User login

Current Therapeutic Approaches to Renal Cell Carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common malignancy arising in the kidney, comprising 90% of all renal tumors.1 Approximately 55,000 new RCC cases are diagnosed each year.2 Patients with RCC are often asymptomatic, and most cases are discovered as incidental findings on abdominal imaging performed during evaluation of nonrenal complaints. Limited-stage RCC that is found early can be cured surgically, with estimated 5-year survival rates approaching 90%; however, long-term survival for metastatic disease is poor, with rates ranging from 0% to 20%.2 Advanced RCC is resistant to conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and outcomes for patients with metastatic or unresectable RCC remain poor. However, the recent development of new therapeutic modalities that target tumor molecular pathways has expanded the treatment options for these patients and changed the management of RCC.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLASSIFICATION

Median age at diagnosis in the United States is 64 years. Men have a higher incidence of RCC than women, with the highest incidence seen in American Indian and Alaska Native men (30.1 per 100,000 population). Genetic syndromes account for 2% to 4% of all RCCs.2 Risk factors for RCC include smoking, hypertension, obesity, and acquired cystic kidney disease that is associated with end-stage renal failure.3 Longer duration of tobacco use is associated with a more aggressive course.

The 2004 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of renal tumors summarizes the previous classification systems (including the Heidelberg and Mainz classification systems) to describe different categories of RCC based on histologic and molecular genetics characteristics.2 Using the WHO classification criteria, RCC comprises 90% of all renal tumors, with clear cell being the most common type (80%).2 Other types of renal tumors include papillary, chromophobe, oncocytoma, and collecting-duct or Bellini duct tumors. Approximately 3% to 5% of tumors are unclassified. Oncocytomas are generally considered benign, and chromophobe tumors typically have an indolent course and rarely metastasize. Sarcomatoid differentiation can be seen in any histologic type and is associated with a worse prognosis. While different types of tumors may be seen in the kidney (such as transitional cell or lymphomas), the focus of this review is the primary malignancies of the renal parenchyma.

FAMILIAL SYNDROMES

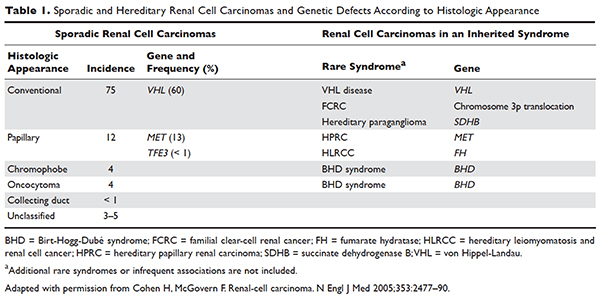

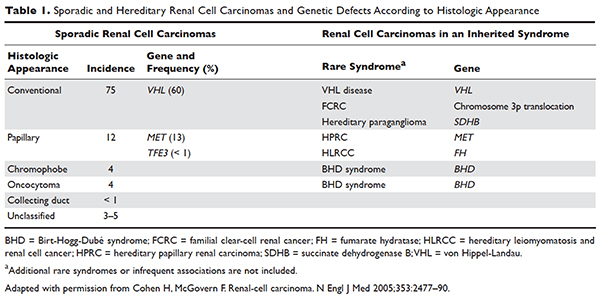

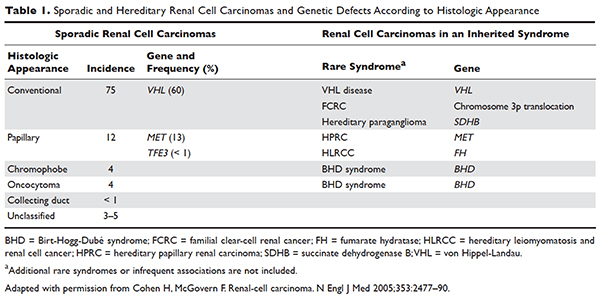

Several genetic syndromes have been identified by studying families with inherited RCC. Among these, von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene mutation is the most commonly found inherited genetic defect. Table 1 summarizes the incidence of gene mutations and the corresponding histologic appearance of the most common sporadic and hereditary RCCs.4

VHL disease is an autosomal dominant familial syndrome. Patients with this mutation are at higher risk for developing RCC (clear cell histology), retinal angiomas, pheochromocytomas, as well as hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system (CNS).4 Of all the genetic mutations seen in RCC, the somatic mutation in the VHL tumor-suppressor gene is by far the most common.5 VHL targets hypoxia–inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-α) for ubiquitination and subsequent degradation, which has been shown to suppress the growth of clear-cell RCC in mouse models.6–8 HIF expression under hypoxic conditions leads to activation of a number of genes important in blood vessel development, cell proliferation, and glucose metabolism, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), erythropoietin, platelet-derived growth factor beta (PDGF-β), transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-α), and glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1). Mutation in the VHL gene prevents degradation of the HIF-α protein, thereby leading to increased expression of these downstream proteins, including MET and Axl. The upregulation of these angiogenic factors is thought to be the underlying process for increased vascularity of CNS hemangioblastomas and clear-cell renal tumors in VHL disease.4–8

Other less common genetic syndromes seen in hereditary RCC include hereditary papillary RCC, hereditary leiomyomatosis, and Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome.9 In hereditary papillary RCC, the MET gene is mutated. BHD syndrome is a rare, autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by hair follicle hamartomas of the face and neck. About 15% of patients have multiple renal tumors, the majority of which are of the chromophobe or mixed chromophobe-oncocytoma histology. The BHD gene encodes the protein folliculin, which is thought to be a tumor-suppressor gene.

DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING

CASE PRESENTATION

A 74-year-old man who works as an airplane mechanic repairman presents to the emergency department with sudden worsening of chronic right upper arm and shoulder pain after lifting a jug of orange juice. He does not have a significant past medical history and initially thought that his pain was due to a work-related injury. Upon initial evaluation in the emergency department he is found to have a fracture of his right humerus. Given that the fracture appears to be pathologic, further work-up is recommended.

• What are common clinical presentations of RCC?

Most patients are asymptomatic until the disease becomes advanced. The classic triad of flank pain, hematuria, and palpable abdominal mass is seen in approximately 10% of patients with RCC, partly because of earlier detection of renal masses by imaging performed for other purposes.10 Less frequently, patients present with signs or symptoms of metastatic disease such as bone pain or fracture (as seen in the case patient), painful adenopathy, and pulmonary symptoms related to mediastinal masses. Fever, weight loss, anemia, and/or varicocele often occur in young patients (≤ 46 years) and may indicate the presence of a hereditary form of the disease. Patients may present with paraneoplastic syndromes seen as abnormalities on routine blood work. These can include polycythemia or elevated liver function tests (LFTs) without the presence of liver metastases (known as Stauffer syndrome), which can be seen in localized renal tumors. Nearly half (45%) of patients present with localized disease, 25% present with locally advanced disease, and 30% present with metastatic disease.11 Bone is the second most common site of distant metastatic spread (following lung) in patients with advanced RCC.

• What is the approach to initial evaluation for a patient with suspected RCC?

Initial evaluation consists of a physical exam, laboratory tests including complete blood count (CBC) and comprehensive metabolic panel (calcium, serum creatinine, LFTs, lactate dehydrogenase [LDH], and urinalysis), and imaging. Imaging studies include computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and chest imaging. A chest radiograph may be obtained, although a chest CT is more sensitive for the presence of pulmonary metastases. MRI can be used in patients with renal dysfunction to evaluate the renal vein and inferior vena cava (IVC) for thrombus or to determine the presence of local invasion.12 Although bone and brain are common sites for metastases, routine imaging is not indicated unless the patient is symptomatic. The value of positron emission tomography in RCC remains undetermined at this time.

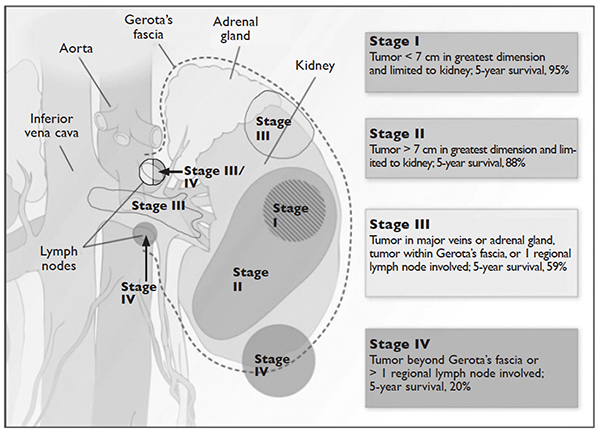

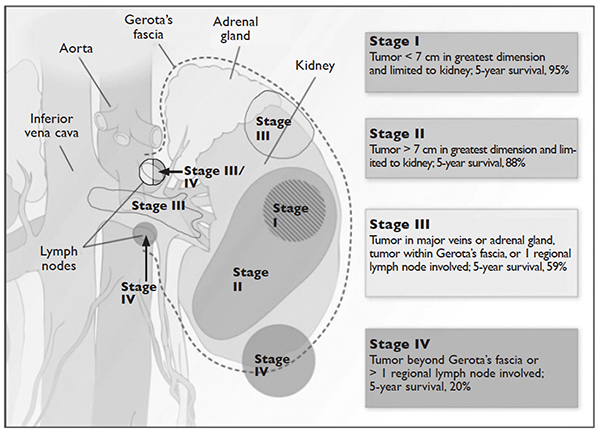

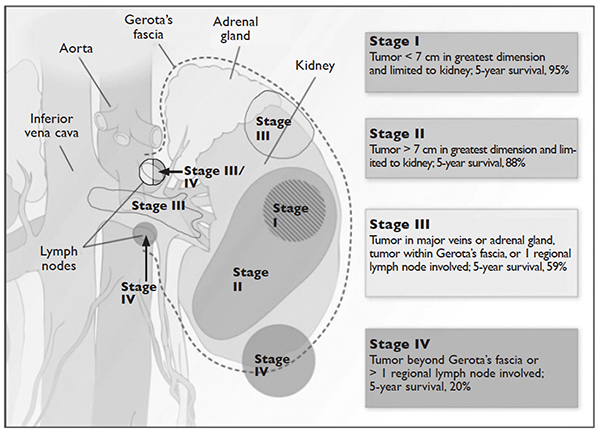

Staging is done according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging classification for RCC; the Figure summarizes the staging and 5-year survival data based on this classification scheme.4,13

J Med 2005;353:2477–90.)

LIMITED-STAGE DISEASE

• What are the therapeutic options for limited-stage disease?

For patients with nondistant metastases, or limited-stage disease, surgical intervention with curative intent is considered. Convention suggests considering definitive surgery for patients with stage I and II disease, select patients with stage III disease with pathologically enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes, patients with IVC and/or cardiac atrium involvement of tumor thrombus, and patients with direct extension of the renal tumor into the ipsilateral adrenal gland if there is no evidence of distant disease. While there may be a role for aggressive surgical intervention in patients with distant metastatic disease, this topic will not be covered in this review.

SURGICAL INTERVENTION

Once patients are determined to be appropriate candidates for surgical removal of a renal tumor, the urologist will perform either a radical nephrectomy or a nephron-sparing nephrectomy, also called a partial nephrectomy. The urologist will evaluate the patient based on his or her body habitus, the location of the tumor, whether multiple tumors in one kidney or bilateral tumors are present, whether the patient has a solitary kidney or otherwise impaired kidney function, and whether the patient has a history of a hereditary syndrome involving kidney cancer as this affects the risk of future kidney tumors.

A radical nephrectomy is surgically preferred in the presence of the following factors: tumor larger than 7 cm in diameter, a more centrally located tumor, suspicion of lymph node involvement, tumor involvement with renal vein or IVC, and/or direct extension of the tumor into the ipsilateral adrenal gland. Nephrectomy involves ligation of the vascular supply (renal artery and vein) followed by removal of the kidney and surrounding Gerota’s fascia. The ipsilateral adrenal gland is removed if there is a high-risk for or presence of invasion of the adrenal gland. Removal of the adrenal gland is not standard since the literature demonstrates there is less than a 10% chance of solitary, ipsilateral adrenal gland involvement of tumor at the time of nephrectomy in the absence of high-risk features, and a recent systematic review suggests that the chance may be as low as 1.8%.14 Preoperative factors that correlated with adrenal involvement included upper pole kidney location, renal vein thrombosis, higher T stage (T3a and greater), multifocal tumors, and evidence for distant metastases or lymph node involvement. Lymphadenectomy previously had been included in radical nephrectomy but now is performed selectively. Radical nephrectomy may be performed as

either an open or laparoscopic procedure, the latter of which may be performed robotically.15 Oncologic outcomes appear to be comparable between the 2 approaches, with equivalent 5-year cancer-specific survival (91% with laparoscopic versus 93% with open approach) and recurrence-free survival (91% with laparoscopic versus 93% with open approach).16 The approach ultimately is selected based on provider- and patient-specific input, though in all cases the goal is to remove the specimen intact.16,17

Conversely, a nephron-sparing approach is preferred for tumors less than 7 cm in diameter, for patients with a solitary kidney or impaired renal function, for patients with multiple small ipsilateral tumors or with bilateral tumors, or for radical nephrectomy candidates with comorbidities for whom a limited intervention is deemed to be a lower-risk procedure. A nephron-sparing procedure may also be performed open or laparoscopically. In nephron-sparing procedures, the tumor is removed along with a small margin of normal parenchyma.15

In summary, the goal of surgical intervention is curative intent with removal of the tumor while maintaining as much residual renal function as possible to limit long-term morbidity of chronic kidney disease and associated cardiovascular events.18 Oncologic outcomes for radical nephrectomy and partial nephrectomy are similar. In one study, overall survival was slightly lower in the partial nephrectomy cohort, but only a small number of the deaths were due to RCC.19

ADJUVANT THERAPY

Adjuvant systemic therapy currently has no role following nephrectomy for RCC because no systemic therapy has been able to reduce the likelihood of relapse. Randomized trials of cytokine therapy (eg, interferon, interleukin 2) or tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; eg, sorafenib, sunitinib) with observation alone in patients with locally advanced completely resected RCC have shown no delay in time to relapse or improvement of survival with adjuvant therapy.20 Similarly, adjuvant radiation therapy has not shown benefit even in patients with nodal involvement or incomplete resection.21 Therefore, observation remains the standard of care after nephrectomy.

RENAL TUMOR ABLATION

For patients who are deemed not to be surgical candidates due to age, comorbidities, or patient preference and who have tumors less than 4 cm in size (stage I tumors), ablative techniques may be considered. The 2 most well-studied and effective techniques at present are cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Microwave ablation may be an option in some facilities, but the data in RCC are limited. An emerging ablative technique under investigation is irreversible electroporation. At present, the long-term efficacy of all ablative techniques is unknown.

Patient selection is undertaken by urologists and interventional radiologists who evaluate the patient with ultrasound, CT, and/or MRI to determine the location and size of the tumor and the presence or absence of metastatic disease. A pretreatment biopsy is recommended to document the histology of the lesion to confirm a malignancy and to guide future treatment for recurrent or metastatic disease. Contraindications to the procedure include the presence of metastatic disease, a life expectancy of less than 1 year, general medical instability, or uncorrectable coagulopathy due to increased risk of bleeding complications. Tumors in close proximity to the renal hilum or collecting system are a contraindication to the procedure because of the risk for hemorrhage or damage to the collecting system. The location of the tumor in relation to the vasculature is also important to maximize efficacy because the vasculature acts as a “heat sink,” causing dissipation of the thermal energy. Occasionally, stenting of the proximal ureter due to upper tumor location is necessary to prevent thermal injury that could lead to urine leaks.

Selection of the modality to be used primarily depends on operator comfort, which translates to good patient outcomes, such as better cancer control and fewer complications. Cryoablation and RFA have both demonstrated good clinical efficacy and cancer control of 89% and 90%, respectively, with comparable complication rates.22 There have been no studies performed directly comparing the modalities.

Cryoablation

Cryoablation is performed through the insertion of a probe into the tumor, which may be done through a surgical or percutaneous approach. Once the probe is in place, a high- pressure gas (argon, nitrogen) is passed through the probe and upon entering a low pressure region the gas cools. The gas is able to cool to temperatures as low as –185°C. The tissue is then rewarmed through the use of helium, which conversely warms when entering a low pressure area. The process of freezing followed by rewarming subsequently causes cell death/tissue destruction through direct cell injury from cellular dehydration and vascular injury. Clinically, 2 freeze-thaw cycles are used to treat a tumor.23,24

RFA

Radiofrequency ablation, or RFA, targets tumors via an electrode placed within the mass that produces intense frictional heat from medium-frequency alternating current (approximately 500 kHz) produced by a connected generator that is grounded on the patient. The thermal energy created causes coagulative necrosis. Due to the reliance on heat for tumor destruction, central lesions are less amenable to this approach because of the “heat sink” effect from the hilum.24

Microwave Ablation

Microwave ablation, like RFA, relies on the generation of frictional heat to cause cell death by coagulative necrosis. In this case, the friction is created through the activation of water molecules; because of the different thermal kinetics involved with microwave ablation, the “heat sink” effect is minimized when treatment is employed near large vessels, in comparison to RFA.24 The data on this mechanism of ablation are still maturing, with varied outcomes thus far. One study demonstrated outcomes comparable to RFA and cryoablation, with cancer-specific survival of 97.8% at 3 years.25 However, a study by Castle and colleagues26 demonstrated higher recurrence rates. The overarching impediment to widespread adoption of microwave ablation is inconclusive data gleaned from studies with small numbers of patients with limited follow up. The role of this modality will need to be revisited.

Irreversible Electroporation

Irreversible electroporation (IRE) is under investigation. IRE is a non-thermal ablative technique that employs rapid electrical pulses to create pores in cell membranes, leading to cell death. The postulated benefits of IRE include the lack of an effect from “heat sinks” and less collateral damage to the surrounding tissues, when compared with the thermal modalities. In a human phase 1 study of patients undergoing IRE prior to immediate surgical resection, the procedure appeared feasible and safe.27 Significant concerns for this method of ablation possibly inducing cardiac arrhythmias, and the resultant need for sedation with neuromuscular blockade and associated electrocardiography monitoring, may impede its implementation in nonresearch settings.24

ACTIVE SURVEILLANCE

Due to the more frequent use of imaging for various indications, there has been an increase in the discovery of small renal masses (SRM); 85% of RCC that present in an asymptomatic or incidental manner are tumors under 4 cm in diameter.28,29 The role of active surveillance is evolving, but is primarily suggested for patients who are not candidates for more aggressive intervention based on comorbidities. A recent prospective, nonrandomized analysis of data from the Delayed Intervention and Surveillance for Small Renal Masses (DISSRM) registry evaluated outcomes for patients with SRM looking at primary intervention compared with active surveillance.30 The primary intervention selected was at the discretion of the provider; treatments included partial nephrectomy, RFA, and cryoablation, and active surveillance patients were followed with imaging every 6 months. Progression of SRM, with recommendation for delayed intervention, was defined as a growth rate of mass greater than 0.5 cm/year, size greater than 4 cm, or hematuria. Thirty-six of 158 patients on active surveillance met criteria for progression; 21 underwent delayed intervention. Of note, even the patients who progressed but did not undergo delayed intervention did not develop metastatic disease during the follow-up interval. With a median follow-up of 2 years, cancer-specific survival was noted to be 99% and 100% at 5 years for primary intervention and active surveillance, respectively. Overall survival at 2 years for primary intervention was 98% and 96% for active surveillance; at 5 years, the survival rates were 92% and 75% (P = 0.06). Of note, 2 patients in the primary intervention arm died of RCC, while none in the active surveillance arm died. As would be expected, active surveillance patients were older, had a worse performance status, and had more comorbidities. Interestingly, 40% of patients enrolled selected active surveillance as their preferred management for SRM. The DISSRM results were consistent with data from the Renal Cell Consortium of Canada and other retrospective reviews.31–33

• What is the approach to follow-up after treatment of localized RCC?

After a patient undergoes treatment for a localized RCC, the goal is to optimize oncologic outcomes, monitor for treatment sequelae, such as renal failure, and focus on survivorship. At this time, there is no consensus in the literature or across published national and international guidelines with regards to the appropriate schedule for surveillance to achieve these goals. In principle, the greatest risk for recurrence occurs within the first 3 years, so many guidelines focus on this timeframe. Likewise, the route of spread tends to be hematogenous, so patients present with pulmonary, bone, and brain metastases, in addition to local recurrence within the renal bed. Symptomatic recurrences often are seen

with bone and brain metastases, and thus bone scans and brain imaging are not listed as part of routine surveillance protocols in asymptomatic patients. Although there is inconclusive evidence that surveillance protocols improve outcomes in RCC, many professional associations have outlined recommendations based on expert opinion.34 The American Urological Association released guidelines in 2013 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) released their most recent set of guidelines in 2016.21,35 These guidelines use TNM staging to risk-stratify patients and recommend follow-up.

METASTATIC DISEASE

CASE CONTINUED

CT scan with contrast of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis as well as bone scan are done. CT of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrates a 7.8-cm left renal mass arising from the lower pole of the left kidney. Paraesophageal lymphadenopathy and mesenteric nodules are also noted. CT of the chest demonstrates bilateral pulmonary emboli. Bone scan is significant for increased activity related to the pathological fracture involving the right humerus. The patient undergoes surgery to stabilize the pathologic fracture of his humerus. He is diagnosed with metastatic RCC (clear cell histology) and undergoes palliative debulking nephrectomy.

• How is prognosis defined for metastatic RCC?

PROGNOSTIC MODELS

Limited-stage RCC that is found early can be cured surgically, with estimated 5-year survival rates for stage T1 and T2 disease approaching 90%; however, long-term survival for metastatic disease is poor, with rates ranging from 0% to 20%.13 Approximately 30% of patients have metastatic disease at diagnosis, and about one-third of patients who have undergone treatment for localized disease experience relapse.36,37 Common sites of metastases include lung, lymph nodes, bone, liver, adrenal gland, and brain.

Prognostic scoring systems have been developed to define risk groups and assist with determining appropriate therapy in the metastatic setting. The most widely used validated prognostic factor model is that from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), which was developed using a multivariate analysis derived from data of patients enrolled in clinical trials and treated with interferon alfa.38 The factors included in the MSKCC model are Karnofsky performance status less than 80, time from diagnosis to treatment with interferon alfa less than 12 months, hemoglobin level less than lower limit of laboratory’s reference range, LDH level greater than 1.5 times the upper limit of laboratory’s reference range, and corrected serum calcium level greater than 10 mg/dL. Risk groups are categorized as favorable (0 risk factors), intermediate (1 to 2 risk factors), and poor (3 or more risk factors).39 Median survival for favorable-, intermediate-, and poor-risk patients was 20, 10, and 4 months, respectively.40

Another prognostic model, the International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium, or Heng, model was developed to evaluate prognosis in patients treated with VEGF-targeted therapy.41 This model was developed from a retrospective study of patients treated with sunitinib, sorafenib, and bevacizumab plus interferon alfa or prior immunotherapy. Prognostic factors in this model include 4 of the 5 MSKCC risk factors (hemoglobin level, corrected serum calcium level, Karnofsky performance status, and time to initial diagnosis). Additionally, this model includes both absolute neutrophil and platelet counts greater than the upper limit of normal. Risk groups are identified as favorable (0 risk factors), intermediate (1 to 2 risk factors), and poor (3 or more risk factors). Median survival for favorable-, intermediate-, and poor-risk patients was not reached, 27 months, and 8.8 months, respectively. The University of California, Los Angeles scoring algorithm to predict survival after nephrectomy and immunotherapy (SANI) in patients with metastatic RCC is another prognostic model that can be used. This simplified scoring system incorporates lymph node status, constitutional symptoms, metastases location, histology, and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level.42

The role of debulking or cytoreductive nephrectomy in treatment of metastatic RCC is well established. Large randomized studies have demonstrated a statistically significant median survival benefit for patients undergoing nephrectomy plus interferon alfa therapy compared with patients treated with interferon alfa alone (13.6 months versus 7.8 months, respectively).43 The role of cytoreductive nephrectomy in combination with antiangiogenic agents is less clear. While a retrospective study investigating outcomes of patients with metastatic RCC receiving anti-VEGF agents showed a prolonged survival with nephrectomy, results of large randomized trials are not yet available.44,45 Patients with lung-only metastases, good prognostic features, and a good performance status are historically the most likely to benefit from cytoreductive surgery.

CASE CONTINUED

Based on the MSKCC prognostic factor model, the patient is considered to be in the intermediate-risk group (Karnofsky performance status of 80, calcium 9.5 mg/dL, LDH 204 U/L, hemoglobin 13.6 g/dL). He is started on treatment for his bilateral pulmonary emboli and recovers well from orthopedic surgery as well as palliative debulking nephrectomy.

• What is the appropriate first-line therapy in managing this patient’s metastatic disease?

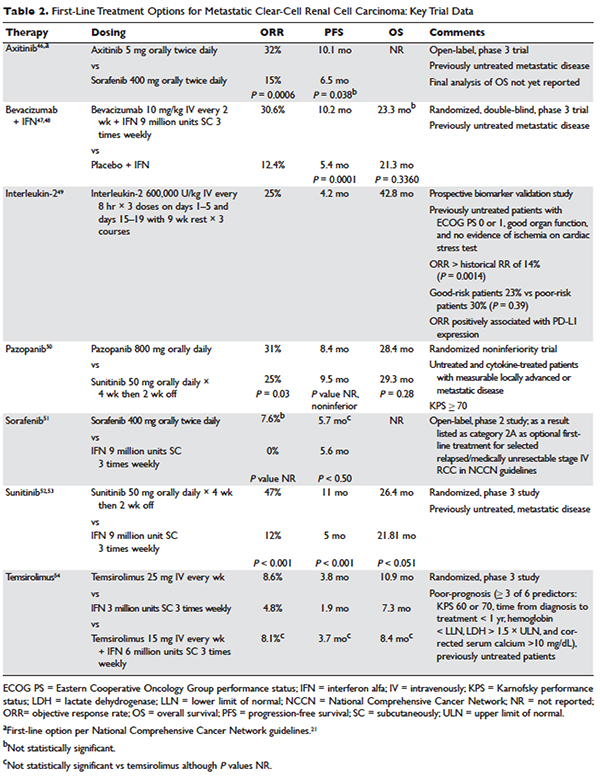

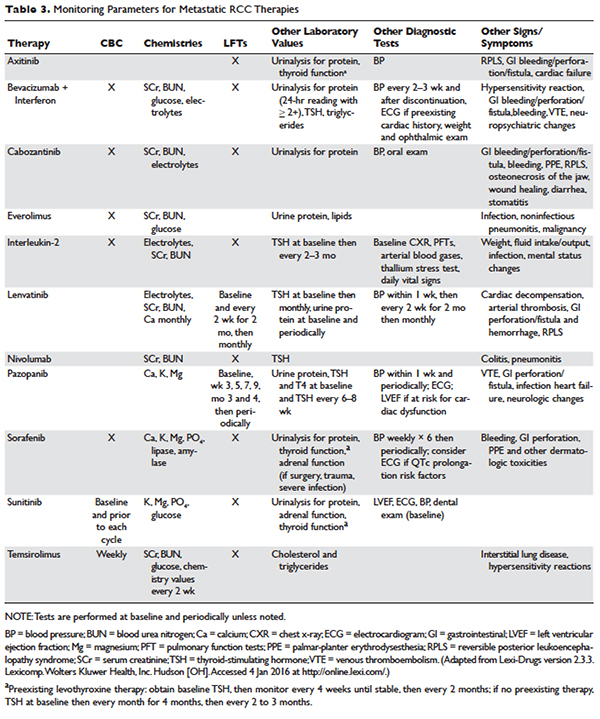

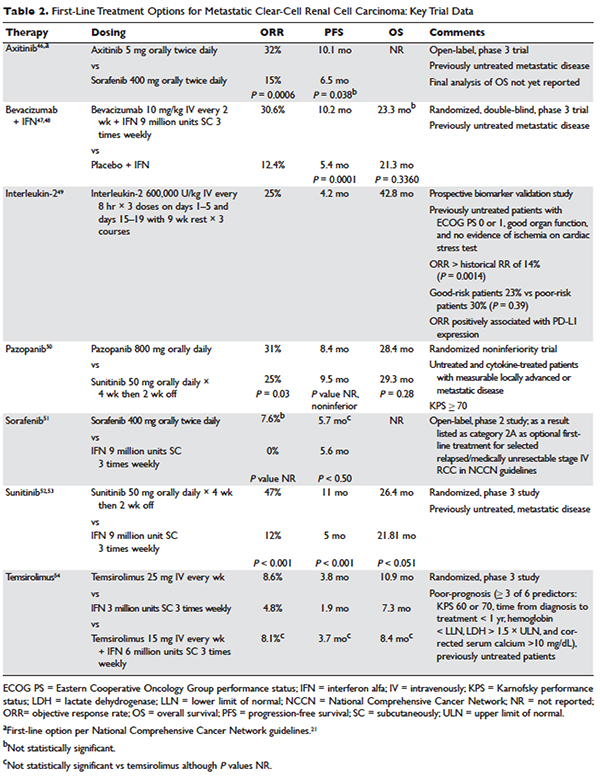

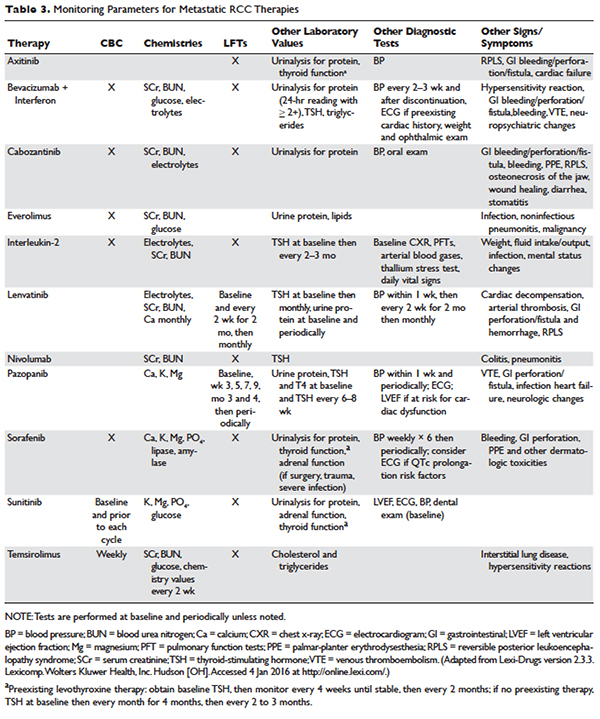

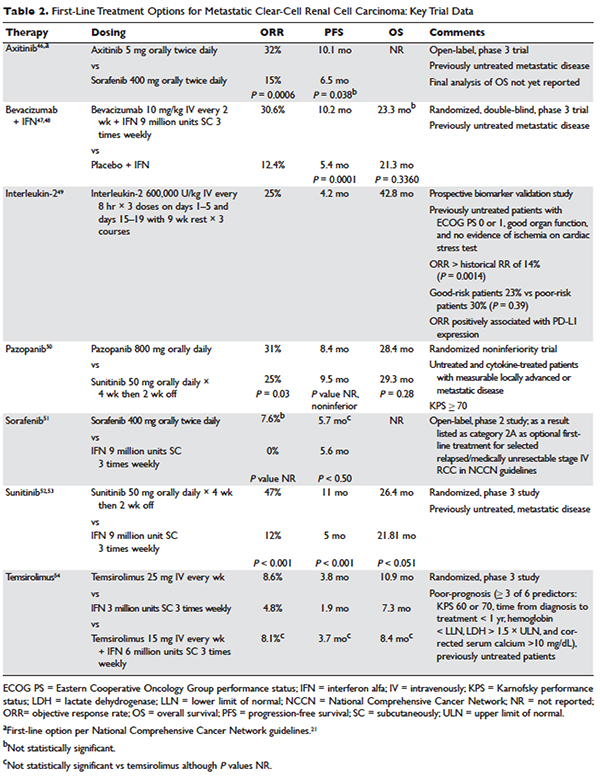

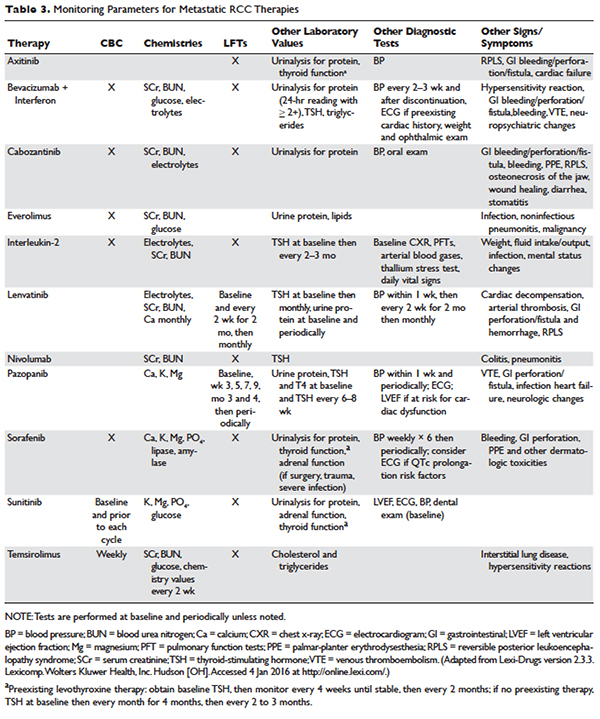

Several approaches to systemic therapy for advanced RCC have been taken based on the histologic type of the tumor. Clear-cell is by far the predominant histologic type in RCC. Several options are available as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic clear-cell RCC (Table 2).46–54 These include biologic agents such as high-dose interleukin-2 (IL-2) immune therapy, as well as targeted therapies including TKIs and anti-VEGF antibodies. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor temsirolimus is recommended as first-line therapy in patients with poor prognosis only. Second-line therapies for clear-cell RCC following antiangiogenic therapy include TKIs, mTOR inhibitors, nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor), and the combination of the TKI lenvatinib and mTOR inhibitor everolimus.55 In addition, after initial cytokine therapy, TKIs, temsirolimus, and the anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab are other treatment options available to patients. Best supportive care should always be provided along with initial and subsequent therapies. Clinical trials are also an appropriate choice as first-line or subsequent therapies. All of these therapies require periodic monitoring to prevent and quickly treat adverse effects. Table 3 lists recommended monitoring parameters for each of these agents.56

Based on several studies, TKIs seem to be less effective in patients with non–clear-cell type histology.57,58 In these patients, risk factors can guide therapy. In the ASPEN trial, where 108 patients were randomly assigned to everolimus or sunitinib, patients in the good- and intermediate-risk groups had longer overall and median progression-free survival (PFS) on sunitinib (8.3 months versus 5.3 months, respectively). However, those in the poor-risk group had a longer median overall survival with everolimus.59 Given that the role of targeted therapies in non–clear-cell RCCs is less well established, enrollment in clinical trials should be considered as a first-line treatment option.21

Sarcomatoid features can be observed in any of the histologic types of RCC, and RCC with these features has an aggressive course and a poor prognosis. Currently, there is no standard therapy for treatment of patients with metastatic or unresectable RCC with sarcomatoid features.60 Chemotherapeutic regimens used for soft tissue sarcomas, including a trial of ifosfamide and doxorubicin, did not show any objective response.61 A small trial of 10 patients treated with doxorubicin and gemcitabine resulted in complete response in 2 patients and partial response in 1 patient.62

Enrollment in a clinical trial remains a first-line treatment option for these patients. More recently, a phase 2 trial of sunitinib and gemcitabine in patients with sarcomatoid (39 patients) and/or poor-risk (33 patients) metastatic RCC showed overall response rates (ORR) of 26% and 24%, respectively. A higher clinical benefit rate (defined as ORR plus stable disease) was seen in patients with tumors containing more than 10% sarcomatoid histology, as compared with patients whose tumors contained less than 10% sarcomatoid histology. Neutropenia (n = 20), anemia (n = 10), and fatigue (n = 7) were the most common grade 3 toxicities seen in all the patients. Although this was a small study, the results showed a trend towards better efficacy of the combination therapy as compared with the single-agent regimen. Currently, another study is underway to further investigate this in a larger group of patients.63

BIOLOGICS

Cytokine therapy, including high-dose IL-2 and interferon alfa, had long been the only first-line treatment option for patients with metastatic or unresectable RCC. Studies of high-dose IL-2 have shown an ORR of 25% and durable response in up to 11% of patients with clear-cell histology.64 Toxicities were similar to those previously observed with high-dose IL-2 treatment; the most commonly observed grade 3 toxicities were hypotension and capillary leak syndrome. IL-2 requires strict monitoring (Table 3). It is important to note that retrospective studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of using IL-2 as second-line treatment in patients previously treated with TKIs demonstrated significant toxicity without achieving partial or complete response in any of the patients.65

Prior to the advent of TKIs in the treatment of RCC, interferon alfa was a first-line treatment option for those who could not receive high-dose IL-2. It has been shown to produce response rates of approximately 20%, with maximum response seen with a higher dose range of 5 to 20 million units daily in 1 study.66,67 However, with the introduction of TKIs, which produce a higher and more durable response, interferon alfa alone is no longer recommended as a treatment option.

VEGF MONOCLONAL ANTIBODIES

Bevacizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that binds and neutralizes VEGF-A. Given overexpression of VEGF in RCC, the role of bevacizumab both as a single agent and in combination with interferon alfa has been investigated. In a randomized phase 2 study involving patients with cytokine-refractory disease, bevacizumab produced a 10% response rate and PFS of 4.8 months compared to patients treated with placebo.68 In the AVOREN trial, the addition of bevacizumab (10 mg/kg intravenously [IV] every 2 weeks) to interferon alfa (9 million units subcutaneously [SC] 3 times weekly) was shown to significantly increase PFS compared with interferon alfa alone (10.2 months versus 5.4 months; P = 0.0001).47,48 Adverse effects of this combination therapy include fatigue and asthenia. Additionally, hypertension, proteinuria, and bleeding occurred.

TYROSINE KINASE INHIBITORS

TKIs have largely replaced IL-2 as first-line therapy for metastatic RCC. Axitinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, and sunitinib and can be used as first-line therapy. All of the TKIs can be used as subsequent therapy.

Sunitinib

Sunitinib is an orally administered TKI that inhibits VEGF receptor (VEGFR) types 1 and 2, PDGF receptors (PDGFR) α and β, stem cell factor receptor (c-Kit), and FLT-3 and RET kinases. Motzer and colleagues52,53 compared sunitinib 50 mg daily orally for 4 weeks with 2 weeks off to the then standard of care, interferon alfa 9 million units SC 3 times weekly. Sunitinib significantly increased the overall objective response rate (47% versus 12%; P < 0.001), PFS (11 versus 5 months; P < 0.001), and overall survival (26.4 versus 21.8 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.821). The most common side effects are diarrhea, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, anorexia, hypertension, stomatitis, and hand-foot syndrome, occurring in more than 30% of patients. Often patients will require dose reductions or temporary discontinuations to tolerate therapy. Alternative dosing strategies (eg, 50 mg dose orally daily for 2 weeks alternating with 1-week free interval) have been attempted but not prospectively evaluated for efficacy.69–71

Pazopanib

Pazopanib is an oral multi-kinase inhibitor of VEGFR types 1 and 2, PDGFR, and c-KIT. Results of a phase 3 trial comparing pazopanib (800 mg orally daily) to placebo favored the TKI, with a PFS of 9.2 months versus 4.2 months. A subset of treatment-naïve patients had a longer PFS of 11.1 versus 2.8 months and a response rate of 32% versus 4%.72 This led to a noninferiority phase 3 trial comparing pazopanib with sunitinib as first-line therapy.50 In this study, PFS was similar (8.4 versus 9.5 months; HR 1.05), and overall safety and quality-of-life endpoints favored pazopanib. Much less fatigue, stomatitis, hand-foot syndrome, and thrombocytopenia occurred with pazopanib, whereas hair color changes, weight loss, alopecia, and elevations of LFT enzymes occurred more frequently with pazopanib. Hypertension is common with the administration of pazopanib as well.

Sorafenib

Sorafenib is an orally administered inhibitor of Raf, serine/threonine kinase, VEGFR, PDGFR, FLT-3, c-Kit, and RET. The pivotal phase 3 Treatment Approaches in Renal Cancer Global Evaluation Trial (TARGET) compared sorafenib (400 mg orally twice daily) with placebo in patients who had progressed on prior cytokine-based therapy.73 A final analysis, which excluded patients who were allowed to cross over therapies, found improved overall survival times (14.3 versus 1.8 months, P = 0.029).51 Sorafenib is associated with lower rates of diarrhea, rash, fatigue, hand-foot syndrome, alopecia, hypertension, and nausea than sunitinib, although these agents have not been compared to one another.

Axitinib

Axitinib is an oral inhibitor of VEGFRs 1, 2, and 3. Results of the phase 3 AXIS trial comparing axitinib (5 mg orally twice daily) with sorafenib (400 mg orally twice daily) in patients receiving 1 prior systemic therapy showed axitinib was more active than sorafenib in improving ORR (19% versus 9%; P = 0.001) and PFS (6.7 versus 4.7 months; P < 0.001), although no difference in overall survival times was noted.74 In a subsequent phase 3 trial comparing these drugs in the first-line setting, axitinib showed a nonsignificantly higher response rate and PFS. Despite this, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines consider axitinib an acceptable first-line therapy because activity with acceptable toxicity was demonstrated (Table 2).46 The most common adverse effects of axitinib are diarrhea, hypertension, fatigue, decreased appetite, dysphonia, hypothyroidism, and upper abdominal pain.

CABOZANTINIB

Given that resistance eventually develops in most patients treated with standard treatments, including bevacizumab and TKIs, the need to evaluate the safety and efficacy of novel agents targeting VEGFR and overcoming this resistance is of vital importance. Cabozantinib is an oral small-molecule inhibitor of VEGFR, Met, and Axl, all tyrosine kinases implicated in metastatic RCC. Overexpression of Met and Axl, which occurs as a result of inactivation of the VHL gene, is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with RCC. In a

randomized, open label, phase 3 trial of cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced RCC, Choueiri and colleagues75 compared the efficacy of cabozantinib with everolimus in patients with metastatic RCC who had progressed on previous VEGFR-targeted therapies. In this study, 658 patients were randomly assigned to receive cabozantinib (60 mg orally daily) or everolimus (10 mg orally daily). Results of the study found that PFS was longer with cabozantinib in patients who had previously been treated with other TKIs (median PFS of 7.4 months versus 3.8 months; HR 0.58), corresponding to a 42% reduction in the rate of disease progression or death. The most common grade 3 and 4 toxicities seen with cabozantinib were similar to its class effect and consisted of hypertension, diarrhea, and fatigue. In the final analysis of the data, the median overall survival was 21.4 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 18.7–not estimable) with cabozantinib and 16.5 months (95% CI 14.7 to 18.8) with everolimus (HR 0.66 [95% CI 0.53 to 0.83]; P = 0.00026). The median follow-up for overall survival and safety was 18.7 months. These results highlight the importance of cabozantinib as a first line option in treatment of previously treated patients with advanced RCC.76

MTOR INHIBITORS

The mTOR inhibitors, temsirolimus and everolimus, are also approved for the treatment of metastatic or advanced RCC. These drugs block mTOR’s phosphorylation and subsequent translation of mRNA to inhibit cell proliferation, cell growth, and angiogenesis.77 Temsirolimus can be used as first-line therapy for patients with a poor prognosis, and everolimus is appropriate as a subsequent therapy.

Temsirolimus is an intravenous prodrug of rapamycin. It was the first of the class to be approved for metastatic RCC for treatment-naïve patients with a poor prognosis (ie, at least 3 of 6 predictors of poor survival based on MSKCC model).54 The pivotal ARCC trial compared temsirolimus (25 mg IV weekly) alone, interferon alfa (3 million units SC 3 times weekly) alone, or the combination (temsirolimus 15 mg IV weekly plus interferon alfa 6 million units SC 3 times weekly). In this trial, temsirolimus monotherapy produced a significantly longer overall survival time than interferon alfa alone (10.9 versus 7.3 months; P = 0.008) and improved PFS time when administered alone or in combination with interferon alfa (3.8 and 3.7 months, respectively, versus 1.9 months). Because no real efficacy advantage of the combination was demonstrated, temsirolimus is administered alone. The most common adverse effects of temsirolimus are asthenia, rash, anemia, nausea, anorexia, pain, and dyspnea. Additionally, hyperglycemia, hyper-cholesterolemia, and hyperlipidemia occur with these agents. Noninfectious pneumonitis is a rare but often fatal complication.

Everolimus is also an orally administered derivative of rapamycin that is approved for use after failure of VEGF-targeted therapies. The results of the landmark trial RECORD-1 demonstrated that everolimus (10 mg orally daily) is effective at prolonging PFS (4 versus 1.9 months; P < 0.001) when compared with best supportive care, a viable treatment option at the time of approval.78 The most common adverse effects of everolimus are stomatitis, rash, fatigue, asthenia, and diarrhea. As with temsirolimus, elevations in glucose, lipids, and triglycerides and noninfectious pneumonitis can occur.

TKI + MTOR INHIBITOR

Lenvatinib is also a small molecule targeting multiple tyrosine kinases, primarily VEGF2. Combined with the mTOR inhibitor everolimus, it has been shown to be an effective regimen in patients with metastatic RCC who have failed other therapies. In a randomized phase 2 study involving patients with advanced or metastatic clear-cell RCC, patients were randomly assigned to receive either lenvatinib (24 mg/day), everolimus (10 mg/day), or lenvatinib plus everolimus (18 mg/day and 5 mg/day, respectively). Patients received the treatment continuously on a 28-day cycle until progression or inability to tolerate toxicity. Patients in the lenvatinib plus everolimus arm had median PFS of 14.6 months (95% CI 5.9 to 20.1) versus 5.5 months (95% CI 3.5 to 7.1) with everlolimus alone (HR 0.40 [95% CI 0.24 to 0.68]; P = 0.0005). PFS with levantinib alone was 7.4 months (95% CI 5.6 to 10.20; HR 0.66 [95% CI 0.30 to 1.10]; P = 0.12). In addition, PFS with levantinib alone was significantly prolonged in comparison with everolimus alone (HR 0.61 [95% CI 0.38 to 0.98]; P = 0.048). Grade 3 or 4 toxicity were less frequent in the everolimus only arm and the most common grade 3 or 4 toxicity in the lenvatinib plus everolimus arm was diarrhea. The results of this study show that the combination of lenvatinib plus everolimus is an acceptable second-line option for treatment of patients with advanced or metastatic RCC.55

CASE CONTINUED

The patient is initially started on pazopanib and tolerates the medication well, with partial response to the treatment. However, on restaging scans he is noted to have small bowel perforation. Pazopanib is discontinued until the patient has a full recovery. He is then started on everolimus. Restaging scans done 3 months after starting everolimus demonstrate disease progression.

• What is the appropriate next step in treatment?

PD1 BLOCKADE

Programmed death 1 (PD-1) protein is a T-cell inhibitory receptor with 2 ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2. PD-L1 is expressed on many tumors. Blocking the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1 by anti-PD-1 humanized antibodies potentiates a robust immune response and has been a breakthrough in the field of cancer immunotherapy.79 Previous studies have demonstrated that overexpression of PD-L1 leads to worse outcomes and poor prognosis in patients with RCC.80 Nivolumab, a fully human IgG4 PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, blocks the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2. In a randomized, open-label, phase 3 study comparing nivolumab with everolimus in patients with RCC who had previously undergone treatment with other standard therapies, Motzer and colleagues81 demonstrated a longer overall survival time and fewer adverse effects with nivolumab. In this study, 821 patients with clear-cell RCC were randomly assigned to receive nivolumab (3 mg/kg of body weight IV every 2 weeks) or everolimus (10 mg orally once daily). The median overall survival time with nivolumab was 25 months versus 19.6 months with everolimus (P < 0.0148). Nineteen percent of patients receiving nivolumab experienced grade 3 or 4 toxicities, with fatigue being the most common adverse effect. Grade 3 or 4 toxicities were observed in 37% of patients treated with everolimus, with anemia being the most common. Based on the results of this trial, on November 23, 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved nivolumab to treat patients with metastatic RCC who have received a prior antiangiogenic therapy.

CASE CONCLUSION

Both TKI and mTOR inhibitor therapy fail, and the patient is eligible for third-line therapy. Because of his previous GI perforation, other TKIs are not an option. The patient opts for enrollment in hospice due to declining performance status. For other patients in this situation with a good performance status, nivolumab would be a reasonable option.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

With the approval of nivolumab, multiple treatment options are now available for patients with metastatic or unresectable RCC. Development of other PD-1 inhibitors and immunotherapies as well as multi-targeted TKIs will only serve to expand treatment options for these patients. Given the aggressive course and poor prognosis of non-clear cell renal cell tumors and those with sarcomatoid features, evaluation of systemic and targeted therapies for these subtypes should remain active areas of research and investigation.

- Siegel R, Miller, K, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:5–29.

- Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA. Pathology and genetics. Tumors of the urinary system and male genital organs. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004.

- Chow WH, Gridley G, Fraumeni JF Jr, Jarvholm B. Obesity, hypertension, and the risk of kidney cancer in men. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1305–11.

- Cohen H, McGovern F. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2477–90.

- Yao M, Yoshida M, Kishida T, et al. VHL tumor suppres sor gene alterations associated with good prognosis in sporadic clear-cell renal carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:1569–75.

- Iliopoulos O, Kibel A, Gray S, Kaelin WG Jr. Tumour suppression by the human von Hippel-Lindau gene product. Nat Med 1995;1:822–6

- Chen F, Kishida T, Duh FM, et al. Suppression of growth of renal carcinoma cells by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene. Cancer Res 1995;55:4804–7.

- Iliopoulos O, Levy AP, Jiang C, et al. Negative regulation of hypoxia-inducible genes by the von Hippel Lindau protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93:10595–9.

- Nickerson ML, Warren MB, Toro JR, et al. Mutations in a novel gene lead to kidney tumors, lung wall defects, and benign tumors of the hair follicle in patients with the Bir- Hogg-Dube syndrome. Cancer Cell 2002;2:157–64

- Shuch B, Vorganit S, Ricketts CJ, et al. Defining early-onset kidney cancer: implications for germline and somatic mutation testing and clinical management. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:431–7.

- Bukowski RM. Immunotherapy in renal cell carcinoma. Oncology 1999;13:801–10.

- Mueller-Lisse UG, Mueller-Lisse UL. Imaging of advanced renal cell carcinoma. World J Urol 2010;28: 253–61.

- Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC cancer staging manual, 7th ed. New York: Springer Science and Business Media LLC; 2010.

- O’Malley RL, Godoy G, Kanofsky JA, Taneja SS. The necessity of adrenalectomy at the time of radical nephrectomy: a systematic review. J Urol 2009;181:2009–17.

- McDougal S, Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, et al. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 10th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Saunders; 2012.

- Colombo JR Jr, Haber GP, Kelovsek JE, et al. Seven years after laparoscopic radical nephrectomy: oncologic and renal functional outcomes. Urology 2008:71:1149–54.

- Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Ca 2013;49: 1374–403.

- Weight CJ, Larson BT, Fergany AF, et al. Nephrectomy induced chronic renal insufficiency is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular death and death from any cause in patients with localized cT1b renal masses. J Urol 2010;183:1317–23.

- Van Poppel H, Da Pozzo L, Albrecht W, et al. A prospective, randomized EORTC intergroup phase 3 study comparing the oncologic outcome of elective nephron-sparing surgery and radical nephrectomy for low-stage renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2011;59:543–52.

- Smaldone MC, Fung C, Uzzo RG, Hass NB. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapies in high-risk renal cell carcioma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2011;25:765–91.

- NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Version 3.2016. www.nccn.org. Accessed July 13, 2016

- El Dib R, Touma NJ, Kapoor A. Cryoablation vs radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma: a meta-amalysis of case series studies. BJU Int 2012;110:510–6.

- Theodorescu D. Cancer cryotherapy: evolution and biology. Rev Urol 2004;6 Suppl 4:S9–S19.

- Khiatani V, Dixon RG. Renal ablation update. Sem Intervent Radiol 2014;31:157–66.

- Yu J, Liang P, Yu XL, et al. US-guided percutaneous microwave ablation of renal cell carcinoma: intermediate-term results. Radiol 2012;263:900–8.

- Castle SM, Salas N, Leveillee RJ. Initial experience using microwave ablation therapy for renal tumor treatment: 18- month follow-up. Urology 2011;77:792–7.

- Pech M, Janitzky A, Wendler JJ, et al. Irreversible electroporation of renal cell carcinoma: a first-in-man phase I clinical study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2011;34:132–8.

- Chow WH, Devesa SS, Warren JL, Fraumeni JF Jr. Rising incidence of renal cell cancer in the United States. JAMA 1999;281:1628–31.

- Jayson M, Sanders H. Increased incidence of serendipitously discovered renal cell carcinoma. Urology 1998;51:203–5.

- Pierorazio PM, Johnson MH, Ball MW, et al. Five-year analysis of a multi-institutional prospective clinical trial of delayed intervention and surveillance for small renal masses: the DISSRM registry. Eur Urol 2015;68:408–15.

- Jewett MA, Mattar K, Basiuk J, et al. Active surveillance of small renal masses: progression patterns of early stage kidney cancer. Eur Urol 2011;60:39–44.

- Chawla SN, Crispen PL, Hanlon AL, et al. The natural history of observed enhancing renal masses: meta-analysis and review of the world literature. J Urol 2006;175:425–31.

- Smaldone MC, Kutikov A, Egleston BL, et al. Small renal masses progressing to metastases under active surveillance: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Cancer 2012;118:997–1006.

- Williamson TJ, Pearson JR, Ischia J, et al.Guideline of guidelines: follow-up after nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int 2016;117:555–62.

- Donat S, Diaz M, Bishoff JT, et al. Follow-up for clinically localized renal neoplasms: AUA Guideline. J Urol 2013;190:407–16.

- Janzen NK, Kim HL, Figlin RA, Bell-degrun AS. Surveillance after radical or partial nephrectomy for localized renal cell carcinoma and management of recurrent disease. Urol Clin North Am 2003:30:843–52.

- Gupta K, Miller JD, Li JZ, Russell MW, Charbonneau C. Epidemiologic and socio-economic burden of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): a literature review. Cancer Treat Rev 2008;34:193–205.

- Mekhail T, Abou-Jawde R, Boumerhi G, et al. Validation and extension of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Prognostic Factors Model for Survival in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2005;23: 832–41.

- Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Murphy BA, et al. Interferon-alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:289–96.

- Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bacik J, et al. Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2530–40.

- Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5794–9.

- Leibovich BC, Han KR, Bui MH, et al. Scoring algorithm to predict survival after nephrectomy and immunotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A stratification tool for prospective clinical trials. Cancer 2003;98:2566–77.

- Flanigan RC, Mickisch G, Sylvester R, et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with metastatic renal cancer: a combined analysis. J Urol 2004;171:1071–6.

- Choueiri TK, Xie W, Kollmannsberger C, et al. The impact of cytoreductive nephrectomy on survival of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving vascular endothelial growth factor targeted therapy. J Urol 2011;185:60–6.

- Chapin BF, Delacroix SE Jr, Culp SH, et al. Safety of presurgical targeted therapy in the setting of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2011;60:964–71.

- Hutson TE, Lesovoy V, Al-Shukri S, et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomized open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1287–94.

- Escudier B, Pluzanska A, Koralewski P, et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metatastic renal cell carcinoma: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet 2007;370:2103–11.

- Escudier B, Bellmunt J, Negrier S, et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (AVOREN): final analysis of overall survival. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:2144–50.

- McDermott DF, Cheng SC, Signoretti S, et al. The high-dose aldesleukin “select”trial: a trial to prospectively validate predictive models of response to treatment in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:561–8.

- Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2013;369:722–31.

- Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib for treatment of renal cell carcinoma: final efficacy and safety results of the phase III treatment approaches in renal cell global evaluation trial. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3312–8.

- Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007;356:115–24.

- Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3584–90.

- Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2271–81.

- Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Glen H, et al. Lenvatinib, everolimus and the combination in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomized, phase 2, open label, multicenter trial. Lancet Oncology 2015;16:1473–82.

- Lexi-Comp, Inc. (Lexi-Drugs® ). Lexi-Drugs version 2.3.3. Lexicomp. Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Hudson, OH.

- Choueiri TK, Plantade A, Elson P, et al. Efficacy of sunitinib and sorafenib in metastatic papillary and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:127–31.

- Lee JL, Ahn JH, Lim HY, et al. Multicenter phase II study of sunitinib in patients with non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2108–14.

- Armstrong AJ, Broderick S, Eisen T, et al. Final clinical results of a randomized phase II international trial of everolimus vs. sunitinib in patients with metastatic non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ASPEN). ASCO Meeting Abstracts 2015;33:4507.

- Chowdhury S, Matrana MR, Tsang C, et al. Systemic therapy for metastatic non-clear-cell renal cell carcinoma: recent progress and future directions. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2011;25:853–69.

- Escudier B, Droz JP, Rolland F, et al. Doxorubicin and ifosfamide in patients with metastatic sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: a phase II study of the Genitourinary Group of the French Federation of Cancer Centers. J Urol 2002; 168–71

- Nanus DM, Garino A, Milowsky MI, et al. Active chemotherapy for sarcomatoid and rapidly progressing renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 2004;101:1545–51.

- Michaelson MD, McKay RR, Werner L, et al. Phase 2 trial of sunitinib and gemcitabine in patients with sarcomatoid and/or poor-risk metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 2015;121:3435–43.

- McDermott DF, Cheng SC, Signoretti S, et al. The high-dose aldesleukin “select”trial: a trial to prospectively validate predictive models of response to treatment in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:561–8

- Cho DC, Puzanov I, Regan MM, et al. Retrospective analysis of the safety and efficacy of interleukin-2 after prior VEGF-targeted therapy in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Immunother 2009;32:181–5.

- Pyrhönen S, Salminen E, Ruutu M, et al. Prospective randomized trial of interferon alfa-2a plus vinblastine versus vinblastine alone in patients with advanced renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2859–67.

- Interferon-alpha and survival in metastatic renal carcinoma: early results of a randomised controlled trial. Medical Research Council Renal Cancer Collaborators. Lancet 1999;353:14–7.

- Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;349:427–34.

- Atkinson BJ, Kalra S, Wang X, et al. Clinical outcomes for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with alternative sunitinib schedules. J Urol 2014;191:611–8.

- Kollmannsberger C, Bjarnason G, Burnett P, et al. Sunitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: recommendations for management of noncardiovascular toxicities. Oncologist 2011;16:543–53.

- Najjar YG, Mittal K, Elson P, et al. A 2 weeks on and 1 week off schedule of sunitinib is associated with decreased toxicity in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 2014;50:1084–9.

- Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1061–8.

- Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007;356:125–34

- Rini BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011;378:1931–9.

- Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T, et al. Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1814–23.

- Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T, et al. Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma (METEOR) final results from a randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncology 2016;17:917–27.

- Bjornsti MA, Houghton PJ. The TOR pathway: a target for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2004;4:335–48.

- Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet 2008;372:449–56.

- Brahmer J, Tykodi S, Chow L, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2455–65.

- Thomson RH, Kuntz SM, Leibovich BC, et al. Tumor B7-H1 is associated with poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma patients with long-term follow up. Cancer Res 2006;66: 3381–5.

- Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1803–13.

INTRODUCTION

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common malignancy arising in the kidney, comprising 90% of all renal tumors.1 Approximately 55,000 new RCC cases are diagnosed each year.2 Patients with RCC are often asymptomatic, and most cases are discovered as incidental findings on abdominal imaging performed during evaluation of nonrenal complaints. Limited-stage RCC that is found early can be cured surgically, with estimated 5-year survival rates approaching 90%; however, long-term survival for metastatic disease is poor, with rates ranging from 0% to 20%.2 Advanced RCC is resistant to conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and outcomes for patients with metastatic or unresectable RCC remain poor. However, the recent development of new therapeutic modalities that target tumor molecular pathways has expanded the treatment options for these patients and changed the management of RCC.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLASSIFICATION

Median age at diagnosis in the United States is 64 years. Men have a higher incidence of RCC than women, with the highest incidence seen in American Indian and Alaska Native men (30.1 per 100,000 population). Genetic syndromes account for 2% to 4% of all RCCs.2 Risk factors for RCC include smoking, hypertension, obesity, and acquired cystic kidney disease that is associated with end-stage renal failure.3 Longer duration of tobacco use is associated with a more aggressive course.

The 2004 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of renal tumors summarizes the previous classification systems (including the Heidelberg and Mainz classification systems) to describe different categories of RCC based on histologic and molecular genetics characteristics.2 Using the WHO classification criteria, RCC comprises 90% of all renal tumors, with clear cell being the most common type (80%).2 Other types of renal tumors include papillary, chromophobe, oncocytoma, and collecting-duct or Bellini duct tumors. Approximately 3% to 5% of tumors are unclassified. Oncocytomas are generally considered benign, and chromophobe tumors typically have an indolent course and rarely metastasize. Sarcomatoid differentiation can be seen in any histologic type and is associated with a worse prognosis. While different types of tumors may be seen in the kidney (such as transitional cell or lymphomas), the focus of this review is the primary malignancies of the renal parenchyma.

FAMILIAL SYNDROMES

Several genetic syndromes have been identified by studying families with inherited RCC. Among these, von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene mutation is the most commonly found inherited genetic defect. Table 1 summarizes the incidence of gene mutations and the corresponding histologic appearance of the most common sporadic and hereditary RCCs.4

VHL disease is an autosomal dominant familial syndrome. Patients with this mutation are at higher risk for developing RCC (clear cell histology), retinal angiomas, pheochromocytomas, as well as hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system (CNS).4 Of all the genetic mutations seen in RCC, the somatic mutation in the VHL tumor-suppressor gene is by far the most common.5 VHL targets hypoxia–inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-α) for ubiquitination and subsequent degradation, which has been shown to suppress the growth of clear-cell RCC in mouse models.6–8 HIF expression under hypoxic conditions leads to activation of a number of genes important in blood vessel development, cell proliferation, and glucose metabolism, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), erythropoietin, platelet-derived growth factor beta (PDGF-β), transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-α), and glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1). Mutation in the VHL gene prevents degradation of the HIF-α protein, thereby leading to increased expression of these downstream proteins, including MET and Axl. The upregulation of these angiogenic factors is thought to be the underlying process for increased vascularity of CNS hemangioblastomas and clear-cell renal tumors in VHL disease.4–8

Other less common genetic syndromes seen in hereditary RCC include hereditary papillary RCC, hereditary leiomyomatosis, and Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome.9 In hereditary papillary RCC, the MET gene is mutated. BHD syndrome is a rare, autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by hair follicle hamartomas of the face and neck. About 15% of patients have multiple renal tumors, the majority of which are of the chromophobe or mixed chromophobe-oncocytoma histology. The BHD gene encodes the protein folliculin, which is thought to be a tumor-suppressor gene.

DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING

CASE PRESENTATION

A 74-year-old man who works as an airplane mechanic repairman presents to the emergency department with sudden worsening of chronic right upper arm and shoulder pain after lifting a jug of orange juice. He does not have a significant past medical history and initially thought that his pain was due to a work-related injury. Upon initial evaluation in the emergency department he is found to have a fracture of his right humerus. Given that the fracture appears to be pathologic, further work-up is recommended.

• What are common clinical presentations of RCC?

Most patients are asymptomatic until the disease becomes advanced. The classic triad of flank pain, hematuria, and palpable abdominal mass is seen in approximately 10% of patients with RCC, partly because of earlier detection of renal masses by imaging performed for other purposes.10 Less frequently, patients present with signs or symptoms of metastatic disease such as bone pain or fracture (as seen in the case patient), painful adenopathy, and pulmonary symptoms related to mediastinal masses. Fever, weight loss, anemia, and/or varicocele often occur in young patients (≤ 46 years) and may indicate the presence of a hereditary form of the disease. Patients may present with paraneoplastic syndromes seen as abnormalities on routine blood work. These can include polycythemia or elevated liver function tests (LFTs) without the presence of liver metastases (known as Stauffer syndrome), which can be seen in localized renal tumors. Nearly half (45%) of patients present with localized disease, 25% present with locally advanced disease, and 30% present with metastatic disease.11 Bone is the second most common site of distant metastatic spread (following lung) in patients with advanced RCC.

• What is the approach to initial evaluation for a patient with suspected RCC?

Initial evaluation consists of a physical exam, laboratory tests including complete blood count (CBC) and comprehensive metabolic panel (calcium, serum creatinine, LFTs, lactate dehydrogenase [LDH], and urinalysis), and imaging. Imaging studies include computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and chest imaging. A chest radiograph may be obtained, although a chest CT is more sensitive for the presence of pulmonary metastases. MRI can be used in patients with renal dysfunction to evaluate the renal vein and inferior vena cava (IVC) for thrombus or to determine the presence of local invasion.12 Although bone and brain are common sites for metastases, routine imaging is not indicated unless the patient is symptomatic. The value of positron emission tomography in RCC remains undetermined at this time.

Staging is done according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging classification for RCC; the Figure summarizes the staging and 5-year survival data based on this classification scheme.4,13

J Med 2005;353:2477–90.)

LIMITED-STAGE DISEASE

• What are the therapeutic options for limited-stage disease?

For patients with nondistant metastases, or limited-stage disease, surgical intervention with curative intent is considered. Convention suggests considering definitive surgery for patients with stage I and II disease, select patients with stage III disease with pathologically enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes, patients with IVC and/or cardiac atrium involvement of tumor thrombus, and patients with direct extension of the renal tumor into the ipsilateral adrenal gland if there is no evidence of distant disease. While there may be a role for aggressive surgical intervention in patients with distant metastatic disease, this topic will not be covered in this review.

SURGICAL INTERVENTION

Once patients are determined to be appropriate candidates for surgical removal of a renal tumor, the urologist will perform either a radical nephrectomy or a nephron-sparing nephrectomy, also called a partial nephrectomy. The urologist will evaluate the patient based on his or her body habitus, the location of the tumor, whether multiple tumors in one kidney or bilateral tumors are present, whether the patient has a solitary kidney or otherwise impaired kidney function, and whether the patient has a history of a hereditary syndrome involving kidney cancer as this affects the risk of future kidney tumors.

A radical nephrectomy is surgically preferred in the presence of the following factors: tumor larger than 7 cm in diameter, a more centrally located tumor, suspicion of lymph node involvement, tumor involvement with renal vein or IVC, and/or direct extension of the tumor into the ipsilateral adrenal gland. Nephrectomy involves ligation of the vascular supply (renal artery and vein) followed by removal of the kidney and surrounding Gerota’s fascia. The ipsilateral adrenal gland is removed if there is a high-risk for or presence of invasion of the adrenal gland. Removal of the adrenal gland is not standard since the literature demonstrates there is less than a 10% chance of solitary, ipsilateral adrenal gland involvement of tumor at the time of nephrectomy in the absence of high-risk features, and a recent systematic review suggests that the chance may be as low as 1.8%.14 Preoperative factors that correlated with adrenal involvement included upper pole kidney location, renal vein thrombosis, higher T stage (T3a and greater), multifocal tumors, and evidence for distant metastases or lymph node involvement. Lymphadenectomy previously had been included in radical nephrectomy but now is performed selectively. Radical nephrectomy may be performed as

either an open or laparoscopic procedure, the latter of which may be performed robotically.15 Oncologic outcomes appear to be comparable between the 2 approaches, with equivalent 5-year cancer-specific survival (91% with laparoscopic versus 93% with open approach) and recurrence-free survival (91% with laparoscopic versus 93% with open approach).16 The approach ultimately is selected based on provider- and patient-specific input, though in all cases the goal is to remove the specimen intact.16,17

Conversely, a nephron-sparing approach is preferred for tumors less than 7 cm in diameter, for patients with a solitary kidney or impaired renal function, for patients with multiple small ipsilateral tumors or with bilateral tumors, or for radical nephrectomy candidates with comorbidities for whom a limited intervention is deemed to be a lower-risk procedure. A nephron-sparing procedure may also be performed open or laparoscopically. In nephron-sparing procedures, the tumor is removed along with a small margin of normal parenchyma.15

In summary, the goal of surgical intervention is curative intent with removal of the tumor while maintaining as much residual renal function as possible to limit long-term morbidity of chronic kidney disease and associated cardiovascular events.18 Oncologic outcomes for radical nephrectomy and partial nephrectomy are similar. In one study, overall survival was slightly lower in the partial nephrectomy cohort, but only a small number of the deaths were due to RCC.19

ADJUVANT THERAPY

Adjuvant systemic therapy currently has no role following nephrectomy for RCC because no systemic therapy has been able to reduce the likelihood of relapse. Randomized trials of cytokine therapy (eg, interferon, interleukin 2) or tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; eg, sorafenib, sunitinib) with observation alone in patients with locally advanced completely resected RCC have shown no delay in time to relapse or improvement of survival with adjuvant therapy.20 Similarly, adjuvant radiation therapy has not shown benefit even in patients with nodal involvement or incomplete resection.21 Therefore, observation remains the standard of care after nephrectomy.

RENAL TUMOR ABLATION

For patients who are deemed not to be surgical candidates due to age, comorbidities, or patient preference and who have tumors less than 4 cm in size (stage I tumors), ablative techniques may be considered. The 2 most well-studied and effective techniques at present are cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Microwave ablation may be an option in some facilities, but the data in RCC are limited. An emerging ablative technique under investigation is irreversible electroporation. At present, the long-term efficacy of all ablative techniques is unknown.

Patient selection is undertaken by urologists and interventional radiologists who evaluate the patient with ultrasound, CT, and/or MRI to determine the location and size of the tumor and the presence or absence of metastatic disease. A pretreatment biopsy is recommended to document the histology of the lesion to confirm a malignancy and to guide future treatment for recurrent or metastatic disease. Contraindications to the procedure include the presence of metastatic disease, a life expectancy of less than 1 year, general medical instability, or uncorrectable coagulopathy due to increased risk of bleeding complications. Tumors in close proximity to the renal hilum or collecting system are a contraindication to the procedure because of the risk for hemorrhage or damage to the collecting system. The location of the tumor in relation to the vasculature is also important to maximize efficacy because the vasculature acts as a “heat sink,” causing dissipation of the thermal energy. Occasionally, stenting of the proximal ureter due to upper tumor location is necessary to prevent thermal injury that could lead to urine leaks.

Selection of the modality to be used primarily depends on operator comfort, which translates to good patient outcomes, such as better cancer control and fewer complications. Cryoablation and RFA have both demonstrated good clinical efficacy and cancer control of 89% and 90%, respectively, with comparable complication rates.22 There have been no studies performed directly comparing the modalities.

Cryoablation

Cryoablation is performed through the insertion of a probe into the tumor, which may be done through a surgical or percutaneous approach. Once the probe is in place, a high- pressure gas (argon, nitrogen) is passed through the probe and upon entering a low pressure region the gas cools. The gas is able to cool to temperatures as low as –185°C. The tissue is then rewarmed through the use of helium, which conversely warms when entering a low pressure area. The process of freezing followed by rewarming subsequently causes cell death/tissue destruction through direct cell injury from cellular dehydration and vascular injury. Clinically, 2 freeze-thaw cycles are used to treat a tumor.23,24

RFA

Radiofrequency ablation, or RFA, targets tumors via an electrode placed within the mass that produces intense frictional heat from medium-frequency alternating current (approximately 500 kHz) produced by a connected generator that is grounded on the patient. The thermal energy created causes coagulative necrosis. Due to the reliance on heat for tumor destruction, central lesions are less amenable to this approach because of the “heat sink” effect from the hilum.24

Microwave Ablation

Microwave ablation, like RFA, relies on the generation of frictional heat to cause cell death by coagulative necrosis. In this case, the friction is created through the activation of water molecules; because of the different thermal kinetics involved with microwave ablation, the “heat sink” effect is minimized when treatment is employed near large vessels, in comparison to RFA.24 The data on this mechanism of ablation are still maturing, with varied outcomes thus far. One study demonstrated outcomes comparable to RFA and cryoablation, with cancer-specific survival of 97.8% at 3 years.25 However, a study by Castle and colleagues26 demonstrated higher recurrence rates. The overarching impediment to widespread adoption of microwave ablation is inconclusive data gleaned from studies with small numbers of patients with limited follow up. The role of this modality will need to be revisited.

Irreversible Electroporation

Irreversible electroporation (IRE) is under investigation. IRE is a non-thermal ablative technique that employs rapid electrical pulses to create pores in cell membranes, leading to cell death. The postulated benefits of IRE include the lack of an effect from “heat sinks” and less collateral damage to the surrounding tissues, when compared with the thermal modalities. In a human phase 1 study of patients undergoing IRE prior to immediate surgical resection, the procedure appeared feasible and safe.27 Significant concerns for this method of ablation possibly inducing cardiac arrhythmias, and the resultant need for sedation with neuromuscular blockade and associated electrocardiography monitoring, may impede its implementation in nonresearch settings.24

ACTIVE SURVEILLANCE

Due to the more frequent use of imaging for various indications, there has been an increase in the discovery of small renal masses (SRM); 85% of RCC that present in an asymptomatic or incidental manner are tumors under 4 cm in diameter.28,29 The role of active surveillance is evolving, but is primarily suggested for patients who are not candidates for more aggressive intervention based on comorbidities. A recent prospective, nonrandomized analysis of data from the Delayed Intervention and Surveillance for Small Renal Masses (DISSRM) registry evaluated outcomes for patients with SRM looking at primary intervention compared with active surveillance.30 The primary intervention selected was at the discretion of the provider; treatments included partial nephrectomy, RFA, and cryoablation, and active surveillance patients were followed with imaging every 6 months. Progression of SRM, with recommendation for delayed intervention, was defined as a growth rate of mass greater than 0.5 cm/year, size greater than 4 cm, or hematuria. Thirty-six of 158 patients on active surveillance met criteria for progression; 21 underwent delayed intervention. Of note, even the patients who progressed but did not undergo delayed intervention did not develop metastatic disease during the follow-up interval. With a median follow-up of 2 years, cancer-specific survival was noted to be 99% and 100% at 5 years for primary intervention and active surveillance, respectively. Overall survival at 2 years for primary intervention was 98% and 96% for active surveillance; at 5 years, the survival rates were 92% and 75% (P = 0.06). Of note, 2 patients in the primary intervention arm died of RCC, while none in the active surveillance arm died. As would be expected, active surveillance patients were older, had a worse performance status, and had more comorbidities. Interestingly, 40% of patients enrolled selected active surveillance as their preferred management for SRM. The DISSRM results were consistent with data from the Renal Cell Consortium of Canada and other retrospective reviews.31–33

• What is the approach to follow-up after treatment of localized RCC?

After a patient undergoes treatment for a localized RCC, the goal is to optimize oncologic outcomes, monitor for treatment sequelae, such as renal failure, and focus on survivorship. At this time, there is no consensus in the literature or across published national and international guidelines with regards to the appropriate schedule for surveillance to achieve these goals. In principle, the greatest risk for recurrence occurs within the first 3 years, so many guidelines focus on this timeframe. Likewise, the route of spread tends to be hematogenous, so patients present with pulmonary, bone, and brain metastases, in addition to local recurrence within the renal bed. Symptomatic recurrences often are seen

with bone and brain metastases, and thus bone scans and brain imaging are not listed as part of routine surveillance protocols in asymptomatic patients. Although there is inconclusive evidence that surveillance protocols improve outcomes in RCC, many professional associations have outlined recommendations based on expert opinion.34 The American Urological Association released guidelines in 2013 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) released their most recent set of guidelines in 2016.21,35 These guidelines use TNM staging to risk-stratify patients and recommend follow-up.

METASTATIC DISEASE

CASE CONTINUED