User login

Resolution of Psoriatic Lesions on the Gingiva and Hard Palate Following Administration of Adalimumab for Cutaneous Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory systemic disorder of the skin with an incidence of 2% to 3% and is estimated to affect 125 million individuals worldwide.1 Environmental triggers of disease modulation may include cutaneous microbiota, smoking, alcohol use, drugs (ie, beta-blockers, lithium, antimalarials), stress, and trauma.2 Comorbidities associated with cutaneous lesions include psoriatic arthritis, Crohn disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, stroke, and cardiovascular disease.3 In some studies, patients with psoriasis also had a 24% to 27% increased propensity for periodontal bone loss versus 10% of controls.4,5

Oral psoriasis is rare and case reports have been preferentially published in dental journals, usually with regard to glossal lesions, leaving gingival and palatal psoriatic involvement infrequently reported in the dermatologic literature.6,7 In fact, oral assessments involving 535 psoriatic patients from a dermatology center only yielded cases of geographic and fissured tongue.8 Another study at a psoriasis clinic found 3.8% (21/547) of patients with geographic tongue, 3.1% (17/547) with buccal mucosal plaques, and only 0.4% (2/547) with palatal lesions.9 To extend the knowledge of oral psoriasis, we provide the clinical and histopathologic findings of a patient with synchronous oral and cutaneous psoriatic lesions that responded well to the administration of adalimumab for management of recurrent cutaneous disease.

Case Report

A 51-year-old man presented to the attending periodontist for comprehensive treatment of multiple quadrants of gingival recession. His medical history was remarkable for psoriasis; Prinzmetal angina, which led to myocardial infarction; and diverticulitis. The cutaneous psoriasis began approximately 18 years prior to the current presentation and was initially managed with various topical therapeutics. At an 11-year follow-up, the patient was experiencing poor lesional control as well as severe pruritus and was prescribed etanercept by a dermatologist. His inconsistent compliance with frequency and dosing failed to achieve satisfactory disease suppression and etanercept was discontinued after approximately 2.5 years. Two years later the patient was switched to adalimumab by a dermatologist, and around this time he had developed psoriatic arthritis of the hands and knees and pitting of the nail plates. The patient elected to discontinue adalimumab usage after 3 years due to successful management of the skin lesions, cost considerations, and his perception that the psoriasis could “remain in remission.” After a 6-month lapse, the patient resumed adalimumab due to cutaneous lesional recurrence (Figure 1A).

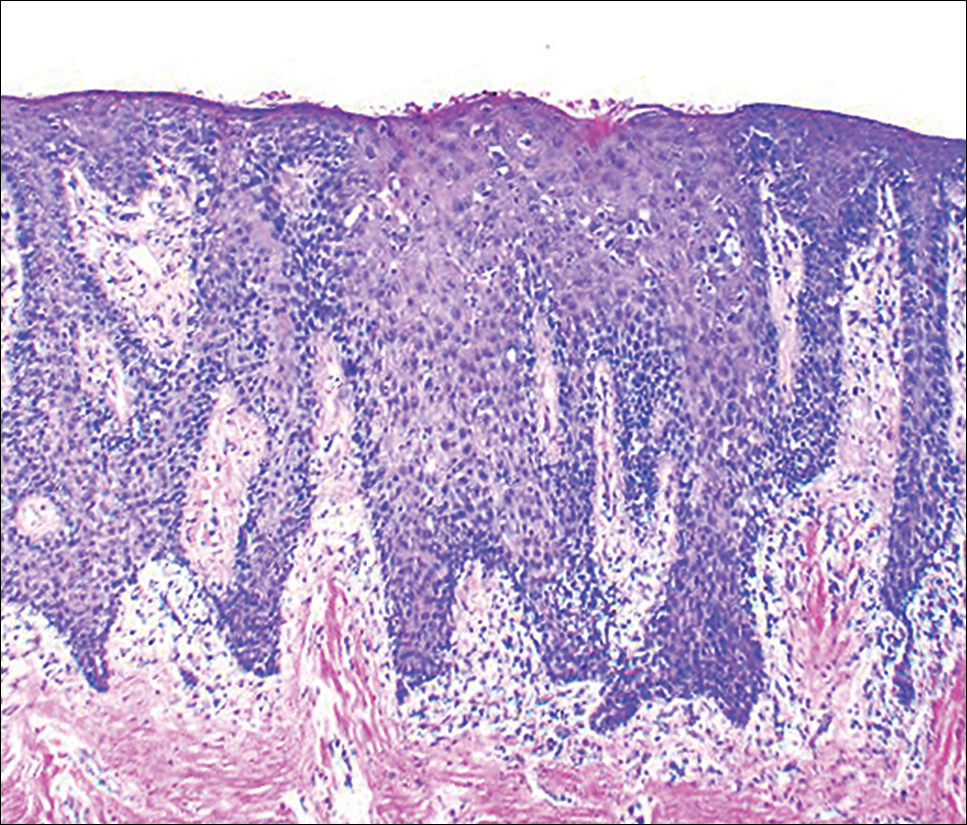

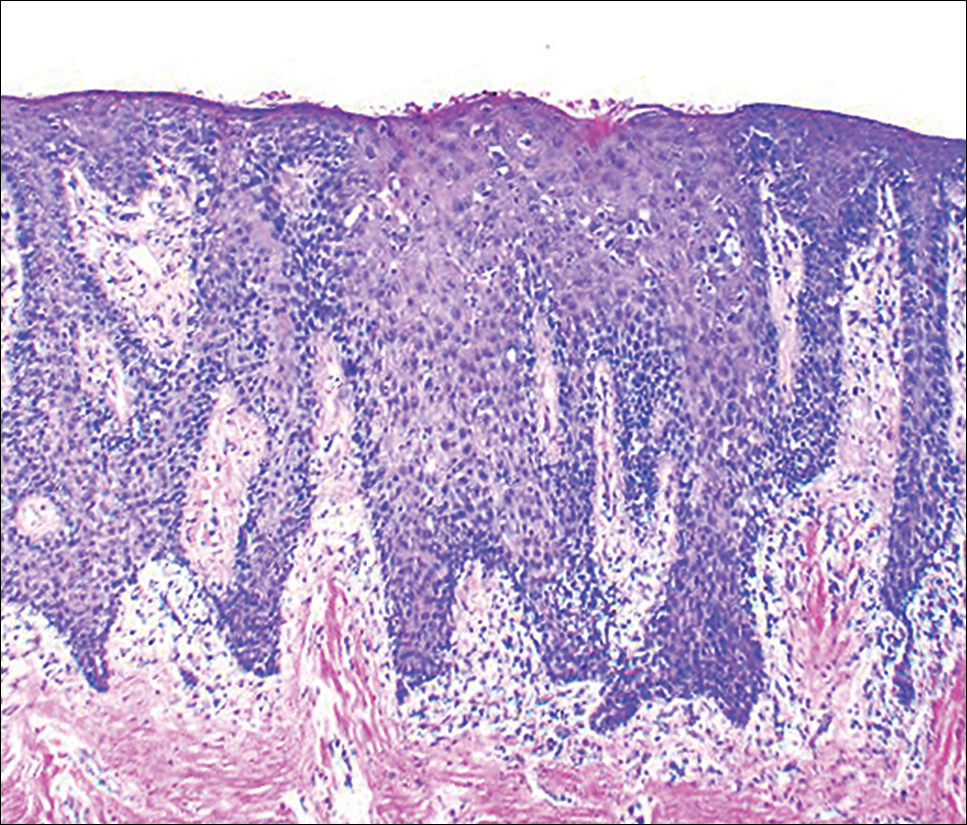

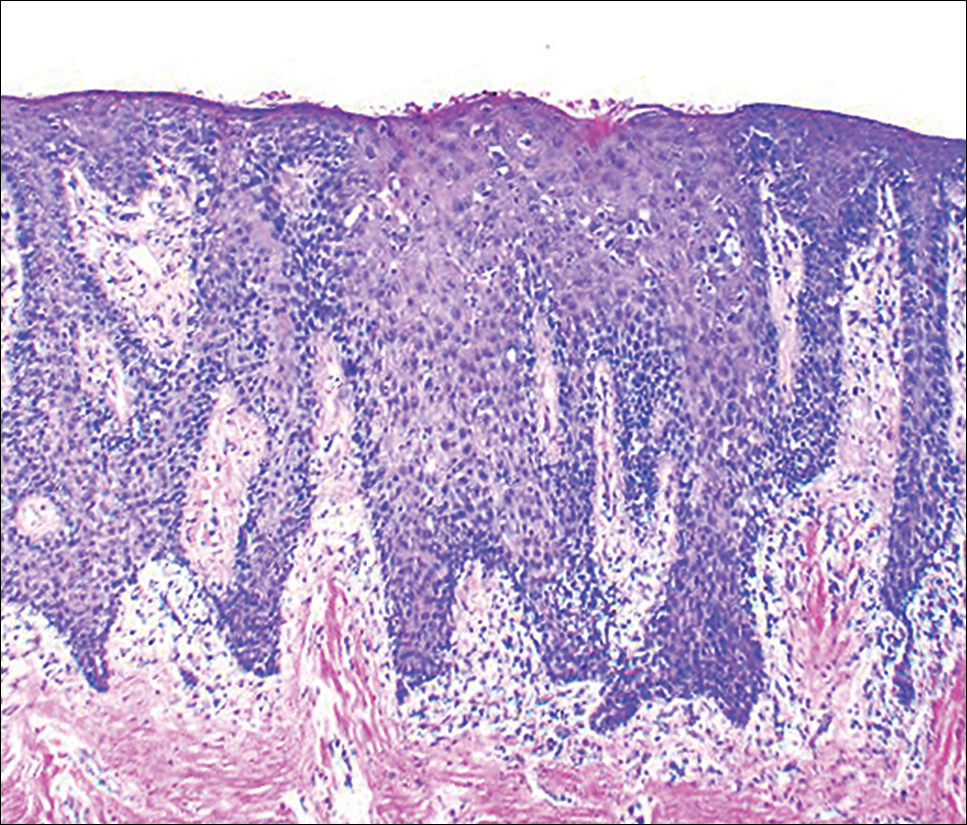

At the current presentation, an oral examination performed 2 days after the reinstitution of adalim-umab revealed generalized severe gingivitis with an atypical inflammatory response that extended from just beyond the mucogingival junction to the marginal gingiva. The gingiva also appeared edematous with a conspicuously granular surface (Figure 1B). The hard palate displayed multiple red macules of varying sizes (Figure 1C). A maxillary gingival biopsy demonstrated hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, spongiosis, acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, numerous collections of neutrophils (Munro microabscesses), and abundant lymphocytes in the subjacent connective tissue (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal hyphae. These features were consistent with oral mucosal psoriasis.

At a 2-month follow-up, the biopsy site had healed without incident and without loss of the gingival architecture. There was an almost-complete resolution of the gingival erythema (Figure 3A) and the patient has since noticed a lack of bleeding using floss. Additionally, the red macules on the palate were no longer present (Figure 3B). The cutaneous plaques were greatly reduced in size and the patient experienced a proportionate decline in pruritus. Based on the uneventful surgical biopsy procedure, the patient was advised to undergo gingival grafting and has not returned for periodontal care.

Comment

Psoriasis of the oral cavity is rare and typically occurs on the tongue and less frequently on the hard palate, lip, buccal mucosa, and gingiva.2,7 The lesions are almost always concordant with cutaneous psoriasis, and only sporadic examples exclusive to the oral mucosa have been recognized.7,10 Gingival psoriasis usually is described as intensely erythematous and occasionally laced with white scaly streaks involving the marginal gingiva that extend toward the mucogingival junction. In general, the erythematous presentation of gingival psoriasis may not be commensurate with the degree of inflammation induced by dental plaque-based periodontal disease. Doben11 documented gingival psoriasis as appearing “deeply stippled and grainy” and commented that the tissue was “friable” and incapable of maintaining a “clean incision line” during periodontal surgery. In our patient, the gingiva also had exhibited a granular surface. Patients with oral psoriasis often report soreness or a burning sensation of the gingiva, which may easily bleed on manipulation or brushing the teeth, whereas other patients are asymptomatic,12 as in our case. Psoriasis of the hard palate usually presents as multiple painless red macules. Unlike cutaneous psoriasis, oral lesions rarely evoke pruritus.10 Histopathologically, oral psoriasis bears a striking resemblance to its cutaneous counterpart. The epithelium has a pronounced parakeratinized surface with elongated rete ridges and aggregations of Munro microabscesses. The connective tissue often is composed of dilated capillaries that closely approximate the epithelium as well as infiltrations of lymphocytes. Specimens suspected for oral psoriasis should routinely be stained with periodic acid–Schiff to rule out candidiasis coinfection. The microscopic findings of our patient were congruent with prior reports of oral psoriasis.7,10-12 Some clinicians have questioned if psoriasis can actually occur in the oral cavity, but most authorities in the field have recognized its true existence, as evidenced by various shared HLA antigens, specifically HLA-Cw.13

Another group of oral lesions collectively referred to as psoriasiform mucositis, notably geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis, erythema migrans) and its extraglossal variant geographic stomatitis,14,15 have histopathologic features and HLAs similar to those seen in cutaneous psoriasis.13 Interestingly, geographic tongue has been found in 3.8% to 9.1% of cohorts with cutaneous psoriasis,8,9 but in the extant population, the vast majority of patients with oral psoriasiform mucositis do not have cutaneous psoriasis. Other differential diagnoses for gingival psoriasis are lichen planus, human immunodeficiency virus–associated periodontitis, desquamative gingivitis, plasma cell gingivitis, erythematous candidiasis, mucous membrane pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, leukemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, orofacial granulomatosis, localized juvenile spongiotic gingivitis hyperplasia, and primary gingivostomatitis.

Management of gingival psoriasis focuses on strategies to reduce inflammation and discomfort and measures to achieve meticulous oral plaque control. Judicious efforts should be exercised to avoid oral soft-tissue injury when performing periodontal scaling, although it has not been established whether gingival psoriasis is associated with the Köbner phenomenon, as seen with cutaneous lesions. Adjunctive measures employed for symptomatic patients have involved the use of corticosteroids (eg, lesional injection, oral rinse, systemic) and oral rinses with retinoic acid, chlorhexidine gluconate, and warm saline.7,10,16 Prolonged utilization of corticosteroids, however, may necessitate supplemental administration of antifungal agents.

This case report represents a rare documentation of a successful outcome of gingival and palatal psoriasis subsequent to the reinstitution of adalimumab solely for treatment of recurrent cutaneous disease. There likely is a pharmacologic basis for the amelioration of oral psoriasis in our patient. Adalimumab is a bivalent IgG monoclonal antibody that binds to activated dermal dendritic cell receptors of tumor necrosis factor α, thereby attenuating a cytokine-derived inflammatory response and apoptosis.17 In fact, patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed notable reductions in both gingival inflammation and bleeding following a 3-month regimen of adalimumab.18

Conclusion

Practitioners should be aware of the phenotypic overlap of cutaneous and oral psoriasis, particularly involving the gingiva and palate. It is recommended that psoriasis patients routinely receive a dental prophylaxis and engage in oral hygiene efforts to reduce the presence of oral microbiota. Furthermore, it is emphasized that psoriatic patients who maintain an atypical erythematous presentation on the oral mucosa undergo a biopsy for identification of the lesions and correlation with disease dissemination. Prospective studies are needed to characterize the clinical courses of oral psoriasis, ascertain their correlative behavior with cutaneous flares, and determine if lesional improvement can be achieved with the use of biologic agents or other therapeutic modalities.

- Gupta R, Debbaneh MG, Liao W. Genetic epidemiology of psoriasis. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2014;3:61-78.

- Younai FS, Phelan JA. Oral mucositis with features of psoriasis: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:61-67.

- Xu T, Zhang YH. Association of psoriasis with stroke and myocardial infarction: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1345-1350.

- Lazaridou E, Tsikrikoni A, Fotiadou C, et al. Association of chronic plaque psoriasis and severe periodontitis: a hospital based case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:967-972.

- Skudutyte-Rysstad R, Slevolden EM, Hansen BF, et al. Association between moderate to severe psoriasis and periodontitis in a Scandinavian population. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:139.

- Zunt SL, Tomich CE. Erythema migrans—a psoriasiform lesion of the oral mucosa. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:1067-1070.

- Reis V, Artico G, Seo J, et al. Psoriasiform mucositis on the gingival and palatal mucosae treated with retinoic-acid mouthwash. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:113-115.

- Germi L, De Giorgi V, Bergamo F, et al. Psoriasis and oral lesions: multicentric study of oral mucosa diseases Italian group (GIPMO). Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11.

- Kaur I, Handa S, Kumar B. Oral lesions in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:78-79.

- Brayshaw HA, Orban B. Psoriasis gingivae. J Periodontol. 1953;24:156-160.

- Doben DI. Psoriasis of the attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1976;47:38-40.

- Mattsson U, Warfvinge G, Jontell M. Oral psoriasis—a diagnostic dilemma: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;120:e183-e189.

- Dermatologic diseases. In: Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, et al, eds. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009:792-794.

- Brooks JK, Balciunas BA. Geographic stomatitis: review of the literature and report of five cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115:421-424.

- Brooks JK, Nikitakis NG. Multiple mucosal lesions. erythema migrans. Gen Dent. 2007;55:160, 163.

- Ulmansky M, Michelle R, Azaz B. Oral psoriasis: report of six new cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:42-45.

- Lis K, Kuzawinska O, Bałkowiec-Iskra E. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors—state of knowledge. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:1175-1185.

- Kobayashi T, Yokoyama T, Ito S, et al. Periodontal and serum protein profiles in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab. J Periodontol. 2014;85:1480-1488.

Psoriasis is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory systemic disorder of the skin with an incidence of 2% to 3% and is estimated to affect 125 million individuals worldwide.1 Environmental triggers of disease modulation may include cutaneous microbiota, smoking, alcohol use, drugs (ie, beta-blockers, lithium, antimalarials), stress, and trauma.2 Comorbidities associated with cutaneous lesions include psoriatic arthritis, Crohn disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, stroke, and cardiovascular disease.3 In some studies, patients with psoriasis also had a 24% to 27% increased propensity for periodontal bone loss versus 10% of controls.4,5

Oral psoriasis is rare and case reports have been preferentially published in dental journals, usually with regard to glossal lesions, leaving gingival and palatal psoriatic involvement infrequently reported in the dermatologic literature.6,7 In fact, oral assessments involving 535 psoriatic patients from a dermatology center only yielded cases of geographic and fissured tongue.8 Another study at a psoriasis clinic found 3.8% (21/547) of patients with geographic tongue, 3.1% (17/547) with buccal mucosal plaques, and only 0.4% (2/547) with palatal lesions.9 To extend the knowledge of oral psoriasis, we provide the clinical and histopathologic findings of a patient with synchronous oral and cutaneous psoriatic lesions that responded well to the administration of adalimumab for management of recurrent cutaneous disease.

Case Report

A 51-year-old man presented to the attending periodontist for comprehensive treatment of multiple quadrants of gingival recession. His medical history was remarkable for psoriasis; Prinzmetal angina, which led to myocardial infarction; and diverticulitis. The cutaneous psoriasis began approximately 18 years prior to the current presentation and was initially managed with various topical therapeutics. At an 11-year follow-up, the patient was experiencing poor lesional control as well as severe pruritus and was prescribed etanercept by a dermatologist. His inconsistent compliance with frequency and dosing failed to achieve satisfactory disease suppression and etanercept was discontinued after approximately 2.5 years. Two years later the patient was switched to adalimumab by a dermatologist, and around this time he had developed psoriatic arthritis of the hands and knees and pitting of the nail plates. The patient elected to discontinue adalimumab usage after 3 years due to successful management of the skin lesions, cost considerations, and his perception that the psoriasis could “remain in remission.” After a 6-month lapse, the patient resumed adalimumab due to cutaneous lesional recurrence (Figure 1A).

At the current presentation, an oral examination performed 2 days after the reinstitution of adalim-umab revealed generalized severe gingivitis with an atypical inflammatory response that extended from just beyond the mucogingival junction to the marginal gingiva. The gingiva also appeared edematous with a conspicuously granular surface (Figure 1B). The hard palate displayed multiple red macules of varying sizes (Figure 1C). A maxillary gingival biopsy demonstrated hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, spongiosis, acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, numerous collections of neutrophils (Munro microabscesses), and abundant lymphocytes in the subjacent connective tissue (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal hyphae. These features were consistent with oral mucosal psoriasis.

At a 2-month follow-up, the biopsy site had healed without incident and without loss of the gingival architecture. There was an almost-complete resolution of the gingival erythema (Figure 3A) and the patient has since noticed a lack of bleeding using floss. Additionally, the red macules on the palate were no longer present (Figure 3B). The cutaneous plaques were greatly reduced in size and the patient experienced a proportionate decline in pruritus. Based on the uneventful surgical biopsy procedure, the patient was advised to undergo gingival grafting and has not returned for periodontal care.

Comment

Psoriasis of the oral cavity is rare and typically occurs on the tongue and less frequently on the hard palate, lip, buccal mucosa, and gingiva.2,7 The lesions are almost always concordant with cutaneous psoriasis, and only sporadic examples exclusive to the oral mucosa have been recognized.7,10 Gingival psoriasis usually is described as intensely erythematous and occasionally laced with white scaly streaks involving the marginal gingiva that extend toward the mucogingival junction. In general, the erythematous presentation of gingival psoriasis may not be commensurate with the degree of inflammation induced by dental plaque-based periodontal disease. Doben11 documented gingival psoriasis as appearing “deeply stippled and grainy” and commented that the tissue was “friable” and incapable of maintaining a “clean incision line” during periodontal surgery. In our patient, the gingiva also had exhibited a granular surface. Patients with oral psoriasis often report soreness or a burning sensation of the gingiva, which may easily bleed on manipulation or brushing the teeth, whereas other patients are asymptomatic,12 as in our case. Psoriasis of the hard palate usually presents as multiple painless red macules. Unlike cutaneous psoriasis, oral lesions rarely evoke pruritus.10 Histopathologically, oral psoriasis bears a striking resemblance to its cutaneous counterpart. The epithelium has a pronounced parakeratinized surface with elongated rete ridges and aggregations of Munro microabscesses. The connective tissue often is composed of dilated capillaries that closely approximate the epithelium as well as infiltrations of lymphocytes. Specimens suspected for oral psoriasis should routinely be stained with periodic acid–Schiff to rule out candidiasis coinfection. The microscopic findings of our patient were congruent with prior reports of oral psoriasis.7,10-12 Some clinicians have questioned if psoriasis can actually occur in the oral cavity, but most authorities in the field have recognized its true existence, as evidenced by various shared HLA antigens, specifically HLA-Cw.13

Another group of oral lesions collectively referred to as psoriasiform mucositis, notably geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis, erythema migrans) and its extraglossal variant geographic stomatitis,14,15 have histopathologic features and HLAs similar to those seen in cutaneous psoriasis.13 Interestingly, geographic tongue has been found in 3.8% to 9.1% of cohorts with cutaneous psoriasis,8,9 but in the extant population, the vast majority of patients with oral psoriasiform mucositis do not have cutaneous psoriasis. Other differential diagnoses for gingival psoriasis are lichen planus, human immunodeficiency virus–associated periodontitis, desquamative gingivitis, plasma cell gingivitis, erythematous candidiasis, mucous membrane pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, leukemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, orofacial granulomatosis, localized juvenile spongiotic gingivitis hyperplasia, and primary gingivostomatitis.

Management of gingival psoriasis focuses on strategies to reduce inflammation and discomfort and measures to achieve meticulous oral plaque control. Judicious efforts should be exercised to avoid oral soft-tissue injury when performing periodontal scaling, although it has not been established whether gingival psoriasis is associated with the Köbner phenomenon, as seen with cutaneous lesions. Adjunctive measures employed for symptomatic patients have involved the use of corticosteroids (eg, lesional injection, oral rinse, systemic) and oral rinses with retinoic acid, chlorhexidine gluconate, and warm saline.7,10,16 Prolonged utilization of corticosteroids, however, may necessitate supplemental administration of antifungal agents.

This case report represents a rare documentation of a successful outcome of gingival and palatal psoriasis subsequent to the reinstitution of adalimumab solely for treatment of recurrent cutaneous disease. There likely is a pharmacologic basis for the amelioration of oral psoriasis in our patient. Adalimumab is a bivalent IgG monoclonal antibody that binds to activated dermal dendritic cell receptors of tumor necrosis factor α, thereby attenuating a cytokine-derived inflammatory response and apoptosis.17 In fact, patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed notable reductions in both gingival inflammation and bleeding following a 3-month regimen of adalimumab.18

Conclusion

Practitioners should be aware of the phenotypic overlap of cutaneous and oral psoriasis, particularly involving the gingiva and palate. It is recommended that psoriasis patients routinely receive a dental prophylaxis and engage in oral hygiene efforts to reduce the presence of oral microbiota. Furthermore, it is emphasized that psoriatic patients who maintain an atypical erythematous presentation on the oral mucosa undergo a biopsy for identification of the lesions and correlation with disease dissemination. Prospective studies are needed to characterize the clinical courses of oral psoriasis, ascertain their correlative behavior with cutaneous flares, and determine if lesional improvement can be achieved with the use of biologic agents or other therapeutic modalities.

Psoriasis is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory systemic disorder of the skin with an incidence of 2% to 3% and is estimated to affect 125 million individuals worldwide.1 Environmental triggers of disease modulation may include cutaneous microbiota, smoking, alcohol use, drugs (ie, beta-blockers, lithium, antimalarials), stress, and trauma.2 Comorbidities associated with cutaneous lesions include psoriatic arthritis, Crohn disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, stroke, and cardiovascular disease.3 In some studies, patients with psoriasis also had a 24% to 27% increased propensity for periodontal bone loss versus 10% of controls.4,5

Oral psoriasis is rare and case reports have been preferentially published in dental journals, usually with regard to glossal lesions, leaving gingival and palatal psoriatic involvement infrequently reported in the dermatologic literature.6,7 In fact, oral assessments involving 535 psoriatic patients from a dermatology center only yielded cases of geographic and fissured tongue.8 Another study at a psoriasis clinic found 3.8% (21/547) of patients with geographic tongue, 3.1% (17/547) with buccal mucosal plaques, and only 0.4% (2/547) with palatal lesions.9 To extend the knowledge of oral psoriasis, we provide the clinical and histopathologic findings of a patient with synchronous oral and cutaneous psoriatic lesions that responded well to the administration of adalimumab for management of recurrent cutaneous disease.

Case Report

A 51-year-old man presented to the attending periodontist for comprehensive treatment of multiple quadrants of gingival recession. His medical history was remarkable for psoriasis; Prinzmetal angina, which led to myocardial infarction; and diverticulitis. The cutaneous psoriasis began approximately 18 years prior to the current presentation and was initially managed with various topical therapeutics. At an 11-year follow-up, the patient was experiencing poor lesional control as well as severe pruritus and was prescribed etanercept by a dermatologist. His inconsistent compliance with frequency and dosing failed to achieve satisfactory disease suppression and etanercept was discontinued after approximately 2.5 years. Two years later the patient was switched to adalimumab by a dermatologist, and around this time he had developed psoriatic arthritis of the hands and knees and pitting of the nail plates. The patient elected to discontinue adalimumab usage after 3 years due to successful management of the skin lesions, cost considerations, and his perception that the psoriasis could “remain in remission.” After a 6-month lapse, the patient resumed adalimumab due to cutaneous lesional recurrence (Figure 1A).

At the current presentation, an oral examination performed 2 days after the reinstitution of adalim-umab revealed generalized severe gingivitis with an atypical inflammatory response that extended from just beyond the mucogingival junction to the marginal gingiva. The gingiva also appeared edematous with a conspicuously granular surface (Figure 1B). The hard palate displayed multiple red macules of varying sizes (Figure 1C). A maxillary gingival biopsy demonstrated hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, spongiosis, acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, numerous collections of neutrophils (Munro microabscesses), and abundant lymphocytes in the subjacent connective tissue (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal hyphae. These features were consistent with oral mucosal psoriasis.

At a 2-month follow-up, the biopsy site had healed without incident and without loss of the gingival architecture. There was an almost-complete resolution of the gingival erythema (Figure 3A) and the patient has since noticed a lack of bleeding using floss. Additionally, the red macules on the palate were no longer present (Figure 3B). The cutaneous plaques were greatly reduced in size and the patient experienced a proportionate decline in pruritus. Based on the uneventful surgical biopsy procedure, the patient was advised to undergo gingival grafting and has not returned for periodontal care.

Comment

Psoriasis of the oral cavity is rare and typically occurs on the tongue and less frequently on the hard palate, lip, buccal mucosa, and gingiva.2,7 The lesions are almost always concordant with cutaneous psoriasis, and only sporadic examples exclusive to the oral mucosa have been recognized.7,10 Gingival psoriasis usually is described as intensely erythematous and occasionally laced with white scaly streaks involving the marginal gingiva that extend toward the mucogingival junction. In general, the erythematous presentation of gingival psoriasis may not be commensurate with the degree of inflammation induced by dental plaque-based periodontal disease. Doben11 documented gingival psoriasis as appearing “deeply stippled and grainy” and commented that the tissue was “friable” and incapable of maintaining a “clean incision line” during periodontal surgery. In our patient, the gingiva also had exhibited a granular surface. Patients with oral psoriasis often report soreness or a burning sensation of the gingiva, which may easily bleed on manipulation or brushing the teeth, whereas other patients are asymptomatic,12 as in our case. Psoriasis of the hard palate usually presents as multiple painless red macules. Unlike cutaneous psoriasis, oral lesions rarely evoke pruritus.10 Histopathologically, oral psoriasis bears a striking resemblance to its cutaneous counterpart. The epithelium has a pronounced parakeratinized surface with elongated rete ridges and aggregations of Munro microabscesses. The connective tissue often is composed of dilated capillaries that closely approximate the epithelium as well as infiltrations of lymphocytes. Specimens suspected for oral psoriasis should routinely be stained with periodic acid–Schiff to rule out candidiasis coinfection. The microscopic findings of our patient were congruent with prior reports of oral psoriasis.7,10-12 Some clinicians have questioned if psoriasis can actually occur in the oral cavity, but most authorities in the field have recognized its true existence, as evidenced by various shared HLA antigens, specifically HLA-Cw.13

Another group of oral lesions collectively referred to as psoriasiform mucositis, notably geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis, erythema migrans) and its extraglossal variant geographic stomatitis,14,15 have histopathologic features and HLAs similar to those seen in cutaneous psoriasis.13 Interestingly, geographic tongue has been found in 3.8% to 9.1% of cohorts with cutaneous psoriasis,8,9 but in the extant population, the vast majority of patients with oral psoriasiform mucositis do not have cutaneous psoriasis. Other differential diagnoses for gingival psoriasis are lichen planus, human immunodeficiency virus–associated periodontitis, desquamative gingivitis, plasma cell gingivitis, erythematous candidiasis, mucous membrane pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, leukemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, orofacial granulomatosis, localized juvenile spongiotic gingivitis hyperplasia, and primary gingivostomatitis.

Management of gingival psoriasis focuses on strategies to reduce inflammation and discomfort and measures to achieve meticulous oral plaque control. Judicious efforts should be exercised to avoid oral soft-tissue injury when performing periodontal scaling, although it has not been established whether gingival psoriasis is associated with the Köbner phenomenon, as seen with cutaneous lesions. Adjunctive measures employed for symptomatic patients have involved the use of corticosteroids (eg, lesional injection, oral rinse, systemic) and oral rinses with retinoic acid, chlorhexidine gluconate, and warm saline.7,10,16 Prolonged utilization of corticosteroids, however, may necessitate supplemental administration of antifungal agents.

This case report represents a rare documentation of a successful outcome of gingival and palatal psoriasis subsequent to the reinstitution of adalimumab solely for treatment of recurrent cutaneous disease. There likely is a pharmacologic basis for the amelioration of oral psoriasis in our patient. Adalimumab is a bivalent IgG monoclonal antibody that binds to activated dermal dendritic cell receptors of tumor necrosis factor α, thereby attenuating a cytokine-derived inflammatory response and apoptosis.17 In fact, patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed notable reductions in both gingival inflammation and bleeding following a 3-month regimen of adalimumab.18

Conclusion

Practitioners should be aware of the phenotypic overlap of cutaneous and oral psoriasis, particularly involving the gingiva and palate. It is recommended that psoriasis patients routinely receive a dental prophylaxis and engage in oral hygiene efforts to reduce the presence of oral microbiota. Furthermore, it is emphasized that psoriatic patients who maintain an atypical erythematous presentation on the oral mucosa undergo a biopsy for identification of the lesions and correlation with disease dissemination. Prospective studies are needed to characterize the clinical courses of oral psoriasis, ascertain their correlative behavior with cutaneous flares, and determine if lesional improvement can be achieved with the use of biologic agents or other therapeutic modalities.

- Gupta R, Debbaneh MG, Liao W. Genetic epidemiology of psoriasis. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2014;3:61-78.

- Younai FS, Phelan JA. Oral mucositis with features of psoriasis: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:61-67.

- Xu T, Zhang YH. Association of psoriasis with stroke and myocardial infarction: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1345-1350.

- Lazaridou E, Tsikrikoni A, Fotiadou C, et al. Association of chronic plaque psoriasis and severe periodontitis: a hospital based case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:967-972.

- Skudutyte-Rysstad R, Slevolden EM, Hansen BF, et al. Association between moderate to severe psoriasis and periodontitis in a Scandinavian population. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:139.

- Zunt SL, Tomich CE. Erythema migrans—a psoriasiform lesion of the oral mucosa. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:1067-1070.

- Reis V, Artico G, Seo J, et al. Psoriasiform mucositis on the gingival and palatal mucosae treated with retinoic-acid mouthwash. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:113-115.

- Germi L, De Giorgi V, Bergamo F, et al. Psoriasis and oral lesions: multicentric study of oral mucosa diseases Italian group (GIPMO). Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11.

- Kaur I, Handa S, Kumar B. Oral lesions in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:78-79.

- Brayshaw HA, Orban B. Psoriasis gingivae. J Periodontol. 1953;24:156-160.

- Doben DI. Psoriasis of the attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1976;47:38-40.

- Mattsson U, Warfvinge G, Jontell M. Oral psoriasis—a diagnostic dilemma: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;120:e183-e189.

- Dermatologic diseases. In: Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, et al, eds. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009:792-794.

- Brooks JK, Balciunas BA. Geographic stomatitis: review of the literature and report of five cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115:421-424.

- Brooks JK, Nikitakis NG. Multiple mucosal lesions. erythema migrans. Gen Dent. 2007;55:160, 163.

- Ulmansky M, Michelle R, Azaz B. Oral psoriasis: report of six new cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:42-45.

- Lis K, Kuzawinska O, Bałkowiec-Iskra E. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors—state of knowledge. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:1175-1185.

- Kobayashi T, Yokoyama T, Ito S, et al. Periodontal and serum protein profiles in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab. J Periodontol. 2014;85:1480-1488.

- Gupta R, Debbaneh MG, Liao W. Genetic epidemiology of psoriasis. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2014;3:61-78.

- Younai FS, Phelan JA. Oral mucositis with features of psoriasis: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:61-67.

- Xu T, Zhang YH. Association of psoriasis with stroke and myocardial infarction: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1345-1350.

- Lazaridou E, Tsikrikoni A, Fotiadou C, et al. Association of chronic plaque psoriasis and severe periodontitis: a hospital based case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:967-972.

- Skudutyte-Rysstad R, Slevolden EM, Hansen BF, et al. Association between moderate to severe psoriasis and periodontitis in a Scandinavian population. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:139.

- Zunt SL, Tomich CE. Erythema migrans—a psoriasiform lesion of the oral mucosa. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:1067-1070.

- Reis V, Artico G, Seo J, et al. Psoriasiform mucositis on the gingival and palatal mucosae treated with retinoic-acid mouthwash. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:113-115.

- Germi L, De Giorgi V, Bergamo F, et al. Psoriasis and oral lesions: multicentric study of oral mucosa diseases Italian group (GIPMO). Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11.

- Kaur I, Handa S, Kumar B. Oral lesions in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:78-79.

- Brayshaw HA, Orban B. Psoriasis gingivae. J Periodontol. 1953;24:156-160.

- Doben DI. Psoriasis of the attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1976;47:38-40.

- Mattsson U, Warfvinge G, Jontell M. Oral psoriasis—a diagnostic dilemma: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;120:e183-e189.

- Dermatologic diseases. In: Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, et al, eds. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009:792-794.

- Brooks JK, Balciunas BA. Geographic stomatitis: review of the literature and report of five cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115:421-424.

- Brooks JK, Nikitakis NG. Multiple mucosal lesions. erythema migrans. Gen Dent. 2007;55:160, 163.

- Ulmansky M, Michelle R, Azaz B. Oral psoriasis: report of six new cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:42-45.

- Lis K, Kuzawinska O, Bałkowiec-Iskra E. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors—state of knowledge. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:1175-1185.

- Kobayashi T, Yokoyama T, Ito S, et al. Periodontal and serum protein profiles in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab. J Periodontol. 2014;85:1480-1488.

Practice Points

- A subset of patients with cutaneous psoriasis may be associated with oral psoriatic outbreaks.

- Oral psoriasis presents as an atypical inflammatory response, and histopathologic assessment is recommended for lesional identity.

- Use of adalimumab for management of cutaneous psoriasis may demonstrate efficacy for oral psoriasis.