User login

ED-to-ED Transfers: Optimizing Patient Safety

Emergency Department (ED)-to-ED transfers are a reality of practice in emergency medicine, and they can certainly present a tall order for ensuring patient safety. Challenges abound in getting the right patient to the right place at the right time by the right transportation method.1 A critically ill patient becomes a metaphorical baton to be passed on, requiring the best care along the way--even when the patient is not completely aware of the reasons for the transfer of care. For some EDs, ED-to-ED transfers have become a common daily occurrence. The realities of freestanding EDs, hospital overcrowding, and subspecialty coverage gaps create challenges in direct hospital admission, necessitating a second ED stop before the patient reaches an appropriate destination and provider for definitive care.

The transfer of a patient is much more complex than arranging and carrying out an ambulance ride across town. If thought of as a process, with pre-transfer planning on the sending end, the transfer itself, and post-transfer assurance of care continuity on the receiving end, the quality of care and patient safety can be elevated. Emergency department-to-ED transfers require careful attention to communication, with important hand-offs between the sending facility, the ambulance personnel, and the receiving facility. To lead the discussion around the perils of interhospital ED-to-ED transfers, the following case reports illustrate some of the challenges encountered.

Case Scenarios

Case 1

A 58-year-old man presented to a freestanding ED at 10:30

The nursing staff obtained intravenous (IV) access, and blood samples were drawn. Parenteral pain control and antiemetics were administered while a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was emergently in progress. Meanwhile, the laboratory test results included the following: lactate, 3.8 mmol/L; lipase 42 U/L; carbon monoxide, 14 mmol/L; white blood cell count (WBC), 12 x 109/L without bandemia; serum creatinine, 1.0 mg/dL; liver function tests with a mild elevation of transaminases; and normal coagulation studies.

After reviewing the CT scan, the radiologist called to report a hyperdensity in the lumen of the superior mesenteric artery, which might represent a subsegmental dissection or a partial occlusion or plaque, with no radiographic evidence of bowel ischemia. Vascular surgery service was consulted, and the decision to start IV heparin was agreed upon. The vascular surgeon requested that a mesenteric peripheral vascular laboratory examination (PVL) be arranged on arrival at the hospital ED, and an ED-to-ED transfer to the hospital was arranged. The case was discussed with the receiving day shift emergency physician (EP), who planned to order the mesenteric PVL immediately upon the patient’s arrival.

Emergent transportation via an advanced life support (ALS) ambulance was arranged. The nursing report was called in to the hospital ED at noon, and the ALS unit had arrived and was ready to transfer the patient. Repeat vital signs were obtained, revealing an HR of 45 beats/min and a BP of 200/100 mm Hg.

After an uneventful transport, the patient arrived at the hospital ED at 12:45

Case Commentary

In this case, when the nursing assessment preceding transfer revealed sustained abnormal vital signs particularly the significant hypertension, reassessment and blood pressure management by the sending EP prior to transport may have diminished the poor outcome resulting from the intracranial hemorrhage. Ideally, BP control should have been implemented prior to transport—especially in the context of possible arterial dissection/occlusion with ongoing anticoagulation therapy. If such attempts to control BP prior to transport prove inadequate, a hand-off communication with the receiving EP is indicated, emphasizing the need for immediate evaluation and critical intervention upon patient arrival. On the receiving end of a patient transfer, it is good practice that all critically ill or injured patients be immediately assessed upon arrival at the ED, regardless of planned interventions by any other department.

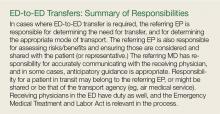

Transport from another ED cannot mislead to a false sense of security that ED care is completed. Patients geographically located in the ED (especially those who are newly arrived) are the responsibility of the ED providers until that point where the next specialist provider clearly assumes care of the patient (see “ED-to-ED Transfers: Summary of Responsibilities”). This point in handoff time can be murky and unclear; yet, as illustrated by this case, it is best to re-evaluate and ensure appropriate emergency care of the patient upon arrival. In addition, as with any other ED patient with a change in condition, timely re-evaluation of the transferred patient is indicated upon receiving the report from nursing that the patient’s condition had changed.

Transfers between EDs should be viewed as a process, and that each phase in the process is important—from the pre-transfer preparation at the sending facility, the physical transfer itself by transport personnel, and the post-transfer arrival that requires the receiving facility to ensure care continues seamlessly and appropriately. Even in situations of high acuity and/or high volume, anticipation and timely attention is required by the receiving staff to ensure continuity of safe patient care. The metaphorical baton was dropped in this transfer.

Opportunities for Patient Safety Improvement. The sending facility should always address any abnormal vital signs prior to patient transfer. The receiving facility should evaluate all transferred patients at the bedside as soon as possible upon arrival. Both facilities should take timely advantage of the information the nurses provide, especially when there is a change in the patient’s condition. All involved physicians from the sending facility should communicate to the receiving ED staff critical and potentially critical patient care information and concerns that pose a risk of deterioration of the patient’s condition.

Case 2

A 23-year-old woman presented to a community hospital ED with a sore throat, fever, and difficulty swallowing. The PA on duty saw the patient in the fast track section of the ED. The patient reported the sore throat had been persistent for the past 3 days, and that she began having difficulty swallowing the day of presentation. Her reported temperature at home was 102°F, but the patient said she had been unable to take acetaminophen or ibuprofen because it was too painful to swallow. The patient had no significant medical history and reported no known recent streptococcal exposure. She denied alcohol use, but admitted to smoking an average of 10 cigarettes per day.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: HR, 92 beats/min; RR, 11 breaths/min; BP, 122/65 mm Hg; and T, 99.5°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. She was not drooling or tripoding. Throat examination revealed posterior oropharyngeal erythema, edema, and exudate, with a uvula displaced to the left with a right-sided asymmetric tonsillar swelling consistent with a significant peritonsillar abscess. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Rapid strep and monospot testing were negative; the patient’s WBC was 9.1 x 109/L with a normal differential. After discussion with the attending EP, an IV line was started, and clindamycin 900 mg and dexamethasone 10 mg were administered. Arrangements were made with the university hospital ED for ALS ambulance transfer, as there were no otolaryngologist services available at the community hospital.

Upon arrival, the patient was examined by the university attending EP and was found to have mild asymmetry of the tonsils, but no midline disruption or uvula shift. The patient was given advice on symptomatic management and was discharged home.

Case Commentary

It is likely that transfer of this patient and its inherent risks could have been averted had the community EP personally assessed the patient prior to transfer arrangements. Supervision of physician extenders and residents in the ED may present challenges to patient safety, diagnostic accuracy, and appropriate treatment, especially in this era of volume and time-driven throughput metrics.

Emergency department transfers are costly and place patients and transport staff at a certain degree of risk. Both ground and air transfer include the possibility of collision, and ED-to-ED transfers should be reserved only for patients who need it. Furthermore, inappropriate transfers remove a transport vehicle and team from use by another patient in true need, resulting in added cost for no value to the patient, and negatively impact the receiving EP, who is left to answer the patient’s questions regarding why they had to be transferred.

An additional point to consider is the management of patient’s expectations when they are being transferred to a facility for more specialized care. At times, patients are led to believe they are being transferred for a certain test or procedure, yet when they arrive at the receiving facility, it is determined that intervention is no longer needed. Better patient communication on the part of the sending facility could help lessen the burden to the staff of the receiving facility when they need to explain why a certain test or procedure was actually not needed, despite the patient’s transfer. This is especially important in rare circumstances when the sending facility is staffed only by a PA or NP and not an ED attending.

Opportunities for Patient Safety Improvement. Active involvement of supervising attending physicians can mitigate the risk of inappropriate ED-to-ED transfers. The active supervisory role of attending EPs in patient care administered by physician extenders and residents is a serious responsibility that deserves priority. Communication with patients regarding their expectations should be initiated by the sending ED provider prior to transport.

Case 3

A primigravid 19-year-old woman at 24 weeks gestation with no prior prenatal care presented to a community hospital ED at 1:50

Since this community hospital had closed its obstetrical unit and moved all obstetrical and pediatric services to a sister hospital approximately 9 miles (13 minutes) away, the EP on duty immediately started IV fluids, ordered fetal heart tones (there was no fetal monitoring capability in the hospital), paged the obstetrician (OB) at the sister hospital, and activated an ALS ground transfer unit, all in parallel sequence. The OB on duty returned the page at 2:20

The discussion between the OB and EP included the risks and benefits of immediate transfer in the antenatal period versus the postpartum period; from the perspective of the EP, who had no access to safe fetal monitoring, labor and delivery support, or neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)/pediatric services, such transport was indicated. The EP felt strongly that the benefit of antenatal transfer outweighed the risk of delivering a late second-trimester fetus in an unsupported environment. However, the OB remained firm in his stance, and stated the patient was unstable and therefore could not be transferred under the law.

Hospital administration at the receiving hospital was paged to assist. The hospital administrator on duty returned the EP’s call at 2:57

The specialized pediatric transport team, with medical control from the pediatric hospital, arrived to transport the premature neonate in critical condition. Care was transferred to the transport team, but while preparing to load the patient into the transport incubator, the team questioned the position of the ET tube; they decided to extubate and reintubate the patient using their specialized equipment. The EP was not made aware of this decision. Unfortunately, after extubation, the transport team was unable to reintubate the neonate, who went into cardiopulmonary arrest and expired in the ED.

Case Commentary

Obstetrical emergencies are challenging even in a fully supported ED, and these challenges are heightened significantly in EDs that lack obstetric and pediatric support. In retrospect, it is truly difficult to determine if any action could or would have altered the outcome of this case.

In some circumstances, determining that a patient is “stable for transfer” or that the benefits of a transfer outweigh the risks is complicated and difficult. In this case, the patient was never “stable,” as she was in active labor. The EMTALA statute and its provisions govern when and how a patient may be transferred from one hospital to another when an unstable medical condition exists, but does not prohibit transferring an unstable patient. The OB’s understanding of the law was mistaken by the assumption that the patient was unstable and therefore could not be transferred at all.2 The essential provisions of the statute state that any patient who comes to the ED requesting examination or treatment for a medical condition must be provided with an appropriate medical screening examination to determine if (s)he is suffering from an emergency medical condition.3 If (s)he is, then the hospital is obligated to either provide him/her with treatment until (s)he is stable or transfer him/her to another hospital that has the capability to provide definitive care for the patient, and the benefit of transfer for this stabilizing care outweighs the risk of the transfer.3

Under the circumstances of this case scenario, it seems reasonable to transfer a pregnant patient in labor if the transferring physician felt that the safety of both mother and baby would be best served at the receiving hospital with specialized services and that the timing of the transfer was appropriate, considering the clinical findings and distance to the receiving hospital—with anticipation that delivery is most likely to occur after arrival at the receiving hospital.4 Again, this is a very complex situation, and the possibility exists that if the transfer proceeds, delivery could occur in the ambulance, which may introduce an additional potentially adverse event.

There is no time to delay in this decision-making process, and the risks and benefits of transfer are not clearly defined. The additional circumstance of an extremely preterm infant who will require specialized NICU care augments the need for expeditious transport to the sister hospital, as contrasted with active labor in a full-term gestation.

Part of EMTALA states “hospitals with specialized capabilities are obligated to accept transfers from hospitals who lack the capability to treat unstable emergency medical conditions.” In this case, the risk of delivering such a preterm infant at a hospital not equipped with even basic obstetrical and pediatric services may outweigh any potential risks of transport to a sister hospital 13 minutes away by ground transport. To mitigate the risk of an in-transit delivery, supporting the transport team with a physician or registered nurse to ride along may have been an option.

Finally, delivery of the premature newborn created a second unstable patient in even greater danger than the mother. Interhospital transfers of critically ill and injured pediatric patients to pediatric hospitals often involve specialized transfer units staffed by expertly trained paramedic and/or nurse teams under the medical control of the pediatric hospital. The unfortunate outcome of this premature infant may have been the ultimate outcome at 24 weeks, despite the extubation and inability of the team to re-intubate. However, communication with the EP in the department in the decision to change the ET tube may have been helpful to the team in the face of a difficult re-intubation.

Opportunities for Patient Safety Improvement. A solid understanding of the EMTALA statute and its provisions is essential not only for providers in the ED, but also for consultants who must understand their responsibilities under the law. Timely transfer arrangements cannot be underestimated, and hospital policy should support expeditious positive responses in emergent situations. Active communication between the sending EP and transport team while still in the ED is prudent.

Conclusion

Interhospital ED-to-ED transfers are frequent occurrences in many EDs. An ED-to-ED transfer of a patient is a process that often involves complex decision-making and a rapid but thorough assessment of the potential risks and benefits. At each stage of the transfer process, each party involved must anticipate, to best degree possible, patient risks and communicate these risks clearly from the pretransfer phase to the transfer team and to the receiving facility. Assurance of the six aims of the Institute of Medicine5 are central to good decision-making that leads to an appropriate disposition of patient transfer to another ED. These aims demand that care delivered is safe, timely, effective, patient-centered, efficient, and equitable.5 When interhospital ED-to-ED transfer is deemed necessary, the sending provider generally is responsible for making certain the right care at the right time is safeguarded from the time the patient enters the ED until he arrives at the receiving ED. The receiving ED then completely assumes the responsibility to evaluate and manage the patient until the definitive caregiver takes over.

1. Appropriate Interfacility Patient Transfer. ACEP Clinical Policy. https://www.acep.org/clinical---practice-management/appropriate-interfacility-patient-transfer/. Accessed December 14, 2016.

2. Frequently Asked Questions About The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act. http://www.emtala.com/faq.htm Accessed January 14, 2017.

3. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act, as established under the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) of 1985 (42 USC 1395 dd) and 42 CFR 489.24; 42 CFR489.20 (EMTALA regulations).

4. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion. Hospital Based Triage of Obstetric Patients. http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Hospital-Based-Triage-of-Obstetric-Patients. Accessed January 19, 2017.

5. Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality in Healthcare in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

Emergency Department (ED)-to-ED transfers are a reality of practice in emergency medicine, and they can certainly present a tall order for ensuring patient safety. Challenges abound in getting the right patient to the right place at the right time by the right transportation method.1 A critically ill patient becomes a metaphorical baton to be passed on, requiring the best care along the way--even when the patient is not completely aware of the reasons for the transfer of care. For some EDs, ED-to-ED transfers have become a common daily occurrence. The realities of freestanding EDs, hospital overcrowding, and subspecialty coverage gaps create challenges in direct hospital admission, necessitating a second ED stop before the patient reaches an appropriate destination and provider for definitive care.

The transfer of a patient is much more complex than arranging and carrying out an ambulance ride across town. If thought of as a process, with pre-transfer planning on the sending end, the transfer itself, and post-transfer assurance of care continuity on the receiving end, the quality of care and patient safety can be elevated. Emergency department-to-ED transfers require careful attention to communication, with important hand-offs between the sending facility, the ambulance personnel, and the receiving facility. To lead the discussion around the perils of interhospital ED-to-ED transfers, the following case reports illustrate some of the challenges encountered.

Case Scenarios

Case 1

A 58-year-old man presented to a freestanding ED at 10:30

The nursing staff obtained intravenous (IV) access, and blood samples were drawn. Parenteral pain control and antiemetics were administered while a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was emergently in progress. Meanwhile, the laboratory test results included the following: lactate, 3.8 mmol/L; lipase 42 U/L; carbon monoxide, 14 mmol/L; white blood cell count (WBC), 12 x 109/L without bandemia; serum creatinine, 1.0 mg/dL; liver function tests with a mild elevation of transaminases; and normal coagulation studies.

After reviewing the CT scan, the radiologist called to report a hyperdensity in the lumen of the superior mesenteric artery, which might represent a subsegmental dissection or a partial occlusion or plaque, with no radiographic evidence of bowel ischemia. Vascular surgery service was consulted, and the decision to start IV heparin was agreed upon. The vascular surgeon requested that a mesenteric peripheral vascular laboratory examination (PVL) be arranged on arrival at the hospital ED, and an ED-to-ED transfer to the hospital was arranged. The case was discussed with the receiving day shift emergency physician (EP), who planned to order the mesenteric PVL immediately upon the patient’s arrival.

Emergent transportation via an advanced life support (ALS) ambulance was arranged. The nursing report was called in to the hospital ED at noon, and the ALS unit had arrived and was ready to transfer the patient. Repeat vital signs were obtained, revealing an HR of 45 beats/min and a BP of 200/100 mm Hg.

After an uneventful transport, the patient arrived at the hospital ED at 12:45

Case Commentary

In this case, when the nursing assessment preceding transfer revealed sustained abnormal vital signs particularly the significant hypertension, reassessment and blood pressure management by the sending EP prior to transport may have diminished the poor outcome resulting from the intracranial hemorrhage. Ideally, BP control should have been implemented prior to transport—especially in the context of possible arterial dissection/occlusion with ongoing anticoagulation therapy. If such attempts to control BP prior to transport prove inadequate, a hand-off communication with the receiving EP is indicated, emphasizing the need for immediate evaluation and critical intervention upon patient arrival. On the receiving end of a patient transfer, it is good practice that all critically ill or injured patients be immediately assessed upon arrival at the ED, regardless of planned interventions by any other department.

Transport from another ED cannot mislead to a false sense of security that ED care is completed. Patients geographically located in the ED (especially those who are newly arrived) are the responsibility of the ED providers until that point where the next specialist provider clearly assumes care of the patient (see “ED-to-ED Transfers: Summary of Responsibilities”). This point in handoff time can be murky and unclear; yet, as illustrated by this case, it is best to re-evaluate and ensure appropriate emergency care of the patient upon arrival. In addition, as with any other ED patient with a change in condition, timely re-evaluation of the transferred patient is indicated upon receiving the report from nursing that the patient’s condition had changed.

Transfers between EDs should be viewed as a process, and that each phase in the process is important—from the pre-transfer preparation at the sending facility, the physical transfer itself by transport personnel, and the post-transfer arrival that requires the receiving facility to ensure care continues seamlessly and appropriately. Even in situations of high acuity and/or high volume, anticipation and timely attention is required by the receiving staff to ensure continuity of safe patient care. The metaphorical baton was dropped in this transfer.

Opportunities for Patient Safety Improvement. The sending facility should always address any abnormal vital signs prior to patient transfer. The receiving facility should evaluate all transferred patients at the bedside as soon as possible upon arrival. Both facilities should take timely advantage of the information the nurses provide, especially when there is a change in the patient’s condition. All involved physicians from the sending facility should communicate to the receiving ED staff critical and potentially critical patient care information and concerns that pose a risk of deterioration of the patient’s condition.

Case 2

A 23-year-old woman presented to a community hospital ED with a sore throat, fever, and difficulty swallowing. The PA on duty saw the patient in the fast track section of the ED. The patient reported the sore throat had been persistent for the past 3 days, and that she began having difficulty swallowing the day of presentation. Her reported temperature at home was 102°F, but the patient said she had been unable to take acetaminophen or ibuprofen because it was too painful to swallow. The patient had no significant medical history and reported no known recent streptococcal exposure. She denied alcohol use, but admitted to smoking an average of 10 cigarettes per day.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: HR, 92 beats/min; RR, 11 breaths/min; BP, 122/65 mm Hg; and T, 99.5°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. She was not drooling or tripoding. Throat examination revealed posterior oropharyngeal erythema, edema, and exudate, with a uvula displaced to the left with a right-sided asymmetric tonsillar swelling consistent with a significant peritonsillar abscess. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Rapid strep and monospot testing were negative; the patient’s WBC was 9.1 x 109/L with a normal differential. After discussion with the attending EP, an IV line was started, and clindamycin 900 mg and dexamethasone 10 mg were administered. Arrangements were made with the university hospital ED for ALS ambulance transfer, as there were no otolaryngologist services available at the community hospital.

Upon arrival, the patient was examined by the university attending EP and was found to have mild asymmetry of the tonsils, but no midline disruption or uvula shift. The patient was given advice on symptomatic management and was discharged home.

Case Commentary

It is likely that transfer of this patient and its inherent risks could have been averted had the community EP personally assessed the patient prior to transfer arrangements. Supervision of physician extenders and residents in the ED may present challenges to patient safety, diagnostic accuracy, and appropriate treatment, especially in this era of volume and time-driven throughput metrics.

Emergency department transfers are costly and place patients and transport staff at a certain degree of risk. Both ground and air transfer include the possibility of collision, and ED-to-ED transfers should be reserved only for patients who need it. Furthermore, inappropriate transfers remove a transport vehicle and team from use by another patient in true need, resulting in added cost for no value to the patient, and negatively impact the receiving EP, who is left to answer the patient’s questions regarding why they had to be transferred.

An additional point to consider is the management of patient’s expectations when they are being transferred to a facility for more specialized care. At times, patients are led to believe they are being transferred for a certain test or procedure, yet when they arrive at the receiving facility, it is determined that intervention is no longer needed. Better patient communication on the part of the sending facility could help lessen the burden to the staff of the receiving facility when they need to explain why a certain test or procedure was actually not needed, despite the patient’s transfer. This is especially important in rare circumstances when the sending facility is staffed only by a PA or NP and not an ED attending.

Opportunities for Patient Safety Improvement. Active involvement of supervising attending physicians can mitigate the risk of inappropriate ED-to-ED transfers. The active supervisory role of attending EPs in patient care administered by physician extenders and residents is a serious responsibility that deserves priority. Communication with patients regarding their expectations should be initiated by the sending ED provider prior to transport.

Case 3

A primigravid 19-year-old woman at 24 weeks gestation with no prior prenatal care presented to a community hospital ED at 1:50

Since this community hospital had closed its obstetrical unit and moved all obstetrical and pediatric services to a sister hospital approximately 9 miles (13 minutes) away, the EP on duty immediately started IV fluids, ordered fetal heart tones (there was no fetal monitoring capability in the hospital), paged the obstetrician (OB) at the sister hospital, and activated an ALS ground transfer unit, all in parallel sequence. The OB on duty returned the page at 2:20

The discussion between the OB and EP included the risks and benefits of immediate transfer in the antenatal period versus the postpartum period; from the perspective of the EP, who had no access to safe fetal monitoring, labor and delivery support, or neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)/pediatric services, such transport was indicated. The EP felt strongly that the benefit of antenatal transfer outweighed the risk of delivering a late second-trimester fetus in an unsupported environment. However, the OB remained firm in his stance, and stated the patient was unstable and therefore could not be transferred under the law.

Hospital administration at the receiving hospital was paged to assist. The hospital administrator on duty returned the EP’s call at 2:57

The specialized pediatric transport team, with medical control from the pediatric hospital, arrived to transport the premature neonate in critical condition. Care was transferred to the transport team, but while preparing to load the patient into the transport incubator, the team questioned the position of the ET tube; they decided to extubate and reintubate the patient using their specialized equipment. The EP was not made aware of this decision. Unfortunately, after extubation, the transport team was unable to reintubate the neonate, who went into cardiopulmonary arrest and expired in the ED.

Case Commentary

Obstetrical emergencies are challenging even in a fully supported ED, and these challenges are heightened significantly in EDs that lack obstetric and pediatric support. In retrospect, it is truly difficult to determine if any action could or would have altered the outcome of this case.

In some circumstances, determining that a patient is “stable for transfer” or that the benefits of a transfer outweigh the risks is complicated and difficult. In this case, the patient was never “stable,” as she was in active labor. The EMTALA statute and its provisions govern when and how a patient may be transferred from one hospital to another when an unstable medical condition exists, but does not prohibit transferring an unstable patient. The OB’s understanding of the law was mistaken by the assumption that the patient was unstable and therefore could not be transferred at all.2 The essential provisions of the statute state that any patient who comes to the ED requesting examination or treatment for a medical condition must be provided with an appropriate medical screening examination to determine if (s)he is suffering from an emergency medical condition.3 If (s)he is, then the hospital is obligated to either provide him/her with treatment until (s)he is stable or transfer him/her to another hospital that has the capability to provide definitive care for the patient, and the benefit of transfer for this stabilizing care outweighs the risk of the transfer.3

Under the circumstances of this case scenario, it seems reasonable to transfer a pregnant patient in labor if the transferring physician felt that the safety of both mother and baby would be best served at the receiving hospital with specialized services and that the timing of the transfer was appropriate, considering the clinical findings and distance to the receiving hospital—with anticipation that delivery is most likely to occur after arrival at the receiving hospital.4 Again, this is a very complex situation, and the possibility exists that if the transfer proceeds, delivery could occur in the ambulance, which may introduce an additional potentially adverse event.

There is no time to delay in this decision-making process, and the risks and benefits of transfer are not clearly defined. The additional circumstance of an extremely preterm infant who will require specialized NICU care augments the need for expeditious transport to the sister hospital, as contrasted with active labor in a full-term gestation.

Part of EMTALA states “hospitals with specialized capabilities are obligated to accept transfers from hospitals who lack the capability to treat unstable emergency medical conditions.” In this case, the risk of delivering such a preterm infant at a hospital not equipped with even basic obstetrical and pediatric services may outweigh any potential risks of transport to a sister hospital 13 minutes away by ground transport. To mitigate the risk of an in-transit delivery, supporting the transport team with a physician or registered nurse to ride along may have been an option.

Finally, delivery of the premature newborn created a second unstable patient in even greater danger than the mother. Interhospital transfers of critically ill and injured pediatric patients to pediatric hospitals often involve specialized transfer units staffed by expertly trained paramedic and/or nurse teams under the medical control of the pediatric hospital. The unfortunate outcome of this premature infant may have been the ultimate outcome at 24 weeks, despite the extubation and inability of the team to re-intubate. However, communication with the EP in the department in the decision to change the ET tube may have been helpful to the team in the face of a difficult re-intubation.

Opportunities for Patient Safety Improvement. A solid understanding of the EMTALA statute and its provisions is essential not only for providers in the ED, but also for consultants who must understand their responsibilities under the law. Timely transfer arrangements cannot be underestimated, and hospital policy should support expeditious positive responses in emergent situations. Active communication between the sending EP and transport team while still in the ED is prudent.

Conclusion

Interhospital ED-to-ED transfers are frequent occurrences in many EDs. An ED-to-ED transfer of a patient is a process that often involves complex decision-making and a rapid but thorough assessment of the potential risks and benefits. At each stage of the transfer process, each party involved must anticipate, to best degree possible, patient risks and communicate these risks clearly from the pretransfer phase to the transfer team and to the receiving facility. Assurance of the six aims of the Institute of Medicine5 are central to good decision-making that leads to an appropriate disposition of patient transfer to another ED. These aims demand that care delivered is safe, timely, effective, patient-centered, efficient, and equitable.5 When interhospital ED-to-ED transfer is deemed necessary, the sending provider generally is responsible for making certain the right care at the right time is safeguarded from the time the patient enters the ED until he arrives at the receiving ED. The receiving ED then completely assumes the responsibility to evaluate and manage the patient until the definitive caregiver takes over.

Emergency Department (ED)-to-ED transfers are a reality of practice in emergency medicine, and they can certainly present a tall order for ensuring patient safety. Challenges abound in getting the right patient to the right place at the right time by the right transportation method.1 A critically ill patient becomes a metaphorical baton to be passed on, requiring the best care along the way--even when the patient is not completely aware of the reasons for the transfer of care. For some EDs, ED-to-ED transfers have become a common daily occurrence. The realities of freestanding EDs, hospital overcrowding, and subspecialty coverage gaps create challenges in direct hospital admission, necessitating a second ED stop before the patient reaches an appropriate destination and provider for definitive care.

The transfer of a patient is much more complex than arranging and carrying out an ambulance ride across town. If thought of as a process, with pre-transfer planning on the sending end, the transfer itself, and post-transfer assurance of care continuity on the receiving end, the quality of care and patient safety can be elevated. Emergency department-to-ED transfers require careful attention to communication, with important hand-offs between the sending facility, the ambulance personnel, and the receiving facility. To lead the discussion around the perils of interhospital ED-to-ED transfers, the following case reports illustrate some of the challenges encountered.

Case Scenarios

Case 1

A 58-year-old man presented to a freestanding ED at 10:30

The nursing staff obtained intravenous (IV) access, and blood samples were drawn. Parenteral pain control and antiemetics were administered while a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was emergently in progress. Meanwhile, the laboratory test results included the following: lactate, 3.8 mmol/L; lipase 42 U/L; carbon monoxide, 14 mmol/L; white blood cell count (WBC), 12 x 109/L without bandemia; serum creatinine, 1.0 mg/dL; liver function tests with a mild elevation of transaminases; and normal coagulation studies.

After reviewing the CT scan, the radiologist called to report a hyperdensity in the lumen of the superior mesenteric artery, which might represent a subsegmental dissection or a partial occlusion or plaque, with no radiographic evidence of bowel ischemia. Vascular surgery service was consulted, and the decision to start IV heparin was agreed upon. The vascular surgeon requested that a mesenteric peripheral vascular laboratory examination (PVL) be arranged on arrival at the hospital ED, and an ED-to-ED transfer to the hospital was arranged. The case was discussed with the receiving day shift emergency physician (EP), who planned to order the mesenteric PVL immediately upon the patient’s arrival.

Emergent transportation via an advanced life support (ALS) ambulance was arranged. The nursing report was called in to the hospital ED at noon, and the ALS unit had arrived and was ready to transfer the patient. Repeat vital signs were obtained, revealing an HR of 45 beats/min and a BP of 200/100 mm Hg.

After an uneventful transport, the patient arrived at the hospital ED at 12:45

Case Commentary

In this case, when the nursing assessment preceding transfer revealed sustained abnormal vital signs particularly the significant hypertension, reassessment and blood pressure management by the sending EP prior to transport may have diminished the poor outcome resulting from the intracranial hemorrhage. Ideally, BP control should have been implemented prior to transport—especially in the context of possible arterial dissection/occlusion with ongoing anticoagulation therapy. If such attempts to control BP prior to transport prove inadequate, a hand-off communication with the receiving EP is indicated, emphasizing the need for immediate evaluation and critical intervention upon patient arrival. On the receiving end of a patient transfer, it is good practice that all critically ill or injured patients be immediately assessed upon arrival at the ED, regardless of planned interventions by any other department.

Transport from another ED cannot mislead to a false sense of security that ED care is completed. Patients geographically located in the ED (especially those who are newly arrived) are the responsibility of the ED providers until that point where the next specialist provider clearly assumes care of the patient (see “ED-to-ED Transfers: Summary of Responsibilities”). This point in handoff time can be murky and unclear; yet, as illustrated by this case, it is best to re-evaluate and ensure appropriate emergency care of the patient upon arrival. In addition, as with any other ED patient with a change in condition, timely re-evaluation of the transferred patient is indicated upon receiving the report from nursing that the patient’s condition had changed.

Transfers between EDs should be viewed as a process, and that each phase in the process is important—from the pre-transfer preparation at the sending facility, the physical transfer itself by transport personnel, and the post-transfer arrival that requires the receiving facility to ensure care continues seamlessly and appropriately. Even in situations of high acuity and/or high volume, anticipation and timely attention is required by the receiving staff to ensure continuity of safe patient care. The metaphorical baton was dropped in this transfer.

Opportunities for Patient Safety Improvement. The sending facility should always address any abnormal vital signs prior to patient transfer. The receiving facility should evaluate all transferred patients at the bedside as soon as possible upon arrival. Both facilities should take timely advantage of the information the nurses provide, especially when there is a change in the patient’s condition. All involved physicians from the sending facility should communicate to the receiving ED staff critical and potentially critical patient care information and concerns that pose a risk of deterioration of the patient’s condition.

Case 2

A 23-year-old woman presented to a community hospital ED with a sore throat, fever, and difficulty swallowing. The PA on duty saw the patient in the fast track section of the ED. The patient reported the sore throat had been persistent for the past 3 days, and that she began having difficulty swallowing the day of presentation. Her reported temperature at home was 102°F, but the patient said she had been unable to take acetaminophen or ibuprofen because it was too painful to swallow. The patient had no significant medical history and reported no known recent streptococcal exposure. She denied alcohol use, but admitted to smoking an average of 10 cigarettes per day.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: HR, 92 beats/min; RR, 11 breaths/min; BP, 122/65 mm Hg; and T, 99.5°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. She was not drooling or tripoding. Throat examination revealed posterior oropharyngeal erythema, edema, and exudate, with a uvula displaced to the left with a right-sided asymmetric tonsillar swelling consistent with a significant peritonsillar abscess. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Rapid strep and monospot testing were negative; the patient’s WBC was 9.1 x 109/L with a normal differential. After discussion with the attending EP, an IV line was started, and clindamycin 900 mg and dexamethasone 10 mg were administered. Arrangements were made with the university hospital ED for ALS ambulance transfer, as there were no otolaryngologist services available at the community hospital.

Upon arrival, the patient was examined by the university attending EP and was found to have mild asymmetry of the tonsils, but no midline disruption or uvula shift. The patient was given advice on symptomatic management and was discharged home.

Case Commentary

It is likely that transfer of this patient and its inherent risks could have been averted had the community EP personally assessed the patient prior to transfer arrangements. Supervision of physician extenders and residents in the ED may present challenges to patient safety, diagnostic accuracy, and appropriate treatment, especially in this era of volume and time-driven throughput metrics.

Emergency department transfers are costly and place patients and transport staff at a certain degree of risk. Both ground and air transfer include the possibility of collision, and ED-to-ED transfers should be reserved only for patients who need it. Furthermore, inappropriate transfers remove a transport vehicle and team from use by another patient in true need, resulting in added cost for no value to the patient, and negatively impact the receiving EP, who is left to answer the patient’s questions regarding why they had to be transferred.

An additional point to consider is the management of patient’s expectations when they are being transferred to a facility for more specialized care. At times, patients are led to believe they are being transferred for a certain test or procedure, yet when they arrive at the receiving facility, it is determined that intervention is no longer needed. Better patient communication on the part of the sending facility could help lessen the burden to the staff of the receiving facility when they need to explain why a certain test or procedure was actually not needed, despite the patient’s transfer. This is especially important in rare circumstances when the sending facility is staffed only by a PA or NP and not an ED attending.

Opportunities for Patient Safety Improvement. Active involvement of supervising attending physicians can mitigate the risk of inappropriate ED-to-ED transfers. The active supervisory role of attending EPs in patient care administered by physician extenders and residents is a serious responsibility that deserves priority. Communication with patients regarding their expectations should be initiated by the sending ED provider prior to transport.

Case 3

A primigravid 19-year-old woman at 24 weeks gestation with no prior prenatal care presented to a community hospital ED at 1:50

Since this community hospital had closed its obstetrical unit and moved all obstetrical and pediatric services to a sister hospital approximately 9 miles (13 minutes) away, the EP on duty immediately started IV fluids, ordered fetal heart tones (there was no fetal monitoring capability in the hospital), paged the obstetrician (OB) at the sister hospital, and activated an ALS ground transfer unit, all in parallel sequence. The OB on duty returned the page at 2:20

The discussion between the OB and EP included the risks and benefits of immediate transfer in the antenatal period versus the postpartum period; from the perspective of the EP, who had no access to safe fetal monitoring, labor and delivery support, or neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)/pediatric services, such transport was indicated. The EP felt strongly that the benefit of antenatal transfer outweighed the risk of delivering a late second-trimester fetus in an unsupported environment. However, the OB remained firm in his stance, and stated the patient was unstable and therefore could not be transferred under the law.

Hospital administration at the receiving hospital was paged to assist. The hospital administrator on duty returned the EP’s call at 2:57

The specialized pediatric transport team, with medical control from the pediatric hospital, arrived to transport the premature neonate in critical condition. Care was transferred to the transport team, but while preparing to load the patient into the transport incubator, the team questioned the position of the ET tube; they decided to extubate and reintubate the patient using their specialized equipment. The EP was not made aware of this decision. Unfortunately, after extubation, the transport team was unable to reintubate the neonate, who went into cardiopulmonary arrest and expired in the ED.

Case Commentary

Obstetrical emergencies are challenging even in a fully supported ED, and these challenges are heightened significantly in EDs that lack obstetric and pediatric support. In retrospect, it is truly difficult to determine if any action could or would have altered the outcome of this case.

In some circumstances, determining that a patient is “stable for transfer” or that the benefits of a transfer outweigh the risks is complicated and difficult. In this case, the patient was never “stable,” as she was in active labor. The EMTALA statute and its provisions govern when and how a patient may be transferred from one hospital to another when an unstable medical condition exists, but does not prohibit transferring an unstable patient. The OB’s understanding of the law was mistaken by the assumption that the patient was unstable and therefore could not be transferred at all.2 The essential provisions of the statute state that any patient who comes to the ED requesting examination or treatment for a medical condition must be provided with an appropriate medical screening examination to determine if (s)he is suffering from an emergency medical condition.3 If (s)he is, then the hospital is obligated to either provide him/her with treatment until (s)he is stable or transfer him/her to another hospital that has the capability to provide definitive care for the patient, and the benefit of transfer for this stabilizing care outweighs the risk of the transfer.3

Under the circumstances of this case scenario, it seems reasonable to transfer a pregnant patient in labor if the transferring physician felt that the safety of both mother and baby would be best served at the receiving hospital with specialized services and that the timing of the transfer was appropriate, considering the clinical findings and distance to the receiving hospital—with anticipation that delivery is most likely to occur after arrival at the receiving hospital.4 Again, this is a very complex situation, and the possibility exists that if the transfer proceeds, delivery could occur in the ambulance, which may introduce an additional potentially adverse event.

There is no time to delay in this decision-making process, and the risks and benefits of transfer are not clearly defined. The additional circumstance of an extremely preterm infant who will require specialized NICU care augments the need for expeditious transport to the sister hospital, as contrasted with active labor in a full-term gestation.

Part of EMTALA states “hospitals with specialized capabilities are obligated to accept transfers from hospitals who lack the capability to treat unstable emergency medical conditions.” In this case, the risk of delivering such a preterm infant at a hospital not equipped with even basic obstetrical and pediatric services may outweigh any potential risks of transport to a sister hospital 13 minutes away by ground transport. To mitigate the risk of an in-transit delivery, supporting the transport team with a physician or registered nurse to ride along may have been an option.

Finally, delivery of the premature newborn created a second unstable patient in even greater danger than the mother. Interhospital transfers of critically ill and injured pediatric patients to pediatric hospitals often involve specialized transfer units staffed by expertly trained paramedic and/or nurse teams under the medical control of the pediatric hospital. The unfortunate outcome of this premature infant may have been the ultimate outcome at 24 weeks, despite the extubation and inability of the team to re-intubate. However, communication with the EP in the department in the decision to change the ET tube may have been helpful to the team in the face of a difficult re-intubation.

Opportunities for Patient Safety Improvement. A solid understanding of the EMTALA statute and its provisions is essential not only for providers in the ED, but also for consultants who must understand their responsibilities under the law. Timely transfer arrangements cannot be underestimated, and hospital policy should support expeditious positive responses in emergent situations. Active communication between the sending EP and transport team while still in the ED is prudent.

Conclusion

Interhospital ED-to-ED transfers are frequent occurrences in many EDs. An ED-to-ED transfer of a patient is a process that often involves complex decision-making and a rapid but thorough assessment of the potential risks and benefits. At each stage of the transfer process, each party involved must anticipate, to best degree possible, patient risks and communicate these risks clearly from the pretransfer phase to the transfer team and to the receiving facility. Assurance of the six aims of the Institute of Medicine5 are central to good decision-making that leads to an appropriate disposition of patient transfer to another ED. These aims demand that care delivered is safe, timely, effective, patient-centered, efficient, and equitable.5 When interhospital ED-to-ED transfer is deemed necessary, the sending provider generally is responsible for making certain the right care at the right time is safeguarded from the time the patient enters the ED until he arrives at the receiving ED. The receiving ED then completely assumes the responsibility to evaluate and manage the patient until the definitive caregiver takes over.

1. Appropriate Interfacility Patient Transfer. ACEP Clinical Policy. https://www.acep.org/clinical---practice-management/appropriate-interfacility-patient-transfer/. Accessed December 14, 2016.

2. Frequently Asked Questions About The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act. http://www.emtala.com/faq.htm Accessed January 14, 2017.

3. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act, as established under the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) of 1985 (42 USC 1395 dd) and 42 CFR 489.24; 42 CFR489.20 (EMTALA regulations).

4. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion. Hospital Based Triage of Obstetric Patients. http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Hospital-Based-Triage-of-Obstetric-Patients. Accessed January 19, 2017.

5. Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality in Healthcare in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

1. Appropriate Interfacility Patient Transfer. ACEP Clinical Policy. https://www.acep.org/clinical---practice-management/appropriate-interfacility-patient-transfer/. Accessed December 14, 2016.

2. Frequently Asked Questions About The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act. http://www.emtala.com/faq.htm Accessed January 14, 2017.

3. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act, as established under the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) of 1985 (42 USC 1395 dd) and 42 CFR 489.24; 42 CFR489.20 (EMTALA regulations).

4. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion. Hospital Based Triage of Obstetric Patients. http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Hospital-Based-Triage-of-Obstetric-Patients. Accessed January 19, 2017.

5. Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality in Healthcare in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

Allegations: Current Trends in Medical Malpractice, Part 2

Most medical malpractice cases are still resolved in a courtroom—typically after years of preparation and personal torment. Yet, overall rates of paid medical malpractice claims among all physicians have been steadily decreasing over the past two decades, with reports showing decreases of 30% to 50% in paid claims since 2000.1-3 At the same time, while median payments and insurance premiums continued to increase until the mid-2000s, they now appear to have plateaued.1

None of these changes occurred in isolation. More than 30 states now have caps on noneconomic or total damages.2 As noted in part 1, since 2000, some states have enacted comprehensive tort reform.4 However, whether these changes in malpractice patterns can be attributed directly to specific policy changes remains a hotly contested issue.

Malpractice Risk in Emergency Medicine

To what extent do the trends in medical malpractice apply to emergency medicine (EM)? While emergency physicians’ (EPs’) perception of malpractice risk ranks higher than any other medical specialty,5 in a review of a large sample of malpractice claims from 1991 through 2005, EPs ranked in the middle among specialties with respect to annual risk of a malpractice claim.6 Moreover, the annual risk of a claim for EPs is just under 8%, compared to 7.4% for all physicians. Yet, for neurosurgery and cardiothoracic surgery—the specialties with the highest overall risk of malpractice claims—the annual risk approaches 20%.6 Regarding payout statistics, less than one-fifth of the claims against EPs resulted in payment.6 In a review of a separate insurance database of closed claims, EPs were named as the primary defendant in only 19% of cases.7

Despite the discrepancies between perceived risk and absolute risk of malpractice claims among EPs, malpractice lawsuits continue to affect the practice of EM. This is evidenced in several surveys, in which the majority of EP participants admitted to practicing “defensive medicine” by ordering tests that were felt to be unnecessary and did so in response to perceived malpractice risk.8-10 Perceived risk also accounts for the significant variation in decision-making in the ED with respect to diagnostic testing and hospitalization of patients.11 One would expect that lowering malpractice risk would result in less so-called unnecessary testing, but whether or not this is truly the case remains to be seen.

Effects of Malpractice Reform

A study by Waxman et al12 on the effects of significant malpractice tort reform in ED care in Texas, Georgia, and South Carolina found no difference in rates of imaging studies, charges, or patient admissions. Furthermore, legislation reform did not increase plaintiff onus to prove proximate “gross negligence” rather than simply a breach from “reasonably skillful and careful” medicine.12 These findings suggest that perception of malpractice risk might simply be serving as a proxy for physicians’ underlying risk tolerance, and be less subject to influence by external forces.

Areas Associated With Malpractice Risk

A number of closed-claim databases attempted to identify the characteristics of patient encounters that can lead to malpractice claims, including patient conditions and sources of error. Diagnostic errors have consistently been found to be the leading cause of malpractice claims, accounting for 28% to 65% of claims, followed by inappropriate management of medical treatment and improper performance of a procedure.7,13-16 A January 2016 benchmarking system report by CRICO Strategies found that 30% of 23,658 medical malpractice claims filed between 2009 through 2013 cited failures in communication as a factor.17 The report also revealed that among these failed communications, those that occurred between health care providers are more likely to result in payout compared to miscommunications between providers and patients.17 This report further noted 70% to 80% of claims closed without payment.7,16 Closed claims were significantly more likely to involve serious injuries or death.7,18 Leading conditions that resulted in claims include myocardial infarction, nonspecific chest pain, symptoms involving the abdomen or pelvis, appendicitis, and orthopedic injuries.7,13,16

Diagnostic Errors

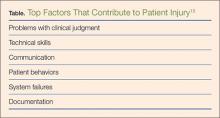

Errors in diagnosis have been attributed to multiple factors in the ED. The two most common factors were failure to order tests and failure to perform an adequate history and physical examination, both of which contribute to rationalization of the practice of defensive medicine under the current tort system.13 Other significant factors associated with errors in diagnosis include misinterpretation of test results or imaging studies and failure to obtain an appropriate consultation. Processes contributing to each of these potential errors include mistakes in judgment, lack of knowledge, miscommunication, and insufficient documentation (Table).15

Strategies for Reducing Malpractice Risk

In part 1, we listed several strategies EPs could adopt to help reduce malpractice risk. In this section, we will discuss in further detail how these strategies help mitigate malpractice claims.

Patient Communication

Open communication with patients is paramount in reducing the risk of a malpractice allegation. Patients are more likely to become angry or frustrated if they sense a physician is not listening to or addressing their concerns. These patients are in turn more likely to file a complaint if they are harmed or experience a bad outcome during their stay in the ED.

Situations in which patients are unable to provide pertinent information also place the EP at significant risk, as the provider must make decisions without full knowledge of the case. Communication with potential resources such as nursing home staff, the patient’s family, and emergency medical service providers to obtain additional information can help reduce risk.

Of course, when evaluating and treating patients, the EP should always take the time to listen to the patient’s concerns during the encounter to ensure his or her needs have been addressed. In the event of a patient allegation or complaint, the EP should make the effort to explore and de-escalate the situation before the patient is discharged.

Discharge Care and Instructions

According to CRICO, premature discharge as a factor in medical malpractice liability results from inadequate assessment and missed opportunities in 41% of diagnosis-related ED cases.16 The following situation illustrates a brief example of such a missed opportunity: A provider makes a diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) in a patient presenting with fever and abdominal pain but whose urinalysis is suspect for contamination and in whom no pelvic examination was performed to rule out other etiologies. When the same patient later returns to the ED with worse abdominal pain, a sterile urine culture invalidates the diagnosis of UTI, and further evaluation leads to a final diagnosis of ruptured appendix.

Prior to discharging any patient, the EP should provide clear and concise at-home care instructions in a manner in which the patient can understand. Clear instructions on how the patient is to manage his or her care after discharge are vital, and failure to do so in terms the patient can understand can create problems if a harmful result occurs. This is especially important in patients with whom there is a communication barrier—eg, language barrier, hearing impairment, cognitive deficit, intoxication, or violent or irrational behavior. In these situations, the EP should always take advantage of available resources and tools such as language lines, interpreters, discharge planners, psychiatric staff, and supportive family members to help reconcile any communication barriers. These measures will in turn optimize patient outcome and reduce the risk of a later malpractice allegation.

Board Certification

All physicians should maintain their respective board certification and specialty training requirements. Efforts in this area help providers to stay up to date in current practice standards and new developments, thus reducing one’s risk of incurring a malpractice claim.

Patient Safety

All members of the care team should engender an environment that is focused on patient safety, including open communication between providers and with nursing staff and technical support teams. Although interruptions can be detrimental to patient care, simply having an understanding of this phenomenon among all staff members can alleviate some of the working stressors in the ED. Effort must be made to create an environment that allows for clarification between nursing staff and physicians without causing undue antagonism. Fostering supportive communication, having a questioning attitude, and seeking clarification can only enhance patient safety.

The importance of the supervisory role of attending physicians to trainees, physician extenders, and nursing staff must be emphasized, and appropriate guidance from the ED attending is germane in keeping patients safe in teaching environments. Additionally, in departments that suffer the burden of high numbers of admitted patient boarders in the ED, attention must be given to the transitional period between decision to admit and termination of ED care and the acquisition of care of the admitting physician. A clear plan of responsibility must be in place for these high-risk situations.

Policies and Procedures

Departmental policies and procedures should be designed to identify and address all late laboratory results data, radiological discrepancies, and culture results in a timely and uniform manner. Since unaddressed results and discrepancies can result in patient harm, patient-callback processes should be designed to reduce risk by addressing these hazards regularly, thoroughly, and in a timely fashion.

Cognitive Biases

An awareness of inherent biases in the medical decision-making process is also helpful to maintain mindfulness in the routine practice of EM and avoid medical errors. The EP should take care not to be influenced by recent events and diagnostic information that is easy to recall or common, and to ensure the differential addresses possibilities beyond the readily available diagnoses. Further, reliance on an existing opinion may be misleading if subsequent judgments are based on this “anchor,” whether it is true or false.

If the data points of the case do not line up as expected, or if there are unexplained outliers, the EP should expand the frame of reference to seek more appropriate possibilities, and avoid attempts to make the data fit a preferred or favored conclusion.

When one fails to recognize that data do not fit the diagnostic presumption, the true diagnosis can be undermined. Such confirmation bias in turn challenges diagnostic success. Hasty judgment without considering and seeking out relevant information can set up diagnostic failure and premature closure.

Remembering the Basics

Finally, providers should follow the basic principles for every patient. Vital signs are vital for a reason, and all abnormal data must be accounted for prior to patient hand off or discharge. Patient turnover is a high-risk occasion, and demands careful attention to case details between the off-going physician, the accepting physician, and the patient.

All patients presenting to the ED for care should leave the ED at their baseline functional level (ie, if they walk independently, they should still walk independently at discharge). If not, the reason should be sought out and clarified with appropriate recommendations for treatment and follow-up.

Patients and staff should always be treated with respect, which in turn will encourage effective communication. Providers should be honest with patients, document truthfully, respect privacy and confidentiality, practice within one’s competence, confirm information, and avoid assumptions. Compassion goes hand in hand with respectful and open communication. Physicians perceived as compassionate and trustworthy are less likely to be the target of a malpractice suit, even when harm has occurred.

Conclusion

Even though the number of paid medical malpractice claims has continued to decrease over the past 20 years, a discrepancy between perceived and absolute risk persists among EPs—one that perpetuates the practice of defensive medicine and continues to affect EM. Despite the current perceptions and climate, EPs can allay their risk of incurring a malpractice claim by employing the strategies outlined above.

1. Mello MM, Studdert DM, Kachalia A. The medical liability climate and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2014;312(20):2146-2155.

2. Paik M, Black B, Hyman DA. The receding tide of medical malpractice: part 1 - national trends. J Empirical Leg Stud. 2013;10(4):612-638.

3. Bishop TF, Ryan AM, Caslino LP. Paid malpractice claims for adverse events in inpatient and outpatient settings. JAMA. 2011;305(23):2427-2431.

4. Kachalia A, Mello MM. New directions in medical liability reform. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):

1564-1572.

5. Carrier ER, Reschovsky JD, Mello MM, Mayrell RC, Katz D. Physicians’ fears of malpractice lawsuits are not assured by tort reforms. Health Aff. 2010;29(9):1585-1592.

6. Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):629-636.

7. Brown TW, McCarthy ML, Kelen GD, Levy F. An epidemiologic study of closed emergency department malpractice claims in a national database of physician malpractice insurers. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):553-560.

8. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609-2617.

9. Bishop TF, Federman AD, Keyhani S. Physicians’ views on defensive medicine: a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(12):1081-1083.

10. Massachusetts Medical Society. Investigation of defensive medicine in Massachusetts. November 2008. Available at http://www.massmed.org/defensivemedicine. Accessed March 16, 2016.

11. Katz DA, Williams GC, Brown RL, et al. Emergency physicians’ fear of malpractice in evaluating patient with possible acute cardiac ischemia. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(6):525-533.

12. Waxman DA, Greenberg MD, Ridgely MS, Kellermann AL, Heaton P. The effect of malpractice reform on emergency department care. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(16):1518-1525.

13. Kachalia A, Gandhi TK, Puopolo AL, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(2):196-205.

14. Saber Tehrani AS, Lee H, Mathews SC, et al. 25-Year summary of US malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986-2010: an analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(8):672-680.

15. Ross J, Ranum D, Troxel DB. Emergency medicine closed claims study. The Doctors Company. Available at http://www.thedoctors.com/ecm/groups/public/@tdc/@web/@kc/@patientsafety/documents/article/con_id_004776.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2016.

16. Ruoff G, ed. 2011 Annual benchmarking report: malpractice risks in emergency medicine. CRICO strategies. 2012. Available at https://www.rmf.harvard.edu/Strategies/Home/Products-and-Services/Comparative-Data/Annual-Benchmark-Reports. Accessed March 16, 2016.

17. Failures in communication contribute to medical malpractice. January 31, 2016. https://www.rmf.harvard.edu/About-CRICO/Media/Press-Releases/News/2016/February/Failures-in-Communication-Contribute-to-Medical-Malpractice.

18. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024-2033. Accessed March 16, 2016.

Most medical malpractice cases are still resolved in a courtroom—typically after years of preparation and personal torment. Yet, overall rates of paid medical malpractice claims among all physicians have been steadily decreasing over the past two decades, with reports showing decreases of 30% to 50% in paid claims since 2000.1-3 At the same time, while median payments and insurance premiums continued to increase until the mid-2000s, they now appear to have plateaued.1

None of these changes occurred in isolation. More than 30 states now have caps on noneconomic or total damages.2 As noted in part 1, since 2000, some states have enacted comprehensive tort reform.4 However, whether these changes in malpractice patterns can be attributed directly to specific policy changes remains a hotly contested issue.

Malpractice Risk in Emergency Medicine

To what extent do the trends in medical malpractice apply to emergency medicine (EM)? While emergency physicians’ (EPs’) perception of malpractice risk ranks higher than any other medical specialty,5 in a review of a large sample of malpractice claims from 1991 through 2005, EPs ranked in the middle among specialties with respect to annual risk of a malpractice claim.6 Moreover, the annual risk of a claim for EPs is just under 8%, compared to 7.4% for all physicians. Yet, for neurosurgery and cardiothoracic surgery—the specialties with the highest overall risk of malpractice claims—the annual risk approaches 20%.6 Regarding payout statistics, less than one-fifth of the claims against EPs resulted in payment.6 In a review of a separate insurance database of closed claims, EPs were named as the primary defendant in only 19% of cases.7

Despite the discrepancies between perceived risk and absolute risk of malpractice claims among EPs, malpractice lawsuits continue to affect the practice of EM. This is evidenced in several surveys, in which the majority of EP participants admitted to practicing “defensive medicine” by ordering tests that were felt to be unnecessary and did so in response to perceived malpractice risk.8-10 Perceived risk also accounts for the significant variation in decision-making in the ED with respect to diagnostic testing and hospitalization of patients.11 One would expect that lowering malpractice risk would result in less so-called unnecessary testing, but whether or not this is truly the case remains to be seen.

Effects of Malpractice Reform

A study by Waxman et al12 on the effects of significant malpractice tort reform in ED care in Texas, Georgia, and South Carolina found no difference in rates of imaging studies, charges, or patient admissions. Furthermore, legislation reform did not increase plaintiff onus to prove proximate “gross negligence” rather than simply a breach from “reasonably skillful and careful” medicine.12 These findings suggest that perception of malpractice risk might simply be serving as a proxy for physicians’ underlying risk tolerance, and be less subject to influence by external forces.

Areas Associated With Malpractice Risk

A number of closed-claim databases attempted to identify the characteristics of patient encounters that can lead to malpractice claims, including patient conditions and sources of error. Diagnostic errors have consistently been found to be the leading cause of malpractice claims, accounting for 28% to 65% of claims, followed by inappropriate management of medical treatment and improper performance of a procedure.7,13-16 A January 2016 benchmarking system report by CRICO Strategies found that 30% of 23,658 medical malpractice claims filed between 2009 through 2013 cited failures in communication as a factor.17 The report also revealed that among these failed communications, those that occurred between health care providers are more likely to result in payout compared to miscommunications between providers and patients.17 This report further noted 70% to 80% of claims closed without payment.7,16 Closed claims were significantly more likely to involve serious injuries or death.7,18 Leading conditions that resulted in claims include myocardial infarction, nonspecific chest pain, symptoms involving the abdomen or pelvis, appendicitis, and orthopedic injuries.7,13,16

Diagnostic Errors

Errors in diagnosis have been attributed to multiple factors in the ED. The two most common factors were failure to order tests and failure to perform an adequate history and physical examination, both of which contribute to rationalization of the practice of defensive medicine under the current tort system.13 Other significant factors associated with errors in diagnosis include misinterpretation of test results or imaging studies and failure to obtain an appropriate consultation. Processes contributing to each of these potential errors include mistakes in judgment, lack of knowledge, miscommunication, and insufficient documentation (Table).15

Strategies for Reducing Malpractice Risk

In part 1, we listed several strategies EPs could adopt to help reduce malpractice risk. In this section, we will discuss in further detail how these strategies help mitigate malpractice claims.

Patient Communication

Open communication with patients is paramount in reducing the risk of a malpractice allegation. Patients are more likely to become angry or frustrated if they sense a physician is not listening to or addressing their concerns. These patients are in turn more likely to file a complaint if they are harmed or experience a bad outcome during their stay in the ED.

Situations in which patients are unable to provide pertinent information also place the EP at significant risk, as the provider must make decisions without full knowledge of the case. Communication with potential resources such as nursing home staff, the patient’s family, and emergency medical service providers to obtain additional information can help reduce risk.

Of course, when evaluating and treating patients, the EP should always take the time to listen to the patient’s concerns during the encounter to ensure his or her needs have been addressed. In the event of a patient allegation or complaint, the EP should make the effort to explore and de-escalate the situation before the patient is discharged.

Discharge Care and Instructions

According to CRICO, premature discharge as a factor in medical malpractice liability results from inadequate assessment and missed opportunities in 41% of diagnosis-related ED cases.16 The following situation illustrates a brief example of such a missed opportunity: A provider makes a diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) in a patient presenting with fever and abdominal pain but whose urinalysis is suspect for contamination and in whom no pelvic examination was performed to rule out other etiologies. When the same patient later returns to the ED with worse abdominal pain, a sterile urine culture invalidates the diagnosis of UTI, and further evaluation leads to a final diagnosis of ruptured appendix.