User login

Paranoia and suicidality after starting treatment for lupus

CASE Unusual behavior, thoughts

Mr. L, age 28, an immigrant from Burma, is brought to his primary care physician’s clinic by his wife for follow-up on a rash. During the evaluation, his wife reports that Mr. L recently has had suicidal ideation, depression, and increased anger. She says Mr. L had made statements about wanting to kill himself with a gun. Mr. L had driven his car to a soccer field with a knife in hand and was contemplating suicide. She is concerned about her own safety and their children’s safety because of Mr. L’s anger. The physician refers Mr. L to the emergency department, and he is admitted to the medical floor for a rheumatological flare-up and suicidal ideation.

Mr. L starts displaying inappropriate behaviors, including masturbating in front of the patient safety attendant, telling the attendant “You are going to die today,” and assaulting a female attendant by trying to grab her breasts. He is given IM haloperidol, 2 mg, which effectively alleviates these behaviors. Between episodes of unusual behavior and outbursts, Mr. L is docile, quiet, and cooperative, and denies any memory of these episodes.

One month earlier, Mr. L had been hospitalized for progressive weakness and inability to ambulate. He was diagnosed with necrotizing myositis and a rash consistent with subacute cutaneous lupus. He was started on IV methylprednisolone, 1 g, and transitioned to oral prednisolone, 40 mg/d, which he continued taking after discharge. He also started taking azathioprine, which was increased from 50 to 100 mg/d. His condition improved shortly after beginning this regimen.

[polldaddy:9796586]

The authors’ observations

DSM-5 defines brief psychotic disorder as positive symptoms or disorganized or catatonic behavior appearing suddenly and lasting between 1 day to 1 month.1 Mr. L had a sudden onset of his symptoms and marked stressors as a result of his worsening health. However, the possibility of his general medical conditions or medications causing his symptoms needed to be investigated and ruled out before this diagnosis could be assigned.

Another consideration is the culture-bound syndrome amok. Although DSM-5 does not use the term “culture-bound syndrome,” which was used in DSM-IV, it does recognize cultural conceptualizations of distress. Amok is described as a dissociative episode in which an individual has a period of brooding followed by outbursts that include violent, aggressive, and suicidal and/or homicidal ideation. The individual may exhibit persecutory and paranoid thinking, amnesia of the outbursts, and a return to typical behavior when the episode concludes.2 However, it remained unclear whether Mr. L’s violent behavior was a manifestation of psychiatric or organic disease.

Identifying the possibility of amok is important not only for alleviating the patient’s distress but also for preventing violent outbursts that can result in injury or death.3 Amok should be considered only in the context of possible psychiatric or organic brain disease, such as corticosteroid-induced psychosis (CIP) or systemic lupus erythematosus-induced psychosis (SLEIP).4

EVALUATION Informants, labs

Mr. L immigrated to the United States when he was 5 years old. He does not speak English, and interviews are conducted with interpreting services at the hospital. Mr. L answers most questions with or 1 to 2 words. His medical and psychiatric histories are notable for hypothyroidism, hepatitis, non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, necrotizing myositis, subacute cutaneous lupus, and depression. Mr. L denies a personal or family history of mental illness; however, records show he has a history of unspecified depressive disorder.

Mr. L reports his current mood is “okay,” but he has felt different in the past few weeks. He denies auditory or visual hallucinations, or suicidal or homicidal ideation, but exhibits paranoid thoughts. Mr. L believes everyone “lied” to him, and he repeats this frequently. Collateral information from friends reveals that he had threatened to burn down their houses. A family friend states that Mr. L has been depressed and angry over the past 5 days.

During his prior and current hospitalizations, many labs were completed. Thyroid, urine drug screen, C-reactive protein, urine analysis, ethanol, complete blood count, and comprehensive metabolic panel were negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 30. Lumbar puncture cell count was notable for mildly elevated lymphocytes at 84%. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) was positive. Lupus anticoagulant panel revealed a mildly prolonged partial thromboplastin time at 38.9 seconds. DNA double-stranded antibody (anti-dsDNA) was positive. Anti-Smith antibody was negative. Anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies were elevated. Albumin was low. A MRI of the brain showed dystrophic-appearing right parieto-occipital calcification and mild cerebral volume loss.

Based on Mr. L’s presentation and imaging, the rheumatology team suspects CNS lupus and that his prescribed steroids could be playing a role in his behavior.

The authors’ observations

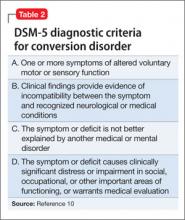

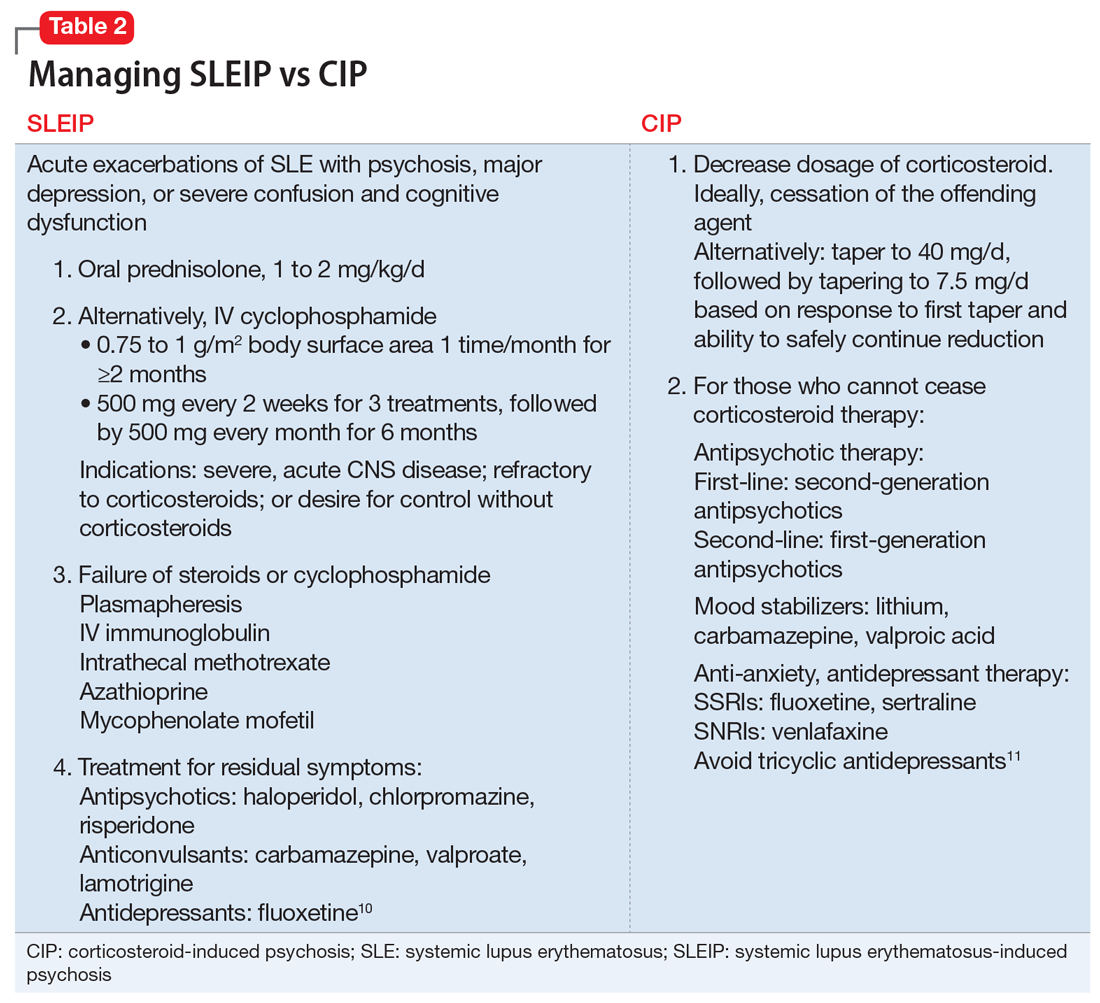

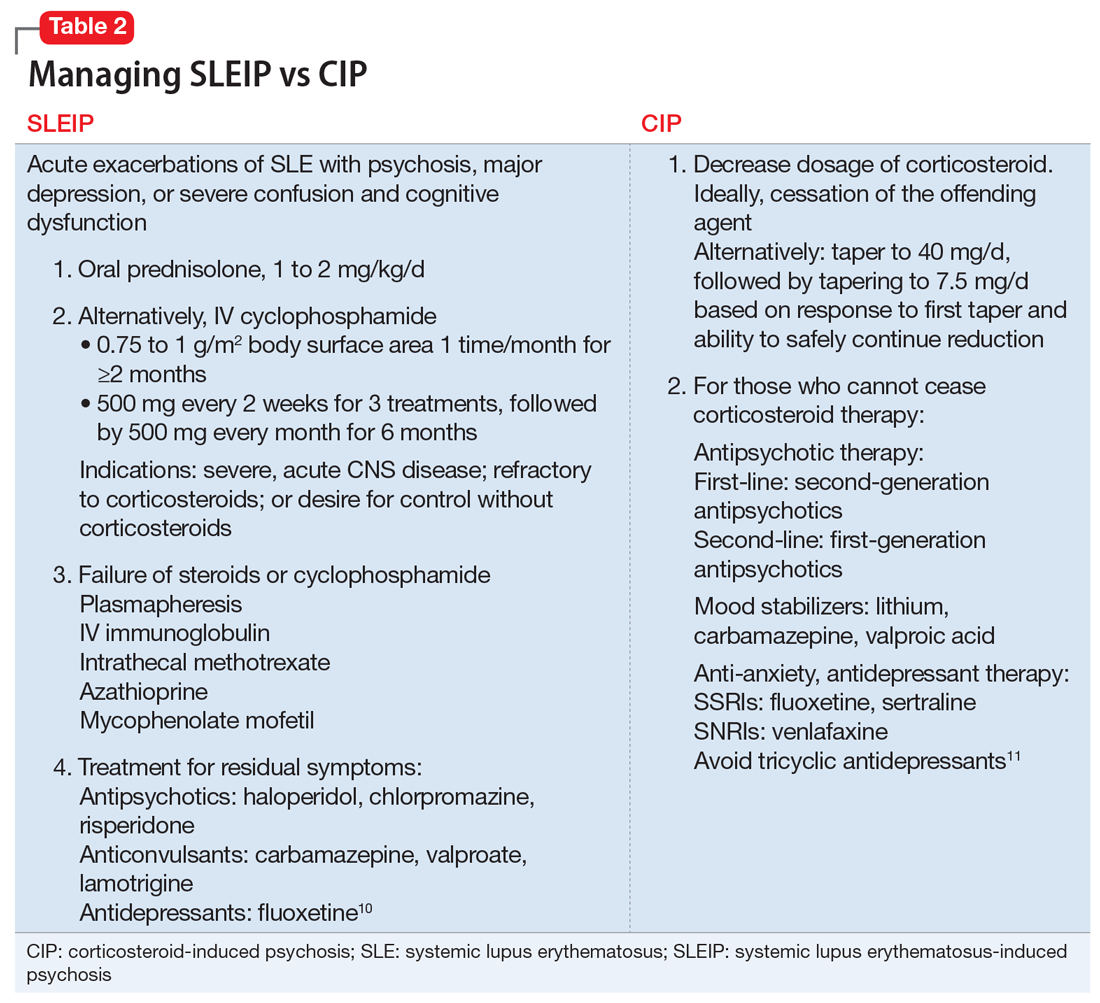

Differentiating CIP from SLEIP can be difficult. The clinical features and criteria for CIP and SLEIP are listed in Table 1.5-7 Several studies have highlighted the difficulties in separating the 2 diagnoses:

- Kampylafka et al8 found that CNS involvement, including stroke, myelopathy, seizures, optic neuritis, and meningitis, was present in 4.3% of their sample of patients with systematic lupus erythematosus (SLE), of whom 6.3% presented with SLEIP. Of patients with CNS involvement, 94% had positive ANA and 69% had positive anti-dsDNA antibodies. It remains difficult to definitively diagnose SLEIP rather than CIP, however, because 100% of patients in this study were taking corticosteroids, with 25% taking azathioprine, as was Mr. L.8

- Appenzeller et al9 found that acute psychosis was associated with SLE in 11.3% of their sample. Psychosis in patients with SLE was accompanied by other manifestations of CNS involvement. On follow-up these patients had mild increases in white blood cell count in their CSF, and MRI demonstrated hyperdense lesions and cerebral atrophy. Hypoalbuminemia, although often seen in SLEIP, also is observed in patients with CIP and cannot be used to differentiate these 2 conditions.9

- Monov and Monova5 recommended criteria for SLEIP that include 3 stages. The first stage is determining that there is evidence of an exacerbation of SLE, and ruling out other causes for neurologic and psychiatric symptoms. The second stage involves using clinical, laboratory, or imaging tests to define the lesion as central and/or peripheral and diffuse and/or focal. The third stage requires diagnosing SLEIP using criteria from 2 groups of signs and symptoms: the first group includes seizure, psychosis, cerebrovascular event, lesion of cranial nerves, and quantitative alterations of consciousness; the second group includes cognitive dysfunction, lupus headache, peripheral neuropathy, MRI changes, EEG changes, electroneuromyography changes, and a positive replication protein A or antiphospholipid-positive antibody. Diagnosing SLEIP requires ≥1 criterion from group 1 and ≥2 criteria from group 2.5

- Patten and Neutel6 found that patients taking prednisolone, Symbol Std<40 mg/d, had significantly higher rates of psychosis than those taking <40 mg/d.6

- Bhangle et Myriad Proal7 found that one of the major distinguishing factors between CIP and SLEIP is the timing of the onset of symptoms, with CIP occurring within 8 weeks of initiation of a corticosteroid, and SLEIP being more likely to occur when additional CNS symptoms are present.7

TREATMENT Decreased dosage

Mr. L starts quetiapine, 25 mg at bedtime, increased to 75 mg at bedtime. Prednisolone is decreased to 10 mg/d. Over the next few days Mr. L’s mood, psychosis, and aggression improve. He becomes calm and cooperative, and denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. Mr. L’s wife, who was initially scared to visit him, comes to see him and confirms that he has improved. After 3 consecutive days with no abnormal behaviors or psychiatric symptoms, Mr. L is discharged and continues taking quetiapine, 75 mg at bedtime, and prednisolone, 10 mg/d, with outpatient follow-up.

The authors’ observations

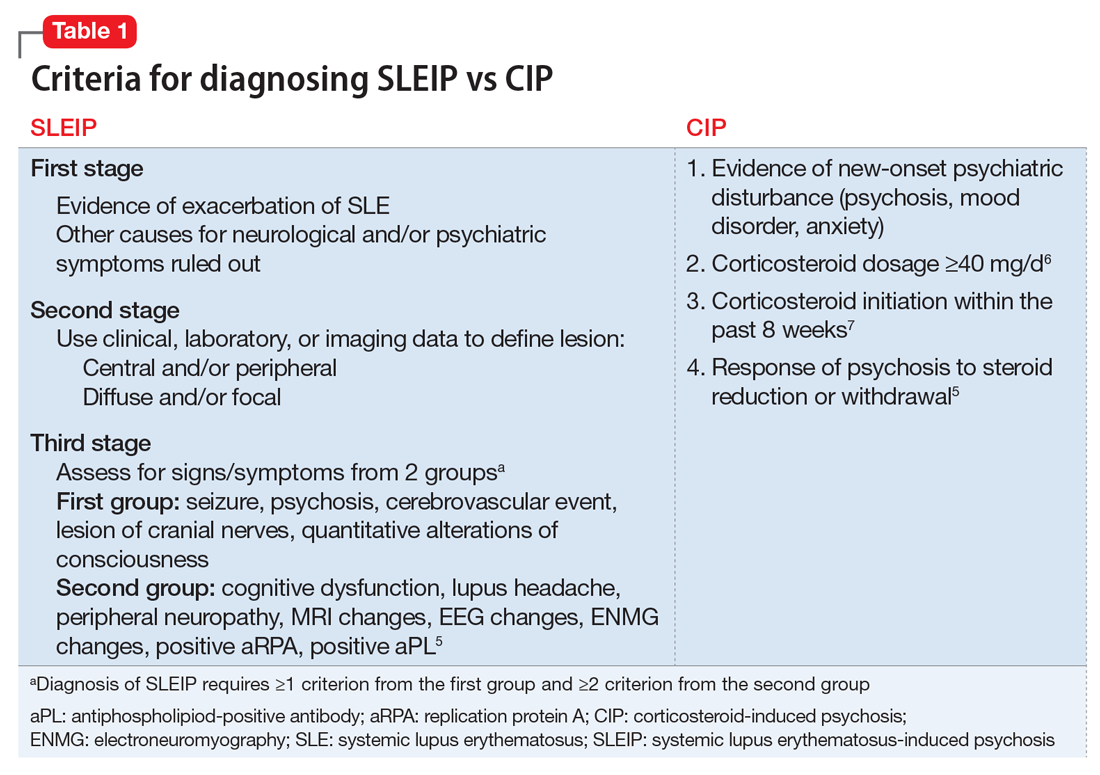

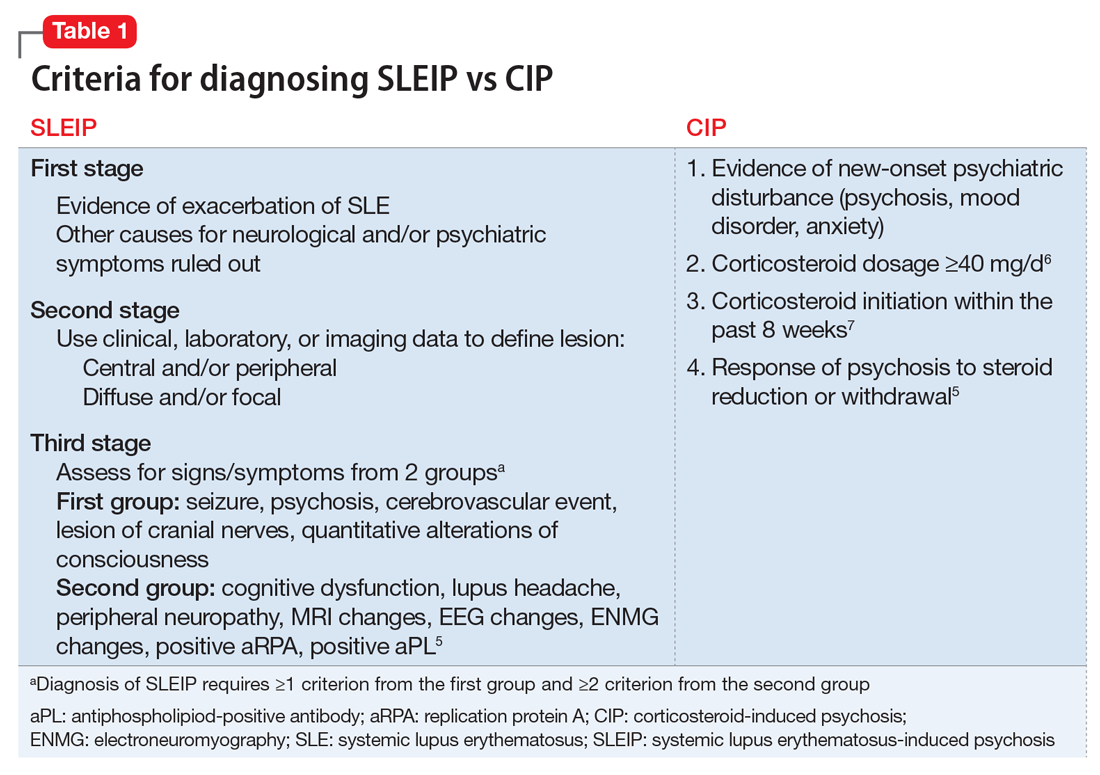

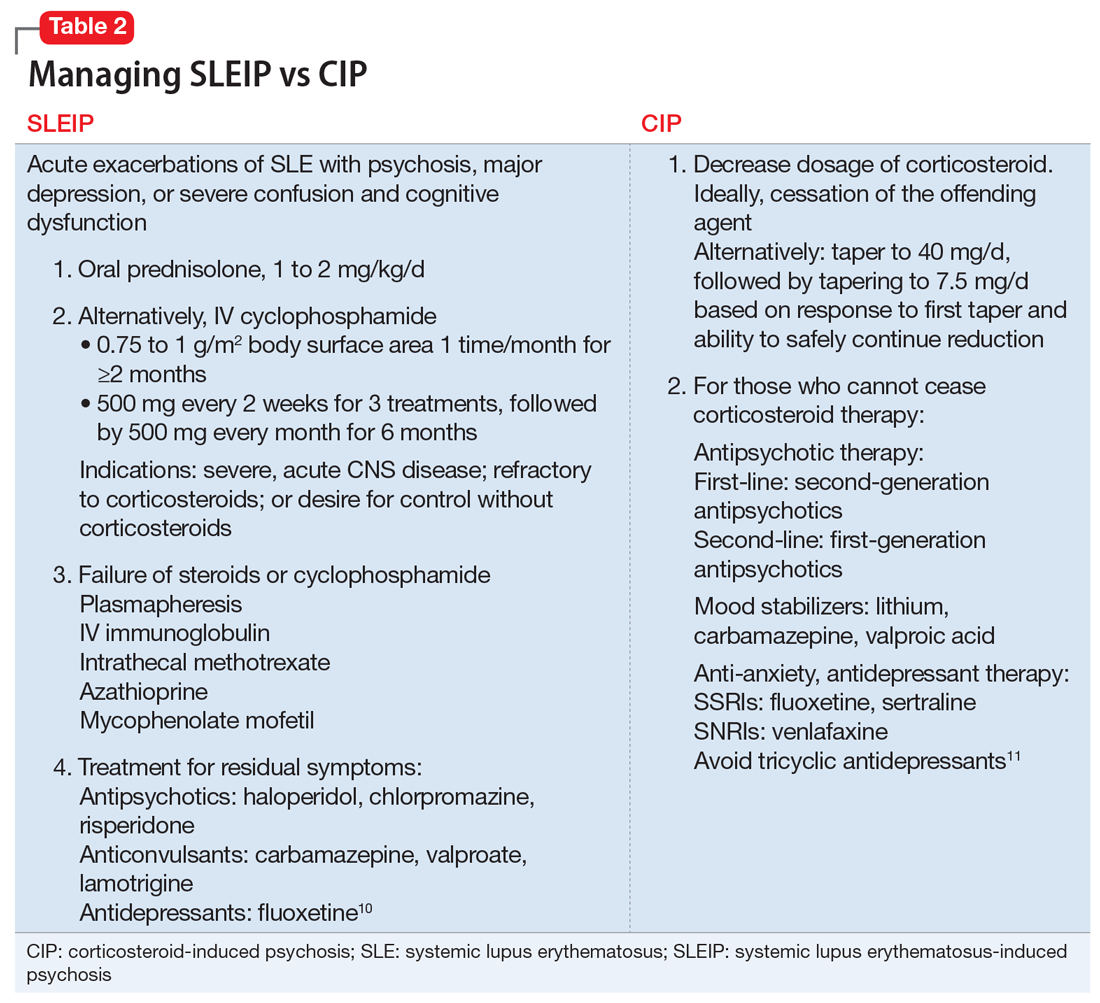

Table 210,11 describes approaches to treating CIP and SLEIP. Managing CIP typically consists of reducing the corticosteroid dosage. CIP treatment also includes adjunct therapy with psychotropics if the corticosteroid dose cannot be lowered enough to reduce psychiatric symptoms while suppressing symptoms of the disease for which the corticosteroid was prescribed.6

When treating SLEIP, the corticosteroid dosage often is increased. Corticosteroids often are used to treat SLEIP while suppressing symptoms of SLE.10 The main treatment of SLEIP is focused on the disease and using psychotropic medications to control symptoms that don’t respond after exacerbation of the disease has been controlled.10

The presence of Mr. L’s multiple SLE symptoms, as well as MRI findings, could indicate SLEIP. However, corticosteroids also were a possible cause of his psychotic symptoms. Mr. L’s psychosis began within 8 weeks of starting a corticosteroid (prednisolone, 40 mg/d), and his symptoms improved when the corticosteroid dosage was reduced. The difference between CIP and SLEIP may best be distinguished by reducing the corticosteroid dosage and seeing if psychotic symptoms improve. Because it is important to control SLE symptoms in those with CIP, prescribing psychotropics may be warranted, as well as alternative treatments for immunosuppression.

Because steroids are frequently prescribed for lupus, it is important for clinicians to be aware of their psychiatric effects as well as how to manage those effects. When distinguishing CIP from SLEIP, consider decreasing the corticosteroid dosage and see if psychotic symptoms improve. Use adjunct therapy as needed.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Saint Martin ML. Running amok: A modern perspective on a culture-bound syndrome. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1(3):66-70.

4. Flaskerud JH. Case studies in amok? Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33(12):898-900.

5. Monov S, Monova D. Classification criteria for neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus: do they need a discussion? Hippokratia. 2008;12(2):103-107.

6. Patten SB, Neutel CI. Corticosteroid-induced adverse psychiatric effects: incidence, diagnosis and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22(2):111-122.

7. Bhangle SD, Kramer N, Rosenstein, ED. Corticosteroid-induced neuropsychiatric disorders: review and contrast with neuropsychiatric lupus. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(8):1923-1932.

8. Kampylafka EI, Alexopoulos H, Kosmidis ML, et al. Incidence and prevalence of major central nervous system involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: a 3-year prospective study of 370 patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55843. d

9. Appenzeller S, Cendes F, Costallat LT. Acute psychosisin systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2008;28(3):237-243.

10. Sanna G, Bertolaccini ML, Khamashta MA. Neuropsychiatric involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: current therapeutic approach. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(13):1261-1269.

11. Warrington TP, Bostwick JM. Psychiatric adverse effects of corticosteroids. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(10):1361-1367.

CASE Unusual behavior, thoughts

Mr. L, age 28, an immigrant from Burma, is brought to his primary care physician’s clinic by his wife for follow-up on a rash. During the evaluation, his wife reports that Mr. L recently has had suicidal ideation, depression, and increased anger. She says Mr. L had made statements about wanting to kill himself with a gun. Mr. L had driven his car to a soccer field with a knife in hand and was contemplating suicide. She is concerned about her own safety and their children’s safety because of Mr. L’s anger. The physician refers Mr. L to the emergency department, and he is admitted to the medical floor for a rheumatological flare-up and suicidal ideation.

Mr. L starts displaying inappropriate behaviors, including masturbating in front of the patient safety attendant, telling the attendant “You are going to die today,” and assaulting a female attendant by trying to grab her breasts. He is given IM haloperidol, 2 mg, which effectively alleviates these behaviors. Between episodes of unusual behavior and outbursts, Mr. L is docile, quiet, and cooperative, and denies any memory of these episodes.

One month earlier, Mr. L had been hospitalized for progressive weakness and inability to ambulate. He was diagnosed with necrotizing myositis and a rash consistent with subacute cutaneous lupus. He was started on IV methylprednisolone, 1 g, and transitioned to oral prednisolone, 40 mg/d, which he continued taking after discharge. He also started taking azathioprine, which was increased from 50 to 100 mg/d. His condition improved shortly after beginning this regimen.

[polldaddy:9796586]

The authors’ observations

DSM-5 defines brief psychotic disorder as positive symptoms or disorganized or catatonic behavior appearing suddenly and lasting between 1 day to 1 month.1 Mr. L had a sudden onset of his symptoms and marked stressors as a result of his worsening health. However, the possibility of his general medical conditions or medications causing his symptoms needed to be investigated and ruled out before this diagnosis could be assigned.

Another consideration is the culture-bound syndrome amok. Although DSM-5 does not use the term “culture-bound syndrome,” which was used in DSM-IV, it does recognize cultural conceptualizations of distress. Amok is described as a dissociative episode in which an individual has a period of brooding followed by outbursts that include violent, aggressive, and suicidal and/or homicidal ideation. The individual may exhibit persecutory and paranoid thinking, amnesia of the outbursts, and a return to typical behavior when the episode concludes.2 However, it remained unclear whether Mr. L’s violent behavior was a manifestation of psychiatric or organic disease.

Identifying the possibility of amok is important not only for alleviating the patient’s distress but also for preventing violent outbursts that can result in injury or death.3 Amok should be considered only in the context of possible psychiatric or organic brain disease, such as corticosteroid-induced psychosis (CIP) or systemic lupus erythematosus-induced psychosis (SLEIP).4

EVALUATION Informants, labs

Mr. L immigrated to the United States when he was 5 years old. He does not speak English, and interviews are conducted with interpreting services at the hospital. Mr. L answers most questions with or 1 to 2 words. His medical and psychiatric histories are notable for hypothyroidism, hepatitis, non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, necrotizing myositis, subacute cutaneous lupus, and depression. Mr. L denies a personal or family history of mental illness; however, records show he has a history of unspecified depressive disorder.

Mr. L reports his current mood is “okay,” but he has felt different in the past few weeks. He denies auditory or visual hallucinations, or suicidal or homicidal ideation, but exhibits paranoid thoughts. Mr. L believes everyone “lied” to him, and he repeats this frequently. Collateral information from friends reveals that he had threatened to burn down their houses. A family friend states that Mr. L has been depressed and angry over the past 5 days.

During his prior and current hospitalizations, many labs were completed. Thyroid, urine drug screen, C-reactive protein, urine analysis, ethanol, complete blood count, and comprehensive metabolic panel were negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 30. Lumbar puncture cell count was notable for mildly elevated lymphocytes at 84%. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) was positive. Lupus anticoagulant panel revealed a mildly prolonged partial thromboplastin time at 38.9 seconds. DNA double-stranded antibody (anti-dsDNA) was positive. Anti-Smith antibody was negative. Anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies were elevated. Albumin was low. A MRI of the brain showed dystrophic-appearing right parieto-occipital calcification and mild cerebral volume loss.

Based on Mr. L’s presentation and imaging, the rheumatology team suspects CNS lupus and that his prescribed steroids could be playing a role in his behavior.

The authors’ observations

Differentiating CIP from SLEIP can be difficult. The clinical features and criteria for CIP and SLEIP are listed in Table 1.5-7 Several studies have highlighted the difficulties in separating the 2 diagnoses:

- Kampylafka et al8 found that CNS involvement, including stroke, myelopathy, seizures, optic neuritis, and meningitis, was present in 4.3% of their sample of patients with systematic lupus erythematosus (SLE), of whom 6.3% presented with SLEIP. Of patients with CNS involvement, 94% had positive ANA and 69% had positive anti-dsDNA antibodies. It remains difficult to definitively diagnose SLEIP rather than CIP, however, because 100% of patients in this study were taking corticosteroids, with 25% taking azathioprine, as was Mr. L.8

- Appenzeller et al9 found that acute psychosis was associated with SLE in 11.3% of their sample. Psychosis in patients with SLE was accompanied by other manifestations of CNS involvement. On follow-up these patients had mild increases in white blood cell count in their CSF, and MRI demonstrated hyperdense lesions and cerebral atrophy. Hypoalbuminemia, although often seen in SLEIP, also is observed in patients with CIP and cannot be used to differentiate these 2 conditions.9

- Monov and Monova5 recommended criteria for SLEIP that include 3 stages. The first stage is determining that there is evidence of an exacerbation of SLE, and ruling out other causes for neurologic and psychiatric symptoms. The second stage involves using clinical, laboratory, or imaging tests to define the lesion as central and/or peripheral and diffuse and/or focal. The third stage requires diagnosing SLEIP using criteria from 2 groups of signs and symptoms: the first group includes seizure, psychosis, cerebrovascular event, lesion of cranial nerves, and quantitative alterations of consciousness; the second group includes cognitive dysfunction, lupus headache, peripheral neuropathy, MRI changes, EEG changes, electroneuromyography changes, and a positive replication protein A or antiphospholipid-positive antibody. Diagnosing SLEIP requires ≥1 criterion from group 1 and ≥2 criteria from group 2.5

- Patten and Neutel6 found that patients taking prednisolone, Symbol Std<40 mg/d, had significantly higher rates of psychosis than those taking <40 mg/d.6

- Bhangle et Myriad Proal7 found that one of the major distinguishing factors between CIP and SLEIP is the timing of the onset of symptoms, with CIP occurring within 8 weeks of initiation of a corticosteroid, and SLEIP being more likely to occur when additional CNS symptoms are present.7

TREATMENT Decreased dosage

Mr. L starts quetiapine, 25 mg at bedtime, increased to 75 mg at bedtime. Prednisolone is decreased to 10 mg/d. Over the next few days Mr. L’s mood, psychosis, and aggression improve. He becomes calm and cooperative, and denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. Mr. L’s wife, who was initially scared to visit him, comes to see him and confirms that he has improved. After 3 consecutive days with no abnormal behaviors or psychiatric symptoms, Mr. L is discharged and continues taking quetiapine, 75 mg at bedtime, and prednisolone, 10 mg/d, with outpatient follow-up.

The authors’ observations

Table 210,11 describes approaches to treating CIP and SLEIP. Managing CIP typically consists of reducing the corticosteroid dosage. CIP treatment also includes adjunct therapy with psychotropics if the corticosteroid dose cannot be lowered enough to reduce psychiatric symptoms while suppressing symptoms of the disease for which the corticosteroid was prescribed.6

When treating SLEIP, the corticosteroid dosage often is increased. Corticosteroids often are used to treat SLEIP while suppressing symptoms of SLE.10 The main treatment of SLEIP is focused on the disease and using psychotropic medications to control symptoms that don’t respond after exacerbation of the disease has been controlled.10

The presence of Mr. L’s multiple SLE symptoms, as well as MRI findings, could indicate SLEIP. However, corticosteroids also were a possible cause of his psychotic symptoms. Mr. L’s psychosis began within 8 weeks of starting a corticosteroid (prednisolone, 40 mg/d), and his symptoms improved when the corticosteroid dosage was reduced. The difference between CIP and SLEIP may best be distinguished by reducing the corticosteroid dosage and seeing if psychotic symptoms improve. Because it is important to control SLE symptoms in those with CIP, prescribing psychotropics may be warranted, as well as alternative treatments for immunosuppression.

Because steroids are frequently prescribed for lupus, it is important for clinicians to be aware of their psychiatric effects as well as how to manage those effects. When distinguishing CIP from SLEIP, consider decreasing the corticosteroid dosage and see if psychotic symptoms improve. Use adjunct therapy as needed.

CASE Unusual behavior, thoughts

Mr. L, age 28, an immigrant from Burma, is brought to his primary care physician’s clinic by his wife for follow-up on a rash. During the evaluation, his wife reports that Mr. L recently has had suicidal ideation, depression, and increased anger. She says Mr. L had made statements about wanting to kill himself with a gun. Mr. L had driven his car to a soccer field with a knife in hand and was contemplating suicide. She is concerned about her own safety and their children’s safety because of Mr. L’s anger. The physician refers Mr. L to the emergency department, and he is admitted to the medical floor for a rheumatological flare-up and suicidal ideation.

Mr. L starts displaying inappropriate behaviors, including masturbating in front of the patient safety attendant, telling the attendant “You are going to die today,” and assaulting a female attendant by trying to grab her breasts. He is given IM haloperidol, 2 mg, which effectively alleviates these behaviors. Between episodes of unusual behavior and outbursts, Mr. L is docile, quiet, and cooperative, and denies any memory of these episodes.

One month earlier, Mr. L had been hospitalized for progressive weakness and inability to ambulate. He was diagnosed with necrotizing myositis and a rash consistent with subacute cutaneous lupus. He was started on IV methylprednisolone, 1 g, and transitioned to oral prednisolone, 40 mg/d, which he continued taking after discharge. He also started taking azathioprine, which was increased from 50 to 100 mg/d. His condition improved shortly after beginning this regimen.

[polldaddy:9796586]

The authors’ observations

DSM-5 defines brief psychotic disorder as positive symptoms or disorganized or catatonic behavior appearing suddenly and lasting between 1 day to 1 month.1 Mr. L had a sudden onset of his symptoms and marked stressors as a result of his worsening health. However, the possibility of his general medical conditions or medications causing his symptoms needed to be investigated and ruled out before this diagnosis could be assigned.

Another consideration is the culture-bound syndrome amok. Although DSM-5 does not use the term “culture-bound syndrome,” which was used in DSM-IV, it does recognize cultural conceptualizations of distress. Amok is described as a dissociative episode in which an individual has a period of brooding followed by outbursts that include violent, aggressive, and suicidal and/or homicidal ideation. The individual may exhibit persecutory and paranoid thinking, amnesia of the outbursts, and a return to typical behavior when the episode concludes.2 However, it remained unclear whether Mr. L’s violent behavior was a manifestation of psychiatric or organic disease.

Identifying the possibility of amok is important not only for alleviating the patient’s distress but also for preventing violent outbursts that can result in injury or death.3 Amok should be considered only in the context of possible psychiatric or organic brain disease, such as corticosteroid-induced psychosis (CIP) or systemic lupus erythematosus-induced psychosis (SLEIP).4

EVALUATION Informants, labs

Mr. L immigrated to the United States when he was 5 years old. He does not speak English, and interviews are conducted with interpreting services at the hospital. Mr. L answers most questions with or 1 to 2 words. His medical and psychiatric histories are notable for hypothyroidism, hepatitis, non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, necrotizing myositis, subacute cutaneous lupus, and depression. Mr. L denies a personal or family history of mental illness; however, records show he has a history of unspecified depressive disorder.

Mr. L reports his current mood is “okay,” but he has felt different in the past few weeks. He denies auditory or visual hallucinations, or suicidal or homicidal ideation, but exhibits paranoid thoughts. Mr. L believes everyone “lied” to him, and he repeats this frequently. Collateral information from friends reveals that he had threatened to burn down their houses. A family friend states that Mr. L has been depressed and angry over the past 5 days.

During his prior and current hospitalizations, many labs were completed. Thyroid, urine drug screen, C-reactive protein, urine analysis, ethanol, complete blood count, and comprehensive metabolic panel were negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 30. Lumbar puncture cell count was notable for mildly elevated lymphocytes at 84%. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) was positive. Lupus anticoagulant panel revealed a mildly prolonged partial thromboplastin time at 38.9 seconds. DNA double-stranded antibody (anti-dsDNA) was positive. Anti-Smith antibody was negative. Anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies were elevated. Albumin was low. A MRI of the brain showed dystrophic-appearing right parieto-occipital calcification and mild cerebral volume loss.

Based on Mr. L’s presentation and imaging, the rheumatology team suspects CNS lupus and that his prescribed steroids could be playing a role in his behavior.

The authors’ observations

Differentiating CIP from SLEIP can be difficult. The clinical features and criteria for CIP and SLEIP are listed in Table 1.5-7 Several studies have highlighted the difficulties in separating the 2 diagnoses:

- Kampylafka et al8 found that CNS involvement, including stroke, myelopathy, seizures, optic neuritis, and meningitis, was present in 4.3% of their sample of patients with systematic lupus erythematosus (SLE), of whom 6.3% presented with SLEIP. Of patients with CNS involvement, 94% had positive ANA and 69% had positive anti-dsDNA antibodies. It remains difficult to definitively diagnose SLEIP rather than CIP, however, because 100% of patients in this study were taking corticosteroids, with 25% taking azathioprine, as was Mr. L.8

- Appenzeller et al9 found that acute psychosis was associated with SLE in 11.3% of their sample. Psychosis in patients with SLE was accompanied by other manifestations of CNS involvement. On follow-up these patients had mild increases in white blood cell count in their CSF, and MRI demonstrated hyperdense lesions and cerebral atrophy. Hypoalbuminemia, although often seen in SLEIP, also is observed in patients with CIP and cannot be used to differentiate these 2 conditions.9

- Monov and Monova5 recommended criteria for SLEIP that include 3 stages. The first stage is determining that there is evidence of an exacerbation of SLE, and ruling out other causes for neurologic and psychiatric symptoms. The second stage involves using clinical, laboratory, or imaging tests to define the lesion as central and/or peripheral and diffuse and/or focal. The third stage requires diagnosing SLEIP using criteria from 2 groups of signs and symptoms: the first group includes seizure, psychosis, cerebrovascular event, lesion of cranial nerves, and quantitative alterations of consciousness; the second group includes cognitive dysfunction, lupus headache, peripheral neuropathy, MRI changes, EEG changes, electroneuromyography changes, and a positive replication protein A or antiphospholipid-positive antibody. Diagnosing SLEIP requires ≥1 criterion from group 1 and ≥2 criteria from group 2.5

- Patten and Neutel6 found that patients taking prednisolone, Symbol Std<40 mg/d, had significantly higher rates of psychosis than those taking <40 mg/d.6

- Bhangle et Myriad Proal7 found that one of the major distinguishing factors between CIP and SLEIP is the timing of the onset of symptoms, with CIP occurring within 8 weeks of initiation of a corticosteroid, and SLEIP being more likely to occur when additional CNS symptoms are present.7

TREATMENT Decreased dosage

Mr. L starts quetiapine, 25 mg at bedtime, increased to 75 mg at bedtime. Prednisolone is decreased to 10 mg/d. Over the next few days Mr. L’s mood, psychosis, and aggression improve. He becomes calm and cooperative, and denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. Mr. L’s wife, who was initially scared to visit him, comes to see him and confirms that he has improved. After 3 consecutive days with no abnormal behaviors or psychiatric symptoms, Mr. L is discharged and continues taking quetiapine, 75 mg at bedtime, and prednisolone, 10 mg/d, with outpatient follow-up.

The authors’ observations

Table 210,11 describes approaches to treating CIP and SLEIP. Managing CIP typically consists of reducing the corticosteroid dosage. CIP treatment also includes adjunct therapy with psychotropics if the corticosteroid dose cannot be lowered enough to reduce psychiatric symptoms while suppressing symptoms of the disease for which the corticosteroid was prescribed.6

When treating SLEIP, the corticosteroid dosage often is increased. Corticosteroids often are used to treat SLEIP while suppressing symptoms of SLE.10 The main treatment of SLEIP is focused on the disease and using psychotropic medications to control symptoms that don’t respond after exacerbation of the disease has been controlled.10

The presence of Mr. L’s multiple SLE symptoms, as well as MRI findings, could indicate SLEIP. However, corticosteroids also were a possible cause of his psychotic symptoms. Mr. L’s psychosis began within 8 weeks of starting a corticosteroid (prednisolone, 40 mg/d), and his symptoms improved when the corticosteroid dosage was reduced. The difference between CIP and SLEIP may best be distinguished by reducing the corticosteroid dosage and seeing if psychotic symptoms improve. Because it is important to control SLE symptoms in those with CIP, prescribing psychotropics may be warranted, as well as alternative treatments for immunosuppression.

Because steroids are frequently prescribed for lupus, it is important for clinicians to be aware of their psychiatric effects as well as how to manage those effects. When distinguishing CIP from SLEIP, consider decreasing the corticosteroid dosage and see if psychotic symptoms improve. Use adjunct therapy as needed.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Saint Martin ML. Running amok: A modern perspective on a culture-bound syndrome. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1(3):66-70.

4. Flaskerud JH. Case studies in amok? Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33(12):898-900.

5. Monov S, Monova D. Classification criteria for neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus: do they need a discussion? Hippokratia. 2008;12(2):103-107.

6. Patten SB, Neutel CI. Corticosteroid-induced adverse psychiatric effects: incidence, diagnosis and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22(2):111-122.

7. Bhangle SD, Kramer N, Rosenstein, ED. Corticosteroid-induced neuropsychiatric disorders: review and contrast with neuropsychiatric lupus. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(8):1923-1932.

8. Kampylafka EI, Alexopoulos H, Kosmidis ML, et al. Incidence and prevalence of major central nervous system involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: a 3-year prospective study of 370 patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55843. d

9. Appenzeller S, Cendes F, Costallat LT. Acute psychosisin systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2008;28(3):237-243.

10. Sanna G, Bertolaccini ML, Khamashta MA. Neuropsychiatric involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: current therapeutic approach. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(13):1261-1269.

11. Warrington TP, Bostwick JM. Psychiatric adverse effects of corticosteroids. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(10):1361-1367.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Saint Martin ML. Running amok: A modern perspective on a culture-bound syndrome. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1(3):66-70.

4. Flaskerud JH. Case studies in amok? Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33(12):898-900.

5. Monov S, Monova D. Classification criteria for neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus: do they need a discussion? Hippokratia. 2008;12(2):103-107.

6. Patten SB, Neutel CI. Corticosteroid-induced adverse psychiatric effects: incidence, diagnosis and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22(2):111-122.

7. Bhangle SD, Kramer N, Rosenstein, ED. Corticosteroid-induced neuropsychiatric disorders: review and contrast with neuropsychiatric lupus. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(8):1923-1932.

8. Kampylafka EI, Alexopoulos H, Kosmidis ML, et al. Incidence and prevalence of major central nervous system involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: a 3-year prospective study of 370 patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55843. d

9. Appenzeller S, Cendes F, Costallat LT. Acute psychosisin systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2008;28(3):237-243.

10. Sanna G, Bertolaccini ML, Khamashta MA. Neuropsychiatric involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: current therapeutic approach. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(13):1261-1269.

11. Warrington TP, Bostwick JM. Psychiatric adverse effects of corticosteroids. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(10):1361-1367.

Weakness and facial droop: Is it a stroke?

CASE Sudden weakness

Ms. G, age 59, presents to a local critical access (rural) hospital after an episode of sudden-onset left-sided weakness followed by unconsciousness. She regained consciousness quickly and is awake when she arrives at the hospital. This event was not witnessed, although family members were nearby to call emergency personnel.

a) CT scan

b) MRI

c) EEG

d) head and neck magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA)

EXAMINATION Unremarkable

In the emergency department, Ms. G demonstrates left facial droop, left-sided weakness of her arm and leg, and aphasia. She says she has a severe headache that began after she regained consciousness. She is unable to see out of her left eye.

Ms. G’s NIH Stroke Scale score is 13, indicating a moderate stroke; an emergent head CT does not demonstrate any acute hemorrhagic process. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is administered for a suspected stroke approximately 2 hours after her symptoms began. She is transferred to a larger, tertiary care hospital for further workup and observation.

Upon admission to the ICU, Ms. G’s laboratory values are: sodium, 137 mEq/L; potassium, 5.1 mEq/L; creatinine, 1.26 mg/dL; lipase, 126 U/L; and lactic acid, 9 mg/dL. The glucose level is within normal limits and her urinalysis is unremarkable.

Vital signs are stable and Ms. G is not in acute distress. A physical exam demonstrates 4/5 strength in the left-upper and -lower extremities. Additionally, there are 2+ deep tendon reflexes bilaterally in the biceps, triceps, and brachioradialis. She has left-sided facial droop while in the ICU, and continues to demonstrate some aphasia—although she is alert and oriented to person, time, and place.

The medical history is significant for depression, restless leg syndrome, tonic-clonic seizures, and previous stroke-like events. Medications include amitriptyline, 25 mg/d; citalopram, 20 mg/d; valproate, 1,200 mg/d; and ropinirole, 0.5 mg/d. Her mother has a history of stroke-like events, but her family history and social history are otherwise unremarkable.

The authors' observations

Conversion disorder requires the exclusion of medical causes that could explain the patient’s neurologic symptoms. It is prudent to rule out the most serious of the potential contributors to Ms. G’s condition—namely, an acute cerebrovascular accident. A CT scan did not find any significant pathology, however. In the ICU, an MRI showed no evidence of acute infarction based on diffusion-weighted imaging. A head and neck MRA demonstrated no hemodynamically significant stenosis of the internal carotid arteries. An EEG revealed generalized, polymorphic slow activity without evidence of seizures or epilepsy. An electrocardiogram showed normal ventricular size with an appropriate ejection fraction.

The ICU staff consulted psychiatry to evaluate a psychiatric cause of Ms. G’s symptoms.

An exhaustive and comprehensive workup was performed; there were no significant findings. Although laboratory tests were performed, it was the physical exam that suggested the diagnosis of conversion disorder. In that sense, the diagnostic tests were more of a supportive adjunct to the findings of the physical examination, which consistently failed to indicate a neurologic insult.

Hoover’s sign is a well-established test of functional weakness, in which the patient extends his (her) hip when the contralateral hip is flexed. However, there are other tests of functional weakness that can be useful when considering a conversion disorder diagnosis, including co-contraction, the so-called arm-drop sign, and the sternocleidomastoid test. Diukova and colleagues reported that 80% of patients with functional weakness demonstrated ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid weakness, compared with 11% with vascular hemiparesis.1

a) stroke

b) transient ischemic attack

c) conversion disorder

d) seizure disorder

Ms. G appeared to have suffered an acute ischemic event that caused her neurologic symptoms; her rather extensive psychiatric history was overlooked before the psychiatric service was consulted. When Ms. G was admitted to the ICU, the working differential was postictal seizure state rather than cerebrovascular accident. Ms. G had a poorly defined seizure history, and her history of stroke-like events was murky, at best. She had not been treated previously with tPA, and in all past instances her symptoms resolved spontaneously.

Ms. G’s case illustrates why conversion disorder is difficult to diagnose and why, perhaps, it is even a dangerous diagnostic consideration. Booij and colleagues described two patients with neurologic sequelae thought to be the result of conversion disorder; subsequent imaging demonstrated a posterior stroke.2 Over a 6-year period in an emergency department, Glick and coworkers identified six patients with neurologic pathology who were misdiagnosed with conversion disorder.3 In a study of 4,220 patients presenting to a psychiatric emergency service, three patients complained of extremity paralysis or pain, which was attributed to conversion disorder but later attributed to an organic disease.4

These studies emphasize the precarious nature of diagnosing conversion disorder. For that reason, an extensive medical workup is necessary prior to considering a diagnosis of conversion disorder. In Ms. G’s case, a reasonably thorough workup failed to reveal any obvious pathology. Only then was conversion disorder included as a diagnostic possibility.

EVALUATION Childhood abuse

When performing a mental status exam, Ms. G has poor eye contact, but is cooperative with our interview. She is disheveled and overweight, and denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. She displays constricted affect.

During the interview, we note a left facial droop, although Ms. G is able to smile fully. As the interview progresses, her facial droop seems to become more apparent as we discuss her past, including a history of childhood physical and sexual abuse. She has a history of depression and has been seeing an outpatient psychiatrist for the past year. Ms. G describes being hospitalized in a psychiatric unit, but she is unable to provide any details about when and where this occurred.

Ms. G admits to occasional auditory and visual hallucinations, mostly relating to the abuse she experienced as a child by her parents. She exhibits no other signs or symptoms of psychosis; the hallucinations she describes are consistent with flashbacks and vivid memories relating to the abuse. Ms. G also recently lost her job and is experiencing numerous financial stressors.

The authors' observations

There are many examples in the literature of patients with conversion disorder (Table 1),4 ranging from pseudoseizures, which are relatively common, to intriguing cases, such as cochlear implant failure.5

Some studies estimate that the prevalence of conversion disorder symptoms ranges from 16.1% to 21.9% in the general population.6 Somatoform disorders, including conversion disorder, often are comorbid with anxiety and depression. In one study, 26% of somatoform disorder patients also had depression or anxiety, or both.7 Patients with conversion disorder often report a history of childhood physical or sexual abuse.6 In many patients with conversion disorder, there also appears to be a significant association between the disorder and a recent and distant history of psychosocial stressors.8

Ms. G had an extensive history of abuse by her parents. Conversion disorder presenting as a stroke with realistic and convincing physical manifestations is an unusual presentation. There are case reports that detail this presentation, particularly in the emergency department setting.6

Clinical considerations

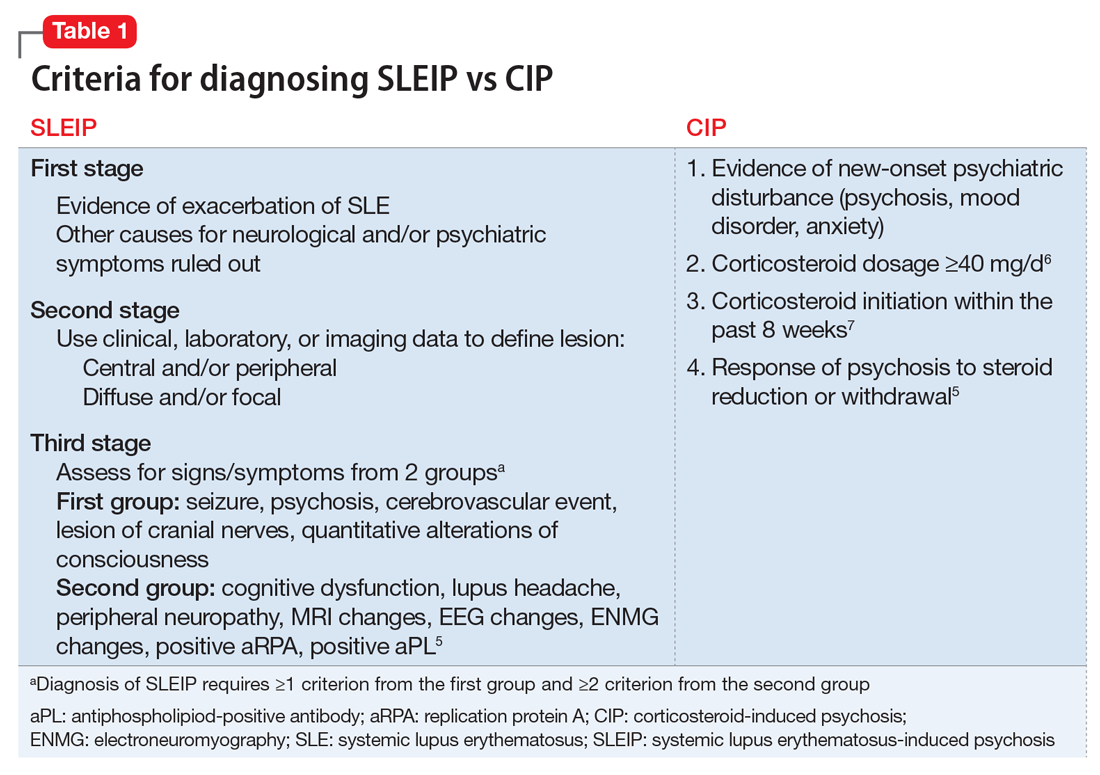

The relative uncertainty that accompanies a diagnosis of conversion disorder can be discomforting for clinicians. As demonstrated by Ms. G, as well as other case reports of conversion disorder, it takes time for the patient to find a clinician who will consider a diagnosis of conversion disorder.9 Largely, this is because DSM-5 requires that other medical causes be ruled out (Table 2).10 This often proves to be problematic because feigning, or the lack thereof, is difficult to prove.9

Further complicating the diagnosis is the lack of a diagnostic test. Neurologists can use video EEG or physical exam maneuvers such as the Hoover’s sign to help make a diagnosis of conversion disorder.11 In this sense, the physical exam maneuvers form the basis of making a diagnosis, while imaging and lab work support the diagnosis. Hoover’s sign, for example, has not been well studied in a controlled manner, but is recognized as a test that may aid a conversion disorder diagnosis. Clinicians should not solely rely upon these physical exam maneuvers; interpreting them in the context of the patient’s overall presentation is critical. This demonstrates the importance of using the physical exam as a way to guide the diagnosis in association with other tests.12

Despite the lack of pathology, studies demonstrate that patients with conversion disorder may have abnormal brain activity that causes them to perceive motor symptoms as involuntary.11 Therefore, there is a clear need for an increased understanding of psychiatric and neurologic components of diagnosing conversion disorder.8

With Ms. G, it was prudent to make a conversion disorder diagnosis to prevent harm to the patient should future stroke-like events occur. Without considering a conversion disorder diagnosis, a patient may continue to receive unnecessary interventions. Basic physical exam maneuvers, such as Hoover’s sign, can be performed quickly in the ED setting before proceeding with other potentially harmful interventions, such as administering tPA.

Treatment. There are few therapies for conversion disorder. This is, in part, because of lack of understanding about the disorder’s neurologic and biologic etiologies. Although there are some studies that support the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), there is little evidence advocating the use of a single mechanism to treat conversion disorder.13 There is evidence that CBT is an effective treatment for several somatoform disorders, including conversion disorder. Research suggests that patients with somatoform disorder have better outcomes when CBT is added to a traditional follow-up.14,15

In Ms. G’s case, we provided information about the diagnosis and scheduled visits to continue her outpatient therapy.

Bottom Line

Conversion disorder is difficult to diagnose, and can mimic potentially life- threatening medical conditions. Conduct a thorough medical workup of these patients, even when it is tempting to jump to a diagnosis of conversion disorder. The use of physical exam maneuvers such as Hoover’s sign may help guide the diagnosis when used in conjunction with other testing.

Related Resources

- Conversion disorder. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/ article/000954.htm.

- Couprie W, Wijdicks EF, Rooijmans HG, et al. Outcome in conver- sion disorder: a follow up study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58(6):750-752.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Citalopram • Celexa

Ropinirole • Requip Valproate • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Diukova GM, Stolajrova AV, Vein AM. Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle test in patients with hysterical and organic paresis. J Neurol Sci. 2001;187(suppl 1):S108.

2. Booij HA, Hamburger HL, Jöbsis GJ, et al. Stroke mimicking conversion disorder: two young women who put our feet back on the ground. Pract Neurol. 2012;12(3):179-181.

3. Glick TH, Workman TP, Gaufberg SV. Suspected conversion disorder: foreseeable risks and avoidable errors. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(11):1272-1277.

4. Fishbain DA, Goldberg M. The misdiagnosis of conversion disorder in a psychiatric emergency service. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1991;13(3):177-181.

5. Carlson ML, Archibald DJ, Gifford RH, et al. Conversion disorder: a missed diagnosis leading to cochlear reimplantation. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32(1):36-38.

6. Sar V, Akyüz G, Kundakçi T, et al. Childhood trauma, dissociation, and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2271-2276.

7. de Waal MW, Arnold IA, Eekhof JA, et al. Somatoform disorders in general practice: prevalence, functional impairment and comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:470-476.

8. Nicholson TR, Stone J, Kanaan RA. Conversion disorder: a problematic diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1267-1273.

9. Stone J, LaFrance WC, Jr, Levenson JL, et al. Issues for

DSM-5: conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6): 626-627.

10. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

11. Voon V, Gallea C, Hattori N, et al. The involuntary nature of conversion disorder. Neurology. 2010;74(3):223-228.

12. Stone J, Zeman A, Sharpe M. Functional weakness and sensory disturbance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002; 73:241-245.

13. Aybek S, Kanaan RA, David AS. The neuropsychiatry of conversion disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(3):275-280.

14. Kroenke K. Efficacy of treatment for somatoform disorders: a review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(9):881-888.

15. Sharpe M, Walker J, Williams C, et al. Guided self-help for functional (psychogenic) symptoms: a randomized controlled efficacy trial. Neurology. 2011;77(6):564-572.

CASE Sudden weakness

Ms. G, age 59, presents to a local critical access (rural) hospital after an episode of sudden-onset left-sided weakness followed by unconsciousness. She regained consciousness quickly and is awake when she arrives at the hospital. This event was not witnessed, although family members were nearby to call emergency personnel.

a) CT scan

b) MRI

c) EEG

d) head and neck magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA)

EXAMINATION Unremarkable

In the emergency department, Ms. G demonstrates left facial droop, left-sided weakness of her arm and leg, and aphasia. She says she has a severe headache that began after she regained consciousness. She is unable to see out of her left eye.

Ms. G’s NIH Stroke Scale score is 13, indicating a moderate stroke; an emergent head CT does not demonstrate any acute hemorrhagic process. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is administered for a suspected stroke approximately 2 hours after her symptoms began. She is transferred to a larger, tertiary care hospital for further workup and observation.

Upon admission to the ICU, Ms. G’s laboratory values are: sodium, 137 mEq/L; potassium, 5.1 mEq/L; creatinine, 1.26 mg/dL; lipase, 126 U/L; and lactic acid, 9 mg/dL. The glucose level is within normal limits and her urinalysis is unremarkable.

Vital signs are stable and Ms. G is not in acute distress. A physical exam demonstrates 4/5 strength in the left-upper and -lower extremities. Additionally, there are 2+ deep tendon reflexes bilaterally in the biceps, triceps, and brachioradialis. She has left-sided facial droop while in the ICU, and continues to demonstrate some aphasia—although she is alert and oriented to person, time, and place.

The medical history is significant for depression, restless leg syndrome, tonic-clonic seizures, and previous stroke-like events. Medications include amitriptyline, 25 mg/d; citalopram, 20 mg/d; valproate, 1,200 mg/d; and ropinirole, 0.5 mg/d. Her mother has a history of stroke-like events, but her family history and social history are otherwise unremarkable.

The authors' observations

Conversion disorder requires the exclusion of medical causes that could explain the patient’s neurologic symptoms. It is prudent to rule out the most serious of the potential contributors to Ms. G’s condition—namely, an acute cerebrovascular accident. A CT scan did not find any significant pathology, however. In the ICU, an MRI showed no evidence of acute infarction based on diffusion-weighted imaging. A head and neck MRA demonstrated no hemodynamically significant stenosis of the internal carotid arteries. An EEG revealed generalized, polymorphic slow activity without evidence of seizures or epilepsy. An electrocardiogram showed normal ventricular size with an appropriate ejection fraction.

The ICU staff consulted psychiatry to evaluate a psychiatric cause of Ms. G’s symptoms.

An exhaustive and comprehensive workup was performed; there were no significant findings. Although laboratory tests were performed, it was the physical exam that suggested the diagnosis of conversion disorder. In that sense, the diagnostic tests were more of a supportive adjunct to the findings of the physical examination, which consistently failed to indicate a neurologic insult.

Hoover’s sign is a well-established test of functional weakness, in which the patient extends his (her) hip when the contralateral hip is flexed. However, there are other tests of functional weakness that can be useful when considering a conversion disorder diagnosis, including co-contraction, the so-called arm-drop sign, and the sternocleidomastoid test. Diukova and colleagues reported that 80% of patients with functional weakness demonstrated ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid weakness, compared with 11% with vascular hemiparesis.1

a) stroke

b) transient ischemic attack

c) conversion disorder

d) seizure disorder

Ms. G appeared to have suffered an acute ischemic event that caused her neurologic symptoms; her rather extensive psychiatric history was overlooked before the psychiatric service was consulted. When Ms. G was admitted to the ICU, the working differential was postictal seizure state rather than cerebrovascular accident. Ms. G had a poorly defined seizure history, and her history of stroke-like events was murky, at best. She had not been treated previously with tPA, and in all past instances her symptoms resolved spontaneously.

Ms. G’s case illustrates why conversion disorder is difficult to diagnose and why, perhaps, it is even a dangerous diagnostic consideration. Booij and colleagues described two patients with neurologic sequelae thought to be the result of conversion disorder; subsequent imaging demonstrated a posterior stroke.2 Over a 6-year period in an emergency department, Glick and coworkers identified six patients with neurologic pathology who were misdiagnosed with conversion disorder.3 In a study of 4,220 patients presenting to a psychiatric emergency service, three patients complained of extremity paralysis or pain, which was attributed to conversion disorder but later attributed to an organic disease.4

These studies emphasize the precarious nature of diagnosing conversion disorder. For that reason, an extensive medical workup is necessary prior to considering a diagnosis of conversion disorder. In Ms. G’s case, a reasonably thorough workup failed to reveal any obvious pathology. Only then was conversion disorder included as a diagnostic possibility.

EVALUATION Childhood abuse

When performing a mental status exam, Ms. G has poor eye contact, but is cooperative with our interview. She is disheveled and overweight, and denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. She displays constricted affect.

During the interview, we note a left facial droop, although Ms. G is able to smile fully. As the interview progresses, her facial droop seems to become more apparent as we discuss her past, including a history of childhood physical and sexual abuse. She has a history of depression and has been seeing an outpatient psychiatrist for the past year. Ms. G describes being hospitalized in a psychiatric unit, but she is unable to provide any details about when and where this occurred.

Ms. G admits to occasional auditory and visual hallucinations, mostly relating to the abuse she experienced as a child by her parents. She exhibits no other signs or symptoms of psychosis; the hallucinations she describes are consistent with flashbacks and vivid memories relating to the abuse. Ms. G also recently lost her job and is experiencing numerous financial stressors.

The authors' observations

There are many examples in the literature of patients with conversion disorder (Table 1),4 ranging from pseudoseizures, which are relatively common, to intriguing cases, such as cochlear implant failure.5

Some studies estimate that the prevalence of conversion disorder symptoms ranges from 16.1% to 21.9% in the general population.6 Somatoform disorders, including conversion disorder, often are comorbid with anxiety and depression. In one study, 26% of somatoform disorder patients also had depression or anxiety, or both.7 Patients with conversion disorder often report a history of childhood physical or sexual abuse.6 In many patients with conversion disorder, there also appears to be a significant association between the disorder and a recent and distant history of psychosocial stressors.8

Ms. G had an extensive history of abuse by her parents. Conversion disorder presenting as a stroke with realistic and convincing physical manifestations is an unusual presentation. There are case reports that detail this presentation, particularly in the emergency department setting.6

Clinical considerations

The relative uncertainty that accompanies a diagnosis of conversion disorder can be discomforting for clinicians. As demonstrated by Ms. G, as well as other case reports of conversion disorder, it takes time for the patient to find a clinician who will consider a diagnosis of conversion disorder.9 Largely, this is because DSM-5 requires that other medical causes be ruled out (Table 2).10 This often proves to be problematic because feigning, or the lack thereof, is difficult to prove.9

Further complicating the diagnosis is the lack of a diagnostic test. Neurologists can use video EEG or physical exam maneuvers such as the Hoover’s sign to help make a diagnosis of conversion disorder.11 In this sense, the physical exam maneuvers form the basis of making a diagnosis, while imaging and lab work support the diagnosis. Hoover’s sign, for example, has not been well studied in a controlled manner, but is recognized as a test that may aid a conversion disorder diagnosis. Clinicians should not solely rely upon these physical exam maneuvers; interpreting them in the context of the patient’s overall presentation is critical. This demonstrates the importance of using the physical exam as a way to guide the diagnosis in association with other tests.12

Despite the lack of pathology, studies demonstrate that patients with conversion disorder may have abnormal brain activity that causes them to perceive motor symptoms as involuntary.11 Therefore, there is a clear need for an increased understanding of psychiatric and neurologic components of diagnosing conversion disorder.8

With Ms. G, it was prudent to make a conversion disorder diagnosis to prevent harm to the patient should future stroke-like events occur. Without considering a conversion disorder diagnosis, a patient may continue to receive unnecessary interventions. Basic physical exam maneuvers, such as Hoover’s sign, can be performed quickly in the ED setting before proceeding with other potentially harmful interventions, such as administering tPA.

Treatment. There are few therapies for conversion disorder. This is, in part, because of lack of understanding about the disorder’s neurologic and biologic etiologies. Although there are some studies that support the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), there is little evidence advocating the use of a single mechanism to treat conversion disorder.13 There is evidence that CBT is an effective treatment for several somatoform disorders, including conversion disorder. Research suggests that patients with somatoform disorder have better outcomes when CBT is added to a traditional follow-up.14,15

In Ms. G’s case, we provided information about the diagnosis and scheduled visits to continue her outpatient therapy.

Bottom Line

Conversion disorder is difficult to diagnose, and can mimic potentially life- threatening medical conditions. Conduct a thorough medical workup of these patients, even when it is tempting to jump to a diagnosis of conversion disorder. The use of physical exam maneuvers such as Hoover’s sign may help guide the diagnosis when used in conjunction with other testing.

Related Resources

- Conversion disorder. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/ article/000954.htm.

- Couprie W, Wijdicks EF, Rooijmans HG, et al. Outcome in conver- sion disorder: a follow up study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58(6):750-752.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Citalopram • Celexa

Ropinirole • Requip Valproate • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Sudden weakness

Ms. G, age 59, presents to a local critical access (rural) hospital after an episode of sudden-onset left-sided weakness followed by unconsciousness. She regained consciousness quickly and is awake when she arrives at the hospital. This event was not witnessed, although family members were nearby to call emergency personnel.

a) CT scan

b) MRI

c) EEG

d) head and neck magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA)

EXAMINATION Unremarkable

In the emergency department, Ms. G demonstrates left facial droop, left-sided weakness of her arm and leg, and aphasia. She says she has a severe headache that began after she regained consciousness. She is unable to see out of her left eye.

Ms. G’s NIH Stroke Scale score is 13, indicating a moderate stroke; an emergent head CT does not demonstrate any acute hemorrhagic process. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is administered for a suspected stroke approximately 2 hours after her symptoms began. She is transferred to a larger, tertiary care hospital for further workup and observation.

Upon admission to the ICU, Ms. G’s laboratory values are: sodium, 137 mEq/L; potassium, 5.1 mEq/L; creatinine, 1.26 mg/dL; lipase, 126 U/L; and lactic acid, 9 mg/dL. The glucose level is within normal limits and her urinalysis is unremarkable.

Vital signs are stable and Ms. G is not in acute distress. A physical exam demonstrates 4/5 strength in the left-upper and -lower extremities. Additionally, there are 2+ deep tendon reflexes bilaterally in the biceps, triceps, and brachioradialis. She has left-sided facial droop while in the ICU, and continues to demonstrate some aphasia—although she is alert and oriented to person, time, and place.

The medical history is significant for depression, restless leg syndrome, tonic-clonic seizures, and previous stroke-like events. Medications include amitriptyline, 25 mg/d; citalopram, 20 mg/d; valproate, 1,200 mg/d; and ropinirole, 0.5 mg/d. Her mother has a history of stroke-like events, but her family history and social history are otherwise unremarkable.

The authors' observations

Conversion disorder requires the exclusion of medical causes that could explain the patient’s neurologic symptoms. It is prudent to rule out the most serious of the potential contributors to Ms. G’s condition—namely, an acute cerebrovascular accident. A CT scan did not find any significant pathology, however. In the ICU, an MRI showed no evidence of acute infarction based on diffusion-weighted imaging. A head and neck MRA demonstrated no hemodynamically significant stenosis of the internal carotid arteries. An EEG revealed generalized, polymorphic slow activity without evidence of seizures or epilepsy. An electrocardiogram showed normal ventricular size with an appropriate ejection fraction.

The ICU staff consulted psychiatry to evaluate a psychiatric cause of Ms. G’s symptoms.

An exhaustive and comprehensive workup was performed; there were no significant findings. Although laboratory tests were performed, it was the physical exam that suggested the diagnosis of conversion disorder. In that sense, the diagnostic tests were more of a supportive adjunct to the findings of the physical examination, which consistently failed to indicate a neurologic insult.

Hoover’s sign is a well-established test of functional weakness, in which the patient extends his (her) hip when the contralateral hip is flexed. However, there are other tests of functional weakness that can be useful when considering a conversion disorder diagnosis, including co-contraction, the so-called arm-drop sign, and the sternocleidomastoid test. Diukova and colleagues reported that 80% of patients with functional weakness demonstrated ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid weakness, compared with 11% with vascular hemiparesis.1

a) stroke

b) transient ischemic attack

c) conversion disorder

d) seizure disorder

Ms. G appeared to have suffered an acute ischemic event that caused her neurologic symptoms; her rather extensive psychiatric history was overlooked before the psychiatric service was consulted. When Ms. G was admitted to the ICU, the working differential was postictal seizure state rather than cerebrovascular accident. Ms. G had a poorly defined seizure history, and her history of stroke-like events was murky, at best. She had not been treated previously with tPA, and in all past instances her symptoms resolved spontaneously.

Ms. G’s case illustrates why conversion disorder is difficult to diagnose and why, perhaps, it is even a dangerous diagnostic consideration. Booij and colleagues described two patients with neurologic sequelae thought to be the result of conversion disorder; subsequent imaging demonstrated a posterior stroke.2 Over a 6-year period in an emergency department, Glick and coworkers identified six patients with neurologic pathology who were misdiagnosed with conversion disorder.3 In a study of 4,220 patients presenting to a psychiatric emergency service, three patients complained of extremity paralysis or pain, which was attributed to conversion disorder but later attributed to an organic disease.4

These studies emphasize the precarious nature of diagnosing conversion disorder. For that reason, an extensive medical workup is necessary prior to considering a diagnosis of conversion disorder. In Ms. G’s case, a reasonably thorough workup failed to reveal any obvious pathology. Only then was conversion disorder included as a diagnostic possibility.

EVALUATION Childhood abuse

When performing a mental status exam, Ms. G has poor eye contact, but is cooperative with our interview. She is disheveled and overweight, and denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. She displays constricted affect.

During the interview, we note a left facial droop, although Ms. G is able to smile fully. As the interview progresses, her facial droop seems to become more apparent as we discuss her past, including a history of childhood physical and sexual abuse. She has a history of depression and has been seeing an outpatient psychiatrist for the past year. Ms. G describes being hospitalized in a psychiatric unit, but she is unable to provide any details about when and where this occurred.

Ms. G admits to occasional auditory and visual hallucinations, mostly relating to the abuse she experienced as a child by her parents. She exhibits no other signs or symptoms of psychosis; the hallucinations she describes are consistent with flashbacks and vivid memories relating to the abuse. Ms. G also recently lost her job and is experiencing numerous financial stressors.

The authors' observations

There are many examples in the literature of patients with conversion disorder (Table 1),4 ranging from pseudoseizures, which are relatively common, to intriguing cases, such as cochlear implant failure.5

Some studies estimate that the prevalence of conversion disorder symptoms ranges from 16.1% to 21.9% in the general population.6 Somatoform disorders, including conversion disorder, often are comorbid with anxiety and depression. In one study, 26% of somatoform disorder patients also had depression or anxiety, or both.7 Patients with conversion disorder often report a history of childhood physical or sexual abuse.6 In many patients with conversion disorder, there also appears to be a significant association between the disorder and a recent and distant history of psychosocial stressors.8

Ms. G had an extensive history of abuse by her parents. Conversion disorder presenting as a stroke with realistic and convincing physical manifestations is an unusual presentation. There are case reports that detail this presentation, particularly in the emergency department setting.6

Clinical considerations

The relative uncertainty that accompanies a diagnosis of conversion disorder can be discomforting for clinicians. As demonstrated by Ms. G, as well as other case reports of conversion disorder, it takes time for the patient to find a clinician who will consider a diagnosis of conversion disorder.9 Largely, this is because DSM-5 requires that other medical causes be ruled out (Table 2).10 This often proves to be problematic because feigning, or the lack thereof, is difficult to prove.9

Further complicating the diagnosis is the lack of a diagnostic test. Neurologists can use video EEG or physical exam maneuvers such as the Hoover’s sign to help make a diagnosis of conversion disorder.11 In this sense, the physical exam maneuvers form the basis of making a diagnosis, while imaging and lab work support the diagnosis. Hoover’s sign, for example, has not been well studied in a controlled manner, but is recognized as a test that may aid a conversion disorder diagnosis. Clinicians should not solely rely upon these physical exam maneuvers; interpreting them in the context of the patient’s overall presentation is critical. This demonstrates the importance of using the physical exam as a way to guide the diagnosis in association with other tests.12

Despite the lack of pathology, studies demonstrate that patients with conversion disorder may have abnormal brain activity that causes them to perceive motor symptoms as involuntary.11 Therefore, there is a clear need for an increased understanding of psychiatric and neurologic components of diagnosing conversion disorder.8

With Ms. G, it was prudent to make a conversion disorder diagnosis to prevent harm to the patient should future stroke-like events occur. Without considering a conversion disorder diagnosis, a patient may continue to receive unnecessary interventions. Basic physical exam maneuvers, such as Hoover’s sign, can be performed quickly in the ED setting before proceeding with other potentially harmful interventions, such as administering tPA.

Treatment. There are few therapies for conversion disorder. This is, in part, because of lack of understanding about the disorder’s neurologic and biologic etiologies. Although there are some studies that support the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), there is little evidence advocating the use of a single mechanism to treat conversion disorder.13 There is evidence that CBT is an effective treatment for several somatoform disorders, including conversion disorder. Research suggests that patients with somatoform disorder have better outcomes when CBT is added to a traditional follow-up.14,15

In Ms. G’s case, we provided information about the diagnosis and scheduled visits to continue her outpatient therapy.

Bottom Line

Conversion disorder is difficult to diagnose, and can mimic potentially life- threatening medical conditions. Conduct a thorough medical workup of these patients, even when it is tempting to jump to a diagnosis of conversion disorder. The use of physical exam maneuvers such as Hoover’s sign may help guide the diagnosis when used in conjunction with other testing.

Related Resources

- Conversion disorder. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/ article/000954.htm.

- Couprie W, Wijdicks EF, Rooijmans HG, et al. Outcome in conver- sion disorder: a follow up study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58(6):750-752.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Citalopram • Celexa

Ropinirole • Requip Valproate • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Diukova GM, Stolajrova AV, Vein AM. Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle test in patients with hysterical and organic paresis. J Neurol Sci. 2001;187(suppl 1):S108.

2. Booij HA, Hamburger HL, Jöbsis GJ, et al. Stroke mimicking conversion disorder: two young women who put our feet back on the ground. Pract Neurol. 2012;12(3):179-181.

3. Glick TH, Workman TP, Gaufberg SV. Suspected conversion disorder: foreseeable risks and avoidable errors. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(11):1272-1277.

4. Fishbain DA, Goldberg M. The misdiagnosis of conversion disorder in a psychiatric emergency service. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1991;13(3):177-181.

5. Carlson ML, Archibald DJ, Gifford RH, et al. Conversion disorder: a missed diagnosis leading to cochlear reimplantation. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32(1):36-38.

6. Sar V, Akyüz G, Kundakçi T, et al. Childhood trauma, dissociation, and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2271-2276.

7. de Waal MW, Arnold IA, Eekhof JA, et al. Somatoform disorders in general practice: prevalence, functional impairment and comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:470-476.

8. Nicholson TR, Stone J, Kanaan RA. Conversion disorder: a problematic diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1267-1273.

9. Stone J, LaFrance WC, Jr, Levenson JL, et al. Issues for

DSM-5: conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6): 626-627.

10. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

11. Voon V, Gallea C, Hattori N, et al. The involuntary nature of conversion disorder. Neurology. 2010;74(3):223-228.

12. Stone J, Zeman A, Sharpe M. Functional weakness and sensory disturbance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002; 73:241-245.

13. Aybek S, Kanaan RA, David AS. The neuropsychiatry of conversion disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(3):275-280.

14. Kroenke K. Efficacy of treatment for somatoform disorders: a review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(9):881-888.

15. Sharpe M, Walker J, Williams C, et al. Guided self-help for functional (psychogenic) symptoms: a randomized controlled efficacy trial. Neurology. 2011;77(6):564-572.

1. Diukova GM, Stolajrova AV, Vein AM. Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle test in patients with hysterical and organic paresis. J Neurol Sci. 2001;187(suppl 1):S108.

2. Booij HA, Hamburger HL, Jöbsis GJ, et al. Stroke mimicking conversion disorder: two young women who put our feet back on the ground. Pract Neurol. 2012;12(3):179-181.

3. Glick TH, Workman TP, Gaufberg SV. Suspected conversion disorder: foreseeable risks and avoidable errors. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(11):1272-1277.

4. Fishbain DA, Goldberg M. The misdiagnosis of conversion disorder in a psychiatric emergency service. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1991;13(3):177-181.

5. Carlson ML, Archibald DJ, Gifford RH, et al. Conversion disorder: a missed diagnosis leading to cochlear reimplantation. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32(1):36-38.

6. Sar V, Akyüz G, Kundakçi T, et al. Childhood trauma, dissociation, and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2271-2276.

7. de Waal MW, Arnold IA, Eekhof JA, et al. Somatoform disorders in general practice: prevalence, functional impairment and comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:470-476.

8. Nicholson TR, Stone J, Kanaan RA. Conversion disorder: a problematic diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1267-1273.

9. Stone J, LaFrance WC, Jr, Levenson JL, et al. Issues for

DSM-5: conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6): 626-627.

10. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

11. Voon V, Gallea C, Hattori N, et al. The involuntary nature of conversion disorder. Neurology. 2010;74(3):223-228.

12. Stone J, Zeman A, Sharpe M. Functional weakness and sensory disturbance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002; 73:241-245.

13. Aybek S, Kanaan RA, David AS. The neuropsychiatry of conversion disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(3):275-280.

14. Kroenke K. Efficacy of treatment for somatoform disorders: a review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(9):881-888.

15. Sharpe M, Walker J, Williams C, et al. Guided self-help for functional (psychogenic) symptoms: a randomized controlled efficacy trial. Neurology. 2011;77(6):564-572.