User login

Birth defects in United States up 20-fold since Zika outbreak began

Birth defects potentially linked to cases of Zika virus in the United States have increased by a factor of nearly 20 since the virus first made its way into the country, according to new findings by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“The higher proportion of these defects among pregnancies with laboratory evidence of Zika infection in USZPR [U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry] supports the relationship between congenital Zika virus infection and these birth defects,” wrote the authors of a new report led by Janet D. Cragan, MD, of the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the CDC (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:219-22).

[[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]]

Dr. Cragan and her coauthors retrospectively examined data on birth defects in three regions of the country: Massachusetts during 2013, North Carolina during 2013, and Atlanta during 2013-2014. The investigators focused on birth defects associated with prenatal Zika virus infections, mainly brain abnormalities and microcephaly.

The rate of total birth defects across the three regions was 2.86 per 1,000 live births, with 747 infants and fetuses identified as having one or more defects. Microcephaly and brain abnormalities alone occurred at a rate of 1.50 per 1,000 live births, with eye abnormalities and central nervous system dysfunction also occurring.

These numbers are relatively low when compared with data from Jan. 15 through Sept. 22, 2016. The birth defect rate jumped up to 58.8 per 1,000 live births, according to data from the USZPR, which found evidence of 26 infants and fetuses with brain or cranial defects in 442 completed pregnancies. These infants were all born to mothers with laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infections.

“Among 410 (55%) infants or fetuses with information on the earliest age a birth defect was recorded, 371 (90%) had evidence of a birth defect meeting the Zika definition before age 3 months,” the authors explained. “More than half of those with brain abnormalities or microcephaly or with neural tube defects and other early brain malformations had evidence of these defects noted prenatally (55% and 89%, respectively).”

Dr. Cragan and her colleagues hope that this evidence will further solidify the link between Zika virus and birth defects and pave the way for more population-based studies.

“These data demonstrate the critical contribution of population-based birth defects surveillance to understanding the impact of Zika virus infection during pregnancy,” the authors concluded. “In 2016, CDC provided funding for 45 local, state, and territorial health departments to conduct rapid population-based surveillance for defects potentially related to Zika virus infection, which will provide essential data to monitor the impact of Zika virus infection in the United States.”

Birth defects potentially linked to cases of Zika virus in the United States have increased by a factor of nearly 20 since the virus first made its way into the country, according to new findings by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“The higher proportion of these defects among pregnancies with laboratory evidence of Zika infection in USZPR [U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry] supports the relationship between congenital Zika virus infection and these birth defects,” wrote the authors of a new report led by Janet D. Cragan, MD, of the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the CDC (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:219-22).

[[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]]

Dr. Cragan and her coauthors retrospectively examined data on birth defects in three regions of the country: Massachusetts during 2013, North Carolina during 2013, and Atlanta during 2013-2014. The investigators focused on birth defects associated with prenatal Zika virus infections, mainly brain abnormalities and microcephaly.

The rate of total birth defects across the three regions was 2.86 per 1,000 live births, with 747 infants and fetuses identified as having one or more defects. Microcephaly and brain abnormalities alone occurred at a rate of 1.50 per 1,000 live births, with eye abnormalities and central nervous system dysfunction also occurring.

These numbers are relatively low when compared with data from Jan. 15 through Sept. 22, 2016. The birth defect rate jumped up to 58.8 per 1,000 live births, according to data from the USZPR, which found evidence of 26 infants and fetuses with brain or cranial defects in 442 completed pregnancies. These infants were all born to mothers with laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infections.

“Among 410 (55%) infants or fetuses with information on the earliest age a birth defect was recorded, 371 (90%) had evidence of a birth defect meeting the Zika definition before age 3 months,” the authors explained. “More than half of those with brain abnormalities or microcephaly or with neural tube defects and other early brain malformations had evidence of these defects noted prenatally (55% and 89%, respectively).”

Dr. Cragan and her colleagues hope that this evidence will further solidify the link between Zika virus and birth defects and pave the way for more population-based studies.

“These data demonstrate the critical contribution of population-based birth defects surveillance to understanding the impact of Zika virus infection during pregnancy,” the authors concluded. “In 2016, CDC provided funding for 45 local, state, and territorial health departments to conduct rapid population-based surveillance for defects potentially related to Zika virus infection, which will provide essential data to monitor the impact of Zika virus infection in the United States.”

Birth defects potentially linked to cases of Zika virus in the United States have increased by a factor of nearly 20 since the virus first made its way into the country, according to new findings by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“The higher proportion of these defects among pregnancies with laboratory evidence of Zika infection in USZPR [U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry] supports the relationship between congenital Zika virus infection and these birth defects,” wrote the authors of a new report led by Janet D. Cragan, MD, of the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the CDC (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:219-22).

[[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]]

Dr. Cragan and her coauthors retrospectively examined data on birth defects in three regions of the country: Massachusetts during 2013, North Carolina during 2013, and Atlanta during 2013-2014. The investigators focused on birth defects associated with prenatal Zika virus infections, mainly brain abnormalities and microcephaly.

The rate of total birth defects across the three regions was 2.86 per 1,000 live births, with 747 infants and fetuses identified as having one or more defects. Microcephaly and brain abnormalities alone occurred at a rate of 1.50 per 1,000 live births, with eye abnormalities and central nervous system dysfunction also occurring.

These numbers are relatively low when compared with data from Jan. 15 through Sept. 22, 2016. The birth defect rate jumped up to 58.8 per 1,000 live births, according to data from the USZPR, which found evidence of 26 infants and fetuses with brain or cranial defects in 442 completed pregnancies. These infants were all born to mothers with laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infections.

“Among 410 (55%) infants or fetuses with information on the earliest age a birth defect was recorded, 371 (90%) had evidence of a birth defect meeting the Zika definition before age 3 months,” the authors explained. “More than half of those with brain abnormalities or microcephaly or with neural tube defects and other early brain malformations had evidence of these defects noted prenatally (55% and 89%, respectively).”

Dr. Cragan and her colleagues hope that this evidence will further solidify the link between Zika virus and birth defects and pave the way for more population-based studies.

“These data demonstrate the critical contribution of population-based birth defects surveillance to understanding the impact of Zika virus infection during pregnancy,” the authors concluded. “In 2016, CDC provided funding for 45 local, state, and territorial health departments to conduct rapid population-based surveillance for defects potentially related to Zika virus infection, which will provide essential data to monitor the impact of Zika virus infection in the United States.”

ACIP debates adding third dose to current mumps recommendation

Because of a spate of mumps outbreaks over the last decade, adding a third dose of the mumps vaccine to the currently standard two-dose series was debated during a meeting of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

“Data [on recent outbreaks] were presented to ACIP in 2012, and ACIP determined that the data were insufficient to recommend for or against the use of a third dose of MMR vaccine for mumps outbreak control,” explained Mona Marin, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. “Subsequently, CDC issued guidance for consideration for use of a third dose in specifically identified target populations, along with criteria for public health departments to consider for decision-making. That includes settings with high two-dose coverage, intense exposure, and ongoing transmission.”

Recent data, explained Dr. Marin, have “raised the question of the short- and long-term benefits of a third dose, and implications for routine use versus outbreak policy recommendations.” However, the efficacy of a third vaccine dose has not been verified against cell memory, cell-mediated response, and other factors. These will need to be evaluated before a third dose can be debated further, let alone approved.

The mumps work group, therefore, will continue to assess the benefits and potential harms of adding a third dose to the immunization schedule. Dr. Marin explained that they hope to be able to discuss this further, and perhaps vote on it, during the next ACIP meeting, which is scheduled to take place on June 21 and 22 of this year.

“The current two-dose schedule is sufficient for mumps control in the general population, but outbreaks can occur in well-vaccinated populations in specific settings,” Dr. Marin said. “Intense exposure settings and waning immunity appear to be risk factors for secondary vaccine failure. The benefit of a third MMR dose still needs to be assessed.”

Dr. Marin said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Because of a spate of mumps outbreaks over the last decade, adding a third dose of the mumps vaccine to the currently standard two-dose series was debated during a meeting of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

“Data [on recent outbreaks] were presented to ACIP in 2012, and ACIP determined that the data were insufficient to recommend for or against the use of a third dose of MMR vaccine for mumps outbreak control,” explained Mona Marin, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. “Subsequently, CDC issued guidance for consideration for use of a third dose in specifically identified target populations, along with criteria for public health departments to consider for decision-making. That includes settings with high two-dose coverage, intense exposure, and ongoing transmission.”

Recent data, explained Dr. Marin, have “raised the question of the short- and long-term benefits of a third dose, and implications for routine use versus outbreak policy recommendations.” However, the efficacy of a third vaccine dose has not been verified against cell memory, cell-mediated response, and other factors. These will need to be evaluated before a third dose can be debated further, let alone approved.

The mumps work group, therefore, will continue to assess the benefits and potential harms of adding a third dose to the immunization schedule. Dr. Marin explained that they hope to be able to discuss this further, and perhaps vote on it, during the next ACIP meeting, which is scheduled to take place on June 21 and 22 of this year.

“The current two-dose schedule is sufficient for mumps control in the general population, but outbreaks can occur in well-vaccinated populations in specific settings,” Dr. Marin said. “Intense exposure settings and waning immunity appear to be risk factors for secondary vaccine failure. The benefit of a third MMR dose still needs to be assessed.”

Dr. Marin said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Because of a spate of mumps outbreaks over the last decade, adding a third dose of the mumps vaccine to the currently standard two-dose series was debated during a meeting of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

“Data [on recent outbreaks] were presented to ACIP in 2012, and ACIP determined that the data were insufficient to recommend for or against the use of a third dose of MMR vaccine for mumps outbreak control,” explained Mona Marin, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. “Subsequently, CDC issued guidance for consideration for use of a third dose in specifically identified target populations, along with criteria for public health departments to consider for decision-making. That includes settings with high two-dose coverage, intense exposure, and ongoing transmission.”

Recent data, explained Dr. Marin, have “raised the question of the short- and long-term benefits of a third dose, and implications for routine use versus outbreak policy recommendations.” However, the efficacy of a third vaccine dose has not been verified against cell memory, cell-mediated response, and other factors. These will need to be evaluated before a third dose can be debated further, let alone approved.

The mumps work group, therefore, will continue to assess the benefits and potential harms of adding a third dose to the immunization schedule. Dr. Marin explained that they hope to be able to discuss this further, and perhaps vote on it, during the next ACIP meeting, which is scheduled to take place on June 21 and 22 of this year.

“The current two-dose schedule is sufficient for mumps control in the general population, but outbreaks can occur in well-vaccinated populations in specific settings,” Dr. Marin said. “Intense exposure settings and waning immunity appear to be risk factors for secondary vaccine failure. The benefit of a third MMR dose still needs to be assessed.”

Dr. Marin said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM AN ACIP MEETING

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Using FLIP to assess upper GI tract still murky territory

New clinical practice advice has been issued for use of the functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP) to assess disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract, with the main takeaway being the device’s potency in diagnosing achalasia.

“Although the strongest data appear to be focused on the management of achalasia, emerging evidence supports the clinical relevance of FLIP in the assessment of disease severity and as an outcome measure in [eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE)] intervention trials,” wrote the authors of the update, led by John E. Pandolfino, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago. The report is in the March issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.

10.022).

In terms of evaluating the LES, however, FLIP can be used during laparoscopic Heller myotomy or peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) as a way of monitoring the LES. Using FLIP this way can help clinicians and surgeons personalize the procedure to each patient, even while it’s ongoing. FLIP also can be used with dilation balloons, with the balloon diameter allowing dilation measurement without the need to also use fluoroscopy.

For treating gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), the evidence found in existing literature points with less certainty toward use of FLIP.

“The role of FLIP for physiologic evaluation and management in GERD remains appealing; however, the level of evidence is low and currently FLIP should not be used in routine GERD management,” the authors explained. “Future outcome studies are needed to substantiate the utility of FLIP in GERD and to develop metrics that predict severity and treatment response after antireflux procedures.”

FLIP can be used in managing eosinophilic esophagitis, but is recommended only in certain scenarios. According to the authors, FLIP can be used to measure esophageal narrowing and the overall esophageal body. FLIP also can be used to measure esophageal distensibility, and, in the case of at least one study reviewed by the authors, allows “significantly greater accuracy and precision in estimating the effects of remodeling” in certain patients.

Dr. Pandolfino and his colleagues warned that “current recommendations are limited by the low level of evidence and lack of generalized availability of the analysis paradigms.” They noted the need for “further outcome studies that validate the distensibility plateau threshold and further refinements in software analyses to make this methodology more generalizable.”

Overall, the authors concluded, more study still needs to be done to ascertain exactly what FLIP is capable of and when it can be used to greatest effect. In addition to evaluating its benefit in patients with GERD, research should focus on how to make data obtained via FLIP easier to interpret and put to use.

“More work is needed [that] focuses on optimizing data analysis, standardizing protocols, and defining outcome metrics prior to the widespread adoption [of FLIP] into general clinical practice,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Pandolfino disclosed relationships with Medtronic and Sandhill Scientific. Other coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

*This story updated on 3/9/2017.

New clinical practice advice has been issued for use of the functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP) to assess disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract, with the main takeaway being the device’s potency in diagnosing achalasia.

“Although the strongest data appear to be focused on the management of achalasia, emerging evidence supports the clinical relevance of FLIP in the assessment of disease severity and as an outcome measure in [eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE)] intervention trials,” wrote the authors of the update, led by John E. Pandolfino, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago. The report is in the March issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.

10.022).

In terms of evaluating the LES, however, FLIP can be used during laparoscopic Heller myotomy or peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) as a way of monitoring the LES. Using FLIP this way can help clinicians and surgeons personalize the procedure to each patient, even while it’s ongoing. FLIP also can be used with dilation balloons, with the balloon diameter allowing dilation measurement without the need to also use fluoroscopy.

For treating gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), the evidence found in existing literature points with less certainty toward use of FLIP.

“The role of FLIP for physiologic evaluation and management in GERD remains appealing; however, the level of evidence is low and currently FLIP should not be used in routine GERD management,” the authors explained. “Future outcome studies are needed to substantiate the utility of FLIP in GERD and to develop metrics that predict severity and treatment response after antireflux procedures.”

FLIP can be used in managing eosinophilic esophagitis, but is recommended only in certain scenarios. According to the authors, FLIP can be used to measure esophageal narrowing and the overall esophageal body. FLIP also can be used to measure esophageal distensibility, and, in the case of at least one study reviewed by the authors, allows “significantly greater accuracy and precision in estimating the effects of remodeling” in certain patients.

Dr. Pandolfino and his colleagues warned that “current recommendations are limited by the low level of evidence and lack of generalized availability of the analysis paradigms.” They noted the need for “further outcome studies that validate the distensibility plateau threshold and further refinements in software analyses to make this methodology more generalizable.”

Overall, the authors concluded, more study still needs to be done to ascertain exactly what FLIP is capable of and when it can be used to greatest effect. In addition to evaluating its benefit in patients with GERD, research should focus on how to make data obtained via FLIP easier to interpret and put to use.

“More work is needed [that] focuses on optimizing data analysis, standardizing protocols, and defining outcome metrics prior to the widespread adoption [of FLIP] into general clinical practice,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Pandolfino disclosed relationships with Medtronic and Sandhill Scientific. Other coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

*This story updated on 3/9/2017.

New clinical practice advice has been issued for use of the functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP) to assess disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract, with the main takeaway being the device’s potency in diagnosing achalasia.

“Although the strongest data appear to be focused on the management of achalasia, emerging evidence supports the clinical relevance of FLIP in the assessment of disease severity and as an outcome measure in [eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE)] intervention trials,” wrote the authors of the update, led by John E. Pandolfino, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago. The report is in the March issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.

10.022).

In terms of evaluating the LES, however, FLIP can be used during laparoscopic Heller myotomy or peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) as a way of monitoring the LES. Using FLIP this way can help clinicians and surgeons personalize the procedure to each patient, even while it’s ongoing. FLIP also can be used with dilation balloons, with the balloon diameter allowing dilation measurement without the need to also use fluoroscopy.

For treating gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), the evidence found in existing literature points with less certainty toward use of FLIP.

“The role of FLIP for physiologic evaluation and management in GERD remains appealing; however, the level of evidence is low and currently FLIP should not be used in routine GERD management,” the authors explained. “Future outcome studies are needed to substantiate the utility of FLIP in GERD and to develop metrics that predict severity and treatment response after antireflux procedures.”

FLIP can be used in managing eosinophilic esophagitis, but is recommended only in certain scenarios. According to the authors, FLIP can be used to measure esophageal narrowing and the overall esophageal body. FLIP also can be used to measure esophageal distensibility, and, in the case of at least one study reviewed by the authors, allows “significantly greater accuracy and precision in estimating the effects of remodeling” in certain patients.

Dr. Pandolfino and his colleagues warned that “current recommendations are limited by the low level of evidence and lack of generalized availability of the analysis paradigms.” They noted the need for “further outcome studies that validate the distensibility plateau threshold and further refinements in software analyses to make this methodology more generalizable.”

Overall, the authors concluded, more study still needs to be done to ascertain exactly what FLIP is capable of and when it can be used to greatest effect. In addition to evaluating its benefit in patients with GERD, research should focus on how to make data obtained via FLIP easier to interpret and put to use.

“More work is needed [that] focuses on optimizing data analysis, standardizing protocols, and defining outcome metrics prior to the widespread adoption [of FLIP] into general clinical practice,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Pandolfino disclosed relationships with Medtronic and Sandhill Scientific. Other coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

*This story updated on 3/9/2017.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Best practice advice on EBT use released

The AGA Institute has released a series of new best practice statements that gastroenterologists should use when considering a patient for endoscopic bariatric treatments or surgeries (EBTs).

“There is a need for less-invasive weight loss therapies that are more effective and durable than lifestyle interventions alone, less invasive and risky than bariatric surgery, and easily performed at a lower expense than that of surgery, thereby allowing improved access and application to a larger segment of the population with moderate obesity,” wrote the authors of the expert review, led by Barham K. Abu Dayyeh, MD of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. The report is in the March issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.035). “[EBTs] potentially meet these criteria and may provide an effective treatment approach to obesity in selected patients.”

The best practice statements come from a review of relevant studies in the Ovid, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus databases, among others, that were published between Jan. 1, 2000, and Sept. 30, 2016.

EBTs should be used on patients who have already been unable to lose weight despite lifestyle interventions and more traditional weight loss methods. However, patients that undergo EBTs should also be placed on a weight loss regimen that includes diet, exercise, and lifestyle changes.

In addition to being used for weight loss, they can also be used to transition a patient to traditional bariatric surgery, or to lower a patient’s weight so that they can undergo a different procedure unrelated to bariatric surgery. Anyone being considered for EBT, or a weight loss regimen involving EBT, should be thoroughly evaluated for comorbidities, behavior, or medical concerns that could lead to adverse effects.

Any patients who are placed on EBT regimens should be followed up regularly by their clinicians, to monitor their progress in terms of weight loss and the development of any adverse effects. Should any adverse outcomes arise, alternative therapies should be implemented as soon as possible. Clinicians are advised to know the ins and outs of risks, contraindications, and potential complications related to EBTs before ever implementing them in their practice, let alone recommending them to a patient.

Finally, it’s imperative that health care institutions with EBT programs make sure there are training protocols clinicians must stringently follow before being allowed to perform EBT procedures.

“Moving ahead, it will be important to better incorporate training in obesity management principles into the GI fellowship curriculum to have a more significant impact,” the authors wrote, adding that it’s important to study the “tandem and sequential use of a combination of EBTs and obesity pharmacotherapies in addition to a comprehensive life-style intervention program.”

Dr. Abu Dayyeh disclosed relationships with Apollo Endosurgery, Metamodix, Aspire Bariatric, and GI Dynamics. Other coauthors also disclosed potential conflicting interests.

The AGA Institute has released a series of new best practice statements that gastroenterologists should use when considering a patient for endoscopic bariatric treatments or surgeries (EBTs).

“There is a need for less-invasive weight loss therapies that are more effective and durable than lifestyle interventions alone, less invasive and risky than bariatric surgery, and easily performed at a lower expense than that of surgery, thereby allowing improved access and application to a larger segment of the population with moderate obesity,” wrote the authors of the expert review, led by Barham K. Abu Dayyeh, MD of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. The report is in the March issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.035). “[EBTs] potentially meet these criteria and may provide an effective treatment approach to obesity in selected patients.”

The best practice statements come from a review of relevant studies in the Ovid, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus databases, among others, that were published between Jan. 1, 2000, and Sept. 30, 2016.

EBTs should be used on patients who have already been unable to lose weight despite lifestyle interventions and more traditional weight loss methods. However, patients that undergo EBTs should also be placed on a weight loss regimen that includes diet, exercise, and lifestyle changes.

In addition to being used for weight loss, they can also be used to transition a patient to traditional bariatric surgery, or to lower a patient’s weight so that they can undergo a different procedure unrelated to bariatric surgery. Anyone being considered for EBT, or a weight loss regimen involving EBT, should be thoroughly evaluated for comorbidities, behavior, or medical concerns that could lead to adverse effects.

Any patients who are placed on EBT regimens should be followed up regularly by their clinicians, to monitor their progress in terms of weight loss and the development of any adverse effects. Should any adverse outcomes arise, alternative therapies should be implemented as soon as possible. Clinicians are advised to know the ins and outs of risks, contraindications, and potential complications related to EBTs before ever implementing them in their practice, let alone recommending them to a patient.

Finally, it’s imperative that health care institutions with EBT programs make sure there are training protocols clinicians must stringently follow before being allowed to perform EBT procedures.

“Moving ahead, it will be important to better incorporate training in obesity management principles into the GI fellowship curriculum to have a more significant impact,” the authors wrote, adding that it’s important to study the “tandem and sequential use of a combination of EBTs and obesity pharmacotherapies in addition to a comprehensive life-style intervention program.”

Dr. Abu Dayyeh disclosed relationships with Apollo Endosurgery, Metamodix, Aspire Bariatric, and GI Dynamics. Other coauthors also disclosed potential conflicting interests.

The AGA Institute has released a series of new best practice statements that gastroenterologists should use when considering a patient for endoscopic bariatric treatments or surgeries (EBTs).

“There is a need for less-invasive weight loss therapies that are more effective and durable than lifestyle interventions alone, less invasive and risky than bariatric surgery, and easily performed at a lower expense than that of surgery, thereby allowing improved access and application to a larger segment of the population with moderate obesity,” wrote the authors of the expert review, led by Barham K. Abu Dayyeh, MD of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. The report is in the March issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.035). “[EBTs] potentially meet these criteria and may provide an effective treatment approach to obesity in selected patients.”

The best practice statements come from a review of relevant studies in the Ovid, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus databases, among others, that were published between Jan. 1, 2000, and Sept. 30, 2016.

EBTs should be used on patients who have already been unable to lose weight despite lifestyle interventions and more traditional weight loss methods. However, patients that undergo EBTs should also be placed on a weight loss regimen that includes diet, exercise, and lifestyle changes.

In addition to being used for weight loss, they can also be used to transition a patient to traditional bariatric surgery, or to lower a patient’s weight so that they can undergo a different procedure unrelated to bariatric surgery. Anyone being considered for EBT, or a weight loss regimen involving EBT, should be thoroughly evaluated for comorbidities, behavior, or medical concerns that could lead to adverse effects.

Any patients who are placed on EBT regimens should be followed up regularly by their clinicians, to monitor their progress in terms of weight loss and the development of any adverse effects. Should any adverse outcomes arise, alternative therapies should be implemented as soon as possible. Clinicians are advised to know the ins and outs of risks, contraindications, and potential complications related to EBTs before ever implementing them in their practice, let alone recommending them to a patient.

Finally, it’s imperative that health care institutions with EBT programs make sure there are training protocols clinicians must stringently follow before being allowed to perform EBT procedures.

“Moving ahead, it will be important to better incorporate training in obesity management principles into the GI fellowship curriculum to have a more significant impact,” the authors wrote, adding that it’s important to study the “tandem and sequential use of a combination of EBTs and obesity pharmacotherapies in addition to a comprehensive life-style intervention program.”

Dr. Abu Dayyeh disclosed relationships with Apollo Endosurgery, Metamodix, Aspire Bariatric, and GI Dynamics. Other coauthors also disclosed potential conflicting interests.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

AGA Clinical Practice Update: PPIs should be prescribed sparingly, carefully

Updated best practice statements regarding the use of proton pump inhibitors first detail what types of patients should be using short and long-term PPIs.

“When PPIs are appropriately prescribed, their benefits are likely to outweigh their risks [but] when PPIs are inappropriately prescribed, modest risks become important because there is no potential benefit,” wrote the authors of the updated guidance, published in the March issue of Gastroenterology.

“There is currently insufficient evidence to recommend specific strategies for mitigating PPI adverse effects,” noted Daniel E. Freedberg, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and his colleagues.

PPIs should be used on a short-term basis for individuals with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or conditions such as erosive esophagitis. These patients can also use PPIs for maintenance and occasional symptom management, but those with uncomplicated GERD should be weaned off PPIs if they respond favorably to them.

If a patient is unable to be weaned off PPIs, then ambulatory esophageal pH and impedance monitoring should be done, as this will allow clinicians to determine if the patient has a functional syndrome or GERD. Lifelong PPI treatment should not be considered until this step is taken, according to the new best practice statements.

“Short-term PPIs are highly effective for uncomplicated GERD [but] because patients who cannot reduce PPIs face lifelong therapy, we would consider testing for an acid-related disorder in this situation,” the authors explained. “However, there is no high-quality evidence on which to base this recommendation.”

Patients who have symptomatic GERD or Barrett’s esophagus, either symptomatic or asymptomatic, should be on long-term PPI treatment. Patients who are at a higher risk for NSAID-induced ulcer bleeding should be taking PPIs if they continue to take NSAIDs.

When recommending long-term PPI treatment for a patient, the patient need not use probiotics on a regular basis; there appears to be no need to routinely check the patient’s bone mineral density, serum creatinine, magnesium, or vitamin B12 level on a regular basis. In addition, they need not consume more than the Recommended Dietary Allowance of calcium, magnesium, or vitamin B12.

Finally, the authors state that “specific PPI formulations should not be selected based on potential risks.” This is because no evidence has been found indicating that PPI formulations can be ranked in any way based on risk.

These recommendations come from the AGA’s Clinical Practice Updates Committee, which pored through studies published through July 2016 in the PubMed, EMbase, and Cochrane library databases. Expert opinions and quality assessments on each study contributed to forming these best practice statements.

“In sum, the best current strategies for mitigating the potential risks of long-term PPIs are to avoid prescribing them when they are not indicated and to reduce them to their minimum dose when they are indicated,” Dr. Freedberg and his colleagues concluded.

The researchers did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Updated best practice statements regarding the use of proton pump inhibitors first detail what types of patients should be using short and long-term PPIs.

“When PPIs are appropriately prescribed, their benefits are likely to outweigh their risks [but] when PPIs are inappropriately prescribed, modest risks become important because there is no potential benefit,” wrote the authors of the updated guidance, published in the March issue of Gastroenterology.

“There is currently insufficient evidence to recommend specific strategies for mitigating PPI adverse effects,” noted Daniel E. Freedberg, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and his colleagues.

PPIs should be used on a short-term basis for individuals with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or conditions such as erosive esophagitis. These patients can also use PPIs for maintenance and occasional symptom management, but those with uncomplicated GERD should be weaned off PPIs if they respond favorably to them.

If a patient is unable to be weaned off PPIs, then ambulatory esophageal pH and impedance monitoring should be done, as this will allow clinicians to determine if the patient has a functional syndrome or GERD. Lifelong PPI treatment should not be considered until this step is taken, according to the new best practice statements.

“Short-term PPIs are highly effective for uncomplicated GERD [but] because patients who cannot reduce PPIs face lifelong therapy, we would consider testing for an acid-related disorder in this situation,” the authors explained. “However, there is no high-quality evidence on which to base this recommendation.”

Patients who have symptomatic GERD or Barrett’s esophagus, either symptomatic or asymptomatic, should be on long-term PPI treatment. Patients who are at a higher risk for NSAID-induced ulcer bleeding should be taking PPIs if they continue to take NSAIDs.

When recommending long-term PPI treatment for a patient, the patient need not use probiotics on a regular basis; there appears to be no need to routinely check the patient’s bone mineral density, serum creatinine, magnesium, or vitamin B12 level on a regular basis. In addition, they need not consume more than the Recommended Dietary Allowance of calcium, magnesium, or vitamin B12.

Finally, the authors state that “specific PPI formulations should not be selected based on potential risks.” This is because no evidence has been found indicating that PPI formulations can be ranked in any way based on risk.

These recommendations come from the AGA’s Clinical Practice Updates Committee, which pored through studies published through July 2016 in the PubMed, EMbase, and Cochrane library databases. Expert opinions and quality assessments on each study contributed to forming these best practice statements.

“In sum, the best current strategies for mitigating the potential risks of long-term PPIs are to avoid prescribing them when they are not indicated and to reduce them to their minimum dose when they are indicated,” Dr. Freedberg and his colleagues concluded.

The researchers did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Updated best practice statements regarding the use of proton pump inhibitors first detail what types of patients should be using short and long-term PPIs.

“When PPIs are appropriately prescribed, their benefits are likely to outweigh their risks [but] when PPIs are inappropriately prescribed, modest risks become important because there is no potential benefit,” wrote the authors of the updated guidance, published in the March issue of Gastroenterology.

“There is currently insufficient evidence to recommend specific strategies for mitigating PPI adverse effects,” noted Daniel E. Freedberg, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and his colleagues.

PPIs should be used on a short-term basis for individuals with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or conditions such as erosive esophagitis. These patients can also use PPIs for maintenance and occasional symptom management, but those with uncomplicated GERD should be weaned off PPIs if they respond favorably to them.

If a patient is unable to be weaned off PPIs, then ambulatory esophageal pH and impedance monitoring should be done, as this will allow clinicians to determine if the patient has a functional syndrome or GERD. Lifelong PPI treatment should not be considered until this step is taken, according to the new best practice statements.

“Short-term PPIs are highly effective for uncomplicated GERD [but] because patients who cannot reduce PPIs face lifelong therapy, we would consider testing for an acid-related disorder in this situation,” the authors explained. “However, there is no high-quality evidence on which to base this recommendation.”

Patients who have symptomatic GERD or Barrett’s esophagus, either symptomatic or asymptomatic, should be on long-term PPI treatment. Patients who are at a higher risk for NSAID-induced ulcer bleeding should be taking PPIs if they continue to take NSAIDs.

When recommending long-term PPI treatment for a patient, the patient need not use probiotics on a regular basis; there appears to be no need to routinely check the patient’s bone mineral density, serum creatinine, magnesium, or vitamin B12 level on a regular basis. In addition, they need not consume more than the Recommended Dietary Allowance of calcium, magnesium, or vitamin B12.

Finally, the authors state that “specific PPI formulations should not be selected based on potential risks.” This is because no evidence has been found indicating that PPI formulations can be ranked in any way based on risk.

These recommendations come from the AGA’s Clinical Practice Updates Committee, which pored through studies published through July 2016 in the PubMed, EMbase, and Cochrane library databases. Expert opinions and quality assessments on each study contributed to forming these best practice statements.

“In sum, the best current strategies for mitigating the potential risks of long-term PPIs are to avoid prescribing them when they are not indicated and to reduce them to their minimum dose when they are indicated,” Dr. Freedberg and his colleagues concluded.

The researchers did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Onlay mesh with adhesive just as safe as sublay route

While using sublay mesh continues to be standard practice when performing ventral hernia repair (VHR), a recent study shows that using onlay mesh placement with adhesive can be just as safe, at least in the short term.

“While the use of mesh during VHR is well accepted, the ideal location of mesh placement remains heavily debated,” wrote the study’s authors, adding that the “paucity of high-level data has led the choice of mesh location to reside primarily on the preference of the surgeon rather than grounded in clinical outcomes.”

The investigators identified patients in the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative national registry who were undergoing open, elective VHR and had clean wounds and a wound class I designation based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines at any point between January 2013 and January 2016. A total of 1,854 individuals were ultimately selected for inclusion in the study and were divided into two groups: one that received traditional VHR with sublay mesh and one that received onlay mesh with adhesive.

All subjects’ data were analyzed within 30 days for any adverse events related to the wounds from the surgery. These events were surgical site infections, surgical site occurrences – which could include an infection and any skin or soft tissue ischemia, necrosis, or other events – and surgical site occurrences that required procedural intervention, which were defined as any occurrences that required “opening of the wound, wound debridement, suture excision, percutaneous drainage, or partial or complete mesh removal.”

The sublay cohort numbered 1,761 (95.0%), compared with 93 (5.0%) who received the onlay technique. There was no significant difference found in the rate of 30-day adverse incidents between the two cohorts. For surgical site infections, the sublay cohort rate was 2.9%, while the onlay cohort had a 5.5% rate (P = .30). Surgical site occurrences happened in 15.2% of sublay patients versus 7.7% of those in the other group (P = .08), while surgical site occurrences that required procedural intervention were 8.2% in sublay patients but 5.5% in onlay patients (P = .42).

While both approaches fared similarly in terms of comorbidities and average Ventral Hernia Working Group grade, the investigators recommend that “the Chevrel onlay technique be used in nonobese patients without significant comorbidities, with moderate hernia defects, and whose abdominal wall vasculatures are without risk of compromise.” The data were generalizable because of the number of surgeons performing VHR and because the data sample allowed the investigators to control for the hernia width, defect size, and patient comorbidities this case, leading to this conclusion.

“Additional studies are needed to determine the long-term benefits of both approaches with respect to mesh infection rates and hernia recurrence rates, as well as the ideal mesh location for ventral hernia repairs in higher-risk patients,” the authors concluded.

No funding source was disclosed for this study. The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

While using sublay mesh continues to be standard practice when performing ventral hernia repair (VHR), a recent study shows that using onlay mesh placement with adhesive can be just as safe, at least in the short term.

“While the use of mesh during VHR is well accepted, the ideal location of mesh placement remains heavily debated,” wrote the study’s authors, adding that the “paucity of high-level data has led the choice of mesh location to reside primarily on the preference of the surgeon rather than grounded in clinical outcomes.”

The investigators identified patients in the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative national registry who were undergoing open, elective VHR and had clean wounds and a wound class I designation based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines at any point between January 2013 and January 2016. A total of 1,854 individuals were ultimately selected for inclusion in the study and were divided into two groups: one that received traditional VHR with sublay mesh and one that received onlay mesh with adhesive.

All subjects’ data were analyzed within 30 days for any adverse events related to the wounds from the surgery. These events were surgical site infections, surgical site occurrences – which could include an infection and any skin or soft tissue ischemia, necrosis, or other events – and surgical site occurrences that required procedural intervention, which were defined as any occurrences that required “opening of the wound, wound debridement, suture excision, percutaneous drainage, or partial or complete mesh removal.”

The sublay cohort numbered 1,761 (95.0%), compared with 93 (5.0%) who received the onlay technique. There was no significant difference found in the rate of 30-day adverse incidents between the two cohorts. For surgical site infections, the sublay cohort rate was 2.9%, while the onlay cohort had a 5.5% rate (P = .30). Surgical site occurrences happened in 15.2% of sublay patients versus 7.7% of those in the other group (P = .08), while surgical site occurrences that required procedural intervention were 8.2% in sublay patients but 5.5% in onlay patients (P = .42).

While both approaches fared similarly in terms of comorbidities and average Ventral Hernia Working Group grade, the investigators recommend that “the Chevrel onlay technique be used in nonobese patients without significant comorbidities, with moderate hernia defects, and whose abdominal wall vasculatures are without risk of compromise.” The data were generalizable because of the number of surgeons performing VHR and because the data sample allowed the investigators to control for the hernia width, defect size, and patient comorbidities this case, leading to this conclusion.

“Additional studies are needed to determine the long-term benefits of both approaches with respect to mesh infection rates and hernia recurrence rates, as well as the ideal mesh location for ventral hernia repairs in higher-risk patients,” the authors concluded.

No funding source was disclosed for this study. The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

While using sublay mesh continues to be standard practice when performing ventral hernia repair (VHR), a recent study shows that using onlay mesh placement with adhesive can be just as safe, at least in the short term.

“While the use of mesh during VHR is well accepted, the ideal location of mesh placement remains heavily debated,” wrote the study’s authors, adding that the “paucity of high-level data has led the choice of mesh location to reside primarily on the preference of the surgeon rather than grounded in clinical outcomes.”

The investigators identified patients in the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative national registry who were undergoing open, elective VHR and had clean wounds and a wound class I designation based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines at any point between January 2013 and January 2016. A total of 1,854 individuals were ultimately selected for inclusion in the study and were divided into two groups: one that received traditional VHR with sublay mesh and one that received onlay mesh with adhesive.

All subjects’ data were analyzed within 30 days for any adverse events related to the wounds from the surgery. These events were surgical site infections, surgical site occurrences – which could include an infection and any skin or soft tissue ischemia, necrosis, or other events – and surgical site occurrences that required procedural intervention, which were defined as any occurrences that required “opening of the wound, wound debridement, suture excision, percutaneous drainage, or partial or complete mesh removal.”

The sublay cohort numbered 1,761 (95.0%), compared with 93 (5.0%) who received the onlay technique. There was no significant difference found in the rate of 30-day adverse incidents between the two cohorts. For surgical site infections, the sublay cohort rate was 2.9%, while the onlay cohort had a 5.5% rate (P = .30). Surgical site occurrences happened in 15.2% of sublay patients versus 7.7% of those in the other group (P = .08), while surgical site occurrences that required procedural intervention were 8.2% in sublay patients but 5.5% in onlay patients (P = .42).

While both approaches fared similarly in terms of comorbidities and average Ventral Hernia Working Group grade, the investigators recommend that “the Chevrel onlay technique be used in nonobese patients without significant comorbidities, with moderate hernia defects, and whose abdominal wall vasculatures are without risk of compromise.” The data were generalizable because of the number of surgeons performing VHR and because the data sample allowed the investigators to control for the hernia width, defect size, and patient comorbidities this case, leading to this conclusion.

“Additional studies are needed to determine the long-term benefits of both approaches with respect to mesh infection rates and hernia recurrence rates, as well as the ideal mesh location for ventral hernia repairs in higher-risk patients,” the authors concluded.

No funding source was disclosed for this study. The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: No significant differences were found between onlay and sublay mesh VHR patients in terms of surgical site infection (P = .30), surgical site occurrences (P = .08), and surgical site occurrences that required intervention (P = .42).

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of 1,854 VHR patients between January 2013 and January 2016.

Disclosures: No funding source disclosed. Authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FDA clears procalcitonin test to hone antibiotic use in LRTI, sepsis

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared the expanded use of a procalcitonin test to help determine antibiotic use in patients with lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI) and sepsis.

The Vidas Brahms PCT Assay (bioMérieux) uses procalcitonin levels to determine whether a patient with a lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) should begin or remain on antibiotics and when antibiotics should be withdrawn in a patient with sepsis.

The test will be used primarily in hospital settings and emergency departments, according to the FDA. Test levels that are high levels suggest bacterial infection and the need for antibiotics while low levels indicate viral or noninfectious processes. However, concerns exist regarding false-positive or false-negative test results, which can prompt clinicians to prematurely stop or unnecessarily continue an antibiotic regimen in certain patients.

“Health care providers should not rely solely on PCT test results when making treatment decisions but should interpret test results in the context of a patient’s clinical status and other laboratory results,” according to the FDA statement.

The expanded use of the test was approved based on promising data from clinical trials that was presented at an FDA advisory committee meeting in November 2016. The Vidas Brahms test was already approved by the FDA for use in determining a patient’s risk of dying from sepsis. The test was cleared via the FDA 510(k) regulatory pathway, which is meant for tests or devices for which there is already something similar on the market.

Support for the test’s expanded usage comes from published prospective, randomized clinical trials that compared PCT-guided therapy with standard therapy. In those studies, patients who had received PCT-guided therapy experienced significant decreases in antibiotic use without significant affects to their safety.

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared the expanded use of a procalcitonin test to help determine antibiotic use in patients with lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI) and sepsis.

The Vidas Brahms PCT Assay (bioMérieux) uses procalcitonin levels to determine whether a patient with a lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) should begin or remain on antibiotics and when antibiotics should be withdrawn in a patient with sepsis.

The test will be used primarily in hospital settings and emergency departments, according to the FDA. Test levels that are high levels suggest bacterial infection and the need for antibiotics while low levels indicate viral or noninfectious processes. However, concerns exist regarding false-positive or false-negative test results, which can prompt clinicians to prematurely stop or unnecessarily continue an antibiotic regimen in certain patients.

“Health care providers should not rely solely on PCT test results when making treatment decisions but should interpret test results in the context of a patient’s clinical status and other laboratory results,” according to the FDA statement.

The expanded use of the test was approved based on promising data from clinical trials that was presented at an FDA advisory committee meeting in November 2016. The Vidas Brahms test was already approved by the FDA for use in determining a patient’s risk of dying from sepsis. The test was cleared via the FDA 510(k) regulatory pathway, which is meant for tests or devices for which there is already something similar on the market.

Support for the test’s expanded usage comes from published prospective, randomized clinical trials that compared PCT-guided therapy with standard therapy. In those studies, patients who had received PCT-guided therapy experienced significant decreases in antibiotic use without significant affects to their safety.

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared the expanded use of a procalcitonin test to help determine antibiotic use in patients with lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI) and sepsis.

The Vidas Brahms PCT Assay (bioMérieux) uses procalcitonin levels to determine whether a patient with a lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) should begin or remain on antibiotics and when antibiotics should be withdrawn in a patient with sepsis.

The test will be used primarily in hospital settings and emergency departments, according to the FDA. Test levels that are high levels suggest bacterial infection and the need for antibiotics while low levels indicate viral or noninfectious processes. However, concerns exist regarding false-positive or false-negative test results, which can prompt clinicians to prematurely stop or unnecessarily continue an antibiotic regimen in certain patients.

“Health care providers should not rely solely on PCT test results when making treatment decisions but should interpret test results in the context of a patient’s clinical status and other laboratory results,” according to the FDA statement.

The expanded use of the test was approved based on promising data from clinical trials that was presented at an FDA advisory committee meeting in November 2016. The Vidas Brahms test was already approved by the FDA for use in determining a patient’s risk of dying from sepsis. The test was cleared via the FDA 510(k) regulatory pathway, which is meant for tests or devices for which there is already something similar on the market.

Support for the test’s expanded usage comes from published prospective, randomized clinical trials that compared PCT-guided therapy with standard therapy. In those studies, patients who had received PCT-guided therapy experienced significant decreases in antibiotic use without significant affects to their safety.

Zika vaccine development expected to last through 2020

Progress continues to be made on creating a Zika vaccine, but taking any of the current candidates all the way through clinical trials and into production could take another few years, according to the latest information presented at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

“As we all know, there is no vaccine for Zika, but there are a number of vaccines that have been developed over the last century or so for other flaviviruses, [such as] dengue, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, [West Nile], and we know a great deal about flaviviruses in general and the pathology that they have,” explained Gerald R. Kovacs, PhD, of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA). “What we’re doing is using our lessons learned and working with the epidemiologists, with the clinicians, with the nonclinical development people, and using those lessons to develop new vaccines for Zika.”

By next year, the second aim should begin to take shape, which will be the deployment of available vaccines under an appropriate regulatory mechanism to U.S. populations at high risk of exposure.

Finally, by 2020, Dr. Kovacs explained that the government hopes to be partnering with industry to commercialize a Zika vaccine and make it available for broad distribution.

The vaccines being looked at include an inactivated whole-virus vaccine, a live attenuated vaccine that utilizes flavichimeras, a recombinant vaccine, and nucleic acid vaccines, including DNA and mRNA varieties. While each have their pros and cons, only the inactivated whole-virus and live attenuated virus vaccines have licensed human flavivirus vaccines already available for protection against Japanese encephalitis, tick-borne encephalitis, yellow fever, and dengue.

The Zika Purified Inactivated Vaccine (ZPIV) has two candidates in “advanced development,” one by Sanofi Pasteur and the other by Takeda. Currently, the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases are conducting phase I clinical trials on both ZPIV candidates to determine their safety and immunogenicity profiles and gathering information on regimen, dosing, and prior flavi immunity. ZPIV has already proven to be fully protective in mice and nonhuman primates. Both the Sanofi and Takeda ZPIVs are expected to enter phase II testing by the middle of next year, and phase III testing at some point in 2019 or 2020.

“Human challenge was discussed at a consultation that the [National Institutes of Health] held a couple of months ago [and] in a nutshell, what the committee found was that there isn’t sufficient information right now on Zika relative to its pathology and how it’s transmitted from humans to humans to support a human clinical study at this time,” said Dr. Kovacs. “But they will, as we accrue more information about this disease, revisit the potential of doing this type of study.”

Dr. Kovacs also highlighted the need for manufacturers to stay in the game as long as possible, urging them not to be discouraged by dwindling interest and funding regarding the Zika vaccine initiative.

“We can develop as many vaccines as possible, but what’s necessary is for these manufacturers to stay in for the long haul,” he explained. “With cuts in funding and less and less enthusiasm for Zika, it becomes challenging for the U.S. government to continue to engage with manufacturers on these types of products [but] we hope that all of our partners will continue on their endeavors with us, but we can’t guarantee that.”

Dr. Kovacs disclosed that he is a consultant for BARDA within the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response in the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and that he was speaking at the meeting on behalf of the organization.

Progress continues to be made on creating a Zika vaccine, but taking any of the current candidates all the way through clinical trials and into production could take another few years, according to the latest information presented at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

“As we all know, there is no vaccine for Zika, but there are a number of vaccines that have been developed over the last century or so for other flaviviruses, [such as] dengue, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, [West Nile], and we know a great deal about flaviviruses in general and the pathology that they have,” explained Gerald R. Kovacs, PhD, of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA). “What we’re doing is using our lessons learned and working with the epidemiologists, with the clinicians, with the nonclinical development people, and using those lessons to develop new vaccines for Zika.”

By next year, the second aim should begin to take shape, which will be the deployment of available vaccines under an appropriate regulatory mechanism to U.S. populations at high risk of exposure.

Finally, by 2020, Dr. Kovacs explained that the government hopes to be partnering with industry to commercialize a Zika vaccine and make it available for broad distribution.

The vaccines being looked at include an inactivated whole-virus vaccine, a live attenuated vaccine that utilizes flavichimeras, a recombinant vaccine, and nucleic acid vaccines, including DNA and mRNA varieties. While each have their pros and cons, only the inactivated whole-virus and live attenuated virus vaccines have licensed human flavivirus vaccines already available for protection against Japanese encephalitis, tick-borne encephalitis, yellow fever, and dengue.

The Zika Purified Inactivated Vaccine (ZPIV) has two candidates in “advanced development,” one by Sanofi Pasteur and the other by Takeda. Currently, the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases are conducting phase I clinical trials on both ZPIV candidates to determine their safety and immunogenicity profiles and gathering information on regimen, dosing, and prior flavi immunity. ZPIV has already proven to be fully protective in mice and nonhuman primates. Both the Sanofi and Takeda ZPIVs are expected to enter phase II testing by the middle of next year, and phase III testing at some point in 2019 or 2020.

“Human challenge was discussed at a consultation that the [National Institutes of Health] held a couple of months ago [and] in a nutshell, what the committee found was that there isn’t sufficient information right now on Zika relative to its pathology and how it’s transmitted from humans to humans to support a human clinical study at this time,” said Dr. Kovacs. “But they will, as we accrue more information about this disease, revisit the potential of doing this type of study.”

Dr. Kovacs also highlighted the need for manufacturers to stay in the game as long as possible, urging them not to be discouraged by dwindling interest and funding regarding the Zika vaccine initiative.

“We can develop as many vaccines as possible, but what’s necessary is for these manufacturers to stay in for the long haul,” he explained. “With cuts in funding and less and less enthusiasm for Zika, it becomes challenging for the U.S. government to continue to engage with manufacturers on these types of products [but] we hope that all of our partners will continue on their endeavors with us, but we can’t guarantee that.”

Dr. Kovacs disclosed that he is a consultant for BARDA within the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response in the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and that he was speaking at the meeting on behalf of the organization.

Progress continues to be made on creating a Zika vaccine, but taking any of the current candidates all the way through clinical trials and into production could take another few years, according to the latest information presented at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

“As we all know, there is no vaccine for Zika, but there are a number of vaccines that have been developed over the last century or so for other flaviviruses, [such as] dengue, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, [West Nile], and we know a great deal about flaviviruses in general and the pathology that they have,” explained Gerald R. Kovacs, PhD, of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA). “What we’re doing is using our lessons learned and working with the epidemiologists, with the clinicians, with the nonclinical development people, and using those lessons to develop new vaccines for Zika.”

By next year, the second aim should begin to take shape, which will be the deployment of available vaccines under an appropriate regulatory mechanism to U.S. populations at high risk of exposure.

Finally, by 2020, Dr. Kovacs explained that the government hopes to be partnering with industry to commercialize a Zika vaccine and make it available for broad distribution.

The vaccines being looked at include an inactivated whole-virus vaccine, a live attenuated vaccine that utilizes flavichimeras, a recombinant vaccine, and nucleic acid vaccines, including DNA and mRNA varieties. While each have their pros and cons, only the inactivated whole-virus and live attenuated virus vaccines have licensed human flavivirus vaccines already available for protection against Japanese encephalitis, tick-borne encephalitis, yellow fever, and dengue.

The Zika Purified Inactivated Vaccine (ZPIV) has two candidates in “advanced development,” one by Sanofi Pasteur and the other by Takeda. Currently, the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases are conducting phase I clinical trials on both ZPIV candidates to determine their safety and immunogenicity profiles and gathering information on regimen, dosing, and prior flavi immunity. ZPIV has already proven to be fully protective in mice and nonhuman primates. Both the Sanofi and Takeda ZPIVs are expected to enter phase II testing by the middle of next year, and phase III testing at some point in 2019 or 2020.

“Human challenge was discussed at a consultation that the [National Institutes of Health] held a couple of months ago [and] in a nutshell, what the committee found was that there isn’t sufficient information right now on Zika relative to its pathology and how it’s transmitted from humans to humans to support a human clinical study at this time,” said Dr. Kovacs. “But they will, as we accrue more information about this disease, revisit the potential of doing this type of study.”

Dr. Kovacs also highlighted the need for manufacturers to stay in the game as long as possible, urging them not to be discouraged by dwindling interest and funding regarding the Zika vaccine initiative.

“We can develop as many vaccines as possible, but what’s necessary is for these manufacturers to stay in for the long haul,” he explained. “With cuts in funding and less and less enthusiasm for Zika, it becomes challenging for the U.S. government to continue to engage with manufacturers on these types of products [but] we hope that all of our partners will continue on their endeavors with us, but we can’t guarantee that.”

Dr. Kovacs disclosed that he is a consultant for BARDA within the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response in the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and that he was speaking at the meeting on behalf of the organization.

Eliminating tap water consumption may prevent M. abscessus outbreaks

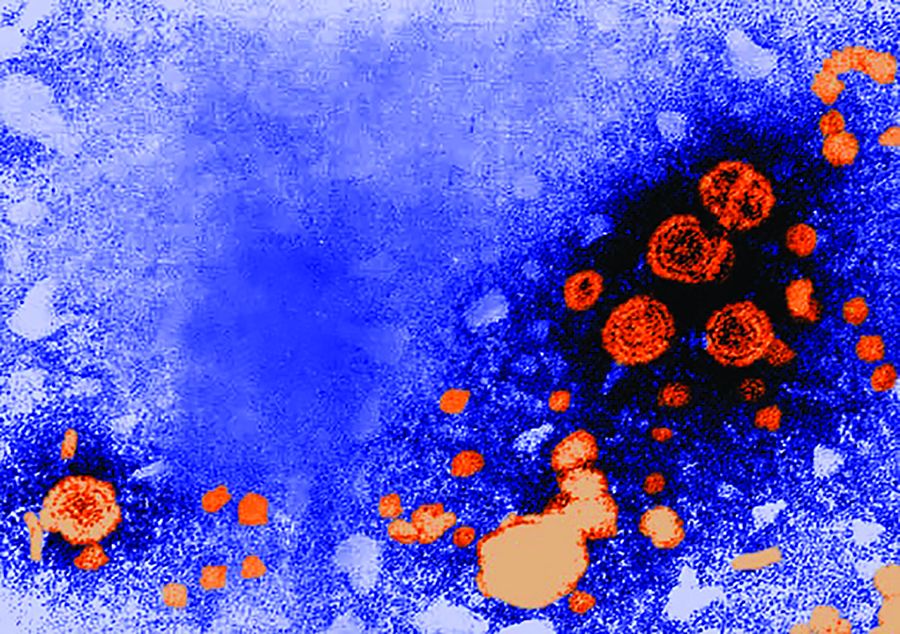

Abstaining from the consumption of tap water at health care facilities can dramatically reduce the risk of Mycobacterium abscessus infections among patients and staff, according to a new study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

“Outbreaks of [M. abscessus] and other rapidly growing mycobacteria are common and have been associated with colonized plumbing systems in commercial buildings and health care facilities,” wrote the authors, led by Arthur W. Baker, MD, MPH, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., adding that “Infections due to M. abscessus are difficult to diagnose and typically require months of therapy using multiple antibiotics” (Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Jan 10. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw877).

Phase 2 took place from December 2014 through June 2015; in between Phase 1 and Phase 2, tap water abstention was implemented to protect patients deemed high risk, such as those with lung transplants. Of the 71 infections that occurred during Phase 1, 39 (55%) were lung transplant patients, while 9 (13%) were in those who had a recent cardiac surgery, 5 (7%) had cancer, and 5 (7%) had hematopoietic stem cell transplants. Incidence rates decreased substantially, back to their baseline levels, and further measures were used to completely resolve the outbreak.

“Primary interventions included institution of an inpatient sterile water protocol for high-risk patients, implementation of a protocol for enhanced disinfection and sterile water use for [heater-cooler units] of [cardiopulmonary bypass] machines, and water engineering changes designed to decrease NTM [nontuberculous mycobacteria] burden in the plumbing system,” the authors explained. “Other health care facilities, particularly those with endemic NTM or newly constructed patient care facilities, should consider similar multifaceted strategies to improve water safety and decrease risk of health care–associated infection from NTM.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health’s Transplant Infectious Disease Interdisciplinary Research Training Grant. Dr. Baker and his coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Abstaining from the consumption of tap water at health care facilities can dramatically reduce the risk of Mycobacterium abscessus infections among patients and staff, according to a new study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

“Outbreaks of [M. abscessus] and other rapidly growing mycobacteria are common and have been associated with colonized plumbing systems in commercial buildings and health care facilities,” wrote the authors, led by Arthur W. Baker, MD, MPH, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., adding that “Infections due to M. abscessus are difficult to diagnose and typically require months of therapy using multiple antibiotics” (Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Jan 10. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw877).

Phase 2 took place from December 2014 through June 2015; in between Phase 1 and Phase 2, tap water abstention was implemented to protect patients deemed high risk, such as those with lung transplants. Of the 71 infections that occurred during Phase 1, 39 (55%) were lung transplant patients, while 9 (13%) were in those who had a recent cardiac surgery, 5 (7%) had cancer, and 5 (7%) had hematopoietic stem cell transplants. Incidence rates decreased substantially, back to their baseline levels, and further measures were used to completely resolve the outbreak.

“Primary interventions included institution of an inpatient sterile water protocol for high-risk patients, implementation of a protocol for enhanced disinfection and sterile water use for [heater-cooler units] of [cardiopulmonary bypass] machines, and water engineering changes designed to decrease NTM [nontuberculous mycobacteria] burden in the plumbing system,” the authors explained. “Other health care facilities, particularly those with endemic NTM or newly constructed patient care facilities, should consider similar multifaceted strategies to improve water safety and decrease risk of health care–associated infection from NTM.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health’s Transplant Infectious Disease Interdisciplinary Research Training Grant. Dr. Baker and his coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Abstaining from the consumption of tap water at health care facilities can dramatically reduce the risk of Mycobacterium abscessus infections among patients and staff, according to a new study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

“Outbreaks of [M. abscessus] and other rapidly growing mycobacteria are common and have been associated with colonized plumbing systems in commercial buildings and health care facilities,” wrote the authors, led by Arthur W. Baker, MD, MPH, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., adding that “Infections due to M. abscessus are difficult to diagnose and typically require months of therapy using multiple antibiotics” (Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Jan 10. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw877).

Phase 2 took place from December 2014 through June 2015; in between Phase 1 and Phase 2, tap water abstention was implemented to protect patients deemed high risk, such as those with lung transplants. Of the 71 infections that occurred during Phase 1, 39 (55%) were lung transplant patients, while 9 (13%) were in those who had a recent cardiac surgery, 5 (7%) had cancer, and 5 (7%) had hematopoietic stem cell transplants. Incidence rates decreased substantially, back to their baseline levels, and further measures were used to completely resolve the outbreak.

“Primary interventions included institution of an inpatient sterile water protocol for high-risk patients, implementation of a protocol for enhanced disinfection and sterile water use for [heater-cooler units] of [cardiopulmonary bypass] machines, and water engineering changes designed to decrease NTM [nontuberculous mycobacteria] burden in the plumbing system,” the authors explained. “Other health care facilities, particularly those with endemic NTM or newly constructed patient care facilities, should consider similar multifaceted strategies to improve water safety and decrease risk of health care–associated infection from NTM.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health’s Transplant Infectious Disease Interdisciplinary Research Training Grant. Dr. Baker and his coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point:

Major finding: After tap water avoidance, cases reduced from 3.0 cases per 10,000 patient-days to 0.7, the number at baseline pre-outbreak.

Data source: Prospective analysis of M. abscessus cases at a single institution during January 2013–December 2015.

Disclosures: Funded by a grant from the NIH. Authors reported no relevant disclosures.

ACIP approves minor changes to pediatric hepatitis B vaccine recommendations

Approval to changes of current recommendations for hepatitis B vaccinations for children were voted on by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

The 14-member panel voted to approve changes to existing language, which states that infants who are HBsAg negative with anti-HBs levels of less than 10 mIU/mL should be revaccinated with a second three-dose series and retested within 2 months of the series’ final dose. The approved proposal will change that language to state that these infants should receive only one dose, not the entire series of three. However, if anti-HBs levels remain lower than 10 mIU/mL after the one dose, the remaining two vaccinations should be administered, along with testing within 2 months of the final dose.