User login

Impact of Clinical Specialty on Attitudes Regarding Overuse of Inpatient Laboratory Testing

Routine laboratory testing in hospitalized patients is common, with a high prevalence of unnecessary tests that do not contribute to patient management.1 Excessive laboratory testing of hospitalized patients can contribute to anemia2 and may cause patient discomfort, additional unnecessary testing resulting from false positive results, and higher out-of-pocket patient costs. Excessive testing can impact hospital budgets both directly (though direct costs are often low) and indirectly through costly downstream services and prolonged hospital stay.3 As part of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely initiative, several professional societies have recommended against routine laboratory testing of hospitalized adult patients.4

Excessive inpatient laboratory testing has been documented mostly among adult internal medicine (IM) patients with studies of drivers of unnecessary testing and efforts to reduce it conducted in IM settings.5, 6 Attitudes toward other issues related to testing overuse differ by specialty7 and are likely to similarly vary with regard to unnecessary laboratory testing. Understanding differences in attitudes by clinical specialty is critical for framing tailored approaches to reducing inappropriate care.

We performed a cross-sectional survey of a diverse group of hospital clinicians to describe attitudes and beliefs regarding laboratory testing and its overuse across clinical specialties (eg, medical, surgical, and pediatric). We hypothesized that attitudes toward the need for testing would differ across specialties.

METHODS

Survey Development and Administration

The study was conducted at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, a tertiary academic cancer hospital in New York City. The 12-item survey was adopted from a previously administered but not formally validated survey (Online-only Appendix).5,8 The survey was pilot tested with 4 physicians, 3 NPs, 2 PAs, and 3 RNs and edited for content and clarity. All staff providers including NPs, PAs, RNs, and resident, fellow, and attending MDs working in the hospital during the 2-week survey period (November 2-15, 2015) were eligible to participate and were emailed a link to the survey. The email invitation was resent 3 times during the survey period. Participants who completed the survey received a coupon for a free coffee. The study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board and exempted from ongoing oversight.

Measures

Demographic items included clinical specialty, provider type, and gender (Online-only Appendix). The remaining survey questions included the following categories:

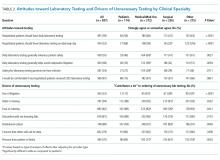

1. Attitudes toward laboratory testing were evaluated by 3 items about accepted norms for lab testing and 2 items about fears (Table 2). Responses to these items used a 4-point Likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree).

2. Drivers contributing to unnecessary testing were evaluated by presenting a list of possible contributing factors (Table 2). Responses to these items used a 3-point Likert scale (contributes a lot, contributes a little, or does not contribute).

Analysis

We used univariate statistics to describe demographics and survey responses. We used the chi-square statistic to evaluate differences in attitudes and drivers by clinical specialty. We dichotomized responses regarding attitudes toward lab testing (“strongly agree” and “somewhat agree” vs. “somewhat disagree” and “strongly disagree.”) and beliefs regarding contributing drivers (“contributes a lot” vs all others). We grouped clinical specialty into medical/med-oncology, surgical, pediatric, and other (gynecological, critical care, and other).

We used logistic regression to explore the associations between attitudes/drivers and clinical specialty after adjusting for provider type, and report the overall P-value. We used pediatrics as the reference group to assess direct comparisons with each of the other specialties. We performed analyses with SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and considered P < .05 to be significant.

RESULTS

Among 1580 eligible participants, 837 (53%) completed surveys. Attending MD response rates ranged between 61% (surgical) to 86% (pediatric); rates were 59% for all trainees, 72% for PAs and 46% for RNs and NPs combined. Given privacy concerns, we were unable to collect detailed response rate information or any information about nonrespondents. The demographics are shown in Table 1.

Attitudes toward Laboratory Testing

The majority of respondents agreed that hospitalized patients should get daily labs (59%), testing on the discharge day (52%), and that daily testing generally enhances safety (55%; Table 2). Fewer pediatric and surgical clinicians endorsed that laboratory testing should be done daily (56% and 47% respectively) and enhances patient safety (46% and 47%). These differences were significant after adjusting for provider type. In addition, fewer pediatric providers endorsed the statement that daily laboratory testing helps avoid malpractice litigation. Overall, 68% of respondents agreed they would be comfortable with less testing.

Drivers Contributing to Unnecessary Laboratory Testing

The strongest drivers of unnecessary testing were seen as habit (94% responding “contributes a lot”) and institutional culture (89% responding “contributes a lot”; Table 2). After adjusting for provider type, significant differences were observed based on clinical specialty. In particular, pediatric specialists were less likely to endorse fear of litigation (P < .001) and more likely to endorse pressure from patient/family (P = .0003) compared to all other specialties (Table 2, odd ratios not shown).

DISCUSSION

Overuse of laboratory testing in hospitalized patients is widely recognized in IM and likely to be prevalent in other clinical specialties. Our study elucidated differences in attitudes toward unnecessary testing and self-identified drivers across specialties in a diverse group of clinical providers at an academic cancer center. We found differences based on clinical specialty, with those caring for pediatric and surgical patients less likely than others to believe that testing should be done daily and that daily testing enhances patient safety. Furthermore, comfort with less testing was highest among pediatric specialists. Habit and institutional culture were recognized broadly as the strongest drivers of laboratory testing overuse.

Our findings regarding differences based on clinical specialty are novel. Respondents caring for pediatric patients generally placed lower value on testing, and IM clinicians were the most likely to endorse daily testing and to believe that it enhances patient safety and helps avoid malpractice litigation. The difference between adult and pediatric clinicians is surprising given the fundamental similarities between these specialties.9 Although some resource use studies have described differences across specialties, none has examined differences in laboratory testing or examined the practice patterns of clinicians who are not physicians across specialties.10 Prior studies have documented the impact of training location on practice11,12, suggesting the importance of the local training culture.13 As physician personalities vary across clinical specialties14 it is likely that culture varies as well. Specialty-specific cultures are likely to strongly influence attitudes and practice patterns and warrant further exploration.

Clinicians in our sample identified drivers of unnecessary laboratory testing that were consistent with other studies, most frequently endorsing habit, followed by culture, discomfort with not knowing, and concern that someone will ask for the results.5,15 Previous studies have focused on IM and have not included nonphysicians or compared attitudes across specialties. We found that the largest differences in drivers by specialty were related to malpractice concerns and the perception of pressure from patients or families. The low endorsement of defensive medicine among clinicians serving pediatric populations may imply that interventions to reduce unnecessary care in hospitalized children may not need to address malpractice fear. In contrast, clinicians from pediatrics identified family pressure as a greater driver of unnecessary testing. Efforts to reduce unnecessary laboratory testing in pediatrics will need to address parent expectations.

Our findings have implications for efforts to reduce unnecessary testing. Culture, identified as a key driver of testing, reflects leadership priorities, institutional history, and other factors and is difficult to specifically target. Habit, the other most-endorsed driver, is a more promising target for quality improvement interventions, particularly those addressing care processes (eg, electronic ordering). Discomfort with not knowing and fear of being asked are drivers that might be influenced by better communication about information expectations by supervising physicians and hospital administration. Lastly, education about the potential harms of excessive testing may facilitate more targeted efforts to reduce testing overuse.

Our study has important limitations. The cancer focus of the center may have influenced provider attitudes and practices. Attitudes may differ at community centers, though important differences regarding routine laboratory testing are unlikely. Second, although our sample was large, our response rate was modest at 53% and as low as 46% among RNs and NPs and we have no information regarding nonresponders. This response rate, though, was comparable to response rates seen in other large surveys.5,15 In addition, our results reflect clinician self-report; perceptions of necessity and the true need for testing may vary across specialties and the true subconscious drivers of behavior may differ. However, differences across specialties are likely to be valid even if there are other factors at play. Self assessment of unnecessary testing may also underestimate prevalence of the problem. Finally, our findings related to drivers of unnecessary testing are descriptive rather than quantitative given the lack of validated scales.

In conclusion, we evaluated attitudes toward routine laboratory testing in hospitalized patients in clinicians across specialties and found important differences. These findings speak to the diversity of cultures of medical care even within a single institution and point to the importance of studying attitudes about overused services across clinical specialties. In particular, as medical fields beyond IM increasingly recognize the importance of reducing medical overuse both in and out of the hospital, our findings highlight the importance of elucidating specialty-specific attitudes to optimize interventions to address unnecessary testing.

Disclosures

Mr. Husain, Ms. Gennarelli, Ms. White4, Mr. Masciale, MA5, and Dr. Roman, MD, have nothing to disclose. The work of Dr. Roman and Dr. Korenstein on this project was supported, in part, by a Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (P30 CA008748)

1. Zhi M, Ding EL, Theisen-Toupal J, Whelan J, Arnaout R. The landscape of inappropriate laboratory testing: a 15-year meta-analysis. PloS One. 2013;8(11):e78962. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078962. PubMed

2. Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Ebidia A, Detsky AS, Choudhry NK. Do blood tests cause anemia in hospitalized patients? The effect of diagnostic phlebotomy on hemoglobin and hematocrit levels. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):520-524. DOI: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0094.x. PubMed

3. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152 PubMed

4. Choosing wisely. http://www.choosingwisely.org/resources/. Accessed November 21, 2017.

5. Sedrak MS, Patel MS, Ziemba JB, et al. Residents’ self-report on why they order perceived unnecessary inpatient laboratory tests. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):869-872. DOI: 10.1002/jhm.2645. PubMed

6. Thakkar RN, Kim D, Knight AM, Riedel S, Vaidya D, Wright SM. Impact of an educational intervention on the frequency of daily blood test orders for hospitalized patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;143(3):393-397. DOI: 10.1309/AJCPJS4EEM7UAUBV. PubMed

7. Sheeler RD, Mundell T, Hurst SA, et al. Self-reported rationing behavior among US physicians: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(12):1444-1451. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-016-3756-5. PubMed

8. Roman BR, Yang A, Masciale J, Korenstein D. Association of attitudes regarding overuse of inpatient laboratory testing with health care provider type. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1205-1207. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1634. PubMed

9. Schatz IJ, Realini JP, Charney E. Family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics as partners in the education of generalists. Acad Med. 1996;71(1):35-39. PubMed

10. Johnson RE, Freeborn DK, Mullooly JP. Physicians’ use of laboratory, radiology, and drugs in a prepaid group practice HMO. Health Serv Res. 1985;20(5):525-547. PubMed

11. Chen C, Petterson S, Phillips R, Bazemore A, Mullan F. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. Dec 10, 2014;312(22):2385-2393. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2014.15973. PubMed

12. Sirovich BE, Lipner RS, Johnston M, Holmboe ES. The association between residency training and internists’ ability to practice conservatively. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1640-1648. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3337. PubMed

13. Smith CD, Korenstein D. Harnessing the power of peer pressure to reduce health care waste and improve clinical outcomes. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(3):311-312. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2015.136 PubMed

14. Vaidya NA, Sierles FS, Raida MD, Fakhoury FJ, Przybeck TR, Cloninger CR. Relationship between specialty choice and medical student temperament and character assessed with Cloninger Inventory. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16(2):150-156. DOI: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1602_6 PubMed

15. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609-2617. DOI: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2609 PubMed

Routine laboratory testing in hospitalized patients is common, with a high prevalence of unnecessary tests that do not contribute to patient management.1 Excessive laboratory testing of hospitalized patients can contribute to anemia2 and may cause patient discomfort, additional unnecessary testing resulting from false positive results, and higher out-of-pocket patient costs. Excessive testing can impact hospital budgets both directly (though direct costs are often low) and indirectly through costly downstream services and prolonged hospital stay.3 As part of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely initiative, several professional societies have recommended against routine laboratory testing of hospitalized adult patients.4

Excessive inpatient laboratory testing has been documented mostly among adult internal medicine (IM) patients with studies of drivers of unnecessary testing and efforts to reduce it conducted in IM settings.5, 6 Attitudes toward other issues related to testing overuse differ by specialty7 and are likely to similarly vary with regard to unnecessary laboratory testing. Understanding differences in attitudes by clinical specialty is critical for framing tailored approaches to reducing inappropriate care.

We performed a cross-sectional survey of a diverse group of hospital clinicians to describe attitudes and beliefs regarding laboratory testing and its overuse across clinical specialties (eg, medical, surgical, and pediatric). We hypothesized that attitudes toward the need for testing would differ across specialties.

METHODS

Survey Development and Administration

The study was conducted at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, a tertiary academic cancer hospital in New York City. The 12-item survey was adopted from a previously administered but not formally validated survey (Online-only Appendix).5,8 The survey was pilot tested with 4 physicians, 3 NPs, 2 PAs, and 3 RNs and edited for content and clarity. All staff providers including NPs, PAs, RNs, and resident, fellow, and attending MDs working in the hospital during the 2-week survey period (November 2-15, 2015) were eligible to participate and were emailed a link to the survey. The email invitation was resent 3 times during the survey period. Participants who completed the survey received a coupon for a free coffee. The study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board and exempted from ongoing oversight.

Measures

Demographic items included clinical specialty, provider type, and gender (Online-only Appendix). The remaining survey questions included the following categories:

1. Attitudes toward laboratory testing were evaluated by 3 items about accepted norms for lab testing and 2 items about fears (Table 2). Responses to these items used a 4-point Likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree).

2. Drivers contributing to unnecessary testing were evaluated by presenting a list of possible contributing factors (Table 2). Responses to these items used a 3-point Likert scale (contributes a lot, contributes a little, or does not contribute).

Analysis

We used univariate statistics to describe demographics and survey responses. We used the chi-square statistic to evaluate differences in attitudes and drivers by clinical specialty. We dichotomized responses regarding attitudes toward lab testing (“strongly agree” and “somewhat agree” vs. “somewhat disagree” and “strongly disagree.”) and beliefs regarding contributing drivers (“contributes a lot” vs all others). We grouped clinical specialty into medical/med-oncology, surgical, pediatric, and other (gynecological, critical care, and other).

We used logistic regression to explore the associations between attitudes/drivers and clinical specialty after adjusting for provider type, and report the overall P-value. We used pediatrics as the reference group to assess direct comparisons with each of the other specialties. We performed analyses with SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and considered P < .05 to be significant.

RESULTS

Among 1580 eligible participants, 837 (53%) completed surveys. Attending MD response rates ranged between 61% (surgical) to 86% (pediatric); rates were 59% for all trainees, 72% for PAs and 46% for RNs and NPs combined. Given privacy concerns, we were unable to collect detailed response rate information or any information about nonrespondents. The demographics are shown in Table 1.

Attitudes toward Laboratory Testing

The majority of respondents agreed that hospitalized patients should get daily labs (59%), testing on the discharge day (52%), and that daily testing generally enhances safety (55%; Table 2). Fewer pediatric and surgical clinicians endorsed that laboratory testing should be done daily (56% and 47% respectively) and enhances patient safety (46% and 47%). These differences were significant after adjusting for provider type. In addition, fewer pediatric providers endorsed the statement that daily laboratory testing helps avoid malpractice litigation. Overall, 68% of respondents agreed they would be comfortable with less testing.

Drivers Contributing to Unnecessary Laboratory Testing

The strongest drivers of unnecessary testing were seen as habit (94% responding “contributes a lot”) and institutional culture (89% responding “contributes a lot”; Table 2). After adjusting for provider type, significant differences were observed based on clinical specialty. In particular, pediatric specialists were less likely to endorse fear of litigation (P < .001) and more likely to endorse pressure from patient/family (P = .0003) compared to all other specialties (Table 2, odd ratios not shown).

DISCUSSION

Overuse of laboratory testing in hospitalized patients is widely recognized in IM and likely to be prevalent in other clinical specialties. Our study elucidated differences in attitudes toward unnecessary testing and self-identified drivers across specialties in a diverse group of clinical providers at an academic cancer center. We found differences based on clinical specialty, with those caring for pediatric and surgical patients less likely than others to believe that testing should be done daily and that daily testing enhances patient safety. Furthermore, comfort with less testing was highest among pediatric specialists. Habit and institutional culture were recognized broadly as the strongest drivers of laboratory testing overuse.

Our findings regarding differences based on clinical specialty are novel. Respondents caring for pediatric patients generally placed lower value on testing, and IM clinicians were the most likely to endorse daily testing and to believe that it enhances patient safety and helps avoid malpractice litigation. The difference between adult and pediatric clinicians is surprising given the fundamental similarities between these specialties.9 Although some resource use studies have described differences across specialties, none has examined differences in laboratory testing or examined the practice patterns of clinicians who are not physicians across specialties.10 Prior studies have documented the impact of training location on practice11,12, suggesting the importance of the local training culture.13 As physician personalities vary across clinical specialties14 it is likely that culture varies as well. Specialty-specific cultures are likely to strongly influence attitudes and practice patterns and warrant further exploration.

Clinicians in our sample identified drivers of unnecessary laboratory testing that were consistent with other studies, most frequently endorsing habit, followed by culture, discomfort with not knowing, and concern that someone will ask for the results.5,15 Previous studies have focused on IM and have not included nonphysicians or compared attitudes across specialties. We found that the largest differences in drivers by specialty were related to malpractice concerns and the perception of pressure from patients or families. The low endorsement of defensive medicine among clinicians serving pediatric populations may imply that interventions to reduce unnecessary care in hospitalized children may not need to address malpractice fear. In contrast, clinicians from pediatrics identified family pressure as a greater driver of unnecessary testing. Efforts to reduce unnecessary laboratory testing in pediatrics will need to address parent expectations.

Our findings have implications for efforts to reduce unnecessary testing. Culture, identified as a key driver of testing, reflects leadership priorities, institutional history, and other factors and is difficult to specifically target. Habit, the other most-endorsed driver, is a more promising target for quality improvement interventions, particularly those addressing care processes (eg, electronic ordering). Discomfort with not knowing and fear of being asked are drivers that might be influenced by better communication about information expectations by supervising physicians and hospital administration. Lastly, education about the potential harms of excessive testing may facilitate more targeted efforts to reduce testing overuse.

Our study has important limitations. The cancer focus of the center may have influenced provider attitudes and practices. Attitudes may differ at community centers, though important differences regarding routine laboratory testing are unlikely. Second, although our sample was large, our response rate was modest at 53% and as low as 46% among RNs and NPs and we have no information regarding nonresponders. This response rate, though, was comparable to response rates seen in other large surveys.5,15 In addition, our results reflect clinician self-report; perceptions of necessity and the true need for testing may vary across specialties and the true subconscious drivers of behavior may differ. However, differences across specialties are likely to be valid even if there are other factors at play. Self assessment of unnecessary testing may also underestimate prevalence of the problem. Finally, our findings related to drivers of unnecessary testing are descriptive rather than quantitative given the lack of validated scales.

In conclusion, we evaluated attitudes toward routine laboratory testing in hospitalized patients in clinicians across specialties and found important differences. These findings speak to the diversity of cultures of medical care even within a single institution and point to the importance of studying attitudes about overused services across clinical specialties. In particular, as medical fields beyond IM increasingly recognize the importance of reducing medical overuse both in and out of the hospital, our findings highlight the importance of elucidating specialty-specific attitudes to optimize interventions to address unnecessary testing.

Disclosures

Mr. Husain, Ms. Gennarelli, Ms. White4, Mr. Masciale, MA5, and Dr. Roman, MD, have nothing to disclose. The work of Dr. Roman and Dr. Korenstein on this project was supported, in part, by a Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (P30 CA008748)

Routine laboratory testing in hospitalized patients is common, with a high prevalence of unnecessary tests that do not contribute to patient management.1 Excessive laboratory testing of hospitalized patients can contribute to anemia2 and may cause patient discomfort, additional unnecessary testing resulting from false positive results, and higher out-of-pocket patient costs. Excessive testing can impact hospital budgets both directly (though direct costs are often low) and indirectly through costly downstream services and prolonged hospital stay.3 As part of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely initiative, several professional societies have recommended against routine laboratory testing of hospitalized adult patients.4

Excessive inpatient laboratory testing has been documented mostly among adult internal medicine (IM) patients with studies of drivers of unnecessary testing and efforts to reduce it conducted in IM settings.5, 6 Attitudes toward other issues related to testing overuse differ by specialty7 and are likely to similarly vary with regard to unnecessary laboratory testing. Understanding differences in attitudes by clinical specialty is critical for framing tailored approaches to reducing inappropriate care.

We performed a cross-sectional survey of a diverse group of hospital clinicians to describe attitudes and beliefs regarding laboratory testing and its overuse across clinical specialties (eg, medical, surgical, and pediatric). We hypothesized that attitudes toward the need for testing would differ across specialties.

METHODS

Survey Development and Administration

The study was conducted at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, a tertiary academic cancer hospital in New York City. The 12-item survey was adopted from a previously administered but not formally validated survey (Online-only Appendix).5,8 The survey was pilot tested with 4 physicians, 3 NPs, 2 PAs, and 3 RNs and edited for content and clarity. All staff providers including NPs, PAs, RNs, and resident, fellow, and attending MDs working in the hospital during the 2-week survey period (November 2-15, 2015) were eligible to participate and were emailed a link to the survey. The email invitation was resent 3 times during the survey period. Participants who completed the survey received a coupon for a free coffee. The study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board and exempted from ongoing oversight.

Measures

Demographic items included clinical specialty, provider type, and gender (Online-only Appendix). The remaining survey questions included the following categories:

1. Attitudes toward laboratory testing were evaluated by 3 items about accepted norms for lab testing and 2 items about fears (Table 2). Responses to these items used a 4-point Likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree).

2. Drivers contributing to unnecessary testing were evaluated by presenting a list of possible contributing factors (Table 2). Responses to these items used a 3-point Likert scale (contributes a lot, contributes a little, or does not contribute).

Analysis

We used univariate statistics to describe demographics and survey responses. We used the chi-square statistic to evaluate differences in attitudes and drivers by clinical specialty. We dichotomized responses regarding attitudes toward lab testing (“strongly agree” and “somewhat agree” vs. “somewhat disagree” and “strongly disagree.”) and beliefs regarding contributing drivers (“contributes a lot” vs all others). We grouped clinical specialty into medical/med-oncology, surgical, pediatric, and other (gynecological, critical care, and other).

We used logistic regression to explore the associations between attitudes/drivers and clinical specialty after adjusting for provider type, and report the overall P-value. We used pediatrics as the reference group to assess direct comparisons with each of the other specialties. We performed analyses with SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and considered P < .05 to be significant.

RESULTS

Among 1580 eligible participants, 837 (53%) completed surveys. Attending MD response rates ranged between 61% (surgical) to 86% (pediatric); rates were 59% for all trainees, 72% for PAs and 46% for RNs and NPs combined. Given privacy concerns, we were unable to collect detailed response rate information or any information about nonrespondents. The demographics are shown in Table 1.

Attitudes toward Laboratory Testing

The majority of respondents agreed that hospitalized patients should get daily labs (59%), testing on the discharge day (52%), and that daily testing generally enhances safety (55%; Table 2). Fewer pediatric and surgical clinicians endorsed that laboratory testing should be done daily (56% and 47% respectively) and enhances patient safety (46% and 47%). These differences were significant after adjusting for provider type. In addition, fewer pediatric providers endorsed the statement that daily laboratory testing helps avoid malpractice litigation. Overall, 68% of respondents agreed they would be comfortable with less testing.

Drivers Contributing to Unnecessary Laboratory Testing

The strongest drivers of unnecessary testing were seen as habit (94% responding “contributes a lot”) and institutional culture (89% responding “contributes a lot”; Table 2). After adjusting for provider type, significant differences were observed based on clinical specialty. In particular, pediatric specialists were less likely to endorse fear of litigation (P < .001) and more likely to endorse pressure from patient/family (P = .0003) compared to all other specialties (Table 2, odd ratios not shown).

DISCUSSION

Overuse of laboratory testing in hospitalized patients is widely recognized in IM and likely to be prevalent in other clinical specialties. Our study elucidated differences in attitudes toward unnecessary testing and self-identified drivers across specialties in a diverse group of clinical providers at an academic cancer center. We found differences based on clinical specialty, with those caring for pediatric and surgical patients less likely than others to believe that testing should be done daily and that daily testing enhances patient safety. Furthermore, comfort with less testing was highest among pediatric specialists. Habit and institutional culture were recognized broadly as the strongest drivers of laboratory testing overuse.

Our findings regarding differences based on clinical specialty are novel. Respondents caring for pediatric patients generally placed lower value on testing, and IM clinicians were the most likely to endorse daily testing and to believe that it enhances patient safety and helps avoid malpractice litigation. The difference between adult and pediatric clinicians is surprising given the fundamental similarities between these specialties.9 Although some resource use studies have described differences across specialties, none has examined differences in laboratory testing or examined the practice patterns of clinicians who are not physicians across specialties.10 Prior studies have documented the impact of training location on practice11,12, suggesting the importance of the local training culture.13 As physician personalities vary across clinical specialties14 it is likely that culture varies as well. Specialty-specific cultures are likely to strongly influence attitudes and practice patterns and warrant further exploration.

Clinicians in our sample identified drivers of unnecessary laboratory testing that were consistent with other studies, most frequently endorsing habit, followed by culture, discomfort with not knowing, and concern that someone will ask for the results.5,15 Previous studies have focused on IM and have not included nonphysicians or compared attitudes across specialties. We found that the largest differences in drivers by specialty were related to malpractice concerns and the perception of pressure from patients or families. The low endorsement of defensive medicine among clinicians serving pediatric populations may imply that interventions to reduce unnecessary care in hospitalized children may not need to address malpractice fear. In contrast, clinicians from pediatrics identified family pressure as a greater driver of unnecessary testing. Efforts to reduce unnecessary laboratory testing in pediatrics will need to address parent expectations.

Our findings have implications for efforts to reduce unnecessary testing. Culture, identified as a key driver of testing, reflects leadership priorities, institutional history, and other factors and is difficult to specifically target. Habit, the other most-endorsed driver, is a more promising target for quality improvement interventions, particularly those addressing care processes (eg, electronic ordering). Discomfort with not knowing and fear of being asked are drivers that might be influenced by better communication about information expectations by supervising physicians and hospital administration. Lastly, education about the potential harms of excessive testing may facilitate more targeted efforts to reduce testing overuse.

Our study has important limitations. The cancer focus of the center may have influenced provider attitudes and practices. Attitudes may differ at community centers, though important differences regarding routine laboratory testing are unlikely. Second, although our sample was large, our response rate was modest at 53% and as low as 46% among RNs and NPs and we have no information regarding nonresponders. This response rate, though, was comparable to response rates seen in other large surveys.5,15 In addition, our results reflect clinician self-report; perceptions of necessity and the true need for testing may vary across specialties and the true subconscious drivers of behavior may differ. However, differences across specialties are likely to be valid even if there are other factors at play. Self assessment of unnecessary testing may also underestimate prevalence of the problem. Finally, our findings related to drivers of unnecessary testing are descriptive rather than quantitative given the lack of validated scales.

In conclusion, we evaluated attitudes toward routine laboratory testing in hospitalized patients in clinicians across specialties and found important differences. These findings speak to the diversity of cultures of medical care even within a single institution and point to the importance of studying attitudes about overused services across clinical specialties. In particular, as medical fields beyond IM increasingly recognize the importance of reducing medical overuse both in and out of the hospital, our findings highlight the importance of elucidating specialty-specific attitudes to optimize interventions to address unnecessary testing.

Disclosures

Mr. Husain, Ms. Gennarelli, Ms. White4, Mr. Masciale, MA5, and Dr. Roman, MD, have nothing to disclose. The work of Dr. Roman and Dr. Korenstein on this project was supported, in part, by a Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (P30 CA008748)

1. Zhi M, Ding EL, Theisen-Toupal J, Whelan J, Arnaout R. The landscape of inappropriate laboratory testing: a 15-year meta-analysis. PloS One. 2013;8(11):e78962. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078962. PubMed

2. Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Ebidia A, Detsky AS, Choudhry NK. Do blood tests cause anemia in hospitalized patients? The effect of diagnostic phlebotomy on hemoglobin and hematocrit levels. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):520-524. DOI: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0094.x. PubMed

3. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152 PubMed

4. Choosing wisely. http://www.choosingwisely.org/resources/. Accessed November 21, 2017.

5. Sedrak MS, Patel MS, Ziemba JB, et al. Residents’ self-report on why they order perceived unnecessary inpatient laboratory tests. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):869-872. DOI: 10.1002/jhm.2645. PubMed

6. Thakkar RN, Kim D, Knight AM, Riedel S, Vaidya D, Wright SM. Impact of an educational intervention on the frequency of daily blood test orders for hospitalized patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;143(3):393-397. DOI: 10.1309/AJCPJS4EEM7UAUBV. PubMed

7. Sheeler RD, Mundell T, Hurst SA, et al. Self-reported rationing behavior among US physicians: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(12):1444-1451. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-016-3756-5. PubMed

8. Roman BR, Yang A, Masciale J, Korenstein D. Association of attitudes regarding overuse of inpatient laboratory testing with health care provider type. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1205-1207. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1634. PubMed

9. Schatz IJ, Realini JP, Charney E. Family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics as partners in the education of generalists. Acad Med. 1996;71(1):35-39. PubMed

10. Johnson RE, Freeborn DK, Mullooly JP. Physicians’ use of laboratory, radiology, and drugs in a prepaid group practice HMO. Health Serv Res. 1985;20(5):525-547. PubMed

11. Chen C, Petterson S, Phillips R, Bazemore A, Mullan F. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. Dec 10, 2014;312(22):2385-2393. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2014.15973. PubMed

12. Sirovich BE, Lipner RS, Johnston M, Holmboe ES. The association between residency training and internists’ ability to practice conservatively. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1640-1648. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3337. PubMed

13. Smith CD, Korenstein D. Harnessing the power of peer pressure to reduce health care waste and improve clinical outcomes. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(3):311-312. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2015.136 PubMed

14. Vaidya NA, Sierles FS, Raida MD, Fakhoury FJ, Przybeck TR, Cloninger CR. Relationship between specialty choice and medical student temperament and character assessed with Cloninger Inventory. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16(2):150-156. DOI: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1602_6 PubMed

15. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609-2617. DOI: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2609 PubMed

1. Zhi M, Ding EL, Theisen-Toupal J, Whelan J, Arnaout R. The landscape of inappropriate laboratory testing: a 15-year meta-analysis. PloS One. 2013;8(11):e78962. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078962. PubMed

2. Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Ebidia A, Detsky AS, Choudhry NK. Do blood tests cause anemia in hospitalized patients? The effect of diagnostic phlebotomy on hemoglobin and hematocrit levels. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):520-524. DOI: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0094.x. PubMed

3. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152 PubMed

4. Choosing wisely. http://www.choosingwisely.org/resources/. Accessed November 21, 2017.

5. Sedrak MS, Patel MS, Ziemba JB, et al. Residents’ self-report on why they order perceived unnecessary inpatient laboratory tests. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):869-872. DOI: 10.1002/jhm.2645. PubMed

6. Thakkar RN, Kim D, Knight AM, Riedel S, Vaidya D, Wright SM. Impact of an educational intervention on the frequency of daily blood test orders for hospitalized patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;143(3):393-397. DOI: 10.1309/AJCPJS4EEM7UAUBV. PubMed

7. Sheeler RD, Mundell T, Hurst SA, et al. Self-reported rationing behavior among US physicians: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(12):1444-1451. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-016-3756-5. PubMed

8. Roman BR, Yang A, Masciale J, Korenstein D. Association of attitudes regarding overuse of inpatient laboratory testing with health care provider type. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1205-1207. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1634. PubMed

9. Schatz IJ, Realini JP, Charney E. Family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics as partners in the education of generalists. Acad Med. 1996;71(1):35-39. PubMed

10. Johnson RE, Freeborn DK, Mullooly JP. Physicians’ use of laboratory, radiology, and drugs in a prepaid group practice HMO. Health Serv Res. 1985;20(5):525-547. PubMed

11. Chen C, Petterson S, Phillips R, Bazemore A, Mullan F. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. Dec 10, 2014;312(22):2385-2393. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2014.15973. PubMed

12. Sirovich BE, Lipner RS, Johnston M, Holmboe ES. The association between residency training and internists’ ability to practice conservatively. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1640-1648. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3337. PubMed

13. Smith CD, Korenstein D. Harnessing the power of peer pressure to reduce health care waste and improve clinical outcomes. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(3):311-312. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2015.136 PubMed

14. Vaidya NA, Sierles FS, Raida MD, Fakhoury FJ, Przybeck TR, Cloninger CR. Relationship between specialty choice and medical student temperament and character assessed with Cloninger Inventory. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16(2):150-156. DOI: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1602_6 PubMed

15. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609-2617. DOI: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2609 PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

A practical framework for understanding and reducing medical overuse: Conceptualizing overuse through the patient-clinician interaction

Medical services overuse is the provision of healthcare services for which there is no medical basis or for which harms equal or exceed benefits.1 This overuse drives poor-quality care and unnecessary cost.2,3 The high prevalence of overuse is recognized by patients,4 clinicians,5 and policymakers.6 Initiatives to reduce overuse have targeted physicians,7 the public,8 and medical educators9,10 but have had limited impact.11,12 Few studies have addressed methods for reducing overuse, and de-implementation of nonbeneficial practices has proved challenging.1,13,14 Models for reducing overuse are only theoretical15 or are focused on administrative decisions.16,17 We think a practical framework is needed. We used an iterative process, informed by expert opinion and discussion, to design such a framework.

METHODS

The authors, who have expertise in overuse, value, medical education, evidence-based medicine, and implementation science, reviewed related conceptual frameworks18 and evidence regarding drivers of overuse. We organized these drivers into domains to create a draft framework, which we presented at Preventing Overdiagnosis 2015, a meeting of clinicians, patients, and policymakers interested in overuse. We incorporated feedback from meeting attendees to modify framework domains, and we performed structured searches (using key words in Pubmed) to explore, and estimate the strength of, evidence supporting items within each domain. We rated supporting evidence as strong (studies found a clear correlation between a factor and overuse), moderate (evidence suggests such a correlation or demonstrates a correlation between a particular factor and utilization but not overuse per se), weak (only indirect evidence exists), or absent (no studies identified evaluating a particular factor). All authors reached consensus on ratings.

Framework Principles and Evidence

Patient-centered definition of overuse. During framework development, defining clinical appropriateness emerged as the primary challenge to identifying and reducing overuse. Although some care generally is appropriate based on strong evidence of benefit, and some is inappropriate given a clear lack of benefit or harm, much care is of unclear or variable benefit. Practice guidelines can help identify overuse, but their utility may be limited by lack of evidence in specific clinical situations,19 and their recommendations may apply poorly to an individual patient. This presents challenges to using guidelines to identify and reduce overuse.

Despite limitations, the scope of overuse has been estimated by applying broad, often guideline-based, criteria for care appropriateness to administrative data.20 Unfortunately, these estimates provide little direction to clinicians and patients partnering to make usage decisions. During framework development, we identified the importance of a patient-level, patient-specific definition of overuse. This approach reinforces the importance of meeting patient needs while standardizing treatments to reduce overuse. A patient-centered approach may also assist professional societies and advocacy groups in developing actionable campaigns and may uncover evidence gaps.

Centrality of patient-clinician interaction. During framework development, the patient–clinician interaction emerged as the nexus through which drivers of overuse exert influence. The centrality of this interaction has been demonstrated in studies of the relationship between care continuity and overuse21 or utilization,22,23 by evidence that communication and patient–clinician relationships affect utilization,24 and by the observation that clinician training in shared decision-making reduces overuse.25 A patient-centered framework assumes that, at least in the weighing of clinically reasonable options, a patient-centered approach optimizes outcomes for that patient.

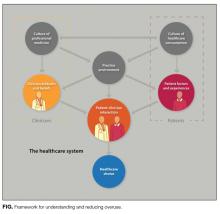

Incorporating drivers of overuse. We incorporated drivers of overuse into domains and related them to the patient–clinician interaction.26 Domains included the culture of healthcare consumption, patient factors and experiences, the practice environment, the culture of professional medicine, and clinician attitudes and beliefs.

We characterized the evidence illustrating how drivers within each domain influence healthcare use. The evidence for each domain is listed in Table 1.

RESULTS

The final framework is shown in the Figure. Within the healthcare system, patients are influenced by the culture of healthcare consumption, which varies within and among countries.27 Clinicians are influenced by the culture of medical care, which varies by practice setting,28 and by their training environment.29 Both clinicians and patients are influenced by the practice environment and by personal experiences. Ultimately, clinical decisions occur within the specific patient–clinician interaction.24 Table 1 lists each domain’s components, likely impact on overuse, and estimated strength of supporting evidence. Interventions can be conceptualized within appropriate domains or through the interaction between patient and clinician.

DISCUSSION

We developed a novel and practical conceptual framework for characterizing drivers of overuse and potential intervention points. To our knowledge, this is the first framework incorporating a patient-specific approach to overuse and emphasizing the patient–clinician interaction. Key strengths of framework development are inclusion of a range of perspectives and characterization of the evidence within each domain. Limitations include lack of a formal systematic review and broad, qualitative assessments of evidence strength. However, we believe this framework provides an important conceptual foundation for the study of overuse and interventions to reduce overuse.

Framework Applications

This framework, which highlights the many drivers of overuse, can facilitate understanding of overuse and help conceptualize change, prioritize research goals, and inform specific interventions. For policymakers, the framework can inform efforts to reduce overuse by emphasizing the need for complex interventions and by clarifying the likely impact of interventions targeting specific domains. Similarly, for clinicians and quality improvement professionals, the framework can ground root cause analyses of overuse-related problems and inform allocation of limited resources. Finally, the relatively weak evidence on the role of most acknowledged drivers of overuse suggests an important research agenda. Specifically, several pressing needs have been identified: defining relevant physician and patient cultural factors, investigating interventions to impact culture, defining practice environment features that optimize care appropriateness, and describing specific patient–clinician interaction practices that minimize overuse while providing needed care.

Targeting Interventions

Domains within the framework are influenced by different types of interventions, and different stakeholders may target different domains. For example:

- The culture of healthcare consumption may be influenced through public education (eg, Choosing Wisely® patient resources)30-32 and public health campaigns.

- The practice environment may be influenced by initiatives to align clinician incentives,33 team care,34 electronic health record interventions,35 and improved access.36

- Clinician attitudes and beliefs may be influenced by audit and feedback,37-40 reflection,41 role modeling,42 and education.43-45

- Patient attitudes and beliefs may be influenced by education, access to price and quality information, and increased engagement in care.46,47

- For clinicians, the patient–clinician interaction can be improved through training in communication and shared decision-making,25 through access to information (eg, costs) that can be easily shared with patients,48,49 and through novel visit structures (eg, scribes).50

- On the patient side, this interaction can be optimized with improved access (eg, through telemedicine)51,52 or with patient empowerment during hospitalization.

- The culture of medicine is difficult to influence. Change likely will occur through:

○ Regulatory interventions (eg, Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative of Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation).

○ Educational initiatives (eg, high-value care curricula of Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine/American College of Physicians53).

○ Medical journal features (eg, “Less Is More” in JAMA Internal Medicine54 and “Things We Do for No Reason” in Journal of Hospital Medicine).

○ Professional organizations (eg, Choosing Wisely®).

As organizations implement quality improvement initiatives to reduce overuse of services, the framework can be used to target interventions to relevant domains. For example, a hospital leader who wants to reduce opioid prescribing may use the framework to identify the factors that encourage prescribing in each domain—poor understanding of pain treatment (a clinician factor), desire for early discharge encouraging overly aggressive pain management (an environmental factor), patient demand for opioids combined with poor understanding of harms (patient factors), and poor communication regarding pain (a patient–clinician interaction factor). Although not all relevant factors can be addressed, their classification by domain facilitates intervention, in this case perhaps leading to a focus on clinician and patient education on opioids and development of a practical communication tool that targets 3 domains. Table 2 lists ways in which the framework informs approaches to this and other overused services in the hospital setting. Note that some drivers can be acknowledged without identifying targeted interventions.

Moving Forward

Through a multi-stakeholder iterative process, we developed a practical framework for understanding medical overuse and interventions to reduce it. Centered on the patient–clinician interaction, this framework explains overuse as the product of medical and patient culture, the practice environment and incentives, and other clinician and patient factors. Ultimately, care is implemented during the patient–clinician interaction, though few interventions to reduce overuse have focused on that domain.

Conceptualizing overuse through the patient–clinician interaction maintains focus on patients while promoting population health that is both better and lower in cost. This framework can guide interventions to reduce overuse in important parts of the healthcare system while ensuring the final goal of high-quality individualized patient care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Valerie Pocus for helping with the artistic design of Framework. An early version of Framework was presented at the 2015 Preventing Overdiagnosis meeting in Bethesda, Maryland.

Disclosures

Dr. Morgan received research support from the VA Health Services Research (CRE 12-307), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (K08- HS18111). Dr. Leppin’s work was supported by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Korenstein’s work on this paper was supported by a Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (award number P30 CA008748). Dr. Morgan provided a self-developed lecture in a 3M-sponsored series on hospital epidemiology and has received honoraria for serving as a book and journal editor for Springer Publishing. Dr. Smith is employed by the American College of Physicians and owns stock in Merck, where her husband is employed. The other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

1. Morgan DJ, Brownlee S, Leppin AL, et al. Setting a research agenda for medical overuse. BMJ. 2015;351:h4534. PubMed

2. Hood VL, Weinberger SE. High value, cost-conscious care: an international imperative. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23(6):495-498. PubMed

3. Korenstein D, Falk R, Howell EA, Bishop T, Keyhani S. Overuse of health care services in the United States: an understudied problem. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(2):171-178. PubMed

4. How SKH, Shih A, Lau J, Schoen C. Public Views on U.S. Health System Organization: A Call for New Directions. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/data-briefs/2008/aug/public-views-on-u-s--health-system-organization--a-call-for-new-directions. Published August 1, 2008. Accessed December 11, 2015.

5. Sirovich BE, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. Too little? Too much? Primary care physicians’ views on US health care: a brief report. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(17):1582-1585. PubMed

6. Joint Commission, American Medical Association–Convened Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. Proceedings From the National Summit on Overuse. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/National_Summit_Overuse.pdf. Published September 24, 2012. Accessed July 8, 2016.

7. Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing Wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801-1802. PubMed

8. Wolfson D, Santa J, Slass L. Engaging physicians and consumers in conversations about treatment overuse and waste: a short history of the Choosing Wisely campaign. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):990-995. PubMed

9. Smith CD, Levinson WS. A commitment to high-value care education from the internal medicine community. Ann Int Med. 2015;162(9):639-640. PubMed

10. Korenstein D, Kale M, Levinson W. Teaching value in academic environments: shifting the ivory tower. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1671-1672. PubMed

11. Kale MS, Bishop TF, Federman AD, Keyhani S. Trends in the overuse of ambulatory health care services in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(2):142-148. PubMed

12. Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, et al. Early trends among seven recommendations from the Choosing Wisely campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. PubMed

13. Prasad V, Ioannidis JP. Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implement Sci. 2014;9:1. PubMed

14. Ubel PA, Asch DA. Creating value in health by understanding and overcoming resistance to de-innovation. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(2):239-244. PubMed

15. Powell AA, Bloomfield HE, Burgess DJ, Wilt TJ, Partin MR. A conceptual framework for understanding and reducing overuse by primary care providers. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(5):451-472. PubMed

16. Nassery N, Segal JB, Chang E, Bridges JF. Systematic overuse of healthcare services: a conceptual model. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2015;13(1):1-6. PubMed

17. Segal JB, Nassery N, Chang HY, Chang E, Chan K, Bridges JF. An index for measuring overuse of health care resources with Medicare claims. Med Care. 2015;53(3):230-236. PubMed

18. Reschovsky JD, Rich EC, Lake TK. Factors contributing to variations in physicians’ use of evidence at the point of care: a conceptual model. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(suppl 3):S555-S561. PubMed

19. Feinstein AR, Horwitz RI. Problems in the “evidence” of “evidence-based medicine.” Am J Med. 1997;103(6):529-535. PubMed

20. Makarov DV, Soulos PR, Gold HT, et al. Regional-level correlations in inappropriate imaging rates for prostate and breast cancers: potential implications for the Choosing Wisely campaign. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(2):185-194. PubMed

21. Romano MJ, Segal JB, Pollack CE. The association between continuity of care and the overuse of medical procedures. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1148-1154. PubMed

22. Bayliss EA, Ellis JL, Shoup JA, Zeng C, McQuillan DB, Steiner JF. Effect of continuity of care on hospital utilization for seniors with multiple medical conditions in an integrated health care system. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):123-129. PubMed

23. Chaiyachati KH, Gordon K, Long T, et al. Continuity in a VA patient-centered medical home reduces emergency department visits. PloS One. 2014;9(5):e96356. PubMed

24. Underhill ML, Kiviniemi MT. The association of perceived provider-patient communication and relationship quality with colorectal cancer screening. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39(5):555-563. PubMed

25. Legare F, Labrecque M, Cauchon M, Castel J, Turcotte S, Grimshaw J. Training family physicians in shared decision-making to reduce the overuse of antibiotics in acute respiratory infections: a cluster randomized trial. CMAJ. 2012;184(13):E726-E734. PubMed

26. PerryUndum Research/Communication; for ABIM Foundation. Unnecessary Tests and Procedures in the Health Care System: What Physicians Say About the Problem, the Causes, and the Solutions: Results From a National Survey of Physicians. http://www.choosingwisely.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Final-Choosing-Wisely-Survey-Report.pdf. Published May 1, 2014. Accessed July 8, 2016.

27. Corallo AN, Croxford R, Goodman DC, Bryan EL, Srivastava D, Stukel TA. A systematic review of medical practice variation in OECD countries. Health Policy. 2014;114(1):5-14. PubMed

28. Cutler D, Skinner JS, Stern AD, Wennberg DE. Physician Beliefs and Patient Preferences: A New Look at Regional Variation in Health Care Spending. NBER Working Paper No. 19320. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2013. http://www.nber.org/papers/w19320. Published August 2013. Accessed July 8, 2016.

29. Sirovich BE, Lipner RS, Johnston M, Holmboe ES. The association between residency training and internists’ ability to practice conservatively. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1640-1648. PubMed

30. Huttner B, Goossens H, Verheij T, Harbarth S. Characteristics and outcomes of public campaigns aimed at improving the use of antibiotics in outpatients in high-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(1):17-31. PubMed

31. Perz JF, Craig AS, Coffey CS, et al. Changes in antibiotic prescribing for children after a community-wide campaign. JAMA. 2002;287(23):3103-3109. PubMed

32. Sabuncu E, David J, Bernede-Bauduin C, et al. Significant reduction of antibiotic use in the community after a nationwide campaign in France, 2002-2007. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000084. PubMed

33. Flodgren G, Eccles MP, Shepperd S, Scott A, Parmelli E, Beyer FR. An overview of reviews evaluating the effectiveness of financial incentives in changing healthcare professional behaviours and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD009255. PubMed

34. Yoon J, Rose DE, Canelo I, et al. Medical home features of VHA primary care clinics and avoidable hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(9):1188-1194. PubMed

35. Gonzales R, Anderer T, McCulloch CE, et al. A cluster randomized trial of decision support strategies for reducing antibiotic use in acute bronchitis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):267-273. PubMed

36. Davis MM, Balasubramanian BA, Cifuentes M, et al. Clinician staffing, scheduling, and engagement strategies among primary care practices delivering integrated care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(suppl 1):S32-S40. PubMed

37. Dine CJ, Miller J, Fuld A, Bellini LM, Iwashyna TJ. Educating physicians-in-training about resource utilization and their own outcomes of care in the inpatient setting. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(2):175-180. PubMed

38. Elligsen M, Walker SA, Pinto R, et al. Audit and feedback to reduce broad-spectrum antibiotic use among intensive care unit patients: a controlled interrupted time series analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(4):354-361. PubMed

39. Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Effect of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention on broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing by primary care pediatricians: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2345-2352. PubMed

40. Taggart LR, Leung E, Muller MP, Matukas LM, Daneman N. Differential outcome of an antimicrobial stewardship audit and feedback program in two intensive care units: a controlled interrupted time series study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:480. PubMed

41. Hughes DR, Sunshine JH, Bhargavan M, Forman H. Physician self-referral for imaging and the cost of chronic care for Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care. 2011;49(9):857-864. PubMed

42. Ryskina KL, Pesko MF, Gossey JT, Caesar EP, Bishop TF. Brand name statin prescribing in a resident ambulatory practice: implications for teaching cost-conscious medicine. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):484-488. PubMed

43. Bhatia RS, Milford CE, Picard MH, Weiner RB. An educational intervention reduces the rate of inappropriate echocardiograms on an inpatient medical service. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(5):545-555. PubMed

44. Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(6):iii-iv, 1-72. PubMed

45. Wilson I, Cowin LS, Johnson M, Young H. Professional identity in medical students: pedagogical challenges to medical education. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(4):369-373. PubMed

46. Berger Z, Flickinger TE, Pfoh E, Martinez KA, Dy SM. Promoting engagement by patients and families to reduce adverse events in acute care settings: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(7):548-555. PubMed

47. Dykes PC, Stade D, Chang F, et al. Participatory design and development of a patient-centered toolkit to engage hospitalized patients and care partners in their plan of care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2014;2014:486-495. PubMed

48. Coxeter P, Del Mar CB, McGregor L, Beller EM, Hoffmann TC. Interventions to facilitate shared decision making to address antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(11):CD010907. PubMed

49. Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1):CD001431. PubMed

50. Bank AJ, Gage RM. Annual impact of scribes on physician productivity and revenue in a cardiology clinic. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;7:489-495. PubMed

51. Lyles CR, Sarkar U, Schillinger D, et al. Refilling medications through an online patient portal: consistent improvements in adherence across racial/ethnic groups. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(e1):e28-e33. PubMed

52. Kruse CS, Bolton K, Freriks G. The effect of patient portals on quality outcomes and its implications to meaningful use: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(2):e44. PubMed

53. Smith CD. Teaching high-value, cost-conscious care to residents: the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine-American College of Physicians curriculum. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(4):284-286. PubMed

54. Redberg RF. Less is more. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(7):584. PubMed

65. Birkmeyer JD, Reames BN, McCulloch P, Carr AJ, Campbell WB, Wennberg JE. Understanding of regional variation in the use of surgery. Lancet. 2013;382(9898):1121-1129. PubMed

66. Pearson SD, Goldman L, Orav EJ, et al. Triage decisions for emergency department patients with chest pain: do physicians’ risk attitudes make the difference? J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(10):557-564. PubMed

67. Tubbs EP, Elrod JA, Flum DR. Risk taking and tolerance of uncertainty: implications for surgeons. J Surg Res. 2006;131(1):1-6. PubMed

68. Zaat JO, van Eijk JT. General practitioners’ uncertainty, risk preference, and use of laboratory tests. Med Care. 1992;30(9):846-854. PubMed

69. Barnato AE, Tate JA, Rodriguez KL, Zickmund SL, Arnold RM. Norms of decision making in the ICU: a case study of two academic medical centers at the extremes of end-of-life treatment intensity. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(11):1886-1896. PubMed

70. Fisher ES, Wennberg JE, Stukel TA, et al. Associations among hospital capacity, utilization, and mortality of US Medicare beneficiaries, controlling for sociodemographic factors. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1351-1362. PubMed

71. Yasaitis LC, Bynum JP, Skinner JS. Association between physician supply, local practice norms, and outpatient visit rates. Med Care. 2013;51(6):524-531. PubMed

72. Chen C, Petterson S, Phillips R, Bazemore A, Mullan F. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385-2393. PubMed

73. Ryskina KL, Smith CD, Weissman A, et al. U.S. internal medicine residents’ knowledge and practice of high-value care: a national survey. Acad Med. 2015;90(10):1373-1379. PubMed

74. Khullar D, Chokshi DA, Kocher R, et al. Behavioral economics and physician compensation—promise and challenges. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2281-2283. PubMed

75. Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Reed M, Blumenthal D. Personal, organizational, and market level influences on physicians’ practice patterns: results of a national survey of primary care physicians. Med Care. 2001;39(8):889-905. PubMed

76. Fanari Z, Abraham N, Kolm P, et al. Aggressive measures to decrease “door to balloon” time and incidence of unnecessary cardiac catheterization: potential risks and role of quality improvement. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1614-1622. PubMed

77. Kerr EA, Lucatorto MA, Holleman R, Hogan MM, Klamerus ML, Hofer TP. Monitoring performance for blood pressure management among patients with diabetes mellitus: too much of a good thing? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(12):938-945. PubMed

78. Verhofstede R, Smets T, Cohen J, Costantini M, Van Den Noortgate N, Deliens L. Implementing the care programme for the last days of life in an acute geriatric hospital ward: a phase 2 mixed method study. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:27. PubMed

Medical services overuse is the provision of healthcare services for which there is no medical basis or for which harms equal or exceed benefits.1 This overuse drives poor-quality care and unnecessary cost.2,3 The high prevalence of overuse is recognized by patients,4 clinicians,5 and policymakers.6 Initiatives to reduce overuse have targeted physicians,7 the public,8 and medical educators9,10 but have had limited impact.11,12 Few studies have addressed methods for reducing overuse, and de-implementation of nonbeneficial practices has proved challenging.1,13,14 Models for reducing overuse are only theoretical15 or are focused on administrative decisions.16,17 We think a practical framework is needed. We used an iterative process, informed by expert opinion and discussion, to design such a framework.

METHODS

The authors, who have expertise in overuse, value, medical education, evidence-based medicine, and implementation science, reviewed related conceptual frameworks18 and evidence regarding drivers of overuse. We organized these drivers into domains to create a draft framework, which we presented at Preventing Overdiagnosis 2015, a meeting of clinicians, patients, and policymakers interested in overuse. We incorporated feedback from meeting attendees to modify framework domains, and we performed structured searches (using key words in Pubmed) to explore, and estimate the strength of, evidence supporting items within each domain. We rated supporting evidence as strong (studies found a clear correlation between a factor and overuse), moderate (evidence suggests such a correlation or demonstrates a correlation between a particular factor and utilization but not overuse per se), weak (only indirect evidence exists), or absent (no studies identified evaluating a particular factor). All authors reached consensus on ratings.

Framework Principles and Evidence

Patient-centered definition of overuse. During framework development, defining clinical appropriateness emerged as the primary challenge to identifying and reducing overuse. Although some care generally is appropriate based on strong evidence of benefit, and some is inappropriate given a clear lack of benefit or harm, much care is of unclear or variable benefit. Practice guidelines can help identify overuse, but their utility may be limited by lack of evidence in specific clinical situations,19 and their recommendations may apply poorly to an individual patient. This presents challenges to using guidelines to identify and reduce overuse.

Despite limitations, the scope of overuse has been estimated by applying broad, often guideline-based, criteria for care appropriateness to administrative data.20 Unfortunately, these estimates provide little direction to clinicians and patients partnering to make usage decisions. During framework development, we identified the importance of a patient-level, patient-specific definition of overuse. This approach reinforces the importance of meeting patient needs while standardizing treatments to reduce overuse. A patient-centered approach may also assist professional societies and advocacy groups in developing actionable campaigns and may uncover evidence gaps.

Centrality of patient-clinician interaction. During framework development, the patient–clinician interaction emerged as the nexus through which drivers of overuse exert influence. The centrality of this interaction has been demonstrated in studies of the relationship between care continuity and overuse21 or utilization,22,23 by evidence that communication and patient–clinician relationships affect utilization,24 and by the observation that clinician training in shared decision-making reduces overuse.25 A patient-centered framework assumes that, at least in the weighing of clinically reasonable options, a patient-centered approach optimizes outcomes for that patient.

Incorporating drivers of overuse. We incorporated drivers of overuse into domains and related them to the patient–clinician interaction.26 Domains included the culture of healthcare consumption, patient factors and experiences, the practice environment, the culture of professional medicine, and clinician attitudes and beliefs.

We characterized the evidence illustrating how drivers within each domain influence healthcare use. The evidence for each domain is listed in Table 1.

RESULTS

The final framework is shown in the Figure. Within the healthcare system, patients are influenced by the culture of healthcare consumption, which varies within and among countries.27 Clinicians are influenced by the culture of medical care, which varies by practice setting,28 and by their training environment.29 Both clinicians and patients are influenced by the practice environment and by personal experiences. Ultimately, clinical decisions occur within the specific patient–clinician interaction.24 Table 1 lists each domain’s components, likely impact on overuse, and estimated strength of supporting evidence. Interventions can be conceptualized within appropriate domains or through the interaction between patient and clinician.

DISCUSSION

We developed a novel and practical conceptual framework for characterizing drivers of overuse and potential intervention points. To our knowledge, this is the first framework incorporating a patient-specific approach to overuse and emphasizing the patient–clinician interaction. Key strengths of framework development are inclusion of a range of perspectives and characterization of the evidence within each domain. Limitations include lack of a formal systematic review and broad, qualitative assessments of evidence strength. However, we believe this framework provides an important conceptual foundation for the study of overuse and interventions to reduce overuse.

Framework Applications

This framework, which highlights the many drivers of overuse, can facilitate understanding of overuse and help conceptualize change, prioritize research goals, and inform specific interventions. For policymakers, the framework can inform efforts to reduce overuse by emphasizing the need for complex interventions and by clarifying the likely impact of interventions targeting specific domains. Similarly, for clinicians and quality improvement professionals, the framework can ground root cause analyses of overuse-related problems and inform allocation of limited resources. Finally, the relatively weak evidence on the role of most acknowledged drivers of overuse suggests an important research agenda. Specifically, several pressing needs have been identified: defining relevant physician and patient cultural factors, investigating interventions to impact culture, defining practice environment features that optimize care appropriateness, and describing specific patient–clinician interaction practices that minimize overuse while providing needed care.

Targeting Interventions

Domains within the framework are influenced by different types of interventions, and different stakeholders may target different domains. For example:

- The culture of healthcare consumption may be influenced through public education (eg, Choosing Wisely® patient resources)30-32 and public health campaigns.

- The practice environment may be influenced by initiatives to align clinician incentives,33 team care,34 electronic health record interventions,35 and improved access.36

- Clinician attitudes and beliefs may be influenced by audit and feedback,37-40 reflection,41 role modeling,42 and education.43-45

- Patient attitudes and beliefs may be influenced by education, access to price and quality information, and increased engagement in care.46,47

- For clinicians, the patient–clinician interaction can be improved through training in communication and shared decision-making,25 through access to information (eg, costs) that can be easily shared with patients,48,49 and through novel visit structures (eg, scribes).50

- On the patient side, this interaction can be optimized with improved access (eg, through telemedicine)51,52 or with patient empowerment during hospitalization.

- The culture of medicine is difficult to influence. Change likely will occur through:

○ Regulatory interventions (eg, Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative of Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation).

○ Educational initiatives (eg, high-value care curricula of Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine/American College of Physicians53).

○ Medical journal features (eg, “Less Is More” in JAMA Internal Medicine54 and “Things We Do for No Reason” in Journal of Hospital Medicine).

○ Professional organizations (eg, Choosing Wisely®).

As organizations implement quality improvement initiatives to reduce overuse of services, the framework can be used to target interventions to relevant domains. For example, a hospital leader who wants to reduce opioid prescribing may use the framework to identify the factors that encourage prescribing in each domain—poor understanding of pain treatment (a clinician factor), desire for early discharge encouraging overly aggressive pain management (an environmental factor), patient demand for opioids combined with poor understanding of harms (patient factors), and poor communication regarding pain (a patient–clinician interaction factor). Although not all relevant factors can be addressed, their classification by domain facilitates intervention, in this case perhaps leading to a focus on clinician and patient education on opioids and development of a practical communication tool that targets 3 domains. Table 2 lists ways in which the framework informs approaches to this and other overused services in the hospital setting. Note that some drivers can be acknowledged without identifying targeted interventions.

Moving Forward