User login

Zika virus still calls for preparedness and vaccine development

Warming U.S. temperatures, the resumption of travel, and new knowledge about Zika’s long-term effects on children signal that Zika prevention and vaccine development should be on public health officials’, doctors’, and communities’ radar, even when community infection is not occurring.

“Although we haven’t seen confirmed Zika virus circulation in the continental United States or its territories for several years, it’s still something that we are closely monitoring, particularly as we move into the summer months,” Erin Staples, MD, PhD, medical epidemiologist at the Arboviral Diseases Branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Fort Collins, Colo., told this news organization.

“This is because cases are still being reported in other countries, particularly in South America. Travel to these places is increasing following the pandemic, leaving more potential for individuals who might have acquired the infection to come back and restart community transmission.”

How Zika might reemerge

The Aedes aegypti mosquito is the vector by which Zika spreads, and “during the COVID pandemic, these mosquitoes moved further north in the United States, into southern California, and were identified as far north as Washington, D.C.,” said Neil Silverman, MD, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology and director of the Infections in Pregnancy Program at UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles.

“On a population level, Americans have essentially no immunity to Zika from prior infection, and there is no vaccine yet approved. If individuals infected with Zika came into a U.S. region where the Aedes aegypti mosquito was present, that population could be very susceptible to infection spread and even another outbreak. This would be a confluence of bad circumstances, but that’s exactly what infectious disease specialists continue to be watchful about, especially because Zika is so dangerous for fetuses,” said Dr. Silverman.

How the public can prepare

The CDC recommends that pregnant women or women who plan to become pregnant avoid traveling to regions where there are currently outbreaks of Zika, but this is not the only way that individuals can protect themselves.

“The message we want to deliver to people is that in the United States, people are at risk for several mosquito-borne diseases every summer beyond just Zika,” Dr. Staples said. “It’s really important that people are instructed to make a habit of wearing EPA [U.S. Environmental Protection Agency)–registered insect repellents when they go outside. Right now, that is the single best tool that we have to prevent mosquito-borne diseases in the U.S.

“From a community standpoint, there are several emerging mosquito control methods that are being evaluated right now, such as genetic modification and irradiation of mosquitoes. These methods are aimed at producing sterile mosquitoes that are released into the wild to mate with the local mosquito population, which will render them infertile. This leads, over time, to suppression of the overall Aedes aegypti mosquito population – the main vector of Zika transmission,” said Dr. Staples.

Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, professor of medicine and associate chief of the division of HIV, infectious diseases, and global medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, encourages her patients to wear mosquito repellent but cautioned that “there’s no antiviral that you can take for Zika. Until we have a vaccine, the key to controlling/preventing Zika is controlling the mosquitoes that spread the virus.”

Vaccines

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) is currently investigating a variety of Zika vaccines, including a DNA-based vaccine, (phase 2), a purified inactivated virus vaccine (phase 1), live attenuated vaccines (phase 2), and mRNA vaccines (phase 2).

“I’m most excited about mRNA vaccines because they help patients produce a lot of proteins. The protein from a typical protein-adjuvant vaccine will break down, and patients can only raise an immune response to whatever proteins are left. On the other hand, mRNA vaccines provide the body [with] a recipe to make the protein from the pathogen in high amounts, so that a strong immune response can be raised for protection,” noted Dr. Gandhi.

Moderna’s mRNA-1893 vaccine was recently studied in a randomized, observer-blind, controlled, phase 1 trial among 120 adults in the United States and Puerto Rico, the results of which were published online in The Lancet. “The vaccine was found to be generally well tolerated with no serious adverse events considered related to vaccine. Furthermore, the vaccine was able to generate a potent immune response that was capable of neutralizing the virus in vitro,” said Brett Leav, MD, executive director of clinical development for public health vaccines at Moderna.

“Our mRNA platform technology ... can be very helpful against emerging pandemic threats, as we saw in response to COVID-19. What is unique in our approach is that if the genetic sequence of the virus is known, we can quickly generate vaccines to test for their capability to generate a functional immune response. In the case of the mRNA-1893 trial, the vaccine was developed with antigens that were present in the strain of virus circulating in 2016, but we could easily match whatever strain reemerges,” said Dr. Leav.

A phase 2 trial to confirm the dose of mRNA-1893 in a larger study population is underway.

Although it’s been demonstrated that Moderna’s mRNA vaccine is safe and effective, moving from a phase 2 to a phase 3 study presents a challenge, given the fact that currently, the disease burden from Zika is low. If an outbreak were to occur in the future, these mRNA vaccines could potentially be given emergency approval, as occurred during the COVID pandemic, according to Dr. Silverman.

If approved, provisionally or through a traditional route, the vaccine would “accelerate the ability to tamp down any further outbreaks, because vaccine-based immunity could be made available to a large portion of the population who were pregnant or planning a pregnancy, not just in the U.S. but also in these endemic areas,” said Dr. Silverman.

Takeaways from the last Zika outbreak

Practical steps such as mosquito eradication and development of vaccines are not the only takeaway from the recent Zika epidemics inside and outside the United States. A clearer picture of the short- and long-term stakes of the disease has emerged.

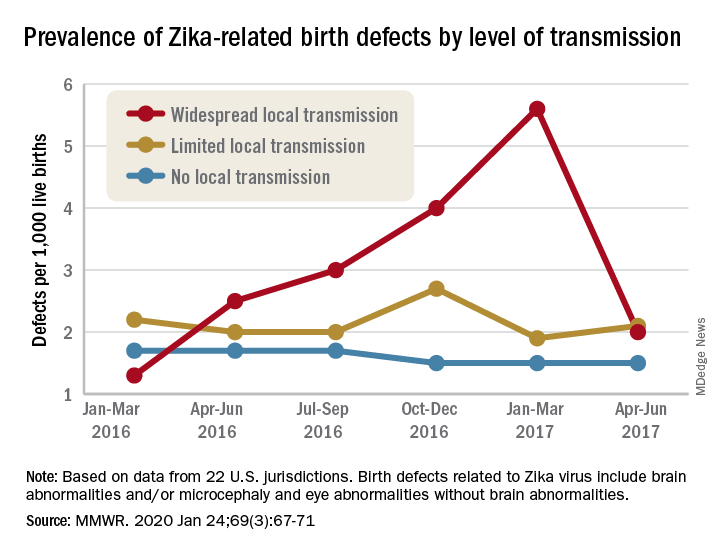

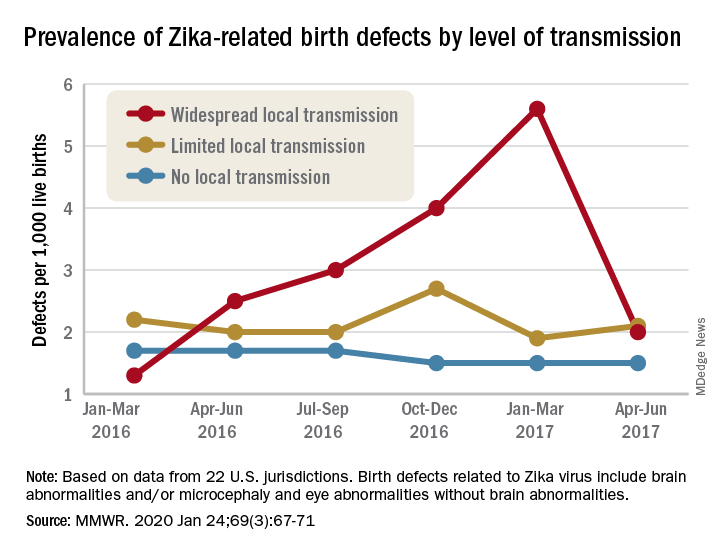

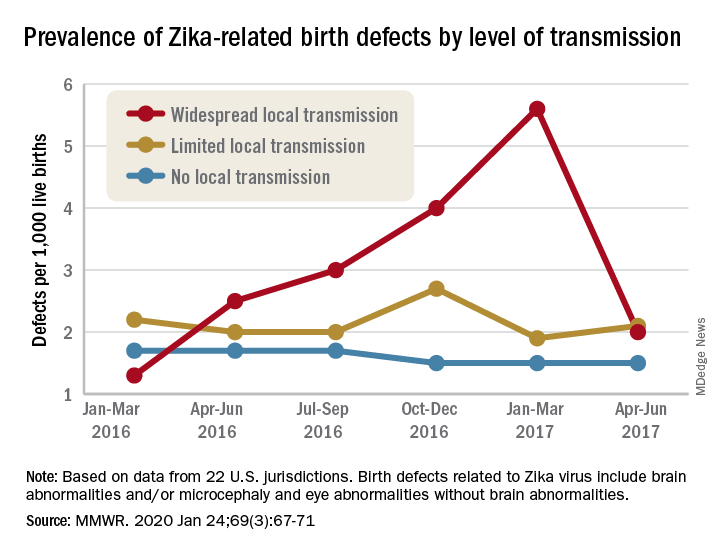

According to the CDC, most people who become infected with Zika experience only mild symptoms, such as fever, rash, headache, and muscle pain, but babies conceived by mothers infected with Zika are at risk for stillbirth, miscarriage, and microcephaly and other brain defects.

Although a pregnant woman who tests positive for Zika is in a very high-risk situation, “data show that only about 30% of mothers with Zika have a baby with birth defects. If a pregnant woman contracted Zika, what would happen is we would just do very close screening by ultrasound of the fetus. If microcephaly in utero or fetal brain defects were observed, then a mother would be counseled on her options,” said Dr. Gandhi.

Dr. Silverman noted that “new data on children who were exposed in utero and had normal exams, including head measurements when they were born, have raised concerns. In recently published long-term follow-up studies, even when children born to mothers infected with Zika during pregnancy had normal head growth at least 3 years after birth, they were still at risk for neurodevelopmental delay and behavioral disorders, including impact on coordination and executive function.

“This is another good reason to keep the potential risks of Zika active in the public’s consciousness and in public health planning.”

Dr. Silverman, Dr. Gandhi, and Dr. Staples have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Leav is an employee of Moderna and owns stock in the company.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Warming U.S. temperatures, the resumption of travel, and new knowledge about Zika’s long-term effects on children signal that Zika prevention and vaccine development should be on public health officials’, doctors’, and communities’ radar, even when community infection is not occurring.

“Although we haven’t seen confirmed Zika virus circulation in the continental United States or its territories for several years, it’s still something that we are closely monitoring, particularly as we move into the summer months,” Erin Staples, MD, PhD, medical epidemiologist at the Arboviral Diseases Branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Fort Collins, Colo., told this news organization.

“This is because cases are still being reported in other countries, particularly in South America. Travel to these places is increasing following the pandemic, leaving more potential for individuals who might have acquired the infection to come back and restart community transmission.”

How Zika might reemerge

The Aedes aegypti mosquito is the vector by which Zika spreads, and “during the COVID pandemic, these mosquitoes moved further north in the United States, into southern California, and were identified as far north as Washington, D.C.,” said Neil Silverman, MD, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology and director of the Infections in Pregnancy Program at UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles.

“On a population level, Americans have essentially no immunity to Zika from prior infection, and there is no vaccine yet approved. If individuals infected with Zika came into a U.S. region where the Aedes aegypti mosquito was present, that population could be very susceptible to infection spread and even another outbreak. This would be a confluence of bad circumstances, but that’s exactly what infectious disease specialists continue to be watchful about, especially because Zika is so dangerous for fetuses,” said Dr. Silverman.

How the public can prepare

The CDC recommends that pregnant women or women who plan to become pregnant avoid traveling to regions where there are currently outbreaks of Zika, but this is not the only way that individuals can protect themselves.

“The message we want to deliver to people is that in the United States, people are at risk for several mosquito-borne diseases every summer beyond just Zika,” Dr. Staples said. “It’s really important that people are instructed to make a habit of wearing EPA [U.S. Environmental Protection Agency)–registered insect repellents when they go outside. Right now, that is the single best tool that we have to prevent mosquito-borne diseases in the U.S.

“From a community standpoint, there are several emerging mosquito control methods that are being evaluated right now, such as genetic modification and irradiation of mosquitoes. These methods are aimed at producing sterile mosquitoes that are released into the wild to mate with the local mosquito population, which will render them infertile. This leads, over time, to suppression of the overall Aedes aegypti mosquito population – the main vector of Zika transmission,” said Dr. Staples.

Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, professor of medicine and associate chief of the division of HIV, infectious diseases, and global medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, encourages her patients to wear mosquito repellent but cautioned that “there’s no antiviral that you can take for Zika. Until we have a vaccine, the key to controlling/preventing Zika is controlling the mosquitoes that spread the virus.”

Vaccines

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) is currently investigating a variety of Zika vaccines, including a DNA-based vaccine, (phase 2), a purified inactivated virus vaccine (phase 1), live attenuated vaccines (phase 2), and mRNA vaccines (phase 2).

“I’m most excited about mRNA vaccines because they help patients produce a lot of proteins. The protein from a typical protein-adjuvant vaccine will break down, and patients can only raise an immune response to whatever proteins are left. On the other hand, mRNA vaccines provide the body [with] a recipe to make the protein from the pathogen in high amounts, so that a strong immune response can be raised for protection,” noted Dr. Gandhi.

Moderna’s mRNA-1893 vaccine was recently studied in a randomized, observer-blind, controlled, phase 1 trial among 120 adults in the United States and Puerto Rico, the results of which were published online in The Lancet. “The vaccine was found to be generally well tolerated with no serious adverse events considered related to vaccine. Furthermore, the vaccine was able to generate a potent immune response that was capable of neutralizing the virus in vitro,” said Brett Leav, MD, executive director of clinical development for public health vaccines at Moderna.

“Our mRNA platform technology ... can be very helpful against emerging pandemic threats, as we saw in response to COVID-19. What is unique in our approach is that if the genetic sequence of the virus is known, we can quickly generate vaccines to test for their capability to generate a functional immune response. In the case of the mRNA-1893 trial, the vaccine was developed with antigens that were present in the strain of virus circulating in 2016, but we could easily match whatever strain reemerges,” said Dr. Leav.

A phase 2 trial to confirm the dose of mRNA-1893 in a larger study population is underway.

Although it’s been demonstrated that Moderna’s mRNA vaccine is safe and effective, moving from a phase 2 to a phase 3 study presents a challenge, given the fact that currently, the disease burden from Zika is low. If an outbreak were to occur in the future, these mRNA vaccines could potentially be given emergency approval, as occurred during the COVID pandemic, according to Dr. Silverman.

If approved, provisionally or through a traditional route, the vaccine would “accelerate the ability to tamp down any further outbreaks, because vaccine-based immunity could be made available to a large portion of the population who were pregnant or planning a pregnancy, not just in the U.S. but also in these endemic areas,” said Dr. Silverman.

Takeaways from the last Zika outbreak

Practical steps such as mosquito eradication and development of vaccines are not the only takeaway from the recent Zika epidemics inside and outside the United States. A clearer picture of the short- and long-term stakes of the disease has emerged.

According to the CDC, most people who become infected with Zika experience only mild symptoms, such as fever, rash, headache, and muscle pain, but babies conceived by mothers infected with Zika are at risk for stillbirth, miscarriage, and microcephaly and other brain defects.

Although a pregnant woman who tests positive for Zika is in a very high-risk situation, “data show that only about 30% of mothers with Zika have a baby with birth defects. If a pregnant woman contracted Zika, what would happen is we would just do very close screening by ultrasound of the fetus. If microcephaly in utero or fetal brain defects were observed, then a mother would be counseled on her options,” said Dr. Gandhi.

Dr. Silverman noted that “new data on children who were exposed in utero and had normal exams, including head measurements when they were born, have raised concerns. In recently published long-term follow-up studies, even when children born to mothers infected with Zika during pregnancy had normal head growth at least 3 years after birth, they were still at risk for neurodevelopmental delay and behavioral disorders, including impact on coordination and executive function.

“This is another good reason to keep the potential risks of Zika active in the public’s consciousness and in public health planning.”

Dr. Silverman, Dr. Gandhi, and Dr. Staples have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Leav is an employee of Moderna and owns stock in the company.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Warming U.S. temperatures, the resumption of travel, and new knowledge about Zika’s long-term effects on children signal that Zika prevention and vaccine development should be on public health officials’, doctors’, and communities’ radar, even when community infection is not occurring.

“Although we haven’t seen confirmed Zika virus circulation in the continental United States or its territories for several years, it’s still something that we are closely monitoring, particularly as we move into the summer months,” Erin Staples, MD, PhD, medical epidemiologist at the Arboviral Diseases Branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Fort Collins, Colo., told this news organization.

“This is because cases are still being reported in other countries, particularly in South America. Travel to these places is increasing following the pandemic, leaving more potential for individuals who might have acquired the infection to come back and restart community transmission.”

How Zika might reemerge

The Aedes aegypti mosquito is the vector by which Zika spreads, and “during the COVID pandemic, these mosquitoes moved further north in the United States, into southern California, and were identified as far north as Washington, D.C.,” said Neil Silverman, MD, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology and director of the Infections in Pregnancy Program at UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles.

“On a population level, Americans have essentially no immunity to Zika from prior infection, and there is no vaccine yet approved. If individuals infected with Zika came into a U.S. region where the Aedes aegypti mosquito was present, that population could be very susceptible to infection spread and even another outbreak. This would be a confluence of bad circumstances, but that’s exactly what infectious disease specialists continue to be watchful about, especially because Zika is so dangerous for fetuses,” said Dr. Silverman.

How the public can prepare

The CDC recommends that pregnant women or women who plan to become pregnant avoid traveling to regions where there are currently outbreaks of Zika, but this is not the only way that individuals can protect themselves.

“The message we want to deliver to people is that in the United States, people are at risk for several mosquito-borne diseases every summer beyond just Zika,” Dr. Staples said. “It’s really important that people are instructed to make a habit of wearing EPA [U.S. Environmental Protection Agency)–registered insect repellents when they go outside. Right now, that is the single best tool that we have to prevent mosquito-borne diseases in the U.S.

“From a community standpoint, there are several emerging mosquito control methods that are being evaluated right now, such as genetic modification and irradiation of mosquitoes. These methods are aimed at producing sterile mosquitoes that are released into the wild to mate with the local mosquito population, which will render them infertile. This leads, over time, to suppression of the overall Aedes aegypti mosquito population – the main vector of Zika transmission,” said Dr. Staples.

Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, professor of medicine and associate chief of the division of HIV, infectious diseases, and global medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, encourages her patients to wear mosquito repellent but cautioned that “there’s no antiviral that you can take for Zika. Until we have a vaccine, the key to controlling/preventing Zika is controlling the mosquitoes that spread the virus.”

Vaccines

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) is currently investigating a variety of Zika vaccines, including a DNA-based vaccine, (phase 2), a purified inactivated virus vaccine (phase 1), live attenuated vaccines (phase 2), and mRNA vaccines (phase 2).

“I’m most excited about mRNA vaccines because they help patients produce a lot of proteins. The protein from a typical protein-adjuvant vaccine will break down, and patients can only raise an immune response to whatever proteins are left. On the other hand, mRNA vaccines provide the body [with] a recipe to make the protein from the pathogen in high amounts, so that a strong immune response can be raised for protection,” noted Dr. Gandhi.

Moderna’s mRNA-1893 vaccine was recently studied in a randomized, observer-blind, controlled, phase 1 trial among 120 adults in the United States and Puerto Rico, the results of which were published online in The Lancet. “The vaccine was found to be generally well tolerated with no serious adverse events considered related to vaccine. Furthermore, the vaccine was able to generate a potent immune response that was capable of neutralizing the virus in vitro,” said Brett Leav, MD, executive director of clinical development for public health vaccines at Moderna.

“Our mRNA platform technology ... can be very helpful against emerging pandemic threats, as we saw in response to COVID-19. What is unique in our approach is that if the genetic sequence of the virus is known, we can quickly generate vaccines to test for their capability to generate a functional immune response. In the case of the mRNA-1893 trial, the vaccine was developed with antigens that were present in the strain of virus circulating in 2016, but we could easily match whatever strain reemerges,” said Dr. Leav.

A phase 2 trial to confirm the dose of mRNA-1893 in a larger study population is underway.

Although it’s been demonstrated that Moderna’s mRNA vaccine is safe and effective, moving from a phase 2 to a phase 3 study presents a challenge, given the fact that currently, the disease burden from Zika is low. If an outbreak were to occur in the future, these mRNA vaccines could potentially be given emergency approval, as occurred during the COVID pandemic, according to Dr. Silverman.

If approved, provisionally or through a traditional route, the vaccine would “accelerate the ability to tamp down any further outbreaks, because vaccine-based immunity could be made available to a large portion of the population who were pregnant or planning a pregnancy, not just in the U.S. but also in these endemic areas,” said Dr. Silverman.

Takeaways from the last Zika outbreak

Practical steps such as mosquito eradication and development of vaccines are not the only takeaway from the recent Zika epidemics inside and outside the United States. A clearer picture of the short- and long-term stakes of the disease has emerged.

According to the CDC, most people who become infected with Zika experience only mild symptoms, such as fever, rash, headache, and muscle pain, but babies conceived by mothers infected with Zika are at risk for stillbirth, miscarriage, and microcephaly and other brain defects.

Although a pregnant woman who tests positive for Zika is in a very high-risk situation, “data show that only about 30% of mothers with Zika have a baby with birth defects. If a pregnant woman contracted Zika, what would happen is we would just do very close screening by ultrasound of the fetus. If microcephaly in utero or fetal brain defects were observed, then a mother would be counseled on her options,” said Dr. Gandhi.

Dr. Silverman noted that “new data on children who were exposed in utero and had normal exams, including head measurements when they were born, have raised concerns. In recently published long-term follow-up studies, even when children born to mothers infected with Zika during pregnancy had normal head growth at least 3 years after birth, they were still at risk for neurodevelopmental delay and behavioral disorders, including impact on coordination and executive function.

“This is another good reason to keep the potential risks of Zika active in the public’s consciousness and in public health planning.”

Dr. Silverman, Dr. Gandhi, and Dr. Staples have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Leav is an employee of Moderna and owns stock in the company.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Mosquitoes and the vicious circle that’s gone viral

These viruses want mosquitoes with good taste

Taste can be a pretty subjective sense. Not everyone agrees on what tastes good and what tastes bad. Most people would agree that freshly baked cookies taste good, but what about lima beans? And what about mosquitoes? What tastes good to a mosquito?

The answer? Blood. Blood tastes good to a mosquito. That really wasn’t a very hard question, was it? You did know the answer, didn’t you? They don’t care about cookies, and they certainly don’t care about lima beans. It’s blood that they love.

That brings us back to subjectivity, because it is possible for blood to taste even better. The secret ingredient is dengue … and Zika.

A study just published in Cell demonstrates that mice infected with dengue and Zika viruses release a volatile compound called acetophenone. “We found that flavivirus [like dengue and Zika] can utilize the increased release of acetophenone to help itself achieve its lifecycles more effectively by making their hosts more attractive to mosquito vectors,” senior author Gong Cheng of Tsinghua University, Beijing, said in a written statement.

How do they do it? The viruses, he explained, promote the proliferation of acetophenone-producing skin bacteria. “As a result, some bacteria overreplicate and produce more acetophenone. Suddenly, these sick individuals smell as delicious to mosquitoes as a tray of freshly baked cookies to a group of five-year-old children,” the statement said.

And how do you stop a group of tiny, flying 5-year-olds? That’s right, with acne medication. Really? You knew that one but not the blood one before? The investigators fed isotretinoin to the infected mice, which led to reduced acetophenone release from skin bacteria and made the animals no more attractive to the mosquitoes than their uninfected counterparts.

The investigators are planning to take the next step – feeding isotretinoin to people with dengue and Zika – having gotten the official fictional taste-test approval of celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay, who said, “You’re going to feed this #$^% to sick people? ARE YOU &%*$@#& KIDDING ME?”

Okay, so maybe approval isn’t quite the right word.

Welcome to bladders of the rich and famous!

Don’t you hate it when you’re driving out to your multimillion-dollar second home in the Hamptons and traffic is so bad you absolutely have to find a place to “rest” along the way? But wouldn’t you know it, there just isn’t anywhere to stop! Geez, how do we live?

That’s where David Shusterman, MD, a urologist in New York City and a true American hero, comes in. He’s identified a market and positioned himself as the king of both bladder surgery and “bladder Botox” for the wealthy New Yorkers who regularly make long journeys from the city out to their second homes in the Hamptons. Traffic has increased dramatically on Long Island roads in recent years, and the journey can now taking upward of 4 hours. Some people just can’t make it that long without a bathroom break, and there are very few places to stop along the way.

Dr. Shusterman understands the plight of the Hamptons vacationer, as he told Insider.com: “I can’t tell you how many arguments I personally get into – I’ve lost three friends because I’m the driver and refuse to stop for them.” A tragedy worthy of Shakespeare himself.

During the summer season, Dr. Shusterman performs about 10 prostate artery embolizations a week, an hour-long procedure that shrinks the prostate, which is great for 50- to 60-year-old men with enlarged prostates that cause more frequent bathroom trips. He also performs Botox injections into the bladder once or twice a week for women, which reduces the need to urinate for roughly 6 months. The perfect amount of time to get them through the summer season.

These procedures are sometimes covered by insurance but can cost as much as $20,000 if paid out of pocket. That’s a lot of money to us, but if you’re the sort of person who has a second home in the Hamptons, $20,000 is chump change, especially if it means you won’t have to go 2 entire minutes out of your way to use a gas-station bathroom. Then again, having seen a more than a few gas-station bathrooms in our time, maybe they have a point.

Ditch the apples. Go for the avocados

We’ve all heard about “an apple a day,” but instead of apples you might want to go with avocados.

Avocados are generally thought to be a healthy fat. A study just published in the Journal of the American Heart Association proves that they actually don’t do anything for your waistline but will work wonders on your cholesterol level. The study involved 923 participants who were considered overweight/obese split into two groups: One was asked to consume an avocado a day, and the other continued their usual diets and were asked to consume fewer than two avocados a month.

At the end of the 6 months, the researchers found total cholesterol decreased by an additional 2.9 mg/dL and LDL cholesterol by 2.5 mg/dL in those who ate one avocado every day, compared with the usual-diet group. And even though avocados have a lot of calories, there was no clinical evidence that it impacted weight gain or any cardiometabolic risk factors, according to a statement from Penn State University.

Avocados, then, can be considered a guilt-free food. The findings from this study suggest it can give a substantial boost to your overall quality of diet, in turn lessening your risk of developing type 2 diabetes and some cancers, Kristina Peterson, PhD, assistant professor of nutritional sciences at Texas Tech University, said in the statement.

So get creative with your avocado recipes. You can only eat so much guacamole.

Your nose knows a good friend for you

You’ve probably noticed how dogs sniff other dogs and people before becoming friends. It would be pretty comical if people did the same thing, right? Just walked up to strangers and started sniffing them like dogs?

Well, apparently humans do go by smell when it comes to making friends, and they prefer people who smell like them. Maybe you’ve noticed that your friends look like you, share your values, and think the same way as you. You’re probably right, seeing as previous research has pointed to this.

For the current study, done to show how smell affects human behavior, researchers recruited people who befriended each other quickly, before knowing much about each other. They assumed that the relationships between these same-sex, nonromantic “click friends” relied more on physiological traits, including smell. After collecting samples from the click friends, researchers used an eNose to scan chemical signatures. In another experiment, human volunteers sniffed samples to determine if any were similar. Both experiments showed that click friends had more similar smells than pairs of random people.

“This is not to say that we act like goats or shrews – humans likely rely on other, far more dominant cues in their social decision-making. Nevertheless, our study’s results do suggest that our nose plays a bigger role than previously thought in our choice of friends,” said senior author Noam Sobel, PhD, of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel.

Lead author Inbal Ravreby, a graduate student at the institute, put it this way: “These results imply that, as the saying goes, there is chemistry in social chemistry.”

These viruses want mosquitoes with good taste

Taste can be a pretty subjective sense. Not everyone agrees on what tastes good and what tastes bad. Most people would agree that freshly baked cookies taste good, but what about lima beans? And what about mosquitoes? What tastes good to a mosquito?

The answer? Blood. Blood tastes good to a mosquito. That really wasn’t a very hard question, was it? You did know the answer, didn’t you? They don’t care about cookies, and they certainly don’t care about lima beans. It’s blood that they love.

That brings us back to subjectivity, because it is possible for blood to taste even better. The secret ingredient is dengue … and Zika.

A study just published in Cell demonstrates that mice infected with dengue and Zika viruses release a volatile compound called acetophenone. “We found that flavivirus [like dengue and Zika] can utilize the increased release of acetophenone to help itself achieve its lifecycles more effectively by making their hosts more attractive to mosquito vectors,” senior author Gong Cheng of Tsinghua University, Beijing, said in a written statement.

How do they do it? The viruses, he explained, promote the proliferation of acetophenone-producing skin bacteria. “As a result, some bacteria overreplicate and produce more acetophenone. Suddenly, these sick individuals smell as delicious to mosquitoes as a tray of freshly baked cookies to a group of five-year-old children,” the statement said.

And how do you stop a group of tiny, flying 5-year-olds? That’s right, with acne medication. Really? You knew that one but not the blood one before? The investigators fed isotretinoin to the infected mice, which led to reduced acetophenone release from skin bacteria and made the animals no more attractive to the mosquitoes than their uninfected counterparts.

The investigators are planning to take the next step – feeding isotretinoin to people with dengue and Zika – having gotten the official fictional taste-test approval of celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay, who said, “You’re going to feed this #$^% to sick people? ARE YOU &%*$@#& KIDDING ME?”

Okay, so maybe approval isn’t quite the right word.

Welcome to bladders of the rich and famous!

Don’t you hate it when you’re driving out to your multimillion-dollar second home in the Hamptons and traffic is so bad you absolutely have to find a place to “rest” along the way? But wouldn’t you know it, there just isn’t anywhere to stop! Geez, how do we live?

That’s where David Shusterman, MD, a urologist in New York City and a true American hero, comes in. He’s identified a market and positioned himself as the king of both bladder surgery and “bladder Botox” for the wealthy New Yorkers who regularly make long journeys from the city out to their second homes in the Hamptons. Traffic has increased dramatically on Long Island roads in recent years, and the journey can now taking upward of 4 hours. Some people just can’t make it that long without a bathroom break, and there are very few places to stop along the way.

Dr. Shusterman understands the plight of the Hamptons vacationer, as he told Insider.com: “I can’t tell you how many arguments I personally get into – I’ve lost three friends because I’m the driver and refuse to stop for them.” A tragedy worthy of Shakespeare himself.

During the summer season, Dr. Shusterman performs about 10 prostate artery embolizations a week, an hour-long procedure that shrinks the prostate, which is great for 50- to 60-year-old men with enlarged prostates that cause more frequent bathroom trips. He also performs Botox injections into the bladder once or twice a week for women, which reduces the need to urinate for roughly 6 months. The perfect amount of time to get them through the summer season.

These procedures are sometimes covered by insurance but can cost as much as $20,000 if paid out of pocket. That’s a lot of money to us, but if you’re the sort of person who has a second home in the Hamptons, $20,000 is chump change, especially if it means you won’t have to go 2 entire minutes out of your way to use a gas-station bathroom. Then again, having seen a more than a few gas-station bathrooms in our time, maybe they have a point.

Ditch the apples. Go for the avocados

We’ve all heard about “an apple a day,” but instead of apples you might want to go with avocados.

Avocados are generally thought to be a healthy fat. A study just published in the Journal of the American Heart Association proves that they actually don’t do anything for your waistline but will work wonders on your cholesterol level. The study involved 923 participants who were considered overweight/obese split into two groups: One was asked to consume an avocado a day, and the other continued their usual diets and were asked to consume fewer than two avocados a month.

At the end of the 6 months, the researchers found total cholesterol decreased by an additional 2.9 mg/dL and LDL cholesterol by 2.5 mg/dL in those who ate one avocado every day, compared with the usual-diet group. And even though avocados have a lot of calories, there was no clinical evidence that it impacted weight gain or any cardiometabolic risk factors, according to a statement from Penn State University.

Avocados, then, can be considered a guilt-free food. The findings from this study suggest it can give a substantial boost to your overall quality of diet, in turn lessening your risk of developing type 2 diabetes and some cancers, Kristina Peterson, PhD, assistant professor of nutritional sciences at Texas Tech University, said in the statement.

So get creative with your avocado recipes. You can only eat so much guacamole.

Your nose knows a good friend for you

You’ve probably noticed how dogs sniff other dogs and people before becoming friends. It would be pretty comical if people did the same thing, right? Just walked up to strangers and started sniffing them like dogs?

Well, apparently humans do go by smell when it comes to making friends, and they prefer people who smell like them. Maybe you’ve noticed that your friends look like you, share your values, and think the same way as you. You’re probably right, seeing as previous research has pointed to this.

For the current study, done to show how smell affects human behavior, researchers recruited people who befriended each other quickly, before knowing much about each other. They assumed that the relationships between these same-sex, nonromantic “click friends” relied more on physiological traits, including smell. After collecting samples from the click friends, researchers used an eNose to scan chemical signatures. In another experiment, human volunteers sniffed samples to determine if any were similar. Both experiments showed that click friends had more similar smells than pairs of random people.

“This is not to say that we act like goats or shrews – humans likely rely on other, far more dominant cues in their social decision-making. Nevertheless, our study’s results do suggest that our nose plays a bigger role than previously thought in our choice of friends,” said senior author Noam Sobel, PhD, of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel.

Lead author Inbal Ravreby, a graduate student at the institute, put it this way: “These results imply that, as the saying goes, there is chemistry in social chemistry.”

These viruses want mosquitoes with good taste

Taste can be a pretty subjective sense. Not everyone agrees on what tastes good and what tastes bad. Most people would agree that freshly baked cookies taste good, but what about lima beans? And what about mosquitoes? What tastes good to a mosquito?

The answer? Blood. Blood tastes good to a mosquito. That really wasn’t a very hard question, was it? You did know the answer, didn’t you? They don’t care about cookies, and they certainly don’t care about lima beans. It’s blood that they love.

That brings us back to subjectivity, because it is possible for blood to taste even better. The secret ingredient is dengue … and Zika.

A study just published in Cell demonstrates that mice infected with dengue and Zika viruses release a volatile compound called acetophenone. “We found that flavivirus [like dengue and Zika] can utilize the increased release of acetophenone to help itself achieve its lifecycles more effectively by making their hosts more attractive to mosquito vectors,” senior author Gong Cheng of Tsinghua University, Beijing, said in a written statement.

How do they do it? The viruses, he explained, promote the proliferation of acetophenone-producing skin bacteria. “As a result, some bacteria overreplicate and produce more acetophenone. Suddenly, these sick individuals smell as delicious to mosquitoes as a tray of freshly baked cookies to a group of five-year-old children,” the statement said.

And how do you stop a group of tiny, flying 5-year-olds? That’s right, with acne medication. Really? You knew that one but not the blood one before? The investigators fed isotretinoin to the infected mice, which led to reduced acetophenone release from skin bacteria and made the animals no more attractive to the mosquitoes than their uninfected counterparts.

The investigators are planning to take the next step – feeding isotretinoin to people with dengue and Zika – having gotten the official fictional taste-test approval of celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay, who said, “You’re going to feed this #$^% to sick people? ARE YOU &%*$@#& KIDDING ME?”

Okay, so maybe approval isn’t quite the right word.

Welcome to bladders of the rich and famous!

Don’t you hate it when you’re driving out to your multimillion-dollar second home in the Hamptons and traffic is so bad you absolutely have to find a place to “rest” along the way? But wouldn’t you know it, there just isn’t anywhere to stop! Geez, how do we live?

That’s where David Shusterman, MD, a urologist in New York City and a true American hero, comes in. He’s identified a market and positioned himself as the king of both bladder surgery and “bladder Botox” for the wealthy New Yorkers who regularly make long journeys from the city out to their second homes in the Hamptons. Traffic has increased dramatically on Long Island roads in recent years, and the journey can now taking upward of 4 hours. Some people just can’t make it that long without a bathroom break, and there are very few places to stop along the way.

Dr. Shusterman understands the plight of the Hamptons vacationer, as he told Insider.com: “I can’t tell you how many arguments I personally get into – I’ve lost three friends because I’m the driver and refuse to stop for them.” A tragedy worthy of Shakespeare himself.

During the summer season, Dr. Shusterman performs about 10 prostate artery embolizations a week, an hour-long procedure that shrinks the prostate, which is great for 50- to 60-year-old men with enlarged prostates that cause more frequent bathroom trips. He also performs Botox injections into the bladder once or twice a week for women, which reduces the need to urinate for roughly 6 months. The perfect amount of time to get them through the summer season.

These procedures are sometimes covered by insurance but can cost as much as $20,000 if paid out of pocket. That’s a lot of money to us, but if you’re the sort of person who has a second home in the Hamptons, $20,000 is chump change, especially if it means you won’t have to go 2 entire minutes out of your way to use a gas-station bathroom. Then again, having seen a more than a few gas-station bathrooms in our time, maybe they have a point.

Ditch the apples. Go for the avocados

We’ve all heard about “an apple a day,” but instead of apples you might want to go with avocados.

Avocados are generally thought to be a healthy fat. A study just published in the Journal of the American Heart Association proves that they actually don’t do anything for your waistline but will work wonders on your cholesterol level. The study involved 923 participants who were considered overweight/obese split into two groups: One was asked to consume an avocado a day, and the other continued their usual diets and were asked to consume fewer than two avocados a month.

At the end of the 6 months, the researchers found total cholesterol decreased by an additional 2.9 mg/dL and LDL cholesterol by 2.5 mg/dL in those who ate one avocado every day, compared with the usual-diet group. And even though avocados have a lot of calories, there was no clinical evidence that it impacted weight gain or any cardiometabolic risk factors, according to a statement from Penn State University.

Avocados, then, can be considered a guilt-free food. The findings from this study suggest it can give a substantial boost to your overall quality of diet, in turn lessening your risk of developing type 2 diabetes and some cancers, Kristina Peterson, PhD, assistant professor of nutritional sciences at Texas Tech University, said in the statement.

So get creative with your avocado recipes. You can only eat so much guacamole.

Your nose knows a good friend for you

You’ve probably noticed how dogs sniff other dogs and people before becoming friends. It would be pretty comical if people did the same thing, right? Just walked up to strangers and started sniffing them like dogs?

Well, apparently humans do go by smell when it comes to making friends, and they prefer people who smell like them. Maybe you’ve noticed that your friends look like you, share your values, and think the same way as you. You’re probably right, seeing as previous research has pointed to this.

For the current study, done to show how smell affects human behavior, researchers recruited people who befriended each other quickly, before knowing much about each other. They assumed that the relationships between these same-sex, nonromantic “click friends” relied more on physiological traits, including smell. After collecting samples from the click friends, researchers used an eNose to scan chemical signatures. In another experiment, human volunteers sniffed samples to determine if any were similar. Both experiments showed that click friends had more similar smells than pairs of random people.

“This is not to say that we act like goats or shrews – humans likely rely on other, far more dominant cues in their social decision-making. Nevertheless, our study’s results do suggest that our nose plays a bigger role than previously thought in our choice of friends,” said senior author Noam Sobel, PhD, of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel.

Lead author Inbal Ravreby, a graduate student at the institute, put it this way: “These results imply that, as the saying goes, there is chemistry in social chemistry.”

Mosquitoes genetically modified to stop disease pass early test

As part of the test, scientists released nearly 5 million genetically engineered male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes over the course of 7 months in the Florida Keys.

Male mosquitoes don’t bite people, and these were also modified so they would transmit a gene to female offspring that causes them to die before they can reproduce. In theory, this means the population of A. aegypti mosquitoes would die off over time, so they wouldn’t spread diseases any more.

The goal of this pilot project in Florida was to see if these genetically modified male mosquitoes could successfully mate with females in the wild, and to confirm whether their female offspring would indeed die before they could reproduce. On both counts, the experiment was a success, Oxitec, the biotechnology company developing these engineered A. aegypti mosquitoes, said in a webinar.

More testing in Florida and California

Based on the results from this preliminary research, the Environmental Protection Agency has approved additional pilot projects in Florida and California, the company said in a statement.

“Given the growing health threat this mosquito poses across the U.S., we’re working to make this technology available and accessible,” Grey Frandsen, Oxitec’s chief executive, said in the statement. “These pilot programs, wherein we can demonstrate the technology’s effectiveness in different climate settings, will play an important role in doing so.”

A. aegypti mosquitoes can spread several serious infectious diseases to humans, including dengue, Zika, yellow fever and chikungunya, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Preliminary tests of the genetically modified mosquitoes weren’t designed to determine whether these engineered insects might stop the spread of these diseases. The goal of the initial tests was simply to see how reproduction played out once the genetically modified males were released.

The genetically engineered males successfully mated with females in the wild, the company reports. Scientists collected more than 22,000 eggs laid by these females from traps set out around the community in spots like flowerpots and trash cans.

In the lab, researchers confirmed that the female offspring from these pairings inherited a lethal gene designed to cause their death before adulthood. The lethal gene was transmitted to female offspring across multiple generations, scientists also found.

Many more trials would be needed before these genetically modified mosquitoes could be released in the wild on a larger scale – particularly because the tests done so far haven’t demonstrated that these engineered bugs can prevent the spread of infectious disease.

Releasing genetically modified A. aegypti mosquitoes into the wild won’t reduce the need for pesticides because most mosquitoes in the United States aren’t from this species.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

As part of the test, scientists released nearly 5 million genetically engineered male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes over the course of 7 months in the Florida Keys.

Male mosquitoes don’t bite people, and these were also modified so they would transmit a gene to female offspring that causes them to die before they can reproduce. In theory, this means the population of A. aegypti mosquitoes would die off over time, so they wouldn’t spread diseases any more.

The goal of this pilot project in Florida was to see if these genetically modified male mosquitoes could successfully mate with females in the wild, and to confirm whether their female offspring would indeed die before they could reproduce. On both counts, the experiment was a success, Oxitec, the biotechnology company developing these engineered A. aegypti mosquitoes, said in a webinar.

More testing in Florida and California

Based on the results from this preliminary research, the Environmental Protection Agency has approved additional pilot projects in Florida and California, the company said in a statement.

“Given the growing health threat this mosquito poses across the U.S., we’re working to make this technology available and accessible,” Grey Frandsen, Oxitec’s chief executive, said in the statement. “These pilot programs, wherein we can demonstrate the technology’s effectiveness in different climate settings, will play an important role in doing so.”

A. aegypti mosquitoes can spread several serious infectious diseases to humans, including dengue, Zika, yellow fever and chikungunya, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Preliminary tests of the genetically modified mosquitoes weren’t designed to determine whether these engineered insects might stop the spread of these diseases. The goal of the initial tests was simply to see how reproduction played out once the genetically modified males were released.

The genetically engineered males successfully mated with females in the wild, the company reports. Scientists collected more than 22,000 eggs laid by these females from traps set out around the community in spots like flowerpots and trash cans.

In the lab, researchers confirmed that the female offspring from these pairings inherited a lethal gene designed to cause their death before adulthood. The lethal gene was transmitted to female offspring across multiple generations, scientists also found.

Many more trials would be needed before these genetically modified mosquitoes could be released in the wild on a larger scale – particularly because the tests done so far haven’t demonstrated that these engineered bugs can prevent the spread of infectious disease.

Releasing genetically modified A. aegypti mosquitoes into the wild won’t reduce the need for pesticides because most mosquitoes in the United States aren’t from this species.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

As part of the test, scientists released nearly 5 million genetically engineered male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes over the course of 7 months in the Florida Keys.

Male mosquitoes don’t bite people, and these were also modified so they would transmit a gene to female offspring that causes them to die before they can reproduce. In theory, this means the population of A. aegypti mosquitoes would die off over time, so they wouldn’t spread diseases any more.

The goal of this pilot project in Florida was to see if these genetically modified male mosquitoes could successfully mate with females in the wild, and to confirm whether their female offspring would indeed die before they could reproduce. On both counts, the experiment was a success, Oxitec, the biotechnology company developing these engineered A. aegypti mosquitoes, said in a webinar.

More testing in Florida and California

Based on the results from this preliminary research, the Environmental Protection Agency has approved additional pilot projects in Florida and California, the company said in a statement.

“Given the growing health threat this mosquito poses across the U.S., we’re working to make this technology available and accessible,” Grey Frandsen, Oxitec’s chief executive, said in the statement. “These pilot programs, wherein we can demonstrate the technology’s effectiveness in different climate settings, will play an important role in doing so.”

A. aegypti mosquitoes can spread several serious infectious diseases to humans, including dengue, Zika, yellow fever and chikungunya, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Preliminary tests of the genetically modified mosquitoes weren’t designed to determine whether these engineered insects might stop the spread of these diseases. The goal of the initial tests was simply to see how reproduction played out once the genetically modified males were released.

The genetically engineered males successfully mated with females in the wild, the company reports. Scientists collected more than 22,000 eggs laid by these females from traps set out around the community in spots like flowerpots and trash cans.

In the lab, researchers confirmed that the female offspring from these pairings inherited a lethal gene designed to cause their death before adulthood. The lethal gene was transmitted to female offspring across multiple generations, scientists also found.

Many more trials would be needed before these genetically modified mosquitoes could be released in the wild on a larger scale – particularly because the tests done so far haven’t demonstrated that these engineered bugs can prevent the spread of infectious disease.

Releasing genetically modified A. aegypti mosquitoes into the wild won’t reduce the need for pesticides because most mosquitoes in the United States aren’t from this species.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Mortality 12 times higher in children with congenital Zika

About 80% of people infected with Zika virus show no symptoms, and that’s particularly problematic during pregnancy. The infection can cause birth defects and is the origin of numerous cases of microcephaly and other neurologic impairments.

The large amount of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Brazilian cities, in addition to social and political problems, facilitated the spread of Zika to the point that the country recorded its highest number of congenital Zika syndrome notifications from 2015 to 2018. Since then, researchers have investigated the extent of the problem.

One of the most compelling findings about the dramatic legacy of Zika in Brazil was published Feb. 24 in The New England Journal of Medicine: After tracking 11,481,215 children born alive in Brazil up to 36 months of age between the years 2015 and 2018, the researchers found that the mortality rate was about 12 times higher among children with congenital Zika syndrome in comparison to children without the syndrome. The study is the first to follow children with congenital Zika syndrome for 3 years and to report mortality in this group.

“This difference persisted throughout the first 3 years of life,” Enny S. Paixão, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and Fiocruz-Bahia’s Instituto Gonçalo Moniz, in Brazil, said in an interview.

At the end of the study period, the mortality rate was 52.6 deaths (95% confidence interval, 47.6-58.0) per 1,000 person-years among children with congenital Zika syndrome and 5.6 deaths (95% CI, 5.6-5.7) per 1,000 person-years among those without the syndrome. The mortality rate ratio among children with congenital Zika syndrome, compared with those without it, was 11.3 (95% CI, 10.2-12.4). Data analysis also showed that the 3,308 children with the syndrome were born to mothers who were younger and had fewer years of study when compared to the mothers of their 11,477,907 counterparts without the syndrome.

“If the children survived the first month of life, they had a greater chance of surviving during childhood, because the mortality rates drop,” said Dr. Paixão. “In children with congenital Zika syndrome, this rate also drops, but slowly. The more we stratified by period – neonatal, post neonatal, and the period from the first to the third year of life – the more we saw the relative risk increase. After the first year of life, children with the syndrome were almost 22 times more likely to die compared to children without it. It was hard to believe the data.” Dr. Paixão added that the mortality observed in this study is comparable with the findings of previous studies.

In addition to the large sample size – more than 11 million children – another unique aspect of the work was the comparison with healthy live births. “Previous studies didn’t have this comparison group,” Dr. said Paixão.

Perhaps the major challenge of the study, Dr. Paixão explained, was the fragmentation of the data. “In Brazil we have high-quality data systems, but they are not interconnected. We have a database with all live births, another with mortality records, and another with all children with congenital Zika syndrome. The first big challenge was putting all this information together.”

The solution found by the researchers was to use data linkage – bringing information about the same person from different data banks to create a richer dataset. Basically, they linked the data from the live births registry with the deaths that occurred in the studied age group plus around 18,000 children with congenital Zika syndrome. This was done, said Dr. Paixão, by choosing some identifying variables (such as mother’s name, address, and age) and using an algorithm that evaluates the probability that the “N” in one database is the same person in another database.

“This is expensive, complex, [and] involves super-powerful computers and a lot of researchers,” she said.

The impressive mortality data for children with congenital Zika syndrome obtained by the group of researchers made it inevitable to think about how the country should address this terrible legacy.

“The first and most important recommendation is that the country needs to invest in primary care, so that women don’t get Zika during pregnancy and children aren’t at risk of getting the syndrome,” said Dr. Paixão.

As for the affected population, she highlighted the need to deepen the understanding of the syndrome’s natural history to improve survival and quality of life of affected children and their families. One possibility that was recently discussed by the group of researchers is to carry out a study on the causes of hospitalization of children with the syndrome to develop appropriate protocols and procedures that reduce admissions and death in this population.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 80% of people infected with Zika virus show no symptoms, and that’s particularly problematic during pregnancy. The infection can cause birth defects and is the origin of numerous cases of microcephaly and other neurologic impairments.

The large amount of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Brazilian cities, in addition to social and political problems, facilitated the spread of Zika to the point that the country recorded its highest number of congenital Zika syndrome notifications from 2015 to 2018. Since then, researchers have investigated the extent of the problem.

One of the most compelling findings about the dramatic legacy of Zika in Brazil was published Feb. 24 in The New England Journal of Medicine: After tracking 11,481,215 children born alive in Brazil up to 36 months of age between the years 2015 and 2018, the researchers found that the mortality rate was about 12 times higher among children with congenital Zika syndrome in comparison to children without the syndrome. The study is the first to follow children with congenital Zika syndrome for 3 years and to report mortality in this group.

“This difference persisted throughout the first 3 years of life,” Enny S. Paixão, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and Fiocruz-Bahia’s Instituto Gonçalo Moniz, in Brazil, said in an interview.

At the end of the study period, the mortality rate was 52.6 deaths (95% confidence interval, 47.6-58.0) per 1,000 person-years among children with congenital Zika syndrome and 5.6 deaths (95% CI, 5.6-5.7) per 1,000 person-years among those without the syndrome. The mortality rate ratio among children with congenital Zika syndrome, compared with those without it, was 11.3 (95% CI, 10.2-12.4). Data analysis also showed that the 3,308 children with the syndrome were born to mothers who were younger and had fewer years of study when compared to the mothers of their 11,477,907 counterparts without the syndrome.

“If the children survived the first month of life, they had a greater chance of surviving during childhood, because the mortality rates drop,” said Dr. Paixão. “In children with congenital Zika syndrome, this rate also drops, but slowly. The more we stratified by period – neonatal, post neonatal, and the period from the first to the third year of life – the more we saw the relative risk increase. After the first year of life, children with the syndrome were almost 22 times more likely to die compared to children without it. It was hard to believe the data.” Dr. Paixão added that the mortality observed in this study is comparable with the findings of previous studies.

In addition to the large sample size – more than 11 million children – another unique aspect of the work was the comparison with healthy live births. “Previous studies didn’t have this comparison group,” Dr. said Paixão.

Perhaps the major challenge of the study, Dr. Paixão explained, was the fragmentation of the data. “In Brazil we have high-quality data systems, but they are not interconnected. We have a database with all live births, another with mortality records, and another with all children with congenital Zika syndrome. The first big challenge was putting all this information together.”

The solution found by the researchers was to use data linkage – bringing information about the same person from different data banks to create a richer dataset. Basically, they linked the data from the live births registry with the deaths that occurred in the studied age group plus around 18,000 children with congenital Zika syndrome. This was done, said Dr. Paixão, by choosing some identifying variables (such as mother’s name, address, and age) and using an algorithm that evaluates the probability that the “N” in one database is the same person in another database.

“This is expensive, complex, [and] involves super-powerful computers and a lot of researchers,” she said.

The impressive mortality data for children with congenital Zika syndrome obtained by the group of researchers made it inevitable to think about how the country should address this terrible legacy.

“The first and most important recommendation is that the country needs to invest in primary care, so that women don’t get Zika during pregnancy and children aren’t at risk of getting the syndrome,” said Dr. Paixão.

As for the affected population, she highlighted the need to deepen the understanding of the syndrome’s natural history to improve survival and quality of life of affected children and their families. One possibility that was recently discussed by the group of researchers is to carry out a study on the causes of hospitalization of children with the syndrome to develop appropriate protocols and procedures that reduce admissions and death in this population.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 80% of people infected with Zika virus show no symptoms, and that’s particularly problematic during pregnancy. The infection can cause birth defects and is the origin of numerous cases of microcephaly and other neurologic impairments.

The large amount of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Brazilian cities, in addition to social and political problems, facilitated the spread of Zika to the point that the country recorded its highest number of congenital Zika syndrome notifications from 2015 to 2018. Since then, researchers have investigated the extent of the problem.

One of the most compelling findings about the dramatic legacy of Zika in Brazil was published Feb. 24 in The New England Journal of Medicine: After tracking 11,481,215 children born alive in Brazil up to 36 months of age between the years 2015 and 2018, the researchers found that the mortality rate was about 12 times higher among children with congenital Zika syndrome in comparison to children without the syndrome. The study is the first to follow children with congenital Zika syndrome for 3 years and to report mortality in this group.

“This difference persisted throughout the first 3 years of life,” Enny S. Paixão, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and Fiocruz-Bahia’s Instituto Gonçalo Moniz, in Brazil, said in an interview.

At the end of the study period, the mortality rate was 52.6 deaths (95% confidence interval, 47.6-58.0) per 1,000 person-years among children with congenital Zika syndrome and 5.6 deaths (95% CI, 5.6-5.7) per 1,000 person-years among those without the syndrome. The mortality rate ratio among children with congenital Zika syndrome, compared with those without it, was 11.3 (95% CI, 10.2-12.4). Data analysis also showed that the 3,308 children with the syndrome were born to mothers who were younger and had fewer years of study when compared to the mothers of their 11,477,907 counterparts without the syndrome.

“If the children survived the first month of life, they had a greater chance of surviving during childhood, because the mortality rates drop,” said Dr. Paixão. “In children with congenital Zika syndrome, this rate also drops, but slowly. The more we stratified by period – neonatal, post neonatal, and the period from the first to the third year of life – the more we saw the relative risk increase. After the first year of life, children with the syndrome were almost 22 times more likely to die compared to children without it. It was hard to believe the data.” Dr. Paixão added that the mortality observed in this study is comparable with the findings of previous studies.

In addition to the large sample size – more than 11 million children – another unique aspect of the work was the comparison with healthy live births. “Previous studies didn’t have this comparison group,” Dr. said Paixão.

Perhaps the major challenge of the study, Dr. Paixão explained, was the fragmentation of the data. “In Brazil we have high-quality data systems, but they are not interconnected. We have a database with all live births, another with mortality records, and another with all children with congenital Zika syndrome. The first big challenge was putting all this information together.”

The solution found by the researchers was to use data linkage – bringing information about the same person from different data banks to create a richer dataset. Basically, they linked the data from the live births registry with the deaths that occurred in the studied age group plus around 18,000 children with congenital Zika syndrome. This was done, said Dr. Paixão, by choosing some identifying variables (such as mother’s name, address, and age) and using an algorithm that evaluates the probability that the “N” in one database is the same person in another database.

“This is expensive, complex, [and] involves super-powerful computers and a lot of researchers,” she said.

The impressive mortality data for children with congenital Zika syndrome obtained by the group of researchers made it inevitable to think about how the country should address this terrible legacy.

“The first and most important recommendation is that the country needs to invest in primary care, so that women don’t get Zika during pregnancy and children aren’t at risk of getting the syndrome,” said Dr. Paixão.

As for the affected population, she highlighted the need to deepen the understanding of the syndrome’s natural history to improve survival and quality of life of affected children and their families. One possibility that was recently discussed by the group of researchers is to carry out a study on the causes of hospitalization of children with the syndrome to develop appropriate protocols and procedures that reduce admissions and death in this population.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ACIP releases new dengue vaccine recommendations

The vaccine is only to be used for children aged 9-16 who live in endemic areas and who have evidence with a specific diagnostic test of prior dengue infection.

Dengue is a mosquito-borne virus found throughout the world, primarily in tropical or subtropical climates. Cases had steadily been increasing to 5.2 million in 2019, and the geographic distribution of cases is broadening with climate change and urbanization. About half of the world’s population is now at risk.

The dengue virus has four serotypes. The first infection may be mild or asymptomatic, but the second one can be life-threatening because of a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement.

The lead author of the new recommendations is Gabriela Paz-Bailey, MD, PhD, division of vector-borne diseases, dengue branch, CDC. She told this news organization that, during the second infection, when there are “low levels of antibodies from that first infection, the antibodies help the virus get inside the cells. There the virus is not killed, and that results in increased viral load, and then that can result in more severe disease and the plasma leakage” syndrome, which can lead to shock, severe bleeding, and organ failure. The death rate for severe dengue is up to 13%.

Previous infection with Zika virus, common in the same areas where dengue is endemic, can also increase the risk for symptomatic and severe dengue for subsequent infections.

In the United States, Puerto Rico is the main focus of control efforts because 95% of domestic dengue cases originate there – almost 30,000 cases between 2010 and 2020, with 11,000 cases and 4,000 hospitalizations occurring in children between the ages of 10 and 19.

Because Aedes aegypti, the primary mosquito vector transmitting dengue, is resistant to all commonly used insecticides in Puerto Rico, preventive efforts have shifted from insecticides to vaccination.

Antibody tests prevaccination

The main concern with the Sanofi’s dengue vaccine is that it could act as an asymptomatic primary dengue infection, in effect priming the body for a severe reaction from antibody-dependent enhancement with a subsequent infection. That is why it’s critical that the vaccine only be given to children with evidence of prior disease.

Dr. Paz-Bailey said: “The CDC came up with recommendations of what the performance of the test used for prevaccination screening should be. And it was 98% specificity and 75% sensitivity. ... But no test by itself was found to have a specificity of 98%, and this is why we’re recommending the two-test algorithm,” in which two different assays are run off the same blood sample, drawn at a prevaccination visit.

If the child has evidence of prior dengue, they can proceed with vaccination to protect against recurrent infection. Dengvaxia is given as a series of three shots over 6 months. Vaccine efficacy is 82% – so not everyone is protected, and additionally, that protection declines over time.

There is concern that it will be difficult to achieve compliance with such a complex regimen. Dr. Paz-Bailey said, “But I think that the trust in vaccines that is highly prevalent for [Puerto] Rico and trusting the health care system, and sort of the importance that is assigned to dengue by providers and by parents because of previous outbreaks and previous experiences is going to help us.” She added, “I think that the COVID experience has been very revealing. And what we have learned is that Puerto Rico has a very strong health care system, a very strong network of vaccine providers. ... Coverage for COVID vaccine is higher than in other parts of the U.S.”

One of the interesting things about dengue is that the first infection can range from asymptomatic to life-threatening. The second infection is generally worse because of this antibody-dependent enhancement phenomenon. Eng Eong Ooi, MD, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology, National University of Singapore, told this news organization, “After you have two infections, you seem to be protected quite well against the remaining two [serotypes]. The vaccine serves as another episode of infection in those who had prior dengue, so then any natural infections after the vaccination in the seropositive become like the outcome of a third or fourth infection.”

Vaccination alone will not solve dengue. Dr. Ooi said, “There’s not one method that would fully control dengue. You need both vaccines as well as control measures, whether it’s Wolbachia or something else. At the same time, I think we need antiviral drugs, because hitting this virus in just one part of its life cycle wouldn’t make a huge, lasting impact.” Dr. Ooi added that as “the spread of the virus and the population immunity drops, you’re actually now more vulnerable to dengue outbreaks when they do get introduced. So, suppressing transmission alone isn’t the answer. You also have to keep herd immunity levels high. So if we can reduce the virus transmission by controlling either mosquito population or transmission and at the same time vaccinate to keep the immunity levels high, then I think we have a chance of controlling dengue.”

Dr. Paz-Bailey concluded: “I do want to emphasize that we are excited about having these tools, because for years and years, we have had really limited options to prevent and control dengue. It’s an important addition to have the vaccine be approved to be used within the U.S., and it’s going to pave the road for future vaccines.”

Dr. Paz-Bailey and Dr. Ooi reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The vaccine is only to be used for children aged 9-16 who live in endemic areas and who have evidence with a specific diagnostic test of prior dengue infection.

Dengue is a mosquito-borne virus found throughout the world, primarily in tropical or subtropical climates. Cases had steadily been increasing to 5.2 million in 2019, and the geographic distribution of cases is broadening with climate change and urbanization. About half of the world’s population is now at risk.

The dengue virus has four serotypes. The first infection may be mild or asymptomatic, but the second one can be life-threatening because of a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement.

The lead author of the new recommendations is Gabriela Paz-Bailey, MD, PhD, division of vector-borne diseases, dengue branch, CDC. She told this news organization that, during the second infection, when there are “low levels of antibodies from that first infection, the antibodies help the virus get inside the cells. There the virus is not killed, and that results in increased viral load, and then that can result in more severe disease and the plasma leakage” syndrome, which can lead to shock, severe bleeding, and organ failure. The death rate for severe dengue is up to 13%.

Previous infection with Zika virus, common in the same areas where dengue is endemic, can also increase the risk for symptomatic and severe dengue for subsequent infections.

In the United States, Puerto Rico is the main focus of control efforts because 95% of domestic dengue cases originate there – almost 30,000 cases between 2010 and 2020, with 11,000 cases and 4,000 hospitalizations occurring in children between the ages of 10 and 19.

Because Aedes aegypti, the primary mosquito vector transmitting dengue, is resistant to all commonly used insecticides in Puerto Rico, preventive efforts have shifted from insecticides to vaccination.

Antibody tests prevaccination

The main concern with the Sanofi’s dengue vaccine is that it could act as an asymptomatic primary dengue infection, in effect priming the body for a severe reaction from antibody-dependent enhancement with a subsequent infection. That is why it’s critical that the vaccine only be given to children with evidence of prior disease.

Dr. Paz-Bailey said: “The CDC came up with recommendations of what the performance of the test used for prevaccination screening should be. And it was 98% specificity and 75% sensitivity. ... But no test by itself was found to have a specificity of 98%, and this is why we’re recommending the two-test algorithm,” in which two different assays are run off the same blood sample, drawn at a prevaccination visit.

If the child has evidence of prior dengue, they can proceed with vaccination to protect against recurrent infection. Dengvaxia is given as a series of three shots over 6 months. Vaccine efficacy is 82% – so not everyone is protected, and additionally, that protection declines over time.