously unreported.

Acknowledgements

Y.L. Kwong: treated the patient, wrote the manuscript, A.Y.H. Leung: treated the patient, and approved the manuscript, R.T.F. Cheung: treated the patient, and approved the manuscript.

- ,.Clostridium tetani in a metropolitan area: a limited survey incorporating a simplified in vitro identification test.Appl Microbiol.1966;14:993–997.

- Available at: http://www.pfizer.com/files/products/uspi_lyrica.pdf, page 18. Accessed March2010.

- .Pregabalin: its pharmacology and use in pain management.Anesth Analg.2007;105:1805–1815.

A 24‐year‐old man with relapsed acute myeloid leukemia and leptomeningeal infiltration (confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging, and leukemic cells in the cerebrospinal fluid) was successful treated with systemic and intrathecal chemotherapy. Concomitantly, he developed an anal fissure, which deteriorated despite treatment with meropenem. The pain was so severe that he required multiple analgesics, with little symptomatic improvement.

Findings

Four weeks afterwards he woke up unable to open his mouth. On physical examination, there was total trismus (Figure 1A). Pharyngeal muscles were also spastic, as he was unable to swallow his saliva or phonate. Respiration was preserved. The anal fissure was inconspicuous with disproportionately excruciating pain. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, besides showing resolution of the leptomeningeal leukemia, was unremarkable.

Because the patient grew up in China with an unclear vaccination history, the physical signs were believed to be potentially consistent with localized tetanus. The source of infection was felt to possibly be the anal fissure, although it is unclear if Clostridium tetani can normally be found in gut flora.1 He was given 500 units of human tetanus immune globulin (antitoxin); and metronidazole was commenced. As he was receiving multiple medications (including tramadol, acetaminophen, celecoxib, pregabalin, metronidazole, moxifloxacin and fexofenadine), drug‐induced oromandibular dystonia was also considered. Intravenous diphenhydramine (25 mg) was administered. There was minimal improvement (Figure 1B), and total trismus rapidly recurred.

The patient was admitted into the intensive care unit for airway monitoring. The trismus gradually improved, and completely resolved after 12 hours. His pharyngeal spasm persisted longer, and phonation remained impaired for about 2 days. There was no recurrence of trismus.

Discussion

The clinical course by then was incompatible with tetanus, which would not improve so quickly. Trismus may be caused by dental or pharyngeal infections, temporomandibular joint disorders, and drugs. The trismus in this patient was painless, ruling out infective or inflammatory causes. A review of adverse effects of drugs he was receiving showed that dystonia had not been reported for tramadol, acetaminophen, celecoxib, metronidazole, moxifloxacin and fexofenadine at therapeutic doses. The package insert of pregabalin made no mention of trismus, and a PubMed search failed to show any such association. However, the on‐line drug information of pregabalin from its manufacturer2 actually includes trismus as a rare (1/1000) side effect, without further elaboration on the cumulative dosage required or treatment. In this patient, 6 daily doses of 75 mg of pregabalin had been administered, the last dose 9 hours before the onset of trismus. Pregabalin binds to the alpha 2 delta subunit of voltage‐dependent calcium channels, reducing the release of neurotransmitters including glutamate, noradrenaline, serotonin, dopamine, and substance P.3 The exact mechanism of and antidote to pregabalin‐induced trismus (or oromandibular dystonia in this case, owing to involvement of pharyngeal muscles) is unknown. Diphenhydramine gave partial relief, an early clue that tetanus was not the cause of the trismus, which would not have been expected to respond to this agent. The exact reason why diphenhydramine, an anticholinergic drug, resulted in temporary relaxation remained unclear.

Pregabalin is approved for adult partial‐onset epilepsy, diabetic neuropathic pain, post‐herpetic neuralgia and fibromyalgia. Therefore, this case represented an off‐label use of pregabalin. The effectiveness of pregabalin for postoperative pain relief has been studied,2 but its efficacy in other types of pain remains undefined. In our patient, pregabalin did not appear to be effective.

This case to our knowledge represents the first report of pregabalin‐induced trismus in the peer‐reviewed literature, although the manufacturer was apparently aware that this association had been seen on rare occasions. This underscores the fact that prescribers need to be vigilant for potential adverse drug reactions in the post‐marketing period, both those rarely previously reported as well as those previously unreported.

Acknowledgements

Y.L. Kwong: treated the patient, wrote the manuscript, A.Y.H. Leung: treated the patient, and approved the manuscript, R.T.F. Cheung: treated the patient, and approved the manuscript.

A 24‐year‐old man with relapsed acute myeloid leukemia and leptomeningeal infiltration (confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging, and leukemic cells in the cerebrospinal fluid) was successful treated with systemic and intrathecal chemotherapy. Concomitantly, he developed an anal fissure, which deteriorated despite treatment with meropenem. The pain was so severe that he required multiple analgesics, with little symptomatic improvement.

Findings

Four weeks afterwards he woke up unable to open his mouth. On physical examination, there was total trismus (Figure 1A). Pharyngeal muscles were also spastic, as he was unable to swallow his saliva or phonate. Respiration was preserved. The anal fissure was inconspicuous with disproportionately excruciating pain. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, besides showing resolution of the leptomeningeal leukemia, was unremarkable.

Because the patient grew up in China with an unclear vaccination history, the physical signs were believed to be potentially consistent with localized tetanus. The source of infection was felt to possibly be the anal fissure, although it is unclear if Clostridium tetani can normally be found in gut flora.1 He was given 500 units of human tetanus immune globulin (antitoxin); and metronidazole was commenced. As he was receiving multiple medications (including tramadol, acetaminophen, celecoxib, pregabalin, metronidazole, moxifloxacin and fexofenadine), drug‐induced oromandibular dystonia was also considered. Intravenous diphenhydramine (25 mg) was administered. There was minimal improvement (Figure 1B), and total trismus rapidly recurred.

The patient was admitted into the intensive care unit for airway monitoring. The trismus gradually improved, and completely resolved after 12 hours. His pharyngeal spasm persisted longer, and phonation remained impaired for about 2 days. There was no recurrence of trismus.

Discussion

The clinical course by then was incompatible with tetanus, which would not improve so quickly. Trismus may be caused by dental or pharyngeal infections, temporomandibular joint disorders, and drugs. The trismus in this patient was painless, ruling out infective or inflammatory causes. A review of adverse effects of drugs he was receiving showed that dystonia had not been reported for tramadol, acetaminophen, celecoxib, metronidazole, moxifloxacin and fexofenadine at therapeutic doses. The package insert of pregabalin made no mention of trismus, and a PubMed search failed to show any such association. However, the on‐line drug information of pregabalin from its manufacturer2 actually includes trismus as a rare (1/1000) side effect, without further elaboration on the cumulative dosage required or treatment. In this patient, 6 daily doses of 75 mg of pregabalin had been administered, the last dose 9 hours before the onset of trismus. Pregabalin binds to the alpha 2 delta subunit of voltage‐dependent calcium channels, reducing the release of neurotransmitters including glutamate, noradrenaline, serotonin, dopamine, and substance P.3 The exact mechanism of and antidote to pregabalin‐induced trismus (or oromandibular dystonia in this case, owing to involvement of pharyngeal muscles) is unknown. Diphenhydramine gave partial relief, an early clue that tetanus was not the cause of the trismus, which would not have been expected to respond to this agent. The exact reason why diphenhydramine, an anticholinergic drug, resulted in temporary relaxation remained unclear.

Pregabalin is approved for adult partial‐onset epilepsy, diabetic neuropathic pain, post‐herpetic neuralgia and fibromyalgia. Therefore, this case represented an off‐label use of pregabalin. The effectiveness of pregabalin for postoperative pain relief has been studied,2 but its efficacy in other types of pain remains undefined. In our patient, pregabalin did not appear to be effective.

This case to our knowledge represents the first report of pregabalin‐induced trismus in the peer‐reviewed literature, although the manufacturer was apparently aware that this association had been seen on rare occasions. This underscores the fact that prescribers need to be vigilant for potential adverse drug reactions in the post‐marketing period, both those rarely previously reported as well as those previously unreported.

Acknowledgements

Y.L. Kwong: treated the patient, wrote the manuscript, A.Y.H. Leung: treated the patient, and approved the manuscript, R.T.F. Cheung: treated the patient, and approved the manuscript.

- ,.Clostridium tetani in a metropolitan area: a limited survey incorporating a simplified in vitro identification test.Appl Microbiol.1966;14:993–997.

- Available at: http://www.pfizer.com/files/products/uspi_lyrica.pdf, page 18. Accessed March2010.

- .Pregabalin: its pharmacology and use in pain management.Anesth Analg.2007;105:1805–1815.

- ,.Clostridium tetani in a metropolitan area: a limited survey incorporating a simplified in vitro identification test.Appl Microbiol.1966;14:993–997.

- Available at: http://www.pfizer.com/files/products/uspi_lyrica.pdf, page 18. Accessed March2010.

- .Pregabalin: its pharmacology and use in pain management.Anesth Analg.2007;105:1805–1815.

Short Title

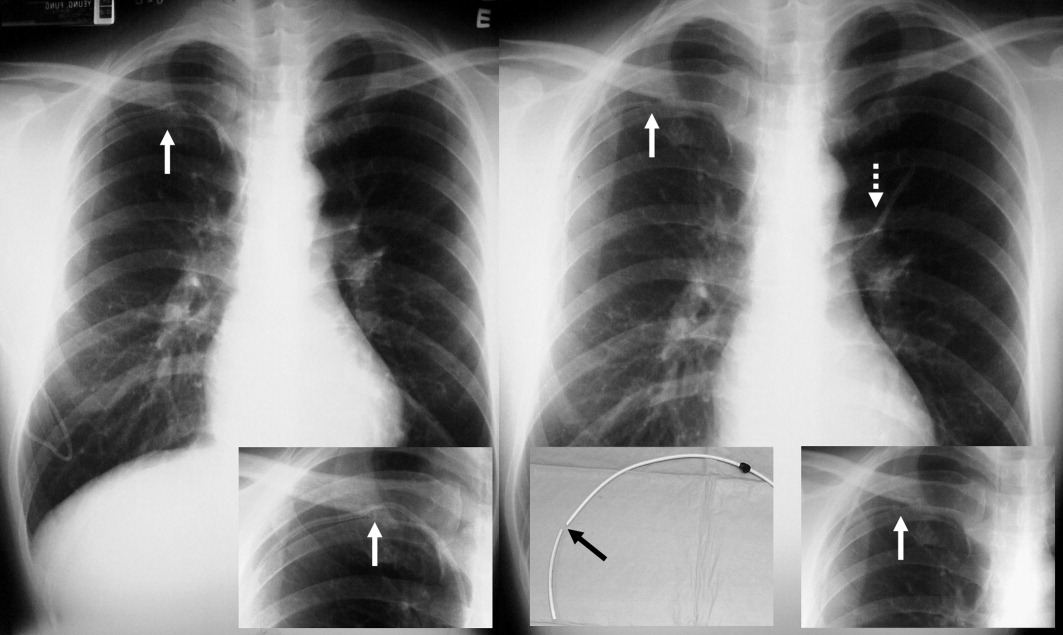

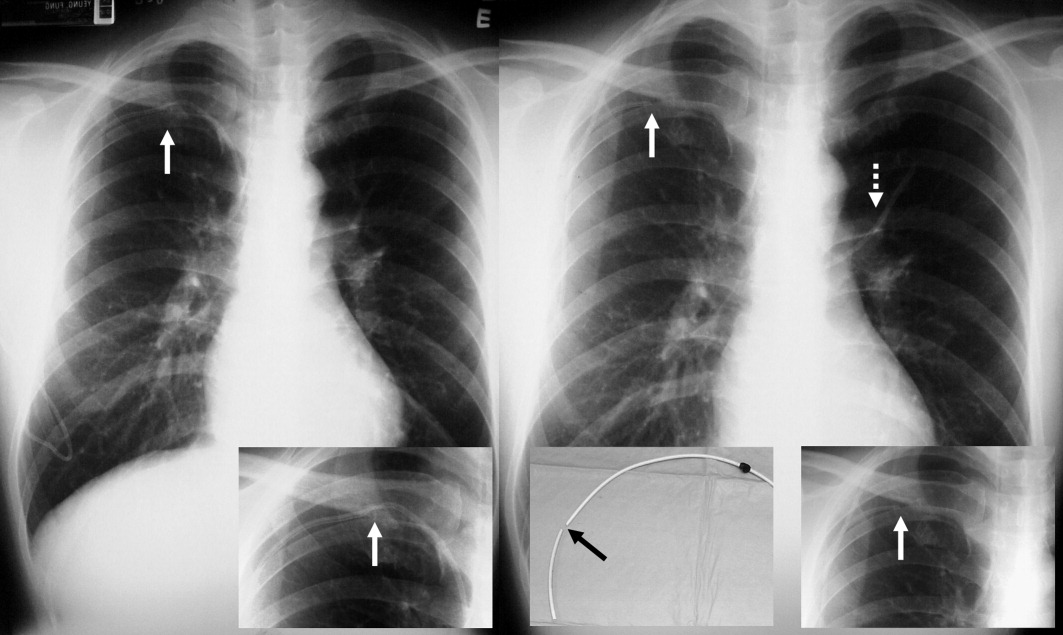

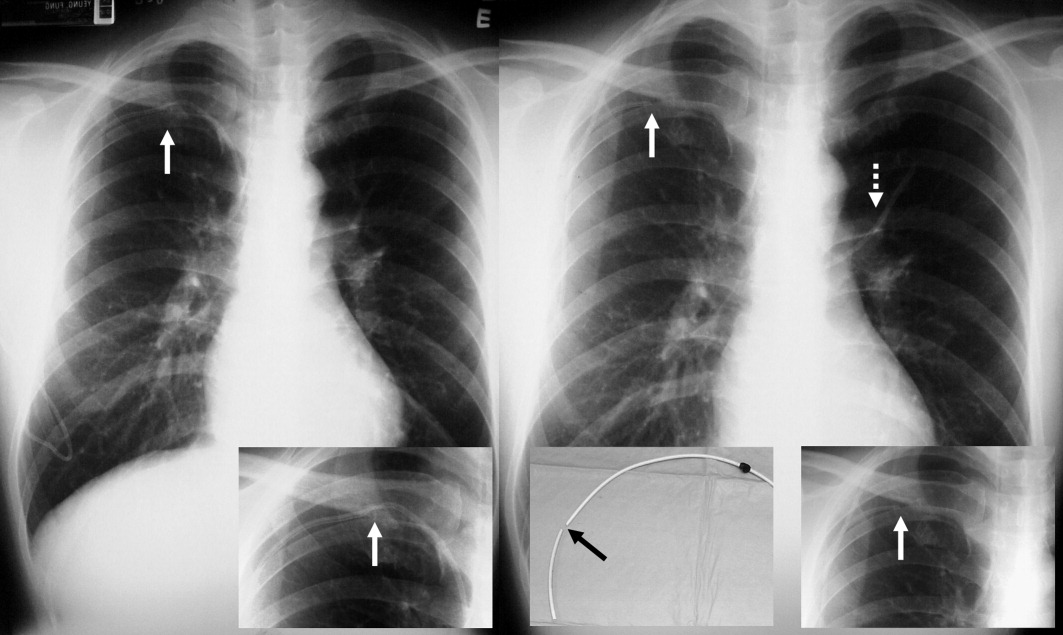

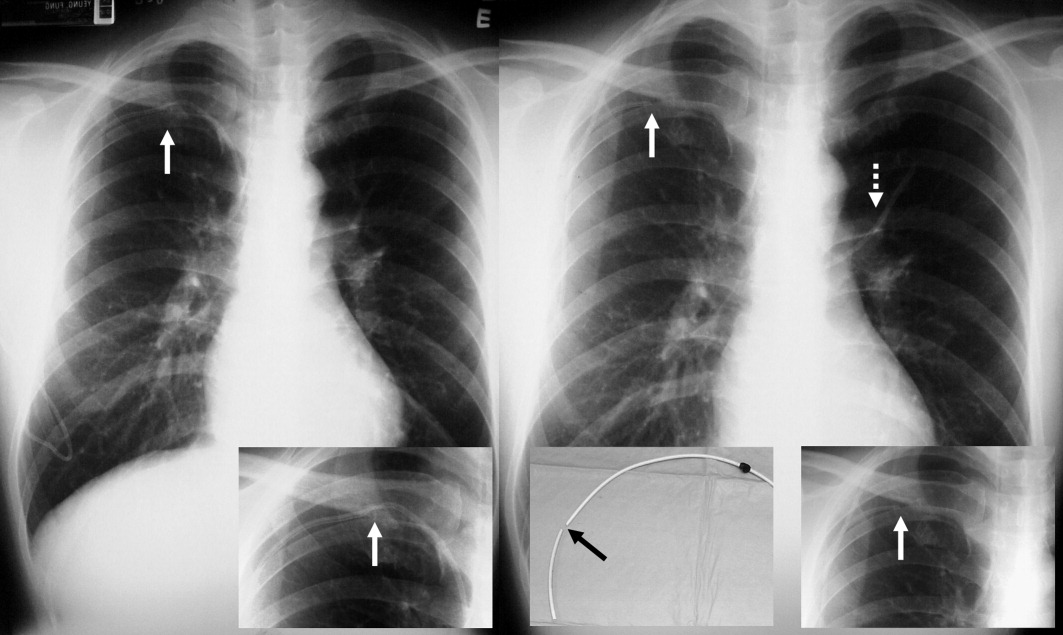

A long‐term tunneled subclavian venous catheter of a 32‐year‐old leukaemia patient blocked. Chest x‐ray (CXR) showed a fracture, with the proximal end underneath the first rib and clavicle (Figure 1, arrow, right panel), and distal fragment at the left hila (broken arrow). A CXR 3 months ago showed catheter kinking and narrowing at the same site, constituting the pinch‐off sign (arrow, left panel).1 The broken fragment was retrieved from the left pulmonary artery by cardiac catheterization. Fractured ends were smooth (central insert).

Spontaneous central venous catheter fracture occurs in 0.1% to 1% of cases.2 The catheter fracture is postulated to be related to compression between the clavicle and first rib due to vigorous movement or heavy object lifting,3 activities that should be avoided. Fractures at other sites are exceptional. The pinch‐off sign may precede fracture; if detected, catheter removal is warranted,4 a fact both clinicians and radiologists should be aware of.

- ,.The “pinch‐off sign”: a warning of impending problems with permanent subclavian catheters.Am J Surg.1984;148:633–636.

- ,,,.Spontaneous leak and transection of permanent subclavian catheters.J Surg Oncol.1998;68:166–168.

- ,,.Pinch‐off syndrome: case report and collective review of the literature.Am Surg.2004;70:635–644.

- ,.Prevention of complications in permanent central venous catheters.Surg Gynecol Obstet.1988;167:6–11.

A long‐term tunneled subclavian venous catheter of a 32‐year‐old leukaemia patient blocked. Chest x‐ray (CXR) showed a fracture, with the proximal end underneath the first rib and clavicle (Figure 1, arrow, right panel), and distal fragment at the left hila (broken arrow). A CXR 3 months ago showed catheter kinking and narrowing at the same site, constituting the pinch‐off sign (arrow, left panel).1 The broken fragment was retrieved from the left pulmonary artery by cardiac catheterization. Fractured ends were smooth (central insert).

Spontaneous central venous catheter fracture occurs in 0.1% to 1% of cases.2 The catheter fracture is postulated to be related to compression between the clavicle and first rib due to vigorous movement or heavy object lifting,3 activities that should be avoided. Fractures at other sites are exceptional. The pinch‐off sign may precede fracture; if detected, catheter removal is warranted,4 a fact both clinicians and radiologists should be aware of.

A long‐term tunneled subclavian venous catheter of a 32‐year‐old leukaemia patient blocked. Chest x‐ray (CXR) showed a fracture, with the proximal end underneath the first rib and clavicle (Figure 1, arrow, right panel), and distal fragment at the left hila (broken arrow). A CXR 3 months ago showed catheter kinking and narrowing at the same site, constituting the pinch‐off sign (arrow, left panel).1 The broken fragment was retrieved from the left pulmonary artery by cardiac catheterization. Fractured ends were smooth (central insert).

Spontaneous central venous catheter fracture occurs in 0.1% to 1% of cases.2 The catheter fracture is postulated to be related to compression between the clavicle and first rib due to vigorous movement or heavy object lifting,3 activities that should be avoided. Fractures at other sites are exceptional. The pinch‐off sign may precede fracture; if detected, catheter removal is warranted,4 a fact both clinicians and radiologists should be aware of.

- ,.The “pinch‐off sign”: a warning of impending problems with permanent subclavian catheters.Am J Surg.1984;148:633–636.

- ,,,.Spontaneous leak and transection of permanent subclavian catheters.J Surg Oncol.1998;68:166–168.

- ,,.Pinch‐off syndrome: case report and collective review of the literature.Am Surg.2004;70:635–644.

- ,.Prevention of complications in permanent central venous catheters.Surg Gynecol Obstet.1988;167:6–11.

- ,.The “pinch‐off sign”: a warning of impending problems with permanent subclavian catheters.Am J Surg.1984;148:633–636.

- ,,,.Spontaneous leak and transection of permanent subclavian catheters.J Surg Oncol.1998;68:166–168.

- ,,.Pinch‐off syndrome: case report and collective review of the literature.Am Surg.2004;70:635–644.

- ,.Prevention of complications in permanent central venous catheters.Surg Gynecol Obstet.1988;167:6–11.