User login

Prostate Cancer Foundation-Department of Veterans Affairs Partnership: A Model of Public-Private Collaboration to Advance Treatment and Care of Invasive Cancers(FULL)

In late 2016, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF) announced a multiyear public-private partnership to deliver precision oncology and best-in-class care to all veterans battling prostate cancer.1 The creation of this partnership was due to several favorable factors. At that time, VA Secretary Robert A. McDonald had created the Secretary’s Center for Strategic Partnerships. This Center provided a mechanism for nonprofit and industry partners to collaborate with the VA, thereby advancing partnerships that served the VA mission of “serving and honoring…America’s veterans.”1,2 Concurrently, Vice President Joseph Biden’s Cancer Moonshot (later renamed the Beau Biden Cancer Moonshot) charged PCF and other cancer-focused organizations with the ambitious goal of making a decade’s worth of advancements in cancer prevention, diagnosis, and treatment in 5 years.3 As such, both organizations were positioned to recognize and address the unique prostate cancer challenges faced by male veterans, which ultimately led to the PCF-VA partnership.

A number of factors have allowed the PCF-VA partnership to scale the Centers of Excellence (COE) program. This article seeks to highlight the strategic organizing and mobilization techniques employed by the PCF-VA partnership, which can inform future public-private hybrid initiatives focused on precision medicine.

Executive Leadership as Patient Advocates

From its creation, the PCF-VA partnership placed as much importance on veteran patient care as it has on making oncologic advances. The fact that this focus came primarily from executive leadership was critical to the partnership’s success. PCF board members emphasized the significance of prioritizing veterans and military families in cancer research efforts.

A notable example is S. Ward “Trip” Casscells, MD, a veteran who was deployed to Iraq in 2006 and subsequently served as US Department of Defense Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. He focused much of his leadership on ensuring that veterans and military families, having performed a critical service for the country, were served with this same degree of excellence when it came to health.4 Fellow PCF Board member Lawrence Stupski, spoke publicly about his drug-resistant form of prostate cancer, bringing awareness to the complexity of ending death and suffering from the disease.5 Like Casscells, Stupski has a military service background, and served in Vietnam in 1968 as an officer in the US Navy. Both participated in multiple prostate cancer clinical trials themselves, serving as models of veteran trial participants. This visibility and leadership created a culture where veterans were not just instrumental in advancing cancer research, but also representative of a responsibility to ensure high-quality care for an underserved and at-risk community (Figure 1).

Executive advocacy and visionary philanthropy on behalf of veterans were vital to catalyzing the PCF-VA partnership framework, allowing both organizations to act on shared goals through a joint venture. Stupski’s legacy also jump-started the partnership itself, as the Stupski Foundation provided the crucial initial funding to launch a pilot version of the partnership.

Ultimately, this suggests that entrepreneurial philanthropy, top-level patient-led advocacy, and executive leadership can bolster the success of future health partnerships by advocating for specific missions, thus allowing convergence of goals between public and private entities. Visibility of leaders also encourages participation in the initiative itself, specifically in regard to patients being willing to enroll in clinical trials.

During the Launch Pad: Pathways to Cancer InnoVAtion PCF-VA summit in November 2016, PCF and the VA signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) that solidified joint goals and accountability practices to create a scalable model for veteran-centered, genomics-based precision oncology care. Special focus was placed upon developing clinical trials for vulnerable veteran populations (Figure 2). PCF dedicated $50 million of funding to this partnership, facilitated largely in part by several philanthropists who stepped up after the MOU was signed, and early, life-extending successes from the pilot were demonstrated. This “snowballing” of funding indicates that the establishment of a public-private health partnership—with clear and compelling goals and early proof-of-concept—galvanizes efforts to further advance the partnership by garnering critical philanthropic investment.

VHA Economy of Scale

Utilizing the vast capacity of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) for care was integral to the success of the partnership. The VHA serves 9 million veterans each year in 1,255 health care facilities, which include 170 medical centers and 1,075 outpatient clinics.6 As the nation’s largest integrated health care system, the VHA approaches cancer care with a single electronic health record system across all of its facilities, featuring comprehensive clinical outcome documentation.7 The VHA’s systemwide DNA sequence platform, through the National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP), also provided an optimal area for research and standardization of precision oncology practices on a national scale.8

Centers of Excellence: An Adaptable Model

The primary thrust of the partnership centers on the PCF-VA COEs, which form the Precision Oncology Program for Cancer of the Prostate (POPCaP) network. Over the last 4 years, PCF-deployed philanthropy has established 12 PCF-VA COEs, located in the Bronx and Manhattan, New York; Tampa Bay, Florida; Los Angeles, California; Seattle, Washington; Chicago, Illinois; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Ann Arbor, Michigan; Durham, North Carolina; Washington, DC; Boston, Massachusetts; and Portland, Oregon. Sites were initially chosen based on strong connections to academic medical centers, National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive care centers, and physician-scientists who were professionally invested in precision prostate cancer oncology. Drawing on PCF’s existing networks helped to identify these areas, which were already rich in human and technological capital, before expanding to areas that were less resource rich. Future health partnerships may therefore consider capitalizing on existing relationships to spark initial growth, which can provide pathways for scaling.

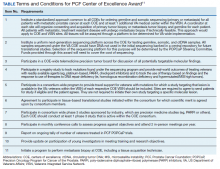

In collaboration with NPOP, COEs work to sequence genomic and somatic tissue from veterans with metastatic prostate cancer, connect patients to appropriate clinical trials and treatment pathways, and advance guidelines for precision cancer care. Certain aspects of COE operations remain constant across all facilities. Annual progress reports, comprising of a written report, slide deck of accomplishments, and bulleted delineation of challenges and future plans are required of all COE-funded investigators. All COEs also are tasked with hiring a center coordinator, instituting a standardized sequencing and mutation reporting protocol, participating in consortium-wide phase 3 studies, and engaging in monthly conference calls to assess progress. A complete list of requirements is found in the Table.

However, the methods through which these goals must be completed is at the discretion of the COE investigators. Each COE, due to institutional and patient variance, experiences distinctive challenges and must mold its practice to fit existing capacities. For example, certain sites optimized workflow by training coordinators to analyze specimens, thereby improving care speed for veteran patients. Other COEs maximized nearby resources by hiring offsite specialists such as genetic counselors and interventional radiologists. By providing the freedom to design site-specific methodology, the PCF-VA partnership allows each COE to meet the award goals through any appropriate path using the funds provided, increasing efficiency and optimizing progress. This diversity of protocol also helped to expand the capabilities of the POPCaP Network, allowing sites to specialize in areas of interest in precision oncology. This eventually helped to inform future initiatives.

Accelerating Clinical Trials

A critical feature of the POPCaP network is the Prostate Cancer Analysis for Therapy Choice (PATCH) plexus.9 Through this investigative umbrella, veterans who are sequenced at any COE are given access to clinical trials at sites across POPCaP. Funding is available to support veteran travel to these sites, decreasing the chance that a veteran’s location is a barrier to treatment. In this way, the PCF-VA partnership continues to broaden treatment scopes for tens of thousands of veterans while simultaneously advancing clinical knowledge of precision oncology.

Fostering a Scientific Community

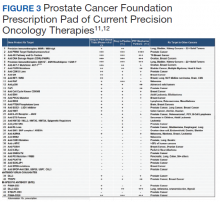

The PCF-VA partnership’s COE initiative capitalizes on resources from both nonprofit and public sectors to cultivate dynamic scientific discourse and investigative support. Through monthly meetings of the NPOP Molecular Oncology Tumor Board, COE investigators receive guidance and education to better assist veterans sequenced through their programs. Another example of enriched scientific collaboration are the Dream Team investigators, who were collaboratively funded by PCF, Stand Up 2 Cancer, and the American Association for Cancer Research.10 These teams made significant strides in genomic profiling of advanced prostate cancer and outpatient computed tomography-guided metastatic bone biopsy techniques. Through the PCF-VA partnership, COE researchers benefited from these investigators’ insight and expertise during regular check-in calls with investigators. PCF’s Prescription Pad, also connects all investigators to current therapies and trials, better informing them of future directions for their own work (Figure 3).11,12

The PCF-VA partnership also facilitates peer-to-peer communication through regular inperson and virtual meetings of investigators, coordinators, and other stakeholders. These meetings allow the creation of focused working groups composed of COE leaders across the nation. The working groups seek to improve all aspects of functionality, including operational roadblocks, sequencing and phenotyping protocols, and addressing health service disparities. The VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, Washington, and the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center in California both are mentorship sites that play instrumental roles in guiding newer sites through challenges, such as obtaining rapid pathology results and navigating the VA system. This interinvestigator communication also helps to recruit new junior and senior investigators to POPCaP, thereby broadening the network’s reach.

Future Pathways

In line with the mission outlined in the MOU of developing treatments for veteran populations, the PCF-VA partnership has actively pursued addressing veteran health inequities. In 2018, a $2.5 million gift from Robert F. Smith, Founder, Chairman, and Chief Executive Officer of Vista Equity Partners, set up the Chicago COE with the express purpose of serving African American veterans, who represent men at highest risk of prostate cancer incidence and mortality.13 A regularly convened health disparities working group explores future efforts. This group, composed of VA investigators, epidemiologists, geneticists, and other field leaders, seeks to advance the most compelling approaches to eliminate inequities in prostate cancer care.

A novel nursing initiative that focuses on the role of nurses in providing genetic services for prostate cancer is being developed. The need for new genetic care models and significant barriers to genetic service delivery have been well-documented for prostate cancer.14 The initiative provides nurses with opportunities to train with POPCaP and VA geneticists, enroll in a City of Hope genetics course, and to join a collaborative of geneticists, medical oncologists, and nurse practitioners.15 By furthering nursing education and leadership, the initiative empowers nurses to fill the gaps in veteran health care, particularly in genomics-based precision oncology.

The COE platform also has provided the foundation for the building of COEs for other cancers relevant to veterans, such as lung cancer. This expansion of COE function helps to further the VA goal of not only creating COEs, but a system of excellence. More recently, COE infrastructure has been leveraged in the fight against COVID-19 through HITCH, a clinical trial investigating the use of temporary androgen suppression in improving clinical outcomes of veterans with COVID-19.16 This expansion of function also provides a mechanism for COEs to continue to be funded in the future: attracting federal capital, private philanthropy, and industrial support is dependent on realized and expanded goals, as well as demonstrable progress in veteran care.

Conclusions

The PCF-VA partnership serves as an example of a public-private health partnership pursuing strategic pathways and bold goals to ensure that every eligible veteran has access to precision oncology. These pathways include advocacy on the part of executive leadership, recognizing existing economies of scale, building compelling narratives to maximize funding, creating flexible requirements, and facilitating a robust, resource-rich scientific network. This partnership already has opened doors to future initiatives and continues to adapt to a rapidly changing health landscape. The discussed strategies have the potential to inform future health initiatives and showcase how a systemic approach to eradicating health inequities can greatly benefit underserved communities.

The success of the PCF-VA partnership represents more than just an efficient partnership model. The partnership’s emphasis on veterans, who exemplify service, highlights the extent to which cancer patients sacrifice to contribute to medical research. This service necessitates a service in kind: all health stakeholders share the responsibility to rapidly advance therapies and care, both to honor the patients who have come before, and to meet the needs of patients with treatment resistant forms of the disease urgently awaiting precision breakthroughs and cures.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Secretary’s Center for Strategic Partnerships (SCSP): about us. https://www.va.gov/scsp/about/. Updated January 22, 2020. Accessed July 27, 2020.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs. About VA. https://www.va.gov/about_va/mission.asp. Updated August 20, 2015. Accessed July 27, 2020.

3. American Association for Cancer Research. National Cancer Moonshot Initiative. https://www.aacr.org/professionals/policy-and-advocacy/science-policy-government-affairs/national-cancer-moonshot-initiative. Accessed July 30, 2020.

4. Zogby J, Fighting cancer is a Defense Department obligation. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/fighting-cancer-is-our-co_b_837535. Updated May 25, 2011. Accessed July 30, 2020.

5. Colliver V. Lawrence Stupski, former Schwab exec, dies. San Francisco Chronicle June 12, 2013. https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Lawrence-Stupski-former-Schwab-exec-dies-4597329.php. Accessed July 30, 2020.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. About VHA. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp. Updated July 14, 2019. Accessed July 27, 2020.

7. Montgomery B, Rettig M, Kasten J, Muralidhar S, Myrie K, Ramoni R. The Precision Oncology Program for Cancer of the Prostate (POPCaP) Network: a Veterans Affairs/Prostate Cancer Foundation collaboration. Fed Pract. 2020;37 (suppl 4):S48-S53. doi:10.12788/fp.0021

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Oncology Program Office: about us. https://www.cancer.va.gov/CANCER/about.asp. Accessed July 28, 2020.

9. Graff JN, Huang GD. Leveraging Veterans Health Administration clinical and research resources to accelerate discovery and testing in precision oncology. Fed Pract. 2020;37(8):S62-S67. doi:10.12788/fp.0028

10. Prostate Cancer Foundation. Prostate Cancer Foundation and Stand Up To Cancer announce new dream team [press release]. https://www.pcf.org/news/prostate-cancer-foundation-and-stand-up-to-cancer-announce-new-dream-team/. Published April 1, 2020. Accessed July 30, 2020.

11. Quigley DA, Dang HX, Zhao SG, et al. Genomic hallmarks and structural variation in metastatic prostate cancer [published correction appears in Cell. 2018 Oct 18;175(3):889]. Cell. 2018;174(3):758-769.e9. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.039

12. Armenia J, Wankowicz SAM, Liu D, et al. The long tail of oncogenic drivers in prostate cancer [published correction appears in Nat Genet. 2019 Jul;51(7):1194]. Nat Genet. 2018;50(5):645-651. doi:10.1038/s41588-018-0078-z

13. Prostate Cancer Foundation. $2.5 million gift from Robert Frederick Smith to the Prostate Cancer Foundation is the largest donation ever dedicated to advancing prostate cancer research in African-American men [press release]. https://www.pcf.org/news/robert-frederick-smith-gift/. Published January 14, 2018. Accessed July 27, 2020.

14. Carlo MI, Giri VN, Paller CJ, et al. Evolving intersection between inherited cancer genetics and therapeutic clinical trials in prostate cancer: a white paper from the Germline Genetics Working Group of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Consortium. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2018:10.1200/PO.18.00060. doi:10.1200/PO.18.00060

15. City of Hope. Intensive course in genomic cancer risk assessment. https://www.cityofhope.org/education/health-professional-education/cancer-genomics-education-program/intensive-course-in-cancer-risk-assessment-overview. Accessed July 28, 2020.

16. US National Library of Medicine, Clinicaltrial.gov. Hormonal Intervention for the Treatment in Veterans with COVID-19 Requiring Hospitalization (HITCH): NCT04397718. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04397718. Updated July 23, 2020. Accessed July 30, 2020.

In late 2016, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF) announced a multiyear public-private partnership to deliver precision oncology and best-in-class care to all veterans battling prostate cancer.1 The creation of this partnership was due to several favorable factors. At that time, VA Secretary Robert A. McDonald had created the Secretary’s Center for Strategic Partnerships. This Center provided a mechanism for nonprofit and industry partners to collaborate with the VA, thereby advancing partnerships that served the VA mission of “serving and honoring…America’s veterans.”1,2 Concurrently, Vice President Joseph Biden’s Cancer Moonshot (later renamed the Beau Biden Cancer Moonshot) charged PCF and other cancer-focused organizations with the ambitious goal of making a decade’s worth of advancements in cancer prevention, diagnosis, and treatment in 5 years.3 As such, both organizations were positioned to recognize and address the unique prostate cancer challenges faced by male veterans, which ultimately led to the PCF-VA partnership.

A number of factors have allowed the PCF-VA partnership to scale the Centers of Excellence (COE) program. This article seeks to highlight the strategic organizing and mobilization techniques employed by the PCF-VA partnership, which can inform future public-private hybrid initiatives focused on precision medicine.

Executive Leadership as Patient Advocates

From its creation, the PCF-VA partnership placed as much importance on veteran patient care as it has on making oncologic advances. The fact that this focus came primarily from executive leadership was critical to the partnership’s success. PCF board members emphasized the significance of prioritizing veterans and military families in cancer research efforts.

A notable example is S. Ward “Trip” Casscells, MD, a veteran who was deployed to Iraq in 2006 and subsequently served as US Department of Defense Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. He focused much of his leadership on ensuring that veterans and military families, having performed a critical service for the country, were served with this same degree of excellence when it came to health.4 Fellow PCF Board member Lawrence Stupski, spoke publicly about his drug-resistant form of prostate cancer, bringing awareness to the complexity of ending death and suffering from the disease.5 Like Casscells, Stupski has a military service background, and served in Vietnam in 1968 as an officer in the US Navy. Both participated in multiple prostate cancer clinical trials themselves, serving as models of veteran trial participants. This visibility and leadership created a culture where veterans were not just instrumental in advancing cancer research, but also representative of a responsibility to ensure high-quality care for an underserved and at-risk community (Figure 1).

Executive advocacy and visionary philanthropy on behalf of veterans were vital to catalyzing the PCF-VA partnership framework, allowing both organizations to act on shared goals through a joint venture. Stupski’s legacy also jump-started the partnership itself, as the Stupski Foundation provided the crucial initial funding to launch a pilot version of the partnership.

Ultimately, this suggests that entrepreneurial philanthropy, top-level patient-led advocacy, and executive leadership can bolster the success of future health partnerships by advocating for specific missions, thus allowing convergence of goals between public and private entities. Visibility of leaders also encourages participation in the initiative itself, specifically in regard to patients being willing to enroll in clinical trials.

During the Launch Pad: Pathways to Cancer InnoVAtion PCF-VA summit in November 2016, PCF and the VA signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) that solidified joint goals and accountability practices to create a scalable model for veteran-centered, genomics-based precision oncology care. Special focus was placed upon developing clinical trials for vulnerable veteran populations (Figure 2). PCF dedicated $50 million of funding to this partnership, facilitated largely in part by several philanthropists who stepped up after the MOU was signed, and early, life-extending successes from the pilot were demonstrated. This “snowballing” of funding indicates that the establishment of a public-private health partnership—with clear and compelling goals and early proof-of-concept—galvanizes efforts to further advance the partnership by garnering critical philanthropic investment.

VHA Economy of Scale

Utilizing the vast capacity of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) for care was integral to the success of the partnership. The VHA serves 9 million veterans each year in 1,255 health care facilities, which include 170 medical centers and 1,075 outpatient clinics.6 As the nation’s largest integrated health care system, the VHA approaches cancer care with a single electronic health record system across all of its facilities, featuring comprehensive clinical outcome documentation.7 The VHA’s systemwide DNA sequence platform, through the National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP), also provided an optimal area for research and standardization of precision oncology practices on a national scale.8

Centers of Excellence: An Adaptable Model

The primary thrust of the partnership centers on the PCF-VA COEs, which form the Precision Oncology Program for Cancer of the Prostate (POPCaP) network. Over the last 4 years, PCF-deployed philanthropy has established 12 PCF-VA COEs, located in the Bronx and Manhattan, New York; Tampa Bay, Florida; Los Angeles, California; Seattle, Washington; Chicago, Illinois; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Ann Arbor, Michigan; Durham, North Carolina; Washington, DC; Boston, Massachusetts; and Portland, Oregon. Sites were initially chosen based on strong connections to academic medical centers, National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive care centers, and physician-scientists who were professionally invested in precision prostate cancer oncology. Drawing on PCF’s existing networks helped to identify these areas, which were already rich in human and technological capital, before expanding to areas that were less resource rich. Future health partnerships may therefore consider capitalizing on existing relationships to spark initial growth, which can provide pathways for scaling.

In collaboration with NPOP, COEs work to sequence genomic and somatic tissue from veterans with metastatic prostate cancer, connect patients to appropriate clinical trials and treatment pathways, and advance guidelines for precision cancer care. Certain aspects of COE operations remain constant across all facilities. Annual progress reports, comprising of a written report, slide deck of accomplishments, and bulleted delineation of challenges and future plans are required of all COE-funded investigators. All COEs also are tasked with hiring a center coordinator, instituting a standardized sequencing and mutation reporting protocol, participating in consortium-wide phase 3 studies, and engaging in monthly conference calls to assess progress. A complete list of requirements is found in the Table.

However, the methods through which these goals must be completed is at the discretion of the COE investigators. Each COE, due to institutional and patient variance, experiences distinctive challenges and must mold its practice to fit existing capacities. For example, certain sites optimized workflow by training coordinators to analyze specimens, thereby improving care speed for veteran patients. Other COEs maximized nearby resources by hiring offsite specialists such as genetic counselors and interventional radiologists. By providing the freedom to design site-specific methodology, the PCF-VA partnership allows each COE to meet the award goals through any appropriate path using the funds provided, increasing efficiency and optimizing progress. This diversity of protocol also helped to expand the capabilities of the POPCaP Network, allowing sites to specialize in areas of interest in precision oncology. This eventually helped to inform future initiatives.

Accelerating Clinical Trials

A critical feature of the POPCaP network is the Prostate Cancer Analysis for Therapy Choice (PATCH) plexus.9 Through this investigative umbrella, veterans who are sequenced at any COE are given access to clinical trials at sites across POPCaP. Funding is available to support veteran travel to these sites, decreasing the chance that a veteran’s location is a barrier to treatment. In this way, the PCF-VA partnership continues to broaden treatment scopes for tens of thousands of veterans while simultaneously advancing clinical knowledge of precision oncology.

Fostering a Scientific Community

The PCF-VA partnership’s COE initiative capitalizes on resources from both nonprofit and public sectors to cultivate dynamic scientific discourse and investigative support. Through monthly meetings of the NPOP Molecular Oncology Tumor Board, COE investigators receive guidance and education to better assist veterans sequenced through their programs. Another example of enriched scientific collaboration are the Dream Team investigators, who were collaboratively funded by PCF, Stand Up 2 Cancer, and the American Association for Cancer Research.10 These teams made significant strides in genomic profiling of advanced prostate cancer and outpatient computed tomography-guided metastatic bone biopsy techniques. Through the PCF-VA partnership, COE researchers benefited from these investigators’ insight and expertise during regular check-in calls with investigators. PCF’s Prescription Pad, also connects all investigators to current therapies and trials, better informing them of future directions for their own work (Figure 3).11,12

The PCF-VA partnership also facilitates peer-to-peer communication through regular inperson and virtual meetings of investigators, coordinators, and other stakeholders. These meetings allow the creation of focused working groups composed of COE leaders across the nation. The working groups seek to improve all aspects of functionality, including operational roadblocks, sequencing and phenotyping protocols, and addressing health service disparities. The VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, Washington, and the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center in California both are mentorship sites that play instrumental roles in guiding newer sites through challenges, such as obtaining rapid pathology results and navigating the VA system. This interinvestigator communication also helps to recruit new junior and senior investigators to POPCaP, thereby broadening the network’s reach.

Future Pathways

In line with the mission outlined in the MOU of developing treatments for veteran populations, the PCF-VA partnership has actively pursued addressing veteran health inequities. In 2018, a $2.5 million gift from Robert F. Smith, Founder, Chairman, and Chief Executive Officer of Vista Equity Partners, set up the Chicago COE with the express purpose of serving African American veterans, who represent men at highest risk of prostate cancer incidence and mortality.13 A regularly convened health disparities working group explores future efforts. This group, composed of VA investigators, epidemiologists, geneticists, and other field leaders, seeks to advance the most compelling approaches to eliminate inequities in prostate cancer care.

A novel nursing initiative that focuses on the role of nurses in providing genetic services for prostate cancer is being developed. The need for new genetic care models and significant barriers to genetic service delivery have been well-documented for prostate cancer.14 The initiative provides nurses with opportunities to train with POPCaP and VA geneticists, enroll in a City of Hope genetics course, and to join a collaborative of geneticists, medical oncologists, and nurse practitioners.15 By furthering nursing education and leadership, the initiative empowers nurses to fill the gaps in veteran health care, particularly in genomics-based precision oncology.

The COE platform also has provided the foundation for the building of COEs for other cancers relevant to veterans, such as lung cancer. This expansion of COE function helps to further the VA goal of not only creating COEs, but a system of excellence. More recently, COE infrastructure has been leveraged in the fight against COVID-19 through HITCH, a clinical trial investigating the use of temporary androgen suppression in improving clinical outcomes of veterans with COVID-19.16 This expansion of function also provides a mechanism for COEs to continue to be funded in the future: attracting federal capital, private philanthropy, and industrial support is dependent on realized and expanded goals, as well as demonstrable progress in veteran care.

Conclusions

The PCF-VA partnership serves as an example of a public-private health partnership pursuing strategic pathways and bold goals to ensure that every eligible veteran has access to precision oncology. These pathways include advocacy on the part of executive leadership, recognizing existing economies of scale, building compelling narratives to maximize funding, creating flexible requirements, and facilitating a robust, resource-rich scientific network. This partnership already has opened doors to future initiatives and continues to adapt to a rapidly changing health landscape. The discussed strategies have the potential to inform future health initiatives and showcase how a systemic approach to eradicating health inequities can greatly benefit underserved communities.

The success of the PCF-VA partnership represents more than just an efficient partnership model. The partnership’s emphasis on veterans, who exemplify service, highlights the extent to which cancer patients sacrifice to contribute to medical research. This service necessitates a service in kind: all health stakeholders share the responsibility to rapidly advance therapies and care, both to honor the patients who have come before, and to meet the needs of patients with treatment resistant forms of the disease urgently awaiting precision breakthroughs and cures.

In late 2016, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF) announced a multiyear public-private partnership to deliver precision oncology and best-in-class care to all veterans battling prostate cancer.1 The creation of this partnership was due to several favorable factors. At that time, VA Secretary Robert A. McDonald had created the Secretary’s Center for Strategic Partnerships. This Center provided a mechanism for nonprofit and industry partners to collaborate with the VA, thereby advancing partnerships that served the VA mission of “serving and honoring…America’s veterans.”1,2 Concurrently, Vice President Joseph Biden’s Cancer Moonshot (later renamed the Beau Biden Cancer Moonshot) charged PCF and other cancer-focused organizations with the ambitious goal of making a decade’s worth of advancements in cancer prevention, diagnosis, and treatment in 5 years.3 As such, both organizations were positioned to recognize and address the unique prostate cancer challenges faced by male veterans, which ultimately led to the PCF-VA partnership.

A number of factors have allowed the PCF-VA partnership to scale the Centers of Excellence (COE) program. This article seeks to highlight the strategic organizing and mobilization techniques employed by the PCF-VA partnership, which can inform future public-private hybrid initiatives focused on precision medicine.

Executive Leadership as Patient Advocates

From its creation, the PCF-VA partnership placed as much importance on veteran patient care as it has on making oncologic advances. The fact that this focus came primarily from executive leadership was critical to the partnership’s success. PCF board members emphasized the significance of prioritizing veterans and military families in cancer research efforts.

A notable example is S. Ward “Trip” Casscells, MD, a veteran who was deployed to Iraq in 2006 and subsequently served as US Department of Defense Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. He focused much of his leadership on ensuring that veterans and military families, having performed a critical service for the country, were served with this same degree of excellence when it came to health.4 Fellow PCF Board member Lawrence Stupski, spoke publicly about his drug-resistant form of prostate cancer, bringing awareness to the complexity of ending death and suffering from the disease.5 Like Casscells, Stupski has a military service background, and served in Vietnam in 1968 as an officer in the US Navy. Both participated in multiple prostate cancer clinical trials themselves, serving as models of veteran trial participants. This visibility and leadership created a culture where veterans were not just instrumental in advancing cancer research, but also representative of a responsibility to ensure high-quality care for an underserved and at-risk community (Figure 1).

Executive advocacy and visionary philanthropy on behalf of veterans were vital to catalyzing the PCF-VA partnership framework, allowing both organizations to act on shared goals through a joint venture. Stupski’s legacy also jump-started the partnership itself, as the Stupski Foundation provided the crucial initial funding to launch a pilot version of the partnership.

Ultimately, this suggests that entrepreneurial philanthropy, top-level patient-led advocacy, and executive leadership can bolster the success of future health partnerships by advocating for specific missions, thus allowing convergence of goals between public and private entities. Visibility of leaders also encourages participation in the initiative itself, specifically in regard to patients being willing to enroll in clinical trials.

During the Launch Pad: Pathways to Cancer InnoVAtion PCF-VA summit in November 2016, PCF and the VA signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) that solidified joint goals and accountability practices to create a scalable model for veteran-centered, genomics-based precision oncology care. Special focus was placed upon developing clinical trials for vulnerable veteran populations (Figure 2). PCF dedicated $50 million of funding to this partnership, facilitated largely in part by several philanthropists who stepped up after the MOU was signed, and early, life-extending successes from the pilot were demonstrated. This “snowballing” of funding indicates that the establishment of a public-private health partnership—with clear and compelling goals and early proof-of-concept—galvanizes efforts to further advance the partnership by garnering critical philanthropic investment.

VHA Economy of Scale

Utilizing the vast capacity of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) for care was integral to the success of the partnership. The VHA serves 9 million veterans each year in 1,255 health care facilities, which include 170 medical centers and 1,075 outpatient clinics.6 As the nation’s largest integrated health care system, the VHA approaches cancer care with a single electronic health record system across all of its facilities, featuring comprehensive clinical outcome documentation.7 The VHA’s systemwide DNA sequence platform, through the National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP), also provided an optimal area for research and standardization of precision oncology practices on a national scale.8

Centers of Excellence: An Adaptable Model

The primary thrust of the partnership centers on the PCF-VA COEs, which form the Precision Oncology Program for Cancer of the Prostate (POPCaP) network. Over the last 4 years, PCF-deployed philanthropy has established 12 PCF-VA COEs, located in the Bronx and Manhattan, New York; Tampa Bay, Florida; Los Angeles, California; Seattle, Washington; Chicago, Illinois; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Ann Arbor, Michigan; Durham, North Carolina; Washington, DC; Boston, Massachusetts; and Portland, Oregon. Sites were initially chosen based on strong connections to academic medical centers, National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive care centers, and physician-scientists who were professionally invested in precision prostate cancer oncology. Drawing on PCF’s existing networks helped to identify these areas, which were already rich in human and technological capital, before expanding to areas that were less resource rich. Future health partnerships may therefore consider capitalizing on existing relationships to spark initial growth, which can provide pathways for scaling.

In collaboration with NPOP, COEs work to sequence genomic and somatic tissue from veterans with metastatic prostate cancer, connect patients to appropriate clinical trials and treatment pathways, and advance guidelines for precision cancer care. Certain aspects of COE operations remain constant across all facilities. Annual progress reports, comprising of a written report, slide deck of accomplishments, and bulleted delineation of challenges and future plans are required of all COE-funded investigators. All COEs also are tasked with hiring a center coordinator, instituting a standardized sequencing and mutation reporting protocol, participating in consortium-wide phase 3 studies, and engaging in monthly conference calls to assess progress. A complete list of requirements is found in the Table.

However, the methods through which these goals must be completed is at the discretion of the COE investigators. Each COE, due to institutional and patient variance, experiences distinctive challenges and must mold its practice to fit existing capacities. For example, certain sites optimized workflow by training coordinators to analyze specimens, thereby improving care speed for veteran patients. Other COEs maximized nearby resources by hiring offsite specialists such as genetic counselors and interventional radiologists. By providing the freedom to design site-specific methodology, the PCF-VA partnership allows each COE to meet the award goals through any appropriate path using the funds provided, increasing efficiency and optimizing progress. This diversity of protocol also helped to expand the capabilities of the POPCaP Network, allowing sites to specialize in areas of interest in precision oncology. This eventually helped to inform future initiatives.

Accelerating Clinical Trials

A critical feature of the POPCaP network is the Prostate Cancer Analysis for Therapy Choice (PATCH) plexus.9 Through this investigative umbrella, veterans who are sequenced at any COE are given access to clinical trials at sites across POPCaP. Funding is available to support veteran travel to these sites, decreasing the chance that a veteran’s location is a barrier to treatment. In this way, the PCF-VA partnership continues to broaden treatment scopes for tens of thousands of veterans while simultaneously advancing clinical knowledge of precision oncology.

Fostering a Scientific Community

The PCF-VA partnership’s COE initiative capitalizes on resources from both nonprofit and public sectors to cultivate dynamic scientific discourse and investigative support. Through monthly meetings of the NPOP Molecular Oncology Tumor Board, COE investigators receive guidance and education to better assist veterans sequenced through their programs. Another example of enriched scientific collaboration are the Dream Team investigators, who were collaboratively funded by PCF, Stand Up 2 Cancer, and the American Association for Cancer Research.10 These teams made significant strides in genomic profiling of advanced prostate cancer and outpatient computed tomography-guided metastatic bone biopsy techniques. Through the PCF-VA partnership, COE researchers benefited from these investigators’ insight and expertise during regular check-in calls with investigators. PCF’s Prescription Pad, also connects all investigators to current therapies and trials, better informing them of future directions for their own work (Figure 3).11,12

The PCF-VA partnership also facilitates peer-to-peer communication through regular inperson and virtual meetings of investigators, coordinators, and other stakeholders. These meetings allow the creation of focused working groups composed of COE leaders across the nation. The working groups seek to improve all aspects of functionality, including operational roadblocks, sequencing and phenotyping protocols, and addressing health service disparities. The VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, Washington, and the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center in California both are mentorship sites that play instrumental roles in guiding newer sites through challenges, such as obtaining rapid pathology results and navigating the VA system. This interinvestigator communication also helps to recruit new junior and senior investigators to POPCaP, thereby broadening the network’s reach.

Future Pathways

In line with the mission outlined in the MOU of developing treatments for veteran populations, the PCF-VA partnership has actively pursued addressing veteran health inequities. In 2018, a $2.5 million gift from Robert F. Smith, Founder, Chairman, and Chief Executive Officer of Vista Equity Partners, set up the Chicago COE with the express purpose of serving African American veterans, who represent men at highest risk of prostate cancer incidence and mortality.13 A regularly convened health disparities working group explores future efforts. This group, composed of VA investigators, epidemiologists, geneticists, and other field leaders, seeks to advance the most compelling approaches to eliminate inequities in prostate cancer care.

A novel nursing initiative that focuses on the role of nurses in providing genetic services for prostate cancer is being developed. The need for new genetic care models and significant barriers to genetic service delivery have been well-documented for prostate cancer.14 The initiative provides nurses with opportunities to train with POPCaP and VA geneticists, enroll in a City of Hope genetics course, and to join a collaborative of geneticists, medical oncologists, and nurse practitioners.15 By furthering nursing education and leadership, the initiative empowers nurses to fill the gaps in veteran health care, particularly in genomics-based precision oncology.

The COE platform also has provided the foundation for the building of COEs for other cancers relevant to veterans, such as lung cancer. This expansion of COE function helps to further the VA goal of not only creating COEs, but a system of excellence. More recently, COE infrastructure has been leveraged in the fight against COVID-19 through HITCH, a clinical trial investigating the use of temporary androgen suppression in improving clinical outcomes of veterans with COVID-19.16 This expansion of function also provides a mechanism for COEs to continue to be funded in the future: attracting federal capital, private philanthropy, and industrial support is dependent on realized and expanded goals, as well as demonstrable progress in veteran care.

Conclusions

The PCF-VA partnership serves as an example of a public-private health partnership pursuing strategic pathways and bold goals to ensure that every eligible veteran has access to precision oncology. These pathways include advocacy on the part of executive leadership, recognizing existing economies of scale, building compelling narratives to maximize funding, creating flexible requirements, and facilitating a robust, resource-rich scientific network. This partnership already has opened doors to future initiatives and continues to adapt to a rapidly changing health landscape. The discussed strategies have the potential to inform future health initiatives and showcase how a systemic approach to eradicating health inequities can greatly benefit underserved communities.

The success of the PCF-VA partnership represents more than just an efficient partnership model. The partnership’s emphasis on veterans, who exemplify service, highlights the extent to which cancer patients sacrifice to contribute to medical research. This service necessitates a service in kind: all health stakeholders share the responsibility to rapidly advance therapies and care, both to honor the patients who have come before, and to meet the needs of patients with treatment resistant forms of the disease urgently awaiting precision breakthroughs and cures.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Secretary’s Center for Strategic Partnerships (SCSP): about us. https://www.va.gov/scsp/about/. Updated January 22, 2020. Accessed July 27, 2020.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs. About VA. https://www.va.gov/about_va/mission.asp. Updated August 20, 2015. Accessed July 27, 2020.

3. American Association for Cancer Research. National Cancer Moonshot Initiative. https://www.aacr.org/professionals/policy-and-advocacy/science-policy-government-affairs/national-cancer-moonshot-initiative. Accessed July 30, 2020.

4. Zogby J, Fighting cancer is a Defense Department obligation. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/fighting-cancer-is-our-co_b_837535. Updated May 25, 2011. Accessed July 30, 2020.

5. Colliver V. Lawrence Stupski, former Schwab exec, dies. San Francisco Chronicle June 12, 2013. https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Lawrence-Stupski-former-Schwab-exec-dies-4597329.php. Accessed July 30, 2020.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. About VHA. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp. Updated July 14, 2019. Accessed July 27, 2020.

7. Montgomery B, Rettig M, Kasten J, Muralidhar S, Myrie K, Ramoni R. The Precision Oncology Program for Cancer of the Prostate (POPCaP) Network: a Veterans Affairs/Prostate Cancer Foundation collaboration. Fed Pract. 2020;37 (suppl 4):S48-S53. doi:10.12788/fp.0021

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Oncology Program Office: about us. https://www.cancer.va.gov/CANCER/about.asp. Accessed July 28, 2020.

9. Graff JN, Huang GD. Leveraging Veterans Health Administration clinical and research resources to accelerate discovery and testing in precision oncology. Fed Pract. 2020;37(8):S62-S67. doi:10.12788/fp.0028

10. Prostate Cancer Foundation. Prostate Cancer Foundation and Stand Up To Cancer announce new dream team [press release]. https://www.pcf.org/news/prostate-cancer-foundation-and-stand-up-to-cancer-announce-new-dream-team/. Published April 1, 2020. Accessed July 30, 2020.

11. Quigley DA, Dang HX, Zhao SG, et al. Genomic hallmarks and structural variation in metastatic prostate cancer [published correction appears in Cell. 2018 Oct 18;175(3):889]. Cell. 2018;174(3):758-769.e9. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.039

12. Armenia J, Wankowicz SAM, Liu D, et al. The long tail of oncogenic drivers in prostate cancer [published correction appears in Nat Genet. 2019 Jul;51(7):1194]. Nat Genet. 2018;50(5):645-651. doi:10.1038/s41588-018-0078-z

13. Prostate Cancer Foundation. $2.5 million gift from Robert Frederick Smith to the Prostate Cancer Foundation is the largest donation ever dedicated to advancing prostate cancer research in African-American men [press release]. https://www.pcf.org/news/robert-frederick-smith-gift/. Published January 14, 2018. Accessed July 27, 2020.

14. Carlo MI, Giri VN, Paller CJ, et al. Evolving intersection between inherited cancer genetics and therapeutic clinical trials in prostate cancer: a white paper from the Germline Genetics Working Group of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Consortium. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2018:10.1200/PO.18.00060. doi:10.1200/PO.18.00060

15. City of Hope. Intensive course in genomic cancer risk assessment. https://www.cityofhope.org/education/health-professional-education/cancer-genomics-education-program/intensive-course-in-cancer-risk-assessment-overview. Accessed July 28, 2020.

16. US National Library of Medicine, Clinicaltrial.gov. Hormonal Intervention for the Treatment in Veterans with COVID-19 Requiring Hospitalization (HITCH): NCT04397718. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04397718. Updated July 23, 2020. Accessed July 30, 2020.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Secretary’s Center for Strategic Partnerships (SCSP): about us. https://www.va.gov/scsp/about/. Updated January 22, 2020. Accessed July 27, 2020.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs. About VA. https://www.va.gov/about_va/mission.asp. Updated August 20, 2015. Accessed July 27, 2020.

3. American Association for Cancer Research. National Cancer Moonshot Initiative. https://www.aacr.org/professionals/policy-and-advocacy/science-policy-government-affairs/national-cancer-moonshot-initiative. Accessed July 30, 2020.

4. Zogby J, Fighting cancer is a Defense Department obligation. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/fighting-cancer-is-our-co_b_837535. Updated May 25, 2011. Accessed July 30, 2020.

5. Colliver V. Lawrence Stupski, former Schwab exec, dies. San Francisco Chronicle June 12, 2013. https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Lawrence-Stupski-former-Schwab-exec-dies-4597329.php. Accessed July 30, 2020.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. About VHA. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp. Updated July 14, 2019. Accessed July 27, 2020.

7. Montgomery B, Rettig M, Kasten J, Muralidhar S, Myrie K, Ramoni R. The Precision Oncology Program for Cancer of the Prostate (POPCaP) Network: a Veterans Affairs/Prostate Cancer Foundation collaboration. Fed Pract. 2020;37 (suppl 4):S48-S53. doi:10.12788/fp.0021

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Oncology Program Office: about us. https://www.cancer.va.gov/CANCER/about.asp. Accessed July 28, 2020.

9. Graff JN, Huang GD. Leveraging Veterans Health Administration clinical and research resources to accelerate discovery and testing in precision oncology. Fed Pract. 2020;37(8):S62-S67. doi:10.12788/fp.0028

10. Prostate Cancer Foundation. Prostate Cancer Foundation and Stand Up To Cancer announce new dream team [press release]. https://www.pcf.org/news/prostate-cancer-foundation-and-stand-up-to-cancer-announce-new-dream-team/. Published April 1, 2020. Accessed July 30, 2020.

11. Quigley DA, Dang HX, Zhao SG, et al. Genomic hallmarks and structural variation in metastatic prostate cancer [published correction appears in Cell. 2018 Oct 18;175(3):889]. Cell. 2018;174(3):758-769.e9. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.039

12. Armenia J, Wankowicz SAM, Liu D, et al. The long tail of oncogenic drivers in prostate cancer [published correction appears in Nat Genet. 2019 Jul;51(7):1194]. Nat Genet. 2018;50(5):645-651. doi:10.1038/s41588-018-0078-z

13. Prostate Cancer Foundation. $2.5 million gift from Robert Frederick Smith to the Prostate Cancer Foundation is the largest donation ever dedicated to advancing prostate cancer research in African-American men [press release]. https://www.pcf.org/news/robert-frederick-smith-gift/. Published January 14, 2018. Accessed July 27, 2020.

14. Carlo MI, Giri VN, Paller CJ, et al. Evolving intersection between inherited cancer genetics and therapeutic clinical trials in prostate cancer: a white paper from the Germline Genetics Working Group of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Consortium. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2018:10.1200/PO.18.00060. doi:10.1200/PO.18.00060

15. City of Hope. Intensive course in genomic cancer risk assessment. https://www.cityofhope.org/education/health-professional-education/cancer-genomics-education-program/intensive-course-in-cancer-risk-assessment-overview. Accessed July 28, 2020.

16. US National Library of Medicine, Clinicaltrial.gov. Hormonal Intervention for the Treatment in Veterans with COVID-19 Requiring Hospitalization (HITCH): NCT04397718. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04397718. Updated July 23, 2020. Accessed July 30, 2020.