User login

How could improved provider communication have improved the care this patient received?

THE CASE

A 40-year-old white woman presented to clinic with multiple pruritic skin lesions on her abdomen, arms, and legs that had developed over a 2-month period. The patient reported that she’d been feeling tired and had been experiencing psychological stressors in her personal life. Her medical history was significant for psoriasis (which was controlled), and her family history was significant for breast and bone cancer (mother) and asbestos-related lung cancer (maternal grandfather).

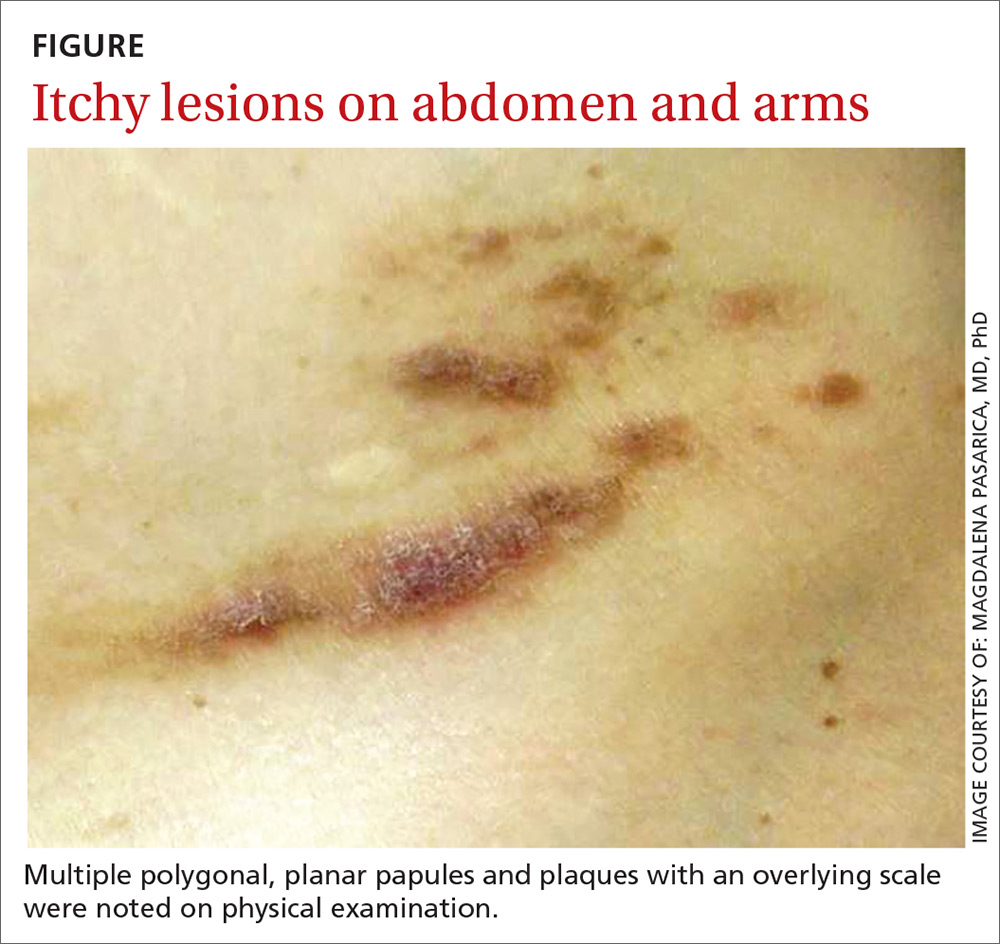

A physical examination, which included breast and pelvic exams, was unremarkable apart from the lesions located on her abdomen, arms, and legs. On skin examination, we noted multiple polygonal, planar papules and plaques of varying size with an overlying scale (FIGURE).

THE DIAGNOSIS

The physician obtained a biopsy of one of the skin lesions, and it was sent to a dermatopathologist to evaluate. Unfortunately, though, the patient’s history and a description of the lesion were not included with the initial biopsy requisition form. Based on the biopsy sample alone, the dermatopathologist’s report indicated a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis.

A search for malignancy. Any case of sudden, extensive seborrheic keratosis is suspected to be a Leser-Trélat sign, which is known to be associated with human immunodeficiency virus or underlying malignancy—especially in the gastrointestinal system. The physician talked to the patient about the possibility of malignancy, and an extensive work-up was performed, including multiple laboratory tests, computed tomography (CT) imaging, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, a colonoscopy, and mammography. None of the test results showed signs of an underlying malignancy.

In light of the negative findings, the physician reached out to the dermatopathologist to further discuss the case. It was determined that the dermatopathologist did not receive any clinical information (prior to this discussion) from the primary care office. This was surprising to the primary care physician, who was under the assumption that the clinical chart would be sent along with the biopsy sample. With this new information, the dermatopathologist reexamined the slides and diagnosed the lesion as lichen planus, a rather common skin disease not associated with cancer.

[polldaddy:10153197]

DISCUSSION

A root-cause analysis of this case identified multiple system failures, focused mainly on a lack of communication between providers:

- The description of the lesion and of the patient’s history were not included with the initial biopsy requisition form due to a lack of communication between the nurse and the physician performing the procedure.

- The dermatopathologist did not seek additional clinical information from the referring physician after receiving the sample.

- When the various providers did communicate, an accurate diagnosis was reached—but only after extensive investigation (and worry).

Communication is key to an accurate diagnosis

In 2000, it was estimated that health care costs due to preventable adverse events represent more than half of the $37.6 billion spent on health care.1 Since then, considerable effort has been made to address patient safety, misdiagnosis, and cost-effectiveness. Root cause analysis is one of the most popular methods used to evaluate and prevent future serious adverse events.2

Continue to: Diagnostic errors are often unreported...

Diagnostic errors are often unreported or unrecognized, especially in the outpatient setting.3 Studies focused on reducing diagnostic error show that a second review of pathology slides reduces error, controls costs, and improves quality of health care.4

Don’t rely (exclusively) on the health record. Gaps in effective communication between providers are a leading cause of preventable adverse events.5,6 The incorporation of electronic health records has allowed for more streamlined communication between providers. However, the mere presence of patient records in a common system does not guarantee the receipt or communication of information. The next step after entering the information into the record is to communicate it.

Our patient underwent a battery of costly and unnecessary tests and procedures, many of which were unwarranted at her age. In addition to being exposed to harmful radiation, she also experienced significant stress secondary to the tests and anticipation of the results. However, a root cause analysis of the case led to an improved protocol for communication between providers at the outpatient clinic. We now emphasize the necessity of including a clinical history and corresponding physical findings with all biopsies. We also encourage more direct communication between nursing staff, primary care physicians, and specialists.

THE TAKEAWAY

As medical professionals become increasingly reliant on the many emerging studies available to them, we sometimes forget that communication is key to optimal medical care, an accurate diagnosis, and patient safety.

Continue to: In addition, a second review...

In addition, a second review of dermatopathologic slides may be warranted if the pathologic diagnosis is inconsistent with the clinical picture or if the diagnosed condition is resistant to the usual therapies of choice. Incorrect diagnoses are more likely to occur when tests are interpreted in a vacuum without the corresponding clinical correlation. The weight of these mistakes is felt not only by the health care system, but by the patients themselves.

CORRESPONDENCE

Magdalena Pasarica, MD, PhD, University of Central Florida College of Medicine, 6850 Lake Nona Boulevard, Orlando, FL 32827; [email protected]

1. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Patient safety primer: root cause analysis. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/10/root-cause-analysis. Updated August 2018. Accessed September 27, 2018.

3. Newman-Toker DE, Pronovost PJ. Diagnostic errors-the next frontier for patient safety. JAMA. 2009;301:1060-1062.

4. Kuijpers CC, Burger G, Al-Janabi S, et al. Improved quality of patient care through routine second review of histopathology specimens prior to multidisciplinary meetings. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:866-871.

5. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:85-90.

6. Robinson NL. Promoting patient safety with perioperative hand-off communication. J Perianesth Nurs. 2016;31:245-253.

THE CASE

A 40-year-old white woman presented to clinic with multiple pruritic skin lesions on her abdomen, arms, and legs that had developed over a 2-month period. The patient reported that she’d been feeling tired and had been experiencing psychological stressors in her personal life. Her medical history was significant for psoriasis (which was controlled), and her family history was significant for breast and bone cancer (mother) and asbestos-related lung cancer (maternal grandfather).

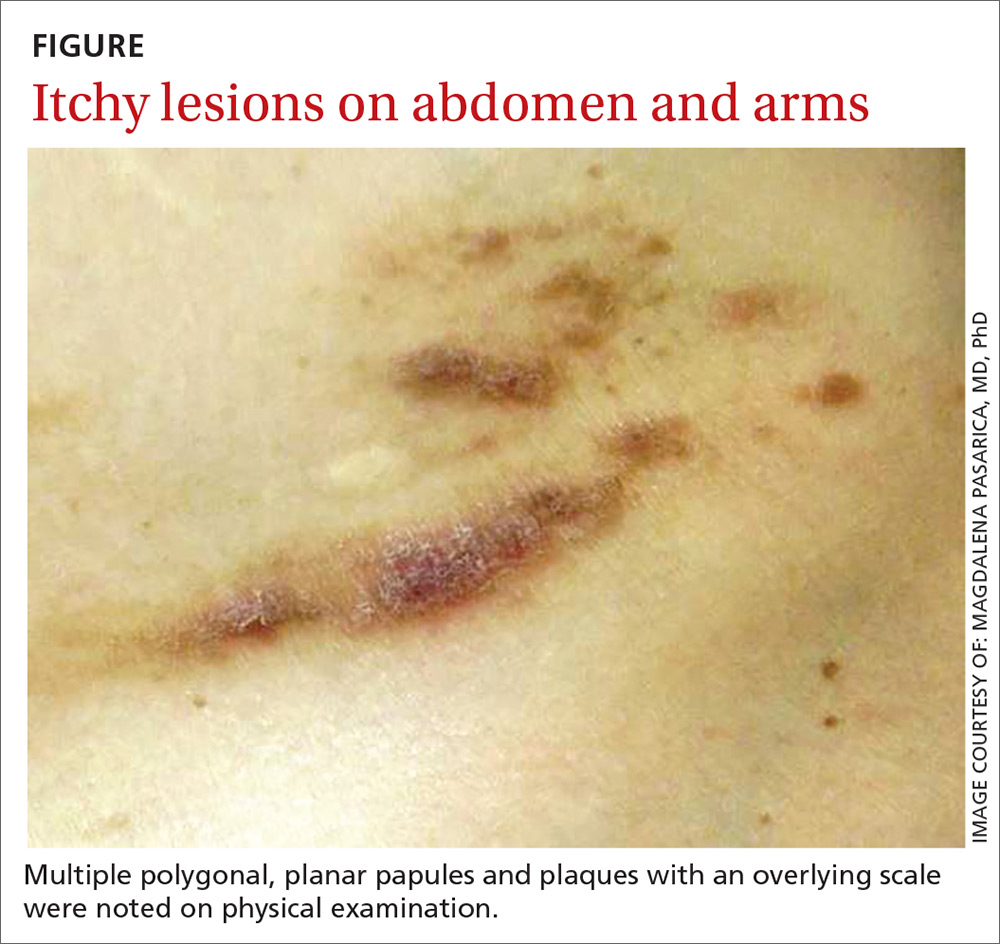

A physical examination, which included breast and pelvic exams, was unremarkable apart from the lesions located on her abdomen, arms, and legs. On skin examination, we noted multiple polygonal, planar papules and plaques of varying size with an overlying scale (FIGURE).

THE DIAGNOSIS

The physician obtained a biopsy of one of the skin lesions, and it was sent to a dermatopathologist to evaluate. Unfortunately, though, the patient’s history and a description of the lesion were not included with the initial biopsy requisition form. Based on the biopsy sample alone, the dermatopathologist’s report indicated a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis.

A search for malignancy. Any case of sudden, extensive seborrheic keratosis is suspected to be a Leser-Trélat sign, which is known to be associated with human immunodeficiency virus or underlying malignancy—especially in the gastrointestinal system. The physician talked to the patient about the possibility of malignancy, and an extensive work-up was performed, including multiple laboratory tests, computed tomography (CT) imaging, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, a colonoscopy, and mammography. None of the test results showed signs of an underlying malignancy.

In light of the negative findings, the physician reached out to the dermatopathologist to further discuss the case. It was determined that the dermatopathologist did not receive any clinical information (prior to this discussion) from the primary care office. This was surprising to the primary care physician, who was under the assumption that the clinical chart would be sent along with the biopsy sample. With this new information, the dermatopathologist reexamined the slides and diagnosed the lesion as lichen planus, a rather common skin disease not associated with cancer.

[polldaddy:10153197]

DISCUSSION

A root-cause analysis of this case identified multiple system failures, focused mainly on a lack of communication between providers:

- The description of the lesion and of the patient’s history were not included with the initial biopsy requisition form due to a lack of communication between the nurse and the physician performing the procedure.

- The dermatopathologist did not seek additional clinical information from the referring physician after receiving the sample.

- When the various providers did communicate, an accurate diagnosis was reached—but only after extensive investigation (and worry).

Communication is key to an accurate diagnosis

In 2000, it was estimated that health care costs due to preventable adverse events represent more than half of the $37.6 billion spent on health care.1 Since then, considerable effort has been made to address patient safety, misdiagnosis, and cost-effectiveness. Root cause analysis is one of the most popular methods used to evaluate and prevent future serious adverse events.2

Continue to: Diagnostic errors are often unreported...

Diagnostic errors are often unreported or unrecognized, especially in the outpatient setting.3 Studies focused on reducing diagnostic error show that a second review of pathology slides reduces error, controls costs, and improves quality of health care.4

Don’t rely (exclusively) on the health record. Gaps in effective communication between providers are a leading cause of preventable adverse events.5,6 The incorporation of electronic health records has allowed for more streamlined communication between providers. However, the mere presence of patient records in a common system does not guarantee the receipt or communication of information. The next step after entering the information into the record is to communicate it.

Our patient underwent a battery of costly and unnecessary tests and procedures, many of which were unwarranted at her age. In addition to being exposed to harmful radiation, she also experienced significant stress secondary to the tests and anticipation of the results. However, a root cause analysis of the case led to an improved protocol for communication between providers at the outpatient clinic. We now emphasize the necessity of including a clinical history and corresponding physical findings with all biopsies. We also encourage more direct communication between nursing staff, primary care physicians, and specialists.

THE TAKEAWAY

As medical professionals become increasingly reliant on the many emerging studies available to them, we sometimes forget that communication is key to optimal medical care, an accurate diagnosis, and patient safety.

Continue to: In addition, a second review...

In addition, a second review of dermatopathologic slides may be warranted if the pathologic diagnosis is inconsistent with the clinical picture or if the diagnosed condition is resistant to the usual therapies of choice. Incorrect diagnoses are more likely to occur when tests are interpreted in a vacuum without the corresponding clinical correlation. The weight of these mistakes is felt not only by the health care system, but by the patients themselves.

CORRESPONDENCE

Magdalena Pasarica, MD, PhD, University of Central Florida College of Medicine, 6850 Lake Nona Boulevard, Orlando, FL 32827; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 40-year-old white woman presented to clinic with multiple pruritic skin lesions on her abdomen, arms, and legs that had developed over a 2-month period. The patient reported that she’d been feeling tired and had been experiencing psychological stressors in her personal life. Her medical history was significant for psoriasis (which was controlled), and her family history was significant for breast and bone cancer (mother) and asbestos-related lung cancer (maternal grandfather).

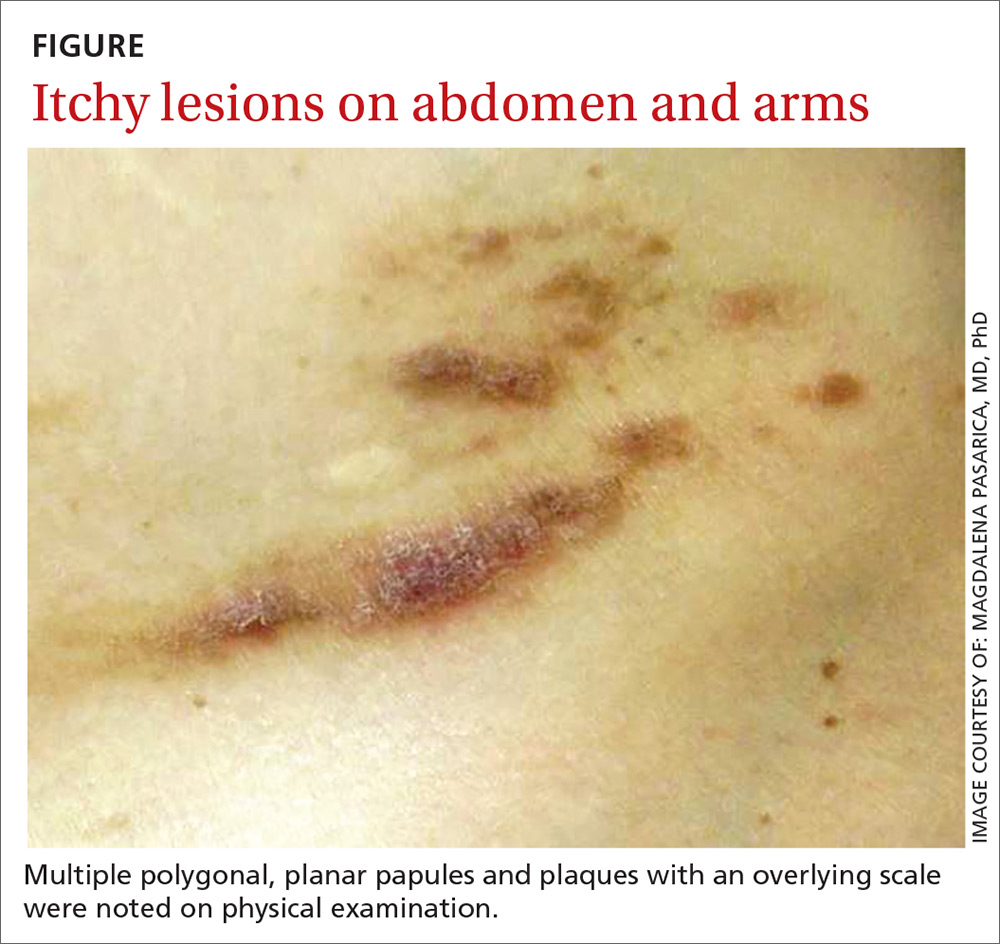

A physical examination, which included breast and pelvic exams, was unremarkable apart from the lesions located on her abdomen, arms, and legs. On skin examination, we noted multiple polygonal, planar papules and plaques of varying size with an overlying scale (FIGURE).

THE DIAGNOSIS

The physician obtained a biopsy of one of the skin lesions, and it was sent to a dermatopathologist to evaluate. Unfortunately, though, the patient’s history and a description of the lesion were not included with the initial biopsy requisition form. Based on the biopsy sample alone, the dermatopathologist’s report indicated a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis.

A search for malignancy. Any case of sudden, extensive seborrheic keratosis is suspected to be a Leser-Trélat sign, which is known to be associated with human immunodeficiency virus or underlying malignancy—especially in the gastrointestinal system. The physician talked to the patient about the possibility of malignancy, and an extensive work-up was performed, including multiple laboratory tests, computed tomography (CT) imaging, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, a colonoscopy, and mammography. None of the test results showed signs of an underlying malignancy.

In light of the negative findings, the physician reached out to the dermatopathologist to further discuss the case. It was determined that the dermatopathologist did not receive any clinical information (prior to this discussion) from the primary care office. This was surprising to the primary care physician, who was under the assumption that the clinical chart would be sent along with the biopsy sample. With this new information, the dermatopathologist reexamined the slides and diagnosed the lesion as lichen planus, a rather common skin disease not associated with cancer.

[polldaddy:10153197]

DISCUSSION

A root-cause analysis of this case identified multiple system failures, focused mainly on a lack of communication between providers:

- The description of the lesion and of the patient’s history were not included with the initial biopsy requisition form due to a lack of communication between the nurse and the physician performing the procedure.

- The dermatopathologist did not seek additional clinical information from the referring physician after receiving the sample.

- When the various providers did communicate, an accurate diagnosis was reached—but only after extensive investigation (and worry).

Communication is key to an accurate diagnosis

In 2000, it was estimated that health care costs due to preventable adverse events represent more than half of the $37.6 billion spent on health care.1 Since then, considerable effort has been made to address patient safety, misdiagnosis, and cost-effectiveness. Root cause analysis is one of the most popular methods used to evaluate and prevent future serious adverse events.2

Continue to: Diagnostic errors are often unreported...

Diagnostic errors are often unreported or unrecognized, especially in the outpatient setting.3 Studies focused on reducing diagnostic error show that a second review of pathology slides reduces error, controls costs, and improves quality of health care.4

Don’t rely (exclusively) on the health record. Gaps in effective communication between providers are a leading cause of preventable adverse events.5,6 The incorporation of electronic health records has allowed for more streamlined communication between providers. However, the mere presence of patient records in a common system does not guarantee the receipt or communication of information. The next step after entering the information into the record is to communicate it.

Our patient underwent a battery of costly and unnecessary tests and procedures, many of which were unwarranted at her age. In addition to being exposed to harmful radiation, she also experienced significant stress secondary to the tests and anticipation of the results. However, a root cause analysis of the case led to an improved protocol for communication between providers at the outpatient clinic. We now emphasize the necessity of including a clinical history and corresponding physical findings with all biopsies. We also encourage more direct communication between nursing staff, primary care physicians, and specialists.

THE TAKEAWAY

As medical professionals become increasingly reliant on the many emerging studies available to them, we sometimes forget that communication is key to optimal medical care, an accurate diagnosis, and patient safety.

Continue to: In addition, a second review...

In addition, a second review of dermatopathologic slides may be warranted if the pathologic diagnosis is inconsistent with the clinical picture or if the diagnosed condition is resistant to the usual therapies of choice. Incorrect diagnoses are more likely to occur when tests are interpreted in a vacuum without the corresponding clinical correlation. The weight of these mistakes is felt not only by the health care system, but by the patients themselves.

CORRESPONDENCE

Magdalena Pasarica, MD, PhD, University of Central Florida College of Medicine, 6850 Lake Nona Boulevard, Orlando, FL 32827; [email protected]

1. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Patient safety primer: root cause analysis. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/10/root-cause-analysis. Updated August 2018. Accessed September 27, 2018.

3. Newman-Toker DE, Pronovost PJ. Diagnostic errors-the next frontier for patient safety. JAMA. 2009;301:1060-1062.

4. Kuijpers CC, Burger G, Al-Janabi S, et al. Improved quality of patient care through routine second review of histopathology specimens prior to multidisciplinary meetings. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:866-871.

5. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:85-90.

6. Robinson NL. Promoting patient safety with perioperative hand-off communication. J Perianesth Nurs. 2016;31:245-253.

1. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Patient safety primer: root cause analysis. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/10/root-cause-analysis. Updated August 2018. Accessed September 27, 2018.

3. Newman-Toker DE, Pronovost PJ. Diagnostic errors-the next frontier for patient safety. JAMA. 2009;301:1060-1062.

4. Kuijpers CC, Burger G, Al-Janabi S, et al. Improved quality of patient care through routine second review of histopathology specimens prior to multidisciplinary meetings. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:866-871.

5. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:85-90.

6. Robinson NL. Promoting patient safety with perioperative hand-off communication. J Perianesth Nurs. 2016;31:245-253.