User login

Interprofessional Academic Patient Aligned Care Team Panel Management Model

This article is part of a series that illustrates strategies intended to redesign primary care education at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), using interprofessional workplace learning. All have been implemented in the VA Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). These models embody visionary transformation of clinical and educational environments that have potential for replication and dissemination throughout VA and other primary care clinical educational environments. For an introduction to the series see Klink K. Transforming primary care clinical learning environments to optimize education, outcomes, and satisfaction. Fed Pract. 2018;35(9):8-10.

Background

In 2011, 5 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers were selected by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) to establish Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). Part of the New Models of Care initiative, the 5 CoEPCEs use VA primary care settings to develop and test innovative approaches to prepare physician residents, medical students, advanced practice registered nurses, undergraduate nursing students, and other health professions’ trainees, such as social workers, pharmacists, psychologists, and physician assistants, for improved primary care practice. The CoEPCEs are interprofessional Academic PACTs (iAPACTs) with ≥ 2 professions of trainees engaged in learning on the PACT team.

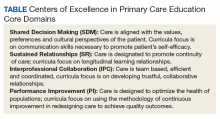

The VA Puget Sound Seattle CoEPCE curriculum is embedded in a well-established academic VA primary care training site.1 Trainees include doctor of nursing practice (DNP) students in adult, family, and psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner (NP) programs; NP residents; internal medicine physician residents; postgraduate pharmacy residents; and other health professions’ trainees. A Seattle CoEPCE priority is to provide DNP students, DNP residents, and physician residents with a longitudinal experience in team-based care as well as interprofessional education and collaborative practice (IPECP). Learners spend the majority of CoEPCE time in supervised, direct patient care, including primary care, women’s health, deployment health, homeless care, and home care. Formal IPECP activities comprise about 20% of time, supported by 3 educational strategies: (1) Panel management (PM)/quality improvement (QI); (2) Team building/ communications; and (3) Clinical content seminars to expand trainee clinical knowledge and skills and curriculum developed with the CoEPCE enterprise core domains in mind (Table).

Panel Management

Clinicians are increasingly being required to proactively optimize the health of an assigned population of patients in addition to assessing and managing the health of individual patients presenting for care. To address the objectives of increased accountability for population health outcomes and improved face-to-face care, Seattle CoEPCE developed curriculum for trainees to learn PM, a set of tools and processes that can be applied in the primary care setting.

PM clinical providers use data to proactively provide care to their patients between traditional clinic visits. The process is proactive in that gaps are identified whether or not an in-person visit occurs and involves an outreach mechanism to increase continuity of care, such as follow-up communications with the patients.2 PM also has been associated with improvements in chronic disease care.3-5

The Seattle CoEPCE developed an interprofessional team approach to PM that teaches trainees about the tools and resources used to close the gaps in care, including the use of clinical team members as health care systems subject matter experts. CoEPCE trainees are taught to analyze the care they provide to their panel of veterans (eg, identifying patients who have not refilled chronic medications or those who use the emergency department [ED] for nonacute conditions) and take action to improve care. PM yields rich discussions on systems resources and processes and is easily applied to a range of health conditions as well as delivery system issues. PM gives learners the tools they can use to close these gaps, such as the expertise of their peers, clinical team, and specialists.6

Planning and Implementation

In addition to completing a literature review to determine the state of PM practice and models, CoEPCE faculty polled recent graduates inquiring about strategies they did not learn prior to graduation. Based on their responses, CoEPCE faculty identified 2 skill deficits: management of chronic diseases and proficiency with data and statistics about performance improvement in panel patient care over time. Addressing these unmet needs became the impetus for developing curriculum for conducting PM. Planning and launching the CoEPCE approach to PM took about 3 months and involved CoEPCE faculty, a data manager, and administrative support. The learning objectives of Seattle’s PM initiative are to:

- Promote preventive health and chronic disease care by use performance data;

- Develop individual- and populationfocused action plans;

- Work collaboratively, strategically, and effectively with an interprofessional care team; and

- Learn how to effectively use system resources.

Curriculum

The PM curriculum is a longitudinal, experiential approach to learning how to manage chronic diseases between visits by using patient data. It is designed for trainees in a continuity clinic to review the care of their patients on a regular basis. Seattle CoEPCE medicine residents are assigned patient panels, which increase from 70 patients in the first year to about 140 patients by the end of the third year. DNP postgraduate trainees are assigned an initial panel of 50 patients that increases incrementally over the year-long residency.

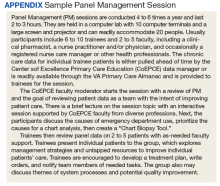

CoEPCE faculty determined the focus of PM sessions to be diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, obesity, chronic opioid therapy, and low-acuity ED use. Because PM sessions are designed to allow participants to identify systems issues that may affect multiple patients, some of these topics have expanded into QI projects. PM sessions run 2 to 3 hours per session and are held 4 to 6 times a year. Each session is repeated twice to accommodate diverse trainee schedules. PM participants must have their patient visit time blocked for each session (Appendix).

Faculty Roles and Development

PM faculty involved in any individual session may include a combination of a CoEPCE clinical pharmacy specialist, a registered nurse (RN) care manager, a social worker, a NP, a physician, a clinical psychologist, and a medicine outpatient chief resident (PGY4, termed clinician-teacher fellow at Seattle VA medical center). The chief resident is a medicine residency graduate and takes on teaching responsibilities depending on the topic of the session. The CoEPCE clinical pharmacist role varies depending on the session topic: They may facilitate the session or provide recommendations for medication management for individual cases. The RN care manager often knows the patients and brings a unique perspective that complements that of the primary care providers and ideally participates in every session. The patients of multiple RN care managers may be presented at each session, and it was not feasible to include all RN care managers in every session. After case discussions, trainees often communicated with the RN care managers about the case, using instant messaging, and CoEPCE provides other avenues for patient care discussion through huddles involving the provider, RN care manager, clinical pharmacist, and other clinical professions.

Resources

The primary resource required to support PM is an information technology (IT) system that provides relevant health outcome and health care utilization data on patients assigned to trainees. PM sessions include teaching trainees how to access patient data. Since discussion about the care of panel patients during the learning sessions often results in real-time adjustments in the care plan, modest administrative support required post-PM sessions, such as clerical scheduling of the requested clinic or telephone follow-up with the physician, nurse, or pharmacist.

Monitoring and Assessment

Panel performance is evaluated at each educational session. To assess the CoEPCE PM curriculum, participants provide feedback in 8 questions over 3 domains: trainee perception of curriculum content, confidence in performing PM involving completion of a PM workshop, and likelihood of using PM techniques in the future. CoEPCE faculty use the feedback to improve their instruction of panel management skill and develop new sessions that target additional population groups. Evaluation of the curriculum also includes monitoring of panel patients’ chronic disease measures.

Several partnerships have contributed to the success and integrations of PM into facility activities. First, having the primary care clinic director as a member of the Co- EPCE faculty has encouraged faculty and staff to operationalize and implement PM broadly by distributing data monthly to all clinic staff. Second, high facility staff interest outside the CoEPCE and primary care clinic has facilitated establishing communications outside the CoEPCE regarding clinic data.

Challenges and Solutions

Trainees at earlier academic levels often desire more instruction in clinical knowledge, such as treatment options for DM or goals of therapy in hypertension. In contrast, advanced trainees are able to review patient data, brainstorm, and optimize solutions. Seattle CoEPCE balances these different learning needs via a flexible approach to the 3-hour sessions. For example, advanced trainees progress from structured short lectures to informal sessions, which train them to perform PM on their own. In addition, the flexible design integrates trainees with diverse schedules, particularly among DNP students and residents, pharmacy residents, and physician residents. Some of this work falls on the RN care management team and administrative support staff.

Competing Priorities

The demand for direct patient care points to the importance of indirect patient care activities like PM to demonstrate improved results. Managing chronic conditions and matching appropriate services and resources should improve clinical outcomes and efficiency longterm. In the interim, it is important to note that PM demonstrates the continuous aspect of clinical care, particularly for trainees who have strict guidelines defining clinical care for the experiences to count toward eligibility for licensure. Additionally, PM results in trainees who are making decisions with VA patients and are more efficiently providing and supporting patient care. Therefore, it is critical to secure important resources, such as provider time for conducting PM.

Data Access

No single data system in VA covers the broad range of topics covered in the PM sessions, and not all trainees have their own assigned panels. For example, health professions students are not assigned a panel of patients. While they do not have access to panel data such as those generated by Primary Care Almanac in VSSC (a data source in the VA Support Service Center database),the Seattle CoEPCE data manager pulls a set of patient data from the students’ paired faculty preceptors’ panels for review. Thus they learn PM principles and strategies for improving patient care via PM as part of the unique VA longitudinal clinic experience and the opportunity to learn from a multidisciplinary team that is not available at other clinical sites. Postgraduate NP residents in CoEPCE training have their own panels of patients and thus the ability to directly access their panel performance data.

Success Factors

A key success factor includes CoEPCE faculty’s ability to develop and operationalize a panel management model that simultaneously aligns with the educational goals of an interprofessional education training program and supports VA adoption of the medical home or patient aligned care teams (PACT). The CoEPCE contributes staff expertise in accessing and reporting patient data, accessing appropriate teaching space, managing panels of patients with chronic diseases, and facilitating a team-based approach to care. Additionally, the CoEPCE brand is helpful for getting buy-in from the clinical and academic stakeholders necessary for moving PM forward.

Colocating CoEPCE trainees and faculty in the primary care clinic promotes team identity around the RN care managers and facilitated communications with non-CoEPCE clinical teams that have trainees from other professions. RN care managers serve as the locus of highquality PM since they share patient panels with the trainees and already track admissions, ED visits, and numerous chronic health care metrics. RN care managers offer a level of insight into chronic disease that other providers may not possess, such as the specific details on medication adherence and the impact of adverse effects (AEs) for that particular patient. RN care managers are able to teach about their team role and responsibilities, strengthening the model.

PM is an opportunity to expand CoEPCE interprofessional education capacity by creating colocation of different trainee and faculty professions during the PM sessions; the sharing of data with trainees; and sharing and reflecting on data, strengthening communications between professions and within the PACT. The Seattle CoEPCE now has systems in place that allow the RN care manager to send notes to a physician and DNP resident, and the resident is expected to respond. In addition, the PM approach provides experience with analyzing data to improve care in an interprofessional team setting, which is a requirement of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Interprofessional Collaboration

PM sessions are intentionally designed to improve communication among team members and foster a team approach to care. PM sessions provide an opportunity for trainees and clinician faculty to be together and learn about each profession’s perspectives. For example, early in the process physician and DNP trainees learn about the importance of clinical pharmacists to the team who prescribe and make medication adjustments within their scope of practice as well as the importance of making appropriate pharmacy referrals. Additionally, the RN care manager and clinical pharmacy specialists who serve as faculty in the CoEPCE provide pertinent information on individual patients, increasing integration with the PACT. Finally, there is anecdotal evidence that faculty also are learning more about interprofessional education and expanding their own skills.

Clinical Performance

CoEPCE trainees, non-CoEPCE physician residents, and CoEPCE faculty participants regularly receive patient data with which they can proactively develop or amend a treatment plan between visits. PM has resulted in improved data sharing with providers. Instead of once a year, providers and clinic staff now receive patient data monthly on chronic conditions from the clinic director. Trainees on ambulatory rotations are expected to review their panel data at least a half day per week. CoEPCE staff evaluate trainee likelihood to use PM and ability to identify patients who benefit from team-based care.

At the population level of chronic disease management, preliminary evidence demonstrates that primary care clinic patient panels are increasingly within target for DM and blood pressure measures, as assessed by periodic clinical reports to providers. Some of the PM topics have resulted in systems-level improvements, such as reducing unnecessary ED use for nonacute conditions and better opioid prescription monitoring. Moreover, PM supports everyone working at the top of his/her professional capability. For example, the RN care manager has the impetus to initiate DM education with a particular patient.

Since CoEPCE began teaching PM, the Seattle primary care clinic has committed to the regular access and review of data. This has encouraged the alignment of standards of care for chronic disease management so that all care providers are working toward the same benchmark goals.

Patient Outcomes

At the individual level, PM provide a mechanism to systemically review trainee panel patients with out-of-target clinical measures, and develop new care approaches involving interprofessional strategies and problem solving. PM also helps identify patients who have missed follow-up, reducing the risk that patients with chronic care needs will be lost to clinical engagement if they are not reminded or do not pursue appointments. The PM-trained PACT reaches out to patients who might not otherwise get care before the next clinic visit and provides new care plans. Second, patients have the benefit of a team that manages their health needs. For example, including the clinical pharmacists in the PM sessions ensures timely identification of medication interactions and the potential AEs. Additionally, PM contributes to the care coordination model by involving individuals on the primary care team who know the patient. These members review the patient’s data between visits and initiate team-based changes to the care plan to improve care. More team members connect with a patient, resulting in more intense care and quicker follow-up to determine the effectiveness of a treatment plan.

PM topics have spun off QI projects resulting in new clinic processes and programs, including processes for managing wounds in primary care and to assure timely post-ED visit follow-ups. Areas for expansion include a follow-up QI project to reduce nonacute ED visits by patients on the homeless PACT panel and interventions for better management of care for women veterans with mental health needs. PM also has extended to non-Co- EPCE teams and to other clinic activities, such as strengthening huddles of team members specifically related to panel data and addressing selected patient cases between visits. Pharmacy residents and faculty are more involved in reviewing the panel before patients are seen to review medication lists and identify duplications.

The Future

Under stage 2 of the program, the Seattle CoEPCE intends to lead in the creation of a PM toolkit as well as a data access guide that will allow VA facilities with limited data management expertise to access chronic disease metrics. Second, the CoEPCE will continue its dissemination efforts locally to other residents in the internal medicine residency program in all of its continuity clinics. Additionally, there is high interest by DNP training programs to expand and export longitudinal training experience PM curriculum to non-VA based students.

1. Kaminetzky CP, Beste LA, Poppe AP, et al. Implementation of a novel panel management curriculum. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):264-269.

2. Neuwirth EB, Schmittdiel JA, Tallman K, Bellows J. Understanding panel management: a comparative study of an emerging approach to population care. Perm J. 2007;11(3):12-20.

3. Loo TS, Davis RB, Lipsitz LA, et al. Electronic medical record reminders and panel management to improve primary care of elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(17):1552-1558.

4. Kanter M, Martinez O, Lindsay G, Andrews K, Denver C. Proactive office encounter: a systematic approach to preventive and chronic care at every patient encounter. Perm J. 2010;14(3):38-43.

5. Kravetz JD, Walsh RF. Team-based hypertension management to improve blood pressure control. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(4):272-275.

6. Kaminetzky CP, Nelson KM. In the office and in-between: the role of panel management in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):876-877.

This article is part of a series that illustrates strategies intended to redesign primary care education at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), using interprofessional workplace learning. All have been implemented in the VA Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). These models embody visionary transformation of clinical and educational environments that have potential for replication and dissemination throughout VA and other primary care clinical educational environments. For an introduction to the series see Klink K. Transforming primary care clinical learning environments to optimize education, outcomes, and satisfaction. Fed Pract. 2018;35(9):8-10.

Background

In 2011, 5 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers were selected by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) to establish Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). Part of the New Models of Care initiative, the 5 CoEPCEs use VA primary care settings to develop and test innovative approaches to prepare physician residents, medical students, advanced practice registered nurses, undergraduate nursing students, and other health professions’ trainees, such as social workers, pharmacists, psychologists, and physician assistants, for improved primary care practice. The CoEPCEs are interprofessional Academic PACTs (iAPACTs) with ≥ 2 professions of trainees engaged in learning on the PACT team.

The VA Puget Sound Seattle CoEPCE curriculum is embedded in a well-established academic VA primary care training site.1 Trainees include doctor of nursing practice (DNP) students in adult, family, and psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner (NP) programs; NP residents; internal medicine physician residents; postgraduate pharmacy residents; and other health professions’ trainees. A Seattle CoEPCE priority is to provide DNP students, DNP residents, and physician residents with a longitudinal experience in team-based care as well as interprofessional education and collaborative practice (IPECP). Learners spend the majority of CoEPCE time in supervised, direct patient care, including primary care, women’s health, deployment health, homeless care, and home care. Formal IPECP activities comprise about 20% of time, supported by 3 educational strategies: (1) Panel management (PM)/quality improvement (QI); (2) Team building/ communications; and (3) Clinical content seminars to expand trainee clinical knowledge and skills and curriculum developed with the CoEPCE enterprise core domains in mind (Table).

Panel Management

Clinicians are increasingly being required to proactively optimize the health of an assigned population of patients in addition to assessing and managing the health of individual patients presenting for care. To address the objectives of increased accountability for population health outcomes and improved face-to-face care, Seattle CoEPCE developed curriculum for trainees to learn PM, a set of tools and processes that can be applied in the primary care setting.

PM clinical providers use data to proactively provide care to their patients between traditional clinic visits. The process is proactive in that gaps are identified whether or not an in-person visit occurs and involves an outreach mechanism to increase continuity of care, such as follow-up communications with the patients.2 PM also has been associated with improvements in chronic disease care.3-5

The Seattle CoEPCE developed an interprofessional team approach to PM that teaches trainees about the tools and resources used to close the gaps in care, including the use of clinical team members as health care systems subject matter experts. CoEPCE trainees are taught to analyze the care they provide to their panel of veterans (eg, identifying patients who have not refilled chronic medications or those who use the emergency department [ED] for nonacute conditions) and take action to improve care. PM yields rich discussions on systems resources and processes and is easily applied to a range of health conditions as well as delivery system issues. PM gives learners the tools they can use to close these gaps, such as the expertise of their peers, clinical team, and specialists.6

Planning and Implementation

In addition to completing a literature review to determine the state of PM practice and models, CoEPCE faculty polled recent graduates inquiring about strategies they did not learn prior to graduation. Based on their responses, CoEPCE faculty identified 2 skill deficits: management of chronic diseases and proficiency with data and statistics about performance improvement in panel patient care over time. Addressing these unmet needs became the impetus for developing curriculum for conducting PM. Planning and launching the CoEPCE approach to PM took about 3 months and involved CoEPCE faculty, a data manager, and administrative support. The learning objectives of Seattle’s PM initiative are to:

- Promote preventive health and chronic disease care by use performance data;

- Develop individual- and populationfocused action plans;

- Work collaboratively, strategically, and effectively with an interprofessional care team; and

- Learn how to effectively use system resources.

Curriculum

The PM curriculum is a longitudinal, experiential approach to learning how to manage chronic diseases between visits by using patient data. It is designed for trainees in a continuity clinic to review the care of their patients on a regular basis. Seattle CoEPCE medicine residents are assigned patient panels, which increase from 70 patients in the first year to about 140 patients by the end of the third year. DNP postgraduate trainees are assigned an initial panel of 50 patients that increases incrementally over the year-long residency.

CoEPCE faculty determined the focus of PM sessions to be diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, obesity, chronic opioid therapy, and low-acuity ED use. Because PM sessions are designed to allow participants to identify systems issues that may affect multiple patients, some of these topics have expanded into QI projects. PM sessions run 2 to 3 hours per session and are held 4 to 6 times a year. Each session is repeated twice to accommodate diverse trainee schedules. PM participants must have their patient visit time blocked for each session (Appendix).

Faculty Roles and Development

PM faculty involved in any individual session may include a combination of a CoEPCE clinical pharmacy specialist, a registered nurse (RN) care manager, a social worker, a NP, a physician, a clinical psychologist, and a medicine outpatient chief resident (PGY4, termed clinician-teacher fellow at Seattle VA medical center). The chief resident is a medicine residency graduate and takes on teaching responsibilities depending on the topic of the session. The CoEPCE clinical pharmacist role varies depending on the session topic: They may facilitate the session or provide recommendations for medication management for individual cases. The RN care manager often knows the patients and brings a unique perspective that complements that of the primary care providers and ideally participates in every session. The patients of multiple RN care managers may be presented at each session, and it was not feasible to include all RN care managers in every session. After case discussions, trainees often communicated with the RN care managers about the case, using instant messaging, and CoEPCE provides other avenues for patient care discussion through huddles involving the provider, RN care manager, clinical pharmacist, and other clinical professions.

Resources

The primary resource required to support PM is an information technology (IT) system that provides relevant health outcome and health care utilization data on patients assigned to trainees. PM sessions include teaching trainees how to access patient data. Since discussion about the care of panel patients during the learning sessions often results in real-time adjustments in the care plan, modest administrative support required post-PM sessions, such as clerical scheduling of the requested clinic or telephone follow-up with the physician, nurse, or pharmacist.

Monitoring and Assessment

Panel performance is evaluated at each educational session. To assess the CoEPCE PM curriculum, participants provide feedback in 8 questions over 3 domains: trainee perception of curriculum content, confidence in performing PM involving completion of a PM workshop, and likelihood of using PM techniques in the future. CoEPCE faculty use the feedback to improve their instruction of panel management skill and develop new sessions that target additional population groups. Evaluation of the curriculum also includes monitoring of panel patients’ chronic disease measures.

Several partnerships have contributed to the success and integrations of PM into facility activities. First, having the primary care clinic director as a member of the Co- EPCE faculty has encouraged faculty and staff to operationalize and implement PM broadly by distributing data monthly to all clinic staff. Second, high facility staff interest outside the CoEPCE and primary care clinic has facilitated establishing communications outside the CoEPCE regarding clinic data.

Challenges and Solutions

Trainees at earlier academic levels often desire more instruction in clinical knowledge, such as treatment options for DM or goals of therapy in hypertension. In contrast, advanced trainees are able to review patient data, brainstorm, and optimize solutions. Seattle CoEPCE balances these different learning needs via a flexible approach to the 3-hour sessions. For example, advanced trainees progress from structured short lectures to informal sessions, which train them to perform PM on their own. In addition, the flexible design integrates trainees with diverse schedules, particularly among DNP students and residents, pharmacy residents, and physician residents. Some of this work falls on the RN care management team and administrative support staff.

Competing Priorities

The demand for direct patient care points to the importance of indirect patient care activities like PM to demonstrate improved results. Managing chronic conditions and matching appropriate services and resources should improve clinical outcomes and efficiency longterm. In the interim, it is important to note that PM demonstrates the continuous aspect of clinical care, particularly for trainees who have strict guidelines defining clinical care for the experiences to count toward eligibility for licensure. Additionally, PM results in trainees who are making decisions with VA patients and are more efficiently providing and supporting patient care. Therefore, it is critical to secure important resources, such as provider time for conducting PM.

Data Access

No single data system in VA covers the broad range of topics covered in the PM sessions, and not all trainees have their own assigned panels. For example, health professions students are not assigned a panel of patients. While they do not have access to panel data such as those generated by Primary Care Almanac in VSSC (a data source in the VA Support Service Center database),the Seattle CoEPCE data manager pulls a set of patient data from the students’ paired faculty preceptors’ panels for review. Thus they learn PM principles and strategies for improving patient care via PM as part of the unique VA longitudinal clinic experience and the opportunity to learn from a multidisciplinary team that is not available at other clinical sites. Postgraduate NP residents in CoEPCE training have their own panels of patients and thus the ability to directly access their panel performance data.

Success Factors

A key success factor includes CoEPCE faculty’s ability to develop and operationalize a panel management model that simultaneously aligns with the educational goals of an interprofessional education training program and supports VA adoption of the medical home or patient aligned care teams (PACT). The CoEPCE contributes staff expertise in accessing and reporting patient data, accessing appropriate teaching space, managing panels of patients with chronic diseases, and facilitating a team-based approach to care. Additionally, the CoEPCE brand is helpful for getting buy-in from the clinical and academic stakeholders necessary for moving PM forward.

Colocating CoEPCE trainees and faculty in the primary care clinic promotes team identity around the RN care managers and facilitated communications with non-CoEPCE clinical teams that have trainees from other professions. RN care managers serve as the locus of highquality PM since they share patient panels with the trainees and already track admissions, ED visits, and numerous chronic health care metrics. RN care managers offer a level of insight into chronic disease that other providers may not possess, such as the specific details on medication adherence and the impact of adverse effects (AEs) for that particular patient. RN care managers are able to teach about their team role and responsibilities, strengthening the model.

PM is an opportunity to expand CoEPCE interprofessional education capacity by creating colocation of different trainee and faculty professions during the PM sessions; the sharing of data with trainees; and sharing and reflecting on data, strengthening communications between professions and within the PACT. The Seattle CoEPCE now has systems in place that allow the RN care manager to send notes to a physician and DNP resident, and the resident is expected to respond. In addition, the PM approach provides experience with analyzing data to improve care in an interprofessional team setting, which is a requirement of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Interprofessional Collaboration

PM sessions are intentionally designed to improve communication among team members and foster a team approach to care. PM sessions provide an opportunity for trainees and clinician faculty to be together and learn about each profession’s perspectives. For example, early in the process physician and DNP trainees learn about the importance of clinical pharmacists to the team who prescribe and make medication adjustments within their scope of practice as well as the importance of making appropriate pharmacy referrals. Additionally, the RN care manager and clinical pharmacy specialists who serve as faculty in the CoEPCE provide pertinent information on individual patients, increasing integration with the PACT. Finally, there is anecdotal evidence that faculty also are learning more about interprofessional education and expanding their own skills.

Clinical Performance

CoEPCE trainees, non-CoEPCE physician residents, and CoEPCE faculty participants regularly receive patient data with which they can proactively develop or amend a treatment plan between visits. PM has resulted in improved data sharing with providers. Instead of once a year, providers and clinic staff now receive patient data monthly on chronic conditions from the clinic director. Trainees on ambulatory rotations are expected to review their panel data at least a half day per week. CoEPCE staff evaluate trainee likelihood to use PM and ability to identify patients who benefit from team-based care.

At the population level of chronic disease management, preliminary evidence demonstrates that primary care clinic patient panels are increasingly within target for DM and blood pressure measures, as assessed by periodic clinical reports to providers. Some of the PM topics have resulted in systems-level improvements, such as reducing unnecessary ED use for nonacute conditions and better opioid prescription monitoring. Moreover, PM supports everyone working at the top of his/her professional capability. For example, the RN care manager has the impetus to initiate DM education with a particular patient.

Since CoEPCE began teaching PM, the Seattle primary care clinic has committed to the regular access and review of data. This has encouraged the alignment of standards of care for chronic disease management so that all care providers are working toward the same benchmark goals.

Patient Outcomes

At the individual level, PM provide a mechanism to systemically review trainee panel patients with out-of-target clinical measures, and develop new care approaches involving interprofessional strategies and problem solving. PM also helps identify patients who have missed follow-up, reducing the risk that patients with chronic care needs will be lost to clinical engagement if they are not reminded or do not pursue appointments. The PM-trained PACT reaches out to patients who might not otherwise get care before the next clinic visit and provides new care plans. Second, patients have the benefit of a team that manages their health needs. For example, including the clinical pharmacists in the PM sessions ensures timely identification of medication interactions and the potential AEs. Additionally, PM contributes to the care coordination model by involving individuals on the primary care team who know the patient. These members review the patient’s data between visits and initiate team-based changes to the care plan to improve care. More team members connect with a patient, resulting in more intense care and quicker follow-up to determine the effectiveness of a treatment plan.

PM topics have spun off QI projects resulting in new clinic processes and programs, including processes for managing wounds in primary care and to assure timely post-ED visit follow-ups. Areas for expansion include a follow-up QI project to reduce nonacute ED visits by patients on the homeless PACT panel and interventions for better management of care for women veterans with mental health needs. PM also has extended to non-Co- EPCE teams and to other clinic activities, such as strengthening huddles of team members specifically related to panel data and addressing selected patient cases between visits. Pharmacy residents and faculty are more involved in reviewing the panel before patients are seen to review medication lists and identify duplications.

The Future

Under stage 2 of the program, the Seattle CoEPCE intends to lead in the creation of a PM toolkit as well as a data access guide that will allow VA facilities with limited data management expertise to access chronic disease metrics. Second, the CoEPCE will continue its dissemination efforts locally to other residents in the internal medicine residency program in all of its continuity clinics. Additionally, there is high interest by DNP training programs to expand and export longitudinal training experience PM curriculum to non-VA based students.

This article is part of a series that illustrates strategies intended to redesign primary care education at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), using interprofessional workplace learning. All have been implemented in the VA Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). These models embody visionary transformation of clinical and educational environments that have potential for replication and dissemination throughout VA and other primary care clinical educational environments. For an introduction to the series see Klink K. Transforming primary care clinical learning environments to optimize education, outcomes, and satisfaction. Fed Pract. 2018;35(9):8-10.

Background

In 2011, 5 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers were selected by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) to establish Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). Part of the New Models of Care initiative, the 5 CoEPCEs use VA primary care settings to develop and test innovative approaches to prepare physician residents, medical students, advanced practice registered nurses, undergraduate nursing students, and other health professions’ trainees, such as social workers, pharmacists, psychologists, and physician assistants, for improved primary care practice. The CoEPCEs are interprofessional Academic PACTs (iAPACTs) with ≥ 2 professions of trainees engaged in learning on the PACT team.

The VA Puget Sound Seattle CoEPCE curriculum is embedded in a well-established academic VA primary care training site.1 Trainees include doctor of nursing practice (DNP) students in adult, family, and psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner (NP) programs; NP residents; internal medicine physician residents; postgraduate pharmacy residents; and other health professions’ trainees. A Seattle CoEPCE priority is to provide DNP students, DNP residents, and physician residents with a longitudinal experience in team-based care as well as interprofessional education and collaborative practice (IPECP). Learners spend the majority of CoEPCE time in supervised, direct patient care, including primary care, women’s health, deployment health, homeless care, and home care. Formal IPECP activities comprise about 20% of time, supported by 3 educational strategies: (1) Panel management (PM)/quality improvement (QI); (2) Team building/ communications; and (3) Clinical content seminars to expand trainee clinical knowledge and skills and curriculum developed with the CoEPCE enterprise core domains in mind (Table).

Panel Management

Clinicians are increasingly being required to proactively optimize the health of an assigned population of patients in addition to assessing and managing the health of individual patients presenting for care. To address the objectives of increased accountability for population health outcomes and improved face-to-face care, Seattle CoEPCE developed curriculum for trainees to learn PM, a set of tools and processes that can be applied in the primary care setting.

PM clinical providers use data to proactively provide care to their patients between traditional clinic visits. The process is proactive in that gaps are identified whether or not an in-person visit occurs and involves an outreach mechanism to increase continuity of care, such as follow-up communications with the patients.2 PM also has been associated with improvements in chronic disease care.3-5

The Seattle CoEPCE developed an interprofessional team approach to PM that teaches trainees about the tools and resources used to close the gaps in care, including the use of clinical team members as health care systems subject matter experts. CoEPCE trainees are taught to analyze the care they provide to their panel of veterans (eg, identifying patients who have not refilled chronic medications or those who use the emergency department [ED] for nonacute conditions) and take action to improve care. PM yields rich discussions on systems resources and processes and is easily applied to a range of health conditions as well as delivery system issues. PM gives learners the tools they can use to close these gaps, such as the expertise of their peers, clinical team, and specialists.6

Planning and Implementation

In addition to completing a literature review to determine the state of PM practice and models, CoEPCE faculty polled recent graduates inquiring about strategies they did not learn prior to graduation. Based on their responses, CoEPCE faculty identified 2 skill deficits: management of chronic diseases and proficiency with data and statistics about performance improvement in panel patient care over time. Addressing these unmet needs became the impetus for developing curriculum for conducting PM. Planning and launching the CoEPCE approach to PM took about 3 months and involved CoEPCE faculty, a data manager, and administrative support. The learning objectives of Seattle’s PM initiative are to:

- Promote preventive health and chronic disease care by use performance data;

- Develop individual- and populationfocused action plans;

- Work collaboratively, strategically, and effectively with an interprofessional care team; and

- Learn how to effectively use system resources.

Curriculum

The PM curriculum is a longitudinal, experiential approach to learning how to manage chronic diseases between visits by using patient data. It is designed for trainees in a continuity clinic to review the care of their patients on a regular basis. Seattle CoEPCE medicine residents are assigned patient panels, which increase from 70 patients in the first year to about 140 patients by the end of the third year. DNP postgraduate trainees are assigned an initial panel of 50 patients that increases incrementally over the year-long residency.

CoEPCE faculty determined the focus of PM sessions to be diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, obesity, chronic opioid therapy, and low-acuity ED use. Because PM sessions are designed to allow participants to identify systems issues that may affect multiple patients, some of these topics have expanded into QI projects. PM sessions run 2 to 3 hours per session and are held 4 to 6 times a year. Each session is repeated twice to accommodate diverse trainee schedules. PM participants must have their patient visit time blocked for each session (Appendix).

Faculty Roles and Development

PM faculty involved in any individual session may include a combination of a CoEPCE clinical pharmacy specialist, a registered nurse (RN) care manager, a social worker, a NP, a physician, a clinical psychologist, and a medicine outpatient chief resident (PGY4, termed clinician-teacher fellow at Seattle VA medical center). The chief resident is a medicine residency graduate and takes on teaching responsibilities depending on the topic of the session. The CoEPCE clinical pharmacist role varies depending on the session topic: They may facilitate the session or provide recommendations for medication management for individual cases. The RN care manager often knows the patients and brings a unique perspective that complements that of the primary care providers and ideally participates in every session. The patients of multiple RN care managers may be presented at each session, and it was not feasible to include all RN care managers in every session. After case discussions, trainees often communicated with the RN care managers about the case, using instant messaging, and CoEPCE provides other avenues for patient care discussion through huddles involving the provider, RN care manager, clinical pharmacist, and other clinical professions.

Resources

The primary resource required to support PM is an information technology (IT) system that provides relevant health outcome and health care utilization data on patients assigned to trainees. PM sessions include teaching trainees how to access patient data. Since discussion about the care of panel patients during the learning sessions often results in real-time adjustments in the care plan, modest administrative support required post-PM sessions, such as clerical scheduling of the requested clinic or telephone follow-up with the physician, nurse, or pharmacist.

Monitoring and Assessment

Panel performance is evaluated at each educational session. To assess the CoEPCE PM curriculum, participants provide feedback in 8 questions over 3 domains: trainee perception of curriculum content, confidence in performing PM involving completion of a PM workshop, and likelihood of using PM techniques in the future. CoEPCE faculty use the feedback to improve their instruction of panel management skill and develop new sessions that target additional population groups. Evaluation of the curriculum also includes monitoring of panel patients’ chronic disease measures.

Several partnerships have contributed to the success and integrations of PM into facility activities. First, having the primary care clinic director as a member of the Co- EPCE faculty has encouraged faculty and staff to operationalize and implement PM broadly by distributing data monthly to all clinic staff. Second, high facility staff interest outside the CoEPCE and primary care clinic has facilitated establishing communications outside the CoEPCE regarding clinic data.

Challenges and Solutions

Trainees at earlier academic levels often desire more instruction in clinical knowledge, such as treatment options for DM or goals of therapy in hypertension. In contrast, advanced trainees are able to review patient data, brainstorm, and optimize solutions. Seattle CoEPCE balances these different learning needs via a flexible approach to the 3-hour sessions. For example, advanced trainees progress from structured short lectures to informal sessions, which train them to perform PM on their own. In addition, the flexible design integrates trainees with diverse schedules, particularly among DNP students and residents, pharmacy residents, and physician residents. Some of this work falls on the RN care management team and administrative support staff.

Competing Priorities

The demand for direct patient care points to the importance of indirect patient care activities like PM to demonstrate improved results. Managing chronic conditions and matching appropriate services and resources should improve clinical outcomes and efficiency longterm. In the interim, it is important to note that PM demonstrates the continuous aspect of clinical care, particularly for trainees who have strict guidelines defining clinical care for the experiences to count toward eligibility for licensure. Additionally, PM results in trainees who are making decisions with VA patients and are more efficiently providing and supporting patient care. Therefore, it is critical to secure important resources, such as provider time for conducting PM.

Data Access

No single data system in VA covers the broad range of topics covered in the PM sessions, and not all trainees have their own assigned panels. For example, health professions students are not assigned a panel of patients. While they do not have access to panel data such as those generated by Primary Care Almanac in VSSC (a data source in the VA Support Service Center database),the Seattle CoEPCE data manager pulls a set of patient data from the students’ paired faculty preceptors’ panels for review. Thus they learn PM principles and strategies for improving patient care via PM as part of the unique VA longitudinal clinic experience and the opportunity to learn from a multidisciplinary team that is not available at other clinical sites. Postgraduate NP residents in CoEPCE training have their own panels of patients and thus the ability to directly access their panel performance data.

Success Factors

A key success factor includes CoEPCE faculty’s ability to develop and operationalize a panel management model that simultaneously aligns with the educational goals of an interprofessional education training program and supports VA adoption of the medical home or patient aligned care teams (PACT). The CoEPCE contributes staff expertise in accessing and reporting patient data, accessing appropriate teaching space, managing panels of patients with chronic diseases, and facilitating a team-based approach to care. Additionally, the CoEPCE brand is helpful for getting buy-in from the clinical and academic stakeholders necessary for moving PM forward.

Colocating CoEPCE trainees and faculty in the primary care clinic promotes team identity around the RN care managers and facilitated communications with non-CoEPCE clinical teams that have trainees from other professions. RN care managers serve as the locus of highquality PM since they share patient panels with the trainees and already track admissions, ED visits, and numerous chronic health care metrics. RN care managers offer a level of insight into chronic disease that other providers may not possess, such as the specific details on medication adherence and the impact of adverse effects (AEs) for that particular patient. RN care managers are able to teach about their team role and responsibilities, strengthening the model.

PM is an opportunity to expand CoEPCE interprofessional education capacity by creating colocation of different trainee and faculty professions during the PM sessions; the sharing of data with trainees; and sharing and reflecting on data, strengthening communications between professions and within the PACT. The Seattle CoEPCE now has systems in place that allow the RN care manager to send notes to a physician and DNP resident, and the resident is expected to respond. In addition, the PM approach provides experience with analyzing data to improve care in an interprofessional team setting, which is a requirement of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Interprofessional Collaboration

PM sessions are intentionally designed to improve communication among team members and foster a team approach to care. PM sessions provide an opportunity for trainees and clinician faculty to be together and learn about each profession’s perspectives. For example, early in the process physician and DNP trainees learn about the importance of clinical pharmacists to the team who prescribe and make medication adjustments within their scope of practice as well as the importance of making appropriate pharmacy referrals. Additionally, the RN care manager and clinical pharmacy specialists who serve as faculty in the CoEPCE provide pertinent information on individual patients, increasing integration with the PACT. Finally, there is anecdotal evidence that faculty also are learning more about interprofessional education and expanding their own skills.

Clinical Performance

CoEPCE trainees, non-CoEPCE physician residents, and CoEPCE faculty participants regularly receive patient data with which they can proactively develop or amend a treatment plan between visits. PM has resulted in improved data sharing with providers. Instead of once a year, providers and clinic staff now receive patient data monthly on chronic conditions from the clinic director. Trainees on ambulatory rotations are expected to review their panel data at least a half day per week. CoEPCE staff evaluate trainee likelihood to use PM and ability to identify patients who benefit from team-based care.

At the population level of chronic disease management, preliminary evidence demonstrates that primary care clinic patient panels are increasingly within target for DM and blood pressure measures, as assessed by periodic clinical reports to providers. Some of the PM topics have resulted in systems-level improvements, such as reducing unnecessary ED use for nonacute conditions and better opioid prescription monitoring. Moreover, PM supports everyone working at the top of his/her professional capability. For example, the RN care manager has the impetus to initiate DM education with a particular patient.

Since CoEPCE began teaching PM, the Seattle primary care clinic has committed to the regular access and review of data. This has encouraged the alignment of standards of care for chronic disease management so that all care providers are working toward the same benchmark goals.

Patient Outcomes

At the individual level, PM provide a mechanism to systemically review trainee panel patients with out-of-target clinical measures, and develop new care approaches involving interprofessional strategies and problem solving. PM also helps identify patients who have missed follow-up, reducing the risk that patients with chronic care needs will be lost to clinical engagement if they are not reminded or do not pursue appointments. The PM-trained PACT reaches out to patients who might not otherwise get care before the next clinic visit and provides new care plans. Second, patients have the benefit of a team that manages their health needs. For example, including the clinical pharmacists in the PM sessions ensures timely identification of medication interactions and the potential AEs. Additionally, PM contributes to the care coordination model by involving individuals on the primary care team who know the patient. These members review the patient’s data between visits and initiate team-based changes to the care plan to improve care. More team members connect with a patient, resulting in more intense care and quicker follow-up to determine the effectiveness of a treatment plan.

PM topics have spun off QI projects resulting in new clinic processes and programs, including processes for managing wounds in primary care and to assure timely post-ED visit follow-ups. Areas for expansion include a follow-up QI project to reduce nonacute ED visits by patients on the homeless PACT panel and interventions for better management of care for women veterans with mental health needs. PM also has extended to non-Co- EPCE teams and to other clinic activities, such as strengthening huddles of team members specifically related to panel data and addressing selected patient cases between visits. Pharmacy residents and faculty are more involved in reviewing the panel before patients are seen to review medication lists and identify duplications.

The Future

Under stage 2 of the program, the Seattle CoEPCE intends to lead in the creation of a PM toolkit as well as a data access guide that will allow VA facilities with limited data management expertise to access chronic disease metrics. Second, the CoEPCE will continue its dissemination efforts locally to other residents in the internal medicine residency program in all of its continuity clinics. Additionally, there is high interest by DNP training programs to expand and export longitudinal training experience PM curriculum to non-VA based students.

1. Kaminetzky CP, Beste LA, Poppe AP, et al. Implementation of a novel panel management curriculum. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):264-269.

2. Neuwirth EB, Schmittdiel JA, Tallman K, Bellows J. Understanding panel management: a comparative study of an emerging approach to population care. Perm J. 2007;11(3):12-20.

3. Loo TS, Davis RB, Lipsitz LA, et al. Electronic medical record reminders and panel management to improve primary care of elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(17):1552-1558.

4. Kanter M, Martinez O, Lindsay G, Andrews K, Denver C. Proactive office encounter: a systematic approach to preventive and chronic care at every patient encounter. Perm J. 2010;14(3):38-43.

5. Kravetz JD, Walsh RF. Team-based hypertension management to improve blood pressure control. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(4):272-275.

6. Kaminetzky CP, Nelson KM. In the office and in-between: the role of panel management in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):876-877.

1. Kaminetzky CP, Beste LA, Poppe AP, et al. Implementation of a novel panel management curriculum. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):264-269.

2. Neuwirth EB, Schmittdiel JA, Tallman K, Bellows J. Understanding panel management: a comparative study of an emerging approach to population care. Perm J. 2007;11(3):12-20.

3. Loo TS, Davis RB, Lipsitz LA, et al. Electronic medical record reminders and panel management to improve primary care of elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(17):1552-1558.

4. Kanter M, Martinez O, Lindsay G, Andrews K, Denver C. Proactive office encounter: a systematic approach to preventive and chronic care at every patient encounter. Perm J. 2010;14(3):38-43.

5. Kravetz JD, Walsh RF. Team-based hypertension management to improve blood pressure control. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(4):272-275.

6. Kaminetzky CP, Nelson KM. In the office and in-between: the role of panel management in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):876-877.