User login

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, is a hospitalist and the chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston. She is former SHM physician advisor, an SHM blogger, and member of SHM's Education Committee. She also serves as faculty of SHM's annual meeting "ABIM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Learning Session" pre-course. Dr. Scheurer earned her undergraduate degree at Emory University in Atlanta, graduated medical school from the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, and trained at Duke University in Durham, N.C. She has served as physician editor of The Hospitalist since 2012.

Why Hospitalists Should Focus on Patient-Care Basics

We all are too familiar with the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, a standardized set of questions randomly deployed to recently discharged patients. More recently, hospitalists have noticed the introduction of the Clinician and Groups Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CG-CAHPS) survey, randomly deployed to recently evaluated ambulatory patients. HCAHPS has been publicly reported since 2008. CG-CAHPS will be in the near future. In addition to these, there are a variety of other types of CAHPS surveys, ranging from ambulatory surgery to patient-centered medical homes. For HCAHPS alone, there are more than 8,200 adult surveys completed every day from almost 4,000 different U.S. hospitals.1

In addition to these surveys being publicly reported and widely viewed online by patients, payors, and employers, the results now are tightly coupled to the reimbursement of hospitals and, in some cases, individual providers. As of October 2012, Medicare has relegated 30% of its hospital value-based purchasing (VBP) program to the results of hospitals’ HCAPHS survey results. For the foreseeable future, about one-third of the financial bonus—or penalty—of a hospital rests in the hands of how well our patients perceive their care. Many individual hospitals and practice groups have started coupling individual physicians’ compensation to their patients’ CAHPS scores. Within the (approximately) seven minutes it takes to complete the survey, our patients determine millions of dollars of physician and hospital reimbursement.1

With all of the financial and reputational emphasis on HCAHPS, it is vital that hospitalists understand what it is these surveys are actually measuring, and if they have any correlation with the quality of the care the patient receives. The questions currently address 11 different domains of hospital care:

- Communication with doctors;

- Communication with nurses;

- Responsiveness of hospital staff;

- Pain management;

- Communication about medicines;

- Discharge information;

- Cleanliness of hospital environment;

- Quietness of hospital environment;

- Transitions of care;

- Overall rating of the hospital; and

- Willingness to recommend the hospital.

As the domains of care are all very different, one can imagine a wide range of answers to the various questions; a patient can perceive that communication was excellent but the quietness and cleanliness was disgraceful. And, depending on what they consider the most important aspects of their stay, they therefore may rate their overall stay as excellent or disgraceful. Why? Because each of these rest in the eye of the beholder.

But to keep pace, hospitals and providers across the country have invested millions of hours dissecting the meaning of the results and trying to improve upon them. My hospital has struggled for years with the “cleanliness” question, trying to figure out what our patients are trying to tell us: that we need to sweep and mop more often, that hospital supplies are cluttering our patient rooms, that the trashcans are overflowing or within eyesight? When we ask focus groups, we often get all of the above—and then try to implement several solutions all at once.

The quietness question is much easier to interpret but certainly difficult to improve upon. We have implemented “yacker trackers,” “quiet time,” and soft-wheeled trash cans. And the results of the surveys take months to come back and get analyzed, so it is difficult to quickly know if your interventions are actually working. Given that so many hospitals and providers are back-flipping to “play to the test,” we really need some validation that care is truly improving based on this patient feedback.

A recent New York Times article calls to light a natural paradox in the medical field, in that patients who understand more about disease processes and medical information actually feel less, rather than more, informed. In other words, those who are actually the most well-informed may rate communication the lowest. The article also calls to light the natural paradox between providers being honest and providers being likable, especially considering they routinely have to deliver messages that patients do not want to hear:

- You need to quit smoking;

- Your weight is affecting your health; and

- Your disease is not curable.

Given these natural paradoxes, the article argues that it is difficult to reconcile why hospitals and providers should be held financially accountable for their patients’ perception of care, when that perception may not equate to “real” care quality.2

However, there is some evidence that patient satisfaction surveys may actually be good proxies for care quality. A large study found that hospitals with the highest quartile HCAHPS ratings also have about 2%-3% higher quality scores for acute MI, CHF, pneumonia, and surgery, compared to those in the lowest quartile. The highest scoring hospitals also have about 2%-3% lower readmission rates for acute MI, CHF, and pneumonia.3,4 And, similar to other quality metrics, there is evidence that the longer a hospital has been administering HCAHPS, the better are their scores. So maybe hospital systems and providers can improve not only the perception a patient has of the quality of the care they received, but improve the quality, as measured by the patient’s perception.

Although there are legitimate arguments on both sides as to whether a patient’s perception of care reflects “real” care quality, in the end these CAHPS surveys are, and have been publicly reported, and will be tightly coupled to reimbursement for hospitals and (likely) providers for the foreseeable future. So in the meantime, we should continue to focus on patient-centered care, take seriously any voiced concerns, and have a relentless pursuit of perfection for how patients perceive their care. Because in the end, you would do it for your family so we should do it for our patients.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Spring 2013 HCAHPS Executive Insight Letter. Available at: www.hcahpsonline.org/Executive_Insight. Accessed Aug. 15, 2013.

- Rosenbaum L. When doctors tell patients what they don’t want to hear. The New Yorker website. Available at: www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/elements/2013/07/when-doctors-tell-patients-what-they-dont-want-to-hear.html. Published July 23, 2013. Accessed Aug. 15, 2013.

- Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients' perception of hospital care in the US. New Eng J Med. 2008;359(18):1921-1931.

- Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):41-48.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

We all are too familiar with the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, a standardized set of questions randomly deployed to recently discharged patients. More recently, hospitalists have noticed the introduction of the Clinician and Groups Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CG-CAHPS) survey, randomly deployed to recently evaluated ambulatory patients. HCAHPS has been publicly reported since 2008. CG-CAHPS will be in the near future. In addition to these, there are a variety of other types of CAHPS surveys, ranging from ambulatory surgery to patient-centered medical homes. For HCAHPS alone, there are more than 8,200 adult surveys completed every day from almost 4,000 different U.S. hospitals.1

In addition to these surveys being publicly reported and widely viewed online by patients, payors, and employers, the results now are tightly coupled to the reimbursement of hospitals and, in some cases, individual providers. As of October 2012, Medicare has relegated 30% of its hospital value-based purchasing (VBP) program to the results of hospitals’ HCAPHS survey results. For the foreseeable future, about one-third of the financial bonus—or penalty—of a hospital rests in the hands of how well our patients perceive their care. Many individual hospitals and practice groups have started coupling individual physicians’ compensation to their patients’ CAHPS scores. Within the (approximately) seven minutes it takes to complete the survey, our patients determine millions of dollars of physician and hospital reimbursement.1

With all of the financial and reputational emphasis on HCAHPS, it is vital that hospitalists understand what it is these surveys are actually measuring, and if they have any correlation with the quality of the care the patient receives. The questions currently address 11 different domains of hospital care:

- Communication with doctors;

- Communication with nurses;

- Responsiveness of hospital staff;

- Pain management;

- Communication about medicines;

- Discharge information;

- Cleanliness of hospital environment;

- Quietness of hospital environment;

- Transitions of care;

- Overall rating of the hospital; and

- Willingness to recommend the hospital.

As the domains of care are all very different, one can imagine a wide range of answers to the various questions; a patient can perceive that communication was excellent but the quietness and cleanliness was disgraceful. And, depending on what they consider the most important aspects of their stay, they therefore may rate their overall stay as excellent or disgraceful. Why? Because each of these rest in the eye of the beholder.

But to keep pace, hospitals and providers across the country have invested millions of hours dissecting the meaning of the results and trying to improve upon them. My hospital has struggled for years with the “cleanliness” question, trying to figure out what our patients are trying to tell us: that we need to sweep and mop more often, that hospital supplies are cluttering our patient rooms, that the trashcans are overflowing or within eyesight? When we ask focus groups, we often get all of the above—and then try to implement several solutions all at once.

The quietness question is much easier to interpret but certainly difficult to improve upon. We have implemented “yacker trackers,” “quiet time,” and soft-wheeled trash cans. And the results of the surveys take months to come back and get analyzed, so it is difficult to quickly know if your interventions are actually working. Given that so many hospitals and providers are back-flipping to “play to the test,” we really need some validation that care is truly improving based on this patient feedback.

A recent New York Times article calls to light a natural paradox in the medical field, in that patients who understand more about disease processes and medical information actually feel less, rather than more, informed. In other words, those who are actually the most well-informed may rate communication the lowest. The article also calls to light the natural paradox between providers being honest and providers being likable, especially considering they routinely have to deliver messages that patients do not want to hear:

- You need to quit smoking;

- Your weight is affecting your health; and

- Your disease is not curable.

Given these natural paradoxes, the article argues that it is difficult to reconcile why hospitals and providers should be held financially accountable for their patients’ perception of care, when that perception may not equate to “real” care quality.2

However, there is some evidence that patient satisfaction surveys may actually be good proxies for care quality. A large study found that hospitals with the highest quartile HCAHPS ratings also have about 2%-3% higher quality scores for acute MI, CHF, pneumonia, and surgery, compared to those in the lowest quartile. The highest scoring hospitals also have about 2%-3% lower readmission rates for acute MI, CHF, and pneumonia.3,4 And, similar to other quality metrics, there is evidence that the longer a hospital has been administering HCAHPS, the better are their scores. So maybe hospital systems and providers can improve not only the perception a patient has of the quality of the care they received, but improve the quality, as measured by the patient’s perception.

Although there are legitimate arguments on both sides as to whether a patient’s perception of care reflects “real” care quality, in the end these CAHPS surveys are, and have been publicly reported, and will be tightly coupled to reimbursement for hospitals and (likely) providers for the foreseeable future. So in the meantime, we should continue to focus on patient-centered care, take seriously any voiced concerns, and have a relentless pursuit of perfection for how patients perceive their care. Because in the end, you would do it for your family so we should do it for our patients.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Spring 2013 HCAHPS Executive Insight Letter. Available at: www.hcahpsonline.org/Executive_Insight. Accessed Aug. 15, 2013.

- Rosenbaum L. When doctors tell patients what they don’t want to hear. The New Yorker website. Available at: www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/elements/2013/07/when-doctors-tell-patients-what-they-dont-want-to-hear.html. Published July 23, 2013. Accessed Aug. 15, 2013.

- Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients' perception of hospital care in the US. New Eng J Med. 2008;359(18):1921-1931.

- Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):41-48.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

We all are too familiar with the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, a standardized set of questions randomly deployed to recently discharged patients. More recently, hospitalists have noticed the introduction of the Clinician and Groups Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CG-CAHPS) survey, randomly deployed to recently evaluated ambulatory patients. HCAHPS has been publicly reported since 2008. CG-CAHPS will be in the near future. In addition to these, there are a variety of other types of CAHPS surveys, ranging from ambulatory surgery to patient-centered medical homes. For HCAHPS alone, there are more than 8,200 adult surveys completed every day from almost 4,000 different U.S. hospitals.1

In addition to these surveys being publicly reported and widely viewed online by patients, payors, and employers, the results now are tightly coupled to the reimbursement of hospitals and, in some cases, individual providers. As of October 2012, Medicare has relegated 30% of its hospital value-based purchasing (VBP) program to the results of hospitals’ HCAPHS survey results. For the foreseeable future, about one-third of the financial bonus—or penalty—of a hospital rests in the hands of how well our patients perceive their care. Many individual hospitals and practice groups have started coupling individual physicians’ compensation to their patients’ CAHPS scores. Within the (approximately) seven minutes it takes to complete the survey, our patients determine millions of dollars of physician and hospital reimbursement.1

With all of the financial and reputational emphasis on HCAHPS, it is vital that hospitalists understand what it is these surveys are actually measuring, and if they have any correlation with the quality of the care the patient receives. The questions currently address 11 different domains of hospital care:

- Communication with doctors;

- Communication with nurses;

- Responsiveness of hospital staff;

- Pain management;

- Communication about medicines;

- Discharge information;

- Cleanliness of hospital environment;

- Quietness of hospital environment;

- Transitions of care;

- Overall rating of the hospital; and

- Willingness to recommend the hospital.

As the domains of care are all very different, one can imagine a wide range of answers to the various questions; a patient can perceive that communication was excellent but the quietness and cleanliness was disgraceful. And, depending on what they consider the most important aspects of their stay, they therefore may rate their overall stay as excellent or disgraceful. Why? Because each of these rest in the eye of the beholder.

But to keep pace, hospitals and providers across the country have invested millions of hours dissecting the meaning of the results and trying to improve upon them. My hospital has struggled for years with the “cleanliness” question, trying to figure out what our patients are trying to tell us: that we need to sweep and mop more often, that hospital supplies are cluttering our patient rooms, that the trashcans are overflowing or within eyesight? When we ask focus groups, we often get all of the above—and then try to implement several solutions all at once.

The quietness question is much easier to interpret but certainly difficult to improve upon. We have implemented “yacker trackers,” “quiet time,” and soft-wheeled trash cans. And the results of the surveys take months to come back and get analyzed, so it is difficult to quickly know if your interventions are actually working. Given that so many hospitals and providers are back-flipping to “play to the test,” we really need some validation that care is truly improving based on this patient feedback.

A recent New York Times article calls to light a natural paradox in the medical field, in that patients who understand more about disease processes and medical information actually feel less, rather than more, informed. In other words, those who are actually the most well-informed may rate communication the lowest. The article also calls to light the natural paradox between providers being honest and providers being likable, especially considering they routinely have to deliver messages that patients do not want to hear:

- You need to quit smoking;

- Your weight is affecting your health; and

- Your disease is not curable.

Given these natural paradoxes, the article argues that it is difficult to reconcile why hospitals and providers should be held financially accountable for their patients’ perception of care, when that perception may not equate to “real” care quality.2

However, there is some evidence that patient satisfaction surveys may actually be good proxies for care quality. A large study found that hospitals with the highest quartile HCAHPS ratings also have about 2%-3% higher quality scores for acute MI, CHF, pneumonia, and surgery, compared to those in the lowest quartile. The highest scoring hospitals also have about 2%-3% lower readmission rates for acute MI, CHF, and pneumonia.3,4 And, similar to other quality metrics, there is evidence that the longer a hospital has been administering HCAHPS, the better are their scores. So maybe hospital systems and providers can improve not only the perception a patient has of the quality of the care they received, but improve the quality, as measured by the patient’s perception.

Although there are legitimate arguments on both sides as to whether a patient’s perception of care reflects “real” care quality, in the end these CAHPS surveys are, and have been publicly reported, and will be tightly coupled to reimbursement for hospitals and (likely) providers for the foreseeable future. So in the meantime, we should continue to focus on patient-centered care, take seriously any voiced concerns, and have a relentless pursuit of perfection for how patients perceive their care. Because in the end, you would do it for your family so we should do it for our patients.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Spring 2013 HCAHPS Executive Insight Letter. Available at: www.hcahpsonline.org/Executive_Insight. Accessed Aug. 15, 2013.

- Rosenbaum L. When doctors tell patients what they don’t want to hear. The New Yorker website. Available at: www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/elements/2013/07/when-doctors-tell-patients-what-they-dont-want-to-hear.html. Published July 23, 2013. Accessed Aug. 15, 2013.

- Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients' perception of hospital care in the US. New Eng J Med. 2008;359(18):1921-1931.

- Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):41-48.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

Proactive Approaches Necessary to Offset Primary-Care Physician Shortage

As I was reading my departmental, end-of-the-academic-year newsletter, I was pondering my own group’s hospitalist pipeline. Each year, I earnestly read the list of internal-medicine-program graduates, focusing on what and where they are going to practice. I first selfishly scan the list for “hospital medicine, MUSC.” Then I go back and reread the list to see who I can now send my discharges to or who I can refer any new friends or relatives who move to town, scanning the list for “primary care, MUSC.”

This year, similar to recent years, the list for “primary care” is slim.

SHM has long been motivated to think about the pipeline, about how to get the best and the brightest interested in practicing HM, and practicing primary care, as they are vital partners in the spectrum of generalist care. We need to know and understand our pipeline: Where will they train, how will they be trained, will they be prepared to function and thrive in the medical industry of tomorrow? Regardless of how or where you practice, all of us should be thinking about our pipeline.

As such, all of us should be thinking about graduate medical education (GME), how it is funded, how much it is funded, and what regulations control the types of specialties that come out of U.S. training programs.1 This is especially true given the projected need for more hospitalists in all areas of the hospital of the future, the ever-expanding role of “specialty hospitalists,” and the need for hospitalists during the “peri-hospital” stay (from pre-operative clinics to post-discharge clinics). And this is especially true given the ongoing projected expanse of the primary-care shortage.

The career path for physicians starts long before medical school and is heavily shaped by what types of physicians they are exposed to, when they are exposed to them, and what their experience was. The periods of medical school and graduate medical education training can have a profound impact on the “health” of the U.S. health-care system and whether it is equipped to care for the needs of its citizens.

American taxpayers have long been in the business of funding the physician pipeline. The federal government invests $13 billion annually on graduate medical education subsidies. The money flows directly to teaching hospitals to pay for the salaries of the trainees and the salaries of the attendings who supervise their work, as well as the hospital overhead that has to be invested to house these trainees during their tenure.

Federal subsidies for apprenticeships are relatively unheard of in other industries; this funding stream was initiated with the passage of Medicare almost 50 years ago, under the provision that additional training for medical students would result in better and safer medical care for all Americans. However, what was not set up as a tagline to these federal subsidies was any type of accountability on process or outcome measures, such as how exactly do teaching hospitals invest their GME money, and how will they produce the types and amounts of physicians that the U.S. needs?

Cold, Hard Facts

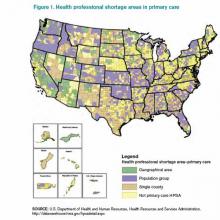

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources, Health Resources and Services Administration, http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/hpsadetail.aspx

So what do Americans get for that annual $13 billion investment? We get what we should expect out of the “free will” of graduating residents: We get an oversupply of specialists in areas of abundance and an undersupply of generalists in most areas. The system “produces” the most appealing specialties (those handsomely reimbursed and highly prestigious), leaving a dwindling number of generalists to be spread thinly. And the most prestigious and top-ranked academic medical centers are the least likely to produce generalists. In many of these highly ranked training programs, less than 10% of their graduates go on to work in primary care, and even fewer work in rural or public health facilities. More than 20% of all residency programs produce no primary-care physicians (PCPs) at all. Despite the $13 billion annual investment, the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) predicts a shortage of 45,000 primary-care physicians by 2020.2

Because of this shortage, even fully insured Americans find the act of securing a generalist to be problematic: Almost 1 in 5 of us live in a federally designated primary-care-shortage area (see Figure 1).3 It is estimated that our current training programs will produce 40% fewer PCPs than will be needed to keep pace with the baby boomers and the insurance expansion of the Affordable Care Act. Attempts at using GME subsidies as a lever to increase the number of generalists have failed for decades. Almost 30 years ago, Dan Quayle petitioned Medicare to forgo any subsidies to training programs that did not commit to graduating at least 70% of trainees to primary-care careers, to no avail. Years later, the Institute of Medicine appealed to the federal government to reduce the training of specialists, and increase the training pool for generalists, to no avail. To reduce the financial burden of GME training, about 15 years ago, Congress threw in place a stop-gap measure, putting a freeze on the total number of residency slots that would be funded, but it did not put any measures in place to ensure that the allocation of slots would match what the U.S. health-care system needs. This has left us in a global shortage of physicians, the most grotesque of which is among generalists in regions of greatest need.

The Good News

So where does this leave hospitalists? Fortunately for our specialty, hospital medicine remains very appealing to new graduates and to the health-care system. For new graduates, it offers a competitive salary and work-life balance, without additional fellowship training. For the health-care system, we are generalists who can enhance the “value equation,” having proven to enhance quality while simultaneously reducing cost. As generalists, our specialty remains relatively undifferentiated and flexible to meet the needs of the system, including caring for patients at many stages of an acute or chronic illness; pre-operative care; post-discharge transitions of care; and assisting in some stages of “specialty care” (e.g. the medical care of the neurologic emergency, the pregnant patient, comanagement with a variety of surgical subspecialists).

As a progressive specialty, we should continue to focus on the pipeline, not only to ensure we recruit our “favorite picks” to hospital medicine, but also to support the reform needed to enhance the appeal of generalist practices and reduce the irresistible appeal of specialty care. In this way, we can add yet another meaningful contribution to meeting the needs of the U.S. health-care system.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

- Longman P. First teach no harm. The Washington Monthly website. Available at: http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/july_august_2013/features/first_teach_no_harm045361.php?page=all. Accessed Aug. 4, 2013.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician shortages to worsen without increases in residency training. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/150612/data/md-shortage.pdf. Accessed Aug. 4, 2013.

As I was reading my departmental, end-of-the-academic-year newsletter, I was pondering my own group’s hospitalist pipeline. Each year, I earnestly read the list of internal-medicine-program graduates, focusing on what and where they are going to practice. I first selfishly scan the list for “hospital medicine, MUSC.” Then I go back and reread the list to see who I can now send my discharges to or who I can refer any new friends or relatives who move to town, scanning the list for “primary care, MUSC.”

This year, similar to recent years, the list for “primary care” is slim.

SHM has long been motivated to think about the pipeline, about how to get the best and the brightest interested in practicing HM, and practicing primary care, as they are vital partners in the spectrum of generalist care. We need to know and understand our pipeline: Where will they train, how will they be trained, will they be prepared to function and thrive in the medical industry of tomorrow? Regardless of how or where you practice, all of us should be thinking about our pipeline.

As such, all of us should be thinking about graduate medical education (GME), how it is funded, how much it is funded, and what regulations control the types of specialties that come out of U.S. training programs.1 This is especially true given the projected need for more hospitalists in all areas of the hospital of the future, the ever-expanding role of “specialty hospitalists,” and the need for hospitalists during the “peri-hospital” stay (from pre-operative clinics to post-discharge clinics). And this is especially true given the ongoing projected expanse of the primary-care shortage.

The career path for physicians starts long before medical school and is heavily shaped by what types of physicians they are exposed to, when they are exposed to them, and what their experience was. The periods of medical school and graduate medical education training can have a profound impact on the “health” of the U.S. health-care system and whether it is equipped to care for the needs of its citizens.

American taxpayers have long been in the business of funding the physician pipeline. The federal government invests $13 billion annually on graduate medical education subsidies. The money flows directly to teaching hospitals to pay for the salaries of the trainees and the salaries of the attendings who supervise their work, as well as the hospital overhead that has to be invested to house these trainees during their tenure.

Federal subsidies for apprenticeships are relatively unheard of in other industries; this funding stream was initiated with the passage of Medicare almost 50 years ago, under the provision that additional training for medical students would result in better and safer medical care for all Americans. However, what was not set up as a tagline to these federal subsidies was any type of accountability on process or outcome measures, such as how exactly do teaching hospitals invest their GME money, and how will they produce the types and amounts of physicians that the U.S. needs?

Cold, Hard Facts

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources, Health Resources and Services Administration, http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/hpsadetail.aspx

So what do Americans get for that annual $13 billion investment? We get what we should expect out of the “free will” of graduating residents: We get an oversupply of specialists in areas of abundance and an undersupply of generalists in most areas. The system “produces” the most appealing specialties (those handsomely reimbursed and highly prestigious), leaving a dwindling number of generalists to be spread thinly. And the most prestigious and top-ranked academic medical centers are the least likely to produce generalists. In many of these highly ranked training programs, less than 10% of their graduates go on to work in primary care, and even fewer work in rural or public health facilities. More than 20% of all residency programs produce no primary-care physicians (PCPs) at all. Despite the $13 billion annual investment, the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) predicts a shortage of 45,000 primary-care physicians by 2020.2

Because of this shortage, even fully insured Americans find the act of securing a generalist to be problematic: Almost 1 in 5 of us live in a federally designated primary-care-shortage area (see Figure 1).3 It is estimated that our current training programs will produce 40% fewer PCPs than will be needed to keep pace with the baby boomers and the insurance expansion of the Affordable Care Act. Attempts at using GME subsidies as a lever to increase the number of generalists have failed for decades. Almost 30 years ago, Dan Quayle petitioned Medicare to forgo any subsidies to training programs that did not commit to graduating at least 70% of trainees to primary-care careers, to no avail. Years later, the Institute of Medicine appealed to the federal government to reduce the training of specialists, and increase the training pool for generalists, to no avail. To reduce the financial burden of GME training, about 15 years ago, Congress threw in place a stop-gap measure, putting a freeze on the total number of residency slots that would be funded, but it did not put any measures in place to ensure that the allocation of slots would match what the U.S. health-care system needs. This has left us in a global shortage of physicians, the most grotesque of which is among generalists in regions of greatest need.

The Good News

So where does this leave hospitalists? Fortunately for our specialty, hospital medicine remains very appealing to new graduates and to the health-care system. For new graduates, it offers a competitive salary and work-life balance, without additional fellowship training. For the health-care system, we are generalists who can enhance the “value equation,” having proven to enhance quality while simultaneously reducing cost. As generalists, our specialty remains relatively undifferentiated and flexible to meet the needs of the system, including caring for patients at many stages of an acute or chronic illness; pre-operative care; post-discharge transitions of care; and assisting in some stages of “specialty care” (e.g. the medical care of the neurologic emergency, the pregnant patient, comanagement with a variety of surgical subspecialists).

As a progressive specialty, we should continue to focus on the pipeline, not only to ensure we recruit our “favorite picks” to hospital medicine, but also to support the reform needed to enhance the appeal of generalist practices and reduce the irresistible appeal of specialty care. In this way, we can add yet another meaningful contribution to meeting the needs of the U.S. health-care system.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

- Longman P. First teach no harm. The Washington Monthly website. Available at: http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/july_august_2013/features/first_teach_no_harm045361.php?page=all. Accessed Aug. 4, 2013.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician shortages to worsen without increases in residency training. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/150612/data/md-shortage.pdf. Accessed Aug. 4, 2013.

As I was reading my departmental, end-of-the-academic-year newsletter, I was pondering my own group’s hospitalist pipeline. Each year, I earnestly read the list of internal-medicine-program graduates, focusing on what and where they are going to practice. I first selfishly scan the list for “hospital medicine, MUSC.” Then I go back and reread the list to see who I can now send my discharges to or who I can refer any new friends or relatives who move to town, scanning the list for “primary care, MUSC.”

This year, similar to recent years, the list for “primary care” is slim.

SHM has long been motivated to think about the pipeline, about how to get the best and the brightest interested in practicing HM, and practicing primary care, as they are vital partners in the spectrum of generalist care. We need to know and understand our pipeline: Where will they train, how will they be trained, will they be prepared to function and thrive in the medical industry of tomorrow? Regardless of how or where you practice, all of us should be thinking about our pipeline.

As such, all of us should be thinking about graduate medical education (GME), how it is funded, how much it is funded, and what regulations control the types of specialties that come out of U.S. training programs.1 This is especially true given the projected need for more hospitalists in all areas of the hospital of the future, the ever-expanding role of “specialty hospitalists,” and the need for hospitalists during the “peri-hospital” stay (from pre-operative clinics to post-discharge clinics). And this is especially true given the ongoing projected expanse of the primary-care shortage.

The career path for physicians starts long before medical school and is heavily shaped by what types of physicians they are exposed to, when they are exposed to them, and what their experience was. The periods of medical school and graduate medical education training can have a profound impact on the “health” of the U.S. health-care system and whether it is equipped to care for the needs of its citizens.

American taxpayers have long been in the business of funding the physician pipeline. The federal government invests $13 billion annually on graduate medical education subsidies. The money flows directly to teaching hospitals to pay for the salaries of the trainees and the salaries of the attendings who supervise their work, as well as the hospital overhead that has to be invested to house these trainees during their tenure.

Federal subsidies for apprenticeships are relatively unheard of in other industries; this funding stream was initiated with the passage of Medicare almost 50 years ago, under the provision that additional training for medical students would result in better and safer medical care for all Americans. However, what was not set up as a tagline to these federal subsidies was any type of accountability on process or outcome measures, such as how exactly do teaching hospitals invest their GME money, and how will they produce the types and amounts of physicians that the U.S. needs?

Cold, Hard Facts

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources, Health Resources and Services Administration, http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/hpsadetail.aspx

So what do Americans get for that annual $13 billion investment? We get what we should expect out of the “free will” of graduating residents: We get an oversupply of specialists in areas of abundance and an undersupply of generalists in most areas. The system “produces” the most appealing specialties (those handsomely reimbursed and highly prestigious), leaving a dwindling number of generalists to be spread thinly. And the most prestigious and top-ranked academic medical centers are the least likely to produce generalists. In many of these highly ranked training programs, less than 10% of their graduates go on to work in primary care, and even fewer work in rural or public health facilities. More than 20% of all residency programs produce no primary-care physicians (PCPs) at all. Despite the $13 billion annual investment, the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) predicts a shortage of 45,000 primary-care physicians by 2020.2

Because of this shortage, even fully insured Americans find the act of securing a generalist to be problematic: Almost 1 in 5 of us live in a federally designated primary-care-shortage area (see Figure 1).3 It is estimated that our current training programs will produce 40% fewer PCPs than will be needed to keep pace with the baby boomers and the insurance expansion of the Affordable Care Act. Attempts at using GME subsidies as a lever to increase the number of generalists have failed for decades. Almost 30 years ago, Dan Quayle petitioned Medicare to forgo any subsidies to training programs that did not commit to graduating at least 70% of trainees to primary-care careers, to no avail. Years later, the Institute of Medicine appealed to the federal government to reduce the training of specialists, and increase the training pool for generalists, to no avail. To reduce the financial burden of GME training, about 15 years ago, Congress threw in place a stop-gap measure, putting a freeze on the total number of residency slots that would be funded, but it did not put any measures in place to ensure that the allocation of slots would match what the U.S. health-care system needs. This has left us in a global shortage of physicians, the most grotesque of which is among generalists in regions of greatest need.

The Good News

So where does this leave hospitalists? Fortunately for our specialty, hospital medicine remains very appealing to new graduates and to the health-care system. For new graduates, it offers a competitive salary and work-life balance, without additional fellowship training. For the health-care system, we are generalists who can enhance the “value equation,” having proven to enhance quality while simultaneously reducing cost. As generalists, our specialty remains relatively undifferentiated and flexible to meet the needs of the system, including caring for patients at many stages of an acute or chronic illness; pre-operative care; post-discharge transitions of care; and assisting in some stages of “specialty care” (e.g. the medical care of the neurologic emergency, the pregnant patient, comanagement with a variety of surgical subspecialists).

As a progressive specialty, we should continue to focus on the pipeline, not only to ensure we recruit our “favorite picks” to hospital medicine, but also to support the reform needed to enhance the appeal of generalist practices and reduce the irresistible appeal of specialty care. In this way, we can add yet another meaningful contribution to meeting the needs of the U.S. health-care system.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

- Longman P. First teach no harm. The Washington Monthly website. Available at: http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/july_august_2013/features/first_teach_no_harm045361.php?page=all. Accessed Aug. 4, 2013.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician shortages to worsen without increases in residency training. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/150612/data/md-shortage.pdf. Accessed Aug. 4, 2013.

Consumer Reports' Hospital Quality Ratings Dubious

Who doesn’t know and love Consumer Reports? I personally have used this product to help me make a wide range of purchases, from child-care products to a new automobile. Consumer Reports has enjoyed a relatively unblemished reputation since its inception as an unbiased repository of invaluable information for consumers. This nonprofit advocacy organization advises consumers looking to purchase anything from small, menial items (e.g. blenders and toasters) to large, expensive ones (e.g. computers, lawn mowers, cars). It has been categorizing and publishing large-scale consumer feedback and in-house testing since 1936. According to Wikipedia, Consumer Reports has more than 7 million subscribers and runs a budget in excess of $21 million annually.

One of the reasons for its longstanding success is that it does not appear to have any hidden agenda. It does not have any partiality to a specific company or service, and therefore has maintained its impartial stance during testing and evaluation of any good or service. Its Consumer Reports magazine houses no advertisements in order to maintain its objectivity. Its only agenda is to reflect the interests and opinions of the consumers themselves, and its mission is to provide a “fair, just, and safe marketplace for all consumers and to empower consumers to protect themselves.”1 A perfect agent from which to seek advice.

And as a company, it has grown with the times, as it now hosts a variety of platforms from which consumers can seek advice. It has long hosted a website (ConsumerReports.org). Now it has Consumer Reports Television and The Consumerist blog, the latter of which accepts “tips” from anyone on what stories to cover, helpful tips for consumers, or interesting pictures. For a few years, there was also Consumer Reports WebWatch, which was aimed at improving the credibility of websites through rigorous investigative reporting.

So it seems that Consumer Reports could be a good avenue to seek advice on where to “consume” health care. And, in fact, it is now in the business of rating the health-care industry. Recent blog posts from Consumer Reports have entailed topics as wide-ranging as the number of uninsured in the U.S. to the number and types of recalls of food products.

The health part of the website covers beauty and personal care (sunscreens and anti-wrinkle serums), exercise and fitness (bikes and diet plans), foods (coffee to frozen meals), home medical supplies (heart rate and blood pressure monitors), vitamins, supplements, and, last but not least, health services. This last section rates health insurance, heart surgeons, heart screening tests, and hospitals.

It even goes so far as to “rate” medications; its Best Buy Drugs compares the cost and effectiveness of a variety of prescription drugs ranging from anti-hypertensives to diabetic agents.

In Focus: Hospitals

Consumer Reports’ latest foray into the health-care industry now includes reporting on the quality of hospitals. The current ratings evaluated more than 2,000 acute-care hospitals in the U.S. and came up with several rankings.

The first rating includes “patient outcomes,” which is a conglomerate of hospital-acquired central-line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) rates, select surgical-site-infection [SSI] rates, 30-day readmission rates (for acute MI [AMI], congestive heart failure [CHF], and pneumonia), and eight “Patient Safety Indicators” (derived from definitions from the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality [AHRQ], and includes pressure ulcers, pneumothorax, CLABSI, accidental puncture injury during surgery, and four postoperative complications, including VTE, sepsis, hip fracture, and wound dehiscence).

It also includes ratings of the patient experience (from a subset of HCAHPS questions) and two measures of hospital practices, including the use of electronic health records (from the American Hospital Association) and the use of “double scans” (simultaneous thoracic and abdominal CT scans).

From all of these ratings, Consumer Reports combined some of the metrics to arrive at a “Safety Score,” which ranges from 0 to 100 (100 being the safest), based on five categories, including infections (CLABSI and SSI), readmission rates (for AMI, CHF, and pneumonia), patient ratings of communication about their medications and about their discharge process, rate of double scans, and avoidance of the aforementioned AHRQ Patient Safety Indicators.

As to how potential patients are supposed to use this information, Consumer Reports gives the following advice to those wanting to know how the ratings can help a patient get better care: “They can help you compare hospitals in your area so you can choose the one that’s best for you. Even if you don’t have a choice of hospitals, our ratings can alert you to particular concerns so you can take steps to prevent problems no matter which hospital you go to. For example, if a hospital scores low in communicating with patients about what to do when they’re discharged, you should ask about discharge planning at the hospital you choose and make sure you know what to do when you leave.”

Overall, the average Safety Score for included hospitals was a 49, with a range from 14 to 74 across the U.S. Teaching hospitals were among the lowest scorers, with two-thirds of them rated below average.

At first blush, the numbers seem humbling, even startling, but it is not clear if they reflect bad care or bad metrics. Consumer Reports, similar to many other rating scales, has glued together a hodge-podge of different metrics and converted them into a summary score that may or may not line up with other organizational ratings (e.g. U.S. News and World Report, Leapfrog Group, Healthgrades, etc). Consumer Reports does acknowledge that none of the information for their rankings is actually collected from Consumer Reports but from other sources, such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Hospital Association (AHA).

The Bottom Line

Despite all this attention from Consumer Reports and others, online ratings are only used by about 14% of consumers to review hospitals or health-care facilities and by about 17% of consumers to review physicians or other health-care providers.2 Although the uptick is relatively low for use of online ratings to seek health care, that likely will change as the measurements get better and are more reflective of true care quality.

The bottom line for consumers is: Where do I want to be hospitalized when I get sick, and can I tell at the front end in which aspects a hospital is going to do well?

I think the answer for consumers should be to stay informed, always have an advocate at your side, and never stop asking questions.And for now, relegate Consumer Reports to purchases, not health care.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

- Consumer Reports. How we rate hospitals. Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/2012/10/how-we-rate-hospitals/index.htm. Accessed May 12, 2013.

- Pew Internet & American Life Project. Peer-to-peer health care. Pew Internet website. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Health-online/Part-Two/Section-2.aspx. Accessed May 12, 2013.

Who doesn’t know and love Consumer Reports? I personally have used this product to help me make a wide range of purchases, from child-care products to a new automobile. Consumer Reports has enjoyed a relatively unblemished reputation since its inception as an unbiased repository of invaluable information for consumers. This nonprofit advocacy organization advises consumers looking to purchase anything from small, menial items (e.g. blenders and toasters) to large, expensive ones (e.g. computers, lawn mowers, cars). It has been categorizing and publishing large-scale consumer feedback and in-house testing since 1936. According to Wikipedia, Consumer Reports has more than 7 million subscribers and runs a budget in excess of $21 million annually.

One of the reasons for its longstanding success is that it does not appear to have any hidden agenda. It does not have any partiality to a specific company or service, and therefore has maintained its impartial stance during testing and evaluation of any good or service. Its Consumer Reports magazine houses no advertisements in order to maintain its objectivity. Its only agenda is to reflect the interests and opinions of the consumers themselves, and its mission is to provide a “fair, just, and safe marketplace for all consumers and to empower consumers to protect themselves.”1 A perfect agent from which to seek advice.

And as a company, it has grown with the times, as it now hosts a variety of platforms from which consumers can seek advice. It has long hosted a website (ConsumerReports.org). Now it has Consumer Reports Television and The Consumerist blog, the latter of which accepts “tips” from anyone on what stories to cover, helpful tips for consumers, or interesting pictures. For a few years, there was also Consumer Reports WebWatch, which was aimed at improving the credibility of websites through rigorous investigative reporting.

So it seems that Consumer Reports could be a good avenue to seek advice on where to “consume” health care. And, in fact, it is now in the business of rating the health-care industry. Recent blog posts from Consumer Reports have entailed topics as wide-ranging as the number of uninsured in the U.S. to the number and types of recalls of food products.

The health part of the website covers beauty and personal care (sunscreens and anti-wrinkle serums), exercise and fitness (bikes and diet plans), foods (coffee to frozen meals), home medical supplies (heart rate and blood pressure monitors), vitamins, supplements, and, last but not least, health services. This last section rates health insurance, heart surgeons, heart screening tests, and hospitals.

It even goes so far as to “rate” medications; its Best Buy Drugs compares the cost and effectiveness of a variety of prescription drugs ranging from anti-hypertensives to diabetic agents.

In Focus: Hospitals

Consumer Reports’ latest foray into the health-care industry now includes reporting on the quality of hospitals. The current ratings evaluated more than 2,000 acute-care hospitals in the U.S. and came up with several rankings.

The first rating includes “patient outcomes,” which is a conglomerate of hospital-acquired central-line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) rates, select surgical-site-infection [SSI] rates, 30-day readmission rates (for acute MI [AMI], congestive heart failure [CHF], and pneumonia), and eight “Patient Safety Indicators” (derived from definitions from the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality [AHRQ], and includes pressure ulcers, pneumothorax, CLABSI, accidental puncture injury during surgery, and four postoperative complications, including VTE, sepsis, hip fracture, and wound dehiscence).

It also includes ratings of the patient experience (from a subset of HCAHPS questions) and two measures of hospital practices, including the use of electronic health records (from the American Hospital Association) and the use of “double scans” (simultaneous thoracic and abdominal CT scans).

From all of these ratings, Consumer Reports combined some of the metrics to arrive at a “Safety Score,” which ranges from 0 to 100 (100 being the safest), based on five categories, including infections (CLABSI and SSI), readmission rates (for AMI, CHF, and pneumonia), patient ratings of communication about their medications and about their discharge process, rate of double scans, and avoidance of the aforementioned AHRQ Patient Safety Indicators.

As to how potential patients are supposed to use this information, Consumer Reports gives the following advice to those wanting to know how the ratings can help a patient get better care: “They can help you compare hospitals in your area so you can choose the one that’s best for you. Even if you don’t have a choice of hospitals, our ratings can alert you to particular concerns so you can take steps to prevent problems no matter which hospital you go to. For example, if a hospital scores low in communicating with patients about what to do when they’re discharged, you should ask about discharge planning at the hospital you choose and make sure you know what to do when you leave.”

Overall, the average Safety Score for included hospitals was a 49, with a range from 14 to 74 across the U.S. Teaching hospitals were among the lowest scorers, with two-thirds of them rated below average.

At first blush, the numbers seem humbling, even startling, but it is not clear if they reflect bad care or bad metrics. Consumer Reports, similar to many other rating scales, has glued together a hodge-podge of different metrics and converted them into a summary score that may or may not line up with other organizational ratings (e.g. U.S. News and World Report, Leapfrog Group, Healthgrades, etc). Consumer Reports does acknowledge that none of the information for their rankings is actually collected from Consumer Reports but from other sources, such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Hospital Association (AHA).

The Bottom Line

Despite all this attention from Consumer Reports and others, online ratings are only used by about 14% of consumers to review hospitals or health-care facilities and by about 17% of consumers to review physicians or other health-care providers.2 Although the uptick is relatively low for use of online ratings to seek health care, that likely will change as the measurements get better and are more reflective of true care quality.

The bottom line for consumers is: Where do I want to be hospitalized when I get sick, and can I tell at the front end in which aspects a hospital is going to do well?

I think the answer for consumers should be to stay informed, always have an advocate at your side, and never stop asking questions.And for now, relegate Consumer Reports to purchases, not health care.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

- Consumer Reports. How we rate hospitals. Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/2012/10/how-we-rate-hospitals/index.htm. Accessed May 12, 2013.

- Pew Internet & American Life Project. Peer-to-peer health care. Pew Internet website. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Health-online/Part-Two/Section-2.aspx. Accessed May 12, 2013.

Who doesn’t know and love Consumer Reports? I personally have used this product to help me make a wide range of purchases, from child-care products to a new automobile. Consumer Reports has enjoyed a relatively unblemished reputation since its inception as an unbiased repository of invaluable information for consumers. This nonprofit advocacy organization advises consumers looking to purchase anything from small, menial items (e.g. blenders and toasters) to large, expensive ones (e.g. computers, lawn mowers, cars). It has been categorizing and publishing large-scale consumer feedback and in-house testing since 1936. According to Wikipedia, Consumer Reports has more than 7 million subscribers and runs a budget in excess of $21 million annually.

One of the reasons for its longstanding success is that it does not appear to have any hidden agenda. It does not have any partiality to a specific company or service, and therefore has maintained its impartial stance during testing and evaluation of any good or service. Its Consumer Reports magazine houses no advertisements in order to maintain its objectivity. Its only agenda is to reflect the interests and opinions of the consumers themselves, and its mission is to provide a “fair, just, and safe marketplace for all consumers and to empower consumers to protect themselves.”1 A perfect agent from which to seek advice.

And as a company, it has grown with the times, as it now hosts a variety of platforms from which consumers can seek advice. It has long hosted a website (ConsumerReports.org). Now it has Consumer Reports Television and The Consumerist blog, the latter of which accepts “tips” from anyone on what stories to cover, helpful tips for consumers, or interesting pictures. For a few years, there was also Consumer Reports WebWatch, which was aimed at improving the credibility of websites through rigorous investigative reporting.

So it seems that Consumer Reports could be a good avenue to seek advice on where to “consume” health care. And, in fact, it is now in the business of rating the health-care industry. Recent blog posts from Consumer Reports have entailed topics as wide-ranging as the number of uninsured in the U.S. to the number and types of recalls of food products.

The health part of the website covers beauty and personal care (sunscreens and anti-wrinkle serums), exercise and fitness (bikes and diet plans), foods (coffee to frozen meals), home medical supplies (heart rate and blood pressure monitors), vitamins, supplements, and, last but not least, health services. This last section rates health insurance, heart surgeons, heart screening tests, and hospitals.

It even goes so far as to “rate” medications; its Best Buy Drugs compares the cost and effectiveness of a variety of prescription drugs ranging from anti-hypertensives to diabetic agents.

In Focus: Hospitals

Consumer Reports’ latest foray into the health-care industry now includes reporting on the quality of hospitals. The current ratings evaluated more than 2,000 acute-care hospitals in the U.S. and came up with several rankings.

The first rating includes “patient outcomes,” which is a conglomerate of hospital-acquired central-line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) rates, select surgical-site-infection [SSI] rates, 30-day readmission rates (for acute MI [AMI], congestive heart failure [CHF], and pneumonia), and eight “Patient Safety Indicators” (derived from definitions from the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality [AHRQ], and includes pressure ulcers, pneumothorax, CLABSI, accidental puncture injury during surgery, and four postoperative complications, including VTE, sepsis, hip fracture, and wound dehiscence).

It also includes ratings of the patient experience (from a subset of HCAHPS questions) and two measures of hospital practices, including the use of electronic health records (from the American Hospital Association) and the use of “double scans” (simultaneous thoracic and abdominal CT scans).

From all of these ratings, Consumer Reports combined some of the metrics to arrive at a “Safety Score,” which ranges from 0 to 100 (100 being the safest), based on five categories, including infections (CLABSI and SSI), readmission rates (for AMI, CHF, and pneumonia), patient ratings of communication about their medications and about their discharge process, rate of double scans, and avoidance of the aforementioned AHRQ Patient Safety Indicators.

As to how potential patients are supposed to use this information, Consumer Reports gives the following advice to those wanting to know how the ratings can help a patient get better care: “They can help you compare hospitals in your area so you can choose the one that’s best for you. Even if you don’t have a choice of hospitals, our ratings can alert you to particular concerns so you can take steps to prevent problems no matter which hospital you go to. For example, if a hospital scores low in communicating with patients about what to do when they’re discharged, you should ask about discharge planning at the hospital you choose and make sure you know what to do when you leave.”

Overall, the average Safety Score for included hospitals was a 49, with a range from 14 to 74 across the U.S. Teaching hospitals were among the lowest scorers, with two-thirds of them rated below average.

At first blush, the numbers seem humbling, even startling, but it is not clear if they reflect bad care or bad metrics. Consumer Reports, similar to many other rating scales, has glued together a hodge-podge of different metrics and converted them into a summary score that may or may not line up with other organizational ratings (e.g. U.S. News and World Report, Leapfrog Group, Healthgrades, etc). Consumer Reports does acknowledge that none of the information for their rankings is actually collected from Consumer Reports but from other sources, such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Hospital Association (AHA).

The Bottom Line

Despite all this attention from Consumer Reports and others, online ratings are only used by about 14% of consumers to review hospitals or health-care facilities and by about 17% of consumers to review physicians or other health-care providers.2 Although the uptick is relatively low for use of online ratings to seek health care, that likely will change as the measurements get better and are more reflective of true care quality.

The bottom line for consumers is: Where do I want to be hospitalized when I get sick, and can I tell at the front end in which aspects a hospital is going to do well?

I think the answer for consumers should be to stay informed, always have an advocate at your side, and never stop asking questions.And for now, relegate Consumer Reports to purchases, not health care.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

- Consumer Reports. How we rate hospitals. Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/2012/10/how-we-rate-hospitals/index.htm. Accessed May 12, 2013.

- Pew Internet & American Life Project. Peer-to-peer health care. Pew Internet website. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Health-online/Part-Two/Section-2.aspx. Accessed May 12, 2013.

Medicare Outlines Anticipated Funding Changes Under Affordable Care Act

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently released a few Fact Sheets on how they anticipate funding changes on a few of their programs that were implemented (or sustained) under the Affordable Care Act. As a background, CMS pays most acute-care hospitals by prospectively determining payment based on a patient’s diagnosis and the severity of illness within that diagnosis (e.g. “MS-DRG”). These payment amounts are updated annually after evaluating several factors, including the costs associated with the delivery of care.

One of the most major changes described in the Fact Sheet that will affect hospitalists is how CMS will review inpatient stays based on the number of nights in the hospital. CMS has proposed that any patient who stays in the hospital for two or more “midnights” should be appropriate for payment under Medicare Part A. For those who stay in the hospital for only one (or zero) midnights, payment under Medicare Part A will only be appropriate if:

- There is sufficient documentation at the time of admission that the anticipated length of stay is two or more nights; and.

- Further documentation that circumstances changed, and the hospital stay ended prematurely because of those changes.

Overall for hospitalists, this should substantially simplify the admitting process, whereby most inpatients being admitted with the anticipation of two or more nights should qualify for an inpatient stay. This also reduces the administrative burden of correcting the “inpatient” versus “observation” designation, which keeps many hospital staffs entirely too busy. This change also should relieve a significant burden from the patients and their families, who if kept in observation for a period of time, may have to pay substantially out of pocket to make up for the difference between the cost of the stay and the reimbursement from CMS for observation status. So this is one of the moves that CMS is making to simplify (and not complicate) an already too-complicated payment system. This should go into effect October 2013 and will be a sigh of much relief from many of us.

A few other anticipated changes that will affect hospitalists include:

Payments for Unfunded Care

Another major change that will go into affect October 2013 is the amount of monies received by hospitals that care for unfunded patients. These payments historically have been made to “Disproportionate Share Hospitals” (DSH), which are hospitals that care for a higher percentage of unfunded patients. Under the Affordable Care Act, only 25% of these payments will be distributed to DSH hospitals; the remaining 75% will be reduced based on the number of uninsured in the U.S., then redistributed to DSH hospitals based on their portion of uninsured care delivered.

Most DSH hospitals should expect a decrease in DSH payments, the amount of which will depend on their share of unfunded patients.

Any reduction in the “bottom line” to the hospital can affect hospitalists, especially those who are directly employed by the hospital.

Hospital-Acquired Conditions

CMS has long had the Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) program in effect, which has the ability to reduce the amount of payment for inpatients who acquire a HAC during their hospital stay. Starting in October 2014, CMS will impose additional financial penalties for hospitals with high HAC rates.

Specifically, those hospitals in the highest 25th percentile of HAC rates will be penalized 1% of their overall CMS payments. Another proposed change is that the following be included in the HAC reduction plan (two “domains” of measures):

- Domain No. 1: Six of the AHRQ Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs), including pressure ulcers, foreign bodies left in after surgery, iatrogenic pneumothorax, postoperative physiologic or metabolic derangements, postoperative VTE, and accidental puncture/laceration.

- Domain No. 2: Central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs).

The domains will be weighted equally, and an average score will determine the total score. There will be some methodology for risk adjustment, and hospitals will be given a review and comment period to validate their own scores.

Most hospitalists have at least indirect control over many of these HACs,and all need to pay very close attention to their hospital’s rates of these now and in the future.

Readmissions

As we all know, the Hospital Readmission Reduction program went into effect October 2012; it placed 1% of CMS payments at risk. This will increase to 2% of payments as of October 2013. CMS will continue to use AMI, CHF, and pneumonia as the three conditions under which the readmissions are measured but will put in some methodology to account for planned readmissions.

In addition, in October 2014, they plan to add readmission rates for COPD and for hip/knee arthroplasty.

Hospitalists will continue to need to progress their transitions of care programs, at least for these five patients conditions but more likely (and more effectively) for all hospital discharges.

Quality Measures

Currently more than 99% of acute-care hospitals participate in the pay-for-reporting quality program through CMS, the results of which have been displayed on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov) for years. The program started in 2004 with 10 quality metrics and now includes 57 metrics. These include process and outcome measures for AMI, CHF, and pneumonia, as well as process measures for surgical care, HACs, and patient-satisfaction surveys, among others.

This program will continue to expand over time, including hospital-acquired MRSA and Clostridium difficile rates. The few hospitals not participating will have their CMS annual payments reduced by 2%.

EHR Incentives

CMS is evaluating ways to reduce the burden of reporting by aligning EHR incentives with the Inpatient Quality Reporting program.

Summary

After an open commentary period, the Final Rule will be published Aug. 1, and will become effective for discharges on or after Oct. 1. Although CMS will continue to expand the total number of measures that need to be reported, and the penalties for non-reporting or low performance will continue to escalate, CMS is at least attempting to reduce the overall burden of reporting by combining measures and programs over time and using EHRs to facilitate the bulk of reporting over time.

The global message to hospitalists is: Continue to focus on reducing the burden of HACs, enhance throughput, and carefully and thoughtfully transition patients to the next provider after their hospital discharge. All in all, although at times this can feel overwhelming, these changes represent the right direction to move for high-quality and safe patient care.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

Reference

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently released a few Fact Sheets on how they anticipate funding changes on a few of their programs that were implemented (or sustained) under the Affordable Care Act. As a background, CMS pays most acute-care hospitals by prospectively determining payment based on a patient’s diagnosis and the severity of illness within that diagnosis (e.g. “MS-DRG”). These payment amounts are updated annually after evaluating several factors, including the costs associated with the delivery of care.

One of the most major changes described in the Fact Sheet that will affect hospitalists is how CMS will review inpatient stays based on the number of nights in the hospital. CMS has proposed that any patient who stays in the hospital for two or more “midnights” should be appropriate for payment under Medicare Part A. For those who stay in the hospital for only one (or zero) midnights, payment under Medicare Part A will only be appropriate if:

- There is sufficient documentation at the time of admission that the anticipated length of stay is two or more nights; and.

- Further documentation that circumstances changed, and the hospital stay ended prematurely because of those changes.

Overall for hospitalists, this should substantially simplify the admitting process, whereby most inpatients being admitted with the anticipation of two or more nights should qualify for an inpatient stay. This also reduces the administrative burden of correcting the “inpatient” versus “observation” designation, which keeps many hospital staffs entirely too busy. This change also should relieve a significant burden from the patients and their families, who if kept in observation for a period of time, may have to pay substantially out of pocket to make up for the difference between the cost of the stay and the reimbursement from CMS for observation status. So this is one of the moves that CMS is making to simplify (and not complicate) an already too-complicated payment system. This should go into effect October 2013 and will be a sigh of much relief from many of us.

A few other anticipated changes that will affect hospitalists include:

Payments for Unfunded Care

Another major change that will go into affect October 2013 is the amount of monies received by hospitals that care for unfunded patients. These payments historically have been made to “Disproportionate Share Hospitals” (DSH), which are hospitals that care for a higher percentage of unfunded patients. Under the Affordable Care Act, only 25% of these payments will be distributed to DSH hospitals; the remaining 75% will be reduced based on the number of uninsured in the U.S., then redistributed to DSH hospitals based on their portion of uninsured care delivered.

Most DSH hospitals should expect a decrease in DSH payments, the amount of which will depend on their share of unfunded patients.

Any reduction in the “bottom line” to the hospital can affect hospitalists, especially those who are directly employed by the hospital.

Hospital-Acquired Conditions

CMS has long had the Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) program in effect, which has the ability to reduce the amount of payment for inpatients who acquire a HAC during their hospital stay. Starting in October 2014, CMS will impose additional financial penalties for hospitals with high HAC rates.

Specifically, those hospitals in the highest 25th percentile of HAC rates will be penalized 1% of their overall CMS payments. Another proposed change is that the following be included in the HAC reduction plan (two “domains” of measures):

- Domain No. 1: Six of the AHRQ Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs), including pressure ulcers, foreign bodies left in after surgery, iatrogenic pneumothorax, postoperative physiologic or metabolic derangements, postoperative VTE, and accidental puncture/laceration.

- Domain No. 2: Central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs).

The domains will be weighted equally, and an average score will determine the total score. There will be some methodology for risk adjustment, and hospitals will be given a review and comment period to validate their own scores.

Most hospitalists have at least indirect control over many of these HACs,and all need to pay very close attention to their hospital’s rates of these now and in the future.

Readmissions

As we all know, the Hospital Readmission Reduction program went into effect October 2012; it placed 1% of CMS payments at risk. This will increase to 2% of payments as of October 2013. CMS will continue to use AMI, CHF, and pneumonia as the three conditions under which the readmissions are measured but will put in some methodology to account for planned readmissions.

In addition, in October 2014, they plan to add readmission rates for COPD and for hip/knee arthroplasty.

Hospitalists will continue to need to progress their transitions of care programs, at least for these five patients conditions but more likely (and more effectively) for all hospital discharges.

Quality Measures