User login

How to manage a patient presenting with syncope

Case

A 38-year-old construction worker without significant medical history presents following witnessed syncope at her job, after standing for at least 2 hours on a particularly warm day. She reported an episode of syncope under similar circumstances 2 months prior. With each episode, she experienced “tunneling” of peripheral vision, then loss of consciousness without palpitations or incontinence. Her physical exam, vital signs (including orthostatic blood pressures), labs, and ECG were unremarkable.

Brief overview

The American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and Heart Rhythm Society guidelines define syncope as “a symptom that presents with an abrupt, transient, complete loss of consciousness, associated with inability to maintain postural tone, with rapid and spontaneous recovery” with cerebral hypoperfusion as the presumed mechanism.1 Furthermore, “there should not be clinical features of other nonsyncope causes of loss of consciousness, such as seizure, antecedent head trauma, or apparent loss of consciousness (that is, pseudosyncope).”1

A careful history revolving around the patient’s behavior prior to, during, and following the event, a thorough past medical history, and a review of current medications are essential. Potential obstacles in obtaining details of the event include lack of witnesses, patient’s inability to recall the experience, and inaccurate description of convulsive syncope as a “seizure” by bystanders.2

Overview of data

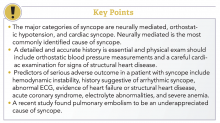

Obtaining a detailed history is crucial to understanding both the etiology of the syncopal event and determining which patients are at high risk for adverse outcomes. The etiology of syncope can be determined by history alone in 26% of patients younger than 65 years.3 Data on the prevalence of syncope by cause varies widely. As a general rule, in younger patients, especially those under 40 years of age, neurally mediated syncope is most common. As patients age, orthostatic hypotension and cardiac causes (including arrhythmias and structural diseases) occur more frequently, though neurally mediated syncope is still the most common.

Many of these predictors, however, would raise the clinical suspicion of most hospitalists for adverse outcomes in their hospitalized patients independent of the presence or absence of syncope. In fact, a meta-analysis has concluded that “None of the evaluated prediction tools (SFSR, EGSYS) performed better than clinical judgment in identifying serious outcomes during emergency department stay, and at 10 and 30 days after syncope.”6

Once the patient is hospitalized, further evaluation should be based on a careful history and physical examination. Standard evaluation also includes careful review of medications, an ECG to exclude findings suggestive of arrhythmias as well as structural or coronary artery disease, and orthostatic blood pressure measurements.1 Additional tests should be considered as deemed appropriate. For example, in patients over 40 years of age without history of carotid artery disease or stroke and in whom no carotid artery bruit is appreciated, a carotid sinus massage may be considered. The correct technique is to massage the sinus on the right then left, each for 5 seconds in both supine and standing positions with continuous heart rate and frequent blood pressure monitoring. Reproduction of syncope, especially concurrent with a cardiac pause of greater than 3 seconds and a systolic blood pressure drop of greater than 50 mmHg, is considered a positive test. Tilt-table testing should be considered in those for whom neurally mediated syncope is suspected but not confirmed, or in patients who might benefit from further elucidation of their prodromal symptoms.

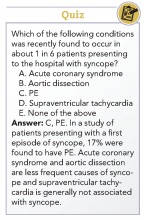

Of note, a study recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests that the prevalence of PE in patients (median age, 80 years) presenting with a first episode of syncope was 17%, a rate that is substantially higher than historically presumed.8 Although the prevalence of PE was highest among patients presenting with syncope of unclear origin (25%), nearly 13% of patients with other explanations for syncope also had PE.

Application of data

Bottom Line

Dr. Roberts, Dr. Krason, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

1. Shen W-K et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Aug 1;70(5):e39-e110.

2. Sheldon R. How to differentiate syncope from seizure. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):377-85.

3. Del Rosso A et al. Relation of clinical presentation of syncope to the age of patients. Am J Cardiol. 2005 Nov 15;96(10):1431-5.

4. Blanc JJ. Syncope: Definition, epidemiology, and classification. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):341-5.

5. Matthews IG et al. Syncope in the older person. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):411-21.

6. Costantino G et al. Syncope risk stratification tools vs clinical judgment: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2014 Nov;127(11):1126.e13-25.

7. Chiu DT et al. Are echocardiography, telemetry, ambulatory electrocardiography monitoring, and cardiac enzymes in emergency department patients presenting with syncope useful tests? A preliminary investigation. J Emerg Med. 2014;47:113-8.

8. Prandoni P et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism among patients hospitalized for syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016 Oct;375(20):1524-31.

9. Sheldon RS et al. Standardized approaches to the investigation of syncope: Canadian Cardiovascular Society position paper. Can J Cardiol. 2011 Mar-Apr;27(2):246-253.

10. Moya A et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009): the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2009 Nov;30(21):2631-71.

Additional reading

1. Brignole M, Hamdan MH. New concepts in the assessment of syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 May; 59(18):1583-91.

2. Rosanio S et al. Syncope in adults: systematic review and proposal of a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. Int J Cardiol. 2013 Jan;162(3):149-57.

Case

A 38-year-old construction worker without significant medical history presents following witnessed syncope at her job, after standing for at least 2 hours on a particularly warm day. She reported an episode of syncope under similar circumstances 2 months prior. With each episode, she experienced “tunneling” of peripheral vision, then loss of consciousness without palpitations or incontinence. Her physical exam, vital signs (including orthostatic blood pressures), labs, and ECG were unremarkable.

Brief overview

The American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and Heart Rhythm Society guidelines define syncope as “a symptom that presents with an abrupt, transient, complete loss of consciousness, associated with inability to maintain postural tone, with rapid and spontaneous recovery” with cerebral hypoperfusion as the presumed mechanism.1 Furthermore, “there should not be clinical features of other nonsyncope causes of loss of consciousness, such as seizure, antecedent head trauma, or apparent loss of consciousness (that is, pseudosyncope).”1

A careful history revolving around the patient’s behavior prior to, during, and following the event, a thorough past medical history, and a review of current medications are essential. Potential obstacles in obtaining details of the event include lack of witnesses, patient’s inability to recall the experience, and inaccurate description of convulsive syncope as a “seizure” by bystanders.2

Overview of data

Obtaining a detailed history is crucial to understanding both the etiology of the syncopal event and determining which patients are at high risk for adverse outcomes. The etiology of syncope can be determined by history alone in 26% of patients younger than 65 years.3 Data on the prevalence of syncope by cause varies widely. As a general rule, in younger patients, especially those under 40 years of age, neurally mediated syncope is most common. As patients age, orthostatic hypotension and cardiac causes (including arrhythmias and structural diseases) occur more frequently, though neurally mediated syncope is still the most common.

Many of these predictors, however, would raise the clinical suspicion of most hospitalists for adverse outcomes in their hospitalized patients independent of the presence or absence of syncope. In fact, a meta-analysis has concluded that “None of the evaluated prediction tools (SFSR, EGSYS) performed better than clinical judgment in identifying serious outcomes during emergency department stay, and at 10 and 30 days after syncope.”6

Once the patient is hospitalized, further evaluation should be based on a careful history and physical examination. Standard evaluation also includes careful review of medications, an ECG to exclude findings suggestive of arrhythmias as well as structural or coronary artery disease, and orthostatic blood pressure measurements.1 Additional tests should be considered as deemed appropriate. For example, in patients over 40 years of age without history of carotid artery disease or stroke and in whom no carotid artery bruit is appreciated, a carotid sinus massage may be considered. The correct technique is to massage the sinus on the right then left, each for 5 seconds in both supine and standing positions with continuous heart rate and frequent blood pressure monitoring. Reproduction of syncope, especially concurrent with a cardiac pause of greater than 3 seconds and a systolic blood pressure drop of greater than 50 mmHg, is considered a positive test. Tilt-table testing should be considered in those for whom neurally mediated syncope is suspected but not confirmed, or in patients who might benefit from further elucidation of their prodromal symptoms.

Of note, a study recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests that the prevalence of PE in patients (median age, 80 years) presenting with a first episode of syncope was 17%, a rate that is substantially higher than historically presumed.8 Although the prevalence of PE was highest among patients presenting with syncope of unclear origin (25%), nearly 13% of patients with other explanations for syncope also had PE.

Application of data

Bottom Line

Dr. Roberts, Dr. Krason, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

1. Shen W-K et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Aug 1;70(5):e39-e110.

2. Sheldon R. How to differentiate syncope from seizure. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):377-85.

3. Del Rosso A et al. Relation of clinical presentation of syncope to the age of patients. Am J Cardiol. 2005 Nov 15;96(10):1431-5.

4. Blanc JJ. Syncope: Definition, epidemiology, and classification. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):341-5.

5. Matthews IG et al. Syncope in the older person. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):411-21.

6. Costantino G et al. Syncope risk stratification tools vs clinical judgment: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2014 Nov;127(11):1126.e13-25.

7. Chiu DT et al. Are echocardiography, telemetry, ambulatory electrocardiography monitoring, and cardiac enzymes in emergency department patients presenting with syncope useful tests? A preliminary investigation. J Emerg Med. 2014;47:113-8.

8. Prandoni P et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism among patients hospitalized for syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016 Oct;375(20):1524-31.

9. Sheldon RS et al. Standardized approaches to the investigation of syncope: Canadian Cardiovascular Society position paper. Can J Cardiol. 2011 Mar-Apr;27(2):246-253.

10. Moya A et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009): the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2009 Nov;30(21):2631-71.

Additional reading

1. Brignole M, Hamdan MH. New concepts in the assessment of syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 May; 59(18):1583-91.

2. Rosanio S et al. Syncope in adults: systematic review and proposal of a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. Int J Cardiol. 2013 Jan;162(3):149-57.

Case

A 38-year-old construction worker without significant medical history presents following witnessed syncope at her job, after standing for at least 2 hours on a particularly warm day. She reported an episode of syncope under similar circumstances 2 months prior. With each episode, she experienced “tunneling” of peripheral vision, then loss of consciousness without palpitations or incontinence. Her physical exam, vital signs (including orthostatic blood pressures), labs, and ECG were unremarkable.

Brief overview

The American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and Heart Rhythm Society guidelines define syncope as “a symptom that presents with an abrupt, transient, complete loss of consciousness, associated with inability to maintain postural tone, with rapid and spontaneous recovery” with cerebral hypoperfusion as the presumed mechanism.1 Furthermore, “there should not be clinical features of other nonsyncope causes of loss of consciousness, such as seizure, antecedent head trauma, or apparent loss of consciousness (that is, pseudosyncope).”1

A careful history revolving around the patient’s behavior prior to, during, and following the event, a thorough past medical history, and a review of current medications are essential. Potential obstacles in obtaining details of the event include lack of witnesses, patient’s inability to recall the experience, and inaccurate description of convulsive syncope as a “seizure” by bystanders.2

Overview of data

Obtaining a detailed history is crucial to understanding both the etiology of the syncopal event and determining which patients are at high risk for adverse outcomes. The etiology of syncope can be determined by history alone in 26% of patients younger than 65 years.3 Data on the prevalence of syncope by cause varies widely. As a general rule, in younger patients, especially those under 40 years of age, neurally mediated syncope is most common. As patients age, orthostatic hypotension and cardiac causes (including arrhythmias and structural diseases) occur more frequently, though neurally mediated syncope is still the most common.

Many of these predictors, however, would raise the clinical suspicion of most hospitalists for adverse outcomes in their hospitalized patients independent of the presence or absence of syncope. In fact, a meta-analysis has concluded that “None of the evaluated prediction tools (SFSR, EGSYS) performed better than clinical judgment in identifying serious outcomes during emergency department stay, and at 10 and 30 days after syncope.”6

Once the patient is hospitalized, further evaluation should be based on a careful history and physical examination. Standard evaluation also includes careful review of medications, an ECG to exclude findings suggestive of arrhythmias as well as structural or coronary artery disease, and orthostatic blood pressure measurements.1 Additional tests should be considered as deemed appropriate. For example, in patients over 40 years of age without history of carotid artery disease or stroke and in whom no carotid artery bruit is appreciated, a carotid sinus massage may be considered. The correct technique is to massage the sinus on the right then left, each for 5 seconds in both supine and standing positions with continuous heart rate and frequent blood pressure monitoring. Reproduction of syncope, especially concurrent with a cardiac pause of greater than 3 seconds and a systolic blood pressure drop of greater than 50 mmHg, is considered a positive test. Tilt-table testing should be considered in those for whom neurally mediated syncope is suspected but not confirmed, or in patients who might benefit from further elucidation of their prodromal symptoms.

Of note, a study recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests that the prevalence of PE in patients (median age, 80 years) presenting with a first episode of syncope was 17%, a rate that is substantially higher than historically presumed.8 Although the prevalence of PE was highest among patients presenting with syncope of unclear origin (25%), nearly 13% of patients with other explanations for syncope also had PE.

Application of data

Bottom Line

Dr. Roberts, Dr. Krason, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

1. Shen W-K et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Aug 1;70(5):e39-e110.

2. Sheldon R. How to differentiate syncope from seizure. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):377-85.

3. Del Rosso A et al. Relation of clinical presentation of syncope to the age of patients. Am J Cardiol. 2005 Nov 15;96(10):1431-5.

4. Blanc JJ. Syncope: Definition, epidemiology, and classification. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):341-5.

5. Matthews IG et al. Syncope in the older person. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):411-21.

6. Costantino G et al. Syncope risk stratification tools vs clinical judgment: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2014 Nov;127(11):1126.e13-25.

7. Chiu DT et al. Are echocardiography, telemetry, ambulatory electrocardiography monitoring, and cardiac enzymes in emergency department patients presenting with syncope useful tests? A preliminary investigation. J Emerg Med. 2014;47:113-8.

8. Prandoni P et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism among patients hospitalized for syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016 Oct;375(20):1524-31.

9. Sheldon RS et al. Standardized approaches to the investigation of syncope: Canadian Cardiovascular Society position paper. Can J Cardiol. 2011 Mar-Apr;27(2):246-253.

10. Moya A et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009): the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2009 Nov;30(21):2631-71.

Additional reading

1. Brignole M, Hamdan MH. New concepts in the assessment of syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 May; 59(18):1583-91.

2. Rosanio S et al. Syncope in adults: systematic review and proposal of a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. Int J Cardiol. 2013 Jan;162(3):149-57.