User login

Steatocystomas: Update on Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Management

Steatocystomas: Update on Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Management

Steatocystomas are small sebum-filled cysts that typically manifest in the dermis and originate from sebaceous follicles. Although commonly asymptomatic, these lesions can manifest with pruritus or become infected, predisposing patients to further complications.1 Steatocystomas can manifest as single (steatocystoma simplex [SS]) or numerous (steatocystoma multiplex [SM]) lesions; the lesions also can spontaneously rupture with characteristics that resemble hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)(steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa [SMS]).1,2

Steatocystomas are relatively rare, and there is limited consensus in the published literature on the etiology and management of this condition. In this article, we present a comprehensive review of steatocystomas in the current literature. We highlight important features to consider when making the diagnosis and also offer recommendations for best-practice treatment.

Historical Background

Although not explicitly identified by name, the first documentation of steatocystomas is a case report published in 1873. In this account, the author described a patient who presented with approximately 250 flesh-colored dermal cysts across the body that varied in size.3 In 1899, the term steatocystoma multiple—derived from Greek roots meaning “fatty bag”—was first used.4

In 1982, almost a century later, Brownstein5 reported some of the earliest cases of SS. This solitary subtype is identical to SM on a microscopic level; however, unlike SM, this variant occurs as a single lesion that typically forms in adulthood and in the absence of family history. Other benign adnexal tumors (eg, pilomatricomas, pilar cysts, and sebaceous hyperplasias) also can manifest as either solitary or multiple lesions.

In 1976, McDonald and Reed6 reported the first known cases of patients with both SM and HS. At the time, the co-occurrence of these conditions was viewed as coincidental, but there were postulations of a shared inflammatory process and hereditary link6; it was not until 1982 that the term steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum was coined to describe this variant.7 Although rare, there have been multiple documented instances of SMS since. It has been suggested that the convergence of these conditions may indicate a shared follicular proliferation defect.8 Ongoing investigation is warranted to explain the underlying pathogenesis of this unique variant.

Epidemiology

The available epidemiologic data primarily relate to SM, the most common steatocystoma variant. Nevertheless, SM is a relatively rare condition, and the exact incidence and prevalence remain unknown.8,9 Steatocystomas typically manifest in the first and second decades of life and have been observed in patients of both sexes, with studies demonstrating no notable sex bias.4,9

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Steatocystomas can occur sporadically or may be inherited as an autosomal-dominant condition.4 Typically, SS tends to manifest as an isolated occurrence without any inherent genetic predisposition.5 Alternatively, SM may develop sporadically or be associated with a mutation in the keratin 17 gene (KRT17).4 Steatocystoma multiplex also has been associated with at least 4 different missense mutations, including N92H, R94H, and R94C, located on the long (q) arm of chromosome 17.4,10-12

The keratin 17 gene is responsible for encoding the keratin 17 protein, a type I intermediate filament predominantly synthesized in the basal cells of epithelial tissue. This fibrous structural protein can regulate many processes, including inflammation and cell proliferation, and is found in regions such as the sebaceous glands, hair follicles, and eccrine sweat glands. Overexpression of KRT17 has been suggested in other cutaneous conditions, most notably psoriasis.12 Despite KRT17’s many roles, it remains unclear why SM typically manifests with a myriad of sebum-containing cysts as the primary symptom.12 Continued investigation into the genetic underpinnings of SM and the keratin 17 protein is necessary to further elucidate a more comprehensive understanding of this condition.

Hormonal influences have been suggested as a potential trigger for steatocystoma growth.4,13 This condition is associated with dysfunction of the sebaceous glands, and, correspondingly, the incidence of disease is highest in pubertal patients, in whom androgen levels and sebum production are elevated.4,13,14 Two cases of transgender men taking testosterone therapy presenting with steatocystomas provide additional clinical support for this association.15

Additionally, the use of immunomodulatory agents, such as ustekinumab (anti–interleukin 12/interleukin 23), has been shown to trigger SM. It is predicted that the reduced expression of certain interferons and interleukins may lead to downstream consequences in the keratin 17 pathway and lead to SM lesion formation in genetically susceptible individuals.16 Targeting these potential causes in the future may prove efficacious in the secondary prevention of familial SM manifestation or exacerbations.

Mutations in the KRT17 gene also have been implicated in pachyonychia congenita type 2 (PC-2).4 Marked by extensive systemic hyperkeratosis, PC-2 has been observed to coincide with SM in certain patients.4,5 Interestingly, the location of the KRT17 mutations are identical in both PC-2 and SM.4 Although most individuals with hereditary SM do not exhibit the characteristic features of PC-2, mild nail and dental abnormalities have been observed in some SM cases.4,10 This relationship suggests that SM may be a less severe variant of PC-2 or part of a complex polygenetic spectrum of disease.10 Further research is imperative to determine the exact nature and extent of the relationship between these conditions.

Clinical Manifestations

Steatocystomas are flesh-colored subcutaneous cysts that range in size from less than 3 mm to larger than 3 cm in diameter (Figure). They form within a single pilosebaceous unit and typically display firm attachment due to their origination in the dermis.2,7,17 Steatocystomas generally contain lipid material, and less frequently, keratin and hair shafts, distinguishing them as the only “true” sebaceous cysts.18 Their color can range from flesh-toned to yellow, with reports of occasional dark-blue shades and calcifications.19,20 Steatocystomas can persist indefinitely, and they usually are asymptomatic.

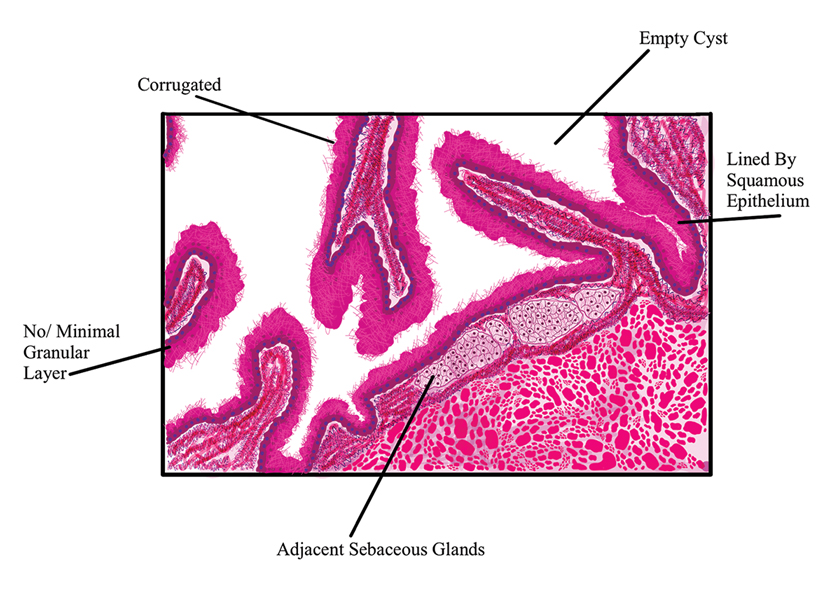

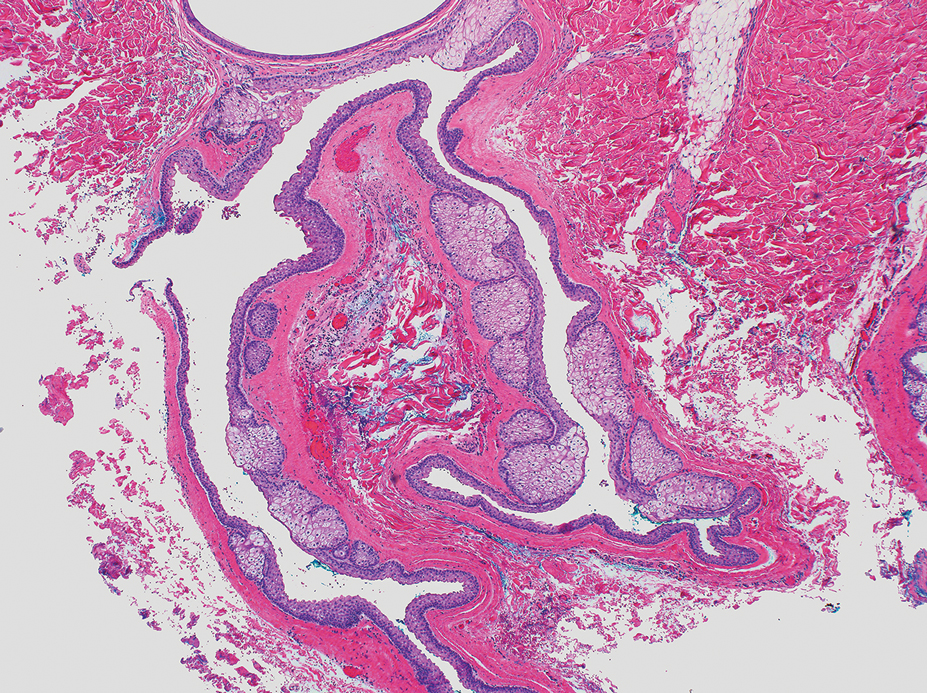

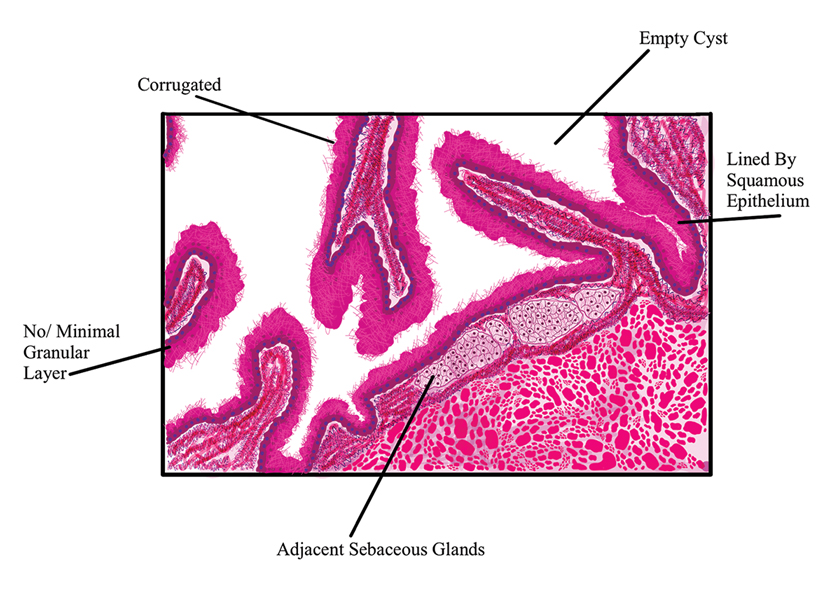

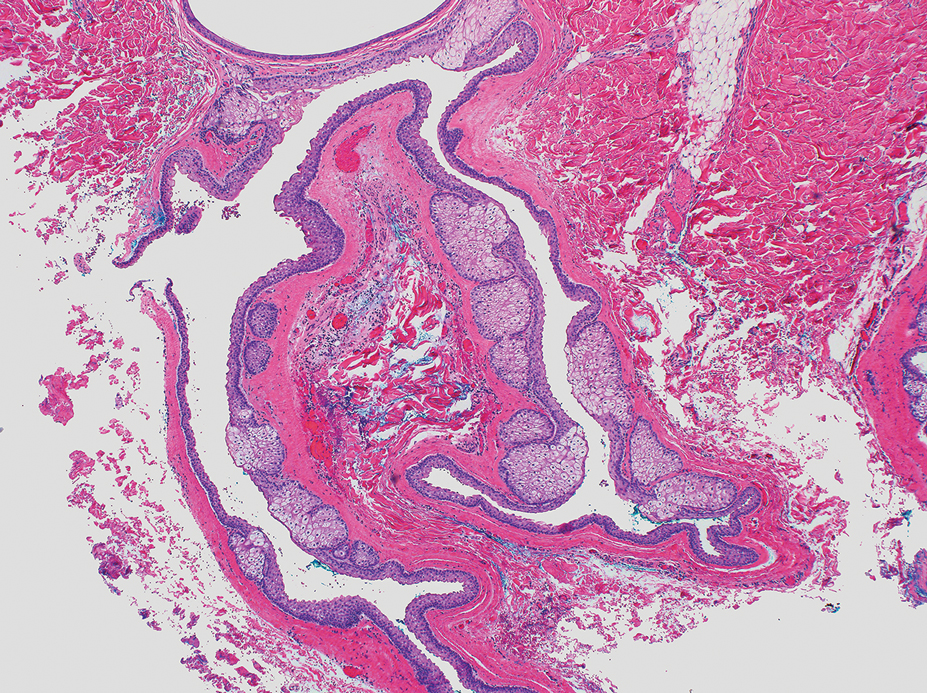

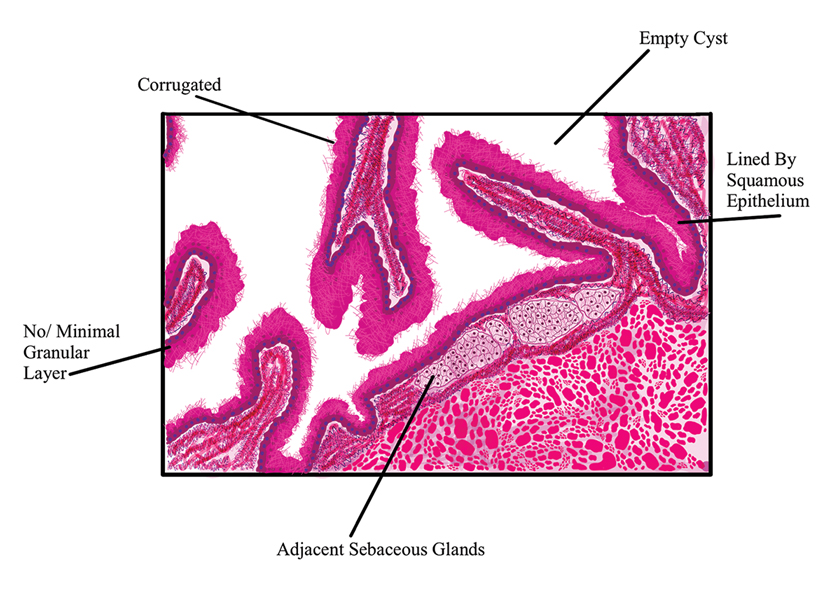

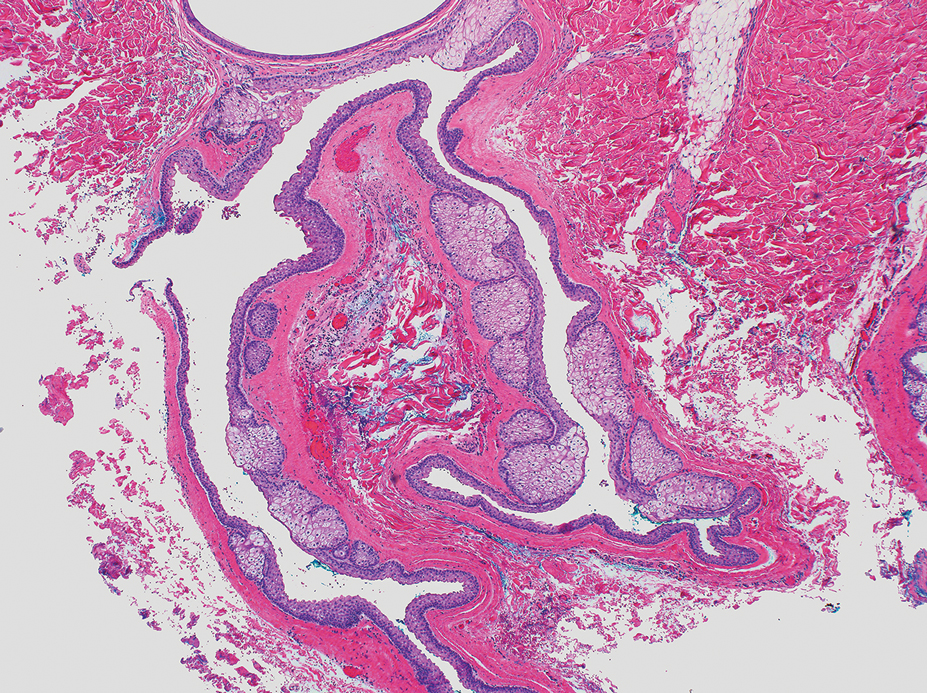

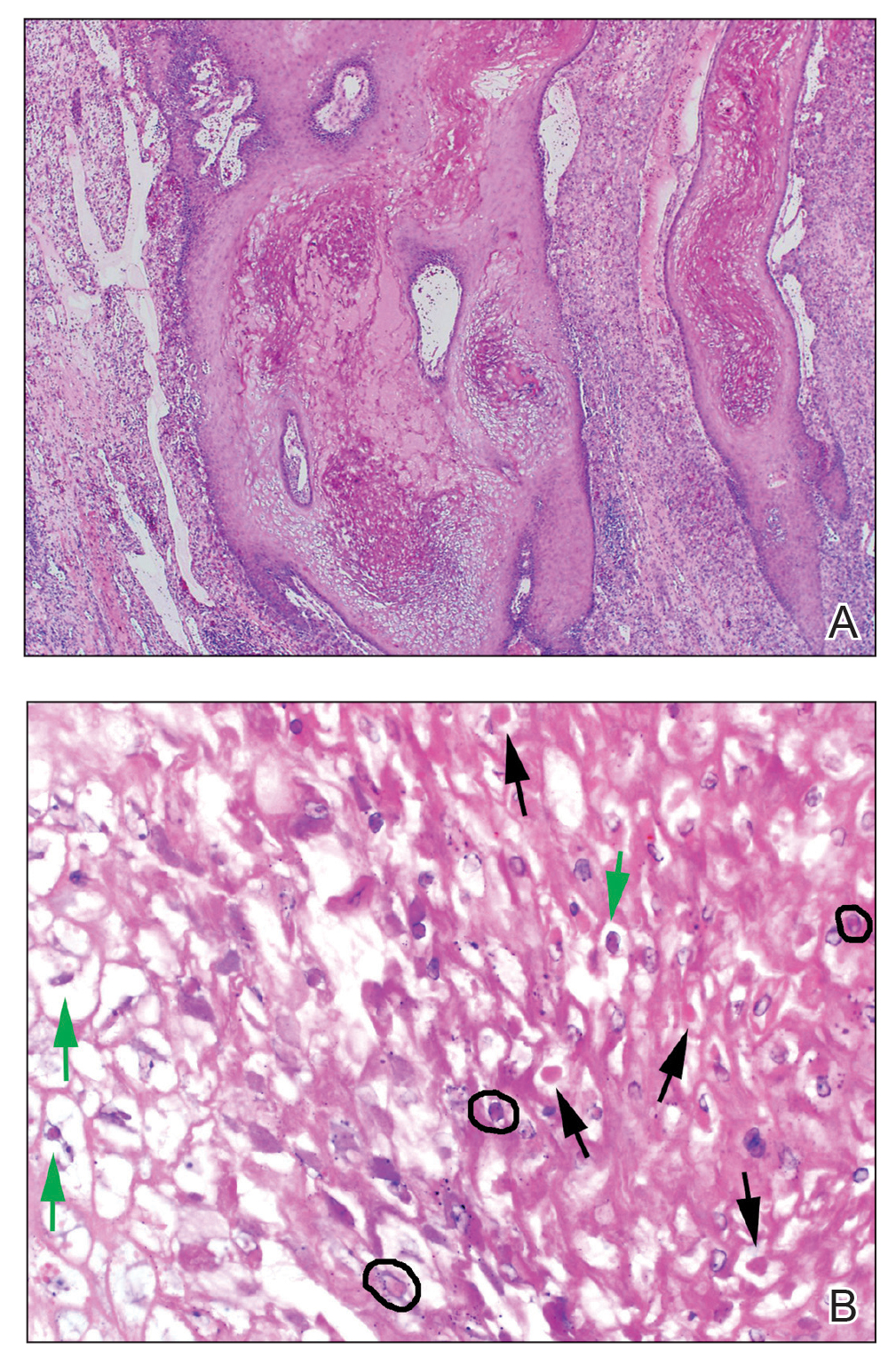

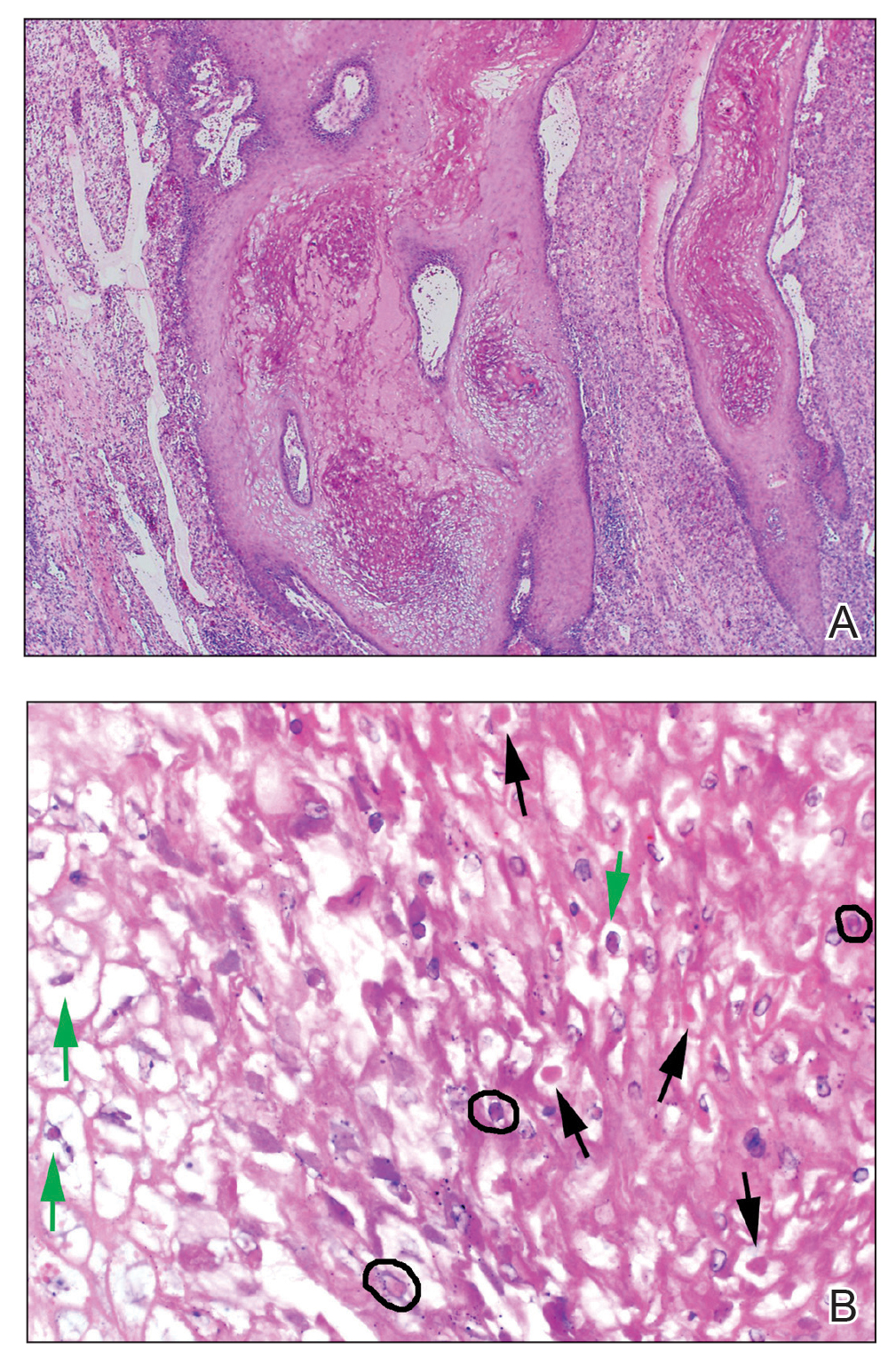

Diagnosis of steatocystoma is confirmed by biopsy.4 Steatocystomas are characterized by a dermal cyst lined by stratified squamous cell epithelium (eFigures 1 and 2).21 Classically they feature flattened sebaceous lobules, multinucleated giant cells, and abortive hair follicles. The lining of these cysts is marked by lymphocytic infiltrate and a dense, wrinkled, eosinophilic keratin cuticle that replaces the granular layer.22 The cyst maintains an epidermal connection through a follicular infundibulum characterized by clumps of keratinocytes, sebocytes, corneocytes, and/or hair follicles.7 Aspirated contents reveal crystalline structures and anucleate squamous cells upon microscopic analysis. That being said, variable histologic findings of steatocystomas have been described.23

Steatocystoma simplex, as the name implies, classifies a single isolated steatocystoma. This subtype exhibits similar histopathologic and clinical features to the other subtypes of steatocystomas. Notably, SS is not associated with a genetic mutation and is not an inherited condition within families.5 Steatocystoma multiplex manifests with many steatocystomas, often distributed widely across the body.3,4 The chest, axillae, and groin are the most common locations; however, these cysts can manifest on the face, back, abdomen, and extremities.4,18-22 Rare occurrences of SM limited to the face, scalp, and distal extremities have been documented.18,21,24,25 Due to the possibility of an autosomal-dominant inheritance, it is advisable to take a comprehensive family history in patients for whom SM is in the differential.17

Steatocystoma multiplex—especially familial variants—has been shown to develop in conjunction with other dermatologic conditions, including eruptive vellus hair (EVH) cysts, persistent infantile milia, and epidermoid/dermoid cysts.26 While some investigators regard these as separate entities due to their varied genetic etiology, it has been suggested that these conditions may be related and that the diagnosis is determined by the location of cyst origin along the sebaceous ducts.26,27 Other dermatologic conditions and lesions that frequently manifest comorbidly with SM include hidrocystomas, syringomas, pilonidal cysts, lichen planus, nodulocystic acne, trichotillomania, trichoblastomas, trichoepithelioma, HS, keratoacanthomas, acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf, and embryonal hair formation. Steatocystoma multiplex, manifesting comorbidly with dental and orofacial malformations (eg, partial noneruption of secondary teeth, natal and defective teeth, and bilateral preauricular sinuses) has been classified as SM natal teeth syndrome.6

Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa is a rare and serious variant of SM characterized by inflammation, cyst rupture, sinus tract formation, and scarring.24 Patients with SMS typically have multiple intact SM cysts, which can aid in differentiation from HS.2,24 Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa is associated with more complications than SS and SM, including cyst perforation, development of purulent and/or foul-smelling discharge, infection, scarring, pain, and overall discomfort.2

Given its rarity and the potential manifestations that overlap with other conditions, steatocystomas easily can be misdiagnosed. In some clinical instances, EVHs may share similar characteristics with SM; however, certain distinguishing features exist, including a central tuft of protruding hairs and different expressed contents, such as the vellus hair shafts, from the cyst’s lumen.28 Furthermore, histologic examination of EVHs reveals epidermoid keratinization of the lining as well as a lack of sebaceous glands within the wall.28,29 Other similar conditions include epidermoid cysts, pilar cysts, lipomas, epidermal inclusion cysts, dermoid cysts, sebaceous hyperplasia, folliculitis, xanthomas, neurofibromatosis, and syringomas.30 Occasionally, SMS can be mistaken for HS or acne conglobata, and SM lesions with a facial distribution can mimic acne vulgaris.1,31 These conditions should be excluded before a diagnosis of SS, SM, or SMS is made.

Importantly, SM is visually indistinguishable from subcutaneous metastasis on physical examination, and there are reports of oncologic conditions (eg, pulmonary adenocarcinoma metastasized to the skin) being mistaken for SS or SM.32 Therefore, a thorough clinical examination, histopathologic analysis, and potential use of other imaging modalities such as ultrasonography (US) are needed to ensure an accurate diagnosis.

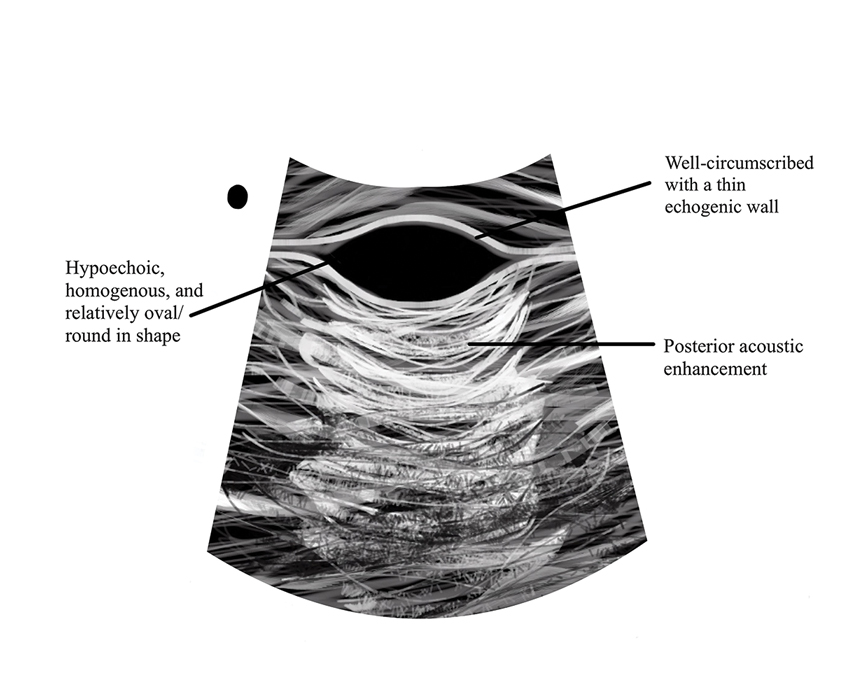

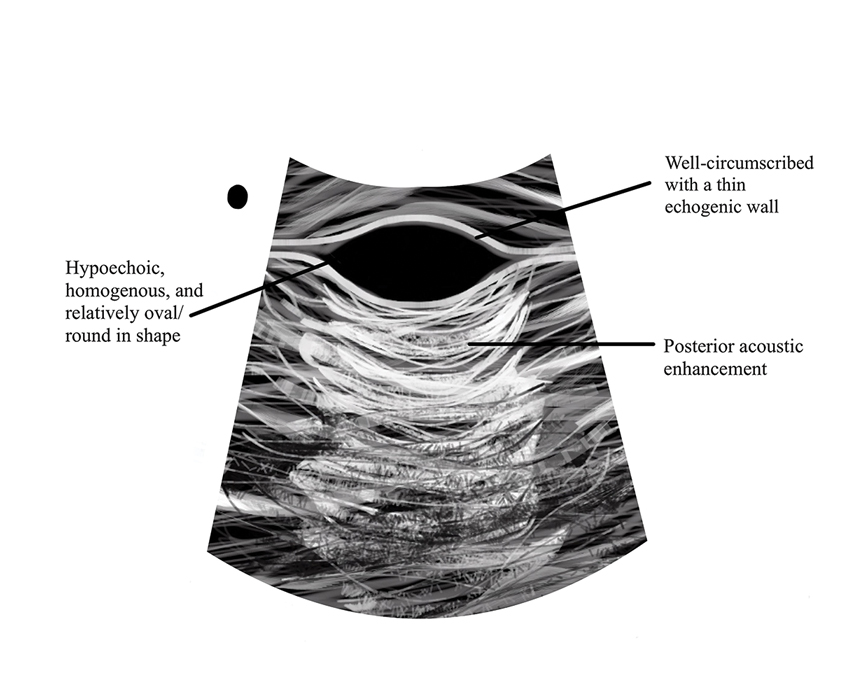

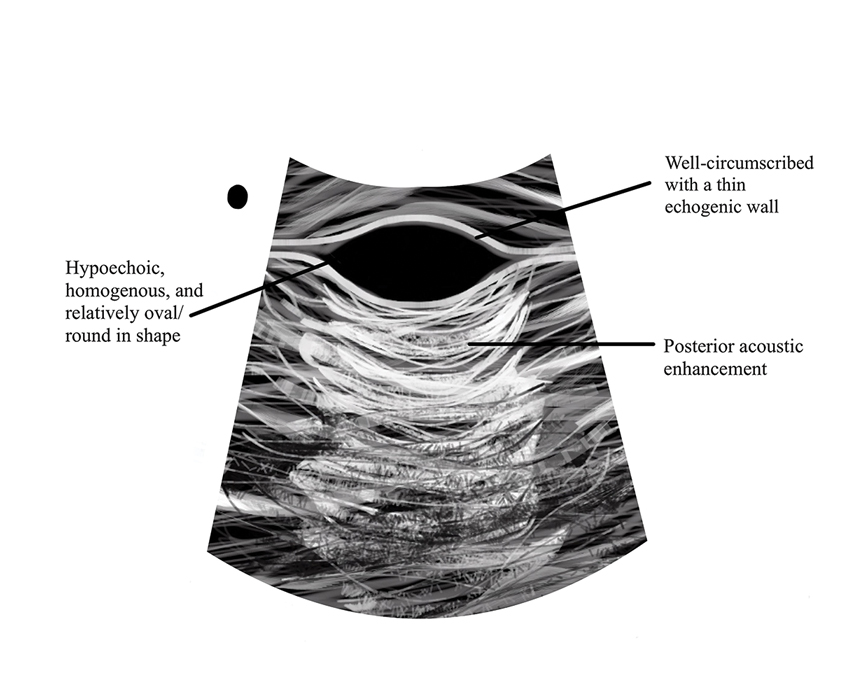

Ultrasonography has demonstrated utility in diagnosing steatocystomas.33-35 Steatocystomas have incidentally been found on routine mammograms and can demonstrate well-defined circular nodules with radiolucent characteristics and a thin radiodense outline.33,36 Homogeneous hypoechoic nodules within the dermis without posterior acoustic features generally are observed (eFigure 3).33,37 In patients declining biopsy, US may be useful in further characterization of an unknown lesion. Color Doppler US can be used to distinguish SMS from HS. Specifically, SM typically exhibits an absence of Doppler signaling due to a lack of vascularity, providing a helpful diagnostic clue for the SMS variant.33

Management and Treatment Options

There is no established standard treatment for steatocystomas; therefore, the approach to management is contingent on clinical presentation and patient preferences. Various medical, surgical, and laser management options are available, each with its own advantages and limitations. Treatment of SM is difficult due to the large number of lesions.38 In many cases, continued observation is a viable treatment option, as most SS and SM lesions are asymptomatic; however, cosmetic concerns can be debilitating for patients with SM and may warrant intervention.39 More extensive medical and surgical management often are necessary in SMS due to associated morbidity. Discussing options and goals as well as setting realistic expectations with the patient are essential in determining the optimal approach.

Medical Management—In medical literature, oral isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid) has been the mainstay of therapy for steatocystoma, as its effect on the size and activity of sebaceous glands is hypothesized to decrease disease activity.38,40 Interventional studies and case reports have exhibited varying degrees of effectiveness.1,38-41 Some reports depict a reduction in the formation of new lesions and a decrease in the size of pre-existing lesions, some show mild delayed therapeutic efficacy, and others suggest exacerbation of the condition.1,38-41 This outcome variability is attributed to isotretinoin’s preferential efficacy in treating inflammatory lesions.40,42

Tetracycline derivatives and intralesional steroid injections also have been employed with some efficacy in patients with focal inflammatory SM and SMS.43 There is limited evidence on the long-term outcomes of these interventions, and intralesional injections often are not recommended in conditions such as SM, in which there are many lesions present.

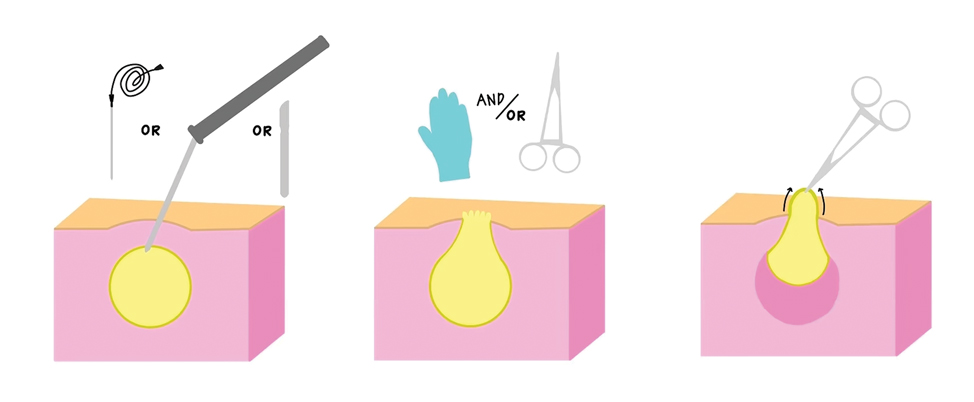

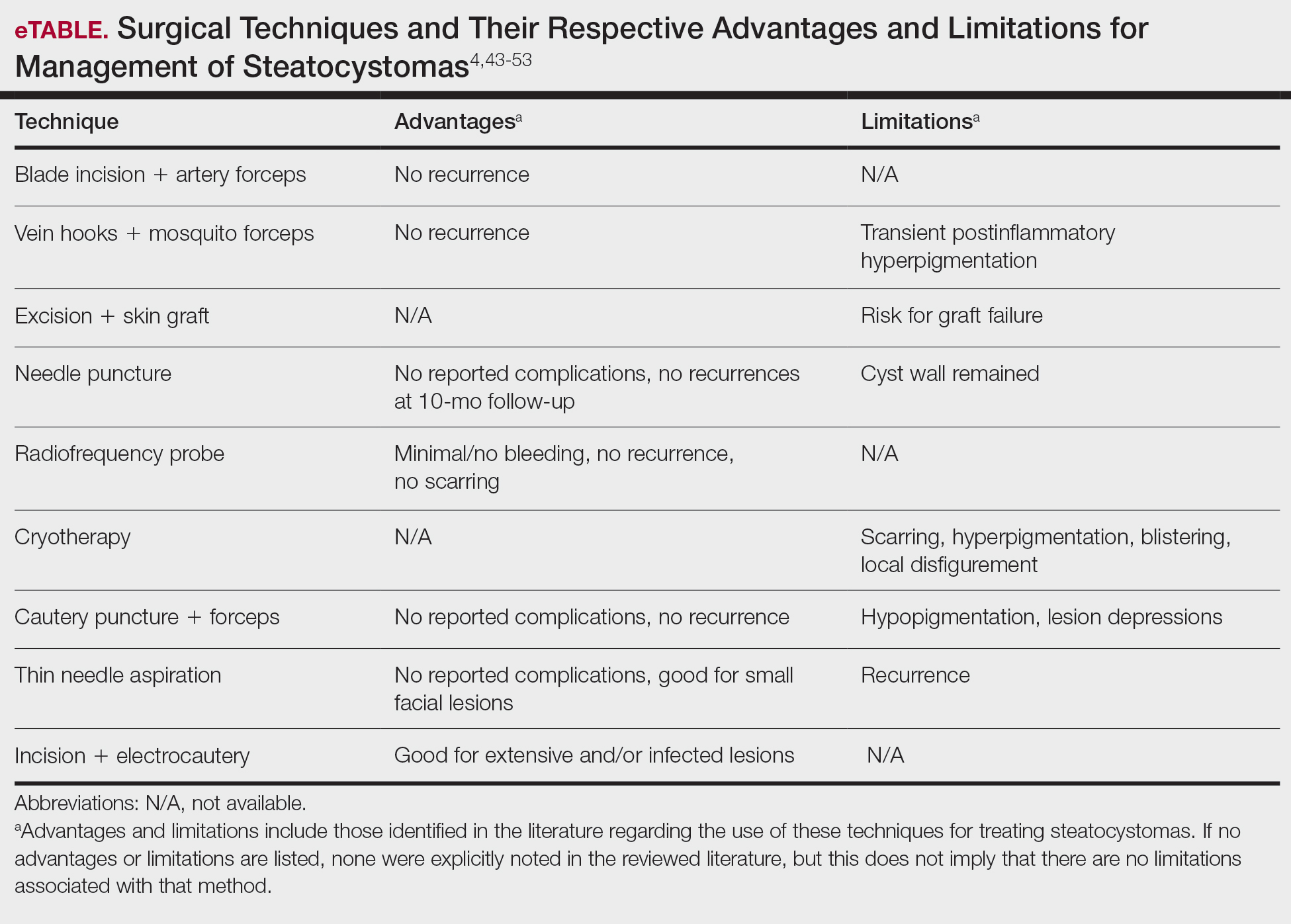

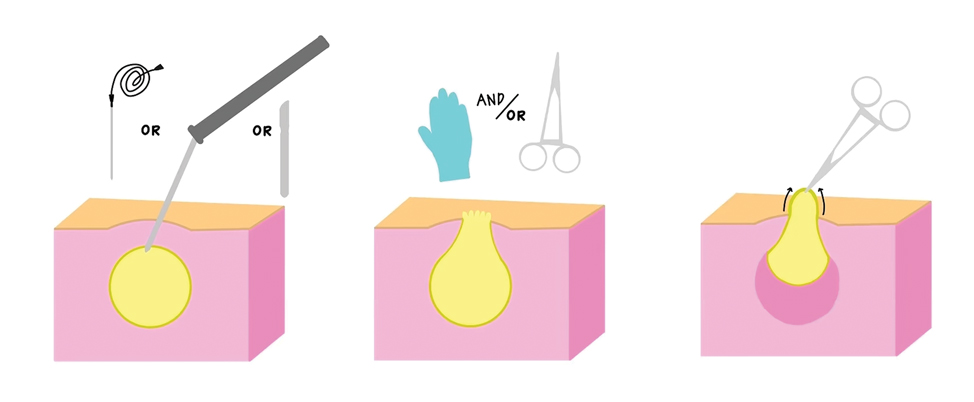

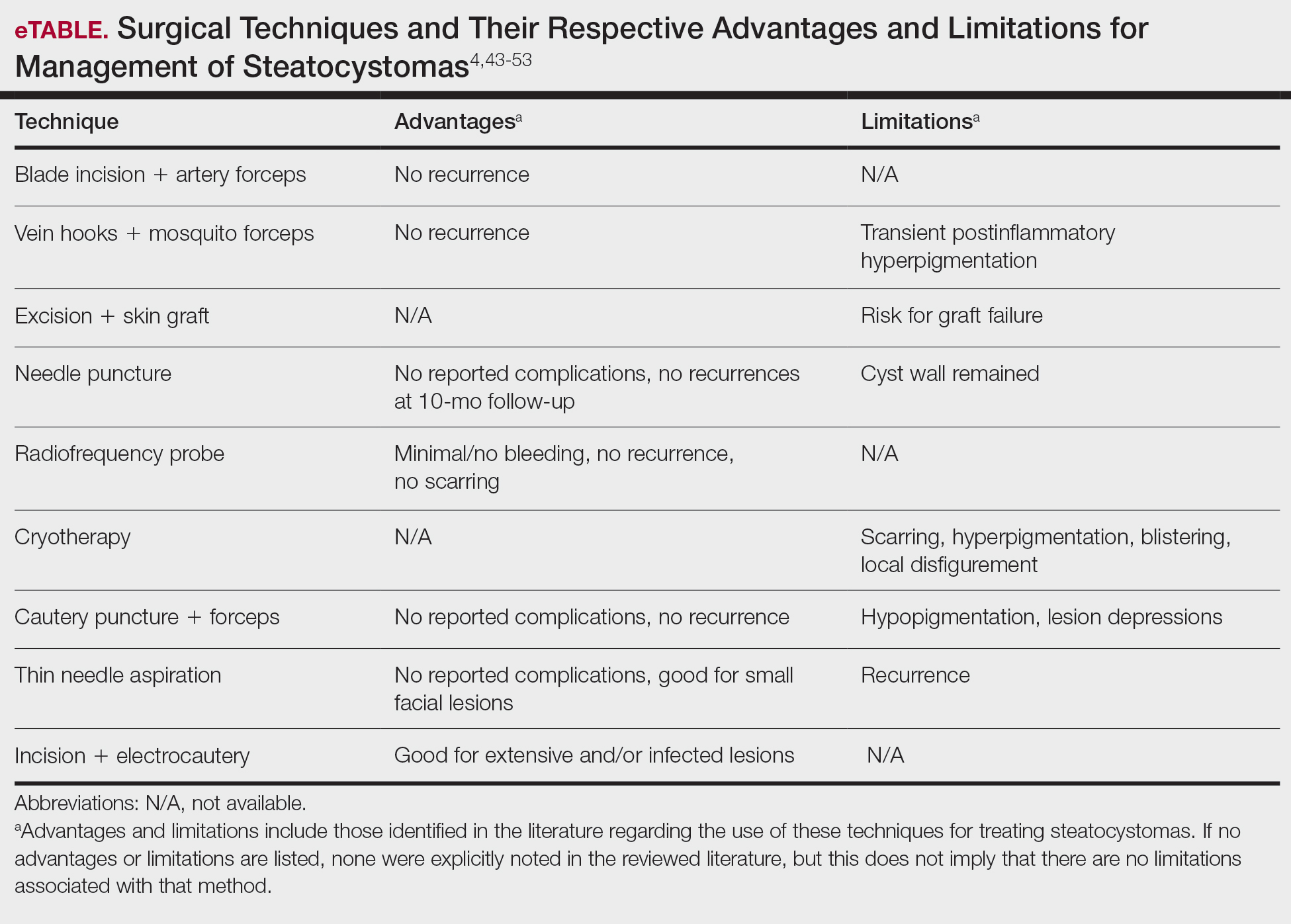

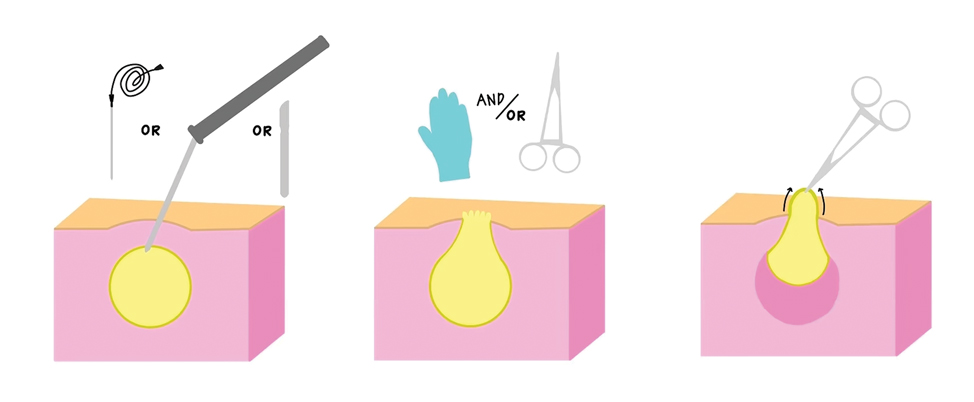

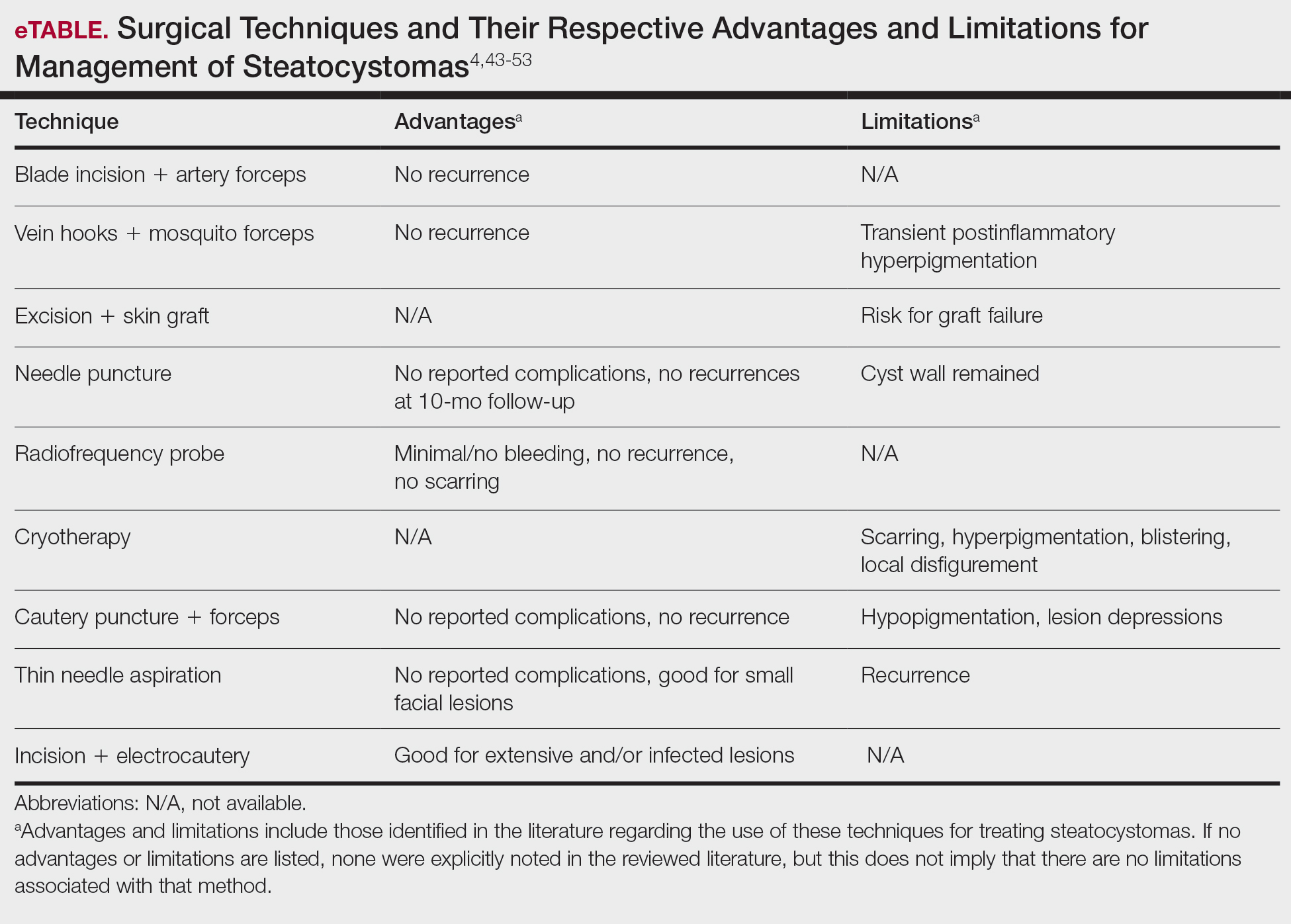

Surgical Management—Minimally invasive surgical procedures including drainage and resections have been used with varying efficacy in SS and SM. Typically, a 2- to 3-mm incision or sharp-tipped cautery is employed to puncture the cyst. Alternatively, radiofrequency probes with a 2.4-MHz frequency setting have been used to minimize incision size.44 The contents then are expressed with manual pressure or forceps, and the cyst sac is extracted using forceps and/or a vein hook (eFigure 4).44,45 The specific surgical techniques and their respective advantages and limitations are summarized in the eTable. Reported advantages and limitations of surgical techniques are derived from information provided by the authors of steatocystoma case reports, which are based on observations of a very limited sample size.

Laser Treatment—Various laser modalities have been used in the management of steatocystomas, including carbon dioxide lasers, erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet lasers, 1450-nm diode plus 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber lasers, and 1927-nm diode lasers.54,55-57 These lasers are used to perforate the cyst before extirpation and have displayed advantages in minimizing scar length.58 The super-pulse mode of carbon dioxide lasers demonstrates efficacy with minimal scarring and recurrence, and this mode is preferred to minimize thermal damage.54,59 Furthermore, this modality can be especially useful in patients whose condition is refractory to other noninvasive options.59 Similarly, the erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser was well tolerated with no complications noted.55 The 1927-nm diode laser also displayed good outcomes as well as no recurrence.57 With laser use, it is important to note that multiple treatments are needed to see optimal outcomes.54 Moreover, laser settings must be carefully considered, especially in patients with Fitzpatrick skin type III or higher, and topical anti-inflammatory agents should be considered posttreatment to minimize complications.54,59,60

Recommendations

For management of SS, we recommend conservative therapy of watchful observation, as scarring or postinflammatory pigment change may be brought on by medical or surgical therapy; however, if SS is cosmetically bothersome, laser or surgical excision can be done (eFigure 4).4,43-53 It is important to counsel the patient on risks/benefits. For SM, watchful observation also is indicated; however, systemic therapies aimed at prevention may be the most efficacious by limiting disease progression, and oral tetracycline or isotretinoin may be tried.4 Tetracyclines have the risk for photosensitivity and are teratogenic, while isotretinoin is extremely teratogenic, requires laboratory monitoring and regular pregnancy tests in women, and often causes substantial mucosal dryness. If lesions are bothersome or refractory to these therapies, intralesional steroids or surgical/laser procedures can be tried throughout multiple visits.43-53 For SMS, systemic therapies frequently are recommended. The risks of systemic tetracycline and isotretinoin therapies must be discussed. Patients with treatment-refractory SMS may require surgical excision or deroofing of sinus tracts.43-53 This management is similar to that of HS and must be tailored to the patient.

Conclusion

Overall, steatocystomas are a relatively rare pathology, with a limited consensus on their etiology and management. This review summarizes the current knowledge on the condition to support clinicians in diagnosis and management, ranging from watchful waiting to surgical removal. By individualizing treatment plans, clinicians ultimately can optimize outcomes in patients with steatocystomas.

- Santana CN, Pereira DD, Lisboa AP, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa: case report of a rare condition. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):51-53.

- Atzori L, Zanniello R, Pilloni L, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa associated with hidradenitis suppurativa successfully treated with adalimumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(Suppl 6):42-44.

- Jamieson WA. Case of numerous cutaneous cysts scattered over the body. Edinb Med J. 1873;19:223-225.

- Kamra HT, Gadgil PA, Ovhal AG, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex-a rare genetic disorder: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:166-168.

- Brownstein MH. Steatocystoma simplex. A solitary steatocystoma. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:409-411.

- McDonald RM, Reed WB. Natal teeth and steatocystoma multiplex complicated by hidradenitis suppurativa. A new syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1132-1134.

- Plewig G, Wolff HH, Braun-Falco O. Steatocystoma multiplex: anatomic reevaluation, electron microscopy, and autoradiography. Arch Dermatol. 1982;272:363-380.

- Fletcher J, Posso-De Los Rios C, Jambrosic J, A, et al. Coexistence of hidradenitis suppurativa and steatocystoma multiplex: is it a new variant of hidradenitis suppurativa? J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:586-590.

- Cho S, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinical and histologic features of 64 cases of steatocystoma multiplex. J Dermatol. 2002;29:152-156.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480.

- Liu Q, Wu W, Lu J, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex is associated with the R94C mutation in the KRTl7 gene. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5072-5076.

- Yang L, Zhang S, Wang G. Keratin 17 in disease pathogenesis: from cancer to dermatoses. J Pathol. 2019;247:158-165.

- Shamloul G, Khachemoune A. An updated review of the sebaceous gland and its role in health and diseases Part 1: embryology, evolution, structure, and function of sebaceous glands. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:e14695.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kircik LH, Stein Gold L, et al. Androgens, androgen receptors, and the skin: from the laboratory to the clinic with emphasis on clinical and therapeutic implications. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:30-35.

- Porras Fimbres DC, Wolfe SA, Kelley CE. Proliferation of steatocystomas in 2 transgender men. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;26:70-72.

- Marasca C, Megna M, Donnarumma M, et al. A case of steatocystoma multiplex in a psoriatic patient during treatment with anti-IL-12/23. Skin Appendage Disord. 2020;6:309-311.

- Gordon Spratt EA, Kaplan J, Patel RR, et al. Steatocystoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20721.

- Sharma A, Agrawal S, Dhurat R, et al. An unusual case of facial steatocystoma multiplex: a clinicopathologic and dermoscopic report. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:58-63.

- Rahman MH, Islam MS, Ansari NP. Atypical steatocystoma multiplex with calcification. ISRN Dermatol. 2011;2011:381901.

- Beyer AV, Vossmann D. Steatocystoma multiplex. Article in German. Hautarzt. 1996;47:469-471.

- Yanagi T, Matsumura T. Steatocystoma multiplex presenting as acral subcutaneous nodules. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:374-375.

- Marzano AV, Tavecchio S, Balice Y, et al. Acral subcutaneous steatocystoma multiplex: a distinct subtype of the disease? Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:198-201.

- Ferrandiz C, Peyri J. Steatocystoma multiplex. Article in Spanish. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1984;12:173-176.

- Alotaibi L, Alsaif M, Alhumidi A, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa: a case with unusual giant cysts over the scalp and neck. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:71-76.

- Kim SJ, Park HJ, Oh ST, et al. A case of steatocystoma multiplex limited to scalp. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:106-109.

- Patrizi A, Neri I, Guerrini V, et al. Persistent milia, steatocystoma multiplex and eruptive vellus hair cysts: variable expression of multiple pilosebaceous cysts within an affected family. Dermatology. 1998;196:392-396.

- Tomková H, Fujimoto W, Arata J. Expression of keratins (K10 and K17) in steatocystoma multiplex, eruptive vellus hair cysts, and epidermoid and trichilemmal cysts. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:250-253.

- Patokar AS, Holani AR, Khandait GH, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: an underdiagnosed entity. Int J Trichology. 2022;14:31-33.

- Ohtake N, Kubota Y, Takayama O, et al. Relationship between steatocystoma multiplex and eruptive vellus hair cysts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(5 Pt 2):876-878.

- Yoon H, Kang Y, Park H, et al. Sonographic appearance of steatocystoma: an analysis of 14 pathologically confirmed lesions. Taehan Yongsang Uihakhoe Chi. 2021;82:382-392.

- Varshney M, Aziz M, Maheshwari V, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0420114165.

- Tsai MH, Hsiao YP, Lin WL, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex as initial impression of non-small cell lung cancer with complete response to gefitinib. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:E5-E9.

- Zussino M, Nazzaro G, Moltrasio C, et al. Coexistence of steatocystoma multiplex and hidradenitis suppurativa: assessment of this unique association by means of ultrasonography and color Doppler. Skin Res Technol. 2019;25:877-880.

- Whittle C, Silva-Hirschberg C, Loyola K, et al. Ultrasonographic spectrum of cutaneous cysts with stratified squamous epithelium in pediatric dermatology: pictorial essay. J Ultrasound Med. 2023;42:923-930.

- Arceu M, Martinez G, Alfaro D, et al. Ultrasound morphologic features of steatocystoma multiplex with clinical correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39:2255-2260.

- Reick-Mitrisin V, Reddy A, Shah BA. A breast imaging case of steatocystoma multiplex: a rare condition involving multiple anatomic regions. Cureus. 2022;14:E27756.

- Yoon H, Kang Y, Park H, et al. Sonographic appearance of steatocystoma: an analysis of 14 pathologically confirmed lesions. Taehan Yongsang Uihakhoe Chi. 2021;82:382-392.

- Apaydin R, Bilen N, Bayramgurler D, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum: oral isotretinoin treatment combined with cryotherapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:98-100.

- Sharma A, Agrawal S, Dhurat R, et al. An unusual case of facial steatocystoma multiplex: a clinicopathologic and dermoscopic report. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:58-63.

- Moritz DL, Silverman RA. Steatocystoma multiplex treated with isotretinoin: a delayed response. Cutis. 1988;42:437-439.

- Schwartz JL, Goldsmith LA. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum: treatment with isotretinoin. Cutis. 1984;34:149-153.

- Kim SJ, Park HJ, Oh ST, et al. A case of steatocystoma multiplex limited to the scalp. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:106-109.

- Fekete GL, Fekete JE. Steatocystoma multiplex generalisata partially suppurativa--case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2010;18:114-119.

- Choudhary S, Koley S, Salodkar A. A modified surgical technique for steatocystoma multiplex. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3:25-28.

- Kaya TI, Ikizoglu G, Kokturk A, et al. A simple surgical technique for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:785-788.

- Oertel YC, Scott DM. Cytologic-pathologic correlations: fine needle aspiration of three cases of steatocystoma multiplex. Ann Diagn Pathol. 1998;2:318-320.

- Egbert BM, Price NM, Segal RJ. Steatocystoma multiplex. Report of a florid case and a review. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:334-335.

- Adams BB, Mutasim DF, Nordlund JJ. Steatocystoma multiplex: a quick removal technique. Cutis. 1999;64:127-130.

- Lee SJ, Choe YS, Park BC, et al. The vein hook successfully used for eradication of steatocystoma multiplex. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:82-84.

- Bettes PSL, Lopes SL, Prestes MA, et al. Treatment of a facial variant of the multiple steatocystoma with skin graft: case report. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 1998;13:31-36

- Düzova AN, Sentürk GB. Suggestion for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex located exclusively on the face. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:60-62. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02068.x

- Choudhary S, Koley S, Salodkar A. A modified surgical technique for steatocystoma multiplex. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3:25-28.

- Kaya TI, Ikizoglu G, Kokturk A, et al. A simple surgical technique for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:785-788.

- Bakkour W, Madan V. Carbon dioxide laser perforation and extirpation of steatocystoma multiplex. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:658-662.

- Mumcuog?lu CT, Gurel MS, Kiremitci U, et al. Er: yag laser therapy for steatocystoma multiplex. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:300-301.

- Moody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH, et al. 1,450-nm diode laser in combination with the 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(7 Pt 1):1104-1106.

- Cheon DU, Ko JY. 1927-nm fiber-optic diode laser: a novel therapeutic option for facial steatocystoma multiplex. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:1326-1329.

- Kim KT, Sun H, Chung EH. Comparison of complete surgical excision and minimally invasive excision using CO2 laser for removal of epidermal cysts on the face. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2019;20:84-88.

- Kassira S, Korta DZ, de Feraudy S, et al. Fractionated ablative carbon dioxide laser treatment of steatocystoma multiplex. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:364-366.

- Dixit N, Sardana K, Paliwal P. The rationale of ideal pulse duration and pulse interval in the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex using the carbon dioxide laser in a super-pulse mode as opposedto the ultra-pulse mode. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:454-456.

Steatocystomas are small sebum-filled cysts that typically manifest in the dermis and originate from sebaceous follicles. Although commonly asymptomatic, these lesions can manifest with pruritus or become infected, predisposing patients to further complications.1 Steatocystomas can manifest as single (steatocystoma simplex [SS]) or numerous (steatocystoma multiplex [SM]) lesions; the lesions also can spontaneously rupture with characteristics that resemble hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)(steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa [SMS]).1,2

Steatocystomas are relatively rare, and there is limited consensus in the published literature on the etiology and management of this condition. In this article, we present a comprehensive review of steatocystomas in the current literature. We highlight important features to consider when making the diagnosis and also offer recommendations for best-practice treatment.

Historical Background

Although not explicitly identified by name, the first documentation of steatocystomas is a case report published in 1873. In this account, the author described a patient who presented with approximately 250 flesh-colored dermal cysts across the body that varied in size.3 In 1899, the term steatocystoma multiple—derived from Greek roots meaning “fatty bag”—was first used.4

In 1982, almost a century later, Brownstein5 reported some of the earliest cases of SS. This solitary subtype is identical to SM on a microscopic level; however, unlike SM, this variant occurs as a single lesion that typically forms in adulthood and in the absence of family history. Other benign adnexal tumors (eg, pilomatricomas, pilar cysts, and sebaceous hyperplasias) also can manifest as either solitary or multiple lesions.

In 1976, McDonald and Reed6 reported the first known cases of patients with both SM and HS. At the time, the co-occurrence of these conditions was viewed as coincidental, but there were postulations of a shared inflammatory process and hereditary link6; it was not until 1982 that the term steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum was coined to describe this variant.7 Although rare, there have been multiple documented instances of SMS since. It has been suggested that the convergence of these conditions may indicate a shared follicular proliferation defect.8 Ongoing investigation is warranted to explain the underlying pathogenesis of this unique variant.

Epidemiology

The available epidemiologic data primarily relate to SM, the most common steatocystoma variant. Nevertheless, SM is a relatively rare condition, and the exact incidence and prevalence remain unknown.8,9 Steatocystomas typically manifest in the first and second decades of life and have been observed in patients of both sexes, with studies demonstrating no notable sex bias.4,9

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Steatocystomas can occur sporadically or may be inherited as an autosomal-dominant condition.4 Typically, SS tends to manifest as an isolated occurrence without any inherent genetic predisposition.5 Alternatively, SM may develop sporadically or be associated with a mutation in the keratin 17 gene (KRT17).4 Steatocystoma multiplex also has been associated with at least 4 different missense mutations, including N92H, R94H, and R94C, located on the long (q) arm of chromosome 17.4,10-12

The keratin 17 gene is responsible for encoding the keratin 17 protein, a type I intermediate filament predominantly synthesized in the basal cells of epithelial tissue. This fibrous structural protein can regulate many processes, including inflammation and cell proliferation, and is found in regions such as the sebaceous glands, hair follicles, and eccrine sweat glands. Overexpression of KRT17 has been suggested in other cutaneous conditions, most notably psoriasis.12 Despite KRT17’s many roles, it remains unclear why SM typically manifests with a myriad of sebum-containing cysts as the primary symptom.12 Continued investigation into the genetic underpinnings of SM and the keratin 17 protein is necessary to further elucidate a more comprehensive understanding of this condition.

Hormonal influences have been suggested as a potential trigger for steatocystoma growth.4,13 This condition is associated with dysfunction of the sebaceous glands, and, correspondingly, the incidence of disease is highest in pubertal patients, in whom androgen levels and sebum production are elevated.4,13,14 Two cases of transgender men taking testosterone therapy presenting with steatocystomas provide additional clinical support for this association.15

Additionally, the use of immunomodulatory agents, such as ustekinumab (anti–interleukin 12/interleukin 23), has been shown to trigger SM. It is predicted that the reduced expression of certain interferons and interleukins may lead to downstream consequences in the keratin 17 pathway and lead to SM lesion formation in genetically susceptible individuals.16 Targeting these potential causes in the future may prove efficacious in the secondary prevention of familial SM manifestation or exacerbations.

Mutations in the KRT17 gene also have been implicated in pachyonychia congenita type 2 (PC-2).4 Marked by extensive systemic hyperkeratosis, PC-2 has been observed to coincide with SM in certain patients.4,5 Interestingly, the location of the KRT17 mutations are identical in both PC-2 and SM.4 Although most individuals with hereditary SM do not exhibit the characteristic features of PC-2, mild nail and dental abnormalities have been observed in some SM cases.4,10 This relationship suggests that SM may be a less severe variant of PC-2 or part of a complex polygenetic spectrum of disease.10 Further research is imperative to determine the exact nature and extent of the relationship between these conditions.

Clinical Manifestations

Steatocystomas are flesh-colored subcutaneous cysts that range in size from less than 3 mm to larger than 3 cm in diameter (Figure). They form within a single pilosebaceous unit and typically display firm attachment due to their origination in the dermis.2,7,17 Steatocystomas generally contain lipid material, and less frequently, keratin and hair shafts, distinguishing them as the only “true” sebaceous cysts.18 Their color can range from flesh-toned to yellow, with reports of occasional dark-blue shades and calcifications.19,20 Steatocystomas can persist indefinitely, and they usually are asymptomatic.

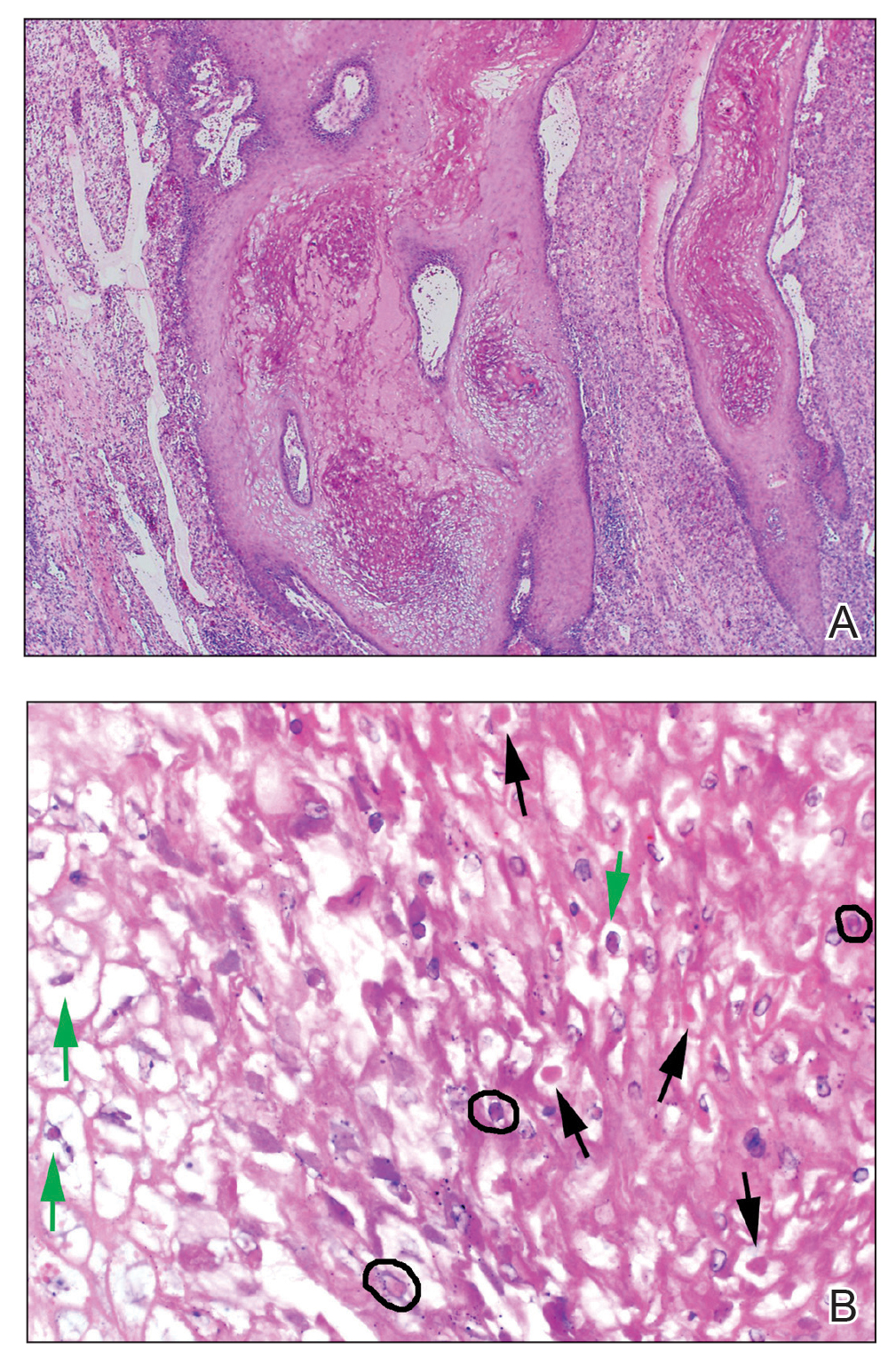

Diagnosis of steatocystoma is confirmed by biopsy.4 Steatocystomas are characterized by a dermal cyst lined by stratified squamous cell epithelium (eFigures 1 and 2).21 Classically they feature flattened sebaceous lobules, multinucleated giant cells, and abortive hair follicles. The lining of these cysts is marked by lymphocytic infiltrate and a dense, wrinkled, eosinophilic keratin cuticle that replaces the granular layer.22 The cyst maintains an epidermal connection through a follicular infundibulum characterized by clumps of keratinocytes, sebocytes, corneocytes, and/or hair follicles.7 Aspirated contents reveal crystalline structures and anucleate squamous cells upon microscopic analysis. That being said, variable histologic findings of steatocystomas have been described.23

Steatocystoma simplex, as the name implies, classifies a single isolated steatocystoma. This subtype exhibits similar histopathologic and clinical features to the other subtypes of steatocystomas. Notably, SS is not associated with a genetic mutation and is not an inherited condition within families.5 Steatocystoma multiplex manifests with many steatocystomas, often distributed widely across the body.3,4 The chest, axillae, and groin are the most common locations; however, these cysts can manifest on the face, back, abdomen, and extremities.4,18-22 Rare occurrences of SM limited to the face, scalp, and distal extremities have been documented.18,21,24,25 Due to the possibility of an autosomal-dominant inheritance, it is advisable to take a comprehensive family history in patients for whom SM is in the differential.17

Steatocystoma multiplex—especially familial variants—has been shown to develop in conjunction with other dermatologic conditions, including eruptive vellus hair (EVH) cysts, persistent infantile milia, and epidermoid/dermoid cysts.26 While some investigators regard these as separate entities due to their varied genetic etiology, it has been suggested that these conditions may be related and that the diagnosis is determined by the location of cyst origin along the sebaceous ducts.26,27 Other dermatologic conditions and lesions that frequently manifest comorbidly with SM include hidrocystomas, syringomas, pilonidal cysts, lichen planus, nodulocystic acne, trichotillomania, trichoblastomas, trichoepithelioma, HS, keratoacanthomas, acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf, and embryonal hair formation. Steatocystoma multiplex, manifesting comorbidly with dental and orofacial malformations (eg, partial noneruption of secondary teeth, natal and defective teeth, and bilateral preauricular sinuses) has been classified as SM natal teeth syndrome.6

Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa is a rare and serious variant of SM characterized by inflammation, cyst rupture, sinus tract formation, and scarring.24 Patients with SMS typically have multiple intact SM cysts, which can aid in differentiation from HS.2,24 Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa is associated with more complications than SS and SM, including cyst perforation, development of purulent and/or foul-smelling discharge, infection, scarring, pain, and overall discomfort.2

Given its rarity and the potential manifestations that overlap with other conditions, steatocystomas easily can be misdiagnosed. In some clinical instances, EVHs may share similar characteristics with SM; however, certain distinguishing features exist, including a central tuft of protruding hairs and different expressed contents, such as the vellus hair shafts, from the cyst’s lumen.28 Furthermore, histologic examination of EVHs reveals epidermoid keratinization of the lining as well as a lack of sebaceous glands within the wall.28,29 Other similar conditions include epidermoid cysts, pilar cysts, lipomas, epidermal inclusion cysts, dermoid cysts, sebaceous hyperplasia, folliculitis, xanthomas, neurofibromatosis, and syringomas.30 Occasionally, SMS can be mistaken for HS or acne conglobata, and SM lesions with a facial distribution can mimic acne vulgaris.1,31 These conditions should be excluded before a diagnosis of SS, SM, or SMS is made.

Importantly, SM is visually indistinguishable from subcutaneous metastasis on physical examination, and there are reports of oncologic conditions (eg, pulmonary adenocarcinoma metastasized to the skin) being mistaken for SS or SM.32 Therefore, a thorough clinical examination, histopathologic analysis, and potential use of other imaging modalities such as ultrasonography (US) are needed to ensure an accurate diagnosis.

Ultrasonography has demonstrated utility in diagnosing steatocystomas.33-35 Steatocystomas have incidentally been found on routine mammograms and can demonstrate well-defined circular nodules with radiolucent characteristics and a thin radiodense outline.33,36 Homogeneous hypoechoic nodules within the dermis without posterior acoustic features generally are observed (eFigure 3).33,37 In patients declining biopsy, US may be useful in further characterization of an unknown lesion. Color Doppler US can be used to distinguish SMS from HS. Specifically, SM typically exhibits an absence of Doppler signaling due to a lack of vascularity, providing a helpful diagnostic clue for the SMS variant.33

Management and Treatment Options

There is no established standard treatment for steatocystomas; therefore, the approach to management is contingent on clinical presentation and patient preferences. Various medical, surgical, and laser management options are available, each with its own advantages and limitations. Treatment of SM is difficult due to the large number of lesions.38 In many cases, continued observation is a viable treatment option, as most SS and SM lesions are asymptomatic; however, cosmetic concerns can be debilitating for patients with SM and may warrant intervention.39 More extensive medical and surgical management often are necessary in SMS due to associated morbidity. Discussing options and goals as well as setting realistic expectations with the patient are essential in determining the optimal approach.

Medical Management—In medical literature, oral isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid) has been the mainstay of therapy for steatocystoma, as its effect on the size and activity of sebaceous glands is hypothesized to decrease disease activity.38,40 Interventional studies and case reports have exhibited varying degrees of effectiveness.1,38-41 Some reports depict a reduction in the formation of new lesions and a decrease in the size of pre-existing lesions, some show mild delayed therapeutic efficacy, and others suggest exacerbation of the condition.1,38-41 This outcome variability is attributed to isotretinoin’s preferential efficacy in treating inflammatory lesions.40,42

Tetracycline derivatives and intralesional steroid injections also have been employed with some efficacy in patients with focal inflammatory SM and SMS.43 There is limited evidence on the long-term outcomes of these interventions, and intralesional injections often are not recommended in conditions such as SM, in which there are many lesions present.

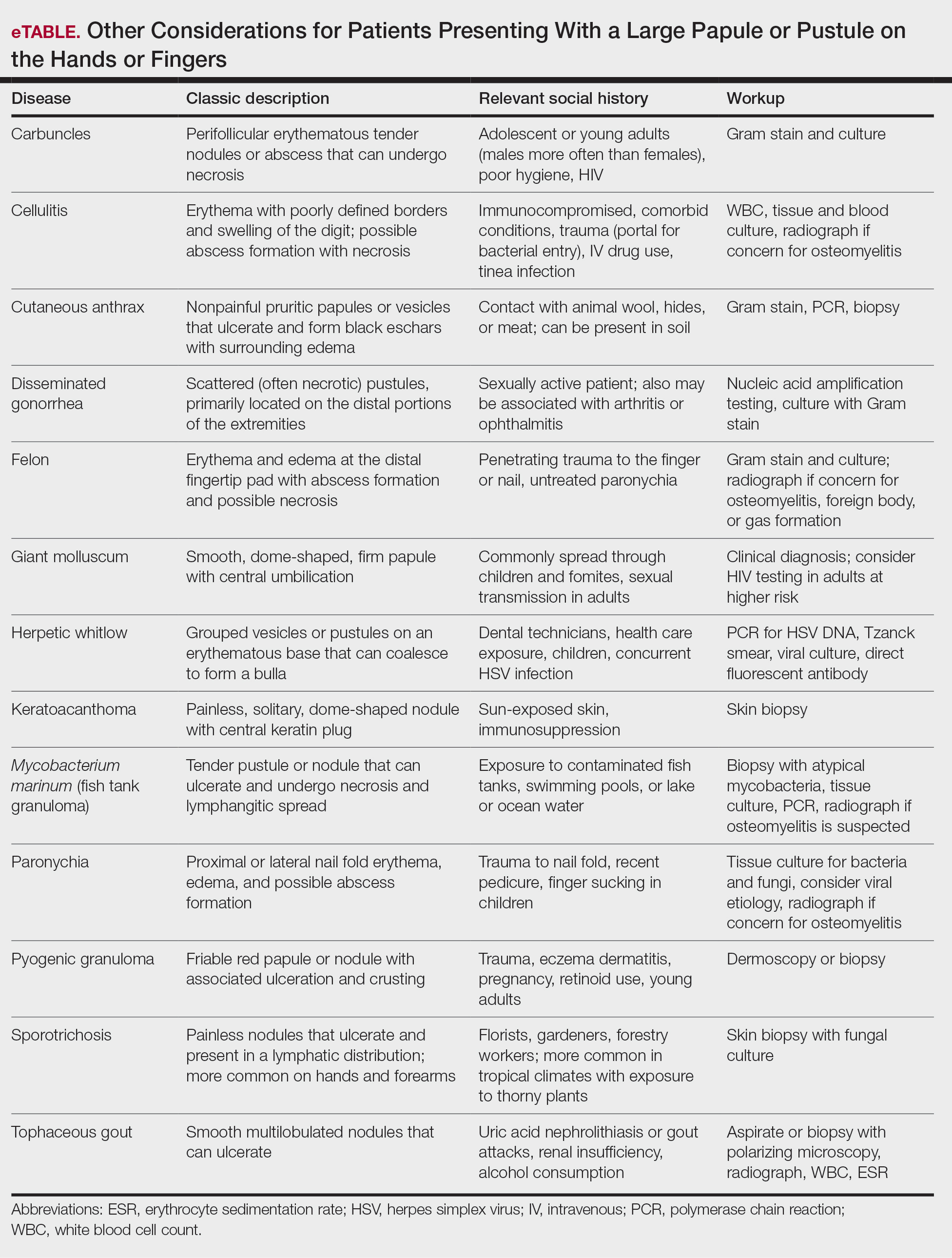

Surgical Management—Minimally invasive surgical procedures including drainage and resections have been used with varying efficacy in SS and SM. Typically, a 2- to 3-mm incision or sharp-tipped cautery is employed to puncture the cyst. Alternatively, radiofrequency probes with a 2.4-MHz frequency setting have been used to minimize incision size.44 The contents then are expressed with manual pressure or forceps, and the cyst sac is extracted using forceps and/or a vein hook (eFigure 4).44,45 The specific surgical techniques and their respective advantages and limitations are summarized in the eTable. Reported advantages and limitations of surgical techniques are derived from information provided by the authors of steatocystoma case reports, which are based on observations of a very limited sample size.

Laser Treatment—Various laser modalities have been used in the management of steatocystomas, including carbon dioxide lasers, erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet lasers, 1450-nm diode plus 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber lasers, and 1927-nm diode lasers.54,55-57 These lasers are used to perforate the cyst before extirpation and have displayed advantages in minimizing scar length.58 The super-pulse mode of carbon dioxide lasers demonstrates efficacy with minimal scarring and recurrence, and this mode is preferred to minimize thermal damage.54,59 Furthermore, this modality can be especially useful in patients whose condition is refractory to other noninvasive options.59 Similarly, the erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser was well tolerated with no complications noted.55 The 1927-nm diode laser also displayed good outcomes as well as no recurrence.57 With laser use, it is important to note that multiple treatments are needed to see optimal outcomes.54 Moreover, laser settings must be carefully considered, especially in patients with Fitzpatrick skin type III or higher, and topical anti-inflammatory agents should be considered posttreatment to minimize complications.54,59,60

Recommendations

For management of SS, we recommend conservative therapy of watchful observation, as scarring or postinflammatory pigment change may be brought on by medical or surgical therapy; however, if SS is cosmetically bothersome, laser or surgical excision can be done (eFigure 4).4,43-53 It is important to counsel the patient on risks/benefits. For SM, watchful observation also is indicated; however, systemic therapies aimed at prevention may be the most efficacious by limiting disease progression, and oral tetracycline or isotretinoin may be tried.4 Tetracyclines have the risk for photosensitivity and are teratogenic, while isotretinoin is extremely teratogenic, requires laboratory monitoring and regular pregnancy tests in women, and often causes substantial mucosal dryness. If lesions are bothersome or refractory to these therapies, intralesional steroids or surgical/laser procedures can be tried throughout multiple visits.43-53 For SMS, systemic therapies frequently are recommended. The risks of systemic tetracycline and isotretinoin therapies must be discussed. Patients with treatment-refractory SMS may require surgical excision or deroofing of sinus tracts.43-53 This management is similar to that of HS and must be tailored to the patient.

Conclusion

Overall, steatocystomas are a relatively rare pathology, with a limited consensus on their etiology and management. This review summarizes the current knowledge on the condition to support clinicians in diagnosis and management, ranging from watchful waiting to surgical removal. By individualizing treatment plans, clinicians ultimately can optimize outcomes in patients with steatocystomas.

Steatocystomas are small sebum-filled cysts that typically manifest in the dermis and originate from sebaceous follicles. Although commonly asymptomatic, these lesions can manifest with pruritus or become infected, predisposing patients to further complications.1 Steatocystomas can manifest as single (steatocystoma simplex [SS]) or numerous (steatocystoma multiplex [SM]) lesions; the lesions also can spontaneously rupture with characteristics that resemble hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)(steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa [SMS]).1,2

Steatocystomas are relatively rare, and there is limited consensus in the published literature on the etiology and management of this condition. In this article, we present a comprehensive review of steatocystomas in the current literature. We highlight important features to consider when making the diagnosis and also offer recommendations for best-practice treatment.

Historical Background

Although not explicitly identified by name, the first documentation of steatocystomas is a case report published in 1873. In this account, the author described a patient who presented with approximately 250 flesh-colored dermal cysts across the body that varied in size.3 In 1899, the term steatocystoma multiple—derived from Greek roots meaning “fatty bag”—was first used.4

In 1982, almost a century later, Brownstein5 reported some of the earliest cases of SS. This solitary subtype is identical to SM on a microscopic level; however, unlike SM, this variant occurs as a single lesion that typically forms in adulthood and in the absence of family history. Other benign adnexal tumors (eg, pilomatricomas, pilar cysts, and sebaceous hyperplasias) also can manifest as either solitary or multiple lesions.

In 1976, McDonald and Reed6 reported the first known cases of patients with both SM and HS. At the time, the co-occurrence of these conditions was viewed as coincidental, but there were postulations of a shared inflammatory process and hereditary link6; it was not until 1982 that the term steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum was coined to describe this variant.7 Although rare, there have been multiple documented instances of SMS since. It has been suggested that the convergence of these conditions may indicate a shared follicular proliferation defect.8 Ongoing investigation is warranted to explain the underlying pathogenesis of this unique variant.

Epidemiology

The available epidemiologic data primarily relate to SM, the most common steatocystoma variant. Nevertheless, SM is a relatively rare condition, and the exact incidence and prevalence remain unknown.8,9 Steatocystomas typically manifest in the first and second decades of life and have been observed in patients of both sexes, with studies demonstrating no notable sex bias.4,9

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Steatocystomas can occur sporadically or may be inherited as an autosomal-dominant condition.4 Typically, SS tends to manifest as an isolated occurrence without any inherent genetic predisposition.5 Alternatively, SM may develop sporadically or be associated with a mutation in the keratin 17 gene (KRT17).4 Steatocystoma multiplex also has been associated with at least 4 different missense mutations, including N92H, R94H, and R94C, located on the long (q) arm of chromosome 17.4,10-12

The keratin 17 gene is responsible for encoding the keratin 17 protein, a type I intermediate filament predominantly synthesized in the basal cells of epithelial tissue. This fibrous structural protein can regulate many processes, including inflammation and cell proliferation, and is found in regions such as the sebaceous glands, hair follicles, and eccrine sweat glands. Overexpression of KRT17 has been suggested in other cutaneous conditions, most notably psoriasis.12 Despite KRT17’s many roles, it remains unclear why SM typically manifests with a myriad of sebum-containing cysts as the primary symptom.12 Continued investigation into the genetic underpinnings of SM and the keratin 17 protein is necessary to further elucidate a more comprehensive understanding of this condition.

Hormonal influences have been suggested as a potential trigger for steatocystoma growth.4,13 This condition is associated with dysfunction of the sebaceous glands, and, correspondingly, the incidence of disease is highest in pubertal patients, in whom androgen levels and sebum production are elevated.4,13,14 Two cases of transgender men taking testosterone therapy presenting with steatocystomas provide additional clinical support for this association.15

Additionally, the use of immunomodulatory agents, such as ustekinumab (anti–interleukin 12/interleukin 23), has been shown to trigger SM. It is predicted that the reduced expression of certain interferons and interleukins may lead to downstream consequences in the keratin 17 pathway and lead to SM lesion formation in genetically susceptible individuals.16 Targeting these potential causes in the future may prove efficacious in the secondary prevention of familial SM manifestation or exacerbations.

Mutations in the KRT17 gene also have been implicated in pachyonychia congenita type 2 (PC-2).4 Marked by extensive systemic hyperkeratosis, PC-2 has been observed to coincide with SM in certain patients.4,5 Interestingly, the location of the KRT17 mutations are identical in both PC-2 and SM.4 Although most individuals with hereditary SM do not exhibit the characteristic features of PC-2, mild nail and dental abnormalities have been observed in some SM cases.4,10 This relationship suggests that SM may be a less severe variant of PC-2 or part of a complex polygenetic spectrum of disease.10 Further research is imperative to determine the exact nature and extent of the relationship between these conditions.

Clinical Manifestations

Steatocystomas are flesh-colored subcutaneous cysts that range in size from less than 3 mm to larger than 3 cm in diameter (Figure). They form within a single pilosebaceous unit and typically display firm attachment due to their origination in the dermis.2,7,17 Steatocystomas generally contain lipid material, and less frequently, keratin and hair shafts, distinguishing them as the only “true” sebaceous cysts.18 Their color can range from flesh-toned to yellow, with reports of occasional dark-blue shades and calcifications.19,20 Steatocystomas can persist indefinitely, and they usually are asymptomatic.

Diagnosis of steatocystoma is confirmed by biopsy.4 Steatocystomas are characterized by a dermal cyst lined by stratified squamous cell epithelium (eFigures 1 and 2).21 Classically they feature flattened sebaceous lobules, multinucleated giant cells, and abortive hair follicles. The lining of these cysts is marked by lymphocytic infiltrate and a dense, wrinkled, eosinophilic keratin cuticle that replaces the granular layer.22 The cyst maintains an epidermal connection through a follicular infundibulum characterized by clumps of keratinocytes, sebocytes, corneocytes, and/or hair follicles.7 Aspirated contents reveal crystalline structures and anucleate squamous cells upon microscopic analysis. That being said, variable histologic findings of steatocystomas have been described.23

Steatocystoma simplex, as the name implies, classifies a single isolated steatocystoma. This subtype exhibits similar histopathologic and clinical features to the other subtypes of steatocystomas. Notably, SS is not associated with a genetic mutation and is not an inherited condition within families.5 Steatocystoma multiplex manifests with many steatocystomas, often distributed widely across the body.3,4 The chest, axillae, and groin are the most common locations; however, these cysts can manifest on the face, back, abdomen, and extremities.4,18-22 Rare occurrences of SM limited to the face, scalp, and distal extremities have been documented.18,21,24,25 Due to the possibility of an autosomal-dominant inheritance, it is advisable to take a comprehensive family history in patients for whom SM is in the differential.17

Steatocystoma multiplex—especially familial variants—has been shown to develop in conjunction with other dermatologic conditions, including eruptive vellus hair (EVH) cysts, persistent infantile milia, and epidermoid/dermoid cysts.26 While some investigators regard these as separate entities due to their varied genetic etiology, it has been suggested that these conditions may be related and that the diagnosis is determined by the location of cyst origin along the sebaceous ducts.26,27 Other dermatologic conditions and lesions that frequently manifest comorbidly with SM include hidrocystomas, syringomas, pilonidal cysts, lichen planus, nodulocystic acne, trichotillomania, trichoblastomas, trichoepithelioma, HS, keratoacanthomas, acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf, and embryonal hair formation. Steatocystoma multiplex, manifesting comorbidly with dental and orofacial malformations (eg, partial noneruption of secondary teeth, natal and defective teeth, and bilateral preauricular sinuses) has been classified as SM natal teeth syndrome.6

Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa is a rare and serious variant of SM characterized by inflammation, cyst rupture, sinus tract formation, and scarring.24 Patients with SMS typically have multiple intact SM cysts, which can aid in differentiation from HS.2,24 Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa is associated with more complications than SS and SM, including cyst perforation, development of purulent and/or foul-smelling discharge, infection, scarring, pain, and overall discomfort.2

Given its rarity and the potential manifestations that overlap with other conditions, steatocystomas easily can be misdiagnosed. In some clinical instances, EVHs may share similar characteristics with SM; however, certain distinguishing features exist, including a central tuft of protruding hairs and different expressed contents, such as the vellus hair shafts, from the cyst’s lumen.28 Furthermore, histologic examination of EVHs reveals epidermoid keratinization of the lining as well as a lack of sebaceous glands within the wall.28,29 Other similar conditions include epidermoid cysts, pilar cysts, lipomas, epidermal inclusion cysts, dermoid cysts, sebaceous hyperplasia, folliculitis, xanthomas, neurofibromatosis, and syringomas.30 Occasionally, SMS can be mistaken for HS or acne conglobata, and SM lesions with a facial distribution can mimic acne vulgaris.1,31 These conditions should be excluded before a diagnosis of SS, SM, or SMS is made.

Importantly, SM is visually indistinguishable from subcutaneous metastasis on physical examination, and there are reports of oncologic conditions (eg, pulmonary adenocarcinoma metastasized to the skin) being mistaken for SS or SM.32 Therefore, a thorough clinical examination, histopathologic analysis, and potential use of other imaging modalities such as ultrasonography (US) are needed to ensure an accurate diagnosis.

Ultrasonography has demonstrated utility in diagnosing steatocystomas.33-35 Steatocystomas have incidentally been found on routine mammograms and can demonstrate well-defined circular nodules with radiolucent characteristics and a thin radiodense outline.33,36 Homogeneous hypoechoic nodules within the dermis without posterior acoustic features generally are observed (eFigure 3).33,37 In patients declining biopsy, US may be useful in further characterization of an unknown lesion. Color Doppler US can be used to distinguish SMS from HS. Specifically, SM typically exhibits an absence of Doppler signaling due to a lack of vascularity, providing a helpful diagnostic clue for the SMS variant.33

Management and Treatment Options

There is no established standard treatment for steatocystomas; therefore, the approach to management is contingent on clinical presentation and patient preferences. Various medical, surgical, and laser management options are available, each with its own advantages and limitations. Treatment of SM is difficult due to the large number of lesions.38 In many cases, continued observation is a viable treatment option, as most SS and SM lesions are asymptomatic; however, cosmetic concerns can be debilitating for patients with SM and may warrant intervention.39 More extensive medical and surgical management often are necessary in SMS due to associated morbidity. Discussing options and goals as well as setting realistic expectations with the patient are essential in determining the optimal approach.

Medical Management—In medical literature, oral isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid) has been the mainstay of therapy for steatocystoma, as its effect on the size and activity of sebaceous glands is hypothesized to decrease disease activity.38,40 Interventional studies and case reports have exhibited varying degrees of effectiveness.1,38-41 Some reports depict a reduction in the formation of new lesions and a decrease in the size of pre-existing lesions, some show mild delayed therapeutic efficacy, and others suggest exacerbation of the condition.1,38-41 This outcome variability is attributed to isotretinoin’s preferential efficacy in treating inflammatory lesions.40,42

Tetracycline derivatives and intralesional steroid injections also have been employed with some efficacy in patients with focal inflammatory SM and SMS.43 There is limited evidence on the long-term outcomes of these interventions, and intralesional injections often are not recommended in conditions such as SM, in which there are many lesions present.

Surgical Management—Minimally invasive surgical procedures including drainage and resections have been used with varying efficacy in SS and SM. Typically, a 2- to 3-mm incision or sharp-tipped cautery is employed to puncture the cyst. Alternatively, radiofrequency probes with a 2.4-MHz frequency setting have been used to minimize incision size.44 The contents then are expressed with manual pressure or forceps, and the cyst sac is extracted using forceps and/or a vein hook (eFigure 4).44,45 The specific surgical techniques and their respective advantages and limitations are summarized in the eTable. Reported advantages and limitations of surgical techniques are derived from information provided by the authors of steatocystoma case reports, which are based on observations of a very limited sample size.

Laser Treatment—Various laser modalities have been used in the management of steatocystomas, including carbon dioxide lasers, erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet lasers, 1450-nm diode plus 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber lasers, and 1927-nm diode lasers.54,55-57 These lasers are used to perforate the cyst before extirpation and have displayed advantages in minimizing scar length.58 The super-pulse mode of carbon dioxide lasers demonstrates efficacy with minimal scarring and recurrence, and this mode is preferred to minimize thermal damage.54,59 Furthermore, this modality can be especially useful in patients whose condition is refractory to other noninvasive options.59 Similarly, the erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser was well tolerated with no complications noted.55 The 1927-nm diode laser also displayed good outcomes as well as no recurrence.57 With laser use, it is important to note that multiple treatments are needed to see optimal outcomes.54 Moreover, laser settings must be carefully considered, especially in patients with Fitzpatrick skin type III or higher, and topical anti-inflammatory agents should be considered posttreatment to minimize complications.54,59,60

Recommendations

For management of SS, we recommend conservative therapy of watchful observation, as scarring or postinflammatory pigment change may be brought on by medical or surgical therapy; however, if SS is cosmetically bothersome, laser or surgical excision can be done (eFigure 4).4,43-53 It is important to counsel the patient on risks/benefits. For SM, watchful observation also is indicated; however, systemic therapies aimed at prevention may be the most efficacious by limiting disease progression, and oral tetracycline or isotretinoin may be tried.4 Tetracyclines have the risk for photosensitivity and are teratogenic, while isotretinoin is extremely teratogenic, requires laboratory monitoring and regular pregnancy tests in women, and often causes substantial mucosal dryness. If lesions are bothersome or refractory to these therapies, intralesional steroids or surgical/laser procedures can be tried throughout multiple visits.43-53 For SMS, systemic therapies frequently are recommended. The risks of systemic tetracycline and isotretinoin therapies must be discussed. Patients with treatment-refractory SMS may require surgical excision or deroofing of sinus tracts.43-53 This management is similar to that of HS and must be tailored to the patient.

Conclusion

Overall, steatocystomas are a relatively rare pathology, with a limited consensus on their etiology and management. This review summarizes the current knowledge on the condition to support clinicians in diagnosis and management, ranging from watchful waiting to surgical removal. By individualizing treatment plans, clinicians ultimately can optimize outcomes in patients with steatocystomas.

- Santana CN, Pereira DD, Lisboa AP, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa: case report of a rare condition. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):51-53.

- Atzori L, Zanniello R, Pilloni L, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa associated with hidradenitis suppurativa successfully treated with adalimumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(Suppl 6):42-44.

- Jamieson WA. Case of numerous cutaneous cysts scattered over the body. Edinb Med J. 1873;19:223-225.

- Kamra HT, Gadgil PA, Ovhal AG, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex-a rare genetic disorder: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:166-168.

- Brownstein MH. Steatocystoma simplex. A solitary steatocystoma. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:409-411.

- McDonald RM, Reed WB. Natal teeth and steatocystoma multiplex complicated by hidradenitis suppurativa. A new syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1132-1134.

- Plewig G, Wolff HH, Braun-Falco O. Steatocystoma multiplex: anatomic reevaluation, electron microscopy, and autoradiography. Arch Dermatol. 1982;272:363-380.

- Fletcher J, Posso-De Los Rios C, Jambrosic J, A, et al. Coexistence of hidradenitis suppurativa and steatocystoma multiplex: is it a new variant of hidradenitis suppurativa? J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:586-590.

- Cho S, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinical and histologic features of 64 cases of steatocystoma multiplex. J Dermatol. 2002;29:152-156.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480.

- Liu Q, Wu W, Lu J, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex is associated with the R94C mutation in the KRTl7 gene. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5072-5076.

- Yang L, Zhang S, Wang G. Keratin 17 in disease pathogenesis: from cancer to dermatoses. J Pathol. 2019;247:158-165.

- Shamloul G, Khachemoune A. An updated review of the sebaceous gland and its role in health and diseases Part 1: embryology, evolution, structure, and function of sebaceous glands. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:e14695.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kircik LH, Stein Gold L, et al. Androgens, androgen receptors, and the skin: from the laboratory to the clinic with emphasis on clinical and therapeutic implications. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:30-35.

- Porras Fimbres DC, Wolfe SA, Kelley CE. Proliferation of steatocystomas in 2 transgender men. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;26:70-72.

- Marasca C, Megna M, Donnarumma M, et al. A case of steatocystoma multiplex in a psoriatic patient during treatment with anti-IL-12/23. Skin Appendage Disord. 2020;6:309-311.

- Gordon Spratt EA, Kaplan J, Patel RR, et al. Steatocystoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20721.

- Sharma A, Agrawal S, Dhurat R, et al. An unusual case of facial steatocystoma multiplex: a clinicopathologic and dermoscopic report. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:58-63.

- Rahman MH, Islam MS, Ansari NP. Atypical steatocystoma multiplex with calcification. ISRN Dermatol. 2011;2011:381901.

- Beyer AV, Vossmann D. Steatocystoma multiplex. Article in German. Hautarzt. 1996;47:469-471.

- Yanagi T, Matsumura T. Steatocystoma multiplex presenting as acral subcutaneous nodules. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:374-375.

- Marzano AV, Tavecchio S, Balice Y, et al. Acral subcutaneous steatocystoma multiplex: a distinct subtype of the disease? Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:198-201.

- Ferrandiz C, Peyri J. Steatocystoma multiplex. Article in Spanish. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1984;12:173-176.

- Alotaibi L, Alsaif M, Alhumidi A, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa: a case with unusual giant cysts over the scalp and neck. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:71-76.

- Kim SJ, Park HJ, Oh ST, et al. A case of steatocystoma multiplex limited to scalp. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:106-109.

- Patrizi A, Neri I, Guerrini V, et al. Persistent milia, steatocystoma multiplex and eruptive vellus hair cysts: variable expression of multiple pilosebaceous cysts within an affected family. Dermatology. 1998;196:392-396.

- Tomková H, Fujimoto W, Arata J. Expression of keratins (K10 and K17) in steatocystoma multiplex, eruptive vellus hair cysts, and epidermoid and trichilemmal cysts. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:250-253.

- Patokar AS, Holani AR, Khandait GH, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: an underdiagnosed entity. Int J Trichology. 2022;14:31-33.

- Ohtake N, Kubota Y, Takayama O, et al. Relationship between steatocystoma multiplex and eruptive vellus hair cysts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(5 Pt 2):876-878.

- Yoon H, Kang Y, Park H, et al. Sonographic appearance of steatocystoma: an analysis of 14 pathologically confirmed lesions. Taehan Yongsang Uihakhoe Chi. 2021;82:382-392.

- Varshney M, Aziz M, Maheshwari V, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0420114165.

- Tsai MH, Hsiao YP, Lin WL, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex as initial impression of non-small cell lung cancer with complete response to gefitinib. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:E5-E9.

- Zussino M, Nazzaro G, Moltrasio C, et al. Coexistence of steatocystoma multiplex and hidradenitis suppurativa: assessment of this unique association by means of ultrasonography and color Doppler. Skin Res Technol. 2019;25:877-880.

- Whittle C, Silva-Hirschberg C, Loyola K, et al. Ultrasonographic spectrum of cutaneous cysts with stratified squamous epithelium in pediatric dermatology: pictorial essay. J Ultrasound Med. 2023;42:923-930.

- Arceu M, Martinez G, Alfaro D, et al. Ultrasound morphologic features of steatocystoma multiplex with clinical correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39:2255-2260.

- Reick-Mitrisin V, Reddy A, Shah BA. A breast imaging case of steatocystoma multiplex: a rare condition involving multiple anatomic regions. Cureus. 2022;14:E27756.

- Yoon H, Kang Y, Park H, et al. Sonographic appearance of steatocystoma: an analysis of 14 pathologically confirmed lesions. Taehan Yongsang Uihakhoe Chi. 2021;82:382-392.

- Apaydin R, Bilen N, Bayramgurler D, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum: oral isotretinoin treatment combined with cryotherapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:98-100.

- Sharma A, Agrawal S, Dhurat R, et al. An unusual case of facial steatocystoma multiplex: a clinicopathologic and dermoscopic report. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:58-63.

- Moritz DL, Silverman RA. Steatocystoma multiplex treated with isotretinoin: a delayed response. Cutis. 1988;42:437-439.

- Schwartz JL, Goldsmith LA. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum: treatment with isotretinoin. Cutis. 1984;34:149-153.

- Kim SJ, Park HJ, Oh ST, et al. A case of steatocystoma multiplex limited to the scalp. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:106-109.

- Fekete GL, Fekete JE. Steatocystoma multiplex generalisata partially suppurativa--case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2010;18:114-119.

- Choudhary S, Koley S, Salodkar A. A modified surgical technique for steatocystoma multiplex. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3:25-28.

- Kaya TI, Ikizoglu G, Kokturk A, et al. A simple surgical technique for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:785-788.

- Oertel YC, Scott DM. Cytologic-pathologic correlations: fine needle aspiration of three cases of steatocystoma multiplex. Ann Diagn Pathol. 1998;2:318-320.

- Egbert BM, Price NM, Segal RJ. Steatocystoma multiplex. Report of a florid case and a review. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:334-335.

- Adams BB, Mutasim DF, Nordlund JJ. Steatocystoma multiplex: a quick removal technique. Cutis. 1999;64:127-130.

- Lee SJ, Choe YS, Park BC, et al. The vein hook successfully used for eradication of steatocystoma multiplex. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:82-84.

- Bettes PSL, Lopes SL, Prestes MA, et al. Treatment of a facial variant of the multiple steatocystoma with skin graft: case report. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 1998;13:31-36

- Düzova AN, Sentürk GB. Suggestion for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex located exclusively on the face. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:60-62. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02068.x

- Choudhary S, Koley S, Salodkar A. A modified surgical technique for steatocystoma multiplex. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3:25-28.

- Kaya TI, Ikizoglu G, Kokturk A, et al. A simple surgical technique for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:785-788.

- Bakkour W, Madan V. Carbon dioxide laser perforation and extirpation of steatocystoma multiplex. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:658-662.

- Mumcuog?lu CT, Gurel MS, Kiremitci U, et al. Er: yag laser therapy for steatocystoma multiplex. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:300-301.

- Moody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH, et al. 1,450-nm diode laser in combination with the 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(7 Pt 1):1104-1106.

- Cheon DU, Ko JY. 1927-nm fiber-optic diode laser: a novel therapeutic option for facial steatocystoma multiplex. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:1326-1329.

- Kim KT, Sun H, Chung EH. Comparison of complete surgical excision and minimally invasive excision using CO2 laser for removal of epidermal cysts on the face. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2019;20:84-88.

- Kassira S, Korta DZ, de Feraudy S, et al. Fractionated ablative carbon dioxide laser treatment of steatocystoma multiplex. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:364-366.

- Dixit N, Sardana K, Paliwal P. The rationale of ideal pulse duration and pulse interval in the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex using the carbon dioxide laser in a super-pulse mode as opposedto the ultra-pulse mode. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:454-456.

- Santana CN, Pereira DD, Lisboa AP, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa: case report of a rare condition. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):51-53.

- Atzori L, Zanniello R, Pilloni L, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa associated with hidradenitis suppurativa successfully treated with adalimumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(Suppl 6):42-44.

- Jamieson WA. Case of numerous cutaneous cysts scattered over the body. Edinb Med J. 1873;19:223-225.

- Kamra HT, Gadgil PA, Ovhal AG, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex-a rare genetic disorder: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:166-168.

- Brownstein MH. Steatocystoma simplex. A solitary steatocystoma. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:409-411.

- McDonald RM, Reed WB. Natal teeth and steatocystoma multiplex complicated by hidradenitis suppurativa. A new syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1132-1134.

- Plewig G, Wolff HH, Braun-Falco O. Steatocystoma multiplex: anatomic reevaluation, electron microscopy, and autoradiography. Arch Dermatol. 1982;272:363-380.

- Fletcher J, Posso-De Los Rios C, Jambrosic J, A, et al. Coexistence of hidradenitis suppurativa and steatocystoma multiplex: is it a new variant of hidradenitis suppurativa? J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:586-590.

- Cho S, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinical and histologic features of 64 cases of steatocystoma multiplex. J Dermatol. 2002;29:152-156.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480.

- Liu Q, Wu W, Lu J, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex is associated with the R94C mutation in the KRTl7 gene. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5072-5076.

- Yang L, Zhang S, Wang G. Keratin 17 in disease pathogenesis: from cancer to dermatoses. J Pathol. 2019;247:158-165.

- Shamloul G, Khachemoune A. An updated review of the sebaceous gland and its role in health and diseases Part 1: embryology, evolution, structure, and function of sebaceous glands. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:e14695.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kircik LH, Stein Gold L, et al. Androgens, androgen receptors, and the skin: from the laboratory to the clinic with emphasis on clinical and therapeutic implications. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:30-35.

- Porras Fimbres DC, Wolfe SA, Kelley CE. Proliferation of steatocystomas in 2 transgender men. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;26:70-72.

- Marasca C, Megna M, Donnarumma M, et al. A case of steatocystoma multiplex in a psoriatic patient during treatment with anti-IL-12/23. Skin Appendage Disord. 2020;6:309-311.

- Gordon Spratt EA, Kaplan J, Patel RR, et al. Steatocystoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20721.

- Sharma A, Agrawal S, Dhurat R, et al. An unusual case of facial steatocystoma multiplex: a clinicopathologic and dermoscopic report. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:58-63.

- Rahman MH, Islam MS, Ansari NP. Atypical steatocystoma multiplex with calcification. ISRN Dermatol. 2011;2011:381901.

- Beyer AV, Vossmann D. Steatocystoma multiplex. Article in German. Hautarzt. 1996;47:469-471.

- Yanagi T, Matsumura T. Steatocystoma multiplex presenting as acral subcutaneous nodules. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:374-375.

- Marzano AV, Tavecchio S, Balice Y, et al. Acral subcutaneous steatocystoma multiplex: a distinct subtype of the disease? Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:198-201.

- Ferrandiz C, Peyri J. Steatocystoma multiplex. Article in Spanish. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1984;12:173-176.

- Alotaibi L, Alsaif M, Alhumidi A, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa: a case with unusual giant cysts over the scalp and neck. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:71-76.

- Kim SJ, Park HJ, Oh ST, et al. A case of steatocystoma multiplex limited to scalp. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:106-109.

- Patrizi A, Neri I, Guerrini V, et al. Persistent milia, steatocystoma multiplex and eruptive vellus hair cysts: variable expression of multiple pilosebaceous cysts within an affected family. Dermatology. 1998;196:392-396.

- Tomková H, Fujimoto W, Arata J. Expression of keratins (K10 and K17) in steatocystoma multiplex, eruptive vellus hair cysts, and epidermoid and trichilemmal cysts. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:250-253.

- Patokar AS, Holani AR, Khandait GH, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: an underdiagnosed entity. Int J Trichology. 2022;14:31-33.

- Ohtake N, Kubota Y, Takayama O, et al. Relationship between steatocystoma multiplex and eruptive vellus hair cysts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(5 Pt 2):876-878.

- Yoon H, Kang Y, Park H, et al. Sonographic appearance of steatocystoma: an analysis of 14 pathologically confirmed lesions. Taehan Yongsang Uihakhoe Chi. 2021;82:382-392.

- Varshney M, Aziz M, Maheshwari V, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0420114165.

- Tsai MH, Hsiao YP, Lin WL, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex as initial impression of non-small cell lung cancer with complete response to gefitinib. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:E5-E9.

- Zussino M, Nazzaro G, Moltrasio C, et al. Coexistence of steatocystoma multiplex and hidradenitis suppurativa: assessment of this unique association by means of ultrasonography and color Doppler. Skin Res Technol. 2019;25:877-880.

- Whittle C, Silva-Hirschberg C, Loyola K, et al. Ultrasonographic spectrum of cutaneous cysts with stratified squamous epithelium in pediatric dermatology: pictorial essay. J Ultrasound Med. 2023;42:923-930.

- Arceu M, Martinez G, Alfaro D, et al. Ultrasound morphologic features of steatocystoma multiplex with clinical correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39:2255-2260.

- Reick-Mitrisin V, Reddy A, Shah BA. A breast imaging case of steatocystoma multiplex: a rare condition involving multiple anatomic regions. Cureus. 2022;14:E27756.

- Yoon H, Kang Y, Park H, et al. Sonographic appearance of steatocystoma: an analysis of 14 pathologically confirmed lesions. Taehan Yongsang Uihakhoe Chi. 2021;82:382-392.

- Apaydin R, Bilen N, Bayramgurler D, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum: oral isotretinoin treatment combined with cryotherapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:98-100.

- Sharma A, Agrawal S, Dhurat R, et al. An unusual case of facial steatocystoma multiplex: a clinicopathologic and dermoscopic report. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:58-63.

- Moritz DL, Silverman RA. Steatocystoma multiplex treated with isotretinoin: a delayed response. Cutis. 1988;42:437-439.

- Schwartz JL, Goldsmith LA. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum: treatment with isotretinoin. Cutis. 1984;34:149-153.

- Kim SJ, Park HJ, Oh ST, et al. A case of steatocystoma multiplex limited to the scalp. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:106-109.

- Fekete GL, Fekete JE. Steatocystoma multiplex generalisata partially suppurativa--case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2010;18:114-119.

- Choudhary S, Koley S, Salodkar A. A modified surgical technique for steatocystoma multiplex. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3:25-28.

- Kaya TI, Ikizoglu G, Kokturk A, et al. A simple surgical technique for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:785-788.

- Oertel YC, Scott DM. Cytologic-pathologic correlations: fine needle aspiration of three cases of steatocystoma multiplex. Ann Diagn Pathol. 1998;2:318-320.

- Egbert BM, Price NM, Segal RJ. Steatocystoma multiplex. Report of a florid case and a review. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:334-335.

- Adams BB, Mutasim DF, Nordlund JJ. Steatocystoma multiplex: a quick removal technique. Cutis. 1999;64:127-130.

- Lee SJ, Choe YS, Park BC, et al. The vein hook successfully used for eradication of steatocystoma multiplex. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:82-84.

- Bettes PSL, Lopes SL, Prestes MA, et al. Treatment of a facial variant of the multiple steatocystoma with skin graft: case report. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 1998;13:31-36