User login

Collaborations with Pediatric Hospitalists: National Surveys of Pediatric Surgeons and Orthopedic Surgeons

Pediatric expertise is critical in caring for children during the perioperative and postoperative periods.1,2 Some postoperative care models involve pediatric hospitalists (PH) as collaborators for global care (comanagement),3 as consultants for specific issues, or not at all.

Single-site studies in specific pediatric surgical populations4-7and medically fragile adults8 suggest improved outcomes for patients and systems by using hospitalist-surgeon collaboration. However, including PH in the care of surgical patients may also disrupt systems. No studies have broadly examined the clinical relationships between surgeons and PH.

The aims of this cross-sectional survey of US pediatric surgeons (PS) and pediatric orthopedic surgeons (OS) were to understand (1) the prevalence and characteristics of surgical care models in pediatrics, specifically those involving PH, and (2) surgeons’ perceptions of PH in caring for surgical patients.

METHODS

The target US surgeon population was the estimated 850 active PS and at least 600 pediatric OS.9 Most US PS (n = 606) are affiliated with the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Section on Surgery (SoSu), representing at least 200 programs. Nearly all pediatric OS belong to the Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America (POSNA) (n = 706), representing 340 programs; a subset (n = 130) also belong to the AAP SoSu.

Survey Development and Distribution

Survey questions were developed to elicit surgeons’ descriptions of their program structure and their perceptions of PH involvement. For programs with PH involvement, program variables included primary assignment of clinical responsibilities by service line (surgery, hospitalist, shared) and use of a written service agreement, which defines each service’s roles and responsibilities.

The web-based survey, created by using Survey Monkey (San Mateo, CA), was pilot tested for usability and clarity among 8 surgeons and 1 PH. The survey had logic points around involvement of hospitalists and multiple hospital affiliations (supplemental Appendix A). The survey request with a web-based link was e-mailed 3 times to surgical and orthopedic distribution outlets, endorsed by organizational leadership. Respondents’ hospital ZIP codes were used as a proxy for program. If there was more than 1 complete survey response per ZIP code, 1 response with complete data was randomly selected to ensure a unique entry per program.

Classification of Care Models

Each surgical program was classified into 1 of the following 3 categories based on reported care of primary surgical patients: (1) comanagement, described as PH writing orders and/or functioning as the primary service; (2) consultation, described as PH providing clinical recommendations only; and (3) no PH involvement, described as “rarely” or “never” involving PH.

Clinical Responsibility Score

To estimate the degree of hospitalist involvement, we devised and calculated a composite score of service responsibilities for each program. This score involved the following 7 clinical domains: management of fluids or nutrition, pain, comorbidities, antibiotics, medication dosing, wound care, and discharge planning. Scores were summed for each domain: 0 for surgical team primary responsibility, 1 for shared surgical and hospitalist responsibility, and 2 for hospitalist primary responsibility. Composite scores could range from 0 to 14; lower scores represented a stronger tendency for surgeon management, and higher scores represented a stronger tendency toward PH management.

Data Analysis

For data analysis, simple exploratory tests with χ2 analysis and Student t tests were performed by using Stata 14.2 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) to compare differences by surgical specialty programs and individuals by role assignment and perceptions of PH involvement.

The NYU School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study.

RESULTS

Respondents and Programs

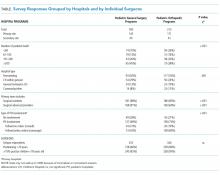

Among the unique 185 PS programs and 212 OS programs represented, PH were often engaged in the care of primary surgical patients (Table).

Roles of PH in Collaborative Programs

Among programs that reported any hospitalist involvement (PS, n = 100; OS, n = 157), few (≤15%) programs involved hospitalists with all patients. Pediatric OS programs were significantly more likely than pediatric surgical programs to involve PH for healthy patients with any high-risk surgery (27% vs 9%; P = .001). Most PS (64%) and OS (83%) reported involving PH for all medically complex patients, regardless of surgery risk (P = .003).

In programs involving PH, few PS (11%) or OS programs (16%) reported by using a written service agreement.

Care of Surgical Patients in PH-involved programs

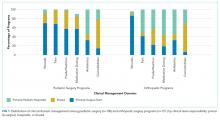

Composite clinical responsibility scores ranged from 0 to 8, with a median score of 2.3 (interquartile range [IQR] 0-3) for consultation programs and 5 (IQR 1-7) for comanagement programs. Composite scores were higher for OS (7.4; SD 3.4) versus PS (3.3; SD 3.4) programs (P < .001; 95% CI, 3.3-5.5; supplemental Appendix C).

Surgeons’ Perspectives on Hospitalist Involvement

Surgeons in programs without PH involvement viewed PH overall impact less positively than those with PH (27% vs 58%). Among all surgeons surveyed, few perceived positive (agree/strongly agree) PH impact on pain management (<15%) or decreasing LOS (<15%; supplemental Appendix D).

Most surgeons (n = 355) believed that PH financial support should come from separate billing (“patient fee”) (48%) or hospital budget (36%). Only 17% endorsed PH receiving part of the surgical global fee, with no significant difference by surgical specialty or current PH involvement status.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first comprehensive assessment of surgeons’ perspectives on the involvement and effectiveness of PH in the postoperative care of children undergoing inpatient general or orthopedic surgeries. The high prevalence (>70%) of PH involvement among responding surgical programs suggests that PH comanagement of hospitalized patients merits attention from providers, systems, educators, and payors.

Collaboration and Roles are Correlated with Surgical Specialty and Setting

Forty percent of inpatient pediatric surgeries occur outside of children’s hospitals.10 We found that PH involvement was higher at smaller and general hospitals where PH may provide pediatric expertise when insufficient pediatric resources, like pain teams, exist.7 Alternately, some quaternary centers have dedicated surgical hospitalists. The extensive involvement of PH in the bulk of certain clinical care domains, especially care coordination, in OS and in many PS programs (Figure) suggests that PH are well integrated into many programs and provide essential clinical care.

In many large freestanding children’s hospitals, though, surgical teams may have sufficient depth and breadth to manage most aspects of care. There may be an exception for care coordination of medically complex patients. Care coordination is a patient- and family-centered care best practice,11 encompasses integrating and aligning medical care among clinical services, and is focused on shared decision making and communication. High-quality care coordination processes are of great value to patients and families, especially in medically complex children,11 and are associated with improved transitions from hospital to home.12 Well-planned transitions likely decrease these special populations’ postoperative readmission risk, complications, and prolonged length of stay.13 Reimbursement for these services could integrate these contributions needed for safe and patient-centered pediatric inpatient surgical care.

Perceptions of PH Impact

The variation in perception of PH by surgical specialty, with higher prevalence as well as higher regard for PH among OS, is intriguing. This disparity may reflect current training and clinical expectations of each surgical specialty, with larger emphasis on medical management for surgical compared with orthopedic curricula (www.acgme.org).

While PS and OS respondents perceived that PH involvement did not influence length of stay, pain management, and resource use, single-site studies suggest otherwise.4,8,14 Objective data on the impact of PH involvement on patient and systems outcomes may help elucidate whether this is a perceived or actual lack of impact. Future metrics might include pain scores, patient centered care measures on communication and coordination, patient complaints and/or lawsuits, resource utilization and/or cost, readmission, and medical errors.

This study has several limitations. There is likely a (self) selection bias by surgeons with either strongly positive or negative views of PH involvement. Future studies may target a random sampling of programs rather than a cross-sectional survey of individual providers. Relatively few respondents represented community hospitals, possibly because these facilities are staffed by general OS and general surgeons10 who were not included in this sample.

CONCLUSION

Given the high prevalence of PH involvement in caring for surgical pediatric patients in varied settings, the field of pediatric hospital medicine should support increased PH training and standardized practice around perioperative management, particularly for medically complex patients with increased care coordination needs. Surgical comanagement, including interdisciplinary communication skills, deserves inclusion as a PH core competency and as an entrustable professional activity for pediatric hospital medicine and pediatric graduate medical education programs,15 especially orthopedic surgeries.

Further research on effective and evidence-based pediatric postoperative care and collaboration models will help PH and surgeons to most effectively and respectfully partner to improve care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine Surgical Care Subcommittee, AAP SOHM leadership, and Ms. Alexandra Case.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript to report. This study was supported in part by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (LM, R00HS022198).

1. Task Force for Children’s Surgical Care. Optimal resources for children’s surgical care in the United States. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(3):479-487, 487.e1-4. PubMed

2. Section on Hospital Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics. Guiding principles for pediatric hospital medicine programs. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):782-786. PubMed

3. Freiburg C, James T, Ashikaga T, Moalem J, Cherr G. Strategies to accommodate resident work-hour restrictions: Impact on surgical education. J Surg Educ. 2011;68(5):387-392. PubMed

4. Pressel DM, Rappaport DI, Watson N. Nurses’ assessment of pediatric physicians: Are hospitalists different? J Healthc Manag. 2008;53(1):14-24; discussion 24-25. PubMed

5. Simon TD, Eilert R, Dickinson LM, Kempe A, Benefield E, Berman S. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of spinal fusion surgery patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(1):23-30. PubMed

6. Rosenberg RE, Ardalan K, Wong W, et al. Postoperative spinal fusion care in pediatric patients: Co-management decreases length of stay. Bull Hosp Jt Dis (2013). 2014;72(3):197-203. PubMed

7. Dua K, McAvoy WC, Klaus SA, Rappaport DI, Rosenberg RE, Abzug JM. Hospitalist co-management of pediatric orthopaedic surgical patients at a community hospital. Md Med. 2016;17(1):34-36. PubMed

8. Rohatgi N, Loftus P, Grujic O, Cullen M, Hopkins J, Ahuja N. Surgical comanagement by hospitalists improves patient outcomes: A propensity score analysis. Ann Surg. 2016;264(2):275-282. PubMed

9. Poley S, Ricketts T, Belsky D, Gaul K. Pediatric surgeons: Subspecialists increase faster than generalists. Bull Amer Coll Surg. 2010;95(10):36-39. PubMed

10. Somme S, Bronsert M, Morrato E, Ziegler M. Frequency and variety of inpatient pediatric surgical procedures in the United States. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):e1466-e1472. PubMed

11. Frampton SB, Guastello S, Hoy L, Naylor M, Sheridan S, Johnston-Fleece M, eds. Harnessing Evidence and Experience to Change Culture: A Guiding Framework for Patient and Family Engaged Care. Washington, DC: National Academies of Medicine; 2017.

12. Auger KA, Kenyon CC, Feudtner C, Davis MM. Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: A systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):251-260. PubMed

13. Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the united states. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647-655. PubMed

14. Rappaport DI, Adelizzi-Delany J, Rogers KJ, et al. Outcomes and costs associated with hospitalist comanagement of medically complex children undergoing spinal fusion surgery. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):233-241. PubMed

15. Jerardi K, Meier K, Shaughnessy E. Management of postoperative pediatric patients. MedEdPORTAL. 2015;11:10241. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10241.

Pediatric expertise is critical in caring for children during the perioperative and postoperative periods.1,2 Some postoperative care models involve pediatric hospitalists (PH) as collaborators for global care (comanagement),3 as consultants for specific issues, or not at all.

Single-site studies in specific pediatric surgical populations4-7and medically fragile adults8 suggest improved outcomes for patients and systems by using hospitalist-surgeon collaboration. However, including PH in the care of surgical patients may also disrupt systems. No studies have broadly examined the clinical relationships between surgeons and PH.

The aims of this cross-sectional survey of US pediatric surgeons (PS) and pediatric orthopedic surgeons (OS) were to understand (1) the prevalence and characteristics of surgical care models in pediatrics, specifically those involving PH, and (2) surgeons’ perceptions of PH in caring for surgical patients.

METHODS

The target US surgeon population was the estimated 850 active PS and at least 600 pediatric OS.9 Most US PS (n = 606) are affiliated with the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Section on Surgery (SoSu), representing at least 200 programs. Nearly all pediatric OS belong to the Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America (POSNA) (n = 706), representing 340 programs; a subset (n = 130) also belong to the AAP SoSu.

Survey Development and Distribution

Survey questions were developed to elicit surgeons’ descriptions of their program structure and their perceptions of PH involvement. For programs with PH involvement, program variables included primary assignment of clinical responsibilities by service line (surgery, hospitalist, shared) and use of a written service agreement, which defines each service’s roles and responsibilities.

The web-based survey, created by using Survey Monkey (San Mateo, CA), was pilot tested for usability and clarity among 8 surgeons and 1 PH. The survey had logic points around involvement of hospitalists and multiple hospital affiliations (supplemental Appendix A). The survey request with a web-based link was e-mailed 3 times to surgical and orthopedic distribution outlets, endorsed by organizational leadership. Respondents’ hospital ZIP codes were used as a proxy for program. If there was more than 1 complete survey response per ZIP code, 1 response with complete data was randomly selected to ensure a unique entry per program.

Classification of Care Models

Each surgical program was classified into 1 of the following 3 categories based on reported care of primary surgical patients: (1) comanagement, described as PH writing orders and/or functioning as the primary service; (2) consultation, described as PH providing clinical recommendations only; and (3) no PH involvement, described as “rarely” or “never” involving PH.

Clinical Responsibility Score

To estimate the degree of hospitalist involvement, we devised and calculated a composite score of service responsibilities for each program. This score involved the following 7 clinical domains: management of fluids or nutrition, pain, comorbidities, antibiotics, medication dosing, wound care, and discharge planning. Scores were summed for each domain: 0 for surgical team primary responsibility, 1 for shared surgical and hospitalist responsibility, and 2 for hospitalist primary responsibility. Composite scores could range from 0 to 14; lower scores represented a stronger tendency for surgeon management, and higher scores represented a stronger tendency toward PH management.

Data Analysis

For data analysis, simple exploratory tests with χ2 analysis and Student t tests were performed by using Stata 14.2 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) to compare differences by surgical specialty programs and individuals by role assignment and perceptions of PH involvement.

The NYU School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study.

RESULTS

Respondents and Programs

Among the unique 185 PS programs and 212 OS programs represented, PH were often engaged in the care of primary surgical patients (Table).

Roles of PH in Collaborative Programs

Among programs that reported any hospitalist involvement (PS, n = 100; OS, n = 157), few (≤15%) programs involved hospitalists with all patients. Pediatric OS programs were significantly more likely than pediatric surgical programs to involve PH for healthy patients with any high-risk surgery (27% vs 9%; P = .001). Most PS (64%) and OS (83%) reported involving PH for all medically complex patients, regardless of surgery risk (P = .003).

In programs involving PH, few PS (11%) or OS programs (16%) reported by using a written service agreement.

Care of Surgical Patients in PH-involved programs

Composite clinical responsibility scores ranged from 0 to 8, with a median score of 2.3 (interquartile range [IQR] 0-3) for consultation programs and 5 (IQR 1-7) for comanagement programs. Composite scores were higher for OS (7.4; SD 3.4) versus PS (3.3; SD 3.4) programs (P < .001; 95% CI, 3.3-5.5; supplemental Appendix C).

Surgeons’ Perspectives on Hospitalist Involvement

Surgeons in programs without PH involvement viewed PH overall impact less positively than those with PH (27% vs 58%). Among all surgeons surveyed, few perceived positive (agree/strongly agree) PH impact on pain management (<15%) or decreasing LOS (<15%; supplemental Appendix D).

Most surgeons (n = 355) believed that PH financial support should come from separate billing (“patient fee”) (48%) or hospital budget (36%). Only 17% endorsed PH receiving part of the surgical global fee, with no significant difference by surgical specialty or current PH involvement status.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first comprehensive assessment of surgeons’ perspectives on the involvement and effectiveness of PH in the postoperative care of children undergoing inpatient general or orthopedic surgeries. The high prevalence (>70%) of PH involvement among responding surgical programs suggests that PH comanagement of hospitalized patients merits attention from providers, systems, educators, and payors.

Collaboration and Roles are Correlated with Surgical Specialty and Setting

Forty percent of inpatient pediatric surgeries occur outside of children’s hospitals.10 We found that PH involvement was higher at smaller and general hospitals where PH may provide pediatric expertise when insufficient pediatric resources, like pain teams, exist.7 Alternately, some quaternary centers have dedicated surgical hospitalists. The extensive involvement of PH in the bulk of certain clinical care domains, especially care coordination, in OS and in many PS programs (Figure) suggests that PH are well integrated into many programs and provide essential clinical care.

In many large freestanding children’s hospitals, though, surgical teams may have sufficient depth and breadth to manage most aspects of care. There may be an exception for care coordination of medically complex patients. Care coordination is a patient- and family-centered care best practice,11 encompasses integrating and aligning medical care among clinical services, and is focused on shared decision making and communication. High-quality care coordination processes are of great value to patients and families, especially in medically complex children,11 and are associated with improved transitions from hospital to home.12 Well-planned transitions likely decrease these special populations’ postoperative readmission risk, complications, and prolonged length of stay.13 Reimbursement for these services could integrate these contributions needed for safe and patient-centered pediatric inpatient surgical care.

Perceptions of PH Impact

The variation in perception of PH by surgical specialty, with higher prevalence as well as higher regard for PH among OS, is intriguing. This disparity may reflect current training and clinical expectations of each surgical specialty, with larger emphasis on medical management for surgical compared with orthopedic curricula (www.acgme.org).

While PS and OS respondents perceived that PH involvement did not influence length of stay, pain management, and resource use, single-site studies suggest otherwise.4,8,14 Objective data on the impact of PH involvement on patient and systems outcomes may help elucidate whether this is a perceived or actual lack of impact. Future metrics might include pain scores, patient centered care measures on communication and coordination, patient complaints and/or lawsuits, resource utilization and/or cost, readmission, and medical errors.

This study has several limitations. There is likely a (self) selection bias by surgeons with either strongly positive or negative views of PH involvement. Future studies may target a random sampling of programs rather than a cross-sectional survey of individual providers. Relatively few respondents represented community hospitals, possibly because these facilities are staffed by general OS and general surgeons10 who were not included in this sample.

CONCLUSION

Given the high prevalence of PH involvement in caring for surgical pediatric patients in varied settings, the field of pediatric hospital medicine should support increased PH training and standardized practice around perioperative management, particularly for medically complex patients with increased care coordination needs. Surgical comanagement, including interdisciplinary communication skills, deserves inclusion as a PH core competency and as an entrustable professional activity for pediatric hospital medicine and pediatric graduate medical education programs,15 especially orthopedic surgeries.

Further research on effective and evidence-based pediatric postoperative care and collaboration models will help PH and surgeons to most effectively and respectfully partner to improve care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine Surgical Care Subcommittee, AAP SOHM leadership, and Ms. Alexandra Case.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript to report. This study was supported in part by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (LM, R00HS022198).

Pediatric expertise is critical in caring for children during the perioperative and postoperative periods.1,2 Some postoperative care models involve pediatric hospitalists (PH) as collaborators for global care (comanagement),3 as consultants for specific issues, or not at all.

Single-site studies in specific pediatric surgical populations4-7and medically fragile adults8 suggest improved outcomes for patients and systems by using hospitalist-surgeon collaboration. However, including PH in the care of surgical patients may also disrupt systems. No studies have broadly examined the clinical relationships between surgeons and PH.

The aims of this cross-sectional survey of US pediatric surgeons (PS) and pediatric orthopedic surgeons (OS) were to understand (1) the prevalence and characteristics of surgical care models in pediatrics, specifically those involving PH, and (2) surgeons’ perceptions of PH in caring for surgical patients.

METHODS

The target US surgeon population was the estimated 850 active PS and at least 600 pediatric OS.9 Most US PS (n = 606) are affiliated with the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Section on Surgery (SoSu), representing at least 200 programs. Nearly all pediatric OS belong to the Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America (POSNA) (n = 706), representing 340 programs; a subset (n = 130) also belong to the AAP SoSu.

Survey Development and Distribution

Survey questions were developed to elicit surgeons’ descriptions of their program structure and their perceptions of PH involvement. For programs with PH involvement, program variables included primary assignment of clinical responsibilities by service line (surgery, hospitalist, shared) and use of a written service agreement, which defines each service’s roles and responsibilities.

The web-based survey, created by using Survey Monkey (San Mateo, CA), was pilot tested for usability and clarity among 8 surgeons and 1 PH. The survey had logic points around involvement of hospitalists and multiple hospital affiliations (supplemental Appendix A). The survey request with a web-based link was e-mailed 3 times to surgical and orthopedic distribution outlets, endorsed by organizational leadership. Respondents’ hospital ZIP codes were used as a proxy for program. If there was more than 1 complete survey response per ZIP code, 1 response with complete data was randomly selected to ensure a unique entry per program.

Classification of Care Models

Each surgical program was classified into 1 of the following 3 categories based on reported care of primary surgical patients: (1) comanagement, described as PH writing orders and/or functioning as the primary service; (2) consultation, described as PH providing clinical recommendations only; and (3) no PH involvement, described as “rarely” or “never” involving PH.

Clinical Responsibility Score

To estimate the degree of hospitalist involvement, we devised and calculated a composite score of service responsibilities for each program. This score involved the following 7 clinical domains: management of fluids or nutrition, pain, comorbidities, antibiotics, medication dosing, wound care, and discharge planning. Scores were summed for each domain: 0 for surgical team primary responsibility, 1 for shared surgical and hospitalist responsibility, and 2 for hospitalist primary responsibility. Composite scores could range from 0 to 14; lower scores represented a stronger tendency for surgeon management, and higher scores represented a stronger tendency toward PH management.

Data Analysis

For data analysis, simple exploratory tests with χ2 analysis and Student t tests were performed by using Stata 14.2 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) to compare differences by surgical specialty programs and individuals by role assignment and perceptions of PH involvement.

The NYU School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study.

RESULTS

Respondents and Programs

Among the unique 185 PS programs and 212 OS programs represented, PH were often engaged in the care of primary surgical patients (Table).

Roles of PH in Collaborative Programs

Among programs that reported any hospitalist involvement (PS, n = 100; OS, n = 157), few (≤15%) programs involved hospitalists with all patients. Pediatric OS programs were significantly more likely than pediatric surgical programs to involve PH for healthy patients with any high-risk surgery (27% vs 9%; P = .001). Most PS (64%) and OS (83%) reported involving PH for all medically complex patients, regardless of surgery risk (P = .003).

In programs involving PH, few PS (11%) or OS programs (16%) reported by using a written service agreement.

Care of Surgical Patients in PH-involved programs

Composite clinical responsibility scores ranged from 0 to 8, with a median score of 2.3 (interquartile range [IQR] 0-3) for consultation programs and 5 (IQR 1-7) for comanagement programs. Composite scores were higher for OS (7.4; SD 3.4) versus PS (3.3; SD 3.4) programs (P < .001; 95% CI, 3.3-5.5; supplemental Appendix C).

Surgeons’ Perspectives on Hospitalist Involvement

Surgeons in programs without PH involvement viewed PH overall impact less positively than those with PH (27% vs 58%). Among all surgeons surveyed, few perceived positive (agree/strongly agree) PH impact on pain management (<15%) or decreasing LOS (<15%; supplemental Appendix D).

Most surgeons (n = 355) believed that PH financial support should come from separate billing (“patient fee”) (48%) or hospital budget (36%). Only 17% endorsed PH receiving part of the surgical global fee, with no significant difference by surgical specialty or current PH involvement status.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first comprehensive assessment of surgeons’ perspectives on the involvement and effectiveness of PH in the postoperative care of children undergoing inpatient general or orthopedic surgeries. The high prevalence (>70%) of PH involvement among responding surgical programs suggests that PH comanagement of hospitalized patients merits attention from providers, systems, educators, and payors.

Collaboration and Roles are Correlated with Surgical Specialty and Setting

Forty percent of inpatient pediatric surgeries occur outside of children’s hospitals.10 We found that PH involvement was higher at smaller and general hospitals where PH may provide pediatric expertise when insufficient pediatric resources, like pain teams, exist.7 Alternately, some quaternary centers have dedicated surgical hospitalists. The extensive involvement of PH in the bulk of certain clinical care domains, especially care coordination, in OS and in many PS programs (Figure) suggests that PH are well integrated into many programs and provide essential clinical care.

In many large freestanding children’s hospitals, though, surgical teams may have sufficient depth and breadth to manage most aspects of care. There may be an exception for care coordination of medically complex patients. Care coordination is a patient- and family-centered care best practice,11 encompasses integrating and aligning medical care among clinical services, and is focused on shared decision making and communication. High-quality care coordination processes are of great value to patients and families, especially in medically complex children,11 and are associated with improved transitions from hospital to home.12 Well-planned transitions likely decrease these special populations’ postoperative readmission risk, complications, and prolonged length of stay.13 Reimbursement for these services could integrate these contributions needed for safe and patient-centered pediatric inpatient surgical care.

Perceptions of PH Impact

The variation in perception of PH by surgical specialty, with higher prevalence as well as higher regard for PH among OS, is intriguing. This disparity may reflect current training and clinical expectations of each surgical specialty, with larger emphasis on medical management for surgical compared with orthopedic curricula (www.acgme.org).

While PS and OS respondents perceived that PH involvement did not influence length of stay, pain management, and resource use, single-site studies suggest otherwise.4,8,14 Objective data on the impact of PH involvement on patient and systems outcomes may help elucidate whether this is a perceived or actual lack of impact. Future metrics might include pain scores, patient centered care measures on communication and coordination, patient complaints and/or lawsuits, resource utilization and/or cost, readmission, and medical errors.

This study has several limitations. There is likely a (self) selection bias by surgeons with either strongly positive or negative views of PH involvement. Future studies may target a random sampling of programs rather than a cross-sectional survey of individual providers. Relatively few respondents represented community hospitals, possibly because these facilities are staffed by general OS and general surgeons10 who were not included in this sample.

CONCLUSION

Given the high prevalence of PH involvement in caring for surgical pediatric patients in varied settings, the field of pediatric hospital medicine should support increased PH training and standardized practice around perioperative management, particularly for medically complex patients with increased care coordination needs. Surgical comanagement, including interdisciplinary communication skills, deserves inclusion as a PH core competency and as an entrustable professional activity for pediatric hospital medicine and pediatric graduate medical education programs,15 especially orthopedic surgeries.

Further research on effective and evidence-based pediatric postoperative care and collaboration models will help PH and surgeons to most effectively and respectfully partner to improve care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine Surgical Care Subcommittee, AAP SOHM leadership, and Ms. Alexandra Case.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript to report. This study was supported in part by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (LM, R00HS022198).

1. Task Force for Children’s Surgical Care. Optimal resources for children’s surgical care in the United States. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(3):479-487, 487.e1-4. PubMed

2. Section on Hospital Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics. Guiding principles for pediatric hospital medicine programs. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):782-786. PubMed

3. Freiburg C, James T, Ashikaga T, Moalem J, Cherr G. Strategies to accommodate resident work-hour restrictions: Impact on surgical education. J Surg Educ. 2011;68(5):387-392. PubMed

4. Pressel DM, Rappaport DI, Watson N. Nurses’ assessment of pediatric physicians: Are hospitalists different? J Healthc Manag. 2008;53(1):14-24; discussion 24-25. PubMed

5. Simon TD, Eilert R, Dickinson LM, Kempe A, Benefield E, Berman S. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of spinal fusion surgery patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(1):23-30. PubMed

6. Rosenberg RE, Ardalan K, Wong W, et al. Postoperative spinal fusion care in pediatric patients: Co-management decreases length of stay. Bull Hosp Jt Dis (2013). 2014;72(3):197-203. PubMed

7. Dua K, McAvoy WC, Klaus SA, Rappaport DI, Rosenberg RE, Abzug JM. Hospitalist co-management of pediatric orthopaedic surgical patients at a community hospital. Md Med. 2016;17(1):34-36. PubMed

8. Rohatgi N, Loftus P, Grujic O, Cullen M, Hopkins J, Ahuja N. Surgical comanagement by hospitalists improves patient outcomes: A propensity score analysis. Ann Surg. 2016;264(2):275-282. PubMed

9. Poley S, Ricketts T, Belsky D, Gaul K. Pediatric surgeons: Subspecialists increase faster than generalists. Bull Amer Coll Surg. 2010;95(10):36-39. PubMed

10. Somme S, Bronsert M, Morrato E, Ziegler M. Frequency and variety of inpatient pediatric surgical procedures in the United States. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):e1466-e1472. PubMed

11. Frampton SB, Guastello S, Hoy L, Naylor M, Sheridan S, Johnston-Fleece M, eds. Harnessing Evidence and Experience to Change Culture: A Guiding Framework for Patient and Family Engaged Care. Washington, DC: National Academies of Medicine; 2017.

12. Auger KA, Kenyon CC, Feudtner C, Davis MM. Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: A systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):251-260. PubMed

13. Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the united states. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647-655. PubMed

14. Rappaport DI, Adelizzi-Delany J, Rogers KJ, et al. Outcomes and costs associated with hospitalist comanagement of medically complex children undergoing spinal fusion surgery. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):233-241. PubMed

15. Jerardi K, Meier K, Shaughnessy E. Management of postoperative pediatric patients. MedEdPORTAL. 2015;11:10241. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10241.

1. Task Force for Children’s Surgical Care. Optimal resources for children’s surgical care in the United States. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(3):479-487, 487.e1-4. PubMed

2. Section on Hospital Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics. Guiding principles for pediatric hospital medicine programs. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):782-786. PubMed

3. Freiburg C, James T, Ashikaga T, Moalem J, Cherr G. Strategies to accommodate resident work-hour restrictions: Impact on surgical education. J Surg Educ. 2011;68(5):387-392. PubMed

4. Pressel DM, Rappaport DI, Watson N. Nurses’ assessment of pediatric physicians: Are hospitalists different? J Healthc Manag. 2008;53(1):14-24; discussion 24-25. PubMed

5. Simon TD, Eilert R, Dickinson LM, Kempe A, Benefield E, Berman S. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of spinal fusion surgery patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(1):23-30. PubMed

6. Rosenberg RE, Ardalan K, Wong W, et al. Postoperative spinal fusion care in pediatric patients: Co-management decreases length of stay. Bull Hosp Jt Dis (2013). 2014;72(3):197-203. PubMed

7. Dua K, McAvoy WC, Klaus SA, Rappaport DI, Rosenberg RE, Abzug JM. Hospitalist co-management of pediatric orthopaedic surgical patients at a community hospital. Md Med. 2016;17(1):34-36. PubMed

8. Rohatgi N, Loftus P, Grujic O, Cullen M, Hopkins J, Ahuja N. Surgical comanagement by hospitalists improves patient outcomes: A propensity score analysis. Ann Surg. 2016;264(2):275-282. PubMed

9. Poley S, Ricketts T, Belsky D, Gaul K. Pediatric surgeons: Subspecialists increase faster than generalists. Bull Amer Coll Surg. 2010;95(10):36-39. PubMed

10. Somme S, Bronsert M, Morrato E, Ziegler M. Frequency and variety of inpatient pediatric surgical procedures in the United States. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):e1466-e1472. PubMed

11. Frampton SB, Guastello S, Hoy L, Naylor M, Sheridan S, Johnston-Fleece M, eds. Harnessing Evidence and Experience to Change Culture: A Guiding Framework for Patient and Family Engaged Care. Washington, DC: National Academies of Medicine; 2017.

12. Auger KA, Kenyon CC, Feudtner C, Davis MM. Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: A systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):251-260. PubMed

13. Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the united states. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647-655. PubMed

14. Rappaport DI, Adelizzi-Delany J, Rogers KJ, et al. Outcomes and costs associated with hospitalist comanagement of medically complex children undergoing spinal fusion surgery. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):233-241. PubMed

15. Jerardi K, Meier K, Shaughnessy E. Management of postoperative pediatric patients. MedEdPORTAL. 2015;11:10241. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10241.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Pediatric Surgical Comanagement

According to the 2012 Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) survey, 94% of adult hospitalists and 74% of pediatric hospitalists provide inpatient care to surgical patients.[1] Many of these programs involve comanagement, which the SHM Comanagement Advisory Panel has described as a system of care featuring shared responsibility, authority, and accountability for hospitalized patients with medical and surgical needs.[2] Collaboration between medical and surgical teams for these patients has occurred commonly at some community institutions for decades, but may only be emerging at some tertiary care hospitals. The trend of comanagement appears to be increasing in popularity in adult medicine.[3] As in adult patients, comanagement for children undergoing surgical procedures, particularly those children with special healthcare needs (CSHCNs), has been proposed as a strategy for improving quality and costs. In this review, we will describe structural, quality, and financial implications of pediatric hospitalist comanagement programs, each of which include both potential benefits and drawbacks, as well as discuss a future research agenda for these programs.

ORGANIZATIONAL NEEDS AND STRUCTURE OF COMANAGEMENT PROGRAMS

Patterns of comanagement likely depend on hospital size and structure, both in adult patients[3] and in pediatrics. Children hospitalized for surgical procedures generally fall into 1 of 2 groups: those who are typically healthy and at low risk for complications, and those who are medically complex and at high risk. Healthy children often undergo high‐prevalence, low‐complexity surgical procedures such as tonsillectomy and hernia repairs;[4] these patients are commonly cared for at community hospitals by adult and pediatric surgeons. Whereas medically complex children also undergo these common procedures, they are more likely to be cared for at tertiary care centers and are also more likely to undergo higher‐complexity surgeries such as spinal fusions, hip osteotomies, and ventriculoperitoneal shunt placements.[4] Hospitalist comanagement programs at community hospitals and tertiary care centers may therefore have evolved differently in response to different needs of patients, providers, and organizations,[5] though some institutions may not fall neatly into 1 of these 2 categories.

Comanagement in Community Hospitals

A significant number of pediatric patients are hospitalized each year in community hospitals.[6] As noted above, children undergoing surgery in these settings are generally healthy, and may be cared for by surgeons with varying amounts of pediatric expertise. In this model, the surgeon may frequently be offsite when not in the operating room, necessitating some type of onsite postoperative coverage. In pediatrics, following adult models, this coverage need may be relatively straightforward: surgeons perform the procedure, followed by a medical team assuming postoperative care with surgical consultation. Because of general surgeons' varying experience with children, the American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that patients younger than 14 years or weighing less than 40 kg cared for by providers without routine pediatric experience should have a pediatric‐trained provider involved in their care,[7] though this suggestion does not mandate comanagement.

For children cared for by adult providers who have little experience with areas of pediatric‐specific care such as medication dosing and assessment of deterioration, we believe that involvement of a pediatric provider may impact care in a number of ways. A pediatric hospitalist's availability on the inpatient unit may allow him or her to better manage routine issues such as pain control and intravenous fluids without surgeon input, improving the efficiency of care. A pediatric hospitalist's general pediatric training may allow him or her to more quickly recognize when a child is medically deteriorating, or when transfer to a tertiary care center may be necessary, making care safer. However, no studies have specifically examined these variables. Future research should measure outcomes such as transfers to higher levels of care, medication errors, length of stay (LOS), and complication rates, especially in community hospital settings.

Comanagement in Tertiary Care Referral Centers

At tertiary care referral centers, surgeries in children are most often performed by pediatric surgeons. In these settings, providing routine hospitalist comanagement to all patients may be neither cost‐effective nor feasible. Adult studies have suggested that population‐targeted models can significantly improve several clinical outcomes. For example, in several studies of patients 65 years and older hospitalized with hip fractures, comanagement with a geriatric hospitalist was associated with improved clinical outcomes and shortened LOS.[8, 9, 10, 11, 12]

An analogous group of pediatric patients to the geriatric population may be CSHCNs or children who are medically complex. Several frameworks have been proposed to identify these patients.[13] Many institutions classify medically complex patients as those with complex chronic medical conditions (CCCs).[13, 14, 15] One framework to identify CSHCNs suggested including not only children with CCCs, but also those with (1) substantial service needs and/or family burden; (2) severe functional limitations; and/or (3) high rates of healthcare system utilization, often requiring the care of several subspecialty providers.[16] As the needs of these patients may be quite diverse, pediatric hospitalists may be involved in many aspects of their care, from preoperative evaluation,[17] to establishing protocols for best practices, to communicating with primary care providers, and even seeing patients in postoperative follow‐up clinics. These patients are known to be at high risk for surgical complications, readmissions,[14] medical errors,[18] lapses in communication, and high care costs. In 1 study, comanagement for children with neuromuscular scoliosis hospitalized for spinal fusion surgery has been associated with shorter LOS and less variability in LOS.[19] However, drawbacks of comanagement programs involving CSHCNs may include difficulty with consistent identification of the population who will most benefit from comanagement and higher initial costs of care.[18]

Models of Comanagement and Comanagement Agreements

A comanagement agreement should address 5 major questions: (1) Who is the primary service? (2) Who is the consulting/comanaging service? (3) Are consults as‐needed or automatic? (4) Who writes orders for the patient? (5) Which staffing model will be used for patient care?[20] Although each question above may be answered differently in different systems, the correct comanagement program is a program that aligns most closely with the patient population and care setting.[11, 20]

Several different models exist for hospitalistsurgeon comanagement programs[20, 21] (Table 1). Under the consultation model (model I), hospitalists become involved in the care of surgical patients only when requested to do so by the surgical team. Criteria for requesting this kind of consultation and the extent of responsibility afforded to the medical team are often not clearly defined, and may differ from hospital to hospital or even surgeon to surgeon.[22] Hospitalist involvement with adult patients with postoperative medical complications, which presumably employed this as‐needed model, has been associated with lower mortality and LOS[23]; whether this involvement provides similar benefits in children with postoperative complications has not been explicitly studied.

| Model | Attending Service | Consulting Service | Automatic Consultation | Who Writes Orders? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| I | Surgery | Pediatrics | No | Surgery | Similar to traditional consultation |

| II | Surgery | Pediatrics | Yes | Usually surgery | Basic comanagement, consultant may sign off |

| III | Pediatrics | Surgery | Yes | Usually pediatrics | Basic comanagement, consultant may sign off |

| IV | Combined | N/A | N/A | Each service writes own | True comanagement, no sign‐off from either service permitted |

The remaining models involve compulsory participation by both surgical and medical services. In models II and III, patients may be evaluated preoperatively; those felt to meet specific criteria for high medical complexity are either admitted to a medical service with automatic surgical consultation or admitted to a surgical service with automatic medical consultation. In both cases, writing of orders is handled in the same manner as any consultation model; depending on the service agreement, consulting services may sign off or may be required to be involved until discharge. In model IV, care is fully comanaged by medical and surgical services, with each service having ownership over orders pertaining to their discipline. Ethical concerns about such agreements outlined by the American Medical Association include whether all patients cared for under agreements II to IV will truly benefit from the cost of multispecialty care, and whether informed consent from patients themselves should be required given the cost implications.[24]

Comanagement models also vary with respect to frontline provider staffing. Models may incorporate nurse practitioners, hospitalists, physician assistants, or a combination thereof. These providers may assume a variety of roles, including preoperative patient evaluation, direct care of patients while hospitalized, and/or coordination of inpatient and outpatient postoperative care. Staffing requirements for hospitalists and/or mid‐level providers will differ significantly at different institutions based on surgical volume, patient complexity, and other local factors.

COMANAGEMENT AND QUALITY

Comanagement as a Family‐Centered Initiative

Development of a family‐centered culture of care, including care coordination, lies at the core of pediatric hospital medicine, particularly for CSHCNs.[25, 26] In the outpatient setting, family‐centered care has been associated with improved quality of care for CSHCNs.[27, 28] For families of hospitalized children, issues such as involvement in care and timely information transfer have been identified as high priorities.[29] An important tool for addressing these needs is family‐centered rounds (FCRs), which represent multidisciplinary rounds at the bedside involving families and patients as active shared decision makers in conjunction with the medical team.[30, 31] Although FCRs have not been studied in comanagement arrangements specifically, evidence suggests that this tool improves family centeredness and patient safety in nonsurgical patients,[32] and FCRs can likely have a similar impact on postoperative care.

A pediatric hospitalist comanagement program may impact quality and safety of care in a number of other ways. Hospitalists may offer improved access to clinical information for nurses and families, making care safer. One study of comanagement in adult neurosurgical patients found that access to hospitalists led to improved quality and safety of care as perceived by nurses and other members of the care team.[33] A study in pediatric patients found that nurses overwhelmingly supported having hospitalist involvement in complex children undergoing surgery; the same study found that pediatric hospitalists were particularly noted for their communication skills.[34]

Assessing Clinical Outcomes in Pediatric Hospitalist Comanagement Programs

Most studies evaluating the impact of surgical comanagement programs have focused on global metrics such as LOS, overall complication rates, and resource utilization. In adults, results of these studies have been mixed, suggesting that patient selection may be an important factor.[35] In pediatrics, 2 US studies have assessed these metrics at single centers. Simon et al. found that involvement of a pediatric hospitalist in comanagement of patients undergoing spinal fusion surgery significantly decreased LOS.[19] Rappaport et al. found that patients comanaged by hospitalists had lower utilization of laboratory tests and parenteral nutrition, though initial program costs significantly increased.[36] Studies outside the United States, including a study from Sweden,[37] have suggested that a multidisciplinary approach to children's surgical care, including the presence of pediatric specialists, reduced infection rate and other complications. These studies provide general support for the role of hospitalists in comanagement, although determining which aspects of care are most impacted may be difficult.

Comanagement programs might impact safety and quality negatively as well. Care may be fragmented, leading to provider and family dissatisfaction. Poor communication and multiple handoffs among multidisciplinary team members might interfere with the central role of the nurse in patient care.[38] Comanagement programs might lead to provider disengagement if providers feel that others will assume roles with which they may be unfamiliar or poorly trained.[35] This lack of knowledge may also affect communication with families, leading to conflicting messages among the care team and family frustration. In addition, the impact of comanagement programs on trainees such as residents, both surgical and pediatric, has received limited study.[39] Assessing pediatric comanagement programs' impact on communication, family‐centeredness, and trainees deserves further study.

FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS OF PEDIATRIC COMANAGEMENT PROGRAMS

Children undergoing surgery require significant financial resources for their care. A study of 38 major US children's hospitals found that 3 of the top 10 conditions with the highest annual expenditures were surgical procedures.[4] The most costly procedure was spinal fusion for scoliosis, accounting for an average of $45,000 per admission and $610 million annually. Although a significant portion of these costs represented surgical devices and operating room time, these totals also included the cost of hospital services and in‐hospital complications. CSHCNs more often undergo high‐complexity procedures such as spinal fusions[36] and face greater risk for costly postoperative complications. The financial benefits that come from reductions in outcomes such as LOS and readmissions in this population are potentially large, but may depend on the payment model as described below.

Billing Models in Comanagement Programs

Several billing constructs exist in comanagement models. At many institutions, comanagement billing may resemble that for traditional consultation: the pediatric hospitalist bills for his/her services using standard initial and subsequent consultation billing coding for the child's medical conditions, and may sign off when the hospitalist feels recommendations are complete. Other models may also exist. Model IV comanagement may involve a prearranged financial agreement, in which billing modifiers are used to differentiate surgical care only (modifier 54) and postoperative medical care only (modifier 55). These modifiers, typically used for Medicare patients, indicate a split in a global surgical fee.[40]

The SHM has outlined financial considerations that should be addressed at the time of program inception and updated periodically, including identifying how each party will bill, who bills for which service, and monitoring collection rates and rejected claims.[2] Regardless of billing model, the main focus of comanagement must be quality of care, not financial considerations; situations in which the latter are emphasized at the expense of patient care may be unethical or illegal.[24] Regardless, surgical comanagement programs should seek maximal reimbursement in order to remain viable.

Value of Comanagement for a Healthcare Organization Under Fee‐for‐Service Payment

The value of any comanagement program is highly dependent on both the institution's payor mix and the healthcare organization's overarching goals. From a business perspective, a multidisciplinary approach may be perceived as resource intensive, but formal cost‐effectiveness analyses over time are limited. Theoretically, a traditional payment model involving hospitalist comanagement would be financially beneficial for a healthcare institution by allowing surgeons and surgical trainees more time to operate. However, these savings are difficult to quantify. Despite the fact that most hospitalist programs have no direct financial benefit to the institution, many hospital leaders seem willing to subsidize hospitalist programs based on measures such as patient and referring physician satisfaction with hospitalist care.[41] Postoperative complications, although unfortunate, may be a source of revenue under this model if paid by insurance companies in the usual manner, leading to a misalignment of quality and financial goals. Regardless, whether these programs are considered worthy investments to healthcare organizations will ultimately depend on evolving billing and reimbursement structures; to date, no formal survey of how comanagement programs bill and are reimbursed has been performed.

Value for an Organization in an Accountable Care Organization Model

Although a detailed discussion of accountable care organizations (ACOs) is beyond the scope of this article, stronger incentives in these structures for reducing resource utilization and complication rates may make hospitalist comanagement attractive in an ACO model.[42] ACO program evaluation is expected to be based on such data as patient surveys, documentation of care coordination, and several disease‐specific metrics.[43, 44] Several children's hospital‐based systems and mixed health systems have dedicated significant resources to establishing networks of providers that bridge inpatient and outpatient episodes of surgical care.[27, 28] One adult study has suggested lower costs associated with hospitalist comanagement for geriatric patients with hip fractures.[12] Comanagement programs may help meet quality and value goals, including enhancing care coordination between inpatient and outpatient care, and therefore may prove to be a beneficial investment for institutions. As the healthcare landscape evolves, formal study of the costs and benefits of pediatric comanagement models in ACO‐type care structures will be important.

SETTING A RESEARCH AGENDA

Pediatric hospitalist comanagement programs require vigorous study to evaluate their impact. Potential research targets include not only clinical data such as LOS, perioperative complication rates, readmission rates, and resource utilization, but also data regarding surgeon, nursing, and family satisfaction. These programs should also be evaluated in terms of how they impact trainees, both surgical and pediatric. Because of comanagement programs' complexities, we anticipate that they will impart both positive and negative effects on some of these factors. These programs will also require evaluation over time as they require significant education on the part of staff and families.[36]

In addition to affecting global metrics, pediatric hospitalists may also have a positive impact on surgical care by demonstrating leadership to improve systems of care relevant to surgical patients, including the use of guidelines. The American College of Surgeons' National Surgical Quality Improvement Program has identified 2 priorities that hospitalists may impact: surgical site infection (SSI) and pulmonary complications, which combined comprise greater than half of all 30‐day postoperative complications.[45] Regarding SSI prevention, hospitalist researchers are making valuable contributions to literature surrounding adherence to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America guidelines.[46, 47, 48] Research is ongoing regarding how human and systems factors may impact the effectiveness of these guidelines, but also how reliably these guidelines are implemented.[49] In the area of pulmonary complications, pediatric hospitalists have followed the example of successful initiatives in adult surgery patients by developing and implementing postoperative protocols to prevent pulmonary complications such as postoperative pneumonia.[50] At 1 center, pediatric hospitalists have led efforts to implement a standardized respiratory care pathway for high‐risk orthopedic patients.[51] Evaluation of the effectiveness of such programs is currently ongoing, but early data show similar benefits to those demonstrated in adults.

CONCLUSIONS

Pediatric hospitalist comanagement programs for surgical patients have largely followed the path of adult programs. Limited data suggest that certain clinical outcomes may be improved under comanagement, but patient selection may be important. Although there is significant variety between programs, there exist several common themes, including the importance of clear delineation of roles and a central goal of improved care coordination. Ongoing research will hopefully shed more light on the impact of these programs, especially with regard to patient safety, hospitalist‐led quality‐improvement programs, and financial implications, particularly in different structures of care and reimbursement models.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- 2012 State of Hospital Medicine Report, Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey. Accessed on September 1, 2014.

- Society of Hospital Medicine Co‐Management Advisory Panel. A white paper on a guide to hospitalist/orthopedic surgery co‐management. SHM website. Available at: http://tools.hospitalmedicine.org/Implementation/Co‐ManagementWhitePaper‐final_5‐10‐10.pdf. Accessed on September 25, 2014.

- , , , , . Comanagement of hospitalized surgical patients by medicine physicians in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):363–368.

- , , , et al. Prioritization of comparative effectiveness research topics in hospital pediatrics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1155–1164.

- , . Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of surgical patients: challenges and opportunities. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008;47(2):114–121.

- , . Utilization of pediatric hospitals in New York State. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 pt 1):1068–1071.

- ; Committee on Hospital Care. Physicians' roles in coordinating care of hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):707–709.

- , , , et al. Effects of a hospitalist care model on mortality of elderly patients with hip fractures. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(4):219–225.

- , , , et al. Effects of a hospitalist model on elderly patients with hip fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(7):796–801.

- , , , , , . Outcomes for older patients with hip fractures: the impact of orthopedic and geriatric medicine cocare. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(3):172–178; discussion 179–180.

- , , , . Geriatric co‐management of proximal femur fractures: total quality management and protocol‐driven care result in better outcomes for a frail patient population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1349–1356.

- , , , , , . Comanagement of geriatric patients with hip fractures: a retrospective, controlled, cohort study. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2013;4(1):10–15.

- , , , et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):529–538.

- , , , et al. How well can hospital readmission be predicted in a cohort of hospitalized children? A retrospective, multicenter study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):286–293.

- , , . Pediatric hospital medicine and children with medical complexity: past, present, and future. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2012;42(5):113–119.

- , , , et al. A new definition of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 1998;102(1 pt 1):137–140.

- , , , , . Pediatric hospitalist preoperative evaluation of children with neuromuscular scoliosis. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(12):684–688.

- , , , , . Hospital admission medication reconciliation in medically complex children: an observational study. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(4):250–255.

- , , , , , . Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of spinal fusion surgery patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(1):23–30.

- , . Principles of comanagement and the geriatric fracture center. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(2):183–189.

- . How best to design surgical comanagement services for pediatric surgical patients? Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):242–243.

- , , , , , . Effects of provider characteristics on care coordination under comanagement. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):508–513.

- , , , . Potential role of comanagement in “rescue” of surgical patients. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(9):e333–e339.

- American Medical Association. 2008 report of the Council on Medical Service, policy sunset report for 1998 AMA socioeconomic policies. CMS Report 4, A‐08. Available at: http://www.ama‐assn.org/resources/doc/cms/a‐08cms4.pdf. Accessed on September 1, 2014.

- Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient‐and Family‐Centered Care. Patient‐ and family‐centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):394–404.

- Council on Children with Disabilities and Medical Home Implementation Project Advisory Committee. Patient‐ and family‐centered care coordination: a framework for integrating care for children and youth across multiple systems. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):e1451–e1460.

- , , , , , . Care coordination for CSHCN: associations with family‐provider relations and family/child outcomes. Pediatrics. 2009;124(suppl 4):S428–S434.

- , , , et al. Evidence for family‐centered care for children with special health care needs: a systematic review. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(2):136–143.

- , , . Parents' priorities and satisfaction with acute pediatric care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(2):127–131.

- . Family‐centered rounds. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61(4):663–670.

- , , , et al. Family‐centered rounds on pediatric wards: a PRIS network survey of US and Canadian hospitalists. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):37–43.

- , , , , ; PIPS Group. Scoping review and approach to appraisal of interventions intended to involve patients in patient safety. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2010;15(suppl 1):17–25.

- , , , et al. Comanagement of surgical patients between neurosurgeons and hospitalists. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):2004–2010.

- , , . Nurses' assessment of pediatric physicians: are hospitalists different? J Healthc Manag Am Coll Healthc Exec. 2008;53(1):14–24; discussion 24–25.

- . Just because you can, doesn't mean that you should: a call for the rational application of hospitalist comanagement. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):398–402.

- , , , et al. Outcomes and costs associated with hospitalist comanagement of medically complex children undergoing spinal fusion surgery. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):233–241.

- , , . Outcome of major spinal deformity surgery in high‐risk patients: comparison between two departments. Evid Based Spine Care J. 2010;1(3):11–18.

- , , , , , . Meeting the complex needs of the health care team: identification of nurse‐team communication practices perceived to enhance patient outcomes. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(1):15–28.

- , , , . A pediatric residency experience with surgical comanagement. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(2):144–148.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. MLN matters. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach‐and‐Education/Medicare‐Learning‐Network‐MLN/MLNMattersArticles/Downloads/MM7872.pdf. Accessed on September 1,2014.

- , , ; Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics. Assessing the value of pediatric hospitalist programs: the perspective of hospital leaders. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(3):192–196.

- . Launching accountable care organizations—the proposed rule for the Medicare Shared Savings Program. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):e32.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and Pediatricians: Evaluation and Engagement. Available at: http://www.aap.org/en‐us/professional‐resources/practice‐support/Pages/Accountable‐Care‐Organizations‐and‐Pediatricians‐Evaluation‐and‐Engagement.aspx. Accessed on September 25, 2014.

- , , , , . Delivery system characteristics and their association with quality and costs of care: implications for accountable care organizations [published online ahead of print February 21, 2014]. Health Care Manage Rev. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000014.

- , , , et al. Pediatric American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: feasibility of a novel, prospective assessment of surgical outcomes. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46(1):115–121.

- , , , et al. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(4):247–278. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/guidelines/SSI_1999.pdf. Accessed on September 1, 2014.

- , , , et al. Building consensus: development of a Best Practice Guideline (BPG) for surgical site infection (SSI) prevention in high‐risk pediatric spine surgery. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33(5):471–478.

- , , , et al. Perioperative antibiotic use for spinal surgery procedures in US children's hospitals. Spine. 2013;38(7):609–616. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/education/Conferences/Forum2013/Pages/Scientific‐Symposium.aspx. Accessed on September 26, 2014.

- , , , , , , , , , , , . A human factors intervention to improve post‐operative antibiotic timing and prevent surgical site infection. Paper presented at: Institute for Healthcare Improvement Scientific Symposium; 2013; Orlando, FL. Abstract.

- , , , , . I COUGH: reducing postoperative pulmonary complications with a multidisciplinary patient care program. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(8):740–745. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/education/Conferences/Forum2013/Pages/Scientific‐Symposium.aspx. Accessed on September 26, 2014.

- , , , , , , , . Early postoperative respiratory care improves outcomes, adds value for hospitalized pediatric orthopedic patients. Poster presented at: Institute for Healthcare Improvement Scientific Symposium; 2013; Orlando, FL. Abstract.

According to the 2012 Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) survey, 94% of adult hospitalists and 74% of pediatric hospitalists provide inpatient care to surgical patients.[1] Many of these programs involve comanagement, which the SHM Comanagement Advisory Panel has described as a system of care featuring shared responsibility, authority, and accountability for hospitalized patients with medical and surgical needs.[2] Collaboration between medical and surgical teams for these patients has occurred commonly at some community institutions for decades, but may only be emerging at some tertiary care hospitals. The trend of comanagement appears to be increasing in popularity in adult medicine.[3] As in adult patients, comanagement for children undergoing surgical procedures, particularly those children with special healthcare needs (CSHCNs), has been proposed as a strategy for improving quality and costs. In this review, we will describe structural, quality, and financial implications of pediatric hospitalist comanagement programs, each of which include both potential benefits and drawbacks, as well as discuss a future research agenda for these programs.

ORGANIZATIONAL NEEDS AND STRUCTURE OF COMANAGEMENT PROGRAMS

Patterns of comanagement likely depend on hospital size and structure, both in adult patients[3] and in pediatrics. Children hospitalized for surgical procedures generally fall into 1 of 2 groups: those who are typically healthy and at low risk for complications, and those who are medically complex and at high risk. Healthy children often undergo high‐prevalence, low‐complexity surgical procedures such as tonsillectomy and hernia repairs;[4] these patients are commonly cared for at community hospitals by adult and pediatric surgeons. Whereas medically complex children also undergo these common procedures, they are more likely to be cared for at tertiary care centers and are also more likely to undergo higher‐complexity surgeries such as spinal fusions, hip osteotomies, and ventriculoperitoneal shunt placements.[4] Hospitalist comanagement programs at community hospitals and tertiary care centers may therefore have evolved differently in response to different needs of patients, providers, and organizations,[5] though some institutions may not fall neatly into 1 of these 2 categories.

Comanagement in Community Hospitals

A significant number of pediatric patients are hospitalized each year in community hospitals.[6] As noted above, children undergoing surgery in these settings are generally healthy, and may be cared for by surgeons with varying amounts of pediatric expertise. In this model, the surgeon may frequently be offsite when not in the operating room, necessitating some type of onsite postoperative coverage. In pediatrics, following adult models, this coverage need may be relatively straightforward: surgeons perform the procedure, followed by a medical team assuming postoperative care with surgical consultation. Because of general surgeons' varying experience with children, the American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that patients younger than 14 years or weighing less than 40 kg cared for by providers without routine pediatric experience should have a pediatric‐trained provider involved in their care,[7] though this suggestion does not mandate comanagement.

For children cared for by adult providers who have little experience with areas of pediatric‐specific care such as medication dosing and assessment of deterioration, we believe that involvement of a pediatric provider may impact care in a number of ways. A pediatric hospitalist's availability on the inpatient unit may allow him or her to better manage routine issues such as pain control and intravenous fluids without surgeon input, improving the efficiency of care. A pediatric hospitalist's general pediatric training may allow him or her to more quickly recognize when a child is medically deteriorating, or when transfer to a tertiary care center may be necessary, making care safer. However, no studies have specifically examined these variables. Future research should measure outcomes such as transfers to higher levels of care, medication errors, length of stay (LOS), and complication rates, especially in community hospital settings.

Comanagement in Tertiary Care Referral Centers

At tertiary care referral centers, surgeries in children are most often performed by pediatric surgeons. In these settings, providing routine hospitalist comanagement to all patients may be neither cost‐effective nor feasible. Adult studies have suggested that population‐targeted models can significantly improve several clinical outcomes. For example, in several studies of patients 65 years and older hospitalized with hip fractures, comanagement with a geriatric hospitalist was associated with improved clinical outcomes and shortened LOS.[8, 9, 10, 11, 12]

An analogous group of pediatric patients to the geriatric population may be CSHCNs or children who are medically complex. Several frameworks have been proposed to identify these patients.[13] Many institutions classify medically complex patients as those with complex chronic medical conditions (CCCs).[13, 14, 15] One framework to identify CSHCNs suggested including not only children with CCCs, but also those with (1) substantial service needs and/or family burden; (2) severe functional limitations; and/or (3) high rates of healthcare system utilization, often requiring the care of several subspecialty providers.[16] As the needs of these patients may be quite diverse, pediatric hospitalists may be involved in many aspects of their care, from preoperative evaluation,[17] to establishing protocols for best practices, to communicating with primary care providers, and even seeing patients in postoperative follow‐up clinics. These patients are known to be at high risk for surgical complications, readmissions,[14] medical errors,[18] lapses in communication, and high care costs. In 1 study, comanagement for children with neuromuscular scoliosis hospitalized for spinal fusion surgery has been associated with shorter LOS and less variability in LOS.[19] However, drawbacks of comanagement programs involving CSHCNs may include difficulty with consistent identification of the population who will most benefit from comanagement and higher initial costs of care.[18]

Models of Comanagement and Comanagement Agreements

A comanagement agreement should address 5 major questions: (1) Who is the primary service? (2) Who is the consulting/comanaging service? (3) Are consults as‐needed or automatic? (4) Who writes orders for the patient? (5) Which staffing model will be used for patient care?[20] Although each question above may be answered differently in different systems, the correct comanagement program is a program that aligns most closely with the patient population and care setting.[11, 20]

Several different models exist for hospitalistsurgeon comanagement programs[20, 21] (Table 1). Under the consultation model (model I), hospitalists become involved in the care of surgical patients only when requested to do so by the surgical team. Criteria for requesting this kind of consultation and the extent of responsibility afforded to the medical team are often not clearly defined, and may differ from hospital to hospital or even surgeon to surgeon.[22] Hospitalist involvement with adult patients with postoperative medical complications, which presumably employed this as‐needed model, has been associated with lower mortality and LOS[23]; whether this involvement provides similar benefits in children with postoperative complications has not been explicitly studied.

| Model | Attending Service | Consulting Service | Automatic Consultation | Who Writes Orders? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| I | Surgery | Pediatrics | No | Surgery | Similar to traditional consultation |

| II | Surgery | Pediatrics | Yes | Usually surgery | Basic comanagement, consultant may sign off |

| III | Pediatrics | Surgery | Yes | Usually pediatrics | Basic comanagement, consultant may sign off |

| IV | Combined | N/A | N/A | Each service writes own | True comanagement, no sign‐off from either service permitted |

The remaining models involve compulsory participation by both surgical and medical services. In models II and III, patients may be evaluated preoperatively; those felt to meet specific criteria for high medical complexity are either admitted to a medical service with automatic surgical consultation or admitted to a surgical service with automatic medical consultation. In both cases, writing of orders is handled in the same manner as any consultation model; depending on the service agreement, consulting services may sign off or may be required to be involved until discharge. In model IV, care is fully comanaged by medical and surgical services, with each service having ownership over orders pertaining to their discipline. Ethical concerns about such agreements outlined by the American Medical Association include whether all patients cared for under agreements II to IV will truly benefit from the cost of multispecialty care, and whether informed consent from patients themselves should be required given the cost implications.[24]