User login

‘Self-anesthetizing’ to cope with grief

CASE Grieving, delusional

Mr. M, age 51, is brought to the emergency department (ED) because of new-onset delusions and decreased self-care over the last 2 weeks following the sudden death of his wife. He has become expansive and grandiose, with pressured speech, increased energy, and markedly reduced sleep. Mr. M is preoccupied with the idea that he is “the first to survive a human reboot process” and says that his and his wife’s bodies and brains had been “split apart.” Mr. M has limited his food and fluid intake and lost 15 lb within the past 2 to 3 weeks.

Mr. M has no history of any affective, psychotic, or other major mental disorders or treatment. He reports that he has regularly used Cannabis over the last 10 years, and a few years ago, he started occasionally using nitrous oxide (N2O). He says that in the week following his wife’s death, he used N2O almost daily and in copious amounts. In an attempt to “self-anesthetize” himself after his wife’s funeral, he isolated himself in his bedroom and used escalating amounts of Cannabis and N2O, while continually working on a book about their life together.

At first, Mr. M shows little emotion and describes his situation as “interesting and fascinating.” He mentions that he thinks he might have been “psychotic” the week after his wife’s death, but he shows no sustained insight and immediately relapses into psychotic thinking. Over several hours in the ED, he is tearful and sad about his wife’s death. Mr. M recalls a similar experience of grief after his mother died when he was a teenager, but at that time he did not abuse substances or have psychotic symptoms. He is fully alert, fully oriented, and has no significant deficits of attention or memory.

[polldaddy:9859135]

The authors’ observations

Grief was a precipitating event, but by itself grief cannot explain psychosis. Psychotic depression is a possibility, but Mr. M’s psychotic features are incongruent with his mood. Mania would be a diagnosis of exclusion. Mr. M had no prior history of major affective illness. Mr. M was abusing Cannabis, which might independently contribute to psychosis1; however, he had been using it recreationally for 10 years without psychiatric problems. N2O, however, can cause symptoms consistent with Mr. M’s presentation.

[polldaddy:9859140]

EVALUATION Laboratory tests

Mr. M’s physical examination is notable only for an elevated blood pressure of 196/120 mm Hg. Neurologic examination is normal. Toxicology is positive for cannabinoids and negative for amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine. Chemistries are normal except for a potassium of 3.4 mEq/L (reference range, 3.7 to 5.2 mEq/L) and a blood urine nitrogen of 25 mg/dL (reference range, 6 to 20 mg/dL), which are consistent with reduced food and fluid intake. Mr. M shows no signs of anemia. Hematocrit is 42% and mean corpuscular volume is 90 fL. Syphilis screen is negative; a head CT scan is unremarkable.

The authors’ observations

N2O, also known as “laughing gas,” is routinely used by dentists and pediatric anesthesiologists, and has other medical uses. Some studies have examined an adjunctive use of N2O for pain control in the ED and during colonoscopies.3,4

In the 2013 U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 16% of respondents reported lifetime illicit use of N2O.5,6 It is readily available in tanks used in medicine and industry and in small dispensers called “whippits” that can be legally purchased. Acute effects of N2O include euphoric mood, numbness, feeling of warmth, dizziness, and auditory hallucinations.7 The anesthetic effects of N2O are linked to endogenous release of opiates, and recent research links its anxiolytic activity to the facilitation of GABAergic inhibitory and N-methyl-

Beginning with a 1960 report of a series of patients with “megaloblastic madness,”17 there have been calls for increased awareness of the potential for vitamin B12 deficiency–induced psychiatric disorders, even in the absence of other hematologic or neurologic sequelae that would alert clinicians of the deficiency. In a case series of 141 patients with a broad array of neurologic and psychiatric symptoms associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, 40 (28%) patients had no anemia or macrocytosis.2

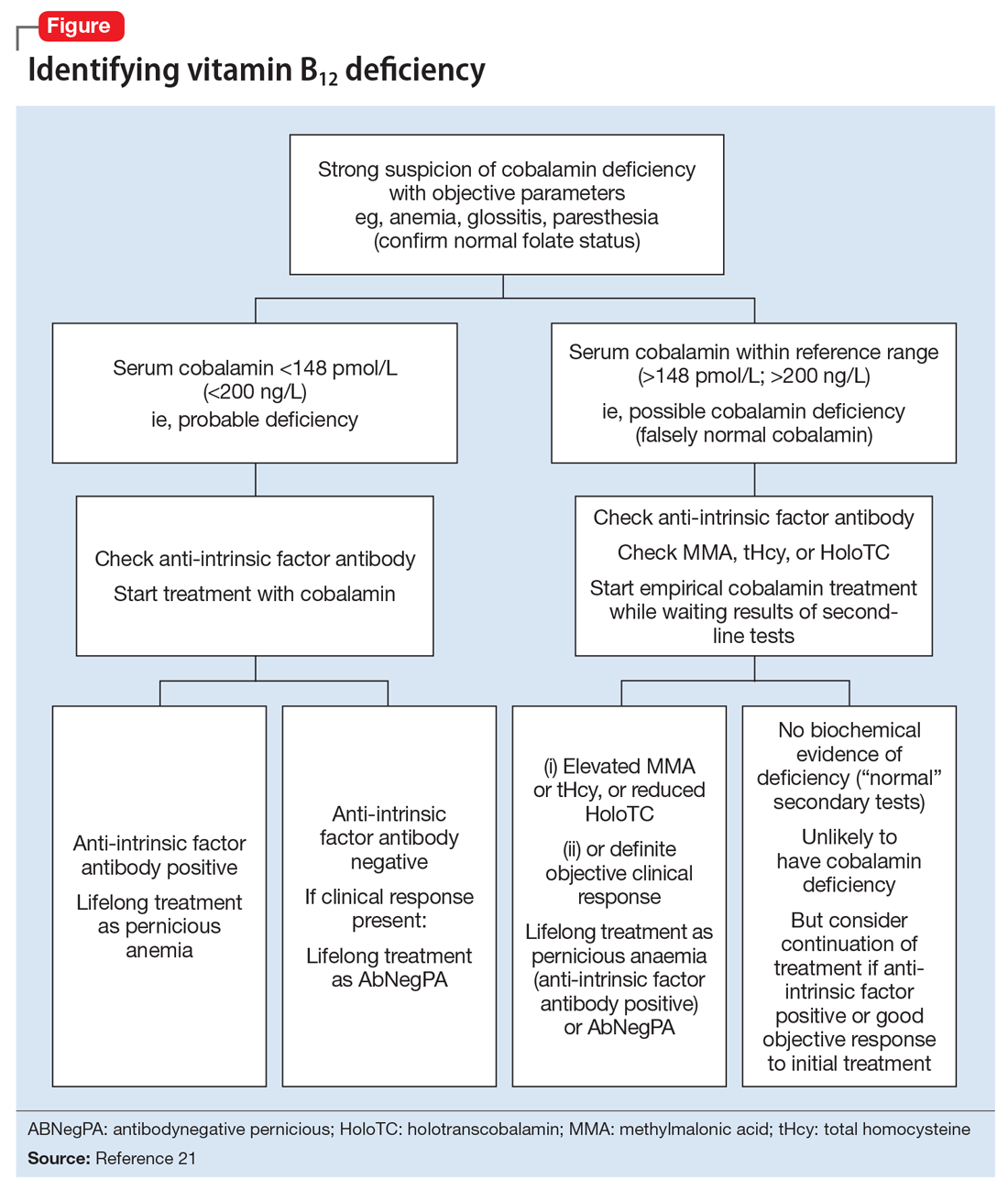

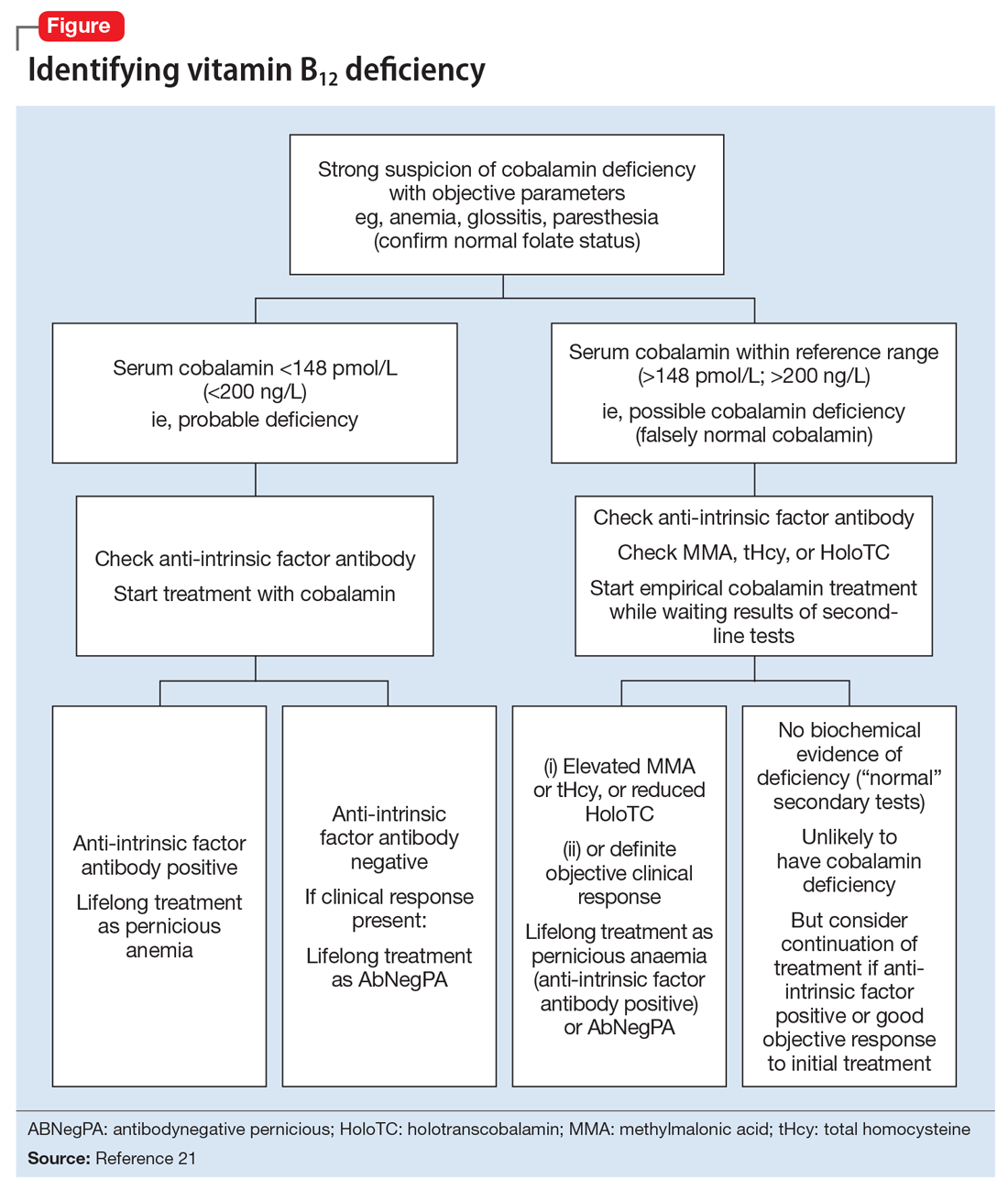

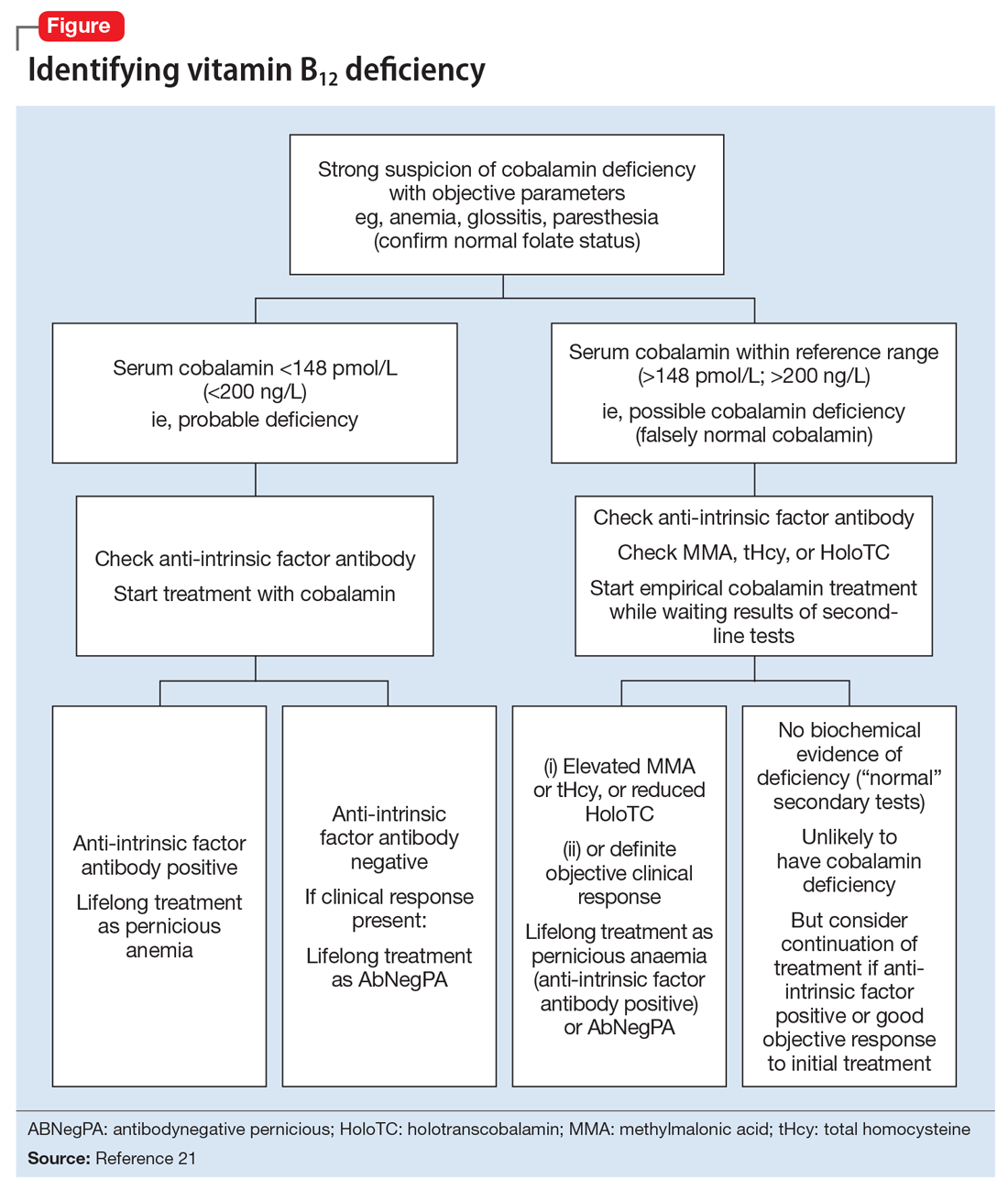

Vitamin B12-responsive psychosis has been reported as the sole manifestation of illness, without associated neurologic or hematologic symptoms, in only a few case reports. Vitamin B12 levels in these cases ranged from 75 to 236 pg/mL (reference range, 160 to 950 pg/mL).18-20 In all of these cases, the vitamin B12 deficiency was traced to dietary causes. The clinical evaluation of suspected vitamin B12 deficiency is outlined in the Figure.21 Mr. M had used Cannabis recreationally for a long time, and his Cannabis use acutely escalated with use of N2O. Long-term use of Cannabis alone is a risk factor for psychotic illness.22 Combined abuse of Cannabis and N2O has been reported to provoke psychotic illness. In a case report of a 22-year-old male who was treated for paranoid delusions, using Cannabis and 100 cartridges of N2O daily was associated with low vitamin B12 and elevated homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels.23

Cannabis use may have played a role in Mr. M’s escalating N2O use. In a study comparing 9 active Cannabis users with 9 non-using controls, users rated the subjective effects of N2O as more intense than non-users.24 In our patient’s case, Cannabis may have played a role in both sustaining his escalating N2O abuse and potentiating its psychotomimetic effects.

It also is possible that Mr. M may have been “self-medicating” his grief with N2O. In a recent placebo-controlled crossover trial of 20 patients with treatment-resistant depression, Nagele et al25 found a significant rapid and week-long antidepressant effect of subanesthetic N2O use. A model involving NMDA receptor activation has been proposed.25,26 Zorumski et al26 further reviewed possible antidepressant mechanisms of N2O. They compared N2O with ketamine as an NMDA receptor antagonist, but also noted its distinct effects on glutaminergic and GABAergic neurotransmitter systems as well as other receptors and channels.26 However, illicit use of N2O poses toxicity dangers and has no current indication for psychiatric treatment.

TREATMENT Supplementation

Mr. M is diagnosed with substance-induced psychotic disorder. His symptoms were precipitated by an acute increase in N2O use, which has been shown to cause vitamin B12 deficiency, which we consider was likely a primary contributor to his presentation. Other potential contributing factors are premorbid hyperthymic temperament, a possible propensity to psychotic thinking under stress, the sudden death of his wife, acute grief, the potentiating role of Cannabis, dehydration, and general malnutrition. The death of a loved one is associated with an increased risk of developing substance use disorders.27

During a 15-day psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. M is given olanzapine, increased to 15 mg/d and oral vitamin B12, 1,000 mcg/d for 4 days, then IM cyanocobalamin for 7 days. Mr. M’s symptoms steadily improve, with normalization of sleep and near-total resolution of delusions. On hospital Day 14, his vitamin B12 levels are within normal limits (844 pg/mL). At discharge, Mr. M shows residual mild grandiosity, with limited insight into his illness and what caused it, but frank delusional ideation has clearly receded. He still shows some signs of grief. Mr. M is advised to stop using Cannabis and N2O and about the potential consequences of continued use.

The authors’ observations

For patients with vitamin B12 deficiency, guidelines from the National Health Service in the United Kingdom and the British Society for Haematology recommend treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, 3 times weekly, for 2 weeks.21,28 For patients with neurologic symptoms, the British National Foundation recommends treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, on alternative days until there is no further improvement.21

This case is a reminder for clinicians to screen for inhalant use, specifically N2O, which can precipitate vitamin B12 deficiency with psychiatric symptoms as the only presenting concern. Clinicians should consider measuring vitamin B12 levels in psychiatric patients at risk of deficiency of this nutrient, including older adults, vegetarians, and those with alimentary disorders.29,30 Dietary sources of vitamin B12 include meat, milk, egg, fish, and shellfish.31 The body can store a total of 2 to 5 mg of vitamin B12; thus, it takes 2 to 5 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from malabsorption and can take as long as 20 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from vegetarianism.32 However, by chemically inactivating vitamin B12, N2O causes a rapid functional deficiency, as was seen in our patient.

OUTCOME Improved insight

At a 1-week follow-up appointment with a psychiatrist, Mr. M has no evident psychotic symptoms. He reports that he has not used Cannabis or N2O, and he discontinues olanzapine following this visit. Two weeks later, Mr. M shows no psychotic or affective symptoms other than grief, which is appropriately expressed. His insight has improved. He commits to not using Cannabis, N2O, or any other illicit substances. Mr. M is referred back to his long-standing primary care provider with the understanding that if any psychiatric symptoms recur he will see a psychiatrist again.

1. Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(2):187-194.

2. Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26)1720-1728.

3. Herres J, Chudnofsky CR, Manur R, et al. The use of inhaled nitrous oxide for analgesia in adult ED patients: a pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(2):269-273.

4. Aboumarzouk OM, Agarwal T, Syed Nong Chek SA, et al. Nitrous oxide for colonoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD008506.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug facts: inhalants. http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/inhalants. Updated February 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

6. SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2012 and 2013: Table 1.88C. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs2013.pdf. Published September 4, 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

7. Brouette T, Anton R. Clinical review of inhalants. Am J Addict. 2001;10(1):79-94.

8. Emmanouil DE, Quock RM. Advances in understanding the actions of nitrous oxide. Anesth Prog. 2007;54(1):9-18.

9. Garakani A, Jaffe RJ, Savla D, et al. Neurologic, psychiatric, and other medical manifestations of nitrous oxide abuse: a systematic review of the case literature. Am J Addict. 2016;25(5):358-369.

10. Hathout L, El-Saden S. Nitrous oxide-induced B12 deficiency myelopathy: perspectives on the clinical biochemistry of vitamin B12. J Neurol Sci. 2011;301(1-2):1-8.

11. van Tonder SV, Ruck A, van der Westhuyzen J, et al. Dissociation of methionine synthetase (EC 2.1.1.13) activity and impairment of DNA synthesis in fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) with nitrous oxide-induced vitamin B12 deficiency. Br J Nutr. 1986;55(1):187-192.

12. Schrier SL, Mentzer WC, Tirnauer JS. Diagnosis and treatment of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-vitamin-b12-and-folate-deficiency. Updated September 30, 2011. Accessed September 8, 2015.

13. Sethi NK, Mullin P, Torgovnick J, et al. Nitrous oxide “whippit” abuse presenting with cobalamin responsive psychosis. J Med Toxicol. 2006;2(2):71-74.

14. Cousaert C, Heylens G, Audenaert K. Laughing gas abuse is no joke. An overview of the implications for psychiatric practice. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(7):859-862.

15. Brodsky L, Zuniga J. Nitrous oxide: a psychotogenic agent. Compr Psychiatry. 1975;16(2):185-188.

16. Wong SL, Harrison R, Mattman A, et al. Nitrous oxide (N2O)-induced acute psychosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2014;41(5):672-674.

17. Smith AD. Megaloblastic madness. Br Med J. 1960;2(5216):1840-1845.

18. Masalha R, Chudakov B, Muhamad M, et al. Cobalamin-responsive psychosis as the sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Isr Med Associ J. 2001;3(9):701-703.

19. Kuo SC, Yeh SB, Yeh YW, et al. Schizophrenia-like psychotic episode precipitated by cobalamin deficiency. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):586-588.

20. Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency masquerading as clozapine-resistant psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):E34-E35.

21. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513.

22. Moore THM, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370:319-328.

23. Garakani A, Welch AK, Jaffe RJ, et al. Psychosis and low cyanocobalamin in a patient abusing nitrous oxide and cannabis. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):715-719.

24. Yajnik S, Thapar P, Lichtor JL, et al. Effects of marijuana history on the subjective, psychomotor, and reinforcing effects of nitrous oxide in human. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;36(3):227-236.

25. Nagele P, Duma A, Kopec M, et al. Nitrous oxide for treatment-resistant major depression: a proof-of-concept trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(1):10-18.

26. Zorumski CF, Nagele P, Mennerick S, et al. Treatment-resistant major depression: rationale for NMDA receptors as targets and nitrous oxide as therapy. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:172.

27. Shear MK. Clinical practice. Complicated grief. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):153-160.

28. Knechtli CJC, Crowe JN. Guidelines for the investigation & management of vitamin B12 deficiency. Royal United Hospital Bath, National Health Service. http://www.ruh.nhs.uk/For_Clinicians/departments_ruh/Pathology/documents/haematology/B12_-_advice_on_investigation_management.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2016.

29. Jayaram N, Rao MG, Narashima A, et al. Vitamin B12 levels and psychiatric symptomatology: a case series. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):150-152.

30. Marks PW, Zukerberg LR. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 30-2004. A 37-year-old woman with paresthesias of the arms and legs. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1333-1341.

31. Watanabe F. Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailablility. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2007;232(10):1266-1274.

32. Green R, Kinsella LJ. Current concepts in the diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1435-1440.

CASE Grieving, delusional

Mr. M, age 51, is brought to the emergency department (ED) because of new-onset delusions and decreased self-care over the last 2 weeks following the sudden death of his wife. He has become expansive and grandiose, with pressured speech, increased energy, and markedly reduced sleep. Mr. M is preoccupied with the idea that he is “the first to survive a human reboot process” and says that his and his wife’s bodies and brains had been “split apart.” Mr. M has limited his food and fluid intake and lost 15 lb within the past 2 to 3 weeks.

Mr. M has no history of any affective, psychotic, or other major mental disorders or treatment. He reports that he has regularly used Cannabis over the last 10 years, and a few years ago, he started occasionally using nitrous oxide (N2O). He says that in the week following his wife’s death, he used N2O almost daily and in copious amounts. In an attempt to “self-anesthetize” himself after his wife’s funeral, he isolated himself in his bedroom and used escalating amounts of Cannabis and N2O, while continually working on a book about their life together.

At first, Mr. M shows little emotion and describes his situation as “interesting and fascinating.” He mentions that he thinks he might have been “psychotic” the week after his wife’s death, but he shows no sustained insight and immediately relapses into psychotic thinking. Over several hours in the ED, he is tearful and sad about his wife’s death. Mr. M recalls a similar experience of grief after his mother died when he was a teenager, but at that time he did not abuse substances or have psychotic symptoms. He is fully alert, fully oriented, and has no significant deficits of attention or memory.

[polldaddy:9859135]

The authors’ observations

Grief was a precipitating event, but by itself grief cannot explain psychosis. Psychotic depression is a possibility, but Mr. M’s psychotic features are incongruent with his mood. Mania would be a diagnosis of exclusion. Mr. M had no prior history of major affective illness. Mr. M was abusing Cannabis, which might independently contribute to psychosis1; however, he had been using it recreationally for 10 years without psychiatric problems. N2O, however, can cause symptoms consistent with Mr. M’s presentation.

[polldaddy:9859140]

EVALUATION Laboratory tests

Mr. M’s physical examination is notable only for an elevated blood pressure of 196/120 mm Hg. Neurologic examination is normal. Toxicology is positive for cannabinoids and negative for amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine. Chemistries are normal except for a potassium of 3.4 mEq/L (reference range, 3.7 to 5.2 mEq/L) and a blood urine nitrogen of 25 mg/dL (reference range, 6 to 20 mg/dL), which are consistent with reduced food and fluid intake. Mr. M shows no signs of anemia. Hematocrit is 42% and mean corpuscular volume is 90 fL. Syphilis screen is negative; a head CT scan is unremarkable.

The authors’ observations

N2O, also known as “laughing gas,” is routinely used by dentists and pediatric anesthesiologists, and has other medical uses. Some studies have examined an adjunctive use of N2O for pain control in the ED and during colonoscopies.3,4

In the 2013 U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 16% of respondents reported lifetime illicit use of N2O.5,6 It is readily available in tanks used in medicine and industry and in small dispensers called “whippits” that can be legally purchased. Acute effects of N2O include euphoric mood, numbness, feeling of warmth, dizziness, and auditory hallucinations.7 The anesthetic effects of N2O are linked to endogenous release of opiates, and recent research links its anxiolytic activity to the facilitation of GABAergic inhibitory and N-methyl-

Beginning with a 1960 report of a series of patients with “megaloblastic madness,”17 there have been calls for increased awareness of the potential for vitamin B12 deficiency–induced psychiatric disorders, even in the absence of other hematologic or neurologic sequelae that would alert clinicians of the deficiency. In a case series of 141 patients with a broad array of neurologic and psychiatric symptoms associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, 40 (28%) patients had no anemia or macrocytosis.2

Vitamin B12-responsive psychosis has been reported as the sole manifestation of illness, without associated neurologic or hematologic symptoms, in only a few case reports. Vitamin B12 levels in these cases ranged from 75 to 236 pg/mL (reference range, 160 to 950 pg/mL).18-20 In all of these cases, the vitamin B12 deficiency was traced to dietary causes. The clinical evaluation of suspected vitamin B12 deficiency is outlined in the Figure.21 Mr. M had used Cannabis recreationally for a long time, and his Cannabis use acutely escalated with use of N2O. Long-term use of Cannabis alone is a risk factor for psychotic illness.22 Combined abuse of Cannabis and N2O has been reported to provoke psychotic illness. In a case report of a 22-year-old male who was treated for paranoid delusions, using Cannabis and 100 cartridges of N2O daily was associated with low vitamin B12 and elevated homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels.23

Cannabis use may have played a role in Mr. M’s escalating N2O use. In a study comparing 9 active Cannabis users with 9 non-using controls, users rated the subjective effects of N2O as more intense than non-users.24 In our patient’s case, Cannabis may have played a role in both sustaining his escalating N2O abuse and potentiating its psychotomimetic effects.

It also is possible that Mr. M may have been “self-medicating” his grief with N2O. In a recent placebo-controlled crossover trial of 20 patients with treatment-resistant depression, Nagele et al25 found a significant rapid and week-long antidepressant effect of subanesthetic N2O use. A model involving NMDA receptor activation has been proposed.25,26 Zorumski et al26 further reviewed possible antidepressant mechanisms of N2O. They compared N2O with ketamine as an NMDA receptor antagonist, but also noted its distinct effects on glutaminergic and GABAergic neurotransmitter systems as well as other receptors and channels.26 However, illicit use of N2O poses toxicity dangers and has no current indication for psychiatric treatment.

TREATMENT Supplementation

Mr. M is diagnosed with substance-induced psychotic disorder. His symptoms were precipitated by an acute increase in N2O use, which has been shown to cause vitamin B12 deficiency, which we consider was likely a primary contributor to his presentation. Other potential contributing factors are premorbid hyperthymic temperament, a possible propensity to psychotic thinking under stress, the sudden death of his wife, acute grief, the potentiating role of Cannabis, dehydration, and general malnutrition. The death of a loved one is associated with an increased risk of developing substance use disorders.27

During a 15-day psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. M is given olanzapine, increased to 15 mg/d and oral vitamin B12, 1,000 mcg/d for 4 days, then IM cyanocobalamin for 7 days. Mr. M’s symptoms steadily improve, with normalization of sleep and near-total resolution of delusions. On hospital Day 14, his vitamin B12 levels are within normal limits (844 pg/mL). At discharge, Mr. M shows residual mild grandiosity, with limited insight into his illness and what caused it, but frank delusional ideation has clearly receded. He still shows some signs of grief. Mr. M is advised to stop using Cannabis and N2O and about the potential consequences of continued use.

The authors’ observations

For patients with vitamin B12 deficiency, guidelines from the National Health Service in the United Kingdom and the British Society for Haematology recommend treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, 3 times weekly, for 2 weeks.21,28 For patients with neurologic symptoms, the British National Foundation recommends treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, on alternative days until there is no further improvement.21

This case is a reminder for clinicians to screen for inhalant use, specifically N2O, which can precipitate vitamin B12 deficiency with psychiatric symptoms as the only presenting concern. Clinicians should consider measuring vitamin B12 levels in psychiatric patients at risk of deficiency of this nutrient, including older adults, vegetarians, and those with alimentary disorders.29,30 Dietary sources of vitamin B12 include meat, milk, egg, fish, and shellfish.31 The body can store a total of 2 to 5 mg of vitamin B12; thus, it takes 2 to 5 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from malabsorption and can take as long as 20 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from vegetarianism.32 However, by chemically inactivating vitamin B12, N2O causes a rapid functional deficiency, as was seen in our patient.

OUTCOME Improved insight

At a 1-week follow-up appointment with a psychiatrist, Mr. M has no evident psychotic symptoms. He reports that he has not used Cannabis or N2O, and he discontinues olanzapine following this visit. Two weeks later, Mr. M shows no psychotic or affective symptoms other than grief, which is appropriately expressed. His insight has improved. He commits to not using Cannabis, N2O, or any other illicit substances. Mr. M is referred back to his long-standing primary care provider with the understanding that if any psychiatric symptoms recur he will see a psychiatrist again.

CASE Grieving, delusional

Mr. M, age 51, is brought to the emergency department (ED) because of new-onset delusions and decreased self-care over the last 2 weeks following the sudden death of his wife. He has become expansive and grandiose, with pressured speech, increased energy, and markedly reduced sleep. Mr. M is preoccupied with the idea that he is “the first to survive a human reboot process” and says that his and his wife’s bodies and brains had been “split apart.” Mr. M has limited his food and fluid intake and lost 15 lb within the past 2 to 3 weeks.

Mr. M has no history of any affective, psychotic, or other major mental disorders or treatment. He reports that he has regularly used Cannabis over the last 10 years, and a few years ago, he started occasionally using nitrous oxide (N2O). He says that in the week following his wife’s death, he used N2O almost daily and in copious amounts. In an attempt to “self-anesthetize” himself after his wife’s funeral, he isolated himself in his bedroom and used escalating amounts of Cannabis and N2O, while continually working on a book about their life together.

At first, Mr. M shows little emotion and describes his situation as “interesting and fascinating.” He mentions that he thinks he might have been “psychotic” the week after his wife’s death, but he shows no sustained insight and immediately relapses into psychotic thinking. Over several hours in the ED, he is tearful and sad about his wife’s death. Mr. M recalls a similar experience of grief after his mother died when he was a teenager, but at that time he did not abuse substances or have psychotic symptoms. He is fully alert, fully oriented, and has no significant deficits of attention or memory.

[polldaddy:9859135]

The authors’ observations

Grief was a precipitating event, but by itself grief cannot explain psychosis. Psychotic depression is a possibility, but Mr. M’s psychotic features are incongruent with his mood. Mania would be a diagnosis of exclusion. Mr. M had no prior history of major affective illness. Mr. M was abusing Cannabis, which might independently contribute to psychosis1; however, he had been using it recreationally for 10 years without psychiatric problems. N2O, however, can cause symptoms consistent with Mr. M’s presentation.

[polldaddy:9859140]

EVALUATION Laboratory tests

Mr. M’s physical examination is notable only for an elevated blood pressure of 196/120 mm Hg. Neurologic examination is normal. Toxicology is positive for cannabinoids and negative for amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine. Chemistries are normal except for a potassium of 3.4 mEq/L (reference range, 3.7 to 5.2 mEq/L) and a blood urine nitrogen of 25 mg/dL (reference range, 6 to 20 mg/dL), which are consistent with reduced food and fluid intake. Mr. M shows no signs of anemia. Hematocrit is 42% and mean corpuscular volume is 90 fL. Syphilis screen is negative; a head CT scan is unremarkable.

The authors’ observations

N2O, also known as “laughing gas,” is routinely used by dentists and pediatric anesthesiologists, and has other medical uses. Some studies have examined an adjunctive use of N2O for pain control in the ED and during colonoscopies.3,4

In the 2013 U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 16% of respondents reported lifetime illicit use of N2O.5,6 It is readily available in tanks used in medicine and industry and in small dispensers called “whippits” that can be legally purchased. Acute effects of N2O include euphoric mood, numbness, feeling of warmth, dizziness, and auditory hallucinations.7 The anesthetic effects of N2O are linked to endogenous release of opiates, and recent research links its anxiolytic activity to the facilitation of GABAergic inhibitory and N-methyl-

Beginning with a 1960 report of a series of patients with “megaloblastic madness,”17 there have been calls for increased awareness of the potential for vitamin B12 deficiency–induced psychiatric disorders, even in the absence of other hematologic or neurologic sequelae that would alert clinicians of the deficiency. In a case series of 141 patients with a broad array of neurologic and psychiatric symptoms associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, 40 (28%) patients had no anemia or macrocytosis.2

Vitamin B12-responsive psychosis has been reported as the sole manifestation of illness, without associated neurologic or hematologic symptoms, in only a few case reports. Vitamin B12 levels in these cases ranged from 75 to 236 pg/mL (reference range, 160 to 950 pg/mL).18-20 In all of these cases, the vitamin B12 deficiency was traced to dietary causes. The clinical evaluation of suspected vitamin B12 deficiency is outlined in the Figure.21 Mr. M had used Cannabis recreationally for a long time, and his Cannabis use acutely escalated with use of N2O. Long-term use of Cannabis alone is a risk factor for psychotic illness.22 Combined abuse of Cannabis and N2O has been reported to provoke psychotic illness. In a case report of a 22-year-old male who was treated for paranoid delusions, using Cannabis and 100 cartridges of N2O daily was associated with low vitamin B12 and elevated homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels.23

Cannabis use may have played a role in Mr. M’s escalating N2O use. In a study comparing 9 active Cannabis users with 9 non-using controls, users rated the subjective effects of N2O as more intense than non-users.24 In our patient’s case, Cannabis may have played a role in both sustaining his escalating N2O abuse and potentiating its psychotomimetic effects.

It also is possible that Mr. M may have been “self-medicating” his grief with N2O. In a recent placebo-controlled crossover trial of 20 patients with treatment-resistant depression, Nagele et al25 found a significant rapid and week-long antidepressant effect of subanesthetic N2O use. A model involving NMDA receptor activation has been proposed.25,26 Zorumski et al26 further reviewed possible antidepressant mechanisms of N2O. They compared N2O with ketamine as an NMDA receptor antagonist, but also noted its distinct effects on glutaminergic and GABAergic neurotransmitter systems as well as other receptors and channels.26 However, illicit use of N2O poses toxicity dangers and has no current indication for psychiatric treatment.

TREATMENT Supplementation

Mr. M is diagnosed with substance-induced psychotic disorder. His symptoms were precipitated by an acute increase in N2O use, which has been shown to cause vitamin B12 deficiency, which we consider was likely a primary contributor to his presentation. Other potential contributing factors are premorbid hyperthymic temperament, a possible propensity to psychotic thinking under stress, the sudden death of his wife, acute grief, the potentiating role of Cannabis, dehydration, and general malnutrition. The death of a loved one is associated with an increased risk of developing substance use disorders.27

During a 15-day psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. M is given olanzapine, increased to 15 mg/d and oral vitamin B12, 1,000 mcg/d for 4 days, then IM cyanocobalamin for 7 days. Mr. M’s symptoms steadily improve, with normalization of sleep and near-total resolution of delusions. On hospital Day 14, his vitamin B12 levels are within normal limits (844 pg/mL). At discharge, Mr. M shows residual mild grandiosity, with limited insight into his illness and what caused it, but frank delusional ideation has clearly receded. He still shows some signs of grief. Mr. M is advised to stop using Cannabis and N2O and about the potential consequences of continued use.

The authors’ observations

For patients with vitamin B12 deficiency, guidelines from the National Health Service in the United Kingdom and the British Society for Haematology recommend treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, 3 times weekly, for 2 weeks.21,28 For patients with neurologic symptoms, the British National Foundation recommends treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, on alternative days until there is no further improvement.21

This case is a reminder for clinicians to screen for inhalant use, specifically N2O, which can precipitate vitamin B12 deficiency with psychiatric symptoms as the only presenting concern. Clinicians should consider measuring vitamin B12 levels in psychiatric patients at risk of deficiency of this nutrient, including older adults, vegetarians, and those with alimentary disorders.29,30 Dietary sources of vitamin B12 include meat, milk, egg, fish, and shellfish.31 The body can store a total of 2 to 5 mg of vitamin B12; thus, it takes 2 to 5 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from malabsorption and can take as long as 20 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from vegetarianism.32 However, by chemically inactivating vitamin B12, N2O causes a rapid functional deficiency, as was seen in our patient.

OUTCOME Improved insight

At a 1-week follow-up appointment with a psychiatrist, Mr. M has no evident psychotic symptoms. He reports that he has not used Cannabis or N2O, and he discontinues olanzapine following this visit. Two weeks later, Mr. M shows no psychotic or affective symptoms other than grief, which is appropriately expressed. His insight has improved. He commits to not using Cannabis, N2O, or any other illicit substances. Mr. M is referred back to his long-standing primary care provider with the understanding that if any psychiatric symptoms recur he will see a psychiatrist again.

1. Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(2):187-194.

2. Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26)1720-1728.

3. Herres J, Chudnofsky CR, Manur R, et al. The use of inhaled nitrous oxide for analgesia in adult ED patients: a pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(2):269-273.

4. Aboumarzouk OM, Agarwal T, Syed Nong Chek SA, et al. Nitrous oxide for colonoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD008506.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug facts: inhalants. http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/inhalants. Updated February 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

6. SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2012 and 2013: Table 1.88C. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs2013.pdf. Published September 4, 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

7. Brouette T, Anton R. Clinical review of inhalants. Am J Addict. 2001;10(1):79-94.

8. Emmanouil DE, Quock RM. Advances in understanding the actions of nitrous oxide. Anesth Prog. 2007;54(1):9-18.

9. Garakani A, Jaffe RJ, Savla D, et al. Neurologic, psychiatric, and other medical manifestations of nitrous oxide abuse: a systematic review of the case literature. Am J Addict. 2016;25(5):358-369.

10. Hathout L, El-Saden S. Nitrous oxide-induced B12 deficiency myelopathy: perspectives on the clinical biochemistry of vitamin B12. J Neurol Sci. 2011;301(1-2):1-8.

11. van Tonder SV, Ruck A, van der Westhuyzen J, et al. Dissociation of methionine synthetase (EC 2.1.1.13) activity and impairment of DNA synthesis in fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) with nitrous oxide-induced vitamin B12 deficiency. Br J Nutr. 1986;55(1):187-192.

12. Schrier SL, Mentzer WC, Tirnauer JS. Diagnosis and treatment of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-vitamin-b12-and-folate-deficiency. Updated September 30, 2011. Accessed September 8, 2015.

13. Sethi NK, Mullin P, Torgovnick J, et al. Nitrous oxide “whippit” abuse presenting with cobalamin responsive psychosis. J Med Toxicol. 2006;2(2):71-74.

14. Cousaert C, Heylens G, Audenaert K. Laughing gas abuse is no joke. An overview of the implications for psychiatric practice. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(7):859-862.

15. Brodsky L, Zuniga J. Nitrous oxide: a psychotogenic agent. Compr Psychiatry. 1975;16(2):185-188.

16. Wong SL, Harrison R, Mattman A, et al. Nitrous oxide (N2O)-induced acute psychosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2014;41(5):672-674.

17. Smith AD. Megaloblastic madness. Br Med J. 1960;2(5216):1840-1845.

18. Masalha R, Chudakov B, Muhamad M, et al. Cobalamin-responsive psychosis as the sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Isr Med Associ J. 2001;3(9):701-703.

19. Kuo SC, Yeh SB, Yeh YW, et al. Schizophrenia-like psychotic episode precipitated by cobalamin deficiency. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):586-588.

20. Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency masquerading as clozapine-resistant psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):E34-E35.

21. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513.

22. Moore THM, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370:319-328.

23. Garakani A, Welch AK, Jaffe RJ, et al. Psychosis and low cyanocobalamin in a patient abusing nitrous oxide and cannabis. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):715-719.

24. Yajnik S, Thapar P, Lichtor JL, et al. Effects of marijuana history on the subjective, psychomotor, and reinforcing effects of nitrous oxide in human. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;36(3):227-236.

25. Nagele P, Duma A, Kopec M, et al. Nitrous oxide for treatment-resistant major depression: a proof-of-concept trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(1):10-18.

26. Zorumski CF, Nagele P, Mennerick S, et al. Treatment-resistant major depression: rationale for NMDA receptors as targets and nitrous oxide as therapy. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:172.

27. Shear MK. Clinical practice. Complicated grief. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):153-160.

28. Knechtli CJC, Crowe JN. Guidelines for the investigation & management of vitamin B12 deficiency. Royal United Hospital Bath, National Health Service. http://www.ruh.nhs.uk/For_Clinicians/departments_ruh/Pathology/documents/haematology/B12_-_advice_on_investigation_management.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2016.

29. Jayaram N, Rao MG, Narashima A, et al. Vitamin B12 levels and psychiatric symptomatology: a case series. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):150-152.

30. Marks PW, Zukerberg LR. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 30-2004. A 37-year-old woman with paresthesias of the arms and legs. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1333-1341.

31. Watanabe F. Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailablility. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2007;232(10):1266-1274.

32. Green R, Kinsella LJ. Current concepts in the diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1435-1440.

1. Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(2):187-194.

2. Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26)1720-1728.

3. Herres J, Chudnofsky CR, Manur R, et al. The use of inhaled nitrous oxide for analgesia in adult ED patients: a pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(2):269-273.

4. Aboumarzouk OM, Agarwal T, Syed Nong Chek SA, et al. Nitrous oxide for colonoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD008506.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug facts: inhalants. http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/inhalants. Updated February 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

6. SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2012 and 2013: Table 1.88C. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs2013.pdf. Published September 4, 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

7. Brouette T, Anton R. Clinical review of inhalants. Am J Addict. 2001;10(1):79-94.

8. Emmanouil DE, Quock RM. Advances in understanding the actions of nitrous oxide. Anesth Prog. 2007;54(1):9-18.

9. Garakani A, Jaffe RJ, Savla D, et al. Neurologic, psychiatric, and other medical manifestations of nitrous oxide abuse: a systematic review of the case literature. Am J Addict. 2016;25(5):358-369.

10. Hathout L, El-Saden S. Nitrous oxide-induced B12 deficiency myelopathy: perspectives on the clinical biochemistry of vitamin B12. J Neurol Sci. 2011;301(1-2):1-8.

11. van Tonder SV, Ruck A, van der Westhuyzen J, et al. Dissociation of methionine synthetase (EC 2.1.1.13) activity and impairment of DNA synthesis in fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) with nitrous oxide-induced vitamin B12 deficiency. Br J Nutr. 1986;55(1):187-192.

12. Schrier SL, Mentzer WC, Tirnauer JS. Diagnosis and treatment of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-vitamin-b12-and-folate-deficiency. Updated September 30, 2011. Accessed September 8, 2015.

13. Sethi NK, Mullin P, Torgovnick J, et al. Nitrous oxide “whippit” abuse presenting with cobalamin responsive psychosis. J Med Toxicol. 2006;2(2):71-74.

14. Cousaert C, Heylens G, Audenaert K. Laughing gas abuse is no joke. An overview of the implications for psychiatric practice. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(7):859-862.

15. Brodsky L, Zuniga J. Nitrous oxide: a psychotogenic agent. Compr Psychiatry. 1975;16(2):185-188.

16. Wong SL, Harrison R, Mattman A, et al. Nitrous oxide (N2O)-induced acute psychosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2014;41(5):672-674.

17. Smith AD. Megaloblastic madness. Br Med J. 1960;2(5216):1840-1845.

18. Masalha R, Chudakov B, Muhamad M, et al. Cobalamin-responsive psychosis as the sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Isr Med Associ J. 2001;3(9):701-703.

19. Kuo SC, Yeh SB, Yeh YW, et al. Schizophrenia-like psychotic episode precipitated by cobalamin deficiency. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):586-588.

20. Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency masquerading as clozapine-resistant psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):E34-E35.

21. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513.

22. Moore THM, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370:319-328.

23. Garakani A, Welch AK, Jaffe RJ, et al. Psychosis and low cyanocobalamin in a patient abusing nitrous oxide and cannabis. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):715-719.

24. Yajnik S, Thapar P, Lichtor JL, et al. Effects of marijuana history on the subjective, psychomotor, and reinforcing effects of nitrous oxide in human. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;36(3):227-236.

25. Nagele P, Duma A, Kopec M, et al. Nitrous oxide for treatment-resistant major depression: a proof-of-concept trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(1):10-18.

26. Zorumski CF, Nagele P, Mennerick S, et al. Treatment-resistant major depression: rationale for NMDA receptors as targets and nitrous oxide as therapy. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:172.

27. Shear MK. Clinical practice. Complicated grief. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):153-160.

28. Knechtli CJC, Crowe JN. Guidelines for the investigation & management of vitamin B12 deficiency. Royal United Hospital Bath, National Health Service. http://www.ruh.nhs.uk/For_Clinicians/departments_ruh/Pathology/documents/haematology/B12_-_advice_on_investigation_management.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2016.

29. Jayaram N, Rao MG, Narashima A, et al. Vitamin B12 levels and psychiatric symptomatology: a case series. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):150-152.

30. Marks PW, Zukerberg LR. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 30-2004. A 37-year-old woman with paresthesias of the arms and legs. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1333-1341.

31. Watanabe F. Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailablility. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2007;232(10):1266-1274.

32. Green R, Kinsella LJ. Current concepts in the diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1435-1440.