User login

A new certification for FPs

A new certification process for obstetrics in family medicine has begun under the auspices of the American Board of Physician Specialties (ABPS). The new Board of Certification in Family Medicine Obstetrics (BCFMO) is open to family physicians who have completed a fellowship tract or clinical practice tract in obstetrics. Candidates must complete written and oral examinations and proctor-observed surgical competency testing before receiving certification. To date, 25 family physicians have completed the testing process and received certification. In this article, I describe the genesis of this certification and the process that aspiring applicants can expect.

Working to meet a long-standing need

Twenty-five years ago, board certification was admirable, but not essential to practice medicine. Today it is imperative. In family medicine, most physicians completing residency training seek board certification in that specialty. Many of them then pursue training in fellowships, with recognition usually conferred by a certificate of added qualification. Obstetrics has been such an area of specialized clinical focus in family medicine, especially for those serving rural communities.1,2 And women’s health and routine pregnancy care are an integral part of family medicine and the medical home.3

In 1984, Paul D. Mozley, MD, founded Postgraduate Obstetrics Fellowship Training at the University of Alabama School of Medicine in Tuscaloosa, to address the shortage of obstetric providers in rural and underserved areas and a desire by graduating family medicine residents to obtain additional training in obstetrics. Obstetrics fellowships are usually one year in length and include operative obstetrics with cesarean section and instrumental vaginal delivery, limited gynecologic surgery, and office gynecology.4,5

Family medicine and obstetrics and gynecology organizations have also been working together to continually improve care for obstetric patients. One example is the formation of a Joint Task Force in 1998 by the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which developed core educational guidelines in OB/GYN care for training family medicine residents.6 Between 2000 and 2005, parties from both specialties approached a number of national organizations about an examination and certification initiative. Although all organizations were supportive and recognized the need, an examination and certification never materialized.

A like-minded certifying partner emerges

In 2005, I made a formal presentation to the ABPS—one of 3 board-certifying organizations in the United States—proposing a program for examination and board certification of family medicine physicians completing obstetrics fellowships.7 In response, the ABPS created a Task Force for the Certification of Family Physicians Practicing Obstetrics, composed of family physicians and obstetrician/gynecologists. The Task Force conducted a nationwide survey of hospitals, hospital credentialing committees, malpractice insurance carriers, obstetrics fellowship programs, and family physicians regarding the importance of examination and certification, a certificate of added qualification, and a separate board of certification for family physicians practicing obstetrics.8 The aggregate response overwhelmingly favored board certification.

In 2006, responding to the increasingly clear need, the ABPS created the American Board of Family Practice Obstetrics, which is now known as the BCFMO.

What the BcFMO examination entails

From 2006 to 2008, using major textbooks on obstetrics, the BCFMO selected 873 test items that were placed in a bank for review and comment by all board members. The BCFMO then prepared questions of equal competency as the examination in obstetrics and gynecology. Questions of equal competency to both specialties were deemed important to give the certification process validity. Using the same text sources, the Board prepared additional items in a form usable for oral examination. The final written examination comprises 200 questions; the oral examination has 4 questions.

Surgical competency testing

The BCFMO also includes observed surgical competency as part of the process. Documentation of physician competency is emphasized by The Joint Commission. In this part of the testing, a Board-approved local proctor—a family physician practicing obstetrics, a general surgeon who performs cesarean sections, or an obstetrician/ gynecologist—is asked to observe and evaluate the surgical competency of a candidate for examination.

Credentialing for the examinations

Eligible applicants are those who, within the last 5 years, have satisfactorily completed (verified in writing by the fellowship director) a 12-month full-time Obstetrics or Maternal and Child Care Fellowship recognized by the BCFMO (http://www.abpsus.org/userfiles/files/BFMOFellowship.pdf). Applicants who have not completed an obstetrics fellowship but have been actively engaged in the practice of surgical obstetrics for at least 5 years may present a case list of the previous 2 years. All applicants to either tract must have performed a minimum of 100 vaginal deliveries and a verified case list of 50 cesarean sections within the last 5 years.9

Applicants successfully completing the computer-based written examination are required to submit verification of competency in surgical obstetrics described earlier, and then successfully complete the oral examination. The first written examination was administered in May 2009, and the oral examination in September 2009. Subsequent written and oral examinations were administered in 2010.

The next written examination is scheduled for October 2011. Successful completion of the written and oral examinations, surgical proctoring, background check, National Practitioner Data Bank query, and payment of appropriate fees constitute board certification in Family Medicine Obstetrics. Twenty-five family physicians have so far received board certification.

Future of the BCFMO

With its first 2 rounds of examination and certification successfully completed, the BCFMO plans to pursue the following:

- formal ceremony confirming certificate recipients’ diplomat status in the ABPS

- creation of a recertification process

- development of an appeals process

- establishment of an academy, college, or society for fellows

- acceptance by hospitals, malpractice insurance carriers, state medical societies, and licensing commissions

- ABPS accreditation of training programs

- BCFMO membership in the American Medical Association

- BCFMO membership in the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Interested in learning more? Visit http://www.abpsus.org/family-medicine-obstetrics, or call (813) 433-2277.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel M. Avery, MD, University of Alabama School of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 850 5th Avenue East, Tuscaloosa, AL 35401-7419; [email protected]

1. Heider A, Neely B, Bell L. Cesarean delivery results in a family medicine residency using a specific training model. Fam Med. 2006;38:103-109.

2. Deutchman M, Connor P, Gobbo R, et al. Outcomes of cesarean sections performed by family physicians and the training they received: a fifteen-year retrospective study. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1995;8:81-90.

3. Larimore WL, Sapolsky BS. Maternity care in family medicine: economics and malpractice. J Fam Pract. 1995;40:153-160.

4. Avery DM, Hooper DE, Garris CE. Minilaparotomy for the surgical management of ectopic pregnancy for family medicine obstetricians. Am J Clin Med. 2009;6:72-73.

5. Avery DM, Hooper DE. Cesarean hysterectomy for family medicine physicians practicing obstetrics. Am J Clin Med. 2009;6:68-71.

6. American Family Physician. Recommended core educational guidelines for family practice residents: maternity and gynecologic care. July 1998. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/afp/980700ap/corematr.html. Accessed March 1, 2009.

7. American Board of Physician Specialties. Annual Leadership Meeting; June 2005;Naples, FL.

8. Avery DM, Garris CE. Board certification versus certificate of added qualification in obstetrics Am J Clin Med. 2006;3:16-18.

9. American Board of Physician Specialties. Family medicine obstetrics eligibility. February 2008. Available at: http://www.abpsus.org/family-medicine-obstetrics-eligibility. Accessed March 1, 2009.

A new certification process for obstetrics in family medicine has begun under the auspices of the American Board of Physician Specialties (ABPS). The new Board of Certification in Family Medicine Obstetrics (BCFMO) is open to family physicians who have completed a fellowship tract or clinical practice tract in obstetrics. Candidates must complete written and oral examinations and proctor-observed surgical competency testing before receiving certification. To date, 25 family physicians have completed the testing process and received certification. In this article, I describe the genesis of this certification and the process that aspiring applicants can expect.

Working to meet a long-standing need

Twenty-five years ago, board certification was admirable, but not essential to practice medicine. Today it is imperative. In family medicine, most physicians completing residency training seek board certification in that specialty. Many of them then pursue training in fellowships, with recognition usually conferred by a certificate of added qualification. Obstetrics has been such an area of specialized clinical focus in family medicine, especially for those serving rural communities.1,2 And women’s health and routine pregnancy care are an integral part of family medicine and the medical home.3

In 1984, Paul D. Mozley, MD, founded Postgraduate Obstetrics Fellowship Training at the University of Alabama School of Medicine in Tuscaloosa, to address the shortage of obstetric providers in rural and underserved areas and a desire by graduating family medicine residents to obtain additional training in obstetrics. Obstetrics fellowships are usually one year in length and include operative obstetrics with cesarean section and instrumental vaginal delivery, limited gynecologic surgery, and office gynecology.4,5

Family medicine and obstetrics and gynecology organizations have also been working together to continually improve care for obstetric patients. One example is the formation of a Joint Task Force in 1998 by the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which developed core educational guidelines in OB/GYN care for training family medicine residents.6 Between 2000 and 2005, parties from both specialties approached a number of national organizations about an examination and certification initiative. Although all organizations were supportive and recognized the need, an examination and certification never materialized.

A like-minded certifying partner emerges

In 2005, I made a formal presentation to the ABPS—one of 3 board-certifying organizations in the United States—proposing a program for examination and board certification of family medicine physicians completing obstetrics fellowships.7 In response, the ABPS created a Task Force for the Certification of Family Physicians Practicing Obstetrics, composed of family physicians and obstetrician/gynecologists. The Task Force conducted a nationwide survey of hospitals, hospital credentialing committees, malpractice insurance carriers, obstetrics fellowship programs, and family physicians regarding the importance of examination and certification, a certificate of added qualification, and a separate board of certification for family physicians practicing obstetrics.8 The aggregate response overwhelmingly favored board certification.

In 2006, responding to the increasingly clear need, the ABPS created the American Board of Family Practice Obstetrics, which is now known as the BCFMO.

What the BcFMO examination entails

From 2006 to 2008, using major textbooks on obstetrics, the BCFMO selected 873 test items that were placed in a bank for review and comment by all board members. The BCFMO then prepared questions of equal competency as the examination in obstetrics and gynecology. Questions of equal competency to both specialties were deemed important to give the certification process validity. Using the same text sources, the Board prepared additional items in a form usable for oral examination. The final written examination comprises 200 questions; the oral examination has 4 questions.

Surgical competency testing

The BCFMO also includes observed surgical competency as part of the process. Documentation of physician competency is emphasized by The Joint Commission. In this part of the testing, a Board-approved local proctor—a family physician practicing obstetrics, a general surgeon who performs cesarean sections, or an obstetrician/ gynecologist—is asked to observe and evaluate the surgical competency of a candidate for examination.

Credentialing for the examinations

Eligible applicants are those who, within the last 5 years, have satisfactorily completed (verified in writing by the fellowship director) a 12-month full-time Obstetrics or Maternal and Child Care Fellowship recognized by the BCFMO (http://www.abpsus.org/userfiles/files/BFMOFellowship.pdf). Applicants who have not completed an obstetrics fellowship but have been actively engaged in the practice of surgical obstetrics for at least 5 years may present a case list of the previous 2 years. All applicants to either tract must have performed a minimum of 100 vaginal deliveries and a verified case list of 50 cesarean sections within the last 5 years.9

Applicants successfully completing the computer-based written examination are required to submit verification of competency in surgical obstetrics described earlier, and then successfully complete the oral examination. The first written examination was administered in May 2009, and the oral examination in September 2009. Subsequent written and oral examinations were administered in 2010.

The next written examination is scheduled for October 2011. Successful completion of the written and oral examinations, surgical proctoring, background check, National Practitioner Data Bank query, and payment of appropriate fees constitute board certification in Family Medicine Obstetrics. Twenty-five family physicians have so far received board certification.

Future of the BCFMO

With its first 2 rounds of examination and certification successfully completed, the BCFMO plans to pursue the following:

- formal ceremony confirming certificate recipients’ diplomat status in the ABPS

- creation of a recertification process

- development of an appeals process

- establishment of an academy, college, or society for fellows

- acceptance by hospitals, malpractice insurance carriers, state medical societies, and licensing commissions

- ABPS accreditation of training programs

- BCFMO membership in the American Medical Association

- BCFMO membership in the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Interested in learning more? Visit http://www.abpsus.org/family-medicine-obstetrics, or call (813) 433-2277.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel M. Avery, MD, University of Alabama School of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 850 5th Avenue East, Tuscaloosa, AL 35401-7419; [email protected]

A new certification process for obstetrics in family medicine has begun under the auspices of the American Board of Physician Specialties (ABPS). The new Board of Certification in Family Medicine Obstetrics (BCFMO) is open to family physicians who have completed a fellowship tract or clinical practice tract in obstetrics. Candidates must complete written and oral examinations and proctor-observed surgical competency testing before receiving certification. To date, 25 family physicians have completed the testing process and received certification. In this article, I describe the genesis of this certification and the process that aspiring applicants can expect.

Working to meet a long-standing need

Twenty-five years ago, board certification was admirable, but not essential to practice medicine. Today it is imperative. In family medicine, most physicians completing residency training seek board certification in that specialty. Many of them then pursue training in fellowships, with recognition usually conferred by a certificate of added qualification. Obstetrics has been such an area of specialized clinical focus in family medicine, especially for those serving rural communities.1,2 And women’s health and routine pregnancy care are an integral part of family medicine and the medical home.3

In 1984, Paul D. Mozley, MD, founded Postgraduate Obstetrics Fellowship Training at the University of Alabama School of Medicine in Tuscaloosa, to address the shortage of obstetric providers in rural and underserved areas and a desire by graduating family medicine residents to obtain additional training in obstetrics. Obstetrics fellowships are usually one year in length and include operative obstetrics with cesarean section and instrumental vaginal delivery, limited gynecologic surgery, and office gynecology.4,5

Family medicine and obstetrics and gynecology organizations have also been working together to continually improve care for obstetric patients. One example is the formation of a Joint Task Force in 1998 by the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which developed core educational guidelines in OB/GYN care for training family medicine residents.6 Between 2000 and 2005, parties from both specialties approached a number of national organizations about an examination and certification initiative. Although all organizations were supportive and recognized the need, an examination and certification never materialized.

A like-minded certifying partner emerges

In 2005, I made a formal presentation to the ABPS—one of 3 board-certifying organizations in the United States—proposing a program for examination and board certification of family medicine physicians completing obstetrics fellowships.7 In response, the ABPS created a Task Force for the Certification of Family Physicians Practicing Obstetrics, composed of family physicians and obstetrician/gynecologists. The Task Force conducted a nationwide survey of hospitals, hospital credentialing committees, malpractice insurance carriers, obstetrics fellowship programs, and family physicians regarding the importance of examination and certification, a certificate of added qualification, and a separate board of certification for family physicians practicing obstetrics.8 The aggregate response overwhelmingly favored board certification.

In 2006, responding to the increasingly clear need, the ABPS created the American Board of Family Practice Obstetrics, which is now known as the BCFMO.

What the BcFMO examination entails

From 2006 to 2008, using major textbooks on obstetrics, the BCFMO selected 873 test items that were placed in a bank for review and comment by all board members. The BCFMO then prepared questions of equal competency as the examination in obstetrics and gynecology. Questions of equal competency to both specialties were deemed important to give the certification process validity. Using the same text sources, the Board prepared additional items in a form usable for oral examination. The final written examination comprises 200 questions; the oral examination has 4 questions.

Surgical competency testing

The BCFMO also includes observed surgical competency as part of the process. Documentation of physician competency is emphasized by The Joint Commission. In this part of the testing, a Board-approved local proctor—a family physician practicing obstetrics, a general surgeon who performs cesarean sections, or an obstetrician/ gynecologist—is asked to observe and evaluate the surgical competency of a candidate for examination.

Credentialing for the examinations

Eligible applicants are those who, within the last 5 years, have satisfactorily completed (verified in writing by the fellowship director) a 12-month full-time Obstetrics or Maternal and Child Care Fellowship recognized by the BCFMO (http://www.abpsus.org/userfiles/files/BFMOFellowship.pdf). Applicants who have not completed an obstetrics fellowship but have been actively engaged in the practice of surgical obstetrics for at least 5 years may present a case list of the previous 2 years. All applicants to either tract must have performed a minimum of 100 vaginal deliveries and a verified case list of 50 cesarean sections within the last 5 years.9

Applicants successfully completing the computer-based written examination are required to submit verification of competency in surgical obstetrics described earlier, and then successfully complete the oral examination. The first written examination was administered in May 2009, and the oral examination in September 2009. Subsequent written and oral examinations were administered in 2010.

The next written examination is scheduled for October 2011. Successful completion of the written and oral examinations, surgical proctoring, background check, National Practitioner Data Bank query, and payment of appropriate fees constitute board certification in Family Medicine Obstetrics. Twenty-five family physicians have so far received board certification.

Future of the BCFMO

With its first 2 rounds of examination and certification successfully completed, the BCFMO plans to pursue the following:

- formal ceremony confirming certificate recipients’ diplomat status in the ABPS

- creation of a recertification process

- development of an appeals process

- establishment of an academy, college, or society for fellows

- acceptance by hospitals, malpractice insurance carriers, state medical societies, and licensing commissions

- ABPS accreditation of training programs

- BCFMO membership in the American Medical Association

- BCFMO membership in the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Interested in learning more? Visit http://www.abpsus.org/family-medicine-obstetrics, or call (813) 433-2277.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel M. Avery, MD, University of Alabama School of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 850 5th Avenue East, Tuscaloosa, AL 35401-7419; [email protected]

1. Heider A, Neely B, Bell L. Cesarean delivery results in a family medicine residency using a specific training model. Fam Med. 2006;38:103-109.

2. Deutchman M, Connor P, Gobbo R, et al. Outcomes of cesarean sections performed by family physicians and the training they received: a fifteen-year retrospective study. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1995;8:81-90.

3. Larimore WL, Sapolsky BS. Maternity care in family medicine: economics and malpractice. J Fam Pract. 1995;40:153-160.

4. Avery DM, Hooper DE, Garris CE. Minilaparotomy for the surgical management of ectopic pregnancy for family medicine obstetricians. Am J Clin Med. 2009;6:72-73.

5. Avery DM, Hooper DE. Cesarean hysterectomy for family medicine physicians practicing obstetrics. Am J Clin Med. 2009;6:68-71.

6. American Family Physician. Recommended core educational guidelines for family practice residents: maternity and gynecologic care. July 1998. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/afp/980700ap/corematr.html. Accessed March 1, 2009.

7. American Board of Physician Specialties. Annual Leadership Meeting; June 2005;Naples, FL.

8. Avery DM, Garris CE. Board certification versus certificate of added qualification in obstetrics Am J Clin Med. 2006;3:16-18.

9. American Board of Physician Specialties. Family medicine obstetrics eligibility. February 2008. Available at: http://www.abpsus.org/family-medicine-obstetrics-eligibility. Accessed March 1, 2009.

1. Heider A, Neely B, Bell L. Cesarean delivery results in a family medicine residency using a specific training model. Fam Med. 2006;38:103-109.

2. Deutchman M, Connor P, Gobbo R, et al. Outcomes of cesarean sections performed by family physicians and the training they received: a fifteen-year retrospective study. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1995;8:81-90.

3. Larimore WL, Sapolsky BS. Maternity care in family medicine: economics and malpractice. J Fam Pract. 1995;40:153-160.

4. Avery DM, Hooper DE, Garris CE. Minilaparotomy for the surgical management of ectopic pregnancy for family medicine obstetricians. Am J Clin Med. 2009;6:72-73.

5. Avery DM, Hooper DE. Cesarean hysterectomy for family medicine physicians practicing obstetrics. Am J Clin Med. 2009;6:68-71.

6. American Family Physician. Recommended core educational guidelines for family practice residents: maternity and gynecologic care. July 1998. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/afp/980700ap/corematr.html. Accessed March 1, 2009.

7. American Board of Physician Specialties. Annual Leadership Meeting; June 2005;Naples, FL.

8. Avery DM, Garris CE. Board certification versus certificate of added qualification in obstetrics Am J Clin Med. 2006;3:16-18.

9. American Board of Physician Specialties. Family medicine obstetrics eligibility. February 2008. Available at: http://www.abpsus.org/family-medicine-obstetrics-eligibility. Accessed March 1, 2009.

What you should know about heterotopic pregnancy

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE 1: Pelvic pain and few signs of intrauterine pregnancy

A 24-year-old woman, para 1-0-0-1, visits the hospital emergency department complaining of pelvic pain. She says the pain arose suddenly and reports that she had a positive urine pregnancy test earlier in the week. When asked about her obstetric history, she reports vaginal delivery of an 8 lb, 8 oz infant at 38 weeks’ gestation 2 years earlier. Her human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level is 3,000 mIU/mL, but ultrasonography (US) reveals no evidence of pregnancy. She is discharged with instructions to follow up with her physician in 2 days.

When her abdominal pain worsens, she returns to the emergency department. Physical examination reveals significant tenderness of the abdomen and moderate to severe tenderness of the cervix upon motion. Transvaginal US shows a uterus of normal size with a 5-mm endometrial lining and no gestational sac. The patient’s abdomen is full of fluid, with large, hypodense areas adjacent to the uterus bilaterally but larger on the right. The preoperative diagnosis: ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

During the diagnostic laparoscopy that follows, approximately 500 mL of blood is discovered in the abdomen and pelvis, and a gestational sac is found to be densely adherent to the right pelvic sidewall, where the ureter nears the uterine vessels. The sac, which has partially separated from the sidewall, is bleeding.

The surgeon peels the sac off the sidewall and controls bleeding with electrocautery and liquid thrombin. The final pathology report describes the tissue as an organizing blood clot with trophoblasts, consistent with ectopic pregnancy.

At a follow-up visit 3 weeks later, the patient reports persistent symptoms of pregnancy. Repeat US reveals a twin intrauterine pregnancy with two sacs, only one of which has a heartbeat. One week later, US shows confluence of the sacs, with a single viable fetus at 8 weeks and 2 days of gestation.

Could heterotopic pregnancy have been diagnosed earlier?

This case illustrates challenges inherent in the diagnosis of heterotopic pregnancy, which is much more common today than it was when it was first described 300 years ago. Incidence has increased from approximately 1 in 30,000 pregnancies to 1 in 2,600 pregnancies annually. When assisted reproductive technologies (ART) are used, the incidence may be as high as 1 in 100 pregnancies.1

The rising incidence suggests that the diagnosis of intrauterine pregnancy can no longer be used to exclude the presence of ectopic pregnancy, and vice versa. Instead, steps must be taken to rule out both when a woman exhibits pain and signs of pregnancy.

In this article, we discuss the causes, diagnosis, and treatment of heterotopic pregnancy, including the necessity of a high index of suspicion, the unreliability of US imaging in 50% of cases, and the need to avoid curettage in the treatment of ectopic pregnancy until an empty uterus can be confirmed.

Duverney was the first to report heterotopic pregnancy, in 1708, after finding an intrauterine pregnancy during the autopsy of a woman who had died from a ruptured ectopic pregnancy.1 It was 165 years, however, before the first review of the phenomenon was written.2 By 1970, only 479 such cases had been reported.20

Determining incidence remains a challenge—except that it is rising

In 1948, DeVoe and Pratt calculated the incidence of heterotopic pregnancy by multiplying the incidence of two-ovum pregnancy by the incidence of ectopic pregnancy, reaching an estimate of 1 in 30,000 pregnancies annually.2

In 1965, Rothman and Shapiro found that only about 500 cases of heterotopic pregnancy had been reported cumulatively.7 They reasoned that, if the incidence of fraternal twins is 1 in 110 and the incidence of ectopic pregnancy is 1 in 250, heterotopic pregnancy should occur at a rate of 1 in 27,500 gestations.7 They also speculated that many heterotopic pregnancies go undiagnosed because of early pregnancy loss.7

In 1971, Payne and colleagues hypothesized that ovulation-induction agents increase the incidence of heterotopic pregnancy, and McLain and associates reached a similar conclusion in 1987.9 The incidence of multiple pregnancy after oral ovulation induction is 8% to 10%, and it is 20% to 50% with injectable agents.9 In 1994, Crabtree and associates reported that both abdominal and heterotopic pregnancies appear to be increasing in incidence.17

Today, the incidence of heterotopic pregnancy is thought to be about 1 in 2,600 pregnancies annually—primarily because of assisted reproduction.2 The calculated risk of heterotopic pregnancy is 1 in 119, and it rises to 1 in 45 with embryo transfer.8

Why is heterotopic pregnancy on the increase?

One reason may be the increase in ectopic pregnancy. Among the factors contributing to the rising incidence of ectopic pregnancy are:

- pelvic adhesive disease

- effects of diethylstilbestrol (DES) on the genital tract

- antibiotic-induced tubal disease

- use of an intrauterine device (IUD)

- voluntary restriction of family size

- iatrogenic curettage of intrauterine pregnancy during surgery for ectopic pregnancy

- pregnancy termination

- history of surgery to treat infertility, ectopic pregnancy, or tubal adhesions

- improvement in the assay used to measure gonadotropin

- improvement in ultrasonography.2-4

A previous ectopic pregnancy is a risk factor for ectopic pregnancy as well as for heterotopic pregnancy.5

Pelvic infection, antibiotic-induced tubal disease, previous ectopic pregnancy, pelvic adhesions, and tubal surgery with cauterization of the tubes and subsequent bowel adhesions distort the fallopian tubes and may render them unable to propel a migrated embryo into the uterine cavity.2,6 Ectopic pregnancy may result from internal migration of a fertilized ovum or transperitoneal migration of sperm.7

DES exposure can distort the uterine cavity.8 Congenital and acquired uterine malformations increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy.3

In addition, ovulation-inducing drugs and ovarian stimulation increase the number of eggs available for conception, with a greater risk of multiple gestation and heterotopic pregnancy.3,9,10

The greatest increase in heterotopic pregnancy has been seen with ART involving the transfer of multiple embryos into the uterus, as well as gamete intrafallopian transfer, also known as GIFT.10,11 When five or more embryos are transferred, the risk of heterotopic pregnancy increases to 1 in 45 pregnancies annually.11 Inadvertent placement of the catheter tip near the tube, excessive force or volume during transfer, and retrograde migration of an embryo because of uterine contraction may also increase the risk of heterotopic pregnancy.8

A heterotopic pregnancy in spontaneous conceptual cycles without ART is relatively rare, even in a woman who has risk factors for ectopic pregnancy.12

How does heterotopic pregnancy develop?

Possibilities include the following, according to Wolf and colleagues:

- fertilization of two ova from a single coitus

- superimposition of an intrauterine pregnancy over an existing ectopic pregnancy (also known as superfetation).13

The appearance of cardiac activity may be discordant in heterotopic pregnancy, according to Hirsh and associates, suggesting that superfetation is indeed a mechanism in its development, with one pregnancy conceived earlier than the other.14

Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion

The timely detection of heterotopic pregnancy necessitates vigilance.10,15 The TABLE lists signs and symptoms of this condition, which include abdominal pain, an adnexal mass, peritoneal irritation, an enlarged uterus, and absence of vaginal bleeding.6 In contrast to ectopic pregnancy, there is no vaginal bleeding with heterotopic pregnancy because an intact intrauterine pregnancy is present.8

TABLE

Signs and symptoms of heterotopic pregnancy

| Pain after spontaneous or induced abortion |

| Two corpora lutea detected during ultrasonography or laparotomy |

| Persistent Hegar’s sign or Chadwick’s sign after laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy |

| Absence of vaginal bleeding after laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy |

| Lateral location of a gestational sac identified via ultrasonography |

| Fluid in the uterus |

| Discordant appearance of fetal cardiac activity |

| Unpredictable quantitative human chorionic gonadotropin levels |

CASE 2: Ovarian “cyst” turns out to be a gestation

A 28-year-old woman, para 2-0-0-2, visits the emergency department complaining of acute abdominal pain, and is given two diagnoses: urinary tract infection and incomplete abortion at 5 weeks’ gestation. She is treated for the infection and discharged, to be followed up with treatment by her private ObGyn for the incomplete abortion.

Three days later she returns, reporting cramping and increased pain. Ultrasonography reveals intrauterine fetal demise at 8 weeks and 6 days of gestation, along with a hemorrhagic mass in the cul-de-sac—most likely a ruptured hemorrhagic ovarian cyst. Her history includes two cesarean deliveries and treatment with clonidine for hypertension. Her blood pressure is normal, and her abdomen is diffusely tender, with bowel sounds present. The preoperative diagnosis: incomplete abortion and a ruptured hemorrhagic cyst.

During exploratory laparotomy, left salpingo-oophorectomy is performed, and a hemorrhagic ovarian cyst is removed, with evacuation of hemoperitoneum, followed by suction curettage. Almost no tissue is present in the uterine cavity at the time of surgery. The final pathology report determines that the hemorrhagic cyst contained organizing clotted blood with trophoblasts, consistent with ectopic pregnancy. In addition, the uterine contents included scant tissue with hypersecretory endometrium. The physician theorizes that the collapsed gestational sac may have passed out of the patient’s uterus after US or during preoperative preparation.

The patient does well postoperatively and is discharged home.

Should ectopic pregnancy have been suspected earlier?

When a patient experiences pain after spontaneous or induced abortion, ectopic pregnancy should be suspected.2 In addition, women who exhibit signs or symptoms of ectopic pregnancy or continuing pregnancy after an inconclusive or negative US should be assessed thoroughly to exclude ectopic pregnancy.5

Conversely, if symptoms of pregnancy persist or worsen after laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy, the surgeon should suspect another pregnancy.7 Even when a patient who is being treated for infertility exhibits signs and symptoms of ectopic pregnancy, concurrent intrauterine pregnancy must be ruled out.9

A persistent Hegar’s sign or Chadwick’s sign means that a pregnancy is still present.7 In addition, the absence of vaginal bleeding after surgery for ectopic pregnancy may indicate the presence of gestation.6

Few heterotopic pregnancies are identified before surgery

Only 10% of heterotopic pregnancies are detected preoperatively.3 One third of intrauterine gestations in a heterotopic pregnancy spontaneously abort.11

Don’t assume that the presence of an intrauterine gestation excludes the possibility of ectopic pregnancy when the patient experiences abdominal pain.16

Imaging is helpful but not foolproof

Identifying a heterotopic pregnancy before surgery is an imaging challenge. Even when US is employed, the diagnosis is missed in 50% of cases—and even transvaginal US has low sensitivity.17,18 One reason may be the discordant appearance of fetal cardiac activity in coexisting intrauterine and ectopic pregnancies. Alternatively, the gestational sac may be anembryonic.19

A gestational sac is a sonolucent structure with a double decidual sac sign—i.e., an echogenic ring surrounding the sac. A pseudogestational sac containing fluid or blood can mimic a gestational sac.5 One helpful diagnostic sign of heterotopic pregnancy during US examination is a lateral location of one of the gestational sacs.16

If two corpora lutea are present on US—or even at laparotomy or laparoscopy—suspect heterotopic pregnancy.7

Obstetric imaging should include views of the adnexae

The adnexa and surrounding structures are usually not imaged during obstetric US because the focus is on the intrauterine gestation.5 In addition, ultrasonographers are frequently misled by the presence of fluid in the uterus.

It is important for the ultrasonographer to examine the entire pelvic region for pregnancy (FIGURE), especially in women who have been treated with ART or who have pelvic inflammatory disease or a history of pelvic surgery.11 The adnexae should be assessed during every obstetric US, especially in women who are at risk of ectopic pregnancy.5

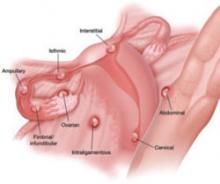

FIGURE When a pregnancy wanders, there are many possibilities for where

Ectopic pregnancy can arise as a result of internal migration of a fertilized ovum or transperitoneal migration of sperm. It may be observed at a number of possible sites within the pelvis.

Serial beta-hCG levels aren’t helpful

In heterotopic pregnancy, both gestations produce hCG, so the assessment of serial serum quantitative beta-hCG levels is not informative.11

When treating ectopic pregnancy, hold off on curettage

Ectopic pregnancy and extrauterine gestation are life-threatening emergencies that require timely diagnosis and treatment.5,19 The traditional treatment for ectopic pregnancy is laparotomy or laparoscopy with removal of the ectopic pregnancy, followed by dilation and curettage (D&C). The curettage removes the decidual cast and clots and is intended to prevent postoperative bleeding. However, curettage could destroy any intrauterine pregnancy that is not yet diagnosed. Therefore, D&C should be withheld until the uterus is confirmed to be empty.10

1. Childs AJ, Royek AB, Leigh TB, Gallup PG. Triplet heterotopic pregnancy after gonadotropin stimulation and intrauterine insemination diagnosed at laparoscopy: a case report. South Med J. 2005;98:833-835.

2. Richards SR, Stempel LE, Carlton BD. Heterotopic pregnancy: reappraisal of incidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;142:928-930.

3. Laband SJ, Cherny WB, Finberg HJ. Heterotopic pregnancy: report of four cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:437-438.

4. Snyder T, delCastillo J, Graff J, Hoxsey R, Hefti M. Heterotopic pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and ovulatory drugs. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:846-849.

5. DeFrancesch F, DiLeo L, Martinez J. Heterotopic pregnancy: discovery of ectopic pregnancy after elective abortion. South Med J. 1999;92:330-332.

6. Rizk B, Tan SL, Morcos S, et al. Heterotopic pregnancies after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164(1 Pt 1):161-164.

7. Rothman A, Shapiro J. Heterotopic pregnancy after homolateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Report of a case. Obstet Gynecol. 1965;26:718-720.

8. Sherer DM, Scibetta JJ, Sanko SR. Heterotopic quadruplet gestation with laparoscopic resection of ruptured interstitial pregnancy and subsequent successful outcome of triplets. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(1 Pt 1):216-217.

9. Payne S, Duge J, Bradbury W. Ectopic pregnancy concomitant with twin intrauterine pregnancy. A case report. Obstet Gynecol. 1971;38:905-906.

10. Gamberdella FR, Marrs RP. Heterotopic pregnancy associated with assisted reproductive technology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:1520-1524.

11. Beyer DA, Dumesic DA. Heterotopic pregnancy: an emerging diagnostic challenge. OBG Management. 2002;14(10):36-46.

12. Somers MP, Spears M, Maynard AS, Syverud SA. Ruptured heterotopic pregnancy presenting with relative bradycardia in a woman not receiving reproductive assistance. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:382-385.

13. Wolf GC, Kritzer L, DeBold C. Heterotopic pregnancy: midtrimester management. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;54:756-758.

14. Hirsch E, Cohen L, Hecht BR. Heterotopic pregnancy with discordant ultrasonic appearance of fetal cardiac activity. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79(5 Pt 2):824-825.

15. McLain PL, Kirkwood CR. Ovarian and intrauterine heterotopic pregnancy following clomiphene ovulation induction: report of a healthy live birth. J Fam Pract. 1987;24:76-79.

16. Luckas MJM, Fishwick K, Martin-Hierro K, Shaw GC, Walkinshaw SA. Survival of intrauterine twins and an interstitial singleton fetus from a heterotopic in vitro fertilisation–embryo transfer pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:751-752.

17. Crabtree KE, Collet B, Kilpatrick SJ. Puerperal presentation of a living abdominal pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84(4 Pt 2):646-648.

18. Cheng PJ, Chueh HY, Qiu JT. Heterotopic pregnancy in a natural conception cycle presenting as hematometra. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(5 Pt 2):1195-1198.

19. Fa EM, Gerscovich EO. High resolution ultrasound in the diagnosis of heterotopic pregnancy: combined transabdominal and transvaginal approach. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:871-872.

20. Smith DJ, Siddique FH. A case of heterotopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970;108:1289-1290.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE 1: Pelvic pain and few signs of intrauterine pregnancy

A 24-year-old woman, para 1-0-0-1, visits the hospital emergency department complaining of pelvic pain. She says the pain arose suddenly and reports that she had a positive urine pregnancy test earlier in the week. When asked about her obstetric history, she reports vaginal delivery of an 8 lb, 8 oz infant at 38 weeks’ gestation 2 years earlier. Her human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level is 3,000 mIU/mL, but ultrasonography (US) reveals no evidence of pregnancy. She is discharged with instructions to follow up with her physician in 2 days.

When her abdominal pain worsens, she returns to the emergency department. Physical examination reveals significant tenderness of the abdomen and moderate to severe tenderness of the cervix upon motion. Transvaginal US shows a uterus of normal size with a 5-mm endometrial lining and no gestational sac. The patient’s abdomen is full of fluid, with large, hypodense areas adjacent to the uterus bilaterally but larger on the right. The preoperative diagnosis: ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

During the diagnostic laparoscopy that follows, approximately 500 mL of blood is discovered in the abdomen and pelvis, and a gestational sac is found to be densely adherent to the right pelvic sidewall, where the ureter nears the uterine vessels. The sac, which has partially separated from the sidewall, is bleeding.

The surgeon peels the sac off the sidewall and controls bleeding with electrocautery and liquid thrombin. The final pathology report describes the tissue as an organizing blood clot with trophoblasts, consistent with ectopic pregnancy.

At a follow-up visit 3 weeks later, the patient reports persistent symptoms of pregnancy. Repeat US reveals a twin intrauterine pregnancy with two sacs, only one of which has a heartbeat. One week later, US shows confluence of the sacs, with a single viable fetus at 8 weeks and 2 days of gestation.

Could heterotopic pregnancy have been diagnosed earlier?

This case illustrates challenges inherent in the diagnosis of heterotopic pregnancy, which is much more common today than it was when it was first described 300 years ago. Incidence has increased from approximately 1 in 30,000 pregnancies to 1 in 2,600 pregnancies annually. When assisted reproductive technologies (ART) are used, the incidence may be as high as 1 in 100 pregnancies.1

The rising incidence suggests that the diagnosis of intrauterine pregnancy can no longer be used to exclude the presence of ectopic pregnancy, and vice versa. Instead, steps must be taken to rule out both when a woman exhibits pain and signs of pregnancy.

In this article, we discuss the causes, diagnosis, and treatment of heterotopic pregnancy, including the necessity of a high index of suspicion, the unreliability of US imaging in 50% of cases, and the need to avoid curettage in the treatment of ectopic pregnancy until an empty uterus can be confirmed.

Duverney was the first to report heterotopic pregnancy, in 1708, after finding an intrauterine pregnancy during the autopsy of a woman who had died from a ruptured ectopic pregnancy.1 It was 165 years, however, before the first review of the phenomenon was written.2 By 1970, only 479 such cases had been reported.20

Determining incidence remains a challenge—except that it is rising

In 1948, DeVoe and Pratt calculated the incidence of heterotopic pregnancy by multiplying the incidence of two-ovum pregnancy by the incidence of ectopic pregnancy, reaching an estimate of 1 in 30,000 pregnancies annually.2

In 1965, Rothman and Shapiro found that only about 500 cases of heterotopic pregnancy had been reported cumulatively.7 They reasoned that, if the incidence of fraternal twins is 1 in 110 and the incidence of ectopic pregnancy is 1 in 250, heterotopic pregnancy should occur at a rate of 1 in 27,500 gestations.7 They also speculated that many heterotopic pregnancies go undiagnosed because of early pregnancy loss.7

In 1971, Payne and colleagues hypothesized that ovulation-induction agents increase the incidence of heterotopic pregnancy, and McLain and associates reached a similar conclusion in 1987.9 The incidence of multiple pregnancy after oral ovulation induction is 8% to 10%, and it is 20% to 50% with injectable agents.9 In 1994, Crabtree and associates reported that both abdominal and heterotopic pregnancies appear to be increasing in incidence.17

Today, the incidence of heterotopic pregnancy is thought to be about 1 in 2,600 pregnancies annually—primarily because of assisted reproduction.2 The calculated risk of heterotopic pregnancy is 1 in 119, and it rises to 1 in 45 with embryo transfer.8

Why is heterotopic pregnancy on the increase?

One reason may be the increase in ectopic pregnancy. Among the factors contributing to the rising incidence of ectopic pregnancy are:

- pelvic adhesive disease

- effects of diethylstilbestrol (DES) on the genital tract

- antibiotic-induced tubal disease

- use of an intrauterine device (IUD)

- voluntary restriction of family size

- iatrogenic curettage of intrauterine pregnancy during surgery for ectopic pregnancy

- pregnancy termination

- history of surgery to treat infertility, ectopic pregnancy, or tubal adhesions

- improvement in the assay used to measure gonadotropin

- improvement in ultrasonography.2-4

A previous ectopic pregnancy is a risk factor for ectopic pregnancy as well as for heterotopic pregnancy.5

Pelvic infection, antibiotic-induced tubal disease, previous ectopic pregnancy, pelvic adhesions, and tubal surgery with cauterization of the tubes and subsequent bowel adhesions distort the fallopian tubes and may render them unable to propel a migrated embryo into the uterine cavity.2,6 Ectopic pregnancy may result from internal migration of a fertilized ovum or transperitoneal migration of sperm.7

DES exposure can distort the uterine cavity.8 Congenital and acquired uterine malformations increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy.3

In addition, ovulation-inducing drugs and ovarian stimulation increase the number of eggs available for conception, with a greater risk of multiple gestation and heterotopic pregnancy.3,9,10

The greatest increase in heterotopic pregnancy has been seen with ART involving the transfer of multiple embryos into the uterus, as well as gamete intrafallopian transfer, also known as GIFT.10,11 When five or more embryos are transferred, the risk of heterotopic pregnancy increases to 1 in 45 pregnancies annually.11 Inadvertent placement of the catheter tip near the tube, excessive force or volume during transfer, and retrograde migration of an embryo because of uterine contraction may also increase the risk of heterotopic pregnancy.8

A heterotopic pregnancy in spontaneous conceptual cycles without ART is relatively rare, even in a woman who has risk factors for ectopic pregnancy.12

How does heterotopic pregnancy develop?

Possibilities include the following, according to Wolf and colleagues:

- fertilization of two ova from a single coitus

- superimposition of an intrauterine pregnancy over an existing ectopic pregnancy (also known as superfetation).13

The appearance of cardiac activity may be discordant in heterotopic pregnancy, according to Hirsh and associates, suggesting that superfetation is indeed a mechanism in its development, with one pregnancy conceived earlier than the other.14

Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion

The timely detection of heterotopic pregnancy necessitates vigilance.10,15 The TABLE lists signs and symptoms of this condition, which include abdominal pain, an adnexal mass, peritoneal irritation, an enlarged uterus, and absence of vaginal bleeding.6 In contrast to ectopic pregnancy, there is no vaginal bleeding with heterotopic pregnancy because an intact intrauterine pregnancy is present.8

TABLE

Signs and symptoms of heterotopic pregnancy

| Pain after spontaneous or induced abortion |

| Two corpora lutea detected during ultrasonography or laparotomy |

| Persistent Hegar’s sign or Chadwick’s sign after laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy |

| Absence of vaginal bleeding after laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy |

| Lateral location of a gestational sac identified via ultrasonography |

| Fluid in the uterus |

| Discordant appearance of fetal cardiac activity |

| Unpredictable quantitative human chorionic gonadotropin levels |

CASE 2: Ovarian “cyst” turns out to be a gestation

A 28-year-old woman, para 2-0-0-2, visits the emergency department complaining of acute abdominal pain, and is given two diagnoses: urinary tract infection and incomplete abortion at 5 weeks’ gestation. She is treated for the infection and discharged, to be followed up with treatment by her private ObGyn for the incomplete abortion.

Three days later she returns, reporting cramping and increased pain. Ultrasonography reveals intrauterine fetal demise at 8 weeks and 6 days of gestation, along with a hemorrhagic mass in the cul-de-sac—most likely a ruptured hemorrhagic ovarian cyst. Her history includes two cesarean deliveries and treatment with clonidine for hypertension. Her blood pressure is normal, and her abdomen is diffusely tender, with bowel sounds present. The preoperative diagnosis: incomplete abortion and a ruptured hemorrhagic cyst.

During exploratory laparotomy, left salpingo-oophorectomy is performed, and a hemorrhagic ovarian cyst is removed, with evacuation of hemoperitoneum, followed by suction curettage. Almost no tissue is present in the uterine cavity at the time of surgery. The final pathology report determines that the hemorrhagic cyst contained organizing clotted blood with trophoblasts, consistent with ectopic pregnancy. In addition, the uterine contents included scant tissue with hypersecretory endometrium. The physician theorizes that the collapsed gestational sac may have passed out of the patient’s uterus after US or during preoperative preparation.

The patient does well postoperatively and is discharged home.

Should ectopic pregnancy have been suspected earlier?

When a patient experiences pain after spontaneous or induced abortion, ectopic pregnancy should be suspected.2 In addition, women who exhibit signs or symptoms of ectopic pregnancy or continuing pregnancy after an inconclusive or negative US should be assessed thoroughly to exclude ectopic pregnancy.5

Conversely, if symptoms of pregnancy persist or worsen after laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy, the surgeon should suspect another pregnancy.7 Even when a patient who is being treated for infertility exhibits signs and symptoms of ectopic pregnancy, concurrent intrauterine pregnancy must be ruled out.9

A persistent Hegar’s sign or Chadwick’s sign means that a pregnancy is still present.7 In addition, the absence of vaginal bleeding after surgery for ectopic pregnancy may indicate the presence of gestation.6

Few heterotopic pregnancies are identified before surgery

Only 10% of heterotopic pregnancies are detected preoperatively.3 One third of intrauterine gestations in a heterotopic pregnancy spontaneously abort.11

Don’t assume that the presence of an intrauterine gestation excludes the possibility of ectopic pregnancy when the patient experiences abdominal pain.16

Imaging is helpful but not foolproof

Identifying a heterotopic pregnancy before surgery is an imaging challenge. Even when US is employed, the diagnosis is missed in 50% of cases—and even transvaginal US has low sensitivity.17,18 One reason may be the discordant appearance of fetal cardiac activity in coexisting intrauterine and ectopic pregnancies. Alternatively, the gestational sac may be anembryonic.19

A gestational sac is a sonolucent structure with a double decidual sac sign—i.e., an echogenic ring surrounding the sac. A pseudogestational sac containing fluid or blood can mimic a gestational sac.5 One helpful diagnostic sign of heterotopic pregnancy during US examination is a lateral location of one of the gestational sacs.16

If two corpora lutea are present on US—or even at laparotomy or laparoscopy—suspect heterotopic pregnancy.7

Obstetric imaging should include views of the adnexae

The adnexa and surrounding structures are usually not imaged during obstetric US because the focus is on the intrauterine gestation.5 In addition, ultrasonographers are frequently misled by the presence of fluid in the uterus.

It is important for the ultrasonographer to examine the entire pelvic region for pregnancy (FIGURE), especially in women who have been treated with ART or who have pelvic inflammatory disease or a history of pelvic surgery.11 The adnexae should be assessed during every obstetric US, especially in women who are at risk of ectopic pregnancy.5

FIGURE When a pregnancy wanders, there are many possibilities for where

Ectopic pregnancy can arise as a result of internal migration of a fertilized ovum or transperitoneal migration of sperm. It may be observed at a number of possible sites within the pelvis.

Serial beta-hCG levels aren’t helpful

In heterotopic pregnancy, both gestations produce hCG, so the assessment of serial serum quantitative beta-hCG levels is not informative.11

When treating ectopic pregnancy, hold off on curettage

Ectopic pregnancy and extrauterine gestation are life-threatening emergencies that require timely diagnosis and treatment.5,19 The traditional treatment for ectopic pregnancy is laparotomy or laparoscopy with removal of the ectopic pregnancy, followed by dilation and curettage (D&C). The curettage removes the decidual cast and clots and is intended to prevent postoperative bleeding. However, curettage could destroy any intrauterine pregnancy that is not yet diagnosed. Therefore, D&C should be withheld until the uterus is confirmed to be empty.10

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE 1: Pelvic pain and few signs of intrauterine pregnancy

A 24-year-old woman, para 1-0-0-1, visits the hospital emergency department complaining of pelvic pain. She says the pain arose suddenly and reports that she had a positive urine pregnancy test earlier in the week. When asked about her obstetric history, she reports vaginal delivery of an 8 lb, 8 oz infant at 38 weeks’ gestation 2 years earlier. Her human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level is 3,000 mIU/mL, but ultrasonography (US) reveals no evidence of pregnancy. She is discharged with instructions to follow up with her physician in 2 days.

When her abdominal pain worsens, she returns to the emergency department. Physical examination reveals significant tenderness of the abdomen and moderate to severe tenderness of the cervix upon motion. Transvaginal US shows a uterus of normal size with a 5-mm endometrial lining and no gestational sac. The patient’s abdomen is full of fluid, with large, hypodense areas adjacent to the uterus bilaterally but larger on the right. The preoperative diagnosis: ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

During the diagnostic laparoscopy that follows, approximately 500 mL of blood is discovered in the abdomen and pelvis, and a gestational sac is found to be densely adherent to the right pelvic sidewall, where the ureter nears the uterine vessels. The sac, which has partially separated from the sidewall, is bleeding.

The surgeon peels the sac off the sidewall and controls bleeding with electrocautery and liquid thrombin. The final pathology report describes the tissue as an organizing blood clot with trophoblasts, consistent with ectopic pregnancy.

At a follow-up visit 3 weeks later, the patient reports persistent symptoms of pregnancy. Repeat US reveals a twin intrauterine pregnancy with two sacs, only one of which has a heartbeat. One week later, US shows confluence of the sacs, with a single viable fetus at 8 weeks and 2 days of gestation.

Could heterotopic pregnancy have been diagnosed earlier?

This case illustrates challenges inherent in the diagnosis of heterotopic pregnancy, which is much more common today than it was when it was first described 300 years ago. Incidence has increased from approximately 1 in 30,000 pregnancies to 1 in 2,600 pregnancies annually. When assisted reproductive technologies (ART) are used, the incidence may be as high as 1 in 100 pregnancies.1

The rising incidence suggests that the diagnosis of intrauterine pregnancy can no longer be used to exclude the presence of ectopic pregnancy, and vice versa. Instead, steps must be taken to rule out both when a woman exhibits pain and signs of pregnancy.

In this article, we discuss the causes, diagnosis, and treatment of heterotopic pregnancy, including the necessity of a high index of suspicion, the unreliability of US imaging in 50% of cases, and the need to avoid curettage in the treatment of ectopic pregnancy until an empty uterus can be confirmed.

Duverney was the first to report heterotopic pregnancy, in 1708, after finding an intrauterine pregnancy during the autopsy of a woman who had died from a ruptured ectopic pregnancy.1 It was 165 years, however, before the first review of the phenomenon was written.2 By 1970, only 479 such cases had been reported.20

Determining incidence remains a challenge—except that it is rising

In 1948, DeVoe and Pratt calculated the incidence of heterotopic pregnancy by multiplying the incidence of two-ovum pregnancy by the incidence of ectopic pregnancy, reaching an estimate of 1 in 30,000 pregnancies annually.2

In 1965, Rothman and Shapiro found that only about 500 cases of heterotopic pregnancy had been reported cumulatively.7 They reasoned that, if the incidence of fraternal twins is 1 in 110 and the incidence of ectopic pregnancy is 1 in 250, heterotopic pregnancy should occur at a rate of 1 in 27,500 gestations.7 They also speculated that many heterotopic pregnancies go undiagnosed because of early pregnancy loss.7

In 1971, Payne and colleagues hypothesized that ovulation-induction agents increase the incidence of heterotopic pregnancy, and McLain and associates reached a similar conclusion in 1987.9 The incidence of multiple pregnancy after oral ovulation induction is 8% to 10%, and it is 20% to 50% with injectable agents.9 In 1994, Crabtree and associates reported that both abdominal and heterotopic pregnancies appear to be increasing in incidence.17

Today, the incidence of heterotopic pregnancy is thought to be about 1 in 2,600 pregnancies annually—primarily because of assisted reproduction.2 The calculated risk of heterotopic pregnancy is 1 in 119, and it rises to 1 in 45 with embryo transfer.8

Why is heterotopic pregnancy on the increase?

One reason may be the increase in ectopic pregnancy. Among the factors contributing to the rising incidence of ectopic pregnancy are:

- pelvic adhesive disease

- effects of diethylstilbestrol (DES) on the genital tract

- antibiotic-induced tubal disease

- use of an intrauterine device (IUD)

- voluntary restriction of family size

- iatrogenic curettage of intrauterine pregnancy during surgery for ectopic pregnancy

- pregnancy termination

- history of surgery to treat infertility, ectopic pregnancy, or tubal adhesions

- improvement in the assay used to measure gonadotropin

- improvement in ultrasonography.2-4

A previous ectopic pregnancy is a risk factor for ectopic pregnancy as well as for heterotopic pregnancy.5

Pelvic infection, antibiotic-induced tubal disease, previous ectopic pregnancy, pelvic adhesions, and tubal surgery with cauterization of the tubes and subsequent bowel adhesions distort the fallopian tubes and may render them unable to propel a migrated embryo into the uterine cavity.2,6 Ectopic pregnancy may result from internal migration of a fertilized ovum or transperitoneal migration of sperm.7

DES exposure can distort the uterine cavity.8 Congenital and acquired uterine malformations increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy.3

In addition, ovulation-inducing drugs and ovarian stimulation increase the number of eggs available for conception, with a greater risk of multiple gestation and heterotopic pregnancy.3,9,10

The greatest increase in heterotopic pregnancy has been seen with ART involving the transfer of multiple embryos into the uterus, as well as gamete intrafallopian transfer, also known as GIFT.10,11 When five or more embryos are transferred, the risk of heterotopic pregnancy increases to 1 in 45 pregnancies annually.11 Inadvertent placement of the catheter tip near the tube, excessive force or volume during transfer, and retrograde migration of an embryo because of uterine contraction may also increase the risk of heterotopic pregnancy.8

A heterotopic pregnancy in spontaneous conceptual cycles without ART is relatively rare, even in a woman who has risk factors for ectopic pregnancy.12

How does heterotopic pregnancy develop?

Possibilities include the following, according to Wolf and colleagues:

- fertilization of two ova from a single coitus

- superimposition of an intrauterine pregnancy over an existing ectopic pregnancy (also known as superfetation).13

The appearance of cardiac activity may be discordant in heterotopic pregnancy, according to Hirsh and associates, suggesting that superfetation is indeed a mechanism in its development, with one pregnancy conceived earlier than the other.14

Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion

The timely detection of heterotopic pregnancy necessitates vigilance.10,15 The TABLE lists signs and symptoms of this condition, which include abdominal pain, an adnexal mass, peritoneal irritation, an enlarged uterus, and absence of vaginal bleeding.6 In contrast to ectopic pregnancy, there is no vaginal bleeding with heterotopic pregnancy because an intact intrauterine pregnancy is present.8

TABLE

Signs and symptoms of heterotopic pregnancy

| Pain after spontaneous or induced abortion |

| Two corpora lutea detected during ultrasonography or laparotomy |

| Persistent Hegar’s sign or Chadwick’s sign after laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy |

| Absence of vaginal bleeding after laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy |

| Lateral location of a gestational sac identified via ultrasonography |

| Fluid in the uterus |

| Discordant appearance of fetal cardiac activity |

| Unpredictable quantitative human chorionic gonadotropin levels |

CASE 2: Ovarian “cyst” turns out to be a gestation

A 28-year-old woman, para 2-0-0-2, visits the emergency department complaining of acute abdominal pain, and is given two diagnoses: urinary tract infection and incomplete abortion at 5 weeks’ gestation. She is treated for the infection and discharged, to be followed up with treatment by her private ObGyn for the incomplete abortion.

Three days later she returns, reporting cramping and increased pain. Ultrasonography reveals intrauterine fetal demise at 8 weeks and 6 days of gestation, along with a hemorrhagic mass in the cul-de-sac—most likely a ruptured hemorrhagic ovarian cyst. Her history includes two cesarean deliveries and treatment with clonidine for hypertension. Her blood pressure is normal, and her abdomen is diffusely tender, with bowel sounds present. The preoperative diagnosis: incomplete abortion and a ruptured hemorrhagic cyst.

During exploratory laparotomy, left salpingo-oophorectomy is performed, and a hemorrhagic ovarian cyst is removed, with evacuation of hemoperitoneum, followed by suction curettage. Almost no tissue is present in the uterine cavity at the time of surgery. The final pathology report determines that the hemorrhagic cyst contained organizing clotted blood with trophoblasts, consistent with ectopic pregnancy. In addition, the uterine contents included scant tissue with hypersecretory endometrium. The physician theorizes that the collapsed gestational sac may have passed out of the patient’s uterus after US or during preoperative preparation.

The patient does well postoperatively and is discharged home.

Should ectopic pregnancy have been suspected earlier?

When a patient experiences pain after spontaneous or induced abortion, ectopic pregnancy should be suspected.2 In addition, women who exhibit signs or symptoms of ectopic pregnancy or continuing pregnancy after an inconclusive or negative US should be assessed thoroughly to exclude ectopic pregnancy.5

Conversely, if symptoms of pregnancy persist or worsen after laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy, the surgeon should suspect another pregnancy.7 Even when a patient who is being treated for infertility exhibits signs and symptoms of ectopic pregnancy, concurrent intrauterine pregnancy must be ruled out.9

A persistent Hegar’s sign or Chadwick’s sign means that a pregnancy is still present.7 In addition, the absence of vaginal bleeding after surgery for ectopic pregnancy may indicate the presence of gestation.6

Few heterotopic pregnancies are identified before surgery

Only 10% of heterotopic pregnancies are detected preoperatively.3 One third of intrauterine gestations in a heterotopic pregnancy spontaneously abort.11

Don’t assume that the presence of an intrauterine gestation excludes the possibility of ectopic pregnancy when the patient experiences abdominal pain.16

Imaging is helpful but not foolproof

Identifying a heterotopic pregnancy before surgery is an imaging challenge. Even when US is employed, the diagnosis is missed in 50% of cases—and even transvaginal US has low sensitivity.17,18 One reason may be the discordant appearance of fetal cardiac activity in coexisting intrauterine and ectopic pregnancies. Alternatively, the gestational sac may be anembryonic.19

A gestational sac is a sonolucent structure with a double decidual sac sign—i.e., an echogenic ring surrounding the sac. A pseudogestational sac containing fluid or blood can mimic a gestational sac.5 One helpful diagnostic sign of heterotopic pregnancy during US examination is a lateral location of one of the gestational sacs.16

If two corpora lutea are present on US—or even at laparotomy or laparoscopy—suspect heterotopic pregnancy.7

Obstetric imaging should include views of the adnexae

The adnexa and surrounding structures are usually not imaged during obstetric US because the focus is on the intrauterine gestation.5 In addition, ultrasonographers are frequently misled by the presence of fluid in the uterus.

It is important for the ultrasonographer to examine the entire pelvic region for pregnancy (FIGURE), especially in women who have been treated with ART or who have pelvic inflammatory disease or a history of pelvic surgery.11 The adnexae should be assessed during every obstetric US, especially in women who are at risk of ectopic pregnancy.5

FIGURE When a pregnancy wanders, there are many possibilities for where

Ectopic pregnancy can arise as a result of internal migration of a fertilized ovum or transperitoneal migration of sperm. It may be observed at a number of possible sites within the pelvis.

Serial beta-hCG levels aren’t helpful

In heterotopic pregnancy, both gestations produce hCG, so the assessment of serial serum quantitative beta-hCG levels is not informative.11

When treating ectopic pregnancy, hold off on curettage

Ectopic pregnancy and extrauterine gestation are life-threatening emergencies that require timely diagnosis and treatment.5,19 The traditional treatment for ectopic pregnancy is laparotomy or laparoscopy with removal of the ectopic pregnancy, followed by dilation and curettage (D&C). The curettage removes the decidual cast and clots and is intended to prevent postoperative bleeding. However, curettage could destroy any intrauterine pregnancy that is not yet diagnosed. Therefore, D&C should be withheld until the uterus is confirmed to be empty.10

1. Childs AJ, Royek AB, Leigh TB, Gallup PG. Triplet heterotopic pregnancy after gonadotropin stimulation and intrauterine insemination diagnosed at laparoscopy: a case report. South Med J. 2005;98:833-835.

2. Richards SR, Stempel LE, Carlton BD. Heterotopic pregnancy: reappraisal of incidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;142:928-930.

3. Laband SJ, Cherny WB, Finberg HJ. Heterotopic pregnancy: report of four cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:437-438.

4. Snyder T, delCastillo J, Graff J, Hoxsey R, Hefti M. Heterotopic pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and ovulatory drugs. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:846-849.

5. DeFrancesch F, DiLeo L, Martinez J. Heterotopic pregnancy: discovery of ectopic pregnancy after elective abortion. South Med J. 1999;92:330-332.

6. Rizk B, Tan SL, Morcos S, et al. Heterotopic pregnancies after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164(1 Pt 1):161-164.

7. Rothman A, Shapiro J. Heterotopic pregnancy after homolateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Report of a case. Obstet Gynecol. 1965;26:718-720.

8. Sherer DM, Scibetta JJ, Sanko SR. Heterotopic quadruplet gestation with laparoscopic resection of ruptured interstitial pregnancy and subsequent successful outcome of triplets. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(1 Pt 1):216-217.

9. Payne S, Duge J, Bradbury W. Ectopic pregnancy concomitant with twin intrauterine pregnancy. A case report. Obstet Gynecol. 1971;38:905-906.

10. Gamberdella FR, Marrs RP. Heterotopic pregnancy associated with assisted reproductive technology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:1520-1524.

11. Beyer DA, Dumesic DA. Heterotopic pregnancy: an emerging diagnostic challenge. OBG Management. 2002;14(10):36-46.

12. Somers MP, Spears M, Maynard AS, Syverud SA. Ruptured heterotopic pregnancy presenting with relative bradycardia in a woman not receiving reproductive assistance. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:382-385.

13. Wolf GC, Kritzer L, DeBold C. Heterotopic pregnancy: midtrimester management. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;54:756-758.

14. Hirsch E, Cohen L, Hecht BR. Heterotopic pregnancy with discordant ultrasonic appearance of fetal cardiac activity. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79(5 Pt 2):824-825.

15. McLain PL, Kirkwood CR. Ovarian and intrauterine heterotopic pregnancy following clomiphene ovulation induction: report of a healthy live birth. J Fam Pract. 1987;24:76-79.

16. Luckas MJM, Fishwick K, Martin-Hierro K, Shaw GC, Walkinshaw SA. Survival of intrauterine twins and an interstitial singleton fetus from a heterotopic in vitro fertilisation–embryo transfer pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:751-752.

17. Crabtree KE, Collet B, Kilpatrick SJ. Puerperal presentation of a living abdominal pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84(4 Pt 2):646-648.

18. Cheng PJ, Chueh HY, Qiu JT. Heterotopic pregnancy in a natural conception cycle presenting as hematometra. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(5 Pt 2):1195-1198.

19. Fa EM, Gerscovich EO. High resolution ultrasound in the diagnosis of heterotopic pregnancy: combined transabdominal and transvaginal approach. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:871-872.

20. Smith DJ, Siddique FH. A case of heterotopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970;108:1289-1290.

1. Childs AJ, Royek AB, Leigh TB, Gallup PG. Triplet heterotopic pregnancy after gonadotropin stimulation and intrauterine insemination diagnosed at laparoscopy: a case report. South Med J. 2005;98:833-835.

2. Richards SR, Stempel LE, Carlton BD. Heterotopic pregnancy: reappraisal of incidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;142:928-930.

3. Laband SJ, Cherny WB, Finberg HJ. Heterotopic pregnancy: report of four cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:437-438.

4. Snyder T, delCastillo J, Graff J, Hoxsey R, Hefti M. Heterotopic pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and ovulatory drugs. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:846-849.

5. DeFrancesch F, DiLeo L, Martinez J. Heterotopic pregnancy: discovery of ectopic pregnancy after elective abortion. South Med J. 1999;92:330-332.

6. Rizk B, Tan SL, Morcos S, et al. Heterotopic pregnancies after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164(1 Pt 1):161-164.

7. Rothman A, Shapiro J. Heterotopic pregnancy after homolateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Report of a case. Obstet Gynecol. 1965;26:718-720.

8. Sherer DM, Scibetta JJ, Sanko SR. Heterotopic quadruplet gestation with laparoscopic resection of ruptured interstitial pregnancy and subsequent successful outcome of triplets. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(1 Pt 1):216-217.

9. Payne S, Duge J, Bradbury W. Ectopic pregnancy concomitant with twin intrauterine pregnancy. A case report. Obstet Gynecol. 1971;38:905-906.

10. Gamberdella FR, Marrs RP. Heterotopic pregnancy associated with assisted reproductive technology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:1520-1524.

11. Beyer DA, Dumesic DA. Heterotopic pregnancy: an emerging diagnostic challenge. OBG Management. 2002;14(10):36-46.

12. Somers MP, Spears M, Maynard AS, Syverud SA. Ruptured heterotopic pregnancy presenting with relative bradycardia in a woman not receiving reproductive assistance. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:382-385.

13. Wolf GC, Kritzer L, DeBold C. Heterotopic pregnancy: midtrimester management. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;54:756-758.

14. Hirsch E, Cohen L, Hecht BR. Heterotopic pregnancy with discordant ultrasonic appearance of fetal cardiac activity. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79(5 Pt 2):824-825.

15. McLain PL, Kirkwood CR. Ovarian and intrauterine heterotopic pregnancy following clomiphene ovulation induction: report of a healthy live birth. J Fam Pract. 1987;24:76-79.

16. Luckas MJM, Fishwick K, Martin-Hierro K, Shaw GC, Walkinshaw SA. Survival of intrauterine twins and an interstitial singleton fetus from a heterotopic in vitro fertilisation–embryo transfer pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:751-752.

17. Crabtree KE, Collet B, Kilpatrick SJ. Puerperal presentation of a living abdominal pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84(4 Pt 2):646-648.

18. Cheng PJ, Chueh HY, Qiu JT. Heterotopic pregnancy in a natural conception cycle presenting as hematometra. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(5 Pt 2):1195-1198.

19. Fa EM, Gerscovich EO. High resolution ultrasound in the diagnosis of heterotopic pregnancy: combined transabdominal and transvaginal approach. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:871-872.

20. Smith DJ, Siddique FH. A case of heterotopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970;108:1289-1290.