User login

Enhancing communication between oncology care providers and patient caregivers during hospice

Improving the delivery of end-of-life care for patients with advanced cancer has become a priority in the United States.1,2 Quality metrics identifying the components of high-quality end-of-life care have focused on improved symptom management, decreased use of chemotherapy at the end of life, fewer hospitalizations, and increased use of hospice care. Patients and caregivers also consider good communication with the medical team to be a critical component of end-of-life care.3-5 Interventions to improve the quality of end-of-life care are needed.

Caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who receive hospice services report better quality of care and death than those receiving end-of-life care in other settings.6-9 However, the transition for patients from active cancer therapy delivered by their oncologists to end-of-life care delivered by a hospice care team can be abrupt. Patients and their caregivers often feel abandoned by oncology clinicians because of the lack of continuity of care and poor communication.10-13 Caregivers who note continued involvement and communication with their oncology clinicians experience a lower caregiving burden, report higher satisfaction with care, and recount a higher quality of death for their loved one.14-16 Therefore, interventions that prevent abrupt transitions in care from oncology to hospice by ensuring continued communication with oncology clinicians are needed to improve the quality of end-of-life care.17 Recent findings have shown that providing concurrent oncology and palliative care is not only feasible but beneficial for patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers.18-24 However, there is no standard of care for the involvement of oncology clinicians in the care of patients receiving hospice services and their families.

Although interventions may be needed, it could be challenging to deliver them given the multiple demands of caregiving during hospice and the lack of regular contact in clinic. We sought to assess the feasibility of an intervention, Ensuring Communication in Hospice by Oncology (ECHO), to facilitate communication between oncology clinicians and caregivers of patients who enroll in hospice. We also explored caregiver-reported outcomes during hospice care, including satisfaction with care, attitudes toward caregiving, stress, decision regret, and perception of the quality of patients’ end-of-life care.

Methods

Study design

During March 2014-June 2015, caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who enrolled in home hospice services were eligible to participate in the study at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston. The Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved all methods and materials. The study opened with an enrollment goal of 30 participating caregivers. However, due to staff transitions, we closed the study early in June 2015 after 25 caregivers enrolled.

Participants

Caregivers of patients receiving care at the cancer center's thoracic, head and neck, sarcoma, melanoma, and gynecological disease centers were eligible within 10 days after a patient’s enrollment in hospice. Five disease sites were selected to participate in the intervention. We defined caregivers as relatives or friends serving as the primary caregiver of the patient at home during hospice care. Other caregiver eligibility criteria included the ability to read and respond to questions in English or with a translator, access to a telephone and/or computer to communicate with oncology clinicians, and willingness to complete questionnaires. Caregivers were ineligible if the patient was participating in an ongoing palliative care trial.

To identify eligible caregivers, case managers from both the inpatient and outpatient settings, as well as the nurses based in participating disease centers, notified the research team of all patients referred to hospice. If the patient had received oncology care in one of our participating disease centers, the research team contacted their oncology clinician/s (physicians, nurse practitioners [NP], registered nurses [RN], and/or physician assistants [PA]) to inquire if the patient had an involved caregiver and to obtain permission to offer study participation. If the oncology clinician/s did not grant permission, we documented the reason. Otherwise, with permission, research staff contacted the caregiver by telephone to offer study participation and obtain verbal consent. We then sent participating caregivers a copy of the informed consent by mail or e-mail.

Intervention

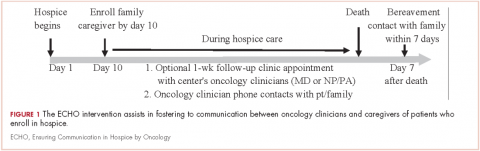

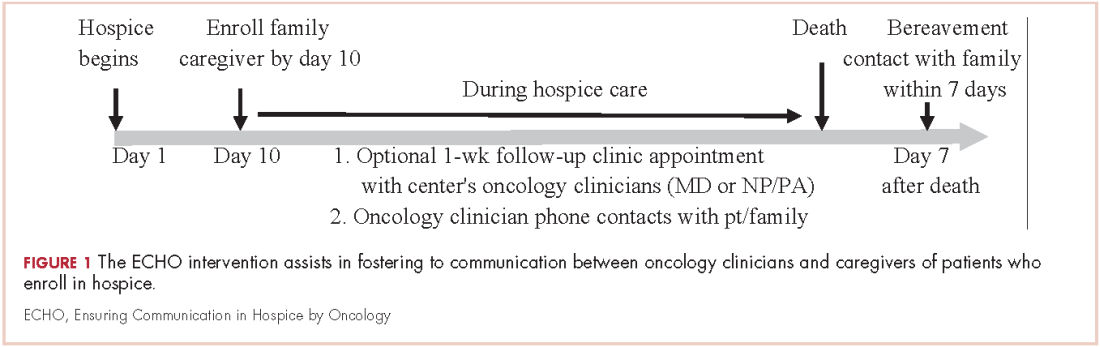

The ECHO intervention consisted of: supportive phone calls from an oncology clinician to the caregiver; an optional clinic visit with the oncology clinician for the patient to address clinical questions or concerns that was offered during the initial telephone consent; a bereavement call to the participating caregiver (Figure 1). Initially, we designed the intervention to have phone calls occurring twice weekly until the patient died. However, 3 months after starting the study, we received feedback from oncology clinicians and caregivers that calls were too frequent, so we amended the protocol to include phone calls twice weekly for the first 2 weeks of the study and then weekly thereafter. Seven months into the study, we again decreased the number of phone calls to weekly for the first 4 weeks, every other week for 4 weeks, and then monthly until patient death. We informed caregivers of changes by e-mail.

Before we started the study, we conducted training sessions with oncology clinicians from the participating disease centers to review study procedures and expectations of the phone calls. Supportive phone calls during hospice were not a part of standard practice prior to the study. The RN, NP or PA, and/or physician who had an established relationship with the patient and caregiver completed the phone calls. They decided based on their respective relationships with the patients and their workloads who would call each week, though the majority of calls were conducted by the RN or NP. All the clinicians had experience comanaging patients with hospice agencies, and our general practice is for the oncology physician to serve as the hospice attending of record. The calls were intended to offer support and reassurance to caregivers. We did not script the calls so that clinicians could tailor their content to the individual needs of the caregiver, as informed by their established relationship. The calls could include the patient if he/she was able to and interested in speaking to the clinician. There was no standardized communication with hospice as part of the intervention. If a caregiver raised concerns about symptom management during a call, the clinician would advise the caregiver to contact the hospice team directly or the clinician would call the hospice to discuss, depending on the clinical scenario and the clinician’s judgment. Research staff reminded oncology clinicians to call caregivers on the scheduled date and to document the discussion in the electronic medical record. The hospice phone number was included in the e-mail. If the call was not documented, research staff sent a reminder e-mail to the oncology clinicians 24 hours after the call was due.

Caregiver-reported measures

Caregivers completed a demographic questionnaire at baseline in which they reported their age, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, employment status, and relationship to the patient. We collected information about patient characteristics from the electronic medical record, including age, gender, and cancer type. In addition, we administered validated, self-report measures (see below). We limited the number of measures to decrease caregiver burden:

The baseline questionnaire included the FACQ-PC, the FAMCARE scale, the PSS, and the Decision Regret Scale. Initially, the study involved weekly questionnaires after baseline that included the FACQ-PC, the FAMCARE scale, and the PSS. However, after 3 months of study enrollment, we received feedback that the questionnaires were too frequent, so we amended the protocol and changed the frequency to weekly for 2 weeks, then monthly thereafter until the patient died.

Caregiver exit interview

Exit interviews included the toolkit interview, the Quality of End-of-Life Care scale, and the Decision Regret Scale. Caregivers also reported patients’ place and date of death. After the first 6 caregivers enrolled, we amended the exit interview to include open-ended feedback from caregivers. Specifically, we evaluated caregivers’ perceptions of the ECHO intervention by asking them about their perception of and satisfaction with the content and frequency of the oncology clinicians’ phone calls, whether they had an in-person visit with their oncology clinicians after the start of hospice care, whether the clinician/s contacted them after the patient died, and whether there were ways in which the clinician/s could help in the future.

Data collection and storage

Caregivers were given the option of completing study measures by telephone or e-mail so that they could complete them on a computer when it was convenient for them. Caregivers received a link to Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a web-based, HIPAA-compliant application that allows participants to answer questionnaires online. The exit interviews were completed by phone, and research staff entered the data into the REDCap database. In addition, with we obtained caregiver permission to audiorecord the exit interviews, which were then transcribed and de-identified.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome for the study was feasibility, which we defined as >70% of the caregivers receiving >50% of the phone calls from an oncology clinician, and >70% of the caregivers completing >50% of the questionnaires. All time points for the questionnaires and the exit interview counted toward feasibility. Exploratory endpoints included caregiver-reported satisfaction, stress, quality of end-of-life care, and decision-making regret.

Using STATA (v9.3; StataCorp, College Station, Texas) for all statistical analyses, we summarized participants’ characteristics and outcomes as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and mean standard deviation for continuous variables. We used the repeated-measures t test to assess changes in caregiver outcomes over time. We used the Fisher exact test to compare clinically meaningful threshold scores of perceived stress between men and women.

We examined caregivers’ open-ended feedback using descriptive analyses to summarize comments about the intervention and to inform possible refinements for a future study.

Results

Baseline characteristics

During March 2014-June 2015, we enrolled caregivers of patients with advanced cancer from 5 participating disease centers: thoracic, head and neck, sarcoma, melanoma, and gynecological malignancy. We screened 123 patients to determine the eligibility of their caregivers (Figure 2). Of 38 eligible caregivers, 7 could not be reached, 6 declined participation, and 25 enrolled in the study (81% enrollment rate). Of the 25 caregivers who enrolled, 3 withdrew – 2 because the patients they were caring for died before the intervention began, and 1 who withdrew from the study because the family wanted less contact with the oncology clinician/s. Thus, we had data for 22 caregivers for our feasibility evaluation. One caregiver stopped study assessments after 3 months because the patient dis-enrolled from hospice. Median time from the patients’ hospice enrollment to caregiver study enrollment was 3 days (range, 1-9). Median time from study enrollment to patient death was 36 days (range, 2-135). Patients were receiving care from 10 different hospice agencies.

All of the patients had metastatic cancer, and 64% were women (Table 1).

Most of the caregivers were white (n = 18, 90%) and women (n = 12, 55%). The majority were the patient’s spouse (n = 12, 60%) or child (n = 6, 30%), and they lived with the patient (n = 16, 80%). Many of the caregivers had other responsibilities in addition to caring for the patients, including part- or full-time work (n = 10, 50%) or caring for others in addition to the patient (n = 10, 50%).

Feasibility

Over the study period, oncology clinicians completed 164 of 180 possible phone calls (91%). All 22 caregivers received >50% of the phone calls. Caregivers completed 78 of 99 possible questionnaires (79%), and 16 of 22 completed >50% of the questionnaires (73%). None of the caregivers/patients wanted to schedule the optional visit with an oncology clinician that was offered as part of the intervention; however, 5 patients had a clinic visit after hospice enrollment. In addition, 2 oncologists visited a patient and caregiver at home. All caregivers received bereavement contact from the oncology team.

Caregiver-reported outcomes

In all, 20 of the 22 enrolled caregivers completed baseline measures (Table 2), and they all chose to complete questionnaires by e-mail. Caregivers’ attitudes toward caregiving and satisfaction with hospice services were overall positive. They reported high mean scores on the 2 domains on the FACQ-PC of positive caregiver appraisal (mean, 4.25; SD, 0.52) and family well-being (mean, 4.09; SD, 0.45). The majority of caregivers (75%-95%) reported they were satisfied or very satisfied with various dimensions of hospice care based on the FAMCARE questionnaire.

Overall, caregivers reported moderate levels of stress (mean, 13.55; SD, 6.08) based on the PSS scores. Of the 20 caregivers who completed the baseline measures, 8 had clinically meaningful stress, and stress was numerically higher in female caregivers than in their male counterparts, but it did not reach statistical significance (55% vs 22%, P = .197). Finally, at baseline, caregivers indicated relatively low levels of decisional regret about enrolling in hospice, although there was considerable variation (mean, 10.25; SD, 14.37).

We conducted exit interviews with 15 caregivers because we were not able to reach 6 of the original 21 (Table 2). Caregivers rated hospice services highly for communication, symptom control, emotional support, and overall care. They also rated quality of death highly (mean, 8.46; SD 1.13). Regret was lower at the end of the study, but this did not reach statistical significance (baseline mean 9.29; end of study mean 3.57; P = .161).

In the recorded exit interviews, all of the caregivers responded they were satisfied with the phone calls. Two caregivers commented that they would have preferred the calls were more scheduled or at more suitable times. Overall, they described the phone calls as excellent, supportive, responsive, comfortable, and appreciated. All caregivers reported contact with the oncology team after the patient died, but one caregiver was disappointed she was only contacted by the nurse practitioner and not the oncologist. Participants did not feel as if there were other ways that the oncology team could have been helpful for them while their loved one was in hospice.

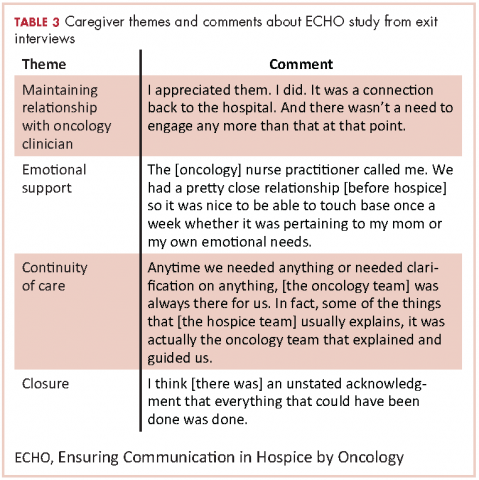

Table 3 highlights other representative comments from the exit interviews.

Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first study to assess the feasibility of an intervention to facilitate communication between oncology clinicians and caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who are receiving hospice care. Despite the challenges of oncology clinicians delivering an intervention to caregivers during hospice, we found this intervention was feasible and acceptable. Although the transition to hospice can be stressful, caregivers reported high satisfaction with hospice care and the quality of the patient’s death. In exit interviews, they also reported high satisfaction with the intervention and appreciation for maintaining their relationship with the oncology team. It is worth noting that no caregiver requested the optional clinic visit after hospice enrollment, and most caregivers were not seen again in clinic after hospice enrollment.

These results suggest that a simple, telephone-based intervention of scheduled calls from the oncology team at prompted intervals is not only feasible, but may also help foster continuity between the patient and caregiver and the oncology team. We received feedback from both oncology clinicians and caregivers that the initial call frequency was too often, suggesting that communication may not need to be very frequent to maintain continuity and provide support. This also suggests that if the calls are too frequent, they may be more intrusive than helpful for both oncologists and caregivers. Alternatively, caregiver suggestion for fewer phone calls may indicate that concerns about abandonment are less prevalent than existing literature has suggested.

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations. The sample size was small as this was a feasibility study conducted at a single tertiary care hospital, and the population was 90% white and 95% college educated, which may limit the generalizability of our results. In addition, the median length of stay in hospice for patients on this study was 36 days, which is long compared with national averages,32,33 and thus the outcomes may not represent the experience of a more heterogeneous population. The longer length of stay in hospice may have contributed to caregivers’ high satisfaction with the quality of end-of-life care.

Oncologists did not grant permission for the study team to approach all eligible caregivers, which may have introduced selection bias. We were also not able to reach 6 participants for exit interviews. People less satisfied with the intervention or with hospice may be more likely to have missing data, which could introduce bias into the satisfaction ratings. Furthermore, we did not explore the oncology clinicians’ perspective of the intervention or assess the time commitment of the calls. Oncology clinicians have many competing responsibilities and have variable experience and comfort with hospice care. Therefore, future studies should explore the perspective of oncology clinicians in regard to the intervention.

Finally, we did not require communication with the hospice agency as part of the intervention as there were ten different hospices involved. Thus, we do not know how the intervention impacted the hospice team’s care of the patient. However, based upon the success of this pilot study, future larger studies should explore the impact of the intervention from the perspective of the hospice care team and include oncology clinician communication with the hospice agency.

Conclusion

These findings demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability of an intervention to enhance communication between oncology clinicians and caregivers of patients with advanced cancer receiving hospice care. Importantly, the high caregiver satisfaction with the intervention in this study suggests that maintaining communication with the primary oncology team during hospice care may be an important component of high quality end-of-life care, though the desire for decreased calls suggests that this communication need not be frequent to maintain the continuity. A randomized study with a larger and more diverse patient/caregiver sample would allow us to explore the impact of the intervention on caregiver feelings of abandonment by the oncology team and short- and long-term caregiver outcomes, as well as to understand the perspective of the oncology and hospice clinicians involved.

1. Institute of Medicine. 2015. Dying in america: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18748.

2. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):96-112.

3. Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Shannon SE, Carline JD, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Communicating with dying patients within the spectrum of medical care from terminal diagnosis to death. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(6):868-874.

4. Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(1):81-93.

5. Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, Christakis NA, McIntyre LM, Tulsky JA. In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(10):825-832.

6. Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291(1):88-93.

7. Kumar P, Wright AA, Hatfield LA, Temel JS, Keating NL. Family perspectives on hospice care experiences of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(4):432-439.

8. Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA. 2016;315(3):284-292.

9. Duggan KT, Hildebrand Duffus S, D’Agostino RB Jr, Petty WJ, Streer NP, Stephenson RC. The impact of hospice services in the care of patients with advanced stage nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(1):29-34.

10. Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Understanding physicians’ skills at providing end-of-life care perspectives of patients, families, and health care workers. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(1):41-49.

11. Back AL, Young JP, McCown E, et al. Abandonment at the end of life from patient, caregiver, nurse, and physician perspectives: loss of continuity and lack of closure. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):474-479.

12. Vig EK, Starks H, Taylor JS, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Why don’t patients enroll in hospice? Can we do anything about it? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(10):1009-1019.

13. Waldrop DP, Meeker MA, Kerr C, Skretny J, Tangeman J, Milch R. The nature and timing of family-provider communication in late-stage cancer: a qualitative study of caregivers’ experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43(2):182-194.

14. Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J, Emanuel LL. Understanding economic and other burdens of terminal illness: the experience of patients and their caregivers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(6):451-459.

15. Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Norris K, Asp C, Byock I. A measure of the quality of dying and death. Initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(1):17-31.

16. Fleming DA, Sheppard VB, Mangan PA, et al. Caregiving at the end of life: Perceptions of health care quality and quality of life among patients and caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(5):407-420.

17. McMillan SC. Interventions to facilitate family caregiving at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(Suppl 1):S132-S139.

18. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741-749.

19. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742.

20. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721-1730.

21. Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Dall’Agata M, et al. Systematic versus on-demand early palliative care: a randomised clinical trial assessing quality of care and treatment aggressiveness near the end of life. Eur J Cancer. 2016;69:110-118.

22. El-Jawahri A ea. Early integrated palliative care to improve family caregivers (FC) outcomes for patients with gastrointestinal and lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl; abstr 10131).

23. Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and gi cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):834-841.

24. El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H, et al. Effect of inpatient palliative care on quality of life 2 weeks after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2094-2103.

25. Cooper B, Kinsella GJ, Picton C. Development and initial validation of a family appraisal of caregiving questionnaire for palliative care. Psychooncology. 2006;15(7):613-622.

26. Kristjanson LJ. Validity and reliability testing of the FAMCARE Scale: measuring family satisfaction with advanced cancer care. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(5):693-701.

27. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385-396.

28. Keir ST, Guill AB, Carter KE, Boole LC, Gonzales L, Friedman HS. Differential levels of stress in caregivers of brain tumor patients--observations from a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(12):1258-1261.

29. Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ, et al. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making. 2003;23(4):281-292.

30. Teno JM, Clarridge B, Casey V, Edgman-Levitan S, Fowler J. Validation of toolkit after-death bereaved family member interview. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22(3):752-758.

31. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665-1673.

32. Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(2):315-321.

33. Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, Dominici F, Block S, Cutler DM. Association between the Medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA. 2014;312(18):1888-1896.

Improving the delivery of end-of-life care for patients with advanced cancer has become a priority in the United States.1,2 Quality metrics identifying the components of high-quality end-of-life care have focused on improved symptom management, decreased use of chemotherapy at the end of life, fewer hospitalizations, and increased use of hospice care. Patients and caregivers also consider good communication with the medical team to be a critical component of end-of-life care.3-5 Interventions to improve the quality of end-of-life care are needed.

Caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who receive hospice services report better quality of care and death than those receiving end-of-life care in other settings.6-9 However, the transition for patients from active cancer therapy delivered by their oncologists to end-of-life care delivered by a hospice care team can be abrupt. Patients and their caregivers often feel abandoned by oncology clinicians because of the lack of continuity of care and poor communication.10-13 Caregivers who note continued involvement and communication with their oncology clinicians experience a lower caregiving burden, report higher satisfaction with care, and recount a higher quality of death for their loved one.14-16 Therefore, interventions that prevent abrupt transitions in care from oncology to hospice by ensuring continued communication with oncology clinicians are needed to improve the quality of end-of-life care.17 Recent findings have shown that providing concurrent oncology and palliative care is not only feasible but beneficial for patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers.18-24 However, there is no standard of care for the involvement of oncology clinicians in the care of patients receiving hospice services and their families.

Although interventions may be needed, it could be challenging to deliver them given the multiple demands of caregiving during hospice and the lack of regular contact in clinic. We sought to assess the feasibility of an intervention, Ensuring Communication in Hospice by Oncology (ECHO), to facilitate communication between oncology clinicians and caregivers of patients who enroll in hospice. We also explored caregiver-reported outcomes during hospice care, including satisfaction with care, attitudes toward caregiving, stress, decision regret, and perception of the quality of patients’ end-of-life care.

Methods

Study design

During March 2014-June 2015, caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who enrolled in home hospice services were eligible to participate in the study at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston. The Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved all methods and materials. The study opened with an enrollment goal of 30 participating caregivers. However, due to staff transitions, we closed the study early in June 2015 after 25 caregivers enrolled.

Participants

Caregivers of patients receiving care at the cancer center's thoracic, head and neck, sarcoma, melanoma, and gynecological disease centers were eligible within 10 days after a patient’s enrollment in hospice. Five disease sites were selected to participate in the intervention. We defined caregivers as relatives or friends serving as the primary caregiver of the patient at home during hospice care. Other caregiver eligibility criteria included the ability to read and respond to questions in English or with a translator, access to a telephone and/or computer to communicate with oncology clinicians, and willingness to complete questionnaires. Caregivers were ineligible if the patient was participating in an ongoing palliative care trial.

To identify eligible caregivers, case managers from both the inpatient and outpatient settings, as well as the nurses based in participating disease centers, notified the research team of all patients referred to hospice. If the patient had received oncology care in one of our participating disease centers, the research team contacted their oncology clinician/s (physicians, nurse practitioners [NP], registered nurses [RN], and/or physician assistants [PA]) to inquire if the patient had an involved caregiver and to obtain permission to offer study participation. If the oncology clinician/s did not grant permission, we documented the reason. Otherwise, with permission, research staff contacted the caregiver by telephone to offer study participation and obtain verbal consent. We then sent participating caregivers a copy of the informed consent by mail or e-mail.

Intervention

The ECHO intervention consisted of: supportive phone calls from an oncology clinician to the caregiver; an optional clinic visit with the oncology clinician for the patient to address clinical questions or concerns that was offered during the initial telephone consent; a bereavement call to the participating caregiver (Figure 1). Initially, we designed the intervention to have phone calls occurring twice weekly until the patient died. However, 3 months after starting the study, we received feedback from oncology clinicians and caregivers that calls were too frequent, so we amended the protocol to include phone calls twice weekly for the first 2 weeks of the study and then weekly thereafter. Seven months into the study, we again decreased the number of phone calls to weekly for the first 4 weeks, every other week for 4 weeks, and then monthly until patient death. We informed caregivers of changes by e-mail.

Before we started the study, we conducted training sessions with oncology clinicians from the participating disease centers to review study procedures and expectations of the phone calls. Supportive phone calls during hospice were not a part of standard practice prior to the study. The RN, NP or PA, and/or physician who had an established relationship with the patient and caregiver completed the phone calls. They decided based on their respective relationships with the patients and their workloads who would call each week, though the majority of calls were conducted by the RN or NP. All the clinicians had experience comanaging patients with hospice agencies, and our general practice is for the oncology physician to serve as the hospice attending of record. The calls were intended to offer support and reassurance to caregivers. We did not script the calls so that clinicians could tailor their content to the individual needs of the caregiver, as informed by their established relationship. The calls could include the patient if he/she was able to and interested in speaking to the clinician. There was no standardized communication with hospice as part of the intervention. If a caregiver raised concerns about symptom management during a call, the clinician would advise the caregiver to contact the hospice team directly or the clinician would call the hospice to discuss, depending on the clinical scenario and the clinician’s judgment. Research staff reminded oncology clinicians to call caregivers on the scheduled date and to document the discussion in the electronic medical record. The hospice phone number was included in the e-mail. If the call was not documented, research staff sent a reminder e-mail to the oncology clinicians 24 hours after the call was due.

Caregiver-reported measures

Caregivers completed a demographic questionnaire at baseline in which they reported their age, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, employment status, and relationship to the patient. We collected information about patient characteristics from the electronic medical record, including age, gender, and cancer type. In addition, we administered validated, self-report measures (see below). We limited the number of measures to decrease caregiver burden:

The baseline questionnaire included the FACQ-PC, the FAMCARE scale, the PSS, and the Decision Regret Scale. Initially, the study involved weekly questionnaires after baseline that included the FACQ-PC, the FAMCARE scale, and the PSS. However, after 3 months of study enrollment, we received feedback that the questionnaires were too frequent, so we amended the protocol and changed the frequency to weekly for 2 weeks, then monthly thereafter until the patient died.

Caregiver exit interview

Exit interviews included the toolkit interview, the Quality of End-of-Life Care scale, and the Decision Regret Scale. Caregivers also reported patients’ place and date of death. After the first 6 caregivers enrolled, we amended the exit interview to include open-ended feedback from caregivers. Specifically, we evaluated caregivers’ perceptions of the ECHO intervention by asking them about their perception of and satisfaction with the content and frequency of the oncology clinicians’ phone calls, whether they had an in-person visit with their oncology clinicians after the start of hospice care, whether the clinician/s contacted them after the patient died, and whether there were ways in which the clinician/s could help in the future.

Data collection and storage

Caregivers were given the option of completing study measures by telephone or e-mail so that they could complete them on a computer when it was convenient for them. Caregivers received a link to Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a web-based, HIPAA-compliant application that allows participants to answer questionnaires online. The exit interviews were completed by phone, and research staff entered the data into the REDCap database. In addition, with we obtained caregiver permission to audiorecord the exit interviews, which were then transcribed and de-identified.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome for the study was feasibility, which we defined as >70% of the caregivers receiving >50% of the phone calls from an oncology clinician, and >70% of the caregivers completing >50% of the questionnaires. All time points for the questionnaires and the exit interview counted toward feasibility. Exploratory endpoints included caregiver-reported satisfaction, stress, quality of end-of-life care, and decision-making regret.

Using STATA (v9.3; StataCorp, College Station, Texas) for all statistical analyses, we summarized participants’ characteristics and outcomes as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and mean standard deviation for continuous variables. We used the repeated-measures t test to assess changes in caregiver outcomes over time. We used the Fisher exact test to compare clinically meaningful threshold scores of perceived stress between men and women.

We examined caregivers’ open-ended feedback using descriptive analyses to summarize comments about the intervention and to inform possible refinements for a future study.

Results

Baseline characteristics

During March 2014-June 2015, we enrolled caregivers of patients with advanced cancer from 5 participating disease centers: thoracic, head and neck, sarcoma, melanoma, and gynecological malignancy. We screened 123 patients to determine the eligibility of their caregivers (Figure 2). Of 38 eligible caregivers, 7 could not be reached, 6 declined participation, and 25 enrolled in the study (81% enrollment rate). Of the 25 caregivers who enrolled, 3 withdrew – 2 because the patients they were caring for died before the intervention began, and 1 who withdrew from the study because the family wanted less contact with the oncology clinician/s. Thus, we had data for 22 caregivers for our feasibility evaluation. One caregiver stopped study assessments after 3 months because the patient dis-enrolled from hospice. Median time from the patients’ hospice enrollment to caregiver study enrollment was 3 days (range, 1-9). Median time from study enrollment to patient death was 36 days (range, 2-135). Patients were receiving care from 10 different hospice agencies.

All of the patients had metastatic cancer, and 64% were women (Table 1).

Most of the caregivers were white (n = 18, 90%) and women (n = 12, 55%). The majority were the patient’s spouse (n = 12, 60%) or child (n = 6, 30%), and they lived with the patient (n = 16, 80%). Many of the caregivers had other responsibilities in addition to caring for the patients, including part- or full-time work (n = 10, 50%) or caring for others in addition to the patient (n = 10, 50%).

Feasibility

Over the study period, oncology clinicians completed 164 of 180 possible phone calls (91%). All 22 caregivers received >50% of the phone calls. Caregivers completed 78 of 99 possible questionnaires (79%), and 16 of 22 completed >50% of the questionnaires (73%). None of the caregivers/patients wanted to schedule the optional visit with an oncology clinician that was offered as part of the intervention; however, 5 patients had a clinic visit after hospice enrollment. In addition, 2 oncologists visited a patient and caregiver at home. All caregivers received bereavement contact from the oncology team.

Caregiver-reported outcomes

In all, 20 of the 22 enrolled caregivers completed baseline measures (Table 2), and they all chose to complete questionnaires by e-mail. Caregivers’ attitudes toward caregiving and satisfaction with hospice services were overall positive. They reported high mean scores on the 2 domains on the FACQ-PC of positive caregiver appraisal (mean, 4.25; SD, 0.52) and family well-being (mean, 4.09; SD, 0.45). The majority of caregivers (75%-95%) reported they were satisfied or very satisfied with various dimensions of hospice care based on the FAMCARE questionnaire.

Overall, caregivers reported moderate levels of stress (mean, 13.55; SD, 6.08) based on the PSS scores. Of the 20 caregivers who completed the baseline measures, 8 had clinically meaningful stress, and stress was numerically higher in female caregivers than in their male counterparts, but it did not reach statistical significance (55% vs 22%, P = .197). Finally, at baseline, caregivers indicated relatively low levels of decisional regret about enrolling in hospice, although there was considerable variation (mean, 10.25; SD, 14.37).

We conducted exit interviews with 15 caregivers because we were not able to reach 6 of the original 21 (Table 2). Caregivers rated hospice services highly for communication, symptom control, emotional support, and overall care. They also rated quality of death highly (mean, 8.46; SD 1.13). Regret was lower at the end of the study, but this did not reach statistical significance (baseline mean 9.29; end of study mean 3.57; P = .161).

In the recorded exit interviews, all of the caregivers responded they were satisfied with the phone calls. Two caregivers commented that they would have preferred the calls were more scheduled or at more suitable times. Overall, they described the phone calls as excellent, supportive, responsive, comfortable, and appreciated. All caregivers reported contact with the oncology team after the patient died, but one caregiver was disappointed she was only contacted by the nurse practitioner and not the oncologist. Participants did not feel as if there were other ways that the oncology team could have been helpful for them while their loved one was in hospice.

Table 3 highlights other representative comments from the exit interviews.

Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first study to assess the feasibility of an intervention to facilitate communication between oncology clinicians and caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who are receiving hospice care. Despite the challenges of oncology clinicians delivering an intervention to caregivers during hospice, we found this intervention was feasible and acceptable. Although the transition to hospice can be stressful, caregivers reported high satisfaction with hospice care and the quality of the patient’s death. In exit interviews, they also reported high satisfaction with the intervention and appreciation for maintaining their relationship with the oncology team. It is worth noting that no caregiver requested the optional clinic visit after hospice enrollment, and most caregivers were not seen again in clinic after hospice enrollment.

These results suggest that a simple, telephone-based intervention of scheduled calls from the oncology team at prompted intervals is not only feasible, but may also help foster continuity between the patient and caregiver and the oncology team. We received feedback from both oncology clinicians and caregivers that the initial call frequency was too often, suggesting that communication may not need to be very frequent to maintain continuity and provide support. This also suggests that if the calls are too frequent, they may be more intrusive than helpful for both oncologists and caregivers. Alternatively, caregiver suggestion for fewer phone calls may indicate that concerns about abandonment are less prevalent than existing literature has suggested.

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations. The sample size was small as this was a feasibility study conducted at a single tertiary care hospital, and the population was 90% white and 95% college educated, which may limit the generalizability of our results. In addition, the median length of stay in hospice for patients on this study was 36 days, which is long compared with national averages,32,33 and thus the outcomes may not represent the experience of a more heterogeneous population. The longer length of stay in hospice may have contributed to caregivers’ high satisfaction with the quality of end-of-life care.

Oncologists did not grant permission for the study team to approach all eligible caregivers, which may have introduced selection bias. We were also not able to reach 6 participants for exit interviews. People less satisfied with the intervention or with hospice may be more likely to have missing data, which could introduce bias into the satisfaction ratings. Furthermore, we did not explore the oncology clinicians’ perspective of the intervention or assess the time commitment of the calls. Oncology clinicians have many competing responsibilities and have variable experience and comfort with hospice care. Therefore, future studies should explore the perspective of oncology clinicians in regard to the intervention.

Finally, we did not require communication with the hospice agency as part of the intervention as there were ten different hospices involved. Thus, we do not know how the intervention impacted the hospice team’s care of the patient. However, based upon the success of this pilot study, future larger studies should explore the impact of the intervention from the perspective of the hospice care team and include oncology clinician communication with the hospice agency.

Conclusion

These findings demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability of an intervention to enhance communication between oncology clinicians and caregivers of patients with advanced cancer receiving hospice care. Importantly, the high caregiver satisfaction with the intervention in this study suggests that maintaining communication with the primary oncology team during hospice care may be an important component of high quality end-of-life care, though the desire for decreased calls suggests that this communication need not be frequent to maintain the continuity. A randomized study with a larger and more diverse patient/caregiver sample would allow us to explore the impact of the intervention on caregiver feelings of abandonment by the oncology team and short- and long-term caregiver outcomes, as well as to understand the perspective of the oncology and hospice clinicians involved.

Improving the delivery of end-of-life care for patients with advanced cancer has become a priority in the United States.1,2 Quality metrics identifying the components of high-quality end-of-life care have focused on improved symptom management, decreased use of chemotherapy at the end of life, fewer hospitalizations, and increased use of hospice care. Patients and caregivers also consider good communication with the medical team to be a critical component of end-of-life care.3-5 Interventions to improve the quality of end-of-life care are needed.

Caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who receive hospice services report better quality of care and death than those receiving end-of-life care in other settings.6-9 However, the transition for patients from active cancer therapy delivered by their oncologists to end-of-life care delivered by a hospice care team can be abrupt. Patients and their caregivers often feel abandoned by oncology clinicians because of the lack of continuity of care and poor communication.10-13 Caregivers who note continued involvement and communication with their oncology clinicians experience a lower caregiving burden, report higher satisfaction with care, and recount a higher quality of death for their loved one.14-16 Therefore, interventions that prevent abrupt transitions in care from oncology to hospice by ensuring continued communication with oncology clinicians are needed to improve the quality of end-of-life care.17 Recent findings have shown that providing concurrent oncology and palliative care is not only feasible but beneficial for patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers.18-24 However, there is no standard of care for the involvement of oncology clinicians in the care of patients receiving hospice services and their families.

Although interventions may be needed, it could be challenging to deliver them given the multiple demands of caregiving during hospice and the lack of regular contact in clinic. We sought to assess the feasibility of an intervention, Ensuring Communication in Hospice by Oncology (ECHO), to facilitate communication between oncology clinicians and caregivers of patients who enroll in hospice. We also explored caregiver-reported outcomes during hospice care, including satisfaction with care, attitudes toward caregiving, stress, decision regret, and perception of the quality of patients’ end-of-life care.

Methods

Study design

During March 2014-June 2015, caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who enrolled in home hospice services were eligible to participate in the study at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston. The Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved all methods and materials. The study opened with an enrollment goal of 30 participating caregivers. However, due to staff transitions, we closed the study early in June 2015 after 25 caregivers enrolled.

Participants

Caregivers of patients receiving care at the cancer center's thoracic, head and neck, sarcoma, melanoma, and gynecological disease centers were eligible within 10 days after a patient’s enrollment in hospice. Five disease sites were selected to participate in the intervention. We defined caregivers as relatives or friends serving as the primary caregiver of the patient at home during hospice care. Other caregiver eligibility criteria included the ability to read and respond to questions in English or with a translator, access to a telephone and/or computer to communicate with oncology clinicians, and willingness to complete questionnaires. Caregivers were ineligible if the patient was participating in an ongoing palliative care trial.

To identify eligible caregivers, case managers from both the inpatient and outpatient settings, as well as the nurses based in participating disease centers, notified the research team of all patients referred to hospice. If the patient had received oncology care in one of our participating disease centers, the research team contacted their oncology clinician/s (physicians, nurse practitioners [NP], registered nurses [RN], and/or physician assistants [PA]) to inquire if the patient had an involved caregiver and to obtain permission to offer study participation. If the oncology clinician/s did not grant permission, we documented the reason. Otherwise, with permission, research staff contacted the caregiver by telephone to offer study participation and obtain verbal consent. We then sent participating caregivers a copy of the informed consent by mail or e-mail.

Intervention

The ECHO intervention consisted of: supportive phone calls from an oncology clinician to the caregiver; an optional clinic visit with the oncology clinician for the patient to address clinical questions or concerns that was offered during the initial telephone consent; a bereavement call to the participating caregiver (Figure 1). Initially, we designed the intervention to have phone calls occurring twice weekly until the patient died. However, 3 months after starting the study, we received feedback from oncology clinicians and caregivers that calls were too frequent, so we amended the protocol to include phone calls twice weekly for the first 2 weeks of the study and then weekly thereafter. Seven months into the study, we again decreased the number of phone calls to weekly for the first 4 weeks, every other week for 4 weeks, and then monthly until patient death. We informed caregivers of changes by e-mail.

Before we started the study, we conducted training sessions with oncology clinicians from the participating disease centers to review study procedures and expectations of the phone calls. Supportive phone calls during hospice were not a part of standard practice prior to the study. The RN, NP or PA, and/or physician who had an established relationship with the patient and caregiver completed the phone calls. They decided based on their respective relationships with the patients and their workloads who would call each week, though the majority of calls were conducted by the RN or NP. All the clinicians had experience comanaging patients with hospice agencies, and our general practice is for the oncology physician to serve as the hospice attending of record. The calls were intended to offer support and reassurance to caregivers. We did not script the calls so that clinicians could tailor their content to the individual needs of the caregiver, as informed by their established relationship. The calls could include the patient if he/she was able to and interested in speaking to the clinician. There was no standardized communication with hospice as part of the intervention. If a caregiver raised concerns about symptom management during a call, the clinician would advise the caregiver to contact the hospice team directly or the clinician would call the hospice to discuss, depending on the clinical scenario and the clinician’s judgment. Research staff reminded oncology clinicians to call caregivers on the scheduled date and to document the discussion in the electronic medical record. The hospice phone number was included in the e-mail. If the call was not documented, research staff sent a reminder e-mail to the oncology clinicians 24 hours after the call was due.

Caregiver-reported measures

Caregivers completed a demographic questionnaire at baseline in which they reported their age, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, employment status, and relationship to the patient. We collected information about patient characteristics from the electronic medical record, including age, gender, and cancer type. In addition, we administered validated, self-report measures (see below). We limited the number of measures to decrease caregiver burden:

The baseline questionnaire included the FACQ-PC, the FAMCARE scale, the PSS, and the Decision Regret Scale. Initially, the study involved weekly questionnaires after baseline that included the FACQ-PC, the FAMCARE scale, and the PSS. However, after 3 months of study enrollment, we received feedback that the questionnaires were too frequent, so we amended the protocol and changed the frequency to weekly for 2 weeks, then monthly thereafter until the patient died.

Caregiver exit interview

Exit interviews included the toolkit interview, the Quality of End-of-Life Care scale, and the Decision Regret Scale. Caregivers also reported patients’ place and date of death. After the first 6 caregivers enrolled, we amended the exit interview to include open-ended feedback from caregivers. Specifically, we evaluated caregivers’ perceptions of the ECHO intervention by asking them about their perception of and satisfaction with the content and frequency of the oncology clinicians’ phone calls, whether they had an in-person visit with their oncology clinicians after the start of hospice care, whether the clinician/s contacted them after the patient died, and whether there were ways in which the clinician/s could help in the future.

Data collection and storage

Caregivers were given the option of completing study measures by telephone or e-mail so that they could complete them on a computer when it was convenient for them. Caregivers received a link to Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a web-based, HIPAA-compliant application that allows participants to answer questionnaires online. The exit interviews were completed by phone, and research staff entered the data into the REDCap database. In addition, with we obtained caregiver permission to audiorecord the exit interviews, which were then transcribed and de-identified.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome for the study was feasibility, which we defined as >70% of the caregivers receiving >50% of the phone calls from an oncology clinician, and >70% of the caregivers completing >50% of the questionnaires. All time points for the questionnaires and the exit interview counted toward feasibility. Exploratory endpoints included caregiver-reported satisfaction, stress, quality of end-of-life care, and decision-making regret.

Using STATA (v9.3; StataCorp, College Station, Texas) for all statistical analyses, we summarized participants’ characteristics and outcomes as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and mean standard deviation for continuous variables. We used the repeated-measures t test to assess changes in caregiver outcomes over time. We used the Fisher exact test to compare clinically meaningful threshold scores of perceived stress between men and women.

We examined caregivers’ open-ended feedback using descriptive analyses to summarize comments about the intervention and to inform possible refinements for a future study.

Results

Baseline characteristics

During March 2014-June 2015, we enrolled caregivers of patients with advanced cancer from 5 participating disease centers: thoracic, head and neck, sarcoma, melanoma, and gynecological malignancy. We screened 123 patients to determine the eligibility of their caregivers (Figure 2). Of 38 eligible caregivers, 7 could not be reached, 6 declined participation, and 25 enrolled in the study (81% enrollment rate). Of the 25 caregivers who enrolled, 3 withdrew – 2 because the patients they were caring for died before the intervention began, and 1 who withdrew from the study because the family wanted less contact with the oncology clinician/s. Thus, we had data for 22 caregivers for our feasibility evaluation. One caregiver stopped study assessments after 3 months because the patient dis-enrolled from hospice. Median time from the patients’ hospice enrollment to caregiver study enrollment was 3 days (range, 1-9). Median time from study enrollment to patient death was 36 days (range, 2-135). Patients were receiving care from 10 different hospice agencies.

All of the patients had metastatic cancer, and 64% were women (Table 1).

Most of the caregivers were white (n = 18, 90%) and women (n = 12, 55%). The majority were the patient’s spouse (n = 12, 60%) or child (n = 6, 30%), and they lived with the patient (n = 16, 80%). Many of the caregivers had other responsibilities in addition to caring for the patients, including part- or full-time work (n = 10, 50%) or caring for others in addition to the patient (n = 10, 50%).

Feasibility

Over the study period, oncology clinicians completed 164 of 180 possible phone calls (91%). All 22 caregivers received >50% of the phone calls. Caregivers completed 78 of 99 possible questionnaires (79%), and 16 of 22 completed >50% of the questionnaires (73%). None of the caregivers/patients wanted to schedule the optional visit with an oncology clinician that was offered as part of the intervention; however, 5 patients had a clinic visit after hospice enrollment. In addition, 2 oncologists visited a patient and caregiver at home. All caregivers received bereavement contact from the oncology team.

Caregiver-reported outcomes

In all, 20 of the 22 enrolled caregivers completed baseline measures (Table 2), and they all chose to complete questionnaires by e-mail. Caregivers’ attitudes toward caregiving and satisfaction with hospice services were overall positive. They reported high mean scores on the 2 domains on the FACQ-PC of positive caregiver appraisal (mean, 4.25; SD, 0.52) and family well-being (mean, 4.09; SD, 0.45). The majority of caregivers (75%-95%) reported they were satisfied or very satisfied with various dimensions of hospice care based on the FAMCARE questionnaire.

Overall, caregivers reported moderate levels of stress (mean, 13.55; SD, 6.08) based on the PSS scores. Of the 20 caregivers who completed the baseline measures, 8 had clinically meaningful stress, and stress was numerically higher in female caregivers than in their male counterparts, but it did not reach statistical significance (55% vs 22%, P = .197). Finally, at baseline, caregivers indicated relatively low levels of decisional regret about enrolling in hospice, although there was considerable variation (mean, 10.25; SD, 14.37).

We conducted exit interviews with 15 caregivers because we were not able to reach 6 of the original 21 (Table 2). Caregivers rated hospice services highly for communication, symptom control, emotional support, and overall care. They also rated quality of death highly (mean, 8.46; SD 1.13). Regret was lower at the end of the study, but this did not reach statistical significance (baseline mean 9.29; end of study mean 3.57; P = .161).

In the recorded exit interviews, all of the caregivers responded they were satisfied with the phone calls. Two caregivers commented that they would have preferred the calls were more scheduled or at more suitable times. Overall, they described the phone calls as excellent, supportive, responsive, comfortable, and appreciated. All caregivers reported contact with the oncology team after the patient died, but one caregiver was disappointed she was only contacted by the nurse practitioner and not the oncologist. Participants did not feel as if there were other ways that the oncology team could have been helpful for them while their loved one was in hospice.

Table 3 highlights other representative comments from the exit interviews.

Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first study to assess the feasibility of an intervention to facilitate communication between oncology clinicians and caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who are receiving hospice care. Despite the challenges of oncology clinicians delivering an intervention to caregivers during hospice, we found this intervention was feasible and acceptable. Although the transition to hospice can be stressful, caregivers reported high satisfaction with hospice care and the quality of the patient’s death. In exit interviews, they also reported high satisfaction with the intervention and appreciation for maintaining their relationship with the oncology team. It is worth noting that no caregiver requested the optional clinic visit after hospice enrollment, and most caregivers were not seen again in clinic after hospice enrollment.

These results suggest that a simple, telephone-based intervention of scheduled calls from the oncology team at prompted intervals is not only feasible, but may also help foster continuity between the patient and caregiver and the oncology team. We received feedback from both oncology clinicians and caregivers that the initial call frequency was too often, suggesting that communication may not need to be very frequent to maintain continuity and provide support. This also suggests that if the calls are too frequent, they may be more intrusive than helpful for both oncologists and caregivers. Alternatively, caregiver suggestion for fewer phone calls may indicate that concerns about abandonment are less prevalent than existing literature has suggested.

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations. The sample size was small as this was a feasibility study conducted at a single tertiary care hospital, and the population was 90% white and 95% college educated, which may limit the generalizability of our results. In addition, the median length of stay in hospice for patients on this study was 36 days, which is long compared with national averages,32,33 and thus the outcomes may not represent the experience of a more heterogeneous population. The longer length of stay in hospice may have contributed to caregivers’ high satisfaction with the quality of end-of-life care.

Oncologists did not grant permission for the study team to approach all eligible caregivers, which may have introduced selection bias. We were also not able to reach 6 participants for exit interviews. People less satisfied with the intervention or with hospice may be more likely to have missing data, which could introduce bias into the satisfaction ratings. Furthermore, we did not explore the oncology clinicians’ perspective of the intervention or assess the time commitment of the calls. Oncology clinicians have many competing responsibilities and have variable experience and comfort with hospice care. Therefore, future studies should explore the perspective of oncology clinicians in regard to the intervention.

Finally, we did not require communication with the hospice agency as part of the intervention as there were ten different hospices involved. Thus, we do not know how the intervention impacted the hospice team’s care of the patient. However, based upon the success of this pilot study, future larger studies should explore the impact of the intervention from the perspective of the hospice care team and include oncology clinician communication with the hospice agency.

Conclusion

These findings demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability of an intervention to enhance communication between oncology clinicians and caregivers of patients with advanced cancer receiving hospice care. Importantly, the high caregiver satisfaction with the intervention in this study suggests that maintaining communication with the primary oncology team during hospice care may be an important component of high quality end-of-life care, though the desire for decreased calls suggests that this communication need not be frequent to maintain the continuity. A randomized study with a larger and more diverse patient/caregiver sample would allow us to explore the impact of the intervention on caregiver feelings of abandonment by the oncology team and short- and long-term caregiver outcomes, as well as to understand the perspective of the oncology and hospice clinicians involved.

1. Institute of Medicine. 2015. Dying in america: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18748.

2. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):96-112.

3. Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Shannon SE, Carline JD, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Communicating with dying patients within the spectrum of medical care from terminal diagnosis to death. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(6):868-874.

4. Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(1):81-93.

5. Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, Christakis NA, McIntyre LM, Tulsky JA. In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(10):825-832.

6. Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291(1):88-93.

7. Kumar P, Wright AA, Hatfield LA, Temel JS, Keating NL. Family perspectives on hospice care experiences of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(4):432-439.

8. Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA. 2016;315(3):284-292.

9. Duggan KT, Hildebrand Duffus S, D’Agostino RB Jr, Petty WJ, Streer NP, Stephenson RC. The impact of hospice services in the care of patients with advanced stage nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(1):29-34.

10. Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Understanding physicians’ skills at providing end-of-life care perspectives of patients, families, and health care workers. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(1):41-49.

11. Back AL, Young JP, McCown E, et al. Abandonment at the end of life from patient, caregiver, nurse, and physician perspectives: loss of continuity and lack of closure. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):474-479.

12. Vig EK, Starks H, Taylor JS, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Why don’t patients enroll in hospice? Can we do anything about it? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(10):1009-1019.

13. Waldrop DP, Meeker MA, Kerr C, Skretny J, Tangeman J, Milch R. The nature and timing of family-provider communication in late-stage cancer: a qualitative study of caregivers’ experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43(2):182-194.

14. Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J, Emanuel LL. Understanding economic and other burdens of terminal illness: the experience of patients and their caregivers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(6):451-459.

15. Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Norris K, Asp C, Byock I. A measure of the quality of dying and death. Initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(1):17-31.

16. Fleming DA, Sheppard VB, Mangan PA, et al. Caregiving at the end of life: Perceptions of health care quality and quality of life among patients and caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(5):407-420.

17. McMillan SC. Interventions to facilitate family caregiving at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(Suppl 1):S132-S139.

18. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741-749.

19. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742.

20. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721-1730.

21. Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Dall’Agata M, et al. Systematic versus on-demand early palliative care: a randomised clinical trial assessing quality of care and treatment aggressiveness near the end of life. Eur J Cancer. 2016;69:110-118.

22. El-Jawahri A ea. Early integrated palliative care to improve family caregivers (FC) outcomes for patients with gastrointestinal and lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl; abstr 10131).

23. Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and gi cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):834-841.

24. El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H, et al. Effect of inpatient palliative care on quality of life 2 weeks after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2094-2103.

25. Cooper B, Kinsella GJ, Picton C. Development and initial validation of a family appraisal of caregiving questionnaire for palliative care. Psychooncology. 2006;15(7):613-622.

26. Kristjanson LJ. Validity and reliability testing of the FAMCARE Scale: measuring family satisfaction with advanced cancer care. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(5):693-701.

27. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385-396.

28. Keir ST, Guill AB, Carter KE, Boole LC, Gonzales L, Friedman HS. Differential levels of stress in caregivers of brain tumor patients--observations from a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(12):1258-1261.

29. Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ, et al. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making. 2003;23(4):281-292.

30. Teno JM, Clarridge B, Casey V, Edgman-Levitan S, Fowler J. Validation of toolkit after-death bereaved family member interview. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22(3):752-758.

31. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665-1673.

32. Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(2):315-321.

33. Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, Dominici F, Block S, Cutler DM. Association between the Medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA. 2014;312(18):1888-1896.

1. Institute of Medicine. 2015. Dying in america: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18748.

2. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):96-112.

3. Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Shannon SE, Carline JD, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Communicating with dying patients within the spectrum of medical care from terminal diagnosis to death. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(6):868-874.

4. Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(1):81-93.

5. Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, Christakis NA, McIntyre LM, Tulsky JA. In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(10):825-832.

6. Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291(1):88-93.

7. Kumar P, Wright AA, Hatfield LA, Temel JS, Keating NL. Family perspectives on hospice care experiences of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(4):432-439.

8. Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA. 2016;315(3):284-292.

9. Duggan KT, Hildebrand Duffus S, D’Agostino RB Jr, Petty WJ, Streer NP, Stephenson RC. The impact of hospice services in the care of patients with advanced stage nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(1):29-34.

10. Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Understanding physicians’ skills at providing end-of-life care perspectives of patients, families, and health care workers. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(1):41-49.

11. Back AL, Young JP, McCown E, et al. Abandonment at the end of life from patient, caregiver, nurse, and physician perspectives: loss of continuity and lack of closure. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):474-479.

12. Vig EK, Starks H, Taylor JS, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Why don’t patients enroll in hospice? Can we do anything about it? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(10):1009-1019.

13. Waldrop DP, Meeker MA, Kerr C, Skretny J, Tangeman J, Milch R. The nature and timing of family-provider communication in late-stage cancer: a qualitative study of caregivers’ experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43(2):182-194.

14. Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J, Emanuel LL. Understanding economic and other burdens of terminal illness: the experience of patients and their caregivers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(6):451-459.

15. Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Norris K, Asp C, Byock I. A measure of the quality of dying and death. Initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(1):17-31.

16. Fleming DA, Sheppard VB, Mangan PA, et al. Caregiving at the end of life: Perceptions of health care quality and quality of life among patients and caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(5):407-420.

17. McMillan SC. Interventions to facilitate family caregiving at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(Suppl 1):S132-S139.

18. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741-749.

19. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742.

20. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721-1730.

21. Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Dall’Agata M, et al. Systematic versus on-demand early palliative care: a randomised clinical trial assessing quality of care and treatment aggressiveness near the end of life. Eur J Cancer. 2016;69:110-118.

22. El-Jawahri A ea. Early integrated palliative care to improve family caregivers (FC) outcomes for patients with gastrointestinal and lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl; abstr 10131).

23. Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and gi cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):834-841.

24. El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H, et al. Effect of inpatient palliative care on quality of life 2 weeks after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2094-2103.

25. Cooper B, Kinsella GJ, Picton C. Development and initial validation of a family appraisal of caregiving questionnaire for palliative care. Psychooncology. 2006;15(7):613-622.

26. Kristjanson LJ. Validity and reliability testing of the FAMCARE Scale: measuring family satisfaction with advanced cancer care. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(5):693-701.

27. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385-396.

28. Keir ST, Guill AB, Carter KE, Boole LC, Gonzales L, Friedman HS. Differential levels of stress in caregivers of brain tumor patients--observations from a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(12):1258-1261.

29. Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ, et al. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making. 2003;23(4):281-292.

30. Teno JM, Clarridge B, Casey V, Edgman-Levitan S, Fowler J. Validation of toolkit after-death bereaved family member interview. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22(3):752-758.

31. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665-1673.

32. Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(2):315-321.

33. Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, Dominici F, Block S, Cutler DM. Association between the Medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA. 2014;312(18):1888-1896.