User login

Pleuritic chest pain and globus pharyngeus

A 22-year-old woman with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and childhood asthma came to the emergency department (ED) for treatment of a cramping, substernal, pleuritic chest pain she’d had for a week and the feeling of a “lump in her throat” that made it difficult and painful for her to swallow. The patient’s vital signs were normal and her substernal chest pain was reproducible with palpation. An anteroposterior (AP) chest x-ray (CXR) was unremarkable.

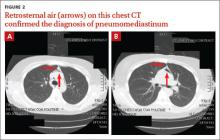

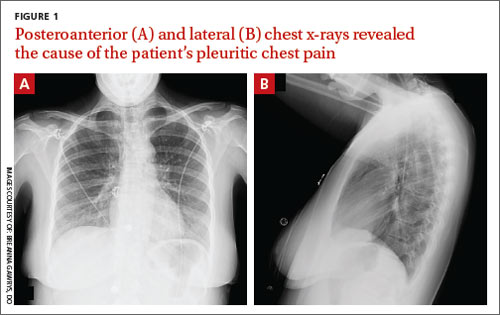

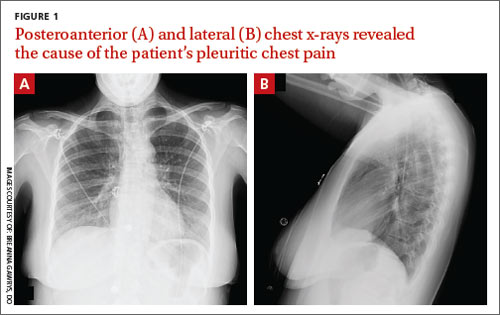

A “GI cocktail” (lidocaine, Mylanta and Donnatal), ketorolac, morphine, and lorazepam were administered in the ED, but did not provide the patient with any relief. She was admitted to the hospital to rule out acute coronary syndrome and was kept NPO overnight. A repeat CXR with posteroanterior (PA) and lateral views was also obtained (FIGURE 1A AND 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pneumomediastinum

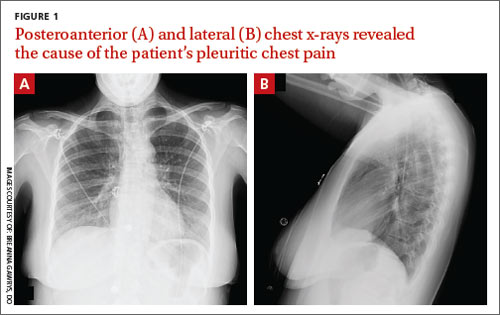

The PA and lateral view CXRs revealed the presence of retrosternal air, suggesting the patient had pneumomediastinum. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest also showed retrosternal air (FIGURE 2A AND 2B, arrows) and confirmed this diagnosis. To rule out esophageal perforation, the team ordered Gastrografin and barium swallow studies. The patient was kept NPO until both studies were confirmed to be negative.

Pneumomediastinum—the presence of free air in the mediastinum—can develop spontaneously (as was the case with our patient) or in response to trauma. Common causes include respiratory diseases such as asthma, and trauma to the esophagus secondary to mechanical ventilation, endoscopy, and excessive vomiting.1 Other possible causes include respiratory infections, foreign body aspiration, recent dental extraction, diabetic ketoacidosis, esophageal perforation, barotrauma (due to activities such as flying or scuba diving), and use of illicit drugs.1

Patients with pneumomediastinum often complain of retrosternal, pleuritic pain that radiates to their back, shoulders, and arms. They may also have difficulty swallowing (globus pharyngeus), a nasal voice, and/or dyspnea. Physical findings can include subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and supraclavicular fossa as manifested by Hamman’s sign (a precordial “crunching” sound heard during systole), a fever, and distended neck veins.1

Differential diagnosis includes inflammatory conditions

The differential diagnosis for pneumomediastinum includes pericarditis, mediastinitis, Boerhaave syndrome, and acute coronary syndrome.

Pericarditis. In a patient with inflammation of the pericardium, you would hear reduced heart sounds and observe electrocardiogram (EKG) changes (eg, diffuse ST elevation in acute pericarditis). These signs typically would not be present in a patient with pneumomediastinum.1

Mediastinitis. Patients with mediastinitis—inflammation of the mediastinum—are more likely to have hypotension and shock.1

Boerhaave syndrome, or spontaneous esophageal perforation, has a similar presentation to pneumomediastinum but is more likely to be accompanied by hypotension and shock. Additionally, there would be extravasation of the contrast agent during swallow studies.2

Acute coronary syndrome is also part of the differential. However, in ACS, you would see ST changes on the patient’s EKG and elevated cardiac enzymes.1

Lateral x-rays are especially useful in making the diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by CXR and/or chest CT. On a CXR, retrosternal air is best seen in the lateral projection. Small amounts of air can appear as linear lucencies outlining mediastinal contours. This air can be seen under the skin, surrounding the pericardium, around the pulmonary and/or aortic vasculature, and/or between the parietal pleura and diaphragm.2 A pleural effusion—particularly on the patient’s left side—should raise concern for esophageal perforation.

For most patients, rest and pain control are key

Because pneumomediastinum is generally a self-limiting condition, patients who don’t have severe symptoms, such as respiratory distress or signs of inflammation, should be observed for 2 days, managed with rest and pain control, and discharged home.

If severe symptoms or inflammatory signs are present, a Gastrografin swallow study is recommended to rule out esophageal perforation. If the result of this test is abnormal, a follow-up study with barium is recommended.3 Gastrografin swallow studies are the preferred initial study.3 A barium swallow study is more sensitive, but has a higher risk of causing pneumomediastinitis if an esophageal perforation is present.2

If the swallow study reveals a perforation, surgical decompression and antibiotics may be necessary.1,4,5

Our patient received subsequent serial CXRs that showed improvement in pneumomediastinum. Once our patient’s pain was well controlled with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, she was discharged home after a 3-day hospitalization with close follow-up. One week later, she had no further complaints and her pain had almost entirely resolved.

CORRESPONDENCE

Breanna Gawrys, DO, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital Family Medicine Residency, 9300 DeWitt Loop, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

1. Park DE, Vallieres E. Pneumomediastinum and mediastinitis. In: Mason R, Broaddus V, Murray J, et al. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:2039–2068.

2. Zylak CM, Standen JR, Barnes GR, et al. Pneumomediastinum revisited. Radiographics. 2000;20:1043-1057.

3. Takada K, Matsumoto S, Hiramatsu T, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum based on clinical experience of 25 cases. Respir Med. 2008;102:1329-1334.

4. Macia I, Moya J, Ramos R, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: 41 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:1110-1114.

5. Chalumeau M, Le Clainche L, Sayeg N, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;31:67-75.

A 22-year-old woman with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and childhood asthma came to the emergency department (ED) for treatment of a cramping, substernal, pleuritic chest pain she’d had for a week and the feeling of a “lump in her throat” that made it difficult and painful for her to swallow. The patient’s vital signs were normal and her substernal chest pain was reproducible with palpation. An anteroposterior (AP) chest x-ray (CXR) was unremarkable.

A “GI cocktail” (lidocaine, Mylanta and Donnatal), ketorolac, morphine, and lorazepam were administered in the ED, but did not provide the patient with any relief. She was admitted to the hospital to rule out acute coronary syndrome and was kept NPO overnight. A repeat CXR with posteroanterior (PA) and lateral views was also obtained (FIGURE 1A AND 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pneumomediastinum

The PA and lateral view CXRs revealed the presence of retrosternal air, suggesting the patient had pneumomediastinum. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest also showed retrosternal air (FIGURE 2A AND 2B, arrows) and confirmed this diagnosis. To rule out esophageal perforation, the team ordered Gastrografin and barium swallow studies. The patient was kept NPO until both studies were confirmed to be negative.

Pneumomediastinum—the presence of free air in the mediastinum—can develop spontaneously (as was the case with our patient) or in response to trauma. Common causes include respiratory diseases such as asthma, and trauma to the esophagus secondary to mechanical ventilation, endoscopy, and excessive vomiting.1 Other possible causes include respiratory infections, foreign body aspiration, recent dental extraction, diabetic ketoacidosis, esophageal perforation, barotrauma (due to activities such as flying or scuba diving), and use of illicit drugs.1

Patients with pneumomediastinum often complain of retrosternal, pleuritic pain that radiates to their back, shoulders, and arms. They may also have difficulty swallowing (globus pharyngeus), a nasal voice, and/or dyspnea. Physical findings can include subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and supraclavicular fossa as manifested by Hamman’s sign (a precordial “crunching” sound heard during systole), a fever, and distended neck veins.1

Differential diagnosis includes inflammatory conditions

The differential diagnosis for pneumomediastinum includes pericarditis, mediastinitis, Boerhaave syndrome, and acute coronary syndrome.

Pericarditis. In a patient with inflammation of the pericardium, you would hear reduced heart sounds and observe electrocardiogram (EKG) changes (eg, diffuse ST elevation in acute pericarditis). These signs typically would not be present in a patient with pneumomediastinum.1

Mediastinitis. Patients with mediastinitis—inflammation of the mediastinum—are more likely to have hypotension and shock.1

Boerhaave syndrome, or spontaneous esophageal perforation, has a similar presentation to pneumomediastinum but is more likely to be accompanied by hypotension and shock. Additionally, there would be extravasation of the contrast agent during swallow studies.2

Acute coronary syndrome is also part of the differential. However, in ACS, you would see ST changes on the patient’s EKG and elevated cardiac enzymes.1

Lateral x-rays are especially useful in making the diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by CXR and/or chest CT. On a CXR, retrosternal air is best seen in the lateral projection. Small amounts of air can appear as linear lucencies outlining mediastinal contours. This air can be seen under the skin, surrounding the pericardium, around the pulmonary and/or aortic vasculature, and/or between the parietal pleura and diaphragm.2 A pleural effusion—particularly on the patient’s left side—should raise concern for esophageal perforation.

For most patients, rest and pain control are key

Because pneumomediastinum is generally a self-limiting condition, patients who don’t have severe symptoms, such as respiratory distress or signs of inflammation, should be observed for 2 days, managed with rest and pain control, and discharged home.

If severe symptoms or inflammatory signs are present, a Gastrografin swallow study is recommended to rule out esophageal perforation. If the result of this test is abnormal, a follow-up study with barium is recommended.3 Gastrografin swallow studies are the preferred initial study.3 A barium swallow study is more sensitive, but has a higher risk of causing pneumomediastinitis if an esophageal perforation is present.2

If the swallow study reveals a perforation, surgical decompression and antibiotics may be necessary.1,4,5

Our patient received subsequent serial CXRs that showed improvement in pneumomediastinum. Once our patient’s pain was well controlled with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, she was discharged home after a 3-day hospitalization with close follow-up. One week later, she had no further complaints and her pain had almost entirely resolved.

CORRESPONDENCE

Breanna Gawrys, DO, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital Family Medicine Residency, 9300 DeWitt Loop, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

A 22-year-old woman with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and childhood asthma came to the emergency department (ED) for treatment of a cramping, substernal, pleuritic chest pain she’d had for a week and the feeling of a “lump in her throat” that made it difficult and painful for her to swallow. The patient’s vital signs were normal and her substernal chest pain was reproducible with palpation. An anteroposterior (AP) chest x-ray (CXR) was unremarkable.

A “GI cocktail” (lidocaine, Mylanta and Donnatal), ketorolac, morphine, and lorazepam were administered in the ED, but did not provide the patient with any relief. She was admitted to the hospital to rule out acute coronary syndrome and was kept NPO overnight. A repeat CXR with posteroanterior (PA) and lateral views was also obtained (FIGURE 1A AND 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pneumomediastinum

The PA and lateral view CXRs revealed the presence of retrosternal air, suggesting the patient had pneumomediastinum. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest also showed retrosternal air (FIGURE 2A AND 2B, arrows) and confirmed this diagnosis. To rule out esophageal perforation, the team ordered Gastrografin and barium swallow studies. The patient was kept NPO until both studies were confirmed to be negative.

Pneumomediastinum—the presence of free air in the mediastinum—can develop spontaneously (as was the case with our patient) or in response to trauma. Common causes include respiratory diseases such as asthma, and trauma to the esophagus secondary to mechanical ventilation, endoscopy, and excessive vomiting.1 Other possible causes include respiratory infections, foreign body aspiration, recent dental extraction, diabetic ketoacidosis, esophageal perforation, barotrauma (due to activities such as flying or scuba diving), and use of illicit drugs.1

Patients with pneumomediastinum often complain of retrosternal, pleuritic pain that radiates to their back, shoulders, and arms. They may also have difficulty swallowing (globus pharyngeus), a nasal voice, and/or dyspnea. Physical findings can include subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and supraclavicular fossa as manifested by Hamman’s sign (a precordial “crunching” sound heard during systole), a fever, and distended neck veins.1

Differential diagnosis includes inflammatory conditions

The differential diagnosis for pneumomediastinum includes pericarditis, mediastinitis, Boerhaave syndrome, and acute coronary syndrome.

Pericarditis. In a patient with inflammation of the pericardium, you would hear reduced heart sounds and observe electrocardiogram (EKG) changes (eg, diffuse ST elevation in acute pericarditis). These signs typically would not be present in a patient with pneumomediastinum.1

Mediastinitis. Patients with mediastinitis—inflammation of the mediastinum—are more likely to have hypotension and shock.1

Boerhaave syndrome, or spontaneous esophageal perforation, has a similar presentation to pneumomediastinum but is more likely to be accompanied by hypotension and shock. Additionally, there would be extravasation of the contrast agent during swallow studies.2

Acute coronary syndrome is also part of the differential. However, in ACS, you would see ST changes on the patient’s EKG and elevated cardiac enzymes.1

Lateral x-rays are especially useful in making the diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by CXR and/or chest CT. On a CXR, retrosternal air is best seen in the lateral projection. Small amounts of air can appear as linear lucencies outlining mediastinal contours. This air can be seen under the skin, surrounding the pericardium, around the pulmonary and/or aortic vasculature, and/or between the parietal pleura and diaphragm.2 A pleural effusion—particularly on the patient’s left side—should raise concern for esophageal perforation.

For most patients, rest and pain control are key

Because pneumomediastinum is generally a self-limiting condition, patients who don’t have severe symptoms, such as respiratory distress or signs of inflammation, should be observed for 2 days, managed with rest and pain control, and discharged home.

If severe symptoms or inflammatory signs are present, a Gastrografin swallow study is recommended to rule out esophageal perforation. If the result of this test is abnormal, a follow-up study with barium is recommended.3 Gastrografin swallow studies are the preferred initial study.3 A barium swallow study is more sensitive, but has a higher risk of causing pneumomediastinitis if an esophageal perforation is present.2

If the swallow study reveals a perforation, surgical decompression and antibiotics may be necessary.1,4,5

Our patient received subsequent serial CXRs that showed improvement in pneumomediastinum. Once our patient’s pain was well controlled with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, she was discharged home after a 3-day hospitalization with close follow-up. One week later, she had no further complaints and her pain had almost entirely resolved.

CORRESPONDENCE

Breanna Gawrys, DO, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital Family Medicine Residency, 9300 DeWitt Loop, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

1. Park DE, Vallieres E. Pneumomediastinum and mediastinitis. In: Mason R, Broaddus V, Murray J, et al. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:2039–2068.

2. Zylak CM, Standen JR, Barnes GR, et al. Pneumomediastinum revisited. Radiographics. 2000;20:1043-1057.

3. Takada K, Matsumoto S, Hiramatsu T, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum based on clinical experience of 25 cases. Respir Med. 2008;102:1329-1334.

4. Macia I, Moya J, Ramos R, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: 41 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:1110-1114.

5. Chalumeau M, Le Clainche L, Sayeg N, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;31:67-75.

1. Park DE, Vallieres E. Pneumomediastinum and mediastinitis. In: Mason R, Broaddus V, Murray J, et al. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:2039–2068.

2. Zylak CM, Standen JR, Barnes GR, et al. Pneumomediastinum revisited. Radiographics. 2000;20:1043-1057.

3. Takada K, Matsumoto S, Hiramatsu T, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum based on clinical experience of 25 cases. Respir Med. 2008;102:1329-1334.

4. Macia I, Moya J, Ramos R, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: 41 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:1110-1114.

5. Chalumeau M, Le Clainche L, Sayeg N, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;31:67-75.